Abstract

The well-being of people during COVID-19 lockdowns has been a global concern. Renters, who often live in small, shared and less secure forms of housing, are potentially more vulnerable during COVID-19 and associated restrictions such as lockdowns. This paper explores the well-being of renters during COVID-19 in Australia using a survey of 15,000 renters, and 20 renters who undertook a 4-week ethnographic diary. The results found that most renters had a reduction in their mental well-being; many had increased levels of worry, anxiety, loneliness and isolation, as a result of the pandemic. More than two thirds of renters attributed their housing to declines in their mental health. The qualitative diaries revealed themes that influenced the state of well-being including: housing uncertainty and precarity, the form and quality of the living environment, and the impact on relationships. This study highlighted the importance of offering opportunities for social engagements and relationships within multiple occupancy buildings, better access to green spaces, and functional homes for work and living, as well as sleep and security. The research demonstrates a need for greater consideration required for well-being in housing policy and support, especially since the home is being used as a public health intervention.

Introduction

The global COVID-19 pandemic has had devastating physical health implications with more than five million deaths and 300 million confirmed cases (WHO, 2022). Further, the long-term health effects are largely still unknown, but a ‘long tail’ (Rayner et al., Citation2020) of illnesses has been documented (for example cardiovascular (Yelin et al., Citation2020) and neurological (Pereira, Citation2020)). Increasingly, the mental health effects of the pandemic have been highlighted, alongside their disproportionate impact on vulnerable communities (Campion et al., Citation2020; Gualano et al., Citation2020; Rossi et al., Citation2020). Steadily increasing rates of depression and anxiety related to COVID-19 have been documented across many nations (Huang & Zhao, Citation2020; Rehman et al., Citation2021; Twenge & Joiner, Citation2020). Much of this mental health effect has been attributed to the ‘dual’ health and economic nature of the pandemic and the uncertainty of what the future holds. The absence of, and then difficulties distributing, a viable vaccine has meant that limiting the spread of the virus through isolation and widespread lockdown has been a principal public health intervention in many jurisdictions (Bentley & Baker, Citation2020). These governance and response measures have driven many of the mental health effects of the pandemic. While governments have provided financial and other support, there are still concerns for the long-term impact for people’s health and well-being. Some cohorts have been more exposed to a range of impacts from COVID-19 than others. In studies from around the world, renters have been highlighted as a cohort (Manville et al., Citation2020; Phillips, Citation2020) with particular vulnerability to both economically driven exposure to COVID-19, as well as mental health effects (Bower et al., Citation2021; Stone, Citation2020; Ziffer, Citation2020). These impacts are likely to be exacerbated the longer the pandemic continues and create lasting impacts on many people.

This paper aims to explore the implications the COVID-19 pandemic had on renters in Australia, to reveal ways well-being could be enhanced through housing, and to propose future directions for housing policy. This work will contribute to the rapidly emerging evidence base on the mental well-being of renters during COVID-19. Using surveys and in-depth digital diaries, the paper explores the mental health and well-being experience of renting households during the early months of the pandemic, and discusses what this means for any extended response, and the improvement of outcomes for renters beyond the pandemic more broadly. This is important, not only in Australia where rental housing makes up an increasing percentage of the total housing stock (increasing from 28.6 per cent in 1994-95 to 33.8 per cent in 2017-18 (ABS, Citation2019)), but for other jurisdictions where rental housing is a significant percentage of overall housing stock.

The first recorded case of COVID-19 in Australia was on the 25th of January 2020 (Hunt, Citation2020) and by the 20th of March 2020 the international borders were shut to all non-residents (Morrison, Citation2020). In the first wave, cases reached almost 500 in a single day in late March (Department of Health, Citation2021), but were reduced to less than 20 cases per day by late April. The second wave began in late June 2020, with a state-wide lockdown in the State of Victoria being introduced on the 7th of July 2020 (Andrews, Citation2020), and cases reaching over 700 per day in early August (Department of Health, Citation2021). Around 90% of the cases were in the State of Victoria, where the city of Melbourne is located. Following a strict 112-day lockdown in Melbourne cases dropped from over 700 per day to zero cases on the 27th of October 2020 (BBC News, Citation2020). It was during this second wave that the research presented in this paper was undertaken.

The following section provides an overview of previous literature on housing, well-being and recent work on the implications the COVID-19 pandemic has had. This leads into the well-being theoretical framework that guided the analysis in the research methodology, as well as the details of how the research was undertaken. The survey and digital diary results are presented and then discussed, with implications for rental well-being and housing policy highlighted.

Housing, well-being and COVID-19

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development has identified several elements essential for the quality of life including health, safety, housing, income, jobs and community (OECD, Citation2020). Within academic work, housing has a well-documented significant impact on the economic and social well-being of its occupants (Baker et al., Citation2017; Berry et al., Citation2014; CABE, Citation2002; Daniel et al., Citation2019; Moore et al., Citation2017; Pevalin et al., Citation2008; Citation2017). Having housing that is affordable: provides sufficient space to avoid overcrowding; provides meaning and self-esteem; as well as providing stability and security; and can be beneficial for family well-being (Bratt, Citation2002; Clapham, Citation2010). In turn, evidence suggests that certain housing situations can have negative implications for well-being, such as having relatively small accommodation (Clapham et al., Citation2018) or having dangerous building defects unexpectedly manifest (Oswald et al., Citation2021). Rental housing has also been found to drive health and well-being through multiple and overlapping characteristics (Baker & Lester, Citation2017) such as stability (Beer et al., Citation2011), security and quality (Baker et al., Citation2017; Daniel et al., Citation2019; Telfar-Barnard et al., Citation2017). This is not always in terms of negative outcomes for renters, with some jurisdictions like Germany and Switzerland using tenure-neutral housing policies to deliver better outcomes for renters (Gilbert, Citation2016). However, housing policy has traditionally viewed housing as units of accommodation, rather than homes (Clapham, Citation2010), which is problematic for enhancing well-being through housing. The mental health and well-being drawbacks of this traditional perspective have been exposed more clearly through the COVID-19 pandemic (Bower et al., Citation2021; D’alessandro et al., Citation2020).

