Abstract

Incrementalism is a mode of self-help and continuing practice that is prevalent primarily in the Global South. It enables owner-builders to meet housing needs typically over an extended period of time as they can more conveniently manage the required resources. While (informal) tenure, materiality, and housing conditions have long been the focus of incremental housing scholarship, researchers are increasingly recognising the value of incrementalism’s metabolic interplay with broader urban processes. This paper complements these later works by qualitatively examining four dominant incremental housing pathways in the urban fringes of Khulna, Bangladesh: absentee landholding, makeshift sheltering, speculative land disposal and informal brokerage. Empirical evidence suggests that a variety of actors, primarily motivated by land speculation, participate in these incremental housing pathways. While the implementation of the official plan for Khulna’s peri-urban areas is delayed, I argue that these actors coproduce a complex housing market as well as a self-help city in which urban institutions play more passive and reactionary roles. The findings contribute to rethinking the self-organising logic of urban expansion in many Southern cities, which is often centred on urban land at the crossroads of institutional capacity deficit, speculative housing demand and supply, and informal-formal hybridity.

Introduction

Incrementalism is a type of self-help and progressive practice which enables often, but not always, owner-builders to satisfy housing needs typically over a long period as they can more conveniently manage the necessary resources (e.g., finance, materials, labour, etc.) (van Noorloos et al., Citation2020). Thus, incremental housing has been a ‘response to and an expression of housing precarity’ (Vasudevan, Citation2015, p. 352), particularly for those who typically struggle to gain access to urban land and/or institutional incentives (e.g., finance) and construction materials in the first place (Greene & Rojas, Citation2008). Although the majority of research on incremental housing focuses on informal, ‘self-help’ and ‘bottom-up’ house building practices of the urban poor, primarily in the Global South, there is evidence that people of all socio-economic classes, both in the Global North and South, may engage in incremental practices, not always entirely within informal domains, but also with formalised supports (Bredenoord & van Lindert, Citation2010; Galuszka & Wilk-Pham, Citation2022; Greene & Rojas, Citation2008). It is becoming increasingly evident that much incremental housing is not self-built by the owner/occupier alone, as much of the literature on incremental housing assumes, but rather part of larger ‘assisted self-built’ schemes involving a variety of stakeholders, such as financers, NGOs, community collectives, and state institutions within formal-informal hybrid arrangements, which the current paper also unpacks in the context of a Bangladeshi city.

While (informal) tenure, materiality, labour, housing conditions, finance and forms of assistance, and the dweller’s freedom to build have long been the focus in the scholarship of incremental housing, researchers are increasingly recognising the value of its metabolic interplay with the broader urban processes (Amin & Cirolia, Citation2018; van Noorloos et al., Citation2020). This body of work is heavily influenced by post-structural urban scholarship, which regards cities as complex socio-technical systems in which numerous actors and processes interact, often across multiple geographic, institutional, and governance scales (Amin & Thrift, Citation2017; Brenner et al., Citation2011; McFarlane, Citation2011). This line of thought is consistent with more recent relational readings in housing studies literature, which reimagines housing/homemaking as multi-scalar processes and recognises continuities and interdependencies with wider socio-ecological structures and practices within the city (Alam et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Cook et al., Citation2016). These studies have a philosophical foundation in the growing feminist, post-human and urban political ecology scholarship arguing that successful housing/home is contingent on diverse transactions with the social (human and more-than-human), political, financial, and natural worlds where the material house is located (Alam et al., Citation2018; Cook et al., Citation2013; Cook et al., Citation2016; Kaika, Citation2004).

With the relational housing lens, this paper examines the metabolic interactions between incremental housing supplies and peri-urban land in Khulna, Bangladesh. Khulna has undergone a considerable infrastructural and spatial transformation in recent years resulting in massive land speculation on its fringes to meet the housing demand of its growing population. As a result, many new actors have emerged, including urban poor, migrants from coastal areas, absentee elites, small and large landholders, and temporary real-estate entrepreneurs. The diverse tactics and practices developed by these actors to engage with the peri-urban land have gradually transformed Khulna’s extended urban areas from a predominantly agriculture-based land economy to a largely unregulated land-based housing market (Alam et al., Citation2016). It could be argued that the land market flourished as a result of the city authority’s inability to establish planning controls in its peri-urban areas in a timely manner, attracting various actors. As the results section will demonstrate, this is a compelling case study depicting how the agencies of urban land relationally co-produce both a complex housing market and a self-help city in which urban authorities play a more reactionary role by making necessary adjustments in their governance and service mechanisms.

The recent development in incremental housing literature is discussed first in the following section to show how incremental housing processes are intricately linked to the flows of materials and agencies of the city and beyond (Amin & Cirolia, Citation2018; van Noorloos et al., Citation2020). I then discuss the recent ‘relational turn’ in housing literature, which acknowledges multi-scalar housing processes (for example, Cook et al., Citation2016; Jacobs & Malpas, Citation2013), and thus the metabolic interactions between housing and the city. This conceptual exchange will aid in making sense of the incremental housing pathways visible at the intersections of peri-urbanisation, speculative land dynamics and responses by various private actors and the urban institution. Following an overview of the state of housing incrementalism in Bangladesh, I describe the study setting, with a particular focus on Khulna’s urban expansion since 2001. The method section is then followed by the presentation of four dominant incremental housing pathways: absentee landholding, makeshift sheltering, speculative land disposal, and informal brokerage. In the final section, I discuss the implications of these findings for rethinking the self-organising logic of Khulna’s urban expansion, which is intricately linked with the various agencies, ideas, labour, and actors that proliferate and centre on urban land. Finally, I highlight the importance of relational housing theories in providing a fresh perspective on the metabolic interactions between residential land supply, speculative incrementalism, and bottom-up city-making.

