Abstract

Homelessness is increasingly being addressed with tiny house villages. These developments face barriers, the greatest of which is NIMBYism (Not-in-my-backyard sentiment) (Evans, Citation2021). Through a stakeholder survey, this research examines community perceptions of, and preferences for, various visual, physical, and social factors related to tiny house villages for the homeless. The survey finds that stakeholders do have distinct preferences for certain physical characteristics and traits related to tiny house villages for the homeless. The research suggests that taking such preferences into account may result in tiny house villages for the homeless that enjoy greater community support than those that do not.

Introduction

The utilisation of tiny houses and tiny house villages to address homelessness is a growing phenomenon across the country (Evans, Citation2021; Evans, Citation2020). A recent inventory has found that there are at least 115 tiny house villages for homeless persons in the U.S. that are currently in operation, slated to open in the future, where efforts have been abandoned, or where the operational status of the villages is unknown (Evans, Citation2020). The study found that the average size of tiny houses in tiny house villages for the homeless is 205 square feet (Evans, Citation2020), though there is no formal definition as to what size constitutes a tiny house.

Homelessness is a serious problem in the United States (U.S.). It is estimated that each night there are approximately half a million homeless individuals in the U.S. (National Alliance to End Homelessness, Citation2018). The specific experiences of homeless persons differ greatly; from overnight stays in emergency shelters, to homeless encampments, living in cars, and sleeping on the streets. Similarly, the array of factors that lead to homelessness also differ; from poverty to mental health and substance abuse issues (Byrne et al., Citation2013; Caton, Citation1990; Daly, Citation2013; Hope & James, Citation1986; Mitchell, Citation2011; National Alliance to End Homelessness, Citation2018; Wright, Citation2017). Because of the many factors related to homelessness, there is not a simple remedy (Daly, Citation2013; Wright, Citation2017). However, tiny house villages for the homeless may offer a potential solution (Fowler, Citation2017; Heben, Citation2014; Jackson et al., Citation2020; Keable, Citation2017; Segel, Citation2015; Turner, Citation2016; Evans, Citation2020, Citation2021).

This research focuses on a survey instrument conducted with stakeholders at two case study locations in Missouri where tiny house villages for homeless individuals were recently constructed and opened: Eden Village, located in Springfield, and Veterans Community Project (VCP), in Kansas City. The survey analysis is part of a larger mixed methods study which examines barriers and strategies to the development of tiny house villages for the homeless at the two case locations. The survey instrument was conducted to develop an understanding of community perceptions of, and preferences for, various visual, physical, and social factors related to tiny house villages for the homeless. Prior research finds that NIMBYism (Not-in-my-backyard sentiment) is the primary barrier to the integration of tiny house villages for the homeless (Evans, Citation2021). This research supports that finding but also suggests that stakeholders, defined in this project as either residents or property owners at either case site location, have distinct preferences for certain characteristics and design elements related to tiny houses. It is hypothesised that taking such preferences into account may result in tiny house villages for the homeless that enjoy greater community support than those that do not.

This paper begins with a brief overview of the homelessness crisis and the utilisation of tiny house villages for the homeless. It then continues with an examination of the research design, an analysis of findings, and concludes with implications for planners and advocates of tiny house villages for homeless residents. It is hoped that the research will aid advocates of tiny house villages for the homeless in understanding community perceptions of these developments. Secondly, the research findings will aid tiny house village advocates towards the integration of design elements that enjoy greater community support.

Addressing homelessness: an overview of causes and solutions

There has always been an element of the population that has existed without permanent or formal housing (Caton, Citation1990; Wright, Citation2017). Yet beginning in the 1980s homelessness was recognised as a growing, persistent and unwieldly problem in the U.S. (Schwartz, Citation2014). Homelessness may be attributed to a variety of factors: poverty, lack of affordable housing, deinstitutionalisation, growing economic inequality, displacement due to factors such as gentrification, and lack of social services, all of which converged in the 1980s in the U.S. due to a political climate focussed on austerity and neoliberalism (Anderson, Citation1964; Dear & Wolch, Citation2014; Kasinitz, Citation1984; Lamb, Citation1984; LeGates & Hartman, Citation2013; Mitchell, Citation2011; Wright, Citation2017). Deinstitutionalisation policy has especially exacerbated the homelessness issue (Dear & Wolch, Citation2014; Lamb, Citation1984). As mental institutions began closing their doors as cost savings measures, droves of individuals with chronic mental or social disabilities found themselves on the streets with little or no access to social services. Deinstitutionalisation furthermore represents a trend towards reliance on the private and non-profit sectors to provide services to the homeless that were previously provided in-whole by federal or state dollars (O’Regan & Quigley Citation2000; Wolch et al., Citation1988). The growth of neoliberal policy and reliance on these sectors to provide housing for the poor in general has continued in the U.S. (Mitchell, Citation2011; O’Regan & Quigley Citation2000). Perhaps representative of this trend are the numerous tiny house villages for the homeless that have sprung up in the U.S. over the last several years; many of which are the result of private efforts (Evans, Citation2020).

The growing homelessness problem may also be attributed to neoliberal political and economic trends that put profit over people. For example, Urban Renewal resulted in the displacement of the poor and the gentrification of downtowns across the country (Anderson, Citation1964; Kasinitz, Citation1984; Lees et al., Citation2008; LeGates & Hartman, Citation2013; Wright, Citation2017). Important to this research on downsized living, is the documented loss of single-room-occupancy (SROs) hotels and boarding houses in the U.S. due to the economic restructuring of downtowns during this time period (Groth, Citation1994; Kasinitz, Citation1984; Wolch et al., Citation1988; Wright, Citation2017). Though plagued with a host of problems, such as subpar safety and insufficient maintenance, the loss of these small and affordable living arrangements for singles has resulted in a greater number of individuals living on the streets.

