Abstract

After decades of battling the quantitative and qualitative housing deficits, Latin American countries are seeing new types of challenges in housing. Neoliberal policies favouring individual (low-cost) homeownership have weakened social trust and solidarity between neighbours, and some housing areas face poor urban amenities. An example of this is Chile, where housing policy measures have brought adverse effects such as deteriorating housing quality and the relocation of families to peripheral areas. This has caused the breakdown of family ties, community life, and social cohesion. Although various studies on the housing deficit in Chile have been carried out, these studies have not comprehensively addressed the multiple dimensions of housing. Therefore, this review explores how Chilean housing policies have addressed the housing deficit from four dimensions: quantitative, qualitative, urban, and social. To this end, we reviewed Chilean housing policies and programmes and their response to the housing deficit from the neoliberal period onwards. We found that these policies and interventions have focused on solving the quantitative and, to a lesser extent, qualitative and urban deficits while sparsely addressing the non-physical or intangible social dimension. We conclude this article with recommendations to address the social deficit of housing in future policies.

Introduction

In recent decades, the housing deficit has become a global problem that has increased significantly (BID, Citation2018; Monkkonen, Citation2013) and extended to multiple dimensions. There is a quantitative deficit in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC), which refers to the lack of numerical supply of houses produced for the current population (MINVU & CEHU, Citation2009). There is also a qualitative deficit regarding the lack of physical quality (Ducci, Citation2009). Of the urban population in LAC, 6% are homeless, 94% of homes have qualitative deficits, and 30% live in overcrowding (CEPAL, Citation2021). Chile is not alien to this situation, as the total quantitative deficit reached 641,421 homes in 2021 (Déficit Cero, Citation2022), and more than 1.2 million homes need to be qualitatively improved (DIPRES, Citation2020).

Governments in LAC have focused on developing housing policies to combat this deficit (ONU-Habitat, Citation2015). Nevertheless, these policies have shown deficiencies since implementation (Fuster-Farfán, Citation2021). Moreover, new challenges have emerged beyond quantitative deficits (Monkkonen, Citation2018). These challenges extend to social problems, including social exclusion and overcrowding (Rodríguez & Sugranyes, Citation2005) and urban problems related to the lack of public spaces, infrastructure and urban amenities (Monkkonen, Citation2018). A focus on the quantitative deficit, albeit essential to tackle, could neglect other dimensions of the housing deficit. Therefore, we recognise that the housing deficit is a multi-dimensional phenomenon comprising four dimensions: quantitative, qualitative, urban, and social.

Although many researchers have studied the housing deficit, there have not been studies on how policies address all of these four dimensions. This policy review explores how housing policies and programmes in Chile have addressed the multi-dimensional challenges of the housing deficit. We present this review in three sections. First, we show an overview of Chile’s housing policies. Second, we define the deficits and their indicators. Finally, we present our findings on how policies have addressed the housing deficit from a multi-dimensional perspective.

Background: understanding housing provision and policies in Chile

Chile has a long history of housing policies and programmes focused on addressing the housing deficit. From the first Workers’ Rooms Ordinance of 1906 onwards, the state held a producing role and mainly regulated construction and rental prices (Hidalgo, Citation2005). From the ‘40 s, the first slums and land takeovers emerged due to rural-urban migration leading to increasing demand (Rodríguez & Sugranyes, Citation2005). In response, the state changed its logic towards a policy of quantitative interventions, incorporating the private market and boosting housing production. From the 1960s onwards, the state’s objective was to replace informal housing with subsidised housing located in the periphery (Hidalgo, Citation2005).

From the ‘70 s, the period of a facilitating role and neoliberal state began (Gilbert, Citation2002), with Chile being the first country to implement this regime. The new intrinsic ideology became that the private market was considered to be more efficient in housing production than the state, marking a radical policy change (Fuster-Farfán, Citation2021). Thus, housing was commodified, and a subsidiary system was created for vulnerable inhabitants. From 1979, land was not considered a scarce good, and land use was deregulated (Tapia, Citation2011). Subsequently, policies privileged quantity over quality (Fuster-Farfán, Citation2019).

