Abstract

In Chile, social condominiums are a significant part of housing for low-income households. After decades of occupancy, this housing stock shows signs of rapid deterioration and devaluation due to neglected maintenance. Given the weak governmental support in management practices, third sector organisations are positioning themselves as alternatives to providing technical solutions and contributing to the enhancement of opportunities and capacities among communities that live in deprived areas. However, little is known about the dynamics between these organisations and the communities they work with as well as their interactions with their institutional environment in the context of improving condominium management practices. Employing concepts of intermediation and institutionalisation, we analyse the practice of the organisation Proyecto Propio. We describe the dynamics of the intermediary role as implementer of housing policy and catalyst of social innovation, and the institutionalisation of these practices. The main characteristic of their intermediary role in condominium management practices is a holistic approach as implementer and catalyst for complex interventions, situating the users at the centre of the process. The main challenges are related to institutionalisation: the inclusion of more incentives to scale up and consolidate the third sector as a relevant actor in housing and condominium management.

Introduction

Low-income homeowners often face financial and social constraints that are serious challenges to providing adequate maintenance. The fact of owning a property should lead to material progress, security and income opportunities to cope with poverty; however, these benefits depend on the capacity of homeowners to keep the property in good condition, and also on the opportunities and support generated by the context and the institutions involved. If these conditions are not guaranteed, low-income households are at risk of experiencing unsuccessful ownership processes that may perpetuate conditions of poverty (Elsinga & Hoekstra, Citation2005; Marcuse, Citation1972). In the case of multiowned buildings, also known as condominiums, the tension between individual and collective needs also affects maintenance, and entails additional challenges for collective decision-making to take care of common areas of the property (Donoso & Elsinga, Citation2016). Furthermore, the collective management is defined by complex connections between property and law (Blandy, Dixon, & Dupuis, Citation2006).

The case of Chile is illustrative of the problem of low-income homeownership and condominium maintenance. During the 1980s and 1990s, neoliberal housing policies were progressively adopted by governments focusing on tackling informal settlements with national programmes for social housing provision. Subsidies and credit facilities, combined with the massive construction of low-cost housing by private developers, enabled low-income groups to access homeownership (Gilbert, Citation2004). This model, widely adopted in Latin America, has been criticised because of its negative social and urban impacts, especially in the promotion of spatial and social segregation (Rolnik et al., Citation2015; Sabatini, Cáceres, & Cerda, Citation2001); the construction of low-quality housing that led to premature deterioration (Ducci, Citation1997; Gilbert, Citation2004) and the generation of new processes of urban impoverishment given the poor institutional support (Camargo & Hurtado, Citation2011). In Chile, the signs of rapid deterioration in the housing stock have demonstrated the emergence of a new qualitative housing deficit, especially in condominium tenure. Medium-rise building apartments named Condominios Sociales (social condominiums) became symbolic of the most problematic housing type in terms of low initial construction and design quality, the neglected maintenance of common property areas, organisational shortcomings and social conflicts.

Private homeownership is the main mechanism of housing acquisition for vulnerable groups in Chile (Salcedo, Citation2010). Despite this, low-income homeowners in Chile do not have institutional support or access to affordable services to deal with condominium management in terms of administration, long-term maintenance or social conflict resolution (Vergara, Gruis, & van der Flier, Citation2019). The government has adopted a secondary position with respect to the problem, contributing short-term solutions through subsidy programmes. The subsidiary model is neither efficient nor effective, however, in addressing the social and organisational problems underlying poor maintenance. Furthermore, there are no regulations or parameters to define adequate maintenance practices. Additionally, private services for condominium administration available in the market are not willing to work with social housing.

In this situation, when neither the government nor the private sector is part of the solution, the third sector increased its participation in condominium and neighbourhood renovation activities, especially in recent decades. Third sector (TS) organisations have positioned themselves as relevant intermediaries by providing technical services and improving the capacities and opportunities of communities that live in deprived areas (Vergara, Citation2018a), either as independent organisations or as vehicles of subsidy programmes. Although they have made contributions in terms of social innovation and social economy (Gatica, Citation2011; Pizarro, Citation2010; Subse, Citation2015), the role of these actors is still unclear, especially regarding their performance in specific fields such as housing management and maintenance. Furthermore, most studies that do describe the roles of TS organisations focus on social issues (social capital, safety, etc.). Studies that have a specific focus on housing-related issues are mainly oriented towards housing provision in the not-for-profit rental sector in a Western European and Northern American context (Mullins, Czischke, & van Bortel, Citation2012; van Bortel, Mullins, & Gruis, Citation2010; Walker, Citation1993). On the other hand, literature that focus on their role in the improvement of low-income owner occupied housing is scarce. While some studies have contributed to the understanding of the factors underlying poor maintenance practices from the collective action theory (Donoso & Elsinga, Citation2016; Pérez, Citation2009), more research is needed regarding solutions and strategies to support low-income homeowners in the management of their properties.

This article explores the intermediary role of third sector organisations in the context of low-income homeownership and condominium management practices. Using the concepts of institutionalisation (Oosterlynck et al., Citation2013; Vicari & Tornaghi, Citation2014) and intermediation (Lee, Citation1998; Lewis, Citation2002), the article analyses the practice of the organisation Proyecto Propio (PP). The main question is, to what extent does a third sector organisation like Proyecto Propio contribute to improve management practices among low-income homeowners.

The article is structured as follows. First, a general (background) description is given of social condominiums in Chile and the related management challenges. Then, the role of the TS is conceptualised according to how they can fulfil their intermediary role (implementers, catalysts or partners) and according to how these practices are institutionalised. Subsequently, the case of Proyecto Propio is described and discussed, addressing the dynamics of their intermediary role: the primacy of holistic approaches, bonds of trust and ambivalences between top–down and bottom–up approaches. The dynamics of institutionalisation are also discussed: the instrumental relationships between the third sector and the government and scarce cross-sector cooperation.

Social condominiums and the challenge of collective management

A social condominium is the name used by the government to describe one of the social housing types built under the new housing construction programmes. It consists of medium-rise building apartments which contain individual property and common domain property. According to the Cadastre of the Ministry of Housing and Urbanism (MINVU, Citation2014) 5689 social condominiums were built between 1936 and 2013, grouped in 1555 housing complexes and harbouring 344,000 dwellings. The cadastre registered problems of housing maintenance in 99% of the social condominiums, of which 69% presented advanced signs of deterioration, particularly those built between 1980 and 1999. This period represented the peak of the massive housing construction with the smallest apartments being on average 45 m2.

Low-income families that invest in their dwellings usually do it according to their available resources and most urgent needs with do-it-yourself solutions. According to the cadastre, 77% of the social condominiums presented external modifications, most of them illegal and precarious extensions of the ground floor over common domain areas or extensions on upper floors that endanger the safety conditions of the condominiums (MINVU, Citation2014). These adaptations are incremental, take place throughout an entire family cycle (Greene & Rojas, Citation2008) and involve purposes such as giving shelter to extended family (Araos, Citation2008; Moser, Citation1998), developing home-based productive activities (Gough & Kellett, Citation2001) or improving the sense of security inside the house (Rodriguez & Sugranyes, Citation2005). This implies that preventive measures or planned maintenance in the common property areas are unlikely options given the existence of other financial and social priorities. Furthermore, at the community level, researchers have noted the existence of inactive communities, social conflict as a result of the forced coexistence of families with different sociocultural backgrounds and the prevalence of individual actions that endanger community cohesion, and therefore collective activities like maintenance (Aravena & Sandoval, Citation2005; Pérez, Citation2009; Segovia, Citation2005).