The array of strategies to address homelessness is as wide as the factors leading to the problem. Many would contend that the best solution to homelessness is to prevent it in the first place through the development of policies and programmes created to foster affordable low-income homeownership and rental opportunities (Schwartz, Citation2014; Tighe & Mueller, Citation2013). Other efforts focus on the homeless persons that are already on the street. Traditional measures of tackling homelessness include the provision of emergency shelters, soup kitchens, and transitional housing (National Alliance to End Homelessness, Citation2018; Wright, Citation2017). These strategies employed by both public and private entities, suggest that with a simple helping-hand up, such as offering meals and providing shelter for a brief period of time, the homeless should be able to get back on their feet. Yet the growing numbers of homeless persons on the street suggests that these short-term and quick-fix strategies are insufficient.

There is a trend towards addressing homelessness through permanent supportive housing models (National Alliance to End Homelessness, Citation2018; Segel, Citation2015; Tsemberis & Eisenberg, Citation2000). Homeless persons are provided with long-term, rather than temporary housing and necessary social services. This model generally fosters a ‘housing first’ approach, where individuals are housed rapidly without mandated prerequisites such as substance abuse treatment or job training (Abarbanel et al., Citation2016; National Alliance to End Homelessness, Citation2018; Speer, Citation2017). Advocates of this model argue that without stable shelter, it is nearly impossible for homeless people to address others problems, such as unemployment and health issues (Coleman, Citation2018; Desmond, Citation2016; Keable, Citation2017; Padgett et al., Citation2016).

Permanent supportive housing may be especially beneficial to the chronically homeless, who comprise 24% of the total population of homeless individuals (Brown et al., Citation2016; National Alliance to End Homelessness, Citation2018). The chronically homeless are defined as individuals with a disabling condition that have been either homeless for a year or more, or have had at least four episodes of homelessness in the last three years (U.S. Department of Housing & Urban Development, Citation2007). Due to their disabling condition, it is especially challenging for these individuals to break out of the cycle of homelessness without the provision of integral social services (Brown et al., Citation2016).

Research indicates that tiny house villages for the homeless are integrating a multitude of approaches to address homelessness (Evans, Citation2020). For example, of the tiny house villages open in 2019, 25% provided permanent housing, 72% temporary, and 3% both permanent and temporary housing (Evans, Citation2020). Some villages specifically serve the chronically homeless population (73%) and others are for the homeless population at large (27%). Despite the variance in approaches towards a solution, and types of homeless persons served, the fact that at least 25% of tiny house villages for the homeless are integrating a more permanent model suggests that these villages have the potential to offer a more progressive solution to the growing homelessness crisis.

Tiny houses and homelessness

The trend towards addressing homelessness with tiny house villages may be attributed to a few factors. Perhaps most significantly, tiny houses may be viewed as a cost-effective means of housing the homeless (Fowler, Citation2017; Heben, Citation2014; Jackson et al., Citation2020; Segel, Citation2015). For instance, there is evidence that tiny houses are generally more cost-effective than other types of subsidised housing (Segel, Citation2015; Turner, Citation2016, p. 931). One study suggests that tiny houses can reduce the cost for traditional subsidised units by more than half, which would allow for a greater number of homeless persons to be served under the same operating budget (Segel, Citation2015). The study, conducted in the state of Washington, estimated that the average subsidised apartment costs $239,396, whereas the average tiny house (with plumbing, electricity, and conditioning) costs just $102,000 (Segel, Citation2015). It might be inferred that similar savings could be actualised in all housing sectors by building small rather than large units. Though overall tiny house costs may vary widely depending on factors such as land cost, building materials and the inclusion or exclusion of amenities such as indoor plumbing, electricity and heating/cooling units, (Evans, Citation2020) it generally costs less to build small rather than large.

However, there is literature which turns a critical eye towards the emergence of ‘micro-living’ or shrinking domestic space as a means of addressing the growing housing crisis (Harris & Nowicki, Citation2020). It could be argued that the marketing of small living quarters, such as tiny houses, normalises substandard housing conditions rather than solving the need for adequate affordable housing (Harris, Citation2019; Harris & Nowicki, Citation2020). It could also be argued that minimum square footages were initially put in place to avoid the crowded and cramped living arrangements historically associated with poverty, such as tenement flats. Though tiny house villages may provide an innovative and affordable means of addressing homelessness, it remains unknown as to whether the strategy will prove sufficient in the long run due to their diminutive nature.

Tiny home villages may also be viewed as an appealing method of addressing homelessness in that they allow residents to have their own detached unit, while still fostering a sense of community. This balance allows residents to have a sense of independence while encouraging interaction and community involvement, the latter of which is deemed critical for the creation of social support systems among homeless persons (Heben, Citation2014; Speer, Citation2017). Therefore, villages may be seen as a superior method to housing homeless persons rather than in high-density apartment complexes, which have been used to house poorer classes in the past (Daly, Citation2013).