Incremental housing and city-making

Incrementalism enables self-help and progressive practices to satisfy housing needs, which are most visible in the Global South. As much as 70 per cent of urban housing in developing countries is built incrementally (Wakely & Riley, Citation2011). Incrementalism offers a novel perspective for rethinking housing, not as an outcome or a finished product, but as a process that enables owner-builders to satisfy housing needs typically over a long period of time because they can more conveniently manage the required resources, such as finance, material, labour, and so on (van Noorloos et al., Citation2020; Amoako & Frimpong Boamah, Citation2017). Thus, incremental housing has been a ‘response to and an expression of housing precarity’ (Vasudevan, Citation2015, p. 352), particularly for those who do not have a legal entitlement to urban land and/or institutional incentives to begin with (Greene & Rojas, Citation2008). In many places, ‘policies for informal housing that range from neglect and denial of services and infrastructure to forced eviction give way to incremental housing approaches’ (Garland, Citation2013, p. 2) in which households ‘individually or collectively’ improve their living conditions outside of government regulations and controls to reflect their ‘gradually changing socio-economic circumstances’ (McFarlane, Citation2011, p. 658). This is why incrementalism and informality may go hand in hand, as building practices often occur without any proper design and approvals, either on vacant government land or privately owned land that has been informally subdivided and sold or rented out by its owners.

However, informality is not always the premise of incrementalism. Incrementalism is often entwined with the processes of the formal city, as supports (finance, labour-power, administration, etc.) for incremental practices can be both autonomous and organised by an institution. In the 1970s and 1980s, for example, the World Bank pioneered first-generation slum upgrading approaches to support self-help urban development through incremental housing production in marginalised settings in the Global South (Werlin, Citation1999). More formalised incrementalism involves site-and-service mechanisms that ensure formal access for each beneficiary household to a plot connected to essential services, such as drinking water, electricity, sewage and stormwater disposal networks. Each family then builds, often in stages, to suit their household size and economic circumstances, either through a building contractor, small builder, or self-help. Another type of formalised incrementalism, ‘core housing’ (Hamid & Mohamed Elhassan, Citation2014, p. 183; see also Wakely & Riley, Citation2011), became popular worldwide because it provided beneficiaries with a roofed space to immediately move into at a low initial cost, and then expand and improve over time. Similarly, many people engage in incremental practices in readymade housing sites purchased from the formal market, and intermittent structural alterations continue in response to an owner’s diverse familial and economic circumstances over time (Alam et al., Citation2022; Burgess, Citation1985).

Recognising the many flexibilities incrementalism or self-help mechanisms may offer to the housing poor, British architect and theorist John FC Turner pioneered the concept in the 1970s and 1980s to celebrate the rights and capacities of the poor. Incrementalism was increasingly seen as a solution in places (e.g., Latin America and South Asia) where poorly developed public housing programmes failed to solve the housing affordability problem (Harris, Citation2003; Werlin, Citation1999). Incrementalism was viewed as a means of ‘development from the below,’ as the urban housing poor could improve their living conditions, especially when encouraged by security of tenure and access to credit. Turner argued that incrementalism could resist top-down state interventions in dealing with slums, which often took the form of eviction and did not produce results that reflected the needs and aspirations of the beneficiary groups (Morshed, Citation2016 on Turner & Fichter, Citation1972). Turner’s ‘minimal state’ theory was later heavily contested by scholars who argued that access to land and tenure security must remain at the heart of incremental housing for it to be sustainable and replicable, with the state playing a critical role as a mediator (see Burgess, Citation1985; Werlin, Citation1999). This means that incrementalism is an ‘enabling’ approach to solving housing problems if the appropriate resources are available, such as access and entitlement to land, house building loans, and services and planning controls that support incrementalism (Amoako & Frimpong Boamah, Citation2017; Chiodelli, Citation2016; Ferguson & Smets, Citation2010; Greene & Rojas, Citation2008; Hamid & Mohamed Elhassan, Citation2014; Wakely & Riley, Citation2011).

More recent incremental housing literature has shifted the emphasis from tenure and housing conditions to highlighting the ways incremental housing processes are linked to city-wide systems (Amin & Cirolia, Citation2018; van Noorloos et al., Citation2020). That scholarship is based on conceptual innovations in urban studies that recognise cities as complex socio-technical assemblages where numerous actors and processes ‘entangle’ (Shafique, Citation2022), often across multiple geographic, institutional and governance scales (Amin & Thrift, Citation2017). McFarlane (Citation2011) defines the relationship between informal city-making and incremental housing as a ‘dwelling process’ (p. 658) based on the logic that the rate and forms of informal urbanisation reflect the socio-economic circumstances of those who devise incrementalism to ‘dwell’ in the city. They progressively build housing infrastructures by using the city itself as a space of ‘flexible resources’ (Simone, Citation2008, p. 200). Their agencies are the product of the structural condition of the city; at the same time, these agencies reinforce the structural conditions and reproduce the city (Huchzermeyer, Citation2011; Simone, Citation2008).

Van Noorloos et al. (Citation2020) emphasise that city-making in the global South directly impacts localised incremental housing practices involving transactions of land, finance, infrastructure, building materials, and labour. The diverse constellation of technologies, infrastructures, and actors that comprise incrementalism (e.g., experts, handymen, brokers, etc.—see Baitsch, Citation2018) has implications for urban density, governance and control (Amin & Cirolia, Citation2018), and forms of partnership that evolve and support incrementalism (Cirolia et al., Citation2016). Particularly in the Global South, where informality has often outpaced formal planning and institutions (Cirolia et al., Citation2016), incrementalism frequently plays an ‘integrated role’ (Dovey & King, Citation2011; Roy, Citation2005) in signalling the formation of the city (Wakely & Riley, Citation2011). In keeping with this body of work, I examine in this paper how forms of housing incrementalism shape Khulna’s peri-urbanisation. The following section delves deeper into the ‘relational turn’ in housing literature, which will aid in making sense of incremental housing practices and city-making centred on urban land.

The relational turn, housing, and the city

According to the literature on relational housing, housing/home is conceptually and materially porous, as successful housing/home is produced by establishing diverse linkages with the broader urban (and socio-ecological) processes (Alam et al., Citation2020a; Kaika, Citation2004; Steele & Vizel, Citation2014). These studies assume that people can maintain desired lifestyles, housing choices, construction, and tenure by assembling ‘functional relationship(s)’ (Dunn, Citation2006, p. 214) in the housing-city interface to access vital resources, such as water, energy, internet, waste, animals, plants, and even labour. This is particularly important in dynamic informal circumstances in the Global South, where marginalised groups must negotiate various urban social and ecological relations as a critical resource to maintain successful housing outcomes (Alam et al., Citation2018, Citation2020a, Citation2020b). In summary, while historically the material house was perceived as a bounded private space to hide bodies, practices, and household relations from the ‘public’ gaze, the relational turn calls for paying attention to the housing ‘relations’ that extend outside the private sphere and ‘transect the public and political worlds’ (Brickell, Citation2012, p. 226).