This subsidiary model was maintained during the following decades, significantly reducing the quantitative deficit (Ruiz-Tagle et al., Citation2021). This model was considered successful in Chile and replicated in LAC (Lentini, Citation2005). Towards the end of the 1990s, the policy showed signs of exhaustion and was no longer capable of satisfying housing needs, leading to a housing crisis of quality and location (Tapia, Citation2011). Since 2000, policies have made a ‘qualitative turn’ (Fuster-Farfán, Citation2021). In 2006, the Urban-Housing Policy was implemented to improve construction quality, building location and fight social exclusion through social integration policies and participatory methodologies. However, despite these interventions, policies did not change structurally (Fuster-Farfán, Citation2019).

In the last 15 years, exceptional interventionsFootnote1 have become frequent, and some have been considered good practices regarding inhabitant participation, location, and quality. However, these exceptions have depended on the stakeholders’ capacity and not on housing policies (Fuster-Farfán, Citation2021).

A multi-dimensional perspective on the housing deficit in Chile

The housing deficit or shortage in LAC academic literature is understood as ‘the multiplicity of deficiencies associated with aspects necessary for an adequate housing quality’ (Sepúlveda et al., Citation2005, P. 20). This deficit is diverse, complex and coexists with social problems such as socio-spatial inequality (Santoro, Citation2019). Thus, focusing interventions only on the quantitative and qualitative deficits is insufficient. To address structural inequalities, policy solutions must respond to different dimensions and social contexts (Lentini, Citation2005). We, therefore, analyse the housing deficit comprising four dimensions: quantitative, qualitative, urban and social.

The quantitative and qualitative deficits are relatively easy to measure through indicators related to physical characteristics. However, this is difficult for urban and social deficits because some aspects lack quantifiable indicators. In this paper, we employ an initial framework and indicators of the dimensions to analyse whether policies address these deficits in Chile.

Quantitative and qualitative deficits

International literature shows that the definitions of quantitative and qualitative deficits and their components have been widely discussed (Marcos et al., Citation2018). There seems to be a consensus on the general ideas of both concepts. Monkkonen (Citation2013) states that the qualitative deficit estimates the number of homes below normative quality standards. The quantitative deficit calculates the availability of homes in relation to the number of current households. In the Chilean case, both deficits are intertwined.

In 2004, the Ministry of Housing and Urbanism (MINVU) proposed three categories of housing: acceptable, recoverable and irrecoverable homes. In analogy with this distinction, we refer to the quantitative deficit as ‘the number of exclusive homes that need to be produced to satisfy the housing needs of the current population’. This includes irrecoverable homesFootnote2 and families living in allegamientoFootnote3 or hacinamientoFootnote4 (Déficit Cero, Citation2022). In line with the LAC definitions (BID, Citation2018), we understand the qualitative deficit as the ‘lack of quality of the construction material and availability of basic services such as drinking water, electricity and sewerage’. This corresponds to recoverable homes that need constructive improvements or a connection to basic services (MINVU, Citation2004b). Indicators for these deficits are shown in .

