Abstract

The growth of the private rented sector (PRS) since the 2000s in countries with lightly regulated markets has led to significant questions over its ability to provide a homely environment for tenants. Much of the research in this area argues that legal frameworks, lack of regulation and financial motives of landlords are not conducive to the provision of homes which are secure, affordable, good quality and which offer tenants an opportunity to meet their health and wellbeing needs. This is despite legislative changes that seek to raise standards in the sector and promote greater professionalisation. This paper presents findings from an evidence review of research concerning home within the PRS across OECD countries. Rather than focusing on the experiences of tenants, it considers the impacts of landlord and letting agent behaviours on tenants’ ability to make their rented house a home. We argue that landlords and letting agents can play a positive role in helping their tenants create a home, and that this offers benefits for both landlords and renters.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and related lockdowns have re-emphasised the importance of the home environment, as government mandates have shifted work, school and leisure into the home. This has generated renewed debate on the meaning of home across different housing circumstances (Byrne, Citation2020; Gezici Yalçın & Düzen, Citation2021), especially in relation to the private rented sector (PRS), where research has long highlighted the challenges tenants face in ‘settling down’, and making their rented house a home (Bate, Citation2020; Easthope, Citation2014; Hoolachan et al., Citation2017; Soaita et al., Citation2020). In nations with liberalised PRS markets, governments were forced to introduce additional regulation, restricting landlords’ power to evict, in order to prevent a homelessness crisis in the middle of the pandemic (Byrne, Citation2020). These circumstances emphasise the importance of understanding the ways in which PRS tenants are able to feel at home and, in particular, the role of landlords and letting agents in influencing processes of home-making in nations where the sector is lightly regulated. This paper reports the findings from a rapid systematic review of the research evidence to establish what is known, and to provide pointers towards improved policy and practice.

Context

‘Home’, is a complex and subjective concept layered by the interplay of ‘ideal’ imaginations, the material and regulatory conditions of a dwelling and the practices and interactions that occur there (Clapham, Citation2011; Hulse & Milligan, Citation2014; Power & Gillon, Citation2019; Soaita & McKee, Citation2019). Setting aside the multi-scalar aspects of home as nation or neighbourhood, the central focus here is that ‘home’ is an emotional and meaningful relationship between people and the property where they live (Clapham, Citation2005; Dovey, Citation1985). Multidisciplinary housing literature spanning the past 35 years has consistently highlighted common qualities that define a home in providing wellbeing effects (see, for example: Blunt & Dowling, Citation2006; Dupuis & Thorns, Citation1998; Hiscock et al., Citation2001; Kearns et al., Citation2012; Mallett, Citation2004 ). Such qualities include ontological security; haven or refuge from the stresses of everyday life; a comfortable space in which to relax and engage in care work; social status; autonomy and the importance of having a living space that can be controlled in relation to what can happen in it and who can and cannot enter (see Bate, Citation2020; Hoolachan, Citation2020 for fuller summaries of this literature). ‘Making’ a home is an ongoing, active process which is neither automatic nor straightforward (Rivlin & Moore, Citation2001). Crucially, this is not limited to aspects of physical comfort and decoration (although these are included), but also involves psychological and social processes of ‘settling’, developing the elements of haven and ontological security. Importantly, the ability to feel at home is not merely an end in itself, since there is also significant evidence that the absence of these elements of home damages health and wellbeing (Garnham & Rolfe, Citation2019a; Kearns et al., Citation2000; Rolfe et al., Citation2020).

This should, of course, not be taken to mean that everyone experiences ontological security or gains wellbeing benefits from being in their ‘home’ property. Evidence regarding the potential harms of ‘home’ (Gurney, Citation2021) has been reinforced by the increase in domestic violence during the pandemic lockdowns (Kofman & Garfin, Citation2020), whilst some homeless people can create a sense of ‘home’ without a property (McCarthy, Citation2018). However, these examples do not negate the importance of ‘home’ in the sense we are using it here – rather they emphasise its importance and the ways in which people try to create a sense of home even in circumstances where it might seem impossible.

The PRS has received significant criticism for lacking in its provision of a home for tenants. Short-term tenancy contracts, expensive living costs, poor physical conditions, and rules which prevent personalisation (e.g., hanging pictures on walls) or otherwise restrict how tenants can use their properties (e.g., no pets) combine to leave tenants feeling as though they do not live in a home but merely in a dwelling that belongs to someone else (Easthope, Citation2014; Hoolachan et al., Citation2017). Households on the lowest incomes experience the sharpest end of the PRS with many enduring substandard conditions out of fear of having their tenancy ended by the landlord or because they have come to accept such conditions as normal (Chisholm et al., Citation2020; McKee et al., Citation2020).

These issues are arguably particularly problematic in nations with a ‘lightly regulated’ PRS (Soaita et al., Citation2020), since landlords have greater flexibility regarding how they treat tenants in such contexts. Primarily the Anglophone countries of the Global North, such nations can be characterised as having liberal welfare regimes (Esping-Andersen, Citation1990) and dualist rental systems (Kemeny, Citation1995), where there is a sharp divide between social and private renting, alongside a dominant owner occupation sector. Although there is ongoing debate about the evolving nature of rental systems, with the growing impact of financialisation in many previously unitary rental systems (Stephens, Citation2020), there is still a significant divide between countries with relatively heavy PRS regulation, such as rent controls and strong tenure security (e.g., Germany) and those which are more lightly regulated, with market rents and weak tenure security (e.g., UK, USA, Australia). In the latter group, the PRS has grown substantially since the 2000s (Soaita et al., Citation2020), whilst barriers to owner occupation have risen significantly since the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–8. For example, in the UK the sector nearly doubled to 1 in 5 households in a decade (ONS, Citation2019), accompanied by increasing diversification in terms of tenants, housing growing numbers of low-income households, older households and families with children (Soaita et al., Citation2020), although many renters aspire to be in other housing tenures (Mckee et al., Citation2017). Notably, the challenges experienced by tenants in lightly regulated markets are highlighted by the growth of organisations and movements representing tenants, taking action to resist problematic landlords and drive policy change (Garnham & Rolfe, Citation2019b). We therefore focus particularly on lightly regulated markets in our review, since the evidence regarding the role of landlord behaviour is likely to be strongest where tenants lack the protections of stronger regulation.

Despite the importance of home-making to tenants’ lived experience of private renting, and the elevation of ‘home’ during the pandemic, there has been relatively little explicit focus on the role of landlords (and letting agents). This is remiss, for the tenant/landlord relationship is critical to how renters experience home and therefore worthy of scrutiny. Critical housing scholarship has long highlighted this is not a relationship of equals (Madden & Marcuse, Citation2016; McKee et al., Citation2020; Rex & Moore, Citation1967), especially in contexts where regulation is limited. This is not to say that landlords have complete freedom, since there are significant factors beyond the control of landlords, such as the policy framework, the welfare system, and the wider housing market. Indeed, landlords may feel their room for manoeuvre to be significantly constrained in the highly financialised housing systems characterised by light regulation. Nor does it imply that landlord behaviour is the only factor that impacts on tenants’ ability to feel at home, since such outcomes are always the result of complex, multi-factor causal processes. Nevertheless, there are a range of ways in which landlords can have direct and indirect impacts on tenants’ ability to make a home in the PRS, which are important to understand.