Cook et al. (Citation2016) emphasise the utility of the relational approach since it allows researchers to recognise a housing site embedded within the macro-structural processes of the city. This philosophical underpinning raises new conceptual and empirical questions about housing in a variety of ways (Cook et al., Citation2016, p. 1). The approach offers valuable opportunities to rethink housing as a socio-technical process embedded within larger institutional settings, such as planning bodies and municipal service providers, and even financial institutions. A classic example is how the materials and meanings of owner-occupied housing are constituted and experienced through the accumulation and deployment of secured debt within the UK financial regime (see Cook et al., Citation2013). The approach also aids in understanding housing outcomes within an assemblage of policies and practices, such as slum upgradation projects, micro-finance schemes, and livelihood improvement programmes, all of which support the housing development of the urban poor. Beyond macro-dynamics, the approach aids in understanding how a housing site and its experiences of homemaking evolve and are shaped by its immediate socio-ecologies, such as accessibility to urban land, water, and livelihoods, as well as various human actors and non-human agencies interacting within the ecologies (Alam et al., Citation2020a, Citation2020b; Gillon, Citation2014).

Inspired by the relational turn, this paper moves away from simply asking in what circumstances and how residents adopt incrementalism, which has long been at the centre of attention in incremental housing scholarship. Van Noorloos et al. (Citation2020 p. 39; emphasis added) also warn that ‘focusing on very localised household needs, opportunities, and challenges may fail to provide adequate and scalable housing solutions in the absence of a solid understanding of the broader urban system’. As a result, I propose a relational approach to unpacking the various housing pathways in Khulna’s urban fringes by examining the situated agencies, including the multiple ‘registers, linkages and flow’ (Amin, Citation2004) that shape Khulna’s incremental housing landscape centred on urban land, which is also a product of the regional infrastructural changes and the city’s urban planning and development agenda. A relational reading will aid in making sense of the fluidity and exchanges between dwellers and many non-dweller actors who contribute to housing incrementalism and the self-help city.

Housing supply and incrementalism in Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, government-provided ready-to-occupy housing units are insignificant when compared to the country’s massive population of 170 million. The Ministry of Housing and Public Works (MoHPW), through the Public Work Department (PWD) and the National Housing Authority (NHA), is the primary government agency in charge of constructing readymade housing units for government sector officials. In the private sector, developers, individual landowners, developers and landowners working together and various (owners’) associations construct ready-to-occupy housing units, primarily apartments (Ahmad, Citation2015). This mode of housing supply is most common in major urban centres.

The majority of housing production in the country is done incrementally and with self-help, beginning with a household gaining access to a piece of land through purchase or inheritance, then building the first unit to occupy for their own family, and following that building additional units to rent as circumstances allow. Formal institutions also foster incrementalism. For example, the Rajdhani Unnayan Kotripakha (RAJUK) in Dhaka and other city development authorities in charge of urban planning and management have often taken the role of land developers, providing sites and services mainly for the wealthy and middle-income groups to later build on those lands on their own (Rahman & Ley, Citation2020). House building finance schemes are available through traditional banking systems and the Bangladesh House Building Finance Corporation (BHBFC); however, they rarely cover the entire cost of land and construction, forcing private landowners to embrace incrementalism.

The government and private sector promoted incrementalism, particularly for housing the poor, to alleviate poverty rather than solve the housing problem. In rural areas, the government offered programmes such as Guscho Gram (cluster villages), Asrayon (shelter), Ghorey Phera (returning home) and Ekti Bari Ekti Kahmar (one homestead, one farm) to assist the landless and homeless in gradually rehabilitating (Sarker et al., Citation2008). Various government [e.g., Grihayon Tahobil (housing fund)] and non-government organisation enabled micro-finance schemes have targeted people experiencing poverty in rural and urban areas. Many of these schemes targeted enterprising women who were eager to improve their housing situation once they could earn and save (Morshed, Citation2016; Waliuzzaman & Alam, Citation2022). These interventions gained popularity among the poor because traditional banks shy away from supporting the poor (Rahman & Ley, Citation2020) as they require a piece of land as collateral. Due to a lack of access to bank loans, people with low incomes are forced to finance a plot of land incrementally before proceeding with house construction.

The study context: Khulna, Bangladesh

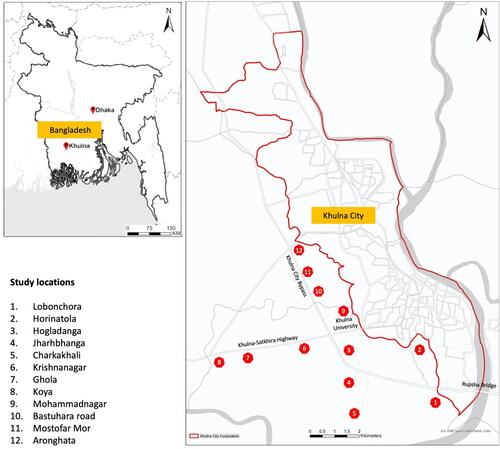

Khulna is the third-largest city in Bangladesh and serves as the administrative centre for the Khulna District and Division. The metropolitan Khulna has a population of approximately 718,735 people, with a population density of 15,744 people per sq. km (BBS, Citation2022, p. 10). Nationally, Khulna has the third-highest concentration of officially defined ‘poor’ populations within urban centres who are not only economically poor but also the housing poor (BBS, Citation2015, pp. 32–34). They make up one-fifth of the city’s population (Ashiq-Ur-Rahman, Citation2012, p. 127). The majority of poor people are migrants from villages who live in the 1134 slums within Khulna City Corporation (KCC) (BBS, Citation2015, p. 35) or on the fringes of Khulna (), which are outside of the coverage of municipal services.

Since the 1990s, a number of major regional infrastructure projects, including Khulna University, the Ruphsa Bridge, the Padma Bridge connecting Khulna with the capital city, and a new Export Processing Zone (EPZ) within reach of 60 km in the Mongla river port, have contributed to population growth and the demand for housing, particularly among migrants and lower to middle-income groups. As a result, the city expanded horizontally, causing a rapid decline in farmland (by 49%) and water bodies (by 19%) and a dramatic increase in built-up areas, primarily to accommodate new housing provisions and associated amenities: 96% within the city and 468% in its periphery (Sowgat & Roy, Citation2020).

