ABSTRACT

This article explores fragmented historical references on African itinerants in South Asia between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries who worked in the coastal regions as Islamic scholars, benefactors, and leaders. Utilizing epigraphic, architectural and textual sources on a few such personalities from Malabar and Bengal, I take a preliminary step towards debunking the exclusive association of Africans in South Asia with slavery and military labour. These historical figures are not anomalies rather they are representatives of a larger intellectual, legal, and religious network that fared between Asia and Africa. Although they are evident in historical sources, they have been systematically forgotten in contemporary memories and scholarship while this forgetfulness befits the prevalent stereotyping tendencies of Africa and Africans in South Asia.

‘The Indian Ocean Muslims’ have contributed to the synthesis of Islamic history for over a millennium, but their roles have been continuously downplayed and disregarded in the historiography. The South Asians [al-Hindīs], Southeast Asians [al-Jāwīs] and Eastern Africans [al-Zanjīs, Swahilis, al-Ḥabshīs] interacted across the Indian Ocean highway and all shaped Islam in their own ways. Only a small number of people indeed voyaged overseas physically, but a large number of communities were influenced by the ideas introduced by those who did travel. Specifically, the history of Islam in the Indian Ocean world narrates this general pattern of mobility across communities, doctrines, texts, sources, places and periods. The Arabs and Persians played an inevitable role in circulating certain basic ideas of Islam, but they did not ‘export’ it wholesale to ‘the peripheries’ as many studies of Islam in the Indian Ocean littoral have illustrated by ignoring the African and Asian contributions.Footnote1 The making of Islam in the littoral has always been a rather complex process with active involvement of people from diverse ethnic, linguistic, and regional backgrounds. Once introduced to the religion, these Indian Ocean Muslims formulated and reformulated their own perspectives and practices in constructive and creative ways and transferred them to other places and people. Against this background, stories of several African and Asian doyens working in South, Southeast Asia and Eastern Africa in premodern centuries are very crucial as the significant benefactors to the historical and human experience of the religion.

In this article, I take a preliminary step towards understanding the Eastern Africans who worked in South Asia as judges, jurists, scholars, teachers, preachers and/or religious leaders in the premodern period to demonstrate how they contributed to the making of Islam in the subcontinent, which now hosts the largest Muslim population in the world. This attempt is directly related to a considerable gap in the literature: the ways in which Africans in Asia have been discussed. Most studies present them as slaves and mercenaries alone, especially in the growing literature on slavery in the Indian Ocean world, and neglect their socio-cultural functions outside the broad contemporary conceptions of ‘slavery’.Footnote2 A few literatures of political-military histories have analysed the military and administrative functions and struggles of many Africans, but their intellectual contributions are yet to be acknowledged.Footnote3

A short note on the period and sources: although my larger project is to explore Islamic legal history in the premodern Indian Ocean world since its formative stages through comparative and connected histories of Arabs, Asians and Africans, this essay is on a period between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries. Before the twelfth century, we rarely have references on African-Asian intellectual interactions, whereas the situation dramatically changes by the late-fifteenth century with an unprecedented rise of African political and military elites in Asia, such as the Abyssinian kingdoms of Bengal and Janjira. By the second half of the sixteenth century, their number and influence increased even more through figures like Malik Ambar. In order to analyse their implications on, contributions to, and administration of legal systems and traditions, much space and time are needed and I hope to take it up elsewhere. The period from the twelfth to the fifteenth centuries thus provides a small prelude to a larger phenomenon of the African intellectual contributions in the making of Islam and its laws in South and Southeast Asia. My major sources are travel accounts, tārikh literature and inscriptions from or on the South Asian littoral.

A jurist, an agent, and an endower

The Islamic scholarly community from coastal Eastern Africa is an important but largely neglected group that contributed to the making of Islam in the wider Indian Ocean littoral. The coast as such has been neglected in the premodern Indian Ocean historiography, despite the ocean and its seas once being identified as the African Ocean, the Zanj Ocean (Baḥr al-Zanj) and the Abyssinian Ocean (Baḥr al-Ḥabashī).Footnote4 More than two decades ago Chandra De Silva endeavoured to deconstruct this myth by demonstrating how and why the African coast was side-lined by early European commentators and later by Eurocentric historians. He also pointed out the contributions of local Eastern African communities to the oceanic world in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.Footnote5 This is also the case in Islamic historiography where scholars make blanket generalizations that almost all prominent traders, brokers, and scholars in Eastern Africa were Arabs and Persians. In Islamic history in particular, although it is difficult to distinguish local Swahilis or Zanjis in premodern sources, some scarce but crucial remarks about geographical or familial affiliations or physical features do provide us with a stepping stone towards further enquiries about their intellectual engagements and the implications.

