Abstract

Academic and popular debates around the movement of financial capital tied to the residential housing market in global cities such as London, tend to focus on the super-rich, wealth management and pension funds. While such debates acknowledge that these large scale capital flows influence socioeconomic structures of the destination cities, relatively little is known about how middle-class money flows across national and city boundaries, and between key intermediaries. This article aims to address these empirical and conceptual lacunae by examining the practices of middle-class Hong Kong investors, many of whom have been investing in properties worldwide since the early 1990s. Using ethnographic research and interviews carried out in Hong Kong and the UK, this article sheds light on the investment activity of two groups of middle-class investors: the wealthy middle-class and the aspiring middle-class. The article shows how a wealthy city-state like Hong Kong, with a laissez-faire economy and established international real estate sector, has enabled the outflow of capital to the global housing market. The article also highlights the ability of ethnographic studies to help us look inside processes of transnational housing investment.

Introduction

Popular and academic debates on housing in London have focussed on the super-rich (e.g., Atkinson, Citation2016; Hay, Citation2013; Hay & Muller, Citation2012) in relation to their consumption patterns, economic power and political influence (Atkinson, Parker, & Burrows, Citation2017). As such, properties are seen as safe havens to park assets (Fernandez, Hofman, & Aalbers, Citation2016) and generate rental income that outgrows inflation, in comparison with the low interest rates offered on saving accounts and the low return on investment in financial products (Ho & Atkinson, Citation2018). There is evidence that middle-class1 Hong Kong investors have been investing in London’s core property market since the beginning of the 1990s (Ho & Atkinson, Citation2018). While the first wave of Hong Kong investors in the 1990s bought properties in London mostly for their own use, the second and third waves of investors who emerged between 2000 and 2009 are interested in financial returns, whether for short-term speculation or long-term rental return. Nonetheless, the global real estates are regarded as an asset class which investors can ‘diversify their investment portfolios’ (Rogers & Koh, Citation2017, p. 1).

Although there are super-rich buyers from Hong Kong investing in residential properties in London, there is evidence that middle-class investors are mostly interested in buying properties in order to rent them out as a means of generating income in the buy-to-let market (Ho & Atkinson, Citation2018). Specifically, the quote ‘5980 miles to my second home’ used in the title, was given by a participant and refers to the flight distance in miles between Hong Kong and London. It illustrates how these second homes are solely bought for investment purposes which they may never visit. This phenomenon is referenced in the newly-coined term ‘lights-out London’ which captures the under-occupation of luxury properties in the city. The scale of such investment activity has become significant. By 2012 around one in six new residential properties sold in central London was bought by Hong Kong investors (Knight Frank, Citation2013). Significantly, in 2016, an estimated 514,000 Hongkongers invested in property outside of Hong Kong (Zheng, 2017) which accounted for 7% of Hong Kong’s population at around 7.4 million (Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong, Citation2018), and this figure continues to rise.

Nevertheless, this alternative narrative of the middle-class investment for understanding the housing market in London has yet to be widely acknowledged, and little is known about the operation of the real estate businesses and key actor intermediaries responsible for selling properties to Hongkongers. In addition, this article aims to contribute to productive methodological approaches for researching real estate investment behaviours. This article aims to explore who Hong Kong’s middle-class investors are and investigates how they buy properties in London (and more recently, in other UK cities including Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham). Analysis of ethnographic research, interviews and marketing materials carried out in Hong Kong and the UK between 2015 and 2018 traces the geographies of real estate investment from the initial processes of investors’ choices of off-plan developments at property fairs in Hong Kong to the point at which the first rental income is received. The aims of the article are first, to make a theoretical contribution to the understanding of the role of the Hong Kong middle-classes in transnational property investment in the UK; and secondly, make a methodological contribution to how research into real estate processes can be carried out.

The article is divided into four sections. The next section explores the current debates about global housing investment, the Hong Kong middle-classes and the reasons why Hongkongers have long been interested in investing in real estate. The article then discusses the methods and approach used in this research, including the importance of having local knowledge and relevant language skills. Here, the aim is to make a methodological contribution on how to approach real estate research at the practical level. It then explores the empirical findings, challenges the current homogeneous understanding of the Hong Kong middle-class (Lui, Citation2003), and introduces two groups of middle-classes: the wealthy and aspiring middle-class, as well as how and why they buy overseas properties. The article concludes with a discussion of the theoretical and methodological approach to transnational real estate investment between Hong Kong and the UK, and highlights how financially-literate middle-class Hongkongers are having a significant impact on the international real estate sector.

International real estate investment and Hong Kong society

The current narrative of the residential real estate investment in London for the super-rich tends to focus on how they buy prime and super-prime properties and leave them unoccupied and under-occupied. As such, global cities including London attract transnational investors buying prime properties for investment purposes (Atkinson, Burrows, & Rhodes, Citation2016; Atkinson et al., Citation2017; Paris, Citation2013), and cash investors regard residential real estate in London and New York ‘as an investment rather than as a primary residence’ (Fernandez et al., Citation2016, p. 2447). Other super-rich buyers look for safe havens to park their assets and see their wealth grow beyond their own national boundaries (Pow, Citation2017, p. 70). Consequently, external investments in domestic real estate markets have become a geopolitical issue between nation states (Büdenbender & Golubchikov, Citation2017). Subsequently, evidence shows that the flow of capital into some global housing markets has been negatively perceived. For instance, in the case of Sydney’s suburban residential property market, 50% of the residents in the Greater Sydney Region who took part in a survey in 2015 reported that they would not welcome Chinese foreign investment (Rogers, Wong, & Nelson, Citation2017). From a political economy perspective, global elites can influence housing policy and profit from real estate (Doling & Ronald, Citation2014).