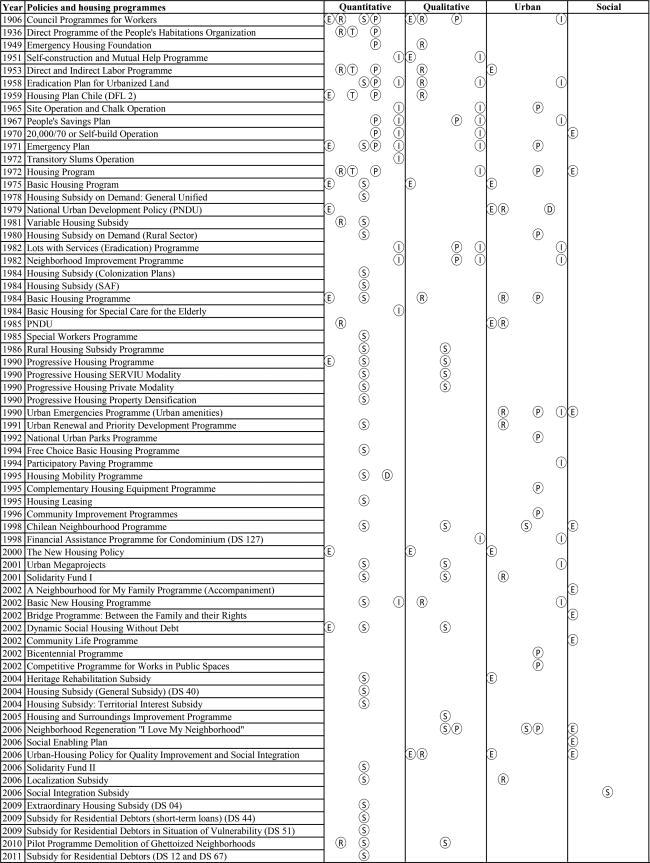

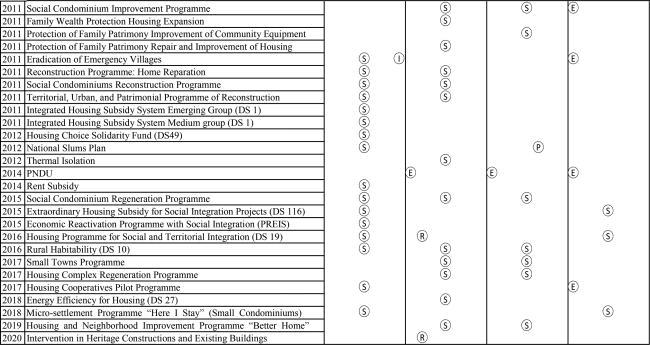

Table 1. Dimensions of housing deficit and indicators.

Urban deficit

In LAC, neoliberal housing policies have displaced families from informal settlements to the periphery, segregating inhabitants (Gilbert, Citation2002). In the global context, housing solutions have produced similar problems, such as a lack of infrastructure, public spaces and urban amenities (Monkkonen, Citation2018). In 2009 in Chile, the MINVU and the Housing and Urban Studies Commission (CEHU) stated the existence of an urban housing deficit defining it as a ‘set of urban and housing deprivations that significantly affect the residential development and the quality of life of the population’. In addition, the Inter-American Bank (BID), in 2018, proposed that qualitative problems extend to the city’s attributes available to the inhabitants.

In analogy with the previous approaches, we refer to the urban deficit as ‘the lack of availability of urban spaces, infrastructure and access to amenities that contribute to the quality of life in residential areas’. The concept of the urban deficit is still a challenge in the methodological and conceptual construction (MINVU & CEHU, 2009). This is because adequate variables and indicators are not yet available to measure it in its full complexity (Garay et al., Citation2020). For this policy review, we propose indicators, such as the accessibility of homes to urban spaces and amenities ().

Social deficit

In Chile, relocating households from different origins to new settlements has caused socio-spatial segregation and the breakdown of original social ties (Rodríguez et al., Citation2018). The same pattern is visible in Brazil, Colombia (Santoro, Citation2019) and Argentina (Lentini, Citation2005), when inhabitants of informal housing reject new homes located on the periphery to maintain their prior social fabric (Beswick et al., Citation2019, P. 12). Relocated families experience feelings such as isolation, weakened solidarity (Castillo & Hidalgo, Citation2007) and lack of social cohesion and community life (Wormald & Sabatini, Citation2013). The underdevelopment of these social aspects is what we propose to call the Social Deficit of Housing (SDH).

