Abstract

Global rates of excess mortality attributable to the Covid-19 pandemic provide a fresh impetus to make sense of the associations between income inequality, housing inequality and the social gradient in health, suggesting new questions about the ways in which housing and health are treated in the framing and development of public policy. The first half of the paper uses a social harm lens to examine the threefold associations of the social inequality, housing and health trifecta and offers new insights for policy analysis which foregrounds the production, transmission, and experience of various types of harm which occur within the home. The main body of the paper then draws upon the outcomes of an international systematic literature mapping review of 213 Covid-19 research papers to demonstrate three specific harms associated with stay-at-home lockdowns: (i) intimate partner and domestic violence, (ii) poor mental health and (iii) health harming behaviours. The reported findings are interpreted using a social harm perspective and some implications for policy analysis are illustrated. The paper concludes with a reflection on the efficacy of social harm as a lens for policy analysis and suggests directions for further research in housing studies and zemiology.

Introduction

Housing policy has a pivotal role to play in responding to the Covid-19 public health crisis and its aftermath (Rogers & Power, Citation2020, p. 177). There is considerable evidence to demonstrate that the pandemic impoverishes unequally, and that excess mortality is associated with housing inequality and disadvantage (Ahmad et al., Citation2020; Bambra et al., Citation2020, Citation2021; Hu et al., Citation2021). Discussions which make the case for post-pandemic housing policies which foreground social justice to build back better or build back fairer are underway in many countries (Brown et al., Citation2020; Horne et al., Citation2020; Kearns, Citation2020; Marmot et al., Citation2020; Moreira & Hick, Citation2021; Power et al., Citation2020; Tinson & Clair, Citation2020). For a generation of housing scholars then, the relationship between housing, health and social inequality has never been quite so important nor so visible.

Against this backdrop, this paper takes stock of our understandings of the relationship between housing, health and social inequality. The precise nature of the causation implied in this three-way relationship, or ‘trifecta’ has seldom been subject to serious sustained scrutiny (although see Angel & Bittschi, Citation2019; Rolfe at al., 2020). That there is a social gradient in health, and that housing is one of the social determinants of health inequality is as much a taken for granted cornerstone of housing research as is the idea that home is more than bricks and mortar.

This paper makes a modest contribution to discussions in this area. It does so by focusing upon housing and in particular, home, as a locus of social harm during the Covid-19 pandemic. It suggests new ways of thinking and talking about the three-way relationship between housing, health and social inequality and demonstrates some possibilities which the social harm lens might offer for housing policy analysis. It is organised in four remaining sections. First, it outlines the contours of the social inequality, housing and health trifecta and suggests a new interpretation based upon the identification of harms. Next, the paper introduces a harm-from-home perspective to argue that home is a crucial locus in a putative geography of harm. This section goes on to outline the social harm approach as it has developed within critical criminology and zemiology. The next part of the paper presents a systematic literature mapping exercise which reduces more than 5,000 research papers published on the subject of Covid-19, housing, harm and stay-at-home lockdowns down to 213 papers included in an analysis which demonstrates the extent of three types of social harm which occurred during the pandemic. Next, the paper offers some speculative remarks on how harm reduction and the regulation of harm might be incorporated into housing policy discourses. The paper concludes with some suggestions for further work in this area. The titular dangerous liaisons of this paper refer to the act of foregrounding dangerous harms in studying housing and Covid-19 but also of the potentially disruptive effects of privileging structural accounts of social harms in housing policy analysis and of thinking anew about the causal relationships between social inequality, health inequality and housing.

Housing, health and social inequality

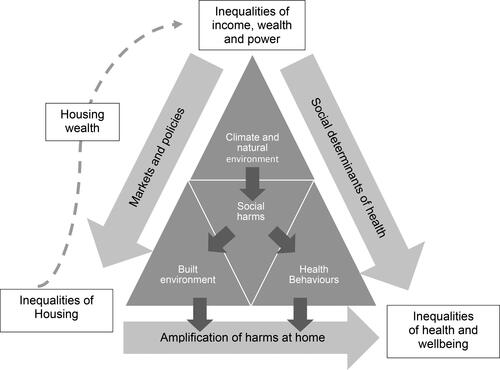

The three way relationship between social inequality, housing and health is a complex and recursive trifecta. Demonstrating the nature of causation between the three points—rather than merely identifying an association between them—and distilling the role of housing from other social determinants of health presents a significant and ongoing challenge (Rolfe et al., Citation2020) for housing policy research (see ). This is not a new challenge. Indeed, the relationship between housing and health has been of interest to researchers and reformers for more than 200 years (see, for example, Chadwick, Citation1842; Graham, Citation1818). Much useful contemporary knowledge exchange is hampered by the separation, rather than the integration of distinctive housing research and health research outputs with the consequence that few scholars find their work is cited by both sides of an epistemological schism. Thus, Lawrence (Citation2017) bemoans the low scientific impact of papers addressing the relationships between housing and health published since the 1980s and urges a consolidation of the cumulative outcomes of such work with respect to policy formulation, whilst Angel and Bittschi (Citation2019) lament a bifurcated citation network which too often fails to integrate neighbourhood effects and dwelling effects in work on housing and health.

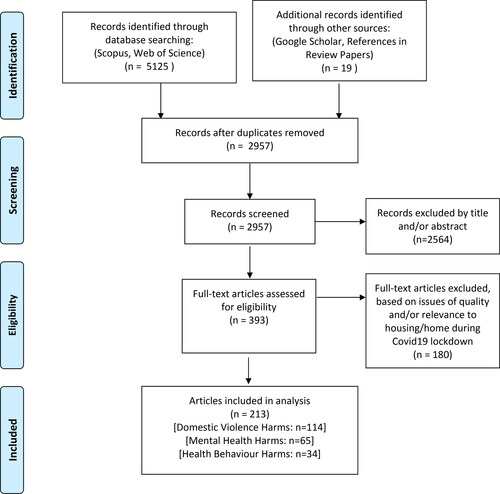

Figure 2. PRISMA flow diagram (Page et al., Citation2021).

Housing is universally recognised as one of the key social determinants of health inequality (World Health Organization, Citation2019). Whilst it has been relatively easy to establish direct causal relationships between what Shaw (Citation2004, p. 398) calls the ‘hard, physical and material’ aspects of housing quality (such as damp, mould, and cold) with health outcomes such as respiratory diseases, the more indirect and less tangible connections to the ‘soft, social and meaningful’ influences upon health and well-being outcomes remain notoriously difficult to identify (Blakely et al., Citation2011; Rolfe et al., Citation2020). Those less tangible connections are returned to later in this paper.

The idea that housing has a number of attributes or bundles which correspond to the hard, physical, material as well as the soft, social and meaningful qualities described above by Shaw (Citation2004), and which are evident in direct and indirect causation of health and well-being outcomes, has been a fruitful area of research. For example, Baker and her co-authors (2017, Citation2019) refer to it as the ‘housing bundles’ perspective. In a little less than a single page of their paper, Baker et al. (Citation2017, pp. 3–4) review 34 research studies to demonstrate the abstracted out, direct and indirect effects of the ‘bundles’ of housing conditions, housing quality, tenure, affordability and location upon health and well-being outcomes. In an argument reminiscent of the ‘causes of the causes’ work by Braveman and Gottlieb (Citation2014) (which demonstrates the cumulative effects of inequalities in access to education which, in turn, generate complex pathways and mechanisms by which health inequality is transmitted), Baker et al. (Citation2017) develop a ‘housing insults to health index’ which they use to demonstrate how accumulations of housing inequalities associated with affordability, security, quality of dwelling, quality of neighbourhood and access to services and support exhibit a social gradient and are mutually reinforcing. There is still much work to be done in explaining how housing ‘works’ to store, mediate, amplify or transmit social inequality such that health inequalities subsequently occur. Thus, housing still presents itself as a ‘black box’ wherein social inequality is an input and health inequality is an output. Baker et al. (Citation2017, p. 12) for instance were not able to ‘determine whether poor quality housing results in poorer health or whether lower-income persons with poorer health are simply forced by market processes into “health-risky” dwellings’. Similarly, whilst Rolfe et al. (Citation2020) were able to demonstrate that tenants’ experience of property quality and aspects of neighbourhood quality were strongly correlated with health and wellbeing outcomes they were quick to remind us that correlation is not causation and that more work is needed to develop their realist pathways approach in order to clearly specify the mechanisms by which well-being or poor health is generated.

