Abstract

Ensuring housing affordability while controlling government expenditure is a concern in many countries. In the UK support for private renters is delivered via an income-related housing benefit calculated using the Local Housing Allowance. As part of a programme to reduce government spending the support provided by the Local Housing Allowance was significantly reduced in 2011, and ongoing changes to its uprating have further reduced its value. These changes have raised concerns about the suitability of homes people receiving the allowance can afford. Using a natural experiment approach by applying matching and difference-in-difference methods to housing stock data from the English Housing Survey, this research finds a statistically significant 5% increase in overcrowding for housing benefit recipients following the changes to the Local Housing Allowance, equivalent to approximately 75,000 additional households living in overcrowded conditions. Longer-term results show that overcrowding continued to increase as changes to the uprating system further reduced the value of housing benefit. The decision to reduce the Local Housing Allowance and sever its relationship with actual rents has therefore reduced the ability of recipients to access suitable housing which will have had important implications for health and well-being, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Introduction

The Private Rented Sector (PRS) in England has expanded significantly in recent decades. Previously considered a transitory tenure primarily for students and young adults, it is now home to a greater number and type of households, as well as housing people for longer periods of time (Hoolachan et al., Citation2017). The PRS now houses nearly one-fifth of English households, double the proportion it housed in 1991 (MHCLG, Citation2020a, Citation2020b). Rather than reflecting increased popularity of private renting, the expansion of the PRS is due to the growing difficulty in accessing owner-occupation or social housing, particularly affecting young people from lower income backgrounds (Bailey, Citation2020; McKee et al., Citation2017). There are concerns about the suitability of the PRS to this expanded role, and the consequences for ‘Generation Rent’: young people who are having to spend long periods of their lives in the PRS or parental/family home with consequences for transitions to adulthood, particularly their ability to ‘settle-down’ and make a home (Hoolachan et al., Citation2017). Concerns about the increase in the PRS and Generation Rent are by no means unique to England or the UK, they can be found in many ‘homeowner societies’ with highly financialised housing systems (Byrne, Citation2020).

One of the consequences of the expansion of the PRS has been an upsurge in government spending on housing benefit (HB), an income-related housing allowance which acts as a demand-side intervention to support renters (Griggs & Kemp, Citation2012). HB spending rose by 50% in real terms between 1999/2000 and 2010/11 (Hodkinson & Robbins, Citation2013), peaking at £24.3 billion in the UK in 2014/15 (up from £5.1 billion in 1990/91, DWP, Citation2020). Successive governments have attempted to reduce HB expenditure. The Local Housing Allowance (LHA) approach to calculating HB entitlement was introduced in April 2008 by the Labour government, set at the median rent in the Broad Rental Market Area (BRMA) in which the household lives. BRMAs are large geographic areas which include a range of housing types and are typically within reach of many important services (although they are not required to be in reach of employment opportunities). They do not correspond with other administrative areas, such as Local Authorities, but are roughly similar in size to counties.

Following the 2010 election the Conservative-Liberal Democrat Coalition government sought to further reduce HB spending, and tackle the ‘problem’ (Jacobs et al., Citation2003), as framed by Iain Duncan-Smith, of people receiving HB living in homes that would be beyond the means of other households (Hansard, Citation2010; Hodkinson & Robbins, Citation2013; Kleynhans & Weekes, Citation2019). From April 2011 LHA rates were reduced to the 30th percentile of rents in each BRMA, rather than the median (50th percentile), and absolute caps were placed on rates depending on property sizeFootnote1. These rates applied from April 2011 for new claimants and from nine months after the anniversary of their claim for existing recipients. In addition, the five-bedroom rate was removed, as was the up to £15 weekly housing benefit excess. The Shared Accommodation Rate was also extended to most PRS renters under the age of 35.

These changes raised concerns about housing affordability for private renters (e.g., Fenton, Citation2010), but the government argued that the changes would instead place downward pressure on rents that landlords were charging. A review of the changes however found that 89% of the effects of the reduction was absorbed by tenants who had to find money for their housing costs elsewhere, and just 11% of the effects fell on landlords via reducing rents (Beatty et al., Citation2014).