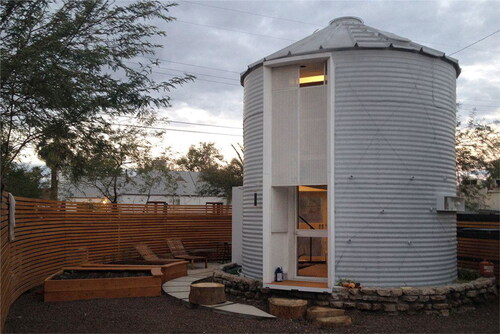

A recent inventory of all the tiny house villages for the homeless in the U.S. not only documents village locations, but examines several facets of these villages, including physical characteristics, such as size, number, and cost of units, and social amenities, including the potential availability of mental and basic medical services at each site. The inventory demonstrates that tiny house villages for the homeless vary significantly in terms of the design and characteristics of individual units, village attributes, physical and social amenity offerings, and the types of residents they serve (Evans, Citation2020). For example, tiny houses on wheels (THOWs) are designed to be mobile and have become quite trendy in the popular media. Though such units have been used to provide shelter for people experiencing homelessness, only 13% of operational tiny villages for the homeless are comprised of THOWs (10% are solely THOW villages, and 3% have both THOWs and foundation-built tiny homes) (Evans, Citation2020). The database also reveals that the individual units in tiny house villages may be manufactured (13%), stick-built (87%), and/or consist of a wide-variety of building materials. Though tiny house villages for the homeless differ significantly in terms of village attributes, amenities, and design, all share the commonality of offering the potential for an affordable housing solution to homelessness.

Survey instrument design

The research involved a survey of stakeholders at each case site community in order to better understand if various visual, physical, and social elements related to tiny house villages for the homeless influence stakeholder perceptions of these developments. The survey involved an embedded Visual Preference Survey (VPS), which was first used in the field of planning by Anton Nelessen (Ewing et al., Citation2005) in order to understand how preferences shape place and design perceptions. Prior scholarship suggests that it is important to take the public’s aesthetic preferences into account when constructing the built environment (Nasar, Citation1998) and that highly-regarded places share certain characteristics, such as vernacular (traditional) architecture and quality building materials (Nelessen, Citation1994). In this research the VPS was integrated to understand if there is a difference in average preferences for three visual design elements that were found particularly influential to stakeholder perceptions in prior tiny house research (Evans, Citation2019). Those elements are traditional (vernacular) architecture, non-traditional (modern) architecture, and tiny houses with wheels (THOWs).

The photos used in the VPS were carefully selected via a sort and rank task in order to avoid bias and issues with confounding variables. Validity threats associated with bias or confounding variables were also addressed by creating predetermined criteria for VPS photos including: none of the photos was of tiny houses at either case site, and all involved colour photography, similar scale, emphasis on structure rather than landscape, and no people or pets (Groat & Wang, Citation2002; Kaplan & Kaplan, Citation1989; Stamps, Citation2000). The survey also examined via a 5-point-Likert scale, several visual, physical, and social elements that may influence stakeholder preferences of tiny house villages for the homeless. The factors examined in relationship to stakeholder preferences are exploratory and based on prior research (Evans, Citation2019, Citation2020). The factors are not exhaustive of all the considerations that may impact stakeholder preferences and this is a limitation of the research. Finally, there was also an open-ended question at the end of the survey which asked participants to include comments that may be important for understanding stakeholder preferences of tiny house villages for the homeless.

The survey involved nonprobability and purposive sampling of stakeholders, defined as either residents or property owners at either case site city. This includes Springfield, Missouri (Eden Village), and the Kansas City metropolitan area, which may include stakeholders in both Missouri and Kansas, though the tiny house village (Veterans Community Project) is located on the Missouri side of the city. In order to ensure that the survey represented the perspectives of resident stakeholders, an early survey question screened participants as to their residency status and only allowed case site residents or property owners to proceed. This allowed for the inclusion of residents of the tiny house villages themselves, with the open-ended survey question responses suggesting that several village residents participated in the survey. Stakeholders were chosen as they are key actors in local land use policy decisions. The survey instrument, designed with Qualtrics software, was web-based and distributed to stakeholders that had special interest or knowledge in tiny house villages for the homeless, such as homelessness organisations and planning agencies in each city. The survey link was shared on webpages such as that of the City of Springfield, and the Facebook pages of each tiny home village case site in addition to several nonprofits advocating for either tiny houses or the homeless. The survey was open from 28 February to 22 April 2019, and was completed by 219 stakeholders. However, prior to analysis the data was screened for factors such as missing data (greater than 5%, excluding demographics) and outliers. This resulted in a sample size of 154 participants for analysis, 102 from Springfield and 52 from Kansas City.

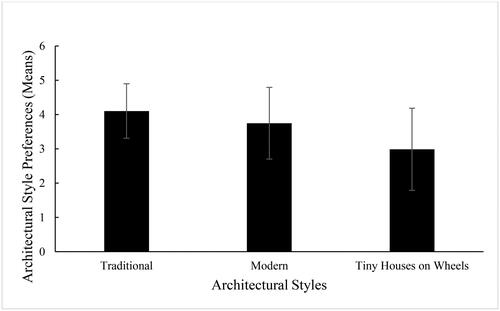

A five-point Likert scale was used in the survey, which is common in preference studies (Groat & Wang, Citation2002; Kaplan & Kaplan, Citation1989). In the VPS portion of the survey, a Friedman test and pairwise comparisons were performed to statistically analyse whether a difference existed in average preferences for traditional architecture, non-traditional architecture and THOWs as they specifically apply to tiny house villages for the homeless. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse which factors impact stakeholders’ preferences of tiny house villages for the homeless. Although Mann-Whitney U tests were initially performed to analyse differences in stakeholder preferences by case site location, the findings have not been reported due to the large difference in sample size between the locations. As a result, this paper examines findings taken as whole.