Paidakaki and Lang (Citation2021) explain that although housing is considered a physical resource, it also includes a non-physical social dimension. According to Borja (Citation2018, P. 245), ‘housing is something more than housing; it is the place to live together (…) and build social ties’. Based on this, we refer to the SDH as the ‘lack of non-physical or intangible aspects such as the feeling of integration and social cohesion at the local level of the neighbourhood or building’. This social dimension shows similarities to the concept of social sustainability, which focuses on the physical and non-physical dimensions of the social structures of communities (Janssen et al., Citation2021) and therefore has similar indicators.

We propose SDH indicators, including elements of social sustainability such as sense of community, social networking and interactions. We also include bonding social capital (Woolcock, Citation2002), trust, solidarity and neighbourhood attachment (Méndez et al., Citation2021). In addition, we include neighbourhood social cohesion, defined by the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (CEPAL) in 2022 as ‘the capacity of a society to (…) generate a sense of belonging and an orientation towards the common good’.

Methods: classification of policy options in addressing the housing deficit

This policy review explores the response of policies to the housing deficit, loosely adapting the criteria and analysis model from Weimer and Vining (Citation2017). First, we reviewed European, LAC, and Chilean literature to understand the problem. Our review was of a scoping nature as we rapidly mapped key concepts of the housing deficit (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). Inclusion criteria were that the publications focused on the housing deficit or our four dimensions in Spanish and English. Based on this review, we identified definitions for the deficits and analysis indicators.

Second, we established a timeline (from 1906 to the present) of the policies based on policy documents from the MINVU (Citation2004a) complemented with available publications from Chilean housing academics, e.g., Hidalgo (Citation2005) and Greene and Mora (Citation2020). Third, we analysed the nature of Chilean policies using our indicators, starting from 1970, the policies’ neoliberal turning point onwards. We classified policy objectives using our indicators as keywords to see whether a policy responds to a deficit. We reviewed secondary literature from the aforementioned authors to verify our classification and avoid bias. Finally, we formulated recommendations to tackle the SDH.

For this analysis, we understand policy using Doling’s (Citation1997) definition as ‘the reaction of governments to problems, such that the objective is to increase the well-being [or] welfare (…) of the citizens.’ Additionally, we adapted Doling’s policy action classification framework to the Chilean context as follows.

Exhortation (E): Exhort individuals and organisations to behave in ways consistent with their policy aims, e.g., publicity campaigns, educational or resident support workshops.

Regulation (R): Regulation of a specified behaviour, e.g., standards of construction or behaviour.

Taxation (T): Taxes on goods and services whose consumption the government wants to reduce, e.g., tax on sales, property or income, expropriations of land.

Subsidy (S): The reverse of taxation, e.g., voucher, subsidy, tax benefit.

Provision (P): Direct provision of goods or services, e.g., land or house allocation.

Based on Doling’s suggestion of adapting policy options to specific housing contexts, we chose not to include Non-action, as we were interested in the policies that did address housing deficits. Additionally, we added two policy actions, Deregulation and Partial provision, as they also occur in Chile. Examples are the National Urban Development Policy (PNDU) in 1979 and the Eradication programme (1982). We define these actions as follows:

Deregulation (D): Eliminate regulations, e.g., land limits for urban expansion.

Partial provision (I): Partial provision of goods or services, e.g., part of the home or urban amenities developed by the state.

An example of our analysis is the following. We analysed the 2006 Neighbourhood Regeneration Programme (Appendix A). First, we used the proposed indicators, e.g., social or urban amenities, as keywords to review the policy objectives. Second, we analysed the programme’s objective, e.g., ‘recover deteriorated public spaces, improve environmental conditions, strengthen social relations and promote more integrated neighbourhoods’, and the actions proposed for each dimension of the deficit. In this case, the policy proposed specific actions for qualitative, social and urban deficits, e.g., construction of urban amenities, improvement of basic services and collective spaces, and training for residents. Then, using Doling’s framework, we classified these actions in the qualitative and urban dimensions as Subsidy (S) and Provision (P) since the programme’s objective is to improve the quality of the services and urban amenities. Also, some actions are classified as Exhortative (E) in the social dimension since the programme provides workshops for the residents to strengthen neighbourhood networks and community life. We repeated this process for each housing programme and policy.