Globally we have relied on the conditions and quality of home to shelter against COVID-19 (Farha, Citation2020; Raynor et al., Citation2020; Rogers & Power, Citation2020). In many countries there has been a need to isolate, work, and educate from home during the pandemic, which has foregrounded issues of housing security, quality and conditions (Farha, Citation2020; Raynor et al., Citation2020; Rogers & Power, Citation2020). The pandemic has accentuated the importance for secure housing and shelter, and across social jurisdictions it has revealed pre-existing inequalities, exclusions, and deprivations (Farha, Citation2020; The Lancet, Citation2020; Yancy, Citation2020). These tensions are evident in housing systems globally, including in Australia, which has seen lockdowns of: individual buildings, such as public housing towers (Kelly et al., Citation2020); individual ‘hotspot’ suburbs, with neighbouring suburbs free from these restrictions (Grattan, Citation2020), and state-wide borders (Burridge, Citation2020). Household lockdowns have their own implications for well-being, considering that socialising and social support are important for enhancing well-being (Turner, Citation1981), and isolation and loneliness have negative impacts on both physical health and well-being (Cacioppo et al., Citation2003). Thus, it can be observed that the housing situation of individuals during times of lockdowns, virus threats and economic frailty, can have a significant bearing on both physical and mental health.

Prior to the arrival of COVID-19 in Australia, the housing system faced challenges, including homelessness, social housing supply, rental availability and affordability (for example Baker et al., Citation2019). Such existing problems have been accentuated by the economic and employment effects of COVID-19 (Coates et al., Citation2020). Renters are potentially more vulnerable considering they are overrepresented in the most affected industries during lockdowns (such as hospitality and service industries), often have lower incomes and less ability to work from home, and are at risk of eviction without government intervention. These housing challenges have direct implications for well-being with research finding a deterioration of mental health and an increase of psychological distress attributed to tenure insecurity (Bentley et al., Citation2018) and unaffordable rental housing (Mason et al., Citation2013; Pevalin et al., Citation2008). The loss of income experienced by both renters and landlords as result of the pandemic has caused significant financial uncertainty (Casey & Ralston, Citation2020). The impact of job losses on well-being goes beyond the loss of financial income (Stiglitz et al., Citation2010), with a loss of social status, workplace social life, opportunity to engage in meaningful activities, confidence and self-esteem all having implications for quality of life (Layard et al., Citation2012; McKee-Ryan et al., Citation2005). Unemployment can also have detrimental impacts on those that people care for most, such as their family members (Diener et al., Citation2003), as households experience risk of eviction or defaulting on their mortgage.

Given the association between well-being and housing there is a need to understand how renters are faring during the COVID-19 pandemic. Further, the importance of the wider built environment for well-being can be demonstrated by calls for measuring and creating enabling conditions that deliver stronger social safety nets, diminish commute times, promote relational leisure and improve housing quality (see for example Deaton, Citation2008; Diener et al., Citation2003; Easterlin, Citation2013). By understanding the state of well-being in renters both short-term solutions to COVID-19 related problems, and long-term strategies for the built environment can be considered, planned, and delivered.

Research methodology

This study triangulates two datasets collected during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. A mixed-method approach was undertaken, using online tools (Murthy, Citation2008) to capture quantitative and qualitative data while preserving COVID-19 restrictions. Overarching the study design is a well-being framework, influenced by the work of Seligman (Citation2011) that defines well-being as not only related to the absence of negative experiences such as depression, anxiety and fear, but also about having an ability to flourish (Seligman, Citation2011; Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2000). Seligman’s (Citation2011) work builds on previous well-being theory, such as the work of Ryff and Keyes who proposed a six dimension model that included: self-acceptance; personal growth; autonomy; purpose in life; positive relations with others; and environmental mastery, which is having an ability to shape the environment to meet personal needs and desires (Keyes et al., Citation2002). In Seligman’s (Citation2011) PERMA theory of well-being, he suggested there were five core pillars of well-being: positive emotion; engagement; relationships; meaning; and achievement (PERMA). In summation: positive emotion is about feeling good; engagement is being so absorbed in an activity that there is complete loss of time; relationships include all meaningful types of social relations; meaning is about having a purpose; and achievement is reaching short- and long-term goals. All five pillars contribute to an individual’s well-being. Seligman’s (Citation2011) PERMA theory was selected as it is one of the most well-established well-being theories and has been previously used on studies within the built environment (e.g. Oswald et al., Citation2021).

The first part of the analysis is based on the Australian Rental Housing Conditions Data Infrastructure (ARHCD), which is the largest systematic collection of rental conditions available in Australia (Baker et al., Citation2021). The ARHCD contains 15,000 survey responses from public and private renting households in Australia, and data were collected during July and August 2020. The dataset is representative of the renting population in all Australian States and Territories, and was collected using a combination of computer-aided telephone interviews (CATIs) and an online survey method. The survey was administered to adult household members. Approximately 72 per cent of respondents were from private rental housing, 10 per cent from social housing, and remaining respondents from other landlord types; this broadly aligns with Australian renter proportions (ABS, Citation2019). There were more female respondents (59%) than male (41%). In terms of respondent ages, 28 per cent were aged 18–29 years, 49 per cent were aged between 30 and 49 years and 22 per cent were aged over 50 years (as detailed in Baker et al., Citation2022).

