Abstract

Between 1950 and 1979 the Danish state worked to modernise Kalaallit Nunaat (a.k.a. Greenland) and concentrate the Indigenous Inuit population in a few select cities. Technologies of urban planning and development were merged with those of the colonial state. New forms of housing materialised whose qualities aligned with assimilation schemes, but were also resisted, their uses repurposed. These movements and counter-movements, I show, speak to how the built environment scripts time and temporality. Considering architecture as a ‘material politics of time’, I develop the concept of ‘temporal displacement’ in close conversation with the empirical material examined: archival materials and documents key to shaping and effectuating Danish-led policies, and documents that speak to Kalaallit’s contestation of the new types of housing being introduced. Three main aspects to temporal displacement are emphasised: (I) the eviction of the present to the past and the anachronism that follows from this; (II) biopolitical materialisations of the so-called ‘new order’; and (III) contestation by claiming contemporaneity for temporally evicted practices, activating that which hegemonic time renders as past as being in the present. The concept of ‘active past’ is suggested to capture how ideas of the past are activated in, unsettled, and renegotiated in the present.

Introduction

We lack space for storing Greenlandic food, the men go hunting and fishing and return home very dirty and smelly. Where should one put fishing gear, where chair sledges, skis, and similar things? One of our participants has previously presented our thoughts on Greenlandic provisions in Copenhagen, but has been given the answer, that this food will become extinct. On this matter there is in our group agreement, that it will last for at least fifty more years (Arnat Peqatigiit Kattuffiat, Citation1967, p. 19).Footnote1

Published in a report by the Kalaallit confederation of women’s associations, Arnat Peqatigiit Kattuffiat (APK), the above statement speaks to a new type of housing being built in Kalaallit Nunaat (a.k.a. Greenland) in the 1960s and 70s—the multi-storey apartment block.Footnote2 Four to five storeys tall, these were not large blocks by Nordic standards, but compared to the detached houses most Kalaallit households lived in, they towered in the landscape. Built just after the formal conclusion of Danish colonisation and in the decades characterised by Greenland’s Reconciliation Commission (Citation2017) as the most intensive assimilation phase of colonisation, the blocks were a result of Danish planning and policy. They also performed, I suggest in this article, a form of temporal displacement closely associated with what I conceptualise as material politics of time; a politics that, in this case, works through the materialities of dwelling to order bodies and practices in accordance to a Danish temporal order. Working in tandem with policies aimed at modernisation and centralisation, it orders by relegating places and practices deemed to be obsolete to the past, while privileging others as being of the present and having a future. I develop this argument in conversation with works from Indigenous studies and beyond that consider time and temporality as contingent and performative, local, embodied and, sometimes, contested. Emphasising how temporal contestation can play out, I suggest the concept of active past to capture how ideas and practices of the past can be activated in, unsettled, and renegotiated in the present.

Unlike much of the existing housing, the blocks built in the 1960s and 70s were equipped with amenities like hot and cold running water, showers and toilets, and central heating. This was highly appreciated by many and is considered a key factor in reduced mortality in these decades. Still, as is expressed by APK’s statement, the block architecture also displaced much of what had previously belonged in a Kalaallit home. Men returning home from hunting and fishing “lack space”, for both themselves and their equipment. Pre-existing housing had ample outdoor space for preparing larger catch, or hanging and drying meats and skins. The blocks, however, featured small kitchens and little or no space for preparing and storing desired Kalaallit foods, like different types of whale, fish, bird, berries, reindeer and, not the least, seal. This lack of space, the APK statement alerts us to, translates into a lack of time—“this food” having been classified “in Copenhagen”, the capital city of the colonial power, as on the path of extinction. Like space, this suggests, the temporalities of the built environment have an inside and an outside; they have ordering capacities and can include as well as exclude. Adding to predominant notions of displacement as spatial and physical, how can we then begin to conceptualise the temporal displacement of human and non-human bodies, objects and practices?

The concept of temporal displacement is here developed by considering 1960s and 70s block architecture in Nuuk, the capital city of Kalaallit Nunaat. Modelled after Danish social housing, this architecture came about through an extensive push to modernise Kalaallit Nunaat and, as policy documents at the time put it, “concentrate” the Inuit population in a few select places of dwelling (Grønlandskommissionen, Citation1950).Footnote3

I examine the block architecture vis à vis the political context it materialised in and show three main ways in which temporal displacement intersected with what we can recognise as Nordic colonialism. First, I argue, the so-called “new order” (ibid) of modernisation worked to evict the present to the past, a temporal displacement that rendered existing ways of living as anachronistic. Second, this ‘new’ version of the present solidified through blocks that ordered life in the most intimate ways, effectuating and materialising a biopolitics of time. Third, alongside and in tension with the new order temporality, other temporal practices persisted that not only claimed the right to dwell in specific ways, but also tie into what we can think of as the law of the land and Indigenous sovereignty. In these practices, I argue, we can locate the presence of an active past, here expressed as a present-made-past that does not settle but reasserts itself through, among other things, food procurement and storage practices.

Colonialism in and by the Nordic states lacks wide public recognition, but is the subject of a growing research field focusing especially on the Indigenous lands of Sápmi and Kalaallit Nunaat (e.g., Mayfield forthcoming, Valkonen et al., Citation2022; Lynge, Citation2006). Here, I approach Nordic colonialism by looking at planning and housing schemes conceived in Copenhagen and implemented in Nuuk. I start by introducing Nuuk and Kalaallit Nunaat, my positionality, and the article’s methodology and empirical materials. I then move to discuss literatures on temporality, colonialism and Indigenous land, before considering the temporal displacements performed through the planning and materialisation of the block architecture.

Nuuk, Kalaallit Nunaat

Kalaallit Nunaat is home to about 56,700.Footnote4 Just under 90 per cent belong to the Indigenous Inuit population; Danes form the largest immigrant group. Geographically, Kalaallit Nunaat is much closer to North America than to Europe, but due to its colonial history, its strongest political-economic ties are with Denmark. Modern colonisation commenced in 1721, first by Denmark-Norway, and from 1814, by Denmark alone. The Kalaallisut word for colony is “niuertoqarfik” (Petersen, Citation1995, p. 119). This translates into “trade centre”, reflecting how trade- and mission stations were considered by Denmark as “colonies” in a larger colony district. The Kalaallisut term for the relationship to Denmark, however, was “nunasiaq”, which is also used to describe other colonised parts of the world.