One early reference to an Eastern African jurist in South Asia comes from the account of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, the North African traveller who was also appointed judge in Delhi and Maldives. He wrote in the mid-fourteenth century that he had met one Faqīh Saʿīd from Mogadishu working at Ezhimala (Hīlī) in northern Malabar (southwest India).Footnote6 According to Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, this Somalian jurist had travelled from Mogadishu to both Mecca and Medina, had studied there for fourteen years each, and had been in touch with many scholars of the Holy Cities as well as their rulers, Muḥammad Abū Numayy in Mecca (r. 1254–1301) and Manṣūr bin Jammāz in Medina (r. 1300–1325). Based on the rulers’ terms of reign, we can assume that Faqīh studied in Mecca sometime between the late-1280s and 1300, and in Medina between 1300 and 1315. After his education in Hijaz, Faqīh Saʿīd travelled to India and China, but we do not know what sort of jobs he took at the places he visited. He settled down finally in Malabar in a port-town called Ezhimala, which was frequented by several Chinese ships and had a very active religious sphere. It had an important congregational mosque, a madrasa, and an imam where both Muslims and non-Muslims sought blessings (baraka) from the sanctity of the mosque; seafarers made plenty of offerings to it before they set out to sail. The mosque had a rich treasury, under the supervision of the khaṭīb Ḥusayn. Several students studied at the mosque, and they received stipends from its revenue. It also prepared food for travellers and the destitute in its own kitchen. Faqīh Saʿīd must have arrived there directly from China since Chinese ships frequented the port.Footnote7 In the city, he collaborated with Ḥusayn, possibly the author of Qayd al-Jāmiʿ, one of the first known Islamic legal texts from Malabar.Footnote8 It deals with marital rules, proceedings and requirements from the viewpoint of Shāfiʿī school of Islamic law, and its authorship is ascribed to a certain Faqīh Ḥusayn bin Aḥmad al-Mahfanī from the mid-fourteenth century.Footnote9 We do not have much information about him unfortunately, but the local scholars assume that Ibn Baṭṭūṭa’s reference here, as well as in a discussion of a miraculous tree found in Malabar, are attributed to this same scholar.

Ibn Baṭṭūṭa gives only a short description of this ‘other African’ who had far outshone his own journeys. This likely indicates that Faqīh Saʿīd was not an exceptional case in his time and that there were many similar African scholars who found their way to Asian Islamic communities in premodern centuries.

Relatedly, after mentioning Faqīh Saʿīd, Ibn Baṭṭūṭa immediately talks about another Malabari port-town called Jurfattan, three leagues from Ezhimala, and he makes a comparative statement on the practice of inheritance law among the Malabaris and Africans. The context of comparison is interesting as he makes it with regard to an Arab jurist from Baghdad. He writes:

There [in Jurfattan] I met a jurist from Baghdad of high stature, named al-Ṣarṣarī after Ṣarṣar, a place ten miles away from Baghdad on the way to Kūfa. […] He had a brother in this town with a lot of money which he had asked to give to his young children by will. The deceased person’s property was kept in the shipload to Baghdad. The custom (ʿāda) of the Indians is like the custom (ʿāda) of the Sūdān that they do not interpose in the property of the deceased. Even if the person leaves thousands, his property would remain with the leader of the Muslims until the inheritor takes it according to sharʿ.Footnote10

The motivations behind his comparison of a regional custom in Malabar with the one in the ‘Sūdān’ (broadly ‘black Africa’, if we follow H.A.R. Gibb’s translation) are very intriguing, especially as he says that the property of the deceased person finally reaches the legal inheritor.Footnote11 This implies that many parts of the Islamic world, probably including Ibn Baṭṭūṭa’s native place in North Africa, did not follow the ‘sharīʿa mode’ of preserving inheritance in the absence of an inheritor. Further research is needed to make a conclusive argument, but for the moment suffice to note the potential similarity in the legal practices of Muslims in Malabar/India and Sahel/Western Africa as remarked by a North African jurist who had travelled extensively in Africa, the Middle East and Asia.

Another important Eastern African who worked in South Asia was Yāqūt al-Ghiyāthī from fifteenth-century Bengal. He undertook a challenging project of establishing law colleges in Mecca and Medina on behalf of a Bengali king of Ilyās Shāhi dynasty, Ghiyāth al-Dīn Aʿẓam Shāh (r. 1390–1411).Footnote12 We do not have much biographical information on Yāqūt outside the details of his journey from Bengal to Mecca and his incredible activities in the city as told by a Meccan historian who met and wrote about him. But certainly, he was part of a larger Abyssinian community in Bengal in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, similar to many more in the whole of South Asia and across the Indian Ocean littoral. Yāqūt was well-versed in navigation, administration and diplomacy – a few matters that became very explicit during his Mecca mission. I have written elsewhere in detail about this fascinating project of legal connections and circulations of people, ideas and capital between the Swahili Coast, Bengal and Mecca.Footnote13

