ABSTRACT

The Sinai Peninsula is a vital part of the Arab Republic of Egypt, geographically and historically. Its uniqueness and diversity of nature are reflected in its place-names, including both physical and human (cultural) features. The objectives of this study are to: (1) construct a digital geo-database of place-names; (2) classify the collected names based on their meanings to understand the motives behind naming them; and (3) utilize GIS-based spatial analysis techniques to map, geo-visualize and analyse the spatial distribution pattern of specific categories of such names. In this paper, the results show that most place-names are descriptive of the place they belong, either in whole or in part. They usually depict their geographical character and that in turn demonstrates how place-names and the naming process itself represent responses to the physical environment and cultural landscape and how place-names studies reveal patterns of settlement in the region under study.

Introduction

The study of place-names (toponyms) represents a vast interdisciplinary field of research. It is not only a source of linguistic information but also of geographical, historical and socio-cultural information. Place-names generally offer a critical arena for understanding how members of a community, place or region conceptualize their geographical and spatial environments as well as their socio-cultural environment (Brown Citation2008).

Place-names use a single word or series of words to indicate, denote and identify geographic features and their location in relation to other features. They are used to distinguish one place from another, both in terms of physical features (e.g. mountains, rivers, valleys, springs) and human-made or cultural features (e.g. cities, villages, archaeological sites, remains, streets) (Alderman Citation2010). Thus, they reflect and identify both the physical and human peculiarities of a place and often change over time due to changes in physical and human peculiarities. Landforms, climate, soils and hydrology are examples of physical peculiarities. Culture, language, religions, political and economic system and population distributions are examples of human peculiarities (Tent and Blair Citation2011).

The examination of place-names in the Sinai region is the subject of this research. The main objectives of this research can be stated as follows: (1) collect and construct a digital geo-database for place-names in the Sinai region, (2) classify the collected names according to their linguistic-geographical-historical meanings into categories, and (3) analyse the spatial distribution and concentration of specific types of such names and their association with socio-cultural and environmental factors. This will help provide answers to the following questions: Are place-names of a specific type, randomly distributed or do they form a particular pattern in the study region? Do they aggregate in certain areas or are they scattered across the region? Is the spatial distribution of specific place-names associated with environmental factors? Does their distribution reflect the region’s settlement pattern?

Using GIS-based techniques, this paper shows that most types of place-names form a particular spatial pattern in the region and aggregate in certain areas. In addition, the spatial distribution of specific types of place-names is associated with human and physical factors. This study also reveals how the settlement pattern of the region is associated with the distribution of human activity-based place-names. The majority of such names concentrates in the north, especially in the northeastern most portion of the study region. That in turn reflects how the spatial perspective in place-names studies can give us clues to the settlement pattern of a particular region and how it changes over time.

Spatial perspective of place-names studies

Despite the advancement of the applications of GIS technology and its great impact in various fields, especially in health-related studies and epidemiology, demography, and criminology applications, over the past two decades, GIS-based spatial analysis applications in historical-linguistic-cultural and in place-names studies are limited.

Traditional place-names studies are basically dictionary type studies. They are qualitative and descriptive in nature: giving the location, linguistic origin and meaning of the toponyms of a particular region (Yoon Citation1980; Champoux Citation2012). They aim to identify the motive behind naming places and distinguish one specific place from another (Zelinsky Citation1955; Tent and Blair Citation2011).

Only a few studies in the recent literature have used quantitative methods, statistical, and GIS techniques to cover the sequence of toponyms over time in a place and their historical, geographical, and socio-cultural meanings as well as their spatial distribution. Most of these studies used GIS applications and spatial analysis techniques to address China place-names. For example, Luo et al. (Citation2000) demonstrated how GIS-mapping and analysis tools can integrate linguistic and geographic information to help explain migration and settlement patterns of the ethnic groups in southern China. Wang et al. (Citation2006) used GIS-based spatial analysis techniques to examine the historical past settlements of ethnic minorities in southern China from their place-names. Wang et al. (Citation2012) analysed the spatial distribution of Zhuang, the largest minority language in China, as opposed to non-Zhuang place-names and its association with cultural and environmental factors, and how the pattern changes over time.

Area of study and data collection

Historically, the importance of the Sinai region has been a result of its geographical uniqueness: as a land bridge, linking northeast Africa with southwest Asia. Geographically, it lies between the Gulf of Suez and the Suez Canal on the west and the Gulf of Aqaba on the east, and it is bounded by the Mediterranean Sea on the north and the Red Sea to the south ().

Its total area is about 62,000 square kilometres. It represents six percent of Egypt’s total area and its coastline represents about thirty percent of Egypt’s total coastline. Sinai’s population represents less than one percent of Egypt’s population. The majority of inhabitants (the total was estimated at 597,000 in 2013) are found along the Mediterranean coast in the north and live more or less along the main road from Al-Qantarah (on the Suez Canal in the west) to Rafah (on the border with the Gaza Strip in the east).