The difficulties of providing long-term maintenance are aggravated by the contextual conditions of these condominiums, which do not offer a structure of opportunities to enhance the potential benefits associated with homeownership, such as economic stability, self-esteem and material progress (Marcuse, Citation1972; Rohe & Stegman, Citation1994). A predominant characteristic of low-income homeownership in Santiago is residential segregation (Brain, Mora, Rasse, & Sabatini, Citation2009; Sabatini et al., Citation2001), which has led to social stigma, a lack of material opportunities and the emergence of other social problems such as violence, crime or drugs (Tironi, Citation2003). These dwellings are also static assets which are barely part of the housing market due to their initial low quality or the negative perception that citizens have of these neighbourhoods (Salcedo, Citation2010). Finally, relocation policies, especially during the 1980s and 1990s, diminished the social networks and organisational capacities of residents (Ducci, Citation1997; Marquez, Citation2005).

Despite the aforementioned consequences of social housing policies, housing maintenance and management have not been incorporated in the public agenda and nor have they been assumed as part of governmental responsibilities (Vergara et al., Citation2019). This is reflected by a lack of policies focused on maintenance and collective management, and the lack of actors able or willing to provide housing management to low-income groups. The regulatory framework for condominiums is the law 19.437 from 1997, the ‘Ley de Copropiedad Inmobiliaria’ (Co-ownership Law) which establishes administrative guidelines for condominium tenure and defines the following organisational elements: administrative committee, administrator, co-owners assembly, condominium regulations and monthly expenses for maintenance. Nonetheless, there are no specific indications regarding maintenance or parameters to evaluate whether a condominium maintains good performance.

In terms of housing policies, the subsidy programmes created in 2008 for condominium improvements, Programa de Mejoramiento de Condominios Sociales (PMCS), has contributed to upgrading the technical conditions of the dwellings and condominiums; however, apart from the administrative organisation of condominiums (the process is known as formalisation), current governmental programmes do not offer any type of mechanism to uphold investments and to ensure that proper maintenance will be carried out in the future. Between 2012 and 2016, the subsidy programme covered 20% of the potential national demand estimated by the government, demonstrating its productive capacity (Larenas, Cannobbio, & Zamorano, Citation2016). However, it has not been possible to estimate whether the programme is effective or not in achieving its goals, to evaluate the sustainability of the interventions or to understand whether the improvements carried out by third parties (Entidades Patrocinantes) are solving the main problems or focusing on the most critical cases (Larenas et al., Citation2016).

In terms of actors involved in housing management, the participation of the private sector and third sector in social condominiums is narrowed to the subsidy programmes (PMCS) in the form of the Entidades Patrocinantes (Technical Assistance Entity). These are profit, non-profit or municipal organisations enrolled in the Ministry of Housing and Urbanism to implement subsidies. Profit entities within these organisations are predominant in the subsidy market (Cannobbio et al., Citation2011) in contrast to a minority of third sector organisations and municipalities. Exploratory interviews carried out in 2015 with key stakeholders in the area, showed that for-profit entities tend to have better financial and technical capacity in relation to the non-profit sector or municipalities, but they are more reluctant to provide services for complex and vulnerable neighbourhoods. Furthermore, some of them have used the subsidies to pursue their own financial interests, neglecting social goals. By contrast, non-profit intermediaries tend to focus on the most complex and vulnerable cases, with the willingness to go beyond the subsidy requirements in order to achieve social goals where needed (Vergara, Citation2018a).

On balance, the challenge of condominium management by low-income families is twofold. On one hand, it includes the financial and social restrictions faced by homeowners that diminish their collective capacity to take care of building maintenance. On the other hand, it includes institutional limitations with regard to housing and condominium management in terms of regulations, governmental support and actors.

Third sector and social innovation: intermediation and institutionalisation

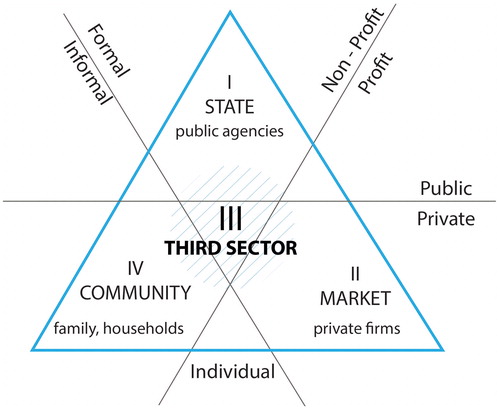

From the perspective of a solidarity-based economy, the third sector is viewed as an intermediate space between the market, the state and society (Defourny, Citation2009). Acknowledging their hybridity and changeability (Brandsen, van de Donk, & Putters, Citation2005), third sector organisations share common features such as their aim to ‘provide good or services to their members or to a community, rather than generating profits’ and specific governance rules which seek ‘independent management, democratic decision-making process and primacy of people and labour over capital in the distribution of income’ (Defourny & Nyssens, Citation2014, p. 42). The definition of the third sector coexists with other overlapping and related concepts such as non-profit sector, nongovernmental organisations, civil society, économie sociale or independent sector, with different emphasis according to the research tradition and languages (Anheier, Citation2005; Brandsen et al., Citation2005). In this article, we will use the concept of third sector as the umbrella for different types of organisations which are neither part of the commercial nor the public sector, such as social enterprises, NGOS, foundations, not-for-profit and non-profit organisations (). We will then focus on third sector organisations that contribute to housing management activities and work in vulnerable contexts.

Figure 1. Third sector organisations between the State, the market and the community. Based on Brandsen et al. (Citation2005).

According to Defourny (Citation2009), third sector organisations have been active in the production of quasi-public goods, the redistribution of resources and provision of services to deprived sectors. Third sector organisations have also been necessary in overcoming market and state failures while proposing social change in developing and emerging countries (Tello-Rozas, Citation2016).

Following this, the third sector has been historically associated with social innovation, entrepreneurial dynamics and the invention of new types of services to take up contemporary challenges (Defourny & Nyssens, Citation2014). Moulaert, MacCallum, and Hillier (Citation2014) defined social innovation as ‘innovation in social relations’. It refers ‘not just to a particular action, but also to the mobilisation-participation processes and to the outcome of actions which lead to improvements on social relations, structures of governance, greater collective empowerment and so on’ (Moulaert, et al., Citation2014, p. 2). Under this approach, social innovation is strongly a matter of process innovation, social inclusion and empowerment. In the field of housing features such as user involvement, user perspective, streamlining, cross-sector collaboration and multi-dimensional approach have been identified as common elements in social innovative practices (Czischke, Citation2013).

In this regard, institutions, namely, organisations, regulations, laws and agents, play a necessary role in the creation of new relationships or collaborations in deprived sectors (Vergara, Citation2018b). We will focus on the third sector’s role of providing social innovation by satisfying unmet needs, changing the dynamics of social and power relations or increasing the communities’ capacities and access to resources. These new relations and collaborations can be described from two perspectives of analysis: the intermediation, which refers to the relationship between the organisation and the community, and the institutionalisation, which refers to the dynamics between the organisation and its institutional background.

Intermediation

One characteristic of the third sector is its capacity to be an intermediary at the local level, supporting deprived or excluded groups which have reached the limit of what they can achieve by themselves (Lee, Citation1998). In the field of community development, ‘to intermediate’ is defined by scholars as acting for, between and among entities, considering the future well-being of communities and individuals (Liou & Stroh, Citation1998).

In housing studies, researchers have analysed the intermediary role of the third sector focusing on the dynamics between the intermediary, the community and the institutions. For instance, in the context of co-production, the role of coaching organisations was highlighted, to help the communities to navigate through both social and building information (Fromm, Citation2012), or to enable access to resources and key decision-making processes by promoting vertical connections with powerful stakeholders (Lang & Novy, Citation2014). Another example is the identification of critical issues in the context of slum upgrading, such as the balance between creating a viable and durable relationship with the community without generating dependency or the disincentives to community participation due to the discontinuity of projects and governmental programmes (Lee, Citation1998).

