Abstract

Community Led Housing (CLH) is an umbrella term encompassing several non-profit models of housing delivery, which is used internationally. There has been little comprehensive assessment of the health impacts of housing arrangements where people intentionally live or work together in a community. This systematic review provides the first overview of the health, wellbeing and heath inequality impacts of all forms of CLH. 4,091 literature items were identified from a structured search of eight databases and manual searching for grey literature. Literature published between January 2009 and June 2022, in OECD countries, were eligible. 34 academic and 11 grey literature items were included. The review identifies far more literature reporting that CLH has positive rather than negative impacts, on primary health outcomes and on neighbourhood level factors which impact on health (social contact, employment, safety, environmental sustainability, and affordability). There is a lack of research on CLH impacts on the health of children and young people, and on health inequalities. These findings provide an indication of largely positive impacts of CLH arrangements on health and wellbeing. They indicate the importance of further longitudinal, objective research, and of policies and actions to support this form of housing delivery.

KEYWORDS: :

Introduction

There is extensive evidence demonstrating the importance of housing as a wider determinant of health, and of health inequalities (Ige et al., Citation2019; WHO, Citation2018). However, currently, 1.6 billion people, or 20% of the world’s population, live in inadequate, crowded and unsafe housing (Woetzel et al., Citation2014). In high-income countries, around 70% of people’s time is spent inside their home, and in some places, including where unemployment levels are higher and where more people are employed in home-based industries, this percentage is even higher (WHO, Citation2018). Not only does this have significant implications on the occupants’ lives but for wider health and social care systems too (Garrett et al., Citation2021).

The impact of the design and quality of homes on the health of occupants has been widely reported for numerous outcomes including cardiorespiratory diseases, infectious diseases, injuries, allergies and mental health conditions (Ige et al., Citation2019; WHO, Citation2018). Causal pathways have shown how housing can impact on health. These pathways can be used to infer how risk factors at the building level (e.g., ventilation and space), the neighbourhood level (e.g., proximity to green space, local facilities and public and active transport options) and through direct exposures (e.g., cold or air pollutants) (Bird et al., Citation2018; Pineo et al., Citation2018), can have health impacts. As well as physical environments, psychosocial environments (e.g., affordability, safety, environmental sustainability, and social contact) play a role in health outcomes (Bird et al., Citation2018; Ige et al., Citation2019; WHO, Citation2018). These causal pathways underpin the methods of this paper.

To date, there has been little comprehensive assessment of the health impacts of housing arrangements where people intentionally live or work together in a community (Lubik & Kosatsky, Citation2019).

Community Led Housing definition

Community Led Housing (CLH) is an umbrella term encompassing several non-profit models of housing delivery. While the CLH movement is diverse, for the purpose of this review we have used the following definition: CLH is housing development which meets the following three criteria (Co-operative Councils Innovation Network, Citation2018):

A requirement that meaningful community engagement and consent occurs throughout the process. The community does not necessarily have to initiate and manage the development process, or build the homes themselves, though some may do.

The local community group or organisation owns, manages or stewards the homes in a manner of their choosing.

A requirement that the benefits to the local area or specified community must be clearly defined and legally protected in perpetuity.

Within this definition of CLH, there are a range of ownership, management and occupancy models, which may have very different funding or governance structures. These include (Co-operative Councils Innovation Network, Citation2018):

Housing co-operative: groups of people who provide and collectively manage, on a democratic membership basis, homes for themselves as tenants or shared owners.

Cohousing: groups of like-minded people who come together to provide self-contained, private homes for themselves, but manage their scheme together and share activities, often in a communal space. Cohousing can be developer-led, so it is important to examine whether cases meet the broad definition of CLH given above, rather than simply use of the term cohousing as a marketing device.

Community Land Trust (CLT): not-for-profit corporation that holds land as a community asset and acts as the long-term steward, which can provide housing through rent or shared-ownership.

Community self-build: groups of local people in housing need building homes for themselves with external support and managing the process collectively. Individual self-build is not regarded as CLH.

Self-help housing: small, community-based organisations bringing empty properties back into use, often without mainstream funding and with a strong emphasis on construction skills training and support.

Tenant-Managed Organisations (TMO): provide social housing tenants with collective responsibility for managing and maintaining the homes through an agreement with their council or housing association landlord. This category, similar to (developer-led) cohousing, is contested and needs specific case by case consideration to deem tenant management a meaningful form of community control.

These models are not necessarily mutually exclusive, a cohousing group could form a CLT or a co-operative, as could a TMO. Further, any of the types listed above could be self-built. Some forms of CLH may also be ‘intentional communities’, a group of people who have chosen to live together with a common purpose, working co-operatively to create a lifestyle that reflects their shared core values, often involving shared resources and responsibilities, but equally, intentional communities may not engage with CLH. The sector is complex, evolving and differs between contexts and countries. These definitions aim to illustrate what is in the scope of CLH, and how it is different from market-driven or standard (welfare-oriented) social housing, rather than provide a set of discrete categories into which each CLH development could be exclusively placed.

Historical and policy context

CLH has a long history, with roots in the co-operative movement of the nineteenth century, where housing co-operatives were at the core of Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City Movement, which had influence globally (Goulding et al., Citation2018). This was followed by the CLT movement in the United States (US) in the 1960s, which was intertwined with struggles for land-based racial justice (Bates, Citation2022). The bulk of the current stock of CLH is attributable to housing co-operatives formed in the 1970s and 1980s (Goulding et al., Citation2018), largely in Denmark, Sweden, Germany and the Netherlands. Subsequently there was a small wave of CLH in other western countries (Ruiu, Citation2016). Whereas in those early years most projects were isolated events, since 2000 a trend has emerged and CLH now exists worldwide, including in developing countries (CAHF, Citation2022).

CLH has experienced increased attention in recent years (Jarvis, Citation2015; Moore & McKee, Citation2012; Mullins, Citation2018; Tummers, Citation2016), which has been attributed to a couple of key factors. The first relates to a shortage in affordable housing and precarious rental conditions (Moore & McKee, Citation2012; Mullins, Citation2018), which is widely cited as a ‘housing crisis’. The second factor relates to a more ideological position. Literature refers to a growing desire for a sense of belonging, a need to feel connected to a community, and an increasing rejection of dominant models of consumption (Jarvis, Citation2015).