Internationally, governments have recognised the need to raise standards and improve professionalism in the sector (Marsh & Gibb, Citation2019; Whitehead et al., Citation2012), whilst recognising that legislation is only part of the solution to improving conditions for private renters and ensuring professional management of properties. In the UK, for example, lack of knowledge by landlords of their responsibilities has been identified as a key problem in ensuring tenants are provided with good housing experiences (DCLG, Citation2009; Rugg & Rhodes, Citation2008). Education and the sharing of good practice have therefore been highlighted as vital to ongoing efforts to raise standards and improve the professionalism of landlord/agent practice.

To support evidence-based best practice in the management of private rented housing, this paper reviews the existing evidence around the impacts of landlord behaviour on tenants’ ability to make a home in the PRS. The research questions that we set out to address are:

What forms of landlord behaviour have an impact on PRS tenants’ ability to make a home in their tenancy?

How can landlords and letting agents play a positive role in helping their tenants create a home in their rented property?

Across both questions, we also explore whether particular groups of tenants are affected in different ways or to different degrees. The next section outlines our methodological approach in more detail. This is followed by a discussion of our key findings and then the conclusions arising from the review.

Methodology

Our study is a rapid systematic review of the literature, employing the rigorous search approach of more comprehensive systematic reviews, but placing limits on the range of included literature to fit the available time and resource (Featherstone et al., Citation2015). Based on our research questions, our review aimed to deliver both configurative theory generation in the form of synthesising the different forms of landlord behaviour which have been evidenced to impact on tenants’ ability to feel at home, and also aggregative theory exploration in the form of analysis of the degree of impact for different tenants (Gough et al., Citation2012), so far as such evidence is available in the literature. Despite the rapid nature of our review, the systematic approach delivers a rigorous and structured synthesis of the available evidence, providing a more robust basis for policy and practice development than the scoping or narrative review techniques often employed with primarily qualitative data (Wallace et al., Citation2006).

Search strategy

We began our review by conducting a systematic search of the two largest bibliographic databases, Scopus and Web of Science. Three search strings were developed to reflect the focus of the review, drawing on team expertise and suggestions from experts in the field:

Context – terms related to the private rented sector

Intervention – terms related to forms of landlord behaviour, such as repairs or communication with tenants

Outcome – terms related to home and home-making

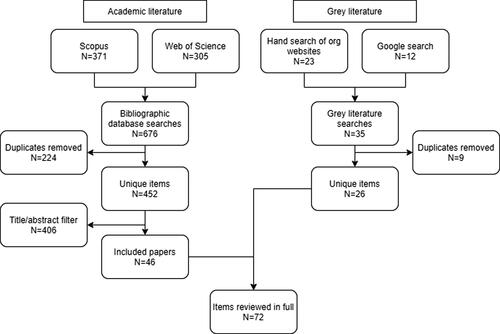

Each string was piloted individually and then refined to improve sensitivity and specificity. The three strings were then combined and refined further through an iterative process of adding terms and examining additional returned items for novelty and relevance, before the final searches of each database were undertaken (see appendix for full search terms). Inclusion criteria were applied to these searches, as set out in .

Table 1. Inclusion criteria.

Following removal of duplicates, papers were filtered for relevance by two reviewers based on title and abstract. The filtered list was reviewed by all team members to check whether any expected items were missing, but no further papers were identified at this stage.

The search of academic databases was augmented by two parallel searches of the grey literature. Firstly, hand searches were made of the websites of relevant organisations, identified based on expert knowledge within the review team. Secondly, a simplified version of the search strings was utilised for a Google search, with the first 50 returns being checked to identify relevant reports. Grey literature was limited to post-2000, English language items relating to OECD countries. Since grey literature is not formally peer-reviewed, only full research reports were considered (i.e., excluding briefing papers and blog posts). Items were filtered for relevance based on title and executive summary.

sets out the number of items at each stage of the search process. A total of 72 items were included in the final review, representing 66 unique studies (some studies reported in more than one publication). The complete list of studies reviewed is available here.

Included studies

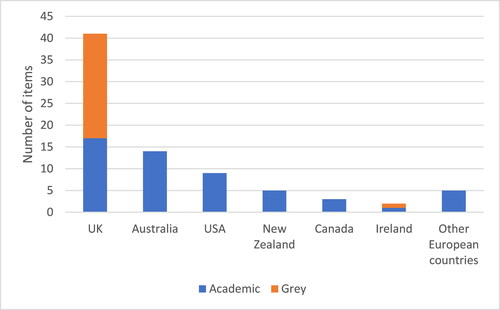

Unsurprisingly, the set of included studies is dominated by research focused on the UK and, more broadly, from English-speaking countries (). The UK focus is inevitably influenced by the grey literature, which was drawn primarily from organisations focused on the UK context. This is partly due to the review team’s greater knowledge of relevant UK organisations, but also seems to indicate a greater focus on issues of landlord behaviour in this country, reflected in the larger number of academic sources focused on the UK. The wider concentration of studies from the English-speaking world is likely to be partly due to the exclusion of papers not written in English, but may also reflect the particular growth of, and issues related to, the PRS in the more liberal welfare regimes of anglophone countries with lightly regulated markets. Notably, although we included all OECD countries in our search, with the intention of providing some comparison between lightly and heavily regulated markets, the evidence from the latter was minimal – just four papers. It is not possible to determine whether this is a reflection of a lower relevance of landlord behaviour, or a difference in research focus outside the context of lightly regulated markets, or simply an artefact of excluding studies published in languages other than English. Further, multi-lingual, studies may be useful in clarifying this issue.

Figure 2. Country focus of included studies.

Note that some studies involve more than one country, so the figures in this chart add to 79 rather than 72.

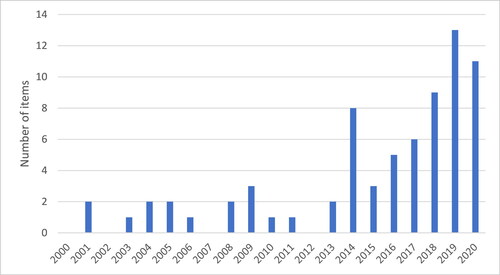

Although our search strategy looked for items published since the turn of the century, the included studies are heavily clustered in more recent years (). This likely reflects the increasing concern about ‘generation rent’ and issues of home-making in the PRS as the sector has grown and more households are spending longer periods in PRS tenancies.

Data extraction and synthesis

Each of the selected studies was read in depth by a member of the team and data was extracted into a spreadsheet. Data extraction focused on evidence relating to forms of landlord behaviour, impacts on tenants regarding their ability to make a home within their tenancy, and contextual factors that may have affected these impacts. For landlord behaviours and impacts on tenants, a checklist of options was developed based on team expertise. This was tested on a subset of studies and extra items added as required. Contextual factors and the main findings of each study were summarised and assessed descriptively. Using the checklist of landlord behaviours as a framework, the data from the spreadsheet was then coded, focusing on the details of landlord actions, the impacts on tenants and the contextual factors which played a role.

