ABSTRACT

Music’s ability to stimulate the emotions has long been fundamental to the aesthetics and reception of India’s elite rāga-based traditions. These emotions are generally studied aesthetically through the lens of ‘rasa’: the Sanskrit theory that proposes the musician’s role is to stimulate one of nine distilled emotional essences (rasas) that is ‘tasted’ by the audience. But here I ask the inverse question: what emotions arose when historical listeners were threatened with the loss of that crucial source of emotional stimulus; and how were those negative emotions expressed through historical texts? In this paper, I consider the Hayy al-Arwāh, a music treatise and tazkira (biographical collection) written by an ex-Mughal official from Delhi living in exile in Patna c. 1785–88, Miyan Zia-ud-din ‘Zia’. Zia-ud-din’s work reveals much about the emotions felt by musicians and music lovers affected by the violent political upheaval centred on late Mughal Delhi c1740–80 – but not in obvious ways. For such an emotional subject, his writing is curiously dispassionate. Nevertheless, I argue that his writing was impelled by one very powerful emotion in particular: anxiety. In order to approach the question I examine some alternative ways we might get at the emotional resonances of texts like the Hayy al-Arwāh: through genre, in this case the tazkira; the etic observations of modern neuroscience; and a turn outwards to writings of more emotionally loquacious contemporaries, here the Urdu poet Mir Taqi ‘Mir’. I argue it is precisely Zia-ud-din’s detatched attention to detail, as he traced hundreds of lost and scattered musicians and listeners, that reveals the emotional driving force behind the writing of the Hayy al-Arwāh to be a deep and abiding anxiety engendered by the very real existential threat of war and exile to the music of late Mughal Delhi. In writing the Hayy al-Arwāh, Zia-ud-din acted as witness and record keeper for his community to insure against the potential loss of the music of his beloved homeland. At the same time, the work of gathering and reporting information acted to alleviate his anxiety over the threatened disappearance of what was to him a most important source of personal solace.

In his 1666 Persian treatise on the music of Hindustan, Saif Khan ‘Faqirullah’ summarized in one line what the Mughals thought music was, and what it was for: ‘To arouse tender sympathy in the heart is music’s entire essence, and its result.’Footnote3 The idea that music has the power to stimulate, express, alter, and release emotions seems to be one of its few true universals across human cultures.Footnote4 References to music’s special affective powers abound in global literature dating from ancient times to the present day,Footnote5 although it is really only since the ‘affective turn’ in academic music studies c. 2000 that modern scholars have begun to focus on the link between music and emotions in a more systematic and sustained manner.Footnote6 But affect has played a prominent role in the study of certain musical traditions long before this recent theoretical turn to musical emotionsFootnote7 – in particular, the rāga-based art-music systems of the Indian subcontinent that we now call Hindustani music in the North and Karnatak music in the South.

In relation to the late Mughal era (1658–1858), I use the terms ‘elite’ or ‘art’ music to refer to that limited set of Hindustani rāgas (melodic modes), tālas (rhythmic cycles), songs and instrumental forms performed by hereditary communities of professional performer that were patronized by North Indian social elites of all backgrounds in this period,Footnote8 and that were aestheticized and canonized in Persian and Sanskrit music-technical and philosophical writings of the time (‘ilm-i mūsīqī, saṅgīta-shāstra); this field of discourse, practices, performers, and modes of listening became known as ‘classical’ in the twentieth century.Footnote9 In the late eighteenth century, with which this article is concerned, ‘these forms were principally the rāgs themselves, and a set of virtuosic song genres in rāg and tāl composed in courtly registers of North Indian languages: dhrupad, khayāl, ṭappa … and instrumental forms on the rudra vīṇā, rabāb, pakhāwaj, sārangī … sitār [and] tabla’.Footnote10 For nearly two millennia until the present day, music’s perceived ability to transform the emotions of its audiences has been central to the aesthetics and reception theory of India’s elite rāga-based traditions;Footnote11 this is especially so of the canonical Mughal theoretical writings on music c. 1658–1858 with which my broader work is concerned.Footnote12

Given this crucial emphasis on emotion, the ostensibly mainstream treatise of late Mughal gentleman-amateur musician Miyan Zia-ud-din ‘Zia’ (b.c. 1725–30, d. after 1785) poses a distinct puzzle, due to its almost entire avoidance of emotional language.Footnote13 Zia-ud-din’s Hayy al-Arwāh, the Everliving Spirits, is a unique and important treatise on the elite musical traditions of late Mughal Hindustan written c.1785–88, but including material stretching back to the cultural Golden Age of the reign of Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah ‘Rangile’ (r. 1720–48).Footnote14 The Hayy al-Arwāh splits roughly into two halves and combines a well-informed summary of canonical and contemporary music-technical knowledge with a tazkira (‘memorative communication’ or biographical collection) containing short biographies of Hindustani musicians and their extended networks. The first three chapters of his treatise are on the science of music (‘ilm-i mūsīqī), and cover (1) the origins of music according to Arab, Persian, and Indian philosophies; (2) the musical system of Iran, which was still in partial use in India at that time;Footnote15 and (3) the Hindustani musical system (sarūd-i Hindī), which takes up most of the first half of the treatise.Footnote16 For this third chapter, Zia-ud-din drew on the contemporary knowledge taught to him in person by his master-teacher or ustād, Muhammad Shah’s chief musician Miyan Anjha Baras Khan kalāwant; but he also cited several of the canonical Mughal treatises on Hindustani music written in Persian in the seventeenth century, including the Ma‘rifat al-Arwāh, Khwaja Muhammad Salih’s Rāg Prākāsh, Faqirullah’s Rāg Darpan, and especially the Tarjuma-i Kitāb-i Pārijātak of Mirza Raushan ‘Zamir’.Footnote17

The second half of the Hayy al-Arwāh, Chapter Four, constitutes Zia-ud-din’s tazkira of hundreds of North Indian musicians, nearly all of whom were connected with Mughal Delhi and its imperial walled city of Shahjahanabad,Footnote18 and many of whom Zia-ud-din had himself heard and befriended over a period of about forty years.Footnote19 Zia-ud-din’s beloved homeland was the Mughal imperial city , Shahjahanabad, where he was born. But in the late 1780s, he was writing from Patna in long-term exile, having personally endured one of the most intense periods of upheaval and terror in Delhi’s long history. Beginning with Nadir Shah’s invasion of Delhi in 1739, and rising to a tumultous peak during the years 1757–61 – a period Zia-ud-din referred to as the ‘scattering’ of Shahjahanabad – the Mughal capital was repeatedly overrun and sacked by invading armies intent on plunder, revenge, and conquest, ending in Afghan leader Ahmad Shah Abdali Durrani’s brutal seizure and sacking of the city in 1761, and a mass exodus of Delhi’s inhabitants. Zia-ud-din’s tazkira is concerned with what happened to music, musicians and patrons and where they went during and after these violent decades. It combines information on the pre-Muhammad Shah period taken from ‘Inayat Khan Rasikh’s pioneering musicians’ tazkira of 1753, the Risāla-i Zikr-i Mughanniyān-i Hindūstān,Footnote20 with Zia-ud-din’s own memories of musical life in Delhi before he left in 1754, and information he had meticulously gathered about what had happened to Shahjahanabad’s scattered musicians over the past thirty years he had resided in the eastern regions, from musicians who were passing through.Footnote21

It is a puzzle, therefore, on many counts, that both his technical commentary, which should concern emotion (he certainly knew the theoretical discourse), and especially his tazkira, which records with great precision and detail such unsettling events as the violent deaths of personal friends, should be so apparently empirical and devoid of emotive language. Zia-ud-din’s verbal reserve also makes his text difficult to work with as a source for the history of emotions in late Mughal India. Perhaps counterintuitively, then, in this paper I am going to argue that what impelled Zia-ud-din to write his treatise was indeed emotion, and one very powerful emotion in particular: anxiety. What is more, I shall suggest, it is precisely in Zia-ud-din’s emotional restraint and detached attention to detail in tracing what happened to hundreds of lost and scattered musicians and listeners, that the emotional driving force behind the writing of the Hayy al-Arwāh is revealed as a deep and abiding anxiety engendered by the ongoing existential threat he perceived to the imperial musical traditions of Delhi – and his own potential loss of the personal emotional solace provided by Hindustani music.

In order to help make emotional sense of the Hayy al-Arwāh as a text embodying anxiety, I will firstly suggest some alternative ways through which we might understand his work: not through the specific language of emotions and an interior self, because they are not available to us (and in any case the pre-colonial Persianate self was always a social, ‘networked self-in-conduct’Footnote22), but through genre and the communal self; the etic observations of modern neuroscience; and a turn outwards to the writings of Zia-ud-din’s more emotionally loquacious contemporary, Mir Taqi ‘Mir’.