Previous reviews have considered a single aspect of CLH, such as cohousing (Carrere et al., Citation2020), or a single health outcome, such as social networks (Warner et al., Citation2020). These found that the majority of studies found CLH to be health promoting. To our knowledge, no systematic review has yet been undertaken analysing the entirety of links between CLH and health and wellbeing. Therefore, the aim of this review was to gather and synthesise all of the evidence, from an international context, on the relationships between all forms of CLH and any health and wellbeing outcomes, including health inequalities.

Methods

Search strategy

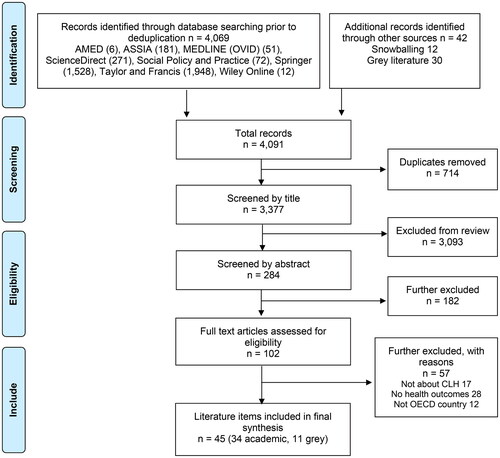

A list of potentially relevant databases and organisations was compiled from existing systematic reviews across similar topics (Ige et al., Citation2019). Eight electronic databases related to a variety of fields, including health, architecture, ageing and social sciences, were used to conduct the search; Taylor and Francis, Social Policy and Practice, Wiley Online, ScienceDirect, Springer, MEDLINE (OVID), The Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), and Applied Social Sciences Index & Abstracts (ASSIA), were searched. To ensure we obtained evidence from a broad range of sources the search strategy included grey literature as well as academic databases. We searched 14 grey literature sources (see ). Additional searches were conducted by Rachael McClatchey on Google, Google Scholar and relevant organisation websites to locate additional potentially eligible literature. All authors were involved in identifying relevant grey literature. To ensure we did not miss key papers we also used a snowballing technique, which involves scanning the reference list of included papers to check for any relevant sources that may have been overlooked.

Table 1. Example search protocols for academic databases and for grey literature.

Search run in August 2019, and again in June 2022

Preliminary searches were used to gain depth of understanding, as to whether our initial search process needed further refining. The authors considered including a range of additional search terms on secondary outcomes, such as physical and psychosocial housing factors with evidence of impact on health, and on population sub-groups (Ige et al., Citation2019; WHO, Citation2018). As the preliminary searches identified a limited number of sources relating to the primary outcome of health, the authors decided not to apply this secondary level of search terms (see for search terms). To ensure the authors gathered the most relevant possible range of results, US and United Kingdom (UK) spelling terms, truncations, wildcards, and Boolean terms were used. A pilot search was performed by Emma Griffin in one database (Taylor and Francis) to test the search strategy and refine the search terms before the full search was undertaken by the same researcher.

Eligibility criteria

Articles were screened in three phases: title, abstract, and full-text. To be selected for inclusion, literature items were required to meet the following inclusion criteria:

Be published in English language (literature not in English language were excluded due to limited capacity to translate within the research team).

Be published between 1st January 2009 to 30th June 2022 (as CLH grew in momentum from 2000 on, the authors did not anticipate much literature published prior to this date).

Be conducted in OECD countries (literature from countries outside OECD were excluded from this review due to differences in planning systems and regulations, general economic circumstances and levels of informal housing, which may act as confounders) (Shrestha et al., Citation2021).

No restriction of study design. Evidence reviews were excluded but checked for additional eligible literature. The following types of grey literature are eligible: reports, dissertations, policies, conference abstracts, presentations, expert opinion, video and text accessible from nationally recognised stakeholder websites.

Reports on associations between:

Population: people of any age or sex involved in or affected by CLH, including residents, prospective residents, visitors, those involved in the construction process, board members and/or the local community. Literature on informally settled or travelling communities was not included.

Exposure: CLH; the authors adopted the definition as agreed by the CLH sector (see introduction for definition). Intentional communities were only included if they also fulfilled a definition of CLH, so intentional communities such as residential treatment facilities were excluded.

Outcome: the primary outcomes of interest were health and wellbeing impacts, secondary outcomes were risk factors with evidence of impact on health at building or neighbourhood level (including the physical or psychosocial environment).

Search results

Results were exported to referencing software Zotero, and duplicates were removed. Emma Griffin independently screened all titles and abstracts identified by the searches, removing literature which did not meet the eligibility criteria. A selection of the literature was then independently assessed by a second reviewer to ensure consistency and accuracy in the selection process (McClatchey).

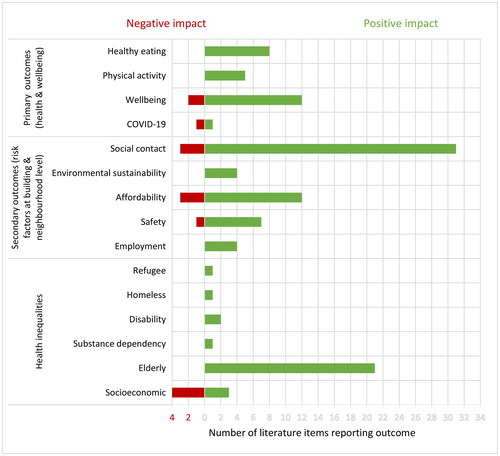

In total, 4,091 literature items were identified from a structured search of eight databases combined with manual searching for grey literature. 714 duplicates were removed prior to screening. A total of 45 literature items met the eligibility criteria and were included in the review (see , and and ). Of these, 34 were academic studies (13 mixed methods, 18 qualitative, and three quantitative) and the remaining 11 were grey literature (one briefing, one commentary, one book chapter, two policy reviews, four reports, one workshop reflection, and one blog).

Figure 1. Flow diagram showing search results, and literature selection process. Community Led housing, health and wellbeing: a Comprehensive literature review, 2023.