Topographically, the region is divided into three different and diverse areas. Its northern part is composed of flat expanses of sand, and agricultural and grazing areas especially in the northeastern part of the region. The central part consists of a large limestone plateau, the region of El-Tih. The southern part is a complex of high mountains made up of igneous and metamorphic rocks. These are, in turn, reflected in its place-names.

A GIS is adopted in this study to build a digital geo-database of place-names in the study region using ArcGIS 10.3 software.

Data concerning place-names, place-type, and relationship names (i.e. names transferred from nearby places or features) was compiled and their geographical locations (latitude and longitude) were identified from the 11 topographic maps (scale 1: 250,000) that cover the region as a primary source. Secondary data sources, including geological maps (scale 1: 250,000), topographic maps (scale 1: 100,000, 1: 50,000, and 1: 25,000), 2006 census data, and existing online gazetteers (e.g. GeoNames.org) were also examined to validate the study’s primary source.

Subsequently, linguistic, geographic, and topographic dictionaries especially of the nearby, Western Asian Arab countries (e.g. Saudi Arabia, Syria, Palestine, Jordan) (Groom Citation1983; Ramzi Citation1994; Dhib Citation2006), as well as historical books (Shoucair Citation1916; Mubasher and Tawfiq Citation1998), and travel literature (Bailey Citation1984; Fabri Citation2007) were used to identify the meanings and the motivation behind the place naming process.

Finally, the dataset was recorded in a GIS database for visualization and subsequent analysis. shows sample entries from the constructed geo-database.

Research methodology

A place-name usually consists of a generic element and a specific element, termed composite names, or of a specific element consisting of one or more words, called simplex names (Zelinsky Citation1955; Scott Citation2003). Abu ath-Thamayil, al-Burgah, Wasit, and al-`Imarah as-Safrah are examples of simplex names. Jabal (Mount) Saint Catherine, Madinate Nuweiba` (Nuweiba` City), Wadi Firan (Firan Valley), and Qaryat al-Gharandal (al-Gharandal Village) are examples of composite names in the Sinai region. We note that in Arabic place-names, the specific term generally follows the generic one, while in English names the specific term usually come first (Groom Citation1983).

The generic term is usually the component of place-names which indicates the type of the named place. It is either habitative (relates to a habitation) or topographical (relates to a natural feature). The habitative names contain some element which denotes a locality that is populated or inhabited such as city, town, village, and fortress. While, the topographic names describe some features of the landscape such as mountain, watercourse, wetland, sand dune, and spring. In some countries or cultures, place-names without the generic term are predominantly those for non-natural features, such as settlement centres (Tent and Blair Citation2011).

The specific term is usually used to distinguish a place from others like it and to restrict the meaning of the place-name. It usually qualifies the generic term of the composite names by providing additional information (Scott Citation2003). For example, Jabal Haytan is a steep mountain, which looks like walls. While, Jabal Muqasab is a curly mountain. Wadi al-Bahah is a place with a large number of palm trees. Whilst, Wadi al-Barah is a wide and barren tract of land without vegetation. The specific element of the simplex place-names also sometimes reflects their topographic and geographic character. For example, al-Barth (a sandy area), el-Daiqa (a narrow place), al-Mahrudah (an uneven, and crooked land), and al-Matallah (a high point used for observations).

From the discussion above, it is proposed that two different but complementary approaches, the geographical-based approach and the name-giving approach, are used to classify and analyse the collected names in this study. The first approach is used to identify the geographical character of the region while the second approach is used to investigate the factors that motivate people to name and differentiate places and geographical features (based on the meaning of the specific element of each place-name).

The inclusion of the geographic-based analysis is the novel aspect of this study. This aspect has been ignored by most previous studies. Toponymical studies only using the name-giving approach might indicate incorrect meanings for place-names. In other words, without knowing the geographical character of the named place, we cannot identify the motive behind naming it. For example, Jabal al-Maghara, in northern Sinai, is so named because of the large cave in its midst, Jabal az-Zarafah is seen as a Giraffe’s neck, and Jabal Sarbut al-Jamal and Jabal Tallat al-Jamal (al-Jamal Hill) look like a camel’s hump. Therefore, these two approaches are not mutually exclusive and complement each other.

Finally, the quantitative and GIS-based spatial analysis techniques are used to map, visualize, and analyse the spatial pattern of specific types of place-names in the region, under the two proposed approaches. Both the density tool and spatial cluster analysis technique are used to detect their spatial distribution patterns and to investigate whether the spatial pattern of certain names is consistent with the distribution of Sinai’s inhabitants. depicts the methodology of this research.

