Abstract

Does ‘informal’ housing offer more affordable choices for low-income renters in expensive cities? This paper investigates this question with reference to Sydney, Australia, where planning reforms have sought to deregulate housing development including ‘informal’ and low cost market accommodation, in response to chronic housing affordability pressures. Examining rental advertisements, housing supply and affordability data, and through interviews with local government personnel, we find that informal secondary units and room rentals dominate Sydney’s lower cost market, but rents remain high relative to incomes. Further, and despite reforms to encourage new secondary dwellings and low cost rental supply, substandard and non-compliant housing persists, exposing tenants to serious risks. The findings suggest that in high cost cities such as Sydney, the informal sector occupies an important and unrecognised role in housing low-income renters, but that more systemic reforms beyond the planning system are needed to improve housing outcomes for disadvantaged groups.

Introduction

Planning and ‘informality’ seem strange bedfellows, but there is a growing awareness of the role of the informal in shaping our cities and the contradictory need to accommodate it within more formalised planning processes. The term ‘informal’ has its roots in economy, with the informal sector often being defined as ‘unregulated by the institutions of society’ (Castells & Portes, Citation1989, p. 12). Although originally associated with cities of the global south, many scholars emphasise that ‘informality’ manifests as a global, heterogeneous phenomenon – a mode of urbanisation which occurs within and beyond formally regulated systems of development and commerce (Harris, Citation2018; Roy, Citation2005). These insights raise interesting questions about how formal land use planning regimes intersect with informality in urban development and housing markets.

With housing affordability pressures mounting across cities of the global north, ‘informality’ has particular resonance in the housing sector, where low-income earners are increasingly forced into substandard and precarious accommodation (Harris, Citation2018). In this sense, ‘informal’ housing is accommodation provided beyond the ‘formal’ regulations governing residential production (e.g. planning/zoning and building controls) and the housing market (such as property or tenure laws), with examples ranging from secondary units to room rentals or unpermitted dwellings (Durst & Wegmann, Citation2017; Wegmann & Mawhorter, Citation2017). Informal housing does not necessarily violate regulatory systems but is usually associated with some lower level of regulatory compliance (by owners, landlords or builders) or protection (for residents), which in turn reduces the costs of construction and or rent relative to the formal market. Secondary dwellings, which can be supplied on existing residential lots; or single room rentals, often created by subdividing an established home; are increasingly considered to be examples of informal housing in the global north, whether or not they comply with prevailing planning and building controls (Harris & Kinsella, Citation2017; Mendez, Citation2017).

Largely hidden within the wider housing market, demand for these informal options reflects a shortage of affordable alternatives in the formal private or social rental sector. Restrictive systems of planning regulation and land use zoning regimes are thought to contribute to this shortage by constraining new housing supply overall and by preventing traditional forms of diverse and lower cost rental accommodation in particular (Wegmann, Citation2015). Faced with onerous or costly planning controls, some property owners may deliberately contravene these regulations, either by necessity or because the potential profits from illegally produced accommodation exceed the risks of fines or other compliance action. Thus, a market for informal housing arises exposing residents to risks associated with poor quality accommodation produced beyond systems of building (and often rental) regulation. In this context there is growing interest in the potential to enable or legitimise existing and potential ‘informal’ dwelling options such as secondary dwelling units or boarding houses, as a strategy for both increasing the supply of low cost housing options within established residential areas while also ensuring that minimum standards are met (Bennett et al., Citation2019; Wegmann & Chapple, Citation2014).

This paper examines the role of such initiatives and the wider informal housing sector as an affordability solution for low-income renters in Sydney, Australia. Known as one of the world’s least affordable housing markets (Wetzstein, Citation2019), over the past decade Sydney has seen a series of policy efforts to address affordability, primarily through deregulatory planning reform intended to boost new housing supply (Gurran & Phibbs, Citation2016). Within this wider supply agenda, State Environmental Planning Policy (Affordable Rental Housing) 2009 (the ‘ARHSEPP’) sought to legitimise and encourage secondary dwelling units and boarding houses (single room rentals within a residential property) by overriding and dismantling local planning constraints. In addition to deregulating development standards, the ARHSEPP was supported by wider reform efforts to ‘cut red tape’ by allowing owner/developers to bypass public planning permit processes via private ‘certification’, a system of semi-privatised building control (Ruming, Citation2011). In this paper we review outcomes of these reforms within a wider analysis of housing supply trends in Sydney over the decade 2009–2019. We also draw on interviews with local government personnel and an analysis of 285 lower cost rental advertisements listed on Australia’s primary platform for housing, realestate.com.au, between June-September 2019. This commercial platform – operated by residential landlords and their agents – offered a rich insight into the types of lower cost housing and informality within Sydney’s private rental sector.

The first section of the paper situates the Sydney case within the emerging body of literature on informal housing practices within the global north. Next, the paper explains the methods and data sources for the study and introduces the context for housing supply and affordability concerns and policy responses in Australia overall and in Sydney in particular. Third, we present our key findings, examining the role and nature of informality in Sydney’s rental sector and discuss wider implications for understanding intersections between planning regulation/deregulation and informality within high cost housing markets.

Understanding ‘informal’ housing in the global North

The present era of hyper-commodification of housing has meant that private rental is an increasingly important sector of the housing system, both for higher income earners unable to afford home ownership and lower income groups no longer able to access a shrinking supply of social housing. In this context there have been rising concerns about conditions endured by low-income households in poorly regulated and deteriorating rental accommodation throughout the world. In high cost global cities, such as London and New York, exclusive property markets co-exist with a rise in illegal ‘beds in sheds’ (Edwards, Citation2016) and perilous apartment subdivisions (Elliot, Citation2019).

