ABSTRACT

Collectively representing a super large-scale settlement space, the Great Wall’s military settlements have a long history and cover a large area, and are thus associated with a huge amount of information. Based on spatial analysis of data gathered on the Great Wall military settlements in the Ming Dynasty, this paper fills the gap in quantitative research on the Great Wall, establishes a specific connection between the spatial and environmental characteristics of Ji Town’s military settlements, and enhances understanding of their spatial distribution and historical development. The paper also provides more effective data-based support and management tools for research on and conservation of the Great Wall and its military settlements through quantitative analysis of the Ji Town settlements, their surrounding landscape, and other factors. The concept of a Great Wall military buffer zone is proposed as an important bridge between the design of zoning policies for the Great Wall’s preservation and the overall conservation of its heritage value.

1. Significance of spatial analysis of Great Wall military settlements

The Great Wall’s defense system and its military settlements have a long and complex history and cover a large area across regions, and are thus associated with a huge amount of information. The traditional research methods for the Great Wall and military settlements include typological and regional studies. The typological studies are conducted separately for the Great Wall’s wall itself, some important passes such as Shanhaiguan pass, the Great Wall’s brick kiln, and other types. The regional studies have obvious sectional characteristics. Researchers from different regions tend to focus only on the walls and important settlements of the Great Wall in the local sections. For example, the studies on the Great Wall in Ji Town mainly focus on Beijing, Tianjin, Tangshan, Qinhuangdao region instead of covering the whole ‘Ji Town Great Wall Defense System’ across multiple current administrative regions.Consequently, the traditional methods of settlement research are difficult to meet the needs of research and application. Using spatial information technology, a large amount of historical and spatial data and resources can be digitized and integrated under a single framework to provide a powerful analytical tool for settlement research. This would enable analysis of the relationship between the distribution of regional settlements over a large area and the characteristics of their surrounding landscape. The tool can be used to deal comprehensively with a range of data and integrate management with dynamic access to provide more effective data-based support for quantitative research on the Great Wall.

In this paper, spatial information technology is used to conduct large-scale analysis of the Ming Dynasty military settlements on the Great Wall’s Ji Town border. This aims to compensate for the current lack of quantitative analysis in the Greatwall military settlements as a large-scale heritage research and conservation. The basic research of Ji Town defense system and military settlements needs to be further deepened, and it is necessary to integrate a variety of research perspectives and multidisciplinary approach to form a more comprehensive understanding of Ji Town military settlements, and then to understand the Great Wall’s defense system as a whole.

2. Acquisition and integration of spatial data on Ji Town military settlements

2.1 Survey of Ji Town military settlements

2.1.1. Historical and spatial characteristics of Ji Town military settlements

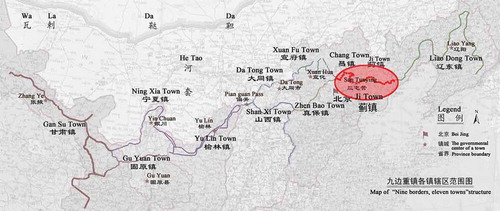

The formation of the northern frontier of the Great Wall and the establishment of a defense system for the wall occurred gradually over time, strongly influenced by rulers’ defensive strategies and the structure of the frontier in the Ming Dynasty. The composition of the northern frontier shifted from ‘nine borders, nine towns’ to ‘nine borders, eleven towns’ during the Ming Dynasty, and Ji Town’s defense range was adjusted accordingly. As part of the Great Wall’s defense system, Ji Town formed an east-to-west line of defense against tribes in the north, such as the Tatar(拓跋), Wala(瓦剌), and Wu Liangha (兀良哈)().

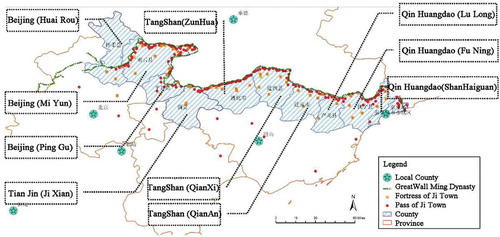

Figure 1. Ji Town in frontier of ‘nine borders, eleven towns’(‘九边十一镇’)structure (Li Citation2007).