Given the scope of this study, an appropriate approach to identifying how the intermediary role is performed in terms of strategies and activities is provided by Lewis (Citation2002, Citation2003) in the context of non-governmental development organisations (Vergara, Citation2018b). The author suggests a classificatory framework of three overlapping sets of roles and activities: implementers, catalysts and partners. The ‘implementer’ role refers to organisations that mobilise resources to provide goods and services that are wanted, needed or otherwise unavailable. The organisation can provide these services with its own resources or be contracted by the state or by a donor in return for payment (Lewis, Citation2002). The ‘catalyst’ role refers to organisations that inspire, facilitate or contribute to developmental change among other actors at the organisational or individual level (i.e., grassroots organising, group formation or empowerment-based approaches). The ‘partner’ role refers to organisations that work with other institutions such as the government, donors and the private sector, sharing the risk or benefit of the joint work. Partnership is also a way of making more efficient use of scarce resources, increasing institutional sustainability and improving client participation (Lewis, Citation2002).

To identify and understand the possible contributions of third sector organisations based on their practices, we adapted Lewis’s definitions of roles (implementer, catalyst and partner) to condominium management, in which the condominium is the unit of the analysis and the collective management is the focus of the intervention. The condominium is understood as a common property resource, collectively managed by co-owners with the purpose of maintaining the quality of their built environment. Combining elements from organisational management theory (Gruis, Tsenkova, & Nieboer, Citation2009), institutional analysis and development framework (Ostrom, Citation2011) and social vulnerability framework (Moser, Citation1998) condominium management is defined as a multi-dimensional process with three inter-related dimensions: technical, organisational and sociocultural (Vergara et al., Citation2019).

Interpreting the framework of Lewis, implementers as providers of goods or services are focused mainly on improving the physical conditions of the built environment, involving all services and activities that aim directly at the buildings, collective areas and/or the dwellings. The catalyst role, as facilitator of developmental change, comprises organisations that contribute to improving the community’s capacity in relation to condominium management. Therefore, it involves activities in which the community is the main target. Finally, the partner role contributes to improving the capacities of the organisation to intervene in the condominiums. Partnerships are, therefore, a means to improve either the built environment or the capacity building of the community. Whilst catalyst and implementers aim directly at the condominium, partners aim at the organisation itself as an immediate goal. shows the three roles, adapted to condominium management practices and associated to management dimensions.

Table 1. Role and activities for intermediary organisations applied in condominium management.

Institutionalisation

The second characteristic is related to the contextual conditions of third sector practices, which are path-dependent (affected by existent decisions and processes) and thus, spatially and institutionally embedded (Moulaert, MacCallum, & Hillier, Citation2014). In an optimal situation, far from being isolated, these organisations are required to cooperate with supra-local institutions at different spatial levels to be up-scaled and therefore achieve a structural transformation (Moulaert, Martinelli, Swyngedouw, & Gonzalez, Citation2005; Oosterlynck et al., Citation2013). While the motivation of organisations to pursue social change has been named ‘the fuel’ of social innovation, the process of institutionalisation has been named ‘the engine’ (Vicari & Tornaghi, Citation2014). The latter is the mechanism that allows the reproduction of these practices over time, influencing and then consolidating innovative practices in public institutions (Vicari & Tornaghi, Citation2014).

Social innovative practices and public institutions react and interact in a complex relationship, which develops in a ‘dynamic balance between tendencies and solutions and local specificity, flexibility and guarantees of rights, decentralisation and coordination, participation and delegation, subsidiarisation and institutional responsibility’ (Oosterlynck et al., Citation2013, p. 26). In this dynamic, the state and public institutions, as the ‘engine’, have the potential to contribute and support third sector practices at different levels, influencing the process of institutionalisation either providing legal conditions, resources or opportunities to generate a fertile ground for social innovation. At the same time, social innovative practices, as the ‘fuel’, impact on multilevel governance in terms of policy making, transforming values or providing a more democratic process, which need to be sustained and renewed in a dynamic context (Pradel Miquel, Garcia Cabeza, & Eizaguirre Anglada, Citation2014). Considering the social interest and public-oriented connotation of these practices, in this article, institutionalisation is mostly focused on the relationships with the public sector and its institutions at different organisational levels (i.e., municipality, region, local government and central government). It also refers to the legal framework and policies that regulate and define their performance.

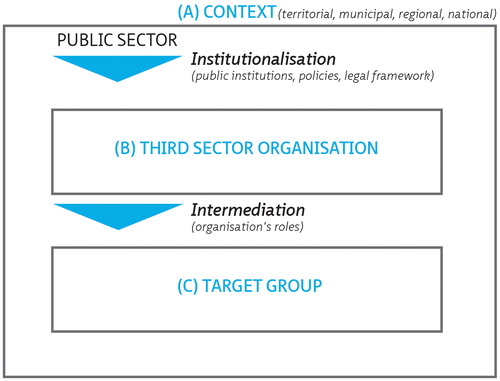

Intermediation and institutionalisation represent two characteristics to understand the practices of third sector organisations as providers of social innovation in deprived contexts (). On one hand, the intermediation refers to the relationship between the organisation and the target group in a specific territory of intervention (i.e., a neighbourhood, a condominium or a district) and provides insights about the role and the strategies employed by the organisations in deprived communities. On the other hand, the concept of institutionalisation refers to the relationship between the organisation that intervenes, with its institutional context (i.e., public entities, legal frameworks, and policies), which may enable or hinder the possibilities of scaling up and increase the impact of social innovative practices.

Figure 2. Institutionalisation and intermediation for third sector practices. Source: Vergara (Citation2018a).

Foundation Proyecto Propio: a third sector organisation working in condominium improvements

The third sector in Chile

In Chile, the third sector has been defined as an ‘archipelago of social experiences’ (Delamaza, Citation2010), being heterogeneous and fragmented (Pizarro, Citation2010) but at the same time as a social innovative space (Gatica, Citation2011; Gatica, Quinteros, Vásquez, & Yañez, Citation2015).

After the return to democracy in 1990, the third sector experienced an accelerated increase, which was reinforced in 2011 with the promulgation of Law 20,500, which offered a new regulatory framework to facilitate the legal registration of civil society organisations (Irarrazabal & Streeter, Citation2016). Despite being fragmented and dispersed, scholars have noted common characteristics that contribute to defining this sector in Chile. Some authors have referred to an instrumental relationship between the government and the third sector (Delamaza, Citation2013; Espinoza, Citation2014; Pizarro, Citation2010) which was consolidated during the transition to democracy. While the third sector, and especially NGOs, played an important role during the dictatorship, channelling international cooperation, when democracy was reinstated, the state used the accumulated experience to implement new programmes and actions, subordinating the third sector as external implementers of local projects under the goals of public services (Delamaza, Citation2013; Espinoza, Citation2014). One of the consequences of this is the strong dependence on governmental funding, affecting the sustainability of these organisations (Espinoza, Citation2014) which main revenue resources (46%) come from subsidies and public payments (Irarrazabal, Hairel, Wojciech, & Salamon, Citation2006). Scholars have indicated that the unrestricted expansion of the system of public funds to social projects in the last two decades has increased competitiveness between organisations while diminishing their associative capacity (Espinoza, Citation2014; Pizarro, Citation2010).

Another characteristic of the third sector is the presence of social innovation values and social entrepreneurship opportunities, especially in the last decade. The concept of social innovation emerged as a response of society to complex problems channelled through the traditional third sector organisations and the social enterprises as new hybrid models (UC, Citation2012).