Limitations

Given the relatively short timescale and limited resources available for this review, we employed parameters for our search which may have excluded some relevant literature. A search including publications in other languages, for example, might provide more evidence of landlord behaviours in other types of rental markets. However, we believe that our search is sufficiently comprehensive to provide valuable conclusions at least with regards to lightly regulated private rental markets.

Our focus on landlord behaviour means that we have not considered in any depth other factors which may have an impact on tenants’ ability to make a home in the PRS, such as policy frameworks and market conditions. However, since these have been covered in other reviews (Easthope, Citation2014; Soaita et al., Citation2020), our focus on landlord behaviour aims to provide a complementary contribution to this existing literature. It also addresses a significant gap in terms of our understanding of the role of landlords specifically.

Findings

The evidence we reviewed was split into three broad categories of landlord/agent behaviour: (1) investment in the condition of the property, including energy efficiency measures, repairs and maintenance; (2) the selection process of tenants and the extent to which tenants can personalise the property; and (3) the ways in which landlords/agents interact with tenants, including situations in which tenants may be struggling with the rent or other aspects of their life.

Within each area, the evidence demonstrates that the behaviour of landlords and letting agents can impact on tenants’ ability to feel at home in positive or negative ways. Importantly, there is strong evidence that tenants put substantial effort into making a home in even the most challenging circumstances (Barratt & Green, Citation2017; Fozdar & Hartley, Citation2014) and it is important to bear in mind that landlord behaviour is only one factor which may influence home-making. Nevertheless, the overall picture from the evidence reviewed is not merely that supportive actions by landlords/agents can facilitate this process, but also that some aspects are necessary conditions for tenants to feel at home.

Property condition

The evidence suggests that there are four inter-related aspects of landlord/agent behaviour regarding property condition which affect the processes of home-making in PRS tenancies.

Investment

Landlord/agent investment in property quality affects different aspects of home-making. Most obviously, a lack of investment in the basic property standard erodes the sense of comfort and relaxation which is central to the experience of home (Hulse & Saugeres, Citation2008; Soaita & McKee, Citation2019). This lack of comfort within the property can lead to negative effects on mental health (Bachelder et al., Citation2016; Marquez et al., Citation2019) and, in some instances, to direct physical health impacts such as respiratory problems where there is damp or mould (Bachelder et al., Citation2016; Grineski & Hernández, Citation2010) and injuries due to safety issues (Hulse & Saugeres, Citation2008). Poor property condition can also have effects beyond comfort, impacting on tenants’ ability to build or maintain social status and social relationships through mechanisms related to shame and stigma (Garnham & Rolfe, Citation2019a; Soaita & McKee, Citation2019).

Notably, whilst much of the research focuses on the negative impacts of lack of investment and poor property quality, there is also evidence of the opposite process. Where landlords/agents invest in the standard of décor and physical fabric of their properties, this can facilitate the home-making process, generating positive health and wellbeing benefits for tenants (Garnham & Rolfe, Citation2019a). This is particularly true for those tenants who have experienced poor property quality in previous PRS tenancies.

In considering investment in the property, there are obviously issues regarding the financial implications for landlords as well as the impacts on tenants. There is some evidence that landlords/agents are not incentivised to invest in improving the condition of their properties, especially in high-demand markets where rents are not strongly linked to quality (Crook & Hughes, Citation2001; London Assembly, Citation2013). Notably, however, more recent evidence indicates increasing investment by landlords/agents in property quality (Miu & Hawkes, Citation2020; Rugg & Rhodes, Citation2018), which is a positive trend.

Energy efficiency

Closely related to overall investment in property condition is the more specific issue of energy efficiency, delivered through investment in efficient heating systems, draught-proofing and insulation. The impacts of poor energy efficiency on tenants’ ability to make a home in their tenancy are twofold. Firstly, there are direct effects on basic comfort, particularly during cold weather. Properties which are difficult to heat undermine tenants’ comfort and therefore undermine their ability to relax and feel at home (Ambrose, Citation2015; Ambrose & McCarthy, Citation2019; Ioannis et al., Citation2020; McCarthy et al., Citation2016). Secondly, where tenants struggle to keep the property warm, there are inevitably implications for fuel costs. Particularly for those on low incomes, this can lead to fuel poverty and financial stress, making the property feel like a burden rather than a haven (Ambrose, Citation2015; Ambrose & McCarthy, Citation2019; Bouzarovski & Cauvain, Citation2016; Let Down in Wales, Citation2014a).

Again, there is evidence that landlords/agents view investment in energy efficiency as too costly and unlikely to produce a return in terms of higher rents (Hope & Booth, Citation2014; Simcock, Citation2018a), with investment on aesthetic aspects of the property seen as more likely to appeal to tenants than the long-term, hidden aspect of energy efficiency (Ambrose & McCarthy, Citation2019). However, recent research also suggests possible shifts in these metrics, with increased landlord/agent investment driven by a stronger interest in energy efficiency amongst tenants and landlords/agents for personal and global reasons (Ambrose & McCarthy, Citation2019; Miu & Hawkes, Citation2020).

Responsive repairs

Alongside the basic condition of the property, tenants’ ability to feel at home is significantly impacted by their experience of requesting repairs and the response they receive from landlords/agents. Positive landlord/agent responses to requests and quick repairs improve comfort and, perhaps more importantly, give tenants a sense of control which helps them to feel at home, generating health and wellbeing benefits (Garnham & Rolfe, Citation2019a). Moreover, this same study notes that by responding positively to repairs requests, landlords/agents may be able to identify situations in which such requests are an indicator of wider issues for tenants (e.g., health, income), which can be valuable early warnings about potential tenancy difficulties.

However, most studies evidence less positive experiences. Repairs being done late, not at all, or to a poor standard exacerbate the property condition issues outlined above, undermining tenants’ ability to feel comfortable and make a home (Bachelder et al., Citation2016; Grineski & Hernández, Citation2010; Hulse & Saugeres, Citation2008). Alongside these issues related to the repairs themselves, the evidence points to substantial impacts arising from the interactions between tenants and landlords/agents regarding repairs requests. Where tenants receive a negative or conflictual response to requests, this creates stress and often additional fear regarding the possibility of ‘retaliatory’ evictions or rent rises. These effects substantially undermine tenants’ ability to feel secure and at home (Byrne & McArdle, Citation2020; Grineski & Hernández, Citation2010). Moreover, in such situations, tenants may avoid requesting repairs and may even leave the tenancy (Bachelder et al., Citation2016; Byrne & McArdle, Citation2020; Chisholm et al., Citation2017, Citation2020; Easthope, Citation2014; Grineski & Hernández, Citation2010). In turn, these behaviours affect landlords through tenancy terminations and potentially deteriorating property condition, where they are not made aware of problems.