Only to elaborate briefly here on Yāqūt, we do not know what his status was in the Bengali royal court. The florid Arabic nouns like Jawhar (jewel) and Yāqūt (ruby, garnet) were given as distinctive names to the Black African eunuchs and slaves sold in the Middle Eastern markets, and many of them sustained those names even after their manumission.Footnote14 Both slaves and ex-slaves had only ‘a single name without patronymic and without tribal, regional or other cognomen’ and sometimes they were called with the nisba of their masters.Footnote15 From the cognomen Yāqūt therefore it is difficult to identify whether he was a slave, freeman, or an agent of the king. Since Yāqūt was more specifically used to denote the Abyssinian eunuchs, we can assume that he was a eunuch.Footnote16 The Meccan historian Taqī al-Dīn al-Fāsī (d. 1429) gives his full name as Yāqūt al-Sulṭānī al-Ghiyāthī, which only indicates his connection with Sultan Ghiyāth al-Dīn Aʿẓam Shāh.Footnote17 Furthermore, al-Fāsī praises him by calling him ‘janāb al-ʿālī al-iftikhārī’ (his excellency and lord), surely for the ideas and the capital he brought into Mecca. Aʿẓam Shah assigned him with responsibilities to purchase land, to construct appropriate building for law college and to take necessary formal steps in making the endowment legally valid. Yāqūt went several steps further by gathering support from many Meccan elites, many of whom he eventually appointed as professors in the law college, including the historian and judge al-Fāsī – our prime source on him. After accomplishing his mission, Yāqūt commenced his return to Bengal, but died on his way at Hormuz.

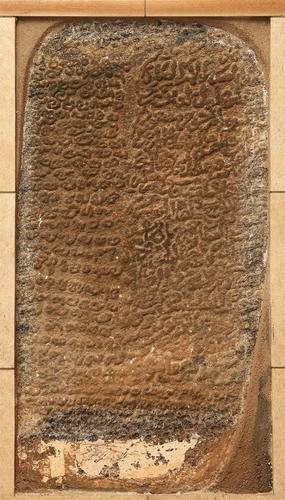

Image 1. A thirteenth-century bilingual inscription (in Arabic and Malayalam) kept at the outer wall of the Muccunti Mosque in Calicut. The Arabic part says that Shihāb al-Dīn Marjān (or Rayḥān), freed slave of the late Masʿūd, endowed the land and commissioned the construction of the mosque

If Yāqūt is an agent of a bequeathing South Asian king, we have also evidence on an Eastern African endower himself from the thirteenth-century Malabar Coast who established a mosque in the port city of Calicut and appointed an imam and caller to prayer with salaries. This evidence comes from a thirteenth-century bilingual inscription kept at the outer-wall of the Muccunti Mosque in Kutticcira, Calicut: one part of it is written in Arabic (in the Naskhi script) and on the other part, in old Malayalam (in the circular script or vaṭṭeḻuttu) (see). The Malayalam part on the left side has been deciphered by M.G.S. Narayanan and M.R. Raghava Varier and they have related it as a grant from the local ruler the Zamorin towards the daily expenses of the mosque.Regarding its establishment and maintenance the Arabic part on the right side provides more details. It has been read by a representative of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) in the 1940s and a summary has been given in their annual report:

“Seems to state that Shihābu’d-Dīn Raihan, freed slave (ʿatīq) of the late Masʿūd, purchased (?) land, out of his own money, from its owner and constructed thereon this mosque and well (?) and made (provision) for its leader of prayers (imām) and caller to prayers (muʾadhdhin) by constructing a big edifice (?).”Footnote19

Many scholars have reproduced this summary without actually looking into the inscription, while some others have not looked at even the summary.Footnote20 Narayanan, for example, states that the Arabic part contains ‘a series of Muslim personal names, passages of prayer, and signatures’. In a footnote, he provides the English and Malayalam transcriptions of the Arabic letterings and it bears no relation with the original inscription or its ASI summary.Footnote21 Against this backdrop of contradiction, I have been trying to reread it with the help of Arabic epigraphist colleagues. But fortunately, Mehrdad Shokoohy, a renowned scholar of South Asian architecture and Arabo-Persian epigraphs, has recently read and published the Arabic part.Footnote22Footnote23Footnote24 I agree with most of his reading, although I revise it slightly on the basis of some words or letters as they appear to me:

1. [built this mosque]

2. and engraved this the former slave

3. Shihāb al-Dīn Marjān

4. … [of] the late Masʿūd

… … … … … … … ….

11. … and may he reside

12. [in] God’s Paradise

13. [in] the last day of [the month of … .]

14. of this year of

15. six and eighty and … .

Shokoohy assumes the last missing part on the century to be six hundred, summing it to be the Hijri year of 686, corresponding to 1287 CE. This year also relates to the assumption of chronology on the basis of its Malayalam part on the left side. Once we read both parts together, we could understand that the entire project was a remarkable endowment from an ex-slave-cum-trader Shihāb al-Dīn Marjān, and the local Hindu king endowed for its daily expenditures. This ex-slave could and did purchase the land, and the ruling Zamorin also assigned an additional land for the current and future maintenance.

Marjān must have been a business agent of the late Masʿūd, similar to the slave characterized in the In an Antique Land of Amitav Ghosh,Footnote25 who became rich after his manumission through maritime trade itself. His master Masʿūd is possibly similar to an Abyssinian captain with the same name who appears in the Judeo-Arabic Geniza documents a century earlier. In a Geniza letter sent from Aden to Malabar around 1139, its author, a Jewish merchant based in Aden writes about his unfinished deal with the Muslim captain (rubbān) ‘Masʿūd, the Abyssinian’ to whom he had sent some money to procure merchandises from Malabar.Footnote26 We also should be cautious about the time gap between the two documents, and therefore the Masʿūd in the inscription must be a different figure from the one in the Geniza letter. Nevertheless, Marjān worked for his master Masʿūd during his lifetime and gained his wealth and freedom and managed to establish a mosque in the newly established city of Calicut in the thirteenth century.

