?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Income-related housing allowances are used by most advanced welfare states to ensure that their citizens have access to decent accommodation at a price within their means. Surprisingly, comparing outcomes when the subsidy is paid to the claimant or direct to the landlord has attracted little attention, despite differences existing between countries. This paper uses data collected as part of the evaluation of the Direct Payment Demonstration Projects (DPDPs) in Great Britain to test the impact on rent collection and arrears of paying Housing Benefit to tenants, as oppose to the landlord direct. The DPDPs aimed to provide learning in readiness for the introduction of Universal Credit, which sees six separate benefits consolidated into one monthly payment made to the claimant. Using quasi-experimental rental account analysis techniques, the direct payment was found to have a significant negative effect on both rent collection and arrears. However, evidence suggested that the longer term impact may be smaller as tenants become more ‘normalised’ to having responsibility for paying their rent. These findings make an important contribution to the major theoretical debate on the effectiveness of using welfare policy to promote ‘responsibilisation’, which has become the dominant discourse since the mid-late 1990's.

Introduction

Income-related housing allowances are used by most advanced welfare states to ensure that their citizens have access to decent accommodation at a price within their means. The precise instruments used vary between countries and over time (see Kemp, Citation2007 for a review). There is an established academic literature on housing allowances that has assessed and compared regimes. However, surprisingly, the effects of paying the subsidy to the claimant, rather than the landlord direct, has attracted little attention.

In the United Kingdom (UK), for over 30 years, payment of housing allowance for tenants in the social housing sector (Housing Benefit) has been made direct to the landlord as the norm. This is in contrast to many developed countries such as the United States, Germany, France and the Netherlands (Kemp, Citation2007). However, the introduction of Universal Credit, as part of a wider government welfare reform agenda which seeks to encourage responsibilisation, assures, sees a major change in how Housing Benefit is administered, following earlier changes in the private rented sector. Under Universal Credit in the majority of cases the housing allowance is paid monthly, within a total Universal Credit payment, direct to the tenant. Tenants then have responsibility for paying their own rent to their landlord.

This paper considers the impact on rent collection and arrears of giving tenants the responsibility for paying their Housing Benefit to their landlord. In 2012, the then Coalition Government established Direct Payment Demonstration Projects (DPDPs) in six local authorities to test the direct payment of Housing Benefit to social housing tenants. The Demonstration Projects were to provide lessons for the design and implementation of Universal Credit. They also provide a unique natural experiment to test the impact of direct payment on rent collection and arrears. In this case study, there has been a change in the payment method of Housing Benefit for a limited number of tenants, thus allowing Differences-in-Differences analysis of rent collection and arrears data against a quasi-experimental matched comparator: tenants not considered for participation on the trial and who remained on the incumbent landlord payment method. Underpinning this analysis are tenant level rent account and Housing Benefit administrative data collected as part of the evaluation of the DPDPs.

The findings fill two important gaps in the literature which are of relevance both within the UK and also elsewhere. First, they quantify the impact on rent collection and arrears of giving tenants responsibility for paying their housing allowance to their landlord. To the author’s knowledge, this has not previously been addressed in the literature on housing allowances. Indeed, there has not been a similar change in the payment method in other countries to allow a similar scientific analysis of the impact of direct payment of Housing Benefit on rent collection and analysis. Second, this paper contributes to the evidence based on the welfare policy and responibilisation, in particular, whether tenants adapt to new benefit payment structures and manage paying their rent on a monthly basis.

Following this introduction, this paper introduces Housing Benefit and explains Universal Credit and the direct payment of Housing Benefit. This paper then considers the theoretical impact of direct payment on rent collection—including specifying the hypothesis and themes to be explored—and provides a review of the limited evidence base. Sections six, seven and eight introduce the DPDPs and provide a description of the methods used and the subsequent results. A discussion and a conclusion then follow.

Housing Benefit

Housing Benefit is an income-related housing allowance introduced in the UK through the Social Security and Housing Benefit Act (1982). It provides mean tested benefit paid to social and private tenants on a low income to help them pay their rent. Until recently, for tenants in the social housing sector, it has typically been paid direct to the landlord on the tenant’s behalf.

Unlike many other countries which operate ‘housing gap’ schemes (Howenstine, Citation1986), Housing Benefit has an income support function. Recipients receive an amount which means they have an income that is no less than the social assistance benefit rate after eligible rent is deducted (Hills, Citation1991; Kemp, Citation2007). Some claimants receive ‘full Housing Benefit’—equal to 100% of their eligible rent—if they are in receipt of a passported benefit (being in receipt of the following benefits entitles the recipient to full Housing Benefit: Income Support, Jobseekers Allowance (income based) Employment and Support Allowance (income-related) and Pension Credit (guarantee credit)) or have an income not in excess of the social assistance benefit rate. If a claimant has an income of more than the social assistance rate, they are entitled to ‘partial Housing Benefit’: a payment equal to their eligible rent minus 65% of the difference between their net rent and the social assistance benefit rates.

A succession of problems have been highlighted in the design and administration of Housing Benefit in Britain, mirroring the experience in other countries (Kemp, Citation2007). These include paying the benefit direct to the landlord removed the link between rent payment and the tenant, meaning housing appeared as a free good; the high taper provided strong work disincentives (Gibb, Citation1995); the system covered 100% of rent (albeit subject to restrictions) thus creating a moral hazard, reducing any incentive for claimants to seek better or more appropriate housing (Kemp, Citation1998; Citation2000) and encouraging overconsumption (Hills, Citation1991; Gibb Citation1995); the system contained relatively high horizontal inefficiencies, in which it was not restricted to those most in need; and the costs of the system had risen dramatically, and because entitlement was in demand, it led to a fear of uncontrollability (Haffner & Boelhouwer, Citation2006; Priemus, Kemp, & Varady, Citation2005).

