ABSTRACT

Over the last decades, to promote the study of historical geography, a number of institutions have constructed historical GIS platforms. Correspondingly, a large number of historical studies require more detailed information on historical toponyms, and there is an urgent need for improving and expanding the toponymic information on the existing historical GIS platforms. Therefore, in this paper, we selected Du Shi Fang Yu Ji Yao, one of the most representative books of historical geography, as the data source. We analyzed the geographic information in the book, especially the structure and characteristics of the toponymic information, according to the particularities of administrative regions in the Ming Dynasty, and designed a spatio-temporal data model for both administrative and non-administrative region toponyms. The both types of toponyms are used to construct an information database on more than 60,000 toponyms in Essence of the Geographical Content of the History Books that provides a convenient destination for inquiries by containing more abundant and precise toponymic information of the Ming Dynasty, and develop a toponymic information management system of the Essence of the Geographical Content of the History Books, in which the toponymys can be rapidly extracted, separated and used to establish relationships between them.

1. Introduction

Over the last decades, the scholars from Fudan University, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the Academia Sinica of Taiwan district, and many other historical geography research institutions have established some historical GIS systems such as the China Historical Geographic Information System, the Chinese Civilization in Time and Space (CCTS), the Chinese Social Science Integrated Geographic Information Service Platform and the History of the GIS Platform. In the CCTS, The Historical Atlas of China (Tan Citation1982) edited by Tan Qixiang was used as the original historical toponymic data source (Liao and Fan Citation2012), which provides a number of representative years’ basic geographic data for historical research. Other historical GIS platforms also use the book as an important reference. On above historical GIS platforms, a variety of thematic maps can be generated to promote further analysis. In these platforms, toponym is one of the most important information elements. Among the existing documents, the toponymic data in The Historical Atlas of China are considered as the most authoritative. However, the toponyms in The Historical Atlas of China are mostly administrative region toponyms, the most detailed level of that is Xian (county) toponym, and there are few non-administrative region toponyms. In fact, there are always huge demands for more sophisticated non-administrative region toponyms, to examine the evolutionary rules of toponyms (Wang Citation2008), to analyse the changes of land use (Wang Citation1992; Lv, Zhang, and Yang Citation2010), to glean historical and cultural values (Situ Citation1992; Yan Citation1998; Sun Citation2004; Ji Citation2010; Zhou Citation2013; Zhang et al. Citation2016), to develop tourism value (Feng and Han Citation2009; Hu Citation2006) and to achieve other goals based on toponyms (Zhang et al. Citation2012; Yang et al. Citation2009). Therefore, there are urgent requirements to improve and expand the toponymic data, especially non-administrative region toponyms. Historical non-administrative region toponyms have attracted increasing attention, but the non-administrative region toponyms data now available are very limited (Yin Citation1989; Zhang, Wang, and Gao Citation2005).

Du Shi Fang Yu Ji Yao (Essence of the Geographical Content of the History Books, hereinafter referred to as Geographical Essence) is a geographic monograph of the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, that was written by Gu Zuyu. This book is a treasure of historical toponyms, while most toponyms in it are about non-administrative region and are not recorded in official historical documents. Because the author not only referenced many books, but also corrected many errors in other documents, the book has a high quality in accuracy; it even exceeded that of The Travels of Xu Xiake (Citation2015) by Xu Xiake (a famous traveller in Ming Dynasty; the toponyms in his book are considered very accurate). Therefore, the book has been a necessary tool for the study of historical toponyms. For its high reliability and accurate location, it can be an excellent data source to construct a toponymic database of the Ming Dynasty.

Scholars have explored different methods of data organization (Gong Citation1997; Yin and Li Citation2005; He et al. Citation2013; Du, et al., Citation2016). Time and administrative division are key factors in the organization of historical toponyms. The concept of a unified spatio-temporal framework takes a specific date and time as the reference time, historical administrative divisions and ancient and modern toponyms as the reference space, and different modes of expression of the time gauge conversion and of ancient toponym mapping rules to realize the unification of the spatial and temporal information expression (Hu et al. Citation2010; Wen et al. Citation2010; Chen et al. Citation2011). On the basis of the spatio-temporal framework, the expression method of Chinese toponym spatio-temporal information, including precise expression and fuzzy expression, and the transformation between different spatial relations have also been researched (Liang., Zhang, and Fan Citation2010).