Classifying informal housing types

In simple terms, informal housing bypasses ‘formal’ regulatory systems of production or tenure because these rules are too onerous, costly, and/or the potential profits are high. Secondary dwellings, boarding houses, as well as mobile or manufactured home estates and other non-conventional housing types are increasingly referred to in the literature as informal (Durst & Sullivan, Citation2019; Kinsella, Citation2017; Mendez, Citation2017) whether or not they meet regulatory requirements, because they challenge predominant conceptions of the single family home and household unit; typically involve different processes of residential production (financing and construction); often involve some negotiated sharing of spaces or facilities; and may be occupied by a negotiated or ad hoc rental arrangement.

A threefold classification to describe informal housing types in the United States (US) is proposed by Durst and Wegmann (Citation2017). They distinguish between informal housing as ‘non-compliance’ with regulatory regimes such as planning and building laws; as ‘non-enforcement’ of those rules, due either to selective action by the state or insufficient resources; or as a product of deliberate state ‘deregulation’ (Durst & Wegmann, Citation2017, p. 284). In practice these categories are likely to be overlapping but offer helpful conceptual distinctions between the ways in which informal housing may violate planning and building laws; various state responses to tolerate or prosecute these violations; and the dynamic ways in which existing regulations may be rewound to legitimise existing, and enable new, forms of informality in the housing market. In the US at least twelve states have enacted reforms to enable ‘accessory dwelling units’ (ADUs) in residential areas, while the American Planning Association promotes a model local code (Brinig & Garnett, Citation2013). In Long Island, New York a variety of local initiatives promote accessory dwellings as a form of local workforce accommodation (Anacker & Niedt, Citation2019). By 2014, nearly 80% of Canadian municipalities had implemented regulations to permit secondary suites such as basement apartments, laneway cottages, and other subdivisions of single family houses (Harris & Kinsella, Citation2017).

Many caution that deregulation to legitimise informal housing in the global south has been associated with real estate speculation and redevelopment (Durst & Wegmann, Citation2017). This is a potential risk in global north contexts as well, where deregulation of planning and building controls pertaining to housing may perversely commodify secondary and informal dwelling units, ‘freeing up’ new opportunities for capital investment and gentrification of lower cost residential neighbourhoods (Mendez & Quastel, Citation2015).

Further, initiatives to formalise informal housing does not necessarily reduce the prevalence of non-complying accommodation. Reflecting the challenges and dilemmas of local regulatory enforcement, Harris and Kinsella (Citation2017) estimate that up to half of Canada’s secondary units remain inconsistent with zoning or other local rules. Undoubtedly, some non-complying accommodation is of adequate standard for lower income earners who have limited choices in the housing market. But in many cases informal and non-complying units have been found to expose vulnerable residents to social stigma, privacy and security concerns, as well as serious health or safety risks (Goodbrand & Hiller, Citation2018).

Informality, enforcement, and practice

Government tolerance of informal housing reflects a wider failure to address unmet housing need (Tanasescu et al., Citation2010). For instance, providing ‘secondary suites’ in subdivided houses is often an important strategy for first home buyers to qualify for mortgage finance (Mendez, Citation2016) and serves an important role for lower income extended families and immigrant communities (Mukhija, Citation2014). In many cases, proactively enforcing planning or building regulation would likely result in the loss of a significant source of lower cost housing (Harris & Kinsella, Citation2017). Thus, even non-compliant, substandard accommodation may be tolerated in the absence of other alternatives (Tanasescu, Citation2009). On the other hand, the potential for serious harm to occupants of substandard housing and the uncertain legal liability of regulatory bodies, may provoke an officious response. In the UK it has been argued that reactions to ‘shed housing’ and similar accommodation produced without planning consent has been to criminalise both the inhabitants and producers rather than acknowledge systemic policy failure that results in poverty and housing stress (Lombard, Citation2019).

Drawing on a media analysis and interview data, Lombard (Citation2019) argues that structural factors common to cities of the global north – unaffordable housing markets and neoliberal economic reforms – are downplayed in a discourse that characterises shed housing inhabitants as ‘illegal immigrants’ and providers as ‘rogue landlords’ (Lombard, Citation2019, pp. 569). Lombard contends that conceptualising informality as a ‘practice’ encompasses the structural factors producing unmet housing need; the regulatory framework in which legality is defined and enforced; as well as the agency of landlords and tenants operating within these wider economic and legal conditions (ibid, p. 571).

Investigating and recognising informality in housing systems

Attempts to investigate informality in housing systems of the global north are complicated by the deliberately concealed nature of informal housing development. Detailed field work is often needed to understand localised expressions of informality within seemingly formal and highly regulated residential neighbourhoods. For instance, illegal secondary units have long been concealed within single family zones, comprising a ‘horizontal density’ in the ‘cityscapes’ of California (Wegmann & Chapple, Citation2014). The advice of a local building inspector was critical in identifying non-compliant housing in the city of Los Angeles (Wegmann, Citation2015) while in Canada, a ‘field method’ for discerning unauthorised secondary dwellings focused on excess letter-boxes, garbage bins and vehicles (Kinsella, Citation2017). However, precisely quantifying the total number of informal housing units across a housing system is very difficult. Attempting to measure illegal housing production in California, Wegmann and Mawhorter (Citation2017) compare dwelling growth between census periods, against records of permitted homes, estimating that informal units extended California’s existing housing stock by around 0.4% per year between 1990 and 2010. In the context of overall new housing supply, this seemingly small and incremental production of informal dwellings was found to be equivalent to around a third of permitted homes over the period (Wegmann & Mawhorter, Citation2017). The scale of informality in the Australian housing system remains unknown; however, a recent scoping study found that non-complying dwelling units pervade parts of Sydney, with one local municipality reporting around 960 notifications in 2018 alone (Gurran et al., Citation2019).

