ABSTRACT

Digital campaigning has become an engineered process whereby political parties target electorates almost precisely. I explore the digital campaigning strategies of the three main political parties in Karnataka – the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the Indian National Congress (INC) and Janata Dal Secular (JDS) – during the 2019 national election based on interviews with social media campaign teams in Bengaluru. Along with the parties’ traditional ground campaigns with massive rallies, booths on the streets, canvassing, and posters or billboards, social media was an integral part of each party’s campaign and an indispensable means of reaching out to the electorate and mobilizing voters. The cells focused on posting daily or multiple times a day on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and WhatsApp. Different divisions were responsible for rebuttals as well as party advertising on social media platforms. The BJP and INC ran professional digital campaigning operations, with a more mature operation by the BJP. The JDS was still in a nascent stage of digital campaigning.

While political leaders compete to mobilize the electorate through ground campaign activities, including huge rallies, party booths on the streets and door-to-door campaigning, their party IT cell workers are quietly sitting in war rooms reaching out to millions through social media. India, the largest democracy in the world, witnessed vigorous social media campaigning in the 2019 Lok Sabha election. Political parties in the US, UK and Europe have taken full advantage of the fast-paced development of Internet Communication Technologies (ICTs) and social media in the current ‘fourth era of political communication’.Footnote1 India’s political parties used digital means to reach out to the electorate as early as the 2004 Lok Sabha election, but more effectively after the 2014 national election with the growth in access.Footnote2

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) is said to be a forerunner in tactically using technology for political communication, from television to social media. For instance, when televisions were becoming a popular household good, the BJP party purportedly, through the medium of television, culturally mobilized the electorate with entertainment programming.Footnote3 When the internet and social media emerged in India, the BJP was the first to make use of the opportunity during the 2004 national election, though ICTs were dubbed elite and urban.Footnote4 However, a decade later, during the 2014 Lok Sabha election, studies argued that some of the credit for the BJP’s victory, which included an absolute majority, was partly due to digital campaigning that was more elite and urban than not. 2014 is described as the beginning of successful digital campaigning in India.Footnote5 Coupled with social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook, and messaging apps like WhatsApp, digital campaigning proved to be an effective medium to mobilize voters and win elections. For instance, in the run-up to the 2014 election the BJP announced about 160 constituencies out of 543 were suitable for implementing a digital campaign strategy, and in fact the BJP won these ‘digital constituencies’.Footnote6 As a result, it was inevitable that other political parties would join the digital campaigning bandwagon and create an infrastructure for digital campaigning in subsequent elections at the state level and in the 2019 Lok Sabha election.

Today, political campaigning has become an engineered process augmented by ICTs, which some scholars describe as ‘computational propaganda’.Footnote7 During the 2014 Lok Sabha election campaign, digital connectivity and the internet were highlighted as one of the major policy preferences by both the BJP and the Indian National Congress (INC).Footnote8 The BJP, after forming the government in 2014, implemented various policies around connecting India digitally, and also continued to expand some of the existing digital policies, such as Aadhaar, the biometric ID card.Footnote9 Since 2014, digital connectivity has surged, along with the growing availability of low-cost smartphones, feature phones and data services – making the 2019 national election arguably India’s first social media election. shows the expenditures of the BJP and the INC on online advertisements – Facebook and Google – during the 2019 election, indicating the importance of digital campaigning.

Table 1. Expenditures on Online Political ADS by the BJP and the INC.

Digital technologies, social media, and low-cost data have enabled the electorate to engage with the government more directly than ever before. The ‘Mobile Technology and its Social Impact Survey 2018’ conducted by Pew Research Center shows that in India about 32% of adults own a smartphone, 38% use the internet, and 81% obtained information and news using their mobile phones.Footnote11 WhatsApp and Facebook are commonly used messaging apps, by 29% and 24% respectively, according to Pew.Footnote12 However, the 2018 survey findings may underestimate the reach of social media given that the official report from the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India (TRAI) shows Karnataka as having a teledensity of 111.10 on 31 January 2019, a number derived from the telephone subscriber data provided by the access service providers and the population projections published by the Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner of India. Given this scenario, there is an attempt by the political parties to strategically set narratives through social media, creating ‘echo chambers’ and ‘filter bubbles.’Footnote13

This study explores the importance of understanding the supply side of digital campaigning, with a focus on party strategy, campaign content, and misinformation by three major political parties in Karnataka – the BJP, the INC, and the Janata Dal Secular (JDS) – during the 2019 Lok Sabha election. displays the vote share and number of seats won by the three major parties in Karnataka in the 2019 Lok Sabha election, for which voter turnout was about 68.6%. While it appears to be a clean sweep for the BJP, the situation at the state level is far more contentious and is discussed further below in the section on political parties and development of the party system. Evidence from this study shows how digital campaigning and social media have become indispensable for the political parties to reach out to and mobilize potential voters in Karnataka.

Table 2. Party vote shares and seats in the recent Lok Sabha election in Karnataka.

Political and geographic history of Karnataka

Karnataka – the region historically known as Kannada, Kannadu, Kannadar, Karnate, Kuntala, ‘Karnata Desha’ in Mahabharata, and Mysore state from post-independence until 1973 – is a South Indian state located in peninsular India.Footnote14 It has been over 60 years since states in India transformed from fragmented princely states into linguistically homogeneous political entities comprising diverse ethnolinguistic cultures. Karnataka was formed via a Kannada-speaking population, which was spread across the erstwhile princely states of Mysore, Hyderabad as well as British India. Kannada is a classical language of India with a rich literary heritage and a roughly 2500-year history of contributing to socio-cultural and political developments in Karnataka and India; it is currently spoken by 56 million people.Footnote15 Karnataka is the sixth largest state in India geographically speaking, and the largest state in South India, with an area about 191,791 square kilometres, evergreen western ghats, and coastline and plateaus comprising rich flora and fauna. Bengaluru (previously Bangalore), the capital city of Karnataka, which is known for its science and technological institutes and as the Silicon Valley of India, is also a start-up hub and the defence hub of the country.

Political developments in the early ages had constituted multiple geographical and cultural identities for Kannada kingdoms. They were not confined to the present-day Karnataka, but spread across different parts of modern India, partially or entirely and beyond.Footnote16 Prominently we see the Shatavahana, Kadamba, Ganga, Chalukya, Rashtrakuta, Hoysala and Vijayanagara empires’ contributions to the art, architecture and politics of the Indian sub-continent. The town of Aihole in Karnataka, which flourished during the Chalukya emprire, is referred to as the ‘Cradle of Indian temple architecture’, and these models can still be seen in the South and North Indian temple architecture.Footnote17

During the colonial period, a large portion of Karnataka was under the Mysore rulers, who are hailed and worshipped even to this day for their welfare policies; other portions were under the Nizam, Coorg and British rule.Footnote18 In the post-independence period, political evolution in Karnataka is considered to be ‘broad-minded and nationalistic’ in its approach to centre-state and inter-state relations, unlike the neighbouring states, which have been characterized as confrontationist.Footnote19 In other words, Karnataka’s polity has upheld ‘federal supremacy’.Footnote20 Although Karnataka favoured co-operative federalism, there has been a reaction by the state when confronted by challenges – for example, the recent water sharing issue and the imposition of language policy.