Such an activity as construction of a mosque in a religiously remote location like Calicut must have been an act to assert his own status as an independent believer or a pious merchant, as two Ugandans would contribute later to another mosque just four-hundred metres away (see below). Although the inscription does not explicate his ethnicity, the very name is indicative of the place of his origin. Similar to Yāqūt, Marjān (literally, ‘coral’) is another florid name used for slaves, especially from Abyssinia. He must have taken the common Arabic cognomen (laqab, pl. alqab) ‘Shihāb al-Dīn’ to indicate his status before or after manumission. According to the fourteenth-century administrative manual of Aḥmad al-Qalqashandī (1355–1418), the cognomens similar to Shihāb al-Dīn were commonly given to the Abyssinian eunuch military slaves.Footnote27 Specifically, al-Qalqashandī mentions that the name Zayn al-Dīn (‘beauty of religion’) was given to those with names Hilāl or Marjān, Sābiq al-Dīn (‘preceding in religion’) for Mithqāl, ʿIzz al-Dīn (‘pride of religion’) for Dinār, Shams al-Dīn (‘sun of religion’) for Ṣawāb, Badr al-Dīn (‘moon of religion’) for Luʾluʾ.Footnote28

Accordingly, the epigraph enlightens us on an outstanding benefaction from this ex-slave-cum-trader to the local Muslim community, and now it stands as an oldest surviving mosque-inscription with one of the solid evidences for the early Muslim settlement in the Malabar Coast. Although the region believes to have witnessed the arrival of Islam and establishment of several mosques in the seventh century itself across the coastal belt, we are yet to see any concrete evidences on early mosques from the first millennium of Common Era.Footnote29 The Calicut mosque and the inscription also demonstrate the interconnections in the thirteenth century between the Muslims and the local rulers in an Indian Ocean shoreline in which the community was not at all dominant or powerful. The reciprocal relationship they maintained with the local Hindu Zamorin kings helped them strengthen themselves religiously, communally in a richly cosmopolitan atmosphere.

The larger network

Shihāb al-Dīn Marjān, Yāqūt al-Ghiyāthī and Faqīh Saʿīd are three important yet divergent examples of a larger flow of Africans who participated in the making of Islam in premodern South Asia. If Saʿīd represents the group of proper jurists and itinerant scholars, Yāqūt and Shihāb stand for the clusters of agents and endowers who facilitated the intellectual and religious exchanges. There are many more similar Eastern Africans who worked across South Asia during these periods in different roles and positions. Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, for example, also talks about one ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Makdashawī who worked as the governor of the island Kannalus in the Maldives. During Ibn Baṭṭūṭa’s visit to the island, this Muslim administrator from Mogadishu ‘treated me with honour, offered me hospitality and prepared a kundara for me’ to meet the queen of the Maldives.

Also in the Maldives, Ibn Baṭṭūṭa visited the hospice of Shaykh Ṣāliḥ Najīb at the extremity of the island of Mahal, the seat of the Sultana and her husband, with the captain and Arab judge ʿĪsā al-Yamanī.Footnote30 Andrew Forbes identifies this hospice as the Habshīgefānu Magān (‘Shrine of the African Worthy’), built in memory of a little known Shaykh Najīb from Eastern Africa, together with a mosque. Shaykh Najīb travelled in the Maldives teaching Islam to the islanders and died at Karendu Island in Fadiffolu Atoll. The mosque and hospice were located in the precincts of the Lonu Ziyare (‘Salt Shrine’), but they were demolished in the early twentieth century.Footnote31 We can discern from the name of the shrine that the Shaykh was from Abyssinia (Habshī), but it is difficult to make any conclusions about his origin for the want of solid evidence. The Maldives also had a share of African slaves, and seventy of them were bought in, and brought from, the Hijaz in the mid-fifteenth century by the Maldivian king Sulṭān Ḥasan III. In an interesting course of events, one of these slaves killed a local Maldivian and the qāḍī (judge) ordered his execution, but the sultan instead burned the judge at the stake, if we are to believe an account given by Andrew Forbes and Fawzia Ali on the basis of the Tārīkh Islam Dībā Maḥal, one of the early accounts of the history of the Maldives written in the eighteenth century by al-Qāḍī Ḥasan Tāj al-Dīn (1661–1727).Footnote32