Studying informality in Sydney’s rental housing market: case study and research approach

Building on this work to further examine informality in Sydney’s rental housing market, we drew on two primary data sources: online real estate advertisements for lower cost private rental accommodation in Sydney as well as interviews and a focus group with local government informants responsible for enforcing planning and building regulations. We situated this data within the wider context for new housing supply in Sydney and the implementation of the planning reforms to deregulate residential housing development and privatise building control.

Review of online rental advertisements

Online real estate platforms can offer rich insights into the housing market (Boeing & Waddell, Citation2016). For this study, we examined low cost rental advertisements on a major real estate platform (realestate.com.au) to explore the types of housing options, including non-conventional and informal housing types, being supplied in Sydney’s low cost rental sector. Realestate.com.au is Australia’s top ranked property platform (with over 36 m views per month; Similar web Analytics 2020) and advertises residential properties for sale and rent, with detailed text descriptions, geographical data, as well as photographic images of each property. Our search was confined to rental listings within the suburbs comprising metropolitan Sydney, which necessitated a series of individual search queries applying to sub regional groupings across the Inner West; East (including the Central Business District), South, South West, West, and Northern Beaches.

After experimenting with automatic data extraction (‘web scraping’) methods, we elected to review advertisements manually because of the detailed textual and visual data contained in each listing. Not suitable for auto-categorisation, each listing included a variable text description, address and map reference (including access to Google Earth imagery) as well as property photographs. Commonly, 3–8 photographs were posted, showing the exterior as well as interior of the accommodation. A threshold of $300 was applied to the search criteria, excluding properties advertised beyond the affordable rental band for low-income singles in Sydney. Low-income renters are defined as those earning up to $850 per week (which is 40% of the median weekly wage), meaning that an ‘affordable’ rent would be up to $255 per week (30% of gross income) (NSW Government, Citation2019). We expanded the rental threshold beyond $255 to reflect the reality that many low-income earners in the private rental market are forced to pay more than the 30% affordability benchmark. A total of 285 advertisements meeting this rental criteria were reviewed, between June and September 2019.

Interviews and focus group discussion with local government informants

To further understand informality in Sydney’s rental housing market, we drew on interviews and a focus group undertaken with seven local government participants across inner and middle/outer suburban areas, including a planner, five building inspectors (responsible for compliance with planning and building law), and an elected representative. Additionally, a focus group was held with a different cohort of building inspectors, each from the same five local government areas to test the initial findings by the research team. Participants were identified via a snowball method whereby two local government research partners nominated initial interviewees, who then referred the research team to counterparts in other local jurisdictions (see Gurran et al., Citation2019, for further information about the wider study). Overall, the interviews and focus group explored the drivers, nature, and scale of informal housing, risks associated with particular types of regulatory violation, and processes of enforcement. We also consulted our informants about ways to classify the different forms of low cost rental accommodation which may fall within the umbrella of informality. Notably, our local government informants were uncomfortable with the term ‘informal’ as a way of describing housing which violates planning or building regulation. With their responsibility for enforcing health, safety, and building legislation alongside planning controls, local compliance officers preferred terminology such as ‘illegal’ to describe clear breaches in these rules, ‘non-complying’ to refer to accommodation which could potentially be brought to standard, and ‘un-permitted’ to describe housing which lacks appropriate permission but which does not directly threaten the health and safety of occupants. In this paper we use the term ‘informal’ housing in a much wider sense, extending beyond the defined legality/illegality of residential dwelling units to encompass a range of irregular rental units and practices.

There are some inevitable limitations with our research approach. Firstly, it was not possible to fully verify the accuracy of the online rental advertisements. Actual contracted rents may be lower, or higher, than advertised; while the quality of accommodation may be better, or worse, than appears in listings photographs. Further, the data is point of time (rental listings across each area of metropolitan Sydney were surveyed only once) rather than cumulative, meaning that the data set is not a complete listing of available rental properties within the affordability parameters set over the four month time frame. As our source is a single real estate platform, it is not possible to fully situate the data set as part of the wider supply of private rental accommodation in Sydney or even to assert a proportion of the wider informal rental supply, given the variety of other platforms and arrangements by which such housing comes onto the market. However, these limitations are partially offset by our access to local government informants able to provide additional insights into the nature and role of informality in Sydney’s rental market.

Planning reform and informal housing supply in Sydney

By the turn of the new millennium, housing affordability was a matter of national policy concern in Australia. Long a nation of home owners, by 2016, home ownership had begun to slide, falling from around 70% of households to around 65%, with even high-income first home buyers struggling to save the deposit for an entry level property in Australia’s major cities (Hulse et al., Citation2019) . Largely shut out of a highly residualised social housing sector, low-income renters face chronic affordability stress, particularly in cities where nearly half pay over 30% of their income on rent (ABS, Citation2019). In Sydney, the nation’s largest city (at just over 5 million people), the loss of low cost rental housing as well as concerns about inadequate new supply have been a policy focus for at least three decades (Gurran & Phibbs, Citation2016).

With planning system constraints seen to prevent new housing supply and worsen affordability, deregulating local planning regimes has been a major emphasis of government policy (Gurran & Phibbs, Citation2016; Yates, Citation2016). In NSW, planning reforms enacted since the early 2000s elevated the State government’s power over local planning authorities (Ruming, Citation2011), allowing direct intervention through land release, residential upzoning, and major development decisions. Further, as noted, the state’s development permitting system was partially privatised, with accredited private certifiers employed by the developer/client able to issue low impact planning permissions and certify construction through to occupation.