Particularly affected groups

Some groups of tenants are especially vulnerable to difficulties in the home-making process due to issues related to property condition. Unsurprisingly, there is consistent evidence that low-income tenants are more likely to experience problems related to lack of investment, poor energy efficiency and repairs, since their financial constraints inevitably limit the range of properties available to them (Bachelder et al., Citation2016; Barratt & Green, Citation2017; Grineski & Hernández, Citation2010; Hulse & Saugeres, Citation2008; JRF, Citation2017; London Assembly, Citation2013; Mallinson, Citation2019; Marquez et al., Citation2019; Rugg & Rhodes, Citation2018; Smith et al., Citation2014; Spencer et al., Citation2020). This lack of market choice can lead to repeated moves in an attempt to secure better quality housing (Bachelder et al., Citation2016; Desmond et al., Citation2015), whilst for those with particular concerns about contact with authorities, such as migrant groups, there may be a preference for the alternative strategy of enduring poor housing conditions without complaint (Grineski & Hernández, Citation2010). Either strategy creates barriers to home-making and generates stress.

Beyond this central finding the sources point to specific groups, often within this larger category of low-income households, who are particularly affected. Importantly, this needs to be considered within the wider context of an expanding PRS, where a wider diversity of tenants spend longer periods (Rugg & Rhodes, Citation2018; Shelter Cymru, Citation2014).

As larger numbers of older tenants are entering or remaining in the PRS, there is evidence of particular difficulties arising from property condition issues, since older people are more likely to have pre-existing health conditions and may be more vulnerable to cold indoor temperatures (Bates et al., Citation2019; Citation2020; McKee & Soaita, Citation2019). At the other end of the age spectrum, young tenants can experience specific challenges of disempowerment with issues related to repairs, arising from the power dynamic with landlords/agents, who are generally older (Lister, Citation2004a, Citation2004b, Citation2006).

For disabled people, the limited level of accessibility in the PRS and landlords’ reluctance to invest in permanent adaptations for temporary tenants can exacerbate issues with feeling comfortable and secure in their property (Hulse & Saugeres, Citation2008). Again, this issue is likely to increase as the number of tenants remaining in the PRS into older age rises over time (McKee & Soaita, Citation2019).

Finally, the number of families renting privately is also increasing. There is evidence that the constrained property choice encountered by households with children can exacerbate property condition issues (Shelter Cymru, Citation2014; Walsh, Citation2019).

Selecting tenants and setting boundaries within the tenancy

The evidence further highlights three important features of landlord/agent behaviour relating to tenant selection and what tenants are allowed to do within their tenancy which can impact on tenants’ home-making in the PRS.

Discrimination

Tenants’ concerns of discrimination within the tenancy selection process are commonly highlighted as barriers to accessing adequate housing across the PRS (Byrne & McArdle, Citation2020; McKee & Soaita, Citation2018). Groups of tenants most affected by this include those in receipt of social security benefits (JRF, Citation2017; Robertson et al., Citation2014; Rugg & Rhodes, Citation2008; Simcock, Citation2018b; Simcock & Kaehne, Citation2019), refugees and immigrants (Fozdar & Hartley, Citation2014; Mykkanen & Simcock, Citation2018), tenants with pets (Graham & Rock, Citation2019; O’Reilly-Jones, Citation2019; Power, Citation2017; Rook, Citation2018; Walsh, Citation2019), disabled tenants (Verhaeghe et al., Citation2016) and younger tenants (Bate, Citation2020; Lister, Citation2004b; Pattison & Reeve, Citation2017).

Tenants in receipt of social security benefits find it particularly difficult to access suitable housing due to a perceived unwillingness (Robertson et al., Citation2014) or reluctance from landlords/agents to let to benefit claimants (JRF, Citation2017; Pattison & Reeve, Citation2017; Rugg & Rhodes, Citation2008; Simcock, Citation2018b; Simcock & Kaehne, Citation2019). Evidence suggests that landlords/agents may avoid renting to benefit claimants due to rent arrears issues with previous tenants (Simcock, Citation2018b; Simcock & Kaehne, Citation2019). A key related issue is the gap between actual rents and the level of rent covered by social security benefits, with tenants often struggling to plug the gap, affecting their access to housing and cause financial distress (JRF, Citation2017; Simcock & Kaehne, Citation2019). However, discrimination in letting can also be generated by perceptions, rather than direct experience of financial risk on the part of landlords (Simcock & Kaehne, Citation2019). Nevertheless, some evidence also highlights positive impacts from landlords/agents signposting tenants to support services and understanding the need for patience in resolving benefits issues (Garnham & Rolfe, Citation2019a).

A second group of tenants who face difficulties in accessing adequate housing in the PRS are refugees and immigrants. In a UK-based study, 44% of private landlords were less willing to let to tenants without a British passport (Mykkanen & Simcock, Citation2018). Similarly, a study in Western Australia found that tenants with refugee status reported experiences of discrimination in obtaining private rental housing, especially those with larger families (Fozdar & Hartley, Citation2014). The barriers facing migrants and refugees have long been documented in the housing studies literature as a pernicious form of exclusion (Mckee et al., Citation2021; Rex & Moore, Citation1967). In broader terms, the issues encountered by migrants and benefit claimants highlight the interactions with PRS regulations that increase landlord risks and responsibility for tenant behaviour, which tend to generate more discriminatory approaches to selection, and potentially surveillance and harassment during tenancies (Greif, Citation2018).

For younger tenants, perceived aspects of discriminatory practice arise in the relationships and interactions that they have with their landlords. Being perceived as ‘children’ (Lister, Citation2004a) and ‘less responsible tenants’ (Bate, Citation2020) impacts on younger tenants’ sense of control within their tenancy, affecting their wellbeing . Although landlords’ intentions may be to encourage, support and guide younger tenants’ behaviours, tenants can view this as ‘unfair’ and ‘over-controlling’ (Lister, Citation2004a). The evidence further suggests that landlords are more reluctant to let to younger people who are claiming benefits due to concerns about managing the accommodation and financial loss (Pattison & Reeve, Citation2017).

Whilst there is relatively little literature regarding disabled tenants, there is evidence to suggest that landlords and letting agents discriminate against visually impaired applicants in tenant selection (Verhaeghe et al., Citation2016).

Pets

For many tenants, the ‘human-companion animal relationship’ they have with their pets is fundamental to their ability to make a home in the PRS (Rook, Citation2018; Soaita & McKee, Citation2019). Yet, ‘pet-friendly’ tenancies are difficult to find in the PRS and tenants who own pets are another group who face significant challenges in accessing private rental accommodation (Bate, Citation2020; Carlisle-Frank et al., Citation2005; Graham & Rock, Citation2019; O’Reilly-Jones, Citation2019; Power, Citation2017). Moreover, these issues are exacerbated when combined with other forms of discrimination, with African-American pet owners facing greater challenges than white pet owners (Rose et al., Citation2020). In comparison to non-pet owners, pet-owners can take up to seven times longer to rent a home (O’Reilly-Jones, Citation2019; Rook, Citation2018). Low property availability limits choice and can lead to tenants accepting rental properties in poor condition and in less desirable and/or more expensive areas (Carlisle-Frank et al., Citation2005; Graham et al., Citation2018; Graham & Rock, Citation2019; O’Reilly-Jones, Citation2019; Power, Citation2017; Rook, Citation2018; Walsh, Citation2019), which can impact on the sense of control and autonomy that tenants have over their housing and their ability to make a home (Chisholm et al., Citation2017; Graham et al., Citation2018; Power, Citation2017). Additionally, tenants who choose not to declare their pets to their landlords worry about their housing security due to the risk of eviction (Power, Citation2017). There is some evidence to suggest that hiding pets from landlords across successive tenancies can impact on tenants’ wellbeing (Soaita & McKee, Citation2019), or difficult decisions between having to give up their pet or move out and risk becoming homeless (O’Reilly-Jones, Citation2019; Rook, Citation2018).