The current Khulna Master Plan (KMP) 2001, which was initially conceived in the early 2000s, covers an area of 451.18 sq. km (KDA, Citation2014). The KMP 2001 included an expanded peripheral area of 181.16 square kilometres, primarily ‘rural and agricultural land’ (KDA, Citation2002). However, implementing planning control to manage developments in these fringes was significantly delayed since the Detail Area Development Plan (DADP) 2014, the key government document to implement KMP 2001, was completed in 2016 and was only gazetted in June 2018. During this time lag, however, 2.5% of farmland was gradually converted into non-agricultural land on an annual basis (KDA, Citation2014). The south-western fringes, where my study was conducted, have seen the most rapid urban transformation along the Khulna-Satkhira inter-district highway and the newly constructed city bypass highway (). As documented in the DADP, by 2009–2010,

…almost all agricultural land within the city periphery has already been sold out … The buyers are now waiting for the right moment to start development, a significant part of which is likely to go to residential use. (KDA, Citation2014: Chapter 2.2)

Khulna’s fringes sit within an ambiguous institutional setting with overlapping jurisdictions by multiple institutions that frequently take a market-based approach and only provide services to those who are formally enrolled as clients. Khulna Development Authority (KDA) primarily oversees urban planning and implementation. Khulna City Corporation (KCC) is in charge of essential municipal services such as waste collection. The Khulna Water Supply and Sewerage Authority (KWASA) oversees the city’s water and sanitation systems. Before the KDA took over, the south-western fringes were under the jurisdiction of the Batiaghata Union Parishad, the designated authority for planning and building approval outside Khulna’s municipal boundaries. During the delay in implementing the DADP, development control and enforcement were rarely extended to the urban fringes as the KDA selectively approved developments that did not conflict with the planning intention of the proposed DADP. The delay exacerbated the lack of planning required to meet rising housing demand and paved the way for uncontrolled urbanisation, as we will see in the results section.

Materials and methods

The findings are based on ten years of intensive ethnographic work in the study area. Between 2003 and 2013, I worked as an architect in Khulna, where I actively observed urban transformation and participated in various planning meetings and consultation processes as part of the DADP preparation. Between November 2014 and June 2015, I used a variety of methods to investigate how different stakeholders interacted with rapidly urbanising peri-urban land after its inclusion in the Master Plan, how these engagements triggered incremental housing pathways, and how these pathways informed urbanisation from below.

The primary data set includes 96 semi-structured interviews conducted in twelve different locations (): Lobonchora, Horinatola, Mohammadnagar Jharbhanga, Charkakhali, Krishnanagar, Hogladanga, Ghola, Koya, Mostofar Mor, Bastuhara Road and Aronghata. lists the stakeholders who participated in the interviews. Participants were identified through snowballing, with the first few identified through my connections in the community. Five focus groups were held with various combinations of participants. Fieldwork also included extensive participant observations documented in photographs, freehand sketches, and diary notes. All interview transcripts, excerpts of planning documents, diary notes, sketches, and photographs were entered into NVivo and cross-referenced according to relevance. Thematic analysis of the data revealed a small number of actors, such as small and large landholders, land brokers, and landless rural migrants, who engage with peri-urban land to initiate four incremental housing routes, which are discussed in detail in the following section.

Table 1. Methods and materials.

Incremental housing pathways in peri-urban Khulna

The land is pure, it is divine – this is the best investment option, even better than putting money in the bank… the cost of land has risen a thousand times in this area. The desire to own a piece of land has become so entrenched in society that ‘people’ in this part of Khulna literally live on, sleep on, dream about, and quarrel over the land!

The above statement was made by a self-proclaimed land broker who operated a roadside tea shop in the study area. Indeed, the inclusion of peri-urban land in the master plan in early 2000 boosted land prices. As a result, the study area experienced a 40% to 900% price increase within a decade (KDA, Citation2014: section 2.13). Non-farmer landowners own 62–70% of the land (Alam et al., Citation2016). I was particularly interested in the various groups of ‘people’ who were driven by land speculation and how they interacted with peri-urban land.

Among the various actors revealed by my investigation, absentee urban elites have made significant investments in land and are waiting for the right time to develop it. Meanwhile, agricultural activities have attracted landless rural migrants from coastal villages, who look after absentee owners’ land and land-based products in exchange for a place to live. The urban housing poor was another dominant group that could not afford a piece of land within the city. They were among the first to invest in these fringes when the land was cheap. They gradually invested in developing their small land parcels beginning in 2000 and, later, in house building. Then, locally grown land developers and brokers used a variety of creative means to run a seemingly unregulated land market in these fringes.

Thematic analysis of these actors’ diverse strategies informs how they have positioned themselves at different hierarchies in the peri-urban land ecosystem and initiated four distinct incremental housing routes: absentee landholding, makeshift sheltering, speculative land disposal, and informal brokerage. The four routes are the first step to initiating housing development for owners by securing access to peri-urban land, after which achieving the final housing outcomes will take years. Later, I will argue that these routes centred on urban land have co-produced housing options for urbanites and a self-help city, in which formal institutions have played more passive and reactionary roles.

Absentee landholding

The delay in implementing the master plan prompted speculative investment in low-lying cheaper agricultural land on the fringes. Absentee landowners delayed land development and construction until the KDA began processing planning approvals in those sections, and the KCC extended municipal services. Some landowners waited because they needed time to manage construction resources. House building financing was not available without approved house plans, nor was farmland valuable collateral to the bank. During the waiting period, landowners continued with their existing farming activities.

Nonetheless, absentee landholding of farmlands necessitated protection from land robbery and disputes. In a context where the land information system is not digitised, and the landowner is absent for an extended period of time, dishonest brokers have shown the same land parcel to multiple buyers and sold it multiple times. As a result, the original landowner and other claimants are involved in legal battles that can take years to resolve in Bangladesh. Boundary disputes with neighbours are common because land parcels often lack clear ownership demarcation, which is complicated further by a lack of oversight and prolonged absenteeism on the part of the owners. As revealed in interviews and observed during numerous field visits, absent landowners have devised various strategies to avoid the risks. The most common approach is to install signage with the landowner’s contact information (). Precast pillars or boundary walls are frequently used for plot demarcation immediately following land purchase (). All of these installations, however, require regular monitoring.

Figure 2. (a) Signage with landownership information; (b) plot demarcation while farming continues; (c) strategic plantation in the plot; (d) land development for building works. Source: Author.