The first place to turn is a consideration of genre in the context of eighteenth-century Mughal India; in this case the Persian-language tazkira. ‘The tazkira, literally “remembrance, memory”, is a major and very old genre of Persian literature (and later other languages) that is understood as generally factual in nature. At root, each tazkira is a collection of short biographies that tell the life stories of a discrete set of people, chosen by the author according to a specific, personal or communal, logic as to who was worthy of remembrance.’Footnote23 While tazkiras at face value tell the collective history of a community of people – poets, Sufis, noblemen, and in Zia-ud-din’s case musicians – who and what is represented in them is inevitably chosen and shaped into narratives by the individual author. Tazkiras are not repositories of neutral facts. As well as delimiting community, they are at a profound level self-representations – ‘the author creates his community, one which in turn produces this self-of-the-author as figure, a self relational to and indivisible from community’.Footnote24 They thus qualify as ‘ego-documents’ that may tell us something about how the author perceives and wishes to present their interiority through their social networks.Footnote25

Ego documents – first-person writings such as journals, letters and autobiographies – have been key sources for the history of the emotions in Europe and its settler colonies as important windows onto the interior emotional self-fashioning of the author. In a crucial article, Pernau points to the relative dearth of similar materials for Persianate South Asia, and the consequent need to consider unusual sources.Footnote26 As Kia argues, tazkiras like Zia-ud-din’s qualify as sources of information about individual selves, and not merely because he used the first person from time to time. ‘Tazkirahs as a whole and their individual entries varied in telling ways,’ she writes: ‘the act of writing such a text was autobiographical, but one where the auto is not self-referentially defined but accumulated in the context of different social relationships throughout a lifetime of learning, travel and service.’Footnote27 In other words, the community Zia-ud-din wrote about and the things they and he most cared about – the social and cultural contents and contexts of his tazkira – are as much, perhaps more, of a key to his emotional habitus as any use of emotional language.

What is especially important here is that anxiety over potential loss and increased competition for scarce resources (and its backward-looking corollary, melancholy or nostalgia at past loss) has been identified by several scholars of the poetical tazkira as a key impetus for the increase in tazkira production in India during the second and third quarters of the eighteenth century, which precisely corresponds with Zia-ud-din’s lifespan.Footnote28 This scholarship suggests further that anxiety may be expressed through the act of writing, and choosing what and how much to write, not necessarily simply how.

This leads us to our second port of call: modern, etic studies of anxiety as an affective disorder rooted in neurophysiology, which, as a process, has remained unchanged in modern humans globally for as long as we have records, and is part of an intrinsic affective repertoire demonstrably manifest in all vertebrates. Critical to my argument here is Kurth’s recent empirical work that demonstrates, firstly, that anxiety, like fear or sadness, is a biocognitive emotion ‘that combines a core [biological] affect programme with a culturally shaped control system;’ and, secondly, that anxiety is not the same as fear.Footnote29 Fear and anxiety are distinct biocognitive emotions; in both animals and humans they arise from different stimuli, and result in different behaviours. They are both automatic ‘negatively valenced’ and ‘future oriented’ defensive responses to threats. But fear is ‘triggered by clear and present dangers,’ and precipitates the well-known behavioural responses of fight, flight, or freeze. In contrast, anxiety is ‘triggered by threats and challenges that are unpredictable, uncontrollable, or otherwise uncertain in nature,’ and activates ‘patterns of risk-assessment and risk-minimization behavior’ aimed at mitigating that uncertainty.

Crucially for my argument concerning Zia-ud-din’s musical writings, these patterns include ‘epistemic behaviors (e.g. deliberation, reflection, information-gathering)’ that help individuals evaluate the threat or risk, and help them ‘determine what the correct thing to do is.’ While excessive anxiety can be crippling, it has long been known empirically that moderate anxiety can be productive, acting as a regulating device helping individuals to perform tasks better and make better decisions. (Indeed the majority of extant literature on music and anxiety concerns ‘performance nerves’ and how to help musicians control and channel them effectively.Footnote30) Thus, ‘by working principally to orient us toward questions about what we should do … anxiety can promote better moral decision making … it is an emotion that plays an important role in agency.’ In other words, anxiety propels information-rich, solution-focussed actions that are designed to mitigate negative outcomes when faced with uncertain or uncontrollable threats.Footnote31 This is precisely what I think was in operation in Zia-ud-din’s writing of the Hayy al-Arwāh.

Our third move is to look sideways at the writings of members of Zia-ud-din’s community in Delhi, to build their emotional reflections into a collective understanding of the (communal) self in jeopardy. As a young man, Zia-ud-din took part in the same intimate poetical and musical gatherings in Delhi as the great Urdu poet, Mir Muhammad Taqi ‘Mir’ (1723–1810), who included an approving entry on the younger man in his 1752 tazkira of Urdu poets, the Nikāt al-Shu‘arā.Footnote32 Mir’s own emotion-laden writings on Delhi’s destruction and his own long exile in his well-known autobiography, the Zikr-i Mīr (Mir’s Remembrances), and in his celebrated poetry, thus provide a crucial foil in this paper for Zia-ud-din’s much more restrained reflections on the same events.Footnote33 Unlike Zia-ud-din, Mir expressed a number of negatively valenced emotions in vivid descriptive terms, including anxiety.

In 1760, expressing his desire to take his family away from the desperate uncertainty facing Delhi under Abdali’s repeated onslaughts, Mir described his emotional state in the same elemental terms as in my second epigraph above. The state he described was one of distressing imbalance – of being all fire and water due to the heat and cold of that most disordered of times and places in which he, and Zia-ud-din, lived. The emotion Mir was expressing through this metaphor was anxiety: the universal human emotional response to the kind of uncertain but existential threats exemplified by the upheaval Mir and Zia-ud-din endured during their lifetimes. Ironically, as we shall see, it was precisely – indeed, primarily – such states of emotional uncertainty that the Mughals believed the Hindustani rāgas could soothe and alleviate by bringing the mind and body back into equanimity. Music, according to the great Mughal ideologue Abu-ul-fazl, was an attested medicinal tonic that could restore contentment to the listener consumed with the cares of the world. And music, in the uncertain world of mid eighteenth-century Delhi, was under severe threat.Footnote34

My argument below unfolds as follows: Mughal aficionados and intellectuals percieved music, and particularly the Hindustani rāgas, to be one of the most powerful technologies at their disposal to regulate and soothe their emotions. Because elite music, before the era of the sound recording, was fundamentally a social activity requiring a level of intimacy within designated spaces, and because the music itself was handed down orally and aurally by professional musicians, the death and scattering of the musicians and listeners involved in Delhi’s famous musical gatherings c. 1757–61, and the destruction of venues for listening, were major threats to the survival of that source of emotional regulation and satisfaction. Zia-ud-din was enthusiastically involved in Delhi’s socio-musical networks, and the very real threat to this world provoked ongoing anxiety in him that it would be lost. Zia-ud-din’s position as a disciple of the senior lineage of hereditary musicians and as a Persianate intellectual steeped in written music theory, however, meant he could mitigate that threat. In writing his treatise and his tazkira, he therefore took it upon himself to act as witness and record keeper for his community. At the same time the act of gathering and reporting information helped to alleviate his anxiety.

Let us then turn first to why the prospect of music’s loss, fragmentation, or corruption provoked such anxiety amongst Mughal music lovers. As I have demonstrated elsewhere, to Mughal-era listeners, affective power (asar or ta'sīr) was the primary frame for interpreting and experiencing the Hindustani rāgas.Footnote35 By the late eighteenth century, the emotions aroused by elite musical forms had been filtered through the Sanskritic aesthetic lens of rasa for well over a thousand years. Rasa is an affect-based theory of performance and reception first propounded in the early Sanskrit treatise, the Nāṭyashāstra (first few centuries C.E.), and deepened and disseminated over the centuries through a continuous stream of writings in Sanskrit and, later, vernacular languages and Persian, the Mughal language for elite Indian music theory.Footnote36 The rasas (‘juice, essence’) are nine distilled emotional essences: the erotic essence, which is experienced as desire (shṛṅgāra), tragic = grief (karuṇa), comic = amusement (hāsya), violent = anger (raudra), heroic = determination (vīra), fearful = fear (bhayānaka), macabre = revulsion (bībhatsa), fantastic = amazement (adbhuta), and (a later addition) peaceful = tranquillity (shānta).Footnote37 Musically, rasa theory proposes that the performer’s role is, through a perfect rendition of the rāga’s melodic contours, to produce the rasa temporarily between musician and audience in order for it to be ‘tasted’ in the transient moment of performance by the listening connoisseur, the rasika or ahl-i zauq (both of which in an aesthetic context mean the ‘one who tastes emotion/delight’; see below).Footnote38

In practice, however, a slightly different, somewhat more impressionistic set of emotions than the classical nine seems to have been tasted by Mughal audiences of elite rāga-based music, as continues to be the case in the present day.Footnote39 Sanskrit, Brajbhasha, and Persian treatises written, translated, and studied by Mughal-era connoisseurs described the nine rasas, and some connected them with particular rāgas or swaras (individual notes) – Zia-ud-din for instance connected six of the rasas with the six principal male rāgas of the rāgamāla (Bhairav = shṛṅgāra, Malkauns = adbhuta, Hindol = [hāsya?], Shri = raudra, Dipak = karuṇa, Megh = vīra).Footnote40 But these theoretical correlations were the subject of such wide and varied disagreement that scholars such as Widdess have dismissed them as fundamentally artificial.Footnote41 Some rasas were not deployed musically. No musician would ever wish to disgust their listeners with bībhatsa rasa, for instance; indeed, in Mughal-era treatises patrons were strictly enjoined not to employ musicians who might disgust their guests.Footnote42