Demographic data collected in the survey revealed that participants primarily identified as Caucasian (89%), female, (76%) educated (63% hold a bachelor’s degree or higher), and homeowners (66%). These results are similar to a 2013 survey done by tiny house advocate and creator of “The Tiny Life” blog, Ryan Mitchell, whose survey intent was to learn more about the demographics of those interested in tiny house dwelling. An examination of 2010 U.S. Census Data indicates that the characteristics of survey participants in this study are not fully aligned with case site demographic averages, primarily in terms of gender and racial identity. The nonprobability and purposive sampling of stakeholders with an interest in utilising tiny houses to address homelessness has resulted in demographics that are more representative of those interested in the tiny house movement as a whole, rather than of the populace of the case sites themselves and is a limitation of the research. Future research that involves probability sampling of stakeholders may lead to a more holistic representation of perceptions of tiny house villages for the homeless.

Statistical analyses were performed using JASP software. The quantitative statistical analysis and analyses of open-ended responses has led to the development of an encompassing understanding of stakeholder perceptions of tiny house villages for the homeless. Furthermore, though a different leg of the research focuses specifically on the qualitative case study findings and the villages themselves (Evans, Citation2021) this analysis minimally incorporates supporting statements from the case study interviews which were conducted with founders and managers at each case site village. The result is in two primary themes which have been organised into three strategies for integrating tiny house villages for the homeless into communities .

Table 1. The two primary themes and three strategies.

Tiny house villages for the homeless and NIMBY perceptions

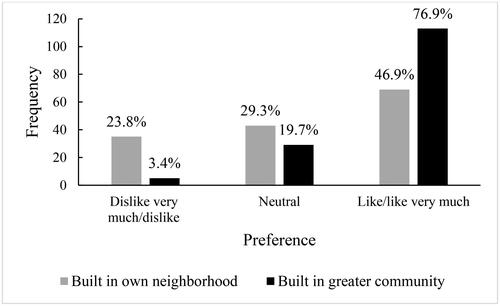

The research survey instrument indicated that stakeholders hold perceptions of NIMBYism (Not-in-my-backyard sentiment) towards tiny house villages for the homeless. This is in compliance with the literature that has found NIMBYism to be a barrier to the integration of social services that serve the homeless (Lyon‐Callo, Citation2001; Oakley, Citation2002) and to tiny house villages for the homeless themselves (Evans, Citation2021). The responses to two survey questions were especially telling: one asked participants to indicate their level of preference on a 5-point Likert scale for a tiny house community for the homeless being built in their own neighbourhood. The next question asked for their level of preference for a tiny house village for the homeless in their community, but not in their neighbourhood. Though many survey participants were likely advocates of tiny house villages for the homeless due to purposive sampling, descriptive statistics reveal a far greater preference for such villages being located elsewhere than in one’s own backyard (). This finding supports the literature that suggests NIMBY opposition to social services that address homelessness increases with proximity to the service (Dear & Gleeson, Citation1991).

Figure 1. Histogram of stakeholder preferences for tiny house villages in one’s own neighbourhood versus one’s community, but not own neighbourhood. The results suggest NIMBYism.

Numerous comments obtained from the open-ended question in the survey instrument also suggest that NIMBYism is a significant barrier to tiny house villages for the homeless:

I’m not a NIMBY, but homeless people bring a certain undesirable element to the area.

Dealing with community concerns, like disruptions and blight are a key part of this. Figuring out how to deal with the negative impacts on the community where they are built is key to making them [tiny house villages] a success.

I believe these villages will become run down. As these developments deteriorate, I would fear decreasing property values and increased narcotic use and crime rates.

Stakeholders have distinct preferences for tiny house villages for the homeless

Though the survey suggests that NIMBY sentiments serve as a hindrance to the integration of tiny house villages for the homeless, it also found that stakeholders have distinct preferences for several visual elements related to tiny house villages for the homeless, as well as for specific physical and social factors. Understanding these preferences is important, as stakeholders are key actors in the development of land use policy. It is hypothesised that integrating these preferences into tiny house villages for the homeless will result in less NIMBYism and greater community support.

Visual factors

The visual preference (VPS) block of the survey examined if there is a difference in stakeholder preferences for three overarching architecture styles: traditional (vernacular), non-traditional (modern), and tiny houses on wheels (THOWs). The three categories were based on prior VPS research which examined generalised preferences for tiny houses. In this study, the architecture categories were revisited in order to examine if preferences changed when the housing was intended for homeless persons. It was anticipated that the results might differ due to the fact that efforts to aid the homeless are frequently patronising (Daly, Citation2013; Schneider & Remillard, Citation2013). The COO of the Eden Village case site summarised the tendency of addressing homelessness in a way that suggests the poor are somehow less deserving:

Some places have volunteers come and they serve meals for the homeless, food they’d (the volunteers) would never eat themselves. They (the volunteers) stand behind like a wall, window thing, and dish out the food, which shows they are somehow not on the same level. When they are all done, (volunteering) they go home and eat something totally different, something that actually tastes good. That is how we (Eden Village) are different, we treat them (homeless persons) just like us. If volunteers want to serve a meal, they are welcome and that’s great. But we require that they sit down and eat the meal with all of us, get to know our residents. We believe in running this place like we would want to live here. That’s how we chose our housing units. We want them to be houses that people go in and say, ‘This is great, I’d live in one of these.’ (Nate Schlueter, interview by author, 18 December 2018)

Figure 3. This photograph of a tiny home built in a traditional architecture style had the highest rating in the VPS. Developers of tiny house villages for the homeless may want to take this preference into account (Photo permission granted: Texas Tiny Houses).