On elections and vote choice, ethnic identities and favouritism have been a priori factors determining whether leaders are elected into office in Karnataka; however, religion has not been a deciding factor, unlike in some of the states in India. The population of Karnataka comprises 84% Hindus, 12.9% Muslims, and 1.9% Christians; Jainism and Buddhism constitute 0.72% and 0.16% respectively.Footnote21 In fact, in the late 1970s and early 1980s religion-based parties like the Muslim League attempted to make inroads in Karnataka but were not very successful. With this historical background, the post-colonial development of politics in Karnataka is discussed below in greater detail.

Political parties and the development of the party system

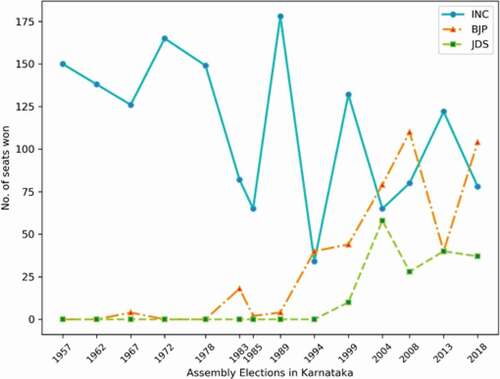

Rooted in the freedom movement, the Congress party emerged at the epicentre of the Indian polity, becoming the dominant political party in India at the time of independence. The national movements in Karnataka were significantly influenced by Gandhi and the Congress party; as a result, post-independence, the Congress party remained the popular choice for the electorates. After the reorganization of states in 1956, although Congress was still the largest party in Karnataka, there were other parties like Bharatiya Jana Sangh (which later became the Bharatiya Janata Party) and the Praja Socialist Party, among others, that contested the elections. shows the development of the three main political parties in Karnataka to date – the INC, the BJP and the JDS.

Figure 1. Development of the three Main Political parties in Karnataka.

Politics in Karnataka reflected national politics; any change in the national arena had a subsequent effect on state politics. The imposition of the National Emergency by the then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had a huge impact on the Congress party, which lost across many states; however, in Karnataka the INC performed well. In fact, Indira Gandhi contested and won the Chikkamagaluru Lok Sabha constituency in the 1978 election, and in the state election the INC won 149 seats that same year. The Emergency united the opposition and led to the formation of the Janata Party at both the national and state levels. During this time, South Indian states like Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu had film stars as their leaders, but in Karnataka the iconic film star Rajkumar stayed away from politics, though he was urged by the opposition parties to contest Indira Gandhi in Chikkamagaluru.Footnote22 The Janata Party won 59 seats in Karnataka, and was on the verge of becoming a strong opposition force to the INC.

Meanwhile, the Jana Sangh faction broke out of the Janata party and established the BJP in 1980, contesting both the national and state elections. During the 1983Footnote23 state election, the BJP won 18 seats while the Janata Party secured 95 seats and for the first time a non-INC government was formed in Karnataka with the support of the BJP and other small parties under Ramakrishna Hegde.Footnote24 The Janata Party secured an absolute majority in the 1985 election by winning 139 seats and INC seats were further reduced to 65 from 82.

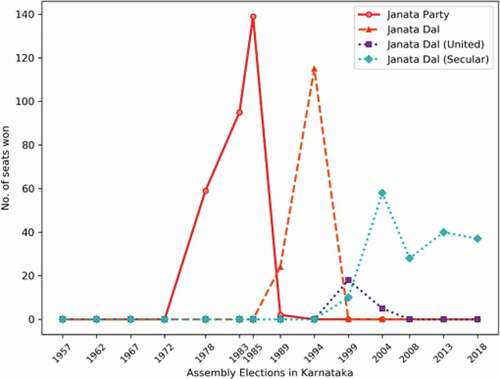

By the 1989 election, the Janata Party had split into two parties – the JNP (JP) and Janata Dal – and lost the majority of its seats; it was reduced to just 26 seats while the INC emerged victorious, winning an unprecedented 178 seats. depicts the rise and fall of the Janata party in Karnataka. After the 1983 election, the BJP did not perform well in the 1985 and the 1989 elections and won only two and four seats respectively. Interestingly, in the run-up to the 1989 election, many regional parties emerged representing the cause of the Kannada language, including one representing farmers, among others.Footnote25 Karnataka Rajya Ryota Sangha (KRS), the farmers’ party, even won two seats in that election.

Figure 2. The rise, fall and Disintegration of the Janata party.

In the 1994 Assembly election, Janata Dal became prominent, forming the government with 115 seats, while the INC was reduced to 34 seats and the BJP secured 40 seats, up from four. The dominance of Janata Dal later led H. D. Deve Gowda to become Prime Minister of India.Footnote26 The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) opened its account in Karnataka by winning one seat in North Karnataka. By the time of the 1999 election, the Janata Dal had split into two segments – Janata Dal United (JDU) and Janata Dal Secular (JDS). As a result, neither the JDU nor the JDS had a big win. The INC won the majority seats and BJP won 44 seats.

The 2004 election was interesting as none of the major parties had a clear majority. The JDS won 58 seats, the INC won 65, and the BJP won 79; however, the JDS supported the INC and a coalition government was formed under the leadership of the INC. In 2006, the JDS withdrew its support from the INC and instead supported the BJP to form the 20–20 coalition government. As per this arrangement, for 20 months the government would be led by the JDS and for the following 20 months it would be led by the BJP.Footnote27 However, once the JDS completed its 20-month leadership, the party deserted the BJP and withdrew its support, leading to an election in 2008.

It is noteworthy that Left parties – the Communist Party of India (CPI) and the Communist Party Marxist (CPM) – had very little or no influence in Karnataka, unlike in West Bengal or neighbouring Kerala. After the reorganization of the states, these parties won no more than three seats until the 1985 election, and were left with one seat in the 1994 and 2004 elections respectively. They haven’t won a single seat since the 2008 election in the state.

For the first time in South India, the BJP formed the government in 2008, under the leadership of B. S. Yediyurappa. This election sidelined the JDS party and the BJP became a dominant party in Karnataka. Although there were many changes in the BJP’s leadership, it completed a five-year tenure. Due to internal turmoil, the BJP underperformed in the 2013 assembly election and the INC won the majority of seats and formed the government. It was against this backdrop of longstanding electoral volatility that the BJP projected Narendra Modi as the candidate for prime minister during the 2014 Lok Sabha election and secured 17 Lok Sabha constituencies from Karnataka.

In the backdrop of what was described as the ‘Modi wave’ around the country in 2014, Karnataka held an Assembly election in 2018, and although the BJP emerged as the single largest party with 104 seats, it fell short of the majority (). Interestingly, the INC supported the JDS and formed an unstable government until 23 July 2019. The BJP formed the government on 25 July, as the house strength fell short by 17 members – 13 members from the INC and three from the JDS submitted resignations, another member withdrew his support from the coalition government,Footnote28 and thus the BJP was able to pass the ‘floor test.’Footnote29 In the 2019 national election, 25 BJP MPs won the Lok Sabha election in the state of Karnataka, reducing the INC and the JDS to one constituency each (). Studies have attributed the changing nature of campaigning and the use of social media and digital reach as reasons for the election victory.Footnote30

Table 3. Party vote shares and seats in the recent Assembly elections.