During the last decade, an increasing number of foundations, associations and community-functional organisations have sought to position themselves as agents of political and urban transformation, participating in and influencing the implementation of projects related to the built environment (Larenas & Lange, Citation2017). Organisations such as Techo (emergency housing and affordable housing construction), Urbanismo Social (affordable housing construction and neighbourhood improvement), Junto al Barrio (neighbourhood improvement) and Proyecto Propio (housing and neighbourhood improvement) represent an interesting trend of organisations participating actively in housing provision, housing improvement and neighbourhood renovation activities, some of them as vehicles of housing policy (Vergara, Citation2018a). These organisations are driven by social goals and pursue social innovation values. They have emerged as an alternative approach to the for-profit sector, while taking care of unfulfilled governmental tasks.

Method

A case study was conducted to obtain in-depth information about the foundation Proyecto Propio regarding its goals, role and approach to improving the physical quality and management of social condominiums. An exhaustive description of the case can be found in Vergara (Citation2018a). The foundation was chosen after reviewing Chilean TS organisations’ practices, consulting experts in the field and interviewing the organisation’s funding partner. The organisation was selected based on the following criteria: (1) the experience of the organisation working in social condominiums and the existence of good quality information by which to measure results; (2) the availability of information and the possibility of contacting the professionals and the residents; and (3) representativeness of the case in relation to other third sector organisations. At the time of selection, the foundation Proyecto Propio was the most experienced and active organisation working with social condominiums. The organisation also participates actively in the public debate and provides open access information about their work.

As part of the case study, fieldwork was carried out in January 2016 using qualitative methods including interviews with professionals of the organisation, interviews with co-owners and field observation. The following activities were conducted:

Interviews with the organisation’s professionals: executive director and funding partner; social director and funding partner; architect in charge of technical projects for condominium improvements; and social worker in charge of social processes for condominium improvements. Four interviews were conducted.

Interviews with homeowners: five interviews with co-owners, of which three of them are chairperson of their administrative committees.1

Field observation: three condominiums that had recently been improved by the organisation have been visited by the researcher; they are part of the neighbourhoods of Valle de la Luna (Municipality of Quilicura) and Vicente Huidobro (Municipality of Bosque).

The activities in Chile were complemented by a review of institutional documents facilitated by the organisation and secondary sources such as websites and media material produced by Proyecto Propio (Ted Talks, propaganda videos, articles and informative videos). The description of the case will be organised in three parts: initial situation, intermediation and results.

Initial situation

The professionals were asked about the organisation’s characteristics, goals, financial sources and organisational structure. They also were asked about the main technical, organisational and sociocultural management problems detected in the condominiums.

Proyecto Propio is a non-profit organisation that has the legal standing of a foundation, although they identify themselves as a social enterprise. According to the executive director, the main financial resources come from governmental subsidies and consultancy work. They define themselves as a ‘methodological intermediary, which enables the access to knowledge, but also to mechanisms and processes to help community to develop their own projects’ (Fundacion Proyecto Propio, Citation2016). The foundation works in vulnerable context, it is 12 years old, and it has been able to position itself as a social brand. During their trajectory, they have adopted a flexible organisational model to adapt themselves to the workload. The permanent staff of 25 employees can assume different roles according to current organisational need and priorities. The foundation is managed by a board of three directors: the executive director, the operations director and the social director, who define the guidelines for the strategic management of the four areas: central coordination, building company, entidad patrocinante, social brand and shared services. The executive director defines this organisational structure as ‘a foundation that owns four social enterprises’.

The design and construction of condominium improvement projects has been a major task within the organisation since 2012. They increased their participation in condominium improvements, becoming entidad patrocinante (technical assistance entity) to implement the governmental programme PMCS. The social director noted that this represented an opportunity for the deeper insertion of the organisation into the local areas and for participation in public policies. It also represented a better financial opportunity to develop projects with higher impact.

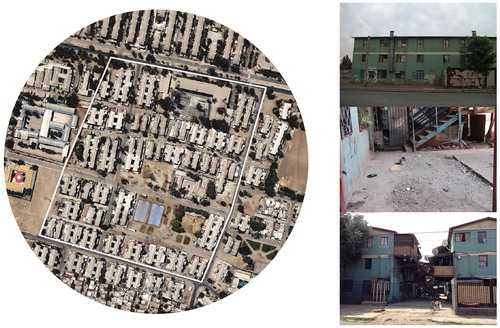

At the time of the fieldwork, the organisation was working in the neighbourhood of Valle de la Luna in the municipality of Quilicura and Vicente Huidobro in the municipality of El Bosque. The neighbourhood Valle de la Luna () was built in 1993 and comprised 1356 dwellings organised in 25 condominiums. On average, one condominium includes 70 households. The neighbourhood Vicente Huidobro was built in 1992 and has 408 dwellings.

Figure 3. Valle de la Luna neighbourhood, Municipality of Quilicura, Santiago. Situation before the intervention. Source: Fundacion Proyecto Propio.

According to the organisation professionals, the main technical problems in the condominiums were the result of the lack of planned maintenance over the last 20 years, aggravated by the poor initial quality of the design and construction. In addition to the generalised deterioration of common areas, precarious extensions have affected the spatial quality of the central courtyards.

Organisational problems identified by the professionals are related to a lack of awareness that residents live in a condominium, and a lack of knowledge about condominium law, which leads to unclear responsibilities about maintenance and administration. Residents commonly do not recognise the boundaries of their own condominiums. Even though families have managed to invest in their own apartments, there is no maintenance fund. Some condominiums are not formalised and do not have administrative committees or internal regulations. If there is self-organisation, it happens at the level of blocks (one building within the condominium) or pairs of blocks. Finally, the professionals pointed out that the main sociocultural problems consist of drugs micro-trafficking, but also of ‘bad practices’ regarding housing maintenance, such as using courtyards as rubbish areas or engaging in individualistic attitudes when it is necessary to cooperate to clean up the common domain areas. The organisation has detected low self-esteem among the residents due to the deteriorated environment conditions, affecting their capacity for action and creating a general distrust in institutions. The interviewees explained that even though there are a few active leaders among the community, the majority of the community tends to be passive regarding maintenance.

Intermediation

To describe the intermediation, organisation professionals were asked about the role of Proyecto Propio and the main strategies developed to intervene in social condominiums. The interviewees’ responses were organised according to the role classification of implementer, catalyst and partner.

Proyecto Propio combines implementer and catalyst roles, in which they target both the community and the buildings with their own human resources. The organisation does not formally partner with other organisations or institutions to carry out the activities; nonetheless, they try to achieve informal collaboration with the municipality and the community leaders to enable a better insertion in the neighbourhoods.

In its role as implementer, Proyecto Propio executes improvement projects in social condominiums financed by governmental subsidies. They are therefore vehicles of housing policies, providing a physical renovation of the condominium within the budget and conditions imposed by the programme. During the design process, they use participatory tools to customise the projects according to household needs and to engage the co-owners in the decisions related to their properties. Although the implementer role is predominant, the organisation also acts as a catalyst by supporting co-owners to activate their organisational structures, by promoting the emergence of leaders in the condominiums and by increasing co-owners’ awareness about the co-ownership law.

The professionals noted three main strategies used to carry out the intermediation which differentiate them from other (more technically oriented) entidades patrocinantes: to value the community as capable users, to promote transparency by making technical and financial information accessible to the community and to customise the improvement projects in the condominium using participative design methodologies. To do this, the organisation developed a tool called El Tablero (the blackboard), which contains steps that help the community to define their projects collaboratively.

