Abstract

As with many Anglophone nations, Australia displays a dualistic housing system dominated by private ownership and private rental, both of which demonstrate an ongoing and intensifying lack of affordability. Despite extensive public subsidisation, rates of ownership have dropped in recent years while the proportion of renters is increasing. Alongside calls for private rental reforms to make this more appropriate as a form of long-term tenure, there is growing interest in intermediate tenure forms to allow easier access to ownership, ease the pressure on the country’s marginalised social housing, and provide a greater range of options. Due to their small scale and relative newness in Australia, intermediate tenures such as shared equity, community land trusts, and housing co-operatives remain under-researched and unfamiliar, with previous research showing limited interest in shared equity products amongst potential buyers. This paper presents data from more recent focus groups amongst would-be buyers, showing latent market interest in resale-restricted products, with policy and market implications of both national and international relevance. The work also highlights a role for research in fostering awareness and understanding of such models.

Introduction

Since the second World War, in Australia as with other Anglophone nations, market-rate home ownership has been promoted and supported as the preferred housing tenure by policy makers, the media, financial institutions, and the public at large (Ronald, Citation2012; Troy, Citation2012). That focus generated high homeownership rates in Australia throughout the second half of the twentieth century, exceeding 70 per cent in the national population censuses of 1961, 1966, 1981, and 1986. In recent years, this rate has started to decline as housing price growth has outstripped wage growth; CoreLogic (Citation2022) placed Australian wage growth over the prior 20 years at 81.7%, compared to home value growth at 193.1%.

As home ownership has started to decline in that context, private renting has increased as a proportion of the housing system, such that in the 2021 census, 30.6 per cent of households were renting their homes, 35 per cent owned their homes with a mortgage, and 31 per cent owned their homes without debt. This comprises a total of 66 per cent in ownership. The 2021 rates changed from the 1991 levels of 26.9 per cent (+3.7%), 27.5 per cent (+7.5%), and 41.1 per cent (-10.1%) respectively, showing a marked shift towards more people in indebted ownership and more people renting (Australian Bureau of Statistics, Citation2022).

The increasing demand for renting has driven rents up in all major cities and many regional centres, such that in 2024, a widely-used annual national snapshot of rental affordability recorded both the lowest number of rental properties available and the lowest rates of affordability on record, noting that on average, rents had increased 8.5 per cent in the previous 12 months (Anglicare Australia, Citation2023). That report showed that of the 45,115 homes listed for rent across the entire country, less than 0.2 per cent were affordable for households on unemployment benefits; in most instances, the figure was closer to 0 per cent (Anglicare Australia, Citation2023). Australia’s public rental housing system provides affordable rental homes with rents usually indexed to income but is a minor part of the housing system at under five per cent of all stock and falling far short of demand.

The above affordability challenges are prompting exploration of affordable ownership options to provide access to home ownership in Australia. This is partly to enable the stability of ownership, but also to move moderate income households out of private and social renting in order to free up stock and reduce demand pressures on both sectors. Internationally, a range of affordable ownership options have been established, using a variety of legal mechanisms to provide upfront affordability and for many, also ongoing affordability via a range of resale restrictions (see Davis, Citation2006; Monk & Whitehead, Citation2010). These vary in the level and treatment of any equity that residents invest in their homes and in their focus on upfront and/or ongoing affordability, which may include restriction of equity gains at resale to retain affordability to subsequent buyers.

Australia’s affordable ownership landscape is tiny and comprises shared equity models that have yet to be tested for affordability retention at resale. These include models in which the government holds a second mortgage on the home; for example, KeyStart in which the Western Australian state government is the partner, and the federal government’s recently announced first home buyer’s scheme, Help to Buy (OwnHome, Citationn.d.). Previous Australian research into shared equity that proposed hypothetical models suggested buyers would prefer fewer resale restrictions and favour models that allow them to buy the partner organisation out over time by staircasing to full ownership (Pinnegar et al., Citation2010). However, those features are characteristic of international models that can struggle to retain affordability and/or struggle to enable staircasing in a straightforward manner (see Clarke & Heywood, Citation2012; Jacobus & Lubell, Citation2007). More recently, Milcheva et al. (Citation2023, p. 7) reviewed models in which occupants can buy out their equity partner and thereby ‘staircase’ to full ownership, finding that ‘[o]ver the last 7 years, the value of the staircased share has increased by 60% reflecting higher house prices, which carries the implications that [shared ownership] is becoming less affordable’.