However, while the narrative of the super-rich buying luxury properties continues, an emerging direction of research illustrates that middle-class investors from Hong Kong have been actively investing in London’s core housing market since the 1990s for two key reasons: investment and political uncertainties (Ho & Atkinson, Citation2018). First, demand for housing in global cities continues to grow and foreign properties can be used as investment vehicles to guarantee long-term financial security at a time when investment products offered on global financial markets no longer promise stable returns. Second, with the uncertain political conditions induced by the mainland Chinese government, Hongkongers see foreign home ownership as a kind of insurance option, should they feel the need to leave the previously British-administered city-state. In contrast, mainland Chinese investors buy overseas properties in countries such as Australia because of China’s policy on limiting domestic homeownership and lifestyle immigration aspirations (Liu & Gurran, Citation2017). Nevertheless, findings from this article will illustrate that while the super-rich will occasionally use their properties as second homes, the Hong Kong middle-classes may never visit or live in their properties. To develop this perspective, the following section unpacks the concept of the Hong Kong middle-class (Lui, Citation2003).

The middle-classes in Western Europe including the UK are generally defined by levels of education, occupation, cultural interests and social groupings (Savage et al., Citation2013), but a middle-class in these terms only began to emerge in Hong Kong with the advent of industrialisation in the mid-1960s (Lui, Citation2003). With economic modernisation, the definition of the middle-class in Hong Kong was primarily based on wealth (Ho & Atkinson, Citation2018).

Only in the last two decades when the middle-classes have become more established, did they also begin to accumulate cultural capital. For example, parents invest in their children’s education in Hong Kong through after-school activities (Karsten, Citation2015, p. 558) or by sending them to countries such as Britain and Canada (Waters, Citation2006, Citation2010). Moreover, Hong Kong is not a welfare state and this has contributed to the middle-classes investing in assets in order to achieve financial security. While the standard of education and healthcare in Hong Kong is among the highest in the world, unemployment benefits and government pensions are insignificant. The middle-classes have to financially support, not only themselves but their children and sometimes their parents. In order to achieve this, some middle-class investors choose to reduce levels of consumption in order to make buy-to-let investments for future financial security (Ho & Atkinson, Citation2018).

In contrast to the super-rich in the West whose wealth tends to be created through industries and technologies, tycoons in Hong Kong have traditionally focused on land acquisition as well as commercial and residential real estate development (Forrest, Wissink, & Koh, Citation2016; Fung & Forrest, Citation2002; Haila, Citation2000; Lui & Wong, Citation1994; Poon, Citation2011; Smart & Lee, Citation2003). For example, Li Ka-shing, one of the wealthiest self-made tycoons began in plastic manufacturing in the 1950s, and moved into real estate because of the exceptionally high returns. When the Open Door policy in China was introduced by Deng Xiaoping in 1978, the then colonial Hong Kong which was still governed by Britain remained the only gateway to the mainland from the rest of the world which allowed many Hong Kong entrepreneurs to invest in various industries as well as commercial and residential real estate development projects in the Pearl River Delta (PRD). Property development and speculation begun by the self-made billionaires in post-Second World War Hong Kong became the foundation of wealth-creation that inspired many local citizens to invest. Between 1970s and the 2010s, residential apartments were affordable for those who had stable middle-class incomes in Hong Kong. However, since an average price of a property in Hong Kong increased to almost 20 times the median household income by 2018 (Cox, 2018), home ownership is now out of reach for many. Consequently, Hongkongers have sought properties in distant markets such as Japan and Thailand for primary home ownership with the aim of cashing out in the near future and buying an apartment in Hong Kong.

In addition, home ownership is regarded as a life-goal in Hong Kong and it would be almost unthinkable for a couple to marry and begin a family without having purchased a property. For Hongkongers, home ownership can be understood as a form of social, physical and financial ‘ontological security’ (Dupuis & Thorns, Citation1998; Saunders, Citation1986, Citation1990).

The city-state saw its wealthiest period from the late 1980s to 1997 when Hong Kong was returned to China, and many citizens had paid off their first mortgages in this time. While some were considering buying another local property as a form of financial investment, others sought second home ownership elsewhere, mainly because having a property outside Hong Kong would act as a safeguard against the political uncertainty induced by the 1997 handover. Therefore, it can be argued that the notion of ontological security goes beyond national borders: ‘home ownership shows the resourcefulness of the middle class’ (Lui, Citation2003, p. 171) in Hong Kong for whom property ownership became the financial foundation that made wealth creation possible (Lui, Citation1995). Nevertheless, this section highlights why academic research needs to focus not only on the super-rich but also the Hong Kong middle-classes in order to understand the housing market in the UK.

Research approach

The research approach for this article was based on following the flow of money drawing on qualitative data collected in both Hong Kong and the UK between 2015 and 2018. A similar approach was taken by Harrington (Citation2016) who spent two years training as a wealth manager and worked for 8 years with intermediaries in the industry in order to track the global movement of capital. Moreover, Ho (Citation2009) worked in the field as an investment banker and conducted ethnographic work in the corporate sector in the United States. To advance the methodological contribution, this article not only involved interviews in both English and Cantonese with various intermediaries, but the ethnographic elements such as attending property fairs and meetings at solicitors’ offices have enriched our understanding of the operations of the real estate sector that influences global housing markets.

Drawing on the researchers’ professional and private networks, the research began by recruiting Hongkongers who had bought homes in London, with whom semi-structured interviews were carried out. The researchers then travelled to Hong Kong and engaged with various actors involved in real estate transactions there. In total, 23 interviews involving 34 participants were conducted with real estate directors, investors, property developers, housing charity managers, regional government strategists and town planners in London, Aberdeen, Liverpool and Hong Kong (see ). Six visits to property fairs promoting UK properties were carried out in Hong Kong. One of the researchers was also invited to visit development sites, attend meetings involving property transactions and inspect documents concerning the properties. Observations were noted and marketing materials were collected online and at property fairs for analysis. For the conduct of this research, it was important to have language skills, in this case, English and Cantonese, and an understanding of Hong Kong and British culture when exploring marketing materials, dealing with participants and conducting ethnographies. When permission was granted by participants, interviews were recorded for transcription and translation, when required, and analysis. Otherwise, interview notes were taken instead.