The survey sought to capture renter household responses to economic hardship, eviction moratoriums, and rental deferment or reduction arrangements, as well as the broader employment, economic, and well-being effects of the pandemic. In addition to this focus, baseline data was collected to describe lease arrangements, dwelling condition and quality, affordability and demographic characteristics, finances, and health of the responding person and other members of their household. A descriptive overview of key findings is presented in the results section. The survey questions and data collected are publicly available (Baker et al., Citation2021).

The second part of the analysis focussed on the digital diaries of 20 renter household respondents. An online survey (that was separate from the ARHCD survey described above), was administered through multiple online channels, such as online renter groups, to identify and recruit digital diary participants. The survey captured demographic information, such as renter location and employment status, as well as their tenancy experiences, including whether they had requested a rent reduction or deferral. The inclusion criteria for participating were that the respondents either leased or rented a property in Australia. There were 53 tenants that completed the survey (covering all States and Territories except the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory) and 20 of these respondents (15 from Victoria, four from New South Wales and one from South Australia, all in private rental; 12 male, 8 female; with a roughly even age spread from mid-20’s to over 50) decided to continue to participate in a digital ethnographic diary of their experiences once a week for a month. The ethnographic digital diaries were also undertaken in July-August 2020 and involved photo, video, audio and/or written updates that were shared with the research team. These diary updates enabled the research team to view the home, and monitor how every-day life unfolded (Pink et al., Citation2017). An inductive thematic analysis of the various audio, video and photo diary inputs was undertaken using the software NVivo. This involved an initial coding cycle that used simple and direct codes (see Saldaña, Citation2021) across the different diary data inputs. For example, audio explanations of fear of loss of employment could be coded ‘uncertainty’, photos of walks in the park could be coded ‘exercise’, and videos showing poor building quality could be coded ‘defects’. In the second cycle of coding, a focused coding approach was used where categories were developed based on the most frequent and significant initial codes (see Charmaz, Citation2006). There were three categories that emerged that were relevant to renter well-being, based on Seligman’s (Citation2011) theoretical framework as inspiration. These three categories were: ‘uncertainty and precarity in the rental sector’, ‘form and quality of the living environment’ and ‘relationships’. These three categories, as well as the survey findings are presented in the results section below.

Results

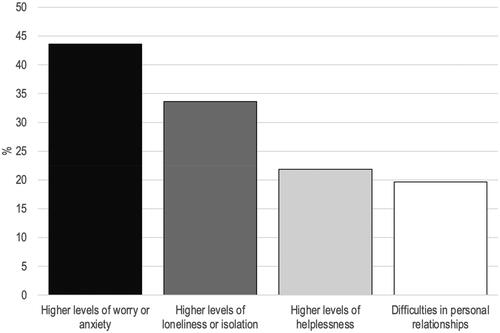

Across a series of measures, the survey results show a substantial negative mental health effect, directly attributed to the pandemic. summarises respondent assessments of the effect of the pandemic on their mental health. The figure shows that 53% of respondents had self-reported a slight or significant decrease in their mental well-being, as a result of COVID-19. This group, who experienced a decrease in mental health, were more likely to be female than male, younger, and much more likely to rent from a private landlord, than a social landlord. A further 31% of respondents reported no change in their mental health. Interestingly, a small proportion (11%) suggested that their mental health had improved. When broader population characteristics are examined, landlord type appears to have been a distinguishing factor in better well-being outcomes. Public and social renters were shown to be much more likely than renters with private landlords, to have experienced an increase in their mental well-being during the pandemic.

Figure 1. As a result of COVID-19, do you think your mental well-being has….

Note: N/A includes ‘Don’t Know’ and ‘Prefer not to say’

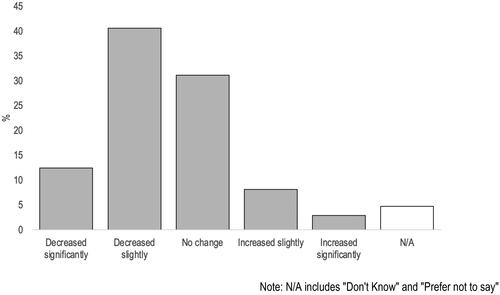

When we examine more specific well-being-related outcomes of the pandemic for renters (), we see that substantial proportions of the renter population attributed higher levels of worry or anxiety (44%), isolation and loneliness (34%), helplessness (22%), and the difficulties of personal relationships, to COVID-19.

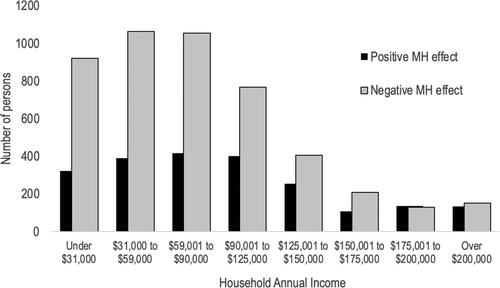

The survey also enables us to measure the degree to which people thought their recent housing circumstances had directly contributed to their current mental health. While 45% believed that their housing had not contributed, 36% believed that their housing situation had a negative effect, and a further 17% believed that their housing had positively contributed, to their mental health. Beneath these average statistics, there is evidence of important differences in who could be predisposed to mental health effects. summarises the income distribution of renters who experienced either a positive or negative mental health effect of the pandemic. It shows that at higher income levels, there is a roughly even split between the number of people who experience a positive or negative mental health effect of their housing. Individuals with fewer household financial resources, however, appear to attribute dominantly negative mental health effects to their recent housing circumstances.