Exacerbating concerns about the lowering of the LHA rate, successive Coalition and Conservative governments have changed the uprating system for LHA. Previously uprated monthly according to rental prices, from April 2013 the uprating of LHA was made annual and capped at the Consumer Price Index, which does not include rental prices in its calculation. Annual increases were further restricted to 1% in 2014 and 2015 before being frozen for four years from 2016 (Chartered Institute of Housing, Citation2016). This led to significant disparity between LHA rates and rents, as, for example, rents increased by 2.5% in England in the year to September 2016, while the LHA increase was limited to 1% (Office for National Statistics, Citation2016). In 2019 it was found that the LHA no longer covers rents for a two-bedroom home at the 30th percentile in 97% of England, or the 10th percentile in 33% of England (Kleynhans & Weekes, Citation2019). There was strong feeling about the implications of this approach at the time, with one MP asking:

Is this thinly veiled social cleansing? I ask that because it can only lead to ghettoisation across the United Kingdom.

(Chris Stephens in Hansard, 23rd November 2015)

A further factor affecting housing affordability for LHA recipients is the benefit cap. Introduced in 2013, the benefit cap limits the amount a household can receive in government benefits per yearFootnote2. The high cost of housing means that for many households the LHA accounts for the greatest proportion of their benefit income, and as a result, housing payments are frequently reduced: 60,000 households had their LHA capped in February 2018 (DWP, Citation2018). The benefit cap also reduced the impact of government changes to LHA in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, when the government increased the LHA back to the 30th percentile of local rents, reversing the effects of years of uprating well below rent increases. Many were unable to feel the effects of this increase because of the benefit cap, which was not raised in response to this increase, and between February and May 2020 there was a near doubling of households who had their benefit income reduced by the cap, disproportionately affecting single-parent households (MHCLG, Citation2020c).

The changes to HB and the LHA have significantly reduced the homes affordable to HB recipients, while also making recipients less attractive tenants to landlords (particularly young people subject to the Shared Accommodation Rate (Pattison & Reeve, Citation2017)). This limited availability of homes, and the lack of negotiating power tenants have in terms of the rents that they pay (Kemp et al., Citation2014), in combination with a lack of minimum standards for homes in the PRS (the Homes (Fitness for Human Habitation) Act 2018 came into effect in March 2019), means that there are serious concerns about the suitability and quality of the properties available to HB tenants, and the compromises that they may be forced to make in order to afford rents.

Evidence from Shelter (Kleynhans & Weekes, Citation2019) and the Institute for Fiscal Studies (Brewer et al., Citation2014) indicates that one compromise households are making in order to deal with the low levels of LHA is in terms of the size of the property they live in, raising concerns about overcrowding. Historically, overcrowding has been a key concern in the study of housing. It has been linked with a number of important outcomes, including physical and mental health, family relationships, child development, educational attainment, and accidents in the home (Clair, Citation2019; Krieger & Higgins, Citation2002; Shaw, Citation2004; Solari & Mare, Citation2012). Given the range of ways overcrowding impacts people’s lives, it is unsurprising that it has been linked with so many problems including, importantly, the spread of communicable diseases.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, overcrowding is an even greater issue. Early analysis indicates that the level of overcrowding in an area is a potentially important predictor of COVID-19 infection rates (Haroon et al., Citation2020; Kenway & Holden, Citation2020). The close proximity of people in overcrowded homes will make self-isolating near to impossible, with intra-household spread likely playing an important role in the outbreak (Weinberg College, Citation2020). Overcrowding will also have important consequences for people’s experiences during the lockdown, brought in to try to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Being confined to an overcrowded home will be a much more challenging experience than being confined to a reasonably spacious one, not least because of overcrowding’s link to mental health problems such as anxiety and depression (Shaw, Citation2004).