Table 1. Summary of participants

In Hong Kong, it is considered to be culturally insensitive to ask participants about family background, income or wealth. However, since the investors who took part in this research had already invested in properties in the UK, it was possible to categorise them as one of two subgroups of the middle-class (see Buying and financing a property, and the theorisation of the Hong Kong middle-classes section) or the super-rich, based on the location of the properties owned and other financial information disclosed.

Researchers’ critique

The importance of researcher reflexivity has been widely acknowledged in the social sciences (e.g., Cupples & Kindon, Citation2003; England, Citation1994; Rose, Citation1997; Zhao, Citation2017) showing that the relationship between the researchers and participants has a direct effect on the characteristics of the data collected. Therefore, during the course of the fieldwork, the researchers were critical and reflective of their own positionalities and identities in relation to the interactions with participants and actors in the field. The following three examples highlight the challenges faced when conducting research in real estate investment.

First, the rapport between researchers and various actors in the field can affect how the researchers are perceived. When Researcher 1, a Hong Kong born male who grew up in England and Researcher 2, a white British male, visited a property fair in Hong Kong, a property agent believed that Researcher 1 was a potential investor interested in buying a property in London, and Researcher 2 was an English friend advising on such an investment. This was based on the fact that both researchers were discussing specific details about certain London neighbourhoods in English, and the conversation was picked up by the agent, who was an English male.

Second, the perceived power relationship between researchers also varies depending on given circumstances. On one occasion, both researchers entered a café located in Stanley, one of the most affluent parts of Hong Kong. When an American woman came to take orders, Researcher 2 asked ‘What is it like to live in this area?’ At this point, an assumption was made that Researcher 2 was about to relocate to Hong Kong as a British expatriate, and having Researcher 1 as a local agent advising on properties, schools and financial matters. This perception arose because Stanley was traditionally a neighbourhood populated by white expatriates during the colonial era.

Third, one of the biggest challenges the researchers faced was gaining access to participants from Hong Kong involved in the UK real estate market. The position of the researchers being insiders (Zhao, Citation2017), outsiders (Merriam et al., Citation2001), or perhaps somewhere in between (Kohl & McCutcheon, Citation2015; Zhao, Citation2017) had a significant influence on data collection and research outcome. In some cases, Researcher 1 being an ‘insider’ who, in Hong Kong, shared the same language, ethnic and cultural background helped to gain the trust of participants. On one occasion, Researcher 1 was invited by a shareholder of a property investment company to join a housewarming party with around a dozen of other shareholders, marking the completion of a central London apartment which had been remodelled from a poor condition to a luxury two-bedroom flat. The event was exclusively attended by Cantonese speakers. This highlights another form of real estate investment networks which an outsider would not have access to. The guests at this party had access to capital and the know-how which enabled them to invest in London properties on a much larger scale that allowed financial returns many times higher than off-plan apartments sold in Hong Kong. Nevertheless, when carrying out real estate research, conducting ethnographic studies in property fairs and interviews with various actors in the field can yield significant data as shown in the following empirical sections.

Inside the operation of transnational real estate investment

This section offers analyses of the ethnographic observations, interviews and marketing materials the researchers gathered on the operation of transnational real estate investment from Hong Kong to London, and more recently, to other parts of the UK. In modification of the current debate indicating that the global super-rich class dominates London’s residential real estate market, material for this research shows that the Hong Kong middle-class buyers have also been playing a significant role since the beginning of the 1990s which has been under-studied. In addition, Hong Kong has a well-established real estate sector specialising in selling UK properties.

Marketing strategies and property fairs

Some Hong Kong families interviewed were among the first 1990s wave of London home buyers. The properties purchased tend to be used by their children studying at London universities, with parents visiting occasionally. In other instances, when children were at primary or secondary schools, one parent would live in London while the other parent continued to work in Hong Kong.

Since then, the trend in property investment has transformed from buy-to-live to ‘buy-to-fry’2, and more recently buy-to-let properties which are mostly for sale for rental purposes (Ho & Atkinson, Citation2018).

During fieldwork in Hong Kong advertisements for property fairs in local newspapers were identified, published in both Chinese and English, that marketed residential homes in the UK. Properties in Hong Kong, as well as other global cities such as Sydney, Toronto, New York, Tokyo, Bangkok and Kuala Lumpur were also being promoted. Property fairs usually take place in hotel conference rooms in Central, the financial district, and high-end properties tend to be hosted at prestigious hotels with refreshment and beverages served.

Upon arrival, visitors are asked to provide contact details before a sales representative is assigned. Marketing brochures and scale models of properties are then shown to potential investors. These properties are usually sold off-plan for developments that are yet to be built or are currently under construction and could take up to two years to complete.

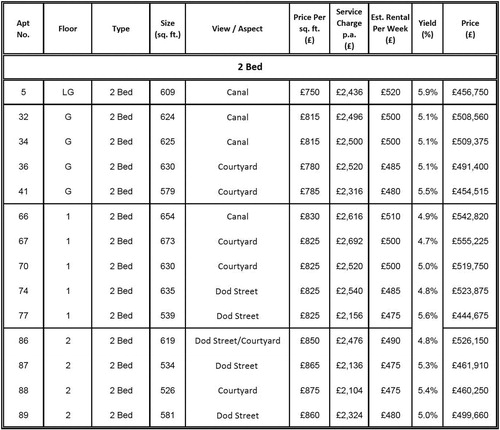

Not all properties offer the same rental yield. For example, Apartment 5 () illustrates a development in east London that offers the highest return of 5.9%, while Apartment 67 yields the lowest at 4.7%. At a time when banks in Hong Kong offer close to zero per cent on saving accounts, these apartments are attractive alternative products for long term investment.

Figure 1. Price list of the apartments with rental yield. Source: Marketing materials collected at a property fair in Hong Kong during fieldwork.