Sinai place-names classification analysis

This paper takes a different approach in classifying and analysing place-names as stated before. It goes through different stages to construct an effective classification for such names. Furthermore, it aims to show how the classification of places according to their geographical character (i.e. geographical-based approach) and the motive behind naming them (i.e. name-giving approach) are interrelated and complementary to each other. Results of classifying place-names according to these approaches are presented in the following two subsections.

Classification analysis of sinai place-names: geographical-based approach

In this study, three main stages were implemented to construct a toponymic classification for the region: (1) defining place-type based on generic terms, (2) defining place-type based on geographical location, and (3) defining place-type based on linguistic analysis.

Sinai composite names make up the majority of place-names in the region. Nearly ninety-one percent of the 2424 collected names as shown in are composite names, while the simplex names represent only nine percent.

Table 1. Percentage of Sinai composite and simplex place-names.

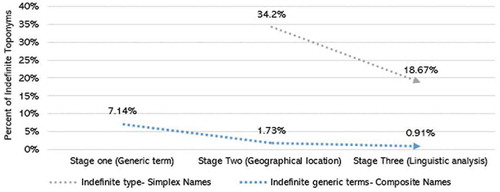

In the first stage, the place-type of each composite name was identified from the meaning of its generic term. As shown in , ninety-three percent of the composite names have a definite generic term, which specifies the nature of the geographical feature concerned.

Table 2. Percentage of composite place-names with definite generic terms (stage one) according to the geographical-based approach.

In the second stage, the constructed database was merged with topographic and geological maps using ArcGIS to relate those names with indefinite generic terms as well as the simplex names with their geographic locations in order to specify their type. This process was also carried out to check the accuracy of previously determined names. This stage defined ninety-eight percent of the composite names and sixty-six percent of the simplex names. In total, it defined ninety-five percent of the total collected names (see ). In addition, the classification of three place-names was changed by comparing this stage with the previous one (see ).

Table 3. Percentage of place-names with definite type (stage two) according to the geographical-based approach.

Table 4. List of reclassified place-names (stage two) according to the geographical-based approach.

Finally, a linguistic analysis was used to identify the type of unknown names from their meanings and to check the identified place-names (stage 3). This stage defined ninety-nine percent of the composite names and eighty-one percent of the simplex names. In total, ninety-seven percent of the total collected names were identified (see ).

Table 5. Percentage of place-names with definite type (stage three) according to the geographical-based approach.

In summary, this study shows that for the majority of place-names in the region, their generic terms reflect their geographical character. In addition, the simplex names usually describe the type of the named place or feature. compares the results of the three stages of identifying the place-type of the collected simplex and composite names. As shown, the majority of the composite names are identified from their generic terms (stage one). Only seven percent of the composite names have indefinite meaning. The second stage decreased the percentage of indefinite names to nearly two percent. Finally, the linguistic analysis stage decreased the percentage of all composite names to one percent. For simplex names, the geographical location of those places (stage two) defined the majority of them. In the third stage, the linguistic analysis stage, the percentage of unknown place-names decreased to nearly nineteen percent of all simplex names.

Figure 4. Comparison between the three stages of toponyms classification (geographical-based classification).

After identifying the place-types, the place-names were then classified under one of the following nine categories according to the geographic-based approach: landform, water sources and channels, settlement centres, archaeological and historical places, transport and communication networks, cultivation and grazing, natural vegetation, and economic activities as well as unknown features. The classification of a sample of the collected names is presented in , and the classification for all the collected names according to this approach is presented in .

Table 6. Classification of some places based on their feature-type (geographical-based approach).

The majority (nearly seventy percent) of the collected names refer to the landforms of the region, which depict the topographic and geographic character of the different named places and features (see ). This in turn reflects the significant impact of Sinai’s environment on the naming process. Water-based names represent nearly seventeen percent of the names and that in turn reflects the scarcity of water sources in the region. The percentage of Sinai’s population compared to the whole Egyptian population, as stated before, is also reflected in the percentage of settlement-based names. As shown, five percent of the collected names are classified under the settlement centres. Finally, the other five categories have a low percent of total place-names. However, we should note here that the number of the collected names under economic activities does not reflect the actual distribution of such activities in the region (as depicted, for instance, by the mineralogical map of Egypt issued by the Geological Survey).

Table 7. Classification of Sinai place-names based on place-type (geographical-based approach).

Classification analysis of sinai place-names: name-giving approach

Most names in the region seem to be evidently Arabic. However, some of them are ambiguous even to the Bedouin themselves, mainly because they were named by non-Arabs. Unintelligible names might have originated in pre-Arabic culture and there are no sufficient ancient maps and documents to help us coordinate such names with contemporary names. It also seems that most of them were corrupted into completely meaningless forms. Examples include Lussan from Roman Lyssa, Firan from Pharan, and Gharandal from Greek Surandela (Bailey Citation1984).