Significantly, the hypothetical resale-restricted ‘community equity’ model presented in the previous Australian study did not readily align with any current international model of shared equity, shared ownership, or intermediate tenure. Consequently, this paper presents results from pilot focus groups that discussed models that carry tighter resale restrictions and do not allow staircasing, based on existing international models with an evidence base of successes and failures. The focus groups presented models based on community land trust (CLT) principles of permanent affordability to households currently looking to buy in a major city, but unable to afford full market prices. The results presented focus on the households’ characteristics and current circumstances, and on participants’ responses to the models presented to them. The focus group participants’ overwhelming interest in resale-restricted leasehold and co-ownership models, with no stated preference for either form, suggests there is a latent market for models that can deliver ongoing affordability and retain homes as permanently affordable stock. Further, the focus groups revealed a range of housing aspirations that were not dominated by expectations of capital gain and that related more to ontological and social aspects of home, such as stability, choice, and agency. These aspirations offer a basis for diversifying housing stock beyond the dualistic market configuration of many Anglophone nations, of either market-rate ownership or insecure rental models. They also offer insights into possible reform of extant tenures to more appropriately deliver residents’ aspirations.

Background – the rationale and terrain of intermediate tenures

Home ownership for low- and, increasingly, moderate-income households can be elusive and precarious. To enable home ownership for such households, the United States of America (USA), United Kingdom (UK), and many European nations are adopting various models of ‘intermediate tenures’ that sit between owning and renting with regards to core features of tenure, such as the nature and extent of resident equity, and the ability to make and capitalise on improvements to the built form (Monk & Whitehead, Citation2010). In the UK, ‘shared equity’ models have dominated this landscape; in these, the resident and a partner organisation co-own property, with the resident paying a mortgage on their share as well as rent on the partner’s share. Residents may have the capacity to ‘staircase’ to full ownership by incrementally buying greater proportions of the home’s value from the partner organisation. While staircasing may be intuitively or financially appealing, studies to date have shown it can be cumbersome and off-putting (e.g., Clarke & Heywood, Citation2012) or erode affordability (Milcheva et al., Citation2023), and some argue it may reduce the pool of affordable homes and/or create need for further subsidisation to replace the affordable homes that have been bought by residents (Jacobus & Lubell, Citation2007).

In the USA, several models occupy the space between renting and owning; Jacobus and Lubell (Citation2007) refer to this spectrum as comprising subsidy recapture, shared appreciation loans, and subsidy retention. Those authors also refer to ‘shared equity mortgages’ as privately financed schemes, but do not discuss them. The subsidy recapture and shared appreciation models described by Jacobus and Lubell (Citation2007) are roughly analogous to current Australian shared equity programmes as, similar to the USA models, these rely on government or non-profit co-ownership.

In addition to those two models (subsidy recapture and shared appreciation, ‘shared equity homeownership’ in the USA collectively refers to the subsidy retention models of community land trusts (CLTs), limited equity cooperatives (LECs), and deed-restricted mortgages (see Davis, Citation2006; Ehlenz & Taylor, Citation2019). These are almost entirely absent from the Australian housing landscape. While varying in their legal forms and instruments, shared equity homeownership models all aim to retain affordability in perpetuity, so prevent staircasing and contain resale restrictions in their legal agreements. In CLTs and LECs, residents either lease the property from, or co-own their property with, the relevant non-profit organisation. In contrast, deed restricted mortgages often do not have an administering organisation and so can be hard to enforce over time (Davis, Citation2006). While LECs currently are not growing in number, there is increasing interest in and uptake of CLTs, partly due to their robustness during the USA’s mortgage foreclosure crisis (see Thaden, Citation2011). Due to that success, CLT interest and uptake is also growing rapidly in the UK, with 350 CLTs established and over 200 forming as at 2023 (Community Land Trust Network, Citation2023) Similarly, their uptake is now increasing across Europe, Africa, and Australasia, due to both their ongoing affordability controls and focus on community input into governance and programming. This includes exploration in Australia and Aotearoa/New Zealand and their examination as an alternative to market-based responses to informal settlements in the Global South (e.g., Crabtree et al., Citation2013, Citation2019; Basile & Ehlenz, Citation2020; Midheme & Moulaert, Citation2013; Rose, Citation2018).