In any case, of far greater importance than the rasas per se to Mughal understandings of the correct emotional effect of each rāga, was the powerful hold over the Mughal imagination of the rāgamālā tradition of painting the six male rāgas and thirty female rāginīs as heroes, heroines, semi-divine beings, and deities in standardized but vivid and complex emotional scenarios.Footnote43 These richly layered icons allowed a more expansive range of emotional shades connected with key rasas to be enjoyed through musical listening.Footnote44 Powers, for instance, argued that many of the rāga and rāginī icons in this period explored the multiple different emotional facets of one key affective essence, the ‘king of rasas’, shṛṅgāra.Footnote45 Likewise, Zia-ud-din, whose writing on music lies at the heart of this paper, wrote that the entire Brajbhasha language in which Hindustani art songs were composed was ‘the idiom of shṛṅgāra rasa, shṛṅgāra rasa being the beauty and love (husn o ‘ishq) of women and men’.Footnote46 Multiple shades of a single rasa might be considered to have rather more conceptual affinity with the Nāṭyashāstra’s notion of the thirty-three transitory emotions or bhāvas that give rise to the rasas, than with the rasas themselves.Footnote47 Indeed, although the Mughal connoisseurs and master musicians who wrote the canonical treatises in Persian on the Hindustani rāgas c. 1650–1700 certainly knew what the nine rasas were technically, ‘rasa,’ wrote Faqirullah much more sweepingly, ‘means inflaming the passions and pleasing the heart through listening’.Footnote48

It is important to note, in this regard, the Suficate filter through which Mughal writers understood the rasa concept.Footnote49 The word zauq, meaning both ‘taste’ and ‘delight, pleasure’, which theorists like Mirza Khan used to translate the word rasa, was used in Sufi discourse and in Persian and Urdu devotional poetry to refer to ‘a form of intuitive perception’ or ‘taste’ that, bypassing reason, enabled the human Lover to gain true knowledge of the divine Beloved;Footnote50 in other words, ahl-i zauq could in a Sufi context refer to someone of profound spiritual insight, not just/as well as someone who was expert in appreciating aesthetic delight. Similarly, it is important to note that rasika was likewise widely used in bhakti devotional literature as a term for the devotee, e.g. of Lord Krishna.Footnote51 There was a long Sufi history in India going back to the medieval Hindavi premakhyāns (romances) of interpreting the nine rasas as stages on the Sufi path to annihilation (fanā’).Footnote52

But the deep affective polysemy of early modern rāgamālā iconography, experienced in perhaps less technically ‘correct’, more instinctive and impressionistic, ways, also seems to have facilitated affinities – experiential common ground – between Indic and Persianate, Sufi, and Greco-Islamicate understandings of music’s powers.Footnote53 A smaller set of emotions affine with both Sufi experience and the Indic rasas seem to have been prioritized in Indo-Persian writings on the rāgas’ emotional effects. The most important of these were desire for the beloved (‘ishq) and grief and longing at the beloved’s loss or absence (firāq), with ecstatic joy, contemplative tranquillity, and arousing courage also valued among the rāgas’ emotional results.Footnote54 In Mughal-era writings on music in Persian, these emotions were contextualized within conceptual and literal translations of Sanskrit rāga and rasa theory; but their emotional vocabulary was rendered in Persianate terms and their interpretation steeped in Greco-Islamicate and Suficate understandings of emotion, the mind, and music’s powers.Footnote55 As Bijapur-based author Shaikh ‘Abd-ul-karim put it, for example, in his c.1630 translation of the classic thirteenth-century Sanskrit saṅgīta-shāstra, the Sangītaratnākara:

The rāgas are of four types: one [type of] rāga is of airy essence, one fiery, one watery, and one earthy … From listening to those rāgas that possess the airy essence, one’s heart will be buffeted by the grief of separation (firāq). From listening to those rāgas that possess the fiery essence, the stations of the heart will be inflamed with passionate love (‘ishq). From listening to those rāgas that possess the watery essence, the stations of the heart will be annihilated through proximate union (wisāl) with Divine Truth within the essence of the Glorious and Great Existence. From listening to those rāgas that possess the earthy essence, the stations of the heart will attain an excess of mystical knowledge (‘irfān), and know its [true] selfFootnote56

I have written about this extensively elsewhere,Footnote57 but in short, what is critical to note about Mughal-era intellectuals’ interpretations of Sanskrit rāga and rasa theory is that the emotional and, indeed, supernatural powers of the rāgas remained absolutely fundamental to Hindustani music’s ontology in the Mughal listener’s experience: its ‘entire essence, and its result’.Footnote58 The single aim that unified the canonical Mughal treatises was to explain which effects were produced by different rāgas and – more importantly – why.Footnote59 This is because the Mughals regarded the Hindustani rāgas as an indispensable, supernaturally powerful technology for use within Greco-Islamicate medicinal theories of mind and body to restore balance and harmony to the individual, the empire, and the natural world. Each rāga derived its ability to arouse desire, compassion, sorrow, joy, vigour, tranquillity, etc. in the individual listener – or to bring the rain, defeat enemies, light fires, bestow sovereignty, or calm wild beasts – from channelling the power of the astral bodies over the four elements out of which all things were made, and especially the humours of the human body and the faculties of the human mind. Mental and physical disease were caused by imbalance and disorder in the faculties and humours. The ideal state of health was equilibrium – a mental and physical equanimity to which the Mughals believed the correct choice of rāga could fully restore a disordered listener.Footnote60

The rāgas were thus most importantly an essential Mughal technology for fine-tuning an individual’s humours, faculties, and emotions, and for bringing the polity itself, supernaturally, into the power of auspicious balance.Footnote61 But the rāgas were also critical to the self-fashioning of the Mughal elites in a more worldly and socially grounded sense, too. Since at least the 1660s, listening to the ‘right’ kinds of Hindustani rāgas, instruments, and song forms in that most storied of gatherings for intimate listening, the Mughal majlis (pl. majālis), had set elite Mughal and Rajput men apart as a class from both grubby social climbers and the unwashed masses.Footnote62 Listening to and being moved by the Hindustani rāgas was not just crucial to Mughal health and wellbeing. It was fundamental, in the most visceral and passionate terms, to who the old Mughal elites were as a cohesive social and political collective. Hindustani music, in other words, was a centrally important social and cultural glue of what in modern terms we would call Mughal elite ‘identity’.Footnote63 The fundamental necessity of the rāgas’ critical emotional affordances to sustaining this elite class socially and politically, and not just individually or supernaturally, thus opens a unique window onto the history of other emotions in the late Mughal period that lie outside the classical nine-rasa theory.Footnote64

Zia-ud-din imbibed this knowledge of Hindustani music and its affective powers from his distinguished ustād, from his fellow connoisseurs, and from the musical treatises they passed between themselves. But his concern in the Hayy al-Arwāh, however – as is mine in this paper – was not on the powerful pleasant effects generated by musical listening in late Mughal Hindustan, as elaborated in this knowledge system. Instead, his work aimed to mitigate the overpowering negative emotions aroused when Mughal listeners were repeatedly threatened c. 1739–61 with the sudden and total loss of this affect-soaked musical world. ‘What of the people of Mughal Delhi?’ Carla Petievich wrote of the devastating human consequences of these violent decades:

Their entire sense of security had just been severely undermined … Their way of life, their culture, in fact their very identity, embodied in the capital city of Delhi, was threatened with obsoletion. [The poets] Sauda and Mir thought that the world as they had known it was destroyed and they had no idea of what would follow.Footnote65

One could say with equal truth: the very identity of the elites of Mughal Delhi, embodied in their savouring of the Hindustani rāgas in Delhi’s fabled majālis, was imperilled. A recipe for existential anxiety if ever there was one.

Like so many other inhabitants of Delhi, Zia-ud-din had his own life and the musical gatherings he loved turned upside down during these decades of violent disruption of his homeland, eventually having to flee and settle elsewhere. And like Sauda and Mir, his heart remained in Delhi, in the land he had lost. Zia-ud-din dedicated his Hayy al-Arwāh ultimately to the Mughal emperor in Delhi, Shah ‘Alam II (r. 1759–1806). But he named it after a more immediate dedicatee, Shah ‘Abd-ul-hayy, whom Zia-ud-din revered as a great music connoisseur: presenting a work on music to him was ‘like taking cumin to Kerman, or pepper to India’, he wrote.Footnote66 Much of what we know about Zia-ud-din and his text’s production has to be gained from internal evidence and parallel sources, as the only surviving manuscript, in the John Rylands Library, University of Manchester, has no original bindings or colophon. Fortunately, his tazkira contains a wealth of helpful detail that enables us to place both the author and his remarkable musical text.