Figure 4. The block that examined stakeholder preferences for tiny houses on wheels (THOWs) rated the lowest in the VPS. Advocates of tiny house villages for the homeless may want to take this preference into account and build tiny homes on foundations (Photo permission granted: Mint Tiny Homes).

Table 2. Architectural style descriptive statistics.

Apart from the VPS portion of the survey, other visual elements related to stakeholder preferences for tiny house villages for the homeless were examined using descriptive statistic analysis of 5-point Likert scale responses. In instances where over half or 50% of respondents indicated that their preferences were positively linked to a visual element (for example by choosing ‘Positively influenced a little’ (4) or ‘Positively influenced a great deal’ (5) or ‘I like it’ (4) or ‘I like it very much’ (5) on the Likert scale, the element has been noted as a positively influential visual factor ‘+’ (). In instances where the results were not as definitive (less than half or 50% of respondents), the factor has been recorded as neutral ‘n’. In no instance did over 50% of respondents indicate that a visual factor generated negative perceptions. Each of these visual factors has the potential to be examined with greater precision using VPS instrumentation and is a limitation of the research. Three visual factors related to especially high preference levels are porches, (83.0% positive), the presence of landscaping, (81.6%) and foundation-built tiny homes (75.0%). Integrating these visual elements into villages may result in less NIMBYism and greater acceptance ().

Figure 5. The lowest ranking image in the VPS was for this modern style tiny home. Not only has the research resulted in a finding of greater stakeholder preference for traditional architecture, but for such elements as porches, landscaping, and painted bevelled wood siding, all of which this particular unit lacks (Photo permission granted: Kaiserworks LLC).

Table 3. Descriptive statistic analysis of visual features related to tiny houses in tiny house villages for the homeless.

Physical and social factors

Using the same descriptive statistics method described for visual elements, the physical and social factors related to tiny house villages for the homeless were also analysed. Perhaps unsurprisingly, every factor, with the exception of one, was found to positively influence stakeholder perceptions of tiny house villages for the homeless (meaning over 50% of respondents indicated a factor as positively influential). The factor that did not have a majority (greater than 50% of respondents) of positive associations, was for a tiny house community for the homelessness built in one’s own neighbourhood. This again suggests perceptions of NIMBYism that may impact the integration of these type of developments.

Overall, however, the survey revealed that stakeholder preferences increased with the offering of physical and social amenities such as heating and cooling in individual units and mental health services. Interestingly, the national tiny house database found that in several tiny house communities for the homeless, such amenities are not offered (Evans, Citation2020). For example, as of July 2019, 59% of tiny houses villages had no plumbing in individual units, only 38% had kitchens in individual units, 18% had neither heat or air-conditioning, and 9% had no electricity. In many instances, communal facilities were built in lieu of amenities in individual units. For example, 69% of tiny house villages had communal showers and 81% had communal kitchens (though a limited number of villages offered a mix of communal and individual unit offerings). It is likely that the lack of amenities or the provision of communal amenities is to keep costs down, and perhaps some feel that a roof over one’s head is better than none. However, the literature, especially that which focuses on the housing first approach and the needs of the chronically disabled, indicates that supportive amenities are needed in addition to physical housing (Coleman, Citation2018; Jackson et al., Citation2020; Padgett et al., Citation2016; Segel, Citation2015). The Eden Village case site COO stated,

Some tiny home communities build community really well, some are just glad to get people with a roof over their head, even if it is more like a storage shed, maybe power and no water and no bathroom. At the end of the day that might be a roof over somebody’s head, but it’s still, it’s one step up from a cardboard box. So, it’s not a home, no one wants to live without running water or bathrooms for the rest of their life. (Nate Schlueter, interview by author, 18 December 2018)

Yet as this research finds NIMBYism perceptions towards tiny house villages for the homeless, it important for communities to address the factors that increase such resistance. The results of this study indicate that stakeholders have increased preferences for, and therefore, may be more supportive of tiny house villages for the homeless that offer supportive physical and social amenities ().

Table 4. Descriptive statistic analysis of physical and social features related to tiny houses in tiny house villages for the homeless.

The survey showed positive stakeholder preferences for tiny house villages for both the veteran and general homeless population. It was hypothesised that the provision of tiny housing for veterans would be a positively influencing factor, and members of the general homeless population would rate as a neutral factor. This was not the case. The veteran category did score higher overall, with 83.6% of participants positively influenced by the factor, but the general homeless category also scored high at 76.9%. The results indicate positive associations with tiny house villages for the homeless being used to house both populations.

Implications: combating NIMBY perceptions through tiny house village design

The research has resulted in a better understanding of stakeholder perceptions of, and preferences for, tiny house villages that serve the homeless. It finds that NIMBYism may serve as a deterrent to these villages, yet stakeholders have distinct preferences for specific aspects of tiny house villages for the homeless. The findings of this study raise interesting questions when synthesised with the lessons learned from housing affordability policy over the last several decades.

Low-income housing developments are generally more successful in terms of neighbourhood and resident outcomes when they are integrated into the urban fabric rather than glaringly distinct (Bothwell et al., Citation1998; Brophy & Smith, Citation1997; Duke, Citation2009; Yancey, Citation1971). For example, high rise public housing associated with Urban Renewal policy in the U.S. has been found to lead to a myriad of issues including concentrated poverty and stigmatisation of residents (Austen, Citation2018; Yancey, Citation1971). As a result, there has been significant movement among advocates to integrate such housing into neighbourhoods in the form of non-distinct and scattered units (Brophy & Smith, Citation1997; Duke, Citation2009).