The apartments which offer the highest rental yield are usually reserved for existing clients. We witnessed a family engaged in conversation with an agent about a previous purchase and they thanked him because the rental income had already yielded a profit. At these fairs, a solicitor and a mortgage broker are usually present and provide buyers with relevant services. The researchers made further visits to other fairs promoting properties in other UK cities organised by different firms, and the sales tactics were almost identical. On one occasion, we met a London-based solicitor who flew to Hong Kong for a weekend property fair selling high-end London apartments; several dozens of contracts were signed before he returned to London on Sunday evening.

After each fair, the researchers received follow-up phone calls to ask if a purchase would be made. On another occasion, e-mails and phone calls were received from a major Chinese bank based in one of the regional offices in England regarding the potential arrangement for a UK mortgage that would be conducted in pound sterling. This was based on the fact that the researchers were living in England so a UK mortgage would be more suitable.

Properties in the UK were previously sold based on the number of bedrooms but square feet or metre size might not be necessarily indicated. However, marketing has recently been adapted to how Hongkongers understand residential real estate. First, properties in Hong Kong have long been sold by size measured in square feet, and UK properties are now also being marketed in a similar way as shown in .

‘Now it’s in square feet because this is what they use in Hong Kong, China and Singapore… otherwise they wouldn’t understand [how big an apartment is]. Then they [investors] know how to compare.’

(Participant 3, shareholder and director of a property investment company, interviewed in London, translated from Cantonese).

‘I think the property market may change. It used to be that this is a one- or two- or three-bedroom apartment. They didn’t really have the measurement. Now they [investors] will ask for the square feet. They are slowly learning from the South East Asian market. They never really talk about the size…’

(Participant 10, individual investor, interviewed in London, translated from Cantonese).

The operations of residential real estate investment involve key actors based in the UK and Hong Kong, but closer inspection suggests they are transnational. For example, advertising published in a Hong Kong newspaper promoting a Manchester development had an e-mail domain registered by a Singaporean company, which was owned by another Singaporean real estate firm. This example illustrates that the geographies of real estate investment are made up of various professional intermediates (Koh & Wissink, Citation2018) located in different parts of the world. Moreover, this is also made possible because Hong Kong and Singapore have ranked consistently as being the freest economies in the world (Miller, Kim, & Roberts, Citation2018). For example, there is no upper limit to the amount of the local currencies – Hong Kong dollars and Singaporean dollars can be converted into other currencies and transferred out of both city-states.

Property investment demand created a new wave of entrepreneurs such as one of the research participants (Participant 19), a Hong Kong-based real estate director who partnered with other UK house builders, architects and land developers to develop residential projects, mainly aimed at Hong Kong clients, but also Malaysian and Singaporean buyers.

The ease of buying a UK property from property fairs in Hong Kong depends on the emergence of property management companies and real estate firms which cater specifically to Hong Kong investors. One participant said that these companies tend to offer a complete package that requires minimum effort from buyers, other than paying for the property.

Another participant also made a similar comment and identified the way that Hongkongers invest:

‘With Hong Kong buyers… if they think the prices are good, and there is a profit margin, then they will ‘fry’. They don’t mind so much the type of properties. They really look at the price. Even with student accommodation, you can ‘fry’ those as well. Those packages tend to include some sort of return for a number of years. They know how to do the maths, they don’t need to make a payment for several years, then they will sell it off. They think is it a consumer good, they will sell it off several years later. This is different to Europeans, they have to look at the property first. They want to see what they are buying.’

(Participant 3, shareholder and director of a property investment company, interviewed in London, translated from Cantonese).

In the early 2010s, the residential real estate market in London began to rise and in 2016 an average property cost around £600,000 (LSL Property Services, Citation2016): what was once seen as an affordable investment became high risk and relatively low return. Consequently, properties in other UK cities with a significant lower entry point at around £80,000, such as Glasgow, Manchester, Liverpool and Bradford, became desirable.

‘So the net yield in London is only about 3% whereas if you buy student accommodation in say Bradford or Newcastle-under-Lyme, you’re talking about a 10% net yield for the next three years at least. If you’re talking about a private property in Manchester, you’re looking at a 5.5-7% net yield, in Liverpool it’s a 6% net yield. So, for the amount that they [investors] have to invest they get a lot more back for their money and they don’t have to put as much down in London as it is.’

(Participant 21, property consultant based in the UK and Hong Kong, interviewed in Liverpool).

Data relating to developments on High Street Kensington and in Battersea suggest buyers from Malaysia, Singapore, Hong Kong and mainland China have bought off-plan apartments mainly for investment purposes. Some of these have changed hands before the developments have been completed.

‘There is also [a development on] High Street Kensington, it looks quite good, still not yet completed but a lot of customers [who bought off-plan] now want to sell them. They [Asians, Singaporeans] may not be able to re-sell. I have a friend [who has a] two-bedroom, he wants to sell it for one point nine [million pounds]. New builds are not for local buyers, they are mostly for overseas buyers. Investors buy properties for profits. Lot of investors now are selling, if you are lucky [it can be sold]. In Hong Kong and mainland China, it’s very easy to ‘fry’, everyone wants to ‘fry’. If the market goes up then there are always buyers.’

(Participant 3, shareholder and director of a property investment company, interviewed in London, translated from Cantonese).

The popularity of global property investment is reflected in the growing popularity of publications such as books and blogs written by Hongkongers. For example, a Hong Kong publisher commissioned a series of books each specialising in a particular country, including the UK and Japan. The researchers interviewed an author of one of the books in this series that focuses on property investment in the UK. The publication, written in traditional Chinese is presented with a detailed analysis of several UK cities listing their strengths and weakness and providing maps and photos. This author also ran a blog and received e-mails from readers asking for investment advice. However, neither popular nor academic literature tells us about the processes by which properties are bought by middle-class Hong Kong investors which the following section will discuss.