The region has only a few sites populated or visited by successive generations that might retain the history, origins, and meanings of names. This is because Bedouins have always been wary of each other’s territorial ambitions and guard the secret of their tribal lands. Most of the Bedouin tribes of the Sinai are descended from peoples who migrated from the Arabian Peninsula. They have a rich culture and their own Arabic ‘Bedawi’ language, which has different dialects depending on the area where they live. These dialects in turn have a significant impact on names specifics. Many questions about the linguistic characteristics of these dialects remain unanswered. Therefore, we dealt with a very complex socio-cultural system (De Jong Citation2011).

The number of Arabic geographical and topographical words is further increased by the nature of the language itself. It usually provides many variations of the same word. Some variations represent nuances of difference from the basic meaning, but most of them are simply alternatives. Arabic words take many different forms derived from the basic root of three consonants, known as radicals. For instance, Abraq, Abeiriq, Abriqayn, Barq, Bayraq, Burqah, Mutabrqah are derived from brq (). Many nouns have several different plural forms, and Arabic is an evolved language, so many Arabic words have changed over a period of time and/or through geographical separation (Groom Citation1983).

Table 8. Different forms from the basic root (brq).

Consequently, the collected names are firstly classified based on the meanings of their specific terms under the following three main categories: mono-meaning, multi-meaning, and unknown meaning (see ). The majority (nearly sixty-four percent) of names specifics as shown in have a specific meaning, and nearly fourteen percent have multiple meanings, while twenty-two percent of them have unknown meanings. Future field studies and interviews with settlers may help in this matter.

Table 9. Classification of Sinai place-names meanings according to the name-giving approach.

Secondly, the mono-meaning ones are classified under the following categories: landform, natural vegetation, water sources, land use, wildlife, location, transport and communication networks, and climate and hosting places, as well as personal names, historical, myth, or religious place-names, and development-oriented names (). The classification of a sample of the collected names is presented in .

Table 10. Classification of mono-meaning Sinai place-names according to the name-giving approach.

Table 11. Classification of some places based on the meaning of the specific terms (name-giving approach).

In brief, the following are the main six categories of our classification for place-names specifics and the percentage of each category is presented in :

Descriptive names allude to a characteristic of the place or feature or surrounding area, names derived from other feature, or characteristics of the natural environment including landscape, topography, soil, water bodies, animals or plant life. In addition to names taken from other places or features, descriptive names can refer to names transferred from nearby places or features, and names imported from earlier residents of first settlers (i.e. transferred place-names). For example, Wadi al-Ahmer in south Sinai carries the name of the nearby mountain (Ra’s al-Ahmer), and Qaryat Qabilah at-Tarabin in north Sinai, Tallat at-Tarabin and Qaryat at-Tarabin in south Sinai carry the name of the Tarabin tribe which derives its name from the Tarban valley in Saudi Arabia. This category includes the following subcategories: landform, natural vegetation, water source(s), land use, wildlife, location, transport and communication networks, and climate and hosting places. shows examples of such names and their meanings.

Historical and incident names record historical, mythological events, and incident associated with the feature or place. Examples of such names and their meanings are presented in .

Personal names use the proper name of a person, group, family or tribe to name a feature or a place.

Development-oriented names include new settlement centres, and tourist villages. Examples of personal and development-oriented names are presented in .

Multi-meaning names include all place-names that have been classified under multi-meaning category. These kinds of places have multiple meanings according to the different sources of information. For example, Jabal al-Halal (sheep in Sinai tribal dialects or corrupted from al-Helal (Crescent-shaped mountain)) (Shoucair Citation1916; Fabri Citation2007), and Jabal al-`Ajmah (rock protruding in a valley; a sand-hill raising above its surroundings; solid rocks; kind of palm trees; or a tribe’s language).

Unknown-meaning names include those names of unknown etymology, where the meaning, reference, referent, or origin of the toponym is unknown.

Table 12. Classification of Sinai place-names specifics according to the name-giving approach.

Table 13. Examples of descriptive Sinai place-names (name-giving approach).

Table 14. Examples of historical and incident Sinai place-names (name-giving approach).

Table 15. Examples of personal names and development-oriented names (name-giving approach).

Under the two proposed classification approaches, this study indicates that the majority of place-names are descriptive of the place they refer to, either in whole or in part. Most of the collected names are composite, consisting of two elements, a generic and a specific element, with a linguistic relation between them. These elements are the words that people used to describe a place and to distinguish one place from other places and geographical features. Some of the collected names are simplex names, consisting of a specific element only, with one or more words. Most of such simplex names also describe the topographic and geographical character of the named place or feature in the region. That in turn reflects how Bedouins usually used place-name elements to describe and define their surroundings. Furthermore, without knowing the geographical character of the named place or feature, we cannot investigate the motive behind naming it.