Figure 3. Effect of current housing circumstances on mental health (MH), by household annual income (pre COVID-19).

Overall, the quantitative survey analysis suggests that there has been high prevalence of mental health and well-being related effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on renters. While some renters appear unaffected, a majority experienced some form of negative effect. Striking in the data, are the very high numbers of renters who experienced anxiety, worry, loneliness, isolation, helplessness, and difficulties in their personal relationships, during COVID-19. Within the average data, there is an indication that some factors, such as landlord type and income level, may have provided some degree of protection for mental health. This will be further explored using the in-depth digital diary data.

Across the qualitative data, the findings of the survey analysis are echoed. A series of clear themes emerge that inform our understanding of the mental health and well-being of renters during the pandemic. Uncertainty and precarity in the rental sector; the form and quality of rental dwellings, and the effects of and on personal and work relationships provide us with a thematic framework.

Uncertainty and precarity in the rental sector

The digital diaries were undertaken in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. It was during a period of time where there were significant lockdowns in various regions around Australia and well documented (e.g., Shakespeare-Finch et al., Citation2020) job losses in the first wave of the pandemic. Even before the pandemic, renter households in Australia were already considered amongst the most vulnerable population cohorts (Beer et al., Citation2015), and the rapid economic, social and health changes which emerged during the early months of the pandemic were noted by participants as exacerbating a range of real, and perceived uncertainty about the security of their housing situation (Buckle et al., Citation2020). People who had never before had difficulties paying their rent were faced with the real threat of not being able to afford their housing rental payments with many reporting impacts to their mental health and well-being. An uncertain financial future is portrayed in the diaries as a central reason why renters were worried, anxious, and stressed. One renter explained how their financial concerns impacted on sleep and wider well-being:

I’ve been keeping track of our finances in much more detail than usual and it’s causing me a bit of anxiety and affecting my sleep. I’m usually responsible for managing the family finances which, during normal times, I barely need to keep an eye on. I’m now checking our bank accounts and tracking spreadsheet obsessively.

It was very stressful that I was overnight left out of work, and there was risk my partner would also lose her job. Obviously, there was stress involved, and having a roof over your head is very important! It does contribute to your stress levels, knowing that you might end up living on the street.

So, at the moment I am lucky because of JobKeeper, but come 27th of September I don’t know what is going to happen. So, I am watching what I do, and I have no big plans. I just hope nothing bad happens like a major car problem, or an appliance… something that is out of your control.

There is no support… we were supposed to leave [the country] on the 7th of June, but they cancelled all flights, and after they cancelled all flights we didn’t have anywhere to go because we were leaving, we had terminated our lease agreement.

Form and quality of the living environment

The form and quality of rental dwellings was recognised by renters as being important for their well-being during the pandemic, as they spent longer periods of time in their homes due to lockdowns and other restrictions. For example, participants explained that it was challenging spending more time at home. Renters often viewed physical exercise as an escape that promoted their mental health and well-being. For example, one renter stated:

Mentally you don’t like to be stuck inside…I think even just going out for some physical exercise has helped me.

It felt great being in the fresh air. Certainly helps improve one’s mental health!

Somehow coming through the roof…so we taped all the gaps in the bathroom…but then smoke started coming in from the kitchen, so we gave up at that point.

There is nothing holding the window in place, I can literally remove the entire pane myself and then put it back. I have asked my real estate agent to fix the rattling as sometimes it wakes me up at night and is very distracting … I have not received a response to this request.

I do not want to inconvenience my housemate with an indefinite lounge-room workstation setup.

I am not as efficient as I was, as I live where I work… I just dislike my room now, at any chance I just leave….

I feel pretty gloomy, I don’t like working from home, I like to keep my work and home life very separate and of course working from home has forced me to compromise on that.

Relationships

Relationships of all forms were revealed as particularly important during the pandemic – both as a supporting resource for well-being, or a reason for a reduction in well-being. For example, one renter explained that he had been having relationship challenges with his partner during lockdowns and that their rental housing situation made it difficult for either to move on. Another participant described tensions in their shared house, caused by the failure of one house member to adhere to COVID-19 public health guidelines:

…the feeling of powerlessness over the actions of those one is living with… during the last lockdown, my housemate was regularly spending weekends over at the homes of multiple friends and colleagues in addition to that of her partner.

While my postcode was not locked down, my friends were. Birthday celebrations cancelled …border closure. Cannot get to NSW [New South Wales]. My entire Australian family lives in NSW. Can’t see family.

Striking across the diaries is the repetition of stories from renters describing that their relations with neighbours had strengthened through adversity, and new communities had formed:

I talk to all of my neighbours, we are now all on a WhatsApp group, in our building, and we have been supporting one another through this whole lockdown business.