The 2019 national election in Karnataka was highly contested, with the image of Prime Minister Modi defending an incumbent government. However, one cannot rule out the popularity of the Karnataka BJP leaders in mobilizing the electorate. The BJP believes it was a combination of leader popularity supported by the digital media campaign, along with the party’s dynamic ground campaign of volunteers and party workers engaging citizens on the streets and in their homes, that brought the BJP victory in Karnataka with the winning of 25 of 28 Lok Sabha seats.

Evolution of the Kannada media system

For many decades, television and radio broadcasting in India was state-controlled. Although radio was a common household good, television became a luxury good in the 1980s. During this period, the only broadcasting entities were Doordarshan and Akashvani – for television and radio respectively – under the purview of the Government of India. Notably, the history of communication media in Karnataka begins as early as 1843 with the Kannada newspaper called Mangalooru Samachara.Footnote32 The print media houses set up Kannada and English newspapers (e.g. Prajavani and Deccan Herald) soon after independence. Over the years Karnataka witnessed an increasing number of Kannada and English newspapers and magazines.

After the economic reforms in 1991, there was a paradigm shift in the Indian television media as the private media players set up private television channels.Footnote33 Karnataka is referred to as a forerunner in electronic mass communication, and Bengaluru is termed the ‘hotspot of fervid media activity’ in India, with Mysore having had the first private radio station as early as 1935.Footnote34

The state-run DD Chandana, dedicated to Kannada-language TV programmes, was launched in 1991. Later, the Sun TV Network started the first private Kannada-language television channel called Udaya TV, which was launched in 1994. After 2005, there was a surge in television channels in Karnataka across different categories, including news, entertainment, music, comedy, spirituality and lifestyle channels. With digitization and better communication systems in place, the media industry changed, following global standards in terms of transmission, quality, etc. There was a transformation from local cable TV operators to Direct to Home (DTH) services provided by large businesses houses. The emergence of digital and social media organically changed the activity of traditional media, which also quickly developed a presence online, sharing content on their YouTube channels, Twitter and Facebook pages. In addition, there has been the emergence of born digital or online-only news outlets in recent years. The author identified that in total there are about 14 newspapers, five magazines, six radio stations, and 11 TV news channels in Kannada, which share their content on social media in addition to print and broadcast respectively.

According to a report by TRAI, Karnataka had about 68.24 million wireless data subscribers as of March 2019, which also indicates the number of people with smartphones in Karnataka.Footnote35 There was a net addition of 8.53 million new subscribers in 2018 compared to 2017, but that was reduced by 0.55 compared to December 2018.Footnote36 In terms of wireless data usage, there was a 117.9% growth in 2018. All of these figures indicate that year-on-year growth is significant, with a surge in the number of internet users. As a result, it has become easy for marketing companies, media houses and political parties alike to target an individual user on the internet.

There is a growing trend towards the creation of digital content in the Kannada language, which includes activism and consumer awareness. There is an increased amount of Kannada content on Amazon Prime, on sports channels like Star Sports Kannada, and on online-only news portals such as OneIndia, Dailyhunt, news kannada, and others. There were at least 30–40 online-only news portals in Kannada,Footnote37 and one fact-checking portal as of 2019 – Digiteye India, which corrects misinformation through investigation and publishes facts.Footnote38

Alongside the mainstream media, social media provides a free way for individual users to create content and share their ideas. The social media presence of much traditional media reflects the importance of social media and digital platforms. Social media has also created an opportunity for political parties to communicate with the electorate directly. Parties have set up social media/IT cells to promote digital presence, information dissemination, party/leader social media accounts, etc.

Media and campaign communication

In India, research on political communication is fundamentally about campaign communication, where the parties reach out to the electorate during the elections.Footnote39 Studies on elections in India discuss vote share at the aggregate level, voter turnout, demographic influences, policy issues, economics, health, corruption, specific elections, campaign strategies, media effects, etc.Footnote40 Studies on campaigning show campaign strategies began to shift focus towards social media especially after the 2014 election.Footnote41 Traditionally, campaign communication involved rallies and campaign speeches, policies and manifestos, door-to-door campaigning, party booths, posters, and billboards on the streets, which were considered official party activities. Today, however, a post on Twitter or Facebook by a leader or a party is also considered official political communication.Footnote42 This change has significantly increased the digital presence of political parties and leaders in India; for example, this author found that about 70% of MPs during the 16th Lok Sabha had a Twitter account as of April 2019, before the dissolution of the house. Time and again, research across technological development and political communication shows that political parties adapt to change.Footnote43 Jay Blumler notes that, although technological changes could cause temporary ‘unsettlement’ in political communication, they would enable political actors to rewire their communication with the larger ‘political audience.’Footnote44

Studies show how voters in India behave in terms of attitude and expression of sentiment and as vote mobilizers on and through social media. Chhibber and Ostermann argue that media exposure had an impact on vote mobilizers and in turn benefitted the BJP during the 2014 elections, and Verma and Sardesai also argue that reported media exposure has an effect on voting behaviour.Footnote45 The 2019 election surveys by Semetko, Kumar, and Saikia, based on the evidence from Delhi and Bengaluru, also show that attention to campaign information had a stronger effect on vote choice compared to media exposure.Footnote46 This study explores the campaigner’s perspective in terms of digital campaigning and its content.

Data and methodology

In order to understand the digital campaign strategy of the political parties, the author conducted semi-structured interviews with social media cell convenors, digital campaigners and spokespersons of the three major political parties in Karnataka, which includes two national parties, the BJP and the INC, and one regional party, the JDS. The interviews were conducted in Bengaluru city after Karnataka voted (18 April – 23 April 2019), during the seven-phase election period of the Lok Sabha election (11 April – 19 May 2019). The interviewees were introduced through personal contacts and were chosen without any pre-conditions. The interviews were focused on two broad themes: party strategies towards digital campaigning and content of the campaign, with a special focus on misinformation. In addition to interviewing these individuals on the overall party strategy, the author also interviewed campaigners for the BJP’s candidate in Bengaluru South constituency. Hence, this research can distinguish between party-level and individual-level campaign strategies.

Demography, training, and skill set of the campaigners

The 2019 Lok Sabha election was a social media election, as many parties actively used various social media platforms to campaign, as compared to the 2014 election. The INC actively started using social media for reaching out to people and campaigning in 2017. The social media cell of the INC responsible for Karnataka was interviewed in order to gain understanding of its campaign strategies. Of the five people interviewed, there was one female, and the average age was around 33 years. All were college graduates, and three people worked as full-time employees, while the remaining two worked part-time for the social media cell. The career field of each interviewee varied, from video/photo editing to journalism and law. Their role was to create content and disseminate the information through a social media platform, including management of the official INC Twitter and Facebook accounts. They reported being recruited either through interview, reference, or by virtue of party activism or volunteerism. Although there was no formal training or workshop before the social media campaigning began, they met every day with the team and the social media head of the INC in Karnataka.

