ABSTRACT

In the aftermath of the First World War, widespread public commemoration of the war dead came to be focused on the war memorials erected on the squares and thoroughfares of many towns and villages in the countries involved in the conflict. For dead soldier’s families, not afforded an opportunity to honour their loved ones with the traditional rituals of mourning and interment, war memorials afforded a surrogacy for these important rites. However, the experience in Ireland was different. As Ireland embarked on a bloody and divisive journey towards political independence from Britain between 1916 and 1922, the commemoration of the 35,000 Irish men killed while fighting with the British Army during the war became highly politicized post 1919. In the nascent Irish-Free State, the socio-political space came to be dominated by nationalist rhetoric and ideologies and war memorial construction in this post-colonial context was stunted. While a national war, memorial was finally completed in Dublin by 1939 that memorial is outside the scope of this research, which instead focuses upon the construction of commemorative spaces outside the capital city, where only 12, publicly sited war memorials were completed during the period 1919–1930. This article charts the ‘life-cycle’ of these war memorials considering their planning, design, funding, location, unveiling and subsequent usage as sites for annual commemorative ceremonies of remembrance down to 1970. It highlights the range of challenges faced by organizing committees in securing sites for their memorials, while also demonstrating a heightened awareness within committees, as to how these memorials were going to be interpreted and ‘read’ by those who viewed them. Sensitivity and nuanced attention to detail with regard to the design, iconography, inscription and materials used in mediating a specific ‘Irishness’ for each memorial is detailed in illustrating how local war memorial committees tried to pre-empt challenges from those with antagonistic attitudes and views. Working within these constrained political environments, many of the resulting war memorials were based on conservative and hackneyed designs inspired by the Celtic Revival, in marked contrast to the more diverse range of memorials evident in Northern Ireland. Unveiling ceremonies provided opportunities to demonstrate the underlying purpose of each memorial as a site of commemoration for soldiers from each local area, a function which as this article articulates many fulfilled until 1970, when the outbreak of violence in Northern Ireland and the subsequent ‘Troubles’ brought a hiatus in commemoration in the Republic of Ireland.

Introduction

The desire to memorialize the war dead by bereaved relatives, former comrades, local communities and the state, gained momentum as the First World War progressed and in the aftermath of the Armistice a raft of war memorial projects were initiated in the various countries involved, and in those where the conflict had occurred.Footnote1 War memorials appeared in a range of formats and settings, ranging from the ‘practical’, meeting halls for ex-servicemen, hospitals, libraries, drinking fountains and public parks to arches, towers, gateways and monuments of a more traditional and ‘symbolic’ nature.Footnote2 This latter category included wall-mounted memorials fashioned in stone and brass, commissioned for ecclesiastical, educational and institutional settings, to those free standing publicly sited war memorial monuments located in conspicuous urban spaces which became ‘the locus classicus of remembrance’.Footnote3 As the most symbolic components of the material culture of remembrance, war memorial monuments and landscapes, have received significant academic attention over the past number of decades.Footnote4

The commemoration of Irish men killed while fighting with the British Army during World War I was highly politicized in Ireland post 1919. In the Irish-Free State, where the journey to independence had been embarked upon in a dramatic manner in a military rising – the Easter Rising – against the British authorities in April 1916, the commemoration of those who had died in British Army uniforms sat uncomfortably alongside the emerging dominant nationalist ideology.Footnote5 Nonetheless, a range of commemorative projects at parochial, institutional and public level were initiated.Footnote6 The most numerous were parochial memorials comprised of stone wall memorial tablets and bronze or brass plaques listing the names of those who had died from the local parish, installed predominantly in the ‘safe’ spaces afforded by Protestant churches. The numerical smallest grouping of commemorative projects were those that took the form of publicly sited war memorials. This article focuses on the construction and use of such publicly sited war memorial monuments, during the final years of the countries’ political union with Britain between 1919 and 1922 and in the post-colonial Irish-Free State (1922–1937) and later Republic of Ireland.

Constructing war memorial monuments: planning, siting and symbolism

As the bodies of most war dead were not returned home to their relatives for burial, war memorial monuments in countries removed from the fighting such as Australia, New Zealand, Britain and Ireland, took on an added poignancy as their ‘initial and primary purpose was to help the bereaved recover from their loss’.Footnote7 Such memorials ‘addressed the reality that the bulk of the war dead remained at the front by transporting the memory of each man in the absence of his body back to his family and home community’ ultimately bring ‘the war deep into landscapes that had escaped the realities of war’.Footnote8 The unveiling ceremony for these monuments constructed in squares and thoroughfares of towns and cities, in churchyards and in numerous other settings became ‘surrogate funeral services’ for the grieving relatives of those they commemorated.Footnote9

Erected at local, regional and national levels, the task of bringing such memorial monuments to completion was undertaken by an array of ‘agents of remembrance’ including private individuals, urban political leaders, local churches, ex-servicemen’s organizations and the state. The British response to dealing with their war dead along the Western Front resulted in the construction of over 890 war cemeteries alongside the iconic and monumental memorials at Menin Gate, Tyne Cot and Thiepval where the names of those whose remains were never recovered for burial were inscribed by the Imperial (later Commonwealth) War Graves Commission.Footnote10 In Britain as King has shown in urban areas, the local mayor frequently headed up the committee overseeing the organization of the memorial, a role in rural areas that was frequently taken by the local landowning elite many of whom had strong military connections.Footnote11 Alongside these agents, the Church of England also played a pivotal role in both organizing and providing sites for memorial monuments within the precincts of their churches.Footnote12

In Australia, many of the war memorials were commissioned by committees with a broad gender and economic representative basis which led to wider support both politically and financially for the war memorial project, while simultaneously, augmenting the connection between supporters and subscribers to their local memorial.Footnote13 While plans for several large scale monumental war memorials in New York City, faced numerous challenges, including the lack of financial support of the general public – and were ultimately shelved – as Wilson has shown district committees across the city headed up by prominent local businessmen and local officials were much more successful in soliciting financial support. By the 1930s, over 100 war memorial monuments were located across the city, exemplifying the stronger support within communities for local memorial projects.Footnote14

Selecting the design, sculptor/stonemason, inscription and location for each war memorial was frequently a protracted process, with each step subjected to lengthy deliberations. One of the most pressing concerns facing the ‘agents of remembrance’ was the design of the memorial monument. In England, a War Memorials Committee had been established in 1918 by the Royal Academy of Arts to offer advice and guidance on the appropriate forms of memorial monuments, while other agencies advised on memorial inscriptions.Footnote15 In New York City, the design of memorial monuments had to be sanctioned by the Art CommissionFootnote16 while in Australia, some states established advisory committees to offer guidance on the architectural, artistic and general merits and ‘good taste’ of the proposed memorials.Footnote17

Internationally, war memorial monuments drew upon a relatively small range of designs and motifs dominated by variations on the theme of the Christian cross, figurative sculptures of the ‘ordinary’ soldier and the obelisk.Footnote18 Crosses were amongst the most popular choices for war memorials in Britain and particularly so if the memorial monument was to be sited within a sacred space such as churchyard.Footnote19 While the Celtic cross was popular in the war memorials that appeared in the Irish Free State as this article details, its association from the latter half of the 19th century as one of the key symbols of Irish nationalism,Footnote20 meant that it proved less favourable as a choice in Northern Ireland where only two out of sixty two memorials there were inspired as such.Footnote21