In seeking to explain the multiple, complex, and multi-directional causations in the social inequality, housing and health trifecta, it seems that significant elements of the ‘pathways’ or ‘mechanisms’ which produce health inequalities remain hidden. The diagram in is an attempt to conceptualise what we know alongside a suggested social harm lens which is developed in the remainder of this paper. The diagram is a visual representation of a proposition that the trifecta is the outcome of the ongoing production, transmission and accumulation of numerous social harms which are uniquely experienced in our homes or in housing situations (such as homelessness). We can begin reading the diagram at the top of the triangle where inequalities of income, wealth and power generate the social determinants of health and, through the operation of markets and policies, create demonstrable housing inequalities (note here the inclusion of housing wealth as a recursive element in the model which perpetuates further inequalities). Inside the body of the triangle, we see that aspects of climate and the natural environment, the built environment and health behaviour are all contexts within which various social harms emerge. Such harms, this paper argues, are most frequently triggered, occur and are experienced in the home, and home should therefore be understood as a key locus in a geography of harm. The bottom side of the triangle represents the amplification of pre-existing health inequalities manifested as harms experienced at home. The processes implied in the three-way relationship conclude with the addition of the health and well-being outcomes of harms at home to those health inequalities generated by the non-housing social determinants of health at the bottom right hand corner. Whilst this diagram may not fully illuminate the black box of housing in relation to health outcomes, it does have the potential to change the conversation about housing and health and suggests new tactics and opportunities for mainstreaming health on the housing policy agenda and vice-versa. It also poses a potentially destabilising set of questions about the psycho-social benefits of home. The next section of the paper takes up this point. Rather than being vague or difficult to operationalise (as suggested by, for instance, Rolfe et al., Citation2020 and Shaw, Citation2004), the paper contends that the endless pursuit of the supposed psycho-social benefits of home in research which looks for ontological security is predicated on a taken-for-granted and often illusory set of attributes which have been overstated and, far from being a space of nourishing and flourishing, that home also has a conceptually under-developed dark-side of unheimlich qualities (McCarthy, Citation2018) which stores, sorts and dispenses harm.

Social harm and harm-from-home: a turn to violence in housing and health research?

The social harm perspective (Canning & Tombs, Citation2021; Hillyard et al., Citation2004; Hillyard & Tombs, Citation2007; Lloyd, Citation2019; Pemberton, Citation2015; Tombs, Citation2020) has transformed the ways in which criminologists have looked beyond ideas of crime to examine ‘non-criminal’ harms and, in particular, consider how states and large multinational corporations perpetrate various forms of harm in societies. A commonly cited definition of social harm is this:

The deleterious activities of local and national states and of corporations upon peoples’ lives whether in respect to a lack of wholesome food, inadequate housing, or heating, low-income, exposure to various forms of danger, violations of basic human rights and victimisation to various forms of crime. (Hillyard et al., Citation2004, p. 18)

Whilst at home, we may fall ill; fall off a ladder; fall downstairs; fall behind with rental or mortgage repayments; be evicted; experience isolation, loneliness, anxiety and work-related stress (whilst working from home); recklessly and harmfully consume alcohol, or other drugs and eat junk food to excess; make suicidal ideation or actions; be exposed to damp, mould, cold, polluted, over-crowded, noisy dwellings; be the victim of coercive control, physical, psychological or sexual violence by an intimate partner or family member; be asphyxiated and die in a fire or an escape of carbon monoxide. Most of these events are not crimes, but they can all still be thought of as social harms. In other words, they are far from benign accidents or the result of individual choices, but instead have a social gradient such that their incidence is contingent upon the social structure and its organisation. These incidents do not occur in random patterns; thus, rates of domestic violence, alcohol consumption and evictions vary according to prevailing social and economic conditions by country and by region (Pemberton, Citation2015). Similarly, some of these events might appear to have little to do with housing policy yet they do occur at home and, in the case of fire safety, building regulations, and housing conditions, are evidence of failures in policy and/or regulation. The place where social harms occur is significant, and many more harms than we might care to imagine occur in private, in back regions, behind closed doors, away from public scrutiny where we can ‘be ourselves’. Privacy is a highly cherished attribute of home, but we should not lose sight of the fact that being free from surveillance, public opprobrium and support networks enables social harms to occur undetected and unmediated.

There is a well-established academic literature on the psycho-social benefits of home, and in particular the role of the (owner occupied) home in sustaining a sense of ontological security, stability, and autonomy (Gurney, Citation1990; Hiscock et al., Citation2001; Kearns et al., Citation2000; Saunders, Citation1990). Notwithstanding much feminist scholarship which suggests home may also be a place of confinement, vulnerability, and danger (Madigan et al., Citation1990; Watson & Austerberry, Citation1986; Zufferey et al., Citation2016), the most striking feature of the meaning of home literature since the 1980s is the relentless identification of attributes of home which are cherished, celebrated, and afforded protective rights (of quiet enjoyment, for example).

I want to suggest that the positive psycho-social benefits of home have been consistently overstated and there is a Freudian unheimlich quality (McCarthy, Citation2018) or ‘dark-side’ of home, located in undiscovered conceptual spaces which have been neglected in favour of mapping and celebrating the positive attributes of home. Of course, home might still be a haven for many, but we should not assume that the supposed positive attributes of home will remedy pre-existing poor mental health, that dwellings which pose safety hazards will not cause anxiety and eventually injury, nor that home is a safe place for people sharing a household with their abuser. Instead, home should be read as a key locus in a geography of harm. During Covid-19 ‘stay at home’ lockdowns for instance, the exposures to harms from home were significant. Pemberton’s book Harmful Societies (2015) demonstrates social harm, like health inequality, is far from randomly distributed. In fact, a social gradient in harm can be seen between and within countries operating under different welfare regimes. Thus, rates of obesity, death by suicide, homicide and road traffic accidents vary according to the extent to which, for example, neo-liberal or social democratic regimes of harm reduction and regulation are at play.

A focus on social harm implies an examination of the hidden and indirect consequences of state and corporate violence, neglect, indifference, and de-regulation (Pemberton, Citation2015; Tombs, Citation2020); of the steep social gradients in health opportunities and health outcomes (Bambra et al., Citation2020, Citation2021; Hu et al., Citation2021); and of the extent to which infrastructures of care (Power & Mee, Citation2020) might offer protections. That such changes in academic thinking should occur in the 2020s is neither a surprise nor a coincidence. What is surprising however, is that it took a global pandemic to make housing and health top billing. Thinking critically about why the Covid-19 pandemic had unequal impacts reveals the significance of social harm in making sense of the social inequality, housing and health trifecta.

A systematic literature mapping exercise

According to the Scopus bibliographical database, between January 1, 2020, and February 28, 2021, 104,207 papers were published on the subject of Covid-19 (this figure was 135,530 according to Web of Science). An additional 7,994 papers were added to Scopus between March 1 and March 15, 2021. This unprecedented output presents a significant challenge for researchers in any field trying to identify what is significant and, more importantly, what is not. It is not an exaggeration to claim that ‘never before in the history of academic publishing has such a great volume of research focused on a single topic’ (Odone et al., Citation2020, p. 34). The need to distil this huge volume of publications has generated several useful reviews on the deleterious consequences of lockdown measures for health (Kotlar et al., Citation2021 review a combined total of 273 published studies for instance; Moreira & Pinto da Costa, Citation2020; Public Health England, Citation2021; Rajkumar, Citation2020; Sánchez et al., Citation2020; Viero et al., Citation2021) and several notable comparative reviews of public policy responses to the pandemic (see, for example, Hastings et al., 2021; Moreira & Hick, Citation2021). The sheer volume of research has generated concerns about the robustness of refereeing and publication processes, (at the time of writing, Retraction Watch (2021) report almost 100 retracted or withdrawn Covid-19 papers) and of a general communication noise which may lead to important contributions being overlooked in favour of more ‘contrived’ or unreliable papers (Sorooshian & Kumar, Citation2020). There is therefore, a pressing need for reviews which can offer meaningful and reliable analyses of Covid-19 and its impacts.