The BJP is known for its social media outreach since the 2014 election, and during the 2019 election the party again effectively used social media for campaigning. Six people were interviewed who were part of the social media team campaigning in Karnataka, including at the national level. All six participants were male, with an average age of 32 years. Most were post-graduates – trained engineers holding master’s degrees in business administration and volunteers (karyakarthas) for the BJP during elections – except one, who worked full-time. They had worked in the IT industry and included entrepreneurs. They had had various training sessions from the party leaders or volunteers, which included workshops on politics, do’s and don’ts of social media campaigning, etc. They were skilled in managing volunteers, data analysis, creating content in Kannada language, and video editing. The participants included a convenor and co-convenor of BJP social media in Karnataka, a political analyst and a person in charge of social media for a Member of Parliament (MP); two others were in charge of campaigning (social media and traditional) for the Bengaluru South MP candidate, and another was a video editor. The interviewees were responsible for strategy on the campaign, creating content, and handling the official social media accounts of the party and politicians, along with training volunteers across the state.

The JDS party considers itself a regional party; its social media presence has increased since the contentious 2018 assembly election in Karnataka. The author interviewed one participant from the JDS party, who works as a president for the JDS IT wing. The participant was a male IT professional and a party activist of about 39 years of age. He said that he had no formal training from the JDS; however, he also said that an IT professional was the profile the party had wanted in hiring for the campaign.

Campaign strategies of the INC, the BJP and the JDS

Indian National Congress (INC)

Speaking about campaign strategies, the participants said that full-fledged social media campaigning started after the Election Commission of India announced the election dates on 10 March 2019, but that they were preparing at the district level from December 2018. The team consisted of about 35–40 full-time and part-time employees or volunteers in the run-up to the election, but after the election the team was reduced to four or five full-time employees. All social media campaigning was managed in-house and there was no outsourcing of social media campaigning, unlike during the Karnataka state assembly election in 2018 when the campaigning was partially outsourced. The interviewees did not disclose further information on third-party campaigners. They said that compared to traditional campaigning, social media has wide reach with low expenses and hence the INC realized the need to set up its own social media cell. They said that the behaviour of the voters was analysed based on the engagement with a post – for example, likes, comments, shares, retweets, etc.

The INC actively campaigned on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and WhatsApp. The focus was on Facebook, Twitter and WhatsApp during this particular election. The design and content varied from platform to platform to suit the different audiences. The campaigning was conducted in both the English and Kannada languages. The variation in content was also based on the timing; for example, one of the participants said that the campaigning would be in propaganda mode, or negative campaigning. Then, a few days before the voting, the focus would be on promoting the accomplishments of the INC government in Karnataka. The focus was on covering the achievements of the INC party, with an emphasis on the party’s ideology and the charisma of the Karnataka and the national leaders and candidates, while highlighting the failures of the BJP. Sometimes the content would change based on the region and the target audience. The interviewees reported that the content is usually decided by the head of the social media cell and other party leaders, based on the day’s or week’s political developments, and after getting an approval the content is posted on social media platforms. In order to address the comments or criticisms about the INC party and its leaders, there was a separate team for managing rebuttals.

When the author asked about the identification of potential supporters on social media, one of the participants said that such voters were identified based on the likelihood of engagement with the post. However, it was also said that they did not analyse the behavioural patterns of users on social media to strategise and mobilize potential voters. Interestingly, they had many offline programmes which augmented social media campaigning; for example, a programme called Janadhwani (Voice of People) was conducted at the block level to mobilize youth voters and ask them to share the party’s content on their social media. This programme was mostly organized and run by local party workers and volunteers.

On measuring the reach of a post, they said there was another team to monitor the number of likes, comments, shares, discussion of the topic (positive or negative), in addition to the user statistics they obtained from Facebook page management. Facebook ads were also published and used to measure the reach of a post.

Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)

Many researchers credit the BJP for most successfully mobilizing voters using social media.Footnote47 The strategists this author interviewed reported that there was a communication cell in charge of media campaigning until 2007, a post that the IT cells at national and state levels constituted. Later, during the 2014 election, a separate social media cell was established. In contrast to the INC, for the BJP in Karnataka, social media campaigning is completely managed by volunteers and most of them have an IT background. The BJP’s social media presence can be seen on most of the popular platforms, including Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp, Instagram, YouTube, etc. Social media campaigning was managed in-house, without outsourcing to third parties. Within the overarching goal of winning the election, their goal was to reach the maximum number of people in less time with low-cost information. One of them even mentioned the Orkut platform, which Google shut down in 2014 and which was long used for campaigning, as an indicator of the BJP’s early use of social media for campaigning. It was said that, during 2019 the election, WhatsApp, Facebook and Twitter were frequently used to cater to different audiences. For example, Twitter was used to mobilize educated urban voters, whereas Facebook and WhatsApp were used for micro-targeting. Sometimes, third-party pages or websites were also used for campaigning. The interviewees said that campaigning on these third-party sites was mainly focused on PM Narendra Modi and for defending the incumbent government, along with national and regional issues ranging from the economy to rural development, to national security. One of the respondents who worked in the office of a sitting MP said that the social media cell would contact them for strategising and content. Sometimes, in order to defend the party, they had to resort to critical engagement on social media.

The BJP’s emphasis on social media campaigning could be seen in the creation of Twitter handles for all the MP candidates and sitting MPs. The activities of the social media cell included conducting research, creating content and disseminating content. One of the participants who creates video content said that content varied across platforms and from rural to urban audiences. In fact, the Twitter accounts of the MP candidates were actively tweeting different created content every day of the campaign.

Just as internet providers talk about internet access reaching the last billion, strategists discuss how campaign information reaches the last person through their WhatsApp network, which operates with a certain hierarchy, starting from the block level and then moving to the district level and the state level. Sometimes the strategists made sure content was created by a common member of the public and such content was circulated among local WhatsApp groups. For example, at the block level, the BJP started a campaign to take a selfie with something related to benefits that a common woman or man had obtained from the BJP government – a LPG gas cylinder, a newly constructed toilet, etc. – and to share it on WhatsApp. It was said that many people started sharing selfies on WhatsApp groups, including friends’ networks, which were further disseminated by party volunteers.

There was a consistent effort to remind people to vote – to achieve some voter mobilization. Targets were identified based on the shares, likes, comments, retweets, etc., in a decentralized way. For the undecided voters – people who tended to not follow the posts from party pages or party tweets – the social media cell made use of third-party online news portals (for example, ‘Namma Malenadu,’ a regional third-party news portal that was used to share narratives about the BJP). This news portal published discussions on politics and news related to youth and patriotism. Such third-party news portals were also used to expose the so-called lies being told by the opposition parties and to convey the correct information.

Another strategy was to use Facebook live or Twitter live for some of the press conferences or events – for example, an event that involved a renowned leader visiting a village. Strategists believed such a visit by an important leader to be a positive message that reached people, and the live platform showcased the event as was, before the media began setting their own narratives. Thus, the visit of BJP leader B.S. Yediyurappa to a village household was streamed live on Facebook.

There was no specific budget for social media campaigning, but it was relatively less compared to the traditional way of campaigning. The co-convenor of the social media cell mentioned ‘about 0.5% budget’ is spent on social media campaigning compared to that of traditional campaigning per constituency candidate. above shows the money spent by the BJP official account on Google and Facebook ads, which is significantly high. Accounting for the money spent at the state level would help to arrive at the money spent on campaigning in general. Google and Facebook ads were used extensively during the campaign process, and the convenor said that they sought the advice of experts on targeting from Facebook and Google during the campaign.

The same strategists measured the reach of social media content both online and offline, unlike the INC which had a separate division for measuring reach. The online measure included likes, comments, shares and retweets, whereas the offline measure also included perceptions collected by volunteers on the ground. One of the strategists remarked that ‘the real success of content can be observed when a WhatsApp message returns to them from a non-partisan friend.’