Buying and financing a property, and the theorisation of the Hong Kong middle-classes

Contrary to the academic literature which shows that the super-rich buy prime and super-prime properties in cash as primary residences or second homes because global cities are regarded as ‘social and cultural circuits’, and seeking out ‘London for its cosmopolitanism, leisure and consumption offerings and sense of relative safety, compared to many of the wealthiest countries of origin’ (Atkinson, Citation2016, p. 1314), this section will show how middle-class Hong Kong investors use financial leverages to buy properties. Further, some may only occasionally use their properties when they have children studying in London, but few treat these properties as second homes. In some cases, they do not own a property in Hong Kong, or first home at all.

The researchers met other investors, one of whom was an independent investor looking for a buy-to-let, long-term investment property in one of the major cities in northern England, who was introduced to an agent of a Hong Kong-based firm that specialised in selling UK properties. She was told by the agent that a client was selling a relatively new property that came with a rental contract, but the transaction between the client and participant had not taken place due to price disagreement. Soon after, the agent called again about an off-plan development with a guaranteed rental yield of 6% for three years, the construction of which would be completed within 18 months. Some apartments on the higher floors were already sold despite the fact the development had only just been released, and she decided to buy a unit at around £120,0003. According to the UK government the current Stamp Duty Land Tax (SDLT) threshold is £125,0004 for residential properties which makes investing in northern cities attractive because many properties do not cross this threshold.

Real estate agents in Hong Kong regularly inform their clients about market trends, property valuations and any policy changes made by the UK government that might affect investment strategies, such as the change to the capital gain tax (CGT) regime by which non-UK residents were to be taxed on profits made from residential property sales from April 2015.

There are different ways for investors to secure capital for investment and it is usually carried out through financial leveraging by re-mortgaging an existing home in Hong Kong. For example, being a home owner in Hong Kong and having a stable income, Participant 25, an individual investor, re-mortgaged part of her property through a local bank at an interest rate below 2% to cover the entire cost of the new investment in northern England. The leverage against a property is only possible because of Hong Kong’s high property values. For Participant 25, the re-mortgage application took less than a week to process and approve. Once the capital was released from the bank, the money in Hong Kong dollars was then converted by the bank to pounds sterling. Quite often banks advise their clients to open an off-shore pounds sterling account if they do not already have one. From a financial perspective, the differences in interest rates allow an investor to achieve a return of between 4% and 5% before other costs such as ground rents, service charges and rental licences are deducted. Similarly, the author of the investment guide (Participant 18) spoke of how his Hong Kong-based colleague secured a loan from a Singaporean bank to buy a property in the UK with all the arrangements and communications taking place via e-mails. To obtain a residential buy-to-live mortgage from a UK bank the interest rate ranges between 3% and 4%. In contrast, Singaporean banks offer a lower interest rate which is close to 1%. Furthermore, Participant 20, another independent investor, borrowed against her two homes in Hong Kong to enable the purchase of a property in Australia and two in northern England. Such forms of financing capture the efficient flow of capital between global cities that encourages international property investment.

Regarding Participant 25, the first financial transaction for the property took place in the real estate agent’s office at which a £2,000 non-refundable cash reservation deposit was paid; thereafter, a London-based solicitor with offices in Hong Kong was in touch regarding the legal processes. The buyer was required to make three additional payments to the solicitor during the course of the construction. While the legal documents were sent to the buyer via e-mail, document signing took place at the solicitor’s office in Hong Kong. The researchers were shown various documents including the contract, floor plan, land registration, property management agreement and rental contract. The contract in particular was written in both English and Traditional Chinese. One of the researchers was invited by the buyer to attend meetings at the agent’s offices as well as at the solicitor’s office. When the contract was first exchanged, the solicitor reminded the investor that in the case of the development not being built, the capital already invested could not be recovered, and this happened to some investors.

In recent years, there have been increasing numbers of cases in which construction companies and real estate firms have gone into liquidation leading to investors losing their capital (Li & Zhou, Citation2017). Foul play was suspected and affected investors sought legal assistance from the Hong Kong government. The increasing number of complaints filed with Hong Kong statutory institutions such as the Estate Agents Authority and Consumer Council have raised public awareness of the financial risks involved in buying off-plan overseas properties. For instance, a recent document, The Regulation of Sale of Overseas Properties (Legislative Council Secretariat, Citation2017), published by the Legislative Council of Hong Kong (the equivalent of the Parliament) explores how Taiwanese and Singaporean governments deal with similar scenarios and makes several recommendations including stricter advertising guidelines and licensing rules for estate agents dealing with properties outside Hong Kong.

Investors are aware of other factors such as political events, economic crises and currency fluctuations which can affect the return on investment. The strategy is not to sell during a downswing in the market as they believe that the overall market will grow in the medium to long term. There are other risks, too. Participant 20 reported that her property located in northern England was severely damaged by a tenant which caused her several thousand pounds to repair.

When the development Participant 25 was buying was nearing completion, the property management company was in touch, requesting bank details of the account into which the rent would be paid. Being a non-UK resident, the investor was advised to submit a Non-Resident Landlord form to HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) to avoid capital gain tax being deducted by the property management company. However, non-resident landlords are still required to file tax returns and pay the relevant taxes. Nonetheless, the apartment was being rented to a university student and the participant confirmed that the rental income was being deposited by the management firm accordingly. As findings illustrate, the intermediaries within the real estate market operate on such an efficient level that Hong Kong middle-classes investors are not required to visit the UK in order to buy properties.

It is further evident that the current UK property market has been transformed to suit investors of different income levels, not only for the super-rich, as a UK based property consultant commented:

‘I know that the majority of investors in London [are] actually Singaporean; Singapore, Hong Kong and China have bought a lot of Liverpool [real estate]. … The investors that we have [are] not the super-rich - they are rich compared to the average person but they’re not millionaires as such.’

(Participant 21, property consultant, interviewed in Liverpool).

This observation has theoretical and policy implications for residential property investment. Taking income and wealth as indicators, two subgroups can be identified: the wealthy middle-class and the aspiring middle-class. (For the purposes of this research, gender, professional background, age and generational difference are less important5).