Secular symbols such as the obelisk and variations on the sculpted soldier were favoured in civic spaces in both Britain and Australia.Footnote22 The obelisk outstripped the cross in popularity as a war memorial monument in Australia, at a rate of ten obelisks for each cross. Relatively easy to construct, non-sectarian in nature coupled with its universally acceptable symbolism of either death and/or glory, all added to the popularity of the obelisk.Footnote23 Surpassing the obelisk in popularity was the figurative sculptures of soldiers, so embedded with symbols of heroism, sacrifice and solidarity. In the United States, over half of all World War I memorials are free standing sculptures of soldiers with the most popular choice that of the ‘doughboy’, a nickname given to US infantry soldiers at the time. Frequently depicted in an active position with bayonet drawn, the ‘doughboy’ memorials emphasized the bravery of the soldier and the ‘warrior ideal’.Footnote24 In the Australian context, the representation of the ‘digger’ a term given to private soldiers at the time, some in contemplative others in combative poses, was also hugely popular.Footnote25 Whether looking straight ahead or with head bowed, the representation of the ordinary soldier captured the sense of patriotism and sacrifice for the nation. In Northern Ireland, several memorials such as those at Enniskillen, county Fermanagh and Ballywalter, county Down took the form of figurative soldiers augmenting the narrative of sacrifice and loyalty of the new state and its unionist population, as part of the United Kingdom.Footnote26

War memorials thus provided a vehicle through which the sacrifice and heroism of the war dead could be displayed and expressed and they came to play an important role in augmenting and informing broader political narratives of nationalism as many monuments had done generally throughout the nineteenth century.Footnote27 However, the interpretation and meaning of war memorial monuments was contested on a range of fronts. While war memorials were part of an arsenal of symbols and narratives that assisted in establishing the ‘The Myth of the War Experience, which looked back upon the war as a meaningful even sacred event’Footnote28 for Hynes such features romanticized and masked the awful conditions, harsh realities and horrors of war.Footnote29 In journalism, literature and art an ‘anti-monuments’ genre emerged in the aftermath of the war that challenged the dominant representations and narratives of war,Footnote30 a theme taken up by Wilson in his recent examination of the experience of soldiers along the Western Front.Footnote31

The highly visible sites afforded memorials, occupying important civic spaces reflected the need and desire for space to mourn, express gratitude and exhibit patriotism. However, the most overt objections to war memorials frequently centred on the sites identified for their construction. In Scotland, both the design and location of the national memorial in the grounds of Edinburgh Castle sparked significant debate and opposition.Footnote32 Initial plans outlined in 1919 to construct the national war memorial in Dublin city centre, facing the seat of the government of the new Irish-Free State met with political opposition and a relatively peripheral site at a distance from the city centre was ultimately used.Footnote33 The heated debate that surrounded the siting of the Dublin memorial encapsulates the political challenges of commemorating Irish men who had died fighting in the British army, in the post-colonial landscape of the Irish Free State.Footnote34

Outside of Dublin, many towns and cities were by the early 1920s already embellished with a range of memorial monuments. These ranged from statues to local landowners, ecclesiastical elites and nationalist political leaders and from the later 19th and early 20th century increasing numbers of memorials for those who had died in the quest to gain Irish independence such as those to the ‘Manchester Martyrs’ and those marking the centenary of the 1798 Rebellion.Footnote35 Securing sites for war memorials in these symbolically crowded landscapes proved challenging. In the broader decolonizing political and socio-cultural sphere where nationalist narratives dominated, applications to local authorities to construct war memorials in urban areas were thus met with varying levels of resistance, from outright objections to even entertaining the idea, to stringent efforts to thwart the granting of sites. Thus, resistance to the construction of World War I memorial monuments in the Irish-Free State was therefore as important as the simultaneous construction of new memorials – to the more recent events that led to political independence such as the Easter Rising and the War of Independence – being planned and developed as part of the nation building process of the nascent state.Footnote36 In Northern Ireland, over 60 war memorials were constructed. As the foci of annual rituals and ceremonies of remembrance, centred on narratives of sacrifice, loyalty and patriotism of the unionist population as part of the United Kingdom, they were important components in identify formation and nation building.

This article is focused on the process of commemorating the Great War in post-colonial Ireland through an examination of the development of publicly sited war memorial monuments, located outside of Dublin. As Johnson has observed, ‘the transformation of public, secular space into sacred sites of mourning represented an interesting admixture of civic and spiritual responsibility, political and cultural cooperation’.Footnote37 This transformation of the landscape will be assessed by charting the ‘life-cycle’ of these memorial monuments, detailing the initial planning, motivations and challenges of memorial construction; highlighting the relatively constrained designs, motifs and iconography used in their composition; examining the financing of memorials and detailing the unveiling ceremonies and subsequent usage of the memorial monuments as commemorative spaces. Although relatively few in number, as this research highlights several remained significant sites for largely unhindered public commemoration of the Irish war dead down to 1970, illustrating that not all in Ireland had succumb to the ‘national amnesia’ regarding the service of Irish soldiers in the British army.Footnote38 The approach taken in this paper decentres the existing academic focus on the role played by the state in commemoration of World War I and in particular the development of the National War Memorial Gardens at Islandbridge.Footnote39 While the process of commemoration in Dublin has already been explored extensively,Footnote40 this research provides the first comprehensive review of these processes in areas outside Dublin and thus fills a gap in the existing literature in assessing war memorials as both objects and foci of remembrance in post-colonial Ireland.Footnote41

Planning war memorials in Ireland

The planning and construction of public war memorials began relatively soon after the ending of the war and ‘those who took the initiative [to plan war memorials] … at the local and institutional level were less often officials than self-motivated activists and community leaders, the creators and embodiments of “living memory”’.Footnote42 In the Irish context, the main instigators fell into three broad categories, namely, private individuals, the British Legion, ex-servicemen’s associations and specific regiments and local committees ( and ). There was significant cross over amongst these agents of remembrance, and many of those involved in local committees were also deeply involved in ex-servicemen’s organizations.Footnote43 In researching these memorials this study draws primarily on reports from the Irish Times, which was largely unionist in its political leanings, and from a range of provincial newspapers which by the 1920s were predominantly nationalist in outlook.

Table 1. Instigators of public war memorials in Ireland, 1919–1930. Compiled by author

Private individuals

Of the 12 public-sited war memorials identified in this article, two were completed under the aegis of private individuals. The first public war memorial in Ireland was completed by 1919 at Whitegate, county Cork, under the agency of Lady Jane Penrose Fitzgerald ‘and the ladies of the district of Whitegate and Inch’.Footnote44 Fitzgerald had taken a keen interest in the war effort and the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Families Association which provided welfare for soldiers families (Irish Examiner, 5 September 1914). Her connection with this group may have motivated her spearheading the construction of the Whitegate memorial. At the other end of the country in county Louth, between March 1919 and February 1920, Sir Henry Bellingham planned and constructed a memorial at Castlebellingham, the second such publicly sited war memorial in Ireland. The loss of his son in 1915 provided a very personal impetus to that memorials construction.Footnote45 The relative speed at which these memorials were completed reflected the fact that they were planned by individuals, removing committee delays, and as they were erected in the villages belonging to these families the permission of others to erect the memorials was not required.

The British Legion, ex-servicemen’s associations and specific regiments

A number of associations each underpinned by differing political ideologies and values were formed in Ireland in supporting ex-servicemen, ‘reflecting the particular Irish problem of reconciling service in the war with the new political dispensation’.Footnote46 One of the earliest was the Irish Nationalist Veterans’ Association. Existing alongside it were the Comrades of the Great War, later renamed the Legion of Irish Ex-Servicemen, which merged with the British Legion (Southern Ireland Area) in 1925.Footnote47 Other local ex-service organizations existed such as the Cork Independent Ex-Servicemen’s Association under whose aegis the Cork city memorial was completed (Cork Examiner, 18 March 1925). However, with a critical mass of interested individuals organized through local branches, enjoying access to the organizations network of connections and financial support the British Legion emerged as the dominant ex-servicemen’s association, overseeing the construction of several war memorials post 1925. Away from the ex-servicemen’s organizations, the application by the Royal Queen’s County Regiment ‘to erect a war memorial in some prominent portion of the town of Maryborough’ [Portlaoise] was unique in the Irish context (Leinster Express, 30 January 1926).