For responding to critical posts by opposition parties, they had different strategies. One could either ignore the post, or respond to the post with facts and counter-narratives and sometimes even divert to another topic. This was managed by a separate team.

The workforce during the election was four to five times larger than the team of regular volunteers. It was also said that every BJP volunteer is a social media campaigner given that each had digital access. Hence, they had a larger network of volunteers who helped with social media campaigning.

Strategy for BJP’s Bengaluru South candidate

For 20 days the BJP candidate’s team managed a successful political campaign both online and offline. Online campaigning included the creation of apps and websites for the candidate, along with social media posts coordinating with the party. It was a volunteer-driven campaign, and the budget was covered by the candidate’s team, which included boosting posts. There were 50 people handling social media campaigning under five different heads. Offline campaigning involved setting up call centres and talking to people over phone, along with traditional ways of campaigning, including door-to-door canvassing, booths on the streets, leaflets, posters and billboards. The call centres included 10 volunteers who helped to reach and influence neutral voters. This was achieved from the list of telephone numbers they had acquired; however, who prepared the list and on what basis was not revealed. The author was told that they had about 2,000 hours of campaigning done exclusively through call centres. In addition, many people were reached through entrepreneurial meetings, youth-related programmes, colleges, etc.

The campaign depicting the leadership of Prime Minister Modi and volunteers from the BJP youth wing was designed to coordinate both online and offline campaigning. A network of social media users was built, with volunteers at each pivot point who micro-managed a small group. The strategy was based on an opinion poll that they conducted to help them provide the right information and engage with the user. The content was designed based on these parameters, including accuracy, authenticity and attractiveness. The reach was measured every two hours by their team until the message came back to them. For example, a message was circulated on their WhatsApp network and the success of it was measured when the same message was received by any of their team members from a non-partisan friend. The campaign was designed differently for different platforms, and the team believed that the reach and acceptability was high in all cases.

The candidate’s rebuttal team – designed to respond to opposition party posts – was trained to observe the post’s significance and respond to it within 30 minutes of the post being shared on social media platforms. However, the team was clearly instructed not to provide any personal or demeaning rebuttals.

Janata Dal Secular (JDS)

There was only one participant, a digital strategist from the JDS party. He said that their social media campaigning is managed in-house by the party activists and volunteers, and that there was no outsourcing of digital campaigning. The party is active on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. There are also WhatsApp groups managed by the party activists and volunteers. He said that the campaign strategy was to showcase the developmental work being done by the JDS government in Karnataka state. He further added that the campaign does not focus on demeaning other parties. The content is decided by the party leaders, as the campaign is managed within the party. It was said that they do not boost the posts such as in the case of paid promotion on Facebook, and not much is spent in terms of social media campaigning.

When asked about identification of their target audience and voter mobilization, he responded that based on the engagement with their posts on social media, they identify potential users and then form a Facebook messenger group and communicate information with members. Through the Facebook page management, they also track the activities resulting from their posts. On the posts or messages by the opposition parties, he said the JDS wouldn’t criticize them, but instead focuses on providing facts and notes the achievements of the JDS party.

Digital campaigning content: the INC

Speaking about the content, INC strategists noted that most of their sources are from mainstream media, government websites, budget data, fact-checking websites, etc. Developmental programmes accomplished by the Congress government, the personal charisma of their leader Rahul Gandhi, and the party’s manifesto were some of the main topics used in the digital content for the Karnataka national election campaign. ‘Failures of the BJP government, corruption, fake news and rumours being created by the BJP, the BJP’s lack of accountability’ was also used by the INC digital strategy cell in online campaigning. One of the strategists said that the BJP won the election in 2014 due to fake news. When asked to elaborate on the type of fake news, they responded that ‘inaccurate and false information to defame Sonia Gandhi, Rahul Gandhi and their family on social media platforms’ was the reason for the party’s major loss in 2014.

When asked a question about fake news, many said that they had clear instructions not to promote or share fake news in any form. In response to another question about identifying fake news, they said that they have an internal research team to identify such news and report it to the social media team. They then, in turn, would either provide the facts or defend based on the content of the fake news. Further, they said that if there is a fake news post or story that prima facie appears factually incorrect, then they would contact the relevant leader to verify the facts. In addition, one of the participants said that he would refer to fact-checking websites; however, he also expressed that it is impossible to track all the fake news items and verify them. A question was asked about whether they promote any fake news if it favours their party and most of them said that they did not treat any fake news any differently. However, one of the participants said that he would promote fake news if it favours the party.

One of the legal advisors of the INC party said the social media cell was closely monitoring various platforms for fake news that amounts to tarnishing the image of a person and the party. He said that they filed many complaints about fake news with the cyber police in Karnataka, and were in the process of suggesting a comprehensive policy on fake news peddlers to the state government.

Digital campaigning content: the BJP

For the BJP, this campaign was an opportunity to focus on the government’s record and achievements in the previous five years under the leadership of Modi. The campaign content focused on the personal charisma of Modi, along with economic growth and corruption-free governance, among other topics. The interviewees said that the spirit of nationalism and national security also played a prime part in the campaign. In addition, the failure of the opposition party along with the instability of its coalition government in Karnataka were topics used in the campaign content.

The content was mainly driven by the vision of the BJP coupled with the party’s manifesto. A research team provided ideas for the digital content based on contemporary and historic political developments. The content was disseminated through social media as per its daily plan and the current scenario locally and nationally. Various government websites, departmental reports, budget data, national archives, and media reports were the main sources of campaign content. Visual appeal and humour were emphasized during the campaign, as such characteristics were known for having the potential to make a post go viral. For instance, one of the respondents who is a video editor said that compared to regular posts, it was easier to reach a large network of people with humorous videos.

Speaking of fake news, it was said that there was zero tolerance for such news, and it was clearly stated during the training workshop that fake news should not be encouraged, be it for or against the party. It was said that fake news would be nullified by providing facts and figures – which were obtained through various sources, including reports from government departments. One of the respondents mentioned how the opposition party had created a fake narrative around the Rafale defence deal to malign the BJP government as corrupt. In order to displace this fake narrative, the BJP organized a seminar in Bengaluru, which is home to the major defence hub in the country, and invited experts in the domain of defence and strategic studies to address a large gathering of people.

Concerned about the accountability of messages being sent on WhatsApp, the team put forth an internal norm that if information was being forwarded the person who forwarded it should be responsible for the content. In this way, they sought to reduce the spread of fake news through their networks and stop its further diffusion.

They suggested that fact-checking should be quick, and that even though fake news could be short-lived, it could still create a great deal of damage. One of the social media convenors for an MP said that a comprehensive policy framework was being drafted regarding the menace of fake news, which, among other things, included making social media platforms accountable, along with users peddling fake news. However, other social media campaigners said that it would be highly difficult for the social media platforms or government alone to take action and that there should be a shared nexus, with social media developing a mechanism to curb the spread of fake news while the government took the necessary policy measures.

Although the life cycle of social media messages is short, the impact can last much longer, and the cell therefore made every effort to reach every voter through one means or another. One of the participants who is a co-convenor of the social media cell said that the ‘first hit matters in politics’, referring to fake news. In terms of information, the first hit, whether it be on a factual story or fake news, can have an impact on voters in terms of developing perceptions or attitudes towards a leader or party.