From 1721 to the outbreak of World War II, Denmark led a strict isolationist policy towards Kalaallit Nunaat, controlling trade and migration (Olsen, Citation2005). This changed with the German occupation of Denmark, which severed contact with the colonial power and resulted in increased self-government and trade with the US. When relations with Denmark resumed in 1945, demands were made for political reform, but instead of introducing self-government, Denmark opted, in 1953, to make Kalaallit Nunaat a county of the Danish Realm. This ended isolation, but marks the beginning of Danish-led modernisation. Eventually, dissatisfaction with policies made in Copenhagen and implemented in Kalaallit Nunaat led to demands for increased self-government. In 1979, Home Rule was gained; in 2009 autonomy was further increased by the introduction of Self Rule. Today, Kalaallit Nunaat is a self-governing territory under the Danish Realm, but its military defence and foreign affairs are still controlled by Denmark. Most other policy areas are governed by the democratically elected parliament, Inatsisartut, and government, Naalakkersuisut, which are seated in Nuuk.Footnote5

Situated on the west coast of Kalaallit Nunaat, the Nuuk area was taken as a settlement of Denmark-Norway in 1728 and named Godthåb. Contrary to how it is often described, this did not establish Nuuk as a place of dwelling; before colonisation it was used for summer hunting and trade.Footnote6 Nuuk is now a rapidly growing capital; major infrastructural developments have recently taken place or are underway, and its population of about 19,500 is expected to continue to increase.Footnote7

From about 1950 to 1980, several systemic forms of colonial violence were carried out, including the removal of Kalaallit children from their families for educational purposes (Thiesen, Citation2011); non-consensual implementation of contraception devices on Kalaallit children and women (DR, 2022); and, as I here focus on, the urbanisation that followed in the wake of numerous places of dwelling being closed to advance modernisation. Underpinning these actions was a form of “welfare colonialism”. According to Christensen and Arnfjord (Citation2020, p. 150), this “involved significant manipulation of the ways in which Indigenous people organised themselves spatially and socially while simultaneously implicating them in the affairs, desires, and decision-making of state powers in Denmark and then the emerging Greenlandic elite”. Here, I expand on this understanding by looking at how the technologies and rationales of the Nordic welfare state were applied in a twin effort to establish a market economy and roll out cost-efficient welfare services that could solve the so-called “Greenlandic problems” (Grønlandsudvalget, Citation1964, p. 23). A key feature to Nordic colonialism, I argue, is how these two “versions of economisation” (Asdal & Huse, Citation2023) worked in tandem to render the colony governable.

Methods and positionality

The concepts of temporal displacement, material politics of time and active past are here developed by analysing policy documents and archival materials from Nunatta Allagaateqarfia, the national archives of Kalaallit Nunaat. Produced between 1950–1971, these documents have circulated within the same bodies of government but are still of different genres: The article starts by examining two ten-year policy assessments, issued by the Danish government in 1950 and 1964 and aimed at modernising Kalaallit Nunaat. It then moves on to examine planning and policy documents that worked to materialise this policy through a new type of housing–the multi-storey apartment block. Finally, the article considers two reports from housing seminars organised in 1967 and 1970 by APK. Whereas the policy and planning documents were mostly produced in Copenhagen, these latter reports were made by Kalaallit women.

The documents are approached through practice-oriented document analysis, a methodology focused on documents as sites and agents of social action (Asdal & Reinertsen, Citation2021). Practice-oriented document analysis also looks at the wider apparatuses that documents are part of, circulate within, and function as tools of. No software and/or coding has been applied in their analysis. Instead, I have relied on repeated readings, asking what notions of time the documents enact and make effectual. What temporal practices do they include or exclude, and with what consequence?

My analysis of the documents is also informed by my positionality. I do come not from Nuuk or Kalaallit Nunaat, but from Norway. I belong to the white majority of a nation that has been implicated in and benefitted from the colonisation of both Kalaallit Nunaat and Sápmi. Norwegian perceptions of Inuit are generally problem-oriented and uninformed, which is reflected in how, when I first came to Nuuk, I expected to meet a society marred by social problems. Instead, I experienced a vibrant urbanity paired with great hospitality and lots of laughter. Having visited Nuuk at irregular intervals, since 2012, I have therefore learned to question what I ‘know’ and to be humble about what questions I take the liberty to ask and pursue. This process of learning, I acknowledge, is never complete. Nuuk and Kalaallit Nunaat are not static societies, but change, and with decolonisation, demands upon outside researchers do too. I am grateful to my colleagues and friends in Nuuk who have spent hours on end, explaining not only their experiences of Denmark and colonialism, but also how an outsider’s presence can be of value and respect Inuit ways of knowing. In many ways, these are very different from the Norwegian ways I carry with me. And yet, there are similarities too. Having grown up on a small island facing the open sea and in close relation to my grandparents and extended family, I very much appreciate how life, for many in Nuuk, revolves around being in nature and with family. Nowhere have I witnessed greater joy over the arrival of a newborn, or respect for elders, than I have in Nuuk. To learn from this is a gift whose value is beyond my words.

To learn with and from Nuuk has entailed, in my case, rethinking the authority I assume as a researcher and knowledge producer. I have learned to avoid the deficit framings I initially espoused, but also to limit what I speak to. Here, for instance, I engage with Kalaallit-authored work on time, or “piffissaq” (Noahsen, Citation2023), but the aim of my work is not to define what Inuit or Kalaallit temporalities are. Instead, I find that the documents analysed are materials to learn from about Nordic colonialism. Rather than to produce knowledge ‘about’ Inuit or Kalaallit, I examine the actions of Denmark as a colonial power and, more broadly, the characteristics of Nordic (welfare) colonialism. This also follows from the types of documents analysed. They all follow distinct formats, some answer to political procedures of parliament, others to bureaucratic bodies of planning, whilst the APK reports are produced to circulate within and speak to such the apparatuses. To trace the actions of these documents is therefore to learn, primarily, about settler time: “notions, narratives, and experiences of temporality that de facto normalise non-native presence, influence, and occupation” (Rifkin, Citation2017, p. 9). This involves recognising how Danish temporalities are asserted, but also being attentive to how these are questioned, resisted, and confronted by the temporalities they make difficult or altogether exclude. With this latter form of attentiveness, we can also begin to see contours, or translations of Kalaallit temporalities. As is demonstrated by the below discussion of piffissaq (Noahsen, Citation2023), a proper description demands embodied and emplaced engagement with temporal practices, including storytelling and oral history, which in the context of knowledge-transfer have carried far more weight in Kalaallit communities than that of writing (McLisky & Møller, Citation2021). Still, to be attentive to how Kalaallit temporalities are communicated so that they can travel also within policy documents can help understand how contestation plays out in the face of temporal displacement.

Temporality, colonialism and Indigenous land

Urban- and housing studies have a long tradition of critical analysis of displacement, but have mainly focused on its spatial and quantifiable aspects (Degen, Citation2018). Notions like sensory- or affective displacement, suggest that urban users may well ‘stay put’, but still experience a loss of place when urban environments change (e.g., Butcher & Dickens, Citation2016, Sheringham et al., Citation2023). A refreshing autobiographical take is also provided by the American geographer Bloch (Citation2022: 706), to argue for “increased reliance on the body as archive and memory as data to be used in the storytelling process about displacement and unhoming.”

These are important works whose value I do not wish to challenge. Still, as the analytical apparatuses of displacement studies predominantly assume time-space singularity, I find that they cannot capture the full import of temporal displacement: ontologically distinct temporalities that, potentially, are at odds with one another and compete for hegemony. Material politics of time, I show, can be part of such time conflicts. Activations of that rendered as past can, similarly, be a form of contestation. To draw this out I build on an interdisciplinary body of literatures, spanning works in colonial-, temporal- and Indigenous studies.

Recent research demonstrates that time is integral to the ordering, policing and distribution of dwelling (e.g., Barbosa & Coates, Citation2021 Blunt et al., Citation2021; McElroy, Citation2020; Sa’di-Ibraheem, Citation2020; Sakizlioğlu, Citation2014). Temporalities can be evoked to justify displacement, and they can emerge as its consequence. As put by the Jamaican philosopher Mills (Citation2020), “if there is a geopolitics, a politics of space, then clearly there should also be a chronopolitics, a politics of time” (Mills, Citation2020, p. 298). We must be attentive to “the contrasts, oppositions, conflicts, and struggles involved in structuring, regulating, and synchronising time” (Jordheim, Citation2014, p. 510), but also, as this article argues, to how displaced temporalities can continue to exist and be opportunities for doing time otherwise. How, then, to think about this in relation to temporal displacement in colonial processes of planning and development?