Geo-visualization and modelling spatial pattern of sinai place-names

The importance of the spatial perspective in interdisciplinary research and studies in the humanities and social sciences has received considerable attention over the past few decades (Badurek Citation2007). For instance, anthropologists, researchers in the humanities, and other social scientists use spatial analysis techniques to analyse and display the spatial distribution of material culture (artefacts), to map linguistic, social, cultural and ethnic traits, and to place historical analysis in a spatial-geographical context (Luo et al. Citation2000; Majeed Citation2010).

Using GIS tools and spatial analysis techniques not only makes information easier to grasp but provides more dimensions to display, analyse and interpret data. They represent a major advancement in place-names studies because GIS tools enable the systematic examination of spatial patterns of place-names and their association with environmental factors (Zhang Citation2012; Chen et al. Citation2014).

In this study, based on our previous classification, GIS-based spatial analysis tools and clustering methods are applied to geo-visualize, analyse, and interpret the spatial pattern of specific types of place-names and to identify their spatial distribution and concentration in the region. In this section, we present the spatial distribution of human activity-based names that in turn help us to reveal the settlement pattern of the region including the following categories: settlement-based names, cultivated and grazing areas, personal-based names, land-use-based names and development-oriented names.

The locations of the collected place-names were displayed as point features using ArcGIS. The kernel density estimation (KDE) tool embedded in ArcGIS was used in this study to identify, display and analyse the spatial distribution and concentrations (hotspots) of place-names under the previous categories. KDE is one of the spatial analysis techniques that deals with point and polyline features and provides a more useful representation of features distribution. KDE has been widely used for geo-spatial analysis, hotspot analysis and detection. It calculates the density of features in a neighbourhood around those features and distributes a measured quantity of an input data layer throughout a landscape to produce a continuous surface (Okabe, Satoh, and Sugihara Citation2009). In this study, the default search radius (bandwidth) is used. It is calculated based on the spatial configuration and number of input points to correct for spatial outliers, so they will not make the search radius unreasonably large. The place-names density is represented by colours. Dark regions represent areas of high density, while the regions of low density are represented by white colour.

Spatial scan statistics (SaTScan) was also performed to detect whether the occurrence of a specific type of place-names in some areas are significantly more frequent than other areas. SaTScan uses computer simulations to generate a number of random replications of the data set under the null hypothesis. The null hypothesis of SaTScan states that the event is randomly distributed in geographic space. The alternative hypothesis states that there is an increased number of events within an area compared with those in the outside areas (Kulldorff Citation2014).

A Bernoulli model (with a pure spatial scan) was used for the analysis in this study. In our case, human activity-based names serve as cases (coded as 1) and non-human activity-based names serve as controls (coded as 0). The aim is to test whether or not the point events (locations of human activity-based names) are clustered in a subset Z within the study region R. For the Bernoulli model, each individual (place-name) within the zone Z ⊂ R has a probability p of being a case inside the zone, while the probability of being a case outside the zone is q. The probability for any one individual is independent of all the others. The null hypothesis of no clustering is H0: p = q and the alternative hypothesis H1: p > q for high clusters (or p < q for low clusters). The likelihood function for a specific window Z under the Bernoulli model is:

where N is the total number of cases (human activity-based names) in the study area, n is the number of cases in the window, M is the total number of controls (non-human activity-based names), m is the number of controls in the window, p = n/m (probability of being a case within the window) and q = (N-n)/(M-m) (probability of being a case outside the window).

The rejection of the null hypothesis for each circle is based on a likelihood ratio statistic . The circle with the maximum likelihood is defined as the most likely cluster (the primary cluster), the one least likely to have occurred by chance. The likelihood ratio for this window constitutes the maximum likelihood ratio test statistic. Its distribution under the null hypothesis and its corresponding p-value are determined by a Monte Carlo simulation approach, where the null hypothesis of no cluster is rejected at level of alpha equal 0.05 exactly if the simulated p-value is less than or equal 0.05 for the most likely cluster (Kulldorff Citation1997; Meng Citation2010).

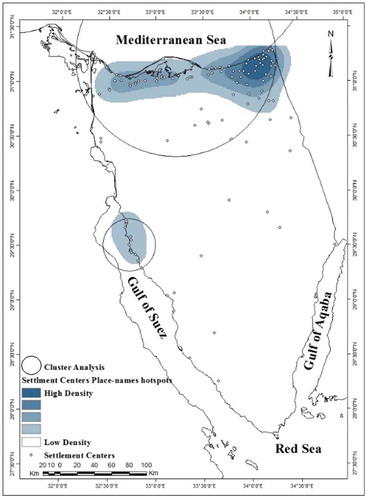

The results of both techniques, KDE and SaTScan, show that the highest geographical concentration of settlement-based names is in the north area, especially in the northeastern most portion of the region with a minor concentration in the south-west Sinai, near to the Gulf of Suez ().