Digital campaigning content: the JDS

The content was decided based on daily political developments in the run-up to the election. The number of posts increased a few days before the election. The content was broadly based on the former JDS Chief Minister Kumaraswamy and the achievements of former Prime Minister H.D. Devegowda. The sources of content included departments, ministries and bureaucrats.

On fake news, the respondent said they usually ignored it or alternatively provided facts to correct the myth. On the matter of identification of fake news, he said they would know clearly whether information was true or fake, and then they would discuss it through WhatsApp groups and other means, with reference to fact-checking websites. However, when fake news goes viral, it becomes difficult to handle, so they usually ignored it and instructed their volunteers to do the same. In the end, the respondent contended, fake news is indeed a threat to democracy and maligns the image of the country, and that social media platforms needed to be regulated in the same way as the traditional media.

Discussion and conclusion

Campaign strategies are developed in a dynamic process, yet at times appear random based on political developments and the occurrence of events in the run up to the vote. There is no single strategy being applied across the country by each party, but instead a multi-level tailor-made strategy that takes into account local contexts. The BJP holds the early bird title when it comes to the use of technology for election campaigning. As a result, many parties started hunting for campaign strategists and set up their own social media cells. One of the respondents from the BJP said that the INC and the JDS recruited many social media campaigners and strategists who had worked for the BJP during the 2014 election.

From the interviews with social media cell strategy teams, the BJP’s digital campaigning appeared more mature compared with that of the INC, whereas the JDS was still in a nascent stage. It should also be noted that peer pressure from the BJP seems to have been a factor for other political parties, not just in Karnataka but also across India, in setting up the necessary infrastructure for digital campaigning.

Novel and humorous content was said by respondents to reach larger audiences on social media, and it was also said that the ‘first hit matters in politics’ – be it information or misinformation. According to Pew Research, a large percentage of the population, about 68%, believes that articles seen on social media introduce them to new ideas, whereas about 55% people think that articles on social media are false/untrue.Footnote48 This strategic process of the ‘first hit’ is susceptible to the diffusion of information/misinformation through digital systems influencing and reinforcing electorates. Studies have suggested that the novelty of misinformation influences believability and diffusion of the same.Footnote49

However, it would be premature to attribute electoral victories to social media alone. Political communication is considered to function as a system, hence winning an election is a collective effort comprising various sub-systems, combining traditional campaigning with many volunteers and networks, rallies, and digital and social media.Footnote50 The social media cells interviewed in this study likely represent the most intense national election digital campaigning at the state level and city level in the country. Smartphone use in India is also expected to double in the next few years.Footnote51

Traditional media like newspapers, television, and radio have shifted to digital media platforms to promote their content. An informal discussion with the Director of the Department of Information and Public Relations, Government of Karnataka, regarding digital campaigning and the monitoring process revealed how some of the political parties shared video snippets from TV channels on social media, while that TV content was never telecasted. This strategy can be categorized among the non-mainstream ways of disseminating news stories. In addition, social media features like Facebook or Twitter live, and live streaming of campaign speeches on YouTube, among others, have partially relegated mainstream media narratives.

Although the parties mentioned that they do not advocate fake news in general, some of the campaigners mentioned that they do not mind propagating fake news if it favours their party. It was also found that third-party sites or propaganda pages were used to circulate factually misaligned or fake news. For instance, empirical research highlights ‘new media sources’ publishing online news were likely to be under the information eco-system of the BJP.Footnote52 Another study found that fake news related to the Rafale deal was used extensively during 2019 election campaigning by the INC.Footnote53 These studies further establish how the parties actually strategised in reality. Also, to a great extent we can observe the ‘professionalization of political campaigning’ – that is, the objective and subjective measures, as defined by Rachel Gibson and Andrea Römmele, among the BJP and INC parties.Footnote54

Social media and the internet can provide a coupling effect, augmenting the existing system of campaigning to boost the reachability of the campaign message among electorates. But it is highly improbable to say that social media alone, as an independent system, can win elections in India. Increased internet usage year after year suggests increased media outreach. This case study of digital campaigning in Karnataka suggests that any information becomes powerful if there is somebody to listen; to this end, one can see a large stream of information being supplied and consumed. Everybody consumes the information, but few actually question it. There is a need for developing critical thinking and a spirit of questioning, as we can expect that future campaigning will be more vigorous in trying to capture narratives from the local level to the national level.

Acknowledgment

I am grateful to the editors of this special issue and anonymous peer-reviewers for their excellent comments. I would like to thank Prof. Susan Banducci for her support and SWDTP (ESRC) for the travel grant to conduct interviews in India

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. Semetko and Tworzecki, “Campaign Strategies, Media, and Voters: The Fourth Era of Political Communication”; and Chadwick and Howard, Routledge Handbook of Internet Politics.

2. Tekwani and Shetty, “Two Indias: The Role of the Internet in the 2004 Elections.”

3. Rajagopal, Politics after Television.

4. See note 2 above.

5. Ahmed et al., “The 2014 Indian Elections on Twitter”; Chadha and Guha, “The Bharatiya Janata Party’s Online Campaign and Citizen Involvement in India’s 2014 Election”; Baishya, “#NaMo: The Political Work of the Selfie in the 2014 Indian General Elections”; and Neyazi et al., “Campaigns, Digital Media, and Mobilization in India.”

6. Semetko and Tworzecki, “Campaign Strategies, Media, and Voters: The Fourth Era of Political Communication,” 297.

7. Woolley and Howard, Computational Propaganda; Semetko and Tworzecki, “Campaign Strategies, Media, and Voters: The Fourth Era of Political Communication.”

8. “Indian Election Speaks to Internet, Nukes and Climate.”

9. Dutta, Development under Dualism and Digital Divide in Twenty-First Century India.

10. The data is collated by the author from the Facebook Ads Library report (as of June 2019) and Google Transparency report. The above figure shows spending at the aggregate level by the official BJP and INC pages and does not include region-wise or leader-wise spending.

11. Pew Research Center, “Mobile Connectivity in Emerging Economies.”

12. Ibid.

13. Flaxman et al., “Filter Bubbles, Echo Chambers, and Online News Consumption.”

14. Rao and A. M., “Karnataka.”

15. Kamath, A Concise History of Karnataka: From Pre-Historic Times to the Present.

16. Ibid.; Rao, “The Emergence of Modern Karnataka: History, Myth and Ideology.”

17. Brown, Indian Architecture (Buddhist and Hindu Periods).

18. Pani, “Experiential Regionalism and Political Processes in South India.”

19. Rao, “The Emergence of Modern Karnataka: History, Myth and Ideology,” 46.

20. Ibid.

21. “Census of India.”

22. See note 18 above.

23. The 1983 assembly election resulted in a hung assembly as no party had an absolute majority. But Janata party being the single largest party formed a coalition government with the support of BJP and other regional parties. This was the first non-Congress government formed in Karnataka led by Ramakrishna Hegde. However, the coalition lasted for 2 years, which resulted in suspension of the government and call for another election in 1985. Interestingly, in the 1985 assembly election Janata party secured absolute majority which formed a government between 1985–89 and had two Chief Ministers – Ramakrishna Hegde and S R Bommai. However, in 1989, the then CM S R Bommai lost the majority due to an internal rift within the Janata party. This resulted in imposition of President’s rule in the state of Karnataka under Article 356 of the Constitution. See Shastri, “The 2013 Karnataka Assembly Outcome.”