Table 2. Characteristics and findings of included academic literature (n = 34).

Table 3. Characteristics and findings of included grey literature (n = 11).

Data extraction

Two reviewers (McClatchey and Griffin) extracted relevant data on: author, publication date, location, type of CLH, funding, study design, methods, participants including sub-populations, and negative and positive impacts on health (primary outcome) and physical and psychosocial housing factors with evidence of impact on health (secondary outcome). Data and themes were reviewed jointly with Katie McClymont. The reporting of this review conforms to recommendations from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA, Citation2020).

Quality appraisal

As the search identified quantitative, qualitative and mixed method studies, the quality assessment Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Hong et al., Citation2018) was used to rate the quality of included literature. This tool was selected for its ability to assess a range of study designs. The tool consists of screening questions followed by five quality assessment domains depending on the study methodology. The tool is recommended for rating the methodological quality of literature, and its reliability (Souto et al., Citation2015) and content validity (Hong et al., Citation2019) has been corroborated.

As the search also included grey literature, the quality assessment AACODS checklist was used to rate the quality of these literature items, in line with previous systematic reviews containing grey literature (Tyndall, Citation2010). This tool was selected for its ability to assess a range of literature types, and as it is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, Citation2014). The tool has been recommended for rating the methodological quality of literature based on construct validity and acceptable content. The tool consists of six quality assessment domains: Authority; Accuracy; Coverage; Objectivity; Date; and Significance.

The quality of included literature was assessed by McClatchey, with 10% (selected using a random number generator) of the literature independently assessed by McClymont to check for consistency. The authors did not exclude literature on the basis of quality, and we provide a commentary on the type and quality of the literature included in this review in the Discussion section.

Data synthesis

Given the heterogeneity in the study design, study populations, measurements, and outcomes, the authors developed a narrative synthesis of the results. For each piece of literature, the authors summarised the study characteristics and described the positive and negative associations observed between CLH and health (see and ). Key topics were identified in each paper (see ), and these were then refined to clusters, which are presented and discussed below. The authors then organised the findings under the original primary and secondary outcome headings, with an additional cluster emerging on health inequalities.

Results

Study characteristics

The rate of publication of literature ranged throughout the included period, with the majority (53%) being published between 2015 and 2019. The UK (40%), followed by the US (25%) were the most common geographical locations of studies. Australia, Austria, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden also had literature identified.

The majority of literature focussed on a single form of CLH, with only nine (20%) of studies including all or multiple forms of CLH. Cohousing was the most commonly studied type of CLH, accounting for 24 (53%) of included studies. The number of CLH cases within a study ranged from one to 127, with most literature items (61%) including multiple case studies. Across all included literature, there was a total of 284 CLH cases examined.

All of the literature included residents or prospective residents of CLH as study participants. In addition, some studies included developers, architects, housing association staff, local authorities, and community groups. There were at least 5,240 participants across all included literature, with a further two studies where the total sample size was unclear.

Key themes

Findings consistently showed positive associations between all forms of CLH and a range of health impacts, with a very small number reporting negative health impacts (see and and ). This applied to primary outcomes (health and wellbeing) and secondary outcomes (risk factors at building and neighbourhood level), largely regardless of country or CLH housing type.

Primary outcomes: health and wellbeing

Physical health

There were a number of studies that referenced a positive relationship between CLH and physical health, and no studies which identified physical health harms. The relationship between CLH and physical health was expressed through increased physical activity (n = 4), and healthy eating behaviours (n = 8).

Glass (Citation2013) reported an increase in physical activity as a result of residents encouraging each other to exercise. Additionally, in the CSBA and UWE’s (Citation2016) study of a community self-help project, the residents reported increased levels of physical fitness as a result of the labour involved in constructing their homes.

Glass (Citation2009), Theriault et al. (Citation2010), Ruiu (Citation2016), CSBA and UWE (Citation2016), and Izuhara et al. (Citation2021), all suggested that living in a CLH project contributed towards improved relationships to food and healthier eating habits. The participants reported that their involvement in the project led to them collectively cooking and eating more nutritious meals. Garciano (Citation2011) also identified that opportunities for organic gardening, joining healthy eating initiatives, and regular common meals all contributed.

Mental health and wellbeing

Housing and mental health are closely linked, with evidence linking a range of housing factors to stress, anxiety and depression, sleep disorders, and relationship difficulties (Ige et al., Citation2019; WHO, Citation2018). The majority of included literature reporting on mental health outcomes identified positive impacts (n = 12). All of these reported on wellbeing as the outcome, with one study also suggesting that CLH led to feelings of increased confidence (Dang & Seemann, Citation2020). Conversely a small number of studies did identify negative impacts on wellbeing (n = 2), reporting that residents found it hard to have privacy (Coele, Citation2014; Glass, Citation2013). None of the studies have identified links to diagnosed mental health conditions.

COVID-19

One study (Izuhara et al., Citation2021) specifically considered the health impacts of CLH through the COVID-19 pandemic. They found that there were ambiguous definitions of ‘households’ associated with CLH communities when interpreting the lockdown rules to provide mutual aid and support, and that many communities restricted themselves to individual household use of communal space on a pre-arranged basis, to avoid interaction. Others found significant evidence of mutual support among CLH members both in practical terms but also in terms of social contact (Scanlon et al., Citation2021).

Secondary outcomes: risk factors at building and neighbourhood level

Five risk factors at the neighbourhood level through which CLH impacts on health were identified, all of which were psychosocial factors. No risk factors at the building level (such as ventilation and space), or through direct exposures (such as cold or air pollutants) were identified.

Social contact

By far the greatest impact identified in the literature was on social contact, with 33 literature items reporting positive impacts. Evidence shows social contact and environments which are supportive of this has short and long-term effects on health, including health behaviours, and mental and physical health outcomes (Bird et al., Citation2018; Umberson & Montez, Citation2010; WHO, Citation2018). Studies suggested that CLH led to increased feelings of belonging, inclusion, and less loneliness, and that these positive findings remained whilst controlling for personal and household characteristics (Clever Elephant, Citation2019; Dang & Seemann, Citation2020; Ruiu, Citation2016; Van den Berg et al., Citation2021). Participants of CLH felt a strong sense of community, for example through new social networks, enhanced relationships with neighbours, volunteering, or cultural events (Garciano, Citation2011; Glass, Citation2009; Sanguinetti, Citation2014; Scanlon et al., Citation2021). Support with day-to-day tasks such as cooking, informal childcare and gardening, provided increased social capital (Garciano, Citation2011). The sharing of responsibilities and resources in cohousing contributed to what Jarvis (Citation2015) identified as group solidarity. Lang and Novy (Citation2014) found that professional co-operative structures give residents a voice, and improve social cohesion and residents’ sense of autonomy.