We also come across references to some more Eastern Africans in the mosque inscriptions of the western and eastern Indian Ocean. From Calicut, a city we mentioned above as a place where the former slave Shihāb al-Dīn Marjān had built a mosque in the thirteenth century, we have further references to the presence of Eastern African Muslims traders, jurists, benefactors, mercenaries and slaves. In the mid-fourteenth century, Ibn Baṭṭūṭa talks about Abyssinian men-at-arms who worked as ‘the protectors on this sea’ in the Chinese ships on the Calicut port as well as the commanders of warships in Barkur on the Konkan coast.Footnote33 ‘They were the leaders of the sea there. If there was one of them on a ship, it will be protected from the Indian thieves and infidels (kuffār).’Footnote34 He also talks about the nakhudā Mithqāl who resided in the city, who was ‘a well-known name and owner of great wealth and many ships to trade with India, China, Yemen, and Persia.’Footnote35 Besides this fleeting reference, we do not have much information on Mithqāl but one of the most iconic traditional mosques still extant in the city is named after him as Mithqāl Masjid (Mithqālpaḷḷi). Its exact date of establishment is unknown. It is most likely to be founded in the mid-fourteenth century itself by the same person as we have epigraphic and textual evidences on its existence in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries: it was destroyed in 1510 by the Portuguese who set it on fire and it was rebuilt by the local Muslims in 1578–9. All this is important when we consider his single name Mithqāl, conventionally given at the time for Abyssinian slaves. Paying attention to the name, Sebastian Prange has concluded recently, ‘It is plausible that the ancestors of Nākhudā Mithqāl, if not the man himself, were manumitted slaves […]. The loss of ancestral references entailed in slavery and conversion may have led this merchant to adopt a nickname, which encapsulated the basis for his economic standing that enabled him to function as a patron of Calicut’s Muslim community.’Footnote36

A few centuries later, although beyond the chronological focus of this article, we find more Eastern Africans maintaining and conserving the mosques of the city. Two notables from Entebbe in present-day Uganda contributed to the repair and maintenance of the Mithqāl Masjid. According to two separate inscriptions, one Khwājah Jamāl al-Dīn ʿAntābī renovated the carved pulpit (minbar) of the mosque in 1607/8 or 1618/9, and possibly his grandson Khwājah ʿUmar al-ʿAntābī repaired it again in 1677/8.Footnote37 In the inscriptions, the former is identified as ‘tāj al-muslimīn’ (Crown of the Muslims) and the latter as ‘ra’īs al-muslimīn’ (Commander of the Muslims) and both of them are identified as ‘shāhbandar’ (Master of the Port), indicating the higher positions they had acquired among the local and translocal oceanic Muslims and mercantile community at large. The title shāhbandar is particularly intriguing as it was an official or semi-official position existed across the Indian Ocean and the person in office mediated between the expatriate merchants and the local rulers.

Faqīh Saʿīd, Shihāb al-Dīn Marjān, Nākhudā Mithqāl and the ʿAntābīs all are further examples of many more Eastern Africans who arrived in South Asia and became involved in its religious, intellectual and mercantile circles. Together with them, we also need to look at the contributions of several Habshi and Swahili scholars who worked in the Middle East (especially in Yemen and Oman), and who contributed significantly to the advancement of Islam through their interactions across the Indian Ocean world. The spread, survival and prevalence of a specific school of Islamic law, that of the Shāfiʿīsm named after its founder Idrīs al-Shāfiʿī (d. 820), among the Muslims of both Eastern Africa and coastal South Asia indicate to the historical implications of such shared exchanges.Footnote38

All these instances demonstrate how mobile these Eastern Africans were, and that is what makes them a strong part of the Indian Ocean community. As we see in the case of Faqīh Saʿīd, Yāqūt and Shihāb al-Dīn Marjān they all travelled from the Eastern African coasts to faraway places: from Mogadishu to Mecca and Medina to China to Malabar (as Saʿīd did); from Ethiopia to Bengal to Mecca to Hormuz (as Yāqūt did). The same goes for several other Eastern Africans in the Maldives. Even if one could argue that Africans like Yāqūt were forced to travel across the seas by their masters or benefactors and that they did not travel voluntarily, the stories of Faqīh Saʿīd, ʿAbd al-ʿAzīz al-Makdashawī, Shaykh Ṣāliḥ Najīb and many more, indicate that some of them certainly travelled for their own interests and benefits rooted in intellectual, juridical, mystical and political aspirations.

What makes the fragmented narratives of these historical figures interesting is that they challenge the specific set of images typecast on the African communities in premodern and early modern South Asian history as slaves and mercenaries alone. Even though such narratives on African peregrinations for knowledge, law, religion and philanthropy are forgotten in both public and scholarly memories, they continue to survive in disconnected and patchy evidences encouraging us to re-inscribe their vanished narratives into our understanding of the community and to forefront their unstudied and understudied iterations. As these figures appear sporadically in the travel accounts, epigraphs, architectural complexes and chronicles and when we try to uncover them, the primary sources from the past as well as our descriptive and analytical reading in the present generate multiple levels of narrativization vis-à-vis the role and agency of these historical subjects.