One outcome of an increasingly neoliberal and marketised approach to higher education and research is the demand for academic researchers to demonstrate the impact of their research and to facilitate knowledge exchange and transfer. This has forced a reassessment of the role and purpose of the literature review in academic work such that approaches to engaging with extant work have inevitably changed to better meet end-users’ requirements. Whilst traditionalists might lament the diminution of the slow skills of ‘intellectual craftsmanship’ (Mills, Citation1959) necessary to critically engage with a literature and identify lacunae in favour of quasi-scientific review strategies which can more quickly reveal ‘what works’, the changed research environment cannot be ignored. Thus, Soaita et al. (Citation2020) demonstrate the demands of synthesising a large number of housing policy research items with limited resources to very tight deadlines. After a discussion on the benefits of different types of review they outline a methodology for the generation of a systematic literature mapping approach which offers a ‘systematic method for working through a large volume of peer reviewed scholarship in an attempt to link research evidence to evidence-based policy making’ (Power et al., Citation2020, p. 313). Sutton et al. (Citation2019) identify 48 different types of review with the traditional, or narrative literature review at one end and the scientific systematic review with published study protocol and double review at the other. This work occupies one of the spaces in between. By adopting the systematic literature mapping methodology advocated by Soaita et al. (Citation2020), this review may have less of the rigour and depth associated with a true systematic review but is still able to rapidly report on a wide range of research papers, making informed judgements about relevance and quality, identifying themes, trends, and gaps.

Searches were made on the title, abstract and keywords (Scopus) or topic (Web of Science) for ‘Covid(19)’ AND ‘housing’; ‘home’; ‘harm’; ‘violence’; ‘mental’ (for mental health mental distress etc.); ‘well-being’; ‘behaviour’ (for health-harming behaviours); ‘domestic violence’; ‘lockdown’; ‘home AND eat*’ and ‘home AND alcohol’. These keywords were informed by a harm-from-home framework suggested in an earlier paper published in April 2020 (Gurney, Citation2020). Whenever there was a significant numerical difference in searches on different databases the lower figure was included in a bid to reduce duplicates. A small number of other grey literature papers were then added from a linked Google Scholar search and from references to papers cited in those reviews which had already been read. This process yielded a combined set of 5,144 papers. After removing duplicates, 2,957 papers were then further reduced via a manual check of each title. Titles which appeared, to this author, of no relevance to the investigation were excluded. The resulting set of 393 papers was then checked for inclusion in the analysis. The author read the title, abstract and/or first few lines of each of these 393 papers and included them in the analysis if they reported home-based harms, engaged with housing design, quality, or policy, and were confined to periods of Covid-19 related lockdowns during 2020–2021. The author read the resulting list of 213 papers in full. The author undertook this analysis alongside their role as a full-time academic with a full teaching load and administrative responsibilities during January-March 2021. This is significant as gold standard systematic reviews usually require a dedicated team of experts to moderate data reduction reviews and would certainly allow a much longer period of time in order to complete the task. In this respect, the review was once more influenced by the methodological discussions advanced by Soaita et al. (Citation2020) who argue that quality need not necessarily be sacrificed for expeditiousness in rapid evidence reviews. That said, the limitations of a rapidly completed, single reviewer study of 200+ papers should not be discounted. The author’s own affect, emotion and biography are significant in accounting for this final figure and another researcher may have found it easier to discard ‘marginal’ papers given the subjects covered in this review. The review process is described in the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram (Moher et al., Citation2009) below ().

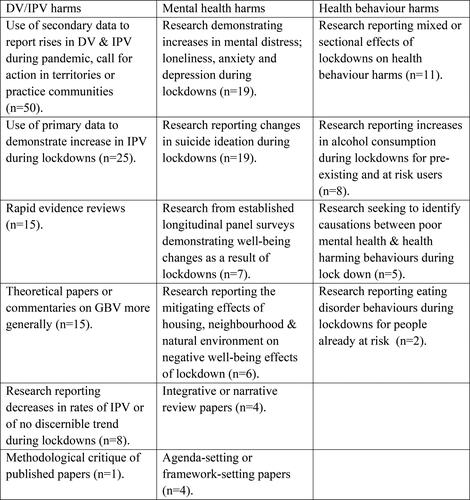

Informed by the author’s previous work on the meaning of home during Covid-19 social distancing measures, (Gurney, Citation2020) the systematic literature mapping exercise aimed to identify the extent of three putative types of lockdown harms experienced at home; (i) domestic violence and intimate partner violence; (ii) mental health and well-being; (iii) health behaviour harms. The distribution of papers included in these areas and the themes extracted from them is illustrated in . There is not the space in this paper to provide detailed systematic coverage of all the themes for each type of harm identified. Instead, for each area of harm, at least one theme will be considered in detail with reference made to relevant papers whilst a brief narrative review will be outlined with respect to the remaining themes, gaps or patterns in the literature map. A longer monograph based on the review is in preparation.

Domestic violence and intimate partner violence

The term domestic violence (DV) refers to harms which occur at home. It is a broad term which inter alia also encompasses intimate partner violence (IPV),—a form of abuse perpetrated by a current or ex‐partner (Bradbury‐Jones & Isham, Citation2020, p. 2047)—and child-to-parent violence (CPV). Five distinct themes (see ) emerged in the analysis of the research papers published on DV and IPV. Due to constraints of space only two of these themes will considered in detail here. Before that though, the sheer volume of material published on the subject which spoke with a common voice of a shared experience should be noted. Almost without exception, confinement within the home during lockdowns exposed previous victims of DV and IPV to greater risks of physical, sexual, emotional and verbal violence. Home became a ‘perpetual danger zone’ (Ando, Citation2020, p. 7) of ‘intimate terrorism’ (Gibson, Citation2020, p. 340). This, coupled with the psychological effects of being locked in with a perpetrator who has an opportunity to extend their violence and power, and the withdrawal or inability to access support services constituted what many observers referred to as a public health emergency. The United Nations referred to the growth in reports of IPV during the first lockdowns as a ‘shadow pandemic’ (UN Women, Citation2020).

The first key theme concerns the large number of studies which reported increases in the incidence of IPV during lockdowns. Three papers which collectively draw on 10,252 responses to surveys are considered below.

First, IPV grew by 23.8% amongst a convenience sample of 8,951 women taking part in an online self-reported victimisation survey during a lockdown in Spain during April/May 2020. Being in lockdown and experiencing economic stress were independently correlated with different types of violence, such that when both couples were in lockdown together at home psychological abuse was more likely to occur (but was less likely to be reported), whereas economic stress alone predicted sexual and physical violence (Arenas-Arroyo et al., Citation2021).

Second, a convenience sample of 550 married women in India reported a 33% rise in ‘spousal violence’ during lockdown in May 2020. When asked to explain what precipitated the violence, 23.8% of victims suggested that ‘too much time being spent at home’ was the cause. 76% of those experiencing abuse felt depressed because of the violence and 37% reported suicidal thoughts (Pattojoshi et al., Citation2021).

Third, a snowball sample of 751 women in Tunisia suggested a 236% increase (from 4.4% to 14.8% of the total sample) in the experience of IPV at home during lockdown. Victims had higher self-reported scores for depression, anxiety, and stress and were more likely (than the remaining 85.2%) to have experienced IPV before. Those with a pre-existing history of IPV were found to have more severe symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress (Sediri et al., Citation2020). The length of confinement at home is significant here, implying perhaps a process by which harms are accumulated and produced in the manner of a ‘harm factory’.

Further, an American study of IPV victims attending a radiology clinic during lockdown, reported a 180% increase in IPV and twice the number of ‘high risk mechanism deep injuries’ (strangulation, stab injuries, burns, or use of weapons such as knives and guns) than over the previous three year period (Gosangi et al., Citation2021); a study in Peru noted a 48% increase in calls to a national helpline compared to calls during the previous three years (Agüero, Citation2021) and in Italy a 191% increase in calls made to 58 IPV support centres compared to the previous three years was noted in April 2020 (Lundin et al., Citation2020).

demonstrates that a significant number of papers reporting on the need to respond to IPV or DV as a public health emergency were included for review. This included a large number of editorial and short correspondence papers which, in retrospect might have been excluded from the analysis. A common theme amongst these papers was the use of secondary data which claimed to show increases in rates of IPV or DV. Media reports of increased calls to helplines or of publicly available police data were typical sources. Some caution needs to be exercised in interpreting such data. Calls to helplines are not a reliable indicator and may understate the extent of violence since a perpetrator may have access to a victim’s phone or may not allow them the privacy to make a call. A small number of newspaper articles such as Graham-Harrison et al. (Citation2020) published in The Guardian (UK) were cited numerous times. The figures contained in this news story were subsequently and uncritically reported out of context. The original article drew on statements from DV and IPV campaign groups’ reactions to calls which they had received on helplines. Moreover, ‘increased rates’ were often not adequately contextualised with pre-lockdown longitudinal data or with reference to sample sizes. Whilst this should not be read as an attempt to deny the reality of many victims’ experiences, such reporting lacks the academic rigour of other papers reported above and may serve to understate the extent of the harms occurring. Any evidence of IPV and DV is newsworthy and of grave import, but this should not obscure the importance of reliably and faithfully reporting results and not, for instance, leaking results to the media prior to peer review (see Reingle Gonzalez et al., Citation2020 for a critical commentary on an incidence of this).