Based on the content, style and toponymic information characters of Geographical Essence, according to the particularities of the administrative region system of the Ming Dynasty, and on the basis concept of the former unified spatio-temporal framework, this paper designs a spatio-temporal data model including administrative region toponyms and non-administrative region toponyms, also including military system toponyms, and develops an information system named Geographical Essence Toponymic Information Management System, which stores more than 60,000 toponyms in the book. It further enriches the historical toponymic data, provides precise toponymic information on the Ming Dynasty, realizes the fast and convenient query and supports further collection of historical data for history researchers.

2. Analysis of toponymic information in Geographical Essence

2.1. Information and organization of toponyms in Geographical Essence

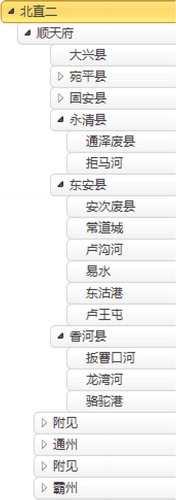

Based on the administrative region in late Ming Dynasty, Geographical Essence narrated and researched the evolution of toponyms from the Shang Dynasty to the late Ming and early Qing Dynasties, providing systemic and comprehensive information on toponyms. In addition, as Liang Qichao (Leung Kai Chiu) said, the structure and the research methods of the book are the best model for geographical study (Liang Citation2004; Shi Citation1997). Geographical Essence, with as many as 130 volumes, according to the characters of its contents, can be divided into three parts. The first part, from the 1st to 9th volumes, is the summary of the book, summing up the evolution of every province and the development of important cities, and illustrating the military status of each province. The second part is from the 10th to 123th volumes, which are the main contents of the book. In this part, the highest administrative divisions in the Ming Dynasty – the 2 capitals and 13 provinces (commonly known as the 15 provinces) – are the key link. In accordance with the administrative divisions in the order from high to low, their location, range and evolution, non-administrative region toponyms in them, such as mountains, rivers, towns, passes and historic sites are all illustrated, and the population in them, relevant historical events and other information are also indicated. The names of Fu (府, prefectural region), Zhou (州, sub-prefectural region) and Xian (县, county) and the description of geographical features of the regions under their jurisdiction, Fu, Zhou or Xian, are distinguished by different text formats. At the end of each province volume, there is content as an appendix that describes various military garrisons of the province and the so-called ‘foreign’ toponyms (the districts that are not within the jurisdiction of the Ming Dynasty are all called foreign), and through different formats of text it marks the differences between the different type toponyms. The third part is from the 124th to 130th volumes. The main form of this part is the table. It introduces the origins of and places passed through by important rivers, the grades of administrative divisions and evolution, status, taxes and areas of administrative regions. The content in this part can be used to verify the relevant information in the second part. Each part has its own focus and is associated with the others. The style of writing makes the book have rich content. The text also has additional notes and annotations. For its clear logic, well-organized content and unique writing style, this book was considered as a long research paper (Liang Citation2004). Although the first part is very important for its contents, from the view of the characteristics of the toponyms, the second part is the main content in the book; it provides both administrative and non-administrative region toponyms, especially the latter. Although administrative region toponyms are very important, they are also recorded in other historical documents and are well known to scholars. The toponyms in the third part are also recorded in the second part. Therefore, the second part constitutes the core contents of this book, and the toponymic information management system constructed in this paper is mainly based on the toponyms in the second part.