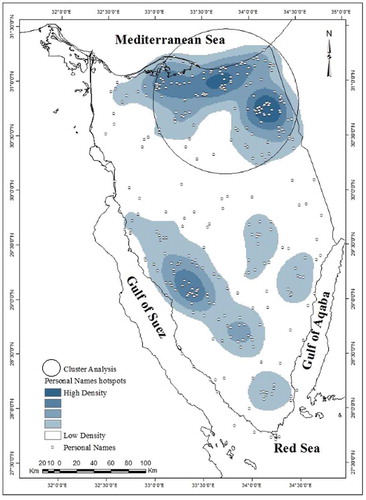

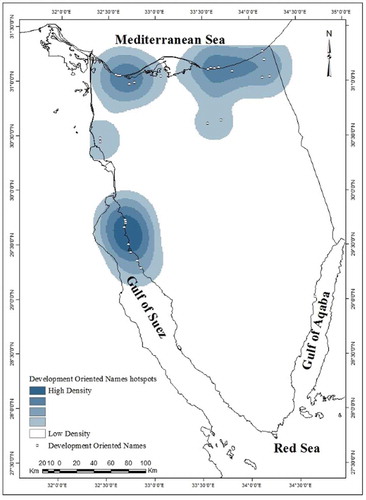

For twenty percent of names, as shown in , their specific terms carry the name of a person, family, or tribe. For example, the majority of artificial water sources in north Sinai are named by the name of their owner(s) due to the scarcity of water sources, which represent one of the obstacles for the development of the region. shows that the major concentration of personal-based names is in the north with a minor concentration in the south, near to the Gulf of Suez.

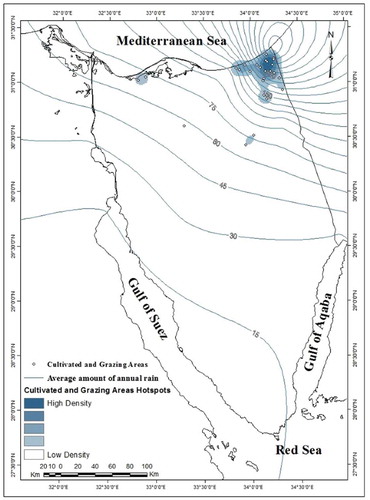

The remaining categories include a small number of place-names and SaTScan is not a suitable method in such cases. Therefore, the KDE is only used to investigate the spatial distribution of such names. shows that the highest concentration of the cultivated and grazing areas according to the geographical character of place-names is in the northeastern most portion of the region. It also displays the annual average rainfall over the region. The annual average rainfall is 66 mm3 while the highest average rainfall (304 mm3) is in Rafah (in the northeastern corner of the region) and, as shown, the distribution of such names is closely related to the distribution of rainfall and underground water in the region. That in turn, reflects how the spatial pattern of specific types of place-names is associated with environmental and human factors and confirms the previous conclusion concerning the spatial settlement pattern of the region.

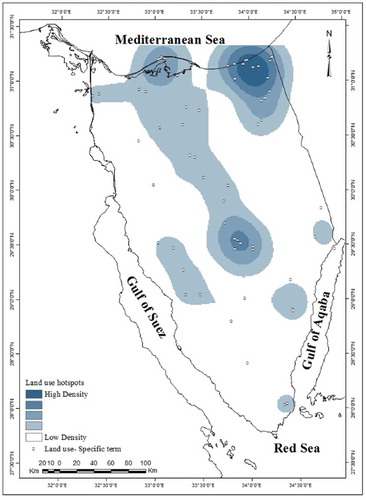

shows that the major concentration of land use areas is in the north and that conforms to the population settlement pattern. In addition, there is a minor concentration in the middle region of Sinai that is related to a group of historical-religious locations. These locations represent the major stops on the ancient Islamic pilgrimage of the Hajj across central Sinai to Mecca, especially Nikhel fortress. Nikhel was constructed on the pilgrimage route, named Darb al-Hajj (al-Hajj route), that crossed the Tih Plateau. It was the supply post for pilgrims on the Hajj pilgrimage route to Mecca.

Finally, shows that the highest concentrations of development-oriented names are in the north and the south-west, near to the Gulf of Suez.

From the above, we can conclude that the spatial distribution and concentrations of the previous place-names categories reflect how the spatial perspective in place-names, employing the applications of GIS technology, can give us clues to the settlement pattern of the region under study. The majority of such names are concentrated in the north, especially the northeastern most portion of the Sinai Peninsula. They form a particular spatial pattern in the region and aggregated in certain areas in the region. In addition, the spatial patterns of such names are associated with human and physical factors.