24. Manor, “Blurring the Lines between Parties and Social Bases-Gundu Rao and Emergence of a Janata Government in Karnataka.”

25. Manor, “BJP in South India: 1991 General Election.”

26. Manor, “Understanding Deve Gowda.”

27. Manor, “Change in Karnataka over the Last Generation.”

28. Outlook Web Bureau, “‘Serious Threat’ From Congress Leaders, No Intention Of Meeting Them: Rebel Karnataka MLAs Tell Police.”

29. BS Web Team, “Karnataka Floor Test: It’s a Win for BJP as CM Yediyurappa Proves Majority.” Eventually, the members who had resigned joined the BJP; under the direction of the Supreme Court of India, they were eligible to contest by-elections. By-elections were being held in Karnataka when this article was being written.

30. Pal, “Banalities Turned Viral”; and Jaffrelot, “Narendra Modi and the Power of Television in Gujarat.”

31. Total Assembly seats in Karnataka are 224. The number of seats shown are for the major political parties and does not account independent candidates. After the by-election in 2019 the number of seats for the BJP, INC and JDS are 117, 68 and 33 respectively.

32. Havanur, “Herr Kannada.”

33. Bajaj, “In India, the Golden Age of Television Is Now.”

34. Satya, “Mysore Akashavani Is Now 75 Years Old”; and Raha, https://www.telegraphindia.com/Culture/Style/Battleground-Bangalore/Cid/1552716.

35. TRAI, “The Indian Telecom Services Performance Indicators.”

36. Ibid.

37. Based on author’s observation of Facebook Privacy-Protected Full URLs Data Set.

39. Bhaduri, “India Unwired – Why New Media Is Not (yet) the Message for Political Communication.”

40. Frankel, “Democracy and Political Development”; Prasad, Political Communication: The Indian Experience; Willnat and Aw, “Elections in India: One Billion People and Democracy”; and Thorsen and Sreedharan, India Election 2014.

41. Thorsen and Sreedharan, India Election 2014; Kanungo, “India’s Digital Poll Battle.”

42. Shin et al., “The Diffusion of Misinformation on Social Media.”

43. Aldrich et al., “Getting out the Vote in the Social Media Era”; and Ward et al., “Digital Campaigning.”

44. Blumler, The Shape of Political Communication.

45. Chhibber and Ostermann, “The BJP’s Fragile Mandate”; and Verma and Sardesai, “Does Media Exposure Affect Voting Behaviour and Political Preferences in India?”

46. Semetko et al., “Information in India’s 2019 Lok Sabha Election: Evidence from Bengaluru.”

47. Chadha and Guha, “The Bharatiya Janata Party’s Online Campaign and Citizen Involvement in India’s 2014 Election”; Chhibber and Ostermann, “The BJP’s Fragile Mandate”; and Neyazi et al., “Campaigns, Digital Media, and Mobilization in India.”

48. Pew Research Center, “Politics in Emerging Economies Worry Social Media Sow Division, Even as They Offer New Chances for Political Engagement.”

49. Grinberg et al., “Fake News on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election.”

50. See note 44 above.

51. PTI, “Internet Users in India to Rise by 40%, Smartphones to Double by 2023: McKinsey.”

52. See note 46 above.

53. Arabaghatta Basavaraj, “Democratising or Disrupting? The Role of Social Media in the 2019 Indian Election.”

54. Gibson and Römmele, “Measuring the Professionalization of Political Campaigning.”

Bibliography

- Ahmed, S., K. Jaidka, and J. Cho. “The 2014 Indian Elections on Twitter: A Comparison of Campaign Strategies of Political Parties.” Telematics and Informatics 33, no. 4 (November, 2016): 1071–1087. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2016.03.002.

- Aldrich, J. H., R. K. Gibson, M. Cantijoch, and T. Konitzer. “Getting Out the Vote in the Social Media Era: Are Digital Tools Changing the Extent, Nature and Impact of Party Contacting in Elections?” Party Politics 22, no. 2 (March, 2016): 165–178. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068815605304.

- Arabaghatta Basavaraj, K. “Democratising or Disrupting? The Role of Social Media in the 2019 Indian Election.” In Diverse India 2019: Populism, Campaigning & Influence. Washington, DC, USA: American Political Science Association, 2019.

- Baishya, A. K. “#namo: The Political Work of the Selfie in the 2014 Indian General Elections.” International Journal of Communication 9 (2015): 1686–1700.

- Bajaj, V. “In India, the Golden Age of Television Is Now.” The New York Times, February 11, 2007. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/02/11/business/yourmoney/11india.html

- Bhaduri, A. “India Unwired — Why New Media Is Not (Yet) the Message for Political Communication.” In Social Media and Politics: Online Social Networking and Political Communication in Asia, edited by P. Behnke. Singapore: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, 2010: 39–50. https://www.kas.de/c/document_library/get_file?uuid=0c53dd19-c569-e0a9-001e-f9ffd4edc364&groupId=252038

- Blumler, J. G. The Shape of Political Communication. Edited by K. Kenski and K. H. Jamieson, Vol. 1. Oxford University Press, 2015. 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199793471.013.78.

- Brown, P. Indian Architecture (Buddhist and Hindu Periods). Vol. 1. 2. 4th ed. Bombay: D.B. Taraporevala, 1959.

- BS Web Team. “Karnataka Floor Test: It’s a Win for BJP as CM Yediyurappa Proves Majority.” Business Standard. July 29, 2019. https://www.business-standard.com/article/politics/karnataka-floor-test-it-s-a-win-for-bjp-as-cm-yediyurappa-proves-majority-119072900136_1.html

- “Census of India.” India: The Registrar General & Census Commissioner, 2011. https://web.archive.org/web/20150825155850/http://www.censusindia.gov.in/2011census/C-01/DDW00C-01%20MDDS.XLS

- Chadha, K., and P. Guha. “The Bharatiya Janata Party’s Online Campaign and Citizen Involvement in India’s 2014 Election.” International Journal of Communication 10 (2016): 4389–4406.

- Coghlan, A. “Indian Election Speaks to Internet, Nukes and Climate.” New Scientist , no. (April 8 , 2014. Accessed 19 April 2020. https://www.newscientist.com/article/dn25378-indian-election-speaks-to-internet-nukes-and-climate/:.

- Chhibber, P. K., and S. L. Ostermann. “The BJP’s Fragile Mandate: Modi and Vote Mobilizers in the 2014 General Elections.” Studies in Indian Politics 2, no. 2 (December, 2014): 137–151. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2321023014551870.

- Computational Propaganda: Political Parties, Politicians, and Political Manipulation on Social Media. Oxford Studies in Digital Politics. edited by S. Woolley and P. N. Howard, New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2019. 3–18.

- Dutta, D. K. Development under Dualism and Digital Divide in Twenty-First Century India. Dynamics of Asian Development. Singapore: Springer, 2018.

- Frankel, F. R. “Democracy and Political Development: Perspectives from the Indian Experience.” World Politics 21, no. 3 (April, 1969): 448–468. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/2009641.