Overcrowding is typically measured according to either floor space, number of rooms, or number of bedrooms relative to household composition. The Bedroom Standard, used as the indicator of overcrowding here as well as to decide LHA rates, requires one bedroom per:

couple

person aged 21 years or over

two persons of the same sex aged 10 years or over but under 21

two persons under the age of 10 years

two persons of the same sex where one person is aged between 10 years and 20 years and the other is aged less than 10 years

any additional person who cannot be paired with another occupier (Housing (Overcrowding) Bill)

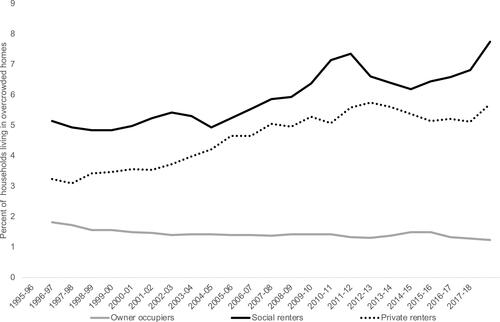

Overcrowding in the PRS in England has increased since the 1990s (). The PRS is the second-most overcrowded tenure, being slightly less overcrowded than the social rented sector, but considerably more crowded than the owner-occupied sector. This paper adds to the existing literature on overcrowded housing by exploring whether the reduction in the LHA increased overcrowding among recipients using matching and difference-in-differences approaches to isolate the effect of the policy change.

Methods

This research uses data from the English Housing Survey (EHS) (MHCLG, Citation2008–2019). The EHS is a large survey of housing circumstances and conditions used in the production of national statistics that began in 2008. It initially included approximately 17,000 households for annual face-to-face interviews on housing circumstances, including HB receipt, and 8,000 dwellings every two years for a physical survey on conditions. A cost review in 2011/12 reduced these samples sizes to 13,000 and 6,200 respectively.

The survey uses the Royal Mail Postal Address File to select the sample, with survey years matching financial years (i.e., running April-March). The survey sample was originally unclustered but was later semi-clustered to reduce costs. One dwelling per address, and one household per dwelling is sampled. The collection of the EHS data is unrelated to the policy change of interest in this study – homes and households are not selected on the basis of HB receipt.

The smaller sample size for the dwelling survey means that it is necessary to combine 2 years of data to create a dataset large enough for analysis, meaning that results for only even or odd years may be presented (see the EHS Housing Stock Dataset User Guides for details). However, the April to March scheduling of the data collection means that the 2010 and 2012 survey data accurately reflects before and after periods of the intervention in LHA rates (details in ). The stratified sampling of the dwelling survey makes weighting the data necessary. Grossing weights designed to produce nationally representative estimates are included in the data. The sample used here is limited to occupied, privately rented homes, summarised in .

Table 1. English Housing Survey details.

The EHS dwelling survey includes a range of information on housing conditions. This analysis focuses on whether the home is overcrowded (according to the bedroom standard), with the variable binary coded so that 1 indicates overcrowding.

Difference-in-difference methods enable causal analysis of an intervention by mimicking experimental research design, accounting for pre-existing differences between the treatment (HB recipients in the private rented sector) and control (private renters who do not receive HB) groups, as well as for time trends, thus adjusting for selection effects that may affect the likelihood of receiving HB. This approach has been used successfully to explore causal impacts of LHA changes with repeated cross-sectional data previously (Reeves et al., Citation2016).

The analysis approach here consists of two stages. The first uses a strict difference-in-differences approach limiting the data to that collected immediately prior to and after the policy change. It compares the change in overcrowding between private renters in receipt of HB and private renters not in receipt of HB immediately following the change to the LHA in 2011, matching individuals on characteristics that are associated with their likelihood of receiving HB, reducing confounding effects. The analysis is conducted using the diff command (Villa, Citation2016) in Stata 14. Kernel propensity score matching is used, and analysis limited to cases with common support.

The second stage of analysis uses a difference-in-differences model with a regression framework for all years of data given in , controlling for individual characteristics, and reported with robust standard errors. This approach will shed light on the longer-term effects of the change in HB and LHA policy including reductions in the uprating of the value of the benefit.