Conversely a small number of studies did identify negative impacts on social inclusion (n = 3). Garciano (Citation2011) found limited diversity of the cohousing resident population, in terms of socioeconomic background, ethnicity, and language. For example, even when interested in participating, low-income residents, who often need to work in multiple jobs, had little time and energy to invest in the wider community. Similarly Lubik and Kosatsky (Citation2019) found a few studies have demonstrated that some residents opt out of communal living in less than a year, citing either too much or not enough social interaction.

Affordability

Affordable housing has been linked to better health, especially for vulnerable groups (including adults with intellectual disability or chronic conditions, substance users, and people experiencing homelessness) through engagement with health services, reduced stress, reduced overcrowding, and more income being available to support health and wellbeing through spending on healthy food, utilities, and healthcare, therefore, leading to improved mental and physical health (Bird et al., Citation2018; WHO, Citation2018).

There is an assumption in policy discourse that CLH is an affordable model of housing. However, as CLH does not follow a single funding or governance structure; the extent to which this is true varies across the type of CLH, the context within which they exist, and whether the initial build or ongoing lifecycle of the housing is being considered. 13 literature items found that CLH could produce affordable housing, with four of these discussing all forms of CLH, four specifically referencing CLTs, and a further four on cohousing. This was compared to three literature items which found the contrary, two of which questioned the affordability of cohousing, and one on CLTs.

Self-help housing may reduce the costs of external builders and contractors, and co-operatives or CLTs may cross-subsidise, acquire grants, or partner with housing associations or local authorities making the initial build process affordable. (Clever Elephant, Citation2019; Dang & Seemann, Citation2020; Hackett et al., Citation2018; Martin et al., Citation2019). Cohousing may enable resident households to benefit from substantial increases in housing equity (Labit & Dubost, Citation2016; Ruiu, Citation2015; Wang et al., Citation2021), whilst co-operatives, and CLTs can explicitly limit such accumulation in order to preserve ongoing affordability (Schneider, Citation2022). Scanlon and Arrigoitia (Citation2015) reported greater risk and uncertainty in the build process, and often lengthier construction times, meaning new cohousing was not necessarily cheaper than conventional new builds. Similarly, Weeks et al. (Citation2019) found that due to the shared costs of common areas, the overall cost per owner is not reduced compared to conventional builds, and that residents were not able to identify any funding to support the costs of development, building or the ongoing operation of cohousing.

Employment

Four studies found that being involved in CLH led to greater employment prospects, which in turn brings beneficial health impacts, especially for vulnerable groups such as people experiencing homelessness, and leads to improved mental and physical health outcomes (Bird et al., Citation2018; WHO, Citation2018). Mullins (Citation2018) found self-help communities gave participants new skills and work experience, which in turn led to greater employment prospects.

Safety

Seven studies found CLH created an environment which felt safe and gave residents a sense of security. Perception of safety has been linked to better health, especially for low-income groups, in part through physical activity, leading to improved mental and physical health outcomes (Bird et al., Citation2018). However, Rosenberg (Citation2012) found residents of a TMO were more likely to feel unsafe being out after dark and showed a lesser degree of trust in their neighbours than those in non-community housing.

Environmental sustainability

Lastly, studies found CLH supported environmentally sustainable living (n = 4). Climate change is inextricably linked with health outcomes (WHO, Citation2018), for example, energy efficient homes have been linked to better health, leading to improved mental and physical health outcomes, especially reduced asthma (Bird et al., Citation2018). Wang et al. (Citation2021) specified mechanisms, including reduced food purchase, joint travel, sustainable technologies, and energy efficiency design, construction methods and materials.

Health inequalities

32 literature items included consideration of the impact of CLH on health inequalities, which ranged across protected characteristics, vulnerable population groups and socioeconomic considerations.

14 literature items focussed on a particular population sub-group, with elderly (aged 50 years or older) people accounting for 11 of these. A further 10 literature items, which did not target a specific sub-population, also acknowledged positive impacts on the health of older people. Cohousing has been suggested to maintain independence and support ageing in place, delaying or mitigating the need for people to move into care homes (Kehl & Then, Citation2013; Lubik & Kosatsky, Citation2019). Glass (Citation2009) found that in cohousing residents were able to support older people in the community with social care, rather than being dependent on family members, and that this took place outside traditional working hours. Social care generally referred to support with shopping, cooking, and companionship, and did not extend to personal care tasks such as bathing, dressing and toileting (Izuhara et al., Citation2021). However, it was noted that cohousing provided an opportunity to house overnight assistants, or to exchange accommodation for personal care from trained professionals (Coele, Citation2014). Labit and Dubost (Citation2016) found that intergenerational community housing projects in France and Germany reduced health and social care costs both to individuals and the state. Additionally, a small body of literature discussed the wider benefits of designing communities with older people in mind, such as adapting physical design features to ensure they are accessible to residents throughout the ageing process (Glass, Citation2013, Citation2016).

Other sub-groups included people who have a disability (Coele, Citation2014; Stevens, Citation2016), have experienced homelessness (Heslop, Citation2017), drug or alcohol dependency (CSBA & UWE, Citation2016), and refugees (Czischke & Huisman, Citation2018). The main themes in these studies was that CLH can promote inclusion and independence for vulnerable sub-populations. For example, studies suggested that less hierarchical structures of care giving and receiving contributed to improved quality of life for people living within the community with a learning disability (Stevens, Citation2016) or physical disability (Coele, Citation2014). Homeless veterans who had encountered alcohol or drug dependency reported that the self-build gave them a sense of achievement, increased confidence and a sense of trust (CSBA & UWE, Citation2016). Lastly, Czischke and Huisman (Citation2018) studied a single CLH project, which provided homes for 565 refugee and Dutch people between the ages of 18 and 27. Living in the CLH community provided residents with access to education, employment opportunities and social connections. The findings suggest that the housing project is successful in supporting the integration of refugees into Dutch society.