Committees

Half of the publicly sited war memorials erected between 1919 and 1930 resulted from the agency of committees. In some instances, local grandees, in particular large landowners, many of whom also had military careers, lent their patronage to their local committees. Lord Fingall, of Killeen Castle, Dunsany a major in the Prince of Wales’s Leinster Regiment during the war, was president of the Drogheda memorial committee (Irish Times, 6 November 1925). By Spring 1919, a committee to construct a memorial at Bray county Wicklow had come together, supported by the earl of Meath and under the presidency of another local aristocratic landowner Lord Powerscourt (Irish Times, 10 February 1919). An attempt to identify its members from the 1911 Census Returns shows the more significant positions to have been occupied by the professional classes, alongside a range of representatives from other classes. Reflecting the non-sectarian nature of the committees brief, members were drawn from both the Roman Catholic and Protestant denominations. Notably, half of the 16 members of the Bray committee were female. In contrast, the Longford committee was composed entirely of males reflecting the gendered nature of a rural country town in Ireland at this time.

Funding memorial construction

In setting out to commemorate the war dead, the first decision was to make regarding the memorials form. While hospitals, libraries or halls were suggested as fitting memorials, others favoured those in traditional monumental form.Footnote48 Initial desires were frequently frustrated by a range of factors, in particular their financing. While the costs associated with the Whitegate and Castlebellingham memorials appear to have been borne by the Fitzgerald and Bellingham families, respectively, the funding of most war memorials depended primarily on private subscriptions and fundraising activities. Listings of subscriber’s names and their donation were published in the local press. While providing public acknowledgement of support received, they also proved useful in soliciting further support and publicity for the memorial projects. Over the course of several months, thirteen subscription lists appeared in the Drogheda Independent detailing the subscribers of the over £800 donated towards the cost of the Drogheda memorial (12 December 1925). The donations by numerous individuals some at a relatively modest scale captures a sense of the fervour and levels of engagement with the process of commemoration at a local level. The memorial in Cork was part-funded by several charity football matches (Irish Examiner, 30 August 1924) and by a flag-day, during which Forget-me-nots were sold (Irish Examiner, 16 March 1925).

The politics of monument siting

While decisions on memorial form and its financing were significant challenges, one of the greatest obstacles was in securing a site for the memorial as the ‘use of public space for such activity was consistently contested’.Footnote49 Memorials commemorating Irish casualties of the war were at odds with the consolidating nationalist narrative. The challenge of identifying an appropriate site for the National War Memorial in Dublin highlighted such political complexities.Footnote50 After nearly six years of discussion, a site was finally selected for the memorial in 1929 at Islandbridge, 4.8 kilometres west of the city centre. The peripheral location, ‘affording a convenient degree of invisibility’, was for many a signal of the Irish governments discomfort in dealing with the country’s war dead.Footnote51

Similar challenges surfaced when sites for memorials were being identified by authorities in Irish country towns. The debates surrounding the siting of memorials as detailed in this study illustrate the incendiary nature and politics of commemoration of the dead of World War one in the post-colonial context of the Irish-Free State, where ‘the choice of site frequently proved problematic, as local authorities had to confront diverse ideological opinions within their council chambers’.Footnote52 Attitudes to the construction of war memorials varied significantly from place to place. Depending on local circumstances, experiences and contexts, commemorative projects were either welcomed and supported, or strenuously disputed and subjected to open hostility. In some towns and cities across the Irish-Free State particularly those with military establishments and long established military connections such as Longford and Cork for example, while political objections to memorials were voiced, these were challenged and subdued by local politicians – some of whom were ex-servicemen – aware that large numbers of ex-servicemen and their families on whom they relied for support, continued to reside in these areas. However, in other garrison towns such as Fermoy, county Cork, while acts of remembrance were held during the 1920s (Irish Times, 12 November 1926), no war memorial was constructed there during this period. As the location, in 1919, of the first attack on the British army in Ireland since the 1916 Rising, the subsequent reprisal and the later attack on Fermoy in June 1920 by the army undoubtedly dampened any enthusiasm or broader public support for a memorial.

In the securing of sites, agents of commemoration were naturally anxious that their memorials were afforded prominent locations and while some applications were successful, other memorials were finally erected on peripheral sites. The application seeking a site in Maryborough [now Portlaoise] on ‘the Square, in front of the Town Hall’ for a memorial which ‘would serve a useful purpose in dividing the traffic, besides embellishing the Square’ was debated and voted upon at several meetings between January and July 1926. Considerable opposition was expressed by several urban councillors. One (Brady) ‘proposed that it be not considered’ while another (Kennedy) remarked ‘that such a thing would be source of dissension’ (Leinster Express, 30 January 1926). Councillor Twomey who considered ‘that the object of the movement was to exploit Imperialism’ was taken to task by a fellow councillor (Poole) who ‘condemned the opposition as narrow minded’ remarking that ‘as [a] staunch a Sinn Feiner [Republican] now as when he opposed recruiting … there was nothing Imperialistic or political in this proposal, and he strongly supported the grant of the site’. Other councillors favourably disposed towards the provision of a site, included Cobbe who noted that ‘although political capital had been made out of the matter it was not political’ (Irish Times, 5 March 1926) and that ‘this was an application from Irishmen who had fought in the war, and they had a perfect right to wish to erect a memorial’ (Leinster Express, 30 January 1926). Councillor Cummins also supported the proposal for a site remarking that ‘it will be a shame and a hardship on those men’s relatives that it be refused’ (Leinster Express, 26 February 1926). Discussions regarding the granting of the site rumbled on into the summer of 1926. Hard-line nationalists maintained their stance, with Councillor Tynan remarking the proposed memorial ‘was an insult to the men who went out to war, instead of being a compliment. He would not allow them to be put up. They went out with the idea that Ireland would be free, but that was not so’ (Leinster Express, 7 August 1926). A site for the memorial – although not the one initially sought – was finally granted in August 1926.

The suggestion by Labour councillor and British Legion member Philip Cunningham to Tullamore Urban Council in 1926 that a war memorial be constructed was supported by Councillor Lumley who considered it ‘ a very worthy object … the men who went out voluntarily and sacrificed their lives in the war performed deeds of heroism which Irishmen should not forget’. The sentiments of Councillor O’Connor that ‘the war was, we were told a war to end war, and for the freedom of small nations, but what has it done?’ (Irish Times, 26 January 1926) however reflected nationalist attitudes. Ultimately, the council granted a prominent site for the memorial facing the town hall (Irish Times, 4 June 1926).In 1927, the British Legion Sligo branch applied to the town corporation for a site in front of the town hall for a memorial (Sligo Champion, 5 November 1927). This prestigious site was refused, however another central site was secured. However as the foundations were being laid shortly before the memorials unveiling they were deemed unstable due to underlying drainage and the site was abandoned (Irish Times, 22 October 1928). Frustrated by these setbacks, it was hurriedly decided that the memorial be sited in a peripheral location () on the edge of the town on a private site belonging to the president of the local branch of the Royal British Legion.Footnote53 Similar problems were also faced in Nenagh, county Tipperary. Having identified a potential site on the square outside the town’s courthouse, the local committee were informed that the site had already been granted to the ‘old Sinn Fein executive’ for the purpose of erecting a memorial ‘for those who had lost their lives in the fight for Irish freedom’ (Nenagh Guardian, 28 April 1928). Failing to secure a central location, they retreated to a peripheral location on the edge of the town, where the memorial was installed opposite the ex-servicemen’s hall.