2.2. Characteristics of toponyms in Geographical Essence

2.2.1. Administrative region toponyms as the core record

As mentioned above, administrative region names play key role in the Geographical Essence, so the toponyms are arranged in accordance with the level of administrative regions. The non-administrative region toponyms are narrated according to a certain order, using the centres of the administrative regions that they were under the jurisdiction as the reference points. For both administrative and non-administrative regions, all toponyms are marked with the administrative centre of the location relationship. Fu and Zhili Zhou (直隶州, sub-prefectures directly under the jurisdiction of a province, whose level is the same as that of Fu), the highest administrative divisions of a province, are located in a relative positioning method, and the directions and distances between themselves and other administrative centres of Fu or Zhili Zhou are recorded.

2.2.2. Administrative and non-administrative regions toponyms recorded separately

The administrative and non-administrative region toponyms are recorded separately. In recording the administrative region toponyms, only their evolutions are included, the non-administrative region toponyms within their jurisdictions are not recorded. All non-administrative region toponyms in the following part are recorded in accordance with the order of cultural places, mountains, rivers, passes, etc.

2.2.3. Non-administrative region toponyms recorded as relative location relationship

Because the administrative region is used as key index, the locations of all non-administrative region are recorded with the relative location to the administrative regions, and the range of large geographic entities are also recorded by the direction and distance between themselves and their related administrative regions. In this way, the non-administrative region toponyms in each administrative region will be clearly stated. So, some toponyms are included in different administrative regions, and the geographical entities such as large mountains, rivers, lakes and seas are recorded in different administrative regions several times. To understand the whole situation of a larger geographical entity, all records regarding it should be put together.

2.2.4. Using several administrative centres as positioning references

The method of locating a toponym is usually based on several administrative region centres as references, indicating the directions and distances of the toponym from the centres of the administrative regions to itself. Fu and Zhili Zhou are described by the distances away from the nearby same-level administrative region centres, the Zhou and the Xian take the seat of administrative regions that have jurisdiction over them as the reference points, indicating the directions and distances from the nearby administrative centres, and in most cases, several administrative centres are used as reference points. However, in practical writing, the toponyms of a few Xian are marked with the direction and distance from the superior administrative region, and they are not located with the directions and distances from their adjacent area. For example, the location of Baoding Fu (保定府) in Beizhili (北直隶, a region directly under the jurisdiction of the central authorities, equal to one province) is only described as 40 Li or 12 miles (1 Li = 0.31 miles) south of Ba Zhou (霸州), and Chenliu Xian (陈留县) in Henan Province (河南省), is described as 50 Li or 15.5 miles east of Kaifeng Fu (开封府). Although these cases are very rare, they show that the record formats of location are not unified.

The method of locating a non-administrative region toponym is as same as that of the Zhou and Xian; the directions and distances from the administrative region centres are given. But there are some cases that are not located in this way. Some toponyms are recorded only their direction; especially in the descriptions of rivers, the records are the most irregular: some of sources or the places a river flows throw are recorded, and some are not; some of the next places a river flows or its mouth are recorded, and some are not.

2.2.5. The distance description and its precision

Generally, in the book, all distances are accurate to ‘Li’. For example, Anxi Xian (安溪县) in Quanzhou Fu (泉州府) is recorded as 500 Li or 155 miles west of the Fu, 230 Li or 71 miles southwest of Zhangzhou Fu (泉州府), 240 Li or 75 miles northwest of Zhangping Xian (漳平县) of Zhangzhou Fu(漳州府) and 100 Li or 31 miles northeast of Yongchun Xian (永春县). However, there are several distances that are not precise to this degree. For example, for Hui’an Xian (惠安县) of Fujian Province (福建省), the record of the location in the text is as follows: 50 Li or 15.5 miles northeast of Quanzhou Fu, more than 100 Li or 31 miles northwest of Xianyou Xian (仙游县). The distance from Guishun Zhou (归顺州) to Zhen’an Fu (镇安府) is more than 100 Li or 31 miles to the northeast, and there are also other examples of this degree of accuracy. The statement of more than some Li or miles cannot be used for locating directly in subsequent work.

In general, the distance accuracy of toponym records in the book is to the Li mostly, but there are a few cases that cannot reach this level of accuracy.