After early lockdowns subsided, interest in DV and IPV returned to pre-lockdown levels, but the systematic harms experienced at home continue. IPV is a harm which most often takes place at home in private, but it should not be considered in isolation from the patriarchal social relations, systemic gender-based violence (GBV) and femicide which occurs across the world. It is a social harm even though it is a private act. Although in many countries IPV has been criminalised, in others it has not and thus, by non-action, social harm occurs. For example, in a paper about IPV in Iran, (Naghizadeh et al., Citation2021) respondents were asked whether they had been ‘flogged or stoned’ as part of their physical abuse whilst ‘more than 90% of married Pakistani women reportedly endure physical or sexual abuse’ (Waheed, 2020 in Baig et al., Citation2020, p. 525). Gaps worthy of further research include the relationship between IPV and housing policy (although see Hastings et al., Citation2021; Irving-Clarke & Henderson, Citation2020) such that IPV might be conceptualised as a housing emergency and not ‘just’ a public health emergency, the lack of qualitative data allowing victims’ voices in accounts of violence, a lack of longitudinal data which demonstrates statistically significant changes in the incidence of IPV, nor any recognition that IPV and DV is experienced by people with a wide range of gender identities and sexual orientations.

During stay-at-home lockdowns, increases in rates of DV and IPV were widely reported across the world. The violence reported in this review took place at home, in private beyond the gaze of the state, neighbours and friends. Unable to avoid their abusers during lockdowns, victims suffered prolonged and sustained exposure to the risk of harm from a violent partner in constantly close proximity. Prolonged periods of time confined to the home environment exposed victims to greater risk of harm. These private acts of violence were social harms. International variations in rates of IPV are a product of cultural attitudes and of decisions made by governments on whether to criminalise this form of violence. They have a social gradient with rates of IPV highest in least developed countries and lowest in most developed countries (World Health Organization, Citation2021, pp. xiii–ix), moreover even in countries where domestic violence is criminalised there are wide variations regarding the status of psychological violence and coercive control (Barlow et al., Citation2020; European Parliament, Citation2020). A social harm lens reveals the dark side of home as a place of risk; a harmful container where harms occur. As noted above, IPV was frequently reported as a public health emergency during lockdowns. A social harm lens suggests that it could equally be understood as a housing emergency.

Mental health harms

Due to the inclusion of a number of longitudinal or panel surveys which offer the possibility of reliably measuring change and the standardisation of well-being, mental health and happiness indicators, there is considerable scientific rigour to be found in the papers which address the mental health harms of Covid-19 lockdowns. The scale of mental health harms attributable to lockdowns at home is substantial; for instance, a study using Swiss wellbeing data estimated that 2.1% of the population would suffer 9.79 YLL (years of life lost) due to ‘the psychosocial consequences’ of Covid-19 lockdowns (Moser et al., Citation2020). As with IPV harms, there is a pronounced social gradient to the mental health consequences of lockdowns (Campion et al., Citation2020).

Analyses of data from panel surveys were able to effectively capture changes in mental health at home during lockdown. Thus, in April 2020, during the first stay-at-home lockdown in the UK, Chandola et al. (Citation2020) found that 37.2% of a sample of 13,754 people in the UK Household Longitudinal Survey (UKHLS) experienced common mental disorders (CMD) such that treatment was needed, but note that this fell back to 25.8% by July 2020 when lockdown restrictions had been removed; similarly, in a sample of 11,980 people from the UKHLS, Banks and Xu (Citation2020) found that standard mental health scores were 8.1% higher than predicted for April 2020; furthermore, Niedzwiedz et al. (Citation2021) found an increase in rates of psychological distress from 19.4% of the population in 2017–2019 to 30.6% in April 2020 based on a sample of 9,748 people in UKHLS and that women of all ages and young adults suffered most in this respect.

Research using standardised well-being measures reported statistically significant self-rated deteriorations in mental health, coupled with increases in generalised anxiety disorders and depressive symptoms during lockdowns consistent with findings of the rapid evidence reviews published at the beginning of 2020 (Brooks et al., Citation2020; Gurney, Citation2020). Evidence which demonstrated an increase in mental health harms in Australia (Fisher et al., Citation2020); Bangladesh (Ali et al., Citation2020); Italy (Fiorillo et al., Citation2020); Georgia (Makhashvili et al., Citation2020); Poland (Bartoszek et al., Citation2020); and USA (Marroquín et al., Citation2020) suggests similar international experiences of home during lockdowns. Far from being a place of refuge, nourishment, and safety, typically associated with ontological security (Gurney, Citation2021b), many people’s experiences of home during enforced lockdowns were the fears, anxieties and existential threats associated with ontological insecurity.

Despite predictions claiming deteriorations in mental health would lead to an increase in suicide rates during stay-at-home lockdowns (Reger et al., Citation2020; Sher, Citation2020), there is no evidence to suggest this has occurred. Four studies reveal statistically significant self-reported increases in suicidal thoughts; a 17.5% increase during lockdown from a sample of 907 people in USA (Ammerman et al., Citation2021); a 10% increase from a sample of 443 in Poland (Talarowska et al., Citation2020); a 10.8% increase from a sample of 1,970 in Taiwan (Li et al., Citation2020); and an 18% of a sample of 4,121 reported thoughts of suicide or self-harm during lockdown in the UK (Iob et al., Citation2020). Nevertheless, research undertaken in Australia (Leske et al., Citation2021) and Germany (Radeloff et al., Citation2021) did not find any changes in suicide rates during stay-at-home lockdown periods. An increase in suicidal thoughts but no corresponding change in suicide rates is noteworthy but it is inappropriate to make any speculative remarks on those findings here.

A number of papers which made specific associations between housing, the built environment and well-being during Covid-19 lockdowns can also be identified in the literature reviewed. Taken together, they demonstrate how greater exposure to housing precarity, and poor neighbourhood quality tends to amplify the pre-existing (non-housing) social determinants of health. Thus, an evidence review of the direct and indirect health consequences of eviction and housing displacement during Covid-19 (Benfer et al., Citation2021) notes the threat of eviction can increase levels of stress, anxiety, and depression which, in turn, can weaken the immune system making those already at the greatest risk of excess mortality due to social determinants causes, at greater risk for Covid-19 contagion and mortality. 171 participants in a Scottish 1936 birth cohort study who completed a survey in May/June 2020 when the first UK lockdown was being relaxed reported better self-rated physical health with frequency of garden use. Critically, for this group of 84-year-olds, neither gardening nor relaxing in the garden was found to be correlated with improved health outcomes per se, but the frequency of garden use was (Corley et al., Citation2021). The results from an online survey to a sample of 5,218 international European respondents demonstrated that self-reported incidences of mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression were closely associated with the severity and duration of a stay-at-home lockdown. A follow-up survey with 3,404 Spanish respondents demonstrated that the negative mental health effects of lockdown were significantly mediated by access to blue/green spaces in the form of gardens, patios and scenic views from home with important socially graded implications for access to private and public recreational spaces (Pouso et al., Citation2021).

Whilst there is scope for more work on the cumulative effects of housing design and housing policy upon mental health harms experienced at home, the papers reported here all add to the weight of evidence which suggests that social inequality, housing inequalities and health inequalities are inextricably bound up. What is still unclear is how and in what ways prolonged exposure to harmful homes is a mechanism by which health inequalities are caused. What seems clear however, is that a social harm lens offers a fresh perspective on the structural nature of mental health and well-being inequalities and their housing contexts. More work is needed here to assess the extent to which home might offer an ontological security for some and how the impacts of structural violence are mediated by the lived experiences of housing, homelessness and home.