Some absentee landowners leased the land for farming purposes until the settlements were suitable for house construction. When landowners anticipated a long period of absenteeism for the next 15–20 years, they went for strategic plantation on the land () to source timber for future construction. Another common strategy is to hire landless rural migrants to look after the land. On most occasions, these families are housed in a remote corner of the land with no rental contract. Their primary responsibility is to look after the land and serve the patron’s farming interests. Patrons may occasionally direct them to gradually develop the land to construction readiness (e.g., earth filling, gathering construction materials, and so on) (). These are lengthy and intermittent steps that typically take 3–10 years. According to one planning official, these absentee landholding practices were early indicators for the KDA of where its citizens wanted their future city to be located. Furthermore, because this group of landowners temporarily housed homeless rural migrants, city officials were relieved because there was less pressure in established slums within the urban core.

Makeshift sheltering

The second route entails landowners establishing their presence on the land by visibly beginning house construction, dwelling, and planning ahead. Some landowners did not move in but instead rented out their dwelling units. Most of the time, these units are minor interventions, often makeshift arrangements, to meet the family’s immediate housing needs. They occasionally built an additional temporary structure, usually a room, to accommodate growing family members or to rent out to a small family for extra income (). As evidenced by the quote below, the owners’ decision to invest in the land was influenced by the surrounding circumstances.

Figure 3. (a) Owner-occupier’s shop; (b) permanent (pile) foundation on which temporary house to be built; (c) an extension of the house rented out; (d) sales advertisement by owner-occupiers. Source: Author.

I bought this land in 1993 for BDT 4500 (US$ 52) per Katha (720 sq. ft). Now, in 2015, it is BDT 400,000 (US$ 4600). In Khulna (within the city), I was renting. Now I live in my own house, even though it only has two rooms, a half-finished toilet, and we have yet to build the kitchen. Soon, a 40-ft-wide road will connect my site. We set up a makeshift shop () for my wife to sell homemade food; this is also our kitchen… There are construction workers everywhere, so there are many customers…

Landowners had to navigate institutional uncertainty by doing semi-permanent construction while they were told to ‘wait’ until the KDA was ready to accept building approval applications, perpetuating incrementalism. Without approval, it was impossible to obtain housing finance. As a result, the owners took calculated risks by investing as little as possible in construction. Construction, for example, was done in such a way that it could be later integrated with the approved structure. Some laid the foundation for the future building after hiring a professional (architectural) firm (), and then built a temporary house on top of it. When the land was large enough, some landowners dug a shallow pond for fish cultivation and raised the house’s plinth with earth. The plan was to later convert the pond into a semi-basement parking floor and incorporate it into the overall design. Some went a step further, selling out floors/residential units off the architect’s plan while they waited for approval (). In the absence of essential urban service provisions from formal institutions, the owner-occupiers were required to construct a septic tank, water reservoir, or a deep tube well in strategic locations on the site, which could be later adjusted with the supply mains when they became available. In the absence of municipal services, in areas where these owners reached a critical population, they either collectively organised or actively pursued urban institutions for amenities and services. As the following individual explained, these extended parts of the city were being organised incrementally by these onsite landowners:

When we first moved here, accessibility was a major issue. We had to walk through knee-deep water, but now we have temporary roads. If there are more households, the KCC will step in. In some places, landowners have given up a foot of their land to make the road wider, which has been recorded on the master plan. Once the road is marked, we can approach the electricity board and others for service provisions. They will provide us with electric poles if we manage ten subscribers; we will raise funds for the cable.

Speculative land disposal

The third route involves land speculators who refuse to call themselves conventional land developers. As evidenced in the quote below, they identify themselves as affordable housing providers for those who cannot afford to buy land within city limits. They had no prior land development experience and no formal institutional arrangement (e.g., trade licence, REHABFootnote1 membership, etc.). They primarily served the low-to-middle-income class, which typically do not have access to land finance through traditional financial institutions.

I have a client base that cannot afford to buy land in the city. I made land affordable to them. They pay me in instalments…This is my paternal land, so I have no loss. I’m not like those ‘developers’ who have sunk bank money into the land and expect a quick return. However, this does not mean that I do not make a profit. There are parties I know who have money…

Among the two broad groups of speculators observed, the first was those landowners who inherited extensive farmlands on the fringes and gradually sold them off. Because these owners had no risk factors or bank interest tied to their land parcels, they could take slow and calculated steps. They usually divided the land into plots on paper and put up signs for land sales (). Some signage included the plot layout (); otherwise, it was difficult to imagine a potential residential plot worthy of investment in the existing paddy fields. They occasionally made minor changes to the land to give potential customers an idea of the future road and plot layout (). To attract potential buyers, some set up a temporary office on the corner of the property or a nearby street intersection. The first lot of plots was sold initially at a relatively low price to build trust in the market. When the project appeared to be viable, they sought planning approval and began visible alterations to the land. Later lots were sold with a large profit margin. This process could take up to as long as ten years to complete.

Figure 4. (a) Signage for land sale; (b) land sale signage with the plot layout; (c) potential road layout; (d) Naming of the development as the ‘city’. Source: Author.

The second type had no prior land ownership on the fringes. They identified potential land for development and made contact with existing landowners, who were typically original (elite) urbanites with acres of farmland and were not interested in directly participating in land development. Instead, they granted the ‘right to sell,’ also known colloquially as ‘giving power,’ by drafting a ‘power of attorney’ document that authorises a third party to sell land on behalf of the landowner. This second group was proactive in negotiating with urban institutions and political elites to bring the necessary infrastructures to the doorstep of the land in order for their ventures to be viable. Overall, the land transformation was so pervasive in the hands of these two groups that the KDA was forced to introduce the real estate licencing and land development approval process during 2008–9 in order to gain control over widespread land use changes. Mr Alex,Footnote2 a pioneering speculator in the study area, explains the extent of the transformation:

There are 15 MouzasFootnote3 in this part of Khulna. I operate in five Mouzas…I buy land or obtain ‘power’, develop roads and plots, then give the name to the project, say, ‘Alex Nagar’ (Alex City) (). You know, these were farmland, like those in the village; I dubbed them the ‘City’. I create the imagination of the city; those who buy my land feel a part of it as well.