The temporal orders of colonialism are distinctly linear and progress-oriented. Identified as colonial time (Bruyneel, Citation2016) or settler time (Rifkin, Citation2017), they assert themselves as universal and singular, and order human development along a racialised timeline where the enlightened European subject is at the very frontier. Conversely, colonial time posits non-Western cultures and societies as “prehistorical and ahistorical, uncivilised, immature, and stuck in premodern development” (Hunfeld, Citation2022, p. 105)—the non-white, Indigenous subject as “backward, delinquent, deviant and irrational” (Motta & Bermudez, Citation2019, p. 428). The temporal underpinnings of colonialism thereby help justify the dispossession of land and the dominance of its peoples by denying the Indigenous subject the agentic capacities of reason and government.

Places of dwelling produced under the temporal orderings of colonialism, I argue, evoke similar valuations of progress and of the ‘old’ and the ‘new’. Notably, in the temporal displacements examined here, these distinctions break with linear time in that what is enacted as the ‘old’ refers not to something of the past, but rather takes that which is present and devalues it as outdated and obsolete, thereby evicting the present to the past. Consequently, this is a form of temporal displacement that works by an anachronistic logic, enacting modes of dwelling and being in space as misplaced in time. Still, as I also show, such enactments of the present-as-past do not always succeed. Rather, one may find that the present-as-past asserts itself and claims contemporaneity; it is an active past, one that is not settled, but instead activated and reasserted in resistance to colonial rule. Examining temporal displacement, I therefore draw attention both to how hegemonic temporalities are asserted and to temporalities that are displaced but continue to exist, however marginally, as opportunities for other times. Crucially, such co-present temporalities in tension bring out not only contestations over dwellings, but through discussions over Kalaallit versus Danish foods, over rights to live off and with land and water. At stake is not ‘only’ dwelling, but what we can recognise as Kalaallit sovereignties.

In Indigenous scholarship, the notions of land, nation and/or place are pivotal (e.g., Joks et al., Citation2020; Tuck & Yang, Citation2021; Wright et al., Citation2012). They connect to ways of life developed and passed on throughout a long history of living of, with and caring for land, water and resources, to knowledge unique to places and their people(s) and to language, culture, and spirituality. Displacement, this tells us, entails a multifaceted loss for which there is no replacement. Notions of land are also central in Indigenous writings on time and temporality. For instance, Anishinaabe scholar Awasis argues, temporalities “exist only in relation to material landscapes”, which is reflected in her interchangeable use of the terms “temporal”, “time”, “spatiotemporal” and “time-space” (Awasis, Citation2020, p. 832). The Inuit languages Kalaallisut (Noahsen, Citation2023) and Inuktitut (MacDonald, Citation1998), for their part, have no word for the abstract, Western notion of time. As explained by Kalaaleq scholar Noahsen, “there is not an isolated element or singular word for time as a succession of events whose occurrence can be measured with numbers, as commonly understood in the Western way” (Noahsen, Citation2023, p. 1). Instead, there is the word “nalunaaqutaq”, which is used to signify a clock or a watch, whilst time is translated to “piffissaq”. Much is however lost in this translation. As Noahsen emphasises, Kalaallisut is a language that carries not only meaning, but also knowledge that must be respected and handled responsibly. She then goes on to unfold a complex set of connotations carried by piffissaq, stating that “deriving from how piffissaq can be translated, the closest to an actual explanation in English is probably: The place where, or the time to do something, or opportunity for something, that has been agreed upon or is commonly known to be happening in the future” (Noahsen, Citation2023, p. 1–2). Piffisaq, then, is bound both to action and to being situated, in time and space, and to being and acting in a way that resonates with and binds the acting/emplaced/timed to others, who in some way or other shares that experience that time. Such agency, however, is not limited to the human. It is also situated in animals, plants, or other living or inert beings.

In Western social science research Inuit temporal organisation is considered as closely connected to the shifts of the seasons and movements of animals (Gombay, Citation2009; Stuckenberger, Citation2008), which in turn is contrasted to the introduction of clock time and calendars. Encounters of so-called ‘traditional’ and ‘modern’ time are often framed by deficit discourses that portray Inuit temporalities as difficult to align with, for instance, the schedules of work time or Western sleeping patterns (Stern, 2003) or the temporalities of climate science (Howe, 2010). Yet, as is demonstrated by Noahsen’s (Citation2023) unpacking of piffissaq and Kalaallit temporal emplacements, tensions between temporal orders can be interpreted with openness to difference rather than with reference to Western ideas of ‘proper’ timekeeping. In this article, I approach this by looking at how, in the APK’s housing seminar reports, negotiations of Kalaallit and Danish temporalities are not hinged on Kalaallit’s ability to understand or conform to clock time, but on their critical consideration of what time-uses are feasible, economic and, not the least, lead to a desirable way of life. Not being willing to submit to white- or colonial time does not equate with not being able to do so. Taking its cue from this, as well as from the close link being made in Indigenous scholarship between place, space and time, temporal displacement is a notion that foregrounds temporality, but relies on the spatial notion of place to describe how some temporalities are privileged, others actively excluded. And further, how non-hegemonic temporalities can persist and resist eradication through practices that weave together land, water and time.

Temporal displacement I: the eviction of the present to the past

The 1950s and 60s were in Kalaallit Nunaat a time of several political movements unfolding, often in tension (Olsen, Citation2005). State-led modernisation commenced and the Nordic model of welfare colonialism was introduced in full force. This period is often described as assimilation by Danification, but as commented by the Kalaaleq scholar Petersen (Citation2003, p. 166) it could just as well be characterised as “de-Greenlandicization”.

The stated aim of modernisation was to improve living conditions and strengthen the Greenlandic economy. The measures to achieve this were established in an assessment published in 1950, titled Grønlandskommisionens betænkning (The Greenland Commission’s Assessment), but commonly referred to as the G-50 assessment. It belonged to a specific policy document genera—the kommissionsbetænkning—a substantial assessment produced under the direction of one or more Danish ministries. Following established political procedure, it would then be considered by Parliament as a basis for passing a legal proposition; it is a policy document intended to assemble, assess, and move issues into the apparatuses of Parliament (cf. Asdal & Huse, Citation2023). The word betænkning, which also translates into consideration and deliberation, further signals that when decisions are made, they are to be based on a thorough assessment of the issue at hand.

Over the span of nine documents, the G-50 assessment introduces a development programme covering health, education, industry, settlement and housing. It underscores the importance of Kalaallit involvement and responsibility, but the authority to execute the programme is firmly placed in Denmark, under the Ministry of Greenland and the newly established agency Grønlands Tekniske Organisation, commonly referred to as the GTO (Jensen, Citation2020).