Findings: housing deficits and policy options addressed in Chilean policies

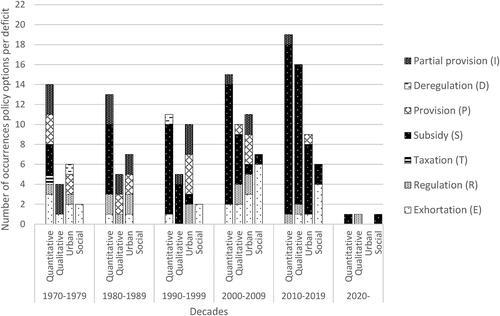

We analysed housing policies in Chile for if and how they address the four deficits defined in the previous sections. shows the number of occurrences of policy actions per deficit for every decade since 1970. Appendix A shows the complete timeline of the Chilean policies and our classification of the policy actions.

Quantitative and qualitative deficits

Since their first interventions, housing policies in Chile have focused on reducing the quantitative deficit. Appendix A shows that policy programmes mainly regulated (R) the liveability of the homes and partially (I) and fully (P) provided housing. As shown in , since the 1970s, policies have taken a neoliberal turn, in which interventions change from a provision (P) to a subsidiary system (S). Under this neoliberal ideology, policies focused on achieving economic efficiency (Peñafiel, Citation2021) and maximum densification through industrialised production (Beswick et al., Citation2019). Since the 2000s, policies have changed from quantitative to qualitative approaches to improve homes’ quality and basic services. This change began in 2006 with the I Love My Neighbourhood programme. From this period until now, the qualitative dimension has been addressed through subsidies (S) and, to a lesser extent, partial provision (I) and regulations (R).

Our analysis shows that Chilean policies have significantly addressed both deficits in the last 30 years. This is in line with the Urban Quality of Life Survey (CEHU, Citation2018), which shows that a population sample’s perception of housing quality has increased from 74% to 81% between 2015 and 2018, based on interviews and questionnaires. However, policies still dictate minimal quality standards followed to the minimum by real estate developers (Imilan, Citation2016). This system causes rapid deterioration of homes, reducing their useful life.

Although housing programmes have improved housing conditions, it is still not considered a constitutional right, and policies try to correct problems on the fly without making structural changes (Fuster-Farfán, Citation2021). Therefore, recognising housing as a rightFootnote5 and improving the quality of homes still requires attention.

Urban deficit

Policies have created plans to regulate (R) and fully (P) or partially (I) provide urban amenities. shows that the provision of public spaces (P) has occurred more frequently since the 1990s. Later, towards the 2000s, these urban programmes were varied (I, S and P) and responded to the new approach of minimising the deterioration of cities and generating equipped neighbourhoods (PNDU, Citation2014). Since the proposal by MINVU & CEHU to consider the urban dimension as part of the deficit in 2009, policies focused on granting subsidies (S) to improve urban facilities.

Our review shows policies’ progress in addressing the urban deficit. However, the inhabitants still perceive urban problems, such as the lack of accessibility to urban amenities and insecurity in public spaces MINVU (2018). Also, there is a lack of integration and dialogue between urban and housing programmes. These problems cannot be improved substantially if homes and the neighbourhood are not considered an integrated system (Tapia et al., Citation2019).

Social deficit

Housing policies have tried to respond to what we call the SDH (). However, these attempts have been primarily symbolic. The Self-build Operation Programme for assisted self-construction from the 1970s encouraged (E) collective housing production by residents (Beswick et al., Citation2019). While this contributed to strengthening the social fabric of communities, the government at the time eliminated the programme. In the 1980s, although social aspects such as strengthening social networks were mentioned in some collective application programmes, there was no tangible action. In the 1990s, policies mostly responded to this deficit through exhortative solutions, including resident training (MINVU, Citation2004a).