Informal brokerage

The fourth route involves informal brokerage practices by individuals who have taken on entrepreneurial roles and worked with absentee landholders as well as the two groups of land speculators. I call these individuals informal brokers because they have no legal or direct connections with lands, and this is not their primary occupation. This brokerage role is filled by rickshaw pullers, shopkeepers, construction workers, and many unemployed young men. They have self-selected stations, usually roadside shops, where they promote their phone numbers (). Each broker has a specific area of operation where vehicles, usually motorcycles or an e-rickshaw, are available for land inspection. They charge buyers and sellers a marginal commission based on their level of service and land value. The services usually include finding undisputed land; land inspection; locating the original landowner; sales mediation between buyer and seller; educating the buyer, who is potentially a first-time buyer, about the local land administration system; accompanying the buyer to the land office during land registration and so on. These land speculators and informal brokers had teamed up to produce peri-urban housing supplies.

Figure 5. (a) The shop with land sale signage; (b) the shop with land sale advertisement; (c) selling construction Material alongside shopkeeping; (d) construction material sales on vacant lots. Source: Author.

Later on, the brokers’ roles become even more elaborate, ranging from free advice to the landowner to numerous post-purchase ordeals. If access to the newly purchased land is difficult, or a third party has illegally occupied the plot, the broker can assist in mediating such disputes. They have assisted the buyer in obtaining a land mutation certification or finding a suitable caretaker to look after the land. Many brokers supply construction materials () and workers to work on the fence, install a water pump and perform temporary constructions. According to focus groups and interviews, these brokers also maintain connections with local institutions, such as the PDB (Power Distribution Board) or the REB (Rural Electrification Board) and help negotiate service connections. They assist the landowner in connecting with local architects, soil testing engineering firms, construction contractors, and politicians. These connections facilitate the landowner’s successful onboarding on land and subsequent housing development. As a participant pointed out,

Following the purchase, the first piece of advice I give my clients is to put up a signboard on the plot and publish the news in the local newspapers so that everyone is aware of the ownership change. We have many ‘totka’ (hands-on solutions) to save a new landowner a lot of trouble. I am the ‘medium’…Nonetheless, it is always rewarding to assist newcomers in settling in.

Incrementalism, housing supply and city-making in peri-urban Khulna

Using a relational lens to explore the four incremental housing pathways centred on urban land allows us to identify diverse actors beyond those who directly consume housing, as well as how various dwelling and non-dwelling actors come together and promote incrementalism (see ). Indeed, the housing routes observed are not just the repairing and upgradation of housing sites by urbanites, which are often a sobering highlight in informal and self-help housing literature (Bredenoord & van Lindert, Citation2010; Greene & Rojas, Citation2008). Instead, I have demonstrated the emergence of a semi-formal to largely informal, speculative land market in which localised incremental housing practices begin after the owners have secured access to land. These housing sites are not self-contained, but are embedded within Khulna’s macro-structural processes of historic housing shortage, planning and institutional deficits, rural-urban migration, and urban expansion in response to improved regional infrastructure and connectivity. Furthermore, the observed housing processes are intertwined with Khulna’s peri-urban socio-ecologies, which are constantly reproduced through incremental interventions on land.

Table 2. Incremental housing pathways informing city-wide outcomes.

I further argue that these interventions on peri-urban land have resulted in a variety of city-wide outcomes, which I have summarised in . These are collective manifestations of a self-help city. As highlighted by multiple experts:

The way housebuilding and land development took off so quickly there (on the fringes) without any plans initially (in 2003–4). It was as if people were building their own towns, those laypeople, anybody with a large piece of land wanted to become a developer… [Architect 1]

We did not issue any planning approvals for the first few years, until 2006–7, because these areas were under the jurisdiction of Batiaghata Upazilla. Later, because the (development) pressure was so intense, we began to approve as they came in, starting with a few locations… [Planning Officer 2]

By 2008–9, there had been a massive increase in private land development. We (the KDA) were compelled to issue NOCs (No Objection Certificates). By doing these, we learned a lot about where (on the fringes) development was taking place early. It was useful to know where we could intervene early… [Planning Officer 1]

Historically, the farther away from the core, the cheaper the land. Later, demand became so pervasive on the fringes that we saw the reverse effect. In 2010–11, the price was adjusted in response to what was going on in the periphery… [Architect 1]

During 2011–2012, everyone had their own version of the city. We designed some projects that were just paddy fields at the time. However, the clients could still sell them off the plan. This was insane, but it was useful for determining where and when people wanted their city… [Architect 4]

Discussion and conclusion

A relational approach has helped unpack how the four incremental housing routes have transformed Khulna’s low-lying peri-urban farmland into residential settlements, which have helped imagine and progressively materialise the city from the below. The study provides a compelling example of bottom-up, self-initiated land development and housing practices that emerged informally but were also linked to the formal at various points. As the findings suggest, absentee landholders and landowner-occupiers have taken calculative and often minimal interventions on the land to navigate institutional uncertainty in the absence of timely planning for peri-urban areas. Similarly, land developers have taken a staged approach to unlock the land to the market. The urban development authority turned a blind eye to these informal practices and intervened only on an ad-hoc basis. It is worth noting that the availability of land through legal channels was central for incrementalism to thrive, as evidenced by the literature on ‘formalised incrementalism’ (Hamid & Mohamed Elhassan, Citation2014; Wakely & Riley, Citation2011). As a result, the ways in which the housing routes and the city gradually evolved in relation to each other within an informal-formal companionship have important practical implications for rethinking planning for places where urban informality frequently outpaces the capacities of formal institutions. Given the flexibility incrementalism has provided for urban actors to meet their housing aspirations by responding to peri-urban land dynamics, it is an opportunity for urban institutions like the KDA to reconsider their role. The KDA may play a more mediating role by initiating a hybrid formal-informal governance mechanism [see Rahman and Ley (Citation2020) for examples] that ‘enables’ communities to work out their housing solutions and urban development as they see fit.

Indeed, the KDA should consider adopting flexible routes to promote formalised informality if it serves the purpose of providing accessible housing solutions for its diverse urbanites. Assume that delays in formal planning interventions are inevitable due to pre-existing institutional deficits. In that case, the KDA’s interventions should recognise the aspirations of the community for where they hope to be housed in the city, and the KDA should facilitate their progressive housing practices. Interim policies may be developed to strategically regulate prospective lands in sections of the city to satisfy the housing mobilities of the mass. This means that the KDA should reconsider its previous business-as-usual site and service developer role, which served only a tiny section of its citizens.Footnote4 Instead, peri-urban areas could be considered as larger site and service projects conceived through community and by considering their future housing mobilities in relation to accessible and affordable urban lands. This could be a practical strategy for locating the ‘right land’ (Wakely & Riley, Citation2011) for the target communities, which is required for practising incrementalism. However, care must be taken to ensure that these institutionalised informalities do not encourage land grabbing and exclusion.