Whilst much of the research focuses on the negative aspects of rental for tenants who own pets, there is some evidence that landlords do see the value of ‘pet-friendly’ tenancies in creating stability and length of tenure (Graham et al., Citation2018; Shelter, Citation2016), as well as data to show these effects in practice (Carlisle-Frank et al., Citation2005). Pre-tenancy meetings with pets, professional assessments and pet references can assist landlords/agents to make decisions regarding potential tenants with pets (Graham et al., Citation2018).

Personalisation

The evidence further indicates that some tenants find it easier to feel at home when they are allowed to decorate and personalise their rented homes. There is strong evidence that tenants strive to ‘make a home’ through personalisation of ‘space’ and use of objects which symbolise aspects of their self-identity (Soaita & McKee, Citation2019; Walsh, Citation2019). Allowing personalisation of a rented home offers tenants more stability (Shelter, Citation2016), security of tenure (Easthope, Citation2014) and increases the likelihood that they will look after the property (Hiscock et al., Citation2001). However, where personalisation of the home is not permitted, tenants lack autonomy and control, impacting on their ability to feel safe, secure and settled in their rented home (Chisholm et al., Citation2017; Easthope, Citation2014; McKee et al., Citation2020). Insecurity of tenure and financial constraints also affect home-making practices, since tenants concerned about having to move on or worried about finances may be unable to personalise their properties (Easthope, Citation2014; Garnham & Rolfe, Citation2019a; Soaita & McKee, Citation2019).

Landlord-tenant relationships

The relationship with landlords and letting agents is central to tenants’ ability to make a home in the PRS. The literature highlights however that this relationship is by no means an equal one, with properties often regarded as ‘assets’ as opposed to renters’ ‘homes’ (Madden & Marcuse, Citation2016; McKee et al., Citation2020). The dynamic of this relationship featured as an overarching theme across the evidence base which affected many of the aspects already discussed. Four key characteristics of landlord/agent behaviour are important.

Engagement

The way in which landlords/agents engage and communicate with their tenants can positively or negatively influence tenants’ experiences and outcomes in the PRS. Examples of poor engagement include not treating tenants as responsible in relation to property maintenance (Holdsworth, Citation2011), not offering support to tenants who may be experiencing difficulties (Smith et al., Citation2014) and employing controlling or surveillance style strategies to control and regulate tenants and their use of property (Lister, Citation2004a; Mallinson, Citation2019). Power differentials between tenants and landlords/agents can undermine tenants’ sense of control over their home environment, with the ultimate risk of tenancies breaking down (Bachelder et al., Citation2016; Byrne & McArdle, Citation2020; Let Down in Wales, 2014b; Lister, Citation2004a; Mallinson, Citation2019). Notably, these power differentials can create a tension for tenants between quiet acquiescence and active reporting of property issues, as they feel obliged to perform elements of ‘stewardship of home’ in order to be seen as a ‘good tenant’ by their landlord (Power & Gillon, Citation2020).

However, the evidence also highlights examples of good practice in relation to engagement and communication with tenants. Responding to tenant concerns and requests for repairs in a consistent and timely way supports the relationship (Lister, Citation2004a), whilst feeling respected and that their individual needs are understood by landlords/agents is also important to tenants (Garnham & Rolfe, Citation2019a). Where landlords/agents approach tenants in this way, it offers tenants greater autonomy and control, making it more likely that they will stay for the long term (Lister, Citation2004a).

Inspections

Tenants experience problems when landlords/agents access the property without their permission or make unannounced inspections, as this generates feelings of insecurity and lack of control (Let Down in Wales, 2014 b; Lister, Citation2004a; Shelter Cymru, Citation2014; Soaita & McKee, Citation2019). By contrast, where inspections are done sensitively, recognising tenants’ rights and cultural needs, tenants are more able to feel relaxed and safe, and hence to make a home in their tenancy (Soaita & McKee, Citation2019).

Rent changes and flexibility

Significant increases to rents, especially in the current context where the pandemic has exacerbated employment and financial difficulties, can further impact on tenants’ home-making practices. Sharp or unexpected rent rises can lead to tenants’ having to move frequently, in some instances becoming homeless (Holdsworth, Citation2011; Hulse & Saugeres, Citation2008). Moreover, there is evidence of landlord harassment of tenants in situations where regulation precludes significant rent increases within the tenancy, aiming to ‘encourage’ long-standing tenants to move on (Izuhara & Heywood, Citation2003). Whilst recognising the financial pressures on landlords/agents, the evidence suggests that flexibility around arrears repayment can sometimes ensure greater stability of long-term rental income (Garnham & Rolfe, Citation2019a). Notably, we uncovered no evidence of rent reduction, although it would be interesting to explore whether landlords have considered this in the context of the pandemic.

Tenancy length

The length of tenure offered also affects relationships between tenants and landlords/agents, with implications for home-making. Long-term tenancies support the development of trust and encourage both parties to maintain relationships and resolve difficulties (Holdsworth, Citation2011; Lister, Citation2004a).

By contrast, short-term tenancies and risks relating to ‘no fault evictions’ undermine housing security and prevent effective home-making (Easthope, Citation2014; Hiscock et al., Citation2001; Holdsworth, Citation2011; Hulse & Saugeres, Citation2008; Mallinson, Citation2019; McKee & Soaita, Citation2019; Robertson et al., Citation2014; Rugg & Rhodes, Citation2008; Shelter, Citation2016; Smith et al., Citation2014; Walsh, Citation2019). These insecurities impact on tenants’ connections with their local communities, which is especially difficult for families with children in school (Chisholm et al., Citation2017; Holdsworth, Citation2011; Hulse & Saugeres, Citation2008; McKee & Soaita, Citation2019; Shelter, Citation2016; Vobecká et al., Citation2014). Tenants’ lack of control over housing, frequent moves, and related financial costs can create stress and anxiety, impacting on physical and mental health, as well as parenting capacity (Hulse & Saugeres, Citation2008; JRF, Citation2017; McKee et al., Citation2020; McKee & Soaita, Citation2018; Morris et al., Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2014).

The evidence strongly suggests that increasing the security of tenure for PRS tenants through long-term or open-ended tenancies, supports tenants’ ability to make a home in the PRS (Hiscock et al., Citation2001; Shelter, Citation2005; Walsh, Citation2019). Indeed, in some national contexts (e.g., Scotland), governments have intervened to address this concern. Nonetheless, landlords/agents can face challenges themselves in relation to offering longer tenancies. In the UK for example, these include the implications of time and resources required to regain possession of properties (Simcock, Citation2018c), and lenders placing restrictions on ‘buy-to-let’ mortgages which limit tenancy length (London Assembly, Citation2013).