The variables used for matching in step one and as controls in step 2 are: dependent child(ren) in household, more than one adult in household, oldest person in the household is aged over 60 years, workless household, ethnicity (white, ethnic minorityFootnote3), sex of household reference person, whether anyone in household has a long-term illness, whether household reference person or partner is registered disabled, log household income, and whether in London. These variables were selected as they are associated with risk of living in an overcrowded home and/or receiving HB (MHCLG, Citation2018a). Further details are given in Appendix .

Results

Initial exploration of overcrowding levels shows a slight decrease in overcrowding overall during the period of EHS data collection. When explored in terms of HB receipt, those receiving HB saw a sharp increase in overcrowding in the survey year after the LHA change, a trend which continued into 2016 (), while overcrowding decreased for those not in receipt of HB.

Table 2. Percentage living in overcrowded homes.

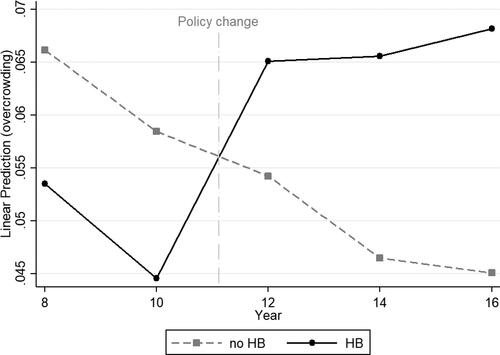

This is further explored using difference-in-differences analysis to investigate the role of the policy change in this increase in overcrowding, initially focusing on data years 2010 and 2012 (). The appendices include details about the sample and its suitability for difference-in-differences methods. Model 1 shows the results of the analysis with no matching. It shows no meaningful change in overcrowding in the period following the change in the LHA or statistically significant difference in levels of overcrowding between HB recipients and non-recipients. After matching survey respondents on important characteristics linked with HB receipt in Model 2, the coefficient for change over time becomes negative, as does the coefficient for HB receipt. Although not statistically significant, the coefficient indicates lower levels of overcrowding among HB recipients before the policy change when adjusting for individual and household characteristics. However, the difference-in-differences coefficient is statistically significant, indicating an increase in overcrowding of more than 5 per cent among HB recipients after the reduction in the LHA. In April 2011 there were over 1.5 million households in the private rented sector who received HB (MHCLG, Citation2018b). A 5 percent increase therefore equates to approximately 75,000 additional households living in overcrowded conditions.

Table 3. Difference-in-difference model showing changes in overcrowding between HB recipients and other private renters, 2010 and 2012 data.

The next stage of the analysis uses a regression approach to difference-in-differences analysis of all waves of the EHS to explore the longer-term effects of the LHA reduction and changes to its uprating. shows that overcrowding decreased in general after the change in LHA rate, and that, controlling for demographic factors, receipt of housing benefit reduced the likelihood of overcrowding prior to the policy change. However, the significant difference-in-difference coefficient indicates that the 2011 reduction in LHA rates and ongoing changes in uprating resulted in higher levels of overcrowding among HB recipients. shows these results graphically. Before 2011, overcrowding rates were decreasing for both recipients and non-recipients of HB. This trend continued after the policy change for non-recipients, but for those using HB to help meet their housing costs the change led to a dramatic increase in overcrowding. The trend for HB recipients continued upwards, in contrast to the continued downward trend for other private renters.

Table 4. Difference-in-difference model showing changes in overcrowding between HB recipients and other private renters, regression approach, 2008-2016 data.

Discussion

The analysis presented here demonstrates that the decision to reduce the amount of rent that the LHA would cover resulted in a statistically significant increase in overcrowding of 5% (equivalent to 75,000 households) for recipients, exacerbating inequalities in housing. The changes to uprating, which meant that LHA rates no longer tracked with changes in rents, further exacerbated this effect. This will have had significant consequences for the health and well-being of these households.