2.3. Characteristics of administrative divisions in the Ming Dynasty

The government of Ming Dynasty learned the division of administrative regions from the Song Dynasty, and, by reforming its unreasonable ways, achieved a perfect structure of administrative regions. The rulers of the successor Qing Dynasty thought that the Ming Dynasty’s treatment was better than that of the Tang and Song Dynasties. The government power was divided into three parts during the Ming Dynasty, they are Bu-Zheng-Shi-Si (布政使司, administrative commissioner’s office), Du-Zhi-Hui-Shi-Si (都指挥使司, chief military commissioner’s office) and An-Cha-Shi-Si (按察使司, supervisory agency), possessing the administrative, military and supervisory powers, respectively. As a supervisory agency, An-Cha-Shi-Si has no administrative power. So the administrative powers in Ming Dynasty are mastered by Bu-Zheng-Shi-Si and Du-Zhi-Hui-Shi-Si.

The Bu-Zheng-Shi-Si, Fu, Zhou and Xian which constitute a hierarchical administrative structure, are formal administrative division systems of the Ming Dynasty. The normal levels from high to low under Bu-Zheng-Shi-Si are Fu, Zhou and Xian, but some of Fu directly governed the Xian, some of the Zhou had no Xian below and some of the Zhou might also be directly affiliated to the Bu-Zheng-Shi-Si. Therefore, in the administrative division system of the Ming Dynasty, there are four forms in administrative level: Bu-Zheng-Shi-Si, Fu, Zhou and Xian; Bu-Zheng-Shi-Si, Fu and Xian; Bu-Zheng-Shi-Si, Zhou and Xian; and Bu-Zheng-Shi-Si, Fu and Zhou. This is the main administrative division system of the Ming Dynasty, with the corresponding names of the administrative divisions be called in this paper ordinary administrative divisions, and their names be called administrative region toponyms.

There is another kind of administrative division with military functions, built on the basis of Du-Si (都司, abbreviation of都指挥使司), Wei (卫, generally speaking, it is the subordinate military unit of Du-Si) and Suo (所, generally speaking, it is the subordinate military unit of Wei). These regions’ functions are mainly military management, but they also have administrative functions, and therefore they belong to special military administrative regions (Zhou and Jin Citation2007). This structure of administrative regions is very prominent in the Du-Si, Xing-Du-Si (行都司, local agency of Du-Si), Wei and Suo, which have real regions and are semi-duty region, making them very akin to administrative regions. In this system, the Wu-Jun-Du-Du Fu (五军都督府, the highest military unit of the Ming Dynasty) is the supreme command organization and has jurisdiction over the Liu-Shou-Si (留守司, a military unit located in a characteristic location, its rank is the same as that of the Du-Si), Xing-Du-Si and Du-Si. The third level is Wei (卫) and Qian-Hu-Suo (千户所, Suo that commands more than 1000 soldiers), and the lowest is Bai-Hu-Suo (百户所, Suo that commands more than 100 soldiers). Because of their complex constitutions, the levels are staggered. The toponyms of the military administrative districts are known as military administrative region toponyms, also referred to as military toponyms. The toponyms system of administrative regions and that of military administrative regions are parallel, but the former is more in number and scale than the latter. The specific situation is shown in .