Figure 2. Sligo war memorial. Courtesy of www.irishwarmemorials.com

In contrast, the Drogheda war memorial committee enjoyed the backing of the town’s corporation who provided them with a prominent site (Drogheda Independent, 14 November 1925). Likewise in Limerick city, the request for a memorial site met with relatively little objection when it was discussed by the Corporation Improvements Committee in June 1928 being passed by a majority of 22 to 4. The main objections from Councillor Gilligan who was ‘opposed to the memorial on national grounds’ and Councillor O’Callaghan who ‘threatened to have it taken down when it was erected’ reflected their nationalist politics.Footnote54 Similar levels of majority support in granting a war memorial site was also witnessed in Longford where the urban council voted in a majority of seven to two councillors that a site ‘situate in the most prominent part of the town’ be granted. The result greeted by ‘great cheering outside the barrier’ illustrates both the public appetite for the memorial there and the town’s long established heritage as a garrison town (Longford Leader, 24 May 1924). Sites in private ownership such as those at Castlebellingham and Whitegate as already noted and that of Bray, county Wicklow, which was donated by the local railway company were secured, it appears without much angst (Irish Times, 10 February 1919).

On the other end of the spectrum, the outright refusal to entertain the notion of allowing a war memorial was exemplified in Wexford town. As the epi-centre of the 1798 Rebellion against British rule in Ireland, Wexford town already boasted a magnificent bronze statute entitled ‘Pikeman’ depicting an insurgent, which had been unveiled in the town’s main square in 1905.Footnote55 A raft of such memorials commemorating events and individuals involved in the quest to gain independence from Britain appeared on the streets of Irish towns and cities during the later 19th and early 20th century.Footnote56 In this particular context, it was therefore perhaps unsurprising that an application ‘for permission to erect a tablet to the memory of deceased sailors and soldiers’ in Wexford town was on the mayor’s recommendation and the agreement of the corporation ‘withheld until the Irish question was settled’ (Irish Times, 7 December 1920).

Memorial designs and inscriptions

Celtic crosses and ‘Irishness’

Across Europe, war memorials drew inspiration from a range of secular, religious and militaristic themes and motifs in their design. The use of the cross, a ‘symbol of Christ’s Passion and Resurrection – suffering and triumph – was the most apposite and concise form for a war memorial’ becoming one of the most popular designs adopted in Britain.Footnote57 In Ireland, the unique native form of the cross, the Celtic cross, which had become popular during the 19th century Celtic RevivalFootnote58 was adopted as a design for many First World War memorials.Footnote59 The Bray memorial committee ‘became enamoured of a Celtic cross, which was absolutely Irish from the first to the finish and could not be mistaken for anything else’ (Irish Times, 10 February 1919). Also wishing to allay fears at the outset, the Sligo war memorial committee expressed their desire to ‘erect just a simple Cross’ () (Sligo Champion, 5 November 1927). With the exceptions of the Cork, Limerick, Portlaoise and Tullamore memorials, the others took the form of a Celtic cross. The pre-Reformation origins of the Celtic cross,became the ‘preferred design because of its general public acceptability’ appealing as it did to Catholics and Protestants alike.Footnote60 In employing this distinctive ‘Irish’ design for the memorials, local organizing committees sought to dispel the criticisms of those who questioned their motivations and interpreted war memorials as imperial monuments celebrating the British army rather than commemorating ordinary Irish soldiers.

Breaking away from the cross-motif, the Maryborough [Portlaoise] memorial was inspired by a specific ancient ‘Irishness’ taking the form of church or tomb-like structure based on the 10th to 12th century Hiberno-Romanesque style, which had remained ‘popular at the turn of the century [20th century] as a symbol of Irishness’.Footnote61 Designed by architect and engineer Thomas Scully, Waterford and constructed by Hearne and Son, Waterford, the memorial also housed a freshwater drinking spout with small metal cups attached by chains incorporated into the structure (). This more distinctive memorial may in part be accounted for by the fact that it was designed as a regimental memorial.

Figure 3. Maryborough [Portlaoise] war memorial. Courtesy of www.irishwarmemorials.com

![Figure 3. Maryborough [Portlaoise] war memorial. Courtesy of www.irishwarmemorials.com](/cms/asset/8d16e228-98ed-4a53-b955-227ebf4559b9/rfww_a_1969261_f0003_oc.jpg)

Agents of remembrance in the Irish-Free State also sought to communicate the ‘localness’ of memorials, not alone in terms of those they commemorated but also in the use of local materials and craftsmen in their construction. A narrative of the purely ‘Irish’ and ‘local’ composition of memorials in terms of design, production and erection was constructed in gaining broader support and acceptance of war memorials, while simultaneously suppressing opposition which argued that memorials were a waste of money in a country enduring austerity and recession. The application for the Maryborough [Portlaoise] memorial detailed that it ‘would be built of stone, quarried and cut in the county and Leix [Laois] … [and that a] county contractor and labour would be employed’ (Leinster Express, 30 January 1926). The report on the unveiling of Drogheda’s memorial carried in the Drogheda Independent on 14 November 1925 highlighted that the limestone used had been sourced from Sheephouse Quarries, Drogheda, the bronze plates made by Rooney Brothers in Dublin while the ornate surrounding metal railings had been made by Farrell and Sons, Beauparc, county Meath, while both the general contractor and architect overseeing the construction of the memorial were both Drogheda based. At Sligo, the memorial ‘the work of Mr Patrick Scanlon, Cairns’ Hill, Sligo’ was composed of ‘limestone taken from the Ballygawley (Co. Sligo) Quarry’ (Irish Times, 22 October 1928) while the Nenagh memorial was designed by local man Owen Gill and ‘carved by the well-known North Tipperary stone carver, Michael McLoughney’ (Nenagh Guardian, 7 September 1985).

Consequently, in contrast to the memorials constructed in Northern Ireland, designed and executed by artists and architects the majority of whom were British,Footnote62 the memorials in the Irish-Free State were overwhelmingly the work of artisan stonemasons. Armed with formulaic designs, they adapted their cemetery memorials as public war memorials. The dominance of stone – cheaper than bronze – as the main material of choice also stands in stark contrast to memorials in Northern Ireland and further afield, where bronze and a variety of other materials were used.

Cross of sacrifice and obelisks

In the larger urban centres of Cork and Limerick, more recognizably ‘British’ war memorial designs were adopted. In Limerick, the memorial was a variation on the well-known Cross of Sacrifice which had been designed in 1918 by Sir Reginald Blomfield’s for the Commonwealth War Grave Commission. Designed and sculpted by the well-known firm of C. W. Harrison of Dublin, it was reported that while the ‘Blomfield crosses are usually executed in Portland stone … in this instance … an Irish material has been selected’ again bringing a specific ‘Irishness’ to the memorial (Irish Times, 9 November 1929).

The Tullamore and Cork memorials were both designed as obelisks. The only ornamentation on the plain limestone obelisk at Tullamore designed by the renowned Francis William Doyle Jones and sculpted locally is the relief carving of an inverted sword set within a laurel wreath, which takes on a cross like symbolism surrounded by the traditional symbols of honour and victory.Footnote63 The Cork obelisk provides the only example from this era of commemoration where a soldier is depicted (). The lack of soldier figures and military motifs generally are the single most obvious feature of the war memorials constructed in the Irish-Free State, in contrast with the broader usage in Britain and further afield of the soldier figure as an allegory of the ordinary soldier. This dearth reflected the fear that the memorials ‘would have provoked negative nationalist reactions, even destruction’.Footnote64 Carved in relief in limestone, the soldier depicted on the Cork memorial captures the experience of an ordinary soldier, wearing the uniform of a local regiment the Munster Fusiliers, his head bowed and gun reversed. Despite the militaristic motifs as Hill has noted, ‘it is his air of melancholy and meditation that dominates’.Footnote65

Figure 4. Cork war memorial. Courtesy of www.irishwarmemorials.com

The majority of agents of remembrance operating in the Irish-Free State during the 1920s were inhibited by the prevailing political strictures, economic constraints and the broader conservative religious and artistic climate of the time from pursuing more imaginative designs for their specific war memorial. One of the most striking aspects of the collection of memorials constructed in the Irish-Free State is the lack of figurative soldiers as components of the memorials, contrasting so markedly with those executed elsewhere. Whilst most of the resulting war memorials followed tame and hackneyed designs, this was a deliberate strategy to minimize contention around their location in public spaces.