Many studies discussed here have found CLH benefited socioeconomically deprived groups (Dang & Seemann, Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2021; Warner et al., Citation2022), however given the heterogeneity in funding and governance structures of CLH it is difficult to draw conclusions. Some studies have observed unequal access to CLH and limited diversity within the resident populations, with people from disadvantaged backgrounds appearing to have fewer opportunities to access CLH and thus less chance to benefit from potential positive health effects (Garciano, Citation2011; Lubik & Kosatsky, Citation2019; Moore & McKee, Citation2012; Schneider, Citation2022). Therefore, there is a possibility that CLH could have the undesirable effect of leading to increased health inequalities if consideration is not given to access of this form of housing.

Schneider (Citation2022) conducted a large cross-sectional study which found that CLTs were associated with improved financial wellbeing and increased housing stability. However, the study also proposed that CLTs may limit wealth accumulation for those populations most in need of acquiring wealth: those with low incomes, people from Black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds, and female-headed households.

Discussion

In this review the majority of included literature was academic, consisting of observational studies using mainly qualitative or mixed method. These research methods cannot prove causality, nevertheless our findings demonstrate an emerging picture of largely positive links between both the primary outcome (health), and the secondary outcomes (psychosocial housing factors). CLH may be particularly beneficial for people with support needs. The findings warrant further assessment by researchers as set out below.

Evaluating CLH more rigorously could establish stronger links between CLH and health, thereby encouraging public and private investors, policymakers, as well as potentially interested residents worldwide, to consider this model of housing as a means of improving public health.

Strengths and limitations

A key strength of this review is the robustness and rigour of the methods applied. Our systematic approach to collating and assessing the quality of existing evidence against building and neighbourhood features as well as primary health outcomes has enabled the identification of knowledge and research gaps, from an emergent evidence base, on the complex link between CLH and health.

Grey literature and non-experimental studies are at greater risk of bias. The grey literature included in the synthesis comprised seven items of high quality (ACCODS score of 5 or 6), four items of moderate quality (ACCODS score of 3 or 4) and no items of low quality (ACCODS score of 2 or less). Generally items scored lower for being from potentially biased sources, such as third sector organisations promoting CLH, or for having unclear aims or parameters which define their content coverage, so may report only on the most extreme findings. It is not recommended to report scores with the quality assessment MMAT, so the most noteworthy limitations of included academic literature are described below (Hong et al., Citation2018).

Many studies in this review either did not adequately report recruitment methods, or encountered challenges with recruitment. For example, Theriault et al. (Citation2010) attempted random recruitment but a low acceptance rate meant they had to widen their approach. Glass (Citation2016) use a convenience sample at a CLH dinner hall, where not everyone participated. It is possible that those most supportive of CLH were more likely to participate. Thus selection bias may have occurred. Some studies provided little information regarding who carried out the research, and few studies have quantitatively assessed health outcomes, with the majority that did using small scale surveys. The majority of studies rely on self-reported data to measure behaviours and practices among CLH residents. Therefore, studies may be affected by social desirability bias or inaccurate recall by participants. The exceptions are Hackett et al. (Citation2018) who linked datasets from time of purchase and property stock with a survey, and Schneider (Citation2022) who included administrative data. Thus response bias may have occurred. Publication bias may be present if literature about CLH that showed neutral or negative results were less likely to have been submitted or accepted for publication.

We found six studies that drew comparisons between CLH and non-community housing (Kehl & Then, Citation2013; Lang & Novy, Citation2014; Markle et al., Citation2015; Scanlon et al., Citation2021; Schneider, Citation2022; Van den Berg et al., Citation2021). All but one (i.e., Schneider, Citation2022), identified only positive health impacts, which remained when controlling for confounders. These generally included age, sex, marital status, education level, language, and ethnicity, with Van den Berg et al. (Citation2021) additionally including household composition, income, car ownership, employment status, home-ownership, club or organisation memberships, participation in voluntary work and neighbourhood density. Van den Berg et al. (Citation2021) used Structured Equation Modelling, which allowed them to analyse confounding and mediating pathways, and to incorporate both latent variables and observed variables.

Across included studies, participants tended to be middle aged and older, and often older than the control groups, and whilst there were intergenerational studies, none of them explicitly assessed health outcomes in children and young people. Kehl and Then (Citation2013) found people aged 66–89 years accounted for approximately half of the participants in the programme group. Similarly, Scanlon et al. (Citation2021) identified the highest number of participants in the cohort aged 60–69 years. The mean age of programme group participants was 43.7 years (Schneider, Citation2022), or 70.51 years (Van den Berg et al., Citation2021). Lang and Novy (Citation2014) noted across study groups 67–75% of included households had no children in them, and 68% of participants in the programme group were aged over 50 years. This raises concerns about the generalisability of findings to other age groups.

Lastly, only three studies were longitudinal, carried out at repeated intervals over a period of two (Glass, Citation2012) or three years (Glass, Citation2009, Citation2013). This mean reverse causality cannot be discounted, and it may be that individuals with higher wellbeing or physical activity are more likely to self-select to participate in CLH.

A final limitation of this review was the decision to focus on papers from OECD countries. While results still included evidence from a range of countries where CLH is common, it is possible that evidence from other contexts, including developing countries where CLH is also increasingly being used as a form of housing delivery (CAHF, Citation2022), may offer alternative insights. For example, some favelas in Brazil are built and often self-managed by residents with community led forms of governance. However as they are not formal developments and may not have government support, they can face problems with safety and difficulties accessing services, such as sanitation and transport, and hence findings may be less positive.

Implications for researchers

There is a promising trajectory of research on the health impacts of CLH, with an increasing number of studies using mixed or quantitative methods in recent years, enabling them to control for confounding factors. The New Economics Foundation (Citation2018) has been developing a Social Return on Investment analysis for a CLH scheme, and further economic studies would be useful to quantify the health costs and benefits of CLH. Although it is unlikely to be possible or appropriate to undertake an experimental approach, such as a randomised controlled trial, larger scale longitudinal studies would be plausible, enabling reverse causality to be ruled out. It would also be recommendable to incorporate residential mobility in subsequent studies.