Miyan Zia-ud-din ‘Zia’ was a well-connected minor Mughal official from Shahjahanabad who was born c. 1725–30, early enough to remember the glamour and luxury of Muhammad Shah’s Delhi before the Persian emperor Nadir Shah’s humiliating invasion in 1739.Footnote67 The often acerbic Mir regarded his younger contemporary favourably as a fresh-faced and sincere person with suitably deferential manners, of humble temperament, and much inclined to the ways of the Sufi faqīrs (mendicants).Footnote68 Mir’s impression of him tallies well with Zia-ud-din’s self-presentation. Like many other gentleman-amateurs of the time, he was a poet, a committed Sufi, and slightly more unusually an accomplished musician: a dedicated student of Miyan Anjha Baras Khan who was head of the most prestigious lineage of hereditary musicians in Muhammad Shah’s imperial atelier and a direct descendant of Tansen.Footnote69

In 1754, when the unstable and sadistic prime minister ‘Imad-ul-mulk blinded the Mughal emperor Ahmad Shah (r. 1748–54)Footnote70 and placed the puppet ‘Alamgir II (r. 1754–59) on the throne, Zia-ud-din left Delhi for Lucknow with his employer Iftikhar-ud-daula Mirza ‘Ali Khan.Footnote71 Before 1756 they had moved further east to Faizabad in Bengal,Footnote72 possibly in the service of Nawab Ahmad ‘Ali Khan Shaukat Jang, governor of Purnea (d. 1756); and they had returned to Lucknow by 1761. It is not clear when Zia-ud-din left Iftikhar-ud-daula’s employ, but in 1764 he was living in Sahibganj in Bihar, at which point he decided it was time to return to his homeland (watan) of Delhi. Sadly, the political situation in the imperial capital under the rule of Ahmad Shah Abdali’s Rohilla deputy Najib-ud-daula made this impossible. So instead, in about 1765 Zia-ud-din settled permanently in the great commercial hub of Patna (Azimabad) in Bihar on the Ganges River, which was by that time securely under the control of the British East India Company.Footnote73 At the time of writing, Zia-ud-din was working for Muhammad Quli Khan ‘Mushtaq’ (d. 1791).Footnote74 Mushtaq was a ‘clever musician’ and poet according to Sprenger, whose father Hashim Quli Khan had been chief of staff (dārogha) to the governor of Patna 1740–48, Nawab Zain-ud-din Ahmad Khan Haibat Jang.Footnote75 The Hayy al-Arwāh manuscript is undated, but Zia-ud-din wrote it between the death of Mirza Najaf Khan in 1782Footnote76 and the death of his own employer in 1791, and most probably between 1785 and 1788: in what is a highly Delhi-centric text, there is not a hint of Afghan marauder Ghulam Qadir’s horrendous blinding and torture of Shah ‘Alam II in August 1788.Footnote77

Zia-ud-din was thus writing as an elderly gentleman in his late fifties or sixties,Footnote78 looking back over the turbulent events of his life and times. As a Mughal insider who worked until the mid 1750s in the imperial capital, then fled eastward to Nawabi Lucknow and Bengal, finally coming to rest in British-run Patna, his perspective on this period of tumult is invaluable. Zia-ud-din had the dubious privilege of being an eyewitness to much of what he called the ‘turmoil/disorder’ (hangāma) or ‘disturbance/misfortune’ (āshob) that befell Mughal Delhi 1739–61, which led to the capital’s physical devastation (ghārat)Footnote79 and the ‘scattering (tafriqa) of the people of Shahjahanabad’ all over India.Footnote80 He was present for Nadir Shah’s brutal conquest of Delhi in 1739, the constant threats to the capital of Afghan, Rohilla, Maratha and Jat incursions 1748–54, and the violent overthrow of emperor Ahmad Shah. And Zia-ud-din could not return to his beloved Delhi because of the catastrophic events that most preyed on his mind, which he repeatedly called the ‘hangāma-i Abdalī’: the period 1757–61 when Abdali and the Marathas fought for control of the capital, ‘Imad-ul-mulk murdered ‘Alamgir II, and Shah ‘Alam II fled into exile, culminating in the devastating 1761 Battle of Panipat. But Zia-ud-din was also in Bihar and Bengal during the portentous events there that began the transfer of power from the Mughals to the British: Robert Clive’s defeat of Siraj-ud-daula at the 1757 Battle of Palashi, the multiple sieges of Patna that led up to the British defeat of the Mughal, Awadh, and Bengal armies at the Battle of Baksar in 1764,Footnote81 and the 1765 Treaty of Allahabad when Shah ‘Alam II ceded Bengal and Bihar to the British. Although Patna was largely peaceful over the next few decades, Zia-ud-din would also have witnessed first-hand the devastating effects of the 1769–70 Bengal famine, as Patna was badly hit; the best modern estimates are that 1.2 million people died of starvation.Footnote82

For most of his adult life, then, Zia-ud-din repeatedly endured and witnessed great trauma and upheaval, surviving, finally, to live in peace – but only in permanent exile from his beloved Delhi, the memory of whose social and cultural life remained always at the front of his mind. Why, then, did he choose a music treatise – of all possible genres of writing – as the vehicle for what he most wanted to preserve of his life and times for future generations to remember? And what were the main emotions detectable in his writing that propelled him to write it? Music’s power over the emotions and its connections with memory and selfhoodFootnote83 ultimately played a role in this choice – but only obliquely, at one remove. It is the ongoing emotional after-effects of trauma and exile on Zia-ud-din and those he cared about that scar the Hayy al-Arwāh throughout – but in markedly different ways than the more direct (and much more famous) reflections on the same events by his exact contemporary, the Urdu poet Mir, especially in his autobiography, the Zikr-i Mīr.

In their prose works, both Mir and Zia-ud-din wrote in first person from time to time. But while Mir recalled in vivid emotive language the fear and grief he and his community experienced over the destruction of their whole way of life, exemplified in Delhi’s physical devastation, Zia-ud-din’s language was curiously unemotional, even dry, especially considering the subject matter of his tazkira, which obsessively tried to pin down whether or not the scattered musicians of Shahjahanabad survived, and if they did, where they went to. In other words, as I set out in the introduction, I think the main emotion propelling the Hayy al-Arwāh was neither fear nor grief, but anxiety – Zia-ud-din’s ongoing anxiety over the longer-term existential threat to a crucial source of his people’s emotional solace and selfhood: the music of his Mughal homeland.

It is quite clear from their writing that both Mir and Zia-ud-din saw the hangāma-i Abdalī of 1757–61, the cataclysmic end of two decades of increasingly intense uncertainty and instability in the Mughal heartlands, as a particularly severe existential threat to their own lives and loved ones, and to the rich Mughal life of poetry and music they both loved almost more than life itself. I would like to compare their responses to the hangāma-i Abdalī, because the quite different flavours of their writings demonstrate the distinct behavioural responses engendered by fear, as Mir was personally caught up in the violence, and anxiety, as Zia-ud-din reacted to reports of the hangāma and its longer-term consequences from a geographical and temporal distance.

The mid-to-late eighteenth century in North India is famous for the genre of Urdu poetry known as the ‘city-disturber/disturbance’ or shahr-āshob, of which Mir was an acknowledged master. The genre was derived from earlier Persian models that joyously explored the Mughal cityscape through its palaces, bazaars, religious shrines, and musical and poetical gatherings (majlis, pl. majālis), all lavishly populated with ‘rascally boys’ of all trades, ‘slim, tall beauties’, and blissfully intoxicated lovers.Footnote84 But in contrast, many eighteenth-century poets of the Urdu shahr-āshob emptied and razed the city, in order to distil Mughal feelings of grief, desolation, and anxiety for the future in the wake of the mid-century destruction of their beloved capital.

We can’t identify with certainty which specific catastrophes in the period of Delhi’s travails inspired particular shahr-āshob verses by Mir,Footnote85 and, as Zahra Sabri has forcefully argued recently, Mir’s Persian prose autobiography, the Zikr-i Mīr, is better seen as a work of ādāb (manners, etiquette) presenting the kinds of emotions that should be felt by sophisticated Mughal men and showing off the most elegant and evocative language, rather than a work of plain fact and transparent autobiography.Footnote86 Nonetheless, at times Mir does address his experience of datable events in a direct but equally intense fashion. Like Zia-ud-din’s text, the first version of the Zikr-i Mīr was written in exile from the safety of the Jat fortresses of Kumher and Deeg, and completed in 1773 when Mir, too, considered himself to have crossed the threshold of old age.Footnote87 And, again like Zia-ud-din, Mir seems to have been especially consumed with the period of Abdali’s invasions c. 1757–61, which dramatically affected his own fortunes.Footnote88 There are two critical differences, however. Mir’s experiences of the hangāma-i Abdalī were direct, while Zia-ud-din’s were indirect. Mir also began writing about them almost straight away, between 1760 and 1771,Footnote89 whereas Zia-ud-din put pen to paper more than two decades after the fact. The immediacy of events for Mir may explain in part why his most potent expressed emotions were fear in the context of immediate threats to life and property; and grief and melancholy in the aftermath of destruction.Footnote90