Discussion and conclusion

The unique nature of the Sinai region, its diversity of geographical and natural features, and its environmental, historical, cultural and religious importance are reflected in its place-names, either in whole or in part of the name. This study shows that the majority of the collected place-names are composite names, consisting of two elements, a generic element and a specific element, with a linguistic relation between them. It also shows that the majority of Sinai place-names’ elements, especially the generic terms, describe the landform and its variations. These terms are usually used to describe features found in the Sinai landscape.

In this study, each place-name was classified under two categories according to the two proposed approaches: the geographical-based approach and the name-giving approach. The first approach, the geographical-based approach, is used to classify each place-name according to its geographical character, while the second one, the name giving approach, is used to identify the motivations behind naming Sinai places and geographical features and distinguish one place from other places using a specific term. These two approaches are not mutually exclusive and complement each other. There are some common categories under the two proposed approaches. This is because the majority of specific elements of the collected composite place-names usually qualifies the generic element of the place-names by providing additional information. For example, Ra’s Abu Qurun is a peak (more specifically a horn-shaped peak). In addition, the majority of the simplex names describes the geographical character of the named place or feature. For example, al-Qur is a place of hills (more specifically small hills).

The results of the GIS-spatial analysis techniques show that the settlement toponyms, cultivation and grazing toponyms and land use toponyms concentrate in the north area, especially in the northeastern most portion of the Sinai Peninsula. The development-oriented place-names concentrate in the north and the south-west near to the Gulf of Suez. The personal toponyms concentrate in the north with a minor concentration in the south-west, near the Gulf of Suez. The spatial pattern of such types of toponyms reflect the settlement pattern of the Sinai region, where the majority of Sinai’s inhabitants are found along the Mediterranean coast to the north, who live more or less along the main road Al-Qantarah (on the Suez Canal in the west) to Rafah (on the border with the Gaza Strip in the east).

This study also shows how the distribution of specific type of place-names is associated with environmental and human factors. For instance, the spatial distribution of the cultivation and grazing toponyms is closely related to the distribution of rainfall in the Sinai region. It also reveals how the settlement pattern of the Sinai region is associated with the distribution of human toponyms in the region. The majority of such toponyms concentrates in the north, especially in the northeastern most portion of the Sinai Peninsula. That in turn reflects how the spatial perspective in toponymic studies can give us clues to the settlement pattern of a particular region and how it changes over time.

The applications of geographic information system (GIS) technology represent therefore a major progress in recent toponymic studies. This study employs GIS techniques to construct and analyse a geo-database of Sinai place-names, and their spatial distributions and concentrations in the study region. This study is exploratory in nature for the distribution of specific types of place-names in the Sinai region. It aims to demonstrate the importance of the spatial perspective and the great potentials of GIS-based techniques in toponymic studies.

To better visualize the spatial pattern of place-names concentration, a spatial analysis technique, the kernel density estimation (KDE) is used to provide a useful representation of place-names distribution under each category. While, the KDE is useful for mapping the place-names, it is merely descriptive, even randomly distributed place-names may appear to exhibit some local pockets of concentration. The spatial cluster analysis (SaTScan) is then used to detect whether the occurrences of specific types of place-names in some areas are significantly more frequent than other areas. The results show that most types of place-names form a particular spatial pattern in the region and aggregate in certain areas. In addition, the spatial patterns of specific types of names are associated with environmental and human factors.

In summary, this article investigates how the spatial distribution of specific types of place-names is significant in indicating certain geographical, historical and socio-cultural characteristics of the Sinai region.

the discussion above, a number of recommendations for further research can be deduced. First of all, fieldwork and interviews with Sinai Bedouins can make a valuable contribution to this study. They can give clues to the geographic and economic characteristics that motivate Bedouins to settle in particular places, and how the settlement started.

In addition, it is believed that it would be of great value if the scope of the study is extended to include a comparative analysis of identical place-name clusters. Named places or features have identical names if the full form of the place-names, together with the generic term, are identical. It can provide us with dynamic clues to the movement and immigration of Sinai Bedouins from one region or place to another.

Finally, more in-depth analysis can be conducted to examine and analyse the association of place-names with geographic and socio-economic factors, and to test whether the distribution of population is consistent with human activity-based names and other names.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in Egypt aiming to investigate the spatial perspective of the place-names studies and how the linguistic-geographical-historical meanings of such names can give us clues to the settlement pattern of the region under study; thus, this study is just a beginning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Alderman, D. H. 2010. “Place Naming and the Politics of Identity: A View from Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd., USA.” Interaction 38 (3): 10–14.

- Badurek, C. A. 2007. “Facilitating Inquiry into Spatial Displacement with GIS.” Sociation Today 5 (1). http://www.ncsociology.org/sociationtoday/v51/chris.htm

- Bailey, C. 1984. “Bedouin Place-Names in Sinai: Towards Understanding a Desert Map.” Palestine Exploration Quarterly 116: 42–57. doi:10.1179/peq.1984.116.1.42.