Though these lessons have been learned in the realm of public and government-sponsored housing, there is evidence that efforts championed by the media and popular sentiment may not have yet developed this understanding. In London, for example, a group of well-known architects recently built a temporary, or ‘pop-up’ four-storey housing unit for the homeless with a facade of bright multi-colour panels. Though celebrated on social media, the development is clearly out of place with the surrounding urban fabric in terms of both the building placement and façade, and residents indicate that they are watched, judged and stigmatised as a result (Harris et al., Citation2019). The rise of tiny house villages to address homelessness may raise a similar flag of concern for some homelessness advocates. Due to the distinct nature of a ‘village’, these developments become visible pockets of housing for a community’s poorest residents. This may lead to the problematic issues associated with high-rise public housing. In this research, the survey results that suggest NIMBYism is the greatest deterrent to these developments, supports such a finding. Residents do not want a manifestation of concentrated poverty in their backyard.

However, tiny house villages are increasingly being utilised as a method of addressing homelessness. Increasing neoliberal policy worldwide begs that the private market find solutions to problems formerly addressed by public coffers. Tiny houses are popular and therefore an attractive and growing means to address homelessness. Whether they will result in the stigmatisation and concentrated poverty issues associated with low-income housing projects is an area ripe for investigation. This particular study finds however, that when tiny house villages are the chosen approach to addressing homelessness, stakeholders prefer traditional architecture rather than modernist or mobile units. This suggests a desire for housing units within villages themselves to be reflective of typical, unobtrusive and tried and true housing forms rather than distinct, experimental or unusual architecture. In this way, stakeholder preferences align with the housing literature that finds distinct units to be stigmatising to residents (Bothwell et al., Citation1998). The findings of this study have resulted in the development of ‘best practices’ for integrating tiny house villages into communities. It is hoped that the following strategies will aid those aiming to address homelessness through the development of tiny house villages.

Design tiny house villages for the homeless to foster a supportive sense of community. This includes individual homes, village site design, and the provision of amenities for a supportive community framework

The survey revealed that stakeholder preferences for tiny house villages increased with the offering of supportive amenities such as community centres, transportation services, and mental health services. This is likely due to the growing recognition that many people experiencing homelessness have problems that are unlikely to be solved from merely being housed. The open-ended survey question included several comments about the need for a supportive community framework in order that villages succeed in helping residents, including:

If the Tiny House Community allows for other services, such as a wellbeing centre, mental health help and maybe classes on life skills it will help them up and not down.

[Need to] provide community resources, close to medical help and services for it [the village] to succeed.

The use of tiny homes to help people who are homeless, provide healthcare/mental health services, and provide job/life skills training, is a great way to improve our communities and help those around us.

The obvious solution to homelessness is a person needs a home, but they need more than a home, they need community. Homelessness is a catastrophic loss of community or family (Dr. David Brown personal interview by author, 18 December 2018).

Furthermore, management at the case site locations suggests that certain design elements were specifically integrated into the built environment to lead to a greater sense of community. For example, the Director of the VCP case site stated that the integration of community gardens was an important means of creating a sense of contribution to the village (Josh Henges, interview by author, 10 December 2020). The COO at Eden Village noted that manufactured units with porches were specifically chosen as porches facilitate interaction with neighbours:

We wanted something with a front porch, and we wanted all the porches to face the street so the neighbours, so if you walked down the street people will come out of their porch and wave at you, they will talk to their neighbours porch to porch. (Nate Schlueter, interview by author, 18 December 2018)

Encourage tiny house villages for the homeless to be built in a traditional (vernacular) architecture style

The survey found a statistically different and higher preference for tiny houses in tiny house villages for the homeless built in a traditional rather than modern architecture style. This finding supports the literature which contends that affordable housing should not be built in such a distinct way that it causes residents to be stigmatised (Duke, Citation2009; Yancey, Citation1971). Perhaps this preference for traditional architecture is rooted in associations with stability and middle-class lifestyles. Policy makers and tiny house villages advocates may want to take this preference into account as another method for tacking potential opposition. For example, communities that have a design review board may want to create architectural and design criteria that would require the individual tiny homes in these developments to be of a traditional style. Furthermore, they may want to encourage units to have their own bathrooms and kitchens, basic tenets of the typical and stable middle-class home. The current trend among tiny house villages for the homeless to utilise communal showering and kitchen facilities may not only result in resident stigmatisation, but does not foster occupant needs for independence and privacy. Communities may be more receptive to tiny house communities for the homeless if they are built in a traditional architectural style and integrate the amenities standard to the typical home.

Require tiny house villages for the homeless to be built on foundations, rather than on wheels

The survey instrument also revealed a significantly different and lower preference for THOWs over the other two visual preference blocks. This is likely a result of concerns over how THOWs might impact the surrounding community in terms of potentially mobile neighbours and property valuation. Because they are not foundation built, THOWs may be considered a depreciating asset, similar to a recreational vehicle (RV) (Hart et al., Citation2003). This could result in decreased property values in an area, something that this study and prior tiny house research has found to be major concern of stakeholders (Evans, Citation2018, Citation2021). THOWs may also lead to negative associations with trailer or mobile home parks, and the social issues of poverty that often plague them.