In January 1760, the armies of the Afghan ruler Ahmad Shah Abdali and the leader of the Rohillas Najib-ud-daula routed the Maratha army ten miles north of Delhi, and descended upon the helpless city.Footnote91 Mir tells us that ‘the Marathas, in utter panic, did not even pick up [General Dataji Rao’s] corpse and left it lying by the river. The Rohillas, crossing over to this side, started a massacre, while the Marathas ran off into the wilderness in utter rout (hazīmat).’Footnote92 While many of the men of Shahjahanabad, including Mir’s patron Raja Nagar Mal, exhibited the same flight response, Mir ‘stayed behind to protect my family’, and prepared to fight. But the onslaught was terrible and relentless for over a week:

In the morning—which was like the morning of doomsday (Qiyāmat)—the armies of the shah and the Rohilla leader Najib-ud-Daula poured in and set about looting and killing … Roofs were dug up; walls were pulled down. Breasts were torn open; hearts were charredFootnote93 … A terrible host trampled the city and caused death and destruction to all and sundry … The New City [Shahjahanabad] was turned into rubble … Meanwhile the savages attacked the Old City and started killing its people … Thousands of wretches, in the midst of that raging fire, scarred their hearts with the mark of exile and ran off into the jungles, where, like lamps at dawn, they died in the cold air … It was a reign of tyrants. They stole and plundered, and enriched themselves obscenely, and did not spare even the women. They waved their swords and snatched away whatever they could grab. The people of the Old City could do nothing. You could say their hands and hearts had gone numb. They were stunned in their distress. On every doorstep there stood a blackguard; every street was a field of killing … The poor stood stiff with fear while those impudent fellows showered abuses on them … I was left destitute and penniless, and my humble dwelling … was leveled to the ground.Footnote94

And then, as suddenly as they had come, the armies of the Afghans and Rohillas vanished into the Aravalli hills, their attentions fixed on plunder elsewhere.

Mir’s description of the responses of the Old City’s inhabitants is especially interesting here. Some fled headlong, hopelessly, only to die in the wilderness of the bitter winter’s cold; but others froze stiff with fear, stunned, their hands and hearts numb, under the cosh of tyranny. Mir used specific literary techniques to make his audience themselves feel the fear of this moment, and sympathize with the horrors the people of Delhi had endured. Bear in mind that most Indian literature in this period was designed to be recited aloud to listeners.Footnote95 Naim notes that the passage I have italicized makes unusual use of eight idioms constructed on the word ‘hand’ (dast) in rapid succession.Footnote96 Mir wielded them in short, punchy sentences that would have left a Persian-literate audience stunned and reeling from the metaphorical weight of the blackguards’ fists and swords raining down on them, too, as they listened.Footnote97

Over the next six months, intense anxiety that the armies would return and overrun Shahjahanabad again set in. Unable to bear the uncertainty, Mir made a bold decision to ensure his family’s survival: ‘I went to the raja and submitted to him that I was in great distress (ātish o āb [fire and water]) due to the uncertain times (garm o sard [heat and cold]) and wished to go out of the city, to some other place where perhaps I might find some peace … I took all my dependents with me and set out on foot.’ Here, he uses almost identical language to his couplet above to describe the anxiety that led to this wise but drastic decision: due to the heat and cold of the times, he was all fire and water; by leaving his beloved Delhi he was seeking equanimity and peace.Footnote98

It was only later that he gave full expression to his grief for all that was lost. When he returned to Delhi with Raja Nagar Mal in February 1761, more than a month after Abdali had won the decisive battle of Panipat and pacified Shahjahanabad, Mir wrote:

I happened to take the road into the newly ruined city of Delhi, outside the walled city of Shahjahanabad. At every step I shed tears and learned the lesson of mortality … I could not recognize any neighborhood or house … Houses had collapsed. Walls had fallen down. The hospices were bereft of Sufis. The taverns were empty of revelers. It was a wasteland, from one end to the other … What can I say about the rascally boys of the bazaar when there was no bazaar itself? And what can I tell of my lover friends when there was nothing around of beauty? The handsome young men had passed on. The pious old men had passed away … Suddenly I found myself in the neighbourhood where I had lived: where I gathered my friends [sohbat mī-dāshtam, lit ‘kept company’] and recited verses—where I lived the life of love and cried many a night—where I fell in love with slim and tall beauties, and sang high their praises … This was where I had arranged joyous gatherings [bazm] with beautiful people … and lived a life worth the name. But now … every bazaar was a place of desolation, and every street a track into wilderness. I stood there and gazed in amazement. I was horrified.Footnote99

This famous passage is, of course, a shahr-āshob in sonorous prose, modelled on the joyful Persian shahr-āshobs of happier times, but with its sentiments reversed – the city full of devastating beauties now become the city devastated and empty.

The idea that nothing was left standing and no-one left alive was not in fact true. Zia-ud-din’s tazkira featured a number of musicians and musical patrons who were still living in the Old City and Shahjahanabad between 1761 and 1772 when Shah ‘Alam II himself returned from exile. And we know that elite music and poetry continued there as did Sufi life; all three, for example, cultivated by the great Sufi leader and poet Khwaja Mir Dard at his hospice in the Old City.Footnote100 That this was not, in reality, the end of Mughal Delhi and her people focusses our attention on Mir’s heightened emotional perceptions in 1761; and in particular the cause of his most intense grief – the great disruption of the living organism that was Delhi’s celebrated majlis, the intimate gathering for music, poetry, and friendship.Footnote101 Mir of course mourned the passing of the mentors, friends and lovers that filled the assemblies of his memories. But most of all he wept over the passing of the Mughal ‘life of love’ he had once enjoyed with them: the ephemeral ‘life worth living’ of poetry, song, love, feasting, and friendship that was generated nightly in those gatherings, and that dissipated daily ‘like lamps at dawn’.Footnote102 He wept not only over the assemblies’ past glories and their present deathly silence, but over the likelihood, given the evidence of his own eyes and heart, that they would never be revived.Footnote103

This point, and this passage, are critical to understanding Zia-ud-din’s focus on the musical world in his only known literary work, the Hayy al-Arwāh. As in Afghanistan under the Taliban and the ‘war on terror’ ever since, if the physical spaces in which music and poetry are performed are literally destroyed, and if the musicians and poets and listeners that populated those spaces are themselves dead and scattered, then the threat to the survival of the music and poetry they carry in their bodies is very real, as is the threat to the crucial emotional worlds they can conjure up with their tongues and fingertips.Footnote104 Such a threat is especially acute with a tradition like Hindustani music, for unlike poetry, the music itself has never been written down; the sounds of eighteenth-century Delhi are not reproducible from any written notation. They were passed on bodily, in the throats and hands of master musicians to their sons and carefully selected disciples, who in time themselves became masters.Footnote105 And they required listeners who were equally enculturated into those traditions through continuous exposure over generations, and had the time, money, and pavilions to spare for listening.Footnote106

What happens to a musical world when the chains of its existence all break at once?

It was precisely this possibility that lay at the heart of Zia-ud-din’s anxiety, which in turn, I argue, impelled him to write the Hayy al-Arwāh in order to bring the disordered musical world back under control, and to bear witness to all that had been lost and was still, he thought, under threat. In what remains, I wish to explore more deeply Zia-ud-din’s response to the extraordinary endangerment of his musical world and sense of Mughal selfhood, through the words of the tazkira that he wrote as the second half of the Hayy al-Arwāh. The style of his writing is in dramatic contrast to Mir’s: technical, detailed, factual, and emotionally distanced. This is in large part to do with genre: the Hayy al-Arwāh is not a memoir or poetry, but a scientific music treatise. However, more detatched and intellectual ‘epistemic behaviors (e.g. deliberation, reflection, information-gathering)’ aimed at ‘risk-minimization’ are also exactly what we would expect if this work’s fundamental emotional driving force was anxiety.Footnote107 Curiously for a work entitled the Everliving Spirits, references to the emotional impacts of music on human beings are restricted to a few gestures in the introduction, as was customarily required of music treatises in the canonical Indo-Persian tradition.Footnote108 Thereafter, Zia-ud-din’s use of language is largely technical and emotionally restrained, with minimal use of affective vocabulary or rhetorical effects, as in Mir’s repetition of dast, that might elsewhere be deployed sonically or musically to evoke emotions in the reader.Footnote109 Unlike Mir’s literary memoir or even more so his poetry, Zia-ud-din’s treatise is not the work of art itself. He is writing about the work of art, in its absence and under erasure. And it reads, as I have written elsewhere, as though he were ‘trying desperately to contain a torrent of rushing floodwater in a sieve.’Footnote110

What Zia-ud-din wrote down about the hangāma-i Abdalī and its impact upon the life of Delhi’s erstwhile music and musicians was derived from his painstaking recording of these musicians’ oral reports. His records are brief, but heavy on facts: on names of musicians, patrons, and places of patronage, and how they were all related. Delhi is at the centre of his personal ‘significant geography’:Footnote111 until mid century as a place of arrival, metaphorical and literal; and after its disturbance as a place of departure and retirement. From this point in time, a tripartite litany runs through Zia-ud-din’s narrative like streaks through marble. First, the calamity:

Second, the ‘scattering’, and the meticulous tracing of those who survived:

Third, the marking of those who had gone missing in the upheaval:

There are several important things to note here. The first is that although the hangāma-i Abdali was clearly the major turning point in Zia-ud-din’s history of Hindustani music through the lives of Delhi’s musicians and music lovers, he was not motivated to describe the hangāma’s horrors, nor to recall its immediate emotional resonances, simply to mark its centrality to what followed. His narrative, in other words, does not primarily concern either the fear or grief experienced by his contemporaries during these appalling events, or even his own in retrospect. Even when he wrote about musicians he knew personally who were killed during Delhi’s mid-century travails – the once-fabled beauty Allah Banda qawwāl who died of cholera along with his father while Safdar Jang sacked the Old City (1753),Footnote114 and his great friend Azizullah Beg, lynched by Abdali’s soldiersFootnote115 – Zia-ud-din’s tone is merely one of faded melancholy.