Reading the G-50 assessment with an eye for temporal orderings, one finds that the overall imperative that guides its reasoning is progress by modernisation. The key premise it sets for achieving this is to build a self-sustaining economy, which, in turn, is hinged on “concentration” of the population in a few, chosen places. Mainly three, interrelated lines of reasoning justify the concentration policy. First, the established ways of hunting and gathering, sealing especially, are no longer considered as able to sustain smaller places of dwelling—or “colonies”, “outposts” and “settlements”, as they are called in the assessment (Grønlandskommissionen, Citation1950, p. 25). The decline in sealing is described in numbers, stating that “in older time”, in West Greenland in 1908, a population of 12.500 people captured 114.000 seals, whilst in 1946/47 only 39.000 seals were captured by a population of 20.400 (Grønlandskommissionen, Citation1950, p. 22). The assessment explains the decline as partly caused by climatic changes, but also points to these as having led to larger cod stocks and new economic opportunities. As put forward in the assessment, however, to exploit these opportunities depends on the realisation of a distinct “version of economisation” (Asdal & Huse, Citation2023)—a distinct way of drawing, in this case, nature into the economy and profiting from its yields which also ties in with the second rationale for population concentration. For whereas sealing “gave food and clothing, fuel, as well as materials for kayaks and, to a certain degree, for housing”, the G-50 assessment reasons, (Grønlandskommissionen, Citation1950, p. 22), a market economy must be built around the cod. Entering modernity, the cod is not to be a subsistence animal, but a good to be exported to an international market economy. This, in turn, has consequences for how the economy to be spun around it should be organised. For instance, and with reference to the fisher, the G-50 assessment states that “it is necessary that he lives close to a place where the fish can be sold as the fisheries are based on the sale of fish and not—like sealing—on direct consumption and a subsistence economy” (Grønlandskommissionen, Citation1950, p. 23). A large fishery production, moreover, “can only be expected to be traded if industrial production of the fish can take place” (Grønlandskommissionen, Citation1950, p. 23), a statement that implicates not only fishers, but also the people intended to work at the fish processing plants. Wage workers, who along with the fishers are expected to demand “access to the purchase of consumer goods” (Grønlandskommissionen, Citation1950, p. 23), access that more easily and at lower costs can be provided for a concentrated population. Three economic subjectivities are with this enacted in the G-50 assessment—the fisher, the worker and the consumer—all dependent on living in larger places of dwelling, or “cities”, as these are designated in the assessment.

The economy outlined in the G-50 assessment stands in stark contrast to the previous policy of isolation and state monopoly on trade. As remarked, “radical change” is being introduced (Grønlandskommissionen, Citation1950, p. 22). Via nature and its shifts, from an abundance of seals to an abundance of cod, an economy is envisioned that “necessitates”, as it is put, “that the Greenlandic population is gathered in larger and much fewer residential areas” (Grønlandskommissionen, Citation1950, p. 23). The subject positions of the fisher, worker and consumer are introduced, but also nature is here being recast, from providing food, clothing, fuel and materials to being an industrial raw material and providing income in a market economy. Notably, the sharp line drawn here between subsistence and a market economy downplays that mixed economic relations were already in place, with many households being engaged in both monetary and non-monetary forms of exchange and consumption.

While the first and second rationale for concentrating the population are oriented towards income, the third is connected to the costs of providing welfare services and consumer goods to the smaller places. It is important to avoid, the assessment states, “uncritical” and “wrong investment” in “uhændsigsmæssige steder” (Grønlandskommissionen, Citation1950, p. 27)—places for which, when translating the phrase directly, there is “no purpose”. Rather, as described in the G-50 assessment, they are impracticable, unworkable and unsuitable for what is to become the ‘new’ Greenland. Here, then, a second version of economisation is at work, where the purpose of places of dwelling is tied in with the provision of services and the state’s concern for cost-efficiency. Underscoring this concern, moreover, is a sense of responsibility towards the Danish public that the cost of modernising Kalaallit Nunaat over the state budget should not be too high.

In an assessment published in 1964 and as a sequel to the G-50 assessment—the G-60 assessment—population concentration is presented with increased urgency (Olsen, Citation2005, p. 130). Unprofitable settlements “should be closed down” (Grønlandsudvalget, Citation1964, p. 32). Enacted as expenses for which there is no economic justification, entire places are devalued in the name of development and progress. For the residents this was felt in the form of defunding of critical infrastructures like schools, health services, transportation and trade, but also direct force was used, the most controversial case being the closure of the mining town Qullissat in 1972 (Haagen, Citation1982; Olrik, Citation2021).

In the G-50 and G-60 assessments, modernisation is captured by the Danish notion nyordningen—the “new order”. Tied in with numbers describing shrinking seal catches and economic justifications for the closure of places of dwelling, this is a concept that works not only by designating what is new. It also enacts existing places and ways of living of the land and sea as old. Having no purpose in the present, they are to be left behind when moving forward and into the ways of modernity. In the temporal orderings of the G-50 and G-60 assessments, these places and practices are, to borrow a line from Edgar Allen Poe (Citation1966), “Out of TIME–Out of SPACE”. The things of the new order assume the only place of privilege and with this a discrepancy arises: On the one hand, the assessments presume that time is linear and one-directional—to move with it is to progress and modernisation is to help the population “adapt to the conditions of a new age and develop in accordance with these” (Grønlandskommissionen, Citation1950, p. 19). On the other hand, and considering how the new order evicts the present to the past, an anachronism arises where that which is still in place, in time—like hunting practices and non-market forms of exchange—is enacted as old and ‘out of time’. This is the present-as-past, a form of active past that the G-50 and G-60 assessments are trying to pacify.

Temporal displacement II: biopolitical materialisations of the new order

Following the G-50 assessment, Nuuk became a place where urbanisation and modernisation unfolded not as two, but one endeavour. With some use of private contractors, the state agency GTO was responsible for planning, constructing, and maintaining near all parts of the built environment. As described by the Kalaaleq historian Jensen (Citation2020), the 1950s were characterised by much activity, but also growing frustration among Kalaallit over the lack of political influence and involvement. Instead, Danish workers migrated by the thousands to build the ‘new Greenland’. Another source of frustration was that the pace of development was too slow. The population was growing faster than anticipated and the building sector did not keep up, resulting in a severe housing shortage in the designated concentration areas.

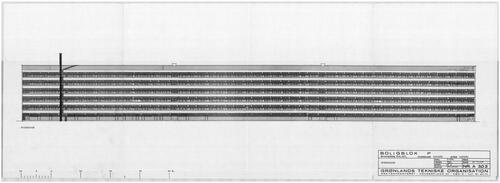

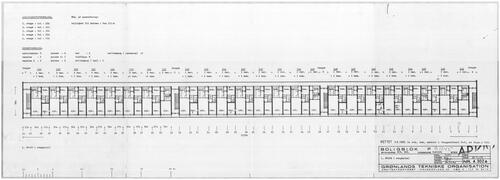

To address this, in the 60s a new type of housing was introduced—the multi-story apartment block modelled after Danish social housing. The blocks were built using prefabricated elements and materials imported from Denmark, as well as concrete produced on site, and had functionalist names like Blok 1–10 or Blok P, -Q, -R and -S. Largest of them was Blok P (see and ). 200-metres long and five storeys tall, it was situated in the centre of Nuuk and built in the years between 1965 and 1968 (Huse, Citation2015). The archival materials that speak to its construction are largely produced by the GTO and the Ministry of Greenland and include different types of documents:Footnote8 master plans, letters of correspondence within the Danish bureaucracy, telegrams of communication between Copenhagen and Nuuk, records of workers and experts travelling from Denmark to Nuuk, maps, photos, architect drawings, detailed building plans, overviews of the materials being used, budgets, cost considerations, and weekly building reports. Connecting the place of planning, Copenhagen, and the place where these plans were to materialise, what in the archival documents is called “Store slette” (“big plain”, in Kalaallisut, “Narsarsuaq”), these documents are also tools of synchronisation; “attempts to compare, unify, and adapt different times […] to synchronise them into the one homogeneous, linear, and teleological time of progress” (Jordheim, Citation2014, p. 502). Seeking to align multiple times, of Copenhagen and Nuuk, of state budgets and allocations, of materials, documents and workers travelling vast distances, these documents testify to how difficult such synchronisations are to achieve and that, quite often, they fail. The building reports, for instance, detail the progress made and challenges encountered during the building of Blok P. Evidently, the plans drawn up in Copenhagen had not considered the amounts of snow that can fall in winter, which introduced extra work and economic costs. Time, in these documents, is broken down to days in the calendar and hours of wage labour—labour that by and large had been shipped in from Denmark and therefore also required room and board.