More specifically targeting affordability, the introduction of the State Environmental Planning Policy (Affordable Rental Housing) 2009 (ARHSEPP) established a State-wide framework for permitting secondary dwellings and boarding houses (single rooms of at least 12 square metre dimension) (). Further, the system of private certification was extended to secondary dwellings, while boarding houses in residential flat zones benefit from a density bonus.

Table 1. ‘Informal’ housing under the Affordable Rental Housing State Environmental Planning Policy 2009 (ARHSEPP 2009).

Critically, the ARHSEPP sought to stimulate a new rental market in secondary dwellings and in build to rent micro apartments. The policy was actively marketed to landlords as a low cost strategy for increasing their rental yields, and companies began to advertise secondary dwelling installations for between $AU 70,000 and $110,000 (Farrelly, Citation2019). With rental returns expected between $300 and $700 per week, secondary dwellings represent a high yield on investment as well as a significant increase in total property value. Similarly, the density bonus for boarding houses was designed to encourage a new ‘build for rent’ development type; again with relatively low land and capital investment but high rental returns.

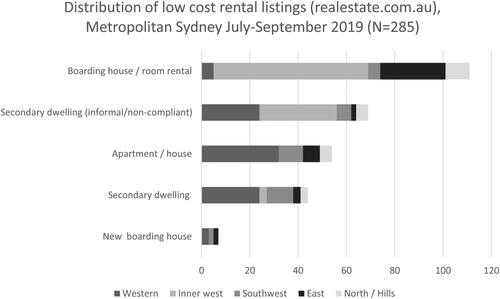

Outcomes

Sydney’s housing supply outcomes over the decade 2007/08-2015/16 are summarised in . As shown, Sydney’s overall housing output rose over the period, more than doubling by 2015-16. This increased housing development may be interpreted as an outcome of the state’s wider deregulatory reform agenda but undoubtedly a strong driver has been a rising property market inflamed by falling interest rates and buoyant population and economic growth. However, increased supply of housing in the market largely failed to ease affordability pressures (Ong et al., Citation2017) and in fact the supply of rental units affordable to low-income earners in Sydney actually declined over the period (Hulse et al., Citation2019).

Figure 1. Greater Sydney dwelling approvals 2007/08-2015/16.

Source: the authors, compiled from (NSW Department of Planning and Environment Various years)

Within this wider housing production, secondary dwelling units became an increasingly important component of new supply. By 2015/16, over 7,000 secondary dwelling units were approved in across greater Sydney alone, equivalent to 13% of total housing supply for that year.

In addition to secondary dwellings, new boarding houses have become a small but increasingly important component of residential development in Sydney, again enabled by the ARHSEPP. Data on new boarding houses are limited and not systematically reported by state or local governments. Available information suggests a significant expansion in inner Sydney, where 86 applications for new boarding houses were approved between 2009 and 2017, and an additional 17 properties were expanded, comprising a total of 5,819 rooms (Troy et al., Citation2018b, p. 20). Qualitative evidence suggests that the new boarding house typology is becoming increasingly popular with developers, able to achieve a high dwelling yield with strong rental returns at much lower land and construction costs (Troy et al., Citation2018a). However, an ongoing concern is that despite the policy intention to increase affordable rental housing, there are no requirements for boarding house rents to be set at an affordable rate, nor eligibility criteria targeting the accommodation to those on low incomes. Rather, as with secondary dwellings, rents are determined by the market. The exception is when boarding houses are developed by registered non-profit providers who are funded to subsidise rents for eligible low-income households.

Low cost private rental accommodation: review of rental advertisements

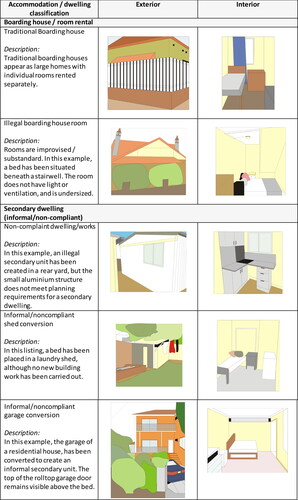

To what extent do these newly supplied units – secondary dwellings and boarding house rooms – contribute to Sydney’s low cost rental housing market, along with other types of accommodation? To investigate this question, we classified the data set of online real estate advertisements into five primary categories (summarised in ).

Figure 2. Secondary dwellings and boarding houses, Sydney’s low cost rental listings.

Source: The authors; with composite images drawn by Pranita Shrestha.

Boarding houses or ‘room rentals’ are rooms within residential properties offering shared facilities only. Of these, some accommodation is clearly non-compliant with basic building code requirements – for instance lacking natural light or ventilation; but in general boarding houses and room rentals are older style residential accommodation which may or may not meet contemporary planning standardsFootnote1. New boarding house accommodation, apparently consistent with the rules of the ARHSEPP was able to be classified because of the size of the room and the amenities (kitchenette and en-suite bathroom).

Secondary dwellings appear as self-contained accommodation within a primary residential site; usually, but not always, detached from a separate house and apparently consistent with the general requirements of the ARHSEPP. Informal or non-compliant secondary dwellings have obvious breaches of planning and building requirements, for instance, created within outbuildings, garages, or garden sheds, and lacking appropriate insulation, electricity, stormwater, or access provisions. shows indicative images of boarding houses and secondary dwellings, drawing on listings advertisements to show examples of traditional and new boarding house developments and rooms; as well as examples of compliant and non-compliant secondary dwellings. ‘Apartments’ and ‘houses’ were the final listing category, used to describe conventional cottages or self-contained multi-unit accommodation of a larger size than boarding house rooms.