We have got really nice neighbours, I got much closer with them … [during the pandemic]. One of the neighbours works at a restaurant, and when they closed the restaurant he brought all the food home and shared it with everyone in the building. Another neighbour hurt his knee, so I have been walking his dog. I’ve been chatting to the neighbours a lot more, and the people I know in the building have become a lot closer.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the role of housing as a driver and amplifier of the mental health and well-being of renters. Salient is the finding that more than half of the respondents in the large national survey believed that the pandemic had negatively affected their mental health. This reinforces emerging work on renter mental health during the pandemic, with anxiety, depression and loneliness being found elsewhere (see, for example, Bower et al. Citation2021). Our research suggests that the negative well-being impacts during the pandemic had often manifested from the stress of financially being unable to pay rent, typically because of job loss or reduced hours. The loss of employment also contributed to having a lack of purpose or meaning, a loss of engagement and isolation (Seligman, Citation2011), as renters were left without work and without other outlets, given stay-at-home lockdown orders. While the various levels of government in Australia had provided different financial support packages and introduced a range of support for tenants and landlords (such as reducing or pausing rental and mortgage payments, eviction moratoriums and financial support for loss of work or work hours) which often helped the immediate needs of renters, this did not seem to ease the concern for their housing future. This was because there were significant concerns about what would happen once any assistance or protection was removed, such as would renters be forced to pay back any rent arrears accrued even if their own financial situation had not improved. To help address this, government agencies who rapidly provide short-term support (financial or otherwise) must be clear about what happens once support ends. This would provide a level of certainty for concerned renters. Furthermore, governments should develop clear processes about how renters facing unexpected financial challenges (such as from job loss during a pandemic) could navigate negotiations with landlords. In the case of the Victorian Government, such a negotiation process was developed in late 2020 (post this research). Future research should explore outcomes from that process development.

During the pandemic, the public health measures greatly reduced the amount of time all Australians spent outside of their homes – working, exercising, socialising. For many renters, these isolation restrictions impacted on their mental health, and the design characteristics of their housing appear to have amplified these mental health effects. For instance, renters experienced negative well-being outcomes more often when they were in small apartments with no balcony, dark homes, and where there were defects that were not being addressed. Even minor defects, such as a rattling window, appeared to have increased in importance as renters spent more time at home. We suggest that these dwelling problems, in combination with the inability of renters to address them, almost certainly resulted in a lack of perceived control for renters, well-established as a correlate of poorer mental health outcomes (for example Mason et al., Citation2013). While a number of states in Australia have introduced minimum apartment design requirements (e.g. room size, access to light), it will take time for the benefits of these to be the dominant apartment type. Similarly, while there are some minimum rental standards starting to be implemented in Australia, these could be improved to deliver enhanced quality and function in rental properties. This would likely improve usability and health and well-being outcomes for renters and be of benefit not just in a pandemic but in other times as well.

The social proximity of shared housing or living in multi-occupancy buildings appears to have influenced tenant mental health during the pandemic – for better and for worse. Renters found support through connecting (in person and digitally) with those in their building or nearby. The neighbourhood, local parks and facilities for exercise also helped promote well-being, especially for those living in small and crowded units. While the provision of internal space in a dwelling is largely left to the market, policy makers and urban planners can focus on providing sufficient amenity, such as parks or areas to exercise, within proximity to dwellings.

The extended time spent in close social proximity to others also strained relationships, both in intimate relationships, as well as friendships with the house. For example, in some cases share-house members had ignored stay-at-home restrictions, which left flatmates feeling vulnerable to COVID-19, and created tension within share-homes. The need to work from home in shared houses also created other challenges, such as from noise, cigarette smoke, or the simple need to share work and home spaces. For those that were working from home, their productivity, and subsequent accomplishments, were challenged by such social dynamics, as well as the physical ergonomic difficulties associated with creating an appropriate working station in a bedroom or communal living space. This lack of space and resources to create a suitable work environment at home further emphasises Bower et al. (Citation2021) recent findings, which outlined these challenged for renters during the pandemic.

This study has provided insight into the emerging research on housing and well-being. For future housing and the wider built environment decisions, there ought to be focus by policy makers and urban planners on achieving greater social value within and around homes to enhance resident well-being. This should include ways to not only provide housing security and safety, but to also focus on: creating social connectiveness in buildings for those that may feel isolated; having more liveable spaces; providing greater access to exercise within neighbourhoods; and enhancing both the quality of building and its punctual maintenance. This research has contributed through revealing the state of well-being in Australian renters during the pandemic, as well as explaining why levels of well-being were both reduced and enhanced. Greater understanding by researchers, policy makers and urban planners into how housing, and the wider built environment, influences well-being will aid the design and creation of better buildings, systems, and policy. This would be of benefit to the well-being of vulnerable groups, such as some renters, as well as other residents.

Limitations

A limitation of this research is that it occurred at a certain point in time during the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. This meant there was no baseline data to compare the analysis to and the data collection relied on the participants self-reporting changes or implications from their own perspectives. The digital diaries attempted to address this limitation by gathering data over a one-month period which allowed for data checking and a more in-depth lived experience to be provided. The data was also unable to look at the implications of different government policies on the implications for well-being of those in this study cohort. Future research could aim to look at these other elements.

Conclusions

Our study shows that renters’ basic housing situations played a key role in their mental health outcomes. With this in mind, further work is required by policy makers in supporting renters with better housing security and protection against eviction due to changes in life circumstances, ensuring housing is fit for purpose and meets minimum quality and performance requirements, and providing opportunities to improve internal and external relationships such as connectiveness to other people within their buildings. Previous work on the implications of the pandemic on renter mental health has suggested a focus on identifying ideal housing design and neighbourhood characteristics, as well as providing housing security (Bower et al., Citation2021). Our work found that well-being could be enhanced through creating greater opportunities for connecting socially within the multiple occupancy building, opportunities for local exercise and providing swift rectification of building defects. These should be considered by policy makers, urban planners and researchers as characteristics that can enhance well-being through housing design and neighbourhood, alongside housing safety, space, and security.