Figure 2. Blok P, floor plan, reprinted with the permission of Nunatta Allagaateqarfia. As expressed in the two reports produced by Arnat Peqatigiit Kattuffiat, even the largest dwellings feature only small kitchens and little room for storage.

Put together, these documents tell the story of a highly technocratic, expert-driven Danish bureaucracy eager to urbanise Kalaallit Nunaat in an expedient, yet cost-effective manner. Kalaallit institutions are consulted, but the geographies of these documents—the sites where they were produced, circulated to and have effect in—show that despite Kalaallit Nunaat’s status of a colony having been lifted, the power relationship of the colony and the colonial power remains. Not only in that ruling—or urban planning—happens at a distance, but also in the forms of knowledge and expertise being applied. The technologies of urban planning and development, hereunder the apparatuses of governmental offices and the tools and techniques of architecture and engineering, are through and through Danish and they answer to the desires and constraints of the Danish state. It is by the privileging of a Danish, or Western modernity that the new housing is being built, inserting into the landscape of Nuuk the time-space of the multi-storey, working class apartment block. The apartment blocks are aimed at rationalising building costs whilst accommodating the needs of the wage-labourer and their household, meaning the Danish nuclear family, and not the often larger Kalaallit families. The new housing lends itself, in other words, to a particular rhythm of work—the one attached to the new order—but also to the family norm and consumer habits of the colonial power.

The architecture of Blok P, and the other housing blocks that looked very much like it, assert a material politics of time in at least two distinct ways. First, there is the temporality attended to in mainly Marxist analyses, whereby units of clock time are translated into monetary wages, a valuation of work that is closely related to notions of social reproduction (Thompson, Citation1967). In this case, wage-time is also racialised time as the so-called birth-place criteria meant that Kalaallit were systematically paid less than Danes, even when executing the exact same work. Alongside wage time, white time (cf. Mills, Citation2014) is imposed, whereby racialisation, white priviledge and monetary valuation of time go hand in hand. Second, the housing architecture privileges what Queer studies call “heterotemporality” (Rifkin, Citation2017, p. 39) and the life rythms of the Western nuclear family. It is to contain not the extended Kalaallit family, but mother, father and (not too many) children. Timing life in accordance to both social and biological reproduction, the housing blocks materialise the biopolitical. They are technologies that assert a particular organisation of space and time and that by virtue of their distinct materiality, cement and give durability to some modes of embodying space and time, whilst also disabling, or making others more difficult. In the case of Kalaallit Nunaat, this also meant controlling the very creation of life, as in the 1960s and 70s the so-called spiralkampagne—the IUD campaign—was rolled out.

Currently under investigation by a joint Kalaallit-Danish committee, the IUD campaign involved the non-consensual insertion of intrauterine contraception devices in half of the fertile female population from 1966 to the mid-1970s (DR 2022, Krebs, Citation2021). From 1964, when 1.674 children were born in Kalaallit Nunaat, the number of children born decreased each year, to only 671 in 1975 (Christiansen & Hyldal, Citation2022). The motivation for this grave violation of Kalaallit women’s human rights is still unclear, but a statement made by then director of the GTO, Gunnar P. Rosendahl, strongly indicates a connection to the severe housing shortage that followed in the wake of concentration and the Danish authorities’ concern for the costs of continued population growth. Under the 1971 newspaper headline of Decreasing Investment in Greenland, Rosendahl is explaining that there is no need for increased investments; instead in “the coming years” it is expected to decrease by about ten percent (Berlingske Tidende, Citation1971). “The IUD has run its course over Greenland and the healthcare system has once again played tricks on the statisticians”, he is quoted as stating whilst presenting the 1971 construction plan for Kalaallit Nunaat. In their ultimate consequence, the biopolitical orderings of the assimilation period displace not only ways of life, but the entering into time of Kalaallit children that otherwise could have been born.

Temporal displacement III: contesting colonial architecture

As a technology of colonialism, the built environment leaves a lasting imprint; it is of a materiality that is durable and lingers, so do its politics of time. It makes contemporaneous the doings of the past. Still, the two reports from APK’s 1967 and 1970 housing seminars show, architectures can also be redefined and claimed anew, rejected and contested.

Like the documents detailing the construction of Blok P, the APK reports have a strong imprint of the GTO. They are nevertheless different, as it is Kalaallit women who decide what issues to raise. From the reports one learns that the seminars were held in Nuuk and went on for ten days. There were excursions and discussions among the participants, who were mainly from the west coast, a few from the east coast. Various experts, many of them recognisable as authors of the Blok P documents, held lectures.

The 1967 report is published by the GTO. It is organised by foregrounding the “technical lectures” held by the (Danish, male) experts, with the (female, Kalaallit) participants’ discussions summarised at the end of these. In the 1970 report, self-published by APK, lecture summaries have been moved to the back and discussions are worked into themes. Introducing the report is a four-page list of statements. Some are overarching, such that the Kalaallit population must be included in decision-making processes; others attend to detail. For instance, that “there should be room for a refrigerator in the kitchen, freezer in the dwelling and opportunity for storing Greenlandic provisions” (Arnat Peqatigiit Kattuffiat, Citation1970, p. 6). It is through this demand and, more generally, the reports’ problematisation of the relationship between architecture and food, that contestation of the new blocks most clearly comes into view.

As shown in the statement quoted in the introduction, the architecture of the blocks did not accommodate the procurement, preparation and storage of Kalaallit foods. It is an architecture that has no space for the subsistence economies that the G-50 and G-60 assessments evict to the past, only the ways of the ‘new’ get to enter. The contradistinction made between extinct and surviving foods further brings into question the colonial narrative of the disappearing Native—a figure whose Indigeneity is seen to dissolve as it assimilates (Stuhl, Citation2017). Still, to emphasise cultural erasure only is to grossly overlook, even undermine, the agency of the APK reports. Contesting the view presented in Copenhagen, that these preferred foods will soon be of the past, the 1967 report not only asserts that this food will survive “for at least fifty more years”, it also recommends that in future housing, space should be made to accommodate it (Arnat Peqatigiit Kattuffiat, Citation1967, p. 19). Kalaallit foods, the reports demonstrate, are still being consumed; the anachronism inherent in the G-50 and G-60 policies being challenged by the stubborn presence of practices relegated to past. This is not a strident form of resistance, but a contestation nonetheless, one not dissimilar to what Anishinabe scholar Vizenor (Citation2008) designates as survivance and which speaks to how Indigenous peoples have maintained their ways of life amid colonial violence.