Inscriptions

While memorial design was paramount in the initial mediation of meaning to those who viewed them, the discrete inscriptions on memorials are also insightful expressions of their purpose and worthy of scrutiny. Most inscriptions were intentionally left relatively short and factual, so as to be universally acceptable in the charged Irish political environment. The inscription on the Drogheda memorial exemplifies such succinctness, ‘In honoured memory of those from Drogheda and district who gave their lives in the Great War’. The ‘local’ nature of the memorials was again emphasized through the use of placenames. At Nenagh, the memorial was ‘Erected to the memory of those from Nenagh and District who fell in the Great War’, while the Castlebellingham memorial commemorated those from the local ‘parishes of Kilsaran, Dromiskin and Togher’.Footnote66

Reflecting the broader political tensions in the newly independent Ireland, the inscription on Tullamore’s memorial ‘erected to the glorious memory of the men of Offaly/King’s County who gave their lives in the great war of 1914–1919ʹ sought to please all political persuasions by using both names for the county. The ‘manliness’ and ‘sacrifice’ of the war dead found expression in some of the inscriptions including that at Sligo which was erected ‘In Glorious Memory of the Men of the Town and County of Sligo, who Gave their Lives in the Great War, 1914–1918ʹ; on the Longford memorial those who died were described as ‘gallant soldiers’.

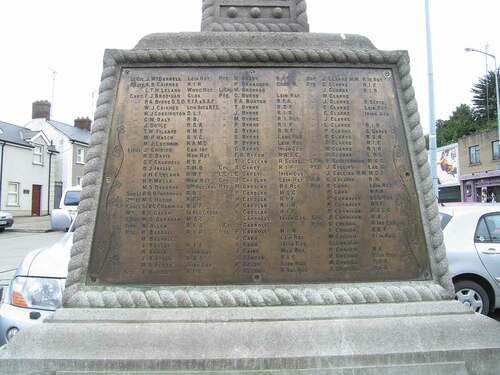

The inscribing of fatalities names on war memorials was of symbolic significance in bringing ‘the dead back home’ to their grieving relatives. The Drogheda memorial () had 368 names inscribed on it, at Portlaoise (170), Bray (168), Cahir (88), Castlebellingham (50) and 34 on the Whitegate memorial. The ordering of the names takes various forms on the memorials, with some such as the Castlebellingham memorials arranged by date of death and then rank of individual commemorated. A broad alphabetical ordering is employed in others attempting to perpetuate the ‘equality encountered on the battlefield’.Footnote67 In Drogheda, such an approach was adopted with the rank and regiment of each individual indicated, while a similar ordering was taken in Bray, however only those above the rank of private had their rank and details of their awarded medals listed. The use of bronze panels in both Bray and Drogheda facilitated the inclusion of such level of detail for relatively large numbers of names when compared to inscriptions engraved directly into stone (). In Cork, the names of the war dead appear to have been inscribed in a random order. This may have resulted from the fact that only those who wished to have the names of their war dead inscribed on the memorial and paid for it at ‘a very reasonable charge’ were included, with the inscribing occurring as soon as the name was submitted (Irish Examiner March 4 1925).

Figure 5. Drogheda war memorial. Courtesy of www.irishwarmemorials.com

Figure 6. North panel Drogheda war memorial. Courtesy of www.irishwarmemorials.com

The significant numbers of war dead associated with memorials in the larger towns and cities of Longford, Limerick, Nenagh, Tullamore and Sligo meant it was impractical to inscribe individual names. The inscription on Limerick’s memorial was ‘to the memory of 3,000 officers, N.C.O.’s and men of Limerick City and County … who had died in every quarter of the earth and on its seas’. Separately ‘Rolls of Honour’ in book format were compiled for those commemorated on the Limerick (Irish Times, 2 November 1929) and Tullamore memorials (Irish Times, 26 November 1926).

As the Maryborough/Portlaoise memorial commemorated those from one specific regiment, it was perhaps not unusual that the surnames would be arranged alphabetically by rank from lieutenant-colonel to private. The names of those with the rank of sergeant and below were preceded by their service number. Uniquely in the Irish context, the names of the Cahir memorial are arranged alphabetically within the broader branches of the armed services, namely, the navy, army and air force. The division of the Cahir names in this manner and the inclusion of the inscription ‘Their name liveth for evermore’ which came to adorn Sir Edward Luytens ‘Stones of Remembrance’ across Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemeteries, was unique in war memorials in independent Ireland (). These features most likely the result of the influence of a number of former high ranking military figures in the realization of the war memorial there (Irish Times, 10 November 1930).

Figure 7. Cahir war memorial. Courtesy of www.irishwarmemorials.com

Another component of these inscriptions worthy of consideration is the insights which they provide into who had overseen and funded their construction. In Cork, the inscription records that the memorial was ‘Erected by public subscription under the auspices of the Cork Independent Ex-Servicemen’s Club, in memory of their comrades’ while the inscription on Bray’s memorial informs ‘This cross is erected by the people of Bray’. On Longford’s memorial, the inscription noted that ‘this cross was erected by the generous subscriptions of their sorrowing relatives, comrades and sympathisers’. Including this information in the inscription accentuated another aspect of the memorials ‘localness’ highlighting that they had resulted from grassroot commemorative activity and had not been imposed by an ‘outside’ agency. A unique gendered dimension to commemoration of the war dead comes from the inscription on Whitegate memorial which informs that ‘We women here have set the Holy Cross’.

As Jeffrey has remarked one of the key questions, these inscriptions may be able to answer was ‘Why all these Irishmen died?’.Footnote68 The inscription on Whitegate memorial noted simply that it was for those ‘who died that we might live in safety’. At Bray, the soldiers had given ‘their lives for their country in the Great War’. The use of the term ‘their country’ was a useful way of circumventing the sensitive topic of individual identity and loyalty. Conversely, the Castlebellingham memorial was for those who had ‘died for Ireland in the Great International War. 1914–1919ʹ. The plea made by John Redmond the leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party in 1914 to Irishmen to enlist in the British army inspired the inscription on the Cork memorial which was for those ‘who fell in the Great War fighting for the freedom of small nations’. The reasons highlighted by agents of commemoration as to why soldiers died reflected a nuanced understanding of Ireland’s evolving political landscape post-Independence and varying political heritages and identities.

Unveiling ceremonies

The war memorials unveiling was a significant stage in its life cycle. The Irish Times (16 November 1928) report on the unveiling of Portlaoise’s memorial described it as ‘dignified and impressive’ words which capture the prevailing atmosphere and mood of these ceremonies. The dates selected for unveiling added further symbolism. The selection of St Patrick’s Day (17 March) for the unveiling of Cork’s memorial was more by accident than by design, as the memorial completion planned for November 1924 was delayed as the quarry supplying the stone, had been flooded (Irish Examiner, 4 March 1925). Armistice Day proved the most popular date for unveiling ceremonies, with six of the twelve revealed to the public for the first time on that day including that at Drogheda in November 1925. This was an impressive and carefully choreographed ceremony and a similar format of military procession, speeches, unveiling by a distinguished guest and the observation of 2 minutes silence, followed by wreath laying, was evident at varying scales at other unveiling ceremonies. The procession order that formed up on Drogheda’s Fair Green included the:

Legion Brass and Reed Band; Colonel Leonard Fife and Drum Band; Drogheda Brass and Reed Band; Drogheda Corporation, ex-servicemen maimed or wounded; members of the Drogheda Legion bearing a banner inscribed: “Drogheda Remembers Her Relatives of the Fallen, Glorious Dead”; wreaths, banners; general public which included about 30 members representing the Longford Legion … Some members of the Labour Societies; Grammar School Boys.