Health harming behaviours

The slow harm of health harming behaviours practised in smoking, drinking alcohol, poor diet and lack of physical activity is the main cause of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) such as coronary heart disease, stroke, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, kidney disease, some forms of cancer, liver and respiratory diseases, and obesity. They are estimated to account for 40% of all deaths annually in USA and are closely associated with the broader social determinants of health since they tend to reinforce inequalities located in the social structure (Bambra et al., Citation2020). The harm-from-home perspective outlined earlier in this paper reminds us that harm occurs in private, at home, behind closed doors. The papers reviewed here provide ample evidence to suggest that during periods of lockdown, home offers insalubrious affordances which risk the development of NCDs because of slow harms.

A survey of 1,491 adults in Australia found evidence for negative changes in levels of physical activity, alcohol consumption and smoking during the April 2020 lockdown. Negative changes in physical activity, sleep, smoking and alcohol intake were associated with higher depression, anxiety and stress symptoms (Stanton et al., Citation2020). Similarly, in the UK, an analysis of panel data revealed that binge drinking increased from 10.8% of a sample of 9,748 adults during 2017–2019 to 16.8% in an April 2020 lockdown (Niedzwiedz et al., Citation2021); and in the USA, 34% of 1,982 respondents to an online survey reported binge drinking during lockdown (Weerakoon et al., Citation2020). Declining levels of physical activity and reductions in fruit and vegetable intake (Naughton et al., Citation2021) and increases in eating disorders were reported in Scotland and Italy respectively (Cecchetto et al., Citation2021).

A smaller number of studies reported patterns of health harming behaviours which were either less harmful or presented a more complicated picture with mixed results: thus, as many respondents reported less harmful drinking and eating behaviours in a Scottish study as did people reporting more harmful behaviours (Ingram et al., Citation2020) whilst a study in Poland found younger people drank less alcohol, whilst older people, and those with a history of excessive alcohol consumption drank more during lockdown periods (Chodkiewicz et al., Citation2020).

There is undoubtedly scope for more research on the ways in which home offers affordances for health harming behaviours to occur. The dangers of using alcohol to relax and escape external stressors are well established in Public Health and its consequences are well known (Burton et al., Citation2016). The Hu et al. (Citation2021) synergistic model of Covid-19 excess mortality contends that health harming behaviours such as harmful drinking or emotional eating are driven by systemic discrimination, structural racism and injustice/impunity. Seen in this way, the opportunities for research on the contributions which housing policy might make to understanding the health consequences of displacement pressure is significant. Might a relationship between the introduction of rent controls and reductions in alcohol consumption or emotional eating be identified for example?

To sum up, the review demonstrates that some health harming behaviours increased during stay-at-home lockdowns. Before the Covid-19 pandemic, one of the most significant public health challenges in many developed countries was addressing health harming behaviours to reduce the burden of disease caused by NCDs. Many of these behaviours were home-based practices. Even before the onset of Covid-19 lockdowns a shift away from drinking in licensed premises to home-drinking could be identified in many countries. Thus, in 2018/19, 72.6% of all alcohol sold in Scotland was ‘off-sales’ for consumption at home, an increase from 59.6% in 1999/2000 (Public Health Scotland, 2021). Post-pandemic, behavioural public health policies to nudge populations into making healthier choices must continue to address where these behaviours occur. Narratives of freedom from interference are a mainstay of libertarian celebrations of home as a haven, so whether housing studies or housing policy can (or should) make any contribution to reductions in health harming behaviour is a moot point. Further research is needed here.

Discussion

The foregoing review demonstrates that the relationships implied in the social inequality, housing and health trifecta can usefully be understood in relation to the transmission, sorting and amplification of various social harms. Central to this argument is the contention that social harms constitute the generative mechanisms by which social inequalities and housing inequalities cause health and well-being inequalities to occur. Social harms are the triggers in the system. These are not necessarily the simple, visible linear relationships which housing researchers have often implied but are instead messy, mediated by social practices and frequently invisible. Nevertheless, referring back to the illustration in want to suggest that it is the flows of social harm which activate the triangle, transforming it into a dynamic, conceptual space. These harms wash through the conceptual space transporting the consequences of structural inequalities and policy decisions which are then accumulated, deposited or ‘pooled’ in the home. Whilst home may sometimes offer a nourishing space of ontological security, this is frequently overstated in the housing literature. My argument is that home is also and perhaps more frequently, a key locus in a geography of harm because it is where the pooling of social harms is most acute. This pooling was particularly visible during the stay-at-home lockdowns of the Covid-19 pandemic, where exposure to harms was particularly prolonged and intense.

In answering the question, ‘what is it about housing which causes poor (or good) health and well-being?’ this paper has focused upon those container-like properties of home which render it a dangerous place wherein prolonged exposure to various social harms may occur. Two points follow from this. First, for people experiencing homelessness, the absent presence of a permanent and secure home does not diminish the fact they are experiencing harms as a direct result of their housing situation. More work is needed to explicate the relationship between housing, homelessness, and social harm in order to demonstrate the health consequences of policy failure and indifference. Second, housing and housing policy offers a useful test-bed to work through typologies of physical harms, mental health harms, financial and economic harms, cultural harms, harms of recognition and autonomy harms (Canning & Tombs, Citation2021, pp. 66–67; Pemberton, Citation2015, pp. 27–31) outlined in the zemiological literature. Much of the work on social harm to date has focussed upon workplace harms such as industrial injury and death, but we typically spend much more time at home than in work and, of course, home-places and workplaces have become more fluid, conflated spaces since the stay-at-home lockdowns of the Covid-19 pandemic.

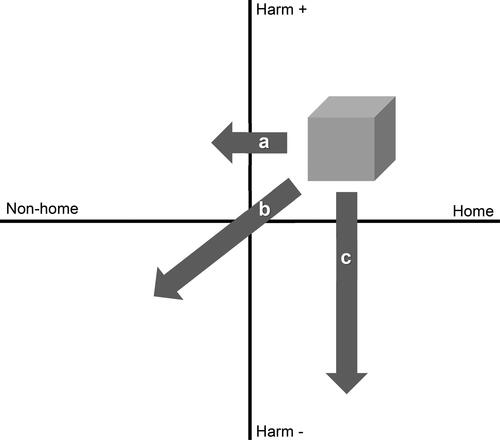

The consequences of deploying a social harm lens in housing and health research include the identification of radical new narratives in framing and evaluating housing policy. A frequently stated outcome of housing policy is to provide decent homes for all, but to what extent might homes which are ‘free from harms’ also provide a focus for lobbying on policies which seek to address housing and health inequalities? below offers a speculative attempt to represent how discussions about the regulation and reduction of social harm could be incorporated into discussions of housing policy and housing policy analysis.

In the diagram, the shaded cube represents a hypothetical social harm (IPV, poor mental health, risks from fire, for example). The inclusion of the arrows suggests hypothetical policy interventions which might shift or stretch the harm into different quadrants; either horizontally by introducing some degree of surveillance or scrutiny such that harms are no longer occurring unobserved in private spaces of the home; or vertically through the regulation of harms so that the degree of risk and exposure is reduced.

Arrow ‘a’ represents a hypothetical approach to shifting harm from home which will have profound implications for libertarian accounts of home as a space of freedom from interference. A shift might be accomplished, for example through the provision of panic button protocols for housing support services which would render IPV harms visible to external surveillance and support, or via wearable technologies which might make health harming behaviours visible to medical professionals. These are radical and controversial suggestions, but allowing a degree of surveillance at home might be a cost of preventing intimate violence or physical health harms. Whether all citizens might think that this cost is worth paying is a moot point. Lloyd (Citation2019, pp. 19–24) considers contrasting libertarian positions on the ‘freedom-from’ (surveillance, for example) and the ‘freedom-to’ (drink alcohol excessively, for example) which have obvious echoes in the narratives against mask-wearing and vaccination during the Covid-19 pandemic. More work on the philosophical and ethical contexts of a social harm analysis of housing policy is needed. Arrow ‘b’ describes an intervention where harm is shifted from home whilst at the same time is also being reduced by regulation. Such a shift might describe interventions which enrich neighbourhoods and communities with those qualities of home, (such as relaxation or comfort) which might precipitate harm through lack of exercise or emotional eating when practised in a dwelling. There are potential connections to the emerging infrastructures of care literature here, thus Lopes et al. (Citation2018) discuss the deleterious health consequences of thermal comfort being artificially maintained in privatised air-conditioned home spaces whilst there is a simultaneous loss of provision of public or collective infrastructures of shade, public water, and places to rest and wait. Certainly, harm and care might usefully be understood as obverse or counterfactual states if we were to rethink housing policy in terms of harm reduction and regulation. Finally, arrow ‘c’ in the diagram represents reductions in harm through, for example, improvements to building regulations, fire safety and consumer protection. Tombs, (Citation2020) account of the Grenfell Fire as a series of regulatory failures leading to loss of life is a reminder of why the social harm perspective might offer a powerful call to action in framing housing policy and housing policy debates.