In this regard, I caution that the urban fringes studied in this paper are sites of inequality and injustice brought about by the pathways of incrementalism. Although I argue that a city is being built from the ground up, that city is not without conflict and precarity. In a seemingly unregulated housing market, there are power differentials between various actors placed at different hierarchies, which likely lead to exclusions, contestations, and negotiations. For example, peri-urban land creates its own distinct hierarchies and class divisions as large landholders incrementally unlock land for profit and create an artificial land market where low- and middle-class urbanites participate. In some cases, land developers and brokers formed powerful allies to develop an artificial land market; in others, these actors have actively helped land buyers with limited financial capacities to obtain land through affordable financial packages and a range of services. Big landholders clearly had more bargaining power when it came to negotiating with institutions and political elites to get things done in their favour, such as expediting the plan approval process or getting municipal services delivered to their developments sooner. Small landholders, on the other hand, have collectively negotiated formal institutional recognition and services. With all of these dualities present, the entrepreneurial city presented in this paper should not be romanticised in any way, but future research should further look into how formal institutions negate these power differentials so that these incremental housing and city-making endeavours can continue.

Beyond practical implications, there is merit in the theoretical rethinking of the city through the organising logic of housing in it. Methodologically, a relational lens provides an appropriate level of ‘ethnographic sensibility’ in examining the housing-city nexus to trace the ‘sites and situation, revealing labours of assembling’ (Baker & McGuirk, Citation2017, p. 425) which solved housing for specific groups as well as incrementally organised their city. An openness to the housing-city metabolic interplays has helped me examine the complex processes of land appropriation and control, material flows, labour and imaginations, community formations, and the many transient practices that are ‘embodied, embedded and grounded’ in peri-urban lands (Blunt & Dowling, Citation2006, p. 691). The relational approach also considers the everyday strategies of groups who see the city as a space of ‘flexible resources’ (Simone, Citation2008, p. 200) from which to generate employment, shelter, profit and so on. The synergies that emerge from the housing-city nexus can provide a valuable foundation for approaching the city and housing solutions as ‘processual, relational, mobile and unequal’ (McFarlane, Citation2011, p. 649), where multiple urban and housing actors participate with varying levels of competencies; ‘while the process of settling may be incremental, there is a form of collective decision-making’ (Shafique, Citation2022, p. 13) which is an essential precursor for inclusive city-making. As such, the approach promises new directions for housing and urban studies based on recognising the city as an ‘incremental infrastructure’ (McFarlane et al., Citation2014) for communities to creatively self-organise their housing solutions.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to two anonymous reviewers for detailed guidance and to Afrina Noushin for helping me with the extensive documentation of landownership and land sale signages in peri-urban Khulna. Special thanks to Abigail Friendly and Femke Van Noorloos for astute SI editorial support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 Real Estate and Housing Association of Bangladesh.

2 All names were anonymised.

3 Mouza is an administrative (revenue collection) unit that corresponds to a specific land area that may contain one or more settlements.

4 Since the 1960s, KDA has delivered ten site-and-service housing projects in Khulna. The most recent, the ongoing Moyur Residential Area, is located on the south-western fringes and is intended for the high-income residents.

References

- Ahmad, S. (2015). Housing demand and housing policy in urban Bangladesh. Urban Studies, 52(4), 738–755. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098014528547

- Alam, A. F. M. A., Asad, R., & Kabir, M. E. (2016). Rural settlements dynamics and the prospects of densification strategy in rural Bangladesh. SpringerPlus, 5(1), 11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-1883-4

- Alam, A., Minca, C., & Farid Uddin, K. (2022). Risks and informality in owner-occupied shared housing: To let, or not to let? International Journal of Housing Policy, 22(1), 59–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2021.1877887

- Alam, A., McGregor, A., & Houston, D. (2018). Photo-response: Approaching participatory photography as a more-than-human research method. Area, 50(2), 256–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12368

- Alam, A., McGregor, A., & Houston, D. (2020a). Women’s mobility, neighbourhood socio-ecologies and homemaking in urban informal settlements. Housing Studies, 35(9), 1586–1606. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1708277

- Alam, A., McGregor, A., & Houston, D. (2020b). Neither sensibly homed nor homeless: Re-imagining migrant homes through more-than-human relations. Social & Cultural Geography, 21(8), 1122–1145. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2018.1541245

- Amin, A. (2004). Regions unbound: Towards a new politics of place, Geografiska Annaler: Series B. Human Geography, 86(1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0435-3684.2004.00152.x

- Amin, A., & Cirolia, L. R. (2018). Politics/matter: Governing Cape Town’s informal settlements. Urban Studies, 55(2), 274–295. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017694133

- Amin, A., & Thrift, N. (2017). Seeing like a city. Polity.

- Amoako, C., & Frimpong Boamah, E. (2017). Build as you earn and learn: Informal urbanism and incremental housing financing in Kumasi, Ghana. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 32(3), 429–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-016-9519-0

- Ashiq-Ur-Rahman, M. (2012). Housing the Urban Poor in Bangladesh: A Study of Housing Conditions, Policies and Organisations. (Doctor of Philosophy). Heriot-Watt University.

- Baitsch, T. S. (2018). Incremental Urbanism: A study of incremental housing production and the challenge of its inclusion in contemporary planning processes in Mumbai, India (Doctor of Philosophy). Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne Switzerland.

- Baker, T., & McGuirk, P. (2017). Assemblage thinking as methodology: Commitments and practices for critical policy research. Territory, Politics, Governance, 5(4), 425–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622671.2016.1231631

- BBS. (2015). Census of slum areas and floating population 2014. Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), Statistics and Informatics Division (SID), Ministry of Planning, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

- BBS. (2022). Population & Housing Census 2022 Preliminary Report Dhaka: Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics (BBS), Statistics and Informatics Division (SID), Ministry of Planning, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

- Blunt, A., & Dowling, R. (2006). Home. Routledge.