The spatial range of Ji Town’s military settlements determined the area of defense provided by the town for the Great Wall in the Ming Dynasty. According to historical books such as Four Towns Three Passes History (Liu Citation1574-1576), Ming History (Zhang et al. Citation1739), and Imperial Ming Nine Borders History (Wei Citation1541), the Ji Town military settlements developed considerably during the Hongwu (1368–1398) years of the Ming Dynasty, followed by large-scale construction in several areas in the Yongle (1403–1424) and Jiajing (1522–1566) periods. By the Wanli era, Ji Town’s defense had been divided into a more stable pattern comprising the following 12 smaller defensive units ‘‘Lu’ from east to west: Shanhai Lu(山海路), Shimen Lu(石门路), Taitou Lu(台头路), Yanhe Lu(燕河路), Taiping Lu(太平路), Xifeng Lu(喜峰路), Songpeng Lu(松棚路), Malan Lu(马兰路), Caojiazhai Lu(曹家寨路), Qiangzi Lu(墙子路), Gubei Lu(古北路), and Shitang Lu(石塘路). The majority of the Ji Town military settlements were located to the south of the Great Wall, and their spatial range covered the following administrative areas: Shanhaiguan District in Funing County and Lulong County (Qinhuangdao Prefecture); Qian’an County, Qianxi County, and Zunhua City (Tangshan Prefecture); Jixian County (Tianjin Prefecture); Pinggu County, Miyun County, and Huairou County (Beijing Prefecture); and other regions ().

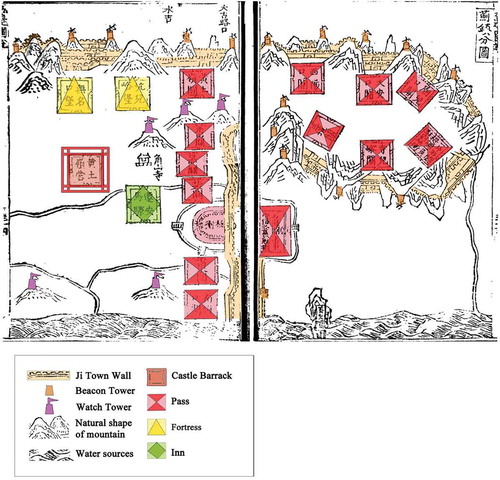

2.1.2. Composition of Ji Town military defense system based on ancient literature

Ancient texts and maps such as Four Towns Three Passes History (Liu Citation1574-1576), Nine Borders History Map (Huo Citation1569), and Defense History of Lulong Border (Guo Citation1610) contain abundant historical information on the Great Wall’s military settlements. The ancient composition of the Great Wall defense system can be inferred from the section of the Nine Borders History Map shown in , which displays the components of the Great Wall’s Ji Town border, including the wall itself (边墙) and its beacon towers (烽火台), watch towers (敌台), castle barracks (营城堡), passes (关隘), fortresses (堡寨), inns (驿站), and other military fortifications (), as well as the natural shape of the mountain and water sources. The Great Wall defense system combines both artificial and natural defense engineering.

Table 1. Composition of Ji Town border (Liu Citation1574-1576).

Figure 3. Composition of Ji Town defense system (Huo Citation1569).

2.2 Integration of spatial and historical information on Ji Town settlements

Traditional historical research on the Great Wall based on historical, geographical, and settlement-related data has often lacked quantitative support or used inconsistent descriptive methods, creating a bottleneck in traditional research in this field. The use of spatial information helps to overcome this limitation. In this paper, spatial data are drawn from numerous historical texts and other records from the Ming and Qing dynasties, such as Defense History of Lulong Border (Guo Citation1610), Imperial Ming Nine Borders History (Wei Citation1541), and Yongping State History (Song Citation1711), which provide a wealth of basic information on the Great Wall’s settlements, from their date of construction and structural evolution to the military officers and troops stationed at each settlement, the populations of these areas, and the amounts of grain stored in each. Defense History of Lulong Border (Guo Citation1610) records,

(Nan Haikou pass) southeast brick wall of the castle is two zhang and eight chi high, northwest soil wall of the castle is one zhang and five chi high, the perimeter is one hundred and thirteen zhang, the gate is located on the South wall, 16 military families are living in the castle.