Universal credit and the direct payment of Housing Benefit

In July 2010, the newly elected Conservative-Liberal Democrat Coalition government in the UK published 21st Century Welfare (Department for Work and Pensions, Citation2010a), a consultation document on the reform of the benefits system. The analysis concluded that the existing system was too complex and presented disincentives to move into work which resulted in rising costs of welfare support and persistent welfare dependency (Ferrari, Citation2015). The principles and proposals set out in the consultation paper were detailed further in the White Paper, Universal Credit: Welfare that Works (Department for Work and Pensions, Citation2010b) and enshrined in law when the Welfare Reform Act 2012 (Department for Work and Pensions, Citation2012) received royal assent in March 2012.

The flagship feature of this Act was the introduction of Universal Credit which led to major changes in the mix of benefits and Tax Credits people could receive, the support offered as well as the conditions and work-related expectations placed on claimants. It provided a single system of mean-tested support, with the merger of six existing benefits—including Housing Benefit—for working age people, who were in or out of work, into a single monthly benefit payment paid to the claimant. This represented a major change for claimants in the social housing sector, particularly those on full Housing Benefit, as they are given the responsibility for paying their own rent to their landlord—some of whom would never have previously experienced this expectation.

A number of safeguards were put in place to support tenants, including Alternative Payment Arrangements (APAs) for claimants who genuinely could not manage their monthly housing cost payment. APAs include having a managed payment to the landlord, a split payment or a more frequent payment. The need for an APA may be identified at the onset by a Jobcentre Plus work coach during a Work Search Interview, alongside Personal Budgeting Support or during the claim. APAs can also be triggered by the claimant, their representative, or the landlord advising of a build-up of rent arrears.

The introduction of Universal Credit represents a continuation of the new welfare state model ‘responsibilisation agenda’ (Peeters, Citation2013) which looks to ‘enable’ (Gilbert, Citation2002) and ‘prepare’ individuals to prevent and deal with social harms (Peeters, Citation2013). Responsibilisation developed out of governmentality studies and refers to the ‘process whereby subjects are rendered individually responsible for a task which previously would have been the duty of another—usually a state agency—or would not have been recognised as a responsibility at all’ (O'Malley, Citation2009, p. 276). The subject is then called on to take an active role in resolving and protecting themselves from their own social problems (Shore & Wright, Citation2011).

Strategies for rendering social housing tenants as ‘responsible subjects’ are not new (Flint, Citation2004). However, giving tenants' responsibility for paying their rent has been seen as important in breaking the dependent relationship between the individual and the state and to prevent housing appearing like a free good. In turn, this would provide positive externalities. For example, it would create aspirational tenants keen to better themselves (Raco, Citation2009); tenants would become more effective money managers; and it would incentivise and smooth the transition into paid work (IPPR, Citation2010; Keohane & Shorthouse, Citation2012).

This paper assesses the impact of direct payment on landlords in terms of reduced rent collection and arrears. The next section considers the theoretical impact and specifies the hypothesis and themes that are tested later.

Impact of direct payment of Housing Benefit on rent payment: theory

The previous section explains that the move to the direct payment of Housing Benefit to tenants is a part of wider welfare reform to promote responsibiliation of social housing tenants. This paper considers just one aspect of responsibilisation: whether tenants pay their rent as expected using landlord rent collection rates. In this context, a self-managing tenant understands that they are entangled in widespread ties, dependencies and duties to others (Trnka & Trundle, Citation2014) and is able to enact their responsibility to pay their rent to their landlord. Other authors have used the same evidence base to consider the wider impacts and experiences of direct payment on tenants and landlord (Hickman, Kemp, Reeve, & Wilson, Citation2017; Department for Work and Pensions, Citation2014a).

In a basic theoretical model of rent collection provided below, (1) the expected amount of rent collected by a landlord (E(r)) is a proportion (P) of the total amount of rent due (r), where P, the proportion of rent collected, is itself a function of factors including payment method, age, household type, economic status, income, Housing Benefit receipt, and whether Housing Benefit is paid to the tenant or landlord direct

(1)

(1)

The success of tenants in taking responsibility for paying their rent can be quantified by assessing the impact of direct payment, compared to landlord payment, on the proportion of rent paid: P in EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) . This paper tests and quantifies the hypothesis that giving tenants the responsibility for paying their Housing Benefit to their landlord has a negative impact on rent collection and arrears. This is because not all tenants will be able to successfully take control for paying their rent on time. Thus, all things being equal, additional payment risk is added into EquationEquation (1)

(1)

(1) , reducing the value of P.

Sharon Wright's (Citation2016) two contrasting constructions of the active welfare subject are useful to explain why tenants may not be able to successfully take responsibility for paying their rent. Some tenants will not have sufficient financial capability to become responsible for their rent payment. Wright terms this the dominant model where recipients are viewed as inherently deficient. The World Bank (Citation2013, p. 7) defines financial capability as ‘the internal capacity to act in one’s best financial interest given socioeconomic environmental conditions. It therefore encompasses the knowledge, attitudes, skills and behaviours of consumers with regard to managing their resources and understanding, selecting and making use of financial services that fit their needs’. The literature on financial capability reveals that as one might expect, some population groups are less capable. These include young adults, particularly those aged 18–24 years (Money Advice Service, Citation2015) as well as ‘recipients of benefits being replaced by … [Universal Credit]…, in particular unemployed people’ (Money Advice Service, Citation2015, p. 5).