Even before the COVID-19 pandemic overcrowded housing was detrimental to health. In the context of the pandemic, which has highlighted the important role of housing in health internationally, and in which overcrowding has been linked with higher levels of infection (Barker, Citation2020; Brent Poverty Commission, Citation2020), these findings implicate housing policy in the spread of COVID-19 in England. Renters in England have also suffered from a relative lack of housing support during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in contrast to the support available for mortgagors. This has left people highly vulnerable to housing problems, with potential long-term repercussions for housing and health.

As with finding that the reduction in the LHA had led to an increase in depression (Reeves et al., Citation2016) and other consequences (O’Leary & Simcock, Citation2020), the findings here demonstrate the counter-productive consequences of a policy ostensibly motivated, at least in part, by reducing spending. While spending on individual household LHA was reduced, increased costs due to the health and other impacts will have undermined savings. These findings should serve as a warning to other nations who may be tempted to reduce support for renters as a means of reducing spending. It is important to note that these changes to the LHA also had the effect of reducing the number of LHA claimants, so this analysis likely underestimates the impact of the policy changes and misses a number of people living in poor housing without additional HB support.

The effects of these policy changes will not have been felt equally. They will have disproportionately affected single-parent families, households with dependent children, households that include a disabled person or people, women-headed households, racially marginalised households (who will also have to deal with racism when renting (Lynn & Davey, Citation2013) and experience persistent disadvantage in the housing market (Gulliver, Citation2016)), and households headed by people under the age of 35, as it is these households that are more likely to be in receipt of HB.

In the English context, these findings support calls to increase the LHA back to the 50th percentileFootnote4, and to uprate in line with rents. While this is in conflict with the apparent desire among policy makers to reduce government spending, three considerations should be acknowledged. Firstly, it should be recognised that the increase in HB spend over time reflects decisions by policy makers, such as the shrinking of the social rented sector, that have led to the increase in people living in the PRS and increasing rents, rather than the excessive spending of HB recipients (Powell, Citation2015). Secondly, many interventions made on the basis of ‘improving’ access to owner occupation have, at great cost, inflated housing prices and made accessing ownership more difficult for renters (e.g., Shelter, Citation2015) benefitting large housebuilders (Jolly, Citation2019) and those already in owner-occupation (Birch, Citation2021; Chapman, Citation2021). Given these impacts, perhaps policy makers should look beyond support for renters to interventions in the owner-occupied market for housing spending reductions. Finally, reducing spending on HB will likely have led to increases in spending elsewhere, particularly health, because of the negative consequences including overcrowding.

Making housing more affordable through LHA will have benefits in the short-term, enabling recipients to access more appropriate housing and reducing the health and social consequences associated with overcrowding, while moving towards a more sustainable housing policy should be a longer-term goal. In the broader context, these findings add to the extensive evidence of the centrality of housing and housing policy to people’s well-being and should also serve as a warning to governments looking to cut spending by reducing housing support.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Professor Paul Clarke for his feedback on the methods used in this paper and to the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Data availability

The data used in this research are available to researchers through the UK Data Service at beta.ukdataservice.ac.uk/datacatalogue/series/series?id = 200010.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 £250 per week for a one-bedroom property; £290 for a two-bedroom property; £340 for a three-bedroom property; £400 for a four-bedroom property

2 The benefit cap was originally set at £26,000 per year (£18,200 for a single person), before being reduced to £23,000 for a household in London (£15,410 for a single person) or £20,000 for a household outside of London (£13,400 for a single person) from November 2016.

3 The crude ethnicity categories are unfortunately necessary due to sample size.

References

- Bailey, N. (2020). Poverty and the re-growth of private renting in the UK, 1994-2018. PLoS One, 15(2), e0228273. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0228273

- Barker, N. (2020). The housing pandemic: four graphs showing the link between COVID-19 deaths and the housing crisis. https://www.insidehousing.co.uk/insight/insight/the-housing-pandemic-four-graphs-showing-the-link-between-covid-19-deaths-and-the-housing-crisis-66562