Since the 2000s, social aspects such as cohesion, integration and social mix have become more frequent in policy narrative. However, the programmes’ response has been of a similar nature (E) while including subsidies to a lesser extent (S). One of this period’s exceptional programmes was the Chilean Neighbourhood Programme from 1998, which incorporated support for integrating families into their new homes (E) (Fuster-Farfán, Citation2019). Currently, policy approaches have been chiefly exhortative (E) and, to a lesser extent, subsidiary (S).

A study on social capital by MINVU (Citation2004a) showed that about 20% of surveyed households felt a lack of identity, trust and neighbourly relationships. Furthermore, families expressed the need to strengthen community ties and neighbourhood identity (Castillo and Hidalgo (Citation2007) with tools that facilitate organisation and coexistence (Peñafiel, Citation2021). Our analysis shows that although exceptional interventions subtly addressed the social dimension, the necessary support tools to build a sense of community and neighbourhood social cohesion have not been developed yet.

Conclusions and recommendations

This policy review explored how housing policies in Chile have addressed the housing deficit from a multi-dimensional perspective. From the policy analysis presented here, we conclude that despite government efforts, housing policies still lack structural changes and do not treat housing as a multi-dimensional phenomenon. Although the dimensions have been treated independently, an integrated policy approach is still lacking. In summary:

Policies have mostly addressed quantitative housing demands. However, the focus has been on efficiency and minimum cost, neglecting other housing dimensions.

Although there has been a qualitative turn in policies, the associated solutions have been exceptional and have not been part of structural changes in the policies.

Housing policies have progressed in addressing the urban dimension, but urban programmes remain independent from housing, maintaining socio-spatial segregation.

The social dimension of housing has been partially included in the policy narrative but sparsely addressed by policy actions. The associated actions have not been of a practical nature but mostly symbolic and exhortative.

In conclusion, this review indicates that policies have focused on solving quantitative and, to a lesser extent, qualitative and urban deficits while sparsely addressing the non-physical or intangible social dimension. Practically addressing social aspects is relevant for housing policies since neglecting this dimension could increase homes’ and neighbourhoods’ social and physical degradation. Our recommendations to address the social deficit are twofold.

First, we suggest that policies consider housing in its multi-dimensionality since housing problems are not solved only by giving the inhabitants a house but by considering comprehensive solutions that adapt to different geographical contexts and needs. Including a social dimension could lead Chilean housing policies to help achieve a cohesive society and social sustainability.

Second, we suggest strengthening the social dimension by creating participatory tools and exploring new housing models. Some national examples of participatory programmes are the Housing Cooperatives Pilot from 2017 and the Micro-settlement ‘Here I Stay’ from 2018. In these projects, residents are integrated into housing development by local governments. An international example is Collaborative Housing (CH), a form of self-managed housing where residents collectively produce homes by collaborating with stakeholders (Lang et al., Citation2020). Some examples of CH are housing cooperatives in Uruguay, Argentina, and Spain and Community Land Trusts in Central America (Davis et al., Citation2020). Exploring these models and tools could contribute to integrally addressing the housing deficit and its social dimension in Latin America and Chile.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback.

Disclosure statement

The authors reported no potential conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Alternative governance strategies that oppose standard policies resulting from the pressure of resident movements (Fuster-Farfán, Citation2021).

2 Homes that require replacement (MINVU, Citation2004b).

3 Living arrangement known in English as doubled-up, where multiple households coexist within one home (Fuster-Farfán, Citation2021).

4 Occurs when more than 2.5 people per bedroom live in a home (Déficit Cero, Citation2022).

5 Currently, housing is part of the constitutional debate (Vergara-Perucich et al., Citation2020).

6 The names of each policy were translated from Spanish into English by the authors.

References

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Beswick, J., Imilan, W., & Olivera, P. (2019). Access to housing in the neoliberal era: A new comparativist analysis of the neoliberalisation of access to housing in Santiago and London. International Journal of Housing Policy, 19(3), 288–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2018.1501256

- BID. (2018). Vivienda ¿Qué Viene?: De Pensar la Unidad a Construir la Ciudad, https://doi.org/10.18235/0001594

- Borja, J. (2018). La vivienda popular, de la marginación a la ciudadanía. In Con Subsidio, Sin derecho.