Conclusion

The ability of tenants to make a home in the PRS is increasingly important, given the growth and diversification of the sector across many countries, coupled with the increased time spent at home due to COVID-19 restrictions and the possibility that some elements of working from home seem likely to persist. There have been multiple reviews of ‘home’ within the inter-disciplinary literature over the last 35 years, demonstrating the importance of home-making for wellbeing, but with little focus on the role of landlords/agents. Our paper seeks to make a positive contribution here, drawing out lessons to be learned across different national contexts. Whilst we focus particularly on countries with lightly regulated PRS markets where the evidence appears to be strongest, we contend that our findings will have relevance to a much wider range of contexts, albeit that tighter regulatory frameworks may limit the role of landlord behaviour in influencing tenants’ ability to make a home.

Our review of the international evidence suggests three broad categories of landlord and letting agent behaviour that can make a real difference. Firstly, we draw attention to the condition of the property and the pivotal role of landlord investment and being responsive to repairs. The quality of the property has a significant impact on tenants’ sense of comfort, relaxation, and health and wellbeing. It also has knock-on effects for status, stigma and tenants’ ability to maintain social relationships. For some tenants, difficulties in having repairs addressed can cause them to leave the property, whilst others worry about highlighting problems for fear of a retaliatory eviction. Conversely, involving tenants in the standard of décor and upgrading of the property can bring positive benefits, with growing interest in energy efficiency measures noted in the literature. At present, however, there is little incentive in lightly regulated markets for landlords to invest in their properties, with many continuing to view it as an ‘asset’ as opposed to someone’s ‘home’.

A second key area relates to selecting tenants and setting boundaries within the tenancy in terms of what tenants are allowed to do. Discrimination in the selection process remains a longstanding theme in the literature, with low-income households, refugee and migrant groups and young people being particularly affected. Keeping pets has also emerged as a key issue, with governments becoming increasingly interested in this aspect of the tenancy agreement (see for example, the pet-friendly changes to the model tenancy (MHCLG, Citation2021)). Perhaps not surprisingly, tenants feel most at home when they can personalise, decorate and make the property feel like their own. Having autonomy and control, which also includes security of tenure, is a recurring theme in the literature. Whilst some governments (e.g., Scottish Government) have sought to legislate to ensure longer and/or more open-ended tenancies they nonetheless remain on quite different trajectories in terms of regulation, which has implications for tenants’ rights and experiences of private renting.

Thirdly and finally, we identify the landlord-tenant relationship as central to how renters experience their home. The literature has long-highlighted this is not a relationship of equals, especially in high-demand rental markets where landlords can afford to be more selective. But there are some things landlords (and agents) can do to support their tenants: sensitive inspections, clear and timely communication, and flexibility around arrears repayments to highlight a few. Ultimately, however, this remains a relationship governed by the market, which leaves low-income and marginalised groups – who typically have more constrained ‘choices’ – vulnerable to unscrupulous and poor practice.

Changes to these aspects of landlord and letting agent behaviour have the potential to radically improve the experience of ‘home’ for PRS tenants, but the challenge lies in making them happen. Especially in lightly regulated markets (such as the Anglophone countries), where the PRS is dominated by small-scale, part-time landlords, professionalising the sector and influencing landlord behaviour is far from simple. Attempting to incorporate a legal conception of ‘home’ (Fox, Citation2002) into regulatory frameworks may be beneficial, but, crucially, many of the behaviours we have highlighted may not be amenable to legislative influence, would cost little and may arguably benefit landlords (and agents) through tenancy sustainment and early identification of problems with the property. Delivering change therefore needs to involve a mix of regulation, education and sharing good practice, to motivate landlords and enable tenants to make a home in the PRS. Since our study focuses on the impacts, rather than causes, of landlord behaviour, there is a need for further research into the factors influencing landlords’ treatment of tenants and the potential policy and practice instruments which would be effective in different national contexts. The role of renters’ movements in driving such change in landlord behaviour and related regulation would also be an interesting area for study, building on this review. In addition, there would be value in research, possibly including multi-lingual reviews, to elucidate the role of landlord behaviours in different markets and regulatory contexts.

Disclosure statement

None of the authors have any financial or non-financial competing interests to declare.

Correction statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ambrose, A. (2015). Improving energy efficiency in private rented housing: Why don’t landlords act? Indoor and Built Environment, 24(7), 913–924. https://doi.org/10.1177/1420326X15598821

- Ambrose, A., & McCarthy, L. (2019). Taming the ‘masculine pioneers’? Changing attitudes towards energy efficiency amongst private landlords and tenants in New Zealand: A case study of Dunedin. Energy Policy, 126, 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2018.11.018

- Bachelder, A. E., Stewart, M. K., Felix, H. C., & Sealy, N. (2016). Health complaints associated with poor rental housing conditions in Arkansas: The only state without a landlord’s implied warranty of habitability. Frontiers in Public Health, 4, 263. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2016.00263

- Barratt, C., & Green, G. (2017). Making a house in multiple occupation a home: Using visual ethnography to explore issues of identity and well-being in the experience of creating a home amongst HMO tenants. Sociological Research Online, 22(1), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.4219

- Bate, B. (2020). Rental security and the property manager in a tenant’s search for a private rental property. Housing Studies, 35(4), 589–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1621271

- Bates, L., Kearns, R., Coleman, T., & Wiles, J. (2020). You can’t put your roots down’: Housing pathways, rental tenure and precarity in older age. Housing Studies, 35(8), 1442–1467. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1673323

- Bates, L., Wiles, J., Kearns, R., & Coleman, T. (2019). Precariously placed: Home, housing and wellbeing for older renters. Health Place, 58, 102152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102152

- Blunt, A., & Dowling, R. (2006). Home. Routledge.

- Bouzarovski, S., & Cauvain, J. (2016). Spaces of exception: governing fuel poverty in England’s multiple occupancy housing sector. Space and Polity, 20(3), 310–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2016.1228194

- Byrne, M. (2020). Stay home: Reflections on the meaning of home and the Covid-19 pandemic. Irish Journal of Sociology, 28(3), 351–355. https://doi.org/10.1177/0791603520941423

- Byrne, M., & McArdle, R. (2020). Security and agency in the Irish private rental sector. Threshold.

- Carlisle-Frank, P., Frank, J. M., & Nielsen, L. (2005). Companion animal renters and pet-friendly housing in the US. Anthrozoös, 18(1), 59–77. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279305785594270

- Chisholm, E., Howden-Chapman, P., & Fougere, G. (2017). Renting in New Zealand: Perspectives from tenant advocates. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online, 12(1), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2016.1272471

- Chisholm, E., Howden-Chapman, P., & Fougere, G. (2020). Tenants’ responses to substandard housing: Hidden and invisible power and the failure of rental housing regulation. Housing Theory & Society, 37(2), 139–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2018.1538019

- Clapham, D. (2005). The meaning of housing: A pathways approach. Policy Press.

- Clapham, D. (2011). The embodied use of the material home: An affordance approach. Housing, Theory and Society, 28(4), 360–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2011.564444

- Crook, A. D. H., & Hughes, J. E. T. (2001). Market signals and disrepair in privately rented housing. Journal of Property Research, 18(1), 21–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/09599910010014129

- DCLG. (2009). The private rented sector: Professionalism and quality: The government response to the Rugg review consultation. DCLG.