Data on settlement characteristics gathered under a single framework from both field investigation and historical records are processed and coded. Meanwhile, spatial information is obtained from up-to-date national geographical data, digital elevation maps, and maps of historical and current administrative divisions, along with field research on the settlements’ Global Positioning System coordinates, and used to establish a spatial database on the Ji Town military settlements.

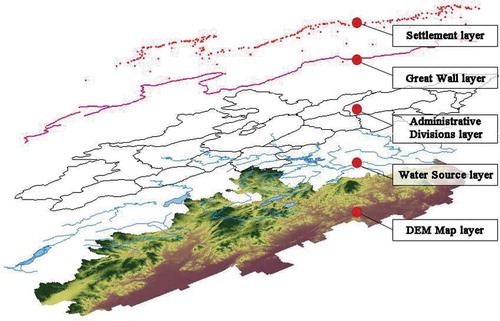

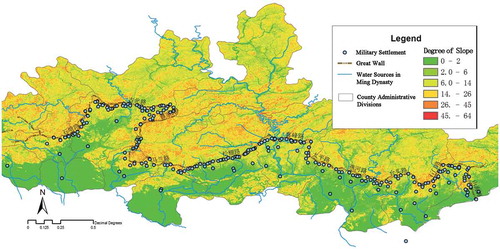

The Geographic Information System (GIS)-based Ji Town Great Wall military settlement spatial database reported in this paper is composed of various superposed layers showing the shape of the Great Wall’s border, the distribution of its military settlements, the current county-level administrative divisions, details of the river system, and other basic geographic data and spatial information from digital elevation maps and other sources (). The integration of these various elements in the Ji Town military settlement database greatly increases the efficiency of resource management, enabling the comparative analysis of multiple sources and types of data.

3. Spatial analysis of environment of Ji Town military settlements

3.1 Influence of topographical features on location of Great Wall military settlements

3.1.1. Terrain slope analysis

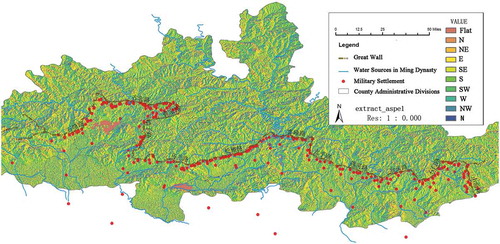

The aforementioned spatial database is used to analyze the slope distribution of the Ji Town military settlements. Site planning is distinguished by slope level into six categories (Architectural Design Citation1994): flat slope, gentle slope, mid-level slope, steep slope, hard slope, and cliff slope.Footnote1 Slope information is extracted from the digital-elevation map of the thistle-town area and classified to obtain the slope gradient in the area of the Ji Town military settlements (). The statistics provide both a classification of terrain slope and details of the historical Lu in the Ji Town military settlements ().

Table 2. Slope level and historical Lu in Ji Town military settlements.

Figure 5. Map of Ji Town settlements: slope classification. (SRTM data are from the Chinese Academy of Sciences Computer Network Information Center’s International Scientific Data Mirror site, SRTM 90 m’ resolution.)

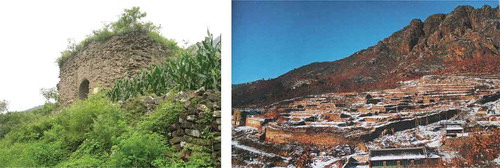

Of the 286 military settlements under analysis, 21% were located on flat slopes, 24% on gentle slopes, 30% on mid-level slopes, 20% on steep slopes, and about 5% on hard slopes. No settlements were located on slopes with a cliff gradient. Notably, the settlements on middle, steep, and hard slopes accounted for 55% of the total, showing that most of the military settlements were located on terrain best suited to defense. As the construction of settlements on such terrain would have incurred much higher material, financial, and manpower costs, defense is the only viable reason for their location. It is also necessary to carefully consider the military settlements constructed on steeply sloping terrain. For example, the Ji Town settlement database reveals that the slope value for Damaoshan Fortress, which belongs to Shimen Lu, is 16. Therefore, the fortress belongs to the ‘steep slope’ category. A site plan of the ruins of Damaoshan Fortress () shows a stepwise pattern higher in the north and lower in the south; the buildings in this area are located at different heights, with the fortress’s main street directed north.