3. The design of the toponyms’ spatio-temporal data model

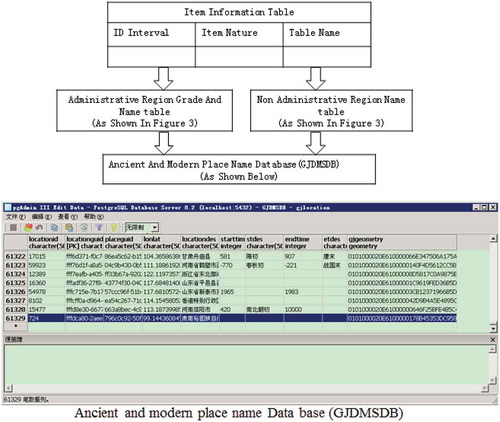

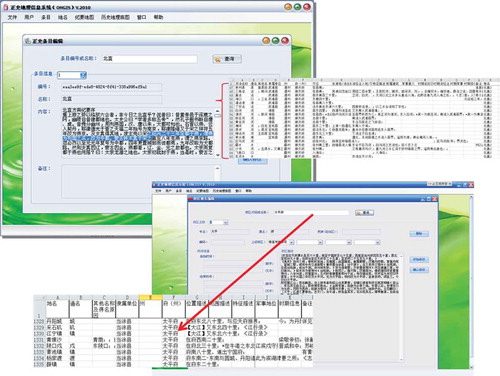

Based on the summary of the features of the Ming Dynasty’s toponyms and the writing characteristics of the Geographical Essence, for the expression of the logical relationship between various toponyms and the effective management of data, this paper designed a data model to meet the needs of most applications. Taking into account the complexity of contents and the need for information storage, management and analysis and the expression of the information system, the data model, which we designed, has two levels. The former is mainly used for classifying the preservation of various different types of toponyms in the text entries, used for the fast retrieval of toponyms (as shown in ), whereas the latter mainly preserves fine-grained split and standardized gazetteer entries, to enable to support further information process, facilitate toponymic information statistical analysis and promote integration with other information and spatial expression of historical data (as shown in ).

The data model consists of administrative region toponyms including ordinary administrative region toponyms and military administrative region toponyms, non-administrative toponyms including mountains, waters, cultural places and the level of military and administrative region; and is a subsidiary of the content, that is, the event, when necessary, used to verify the location of toponyms. The administrative region toponyms have fields including identifier, name, generic name, level, location description, scope description, start time, end time, feature description, period changes, superior administrative region, volume name and remark. The level of military and administrative regions are used to represent the structure of military and administrative regions of the Ming Dynasty, their fields include identifier, name, abbreviation, another name, military or administrative, level, volume name and remarks. The non-administrative region toponyms in Geographical Essence are mainly names of mountains, waters and cultural places, so in the data model, the non-administrative region toponyms are also divided into three types. Among them, the mountain information’s fields include identifier, name, general name, another name, naming reason, subordinate administrative region, period name, location description, scope description, feature description, military value, component, period change, volume name and remarks. The river information’s fields include identifier, name, general name, another name, subordinate administrative region, location, source/place of discharge, flow through/mouth/range, feature description, subsidiary building, military value, period name, period flow through/mouth/range, period military value, period change, volume name and remarks. Cultural place information’s fields include identifier, name, general name, another name, subordinate administrative region, location description, scope description, feature description, military value, period change, volume name and remarks. Event’s fields include identifier, period, toponym, description, volume name and remarks. Among them, the principle to determine the general name references Interpretation of Generic Names of Ancient and Modern Geography in China, by Cui Hengsheng (Cui Citation2003). The period refers to the entire time before the Ming dynasty. Two types of entities, the administrative region and military administration region, can be considered the main characteristics of the Ming Dynasty’s administration and are the frame of the data model. The administrative region toponyms through a hierarchy of attributes and military-grade entities establish the type and level of contact, while superior administrative region describes the hierarchical structure of the internal administrative and military systems. The non-administrative region entities include the toponyms of mountains, waters and cultural places through their respective administrative region attributes, and the administrative units establish subordinate relationships. Connections can be established between events and other entities through name attributes and toponym entities of administrative regions, mountains, waters and cultural places. All of the names found in the contents of Geographical Essence, as far as possible, described the situation for relevant time, location and range of geographic range information.

4. Data acquisition and system framework

4.1. Toponym data acquisition and preprocessing

At present, the best edition of Geographical Essence is revised by He Cijun and Shi Hejin, published in 2005 by the Commercial Press, Beijing, China. This paper used this edition as original source. The work flow to process is as shown in .

The version of Geographical Essence is published in simplified Chinese, which makes it convenient to be digitalized. The writing system of the original Geographical Essence is entire and well organized; we should preserve the features, and so a preliminary processing of the digitalized edition is necessary. In this paper, according to the characteristics of administrative regions of the Ming Dynasty, the four levels for the administrative regions toponyms and one level for non-administrative region toponyms were associated with different header formats in Microsoft Word, as shown in . This step provided a convenient means to distinguish the toponyms of administrative regions and those of non-administrative regions for the next step: the toponyms of administrative regions are all in title format and those of non-administrative regions are all in plain text.