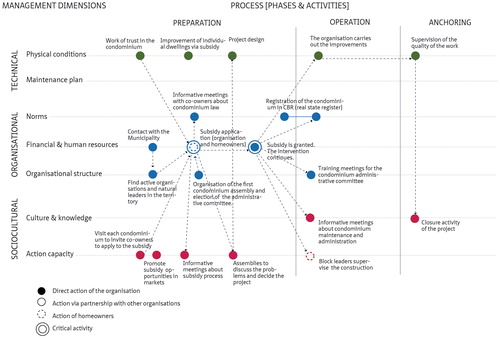

To analyse the process, the activities were grouped in three main phases: preparation, operation and anchoring and associated to the management dimensions (). The preparation phase comprises all the necessary activities to involve the community in the project and can take up to 6 months. The organisation has to apply to the subsidy programme to obtain the financial resources. This means that the community has to be organised and the organisation has to present a technical proposal with the consent of the co-owners. Given the importance of this initial step for the continuity of the project, the organisation invests more time and resources in this phase to gain the trust of the community, get them involved in the process and reach a consensus about a project for the condominium. These activities range from financial incentives to the use of participatory design methods and the search of allies in the community. According to the social professionals of the organisation and the community leaders, this phase is time consuming, and an important workload for them. It also requires substantial (pre)investment from the organisation when the risk of failure is still high.

Figure 4. Process of intermediation. Activities carried out by Proyecto Propio organised according to management dimensions and phases. Source: Vergara (Citation2018a).

The operation phase starts once the subsidy is obtained, and has a duration from 6 to 12 months, which is defined by the subsidy programme. At this stage, they finish the design of the project and make the adjustments required to carry out the construction. The improvement of the condominium in Valle de la Luna required a total budget of €202,414, which was used to pave the condominium area, install a new fence, paint the facades, replace the rain gutters, repair the staircases, change windows and doors, improve the roof, removing asbestos cement and eradicate the plague of pigeons. A team of one social worker and one architect is in charge of the process and the community recognises them as the organisation’s representatives. This phase also includes the training of the committee members regarding administration, as well as assemblies with the community to provide information about maintenance. Given the knowledge gap between the community and the difficulties of transferring the information widely, they decided to focus the training on the administrative committee. Their assumption is that the leaders will transfer the knowledge to the community and to the other committee members.

Another element of the intermediation is the formalisation of the condominium according to the co-ownership law, which can be done either in the preparation phase or in the operation phase.

The anchoring phase is not as clearly defined as the previous phases. The intermediation officially ends when the improvement project is complete, usually with a social gathering with the community. Although the team withdraw from the condominium, they do not completely withdraw from the neighbourhood until the area plan is completed. This plan consists of interventions in as many condominiums as possible in the same territory. In most situations, they will start a new process with another condominium, continuing informal communication with the previous community if needed.

Results

The organisation professionals were asked about success parameters to evaluate the intervention, and the community were asked about the performance of Proyecto Propio. From the perspective of Proyecto Propio, the success of a project is associated with participatory processes, the generation of understanding among the community and the intention to adopt new perspectives regarding condominium maintenance. Related to indicators to measure the achievement of their goals, the social director mentioned that ‘the people have a platform to organise themselves as co-property (co-owners), to be a formal condominium, but also to have an administrative committee that understands its role and the law; and a group of neighbours that understands the goals of living in a condominium. What happens after this? They will have to see how to use these tools, according to their own aspirations’ (Interview, Social Director PP, 2016).

The community evaluated the performance of Proyecto Propio positively. The interviewees highlighted the good communication with the organisation and the professionals’ willingness to resolve doubts. ‘They always explained the status of the projects, where there were doubts they came, we talked to them and they answered our questions’ (Neighbour’s interview, Valle de la Luna, 2016). There were some problems noted, however, such as technical mistakes by the building company during the construction process and delays with paperwork at the beginning.

The physical and aesthetical improvement of the condominium was highly appreciated by the community. According to the chairperson and the neighbours, the community started to use the common areas more after the improvements in Valle de la Luna, to decorate them and to think about applying for new projects. After the intervention, community leaders noticed an increase of the participation of households in collective tasks and more willingness to maintain common areas, at least in the short-term.

Before I did not have plants outside my apartment. It was not paved, but I always had to sweep the floor and I have complained that the other people would not do it. Now, sometimes other people sweep as well. Actually, they brought a new plant for the courtyard. (…) I really wanted this block to be improved, it was horrible. But I did not have the motivation. The block did not have lighting and everybody stayed at their homes and the common areas looked abandoned. The kids did not go to play outside. Now, it is different. (neighbour’s interview, Valle de la Luna, 2016)

After comparing the previous and final situations in the condominiums, it is possible to identify some pending challenges in different dimensions. Regarding the organisational dimension, the main challenges are related to financial resources, which remain ambiguous. Even though the co-owners have established regulations concerning monthly expenses for maintenance, there is no certainty that co-owners will pay their contributions. These contributions are set very low (from 2 to 3 euros per month), not enough to finance more than small repairs or daily maintenance activities. The most likely situation is that co-owners will keep relying on subsidies to maintain their condominiums. In the sociocultural dimension, the main challenge is to keep the positive response of the neighbours in the long run, transforming this reaction into good maintenance practices. Other social problems such as drugs micro-trafficking and delinquency are out of the organisation’s scope, but are permanent threats and barriers to community cohesiveness. By the end of the project, the condominiums are formalised and have an administrative committee that has received basic training and a set of regulations. Furthermore, the community is aware of the law and the limits of their condominiums.

Discussion

Proyecto Propio provides interesting insights into the capacities and limitations of Chilean third sector organisations in supporting homeowners to improve the management of their condominiums. The discussion will develop two main topics relevant to the role of third sector organisations in deprived contexts. The first part will elaborate on the dynamics of local intermediation, understanding the main contributions and barriers for condominium management. The second part will discuss the institutionalisation of these practices in the Chilean context.

The dynamics of intermediation

Three main dynamics define intermediation between the organisation and the community: primacy of holistic approaches over specialisation, bond of trust and ambivalences between top–down and bottom–up approaches.

Primacy of holistic approaches over specialisation

The organisation adopted an implementer and catalyst role to support distressed communities regarding administration and maintenance. Whilst the implementer role aimed at satisfying unmet needs, the catalyst role aimed at changing the dynamics of power and social relations, and increasing the capacities of the community. As implementer, the organisation provided access to architecture and construction services financed with governmental resources resulting in an upgrade of the technical and aesthetical conditions of the condominium, thus solving the most urgent technical needs. As catalyst, Proyecto Propio focused on strengthening the internal organisation by increasing the capacity of the community, and especially the leaders, to manage their own buildings. The results of the intermediation were new dynamics inside the condominium which consolidated leaderships in existing or new organisational structures under the indications of the co-ownership law. The complement between catalyst and implementer activities is expected to impact positively on the community and the built environment. It is expected that the better quality standards will enable future decision-making processes regarding maintenance, whilst the aesthetical upgrade will contribute to a positive perception of the community about their built environment. Similarly, it is expected that the leaders will be able to coordinate the community and overcome the internal conflicts inside the condominium to provide maintenance.

Proyecto Propio does not develop partnerships to carry out catalyst and implementer activities. Although some collaborations with the municipality and the community leaders are mentioned, they do not represent equal partnerships. For instance, the municipality is an important enabler at the beginning of the intermediation by providing information about the condominiums and access to the leaders, but it does not take an active part throughout the process. Similarly, community leaders are key allies in approaching the residents, acting as intermediary actors between the organisation and the community. Nevertheless, their participation is still an undefined area, lying between voluntary work and the potential of being professionalised as a paid job within the process.

The core tasks of the intermediation are therefore performed with the organisation’s human resources. This seems to be effective in achieving comprehensive interventions in which the intermediary keeps control over the process, has a deep knowledge of the situation in the condominium and a close relationship with the community. However, the decision of providing a holistic approach with their own resources and within the timeframe and conditions of the subsidy implies that the problems detected are partially addressed. The intermediation lacks actions that contribute directly to long-term management such as the provision of a maintenance plan, support to the community to deal with internal conflicts derived from the use of common property or concrete solutions regarding the legal situation of informal enlargements. The intermediation, therefore, is characterised by the sense of urgency and the need of being efficient in the management of limited resources. Hence, Proyecto Propio ensures the provision of the basic elements to the condominium to upgrade their technical, organisational and sociocultural status enabling future management.