- Castillo, M., & Hidalgo, R. (2007). 1906-2006. Cien años de politica de vivienda en Chile. Universidad Andres Bello.

- CEHU. (2018). 4° Encuesta de Calidad de Vida Urbana.

- CEPAL. (2021). Panorama Social de América Latina 2020. Naciones Unidas. https://doi.org/10.22201/fesa.rdp.2021.3.06

- CEPAL. (2022). Cohesión social en Chile en tiempos de cambio. Indicadores, perfiles y factores asociados. (J. Castillo, V. Espinoza, & E. Barozet (eds.)).

- Davis, J., Algoed, L., & Hernández, M. E. (2020). La inseguridad de la tenencia de la tierra en américa latina y el caribe. El control comunitario de la tierra como prevención del desplazamiento.

- Déficit Cero. (2022). Déficit Habitacional: ¿Cuántas Familias Necesitan una Vivienda y en qué Territorios?

- DIPRES. (2020). Informe final de evaluación de Programas Gubernamentales: Fondo Solidario de Elección de Vivienda DS 49. 248.

- Doling, J. (1997). Comparative housing policy. Government and housing in advanced industrialised countries.

- Ducci, M. E. (2009). La política habitacional como instrumento de desintegración social. Efectos de una política de vivienda exitosa. 293–310.

- Fuster-Farfán, X. (2019). Las políticas de vivienda social en chile en un contexto de neoliberalismo híbrido. EURE (Santiago), 45(135), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0250-71612019000200005

- Fuster-Farfán, X. (2021). Exception as a government strategy: Contemporary Chile’s housing policy. International Journal of Housing Policy, 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2021.1910784

- Garay, R., Contreras, Y., Díaz, J., Herrera, R., & Tapia, R. (2020). Propuestas para repensar las viviendas y el habitar Chile. Universidad de Chile.

- Gilbert, A. (2002). Power, ideology and the Washington Consensus: The development and spread of Chilean housing policy. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267303022012324

- Greene, M., & Mora, R. (2020). Hábitat residencial.

- Hidalgo, R. (2005). La vivienda social en Chile y la construcción del espacio urbano en el Santiago del siglo XX.

- Imilan, W. (2016). Políticas y luchas por la vivienda en Chile el camino neoliberal. In Contested cities. http://repositorio.uchile.cl/handle/2250/141198

- Janssen, C., Daamen, T. A., & Verdaas, C. (2021). Planning for urban social sustainability: Towards a human-centred operational approach. Sustainability, 13(16), 9083. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13169083

- Lang, R., Carriou, C., & Czischke, D. (2020). Collaborative housing research (1990–2017): A systematic review and thematic analysis of the field. Housing, Theory and Society, 37(1), 10–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2018.1536077

- Lentini, M. (2005). Política habitacional de Argentina y Chile durante los noventa. Un estudio de política comparada. Revista INVI, 20(55), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.5354/0718-8358.2005.62166

- Marcos, M., Di Virgilio, M. M., & Mera, G. (2018). El déficit habitacional en Argentina. Una propuesta de medición para establecer magnitudes, tipos y urgencias de intervención intra-urbana. Revista Latinoamericana de Metodología de Las Ciencias Sociales, 8(1), e037. https://doi.org/10.24215/18537863e037

- Méndez, M. L., Otero, G., Link, F., López Morales, E., & Gayo, M. (2021). Neighbourhood cohesion as a form of privilege. Urban Studies, 58(8), 1691–1711. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098020914549

- MINVU. (2004a). CHILE: Un Siglo de Políticas en Vivienda y Barrio.