The procession made its way through the town falling into a ‘four deep formation’ around the memorial on St Mary’s Square. A platform party comprised of distinguished guests and dignitaries took their place and Drogheda’s Mayor who wearing his mayoral chain and ‘attended by the Sword and Mace bearer’ opened proceedings (Drogheda Independent, 14 November 1925). Following speeches and the unveiling of the Union Jack draped memorial the assembled crowd were requested to ‘stand in two minutes’ silent remembrance of those 50,000 Irishmen who lie in foreign fields’, a sombre moment followed by the sounding of the Reveille and wreath laying.

The symbolism employed in these ceremonies at times appeared at odds with the broader emerging narrative of independent Ireland. The continued use of the Union Flag as a covering for some of the memorials prior to their unveiling is notable, but perhaps unsurprising. Like the Drogheda memorial, the Cork memorial was also draped in the Union Flag before it was unveiled in 1925 (Irish Examiner, 18 March 1925). Attempting to cater for the hybrid identities and loyalties, the memorial in Tullamore was draped in both the Irish tri-colour and the Union Jack (). References to the English monarch and the singing of the English national anthem ‘God Save the King’ also featured in some of the ceremonies. Lord Castletown’s exhortation of ‘God save the King’ and ‘our dear country’ in concluding his speech at the Portlaoise unveiling catered for various political allegiances.

Figure 8. Tullamore war memorial draped in Union Flag and Irish Tricolour before unveiling, 1926. Courtesy of Offaly History Centre, Tullamore

Selecting an individual to unveil the war memorial was an important consideration as it lent an added dimension to the spectacle of the event. Sir William Hickie, who had commander of the 16th Irish Division and as an individual who had continued to involve himself with and champion the well-being of Irish ex-servicemen was a popular choice unveiling three of the 13 memorials. Part of the British military establishment, yet with strong Irish credentials Hickey appealed to a range of political tastes. Brigadier General Hardress Llyod, a celebrated polo player who had won a silver Olympic medal for the Irish team in 1908 unveiled Tullamore’s memorial (Offaly Independent, 13 November 1926).

As Winter has remarked ‘their [war memorials] initial and primary purpose was to help the bereaved recover from their loss’.Footnote69 As most bereaved relatives of the war dead were denied the opportunity to go through the traditional processes in grieving the loss of a loved, planning a funeral and bringing some finality and closure to their death. For many grieving relatives the unveiling ceremonies acted as ‘surrogate funeral services’.Footnote70 Newspaper reports poignantly capture this dimension of the ceremonies. At Drogheda ‘For a long two minutes a breathless silence reigned over that vast crowd, scarcely broken by the muffled sob here and there where a mother clasping a wreath in nervous fingers thought of a son who went out into Armageddon and did not come back’ (Drogheda Independent, 14 November 1925). The Offaly Independent (13 November 1926) noted that at the Tullamore ceremony ‘amongst the most moving sights of all was the appearance in large numbers of the fathers and mothers, widows and other dear ones of the men who never returned from the battlefields’. At the unveiling of Cahir’s memorial the Irish Times (10 November 1930) reported that ‘About a dozen war widows and a boy Michael Riordan, son of a soldier killed in the war, wearing his father’s medals were in the procession’.

In Cork city ‘many thousands lined the streets’ as the procession made its way to the unveiling ceremony on the South Mall (Irish Times, 18 March 1925). The Longford Leader (29 August 1925) reported that Longford ‘town was filled with interested onlookers who thronged the sidewalks’ for the unveiling ceremony.Footnote71 The significant numbers in attendance at the unveilings illustrate ‘the large reservoir of passive support’ for these memorials.Footnote72 However, the highly politicized nature of memorials and commemoration remained evident, exemplified in the absence of the mayor and corporation of Limerick and lack of official public representation at the unveiling of the city’s memorial in November 1929.Footnote73

Ireland’s war memorials 1919-1970: use, abuse and oblivion

Although the experience of commemorating the war dead in Dublin has been explored in some depth by academics, little attention has been given to how such activities were played out at war memorials outside of Dublin down to the 1970s.Footnote74 Until 1939, these memorials became the foci for the annual rituals of commemoration on Armistice Day, and from 1945 onwards on Remembrance Sunday.Footnote75 These observances afforded relatives of the dead and sympathetic civilians an opportunity to publicly commemorate. At the memorials detailed in this article, ex-servicemen, frequently headed by a local band would parade to the memorial, where a short act of remembrance would take place, followed by the laying of wreaths and a return parade. Frequently, these events were preceded by religious services in the local Protestant and Roman Catholic churches.

The absence of publicly sited war memorials in many Irish towns did not dissuade ex-servicemen in publicly marking Armistice Day during the 1920s and 1930s. The Irish Times (12 November 1926) in reporting on the observation of Armistice Day 1926 noted that at Mountmellick, county Laois ‘the Protestant and Catholic ex-Service men “formed up” in the market square and the “two minutes” silence was observed’. In Templemore, county Tipperary, after attending religious services ‘the men fell in and marched through the town carrying their flag. Having reached the market square at 10.55 they were halted, the Last Post was sounded by a bugler, and the two minutes silence was observed’. Further south in Fermoy, county Cork the ‘men gathered on Pearse square, wearing their decorations’ and after the act of remembrance ‘subsequently paraded with their band through the principal streets, after which they returned to the square where they dismissed’. The juxtaposition of ex British Army servicemen assembling on a square named after Padraig Pearse, one of the leaders of the 1916 Rising, captures the complexities of world war commemoration in post-colonial Ireland.

The broader evolving political context in Ireland during the 1930s and 1940s as the country severed remaining symbolic political links with Britain gradually hastened the side-lining of remembrance. As Jeffrey has observed ‘In Southern Ireland the problem of the symbolism of the war memorials was exacerbated by the ceremonial surrounding them, especially in the annual November Remembrance services’Footnote76 which as he noted Republicans ‘saw as an annual affirmation of British imperialist values’.Footnote77 Support for Armistice Day ceremonies remained significant during the 1930s. Over 3,000 participated in ceremony at Sligo in 1936 (Irish Times, 16 November 1936), while at Roscrea, county Tipperary, in 1937 over 500 participated (The Nationalist (Tipperary), November, 141937). Reflecting Ireland’s neutrality during World War II, all military parades were banned by the government, however parades to war memorials resumed in 1945. The Drogheda Independent (17 November 1945) noted that over 200 ex-servicemen from both wars had parade at Drogheda that year. Post 1945, new inscriptions on the Cork city, Limerick, Nenagh, Sligo, Tullamore and Whitegate memorials recorded the names and highlighted the involvement of Irish servicemen and women with the British armed forces during the Second World War, resulted in a renewed focus and significance of these memorials as sites of remembrance and commemoration ().

Figure 9. Major Hutton-Bury at Tullamore war memorial circa 1950s. Courtesy of Offaly History Centre, Tullamore

During the 1950s, anti-British sentiments simmered beneath the surface in Ireland and commemorative ceremonies were seen as being synonymously British. Addressing the Sligo commemorations in 1953 John Fallon, remarked ‘that he would like it to be realised that the occasion was in no way a political one’ (Sligo Champion, 14 November 1953). The same year the wreaths laid at the Limerick city memorial were maliciously removed (Irish Times, 10 November 1953). As the ‘border campaign’ by Republicans ignited in the late 1950s, memorials perceived as ‘British’ were attacked.Footnote78 In 1956 and 1958, unsuccessful attempts were made to blow up the National War Memorial Garden in Dublin.Footnote79 In August 1957, Limerick’s war memorial was extensively damaged by a bomb blast.Footnote80 Although the threat made in March 1966 that Drogheda’s memorial ‘would get the same treatment as Nelson’Footnote81 never materialized it illustrates the intense emotions that these memorials evoked (Drogheda Independent, 19 March 1966).