Conclusion

This paper has argued that to make sense of the social inequality, housing, and health trifecta a social harm perspective offers some answers. An international systematic literature mapping review demonstrated that during the lockdowns associated with the Covid-19 pandemic, home was revealed to be a place where social harms were often stored and amplified. Traditionally, housing research proceeds on the assumption that home offers a host of positive attributes. Rethinking home as a dangerous place wherein social harms occur offers several possibilities for housing policy analysis. First, a focus on social harm provides a radical new narrative by which housing policy might be framed. Could social harm be a rallying point for housing campaign groups? Could a social harm lens be used to benchmark policy evaluations? Conversely, might the social harm approach be developed to offer an alternative tool for policy analysis in itself? Moreover, a focus on social harm offers a new perspective for housing researchers to engage with health policy debates and for epidemiological researchers to look beyond the physical and hard material structures of dwellings. Second, in outlining a social harm perspective, a number of questions for further research and theory development are implied. An obvious next step would be to conceptualise the various harms associated with occupying certain types of housing contra those harms generated by activities which occur at home, rather than in other places. I have suggested that home is a key locus in a geography of harm, but this assertion needs to be tested. and in this paper offer conceptual provocations concerning the social inequality, health, and housing trifecta and on hypothetical approaches to harm reduction. Whether such a visual shorthand for more fully developed arguments serves to clarify or confound remains to be seen. Beyond criminology, a focus on housing, homelessness and home may offer an opportunity for zemiologists to extend and develop arguments about the ontological and spatial bases of social harm. There are other questions, of course, notably in relation to social murder, ontological security, home un-making and housing as an infrastructure of care, but these will be explored in subsequent publications.

It is inevitable that an agenda-setting paper offers as many questions as it provides answers, but at a time when housing policy is uniquely placed to contribute towards building back fairer it is appropriate that housing researchers take stock of their conceptual tools. A social harm perspective offers some insight but more work is needed before it becomes a recognised building block for housing studies.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the helpful and detailed comments of two anonymous referees which have improved this paper. I am also indebted to Emma Baker, Mhairi Mackenzie, Fiona Powell, Jenny Preece and Steve Tombs for their timely suggestions and support, and to participants at seminars organised by Queen’s University Belfast, Heriot-Watt University and South Yorkshire Housing Association for asking me some tough questions which helped sharpen my argument. Finally, I’m delighted to be able to thank students on my courses in Housing Policy; Housing, Inequality and Society and Health Policy at the University of Glasgow for their enthusiasm in discussing themes outlined in this paper.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this article.

References

- Aalbers, M. (2016). Housing finance as harm. Crime, Law and Social Change, 66(2), 115–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-016-9614-x

- Abbasi, K. (2021). Covid-19: Social murder, they wrote—elected, unaccountable, and unrepentant. British Medical Journal, 372(314). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n314

- Agüero, J. M. (2021). COVID-19 and the rise of intimate partner violence. World Development, 137, 105217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105217

- Ahmad, K., Erqou, S., Shah, N., Nazir, U., Morrison, A. R., Choudhary, G., & Wu, W. C. (2020). Association of poor housing conditions with COVID-19 incidence and mortality across US counties. PloS One, 15(11), e0241327. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241327

- Ali, M., Ahsan, G. U., Khan, R., Khan, H. R., & Hossain, A. (2020). Immediate impact of stay-at-home orders to control COVID-19 transmission on mental well-being in Bangladeshi adults: Patterns, Explanations, and future directions. BMC Research Notes, 13(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-020-05345-2

- Ammerman, B., Burke, T., Jacobucci, R., & McClure, K. (2021). Preliminary investigation of the association between COVID-19 and suicidal thoughts and behaviors in the U.S. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 134, 32–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.12.037

- Ando, R. (2020). Domestic violence and Japan’s COVID-19 pandemic. Asia-Pacific Journal-Japan Focus, 18(18), 5475.

- Angel, S., & Bittschi, B. (2019). Housing and health. Review of Income and Wealth, 65(3), 495–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/roiw.12341

- Arenas-Arroyo, E., Fernandez-Kranz, D., & Nollenberger, N. (2021). Intimate partner violence under forced cohabitation and economic stress: Evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Public Economics, 194, 104350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104350

- Baig, M. A. M., Ali, S., & Tunio, N. A. (2020). Domestic violence amid COVID-19 pandemic: Pakistan’s perspective. Asia-Pacific Journal of Public Health, 32(8), 525–526. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539520962965

- Baker, E., Beer, A., Lester, L., Pevalin, D., Whitehead, C., & Bentley, R. (2017). Is housing a health insult?International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(6), 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14060567

- Baker, E., Lester, L., Beer, A., & Bentley, R. (2019). An Australian geography of unhealthy housing. Geographical Research, 57(1), 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12326

- Bambra, C., Lynch, J., & Smith, K. E. (2021). The unequal pandemic: Covid-19 and health inequalities. Policy Press.

- Bambra, C., Riordan, R., Ford, J., & Matthews, F. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 74(11), 964–968. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-214401

- Banks, J., & Xu, X. (2020). The mental health effects of the first two months of lockdown during the COVID‐19 pandemic in the UK. Fiscal Studies, 41(3), 685–708. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-5890.12239

- Barlow, C., Johnson, K., Walklate, S., & Humphreys, L. (2020). Putting coercive control into practice: Problems and possibilities. British Journal of Criminology, 60 (1), 160–179. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azz041

- Bartoszek, A., Walkowiak, D., Bartoszek, A., & Kardas, G. (2020). Mental well-being (depression, loneliness, insomnia, daily life fatigue) during COVID-19 related home-confinement—A study from Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7417. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207417

- Benfer, E. A., Vlahov, D., Long, M. Y., Walker-Wells, E., Pottenger, J. L., Gonsalves, G., & Keene, D. E. (2021). Eviction, health inequity, and the spread of covid-19: Housing policy as a primary pandemic mitigation strategy. Journal of Urban Health, 98(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-020-00502-1

- Blakely, T., Baker, M. G., & Howden-Chapman, P. (2011). Does housing policy influence health?Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 65(7), 598–599. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2010.132407

- Bradbury‐Jones, C., & Isham, L. (2020). The pandemic paradox: The consequences of COVID-19 on domestic violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(13–14), 2047–2049. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15296

- Braveman, P., & Gottlieb, L. (2014). The Social Determinants of Health: It’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Reports (Washington, DC: 1974), 129(1_suppl2), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549141291S206

- Brooks, S. K., Webster, R. K., Smith, L. E., Woodland, L., Wessely, S., Greenberg, N., & Rubin, G. J. (2020). The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: Rapid review of the evidence. The Lancet, 395(10227), 912–920. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8

- Brown, P., Newton, D., Armitage, R., & Monchuk, L. (2020). Lockdown. Rundown. Breakdown. The COVID-19 lockdown and the impact of poor-quality housing on occupants in the North of England. Northern Housing Consortium.

- Burton, R., Henn, C., Lavoie, D., O’Connor, R., Perkins, C., Sweeney, K., Greaves, F., Ferguson, B., Beynon, C., Belloni, A., Musto, V., Marsden, J., Sheron, N., & Wolff, A. (2016). The public health burden of alcohol and the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of alcohol control policies: An evidence review. Public Health England. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/733108/alcohol_public_health_burden_evidence_review_update_2018.pdf

- Campion, J., Javed, A., Marmot, M., & Valsraj, K. (2020). The need for a public mental health approach to COVID-19. World Social Psychiatry, 2(2), 77–83. https://doi.org/10.4103/WSP.WSP_48_20

- Canning, V., & Tombs, S. (2021). From social harm to zemiology: A critical introduction. Routledge.