I focused here on Eastern Africans who worked in South Asia, but they were part of larger Afro-Asian interactions in intellectual, religious and legal realms across the Indian Ocean world. The interactions between Eastern African, South Asian and Southeast Asian Muslims in the maritime littoral in the premodern centuries enlighten us on the multidirectional and cosmopolitan stratums that contributed to the making of historical Islam and its laws. These ‘Indian Ocean Muslims’ also provide a different lens with which to look at Islamic legal history and they question the existing overemphasis on the Arab exclusivity at the cost of their own roles. ‘The Indian Ocean Islamic law’, as practiced from Eastern Africa to Eastern Asia, is not a mere mimicking of Arab versions of law and religion, rather it is a historical phenomenon of constant efforts among al-Zanjīs, Swahilis, al- Ḥabshīs, al-Hindīs and al-Jāwīs to rearticulate Islam and its laws according to their contexts. The legalistic interactions among these communities through the circulation of scholars and texts since premodern centuries helped them advance their understandings in different ways. Multiple contexts defined multiple characters and routes with outright contradictions. Yet, they all belonged to a cosmopolis of Islam; in it the Africans, Arabs and Asians created an equilateral triangle. The duty of a historian is not to disregard their contributions or to pass judgements on them; rather, it is to try to understand Islam the way they understood it.

Acknowledgements

I am thankful to Omar H Ali, Kenneth Robbins, Cliff Pereira and Sonja Zweegers for their comments on earlier versions of this article which have appeared in the IIAS Newsletter 76 (2017):8-9 and in the Black Ambassadors of Politics, Religion, and Jazz in India: Afro-South Asia in the Global African Diaspora, edited by Omar H. Ali, Kenneth X. Robbins, Beheroze Shroff and Jazmin Graves (Greensboro: University of North Carolina, 2020): 34-47. I am also indebted to the joint research fellowship of the International Institute for Asian Studies (IIAS), and the African Studies Centre Leiden (ASC), the Netherlands, for supporting this research in 2016-2017.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. See, for example, Wink, Al-Hind, vol. 1, 69–71; Lakshmi, The Malabar Muslims; Forbes, “Southern Arabia and the Islamicization,” 805; Cherian, “Genesis of Islam in Malabar,” 8; and Ilias, “Mappila Muslims,” 444.

2. The works of William Clarence-Smith, Edward Alpers and Gwyn Campbell are the best examples as they focus on the procedural questions related to enslavement, its legality, economy, implications, etc. Alpers, Ivory and Slaves; Alpers, African Diasporas; Campbell, Abolition and its Aftermath; Campbell, Structure of Slavery; Clarence-Smith, Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade; and Clarence-Smith, Islam and Abolition of Slavery.

3. For example, see Ali, African Dispersal in Deccan; Robbins and McLeod, eds. African Elites in India; and Ali, Malik Ambar.

4. Different Arab geographers, travellers and chroniclers provide various Arabic names for the ocean in connection with Eastern Africa. Yāḳūt al-Ḥamawī al-Rūmī (575–626/1179-1229) says Baḥr al-Zanj is the Indian Ocean itself (huwa Baḥr al-Hind bi-ʿaynih); Masʿūdī (282–345/896-956) says the same for Baḥr al-Ḥabashī, whereas he limits Baḥr al-Zanj as only the ocean’s western part. In contrast, ʿAbdullah al-Bakrī al-Andalusī (d. 487/1094) calls Baḥr al-Ḥabashī only its western part. However, Masʿūdī’s use of the term for the entire ocean is persuasive and he uses it all across his text. See Masʿūdī, Murūj̲ al-d̲hahab, vol. 1, 70–113, 252–267, vol. 2: 281, 300, 335, 432–3; al-Ḥamawī al-Rūmī, Mu’jam al-buldan, vol. 1: 343; and al-Andalusī, Muʿjam ma istaʿjama 381; cf. L. Marcel Devic, Le Pays des Zendjs.

5. de Silva, “‘Indian Ocean’ but not ‘African Sea’.”

6. Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, Riḥla, 572.

7. On the port and its historical significance, see Anchilath, Malabārile Islāminte; Bouchon, Mamale de Cananor.

8. Muhammad, Arabi Sāhityattinu Kēraḷattint̲e, 62–3.

9. al-Mahfanī, Qayd al-jāmiʿ al-hādī. Ponnāni Makhdūmiyya Library has two uncatalogued and unnumbered manuscripts with slight variations. Union Catalogue of Oriental Manuscripts of the Göttingen Academy of Sciences and Humanities enlists two other manuscripts belonging to the Universitäts- und Stadtbibliothek Köln (5 P 50–01 and 5 P 50–02).

10. Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, Riḥla, 572–3.

11. H.A.R. Gibb translates the term ‘Sudān’ as ‘negros’ (from sawdān). See Gibb, Travels of Ibn Battuta, vol. 4, 810. It is not the present-day Sudan. The term “Bilād as-Sūdān” in premodern Arabic geographical literature stands for West Africa, what we identify today as the Sahel (Gao, Timbuktu and the Songhai Empire). Ibn Baṭṭūṭa visited the region between 1346 and 1349 after his travels in India, hence this comparison. I am thankful to Cliff Pereira for this important remark.

12. al-Fāsī, Shifāʾ al-gharām, 539–42.