Bond of trust

Although intermediaries require some degree of distance from the community to be neutral, they also need to build relationships with them, which are basically based on mutual trust. Nevertheless, this trust is not guaranteed. The experience of Proyecto Propio showed that the intervention needed to take account of previous history dealing with problems and experiences that affect the process. Proyecto Propio works with communities that have been neglected by the Government, lacking a network of institutional support during their transition to homeownership (Rodriguez & Sugranyes, Citation2005). Furthermore, this lack of institutional support is aggravated by a series of unsuccessful experiences faced by the same community. Failed projects with previous entidades patrocinantes, governmental institutions or foundations have diminished the credibility in the success of these interventions (Interview, social worker, 2016; Interview, neighbour Valle de la Luna, 2016). Therefore, organisations acting in these territories have to allocate an important amount of resources at early stages of the intervention building trust between their professionals and the community when the risk of failure is still high.

In the case of Proyecto Propio, the community did not request their services, which means that the organisation has to prove their ‘good intentions’ to the co-owners and show them the potential benefits of working together. An important part of this trust is built on the personal capital of face-to-face relationships between the professionals and the neighbours. During the process, features such as availability, willingness to solve doubts and the provision of adequate information were positively evaluated by the community as effective in generating good communication channels and mutual trust.

Ambivalences between top–down and bottom–up approaches

The community was identified as inactive regarding maintenance activities. But, as previously explained, this is the consequence of a bundle of problems related to the financial and organisational capacity of the co-owners to carry out maintenance but also to the governmental debt in terms of housing quality and social segregation. In this sense, the organisation is an external agent that initiates the intermediation in a top–down manner, but at the same time puts a strong emphasis on the involvement of co-owners. The project occurs in private property, and thus requires the voluntary and collective participation of co-owners to succeed.

During the process, the organisation makes an effort to overcome paternalistic approaches by actively involving the leaders during the process, incorporating existing internal organisations at block level in the process, being transparent with the information, placing the final decision upon the improvement project to the community and promoting a client–professional relationship. However, during the process and the implementation of the activities, some ambivalences can be noted. One of them refers to the ultimate goal of the organisation which is to support the community to develop their own projects. During the intermediation, the community is able to make informed decisions about the technical projects, but the type and implementation of the projects follow a rigid process given by the subsidy conditions. Therefore, there is an agenda for the condominium defined before the intermediation.

Another ambivalence is noted in who is the institution that holds the responsibilities during the process. The organisation presents itself as a service provider for the co-owners, who are valued as capable users. Nonetheless, apart from the administrative committee, there is an important number of residents that are not fully aware of the motivation behind the project and do not participate in the meetings. Although the organisation makes efforts to position the users at the centre of the intervention by transferring the responsibilities of the project decisions, the control of the whole process still resides on the intermediary and not on the community as an organised group. In this regard, reaching an appropriate power balance between different parties, when the external organisation is the ‘initiator’, arises as a relevant factor to consider in its role as intermediary. An unbalanced situation may generate further dependency in which the community will continue relying on the intermediary as initiators of new projects. This in turn, may impact on the outcome of the catalyst role, especially in achieving greater collective empowerment.

The dynamics of the institutionalisation

Institutionalisation of third sector practices is relevant to achieve structural transformations and consolidate the TS beyond scattered and isolated social experiences. From the analysis of Proyecto Propio, the dynamics of the institutionalisation are characterised by an instrumental relationship between the TS and the government and scarce cross-sector cooperation.

Instrumental relationship: financial dependence on subsidies and transference of public responsibilities

As stated by Oosterlynck et al., social innovative practices and institutions interact in complex and dynamics relationships. The analysis of Proyecto Propio shed some light into the relationship between the third sector and the government, which can be defined as instrumental. Proyecto Propio relies on governmental resources to develop their own agenda under a project-based approach, adapting themselves to public goals. Their experience as entidad patrocinante showed that the subsidy programme for condominium improvements is a financial enabler but at the same time, represents a methodological barrier. As financial enabler, the budget of the subsidy for the technical project is enough to make substantial changes and the payment for the services is satisfactory. As barrier, the professionals discussed problems related to the limited timeframe to develop the social plan, the lack of incentives to innovate and the excessive bureaucracy which restrained the social and organisational intervention at the minimum level. For the organisation, the subsidy is a tool to achieve a larger goal which is a territorial intervention in a deprived neighbourhood. To do so, they carry out systematic interventions of social condominiums in the same territory as a way to achieve more significant and permanent changes. Given that the subsidy programmes work ‘on demand’, their use by the organisation contributes positively to steer the allocation of resources towards a territory in which the organisation has already invested, and where it has established a relationship with local communities and the municipality.

Apart from the territorial perspective, the organisation carries out additional activities in every condominium focused on the catalyst role to overcome the limitations of the subsidy. These additional investments are part of the social innovation perspective by focusing on the provision of tools and increasing the leaders’ capacities to improve the administration of condominiums. Whilst this evidences the shortcomings of the subsidy programme, it also reveals the transference of responsibilities from the government to the implementer of subsidies without proper resources, especially in the social plan.

The dependence of third sector organisations on the subsidy as the only means to intermediate in condominiums does not contribute to ensure stability over time, and moreover, restricts their capacity to innovate. A clear example is how these organisations keep a flexible structure, changing their goals according to the public policy and the type of available subsidies. The main challenge is to overcome the instrumental relationship, by establishing a collaborative relationship instead, in which the government is actually the engine that provides institutional support. This would serve to strengthen the third sector as a relevant actor, under the right incentives, where its social innovation acting as the fuel, can actually permeate and promote institutional innovation.

Limited cross-sector cooperation

The main relationship between the third sector and the central government in the area of housing management occurs in the implementation of subsidy programmes for housing improvements. Nonetheless, this relationship is based on limited interactions and it is mostly focused on administrative procedures. According to the professionals of Proyecto Propio, there are no official channels by which the organisation can provide feedback from their experience implementing the programme. Furthermore, the efficient use of the subsidy in deprived neighbourhoods by TS intermediaries has contributed to generate an improved version of the programme; nonetheless, these results depend on the willingness of the organisations and have not been encouraged by the government. In this regard, the positive implementation of subsidies by TS organisations has not necessarily been reflected in a stronger cooperation with the central government; for instance, in potentially increasing the participation of these organisations in the design of public policies or promoting the development of third sector organisations at the institutional level.

The municipality is considered a key ally at the local level to start the intermediation, but the magnitude of its participation during the process depends on the capacity of the municipality involved. A recurring situation is that municipalities with a large proportion of social housing do not have the financial capacity or human resources to provide a major support for the organisations or establish long-term partnerships. In this regard, the relationship focuses on the exchange of information regarding the territory in which the municipality participates as an enabler rather than a partner. The lack of cross-sector collaboration limits also the capacity of the intermediary to actively connect the communities with available resources, networks and information beyond its own resources.

Conclusions

The management of affordable housing stock is a relevant challenge not only for Chile but also for Latin American countries that have consolidated low-income homeownership as the main mechanism for affordable housing provision. The article sought to understand and discuss the role of third sector organisations in supporting low-income homeowners to improve housing management practices. Employing the concepts of intermediation and institutionalisation, and the archetypical roles of catalyst, partner and implementer, we developed a conceptual framework to analyse the role and the performance of Proyecto Propio as an example of a third sector organisation, in improving the management of social condominiums in Santiago.