Alternatively, under Wright's second construct, tenants may be responsible subjects, however, economic and power structures (Lister Citation2004, p. 174) may mean that other factors hinder their ability to successfully pay their rent. For instance, they have insufficient money in their account to honour payments or there are administrative issues due to payments not being set up properly.

Quantifying the average reduction in collection rates and arrears alone provides a blunt, high-level, assessment of the impact of Direct Payment. A more nuanced analysis is therefore also undertaken in this paper that views a tenant's transfer to direct payment as a process. This analysis is informed by Normalisation Process Theory (NPT), a middle range theory derived from empirical analysis of health care settings. NPT provides useful framework to understand and evaluate the embedding of material practices in social contexts. It proposes (Elwyn, Légaré, van der Weijden, Edwards, & May, Citation2008; May & Finch, Citation2009): (1) practices become routinely embedded—or normalised—in social contexts as the result of people working, individually and collectively, to enact them. (2) The work of enacting a practice is promoted or inhibited through the operation of generative mechanisms (coherence, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring) through which human agency is expressed. (3) The production and reproduction of a practice requires continuous investment by agents in ensembles of action that is carried forward in time and space.

NPT gives way to three further themes to consider in the discussion section. First is whether the impact is consistent over time? Proposition three of NPT suggests that the successful reproduction of tenants having responsibility for paying rent requires continuous investment by agents in ensembles of action that are carried forward in time and space. Therefore, improved rent payment actions will occur over time as greater exposure to direct payment promotes, and embeds, more positive disposal (interactional workability), confidence (relational integration), performance (skill-set workability) and realization (contextual integration).

The second theme of discussion is to what extent is the negative impact due to tenants who switch back within the first few periods on direct payment? Proposition two of NPT proposes that successful normalisation of a practice requires the necessary skills, attributes and mechanisms—what NPT terms skill-set workabilities—to improve performance. Without proper assessment and support there can be limited contextual integration, meaning some tenants transferred onto direct payment without the necessary skills to execute and realise the practice of paying their rent successfully. As a result, it is highly likely that some tenants were transferred onto direct payment that under more developed criteria would have been safeguarded and/or supported. Many of these tenants are likely to have quickly accrued arrears and switched back.

The final theme of discussion is whether tenant's payments follow patterns? This reflects NPT's construct of the need to invest in reflective monitoring and evaluation of payment patterns to understand how tenants produced and reproduced the new process of paying their rent following direct payment of Housing Benefit. Learning from monitoring and evaluation can be used to identify issues in the normalisation of tenants to successful pay their rent and inform interventions for improved practice.

The next section considers the limited evidence base on direct payment of Housing Benefit.

Impact of direct payment of Housing Benefit on rent payment: evidence

The international literature on housing allowances has tended to focus on issues such as the efficacy of the Housing Benefit system as a whole (Kemp, Citation1998; King, Citation1999; Kemp, Citation2000; Kemp, Wilcox, & Rhodes, Citation2002; Stephens, Citation2005); comparing systems (Kemp, Citation2000; Priemus & Kemp, Citation2004); the impact of changes to the system (Gibbons & Manning, Citation2006; Fenton, Citation2011); and its cost (Phillips, Citation2013; Johnson, Citation2015; Wilcox & Perry, Citation2014). Despite differences between countries little attention has been given in the literature to the effects of paying housing allowances to tenants (direct payment) or to landlords (landlord payment).

However, four publications relevant to the UK experience do explore the issue of direct payment of Housing Benefit to tenants. In 2002, London and Quadrant Housing Trust undertook a one year trial of direct payment involving 800 tenants. The findings indicated that rent arrears more than doubled from three per cent to seven per cent over the course of the trial, peaking at nine per cent (Donaldson, Citation2004). This pilot also identified additional transactional costs associated with direct payment, with further costs accruing as a result of ‘additional staff time pursuing individual residents for their arrears’ (Donaldson, Citation2004, p. 21). Green, Reeve, Robinson, and Sanderson (Citation2015) undertook an online survey of social housing landlords' readiness for the introduction of Universal Credit, including direct payment of Housing Benefit. They found that landlords believed the Universal Credit would result in an increase in arrears (98% thought that this would be the case); a change in relationships between landlord and tenant (96%); more resources being devoted to rent collection and rent recovery (95%); and more staff being employed (75%).

Power, Provan, Herden, and Serle (Citation2014) explored the likely impact of welfare reform on the poorest residents in the most deprived areas in the country. This study included surveys and focus groups with housing associations and tenants. They reported that welfare reform, including direct payment through Universal Credit, is likely to create greater interdependency between landlords and tenants. At the time of the research, tenant awareness of Universal Credit was low. However, when explained, two thirds thought that a direct monthly payment of Housing Benefit to the tenant was a bad idea. More than half of tenants surveyed said they would find the monthly payment difficult to manage. They foresaw a number of issues: worries about unexpected calls on funds and the temptation to cover more immediate costs than rent; arrears caused by adjustment onto the new system; difficulties in setting up Direct Debits or alternative payment methods; and increased levels of stress and anxiety resulting from the new system being too complicated. Most tenants thought direct payment of Housing Benefit would create difficulties for landlords and would increase homelessness. The research also identified how social landlords were changing their approach in readiness for the roll out of Universal Credit by promoting bank accounts and credit unions, helping tenants to open accounts, developing money management skills, strengthening recovery teams and assisting tenants to build up credit on their rent accounts.

In the final study Irvine, Kemp, and Nice (Citation2007) conducted a detailed qualitative study of 82 Housing Benefit claimants renting from private and social housing landlords in three local authority areas in England. The aim was to examine claimants’ understanding, attitude and experiences of the two different systems of paying Housing Benefit: to the tenant or to the landlord. Of tenants interviewed 58 were on landlord payment and 24 on tenant payment. The research team found that, while most of the participants had a preference for landlord payment, many did not think it would be particularly difficult to adjust to tenant payment (Irvine et al., Citation2007, p. 10). Most tenants also stated that they prioritised paying their rent over other household bills.