Survey participants indicated considerable support for tiny houses in tiny house villages for the homeless to be built on foundations, and apprehension about THOWs. Though THOWs are associated with the tiny house movement itself, it is recommended that tiny house villages for the homeless be built on foundations rather than wheels to allay potential NIMBY concerns. This would not be difficult to accomplish in most communities, as foundation-built homes are a requirement in the vast majority of zoning categories and under numerous building codes. Finding places to legally integrate THOWs is a much greater challenge (Evans, Citation2018). Instead of putting significant effort into finding a site that would allow for THOWs, such as rezoning for a campground designation that may or may not ultimately classify THOWs as RVs, it is suggested that tiny houses in tiny house villages for the homeless be built on foundations. It is likely that such integration will result in greater community support.

Research limitations and future research

The research design is cross-sectional or conducted at a point in time. As a new and rapidly emerging means of addressing homelessness, it is likely that barriers, strategies, and perceptions of tiny house villages for the homeless will change with time. Therefore, the study lacks longevity, where a phenomenon is studied over a longer period of time. Also, the scope of the research is exploratory due to the recentness of tiny house villages for the homeless. Therefore, the factors examined in the survey were not exhaustive of all the visual, physical, and social elements that might impact stakeholder preferences. Furthermore, each influencing factor could be explored with greater detail and precision.

This research does not examine resident outcomes. It remains to be seen if tiny house villages might not only prove a solution to housing people experiencing homelessness, but if they will be a success in terms of resident outcomes. Future research that explores various measures of ‘success’ such as length of time residents remain housed, substance abuse abstinence and employment outcomes is warranted. Furthermore, investigation into specific factors that may or may not influence resident ‘success’, such as resident perceptions of their homes, the provision of specific amenities, methods of community governance, and short-term vs. permanent housing regimes is needed. If tiny house villages make a positive impact on the lives of great numbers of people experiencing homelessness, support for these developments may increase. Therefore, research that identifies, isolates, and measures specific elements related to successful resident outcomes is warranted.

Conclusion

Tiny house villages are increasingly being used as a housing strategy for homelessness, yet these villages face barriers to being integrated into the urban fabric. This research finds that NIMBY sentiment towards tiny house villages for the homeless is prevalent among stakeholders. As issues of social equity and inclusion are increasingly at the forefront of societal concerns, it is hoped that such NIMBY sentiments are reassessed and challenged. In the meantime, the research findings also offer hope for advocates of tiny house villages for homeless persons. It finds that stakeholders have distinct preferences in relation to tiny house villages for the homeless. Integrating such preferences into future tiny house villages for the homeless may result in greater community support and less opposition to these developments. The study allows for a greater understanding of how tiny house villages for the homeless are perceived by stakeholders. It contributes to the housing literature through the development of strategies that may allow tiny house villages for the homeless to be accommodated in a way that is perceived positively among communities. It is hoped that the findings and strategies aid advocacy efforts towards providing housing to homeless persons.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abarbanel, S., Bayer, C., Corcuera, P., & Stetson, N. (2016). Making a tiny deal out of it: A feasibility study of tiny house villages to increase affordable housing in Lane County. University of California, Berkeley, Goldman School of Public Policy.

- Anderson, M. (1964). The federal bulldozer. A critical analysis of urban renewal, 1949–1962. Cambridge: M.I.T. Press.

- Austen, B. (2018). High-risers: Cabrini-green and the fate of American public housing. HarperCollins.

- Bothwell, S. E., Gindroz, R., & Lang, R. E. (1998). Restoring community through traditional neighborhood design: A case study of Diggs town public housing. Housing Policy Debate, 9(1), 89–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.1998.9521287

- Brophy, P. C., & Smith, R. N. (1997). Mixed-income housing: Factors for success. Cityscape, 3(2), 3–31.

- Brown, M. M., Jason, L. A., Malone, D. K., Srebnik, D., & Sylla, L. (2016). Housing first as an effective model for community stabilization among vulnerable individuals with chronic and nonchronic homelessness histories. Journal of Community Psychology, 44(3), 384–390. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21763

- Byrne, T., Munley, E. A., Fargo, J. D., Montgomery, A. E., & Culhane, D. P. (2013). New perspectives on community-level determinants of homelessness. Journal of Urban Affairs, 35(5), 607–625. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2012.00643.x

- Caton, C. L. (1990). Homeless in America. Oxford University Press.

- Coleman, R. (2018). Are tiny houses useful and feasible to help address homelessness in Alameda County?: How could tiny houses be used, and under what conditions? (Client Report). Diss. University of California Berkeley.

- Daly, G. (2013). Homeless: Policies, strategies and lives on the streets. Routledge.

- Dear, M. J., & Wolch, J. R. (2014). Landscapes of despair: From deinstitutionalization to homelessness (Vol. 823). Princeton University Press.

- Dear, M. J., & Gleeson, B. (1991). Community attitudes toward the homeless. Urban Geography, 12(2), 155–176. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.12.2.155

- Desmond, M. (2016). Evicted: Poverty and profit in the American city. Broadway Books.