Literature was heavily weighted towards cohousing (n = 24, 53% of included studies). The CLH sector tends to imagine groups of people being involved in developing long-term communities. However, temporary or short-term communities were important in this review—community housing for refugees and asylum seekers, and temporary communities for people experiencing homelessness are a small but important subsector of CLH which has been significantly under-examined to date. Given that the CLT movement is growing and adapting rapidly worldwide, future research is needed to understand the scope and opportunities for these models to contribute to resident health outcomes.

This review reveals many research gaps, where outcomes from CLH are not known, including primary health outcomes (e.g., respiratory, cardiovascular and infectious diseases, diabetes, injuries, and mental health conditions), and risk factors in the physical environment (e.g., mould, temperature, air pollutants, noise, and hazards). Future research on these outcomes would strengthen the evidence base. Also, the current evidence base is mostly reliant on subjective findings from surveys or interviews. Exceptions include Hackett et al. (Citation2018) and Schneider (Citation2022) who use time of purchase/property stock, and administrative datasets respectively. Tracking objective impacts resulting from CLH on health is needed. Further observational studies with data linkage (e.g., to hospital health records) would be beneficial.

In particular, we report a significant gap in research with children and young people in CLH. There is little known about the demographics of people living in CLTs (Moore & McKee, Citation2012). Research has shown young children spend even more time at home than adults, so are especially vulnerable to health impacts of housing (WHO, Citation2018). Thus more research is needed, and a targeted descriptive or qualitative study would help evaluate the impact of CLH on younger age groups. Lastly, the impact on health inequalities is complex and not yet fully understood, and more research is needed on at scale access to CLH, especially for those living in more deprived circumstances.

Implications for policy makers

The findings from our review are relevant to policymakers from any country where there is a growing use of, or interest in, CLH. As for any housing delivery approach, there are advantages and disadvantages. CLH has, in the past, been viewed as complex and inefficient for delivering at scale or offering a good return on investment. However, this review indicates that CLH offers a potential route to delivering environmentally sustainable, socially inclusive housing, that can help meet people’s support needs. However, it is not a ready-made solution to the ‘housing crisis’, and the points around definitions and different types of CLH discussed in this paper need to be borne in mind if policymakers are to take forward any of the findings of this review, particularly relating to affordability.

There are potential actions policy makers could take to better enable CLH as a form of housing delivery, and to further explore its potentially beneficial impacts on health and wellbeing. At a national level this might include:

Raising the profile of CLH through conferences, events, communication strategies, country specific guides for planners or prospective residents, or awards, e.g., CLH awards projects spanning France, Indonesia and El Salvador (World Habitat, Citation2023).

Providing dedicated and long-term financial support (through grants or loans), particularly for project-specific pre-development activities, such as becoming a registered group, securing a site, and having initial plans approved, e.g., UK’s CLH fund (Homes England, Citation2021).

Including explicit guidance on the role of different sorts of CLH in a range of national policies (e.g., spatial planning, affordable housing and community services), and set expectations for local governments to incorporate CLH quotas into local placemaking strategies.

Developing partnerships with other key stakeholders, such as investors, housebuilders and Registered Social Landlords to consider how aspects of CLH which relate to health and wellbeing can be best incorporated into their schemes.

Setting-up networks to provide support to emerging groups, such as guidance, toolkits, peer-to-peer support and mentoring. This could be on a global (e.g., CoHabit Network, Citation2023), countrywide, regional or local (Community Led Homes, Citation2023) scale.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, this systematic review provides the first overview of the evidence of associations between all forms of CLH and impacts on health, wellbeing and health inequalities. Findings show CLH is associated with largely positive health impacts, including increased physical activity, healthy eating, and wellbeing. It is also positively associated with psychosocial housing factors which are known to be beneficial for health, including social contact, affordability, employment potential, safety, and environmental sustainability. Due to the varied funding and governance models, there are uncertainties over whether all forms of CLH provide a route to affordable housing, particularly regarding cohousing. The impacts of CLH on health inequalities is not yet fully known. Whilst CLH appears particularly beneficial for certain sub-groups, such as people with support needs, more research is needed on access to CLH, especially for those living in more deprived circumstances.

The review reveals a significant research gap, with very little research on the impacts of CLH on children and young people. Additional studies on forms of CLH other than cohousing, primary health outcomes and physical environment factors would strengthen the evidence base, along with larger scale longitudinal studies, which use objective measures such as linked datasets.

These findings provide an indication of the impact from community housing arrangements on health, which warrants further assessment by housing researchers, and indicates the importance of policies and actions to support this form of housing delivery to housing practitioners and policy makers.

Ethics

No ethics approval was sought or required as all papers are available in the public domain.

Social media summary

International review finds a range of community led housing models support positive health and wellbeing outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We thank Power to Change, for initially commissioning an evidence review on CLH and health, which this paper has further developed. The original review is available at https://www.powertochange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/CLH-and-health-report-FINAL-VERSION.pdf. Power to Change is an independent trust that supports community businesses in England, with an original endowment from the National Lottery Community Fund in 2015.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Archer, T. (2009). Help from within: An exploration of community self help. Community Development Foundation. https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/help-from-within-an-exploration-of-community-self-help

- Bates, L. K. (2022). Housing for people, not for profit: Models of community-led housing. Planning Theory & Practice, 23(2), 267–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2022.2057784

- Bird, E. L., Ige, J. O., Pilkington, P., Pinto, A., Petrokofsky, C., & Burgess-Allen, J. (2018). Built and natural environment planning principles for promoting health: An umbrella review. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5870-2

- Bresson, S., & Labit, A. (2019). How does collaborative housing address the issue of social inclusion? A French perspective. Housing, Theory and Society, 37(4), 1–21.