This study also identified two types of tenants whose approach to money management suggested they were more likely, or who said they were more likely, to get into rent arrears if they were on direct payment. The first group was ‘chaotic’ money managers, who were ‘found only among young people and lone parents and had difficult financial situations and many of them said they could be forgetful about paying bills and/or were generally careless with money’(Irvine et al., Citation2007,p. 2). The second group was ‘flexible’ money managers. This group was identified ‘less rigid than “ordered” money managers’ (who ‘preferred payment methods that they felt provided control over when and how much they paid, such as cash, cheques, and internet banking’) (Irvine et al., Citation2007, p. 2).

The next section introduces the DPDPs.

The direct payment demonstration projects

In advance of the roll out of Universal Credit, the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) created six DPDPs to test the direct payment of Housing Benefit for social housing tenants, with the findings to inform Universal Credit development. The six DPDPs—which involved 12 social housing landlords—were Oxford, Shropshire, Southwark, Wakefield (all in England), Torfaen (Wales) and Edinburgh (Scotland). These areas were selected by the DWP because they varied in terms of participating landlord types and different geographies covered.

The Demonstration Projects went live over the summer of 2012, with the first direct payments being made in June 2012. In line with Universal Credit, only working age claimants were eligible for direct payment, with the plan for 2000 tenants to be included in each Demonstration Project. Tenants were moved onto the programme in a phased approach. This reflected complexities in engaging tenants in the programme and the preparedness of tenants to move onto direct payment. The programme concluded in December 2013, by which time 7426 tenants had received a direct payment.

Tenants on the DPDP programme experienced two main changes in how their Housing Benefit was administered. Direct payment tenants received their Housing Benefit payment every four weeks (broadly in-line with monthly payments under Universal Credit), as opposed to weekly or fortnightly as per their previous arrangements. They were then responsible for paying their full rent to their landlord. Tenants encountering difficulties with direct payment and who fell into arrears were switched back to landlord payment. This replicated the APA system available in the Universal Credit environment.

Before testing the hypothesis set out earlier the next section describes the evidence base and outcome measures used in the analysis.

Methods

Evidence base

A bespoke longitudinal dataset collated as part of the DWP funded evaluation of the DPDPs forms the evidence base for this paper. The 12 DPDP landlords provided individual tenant level data for tenants who received a direct payment of Housing Benefit between June 2012 and December 2013. The range of data collated included: project monitoring data, such as whether a tenant had reached a trigger point (an agreed level of additional rent arrears) and who had been switched back; detailed rent account information on charges and payments; administrative Housing Benefit data collected for the Single Housing Benefit Extract, a monthly electronic scan of Housing Benefit claimant level data direct from local authority computer systems; and other landlord held data on the characteristics and circumstances of tenants for example age, household composition, work status and tenancy status.

The direct payment sample included tenants for whom the projects provided both rent account and Housing Benefit data in at least one rent account period, and for whom there was some activity on their rent account. Tenants with no experience of direct payment were not included in the analysis. Data were provided for 7252 tenants who had been paid their Housing Benefit direct, which represented 98% of the total number recorded by DWP going onto the programme.

To assess the net additional impact of direct payment with a high level of scientific rigor (Farrington et al., Citation2002), equivalent data were also collated for a comparator sample of social housing tenants who were on Housing Benefit, but who were not considered for inclusion in the Demonstration Projects. In total, data for 9111 tenants were provided from the wider tenant bases of five social landlords. This comprised four Demonstration Project landlords (Oxford City Council, Southwark Council, Bron Afon in Torfaen and Wakefield and District Housing) as well as Port of Leith, which was not part of the Demonstration Project, but which provided data on their tenants to form a comparator for the Edinburgh project (Dunedin Canmore). It was not possible to obtain comparator data from Shropshire. A comparator sample for that Demonstration Project was therefore derived from samples provided by other Demonstration Projects.

Propensity score matching was used to derive the final comparator sample for the analysis. All DPDP tenants were matched to their nearest neighbour within the comparator sample based on 12 attributes. The 4941 comparator tenants who were a nearest neighbour went into the final comparator sample. Weights were applied if a comparator tenant was a nearest neighbour to more than one DPDP tenant. The resultant comparator sample population was found to be very similar over a range of key socio-demographic characteristics, including baseline rent account position, full or partial Housing Benefit receipt, household composition and employment status.

There are a number of strengths to the evidence base, including it contained: nearly all tenants who went onto direct payment; a wide and detailed range of administrative rent account and Housing Benefit level data, which are assumed to be more accurate than self-reported responses; data covering time periods before and after tenants went onto direct payment; equivalent data for a quasi-experimental matched comparator sample of tenants, none of whom received a direct payment. The evidence base allowed a robust assessment of the impact with a high level of scientific rigor, achieving level 4 on the Maryland Scale of Scientific Methods (Farrington et al., Citation2002).

However, it is important to acknowledge limitations which affect the generalisability and robustness of the findings. In particular the landlords and tenants taking part in the DPDP were not randomly selected and are drawn from just six areas of the UK. The areas were chosen because they covered different landlord types and tenants were ‘typical’ of the participating landlords’ wider tenant base (i.e. not their most or least ‘able’ tenants). It is therefore not the case that the DPDP areas, their landlords or the tenants are proportionally representative of their respective populations in the UK. This means there are likely to be biases which affect the representativeness of the sample to the overall population who are eligible for Universal Credit. Therefore the broad conclusion and lessons developed in this paper are able to inform the likely impact of direct payment of Housing benefit within Universal Credit. However, the precise quantitative impact will be affected by these biases as well as the wider, changing, housing and welfare policy environment. It is also likely that the relatively low number of tenants participating in the Demonstration Project within each landlord's tenant base enabled landlords to apply more resources to preventative and reactive debt management than would be possible if Universal Credit had been fully rolled out.