The second is the almost obsessive detail and meticulous care with which Zia-ud-din recorded the biological and pedagogical lineages and multiple complex migrations of hundreds of musicians from Delhi – kalāwants, qawwāls, and gentleman amateurs (nujabā’) – over three decades (see for the information contained in just two related entries).Footnote116 Importantly, his genealogical information, where it overlaps, is supported by other sources of the time, including Edinburgh University MS 585 written in 1788, whose unnamed musician author belonged to the same Delhi kalāwant lineage.Footnote117 Zia-ud-din’s tazkira gives us an unprecedentedly detailed map of the many alternative sites of patronage for Delhi’s exiled musicians across India c. 1760–1790. It also tells us where and often into whose service members of the main lineages of Mughal imperial musicians went. Different lineages of musicians in Mughal Delhi performed different repertoire and possessed slightly different trade secrets: qawwāl linages specialized in khayāl and kalāwants in dhrupad; but Shaikh Moin-ud-din’s khayāl style was as different from Taj Khan’s as the Dagari kalāwant style was from that performed by the Khandari lineage, who were in turn distinctive for singing both dhrupad and khayāl.Footnote118 Knowing exactly which musicians travelled where gives us unparalleled insight into the mechanisms and back-story of major stylistic changes that we know were set in motion by this unprecedented migration.Footnote119

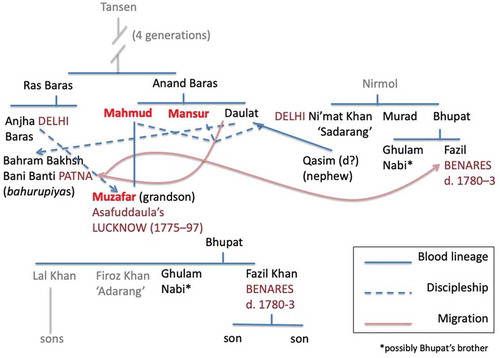

Figure 1. The genealogical and migration information contained in Zia-ud-din’s entries on the lives of kalāwant brothers Mahmud and Mansur Khan, and Mahmud’s grandson Muzaffar

But, thirdly, Zia-ud-din’s attention to detail also helps us to see that by no means all was lost in Delhi’s turmoils, and that the majālis mourned by Mir lived on, elsewhere. One particular passage stands out in this regard: ‘Because of the disturbances in Shahjahanabad,’ wrote Zia-ud-din, Jamal qawwāl ‘came to Lucknow with Khwaja Muhammad Basit and lived there. He performed in the unextinguished majlis which was held in the Khwaja’s residence.’Footnote120 Back in Delhi, Khwaja Muhammad Basit had been famous for the regular poetical, musical, and mystical majlis held in his house. Tabor reminds us that when the Nawab of Awadh Shuja‘-ud-daula (r. 1754–75) invited him to reside in Lucknow, Basit simply transferred his majlis to Awadh and picked up where he had left off, carrying the metaphorical lamp of his gathering unextinguished to its new home.Footnote121 Zia-ud-din himself held a monthly musical majlis for at least two decades in Patna to which he invited all local and visiting musicians, thus recreating the atmosphere of his beloved Delhi in his site of exile.Footnote122 And most of the musicians in his tazkira made similarly successful transitions to new musical lives in Patna, Benares, Lucknow, and elsewhere, as well as keeping the candle burning in the majālis of the exiled Emperor Shah ‘Alam II in Allahabad, and determinedly teaching new generations the old Mughal ways amidst Delhi’s crumbling havelīs.Footnote123

What is critical here is that Zia-ud-din took considerable pains to trace in written form exactly where all of Delhi’s musicians had gone, so that their traditions might not be lost, nor their contributions and lineages forgotten. In gathering all this information together, he was bringing order and control and certainty back into his world, and to that of his community, for whom he was undoubtedly also writing.Footnote124 It is worth noting that the first half of Zia-ud-din’s text – the three chapters on the science of music – is similarly precise and organized.Footnote125 He presented all the information a student needed to know about Hindustani music in a clear and methodical summary, distilling the works of the canonical Mughal theorists while also updating their contents to cover the latest trends. Although we cannot hear the sounds of the music he described, in writing about it so meticulously Zia-ud-din did the best he could to insure all the musical knowledge he had gained over his lifetime against its eternal loss. Similarly, it must have been soothing for him to know that, even if he could not hear his teacher’s great disciple Fazil Khan kalāwant () channelling the lost voices of Muhammad Shah’s court on a daily basis, thanks to his painstaking documentation Zia-ud-din knew where Fazil was living and could travel to nearby Benares to hear him, or even invite Fazil to sing for him in his Patna majlis (until Fazil’s death c. 1780–3).Footnote126 Thus, momentarily, Zia-ud-din might relive his lost Delhi youth, if he just closed his eyes and listened.

But it is in his litanies for those musicians he had been unable to keep track of that what was at stake for Zia-ud-din is most clearly exposed. While marking the death of biographical subjects was common in tazkiras, marking them as ‘missing’ was unusual.Footnote127 And yet it was clearly very important to him to do so. Perhaps this was for the sake of completeness; or to honour them. But it was also because with the disappearance of every one of those musicians the existence of a tiny, unique world of music was thrown into question; even more so when that musician was the last of a distinguished line.Footnote128 His long-term anxiety that the music of his Mughal homeland would survive in its scattered state is palpable here in his frequent repetition of the words ‘it is unclear,’ ‘it is not known’ (ma‘lūm nīst). But it is more poignantly rendered in his prayers for the missing: ‘may God keep them alive … wherever he is, may God Almighty bless him with health and safety … for he was my friend.’Footnote129 Even now, in the winter of his life, Zia-ud-din was still living with uncertainty, with a world he could not entirely tie down, with anxieties that could not be fully resolved. Ultimately the only thing he could do was to put all these things, and all those he loved, in God’s hands.

I noted earlier that as an emotion, anxiety is a response to uncertain threats that generates information gathering, analysis, and sorting behaviours that help individuals evaluate that risk and come up with solutions to mitigate negative outcomes. Zia-ud-din’s book on music, the Everliving Spirits, was written in exile in the face of the existential threat posed by the hangāma-i Abdali and the scattering of the people of Shahjahanabad to the celebrated, communal musical traditions of the Mughal court that were the source of his joy and his selfhood. In Zia-ud-din’s case it was the threatened loss of a powerful stimulus of emotion itself that stimulated anxiety, a very different emotion from the rasas usually written about in music theoretical works. And he did not, or did not have the words to, write about his anxiety directly. In the Hayy al-Arwāh Zia-ud-din therefore gathered together all his knowledge about the science of music, which he had learned painstakingly at the feet of the best musicians of Muhammad Shah’s court, and all the information he could get his hands on about where the scattered court musicians of Delhi were now. He did so firstly in order to mitigate the considerable risk, poured out likewise in Mir’s grief and horror at the desolation of their beloved city, that the music and poetry they both cherished would pass away forever. As Mir put it so hauntingly:

But the act of researching and writing his text, I would suggest, was also Zia-ud-din’s way of alleviating his anxiety when he could not access the soothing medicine of music itself. There are only two passages in the whole of his text where Zia-ud-din wrote about emotions directly. One of them is in his biography of a kalāwant called Qana‘ Khan, who died in Delhi in the mid 1770s. He was given that name because the famous Sufi poet and mystic Shah Gulshan noticed his contented, tranquil (qanā‘at) temperament. In a break from the norm, Zia-ud-din interrupted his narrative to make an aside that, to me, betrays his deepest desire: to be restored to emotional equanimity. ‘He lived in a house in Shahjahanabad in contentment and tranquillity – Good for him. “Oh contentment, make me rich. There is no richness beyond you”.’Footnote131 The other passage is his opening description of how God breathed life into humans at the creation of the world, and will do so again on the Day of Judgement (Qiyāmat). Like his contemporary Hazin’s Tazkirat al-Mu’āsirīn, the Everliving Spirits is in more than one sense a ‘book of the dead’. Its apocalyptic overtones are echoed in other tazkiras of the time that ‘celebrate the lost’.Footnote132

Praise full of music and music full of praise be to the One who provides for the voiceless, and from the workshop of whose blessing … breathed into me a soul (rūh) as music is blown into the reed flute, and the melodies of Israfil the Trumpeter [on the Last Day] were blown into Adam’s body … Praise be to the One who blessed man’s darkened body with luminous breath and voice (dam o sadā-i nūrānī) … I name this collection Hayy al-Arwāh [sg. rūh], the Everliving Spirits, because in the beginning the soul entered the body through the music of the angels, and in the end it will come to life again through the beautiful sound of the Last Trumpet (nafkh).Footnote133

How could Zia-ud-din find contentment when the music of his youth was gone beyond recall, and could no longer be used as the emotional balm his voiceless spirit so desperately needed? The answer is here, in his opening statement. While the sounds of the beloved world of Delhi’s lost musical gatherings might be scattered and silent now; while so many of the ‘everliving spirits’ had been lost to Zia-ud-din in this world, yet there was still hope of restoration in the next. For music is a Divine gift to the living; the everliving spirits of the faithful in the grave are entrusted to God’s care; and music shall be restored to them again with life’s breath, in that great Gathering on the Last Day.