While some memorials remained symbolic sites of commemoration, by the 1960s others gradually lost their significance. Dwindling numbers of veterans and the decline in scale and trapping was noticeable. In Sligo in 1963, there was no music, while by 1965 in Drogheda just 60 individuals ‘composed mainly of men who had fought in the First World War’ paraded (Drogheda Independent, 20 November 1965). Delivering the oration at the 1969 Sligo Remembrance Sunday parade Revd T. C. Davis noted that ‘those who had gathered for the parade were ageing men and it was fitting that they should be allowed to dream their dreams of old ideas and old comradeships’ (Sligo Champion, 14 November 1969). External factors were to bring a permanent hiatus to public commemoration in the south of Ireland as the Northern Ireland ‘Troubles’ began in 1969. The Irish Times (9 November 1970) noted that ‘half a centuries tradition’ had been broken in Cork in 1970 as the Remembrance Day parade was cancelled. War commemoration retreated into the private space of Protestant churches in the Irish Republic post 1970, remaining confined there until the mid-1990s when some moves to retrieve the memory of those who had died was initiated.Footnote82 This is an ongoing process and some impressive memorials have emerged as a result of the conducive atmosphere that emerged in the wake of the Northern Ireland ‘Peace Process’ with its emphasis on reconciliation through shared heritage and the Irish government’s ‘Decade of Centenaries’ programme of commemorations.Footnote83

Conclusion

The desire to commemorate Irish casualties of the First World War in the form of publicly sited war memorials faced a complex range of challenges in the Irish Free State. Grieving relatives and those supportive of the ideals of commemoration who sought to engage with the broader wave of commemoration manifested by war memorial construction evident in Britain and in other European countries, were not favoured with universal support in post-colonial Ireland. As this article has highlighted the construction of a war memorial in any particular town or city was primarily dictated by the response from local urban government and as this article has shown this varied significantly from place to place. Urban councillors, ideological opposed to commemoration of Irish soldiers who died fighting in the British army vigorously opposed war memorial construction. Countering this antagonism were councillors supportive of the process who did all in their powers to smooth the path towards memorial completion.

Frequently, working within hostile political and social environments the intense desire to dispel notions that these war memorials were ‘British’ was notable and a narrative centred on the ‘localness’ and ‘Irishness’ of each was promoted. This narrative was augmented during the planning, design and construction phases of each memorial. Thus, memorials commemorated those from a particular locality, region or county; those instigating the memorials construction were drawn from within and across the local community; the funding was sourced locally; the design for many of the memorials heavily influenced by Celtic motifs reflected a uniquely native dimension, while the craftspeople who sculpted and erected the memorials and the materials from which they were made were ‘local’. Northern Ireland’s publicly sited war memorials, in stark contrast to those found in the Irish Free State, were overwhelmingly influenced by British standards. As conspicuous landscape components, they became significant and symbolic sites, demarcating the political and ideological allegiances of the unionist population. Within the political and social environment of the Irish Free State, the majority of war memorials drawing heavily upon traditional and conservative Celtic motifs in their design, blended into the existing landscape. Those that followed more traditional ‘British’ designs such as the Cross of Sacrifice at Limerick attracted notice that would ultimately result in destruction.

Unveiling ceremonies also provided opportunity to reiterate the motivations and purposes of memorials as sites of remembrance, grieving and commemoration. These carefully choreographed events were significant in easing acceptance of the memorials and the large crowds attending indicated significant levels of public support for the memorialization of the war dead in the Irish-Free State. In highlighting the continued use of some of the war memorials as the foci of remembrance activities down to 1970, this article has also sought to challenge existing generalizations and assumptions regarding the existence and extent of such commemorative activities in the Irish-Free State and Republic of Ireland. By focusing on areas outside of Dublin, this article has shown that such acts remained annual events at some sites on Remembrance Sunday until 1970, when the outbreak of violence in Northern Ireland and the subsequent ‘Troubles’ brought a hiatus in commemoration in the Republic of Ireland.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. King, Memorials of the Great War in Britain, 58–69; Moriarty, “The Material Culture,” 653; and Van Ypersele, “Mourning and Memory,” 579.

2. Moriarty, “The Absent Dead,” 12–37; Inglis, Sacred Places, 138–44; and Winter, Sites of Memory,78–98.

3. Winter, Remembering War, 135.

4. See for example Moriarty, “The Material Culture,” 653–61; Wilson, “Remembering and forgetting the Great War,” 88–100; and Wingate, Sculpting Doughboys, 15–52.

5. Jeffery, “The Great War,” 150.

6. Leonard, “Lest we forget,” 59 and Irish War Memorials http://www.irishwarmemorials.ie (March 9 2020).

7. Winter, Sites of memory, 95-6.

8. Van Ypersele, “Mourning and Memory,” 580.

9. Johnson, Geography of Remembrance, 102.

10. Heffernan, “For ever England,” 306–11.

11. King, Memorials of the Great War in Britain, 30–1.

12. Walls, “Lest we forget,” 132-3.

13. Inglis, Sacred Places, 123–35.

14. Wilson, “Remembering and forgetting the Great War,” 97.

15. Turner, “The poetics of permanence?” 75.

16. Wilson, “Remembering and forgetting the Great War,” 95.

17. Inglis, Sacred Places, 149–54.

18. For detail on figurative memorials in Britain see Moriarty, “The Absent Dead,” 19–37.

19. Walls, “Lest we forget,” 136–7.

20. Murphy, Art and Architecture of Ireland, 385-8.

21. Switzer, Unionists and Great War Commemoration,81–2.

22. King, Memorials of the Great War in Britain, 106–13; and Inglis, Sacred Places, 160–72.

23. Inglis, Sacred Places, 160.

24. Wingate, Sculpting Doughboys, 7.

25. Inglis, Sacred Places, 165–6.

26. Switzer, Unionists and Great War Commemoration, 75–80; and Murphy, Art and Architecture of Ireland, 533-6.

27. Johnson, “Cast in stone” 54–7; and Jacob & Pearl, War and Memorials, 1–21.

28. Mosse, Fallen Soldiers, 7.

29. Hynes, A War Imagined, 270.

30. Ibid.; Hynes, A War Imagined; and King, Memorials of the Great War in Britain, 13–4.

31. Wilson, Landscapes of the Western Front, 123–70.

32. Macleod, “Memorials and Location,” 79–84.

33. D’Arcy, Remembering the War Dead, 172–91.

34. Johnson, Geography of Remembrance, 84–94.

35. Murphy, Art and Architecture of Ireland, 483-4 & 504-5.

36. Hill, Irish public sculpture, 150–86; and Turpin, “Monumental Commemoration,” 107–12.

37. Johnson, Geography of Remembrance, 103.

38. Martin, “1916: Myth, Fact, and Mystery,” 68.

39. For more on the site selection, construction and subsequent unseemly fate of the Irish National War Memorial Gardens down to the 1980s see Johnson, Geography of Remembrance, 84-94 & 108-10; and D’Arcy, Remembering the War Dead, 172-191.

40. Leonard, “Lest we forget,” 64–7; Leonard, “The Twinge of Memory,” 99–109; and D’Arcy, Remembering the War Dead, 353–7.

41. Taaffe, “Commemorating the Fallen,” 18-22.

42. Van Ypersele, “Mourning and Memory,” 579.

43. Ibid.

44. Lee, “Memorial cross at Whitegate,” 49.

45. Hall, “The Castlebellingham War Memorial,” 450.

46. Jeffery, “The Great War,” 149.

47. Jeffery, “The Great War,” 148-50; and Johnson, Geography of Remembrance, 96.

48. Jeffery, “The Great War,” 146-7; and Van Ypersele, “Mourning and Memory,” 578-82.

49. Johnson, Geography of Remembrance, 111.

50. Johnson, Geography of Remembrance, 108-10; Jeffrey, “The Great War,” 152; and Fitzpatrick, “Commemoration in the Irish Free State,” 192.

51. Dolan, Commemorating the Irish Civil War, 40.

52. Johnson, Geography of Remembrance, 103.

53. For more on the political discussions regarding the siting of the Sligo memorial see Johnson, Geography of Remembrance, 103-4.