Figure 6. Photograph of Damaoshan Fortress.

Left: Entrance to Damaoshan Fortress (Source: Photo by Author 2010). Right: Bird’s-eye view of Damaoshan Fortress (Source: Photo by Li Zhanyi Citation2005).

In terms of settlement type, most of the castles categorized by county or ruler rather than by Lu were built on flat slopes; examples include Zunhua County Seat, Jizhou Castle, Funing County Seat, and Yingzhouzhong Wei Castle. Only Yongping County Seat was built on a gentle slope. The Ying castles in each Lu are located on flat, gentle, and mid-level terrain, not on slopes characterized as steep or hard. The settlement statistics shown in the table indicate that Ying Castle, Wei Castle, and County Seats made up 63% of the castles on flat slopes, indicating that castles housing large troops or serving administrative government purposes were often built on relatively gentle slopes in open areas to meet the needs of troops, garrisons, and defense.

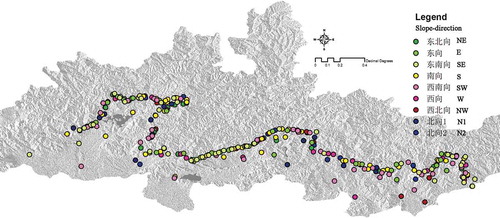

3.1.2. Terrain slope-direction analysis

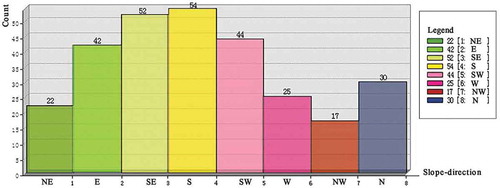

Slope direction affects light level, extent of vegetation, wind direction, and so on. Therefore, slope-direction analysis is of great significance to the study of settlement environments and locations. Based on the terrain slopes defined in the Ji Town military settlement spatial database, a GIS surface analysis tool is used to extract information on slope direction in the town’s military settlements (). Next, the slope-direction data for Ji Town are classified, yielding eight direction categories: north, northeast, east, southeast, south, southwest, west, and northwest. Accordingly, slope direction in Ji Town’s military settlements in a distribution map and histogram is shown in and , respectively.

In general, settlements intended as living spaces were built in areas with access to maximum sunlight and with an appropriate slope gradient, such as slopes in the east, southeast, southern, southwestern, and west categories. According to statistics on the distribution of the settlements’ slope direction, overall, 217 (75.9%) of Ji Town’s 286 military settlements were located in areas falling into the aforementioned five slope-direction categories. Only 69 settlements were located in the other three slope categories, accounting for 24.1% of the total number of settlements. Slope direction was not regular in the Ji Town settlements; military settlements were distributed in every slope-direction category. In contrast with the Caojia Lu settlements in the territory of Beijing Miyun, which show a fairly consistent slope direction, the Ji Town settlements followed the line of the Great Wall. The Great Wall in this section curved first to the east, then to the north, and finally to the west, as confirmed in the literature. In the Ji Town settlements, slope direction was determined by not only the natural orientation of the slope but also the requirements of defense. GIS slope-direction analysis of the integrated statistical data and literature records explains the reason of the location facing the builders of military settlements along the Great Wall.