Notably, listing descriptions of dwelling type varied – room rentals are sometimes described as ‘boarding houses’; ‘share house’; or even ‘house’; while secondary dwellings are often advertised as ‘unit’, ‘house’ and ‘granny flat’. By inspecting the photographic imagery, it was generally possible to classify the accommodation, with some exceptions. In cases of ambiguity, the research team used the property address to locate relevant planning approvals to determine and categorise authorised uses. If there were obvious breaches or no permission relating to a secondary dwelling or boarding house was located, the listing was classified as non-compliant.

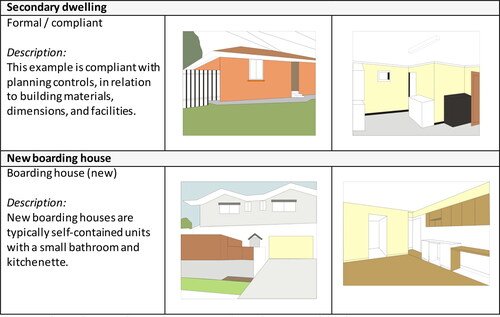

This analysis confirmed that informal housing in the form of boarding houses and secondary dwellings is an important part of Sydney’s lower cost rental supply. As shown in , nearly 40% of the 285 rental listings under $300 can be classified as boarding house rooms (i.e. rooms in older residential dwellings, without an en-suite bathroom), or single rooms for rent within a larger residential house. Both are similarly priced at around $140 per week; which would be technically ‘affordable’ for a single person at the top of the very low-income band ($530 per week). Affordability in Australia is defined with reference to income bands (with very low-income households at the bottom 20% of the income range and low-income earners on up to 40%); while rents are said to be affordable if they cost up to 30% of total income. Nevertheless, online availability of these very low cost rooms is low; with the median offering at $255 per week which would place low-income earners into housing stress. Rooms in new boarding houses offer a higher standard of accommodation but account for a much smaller proportion of the advertised rental accommodation under $300 (2%) and start at $230 per week.

Table 2. Weekly rent and composition of lower cost rental listings snapshot, Realestate.com.au, July–September.

Secondary dwellings were found to comprise a similar proportion of lower cost rental supply (39%). Of this, less than half (44) dwellings appear to comply with planning and building controls, while 69 units exhibit signs of non-compliance, many demonstrating a serious breach, such as the uninsulated metal shed conversion shown in . Even so, rents for these non-complying units remain unaffordable for those on very low incomes (at a median of $220 per week, ).

shows the spatial distribution of these housing types in Sydney. The majority of listings under the $300 rental threshold which meet more standard criteria (self-contained houses or apartments), are all located in the lower cost housing markets of the outer Western and South western suburbs, at significant distance from employment opportunities and public transport. Boarding house advertisements are clearly clustered in Sydney’s Inner West. Informal and non-compliant secondary dwellings prevail in both the Inner West and Western suburbs, which also appears to advertise the largest supply of compliant secondary dwelling units within the affordability threshold.

Local government perspectives: informal but not affordable

The finding that informal and non-compliant housing comprise a significant proportion of Sydney’s lower cost private rental market was consistent with the advice provided by local government interviewees. They reported rising complaints about non-compliant dwellings, subdivided apartments, and unsafe boarding houses in their localities while describing the dilemmas associated with enforcing regulations which may cause vulnerable tenants to lose their homes. Many were critical of the outcomes of the NSW planning reforms, particularly in relation to the deregulation of local controls for secondary dwelling units and the privatisation of building control functions, which they associated with a rise in poor quality housing. Ironically, many were of the view that the ARHSEPP had contributed to gentrification, by encouraging the redevelopment of older, lower cost rental housing into new, self-contained units. These new units were typically targeted to students or single professionals in a higher segment of the rental market than served by traditional boarding house accommodation.

Risks of non-compliance within the informal sector

Of the 69 informal or ‘non-compliant’ secondary dwellings in our sample of listings, many appeared to present significant health and safety risks for occupants. As shown in , such risks might relate to inadequate construction materials, building separation, or un-permitted internal modifications resulting in rooms without ventilation or light. Drawing on their local experience, building inspectors described similar violations.

Most times it is actually a shed, a garage, or another structure that’s been converted and most times not to standard.

We've got fully enclosed rooms, say bedrooms, with no external windows to provide light and ventilation and so on. Walls that are close to the boundary that aren't fire rated, that in the event of a fire, fire can rapidly spread from the unauthorised building to any adjoining properties.

There's ones that are basically shanty buildings, we even had a granny flat built out of the insulated freezer panels, cool rooms, and they used that as the walls.

Building inspectors advised that operators seek to increase rental yields by creating new rooms through partition walls or by repurposing living spaces, stair cavities (), or even laundries.

One of the things that we're finding more and more and more increasing is the existence of illegal boarding houses. … Obviously people have realised that their rental return for a secondary dwelling, they can multiply that by five or six on a large house.

Informal boarding houses present particular risks to health and safety in the event of a fire.

The firies would go, I know if I've got to respond to that building I've got to double up on the appliances I send out because there's going to be twice as many people in that building than there should be.

Local government informants described serious hazards associated with substandard electricity or construction work; exposure to extreme temperature and weather in properties not designed for residential habitation; as well as poor siting leading to wastewater, flooding, and proximity to bushfire zones.

Well, you might have someone that's done an illegal connection to the sewer and it in itself then creates problems for other people downstream because of how it was done, or upstream. The other thing that may happen is they may build something over the top of a sewer line or a storm water line.

A lot of these unauthorised buildings are flat on ground and they're in high risk flood areas. If they were to be built according to code, they would have a minimum level of floor and there would be evacuation procedures for how they get out if there's a flood.

In some areas, you will have issues with bushfire prone land, where these things are in backyard and they're in the fire separation area between the house and bush.