- Desmond, M., Gershenson, C., & Kiviat, B. (2015). Forced relocation and residential instability among urban renters. Social Service Review, 89(2), 227–262. https://doi.org/10.1086/681091

- Dovey, K. (1985). Home and homelessness. In I. Altman & C. Werner (Eds.), Home environments (pp. 33–64). Plenum Press.

- Dupuis, A., & Thorns, D. (1998). Home, home ownership and the search for ontological security. The Sociological Review, 46(1), 24–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.00088

- Easthope, H. (2014). Making a rental property home. Housing Studies, 29(5), 579–596. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.873115

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Polity Press.

- Featherstone, R. M., Dryden, D. M., Foisy, M., Guise, J.-M., Mitchell, M. D., Paynter, R. A., Robinson, K. A., Umscheid, C. A., & Hartling, L. (2015). Advancing knowledge of rapid reviews: An analysis of results, conclusions and recommendations from published review articles examining rapid reviews. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-015-0040-4

- Fox, L. (2002). The meaning of home: A chimerical concept or a legal challenge? Journal of Law and Society, 29(4), 580–610. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6478.00234

- Fozdar, F., & Hartley, L. (2014). Housing and the creation of home for refugees in Western Australia. Housing, Theory and Society, 31(2), 148–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2013.830985

- Garnham, L., & Rolfe, S. (2019a). Housing as a social determinant of health: Evidence from the housing through social enterprise study. GCPH.

- Garnham, L., & Rolfe, S. (2019b). Tenant participation in the private rented sector: A review of existing evidence. CaCHE.

- Gezici Yalçın, M., & Düzen, N. E. (2021). Altered meanings of home before and during COVID-19 pandemic. Human Arenas, https://doi.org/10.1007/s42087-021-00185-3

- Gough, D., Thomas, J., & Oliver, S. (2012). Clarifying differences between review designs and methods. Systematic Reviews, 1(28). https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-1-28

- Graham, T. M., Milaney, K. J., Adams, C. L., & Rock, M. J. (2018). Pets negotiable: How do the perspectives of landlords and property managers compare with those of younger tenants with dogs? Animals, 8(3), 32. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani8030032

- Graham, T. M., & Rock, M. J. (2019). The spillover effect of a flood on pets and their people: Implications for rental housing. Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 22(3), 229–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888705.2018.1476863

- Greif, M. (2018). Regulating landlords: Unintended consequences for poor tenants. City & Community, 17(3), 658–674. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12321

- Grineski, S. E., & Hernández, A. A. (2010). Landlords, fear, and children’s respiratory health: An untold story of environmental injustice in the central city. Local Environment, 15(3), 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549830903575562

- Gurney, C. M. (2021). Dangerous liaisons? Applying the social harm perspective to the social inequality, housing and health trifecta during the Covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Housing Policy, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2021.1971033

- Hiscock, R., Kearns, A., Macintyre, S., & Ellaway, A. (2001). Ontological security and psycho-social benefits from the home: Qualitative evidence on issues of tenure. Housing, Theory and Society, 18(1-2), 50–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/140360901750424761

- Holdsworth, L. (2011). Sole voices: Experiences of non-home-owning sole mother renters. Journal of Family Studies, 17(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.5172/jfs.2011.17.1.59

- Hoolachan, J. (2020). Making home? Permitted and prohibited place-making in youth homeless accommodation. Housing Studies, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1836329

- Hoolachan, J., McKee, K., Moore, T., & Soaita, A. M. (2017). Generation rent’ and the ability to ‘settle down’: Economic and geographical variation in young people’s housing transitions. Journal of Youth Studies, 20(1), 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2016.1184241

- Hope, A. J., & Booth, A. (2014). Attitudes and behaviours of private sector landlords towards the energy efficiency of tenanted homes. Energy Policy, 75, 369–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2014.09.018

- Hulse, K., & Milligan, V. (2014). Secure occupancy: A new framework for analysing security in rental housing. Housing Studies, 29(5), 638–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.873116

- Hulse, K., & Saugeres, L. (2008). Housing insecurity and precarious living: An Australian exploration. AHURI.

- Ioannis, K., Marina, L., Vasileios, N., Margarita-Niki, A., & Joanna, R. (2020). An analysis of the determining factors of fuel poverty among students living in the private-rented sector in Europe and its impact on their well-being. Energy Sources Part B-Economics Planning and Policy, 15(2), 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/15567249.2020.1773579

- Izuhara, M., & Heywood, F. (2003). A life-time of inequality: A structural analysis of housing careers and issues facing older private tenants. Ageing and Society, 23(2), 207–224. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X02001125

- JRF. (2017). Poverty, evictions and forced moves. JRF.

- Kearns, A., Hiscock, R., Ellaway, A., & Macintyre, S. (2000). Beyond four walls’. The psycho-social benefits of home: Evidence from West Central Scotland. Housing Studies, 15(3), 387–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030050009249

- Kearns, A., Whitley, E., Bond, L., & Tannahill, C. (2012). The Residential psychosocial environment and mental wellbeing in deprived areas. International Journal of Housing Policy, 12(4), 413–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2012.711985

- Kemeny, J. (1995). From public housing to the social market: Rental policy strategies in comparative perspective. Routledge.

- Kofman, Y. B., & Garfin, D. R. (2020). Home is not always a haven: The domestic violence crisis amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 12(S1), S199–S201. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000866

- Let Down in Wales. (2014a). Letting Agents: the good, the bad and the ugly – How private tenants rent in Wales. Let Down in Wales.

- Lister, D. (2004a). Controlling letting arrangements? Landlords and surveillance in the private rented sector. Surveillance & Society, 2(4), 513–528. https://doi.org/10.24908/ss.v2i4.3361

- Lister, D. (2004b). Young people’s strategies for managing tenancy relationships in the private rented sector. Journal of Youth Studies, 7(3), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/1367626042000268944

- Lister, D. (2006). Unlawful or just awful?: Young people’s experiences of living in the private rented sector in England. Young, 14(2), 141–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/1103308806062738

- London Assembly. (2013). Rent reform: Making London’s PRS fit for purpose. Assembly.

- Madden, D., & Marcuse, P. (2016). In defence of housing. Verso Books.

- Mallett, S. (2004). Understanding home: A critical review of the literature. The Sociological Review, 52(1), 62–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2004.00442.x

- Mallinson, G. (2019). Australian housing crisis and caravan parks: The social cost of housing marginality. The International Journal of Sustainability in Economic, Social, and Cultural Context, 15(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.18848/2325-1115/CGP/v15i01/1-10

- Marquez, E., Dodge Francis, C., & Gerstenberger, S. (2019). Where I live: A qualitative analysis of renters living in poor housing. Health & Place, 58, 102143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.05.021

- Marsh, A., & Gibb, K. (2019). The private rented sector in the UK. CaCHE.

- McCarthy, L. (2018). (Re)conceptualising the boundaries between home and homelessness: the unheimlich. Housing Studies, 33(6), 960–985. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2017.1408780

- McCarthy, L., Ambrose, A., & Pinder, J. (2016). Energy (In)Efficiency: Exploring what tenants expect and endure in the private rented sector in England. Making the case for more research into the tenant’s perspective. An Evidence Review. CRESR.