54. Moloney, “The Limerick War Memorial,” 116.

55. Hill, Irish public sculpture, 122.

56. Johnson, “Sculpting Heroic Histories,” 84–91.

57. Hill, Irish public sculpture, 189.

58. For more on the Celtic Revival and the Celtic cross as part of this see Murphy, Art and Architecture of Ireland, 388-90.

59. Hill, Irish public sculpture, 190.

60. Johnson, Geography of Remembrance, 98; and Turpin, “Monumental Commemoration,” 118.

61. Hill, Irish public sculpture, 190; and Turpin, “Monumental Commemoration,” 118.

62. Murphy, Art and Architecture of Ireland, 533; and Switzer, Unionists and Great War commemoration, 78–80.

63. Hill, Irish public sculpture, 190.

64. Turpin, “Monumental Commemoration,” 118.

65. Hill, Irish public sculpture, 165.

66. Hall, “The Castlebellingham War Memorial,” 453.

67. See note 8 above.

68. Jeffery, “The Great War,” 148.

69. See note 7 above.

70. Johnson, Geography of Remembrance, 102.

71. Unique footage of unveiling of Longford’s memorial in 1925 is available at https://ifiplayer.ie/longford-memorial/ (June 5 2020).

72. Hill, Irish public sculpture, 165.

73. Moloney, “The Limerick War Memorial,” 121.

74. Leonard, “The Twinge of Memory,” 102-3; and Walker, Irish History Matters, 81-5.

75. Leonard, “Twinge of Memory,” 100; and Walker, Irish History Matters, 84.

76. Jeffery, “The Great War,” 149.

77. Ibid., 152.

78. For an account of the attacks on imperial monuments in Dublin during this period see Whelan, Reinventing Modern Dublin, 207-12.

79. D’Arcy, Remembering the War Dead, 356.

80. See note 73 above.

81. In March 1966, the memorial to Admiral Nelson on Dublin’s O’Connell Street was significantly damaged by a bomb and subsequently demolished.

82. Leonard, “Twinge of Memory,” 107; and Walker, Irish History Matters, 89.

83. Pennell, “A Truly Shared Commemoration?” 92-100; Walker, Irish History Matters, 90-9; and Cherry, “Nowhere to Pay Our Respects,” 189-210.

Bibliography

- Cherry, Jonathan. “Nowhere to Pay Our Respects’: Constructing Memorials for the Irish Dead of World War I in the Republic of Ireland, 2006–2018.” In Places of Memory and Legacies in an Age of Insecurities and Globalization. Key Challenges in Geography, edited by G. O’Reilly, 189–210. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2020.

- D’Arcy, F. A. Remembering the War Dead: British Commonwealth and International War Graves in Ireland since 1914. Dublin: Government Publications, 2007.

- Dolan, A. Commemorating the Irish Civil War, 1923–2000. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Fitzpatrick, D. “Commemoration in the Irish Free State.” In History and Memory in Modern Ireland, edited by I. McBride, 184–203. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Hall, D. “The Castlebellingham War Memorial.” Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society 27, no. 3 (2011): 450–473.

- Heffernan, M. “For Ever England: The Western Front and the Politics of Remembrance in Britain.” Ecumene 2, no. 3 (1995): 293–323. doi:10.1177/147447409500200304.

- Hill, J. Irish Public Sculpture. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 1998.

- Hynes, S. A War Imagined the First World War and English Culture. London: Bodley Head, 1990.

- Inglis, K. S. assisted by Jan Brazier. Sacred Places, War Memorials in the Australian Landscape. Melbourne: University Press, 1998.

- Jacob, F, and K Pearl, eds. War and Memorials the Age of Nationalism and the Great War. Leiden: Brill, 2019.

- Jeffery, K. “The Great War in Modern Irish Memory.” In Men, Women and War, edited by T. G. Fraser and K. Jeffery, 136–155. Dublin: Lilliput Press, 1993.

- Johnson, N. “Cast in Stone: Monuments, Geography and Nationalism.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 13 (1995): 51–65. doi:10.1068/d130051.

- Johnson, N.C. “Sculpting Heroic Histories: Celebrating the Centenary of the 1798 Rebellion in Ireland.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 19, no. 1 (1994): 78–93. doi:10.2307/622447.

- Johnson, N. C. Ireland, the Great War and the Geography of Remembrance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- King, A. Memorials of the Great War in Britain: The Symbolism and Politics of Remembrance. London: Bloomsbury, 1998.

- Lee, P. G. “Memorial Cross at Whitegate.” Journal of the Cork Historical and Archaeological Society 25, no. 121 (1919): 49–50.

- Leonard, J. “Lest We Forget.” In Ireland and the First World War, edited by D. Fitzpatrick, 59–67. Dublin: Trinity History Workshop, 1986.

- Leonard, J. “The Twinge of Memory: Armistice Day and Remembrance Sunday in Dublin since 1919.” In Unionism in Modern Ireland, edited by R. English and G. Walker, 99–114. Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1996.

- Macleod, J. “Memorials and Location: Local versus National Identity and the Scottish National War Memorial.” The Scottish Historical Review 89, no. 1 (2010): 73–95. doi:10.3366/shr.2010.0004.

- Martin, F. X. “1916: Myth, Fact, and Mystery.” Studia Hibernica 7 (1967): 7–126.

- Moloney, T. “The Limerick War Memorial.” North Munster Archaeological Journal 48 (2008): 115–122.

- Moriarty, C. “The Absent Dead and Figurative First World War Memorials.” Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society 39 (1995): 7–40.

- Moriarty, C. “The Material Culture of Great War Remembrance.” Journal of Contemporary History 34 (1999): 653–662.

- Mosse, G.L. Fallen Soldiers Reshaping the Memory of World Wars. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- Murphy, P., ed. Art and Architecture of Ireland Volume III Sculpture 1600-2000. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014.

- Pennell, C. “A Truly Shared Commemoration?” The RUSI (Royal United Services Institute) Journal 159, no. 4 (2014): 92–100.

- Switzer, C. Unionists and Great War Commemoration in the North of Ireland, 1914-1939: People, Places and Politics. Dublin: Irish Academic Press, 2007.

- Taaffe, S. “Commemorating the Fallen: Public Memorials to the Irish Dead of the Great War.” Archaeology Ireland 13, no. 3 (1999): 18–22.

- Turner, S.V. “The Poetics of Permanence? Inscriptions, Memory and Memorials of the First World War in Britain.” Sculpture Journal 24, no. 1 (2015): 73–96. doi:10.3828/sj.2015.24.1.6.

- Turpin, J. “Monumental Commemoration of the Fallen in Ireland, North and South 1920-60.” New Hibernia Review 11, no. 4 (2007): 107–119. doi:10.1353/nhr.2008.0010.

- Van Ypersele, L. “Mourning and Memory 1919-1945.” In In A Companion to World War I, edited by J. Horne, 576–590. Maiden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

- Walker, B. M. Irish History Matters: Politics, Identities and Commemoration. Dublin: The History Press Ireland, 2019.

- Walls, S. “‘Lest We Forget’: The Spatial Dynamics of the Church and Churchyard as Commemorative Spaces for the War Dead in the Twentieth Century.” Mortality 16, no. 2 (2011): 131–144. doi:10.1080/13576275.2011.560481.

- Whelan, Y. Reinventing Modern Dublin: Streetscape, Iconography and the Politics of Identity. Dublin: UCD Press, 2003.

- Wilson, R.J. “Remembering and Forgetting the Great War in New York City.” First World War Studies 3, no. 1 (2012): 87–106. doi:10.1080/19475020.2012.652446.

- Wilson, R.J. Landscapes of the Western Front. London: Routledge, 2012.

- Wingate, J. Sculpting Doughboys, Memory, Gender and Taste in America’s World War I Memorials. London: Routledge, 2013.

- Winter, J. Remembering War: The Great War between Memory and History in the Twentieth Century. London, New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 2006.

- Winter, J. Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.