3.2 Influence of water availability on positioning of military settlements

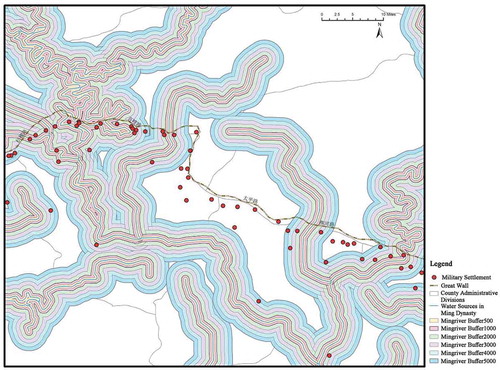

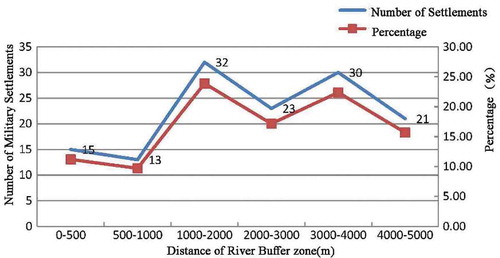

Dependence on the natural environment determined the spatial relationship between ancient settlements and sources of water. Yet, how was the relationship between water source and settlement location affected by the specific historical and political context of the Ming Dynasty Great Wall and the residential purpose of the settlements? The Ji Town Great Wall military settlements spatial database reported in this paper can be used to carry out holistic spatial analysis of the settlements’ water environment and judge the relationship between the spatial distribution of a settlement and its distance from nearby rivers according to the regional range of the river buffer zone. The category of ‘Ming Dynasty Rivers’ in the database is based on the rivers shown in the 1:1,500,000 map of Ming Dynasty capital cities in the book Chinese Cultural Relics Atlas (NCRB Citation2013) and the five levels of river movement provided by the National Basic Geographic Information Center. A buffer zone of 500–5000 mFootnote2 is established on the basis of a given river’s center line, and settlements falling into the buffer zone are considered to be distributed within a specific distance of the river, allowing a spatial association to be established between the river buffer zone and settlement distribution ().

The number of settlements and their distance from nearby rivers can be found in the statistics on the settlements for each river buffer area (). Overall, 15 settlements were located in the river buffer area of 0–500 m; 13 in the river buffer area of 500–1000 m, 32 in the river buffer area of 1000–2000 m, 23 in the river buffer area of 2000–3000 m, 30 in the river buffer area of 3000–4000 m, and 21 in the river buffer area of 4000–5000 m. Two peaks in the number of settlements appear in the river buffer zones exceeding 1000 and 3000 m, respectively. A trough in the number of settlements appears in the river buffer zone of 500–1000 m. Only 134 (46.85%) of the settlements were located in the buffer zone measuring 5 km. According to previous scholars, the maximum distance between an ancient residential site and a source of drinking water is 600 m. However, 106 (79%) of Ji Town’s military settlements were more than 1000 m from water, and 134 settlements were within 5000 m of water. Evidently, therefore, the relationship between these military settlements and nearby rivers cannot be explained in terms of the dependence of ordinary ancient settlements on river water; indeed, the relationship between the Great Wall’s military settlements and local rivers was not close. The reasons for this finding are detailed as follows.

3.2.1. Well-related factors

Field research on Ji Town’s settlements reveals that the settlements around or within the fortress boundaries use well, and most had two or more. For example, an ancient well was located outside the entrance to Dongjiakou Fort, and during the Ming Dynasty, Tao Linkou Fort in Lulong had an ancient well in Hanmen Street. Indeed, these wells continue to provide water for residents to date ( and ). This greatly reduced the dependence of local military settlements on river water, allowing the Ji Town settlements to be built far from rivers.

3.2.2. River-related factors

As the rivers shown in the database were large, they carried a huge amount of water and were significantly subject to tidal movement. Therefore, settlements had to be located at a safe distance from the rivers. The number of settlements located within the 1000-m buffer zone accounted for only 9.79% of the total, while those located within the buffer zone of 2000–3000 m accounted for 19.23% of the total. The latter figure is more than twice the former, despite covering the same range (1000 m), indicating that long-term stability of troops, garrisons, and consequently the military settlements themselves was felt to be put at risk by proximity to the large rivers. The military settlements were thus positioned near rivers but not immediately adjacent to them.