It should also be pointed out that this analysis is not an assessment of the impact of Universal Credit, only the direct payment of Housing Benefit to tenants. There are features of the full introduction of Universal Credit which may limit the impact of direct payment on rent collection/arrears. For example, the larger benefit payment may mean tenants are less likely to suffer from failed Direct Debits due to insufficient funds. Similarly other features may increase the impact on rent payment, such as the need to balance a greater proportion of their household income over a longer—monthly—timeframe.

Outcome measures

Having outlined the evidence base the following sets out the key outcome measures that have been used to address the research question set out in the introduction. In common with how social housing landlords assess rent payment, this paper focuses on two outcome measures: rent arrears and rent collection rates. Rent arrears have been calculated by comparing the amount that a tenant's rent account balance in is debit (arrears) against their annualised rent, to give a percentage. So for example if a tenant was £500 in deficit and their annualised rent was £18,000 then their rent arrears rate would be 2.8%. A rent arrears rate can be calculated across a wider tenant base by expressing the sum of debits as a percentage of the summed annual rent roll.

Rent collection rates have been calculated by assessing the proportion of rent paid over a given period. In order to standardise this measurement over time and to allow temporal analysis ‘rent payment periods’ were created. These refer to four-week periods, or a month in the case of Edinburgh, over which landlords would expect tenant rent accounts to balance, if a tenant was up to date with their rent. Payment period 1 therefore refers to the rent cycle (i.e. the period for which rent is due) following a first direct payment of Housing Benefit, regardless of the calendar month in which that payment was made. Payment period 2 refers to the rent cycle following the second direct payment of Housing Benefit and so on. A rent collection rate can then be calculated for each rent payment period, or over a combination of rent payment periods. In this context:

a rent collection rate of one implies the value of rent collected equated the amount of rent due. So if a tenant owed £100 worth of additional rent in a period s/he had paid £100

a rent collection rate greater than one implies a tenant paid more than the additional rent owed; for example a rent collection rate of 1.2 suggests a tenant paid £1.20 for every £1 of additional rent owed

a rent collection rate less than one implies a tenant did not pay all of his/her rent owed; for example a rent collection rate of 0.8 suggests a tenant paid £0.80 for every £1 of additional rent owed.

Results and analysis

This section tests the hypothesis that direct payment of Housing Benefit will have a negative effect on rent payment: reduced rent collection and increased arrears. It begins with a descriptive assessment of the main outcome variables before using statistical modelling techniques to quantify the net additional impact of direct payment of Housing Benefit to tenants.

Just over £33,072,000 in rent was charged to DPDP tenants in rent periods when they received their Housing Benefit paid direct. In return £31,331,000 was collected from the same tenants giving a rent collection rate of 94.7%. The collection rate for tenants in the comparator sample, none of whom received direct payment, was 99.1% of their rent due. Therefore, tenants who were paid their Housing Benefit direct collectively paid on average 4.4% points less of their rent due over the Demonstration Project. Based on the rent due from direct payment tenants this equates to £1,448,000 less rent collected.

Considering rent arrears rates reveals a similar picture. The collective rent arrears rate for tenants at the point when they started receiving direct payment of Housing Benefit was 2.3%. This increased to 5.7%, an increase of just under 150% over the rent account periods when tenants received direct payment. Rent arrears rates also increased for tenants in the comparator sample. However, this increase was considerable lower: 50% from 2.4% to 3.5%. If the rent arrears rate for direct payment tenants had only increased by this level just under £1,132,000 less arrears would have been accumulated onto tenants' rent accounts.

The second stage of analysis used Generalised Estimating Equations (GEEs) to estimate the net additional impact of direct payment over time. This used longitudinal rent period data covering periods when DPDP tenants were, and were not, on direct payment and compared rent collection rates against comparator tenants who never experienced direct payment. Within these models there were dummies to control for Housing Benefit destination (whether it was paid to the tenant or the landlord), whether the tenant was subject to Removal of the Spare Room Subsidy, whether the tenant was subject to the Benefit Cap, and whether the tenant had been switched back onto landlord payment. The results () reveal statistical evidence, at a 0.05 level, of an net additional effect of receiving rent by direct payment on rent collection rates in a given rent payment period. On average 5.5% points less rent per rent payment period was collected from tenants who were paid their rent direct: equating to £5.50 less rent paid per £100 of rent charged.

Table 1. The net additional impact of direct payment using GEE.

Discussion

The empirical evidence presented above points to direct payment having a negative net additional impact on rent collection and arrears. This has important implications for landlord finances and the underlying principles of direct payment that tenants are able to successfully take responsibility for paying their rent. It also brings into question why Universal Credit should contain a housing element. However this reductionist view needs to be set against more nuanced analysis that views a tenant's transfer to direct payment as a process. This analysis has been informed by NPT and explores three themes: ‘is the impact consistent over time?’; ‘to what extent is the negative impact due to tenants who switch back within the first few periods on direct payment?’; and ‘do tenant's payments follow patterns?’

Is the impact consistent over time?