First, the wealthy middle-class can be defined as individuals or family units having one or both earners generating enough income to secure a property in Hong Kong while investing in another home in London or other parts of the UK. The rental income generated can contribute towards the mortgage taken out against the property or the children’s education fees in the UK. The wealthy middle-class includes those who invested in properties in London in the early 1990s.

Second, the aspiring middle-class can be seen as those who cannot afford a home in Hong Kong, may live with parents or in a rental property but have managed to save a deposit for a more affordable home in northern England. These aspiring middle-class investors who want to achieve financial security like the wealthy middle-class may also invest in other South East Asian countries such as Thailand where residential real estate is inexpensive. They use the rental income generated to repay the loan taken out in Hong Kong. The underlying idea is that the mortgage will be fully paid off in 15 or 20 years’ time and it is possible to release the capital when necessary. In other words, the less-well off investors who have appeared since the early 2010s, can also invest in overseas properties.

Indeed, both kinds of middle-class investors use home ownership in Hong Kong as leverage to fund overseas properties to enable wealth creation (Lui, Citation1995, Citation2003). Moreover, while many high-end properties that cost above £1 million are being bought by the super-rich through companies registered for tax efficiency in offshore locations such as the British Virgin Islands, this case does not apply to individual middle-class Hong Kong buyers investing in properties at a relative lower price level. Nevertheless, the implications of overseas property investments for policy are discussed in the next section.

Housing supply and policy implications

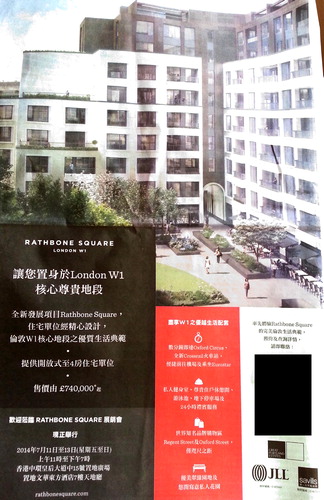

Research participants were aware that foreign investment in the residential property market in London and other UK cities has contributed to the rising cost of housing. Evidence shows that property developers have prioritised their clients in Hong Kong and released apartments before making them available in the UK. For example, this advertisement for a central London development was being circulated in July 2014: other than the Chinese text both adverts are almost identical (see : Hong Kong Market; and : UK market). One was printed in a local Hong Kong newspaper at the beginning of July with the starting price at £740,000, and the development was being exhibited in a hotel conference room in Central during a property fair that took place between 11 and 13 July 2014 (translated from Traditional Chinese). The same property was being advertised in The Economist in the same month with the starting price at £905,000, an increase of £165,000 in a period of less than two weeks. It could be understood that the cheapest available apartments were already sold in Hong Kong or Hong Kong clients were given discounts while UK clients were being charged more.

Figure 2. A central London development being first released in Hong Kong. Source: Ming Pao (明報), a local Hong Kong newspaper, print edition, 11 July 2014, section A15.

Figure 3. The same central London development being released in the UK market 2 weeks later. Source: The Economist, print edition, issue 19–25 July 2014, p. 69.

In terms of UK housing policy on this issue of early release in certain markets, some 50 house builders as well as several organisations, including London First, London Chamber of Commerce and the Home Builders Federation, signed up to a voluntary agreement in 2014, known as the Mayoral Concordat, in which the Conservative Mayor of London encouraged ‘developers across the UK to commit to selling all new homes to Londoners before or at the same time as overseas buyers’. A senior housing policy officer for London commented that:

‘It [was] of a lot of interest, and the Mayor agreed, [so] we called a concordat with leading house builders… where they committed to marketing any new homes in the UK at the same time as overseas. There’s only been one example that we've heard of that’s been highlighted, where a developer wasn’t doing that … was it administrative error? And, well, … maybe it wasn’t, we don’t know. They [the developers] were certainly very upset and indignant when they were called down.’

(Participant 12, senior housing policy officer, interviewed in London).

Another participant also spoke about this agreement:

‘It’s basically the Mayor created this thing which is called the Mayoral Concordat, a very grand sounding thing, and he got quite a lot of developers to sign up to it. It basically said that we commit to marketing our residential properties equally, at the same time… to Londoners as we do to the rest of the world… .’

(Participant 9, policy lead on housing for a leading business membership organisation, interviewed in London).

But as the participants commented, this is not a contract with legal implications and that the Mayoral Concordat did very little to prevent properties in London being given priority through early release of sales to overseas investors. Nonetheless, it was declared a failure by the Labour Mayor of London in 2016 (Greater London Authority, 2016).

Despite the way the popular media has criticised the increasing number of foreign investors buying apartments in London, some participants commented that without foreign capital, homes might not have been built during the recession around 2007 and 2008, and in any case there has long been a shortfall in house building:

‘I think there was a particular time post-recession and in fact, during the recession, when foreign investment was keeping London’s housing market going and that is frequently overlooked, you know. Actually, if these developments hadn’t been built, and we hadn’t had the off-plan sales, and we hadn’t had that foreign investment, then nothing would have got built. And of course as these developments get built, typically they deliver a really - in some instances - good chunk of affordable housing, which is typically going to what some people call “ordinary Londoners” you know.’

(Participant 9, policy lead on housing for a leading business membership organisation, interviewed in London).

‘The current market relies on overseas buyers. Look at all the developments, the buyers are all South East Asians.’

(Participant 3, shareholder and director of a property investment company, interviewed in London, translated from Cantonese).

In short, aspects of residential properties have generated exclusive markets for the wealthy and aspiring middle-class Hong Kong investors, and this is in contrast with popular and academic debates about the super-rich’s dominance in London’s housing market. By creating an exclusive market for the Hong Kong middle-classes, UK buyers are increasingly being excluded from home ownership. The data has also signalled that the middle-class is not a homogenous group.