Then, data can be classified into items of administrative regions and non-administrative regions; each item includes the information such as identifier, name and type name. The last task is to construct the toponym database of Geographical Essence. The data of Geographical Essence are divided into two categories: administrative region toponyms and non-administrative region toponyms. Based on this classification, a text data system is designed to process the data with two different methods, as shown in .

When administrative region toponyms are input, the hierarchical relationship between toponyms should be considered carefully. In this paper, the relationships are determined according to the provisions of the hierarchical model shown in . Non-administrative region toponyms have no administrative levels; according their different natures, they are divided into three categories, namely mountains, rivers and cultural places. According scales and degrees of importance, they are divided into three levels, namely national, provincial and common toponyms; some detailed information can be found in our last work (Liu and Hu Citation2014).

4.2. Toponymic information management system framework of Geographical Essence

Geographical Essence takes the Ming Dynasty’s administrative regions as key index to organize the Ming Dynasty’s geographical features. It also traces the changes of administrative regions and the geographical features, including name changes, migration of river courses, important military events and other information. The times in Geographical Essence are mainly expressed by dynasty and the title of an emperor’s reign, but there are some uncertainties in the accuracy: some records are accurate to the year even month, some records only to the reign of an emperor and some just to the dynasty. Location is expressed by the Ming Dynasty’s administrative region as the key reference, but due to the differences in the administrative division systems between the dynasties before the Ming Dynasty and the changes of administrative region toponyms, the administrative division methods of different dynasties are very different, which makes it more difficult to understand. Thus, a unified spatio-temporal framework is designed to support the Toponym Information System of Geographical Essence.

As to the unified spatio-temporal framework, the Christian era date is used as the unified time reference, and the historical administrative divisions and ancient and modern toponyms are used as the unified spatial reference. It supports the transformation between different expression methods of time and mapping rules, between ancient and modern toponyms. In the unified spatio-temporal framework, the toponym expressions have the uniform standards of time and space, making them not only intelligible but also convenient to connect with other databases (Hu et al. Citation2010; Chen et al. Citation2011; Zhang Citation2014).

The toponym database of Geographical Essence and the unified spatio-temporal framework mentioned above together constitute the toponymic information management system of Geographical Essence, which supports the function of maintenance, management, query of toponymic information and cartography by user interaction. The toponymic information system of Geographical Essence adopts a three-layer system structure, including data layer, service layer and application layer, as shown in .

The main functions of the toponymic information management system of Geographical Essence include the following:

Toponym Query Function: Effective organization and maintenance of the toponym data of Geographical Essence support various toponym query methods according to different requirements, including fuzzy queries and precise queries. By administrative region, general name or category, different methods of query can be supported, and different spatial information can be searched.

Toponym Criticism Function: This system takes Geographical Essence as the data source and the accuracy of toponyms is excellent, but there are still some inevitable mistakes. For users to correct errors conveniently, the system provides an error correction procedure. The users who find errors can mark the mistake text and submit his/her evidence. The submitted data will be verified by the staff, be imported into the system and be provided as a reference to other users.

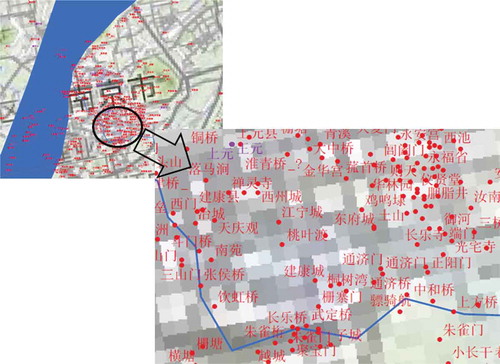

Map Output Function: The toponyms retrieved, in addition to being displayed as basic text, can also be rendered in map mode, and the generated map can be exported. Where the location information is less or not accurate, the location is matched with the modern toponyms. If there is no modern toponym to match, the relative positioning method is adopted for positioning. We use Google Maps as the background map, while referencing the historical maps of The Historical Atlas of China (Tan Citation1982). Readers can choose the type of toponyms and draw the map according to their needs. This function provides a freedom of choice and can generate the required maps more flexibly and quickly. The map example is shown in .