3.2.3. Military defense factors

The defensive roles of mountain and water systems reinforced each other but were often mutually exclusive: advantages were provided by the mountains but not the water, or vice versa. For example, settlements in high mountains were easy to defend but lacked water, while floodland provided a flat terrain suitable for living but was not conducive to defense (Li Citation2007). As the Ji Town settlements were built mainly for defensive purposes, the main consideration in establishing their location was the superiority of the garrisons guarding the main road. This is another way in which military settlements differed from general residential settlements.

3.2.4. Data factors

Due to the limited accuracy of historical maps in describing water levels, the region shown might have contained more rivers than depicted in the figure. As settlements are likely to have been built along small rivers not contained within the established river buffer zone, the database must be further updated and refined to accommodate these settlement locations.

4. Military settlement buffer zone and great wall protection

4.1 Protection zone and buffer zone

The primary task in protecting the Great Wall is to identify appropriate elements of a Great Wall defense system. In 2006, the Chinese government promulgated The Great Wall Protection Ordinance (C.2006), in which the Great Wall was defined as including a frontier wall, military settlements, fortress passes, beacons, lookout towers, etc. The Great Wall is a complex system comprising these elements. As the military settlements along the main wall represent an important component of the Great Wall defense system, analyzing their spatial relationships is a fundamental task for those seeking to protect the wall. To facilitate both protection and management, a protection zone must be delineated for the Great Wall; however, local governments differ in their approaches to this task and the scope of the zone proposed. It is difficult to delineate a Great Wall protection zone, first because the composition of the Great Wall remains unclear and the Great Wall defense system requiring protection is large and complex, and second because the relationships between the Great Wall, its settlements, and the local environment are complex and difficult to quantify.

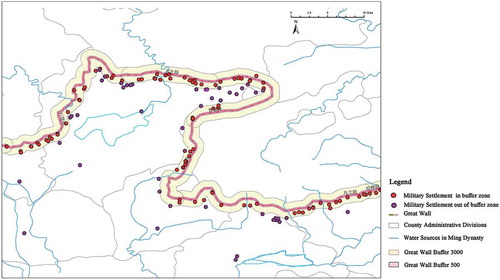

In 2003, the local government announced the Beijing Great Wall Protection and Management Measures (Beijing Citation2003.), which provided for a 500-m non-construction area and a 500–3000-m limited construction area ‘on both sides of the Great Wall’ for temporary protection. However, buffer analysis based on the Ji Town military settlement spatial database reveals that these protected zones cannot provide overall protection for the Great Wall. GIS technology was used to model two buffer zones extending 500 and 3000 m, respectively, from the side of the Great Wall (). The statistics show that of the 286 settlements under study, 17 fall within the 500-m buffer zone, accounting for 5.9% of the total, while 187 fall within the 3000-m buffer zone, accounting for 65.4% of the total. Clearly, the 500 m allotted by the government as a non-construction area cannot provide comprehensive protection for the Great Wall; even the 3000-m restricted construction area fails to accommodate all of the Great Wall’s military settlements. Therefore, the government’s delineation of these two zones still provides only for the protection of the wall itself. However it would not be more efficient to establish a wider range of protection zones to cover the various elements of the Great Wall defense system. So it needs a different approach.

Statistics on the distribution of the Great Wall’s military settlements indicate that components of the wall’s defense system are mostly inside the Great Wall except very few relevant fortifications, such as outside wall-beacon tower and pass, so the scope of the mandated protection for the Great Wall should be uneven. Therefore, the phrase ‘on both sides of the Great Wall’ should not be used as a simple summary; the two sides of the Great Wall’s side wall should be treated differently depending on specific circumstances.

4.2 Great Wall military buffer zone

The historical functions of several elements of the Great Wall were closely related and mutually supportive. Protecting the Great Wall thus involves not just protecting the physical remains of the wall but also preserving its historical value as an important frontier defense area. There is an important connection between the value of the Great Wall and its various elements today and that of the wall’s military buffer zone, given the historical significance of the Great Wall defense system and the spatial relations between various types of fortifications.