Despite these deficiencies, interviewees were acutely aware that with rents typically exceeding $200 per week, substandard and non-compliant housing is not necessarily affordable to low-income earners.

Privatisation of building control and dilemmas in local enforcement

Local informants advised that informal dwellings usually come to light as a result of neighbour complaints (particularly of excessive noise, parking impacts, waste management). Signs of obvious additional occupation, such as additional letter boxes, garbage bins, or unusual fencing will also prompt local compliance staff to examine property records for secondary dwelling permits. Investigating breaches of residential planning and building control is slow, because local government compliance officers must follow strict protocols before being permitted to inspect residential properties. Property owners, and then their tenants, must be notified before an inspection can occur, by which time evidence of residential occupation is often removed.

Interviewees advised that the unauthorised and substandard accommodation they encounter is typically being created and marketed by rental landlords rather than by families seeking to meet their own housing needs.

So to some extent, I guess we tend to be a bit more sympathetic towards someone trying to provide for an expanding family, but increasingly we find that people, for example, from the eastern suburbs, are buying up properties here in the west and going ahead with borderline developments and unauthorised developments in this area.

Several interviewees were of the view that the reforms to allow private certification (which has reduced local enforcement capacity) has contributed to a worsening of conditions at the bottom of the rental market. Interviewees described how multiple dwelling units were occurring illegally within the framework of a permitted plan of works – with the system of private sector ‘certification’ providing cover for subsequent conversion of ‘garages’ and ‘studios’ into additional apartments.

A lot of these places, they might get approval for a legitimate secondary dwelling, it will [also] have a studio, storage, whatever you want to call it, attached to it, which is allowable … that becomes another secondary dwelling, and they'll carve up the house to add another one or two.

Unscrupulous operators familiar with regulatory frameworks but motivated by the potential profit associated with providing illegal accommodation were known to continually reoffend, preferring to pay a fine and resume operations. As reported in the international literature, interviewees explained the difficulties associated with gaining access to inspect residential homes (Tanasescu, Citation2009), contributing to the sense of impunity by which some landlords repeatedly flouted regulations.

Interviewees advised that stronger compliance and enforcement processes, while potentially important for health and safety concerns, would not fundamentally address the drivers of informal and illegal housing production in their areas. They perceived these drivers to stem from the problem of unmet housing need and the market that has evolved to capitalise on this need.

There is no alternative, the market will always provide where there's a buck to be made. So we - you know, … we're all for affordable housing, but not exploitative housing, and that's what's happening so people can make a buck.

Compliance officers described being caught between their statutory duties to enforce planning and building regulations designed to manage very real risks to health and safety, against the wider housing needs of vulnerable tenants.

The other side of the coin there is if you are bloody minded about it you go down and say, no, get out, you're creating a situation where what are they going to do? Live in a park, live in an underpass? So which is better?

Deregulation and planned ‘informality’

By deregulating local controls on secondary dwellings and boarding house developments, it was hoped that the ARHSEPP reform would promote a better quality source of low cost market accommodation. However, interviewees advised that the policy did not appear to be working in this way. Rather than contributing to the lower cost rental stock interviewees advised that newly constructed secondary units typically rented to a higher end sector of the rental market, including short term rentals on Airbnb style platforms. At the same time, in high cost suburbs, even non-complying units or very basic secondary dwellings could be very expensive.

The affordable SEPP [ARHSEPP] is a nonsense insofar as we've got garages being released out for $500 a week. It's not low cost affordable housing.

Paying, $400, $500, $600 a week for effectively a one-bedroom garage is not affordable housing, in no way - no matter what way you look at it. So the intent of what affordable housing and the SEPP was supposed to bring about isn't. It's not me building a granny flat for my elderly parents or my teenagers or my newly married daughter until they get on their feet.

Interviewees perceived the ARHSEPP reforms as having paved the way for increased real estate speculation with investor/landlords exploiting those at the bottom of the market.

This is actually creating almost a new underground economy for people that are building these things, whether they have approval or not, and then exploiting the people.

Similarly, interviewees cautioned that, rather than providing lower cost rental accommodation for a wider population, the new boarding house developments were more likely to be rented at an unaffordable rate to students, and in fact were increasingly associated with a variation of gentrification known as studentification or student-led gentrification (Smith et al., Citation2014).

We're losing the old boarding houses and we’re getting a lot more new generation boarding houses, which are targeted at the student market … and which certainly aren’t affordable. Which are perhaps even more expensive than one bedroom apartments.

Discussion: Did the deregulatory planning reforms support low cost rental housing?

One of the key questions examined in this study was whether relaxing residential development rules might encourage new lower cost housing production, reducing demand for, and supply of, illegal and substandard rental accommodation.

Despite the introduction of legal pathways to simplify and formalise the development of these forms of accommodation, the data presented here suggests that unauthorised and illegal dwelling units comprise a significant proportion of the housing available to those on low and very low incomes in Sydney. Indeed, perhaps perversely, our interviewees suggested that the rise in ‘state sanctioned’ informality – the deliberate ‘de-regulation’ described by Durst and Wegmann (Citation2017) was mirrored by a rise in illegal dwelling production – in the form of converted garages and sheds, and illegal room rentals. Local government informants believe that the codification of informal dwelling types has encouraged a shadow market of unauthorised and substandard housing supply. That this substandard market has persisted despite the introduction of alternative regulatory pathways for affordable housing production in the form of secondary dwelling and boarding houses is a key finding of this study. A second key finding is that even these non-compliant accommodations are being provided at a cost that is unaffordable to very low-income earners further highlighting that informal housing should not be equated with increased affordability.