- Bredenoord, J., & van Lindert, P. (2010). Pro-poor housing policies: Rethinking the potential of assisted self-help housing. Habitat International, 34(3), 278–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.12.001

- Brenner, N., Madden, D. J., & Wachsmuth, D. (2011). Assemblage urbanism and the challenges of critical urban theory. City, 15(2), 225–240. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2011.568717

- Brickell, K. (2012). ‘Mapping’and ‘doing’ critical geographies of home. Progress in Human Geography, 36(2), 225–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132511418708

- Burgess, R. (1985). The limits of state self–help housing programmes. Development and Change, 16(2), 271–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.1985.tb00211.x

- Chiodelli, F. (2016). International housing policy for the urban poor and the informal city in the Global South: A non‐diachronic review. Journal of International Development, 28(5), 788–807. https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3204

- Cirolia L. R., Gorgens T., van Donk M., et al. (eds) (2016). Pursuing a partnership based approach to incremental informal settlement upgrading in South Africa. University of Cape Town Press.

- Cook N., Davidson A., & Crabtree L. (Eds.) (2016). Housing and home unbound: Intersections in economics, environment and politics in. Routledge.

- Cook, N., Smith, S. J., & Searle, B. A. (2013). Debted objects: Homemaking in an era of mortgage-enabled consumption. Housing, Theory and Society, 30(3), 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2013.767280

- Dovey, K., & King, R. (2011). Forms of informality: Morphology and visibility of informal settlements. Built Environment, 37(1), 11–29. https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.37.1.11

- Dunn, J. R. (2006). The meaning of dwellings: Digging deeper. Housing, Theory and Society, 23(4), 214–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036090600909568

- Ferguson, B., & Smets, P. (2010). Finance for incremental housing; current status and prospects for expansion. Habitat International, 34(3), 288–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2009.11.008

- Galuszka, J., & Wilk-Pham, A. (2022). Incremental housing extensions and formal-informal hybridity in London, United Kingdom. Questioning the formal housing imaginaries in the ‘North’. Habitat International, 130, 102692. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2022.102692

- Garland, A. M. (ed.) (2013). Innovation in urban development: Incremental housing, big data, and gender – A new generation of ideas. Wilson Center.

- Gillon, C. (2014). Amenity migrants, animals and ambivalent natures: More-than-human encounters at home in the rural residential estate. Journal of Rural Studies, 36, 262–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.09.005

- Greene, M., & Rojas, E. (2008). Incremental construction: A strategy to facilitate access to housing. Environment and Urbanization, 20(1), 89–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247808089150

- Hamid, G. M., & Mohamed Elhassan, A. A. (2014). Incremental housing as an alternative housing policy: Evidence from Greater Khartoum, Sudan. International Journal of Housing Policy, 14(2), 181–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2014.908576

- Harris, R. (2003). A double irony: The originality and influence of John FC Turner. Habitat International, 27(2), 245–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0197-3975(02)00048-6

- Huchzermeyer, M. (2011). Cities with ‘slums’: From informal settlement eradication to a right to the city in Africa. University of Cape Town Press.

- Jacobs, K., & Malpas, J. (2013). Material objects, identity and the home: Towards a relational housing research agenda. Housing, Theory and Society, 30(3), 281–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2013.767281

- Kaika, M. (2004). Interrogating the geographies of the familiar: Domesticating nature and con- structing the autonomy of the modern home. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 28(2), 265–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0309-1317.2004.00519.x

- KDA. (2002). Structural plan, master plan and detailed area plan (2001-2020) for Khulna City. Government of the Peoples Republic of Bangladesh.

- KDA. (2014). Preparation of Detailed Area Development Plan 2014 for Khulna Master Plan (2001) Area (Draft planning report). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Government of the Peoples Republic of Bangladesh.

- McFarlane, C. (2011). The city as assemblage: Dwelling and urban space. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 29(4), 649–671. https://doi.org/10.1068/d4710

- McFarlane, C., Vasudevan, A., Adey, P., Bissell, D., Hannam, K., Merriman, P., & Sheller, M. (2014). Informal infrastructures. In Handbook of mobilities (pp. 256–264). Routledge.

- Morshed, A. (2016). The politics of self-help: Women owner-builders of grameen houses in rural Bangladesh. Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review, 25(2), 7–21.

- Rahman, M. A. U., & Ley, A. (2020). Micro-credit vs. Group savings – different pathways to promote affordable housing improvements in urban Bangladesh. Habitat International, 106, 102292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2020.102292

- Roy, A. (2005). Urban informality: Toward an epistemology of planning. Journal of the American Planning Association, 71(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944360508976689

- Sarker, M. R., Siddiquee, M., & Rehan, S. F. (2008). Real estate financing in Bangladesh: Problems, programs, and prospects. AIUB Journal of Business and Economics, 7(2), 75–93.

- Shafique, T. (2022). Re-thinking housing through assemblages Lessons from a Deleuzean visit to an informal settlement in Dhaka. Housing Studies, 37(6), 1015–1034. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2021.1988065

- Simone, A. (2008). The politics of the possible: Making urban life in Phnom Penh. Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography, 29(2), 186–204. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9493.2008.00328.x

- Sowgat, T., & Roy, S. (2020). Khulna: The diversity and disparity of neighbourhoods from organic growth. http://www.centreforsustainablecities.ac.uk/research/khulna-the-diversity-and-disparity-of-neighbourhoods-from-organic-growth/?fbclid=IwAR1btT97dly3DmRL50zQySGfjYspXxCs-KZXtVrK7ULqn1ARl4btI7Hcptk

- Steele, W. E., & Vizel, I. (2014). Housing and the material imagination–earth, fire, air and water. Housing, Theory and Society, 31(1), 76–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2013.801362

- Turner, J. F. C. & Fichter, R. (eds.). (1972). Freedom to build. Macmillan.

- van Noorloos, F., Cirolia, L. R., Friendly, A., Jukur, S., Schramm, S., Steel, G., & Valenzuela, L. (2020). Incremental housing as a node for intersecting flows of city-making: Rethinking the housing shortage in the global South. Environment and Urbanization, 32(1), 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247819887679

- Vasudevan, A. (2015). The makeshift city: Towards a global geography of squatting. Progress in Human Geography, 39(3), 338–359. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132514531471

- Wakely, P., & Riley, E. (2011). The case for incremental housing. Cities Alliance.

- Waliuzzaman, S. M., & Alam, A. (2022). Commoning the city for survival in urban informal settlements. Asia Pacific Viewpoint, 63(1), 97–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/apv.12332

- Werlin, H. (1999). The slum upgrading myth. Urban Studies, 36(9), 1523–1534. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098992908