- Gibson, R. K., and A. Römmele. “Measuring the Professionalization of Political Campaigning.” Party Politics 15, no. 3 (May, 2009): 265–293. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068809102245.

- Grinberg, N., K. Joseph, L. Friedland, B. Swire-Thompson, and D. Lazer. “Fake News on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election.” Science 363, no. 6425 (January 25, 2019): 374–378. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau2706.

- Havanur, S. “Herr Kannada.” The Deccan Herald, 2004. https://web.archive.org/web/20070929123334/http://www.deccanherald.com/archives/jan182004/artic6.asp

- Jaffrelot, C. “Narendra Modi and the Power of Television in Gujarat.” Television & New Media 16, no. 4 (May, 2015): 346–353. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476415575499.

- Kamath, S. U. A Concise History of Karnataka: From Pre-Historic Times to the Present. Revis ed. Bengaluru, India: Jupiter Books, 2001.

- Kanungo, N. T. “India’s Digital Poll Battle: Political Parties and Social Media in the 16th Lok Sabha Elections.” Studies in Indian Politics 3, no. 2 (December, 2015): 212–228. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2321023015601743.

- Manor, J. “BJP in South India: 1991 General Election.” Economic and Political Weekly 27, no. 24/25 (1992): 1267–1273.

- Manor, J. “Blurring the Lines between Parties and Social Bases-Gundu Rao and Emergence of a Janata Government in Karnataka.” Economic and Political Weekly 19, no. 37 (1984). 1623–1632.

- Manor, J. “Change in Karnataka over the Last Generation: Villages and the Wider Context.” Economic and Political Weekly 42, no. 8 (2007). 653–660.

- Manor, J. “Understanding Deve Gowda.” Economic and Political Weekly 31, no. 39 (1996): 3231–3232.

- Neyazi, T. A., A. Kumar, and H. A. Semetko. “Campaigns, Digital Media, and Mobilization in India.” The International Journal of Press/Politics 21, no. 3 (July, 2016): 398–416. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1940161216645336.

- Outlook Web Bureau. “‘Serious Threat’ from Congress Leaders, No Intention of Meeting Them: Rebel Karnataka MLAs Tell Police.” Outlook. July 15, 2019. https://www.outlookindia.com/website/story/india-news-serious-threat-from-congress-leaders-no-intention-of-meeting-them-rebel-karnataka-mlas-tell-police/334209

- Pal, J. “Banalities Turned Viral: Narendra Modi and the Political Tweet.” Television & New Media 16, no. 4 (May, 2015): 378–387. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476415573956.

- Pani, N. “Experiential Regionalism and Political Processes in South India.” India Review 16, no. 3 July 3 (2017): 304–323. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14736489.2017.1346405.

- Pew Research Center. “Mobile Connectivity in Emerging Economies.” Pew Research Center. March 2019a. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/03/07/use-of-smartphones-and-social-media-is-common-across-most-emerging-economies

- Pew Research Center. “Politics in Emerging Economies Worry Social Media Sow Division, Even as They Offer New Chances for Political Engagement.” Pew Research Center, May 2019b. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2019/05/13/users-say-they-regularly-encounter-false-and-misleading-content-on-social-media-but-also-new-ideas

- Prasad, K., ed. Political Communication: The Indian Experience. Vol. 2. 1st ed. New Delhi: B.R. Publishing Corporation, 2003.

- PTI. “Internet Users in India to Rise by 40%, Smartphones to Double by 2023: McKinsey.” The Economic Times. April 2019. https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/tech/internet/internet-users-in-india-to-rise-by-40-smartphones-to-double-by-2023-mckinsey/articleshow/69040395.cms

- Raha, S. The Telegraph. November 19, 2006. https://www.telegraphindia.com/culture/style/battleground-bangalore/cid/1552716

- Rajagopal, A. Politics after Television: Religious Nationalism and the Reshaping of the Indian Public: [Hindu Nationalism and the Reshaping of the Public in India]. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2001.

- Rao, K. R. “The Emergence of Modern Karnataka: History, Myth and Ideology.” In Karnataka Government and Politics, edited by S. S. P. Harish Ramaswamy and S. H. Patil. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company, 2007. 30–42.

- Rao, K. R., and A. M. Rajasekharaiah. “Karnataka.” In Karnataka Government and Politics, edited by S. S. P. Harish Ramaswamy and S. H. Patil. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company, 2007. 1–21.

- Routledge Handbook of Internet Politics. edited by A. Chadwick and P. N. Howard, London ; New York: Routledge International Handbooks, 2009. 1–9.

- Satya, G. “Mysore Akashavani Is Now 75 Years Old.” Business Standard (2013): https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/mysore-akashavani-is-now-75-years-old-110091600070_1.html

- Semetko, H. A., A. Kumar, and P. Saikia. “Information in India’s 2019 Lok Sabha Election: Evidence from Bengaluru.” In Diverse India 2019: Populism, Campaigning & Influence. Washington, DC, USA: American Political Science Association, 2019.

- Semetko, H. A., and H. Tworzecki. “Campaign Strategies, Media, and Voters: The Fourth Era of Political Communication.” In The Routledge Handbook of Elections, Voting Behavior and Public Opinion, edited by J. Fisher, E. Fieldhouse, M. N. Franklin, R. Gibson, M. Cantijoch, and C. Wlezien. London ; New York, NY: Routledge, 2018. 293–304.

- Seth, F., S. Goel, and J. M. Rao. “Filter Bubbles, Echo Chambers, and Online News Consumption.” Public Opinion Quarterly 80, no. S1 (2016): 298–320. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfw006.

- Shastri, S. “The 2013 Karnataka Assembly Outcome: Government Performance and Party Organization Matters.” Studies in Indian Politics 1, no. 2 (December, 2013): 135–152. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2321023013509149.

- Shin, J., L. Jian, K. Driscoll, and F. Bar. “The Diffusion of Misinformation on Social Media: Temporal Pattern, Message, and Source.” Computers in Human Behavior 83 (2018): 278–287. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.008. June.

- Tekwani, S., and K. Shetty. “Two Indias: The Role of the Internet in the 2004 Elections.” In The Internet and National Elections: A Comparative Study of Web Campaigning, edited by R. Kluver, N. Jankowski, K. Foot, and S. M. Schneider. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis, 2014. 150–162.

- Thorsen, E., and C. Sreedharan. “India Election 2014: First Reflections.” 2015.

- TRAI. “The Indian Telecom Services Performance Indicators.” New Delhi: Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, July 2019. https://www.trai.gov.in/sites/default/files/PIR_10072019.pdf

- Verma, R., and S. Sardesai. “Does Media Exposure Affect Voting Behaviour and Political Preferences in India?” Economic and political weekly 49, no. 39 (2014): 82–88.

- Ward, S., R. Gibson, and M. Cantijoch. “Digital Campaigning.” In The Routledge Handbook of Elections, Voting Behavior and Public Opinion, edited by J. Fisher, E. Fieldhouse, M. N. Franklin, R. Gibson, M. Cantijoch, and C. Wlezien, 1st ed. Routledge, 2017. 319–339. doi:https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315712390.

- Willnat, L., and A. Annette. “Elections in India: One Billion People and Democracy.” In The Handbook of Election News Coverage around the World, edited by J. Strömbäck and L. L. Kaid. ICA Handbook Series. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, 2008. 124–141.