In Greenland, the 1967 report explains, one uses foods acquired during different seasons. This invokes time that is not linear, but cyclical, not progress-oriented, but nature-oriented; time that must be accommodated by providing space for the material practices that come with it. One needs storage for hunting equipment, suitable places to prepare the catch. Large quantities of food captured during the one season, to last to the return of the next, need cold and dry storage spaces, which is also something that the modern apartment does not provide: “Examples from modern multi-storey buildings were told, about Greenlandic provisions that go to waste because the residents do not have the opportunity to store it properly” (Arnat Peqatigiit Kattuffiat, Citation1970, p. 22). Along with the cyclical time of food seasons another temporality comes to view, one of managing time by slowing it down and making foods last. If not done properly, the work of procurement and preparation, along with the food, goes to waste, but if stored right, the yields of one time can be used and enjoyed in another. Towards that enjoyment, however, the APK reports make yet another claim. For as many have found, the dining areas of the apartments are far too small for the entire family to eat together. As put in the 1967 report, “Why are there so small kitchens with dining space for 4 people, when our families normally are much larger, so that one must take turns eating?” (Arnat Peqatigiit Kattuffiat, Citation1967, p. 20). Even mealtime is being disturbed with this new architecture, the reports stating quite firmly that one prefers that space for shared meals is prioritised in future dwellings.

The APK reports are both critical and constructive. They contest the architectures being produced and the power structures that enable them, but are also suggestive of how things could be done differently and by whom. Through this, the contours of what could be described as a Kalaallit-premised modernity come to view. On the one hand, the participants express an eagerness to use new household appliances and satisfaction with many of the amenities that the blocks offered. On the other, they claim space for that which modernisation displaces, such as Kalaallit foods and large households. What is envisioned is housing that simultaneously embraces goods associated with modernity and makes room for Kalaallit lifestyles; a mode of dwelling where that which came before is not displaced to the past but valued as part of the future. How to balance such concerns is not a matter of consensus, but in contrast to Danish policy documents, where such discussions are absent, the reports give space for Kalaallit deliberation over desired architectural futures:

Some found it quite unnecessary to hang bird catch and provisions outside the windows and pointed out the un-aesthetical in seeing plastic bags and newspaper wrapped parcels, often poorly packed, and in other cases unpacked pieces of meat or bird catch hanging outside the windows, sometimes with blood running down the wall. Others found that these were conventional considerations that did not belong in Greenlandic built environments. When it is was a fact that one goes hunting, and that the population was happy to eat the catch, one would also have to acknowledge that it must be stored. That this happens outside the houses is an old tradition. Many provisions benefit from hanging outside in the dry air, on the contrary one could consider this differently, that this provision contributes to giving the Greenlandic residential areas character: One could see, that this is Greenland (Arnat Peqatigiit Kattuffiat, Citation1970, p. 22).

In the decades after World War II, the role of the Danish housewife was changing (Leilund, Citation2012). Restricted resource access in the aftermath of war, especially of imported goods, created incentive to reduce household consumption. The housewife should be as prudent as possible, and “exploit the vitamins, calories, kroners and øre and her own physical strength optimally” (Leilund, Citation2012, p. 47, my translation). Schools of home economics were being opened in great numbers, women’s associations were established, courses held, and school kitchens established, all aimed at training women in the practical and moral sides to this household ideology. Part of the emerging welfare state and its intimate forms of governing bodies, this ideology introduces new modes of economising the home and women’s work—an economisation that in conjunction with Kalaallit Nunaat must be considered alongside the versions of economisation that followed in the wake of the new order.

The APK reports testify to an eagerness to be good housewives, as do other archival materials associated with APK and its leadership (see also Arnfred & Pedersen, Citation2015), but here also a Kalaallit-premised version of what this entails comes to view. For instance, and staying with the question of food, the women were not satisfied with how lacking storage encouraged “small purchases” (Arnat Peqatigiit Kattuffiat, Citation1967, p. 20) at supermarkets. What marketing often describes as ‘convenience shopping’, the women found was not convenient at all. Shopping in small quantities, they held, was more expensive, time consuming and increased the workload of the housewife. Instead, what the reports envision is a mixed economy, where foods acquired through non-monetary economies are combined with consumer goods.

Whilst not raised in the reports, the issue of food procurement also connects to how land is organised in Kalaallit Nunaat. As there are no private property rights to land in Kalaallit Nunaat, a common misconception is that the land, ocean, and their resources belong to no one and are free to all (Brøsted, Citation1986; Petersen, Citation1981, Citation2003). Rights to land and water, as practised, however suggest otherwise. Through sustained use and in understanding with the community they are part of, individuals, groups and/or families can gain rights to specific resources and places, which includes rights to hunt and fish, to tenting grounds and so forth. Rather than being free to all, this shows that land and water are regulated through an intricate net of rights and privileges upheld through use. And further, that the procurement of food is not only linked to sustenance, but to upholding what current literatures would designate as Indigenous sovereignties (e.g., Moreton-Robinson, Citation2020). In the period leading up to Home Rule in 1979, and so culminating in the years in which the housing seminars are being held, Kalaallit were experiencing increased interference by public law and significantly increased pressure towards their rights to land, water and resources (Brøsted, Citation1986). Centralisation had removed entire communities from the places they had rights to, leaving some places without the continued patronage of their rights holders whilst creating new pressures in the places set to grow—pressures that included the uses of the emerging fishing industry as well as desires for a mining and petroleum industry. The assertion that one’s food will not become “extinct”, but should continue to be part of the everyday, the return of the seasons marking continuance and time come again, can as such be seen to tie in with the assertion of rights to land and water, of Inuit sovereignty amidst the pressures of Nordic colonialism.

Times for doing otherwise

Urban- and housing studies, I argue in this article, need to consider more closely the temporalities invoked to justify and order displacement. When the ‘new’ is to replace the ‘old’, what ways of performing time are at stake and to what consequence? This foregrounds what Mills (Citation2020) calls chronopolitics—the politics of time—and necessitates a sensitivity towards temporal multiplicity. I have here approached this by putting the critical concerns of displacement studies into conversation with literatures on colonial-, white- and Indigenous time and temporalities. Indigenous studies, I find, inform the study of displacement and temporality in crucial ways. More than works that rely on Western analytical apparatuses, the field brings out how time-space multiples play out in the uses of land, water and resources. It also demonstrates how high the cost of displacement is, land being not ‘only’ a place of dwelling, but deeply connected to culture and spirituality, to maintaining history and living well. These are sensitivities that scholarship engaging with precarious dwelling can learn from in developing analytical apparatuses more attuned to time-space multiplicity and relationality.

As a contribution to this, I suggest the concepts of temporal displacement, material politics of time and active past. With temporal displacement I bring attention to the temporal aspects of displacement. Time and its orderings, I show, can work through a variety of technologies and arrangements, ranging from those of ‘large’ state policy and planning schemes, to concrete architectural imprints and other, more mundane fabrics of the everyday. Material politics of time speaks quite directly to the latter. It highlights how chronopolitics can work through mundane materialities—e.g., housing architecture and food infrastructures—but also tie in with orderings at other, perhaps more extensive scales. For instance, this article shows, material politics of time can tie in with the biopolitical orderings of the colonial state or, conversely, with upholding Indigenous sovereignties.