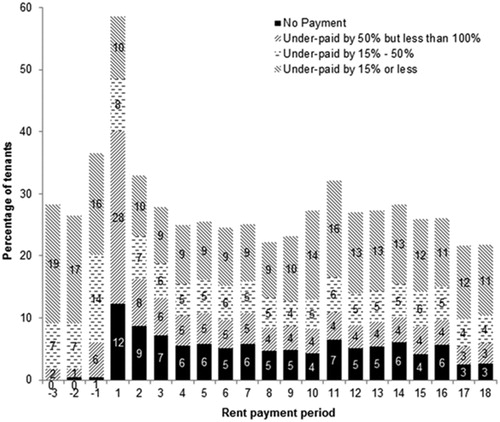

This theme of analysis seeks to understand whether tenants increase their financial capability over time, which in turn translates to a smaller impact of direct payment on P (EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) ). shows a marked improvement in rent collection rates after the first few direct payment of Housing Benefit. In the first three rent payment periods (a period of approximately 12 weeks) after transferring onto direct payment, tenants paid on average 15.7% points less rent per payment period than the quasi-experimental comparator group who had their Housing Benefit paid direct to their landlord. In payment periods 4–6 the impact reduced to 2.8% points less rent. The net additional impact was lower still in payment periods 7–9: 1.3% points less rent collected. In the remaining three 12 week periods the impact ranged between 2.1 and 3.5% points less rent collected per payment period.

Table 2. The net additional impact of direct payment over time using GEE.

This suggests that the long run impact of direct payment will be less than the 5.5% points identified in the results section. Potentially it may be as low as 2% points less rent collected per rent period. The reduction in the negative impact of direct payment over time is likely to have resulted from tenants quickly adapting to the new system and the effects of the switchback mechanism removing tenants who were unable to adjust.

To what extent is the negative impact due to tenants who switch back within the first few periods on direct payment?

Reflecting Universal Credit thinking at that time, the initial support assessment process used by the Demonstration Projects to identify tenants' readiness for direct payment was only designed to safeguard a small proportion of tenants with the most complex needs. The following analysis removes those tenants who switched back in their first three payment periods as a proxy for those who should not have gone onto direct payment. Repeating the GEE models with this sub group of direct payment tenants reveals that on average, tenants paid 5.0% points less rent per payment period than the comparator group who had their rent paid direct to their landlord. This compares with 5.5% points if early switchbacks were included.

This suggests a more effective initial support assessment could have a statistically significant effect on limiting the impact of direct payment. However, most of the improvement over time (identified in the previous subsection) can be attributed to tenants adapting to the new payment system.

Does tenant's payment follow patterns?

This is addressed in the following two themes of discussion:

Themes 1: Is the impact driven by tenants accruing larger arrears and/or more tenants accruing arrears?

Analysis of the proportion of tenants underpaying over time, shows a marked spike in the first payment period (). Fifty-nine per cent of direct payment tenants underpaid or did not pay their rent following their first direct payment of Housing Benefit, compared with only 26% of tenants in the second payment period before moving onto direct payment. The proportion of tenants who underpaid or did not pay quickly returned to baseline levels in payment periods two to four. In some payment periods the proportion of tenants who underpaid their rent was lower than before the introduction of direct payment. However, it is important to note here that although the overall proportion of tenants underpaying or not-paying their rent changed little when direct payment was introduced (notwithstanding the spike in payment period 1), the composition of underpayment did change. In particular, the proportion of tenants who failed to pay 50 to 100% of their rent was considerably higher under direct payment. This explains how the total value of arrears increased even though the overall proportion of tenants underpaying changed little after period 1. This is not surprising: pre-direct payment only those eligible for a small amount of Housing Benefit could underpay significantly and no tenants could fail to pay altogether other than through administrative error.

Theme 2: Is underpayment consistent or erratic?

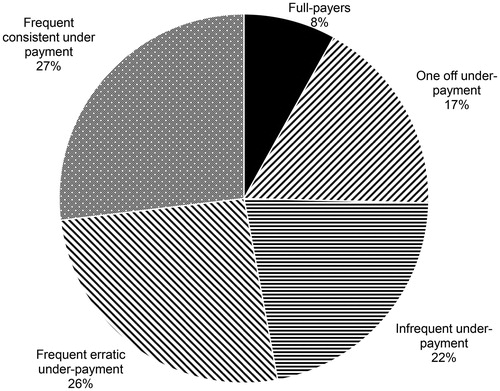

Examining rent payment patterns of 5,031 tenants who received at least seven direct payments of Housing Benefit reveals that tenants were more likely to underpay erratically than more consistently. To aid the analysis payment patterns have been simplified into the following, atheoretical, five group classification:

full payment: no underpayment made while in receipt of direct payment (eight per cent of tenants who received at least seven direct payments)

one-off underpayment: only one underpayment made while in receipt of direct payment (17% of tenants who received at least seven direct payments)

frequent, consistent underpayment: at least three underpayments, made consecutively, while in receipt of direct payment (27% of tenants who received at least seven direct payments)

frequent, erratic underpayment: at least three underpayments for tenants who received seven to nine direct payments and at least four underpayments for those who received ten or more direct payments, with no more than two underpayments made consecutively (26% of tenants who received at least seven direct payments)

infrequent underpayment: two or fewer underpayments for tenants who received seven to nine direct payments, and three or fewer underpayments for those who received ten or more direct payments, with no more than two made consecutively (22% of tenants who received at least seven direct payments)

Of the four underpayment groups, three could be described as ‘erratic’ underpayers: those underpaying once, those underpaying frequently but erratically, and those underpaying infrequently. In total 27% of tenants in the DPDP who received at least seven direct payments were consistent underpayers (29% of all tenants who had an underpayment) and 65% were erratic underpayers (71% of tenants who had an underpayment) (). This suggests while consistent underpayment is certainly a feature of tenants' payment patterns, it is not as common as erratic underpayment. Consistent underpayment was particularly common early in a tenant’s direct payment career, which could suggest teething problems during the transition period. For example, approximately one third of all persistent underpayers (nine per cent of all tenants) made the first of several consecutive underpayments in one of their first three payment period.