Previous research has highlighted a clear link between health and housing. This is not only confined to physical health, but there is also a growing body of literature extending to mental health and well-being. Our research has highlighted how the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced the connections between well-being and housing. Over half of renters experienced negative mental health during the pandemic, with our qualitative findings demonstrating how housing security is essential for avoiding such reduction in mental health. Many renters were in precarious employment sectors during the pandemic and had concerns about financially paying rent. This led to stress, anxiety, concern for their housing security, and in some cases, a fear of homelessness. Beyond housing security, there were ways in which well-being was enhanced through, for example, having: good access to local facilities for exercise; quality housing devoid of defects; and greater opportunities to network with others within multi-occupancy buildings.

This work has highlighted that housing is no longer simply a place to sleep and invest. It is now a place of refuge and a public health intervention, as part of our strategy for combating COVID-19, and other potential variants and infectious diseases. This becomes particularly important for renters, who typically live in smaller, less secure, and more crowded spaces. Renting has been one of the fastest growing forms of tenure in Australia, with high-density apartments offering a life close to work and amenities at a more affordable price. This lifestyle, prior to COVID-19, meant that people would often choose to rent for life, rather than temporarily rent on their way to home purchase. The change in the functionality of homes to a public health intervention, means there needs to be more emphasis by policy makers and key housing stakeholders on reaching (and going beyond) minimum housing standards, as well as design considerations to enable shared housing (but not shared spaces). It is recommended that there is greater consideration of well-being in housing policy, with a focus on promoting positive emotions, offering opportunities for social engagements and relationships within multiple occupancy buildings, better access to green spaces, and functional homes for work and living, as well as sleep and security.

Importantly, this study is based on data collected in mid to late 2020. It provides us, to some extent, with a look back to the experience of renting at the beginning of a global pandemic. It documents the experiences of renting at a time of significant uncertainty, where many people were unable to work, our houses were not designed to be workplaces, or places of isolation, and efficient vaccines had not yet been trialled and distributed. It shows, at both the macro scale of a population survey, and the micro scale of in-depth diaries, the very detailed and largely unforeseen way that people’s mental health and well-being were affected. If we had imagined a pandemic, instead of experiencing one, it is unlikely that we could have predicted the extent or shape of its impact. There are many lessons to take from this – for our housing system, our planning system, our welfare system, employment, work, education, and all other parts of Australian life. As we head beyond 2021, with a public policy recognition that suppression, rather than elimination of COVID-19 is the probable course, these lessons become all the more important.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the participants of the studies presented in this paper for their contribution to this research and the Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute whose funding allowed this work to be conducted.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- The Lancet (2020). Redefining vulnerability in the era of COVID-19. The Lancet, 395(10230), 1089. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30757-1

- ABS (2019). Housing occupancy and costs. Australian Bureau of Statistics. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/housing/housing-occupancy-and-costs/latest-release.

- Andrews, D. (2020). Statement from the premier. Victorian Government.

- Baker, E., Beer, A., Baddeley, M., London, K., Bentley, R., Stone, W., Rowley, S., Daniel, L., Nygaard, A., Hulse, K., & Lockwood, T. (2021). The Australian Rental Housing Conditions Dataset. (Publication No. doi/10..26193/IBL7PZ) from ADA Dataverse, https://doi.org/10.26193/IBL7PZ

- Baker, E., Daniel, L., Beer, A., Bentley, R., Rowley, S., Baddeley, M., London, K., Stone, W., Nygaard, C., Hulse, K., & Lockwood, T. (2022). An Australian rental housing conditions research infrastructure. Science Data 9, 33. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41597-022-01136-5

- Baker, E., Beer, A., Lester, L., Pevalin, D., Whitehead, C., & Bentley, R. (2017). Is Housing a Health Insult? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(6), 567. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14060567

- Baker, E., & Lester, L. (2017). Multiple housing problems: A view through the housing niche lens. Cities, 62, 146–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2016.10.001

- Baker, E., Lester, L., Beer, A., & Bentley, R. (2019). An Australian geography of unhealthy housing. Geographical Research, 57(1), 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12326

- BBC News. (2020). 26/10/2020). Covid in Australia: Melbourne to exit 112-day lockdown, BBC News. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-australia-54686812

- Beer, A., Baker, E., Wood, G., & Raftery, P. (2011). Housing policy, housing assistance and the wellbeing dividend: Developing an evidence base for Post-GFC economies. Housing Studies, 26(7-8), 1171–1192. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2011.616993

- Beer, A., Bentley, R., Baker, E., Mason, K., Mallett, S., Kavanagh, A., & LaMontagne, T. (2015). Neoliberalism, economic restructuring and policy change: Precarious housing and precarious employment in Australia. Urban Studies, 53(8), 1542–1558. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015596922

- Bentley, R., & Baker, E. (2020). Housing at the frontline of the COVID-19 challenge: A commentary on “Rising home values and Covid-19 case rates in Massachusetts”. Social Science & Medicine, 265, 113534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113534

- Bentley, R., Baker, E., Simons, K., Simpson, J. A., & Blakely, T. (2018). The impact of social housing on mental health: Longitudinal analyses using marginal structural models and machine learning-generated weights. International Journal of Epidemiology, 47(5), 1414–1422. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyy116