In terms of the intermediation, the use of archetypical roles allowed to describe the different ways it could be performed. Three main dynamics were identified. First, the primacy of holistic approaches over specialisation, in which the organisation is an implementer of condominium improvements and a catalyst of leaderships and better management practices. As implementer, the main contribution is the physical and aesthetical upgrading of the common domain areas. As a catalyst, the main contributions are the acknowledgment of the capacities of the community and their leaders, the provision of information to raise awareness about maintenance practices, and support to achieve internal organisation. These roles were performed without partnerships and with limited resources, resulting in solving the most urgent problems but lagging behind solutions aiming at long-term maintenance, and legal and financial administration. Second, dynamic is the development of a bond of trust between the organisation and the community. This was identified as a key initial step considering their history of distrust in institutions due to failed social interventions and poor governmental support. Third, the ambivalences between top–down and bottom–up approaches in which the organisation fosters the active participation of the residents but still holds the main responsibility and control over the process.

In terms of institutionalisation, the analysis showed that organisations such as Proyecto Propio have an instrumental relationship with the Government. While the organisation uses governmental subsidies to participate in the public debate and to pursue their own social agenda, the government transfers social responsibilities to these implementers without proper resources. In this regard, through intervening in social condominiums, the organisation is filling welfare gaps present in current housing policies. It also showed scarce cross-sector partnership between third sector organisations and other organisations, central government and local government.

From the analysis of Proyecto Propio, we identify three main challenges related to the role of the third sector and the management of social housing stock in Chile. First, we identify the need for an active role from the Government in generating housing policies during post-occupation processes, to support and inform homeowners as regards maintenance activities. Furthermore, specific action by the government is required to solve deep social problems underlying poor maintenance practices. Second, there is a need to strengthen third sector organisations, improve their institutional stability and stimulate their active participation in public policies as well as the formation of cross-sector partnerships, going beyond the current ‘passive’ institutional approach of the third sector as ‘mere’ vehicles of subsidies. And third, there is a need to diversify and enlarge the presence of the third sector in the field of condominium management. Besides holistic approaches such as Proyecto Propio, organisations that develop more specialised approaches could be valuable too to provide solutions for aspects of the management challenges that now remain unsolved, such as technical maintenance, financial strategies, legal advice, conflict resolution and social mediation.

The conceptualisation of the third sector as hybrid organisations, and the intermediation and institutionalisation of their practices, contributes to enrich the Latin American housing debate through offering a third approach between the predominant bottom–up and top–down discussions. First, it identifies the existence of unmet needs which are not being solved by the existing stakeholders. This leads to the relevance of the intermediation while recognising the communities’ capacities but also limitations to solve their needs. Second, it places the focus on the innovation in social relations, with emphasis in both the process and the final result. The innovation, thus, is related to provide a tangible product but also to support residents to take control over their built environment. Third, it highlights the influence of the institutional context to promote social innovation and generate structural transformations. The intermediation is understood as part of a political and sociocultural context. The analysis showed how institutional conditions, such as the financial dependence of governmental subsidies, the scarce cross-sector partnership or the lack of policies regarding maintenance, limit the outcomes of the intermediation as well.

The use of international frameworks developed in the northern literature contributed to position these concepts in the Latin American housing debate from a broader perspective. However, it also showed their limitations for the understanding of local phenomena, evidencing the need for building local theory regarding the third sector as intermediaries and social innovators in housing and condominium management.

The empirical analysis contributed to fill an important scientific and knowledge gap regarding the practices of the third sector in Chile in housing and neighbourhood management. Although the results cannot be generalised to the whole sector, it does provide information about local dynamics between the third sector, communities and institutions. More empirical research is needed to unveil the work of these organisations in deprived contexts which still remains unknown despite their relevance in contributing to overcome market and welfare gaps.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The interviews were conducted by the first author as part of her PhD project. The homeowners who were interviewed live in the neighbourhoods of Valle de la Luna and Vicente Huidobro. At the time of the interview, the condominiums were either improved or in an advanced stage of the process. Three out of five interviewees were the chairpersons of their condominium’s administrative committees, and the other two were residents. The chairpersons were women, two of whom had a long history as community leaders.

References

- Anheier, H. K. (2005). Nonprofit organizations: Theory, management, policy. London, UK: Routledge.

- Araos, C. (2008). La tensión entre conyugalidad y filiación en la génesis empírica del allegamiento. Estudio cualitativo comparado entre familias pobres de Santiago de Chile. (Master), Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santtiago.

- Aravena, S., & Sandoval, A. (2005). El diagnostico de los pobladores “con techo”. In A. Rodríguez & A. Sugranyes (Eds.), Los con techo: un desafío para la política de vivienda social. Providencia, Santiago de Chile: Ediciones SUR.

- Blandy, S., Dixon, J., & Dupuis, A. (2006). Theorising power relationships in multi-owned residential developments: Unpacking the bundle of rights. Urban Studies, 43(13), 2365–2383. doi: 10.1080/00420980600970656

- Brain, I., Mora, P., Rasse, A., & Sabatini, F. (2009). Report on social housing Chile. Santiago, Chile: ProUrbana, Centro de Políticas Públicas UC.

- Brandsen, T., van de Donk, W., & Putters, K. (2005). Griffins or chameleons? Hybridity as a permanent and inevitable characteristic of the third sector. International Journal of Public Administration, 28(9-10), 749–765. doi: 10.1081/PAD-200067320

- Camargo, A., & Hurtado, A. (2011). Vivienda y pobreza: una relación compleja. Marco conceptual y caracterización de Bogotá. Cuadernos de Vivienda y Urbanismo, 4(8), 23. Retrieved from https://revistas.javeriana.edu.co/index.php/cvyu/article/view/5474

- Cannobbio, L., Angulo, L., Espinoza, A., Jeri, T., Jimenez, F., Rieutord, F., … Urcullo, G. (2011). Investigación del funcionamiento de las Entidades de Gestión Inmobiliaria y Social en la Política Habitacional. Santiago: Sur Profesionales Consultores.

- Czischke, D. (2013). Social innovation in housing: Learning from practice across Europe. Discussion paper commissioned by the Chartered Institute of Housing on behalf of the Butler Bursary. Retrieved from http://www.cih.org/resources/PDF/Membership/Social%20Innovation%20in%20Housing%20-%20Darinka%20Czischke%20Final%20report%20and%20appendix%20Dec%202013.pdf

- Defourny, J. (2009). Concepts and realities of social enterprise: A European perspective. Collegium, Spring, 73–98.

- Defourny, J., & Nyssens, M. (2014). Social innovation, social economy and social enterprise: What can the European debate tell us? In F. Moulaert, D. MacCallum, A. Mehmood, & A. Hamdouch (Eds.), The international handbook on social innovation: Collective action, social. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Delamaza, G. (2010). Construcción democrática, participación ciudadana y políticas públicas en Chile (Doctoral dissertation). Universiteit Leiden, Leiden, The Netherlands.

- Delamaza, G. (2013). Quién eres, qué haces y quién te financia. Transparencia y roles cambiantes de las organizaciones de la sociedad civil. Revista Española Del Tercer Sector, 23, 89–110.

- Donoso, R. E., & Elsinga, M. (2016). Management of low-income condominiums in Bogotá and Quito: The balance between property law and self-organisation. International Journal of Housing Policy, 18, 312–334. doi: 10.1080/14616718.2016.1248608

- Ducci, M. E. (1997). Chile: el lado obscuro de una política de vivienda exitosa. EURE (Santiago), 23(69), 99–115.