- Carrere, J., Reyes, A., Oliveras, L., Fernández, A., Peralta, A., Novoa, A. M., Pérez, K., & Borrell, C. (2020). The effects of cohousing model on people’s health and wellbeing: A scoping review. Public Health Reviews, 41(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-020-00138-1

- Centre for Affordable Housing Finance in Africa (CAHF), urbaMonde France and urbaSEN Switzerland. (2022). Affordable housing in Africa Study. https://www.urbamonde.org/IMG/pdf/00_etude_sur_les_mecanismes_de_financement_citoyen_introduction_et_conclusion_juin_2020.pdf

- Clever Elephant. (2019). Assessing the potential benefits of living in co-operative and/or community led housing. https://wales.coop/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/CCLH-Report-Summary-2019.pdf

- Coele, M. (2014). Cohousing and intergenerational exchange: Exchange of housing equity for personal care assistance in intentional communities. Working with Older People, 18(2), 75–81. https://doi.org/10.1108/WWOP-01-2014-0001

- CoHabit Network. (2023). About. https://www.co-habitat.net/en/about

- Community Led Homes. (2023). Find your local hub. https://www.communityledhomes.org.uk/find-your-local-hub

- Community Self Build Agency and University of the West of England (CSBA & UWE). (2016). Impact of self-build projects in supporting ex-Service personnel. https://www.fim-trust.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/UWE-CSBA-self-help.pdf

- Co-operative Councils Innovation Network. (2018). Community-led housing: A key role for local authorities toolkit. https://www.communityledhomes.org.uk/sites/default/files/resources/files/2018-09/community-led-housing-key-role-local-authorities.pdf

- Czischke, D., & Huisman, C. J. (2018). Integration through collaborative housing? Dutch starters and refugees forming self-managing communities in Amsterdam. Urban Planning, 3(4), 156–165. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v3i4.1727

- Dang, L., & Seemann, A. K. (2020). The role of collaborative housing initiatives in public value co-creation – a case study of Freiburg, Germany. Voluntary Sector Review, 12(1), 1–20.

- Devlin, P., Douglas, R., & Reynolds, T. (2015). Collaborative design of older women’s CoHousing. Working with Older People, 19(4), 188–194. https://doi.org/10.1108/WWOP-08-2015-0018

- Fernandez, M., Scanlon, K., & West, K. (2018). Well-being and age in cohousing life: Thinking with and beyond design. Housing Learning and Improvement Network.

- Garciano, J. L. (2011). Affordable cohousing: challenges and opportunities for supportive relational networks in mixed-income housing. Journal of Affordable Housing & Community Development Law, 20, 169–192.

- Garrett, H., Mackay, M., Nicol, S., Piddington, J., & Roys, M. (2021). The cost of poor housing in England: 2021 briefing paper. BRE Trust.

- Glass, A. P. (2009). Aging in a community of mutual support: The emergence of an elder intentional cohousing community in the United States. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 23(4), 283–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763890903326970

- Glass, A. P. (2012). Elder co-housing in the United States: Three case studies. Built Environment, 38(3), 345–363. https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.38.3.345

- Glass, A. P. (2013). Lessons learned from a new elder cohousing community. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 27(4), 348–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763893.2013.813426

- Glass, A. P. (2016). Resident-managed elder intentional neighborhoods. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 59(7–8), 554–571. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2016.1246501

- Glass, A. P., & Vander Plaats, R. S. (2013). A conceptual model for aging better together intentionally. Journal of Aging Studies, 27(4), 428–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2013.10.001

- Goulding, R., Berry, H., Davies, M., King, S., Makin, C., & Ralph, J. (2018). Housing futures: What can community-led housing acieve for Greater Manchester? http://www.gmhousingaction.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/Housing-futures-MAIN-REPORT-Final.pdf

- Hackett, K. A., Saegert, A., Dozier, D., & Marinova, M. (2018). Community land trusts: Releasing possible selves through stable affordable housing. Housing Studies, 34(1), 24–48).

- Heslop, J. (2017). Protohome: Rethinking home through co-production. In M. Benson & I. Hamiduddin (Eds.), Self-build homes: Social discourse, experiences and directions (pp. 96–114). UCL Press.

- Homes England. (2021). Community Housing Fund: Prospectus, accessible version. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/community-housing-fund-prospectus/community-housing-fund-prospectus-accessible-version

- Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O'Cathain, A., Rousseau, M.-C., & Vedel, I. (2019). Improving the content validity of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT): A modified e-Delphi study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 111, 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2019.03.008

- Hong, Q. N., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M., P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M.-C., & Vedel, I. (2018). Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada. http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf

- Ige, J., Pilkington, P., Orme, J., Williams, B., Prestwood, E., Black, D., Carmichael, L., & Scally, G. (2019). The relationship between buildings and health: A systematic review. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England), 41(2), e121–e132. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdy138

- Izuhara, M., West, K., Hudson, J., Arrigoitia, M. F., & Scanlon, K. (2021). Collaborative housing communities through the COVID-19 pandemic: Rethinking governance and mutuality. Housing Studies, 39, 65–83.

- Jarvis, H. (2015). Towards a deeper understanding of the social architecture of cohousing: Evidence from the UK, USA and Australia. Urban Research & Practice, 8(1), 93–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2015.1011429

- Joseph Rowntree Foundation. (2013). Senior Cohousing Communities- an alternative approach for the UK? https://www.jrf.org.uk/report/senior-cohousing-communities-%E2%80%93-alternative-approach-uk

- Kehl, K., & Then, V. (2013). Community and civil society returns of multigeneration cohousing in Germany. Journal of Civil Society, 9(1), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448689.2013.771084

- Labit, A. (2015). Self-managed cohousing in the context of an ageing population in Europe. Urban Research & Practice, 8(1), 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2015.1011425

- Labit, A., & Dubost, N. (2016). Housing and ageing in France and Germany: The intergenerational solution. Housing, Care and Support, 19(2), 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1108/HCS-08-2016-0007

- Lang, R., & Novy, A. (2014). Cooperative housing and social cohesion: The role of linking social capital. European Planning Studies, 22(8), 1744–1764. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2013.800025

- Lubik, A., & Kosatsky, T. (2019). Public health should promote co-operative housing and cohousing. Canadian Journal of Public Health = Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique, 110(2), 121–126. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-018-0163-1

- Markle, E. A., Rodgers, R., Sanchez, W., & Ballou, M. (2015). Social support in the cohousing model of community: A mixed-methods analysis. Community Development, 46(5), 616–631. https://doi.org/10.1080/15575330.2015.1086400

- Martin, D. G., Esfahani, A. H., Williams, O. R., Kruger, R., Pierce, J., & DeFilippis, J. (2019). Meanings of limited equity homeownership in community land trusts. Housing Studies, 35(3), 395–414.