Conclusions

The introduction of Universal Credit in the UK sees six separate benefits combined into one single monthly benefit payment paid direct to the claimant. This represents a major change for recipients of Housing Benefit in the social rented sector who previously had their benefit paid direct to their landlord. Despite differences between welfare states in relation to whether the claimant or the landlord receives the Housing Allowance payment, the evidence base on the impact of direct payment on rent collection remains underdeveloped.

In preparation for the introduction of Universal Credit the DWP funded six DPDPs to provide learning for the implementation of direct payment of Housing Benefit. Using a bespoke dataset created as part of the DWP funded evaluation of the Demonstration Projects this paper has explored the effects paying social housing tenants their Housing Benefit is likely to have on rent collection and arrears. The results have supported the hypothesis that direct payment of Housing Benefit to tenants will have a negative effect on both rent collection and arrears, with evidence estimating that the proportion of rent collected—‘P’ in EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) —reduced by 5.5% points. Despite this overall negative finding more positive evidence emerged by taking a more nuanced assessment of the impact. This analysis was informed by NPT, which provides a framework to evaluate impact supposing the introduction of direct payment is a process that needs to be embedded into day-to-day practice. For instance the longer term impact was estimated to be smaller, approximately 2% points. This supports Irvine et al.’s (Citation2007) finding that tenants would be able to quickly adapt to the new system and become more responsible for paying their rent.

These findings make an important contribution to the major theoretical debate on the effectiveness of using welfare policy to encourage—or ‘nudge’—responsibilisation, which has become the dominant discourse since the mid-late 1990's. For most tenants—based on rent recollection and arrears—the normalisation process of reconnecting claimants to their rent and giving them responsibility for paying their rent was successful. However, despite the majority of tenants being able to manage their rent payment, attention should be given to the residual negative consequences that direct payment will have on tenants and landlords. In particular this analysis, which has been informed by NPT, has identified two main challenges facing landlords, which themselves emerge from Wright's two basic models of active welfare recipients. First, how to limit the magnitude of the initial impact as tenants transfer onto direct payment. This may be achieved by effectively triaging tenants to filter out those—embodied by what Wright calls the dominant model—who are too vulnerable, too politically sensitive, or who lack the capacity to take ‘responsibility’ for paying their rent. A challenge that is likely to repeat in other context where policy has been implemented to promote responsibilisation (Taylor-Gooby, Citation2013). Landlords will then need to target support on tenants as they transfer onto direct payment by enhancing their financial capability and their understanding of what is required to be a ‘responsible tenant’. This support should include training on setting up payment mechanisms, such as direct debits, an approach which is shown to promote successful payment (Department for Work and Pensions, Citation2014b).

Second, even with more effective triage and support, the analysis has shown landlords will be exposed to a cocktail of an increased number of tenants accruing arrears, an increase in the maximum value of arrears claimants can accrue in a given rent period, and unpredictability as to which tenants will accrue arrears. This relates to Wright's alternative model of active welfare recipients, whereby the prevailing economic and power structures hinder tenants' ability to adjust fully to direct payment. The net result will mean landlords have to face up to fluidity in their cash flow as tenants move between arrears and credit. In addition, there will be increased demand on landlords organisational resources generated by arrears and through increased contact from tenants. Understanding different strategies that landlords choose to react to these challenges deserves further research. It is likely that direct payment of Housing Benefit will intensify tensions within landlords about balancing their social purpose against a trend towards greater financialisation.

Acknowledgements

The author was part of the consortium undertaking the national evaluation of Direct Payment Demonstration Projects programme funded by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). Thanks are due to the DWP for funding the 2012-2015 evaluation. In particular thanks are due to Claire Frew and Ailsa Redhouse. The views expressed here are those of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect those of DWP. Thanks are also due to all members of the consortium: Paul Hickman and Kesia Reeve at Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research at Sheffield Hallam University; Peter Kemp at University of Oxford; and Ipsos MORI.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Department for Work and Pensions. (2010a). 21st century welfare CM 7913. London: The Stationery Office.

- Department for Work and Pensions. (2010b). Universal credit: Welfare that works. London: The Stationery Office.

- Department for Work and Pensions. (2012). Welfare reform act 2012. London: The Stationery Office.

- Department for Work and Pensions. (2014a). Direct payment demonstration projects: The longitudinal survey of tenants. London: Department for Work and Pensions.

- Department for Work and Pensions. (2014b). Direct payment demonstration projects: Key findings of the 18 months' rent account analysis exercise. London: Department for Work and Pensions.

- Donaldson, M. (2004). Lost benefits. Inside housing, 27 February 2004, p. 21.

- Elwyn, G., Légaré, F., van der Weijden, T., Edwards, A., & May, C. (2008). Arduous implementation: Does the normalisation process model explain why it's so difficult to embed decision support technologies for patients in routine clinical practice. Implementation Science, 3(57).

- Farrington, D.P., Gottfredson, D.C., Sherman, L.W., & Welsh, B.C. (2002). The Maryland scientific methods scale. In L. W. Sherman, D. P. Farrington, B. C. Welsh, & D. L. MacKenzie (Eds.), Evidence-based crime prevention (pp. 13–21). London: Routledge.

- Fenton, A. (2011). Housing benefit reform and the spatial segregation of low-income households in London. Cambridge: The Cambridge Centre for Housing and Planning Research, University of Cambridge.