13. Kooria, “Un agent abyssinien et deux rois indiens,” 75–103.

14. Schimmel, Islamic Names, 70–2.

15. Lewis, Race and Slavery in the Middle East, 113.

16. This is not to forget that the name also was used by a Byzantine slave who was a calligrapher. Schimmel, Islamic Names, 71.

17. al-Fāsī, Shifāʾ al-gharām, 540.

18. Narayanan, Cultural Symbiosis, 38–41.

19. Annual Report on Indian Epigraphy (henceforth ARIE)1947–8, B 94; ARIE 1965–6, D 58; and Desai, A Topographical List, no. 1059, 101–2.

20. ARIE 1947–8, B 94; ARIE 1965–6, D 58; For this summary’s reproduction, see for example: Desai, A Topographical List, 101–2; and Shokoohy, Muslim Architecture, 194–5.

21. Narayanan, Cultural Symbiosis, 61: Bismillahi rahmanirrahim layilaha illalah aliludin umarul umarlhum masud hakim malik dinar aliyil mavhud… abdul kadir….

22. Shokoohy, “Sources for Malabar Muslim Inscriptions,” 9–11.

23. Shokoohy reads this word as البئر, but it appears more to be العتيق, which also makes more sense as I shall describe in a while. Also, the ASI report mentions the word العتيق that does not appear in Shokoohy’s reading.

24. The ASI epigraphist and Shokoohy read this name as ريحان while the م is clearly visible before ر, as well as the diacritical dot of ج. The ي and its double diacritical dots are not there for it to be ريحان. See ARIE 1947–8, B 94; ARIE 1965–6, D 58; and Shokoohy, “Sources for Malabar Muslim Inscriptions,” 10.

25. Ghosh, In an Antique Land.

26. Goitein and Friedman, eds. and trans., India Traders of the Middle Ages, 138, 603–604. In p. 153, they also note that ‘[h]e was evidently a Muslim.’

27. Schimmel, Islamic Names, 70-1.

28. al-Qalqashandī, Ṣubḥ al-aʿshā fī kitābat al-inshāʾ, vol. 5, 489.

29. On the narratives of early Islamic arrival in the Malabar coast, see Kugle and Margariti, “Narrating Community”; Prange, Monsoon Islam.

30. Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, Riḥla, 594.

31. Forbes and Ali, “The Maldive Islands”; cf. Forbes, “Archives and Resources for Maldivian History.”

32. Forbes and Ali, “The Maldive Islands,” 19. However, an edited and published version of the source does not provide such references to Africa slaves, although it does discuss the murder of a judge by the ruler. Tāj al-Dīn, Tārīkh Islam Dībā Maḥal, vol. 1, 15.

33. Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, Riḥla, 577.

34. Ibid., 564.

35. Ibid., 575.

36. Prange, Monsoon Islam, 136.

37. Annual Report on Indian Epigraphy 1965–1966, no. D53; and Shokoohy, Muslim Architecture, 168.

38. Kooria, “Cosmopolis of Law.”

Bibliography

- Primary Sources

- al-Andalusī, B. Muʿjam ma istaʿjama min asmā’ al-bilād wa al-mawādi’. Edited by Mustafa al-Saqā. Beirut: ʿAlam al-Kutub, 1945.

- Annual Report on Indian Epigraphy 1947-48. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India, 1949.

- Annual Report on Indian Epigraphy 1965-1966. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India, 1967.

- al-Fāsī, T. A.-D. Shifāʾ al-gharām bi akhbār al-Balad al-Ḥarām. Edited by ʿAlī ʿUmar. Cairo: Maktabat al-Thaqāfat al-Dīniyya, 2008.

- Goitein, S. D., and M. A. Friedman, eds. and trans. India Traders of the Middle Ages: Documents from the Cairo Geniza, “India Book”. Leiden: Brill, 2008.

- Ibn Baṭṭūṭa. Riḥlat Ibn Baṭṭūṭa: Tuḥfat al-nuẓẓār fī gharāʼib al-amṣār wa-ʻajāʼib al-asfār. Edited by Muḥammad ʿAbd al-Munʿim al-ʿUryān and Musṭafā al-Qaṣṣāṣ. Beirut: Dār Ihyāʾ al-ʿUlūm, 1987.

- Al-Ḥamawī al-Rūmī, Y. Mu’jam al-buldān, 5 vols. Beirut: Dār Sādir, 1977.

- al-Mahfanī, F. Ḥ. B. A. Qayd al-jāmiʿ al-hādī: mukhtaṣar fī aḥkām al-nikāḥ. Manuscript, Dubai: Juma AI-Majid Center for Culture and Heritage, 679405.

- al-Masʿūdī, A. A.-Ḥ. ʿ. Murūj al-d̲hahab wa maʿādin al-jawhar. Edited by Yūsuf al-Biqāʿī. Vol. 4. Beirut: Dār Ihyā al-Turāth al-ʿArabī, 2011.

- al-Qalqashandī, A. Ṣubḥ al-aʿshā fī kitābat al-inshāʾ. Vol. 14. Cairo: Dār al-Kutub al-Sulṭāniyya & Maṭbaʿat al-Amīriyya, 1919.