- Moore, T., & McKee, K. (2012). Empowering local communities? An international review of community land trusts. Housing Studies, 27(2), 280–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2012.647306

- Mullins, D. (2018). Achieving policy recognition for community-based housing solutions: The case of self-help housing in England. International Journal of Housing Policy, 18(1), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2017.1384692

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2014). Interim methods guide for developing service guidance 3024, process and methods [PMG8], Appendix 2 Checklists, 1.9 Checklist: Grey literature. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg8/chapter/appendix-2-checklists#19-checklist-greyliterature

- New Economics Foundation. (2018). Communities are building the affordable homes that London needs, keeping land in public hands is the key to better housing. https://neweconomics.org/2018/02/communitiesbuilding-affordable-homes-london-needs

- Pedersen, M. (2015). Senior co-housing communities in Denmark. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 29(1–2), 126–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/02763893.2015.989770

- Pineo, H., Zimmerman, N., Cosgrave, E., Aldridge, R., Acuto, M., & Rutter, H. (2018). Promoting a healthy cities agenda through indicators: Development of a global urban environment and health index. Cities & Health, 2(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2018.1429180

- Prasad, G. (2019). Supported independent living: Communal and intergenerational living in the Netherlands and Denmark. https://www.housinglin.org.uk/_assets/Resources/Housing/OtherOrganisation/Supported-Independent-Living-Communal-and-intergenerational-living-in-the-Netherlands-and-Denmark.pdf

- PRISMA. (2020). PRISMA 2020 expanded checklist. https://prisma-statement.org/documents/PRISMA_2020_expanded_checklist.pdf

- Rosenberg, J. (2012). Social housing, community empowerment and well-being: Part two – measuring the benefits of empowerment through community ownership. Housing, Care and Support, 15(1), 24–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/14608791211238403

- Ruiu, M. L. (2015). The effects of cohousing on the social housing system: The case of the Threshold Centre. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 30(4), 631–644. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-015-9436-7

- Ruiu, M. L. (2016). Participatory processes in designing cohousing communities: The case of the community project. Housing and Society, 43(3), 168–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/08882746.2017.1363934

- Sanguinetti, A. (2014). Transformational practices in cohousing: Enhancing residents’ connection to community and nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 40, 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.05.003

- Scanlon, K., & Arrigoitia, M. F. (2015). Development of new cohousing: Lessons from a London scheme for the over-50s. Urban Research & Practice, 8(1), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/17535069.2015.1011430

- Scanlon, K., Hudson, J., Arrigoitia, M. F., Ferreri, M., West, K., & Udagawa, C. (2021). ‘Those little connections': Community-led housing and loneliness. Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1035018/Loneliness_research_-__Those_little_connections_.pdf

- Schneider, J. K. (2022). Interrupting inequality through community land trusts. Housing Policy Debate, 33(4), 1002–1026.

- Shrestha, P., Gurran, N., & Maalsen, S. (2021). Informal housing practices. International Journal of Housing Policy, 21(2), 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2021.1893982

- Souto, R., Khanassov, V., Hong, Q. N., Bush, P., Vedel, I., & Pluye, P. (2015). Systematic mixed studies reviews: Updating results on the reliability and efficiency of the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(1), 500–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.08.010

- Stevens, J. (2016). Growing older together: An overview of collaborative forms of housing for older people. Housing Learning and Improvement Network.

- Theriault, L., Leclerc, A., Wisniewski, A. E., Chouinard, O., & Martin, G. (2010). “Not just an apartment building”: Residents’ quality of life in a social housing co-operative. Canadian Journal of Nonprofit and Social Economy Research, 1(1), 82–100. https://doi.org/10.22230/cjnser.2010v1n1a11

- Tummers, L. (2016). The re-emergence of self-managed cohousing in Europe: A critical review of cohousing research. Urban Studies, 53(10), 2023–2040. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098015586696

- Tyndall, J. (2010). AACODS checklist for appraising grey literature. Flinders University.

- Umberson, D., & Montez, J. K. (2010). Social relationships and health: A flashpoint for health policy. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 51, S54–S66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022146510383501

- Van den Berg, P., Sanders, J., Maussen, S., & Kemperman, A. (2021). Collective self-build for senior friendly communities. Studying the effects on social cohesion, social satisfaction and loneliness. Housing Studies, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2021.1941793

- Wang, J., Pan, Y., & Hadjri, K. (2021). Social sustainability and supportive living: Exploring motivations of British cohousing groups. Housing and Society, 48(1), 60–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/08882746.2020.1788344

- Warner, E., Chambers, L., & Andrews, F. J. (2022). Exploring perspectives on health housing among low-income prospective residents of a future co-housing “Microvillage” in Geelong, Australia. Housing and Society, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/08882746.2022.2079943

- Warner, E., Sutton, E., & Andrews, F. (2020). Cohousing as a model for social health: A scoping review. Cities & Health, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/23748834.2020.1838225

- Weeks, L., Bigonnesse, C., McInnis-Perry, G., & Dupuis-Blanchard, S. (2019). Barriers faced in the establishment of cohousing communities for older adults in Eastern Canada. Journal of Housing For the Elderly, 34(1), 1–16.

- Woetzel, J., Ram, S., Mischke, J., Garemo, N., & Sankhe, S. (2014). A blueprint for addressing the global affordable housing challenge. McKinsey Global Institute. https://www.mckinsey.com/∼/media/mckinsey/featured%20insights/urbanization/tackling%20the%20worlds%20affordable%20housing%20challenge/mgi_affordable_housing_executive%20summary_october%202014.ashx

- World Habitat. (2023). Community led housing. https://world-habitat.org/our-programmes/community-led-housing/#relatedAwards

- World Health Organisation (WHO). (2018). WHO Housing and health guidelines. World Health Organisation.