- Beatty, C., Cole, I., Powell, R., Kemp, P., Brewer, M., Emmerson, C., Hood, A., & Joyce, R. (2014). Monitoring the impact of changes to the Local Housing Allowance system of Housing Benefit: final reports. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/445618/rr871-lha-econometric-analysis-of-the-impacts-of-reforms-on-existing-claimants.pdf

- Birch, J. (2021). The government’s housing market interventions have done little to benefit first-time buyers. Inside Housing. https://www.insidehousing.co.uk/comment/the-governments-housing-market-interventions-have-done-little-to-benefit-first-time-buyers-70437

- Brent Poverty Commission. (2020). A fairer future: Ending poverty in Brent. https://www.brent.gov.uk/media/16416717/poverty-commission-report-launched-17-august-2020.pdf

- Brewer, M., Emmerson, C., Hood, A., & Joyce, R. (2014). Econometric analysis of the impacts of Local Housing Allowance reforms on existing claimants. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/445618/rr871-lha-econometric-analysis-of-the-impacts-of-reforms-on-existing-claimants.pdf

- Byrne, M. (2020). Generation rent and the financialization of housing: A comparative exploration of the growth of the private rental sector in Ireland, the UK and Spain. Housing Studies, 35(4), 743–776. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1632813

- Chapman, B. (2021). UK house prices surge £20,000 in a year, fuelled by low mortgage rates and stamp duty holiday. Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/business/house-prices-uk-average-property-mortgage-b1835117.html

- Chartered Institute of Housing. (2016). Mind the Gap: The Growing Shortfall between Private Rents and Help with Housing Costs. Chartered Institute of Housing.

- Clair, A. (2019). Housing: An under-explored influence on children’s well-being and becoming. Child Indicators Research, 12(2), 609–626. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-018-9550-7

- Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). (2018) Benefit Cap Data to February 2018. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/704234/benefit-cap-statistics-feb-2018.pdf

- Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). (2020). Outturn and forecast: Spring Budget 2020 (ODS). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/884066/outturn-and-forecast-spring-statement-2020.ods

- Fenton, A. (2010). How will changes to Local Housing Allowance affect low-income tenants in private rented housing?. Cambridge Centre for Housing & Planning Research.

- Griggs, J., & Kemp, P. (2012). Housing allowances as income support: Comparing European welfare regimes. International Journal of Housing Policy, 12(4), 391–412. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2012.711987

- Gulliver, K. (2016). Forty Years of Struggle: A Window on Race and Housing, Disadvantage and Exclusion. Human City Institute.

- Hansard. (2010). Capital Gains Tax (Rates) 28 June 2010. Volume 512. https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2010-06-28/debates/10062812000003/CapitalGainsTax(Rates)

- Hansard. (2015). Rent Officers (Housing Benefit and Universal Credit Functions) (Local Housing Allowance Amendments) Order 2015. https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2015-11-23/debates/0eac0a7b-0df4-4f1f-b0c2-fe9b5aa02d1c/RentOfficers(HousingBenefitAndUniversalCreditFunctions)(LocalHousingAllowanceAmendments)Order2015

- Haroon, S., Singh Chandan, J., Middleton, J., & Keung Cheng, K. (2020). Covid-19: Breaking the chain of household transmission. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 370, m3181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3181

- Hodkinson, S., & Robbins, G. (2013). The return of class war conservatism? Housing under the UK Coalition Government. Critical Social Policy, 33(1), 57–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018312457871

- Hoolachan, J., McKee, K., Moore, T., & Soaita, A. M. (2017). Generation rent’ and the ability to ‘settle down’: Economic and geographical variation in young people’s housing transitions. Journal of Youth Studies, 20(1), 63–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2016.1184241

- Jacobs, K., Kemeny, J., & Manzi, T. (2003). Power, discursive space and institutional practices in the construction of housing problems. Housing Studies, 18(4), 429–446. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030304252

- Jolly, J. (2019). Help-to-buy scheme pushes housebuilder dividends to £2.3bn. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/mar/01/help-to-buy-pushes-uk-housebuilder-dividends-to-23bn

- Kemp, P., Cole, I., Beatty, C., & Foden, M. (2014). The impact of changes to the Local Housing Allowance in the private rented sector: The response of tenants. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/380461/rr872-nov-14.pdf

- Kenway, P., & Holden, J. (2020). Accounting for the Variation in the Confirmed Covid-19 Caseload across England: An analysis of the role of multi-generation households. NPI.