In writing his tazkira on the musical lives of the ‘everliving spirits’, I suggest, Zia-ud-din found another way, in the absence of music itself, to work productively through his anxiety at the disordered state of his world. Through the research and writing process he seems to have found some kind of emotional resolution to his predicament; perhaps, in the end, even contentment.

Acknowledgments

I wish to express my thanks for support and assistance to the John Rylands Library at the University of Manchester, the British Library, and the Edinburgh University Library; Parmis Mozafari and Bruce Wannell for translation help and advice; Margrit Pernau, Shivangani Tandon, Richard David Williams, Elizabeth Gow, Nathan Tabor, Kevin Schwartz, Liam Rees, and especially my fellow travellers in the world of Shah ‘Alam II over the past few years: David Lunn, William Dalrymple, and the late and much missed Bruce Wannell.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Zia-ud-din, Hayy al-Arwāh, f. 60v; my translation. All translations from Mir are S R Faruqi’s (Selected Ghazals) or C M Naim’s (Remembrances), unless specified in the footnote. All other translations are mine; I am grateful to Parmis Mozafari and the late Bruce Wannell for help and advice in translating the Hayy al-Arwāh. I shall use a simplified system of transliteration for Persian and Urdu vocabulary that only marks long vowels (ā ī ū); retroflex consonants (ḍ ḍh ṇ ṛ ṣ ṭ ṭh) and nasalization (ṅ) in words of Indic origin; ain (‘) and hamza (’); and distinguishes kh که from kh خ and gh گه from gh غ. Spelling conforms with Steingass’ Dictionary for Persian and Platts’ Dictionary for Urdu; Steingass is preferred where they conflict. The exceptions are published quotations and bibliographical entries, which conform to their publishers’ preferences; and technical aesthetic/musical terms from Sanskrit, which retain their final ‘a’ (e.g. rāga, rasa).

2. Mir, Selected Ghazals, 204–5; tr. Faruqi, but with “equanimity” for yaksān; Faruqi has “even tenor”.

3. Faqirullah, Rāg Darpan, 152; my translation.

4. Chandra and Levitin, “Neurochemistry of Music,” 179.

5. e.g. for ancient Greece, Cook and Dibben, “Emotion in Culture and History,” 46–7; for ancient India, Rowell, Music and Musical Thought, 15–18; for tenth-century Arab thought, Ikhwan us-Safa’, On Music, 77–81.

6. Cook and Dibben, “Emotion in Culture and History,” 48–50; Thompson and Biddle, Sound, Music, Affect, 18; Juslin and Sloboda, Music and Emotion; Clayton, “Introduction”; Becker, Deep Listeners; and Cochrane, Fantini and Scherer, Emotional Power of Music, ix.

7. Hofman, “Affective Turn in Ethnomusicology”; and Becker, “Exploring the Habitus”.

8. To my knowledge, the first use of the ‘music of Hindustan’ – naghma-i Hindūstān – for this field of knowledge and practice is early seventeenth century; Lahawri, Badshah Namah, vol ii, 5. On my unapologetic use of ‘art’ and ‘elite’ music to refer to the North Indian forms patronized by the Mughals, and on classicization processes in India long before modernity, see Schofield, “Reviving the Golden Age”.

9. Schofield, “Reviving the Golden Age,” esp. 487–90 for a discussion of the substantial secondary literature to 2010 on the colonial-era re-classicization of Indian music; also Walker, India’s Kathak Dance.

10. Schofield, “Musical Culture Under Mughal Patronage,” forthcoming; also Schofield, “‘Words Without Songs’,” 172–7.

11. Rowell, Music and Musical Thought, 15–18; and Clayton, “Introduction.”

12. See Schofield, “Canonical Hindustani Music Treastises”; and Schofield , Music and Musicians.

13. On the category of gentleman-amateur, see fn. 116.

14. The digital version of the Hayy al-Arwāh can be accessed via the John Rylands Library, at <https://luna.manchester.ac.uk/luna/servlet/detail/Manchester~91~1~374998~203213> [last accessed 25/01/21]. On the cultural efflorescence of Muhammad Shah’s court, see Khan, Muraqqa‘; Miner, Sitar and Sarod; and Kaicker, “Unquiet City”. Muhammad Shah’s takhallus is often said to be Rangila, but all eighteenth-century song manuscripts I have examined use Rangile (with final -ye)

15. Memorative communication is Hermansen and Lawrence’s useful definition, “Indo-Persian Tazkiras”; see also Kia, “Contours of Persianate Community,” Chapter 4.

16. cf. Ruh-ullah, Tuhfat al-Naghmāt, 4–13.

17. Zia-ud-din, Hayy al-Arwāh, ff. 3r–38r.

18. ibid., ff. 8v, 9r, 15r, 57v–58r.

19. At the time Shahjahanabad was considered the ‘new city’ (shahr-i nau) as opposed to the ‘old city’ (shahr-i kuhna) of Delhi; Mir, Remembrances, xii–xiii; and Kaicker, “Unquiet City,” 46–73.

20. Zia-ud-din, ff. 38r–62v. For an extended analysis of Mughal-era tazkiras of musicians, see Schofield, Music and Musicians, Chapters 2 and 3. There has been a recent upsurge in scholarly interest in the Persian and Urdu tazkira in India, especially for the eighteenth century. Classic studies include Hermansen and Lawrence, “Indo-Persian Tazkiras”; Faruqi, “Long History Part I”; and Pritchett “Long History Part II”. Important recent scholarship (post-2010) on tazkiras in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century India includes Dudney, “Desire for Meaning”; Mana Kia, “Contours of Persianate Community” and Persianate Selves; Kinra, Writing Self, pp. 258–95; Pelló, “Persian as a Passe-Partout” and “Persian Poets on the Streets”; Schwartz, “Transregional Persianate Library”; Sharma, “Reading the Acts”; and Tabor, “Market for Speech”.

21. Rasikh, Risāla, cf. Zia-ud-din, Hayy al-Arwāh; and Schofield, Music and Musicians, Chapter 3.

22. e.g. Zia-ud-din, Hayy al Arwāh, ff. 46r, 48r, 49v.

23. Najmabadi, Professing Selves, 276–7, quoted in Kia, “Indian Friends”, 398; and Schofield, “Musical Culture,” forthcoming.

24. Schofield, Music and Musicians, Chapter 3.

25. Kia, “Contours of Persianate Community,” 257–9; see also Kia, “Indian Friends,” 398.

26. Sabri, “Mir Taqi Mir’s Zikr-i Mir,” for a discussion of the need to view Mir’s text as a work of ādāb, in which he presents idealized emotions and selfhood, rather than viewing it as factually autobiographical.

27. Pernau, “Mapping Emotions, Constructing Feelings,” 634–37. In contrast, Kinra argues that there are many more ego documents available in the Indo-Persianate archive that we have perhaps overlooked, especially in the widely practised realm of inshā’ or ‘letters’; Writing Self, Writing Empire, 8–9.

28. Kia, “Contours of Persianate Community,” 263.

29. Kia, “Contours of Persianate Community ,” 262–4; Schwartz, “Transregional Personal Library”; I am grateful to Kevin Schwartz for sharing unpublished work with me. On tazkiras as mediators of loss, see Kia on Hazin, “Contours of Persianate Community ,” 264–70. Also Schofield, Music and Musicians, Chapter 3.

30. Kurth, Anxious Mind. For a full summary of Kurth’s compelling argument, see the outstanding introduction to his book, especially 1–2, 7, 15, 33 from which I have taken the direct quotations in this paragraph.

31. See e.g. Kenny, Psychology of Music Performance Anxiety. Nearly all the remaining literature on music and anxiety concerns listening to music as a therapy to alleviate anxiety; e.g. Chanda and Levitin, “Neurochemistry of Music”; Nilsson, “Anxiety- and Pain-Reducing Effects of Music”; and Thoma et al, “Effect of Music.”

32. See also Chandra and Levitin, “Neurochemistry of Music,” 183–6.

33. Mir, Nikāt al-Shu‘arā, 130.

34. Mir’s autobiography and a large selection of his Urdu ghazals and masnawīs have recently been published in new editions and translations by the Murty Classical Library; Mir, Remembrances, and Mir, Selected Ghazals. Sabri’s recent article “Zikr-i Mīr” shines much needed critical light on the ‘constructed’ elements of Mir’s autobiography. That being noted, the parts of his memoir covering the sacking of Delhi and his departure in 1760–61 adhere closely to the chronology of known events.