- Cecchetto, C., Aiello, M., Gentili, C., Ionta, S., & Osimo, S. A. (2021). Increased emotional eating during COVID-19 associated with lockdown, psychological and social distress. Appetite, 160, 105122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105122

- Chadwick, E. (1842). Report to Her Majesty’s Principal Secretary of State for the Home Department from the Poor Law Commissioners, on an Inquiry into the sanitary condition of the labouring population of Great Britain: With appendices. HMSO. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/vgy8svyj

- Chandola, T., Kumari, M., Booker, C., & Benzeval, M. (2020). The mental health impact of COVID-19 and lockdown-related stressors among adults in the UK. Psychological Medicine, First View, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720005048

- Chodkiewicz, J., Talarowska, M., Miniszewska, J., Nawrocka, N., & Bilinski, P. (2020). Alcohol consumption reported during the COVID-19 pandemic: The initial stage. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4677. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134677

- Corley, J., Okely, J. A., Taylor, A. M., Page, D., Welstead, M., Skarabela, B., Redmond, P., Cox, S. R., & Russ, T. C. (2021). Home garden use during COVID-19: Associations with physical and mental wellbeing in older adults. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 73, 101545. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101545

- Elliott-Cooper, A., Hubbard, P., & Lees, L. (2020). Moving beyond Marcuse: Gentrification, displacement and the violence of un-homing. Progress in Human Geography, 44(3), 492–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519830511

- Engels, F. (1887/1993). The condition of the working class in England. Oxford University Press.

- European Parliament. (2020). Violence against women. Psychological violence and coercive control.https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2020/650336/IPOL_STU(2020)650336_EN.pdf

- Fiorillo, A., Sampogna, G., Giallonardo, V., Del Vecchio, V., Luciano, M., Albert, U., Carmassi, C., Carrà, G., Cirulli, F., Dell’Osso, B., Nanni, M. G., Pompili, M., Sani, G., Tortorella, A., & Volpe, U. (2020). Effects of the lockdown on the mental health of the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: Results from the COMET collaborative network. European Psychiatry, 63(1), E87. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.89

- Fisher, J. R., Tran, T. D., Hammarberg, K., Sastry, J., Nguyen, H., Rowe, H., Popplestone, S., Stocker, R., Stubber, C., & Kirkman, M. (2020). Mental health of people in Australia in the first month of COVID‐19 restrictions: A national survey. Medical Journal of Australia, 213(10), 458–464. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.50831

- Gibson, J. (2020). Domestic violence during COVID-19: The GP role. British Journal of General Practice, 70(696), 340–340. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp20X710477

- Gosangi, B., Park, H., Thomas, R., Gujrathi, R., Bay, C. P., Raja, A. S., Seltzer, S. E., Chadwick Balcom, M., McDonald, M. L., Orgill, D. P., Harris, M. B., Boland, G. W., Rexrode, K., & Khurana, B. (2021). Exacerbation of physical intimate partner violence during Covid-19 pandemic. Radiology, 298(1), E38–E45. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2020202866

- Graham, R. (1818). Practical observations on continued fever, especially that form at present existing as an epidemic; with some remarks for the most efficient means for its suppression. John Smith and Son. https://wellcomelibrary.org/item/b30795849.

- Graham-Harrison, E., Giuffrida, A., Smith, H., & Ford, L. (2020, March 28). Lockdowns around the world bring rise in domestic violence. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/mar/28/lockdowns-world-rise-domestic-violence

- Gurney, C. M. (1990). The meaning of home in the decade of owner occupation: Towards an experiential research agenda. SAUS Working Paper 88. University of Bristol, School of Advanced Urban Studies.

- Gurney, C. M. (2020). Out of harm’s way? Critical remarks on harm and the meaning of home during the 2020 COVID-19 social distancing measures. CaCHE Working Paper. UK Centre for Collaborative Housing Evidence. https://housingevidence.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/200408-out-of-harms-way-craig-gurney-final.pdf

- Gurney, C. M. (2021a). Cold case or hot topic? On the rediscovery of "social murder" in housing studies [Manuscript in preparation]. School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Glasgow.

- Gurney, C. M. (2021b, July 28). Ontological security. A term of contradictions. Housing Studies Association. https://www.housing-studies-association.org/articles/318-ontological-security-a-term-of-contradictions

- Hastings, A., Mackenzie, M., & Earley, A. (2021). Domestic abuse and housing. Domestic abuse and housing connections and disconnections in the pre-Covid-19 policy world. Interim report. UK Centre for Collaborative Housing Evidence. https://housingevidence.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/DA-Covid-19-report.pdf

- Hillyard, P., Pantazis, C., Tombs, S., & Gordon, D. (Eds.). (2004). Beyond criminology: Taking harm seriously. Pluto Press.

- Hillyard, P., & Tombs, S. (2007). From ‘crime’ to social harm?Crime, Law and Social Change, 48(1–2), 9–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-007-9079-z

- Hiscock, R., Kearns, A., MacIntyre, S., & Ellaway, A. (2001). Ontological security and psycho-social benefits from the home: Qualitative evidence on issues of tenure. Housing, Theory and Society, 18(1–2), 50–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036090120617

- Hodkinson, S. (2019). Safe as Houses: Private greed, negligence and housing policy after Grenfell. Manchester University Press.

- Horne, R., Willand, N., Dorignon, L., & Middha, B. (2020). The lived experience of COVID-19: Housing and household resilience. AHURI Final Report No. 345. Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited. https://doi.org/10.18408/ahuri532560

- Hu, M., Roberts, J. D., Azevedo, G. P., & Milner, D. (2021). The role of built and social environmental factors in Covid-19 transmission: A look at America’s capital city. Sustainable Cities and Society, 65, 102580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2020.102580

- Ingram, J., Maciejewski, G., & Hand, C. J. (2020). Changes in diet, sleep, and physical activity are associated with differences in negative mood during COVID-19 lockdown. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2328.

- Iob, E., Steptoe, A., & Fancourt, D. (2020). Abuse, self-harm and suicidal ideation in the UK during the COVID-19 pandemic. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 217(4), 543–546. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2020.130

- Irving-Clarke, Y., & Henderson, K. (2020). Housing and domestic abuse: Policy into practice. Routledge.

- Kearns, A. (2020). Housing as a public health investment. British Medical Journal, 371, m4775. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4775

- Kearns, A., Hiscock, R., Ellaway, A., & Macintyre, S. (2000). Beyond four walls’. The psycho-social benefits of home: Evidence from west central Scotland. Housing Studies, 15(3), 387–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030050009249

- Kotlar, B., Gerson, E., Petrillo, S., Langer, A., & Tiemeier, H. (2021). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and perinatal health: A scoping review. Reproductive Health, 18(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01070-6

- Lawrence, R. J. (2017). Constancy and change: Key issues in housing and health research, 1987–2017. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(7), 763. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14070763

- Leske, S., Kõlves, K., Crompton, D., Arensman, E., & De Leo, D. (2021). Real-time suicide mortality data from police reports in Queensland, Australia, during the COVID-19 pandemic: An interrupted time-series analysis. Lancet Psychiatry, 8(1), 58–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30435-1

- Li, D. J., Ko, N. Y., Chen, Y. L., Wang, P. W., Chang, Y. P., Yen, C. F., & Lu, W. H. (2020). COVID-19-related factors associated with sleep disturbance and suicidal thoughts among the Taiwanese public: A Facebook survey. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(12), 4479. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124479

- Lloyd, A. (2019). The harms of work. An ultra-realist account of the service economy. Bristol University Press.