Conclusion

This article has analysed the operation of the real estate sector that specialises in selling UK properties to Hong Kong investors and its wider significance in transnational property investment and the remit has been twofold. First, it has theoretically challenged the way in which the two groups of investors are perceived, and the way global super-rich and Hong Kong middle-classes approach second home ownership. In contrast with both popular opinion and the academic research which argues that investors of real estate are the super-rich who purchase properties with illicit cash as a safe way to park assets (Fernandez et al., Citation2016) and leave them unoccupied and under-occupied or as second homes, this research shows that property investors are not a homogenous group. As such, the Hong Kong middle-classes buy properties in the UK (as well as other parts of the world) at property fairs in Hong Kong not to reside, but mostly for investment purposes through the rental income obtained and long-term capital growth. Specifically, many of these buy-to-let properties are bought with financial leverages through which capital is released by re-mortgaging a home in Hong Kong. More significantly, this article challenges the theoretical understanding of the Hong Kong middle-class (Lui, Citation2003) and introduces the two subgroups of middle-class investors: the wealthy middle-class and the aspiring middle-class. The major distinction is that while the first group of investors already have properties in Hong Kong and their interest in overseas investment can be traced back to the early 1990s, the latter group do not own first homes in Hong Kong, but have ‘second homes’ in distant locations. This observation contrasts with current understandings of second home ownership which suggests that second properties are used as vacation homes (Roca, Citation2013) or for lifestyle migration (Koh, Citation2017). This form of second home ownership or residential investment property has significantly affected the availability of housing in London, and evidence shows that investment has shifted to second-tier northern cities where property costs significantly less.

Second, this article made a methodological contribution to research into the geographies of residential real estate investment. Specifically, it highlights the importance of being reflective when engaging with various actors within the field of real estate, and having the relevant local knowledge and language skills affects the process of data collection and the quality of data. It would be challenging for a non-Cantonese speaker to attend local meetings, gain the trust of other attendees and conduct ethnographic research without having the relevant lingual, intracultural and personal credentials. Thus, the data used for this research would have been limited to the engagements with English speakers and consequently have missed some of the most important aspects of how the Hong Kong transnational property market works.

In short, the free market economy in Hong Kong as well as a well-established and efficient real estate sector that incorporates various international intermediaries including estate agents, financiers, marketing executives, mortgage providers, solicitors, land developers, house builders, and so on, who facilitate buying and selling foreign properties, has created a vibrant foreign real estate investment industry that allows the free movement of capital and global currency exchange without any limit.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Rowland Atkinson for his input on this research. The author would also like to thank the journal editors and four anonymous reviewers whose comments and suggestions helped improve this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The singular understanding of the middle-class is conceptualised by Lui (Citation2003). For the definition of the middle-classes, see section Buying and financing a property, and the theorisation of the Hong Kong middle-classes.

2 ‘Fry’ is a colloquial Cantonese term that refers to speculate a form of asset for short-term financial gain, see Ho and Atkinson (Citation2018).

3 The exact amount is undisclosed due to confidentiality.

4 As of 2018.

5 See section International real estate investment and Hong Kong society.

References

- Atkinson, R. (2016). Limited exposure: Social concealment, mobility and engagement with public space by the super-rich in London. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 48(7), 1302–1317. doi:10.1177/0308518X15598323

- Atkinson, R., Burrows, R., & Rhodes, D. (2016). Capital city? London’s housing markets and the ‘super-rich’. In I. Hay & I. Beaverstock (Eds.), Handbook on wealth and the super-rich (pp. 225–243). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Atkinson, R., Parker, S., & Burrows, R. (2017). Elite formation, power and space in contemporary London. Theory, Culture & Society, 34(5–6), 179–200. doi:10.1177/0263276417717792

- Büdenbender, M., & Golubchikov, O. (2017). The geopolitics of real estate: Assembling soft power via property markets. International Journal of Housing Policy, 17(1), 75–96. doi:10.1080/14616718.2016.1248646

- Census and Statistics Department, Hong Kong. (2018). Mid-year population for 2018. Retrieved from https://www.censtatd.gov.hk/press_release/pressReleaseDetail.jsp?charsetID=1&pressRID=4272

- Cox, H. (2018, February 22). Sky-high Hong Kong: Can anything stop the property price boom? Financial Times. Retrieved from http://www.ft.com

- Cupples, J., & Kindon, S. (2003). Far from being ‘home alone’: The dynamics of accompanied fieldwork. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 24(2), 211–228. doi:10.1111/1467-9493.00153

- Doling, J., & Ronald, R. (Eds.). (2014). Housing East Asia: Socioeconomic and demographic challenges. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dupuis, A., & Thorns, D.C. (1998). Home, home ownership and the search for ontological security. The Sociological Review, 46(1), 24–47. doi:10.1111/1467-954X.00088

- England, K.V.L. (1994). Getting personal: Reflexivity, positionality, and feminist research. The Professional Geographer, 46(1), 80–89. doi:10.1111/j.0033-0124.1994.00080.x

- Fernandez, R., Hofman, A., & Aalbers, M.B. (2016). London and New York as a safe deposit box for the transnational wealth elite. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 48(12), 2443–2461. doi:10.1177/0308518X16659479

- Forrest, R., Wissink, D., & Koh, S.Y. (Eds.). (2016). Cities and the super-rich: Real estate, elite practices and urban political economies. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Fung, K.K., & Forrest, R. (2002). Institutional mediation, the Asian financial crisis and the Hong Kong housing market. Housing Studies, 17(2), 189–208. doi:10.1080/02673030220123180

- Greater London Authority. (2016, June 22). Sadiq criticises flagship Boris scheme. Retrieved from http://www.london.gov.uk/press-releases/mayoral/london-homes-being-sold-as-golden-bricks-oversea

- Haila, A. (2000). Real estate in global cities: Singapore and Hong Kong as property states. Urban Studies, 37(12), 2241–2256. doi:10.1080/00420980020002797

- Harrington, B. (2016). Capital without borders: Wealth managers and the one percent. London: Harvard University Press.