35. Abul Fazl, Akbarnámah, vol. ii, 136.

36. For a full discussion of the theoretical basis for the association of the rāgas with affective and supernatural power in Persianate Deccani and Mughal writings, see Schofield, “Music, Art, and Power,” and “Musical Culture”. For the use of ta'sīr and asar to denote the affective powers/supernatural and emotional effects of the rāgas c.1658–1858 see e.g. Hasan, Miftāh al-Sarūd, ff. 8r–v; Zamir, Tarjuma-i Kitāb-i Pārijātak [or Pārījātak], f. 1v; Faqirullah, Rāg Darpan, 78–81; and K I Khan, Ma‘dan al-Mūsīqī, 106–19.

37. Pollock, Rasa Reader, 5–9, 19–21; and Schofield, “Reviving the Golden Age,” 491–502. The written theoretical tradition on music in Sanskrit begins with the Nāṭyashāstra, composed in the first few centuries C.E., and the Persian tradition of writing systematically on Indian music dates at least as early as Amir Khusrau (1253–1325).

38. Pollock, Rasa Reader, 50, 8, 21–2, 327–8; these are Pollock’s translations of these terms.

39. Zauq is a multilayered word that is frequently used in Sufi contexts to refer to taste in a spiritual sense; see below, and Behl, Love’s Subtle Magic, 22. However, in the realm of early modern aesthetic discourse on the Indian arts in Persian, including the canonical seventeenth-century Mughal music treatises, zauq (or lazzat) was used to translate the aesthetic term rasa. It is this aesthetic usage to which I am largely referring here. For a longer discussion see Schofield, “Learning to Taste the Emotions”, esp. 416–17; for the Mughal translation of rasa as zauq (in this case zauq o maza) see e.g. Khan, Tuhfat al-Hind, vol. i, 71; and for its use as aesthetic taste/pleasure, e.g. Faqirullah, Rāg Darpan, ‘some of my friends whose entire pleasure (zauq-i tamām) is in music’, 222.

40. See Leante, “Lotus and the King,” for a seminal discussion of contemporary musicians’ and listeners’ impressionistic and multifaceted emotional responses to Rag Shri; critically, she notes that ‘only an extremely limited number of musicians among those interviewed mentioned the concept of rasa,’ 204 fn. 6.

41. Zia-ud-din, Hayy al-Arwāh, f. 23r.

42. Schofield, “Learning to Taste the Emotions,” 413–19; and Widdess, Ragas of Early Indian Music, 39–48.

43. Faqirullah, Rāg Darpan, 160–71; Khan, Tuhfat al-Hind, vol. ii, 338–43; Schofield, “Musical Culture,” forthcoming. I heard this exact sentiment concerning bībhatsa rasa expressed on the concert stage by the late surbahār maestro Ustad Imrat Khan.

44. Schofield, “Music, Art, and Power”; Ebeling, Ragamala Painting; Miner, “Raga in the Early Sixteenth Century”; and on rāgamālā poetry, Williams, “Reflecting in the Vernacular.”

45. e.g. Orsini, “Clouds, Cuckoos, and an Empty Bed,” 125–9, for Uzlat’s Urdu poetical rāga icon of Rag Megh.

46. Powers, “Illustrated Inventories,” 482.

47. Zia-ud-din, Hayy al-Arwāh, ff. 57v–58r; cf. Khan, Tuhfat al-Hind, ‘singār ras ya‘nī ‘āshiqī o ma‘shūqī o bayān-i ahwāl-i ‘āshiq o ma‘shūq,’ vol. i, 5.

48. Pollock, Rasa Reader, xv–xvi, 53–5 and glossary, for a discussion of the bhāvas.

49. Schofield, “Learning to Taste the Emotions,” 415–6; and Faqirullah, Rāg Darpan, 94.

50. Shackle, “Persian Poetry,” on the concept of the Suficate.

51. Khan, Tuhfat al-Hind, vol. i, 71; de Bruijn, Persian Sufi Poetry, 71–2.

52. e.g. Pauwels, Mobilizing Krishna’s World, 49–59.

53. Behl, Love’s Subtle Magic, 59–108, 286–384.

54. Leante, “Lotus and the King”; Schofield, “Learning to Taste the Emotions,” on the notion of ‘affinity’.

55. On the Greco-Islamicate mental faculties of irascibility (quwwat-i ghazabī, anger) and concupiscence (quwwat-i shahwī, desire) also being engendered by fast speeds in Hindustani music, see Anon, Untitled Treatise on Tāla, ff. 41r–v, 58r–v; also Schofield, “Musical Culture,” forthcoming.

56. See Schofield, “Music, Art, and Power”; and Schofield, “Musical Culture,” forthcoming, for extensive discussion of Greco-Islamic, Persian, and Suficate emotional language used to describe the rāgas’ effects and affinities with the rasas. It is beyond the scope of this paper to go into any further depth on the Greco-Islamic and Suficate reinterpretations of Indic ideas about musical effects.

57. ‘Abd-ul-karim, Jawāhir al-Mūsīqāt, f. 67v; Schofield, “Learning to Taste the Emotions,” 418–9.

58. Schofield, “Music, Art, and Power,” and Schofield, “Musical Culture,” forthcoming.

59. Faqirullah, Rāg Darpan, 152.

60. Schofield, “Music, Art, and Power,” 69–72.

61. Schofield, “Music, Art, and Power,” for the technical details; “Musical Culture,” forthcoming, for the full explanation.

62. Schofield and Lunn, “Desire, Devotion and the Music of the Monsoon,” 242–7.

63. Brown [Schofield], “If Music Be the Food of Love.” In modern times, gatherings for poetry and music became separate institutions generally referred to respectively as the mahfil and the mushā‘ira (also mahfil-i mushā‘ira). Assemblies for the recitation or singing of religious poetry are still usually called the majlis (e.g. the majlis-i samā‘); see Mahmudabad, Poetry of Belonging, 33–4, 44–8, on the emergence of mushā‘ira as the term for an exclusively poetical gathering.

64. Gentry notes that the term ‘identity’ was an innovation of 1950s social scientists and marks a conceptual ‘break with earlier notions of selfhood’; What Will I Be, 5. I thus use selfhood or self-fashioning instead of ‘identity’ throughout this paper. There is an almost bottomless literature on music and identity and music and memory in several subdisciplines of music studies, especially in ethnomusicology and music psychology.

65. In classical Indian aesthetic theory, anxiety is a transitory bhāva ‘observed to accompany any number of [rasas]’; Pollock, Rasa Reader, 201.

66. Petievich, “Poetry of the Declining Mughals,” 103; my emphasis.

67. Zia-ud-din, Hayy al-Arwāh, f. 1v. This figure may have been the famous co-author of the great tazkira of Mughal noblemen, the Ma’āsir ul-Umarā’, completed in 1780; Khan and Hayy, Maāthir-ul-Umarā, vol. i, v–vi. On the other hand, the co-author of the Ma’āsir ul-Umarā’ lived in the Deccan all his life and died in 1782; ibid, vol i, 32 fn. 1; whereas Zia-ud-din notes that his dedicatee was alive at the time of writing and had at one point lived in ‘eastern lands’, i.e. Awadh, Bihar, or Bengal; Hayy al-Arwāh, f. 57r.

68. Zia-ud-din, Hayy al-Arwāh, ff. 1r, 56v, 57v. On Nadir Shah’s invasion, see Dalrymple and Anand, Koh-i-noor, 63–92; and Kaicker, King and the People, 18–53. Zia-ud-din must have been younger than Mir (b. 1723), who called him ‘fresh-faced’, but old enough to remember Nadir Shah first hand.

69. See note 33 above.

70. Zia-ud-din, Hayy al-Arwāh, ff. 44r–45v; Schofield, Music and Musicians, Chapter 3. For an extensive exploration of the overlapping circles of poetry, music, and Sufism in eighteenth-century Delhi, see Tabor, “Market for Speech”.

71. Not to be confused with Afghan warlord and conqueror of Delhi Ahmad Shah Abdali Durrani. To avoid confusion I refer to the latter throughout this paper as Abdali.

72. A high ranking Awadhi nobleman, Nawab Iftikhar-ud-daula Amir-ul-mulk Mirza ‘Ali Khan Bahadur Dilawar Jang was a correspondent of Swiss adventurer and famous Lucknow resident Antoine Polier. By 1775, Iftikhar-ud-daula was based at the Lucknow court of Nawab Asaf-ud-daula of Awadh; Polier, European Experience of the Mughal Orient, 230, 267.

73. Zia-ud-din uses the phrase ‘Faizabad Bengal’ to differentiate it from Faizabad in Awadh, the seat of the Nawab of Awadh in the 1750s. This may be Faizabad in what is now Bihar, east of Patna, but the exact location is unclear.

74. Malua, “Between Two Empires,” 198.

75. Autobiographical details above: Zia-ud-din, Hayy al-Arwāh, ff. 52v, 45v, 47r-v, 46r, 49v, 62v.

76. Sprenger, Catalogue of the Arabic, Persian, and Hindustany Manuscripts, vol i, 182, 265. Nawab Zain-ud-din is perhaps more famous as the father of Siraj-ud-daula, the last independent Nawab Nazim of Bengal (d. 1757).