- MINVU. (2004b). El déficit habitacional en Chile. Medición de requerimientos de vivienda y su distribución espacial.

- MINVU, & CEHU. (2009). Déficit Urbano-Habitacional: una mirada integral a la calidad de vida y el hábitat residencial en Chile.

- Monkkonen, P. (2013). Housing deficits as a frame for housing policy: Demographic change, economic crisis and household formation in Indonesia. International Journal of Housing Policy, 13(3), 247–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2013.793518

- Monkkonen, P. (2018). Do we need innovation in housing policy? Mass production, community-based upgrading, and the politics of urban land in the Global South. International Journal of Housing Policy, 18(2), 167–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2017.1417767

- ONU-Habitat. (2015). Déficit habitacional en América Latina y el Caribe: Una herramienta para el diagnóstico y el desarrollo de políticas efectivas en vivienda y hábitat.

- Paidakaki, A., & Lang, R. (2021). Uncovering social sustainability in housing systems through the lens of institutional capital: A study of two housing alliances in Vienna, Austria. Sustainability, 13(17), 9726. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179726

- Peñafiel, M. (2021). El proyecto residencial colectivo en Chile. Formación y evolución de una política habitacional productiva centrada en la noción de copropiedad. Revista de Geografía Norte Grande, 236(78), 215–236. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-34022021000100215

- PNDU. (2014). Hacia una Nueva Política Urbana para Chile: Política Nacional de Desarrollo Urbano. http://cndu.gob.cl/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/L4-Politica-Nacional-Urbana.pdf

- Rodríguez, A., Rodríguez, P., & Sugranyes, A. (eds). (2018). Con Subsidio, Sin derecho. La situación del derecho a una vivienda adecuada en Chile. Ediciones SUR.

- Rodríguez, A., & Sugranyes, A. (2005). Los con techo. Un desafío para la política de vivienda social. Ediciones SUR.

- Ruiz-Tagle, J., Valenzuela, F., Czischke, D., Cortés-Urra, V., Carroza, N., & Encinas, F. (2021). Propuestas de política pública para apoyar el desarrollo de cooperativas de vivienda autogestionarias en Chile. In Propuestas para Chile. Concurso de Políticas Públicas UC (pp. 145–172).

- Santoro, P. F. (2019). Inclusionary housing policies in Latin America: São Paulo, Brazil in dialogue with Bogotá, Colombia. International Journal of Housing Policy, 19(3), 385–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2019.1613870

- Sepúlveda, R., Martínez, L., Tapia, R., Jirón, P., Zapata, I., Torres, M., & Poblete, C. (2005). Mejoramiento del parque habitacional. Universidad de Chile, Facultad de Arquitectura y Urbanismo, Instituto de la Vivienda.

- Tapia, Araos, C., Forray, R., Gil, D., & Muñoz, S. (2019). Hacia un modelo integral de regeneración urbano-habitacional con densificación en barrios tipo 9x18. In Propuestas para Chile. Concurso Políticas Públicas UC (pp. 319–351).

- Tapia, R. (2011). Social housing in Santiago. Analysis of its locational behavior between 1980-2002. Revista INVI, 73, 105–131. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-83582011000300004

- Vergara-Perucich, F., Aguirre, C., Encinas, F., Truffello, R., & Ladrón de Guevara, F. (2020). Contribución a la economía política de la vivienda en Chile.

- Weimer, D., & Vining, A. (2017). Policy analysis: Concepts and practice. (6th ed.). Routledge.

- Woolcock, M. (2002). Social capital in theory and practice: Where do we stand? Social Capital and Economic Development: Well-being in developing countries, 1(2), 18–39. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781781950388.00011

- Wormald, G., & Sabatini, F. (2013). Segregación de la vivienda social: reducción de oportunidades, pérdida de cohesión. In Segregación de la vivienda social: ocho conjuntos en Santiago, Concepción y Talca (pp. 266–298).

Appendix A

Appendix A. Overview of housing policies addressing housing deficits.Footnote6 Source: Authors.