As is shown in this and several other studies (e.g., Hunfeld, Citation2022; Motta & Bermudez, Citation2019; Stuhl, Citation2017), a key mode of asserting colonial time is to evict that which is present to the past, rendering Indigenous peoples and cultures as underdeveloped and/or obsolete. When this effort to evict the present to the past fails, it can take on the quality of what I here describe as an active past. This is a concept that speaks to how the past can be activated in and act upon the present, but also, in this case, to how the boundaries of the old and the new, the past and the present can be unsettled and contested, with co-present and conflicting temporalities (re)claiming space.

Active past brings our attention to how times for doing otherwise exist, as opportunities for resistance, for endurance and survivance. For just as spatial displacement can be contested, eviction overturned, so can temporal displacement. As is so clearly stated in the quote this article started out with, what the colonial power deems soon to be extinct, others find will last, an assertion that in the case of APK was followed up by organising and putting forward demands, for political influence and for architectures better attuned to their desired way of life.

Acknowledgements

I extend a great and humble thanks to Inuit knowledge holders who have shared their experiences and worldviews with me. Qujanarujussuaq, Julie Edel Hardenberg, Marianne Jensen, Vivi Noahsen, Kistâra Motzfeldt Vahl and Vivi Vold. Thank you for having the patience to correct my thinking, and for generously sharing with me many of the delicious Kalaallit foods being enjoyed in Nuuk. Together with colleagues at Nunatta Allagaateqarfia, Vivi Noahsen has also given invaluable guidance in the national archives of Kalaallit Nunaat. A warm thanks to collaborating partners and colleagues at Ilisimatusarfik – the University of Greenland, Steven Arnfjord and Inge Seiding, and to partners and friends at Nunatta Katersugaasivia Allagaateqarfialu – Greenland National Museum and Archives, and Nuutoqaq – Nuuk Local Museum. I thank the UrbTrans research group at UiT The Arctic University of Norway, Anna Andersen, Anna Jensine Arntzen, Prashanti Mayfield, Martin Svingen Refseth and Hanne Hammer Stien, and the STS research group at TIK Centre for Technology, Innovation and Culture, University of Oslo, who have read and discussed early drafts of this article. Lastly, I wish to thank the editors of the special issue for their instructive feedback on the article, as well as the two anonymous reviewers, who both gave highly valuable feedback in the final stages of writing.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 All archival- and policy documents examined in the article are written in Danish, quotes were translated to English by the author.

2 Kalaallit Nunaat is the Inuit name for that which in English is commonly called ‘Greenland’, in Danish ‘Grønland’. I will here use Kalaallit Nunaat when it is my own mentioning of the nation, but do not change the use of ‘Grønland’ (translated as ‘Greenland’) where it is mentioned by others. Similarly, instead of ‘Greenlander’ the Kalaallisut terms ‘Kalaaleq’ (singular) and ‘Kalaallit’ (plural) are used to denote Inuit who live in Kalaallit Nunaat.

3 Following a comment in a recent draft for a four-year plan for physical planning and maintenance, Naalakkersuisut (Citation2023: 17) raises the question of whether one should stop using the ‘late colonial’ terms ‘city’ (illoqarfik) and ‘village’ (nunaqarfik) and instead use the ‘modern’ notion of ‘place of dwelling’ (inoqarfik). In line with this, the article uses the denomination ‘places of dwelling’. The policy draft is available here, in Danish and Kalaallisut: https://naalakkersuisut.gl/-/media/publikationer/finans/2023/nunatamakkerlugu-pilersaarusiorneq-digitale-version-2023-05-03.pdf (accessed November 29, 2023).

4 https://stat.gl/dialog/main.asp?lang=da&sc=BE&colcode=o&version=202304 (accessed November 7, 2023).

5 For an English translation of the Act on Greenland Self-Government see: https://naalakkersuisut.gl/∼/media/Nanoq/Files/Attached%20Files/Engelske-tekster/Act%20on%20Greenland.pdf (accessed October 16 2021).

6 Personal conversation with Inge Bisgård, June 2022.

7 https://bank.stat.gl/pxweb/da/Greenland/Greenland__BE__BE01__BE0120/BEXSTC.px/table/tableViewLayout1/(accessed December 4 2022) .

8 Access to these materials were granted by Nunatta Allagaateqarfia, the national archives of Kalaallit Nunaat, and government owned company ASIAQ Greenland Survey.

References

- Arnat Peqatigiit Kattuffiat. (1967). Rapport om boligseminar i Godthåb Okotber 1967. GTO.

- Arnat Peqatigiit Kattuffiat. (1970). Rapport om boligseminar II I Godthåb. GTO.

- Arnfred, S., & Pedersen, K. B. (2015). From female shamans to Danish housewives: Colonial constructions of gender in Greenland, 1721 to ca. 1970. NORA - Nordic Journal of Feminist and Gender Research, 23(4), 282–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/08038740.2015.1094128

- Asdal, K., & Huse, T. (2023). Nature-made economy: Cod, capital, and the great economization of the ocean. MIT Press.

- Asdal, K., & Reinertsen, H. (2021). Doing document analysis: A practice-oriented method. Sage.

- Awasis, S. (2020). "Anishinaabe time": Temporalities and impact assessment in pipeline reviews. Journal of Political Ecology, 27(1), 830–852. https://doi.org/10.2458/v27i1.23236

- Barbosa, L. M., & Coates, R. (2021). Resisting disaster chronopolitics: Favelas and forced displacement in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 63, 102447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102447

- Berlingske Tidende. (1971). Dalende investering i Grønland: Spiralen og nedgang i fiskeriene har ændret Grønlands udvikling. Berlingske Tidende.

- Bloch, S. (2022). For autoethnographies of displacement beyond gentrification: The body as archive, memory as data. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 112(3), 706–714. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2021.1985952

- Blunt, A., Ebbensgaard, C. L., & Sheringham, O. (2021). The “living of time”: Entangled temporalities of home and the city. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 46(1), 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12405

- Brøsted, J. (1986). Territorial rights in Greenland: Some preliminary notes. Arctic Anthropology, 23(1/2), 325–338.

- Bruyneel, K. (2016). The trouble with amnesia: Collective memory and colonial injustice in the United States. In G. Berk, D. C. Galvan, & V. Hattam (Eds.), Political creativity: Reconfiguring institutional order and change (pp. 236–257). University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Butcher, M., & Dickens, L. (2016). Spatial dislocation and affective displacement: Youth perspectives on gentrification in London. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40(4), 800–816. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12432

- Christensen, J., & Arnfjord, S. (2020). Resettlement, urbanization, and rural-urban homelessness geographies in Greenland. In I. Côte & Y. Pottie-Sherman (Eds.). Resettlement: Uprooting and rebuilidng communities in Newfoundland and Labrador and beyond (pp. 143–180). Memorial University Press.

- Christiansen, A., & Hyldal, C. (2022). Inge Thomassen: Jeg fik også spiral uden at vide det. Og den gjorde mig steril. Kalaallit Nunaata Radioa. Retrieved May 7, 2024, from https://knr.gl/da/nyheder/inge-thomassen-jeg-fik-ogs%C3%A5-spiral-uden-vide-det-og-den-gjorde-mig-steril

- Degen, M. (2018). Timescapes of urban change: The temporalities of regenerated streets. The Sociological Review, 66(5), 1074–1092. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026118771290

- DR. Podcast series. (2022). Spiralkampagnen. Retrieved December 3, 2023, from https://www.dr.dk/lyd/p1/spiralkampagnen-3510654808000.