- Duke, J. (2009). Mixed income housing policy and public housing residents’ right to the city. Critical Social Policy, 29(1), 100–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018308098396

- Ewing, R., King, M. R., Raudenbush, S., & Clemente, O. J. (2005). Turning highways into main streets: Two innovations in planning methodology. Journal of the American Planning Association, 71(3), 269–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360508976698

- Evans, K. (2018). Overcoming barriers to tiny and small home urban integration: A comparative case study in the carolinas. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X18788938

- Evans, K. (2019). Exploring the relationship between visual preferences for tiny and small houses and land use policy in the southeastern United States. Land Use Policy, 81, 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.10.051

- Evans, K. (2020). Tackling homelessness with tiny houses: An inventory of tiny house villages in the United States. The Professional Geographer, 72(3), 360–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2020.1744170

- Evans, K. (2021). It takes a tiny house village: A comparative case study of barriers and strategies for the integration of tiny house villages for homeless persons in Missouri. Journal of Planning Education and Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X211041392

- Fowler, F. (2017). Tiny homes in a big city. Cass Community Publishing House.

- Groat, L., & Wang, D. (2002). Architectural research methods. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Groth, P. E. (1994). Living downtown: The history of residential hotels in the United States. University of California Press.

- Harris, E. (2019). Compensatory cultures: Post-2008 climate mechanisms for crisis times. New Formations, 99(99), 66–87. https://doi.org/10.3898/NewF:99.04.2019

- Harris, E., & Nowicki, M. (2020). “GET SMALLER”? Emerging geographies of micro‐living. Area, 52(3), 591–599. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12625

- Harris, E., Nowicki, M., & Brickell, K. (2019). On-edge in the impasse: Inhabiting the housing crisis as structure-of-feeling. Geoforum, 101, 156–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.001

- Hart, J. F., Rhodes, M. J., & Morgan, J. T. (2003). The unknown world of the mobile home. Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Heben, A. (2014). Tent city urbanism: From self-organized camps to tiny house villages. The Village Collaborative.

- Hope, M., & James, Y. (1986). The politics of displacement: Sinking into homelessness. In J. Erickson & C. Wilhelm (Eds.), Housing the homeless (pp. 106–112). The State University of New Jersey.

- Jackson, A., Callea, B., Stampar, N., Sanders, A., De Los Rios, A., & Pierce, J. (2020). Exploring tiny homes as an affordable housing strategy to ameliorate homelessness: A case study of the dwellings in Tallahassee, FL. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2), 661. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020661

- Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge University Press.

- Kasinitz, P. (1984). Gentrification and homelessness: The single room occupant and the inner city revival. Urban and Social Change Review, 17(1), 9–14.

- Keable, E. (2017). Building on the tiny house movement: A viable solution to meet affordable housing needs. U.St.Thomas JL & Pub.Pol’Y, 11, 111.

- Lamb, H. R. (1984). Deinstitutionalization and the homeless mentally ill. Hospital & Community Psychiatry, 35(9), 899–907. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.35.9.899

- Lees, L., Slater, T., & Wyly, E. (2008). Gentrification. Routledge.

- LeGates, R. T., & Hartman, C. (2013). The anatomy of displacement in the United States. In N. Smith and P. Williams, (Eds.), Gentrification of the city, 194–219. Routledge.

- Lyon‐Callo, V. (2001). Making sense of NIMBY poverty, power and community opposition to homeless shelters. City & Society, 13(2), 183–209.

- Mitchell, D. (2011). Homelessness, American style. Urban Geography, 32(7), 933–956. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.32.7.933

- Nasar, J. L. (1998). The evaluative image of the City. Sage Publications.

- National Alliance to End Homelessness. (2018). The state of homelessness in America. Retrieved May 2, 2018, from https://endhomelessness.org/homelessness-in-america/homelessness-statistics/state-of-homelessness-report/

- Nelessen, A. C. (1994). Visions for a new American dream. Planners Press, American Planning Association.

- Oakley, D. (2002). Housing homeless people: Local mobilization of federal resources to fight NIMBYism. Journal of Urban Affairs, 24(1), 97–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9906.00116

- O’Regan, K. M., & Quigley, J. M. (2000). Federal policy and the rise of nonprofit housing providers.

- Padgett, D., Henwood, B. F., & Tsemberis, S. J. (2016). Housing first: Ending homelessness, transforming systems, and changing lives. Oxford University Press.

- Schneider, B., & Remillard, C. (2013). Caring about homelessness: How identity work maintains the stigma of homelessness. Text & Talk, 33(1), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1515/text-2013-0005

- Schwartz, A. F. (2014). Housing policy in the United States. Routledge.

- Segel, G. (2015). Tiny houses: A permanent supportive housing model. Community Frameworks Development Services.

- Speer, J. (2017). “It’s not like your home”: Homeless encampments, housing projects, and the struggle over domestic space. Antipode, 49(2), 517–535. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12275

- Stamps, A. E. (2000). Psychology and the aesthetics of the built environment. Kluwer Academic.

- Tighe, J. R., & Mueller, E. J. (2013). The affordable housing reader. Routledge.

- Tsemberis, S., & Eisenberg, R. F. (2000). Pathways to housing: Supported housing for street-dwelling homeless individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 51(4), 487–493. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.51.4.487

- Turner, C. (2016). It takes a village: Designating tiny house villages as transitional housing campgrounds. University of Michigan Journal of Law Reform, 50(50.4), 931. https://doi.org/10.36646/mjlr.50.4.it

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2007). Defining chronic homelessness: A technical guide for HUD programs. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Office of Community Planning and Development.

- Wolch, J. R., Dear, M., & Akita, A. (1988). Explaining homelessness. Journal of the American Planning Association, 54(4), 443–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944368808976671

- Wright, J. (2017). Address unknown: The homeless in America. Routledge.

- Yancey, W. L. (1971). Architecture, interaction, and social control: The case of a large-scale public housing project. Environment and Behavior, 3(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/001391657100300101