- McKee, K., & Soaita, A. (2018). The frustrated housing aspirations of generation rent. CaCHE.

- McKee, K., & Soaita, A. (2019). Beyond generation rent. CaCHE.

- McKee, K., Soaita, A., & Hoolachan, J. (2020). Generation rent’ and the emotions of private renting: Self-worth, status and insecurity amongst low-income renters. Housing Studies, 35(8), 1468–1487. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1676400

- Mckee, K., Leahy, S., Tokarczyk, T., & Crawford, J. (2021). Redrawing the border through the ‘Right to Rent’: Exclusion, discrimination and hostility in the English housing market. Critical Social Policy, 41(1), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018319897043

- Mckee, K., Moore, T., Soaita, A., & Crawford, J. (2017). Generation rent’ and the fallacy of choice. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(2), 318–333. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12445

- MHCLG. (2021). New standard tenancy agreement to help renters with well behaved pets. MHCLG.

- Miu, L., & Hawkes, A. D. (2020). Private landlords and energy efficiency: Evidence for policymakers from a large-scale study in the United Kingdom. Energy Policy, 142Article, 111446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2020.111446

- Morris, A., Hulse, K., & Pawson, H. (2017). Long-term private renters: Perceptions of security and insecurity. Journal of Sociology, 53(3), 653–669. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783317707833

- Mykkanen, N., & Simcock, T. (2018). The right to rent scheme and the impact on the private rented sector. RLA.

- ONS. (2019). UK private rented sector: 2018. ONS.

- O’Reilly-Jones, K. (2019). When fido is family: How landlord-imposed pet bans restrict access to housing. Columbia Journal of Law and Social Problems, 52(3), 427–472.

- Pattison, B., & Reeve, K. (2017). Access to homes for under 35s: The impact of welfare reform on private renting. CRESR.

- Power, E. R. (2017). Renting with pets: A pathway to housing insecurity? Housing Studies, 32(3), 336–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2016.1210095

- Power, E. R., & Gillon, C. (2019). How housing tenure drives household care strategies and practices. Social and Cultural Geography, 22(7), 897–916. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2019.1667017

- Power, E. R., & Gillon, C. (2020). Performing the ‘good tenant. Housing Studies, 24, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1813260

- Rex, J., & Moore, R. (1967). Race, community and conflict: A study of sparkbrook. Open University Press.

- Rivlin, L. G., & Moore, J. (2001). Home-making: Supports and barriers to the process of home. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless, 10(4), 323–336. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011624008762

- Robertson, L., Little, S., & Simpson, S. (2014). Qualitative research to explore the implications for private sector tenants and landlords of longer term and more secure tenancy options. Scottish Government.

- Rolfe, S., Garnham, L., Godwin, J., Anderson, I., Seaman, P., & Donaldson, C. (2020). Housing as a social determinant of health and wellbeing: developing an empirically-informed realist theoretical framework. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09224-0

- Rook, D. (2018). For the love of darcie: Recognising the human–companion animal relationship in housing law and policy. Liverpool Law Review, 39(1-2), 29–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10991-018-9209-y

- Rose, D., McMillian, C., & Carter, O. (2020). Pet-friendly rental housing: Racial and spatial inequalities. Space and Culture, 120633122095653. https://doi.org/10.1177/1206331220956539

- Rugg, J., & Rhodes, D. (2008). The private rented sector: Its contribution and potential. CHP.

- Rugg, J., & Rhodes, D. (2018). The evolving PRS: its contribution and potential. CHP.

- Shelter Cymru. (2014). Fit to rent? Today’s private rented sector in Wales. Shelter Cymru.

- Shelter. (2005). The private rented sector and security of tenure. Shelter.

- Shelter. (2016). Living home standard. Shelter.

- Simcock, T. (2018a). Examining energy efficiency and electrical safety in the PRS. RLA.

- Simcock, T. (2018b). Investigating the effect of welfare reform on private renting. RLA.

- Simcock, T. (2018c). Longer term tenancies in the private rented sector. RLA.

- Simcock, T., & Kaehne, A. (2019). State of the PRS (Q1 2019) A Survey of private landlords and the impact of welfare reforms. RLA.

- Smith, M., Albanese, F., & Truder, J. (2014). A roof over my head: The final report of the sustain project. Shelter/Crisis.

- Soaita, A., & McKee, K. (2019). Assembling a ‘kind of’ home in the UK private renting sector. Geoforum, 103, 148–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.04.018

- Soaita, A., Munro, M., & McKee, K. (2020). Private renters’ housing experiences in lightly regulated markets. CaCHE.

- Spencer, R., Reeve-Lewis, B., Rugg, J., & Barata, E. (2020). Journeys in the Shadow Private Rented sector. Cambridge House.

- Stephens, M. (2020). How housing systems are changing and why: A critique of Kemeny’s theory of housing regimes. Housing, Theory and Society, 37(5), 521–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2020.1814404

- Verhaeghe, P. P., Van Der Bracht, K., & Van De Putte, B. (2016). Discrimination of tenants with a visual impairment on the housing market: Empirical evidence from correspondence tests. Disability and Health Journal, 9(2), 234–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2015.10.002

- Vobecká, J., Kostelecký, T., & Lux, M. (2014). Rental housing for young households in the Czech Republic: Perceptions, priorities and possible solutions. Czech Sociological Review, 50(3), 365–390. https://doi.org/10.13060/00380288.2014.50.3.102

- Wallace, A., Croucher, K., Bevan, M., Jackson, K., O’Malley, L., & Quilgars, D. (2006). Evidence for policy making: Some reflections on the application of systematic reviews to housing research. Housing Studies, 21(2), 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030500484935

- Walsh, E. (2019). Family-friendly tenancies in the private rented sector. Journal of Property, Planning and Environmental Law, 11(3), 230–243. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPPEL-04-2019-0020

- Whitehead, C., Monk, S., Scanlon, K., Markkanen, S., & Tang, C. (2012). The Private Rented Sector in the new century: A comparative approach. Cambridge University Press.

Appendix

Search terms

TITLE-ABS-KEY ("private rent*” OR ( rent* W/5 housing ))

AND

(TITLE-ABS-KEY (“pet” OR “companion animal” OR “security” OR “insecurity” OR “tenure” OR “fuel poverty” OR “fuel cost” OR “heating cost” OR “energy poverty” OR “energy efficiency” OR “energy cost” OR “repair” OR “maintenance” OR “décor*” OR “personalis*” OR “eviction” OR “notice to quit” OR “lease” OR “tenancy agreement” OR “deposit” OR “arrears” OR “rent collect*” OR “service charge” OR “compliance” OR “management” OR ((“landlord” OR “owner” OR “letting agen*” OR “property agen*” OR “property investor”) AND ( “engage*” OR “communic*” OR “relationship” OR “professional*” ))

AND

TITLE-ABS-KEY ( “home” OR “sanctuary” OR “haven” OR “comfort” OR “relax*” OR “social status” OR “socialis*” OR “pride” OR “family” OR “friend*” OR “autonomy” OR “control” OR “independen*” OR “ontological security”) )

AND

PUBYEAR > 1999