- Ferrari, E. (2015). The social value of housing in straitened times: The view from England. Housing Studies, 30(4), 514–534. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2013.873117

- Flint, J. (2004). Reconfiguring agency and responsibility in social housing governance in Scotland. Urban Studies, 41(1), 151–172. doi: 10.1080/0042098032000155722

- Gibb, K. (1995). A housing allowance for the UK? Preconditions for an income‐related housing subsidy. Housing Studies, 10(4), 517–532. doi: 10.1080/02673039508720835

- Gibbons, S., & Manning, A. (2006). The incidence of UK housing benefit: Evidence from the 1990s reforms. Journal of Public Economics, 90(4-5), 799–822. doi: 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2005.01.002

- Gilbert, N. (2002). Transformation of the welfare state: The silent surrender of public responsibility. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Green, S., Reeve, K., Robinson, D., & Sanderson, E. (2015). Direct payment of housing benefit: Are social landlords ready? Sheffield: CRESR, Sheffield Hallam University.

- Haffner, M., & Boelhouwer, P. (2006). Housing allowances and economic efficiency. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 30(4), 944–959. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2006.00699.x

- Hickman, P., Kemp, P., Reeve, K., & Wilson, I. (2017). The impact of the direct payment of housing benefit: Evidence from Great Britain. Housing Studies, 32(8), 1105–1126. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2017.1301401

- Hills, J. (1991). Distributional effects of housing subsidies in the United Kingdom. Journal of Public Economics, 44(3), 321–352. doi: 10.1016/0047-2727(91)90018-W

- Howenstine, E.J. (1986). Housing vouchers: A comparative international analysis. New Brunswick, NJ: Centre for Urban Policy Research, Rutgers University.

- Institute for Public Policy Research (IPPR). (2010). Universal credit white paper: Response of IPPR. Manchester, NH: IPPR.

- Irvine, A., Kemp, P.A., & Nice, K. (2007). Direct payment of housing benefit: What do claimants think? Coventry: Chartered Institute of Housing.

- Johnson, P. (2015). Our burgeoning housing benefit bill exposes flaws in housing policy and the tax system. The Times, September 29.

- Kemp, P. (1998). Housing benefit: Time for reform. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Kemp, P. (2000). Housing benefit and welfare retrenchment in Britain. Journal of Social Policy, 29(2), 263–279. doi: 10.1017/S0047279400005912

- Kemp, P. (2007). Housing allowances in the advanced welfare states. In P. Kemp (Ed.) Housing allowances in comparative perspective. Bristol: The Policy Press.

- Kemp, P., Wilcox, S., & Rhodes, D. (2002). Housing benefit reform: Next steps. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Keohane, N., & Shorthouse, R. (2012). Sink or swim? The impact of the universal credit. London: Social Market Foundation.

- King, P. (1999). The reform of housing benefit. Economic Affairs, 19(3), 9–13. doi: 10.1111/1468-0270.00167

- Lister, R. (2004). Poverty. Cambridge: Polity

- May, C., & Finch, T. (2009). Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: An outline of normalization theory. Sociology, 43(3), 535–554. doi: 10.1177/0038038509103208

- Money Advice Service. (2015). Financial capability in the UK 2015. London: Money Advice Service.

- O’Malley, P. (2009). Responsibilization. In A. Wakefield & J. Flemming (Eds.), Sage dictionary of policing. London: Sage.

- Peeters, R. (2013). Responsibilisation on government's terms: New welfare and the governance of responsibility and solidarity. Social Policy and Society, 12(04), 583–595. doi: 10.1017/S1474746413000018

- Phillips, D. (2013). Government spending on benefits and state pensions in Scotland: Current patterns and future issues. London: Institute for Fiscal Studies.

- Power, A., Provan, B., Herden, E., & Serle, N. (2014). The impact of welfare reform on social landlords and Tenants. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Priemus, H., & Kemp, P. (2004). The present and future of income-related housing support: Debates in Britain and the Netherlands. Housing Studies, 19(4), 653–668. doi: 10.1080/0267303042000222016

- Priemus, H., Kemp, P.A., & Varady, D. (2005). Housing vouchers in the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands: Current issues and future perspectives. Housing Policy Debate, 16(3-4), 575–609. doi: 10.1080/10511482.2005.9521556

- Raco, M. (2009). From expectations to aspirations: State modernisation, urban policy, and the existential politics of welfare in the UK. Political Geography, 28(7), 436–444. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2009.10.009

- Social Security and Housing Benefits Act. (1982). Public General Acts. London: HMSO.

- Shore, C., & Wright, S. (2011). Conceptualising policy: Technologies of governance and the politics of visibility. In C. Shore, S. Wright, & D. Però, Policy worlds: Anthropology and the analysis of contemporary power (pp. 1–26). Oxford and New York: Berghahn Books

- Stephens, M. (2005). An assessment of the British housing benefit system. International Journal of Housing Policy, 5(2), 111–129. doi: 10.1080/14616710500162582

- Taylor-Gooby, P. (2013). Why do people stigmatise the poor at a time of rapidly increasing inequality, and what can be done about it? The Political Quarterly, 84(1), 31–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-923X.2013.02435.x

- Trnka, S., & Trundle, C. (2014). Competing responsibilities: Moving beyond neoliberal responsibilisation. Anthropological Forum, 24(2), 136–153. doi: 10.1080/00664677.2013.879051

- Wilcox, S., & Perry, J. (2014). UK housing review 2014. Coventry: Chartered Institute of Housing.

- World Bank. (2013). Making sense of financial capability surveys around the world: A review of existing financial capability and literacy measurement instruments. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Wright, S. (2016). Conceptualising the active welfare subject: welfare reform in discourse, policy and lived experience. Policy & Politics, 44(2), 235–252. doi: 10.1332/030557314X13904856745154