- Berry, S., Whaley, D., Davidson, K., & Saman, W. (2014). Near zero energy homes – what do users think? Energy Policy, 73, 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2014.05.011

- Bower, M., Buckle, C., Rugel, E., Donohoe-Bales, A., McGrath, L., Gournay, K., Barrett, E., Phibbs, P., & Teesson, M. (2021). ‘Trapped’, ‘anxious’ and ‘traumatised’: COVID-19 intensified the impact of housing inequality on Australians’ mental health. International Journal of Housing Policy, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2021.1940686

- Bratt, R. G. (2002). Housing and family well-being. Housing Studies, 17(1), 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030120105857

- Buckle, C., Gurran, N., Phibbs, P., Harris, P., Lea, T., & Shrivastava, R. (2020). Marginal housing during COVID-19, AHURI Final Report No. 348. Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited. https://doi.org/10.18408/ahuri7325501

- Burridge, A. (2020). Here’s how the Victoria-NSW border closure will work – and how residents might be affected. https://theconversation.com/heres-how-the-victoria-nsw-border-closure-will-work-and-how-residents-might-be-affected-142045

- CABE. (2002). The value of good design. How buildings and spaces create economic and social value. Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment.

- Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., & Berntson, G. G. (2003). The Anatomy of Loneliness. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(3), 71–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.01232

- Campion, J., Javed, A., Sartorius, N., & Marmot, M. (2020). Addressing the public mental health challenge of COVID-19. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 7(8), 657–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30240-6

- Casey, S., & Ralston, L. (2020). Coronavirus puts casual workers at risk of homelessness unless they get more support. Retrieved April 30, 2020, from https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-puts-casual-workers-at-risk-of-homelessness-unless-they-get-more-support-133782

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

- Clapham, D. (2010). Happiness, well-being and housing policy. Policy & Politics, 38(2), 253–267. https://doi.org/10.1332/030557310X488457

- Clapham, D., Foye, C., & Christian, J. (2018). The concept of subjective well-being in housing research. Housing, Theory and Society, 35(3), 261–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2017.1348391

- Coates, B., Cowgill, M., Chen, T., & Mackey, W. (2020). The charts that show coronavirus pushing up to a quarter of the workforce out of work. Retrieved 30/07/2020, from https://theconversation.com/the-charts-that-show-coronavirus-pushing-up-to-a-quarter-of-the-workforce-out-of-work-136603

- D’alessandro, D., Gola, M., Appolloni, L., Dettori, M., Fara, G. M., Rebecchi, A., Settimo, G., & Capolongo, S. (2020). COVID-19 and living space challenge. Well-being and public health recommendations for a healthy, safe, and sustainable housing. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis, 91(9-S), 61.

- Daniel, L., Baker, E., & Williamson, T. (2019). Cold housing in mild-climate countries: A study of indoor environmental quality and comfort preferences in homes, Adelaide, Australia. Building and Environment, 151, 207–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2019.01.037

- Deaton, A. (2008). Income, health, and well-being around the world: Evidence from the Gallup World Poll. The Journal of Economic Perspectives : a Journal of the American Economic Association, 22(2), 53–72. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.22.2.53

- Department of Health. (2021). Coronavirus (COVID-19) case numbers and statistics Retrieved 13/12/2021, from https://www.health.gov.au/news/health-alerts/novel-coronavirus-2019-ncov-health-alert/coronavirus-covid-19-case-numbers-and-statistics

- Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 403–425. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145056

- Easterlin, R. A. (2013). Happiness, growth and public policy. Economic Inquiry, 51(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.2012.00505.x

- Farha, L. (2020). COVID-19 Guidance Note: Protecting renters and mortgage payers. United Nations. Retrieved July 8, 2020, from https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Housing/SR_housing_COVID-19_guidance_rent_and_mortgage_payers.pdf.

- Gilbert, A. (2016). Rental housing: The international experience. Habitat International, 54, 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.11.025

- Grattan, M. (2020). Victoria locks down 36 Melbourne suburbs to try to control COVID-19 spike. https://theconversation.com/victoria-locks-down-36-melbourne-suburbs-to-try-to-control-covid-19-spike-141707

- Gualano, M. R., Lo Moro, G., Voglino, G., Bert, F., & Siliquini, R. (2020). Effects of Covid-19 lockdown on mental health and sleep disturbances in Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(13), 4779. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17134779

- Huang, Y., & Zhao, N. (2020). Generalized anxiety disorder, depressive symptoms and sleep quality during COVID-19 outbreak in China: a web-based cross-sectional survey. Psychiatry Research, 288, 112954. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112954

- Hunt, G. (2020). First confirmed case of novel coronavirus in Australia. Department of Health.

- Kelly, D., Shaw, K., & Porter, L. (2020). Melbourne tower lockdowns unfairly target already vulnerable public housing residents The Conversation.

- Keyes, C. L., Shmotkin, D., & Ryff, C. D. (2002). Optimizing well-being: the empirical encounter of two traditions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6), 1007–1022.

- Layard, R., Clark, A., & Senik, C. (2012). The causes of happiness and misery. In J. F. Helliwell, R. Layard & J. Sachs (Eds.), World Happiness Report. The Earth Institute, Columbia University.

- Manville, M., Monkkonen, P., & Lens, M. (2020). COVID-19 and renter distress: Evidence from Los Angeles. August 2020. UCLA Reports: Policy Brief: UCLA.