- Brown, P. 2008. “Up, Down, and across the Land: Landscape Terms, Place Names, and Spatial Language in Tzeltal.” Language Sciences 30: 151–181. doi:10.1016/j.langsci.2006.12.003.

- Champoux, G. J. 2012. “Toponymy and Canadian Arctic Sovereignty.” Review of Historical Geography and Toponomastics 7: 11–37.

- Chen, X., T. Hu, F. Ren, D. Chen, L. Li, and N. Gao. 2014. “Landscape Analysis of Geographical Names in Hubei Province, China.” Entropy 16: 6313–6337. doi:10.3390/e16126313.

- De Jong, R. 2011. A Grammar of the Bedouin Dialects of Central and Southern Sinai. Leiden: Brill.

- Dhib, M. 2006. A Dictionary of Cities and Villages in South Syria (Levant). A Linguistic, Historical, Archaeological Study about the Names of Historical Cities, Villages, and Hills in South Syria in Addition to Recent Statistics. Damascus: Dar Al`Arrab for Studies, publishing and translation (In Arabic).

- Fabri, F. 2007. Le Voyage En Égypte De Félix Fabri, 1483, Tr. J. MASSON Et G. HURSEAUX. Le Caire: Institut français d’archéologie orientale.

- Groom, N. S. J. 1983. A Dictionary of Arabic Topography and Placenames: A Transliterated Arabic-English Dictionary with an Arabic Glossary of Topographical Words and Placenames. Beirut: Librairie du Liban; London: Longman Group.

- Kulldorff, M. 1997. “A Spatial Scan Statistic.” Communications in Statistics: Theory and Methods 26 (6): 1481–1496. doi:10.1080/03610929708831995.

- Kulldorff, M. 2014. SaTScan™ User Guide for Version 9.3 [Online]. Accessed 10 January 2015. http://www.satscan.org/.

- Luo, W., J. F. Hartmann, J. Li, and V. Sysamouth. 2000. “GIS Mapping and Analysis of Tai Linguistic and Settlement Patterns in South China.” Geographic Information Sciences 6 (2): 129–136.

- Majeed, S. M. 2010. Cluster detection and analysis with geo-spatial datasets using a hybrid statistical and neural networks hierarchical approach. PhD thesis. University of Glamorgan.

- Meng, G. 2010. Social and Spatial Determinants of Adverse Birth Outcome Inequalities in Socially Advanced Societies. Thesis (Doctor of Philosophy in Planning), University of Waterloo, Canada.

- Mubasher, A., and I. Tawfiq. 1998. Sinai: Location and History . Cairo: Dar El Maaref. (In Arabic).

- Okabe, A., T. Satoh, and K. Sugihara. 2009. “A Kernel Density Estimation Method for Networks, Its Computational Method and A GIS-based Tool.” International Journal of Geographical Information Science 23: 7–32. doi:10.1080/13658810802475491.

- Ramzi, M. 1994. The Geographical Dictionary of the Egyptian Lands from the Time of the Ancient. Egyptians to 1945. Five Volumes (In Arabic). Cairo: General Egyptian Book Authority.

- Scott, M. 2003. “Scottish Place-Names.” In The Edinburgh Companion to Scots, Eds. C. John, S. Jane, and M. J. Derrick, 17–30. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press.

- Shoucair, N. 1916. Ancient and Modern History of Sinai and Its Geography, with a Summary of the History of Egypt, Syria, and Lebanon, Iraq and the Arabian Peninsula. (In Arabic). Cairo: General Authority for Cultural Palaces.

- Tent, J., and D. Blair. 2011. “Motivations for Naming: The Development of a Toponymic Typology for Australian Placenames.” Names 59 (2): 67–89. doi:10.1179/002777311X12976826704000.

- Wang, F., G. Wang, J. Hartmann, and W. Luo. 2012. “Sinification of Zhuang Place Names in Guangxi, China: A GIS-based Spatial Analysis Approach.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers Content Alert 37 (2): 317–333. doi:10.1111/tran.2012.37.issue-2.

- Wang, F., J. Hartmann, W. Luo, and P. Huang. 2006. “Gis-based Spatial Analysis of Tai Place Names in Southern China: An Exploratory Study of Methodology.” Geographic Information Sciences 12 (1): 1-9. doi:10.1080/10824000609480611.

- Yoon, H.-K. 1980. “An Analysis of Place Names of Cultural Features in New Zealand.” New Zealand Geographer 36: 30–34. doi:10.1111/j.1745-7939.1980.tb01921.x.

- Zelinsky, W. 1955. “Some Problems in the Distribution of Generic Terms in the Place–Names of the Northeastern United States.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 45 (4): 319–349. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1955.tb01491.x.

- Zhang, L. 2012. GIS-Based Spatial Analysis of Place Names in Yunnan, China. Master’s Thesis. Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College.