At the same time, this informal sector of the housing system offers vulnerable households accommodation and agency which might not otherwise be available. The furtive nature of informal or non-conventional accommodation provides a perverse security for those unable to access other forms of housing. These potential benefits must be weighed against the fact that many of the housing types uncovered in this analysis represent serious health and safety risks to occupants; exposing them to severe temperatures and weather; increased danger in case of fire; and higher risk of accident and injury from substandard electrical or construction works.

A broader finding is that deregulatory initiatives which depend on increased real estate investment to deliver lower cost rental housing supply may perversely hasten the loss of existing affordable accommodation. The interview data and review of rental advertisements undertaken for this research adds evidence to concerns that the ARHSEPP has facilitated the conversion and loss of traditional boarding house accommodation. Despite considerable development of new boarding houses, this study implies an almost negligible contribution to the supply of low cost rentals in Sydney (2%) relative to traditional boarding houses, room rentals and secondary dwellings, which collectively accounted for 78% of the rental listings reviewed. By contrast, these traditional types of informality are at greater risk of redevelopment facilitated by the package of ARHSEPP and wider planning reforms to deregulate and privatise residential development control.

Conclusion

This paper has examined the role of informal housing in Sydney, one of the world’s wealthiest cities and most expensive property markets. With low-income renters increasingly dependent on substandard and precarious accommodation, the NSW state government rolled out an ambitious planning reform agenda designed to overcome barriers to new housing supply overall and affordable housing in particular. Deregulating local residential controls seen to inhibit secondary dwellings and new boarding houses was a key element of the planning reforms, which, combined with a privatisation agenda to reduce compliance and enforcement functions of local government. Despite a significant growth in new housing production overall, including a marked increase in secondary dwellings as a proportion of new supply, Sydney’s shortage of low cost rental accommodation has persisted and grown. Further, our analysis of lower cost rental listings reveals that the accommodation that is available fails basic standards of safety and amenity.

More widely, as seen in the case of Sydney, demand for informal (particularly non-compliant and substandard) housing in the global north can be understood as a product of state failures to meet the needs of lower income groups within a wider context of housing financialisation and the restructuring of the welfare state under neoliberalism. At the same time, traditions of informal housing provision through adjustments to single family homes, offer important and flexible opportunities for home owners and lower income earners, while single room occupancy and boarding house accommodation can support housing choice and affordability in residential neighbourhoods. Local stigma and resistance to these types of housing can and is increasingly being overcome by overarching planning frameworks set by central governments – such as the ARHSEPP reforms in NSW. However, the outcomes of reform efforts designed to overcome restrictive constraints to these accommodation types – in terms of the quantity, quality, and affordability of informal rental housing remains unclear. In particular, it seems that in some cases relaxing residential development rules may encourage new housing development at a lower cost to producers. But without interventions such as affordability requirements, this housing is likely to serve a more profitable segment of the market – from higher income renters to global tourists seeking short term accommodation. It seems unlikely to reduce demand for, and supply of, illegal and substandard rental units.

As shown in this study, informal housing options can play a critical and positive role in the housing system but are no substitute for a properly subsidised and regulated social and affordable rental sector. Informal housing approaches may be most appropriate when produced directly by households to meet their specific needs, and/or used as a flexible relief valve as transitional rental accommodation within tight housing markets. Informal housing does not have to be precarious. A formal scaffold of appropriate design/construction methods is needed as are baseline tenancy rights and protections, enforced by adequately resourced local government compliance officers and housing support workers. Local enforcement strategies such as fines for failing to maintain adequate building standards should be reviewed along with clear education and communication strategies designed to inform home owners, landlords, and tenants about regulatory obligations and rights. Governments must remove the market for substandard accommodation by intervening to support and enforce appropriate and affordable housing for all. This type of planning, combined with adequate support for social housing and rental tenancy protections, includes informal responses as part of the affordable housing solution, rather than problem.

Overall, this paper contributes to the emerging literature on informal housing in the global north through a rich, empirically based case study of secondary dwellings and boarding houses in Sydney. Echoing and extending the threefold classification of informality via ‘non-compliance’, ‘non-enforcement’ or ‘deregulation’ proposed by Durst and Wegmann (Citation2017, p. 284), the Sydney case highlights the sharp dilemmas facing policy makers and local authorities seeking to preserve housing standards without further marginalising the urban poor, even in wealthy global north nations with seemingly strong systems of regulation and enforcement. The paper also contributes to wider discussions on urban informality and its correlation with affordability, corroborating notions of informal housing as a distinctive type of market where affordability accrues in the absence or inability of formal planning and regulation (Roy, Citation2005). This understanding of informality highlights the failure of financialised housing markets to accommodate lower income renters, while urban planning regimes – whether overly stringent, bypassed, or deregulated – further marginalise the disadvantaged.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 We note that traditional forms of boarding house accommodation – rooms rented to individuals who share kitchen and bathroom facilities – continue to be provided across Sydney, and are regulated under NSW law. Properties renting five or more rooms are required to be registered, although they do not require additional planning approval unless new works are being proposed. All must comply with prescribed health and fire regulations which are more onerous than those applying to single residential dwellings.

References

- ABS (2019). Housing occupancy and costs, 2017–18. Canberra Australian Bureau of Statistics.

- Anacker, K. B., & Niedt, C. (2019). Classifying regulatory approaches of jurisdictions for accessory dwelling units: The case of long Island. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 0, 0739456X1985606. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X19856068

- Bennett, A., Cuff, D., & Wendel, G. (2019). Backyard housing boom: New markets for affordable housing and the role of digital technology. Technology|Architecture + Design, 3, 76–88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/24751448.2019.1571831

- Boeing, G., & Waddell, P. (2016). New insights into rental housing markets across the United States: Web scraping big data to analyze craigslist. Journal of Planning Education and Research. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X16664789

- Brinig, M. F., & Garnett, N. S. (2013). A room of one's own: Accessory dwelling unit reforms and local parochialism. Urban Law, 45(3), 519–569.