- Tāj al-Dīn, A.-Q. Ḥ. Tārīkh Islam Dībā Maḥal. Edited by Hikoichi Yajima. Vol. 2. Tokyo: Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, 1982.

Secondary Sources

- Ali, O. H. Malik Ambar: Power and Slavery across the Indian Ocean. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Ali, S. S. African Dispersal in Deccan: From Medieval to Modern Times. Hyderabad: Orient Longman, 1996.

- Alpers, E. A. Ivory and Slaves: Changing Pattern of International Trade in East Central Africa to the Later Nineteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1975.

- Alpers, E. A. African Diasporas: A Global Perspective. London: Routledge, 2010.

- Anchilath, A. Malabārile Islāmint̲e Ādhunika-Pūrva Caritram. Kottayam: Sahithya Prakarthaka Sahakarana Sanhgam, 2015.

- Bouchon, G. Mamale de Cananor: Un Adversaire de l’Inde Portugaise (1507-1528). Geneva: Droz, 1975.

- Campbell, G. The Structure of Slavery in Indian Ocean Africa and Asia. London: Frank Cass, 2006.

- Campbell, G. Abolition and Its Aftermath in the Indian Ocean, Africa and Asia. London: Routledge, 2012.

- Cherian, A. “The Genesis of Islam in Malabar.” Indica 6, no. 1 (1969): 1–13.

- Clarence-Smith, W. Islam and Abolition of Slavery. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Clarence-Smith, W. The Economics of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade in the Nineteenth Century. London: Routledge, 2013.

- de Silva, C. “‘Indian Ocean’ but Not ‘African Sea’: The Erasure of East African Commerce from History.” Journal of Black Studies 29, no. 5 (1999): 684–694. doi:10.1177/002193479902900507.

- Desai, Z. D. A. A Topographical List of Arabic, Persian and Urdu Inscriptions of South India. New Delhi: Indian Council of Historical Research, 1989.

- Devic, L. M. Le Pays des Zendjs ou La Côte Orientale d’Afrique au Moyen Age. Paris: Librairie Hachette, 1883.

- Forbes, A. D. W. “Southern Arabia and the Islamicization of the Central Indian Ocean Archipelagoes.” Archipel 21 (1981): 55–92. doi:10.3406/arch.1981.1638.

- Forbes, A. “Archives and Resources for Maldivian History.” South Asia: Journal of South Asian Studies 3 (1980): 70–82. doi:10.1080/00856408008723000.

- Forbes, A., and F. Ali. “The Maldive Islands, Indian Ocean, and Their Historical Links with the Coast of Eastern Africa.” Kenya Past and Present 12 (1980): 15–20.

- Ghosh, A. In an Antique Land. London: Granta, 1993.

- Gibb, H. A. R. Travels of Ibn Battuta, A.D. 1325-1354. Vol. 4. London: Hakluyt Society, 1994.

- Ilias, M. H. “Mappila Muslims and the Cultural Content of Trading Arab Diaspora on the Malabar Coast.” Asian Journal of Social Science 35, no. 4–5 (2007): 434–456.

- Kooria, M. “Cosmopolis of Law: Islamic Legal Ideas and Texts across the Eastern Mediterranean and the Indian Ocean Worlds.” PhD Diss., Leiden University, 2016.

- Kooria, M. “Un agent abyssinien et deux rois indiens à La Mecque: Interactions autour du droit islamique au XVe siècle.” Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales 74, no. 1 (2019): 75–103. doi:10.1017/ahss.2019.140.

- Kugle, S., and R. E. Margariti. “Narrating Community: The Qiṣṣat Shakarwatī Farmāḍ and Accounts of Origin in Kerala and around the Indian Ocean.” Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 60, no. 4 (2017): 337–380. doi:10.1163/15685209-12341430.

- Lakshmi, L. R. S. The Malabar Muslims: A Different Perspective. New Delhi: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

- Lewis, B. Race and Slavery in the Middle East: An Historical Enquiry. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Muhammad, K. M. Arabi Sāhityattinu Kēraḷattint̲e Saṃbhāvana. Tirūraṅṅāṭi: Ashrafi Book Centre, 2012.

- Narayanan, M. G. S. Cultural Symbiosis in Kerala. Trivandrum: Kerala Historical Society, 1972.

- Prange, S. Monsoon Islam: Trade and Faith on the Medieval Malabar Coast. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

- Robbins, K. X., and J. McLeod, eds. African Elites in India: Habshi Amarat. Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing, 2006.

- Schimmel, A. Islamic Names. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1989.

- Shokoohy, M. Muslim Architecture of South India: The Sultanate of Ma’bar and the Traditions of the Maritime Settlers on the Malabar and Coromandel Coasts (Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Goa). London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2003.

- Shokoohy, M. “Sources for Malabar Muslim Inscriptions.” In Malabar in the Indian Ocean: Cosmopolitanism in a Maritime Historical Region, edited by M. Kooria and M. N. Pearson:, 1–63. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Wink, A. Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World. Vol. 1: Early Medieval India and the Expansion of Islam, 7th-11th Centuries. Leiden: Brill, 1996.