- Hay, I. (Ed.) (2013). Geographies of the super-rich. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Hay, I., & Muller, S. (2012). ‘That tiny, stratospheric apex that owns most of the world’ - Exploring geographies of the super-rich. Geographical Research, 50(1), 75–88. doi:10.1111/j.1745-5871.2011.00739.x

- Ho, K. (2009). Liquidated: An ethnography of Wall Street. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Ho, H.K., & Atkinson, R. (2018). Looking for big ‘fry’: The motives and methods of middle‐class international property investors. Urban Studies, 55(9), 2040–2056. doi:10.1177/0042098017702826

- Karsten, L. (2015). Middle-class childhood and parenting culture in high-rise Hong Kong: On scheduled lives, the school trap and a new urban Idyll. Children’s Geographies, 13(5), 556–570. doi:10.1080/14733285.2014.915288

- Knight Frank. (2013). International residential investment in London. Retrieved from http://content.knightfrank.com/research/503/documents/en/2013-1217.pdf

- Koh, S.Y. (2017). Property tourism and the facilitation of investment-migration mobility in Asia. Asian Review, 30(1), 27–45.

- Koh, S.Y., & Wissink, B. (2018). Enabling, structuring and creating elite transnational lifestyles: Intermediaries of the super-rich and the elite mobilities industry. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(4), 592–609. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1315509

- Kohl, E., & McCutcheon, P. (2015). Kitchen table reflexivity: Negotiating positionality through everyday talk. Gender, Place & Culture, 22, 747–763. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2014.958063

- Legislative Council Secretariat. (2017). Regulation of sale of overseas properties. Retrieved from https://www.legco.gov.hk/research-publications/english/1617in10-regulation-of-sale-of-overseas-properties-20170426-e.pdf

- Li, J., & Zhou, V. (2017, March 14). Hong Kong probing overseas property scams that cost buyers HK$500m in losses. South China Morning Post. Retrieved from http://www.scmp.com

- Liu, S., & Gurran, N. (2017). Chinese investment in Australian housing: Push and pull factors and implications for understanding international housing demand. International Journal of Housing Policy, 17(4), 489–511. doi:10.1080/19491247.2017.1307655

- LSL Property Services. (2016). House price index April 2016. Retrieved from http://www.lslps.co.uk/documents/house_price_index_apr16.pdf

- Lui, T.L. (1995). Coping strategies in a booming market: Family wealth and housing in Hong Kong. In: R. Forrest & A. Murie (Eds.), Housing and family wealth (pp. 108–132). London: Routledge.

- Lui, T.L. (2003). Rearguard politics: Hong Kong’s middle class. The Developing Economies, 41(2), 161–183. doi:10.1111/j.1746-1049.2003.tb00936.x

- Lui, T.L., & Wong, T.W.P. (1994). A class in formation: The service class of Hong Kong. Unpublished research report, Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange.

- Merriam, S.B., Johnson‐Bailey, J., Lee, M., Kee, Y., Ntseane, G., & Muhamad, M. (2001). Power and positionality: Negotiating insider/outsider status within and across cultures. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 20(5), 405–416. doi:10.1080/02601370120490

- Miller, T., Kim, A.B., & Roberts, J.M. (2018). 2018 index of economic freedom. Washington, DC: The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.heritage.org/index/pdf/2018/book/index_2018.pdf

- Paris, C. (2013). The homes of the super-rich: Multiple residences, hyper-mobility and decoupling of prime residential housing in global cities. In: I. Hay (Ed.), Geographies of the super-rich (pp. 94–109). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Poon, A. (2011). Land and the ruling class in Hong Kong (2nd ed.). Singapore: Enrich Professional Publishing.

- Pow, C.P. (2017). Courting the ‘rich and restless’: Globalisation of real estate and the new spatial fixities of the super-rich in Singapore. International Journal of Housing Policy, 17(1), 56–74. doi:10.1080/14616718.2016.1215964

- Roca, Z. (Ed.) (2013). Second home tourism in Europe: Lifestyle issues and policy responses. London: Ashgate.

- Rogers, D., & Koh, S.Y. (2017). The globalisation of real estate: The politics and practice of foreign real estate investment. International Journal of Housing Policy, 17(1), 1–14. doi:10.1080/19491247.2016.1270618

- Rogers, D., Wong, A., & Nelson, J. (2017). Public perceptions of foreign and Chinese real estate investment: Intercultural relations in Global Sydney. Australian Geographer, 48(4), 437–455. doi:10.1080/00049182.2017.1317050

- Rose, G. (1997). Situating knowledges: Positionality, reflexivities and other tactics. Progress in Human Geography, 21(3), 305–320. doi:10.1191/030913297673302122

- Saunders, P. (1986). Social theory and the urban question. London: Hutchinson.

- Saunders, P. (1990). A nation of home owners. London: Unwin Hyman.

- Savage, M., Devine, F., Cunningham, N., Taylor, M., Li, Y., Hjellbrekke, J., … Miles, A. (2013). ‘A new model of social class? Findings from the BBC’s Great British Class Survey experiment’. Sociology, 47(2), 219–250. doi:10.1177/0038038513481128

- Smart, A., & Lee, J. (2003). Financialization and the role of real estate in Hong Kong’s regime of accumulation. Economic Geography, 79(2), 153–171. doi:10.1111/j.1944-8287.2003.tb00206.x

- Waters, J.L. (2006). Geographies of cultural capital: Education, international migration and family strategies between Hong Kong and Canada. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 31(2), 179–192. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2006.00202.x

- Waters, J.L. (2010). Failing to Succeed? The role of migration in the reproduction of social advantage amongst young graduates in Hong Kong. Belgeo, 4, 383–393. doi:10.4000/belgeo.6419

- Zhao, Y. (2017). Doing fieldwork the Chinese way: A returning researcher’s insider/outsider status in her home town. Area, 49(2), 185–191. doi:10.1111/area.12314

- Zheng, S. (2017, January 24). Record complaints as overseas sales sting Hong Kong investors. South China Morning Post. Retrieved from http://www.scmp.com