- Kleynhans, S., & Weekes, T. (2019). From the frontline: Universal Credit and the broken housing safety net. Shelter.

- Krieger, J., & Higgins, D. (2002). Housing and health: Time again for public health action. American Journal of Public Health, 92(5), 758–768. Vol https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.92.5.758

- Lynn, G., & Davey, E. (2013). London letting agents ‘refuse black tenants’. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-24372509

- McKee, K., Moore, T., Soaita, A., & Crawford, J. (2017). ‘Generation Rent’ and the fallacy of choice. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(2), 318–333. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12445

- Ministry for Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG). (2008–2019). English Housing Survey 2008-, Housing Stock Data. beta.ukdataservice.ac.uk/datacatalogue/series/series?id=200010

- Ministry for Housing Communities and Local Government (MHCLG). (2018a). English Housing Survey: Variations in housing circumstances, 2016–17. MHCLG.

- Ministry for Housing Communities and Local Government (MHCLG). (2018b). Housing Benefit caseload statistics: data to May 2018. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/812611/housing-benefit-caseload-data-to-may-2018.ods

- Ministry for Housing Communities and Local Government (MHCLG). (2020a). English Housing Survey: Headline Report, 2019–20. MHCLG.

- Ministry for Housing Communities and Local Government (MHCLG). (2020b). Table 104: by tenure, England (historical series). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/886264/LT_104.xls

- Ministry for Housing Communities and Local Government (MHCLG). (2020c). Benefit cap quarterly statistics: GB households capped to May 2020. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/906680/benefit-cap-statistics-May-2020-tables.ods

- Ministry for Housing Communities and Local Government (MHCLG). (n.d.) FT1421: trends in overcrowding by tenure. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/817039/FT1421_Trends_in_overcrowding_by_tenure.xlsx

- O’Leary, C., & Simcock, T. (2020). Policy failure or f***up: homelessness and welfare reform in England. Housing Studies. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1849573

- Office for National Statistics. (2016). Index of Private Housing Rental Prices (IPHRP) in Great Britain: Sept 2016. https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/bulletins/indexofprivatehousingrentalprices/sept2016

- Pattison, B., & Reeve, K. (2017). Access to Homes for Under-35's: The impact of Welfare Reform on Private Renting. Sheffield Hallam University.

- Powell, R. (2015). Housing benefit reform and the private rented sector in the UK: On the deleterious effects of short-term, ideological “Knowledge”. Housing, Theory and Society, 32(3), 320–345.

- Reeves, A., Clair, A., McKee, M., & Stuckler, D. (2016). Reductions in the United Kingdom's Government Housing Benefit and Symptoms of Depression in Low-Income Households. American Journal of Epidemiology, 184(6), 421–429. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kww055

- Shaw, M. (2004). Housing and public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 25, 397–418. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123036

- Shelter. (2015). How much help is Help to Buy? Help to Buy and the impact on house prices. Shelter.

- Solari, C. D., & Mare, R. D. (2012). Housing crowding effects on children’s wellbeing. Social Science Research, 41(2), 464–476. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.09.012

- Villa, J. M. (2016). diff: Simplifying the estimation of difference-in-differences treatment effects. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 16(1), 52–71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X1601600108

- Weinberg College. (2020). Perspectives on the pandemic. https://www.pandemic.weinberg.northwestern.edu/2020/06/19/living-with-a-covid-19-patient-you-probably-have-antibodies/

Appendix

Table A1. Sample descriptives (percent).

Table A2. Weighted comparisons of control variables before and after policy change, 2010-2012 data.

Table A3. Differences in control/matching variables between those in receipt of housing benefit and those not in receipt, before and after matching (weighted).

Table A4. Full results for model shown in .