The protection area designated for the Great Wall should be based on not only recently discovered remains of the wall, with regional differences in methods of protection, but also the findings of research on the historical Great Wall defense system. First, the historical range of the Great Wall’s military buffer zone should be precisely determined to facilitate classification and delineation. From the Great Wall to the fort, the boundaries of the Great Wall can be used to mark off a comprehensive protection area; away from the Great Wall, military settlements can be targeted for the delineation of independent protection zones. Based on investigation of the Great Wall military buffer zone and using the Great Wall military settlement spatial database, the author explores the historical function and structure of the Great Wall’s defense system within the whole system, and carries out specific protection area planning based on analysis of the data set on the surrounding environment. The protection zone delineated for the Great Wall is no longer merely a general extension of protection but specifically tailored to the Great Wall, taking into account the components of its historical military defense system, its historical function, and its environmental impact to more effectively protect the integrity and value of the Great Wall.

5. Conclusion

Using spatial-analysis technology and a spatial database on Ji Town’s military settlements, this study integrates analysis of local settlement distribution, terrain characteristics, and the influence of the environment (specifically water sources) on settlement location, and provides more obvious insights into the spatial characteristics and distribution of Ji Town’s military settlements. The rich spatial database also enables investigation of the military settlements’ density of defense, distribution distance, level of development, and scale relationships. The informationization of historical data facilitates a comprehensive interpretation of Ji Town, which represents both a historical phenomenon and a cultural landscape. In addition, further in-depth quantitative analysis is carried out to verify the results obtained with the historical data. This process is also a means of exploring the design, modeling, and use of spatial databases for large-scale settlements and providing more rational and technical support for large-scale regional historical and cultural resources management, research, and protection work.

The Great Wall has been on the list of World Heritage Sites since 1987. Those seeking to protect cultural heritage are paying more and more attention to the Great Wall’s heritage value, heritage composition, protection, and related issues. Due to the region’s rapid economic development and large-scale construction, the need to protect the Great Wall is becoming more urgent. The World Heritage Centre highlights the universal value of the evaluation criteria presented in the Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention (Citation2015), along with the requirements of authenticity and integrity in the protection of historical and cultural heritage – not only to protect the physical ruins of the wall but also to explore the overall value of the wall’s heritage, based on its development history. Although the Great Wall is China’s first World Heritage Site, its intrinsic value has not been fully recognized. The root cause of the gradual disappearance of the Great Wall’s resources is a lack of awareness. Without an understanding of the history of the Great Wall, the wall cannot be protected. Just as the Great Wall is not merely a ‘long wall,’ nor does its value inhere in its role as a set of ancient Chinese fortifications. The ancients regarded the Great Wall as a boundary determined by natural geography that linked two civilizations and cultures – nomads in the north and farmers in the south – to create a border region and cultural-integration zone within inland Asia. As evident from the formation and evolution of Ji Town, the construction of the Great Wall reflected the evolution of regional politics, economics, culture, religious beliefs, and so on. In the Chinese empire, the farming mode involved ‘building cities and resettling residents based on land scale’ (Dai.CitationBC51~BC21), and the opposite mindset emphasized ‘constructing cities to defend the King, building walls for residents’ (Lv. CitationBC239). The latter was the best way of developing and managing the northern border region. During this process, the Great Wall’s defense system was created with numerous historical functions, such as a troop-stationing system, a transmission system, a dilivery system, a military-supplies system, and a market-trading system. The material carriers of the value of the defense system are facilities and places with various functions, such as side walls, passes, fortresses, posts, beacons, and horse markets.

Basic research on the value of the Great Wall and its defense system provides a vital foundation for protecting the authenticity and integrity of the Great Wall’s cultural heritage. The comprehensive historical information gathered on the Great Wall military buffer zone and the integration of fundamental spatial information to produce a database on the Great Wall’s military settlement should provide important data-based support and management tools for the Great Wall’s heritage conservation and value assessment, and even the delineation of protection areas.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. Slope-level classification data values refer to Architectural Design Materials Collection. Second Edition (Volume 6) 《建筑设计资料集》第二版(第六册). Beijing北京: China Construction Industry Press中国建筑工业出版社, (Citation1994). P223.