- Castells, M., & Portes, A. (1989). World underneath: The origins, dynamics, and effects of the informal economy. The informal economy: Studies in advanced and less developed countries 12.

- Durst, N. J., & Sullivan, E. (2019). The contribution of manufactured housing to affordable housing in the united states: assessing variation among manufactured housing tenures and community types. Housing Policy Debate, 29(6), 880–898. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2019.1605534

- Durst, N. J., & Wegmann, J. (2017). Informal Housing in the United States. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(2), 282–297. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12444

- Edwards, M. (2016). The housing crisis and London. City, 20(2), 222–237. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2016.1145947

- Elliot, K. (2019). Tiny NYC condo split into 9 ‘micro units’ with illegal second floor, city says. Global News.

- Farrelly, K. (2019). What you need to know before building a granny flat. Sydney Morning Herald.

- Goodbrand, P. T., & Hiller, H. H. (2018). Unauthorized secondary suites and renters: a life course perspective. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 33(2), 263–279. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-017-9559-0

- Gurran, N., & Phibbs, P. (2016). Boulevard of broken dreams': Planning, housing supply and aff ordability in urban Australia. Built Environment, 42(1), 55–71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.42.1.55

- Gurran, N., Pill, M., & Maalsen, S. (2019). Informal accommodation and vulnerable households in metropolitan Sydney: Scale, drivers and policy responses. Sydney Policy Lab.

- Harris, R. (2018). Modes of informal urban development: A global phenomenon. Journal of Planning Literature, 33(3), 267–286. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412217737340

- Harris, R., & Kinsella, K. (2017). Secondary suites: A survey of evidence and municipal policy. The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe Canadien, 61(4), 493–509. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12424

- Hulse, K., Reynolds, M., Nygaard, C., Parkinson, S., & Yates, J. (2019). The supply of affordable private rental housing in Australian cities: short and longer term changes. AHURI Final Report Series Report, (323). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18408/ahuri-5120101

- Kinsella, K. (2017). Enumerating informal housing: A field method for identifying secondary units. The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe Canadien, 61(4), 510–524. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12429

- Lombard, M. (2019). Informality as structure or agency? Exploring shed housing in the UK as informal practice. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 43(3), 569–575. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12705

- Mendez, P. (2016). Professional experts and lay knowledge in Vancouver’s accessory apartment rental market. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 48(11), 2223–2238. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X16657550

- Mendez, P. (2017). Linkages between the formal and informal sectors in a Canadian housing market: Vancouver and its secondary suite rentals. The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe Canadien, 61(4), 550–563. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/cag.12410

- Mendez, P., & Quastel, N. (2015). Subterranean commodification: informal housing and the legalization of basement suites in vancouver from 1928 to 2009. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(6), 1155–1171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12337

- Mukhija, V. (2014). Outlaw in-laws: Informal second units and the stealth reinvention of single-family housing. : MIT Press.

- NSW Government (2019). Median Incomes 2019–20. https://www.facs.nsw.gov.au/providers/housing/affordable/manage/chapters/household-median-incomes-2019-20.

- Ong, R., Dalton, T., Gurran, N., Phelps, C., Rowley, S., & Wood, G. (2017). Housing supply responsiveness in Australia: distribution, drivers and institutional settings. AHURI Final Report AHURI, (281). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18408/ahuri-8107301

- Roy, A. (2005). Urban informality - Toward an epistemology of planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 71(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360508976689

- Ruming, K. (2011). Cutting red tape or cutting local capacity? Responses by local government planners to NSW planning changes. Australian Planner, 48(1), 46–57. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07293682.2011.530588

- Smith, D. P., Sage, J., & Balsdon, S. (2014). The geographies of studentification: ‘Here, there and everywhere. ? Geography, 99, 116–127.

- Tanasescu, A. (2009). Informal housing in the heart of the New West: An examination of state toleration of illegality in Calgary. North American Dialogue, 12(2), 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4819.2009.01022.x

- Tanasescu, A., Wing-Tak, E. C., & Smart, A. (2010). Tops and bottoms: State tolerance of illegal housing in Hong Kong and Calgary. Habitat International, 34(4), 478–484. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2010.02.004

- Troy, L., Van den Nouwelant, R., & Randolf. (2018a). State Environmental Planning Policy (Affordable Rental Housing) 2009 and affordable housing in Central and Southern Sydney. City Futures.

- Troy, L., Van den Nouwelant, R., & Randolph. (2018b). State Environmental Planning Policy (Affordable Rental Housing) 2009 and affordable housing in Central and Southern Sydney. City Futures and SSROC.

- Wegmann, J. (2015). Research notes: The hidden cityscapes of informal housing in suburban Los Angeles and the paradox of horizontal density. Buildings & Landscapes-Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum, 22, 89–110.

- Wegmann, J., & Chapple, K. (2014). Hidden density in single-family neighborhoods: Backyard cottages as an equitable smart growth strategy. Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability, 7(3), 307–329. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17549175.2013.879453

- Wegmann, J., & Mawhorter, S. (2017). Measuring informal housing production in California cities. Journal of the American Planning Association, 83(2), 119–130. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2017.1288162

- Wetzstein, S. (2019). Assessing post-GFC housing affordability interventions: a qualitative exploration across five international cities. International Journal of Housing Policy, 1–33.

- Yates, J. (2016). Why does Australia have an affordable housing problem and what can be done About It?. Australian Economic Review, 49(3), 328–339. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8462.12174