- Lopes, A., Healy, S., Power, E., Crabtree, L., & Gibson, K. (2018). Infrastructures of Care: Opening up “Home” as Commons in a Hot City. Human Ecology Review, 24(2), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.2307/26785905

- Lundin, R., Armocida, B., Sdao, P., Pisanu, S., Mariani, I., Veltri, A., & Lazzerini, M. (2020). Gender-based violence during the COVID-19 pandemic response in Italy. Journal of Global Health, 10(2), 020359. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.10.020359

- Madigan, R., Munro, M., & Smith, S. (1990). Gender and the meaning of home. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 14(4), 625–647. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.1990.tb00160.x

- Makhashvili, N., Javakhishvili, J. D., Sturua, L., Pilauri, K., Fuhr, D. C., & Roberts, B. (2020). The influence of concern about COVID-19 on mental health in the Republic of Georgia: A cross-sectional study. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-020-00641-9

- Marcus, J. (2021, July 3). Miami building collapse: Lack of steel reinforcements may have caused Miami building collapse, engineers say. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/surfside-miami-building-collapse-cause-b1877682.html

- Marmot, M., Allen, J., Goldblatt, P., Herd, E., & Morrison, J. (2020). Build back fairer: The COVID-19 marmot review. The pandemic, socioeconomic and health inequalities in England. Institute of Health Equity.

- Marroquín, B., Vine, V., & Morgan, R. (2020). Mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Effects of stay-at-home policies, social distancing behavior, and social resources. Psychiatry Research, 293, 113419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113419

- McCarthy, L. (2018). (Re)conceptualising the boundaries between home and homelessness: The unheimlich. Housing Studies, 33(6), 960–985. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2017.1408780

- Mills, C. W. (1959). The sociological imagination. Oxford University Press.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

- Moreira, A., & Hick, R. (2021). COVID‐19, the Great Recession and social policy: Is this time different?Social Policy & Administration, 55(2), 261–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12679

- Moreira, D. N., & Pinto da Costa, M. (2020). The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in the precipitation of intimate partner violence. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 71, 101606. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlp.2020.101606

- Moser, D., Glaus, J., Frangou, S., & Schechter, D. (2020). Years of life lost due to the psychosocial consequences of COVID-19 mitigation strategies based on Swiss data. European Psychiatry, 63(1), e58. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.56

- Naghizadeh, S., Mirghafourvand, M., & Mohammadirad, R. (2021). Domestic violence and its relationship with quality of life in pregnant women during the outbreak of COVID-19 disease. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 21(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03579-x

- Naughton, F., Ward, E., Khondoker, M., Belderson, P., Minihane, A. M., Dainty, J., Hanson, S., Holland, R., Brown, T., & Notley, C. (2021). Health behaviour change during the UK COVID‐19 lockdown: Findings from the first wave of the C‐19 health behaviour and well‐being daily tracker study. British Journal of Health and Psychology, 26, 624–643. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12500

- Niedzwiedz, C. L., Green, M. J., Benzeval, M., Campbell, D., Craig, P., Demou, E., Leyland, A., Pearce, A., Thomson, R., Whitley, E., & Katikireddi, S. V. (2021). Mental health and health behaviours before and during the initial phase of the COVID-19 lockdown: Longitudinal analyses of the UK household longitudinal study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 75(3), 224–231. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2020-215060

- Odone, A., Salvati, S., Bellini, L., Bucci, D., Capraro, M., Gaetti, G., Amerio, A., & Signorelli, C. (2020). The runaway science: A bibliometric analysis of the COVID-19 scientific literature. Acta Bio-Medica: Atenei Parmensis, 91(9-S), 34–39. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v91i9-S.10121

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. British Medical Journal, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Pain, R. (2019). Chronic urban trauma: The slow violence of housing dispossession. Urban Studies, 56(2), 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098018795796

- Paton, K., & Cooper, V. (2017). Domicide, eviction and repossession. In V. Cooper & D. Whyte (Eds.), The violence of austerity (pp. 164–170). Pluto Press.

- Pattojoshi, A., Sidana, A., Garg, S., Mishra, S. N., Singh, L. K., Goyal, N., & Tikka, S. K. (2021). Staying home is NOT ‘staying safe’: A rapid 8-day online survey on spousal violence against women during the COVID-19 lockdown in India. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 75(2), 64–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.13176

- Pemberton, S. (2015). Harmful societies: Understanding social harm. Policy Press.

- Pouso, S., Borja, A., Fleming, L. E., Gómez-Baggethun, E., White, M. P., & Uyarra, M. C. (2021). Contact with blue-green spaces during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown beneficial for mental health. The Science of the Total Environment, 756, 143984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143984

- Power, E., & Mee, K. J. (2020). Housing: An infrastructure of care. Housing Studies, 35(3), 484–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1612038

- Power, E., Rogers, D., & Kadi, J. (2020). Public housing and COVID-19: Contestation, challenge and change. International Journal of Housing Policy, 20(3), 313–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2020.1797991

- Public Health England. (2021). COVID-19: Mental health and wellbeing surveillance report.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-mental-health-and-wellbeing-surveillance-report

- Public Health Scotland. ( 2021). Using alcohol retail sales data to estimate population alcohol consumption in Scotland: An update of previously published estimates.https://publichealthscotland.scot/publications/using-alcohol-retail-sales-data-to-estimate-population-alcohol-consumption-in-scotland-an-update-of-previously-published-estimates/

- Radeloff, D., Papsdorf, R., Uhlig, K., Vasilache, A., Putnam, K., & Von Klitzing, K. (2021). Trends in suicide rates during the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions in a major German city. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 30, E16. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796021000019

- Rajkumar, R. P. (2020). COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 52, 102066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066

- Reger, M. A., Stanley, I. H., & Joiner, T. E. (2020). Suicide mortality and coronavirus disease 2019-A perfect storm?JAMA Psychiatry, 77(11), 1093–1094. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1060

- Reingle Gonzalez, J. M., Molsberry, R., Maskaly, J., & Jetelina, K. (2020). Trends in family violence are not causally associated with COVID-19 stay-at-home orders: A commentary on piquero. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 45(6), 1100–1110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09574-w

- Retraction Watch. ( 2021). https://retractionwatch.com/retracted-coronavirus-covid-19-papers/

- Rogers, D., & Power, E. (2020). Housing policy and the COVID-19 pandemic: The importance of housing research during this health emergency. International Journal of Housing Policy, 20(2), 177–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2020.1756599

- Rolfe, S., Garnham, L., Godwin, J., Anderson, I., Seaman, P., & Donaldson, C. (2020). Housing as a social determinant of health and wellbeing: Developing an empirically-informed realist theoretical framework. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09224-0

- Sánchez, O. R., Vale, D. B., Rodrigues, L., & Surita, F. G. (2020). Violence against women during the COVID-19 pandemic: An integrative review. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 151(2), 180–187. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13365

- Saunders, P. (1990). A nation of home owners. Unwin Hyman.

- Schelhase, M. (2020). Bringing the harm home: The quest for home ownership and the amplification of social harm. New Political Economy, 26(3), 439–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2020.1782363

- Sediri, S., Zgueb, Y., Ouanes, S., Ouali, U., Bourgou, S., Jomli, R., & Nacef, F. (2020). Women’s mental health: Acute impact of COVID-19 pandemic on domestic violence. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 23(6), 749–756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-020-01082-4

- Shaw, M. (2004). Housing and public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 25(1), 397–418. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123036

- Sher, L. (2020). The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on suicide rates. QJM, 113(10), 707–712. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcaa202

- Soaita, A., Serin, B., & Preece, J. (2020). A methodological quest for systematic literature mapping. International Journal of Housing Policy, 20(3), 3, 320–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2019.1649040

- Sorooshian, S., & Kumar, S. (2020). Contrived publications and COVID-19 communication noise. Italian Journal of Medicine, 14(4), 247–248. https://doi.org/10.4081/itjm.2020.1357

- Stanton, R., To, Q. G., Khalesi, S., Williams, S. L., Alley, S. J., Thwaite, T. L., Fenning, A. S., & Vandelanotte, C. (2020). Depression, anxiety and stress during COVID-19: Associations with changes in physical activity, sleep, tobacco and alcohol use in Australian adults. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(11), 4065. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17114065

- Sutton, A., Clowes, M., Preston, L., & Booth, A. (2019). Meeting the review family: Exploring review types and associated information retrieval requirements. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 36(3), 202–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12276

- Talarowska, M., Chodkiewicz, J., Nawrocka, N., Miniszewska, J., & Biliński, P. (2020). Mental health and the SARS-COV-2 epidemic-polish research study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(19), 7015. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197015

- Tinson, A., & Clair, A. (2020). Better housing is crucial for our health and the COVID-19 recovery. The Health Foundation. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/long-reads/better-housing-is-crucial-for-our-health-and-the-covid-19-recovery