Toponym Management Function: This function enables the import, export, addition, deletion and modification of the toponyms information.

5. Conclusions and expectations

The historical toponym database in The Historical Atlas of China has been unable to meet current research and application needs because its main data are the toponyms of administrative regions above the Xian level, while the toponyms of non-administrative regions are rare. The vast majority of the toponyms in Geographical Essence are non-administrative region toponyms, so they can greatly expand the historical toponymic information. In this paper, the toponyms recorded in Geographical Essence on the Ming Dynasty are taken as the beginning, and based on a full analysis of the data structure of the book and also the features of toponyms in the Ming Dynasty, more than 60,000 toponyms were collected and normalized. A toponymic data model of Geographical Essence was established, the toponymic information management system of Geographical Essence were constructed and a large number of non-administrative region toponyms were imported into the toponym database, so that further study based on these toponyms can begin. In fact, the method used to build the toponym database and management system can be reused to integrate the toponym information in other dynasties. In addition to Geographical Essence, there are many other ancient and contemporary historical gazetteers, such as Shui Jing Zhu (Li et al. Citation1989) (《水经注》, a famous historical book on rivers and toponyms written in Northern Wei Dynasty).

Acknowledgements

The work described in this article was supported by the Ministry of Education Humanities and Social Sciences Research Foundation of China (Grant No. 12YJCZH132) and the open fund of the Lab of Virtual Geographic Environment, Ministry of Education of China (Grant No. 2010VGE03).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Chen, M., H. Lin, G. Lv, L. He, and Y. Wen. 2011. “A Spatial-Temporal Framework for Historical and Cultural Research on China.” Applied Geography 31: 1059–1074. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2011.01.022.

- Cui, H. 2003. Interpretation of Generic Names of Ancient and Modern Geography in China. Hefei, China: Huangshan Press.

- Du, P., Y. Yao, and P. Xu. 2016. “Expression of Spatio-Temporal Information of Place Names in Ontology.” Journal of Lanzhou Jiaotong University 35 (6): 137–140.

- Feng, F., and F. Han. 2009. “Tourism Value of Historical Place Names.” Tourism Manager 22: 367–367.

- Gong, J. 1997. “Object Oriented Spatio Temporal Data Model in GIS.” Acta Geodaetica Et Cartographica Sinica 1997 (4): 289–298.

- He, L., M. Chen, G. Lu, H. Lin, L. Liu, and J. Xu. 2013. “An Approach to Transform Chinese Historical Books into Scenario-Based Historical Maps.” Cartographic Journal 50 (1): 49–65. doi:10.1179/1743277412Y.0000000024.

- Hu, A. 2006. “The Old Place Names are the Historical Cultural Heritage and Modern Tourism Resources for Ancient Capitals.” Shanghai Urban Management 15 (2): 10–13.

- Hu, D., G. Lv, Y. Wen, Y. Feng, M. Chen, and H. Zhang. 2010. “GIS-based Family Tree Information Sharing and Service.” International Conference on Geoinformatics 2 (1): 1–6.

- Ji, L. 2010. “Interpretation of Qilu Culture from Geographical Names in Shandong.” Guanzi Journal 2010 (2): 80–88.

- Li, D., S. Guo, and H. Xiong. 1989. Shui Jing Zhu Shu. Nanjing, China: Phoenix Publishing House:.

- Liang, Q. 2004. Academic History of China in Recent Three Hundred Years. Shi Jia Zhuang, China: Hebei People’s Publishing House.

- Liang., L., X. Zhang, and X. Fan. 2010. “Spatial-Temporal Expression of Chinese Toponym.” Geography and Geo-Information Science 26 (6): 6–10. 23.