- Mason, K. E., Baker, E., Blakely, T., & Bentley, R. J. (2013). Housing affordability and mental health: Does the relationship differ for renters and home purchasers? Social Science & Medicine (1982), 94, 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.023

- McKee-Ryan, F., Song, Z., Wanberg, C. R., & Kinicki, A. J. (2005). Psychological and physical well-being during unemployment: A meta-analytic study. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(1), 53–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.1.53

- Moore, T., Nicholls, L., Strengers, Y., Maller, C., & Horne, R. (2017). Benefits and challenges of energy efficient social housing. Energy Procedia., 121, 300–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2017.08.031

- Morrison, S. (2020). Border restrictions. Australian Government.

- Murthy, D. (2008). Digital ethnography:An examination of the use of new technologies for social research. Sociology, 42(5), 837–855. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038508094565

- OECD (2020). Create Your Better Life Index. Retrieved September 7, 2020, from http://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/#/11111111111

- Oswald, D., Moore, T., & Lockrey, S. (2021). Flammable cladding and the effects on homeowner well-being. Housing Studies, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2021.1887458

- Pereira, A. (2020). Long-term neurological threats of COVID-19: A call to update the thinking about the outcomes of the coronavirus pandemic. Frontiers in Neurology, 11, 308–308. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.00308

- Pevalin, D. J., Reeves, A., Baker, E., & Bentley, R. (2017). The impact of persistent poor housing conditions on mental health: A longitudinal population-based study. Preventive Medicine, 105, 304–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2017.09.020

- Pevalin, D. J., Taylor, M. P., & Todd, J. (2008). The dynamics of unhealthy housing in the UK: A panel data analysis. Housing Studies, 23(5), 679–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030802253848

- Phillips, S. (2020). LA’s COVID-19 Response Should Prioritize Long-Term Rent-Stabilized Tenants for Housing Assistance. May 2020. UCLA Reports: Policy Brief: UCLA.

- Pink, S., Leder Mackley, K., Morosanu, R., Mitchell, V., Bhamra, T., Cox, R., & Buchli, V. (2017). Making Homes: Ethnography and Design. Taylor & Francis Group.

- Rayner, C., Lokugamage, A., & Molokhia, M. (2020). Covid-19: prolonged and relapsing course of illness has implications for returning workers. BMJ.

- Raynor, K., Wiesel, I., & Bentley, B. (2020). Why staying home during a pandemic can increase risk for some Discussion Paper: The University of Melbourne: Affordable Housing Hallmark Research Initiative.

- Rehman, U., Shahnawaz, M. G., Khan, N. H., Kharshiing, K. D., Khursheed, M., Gupta, K., Kashyap, D., & Uniyal, R. (2021). Depression, anxiety and stress among Indians in times of Covid-19 Lockdown. Community Mental Health Journal, 57(1), 42–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00664-x

- Rogers, D., & Power, E. (2020). Housing policy and the COVID-19 pandemic: the importance of housing research during this health emergency. International Journal of Housing Policy, 20(2), 177–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2020.1756599

- Rossi, R., Socci, V., Talevi, D., Mensi, S., Niolu, C., Pacitti, F., Di Marco, A., Rossi, A., Siracusano, A., & Di Lorenzo, G. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy [Brief Research Report]. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 790 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00790

- Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage.

- Seligman, M. E. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Simon and Schuster.

- Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

- Shakespeare-Finch, J., Bowen-Salter, H., Cashin, M., Badawi, A., Wells, R., Rosenbaum, S., & Steel, Z. (2020). COVID-19: An australian perspective. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 25(8), 662–672. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2020.1780748

- Spies-Butcher, B. (2020). The temporary welfare state: The political economy of job keeper, job seeker and “snap back. The Journal of Australian Political Economy, 85, 155–163. https://doi.org/10.3316/ielapa.213347539532842

- Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J.-P. (2010). Mismeasuring our lives: Why GDP doesn’t add up. : The New Press.

- Stone, L. (2020). Melbourne’s second lockdown will take a toll on mental health. We need to look out for the vulnerable. https://theconversation.com/melbournes-second-lockdown-will-take-a-toll-on-mental-health-we-need-to-look-out-for-the-vulnerable-142172

- Telfar-Barnard, L., Bennett, J., Howden-Chapman, P., Jacobs, D. E., Ormandy, D., Cutler-Welsh, M., Preval, N., Baker, M. G., & Keall, M. (2017). Measuring the effect of housing quality interventions: The case of the New Zealand “Rental Warrant of Fitness”. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(11), 1352. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14111352

- Turner, R. J. (1981). Social support as a contingency in psychological well-being. (pp. 357–367. American Sociological Assn. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136677

- Twenge, J. M., & Joiner, T. E. (2020). U.S. Census Bureau-assessed prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in 2019 and during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Depress Anxiety, 37(10), 954–956. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.23077

- WHO. (2022). Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard. Retrieved January 10, 2022, from World Health Organization. https://covid19.who.int/

- Yancy, C. (2020). Covid-19 and African Americans. Jama Network, 323(19), 1891–1892. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.6548

- Yelin, D., Wirtheim, E., Vetter, P., Kalil, A. C., Bruchfeld, J., Runold, M., Guaraldi, G., Mussini, C., Gudiol, C., Pujol, M., Bandera, A., Scudeller, L., Paul, M., Kaiser, L., & Leibovici, L. (2020). Long-term consequences of COVID-19: research needs. The Lancet. Infectious Diseases, 20(10), 1115–1117. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30701-5

- Ziffer, D. (2020). Renters desperate for relief as 1 million jobs set to disappear due to coronavirus Retrieved September 8, 2020, from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-03-24/renters-desperate-for-relief-as-jobs-disappear-coronavirus/12086080