- Gombay, N. (2009). Today is today and tomorrow is tomorrow: Reflections on Inuit understanding of time and place. In INALCO Proceedings of the 15th Inuit Studies Conference, Orality.

- Greenland’s Reconciliation Commission. (2017). Vi forstår fortiden. Vi tager ansvar for nutiden. Vi arbejeder for en bedre fremtid. Grønlands forsoningskommission: Nuuk.

- Grønlandskommissionen. (1950). Grønlandskommissionensbetænkning 1: Innledning. Placering og uforming af bebyggelser. Den fremtidige anlægsvirksomhed. I. S. I. Møllers Bogtrykkeri.

- Grønlandsudvalget. (1964). Grønlandsudvalget. Betænkning fra af 1960 Betænkning nr. 363. S. I. Møllers Bogtrykkeri, København.

- Haagen, B. (1982). The coal mine at Oullissat in Greenland. Etudes/Inuit/Studies, 75–97.

- Hunfeld, K. (2022). The coloniality of time in the global justice debate: De-centring Western linear temporality. Journal of Global Ethics, 18(1), 100–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449626.2022.2052151

- Huse, T. (2015). Architectural imprints of colonialism in the Arctic. The Postcolonial Arctic, 15(12), 19–27.

- Jensen, M. (2020). Postkoloniale ofre eller selvforskyldte problemer? - beslutningsprocesser i anlægsvirksomheden 1950-60 [Masters thesis]. Ilisimatusarfik – The University of Greenland.

- Joks, S., Østmo, L., & Law, J. (2020). Verbing meahcci: Living Sámi lands. The Sociological Review, 68(2), 305–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026120905473

- Jordheim, H. (2014). 1. Introduction: Multiple times and the work of synchronization. History and Theory, 53(4), 498–518. https://doi.org/10.1111/hith.10728

- Krebs, M. L. (2021). Staten tog min møydom. Sermitsiaq. AG. Published online June 30, 2021.

- Leilund, S. (2012). Det havde været mere rationelt straks at lægge pengene i skraldespanden… Madspild og husmoderdyder mellem materialitet og ideologi. Kulturstudier, 3(2), 43–72. https://doi.org/10.7146/ks.v3i2.7639

- Lynge, A. E. (2006). The best colony in the world. Rethinking Nordic Colonialism. Retrieved December 3, 2023, from https://www.rethinking-nordic-colonialism.org/files/pdf/ACT2/ESSAYS/Lynge.pdf.

- MacDonald, J. (1998). The Arctic Sky: Inuit astronomy, star lore and legend. Toronto.

- Mayfield, P. (forthcoming). States of exeptionalism: Unsettling nordic colonial technologies [Unpublished manuscript].

- McElroy, E. (2020). Property as technology: Temporal entanglements of race, space, and displacement. City, 24(1–2), 112–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2020.1739910

- McLisky, C., & Møller, K. E. (2021). The uses of history in Greenland. In A. McGrath & L. Russel (Eds.), The Routledge companion to global indigenous history (pp. 690–721). Routledge.

- Mills, C. W. (2014). WHITE TIME: The chronic injustice of ideal theory 1. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 11(1), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X14000022

- Mills, C. W. (2020). The chronopolitics of racial time. Time & Society, 29(2), 297–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X20903650

- Moreton-Robinson, A. (Ed.). (2020). Sovereign subjects: Indigenous sovereignty matters. Routledge.

- Motta, S. C., & Bermudez, N. L. (2019). Enfleshing temporal insurgencies and decolonial times. Globalizations, 16(4), 424–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/14747731.2018.1558822

- Naalakkersuisut. (2023). Pisariaqartumik iluarsartuussineq Nuna tamakkerlugu pilersaarusiorneq pillugu nassuiaat 2023/ Det nødvendige vedligehold Redegørelse om landsplanlægning 2023. Department of Finance and Equality, Greenland’s Self Rule. N Offset, Nuuk.

- Noahsen, V. (2023). Piffissaq Unpublished working paper.

- Olrik, M. B. (2021). De tvangsflyttede -Deres oplevelser. Deres viden og meninger om Grønlands Forsoningskommission [Bachelor thesis]. Ilisimatusarfik – The University of Greenland.

- Olsen, R. T. (2005). I skyggen af kajakkerne: Grønlands politiske historie 1939-79. Nuuk.

- Petersen, R. (1981). Principper og problemer omkring kollektiv ret til jorden. Retfærd i Grønland. Modtryk AmbA.

- Petersen, R. (1995). Colonialism as Seen from a Former Colonized Area. Arctic Anthropology, 32(2), 118–126.

- Petersen, R. (2003). Settlements, kinship and hunting grounds in traditional Greenland (Vol. 27). Museum Tusculanum Press.

- Poe, E.A. (1966). Complete stories and Poems by Edgar Allen Poe. Doubleday.

- Rifkin, M. (2017). Beyond settler time: Temporal sovereignty and indigenous self-determination. Duke University Press.

- Sa’di-Ibraheem, Y. (2020). Jaffa’s times: Temporalities of dispossession and the advent of natives’ reclaimed time. Time & Society, 29(2), 340–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X20905974

- Sakizlioğlu, B. (2014). Inserting temporality into the analysis of displacement: Living under the threat of displacement. Tijdschrift Voor Economische En Sociale Geografie, 105(2), 206–220. https://doi.org/10.1111/tesg.12051

- Sheringham, O., Ebbensgaard, C. L., & Blunt, A. (2023). ‘Tales from other people’s houses’: Home and dis/connection in an East London neighbourhood. Social & Cultural Geography, 24(5), 719–737. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2021.1965197

- Stuckenberger, A. N. (2008). Sociality, temporality and locality in a contemporary Inuit community. Études/Inuit/Studies, 30(2), 95–111. https://doi.org/10.7202/017567ar

- Stuhl, A. (2017). The disappearing Arctic? Scientific narrative, environmental crisis, and the ghosts of colonial history. In Arctic environmental modernities: From the age of polar exploration to the era of the Anthropocene (pp. 21–42).

- Thiesen, H. (2011). For flid og god opførsel: Vidnesbyrd fra et eksperiment. Nuuk.

- Thompson, E. P. (1967). Time, work-discipline, and industrial capitalism. Past and Present, 38(1), 56–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/past/38.1.56

- Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2021). Decolonization is not a metaphor. Tabula Rasa, 38, 61–111.

- Valkonen, S., Alakorva, S., Aikio, Á., & Magga, S.-M. (eds) (2022). The Sámi world. Taylor & Francis.

- Vizenor, G. (2008). Aesthetics of survivance: Literary theory and practice. In G. Vizenor (Ed.), Survivance: Narratives of native presence (pp. 1–24). Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska.

- Wright, S., Lloyd, K., Suchet-Pearson, S., Burarrwanga, L., Tofa, M., Bawaka Country. (2012). Telling stories in, through and with Country: Engaging with Indigenous and more-than-human methodologies at Bawaka, NE Australia. Journal of Cultural Geography, 29(1), 39–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873631.2012.646890