- Liao, H., and I. Fan. 2012. “Chinese Civilization in Time and Space: The Design and Application of China Historical Geographic Information System.” e-Science Technology & Application 3 (4): 17–27.

- Liu, L., and D. Hu. 2014. “Principles and Methods of Geographical Names in Construction of Dushi Fangyu Jiyao Database.” Journal of Jiangsu University of Science and Technology(Social Science Edition) 14 (4): 29–34. 60.

- Lv, Y., S. Zhang, and J. Yang. 2010. “Application of Toponymy to the Historical LUCC Research in Northeast China: Taking Zhenlai County of Jilin Province as an Example.” Journal of Geo-Information Science 12 (2): 174–179. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1047.2010.00174.

- Shi, H. 1997. “The Value and Significance of Publishing of Du Shi Fang Yu Ji Yao Manuscript.” Journal of Nanjing Normal University(Social Science Edition) 1997 (1): 136–139.

- Situ, S. 1992. “A Study on the Historical Geography of Guangdong Place Names.” Journal of Chinese Historical Geography 1992 (1): 21–55.

- Sun, D. 2004. “The Change of the Name of the Street and the Historical and Geographical Background in the Area of the Da Zhalan.” Social Science of Beijing 2004 (4): 127–133.

- Tan, Q. 1982. The Historical Atlas of China. Beijing, China: Map Press.

- Wang, X. 1992. “The Place Names of the Hexi Corridor and History on the Wasteland.” Journal of Tianshui Normal University 1992 (1): 35–38.

- Wang, Z. 2008. “Social and Geographical Background for Changes of Historical Place Names: Focusing on Low Hills in the South of Anhui during Ming and Qing Dynasty.” Journal of Shanghai Normal University (Philosophy & Social Science Edition) 37 (3): 58–63.

- Wen, Y., G. Lv, M. Chen, and H. Su. 2010. “Data Organization and System Architecture of Sino-Family-Tree GIS.” Journal of Geo-Information Science 12 (2): 235–241. doi:10.3724/SP.J.1047.2010.00235.

- Xu, X. 2015. Travel of Xu Xiake. Beijing China: Zhonghua Book Company.

- Yan, Z. 1998. “Analysis of the Role of Place Names.” China Place Name 9 (1): 42.

- Yang, L., G. Lin, A. Chen, Y. Chen, and X. Wen 2009. A Spatio-Temporal Data Model for Administrative Division Place Names: A Case Study of Xiamen. Symposium of the International Society for Digital Earth (ISDE).

- Yin, J. 1989. “A Study of the Place Names on the Status of Historical Place Names – A Case Study of Beijing.” Social Science of Beijing 1989 (1): 85–92.

- Yin, Z., and L. Li. 2005. “Research on Spatial-Temporal Data Model in GIS.” Science of Surveying and Mapping 30 (3): 12–14.

- Zhang, B., R. Wang, and L. Gao. 2005. “A Spatial - Temporal Data Model for the Place Name.” Remote Sensing For Land & Resources 66 (4): 82–85.

- Zhang, H. 2014. Research on the Organization of Historical Geographic Name Data in Geodatabase. Northeast Normal University. Master degree thesis (unpublished).

- Zhang, P., H. Lin, N. Chitty, and K. Cao. 2016. “Beijing Temples and Their Social Matrix - A GIS Reconstruction of the 1912-1937 Social Scope.” Annals of GIS 22 (2): 129–140. doi:10.1080/19475683.2016.1158735.

- Zhang, P., D. W. Wong, B. So, and H. Lin. 2012. “An Exploratory Spatial Analysis of Western Medical Services in Republican Beijing.” Applied Geography 32 2: 556–565. 19. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2011.07.003.

- Zhou, Z. 2013. “Historical Geography of Communication Reflected by Place Names.” Cultural Geography 2013 (7): 12–12.

- Zhou, Z., and R. Jin. 2007. The General History of Chinese Administrative Divisions, Ming Dynasty Volume. Shanghai, China: Fudan University Press.