Flat slope (slope value 3% or less, degree 0°–1°43′) is the ideal land for construction.

Gentle slope (slope value 3–10%, degree 1°43′–5°43′) is not affected by topography.

Mid-level slope (slope value 10–25%, degree 5°43′–14°02′) is subject to certain restrictions, and the layout needs to set a platform and lots of earthwork are needed.

Steep slope (slope value 25–50%, degree 14°02′–26° 34′) is basically unsuitable for construction, and the layout is subject to greater restrictions.

Hard slope (slope value 50–100%, degree 26°43′–45°) needs special treatment for construction.

Cliff slope (slope value 100%, degree 45° or above) needs huge construction costs.

2. The local government announced the Beijing Great Wall Protection and Management Measures (Beijing Citation2003), which provided for a 500-m non-construction area and a 500–3000-m limited construction area ‘on both sides of the Great Wall’ for temporary protection. However, 3000-m buffer zones cannot cover overall protection for the military settlements, thus the buffer zone is expanded to 5000 m for statistics.

References

- 《建筑设计资料集》第二版(第六册) [Editorial Committee of Architectural Design Materials Collection]. 1994. 2nd ed. Vol. 6. Beijing北京: China Construction Industry Press中国建筑工业出版社

- Buwei, L.V. 吕不韦, BC239. Master Lü’s Spring and Autumn Annals 吕氏春秋, edited by Zhang Shuangyu, Zhang Wanbin, Yin Guoguang, Chen Tao. Beijing: Chinese publishing house 中华书局,2007.

- Huan, W. 1541. 皇明九边考 [Imperial Ming Nine Borders History], History Great Wall Culture Network’s Production长城文化网制作. http://www.thegreatwall.com.cn/wakka/wakka.php?wakka=HomePage.

- Ji, H. 霍冀 1569. 九边图说 [Nine Borders History Map]. 1986. YangZhou 扬州: Jiangsu Guangling ancient engravings江苏广陵古籍刻印社.

- National Cultural Relics Bureau国家文物局编. 2013. 中国文物地图集(河北分册) [Chinese Cultural Relics Atlas (Hebei Volume)]. Beijing北京: Cultural Relics Press文物出版社.

- People's Government of Beijing Municipality. 2003. 北京市长城保护管理办法 [Beijing Great Wall Protection and Management Measures], 2003

- Sheng, D. 戴圣, BC51~BC21. 礼记·王制 [System of King•Li Ji]. https://zh.wikisource.org/wiki/%E7%A6%AE%E8%A8%98/%E7%8E%8B%E5%88%B6

- Tingyu, Z. 张廷玉 1739. 明史 [Ming History]. 1974. Beijing北京: Chinese publishing house 中华书局.

- UNESCO/WHC. 2015. Operational Guidelines for the Implementation of the World Heritage Convention. http://whc.unesco.org/en/guidelines/

- Wanzuan, S. 宋琬纂 1711. 永平府志(康熙) [Yongping State History.(Kang Xi)]. 2001. Beijing北京: National Library of Microfilming Document Replication Center全国图书馆缩微文献复制中心.

- Xiaozu, L. 刘效祖, 1574-1576. 四镇三关志 [Four Towns Three Passes]. HistoryGreat Wall Culture Network’s Production 长城文化网制作. http://www.thegreatwall.com.cn/wakka/wakka.php?wakka=HomePage

- Yan, L. 李严, 2007. The research of military fortresses of nine defense areas along the Great Wall in Ming Dynasty. 明长城九边军事防御性聚落研究. Dissertation (PhD). TianJin University天津大学, TianJin天津

- Zaoqing, G. 郭造卿, 1610. In 卢龙塞略 [Defense History of Lulong Border]. Compiled in the “Qinhuangdao History.” 丛编于《秦皇岛历代志书校注》. Beijing: China Audit Press 中国审计出版社, 2001.

- Zhanyi, L. 李占义. 2005. 抚宁长城 [Fu Ning County Great Wall]. Beijing北京: Wuzhou Communication Press五洲传播出版社.