- Elsinga, M., & Hoekstra, J. (2005). Homeownership and housing satisfaction. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 20(4), 401–424. doi: 10.1007/s10901-005-9023-4

- Espinoza, V. (2014). Local associations in Chile: Social innovation in a mature neoliberal society. In F. Moulaert, D. MacCallum, A. Mehmood & A. Hamdouch (Eds.), The international handbook on social innovation: Collective action, social learning and transdisciplinary research (pp. 397–411). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Fromm, D. (2012). Seeding community: Collaborative housing as a strategy for social and neighbourhood repair. Built Environment, 38(3), 364–394. doi: 10.2148/benv.38.3.364

- Fundacion Proyecto Propio (2016). Available from http://www.proyectopropio.cl/

- Gatica (2011). Emprendimiento e Innovación Social: construyendo una agenda pública para Chile. Retrieved from http://www.superacionpobreza.cl/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/20111227174334.pdf

- Gatica, K. C., Quinteros, C. F., Vásquez, L. R., & Yañez, L. D. (2015). Economias solidarias y territorios: el emprendimiento comunitario como factor clave de desarrollo en Chile. Paper presented at the Coloquio Internacional de Economía social y solidaria en un contexto de multiculturalidad, diversidad y desarrollo territorial, UNCuyo-Université Blaise Pascal – Mendoza.

- Gilbert, A. (2004). Helping the poor through housing subsidies: Lessons from Chile, Colombia and South Africa. Habitat International, 28(1), 13–40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0197-3975(02)00070-X doi: 10.1016/S0197-3975(02)00070-X

- Gough, K. V., & Kellett, P. (2001). Housing consolidation and home-based income generation: Evidence from self-help settlements in two Colombian cities. Cities, 18(4), 235–247. doi: 10.1016/S0264-2751(01)00016-6

- Greene, M., & Rojas, E. (2008). Incremental construction: A strategy to facilitate access to housing. Environment and Urbanization, 20(1), 89–108. doi: 10.1177/0956247808089150

- Gruis, V., Tsenkova, S., & Nieboer, N. (2009). Management of privatised housing: International policies & practice. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell Pub.

- Irarrazabal, I., Hairel, E. M. H., Wojciech, S., & Salamon, L. M. (2006). Estudio Comparativo del Sector Sin Fines de Lucro. Chile: John Hopkins University.

- Irarrazabal, I., & Streeter, P. (2016). Mapa de las Organziaciones de la Sociedad Civil 2015. In S. e. Accion (Ed.), Santiago, Chile: Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile.

- Lang, R., & Novy, A. (2014). Cooperative housing and social cohesion: The role of linking social capital. European Planning Studies, 22(8), 1744–1764. doi: 10.1080/09654313.2013.800025

- Larenas, J., Cannobbio, L., & Zamorano, H. (2016). Informe final de evaluación: Programa de Mejoramiento de Condominios Sociales y Programam de Regeneración de Condominios Sociales (ex Programam de Recuperación de Condominios Sociales, segunda oportunidad): Subsecretaría de Vivienda y Urbanismo, Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo. Retrieved from http://www.dipres.gob.cl/597/articles-149531_informe_final.pdf

- Larenas, J., & Lange, C. (Eds.). (2017). Temas emergentes para la política pública urbano habitacional en Chile. Documento de Trabajo INVI 6. Santiago de Chile: Institutio de la Vivienda, Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo, Universidad de Chile.

- Lee, Y. S. F. (1998). Intermediary institutions, community organizations, and urban environmental management: The case of three Bangkok slums. World Development, 26(6), 993–1011. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(98)00034-5

- Lewis, D. (2002). The management of non-governmental development organizations: An introduction David Lewis. London, UK: Routledge.

- Lewis, D. (2003). Theorizing the organization and management of non-governmental development organizations. Public Management Review, 5(3), 325–344. doi: 10.1080/1471903032000146937

- Liou, Y. T., & Stroh, R. C. (1998). Community development intermediary systems in the United States: Origins, evolution, and functions. Housing Policy Debate, 9(3), 575–594. doi: 10.1080/10511482.1998.9521308

- Marcuse, P. (1972). Home ownership for low income families: Financial implications. Land Economics, 48(2), 134–143. doi: 10.2307/3145472

- Marquez, F. (2005). De lo material y lo simbólico en la vivienda social. In A. Rodríguez & A. Sugranyes (Eds.), Los con techo: un desafío para la política de vivienda social. Providencia, Santiago de Chile: Ediciones SUR.

- MINVU (2014). Vivienda Social en Copropiedad. Catastro Nacional de Condominios Sociales. Santiago de Chile: Ministerio de Vivienda y Urbanismo.

- Moser, C. O. N. (1998). The asset vulnerability framework: Reassessing urban poverty reduction strategies. World Development, 26(1), 1–19. doi: 10.1016/S0305-750X(97)10015-8

- Moulaert, F., MacCallum, D., & Hillier, J. (2014). Social innovation: Intuition, precept, concept, theory and practice. In F. Moulaert, D. MacCallum, A. Mehmood, & A. Hamdouch (Eds.), The international handbook on social innovation: Collective action, social learning and transdisciplinary research. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Moulaert, F., MacCallum, D., Mehmood, A., & Hamdouch, A. (2014). General introduction: The return of social innovation as a scientific concept and a social practice. In F. Moulaert, D. MacCallum, A. Mehmood, & A. Hamdouch (Eds.), The international handbook on social innovation: Collective action, social. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Moulaert, F., Martinelli, F., Swyngedouw, E., & Gonzalez, S. (2005). Towards alternative model(s) of local innovation. Urban Studies, 42(11), 1969–1990. doi: 10.1080/00420980500279893

- Mullins, D., Czischke, D., & van Bortel, G. (2012). Exploring the meaning of hybridity and social enterprise in housing organisations. Housing Studies, 27(4), 405–417. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2012.689171

- Oosterlynck, S., Kasepov, Y., Novy, A., Cools, P., Barberis, E., Wukovitsch, F., … Leubolt, B. (2013). The butterfly and the elephant: Local social innovation, the welfare state and new poverty dynamics. ImPRovE. Poverty Reduction in Europe: Social Policy and Innovation (Vol. Discussion paper N.13/03).

- Ostrom, E. (2011). Background on the institutional analysis and development framework. Policy Studies Journal, 39(1), 7–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0072.2010.00394.x

- Pérez, A. (2009). Copropiedad Inmobiliaria. Precariedad y organización: el caso del condominio Quillayes de la comuna de La Florida (Masters dissertation). Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Santiago, Chile.

- Pizarro, R. (2010). El tercer sector en Chile: las organizaciones de acción social en el ámbito comunal (Doctoral dissertation). Universidad de Granada, España, Editorial de la Universidad de Granada. Retrieved from http://hera.ugr.es/tesisugr/1893014.pdf

- Pradel Miquel, M., Garcia Cabeza, M., & Eizaguirre Anglada, S. (2014). Theorizing multi-level governance in social innovation dynamics. In F. Moulaert, D. MacCallum, A. Mehmood, & A. Hamdouch (Eds.), The international handbook on social innovation: Collective action, social learning and transdisciplinary research. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Rodriguez, A., & Sugranyes, A. (2005). El problema de vivienda de los "con techo". In A. Rodriguez & A. Sugranyes (Eds.), Los con techo. Un desafío para la política de vivienda social. Providencia, Santiago de Chile: Ediciones SUR.

- Rohe, W. M., & Stegman, M. A. (1994). The effects of homeownership - On the self-esteem, perceived control and life satisfaction of low-income people. Journal of the American Planning Association, 60(2), 173–184. doi: 10.1080/01944369408975571

- Rolnik, R., Pereira, A., Moreira, F., Royer, L., Iacovini, R., Nisida, V., … Rossi, L. (2015). O programa Minha Casa Minha Vida nas Regiões Metropolitanas de São Paulo e Campinas: aspectos socioespaciais e segregação. Cadernos Metrópole, 17(33), 28. doi: 10.1590/18863

- Sabatini, F., Cáceres, G., & Cerda, J. (2001). Segregación residencial en las principales ciudades chilenas: Tendencias de las tres últimas décadas y posibles cursos de acción. EURE (Santiago), 27, 21–42.

- Salcedo, R. (2010). The last slum: Moving from illegal settlements to subsidized home ownership in Chile. Urban Affairs Review, 46(1), 90–118. doi: 10.1177/1078087410368487