As highlighted earlier, in Australia, shared equity models administered by State or Territory governments are emerging in the intermediate tenure space, while registered community housing providers (CHPs) that provide housing as rentals indexed to the incomes of very low through to moderate income households have also shown interest in shared equity models (e.g., Regional Development Australia, Citation2014). As affordability has continued to worsen, Australian research has examined the policy lessons from international examples of demand-side and supply-side options for first home buyers, including a limited review of shared equity and shared ownership schemes (e.g., Pawson et al., Citation2022). Most recently, the Australian federal government has committed to its Help to Buy scheme, a demand-side shared equity programme for first home buyers in which the government provides a loan for a proportion of the home price (OwnHome, Citationn.d.). Notably and echoing earlier research highlighting the inflationary effect of demand-side schemes, Martin and Pawson (Citation2024, p. 1) flag the possibility that the types of demand-side schemes being promoted and established in Australia ‘potentially place governments even more among housing’s ‘insiders’, with a material interest in continually rising prices.’ Moreover, research in the UK suggests such schemes operate to transfer public wealth through householders to shareholders of the affiliated lending institutions (Manlangit et al., Citation2022).

Amidst this landscape, earlier research examined the possibilities for an expanded shared equity sector in Australia by proposing two models, termed ‘individual equity’ and ‘community equity’ that apportioned varying levels of equity between the partner organisation and the resident (Pinnegar et al., Citation2009). However, neither of the proposed models aligned with extant practice or referred to terminology used in the sector at large such as ‘shared equity’, ‘shared equity homeownership’, or any of the specific models comprising those umbrella terms. Pinnegar et al.’s (Citation2009) individual equity model was loosely based on the Western Australian government’s previous ‘First Start’ shared ownership product, in which the State held a proportion of the property’s value and provided a low-cost loan on the remainder, while the ‘community equity’ model was based on a hypothetical subsidy retention model proposed by Jacobus and Lubell (Citation2007). Pinnegar et al. (Citation2009) found limited market interest in either of such products, and a preference for individual equity products. Given the intensifying lack of permanently affordable ownership options in Australia, emerging policy commitments to models that may erode affordability, and a persistent lack of research and policy understanding of permanently affordable models, this project sought to determine market interest in models clearly based on extant practice and experience—namely, community land trusts.

Method – focus group design and approach

The research documented in this article was undertaken in Melbourne, Victoria, as research funding was provided largely by Victorian stakeholders with a direct interest in the establishment of permanently affordable home ownership via CLT models. Further, Melbourne is Australia’s second most expensive city and similarly to Sydney, is characterised by increasingly expensive ownership, insecure private renting, and insufficient public housing. As with Sydney, the city is serviced by a small but growing CHP sector, some of whom are driving the exploration of affordable ownership options to enable their tenants to move into appropriate models of ownership if they are able and interested to do so. Informed by conversations with the research project’s Steering Committee, the focus groups targeted households currently in employment, living in rental housing, and between 25 and 36 years of age, who were looking to buy a home but unable to do so due to housing prices.

Participants were recruited by an independent agency and offered a $100 shopping voucher for participating. When registering to attend, participants were asked anonymised questions about their current housing circumstances. This generated 35 participants and associated response sets. Focus groups were run in the evening of two consecutive weekdays at a venue that is readily accessible by public transport. Food and non-alcoholic beverages were provided. Four focus groups were held with nine participants in each; two registered participants did not attend. Focus groups were kept small to allow for whole-of-group discussion and were recorded and transcribed with signed permission from participants. Formal ethics clearance was provided by the administering University’s Human Research Ethics Committee and written consent was obtained before focus groups commenced, with all participants aware of their ability to withdraw at any time without consequence. All participants’ quotes are presented anonymously in this paper and all affiliated publications.

The focus groups started with an introduction to the research and the team, and participants were invited to introduce themselves and explain their interest in attending. Most expressed frustration at not being able to buy a home, the insecurity and costliness of renting, and their inability to modify their home or keep pets. Following the introductions, the research team explained the two models under examination—a 99-year, renewable and inheritable lease, and a co-ownership deed. Both models were presented as enabling the purchase of equity in an inner-city apartment that would be available on a cost-recovery basis of between 25-50 per cent below market, with a caveat that the estimate was hypothetical. A resale restriction in the lease or deed would stipulate that at termination of the agreement (sale or inheritance) the change in the resident’s share would be 25 per cent of the agreed change in the property’s overall value between purchase and termination, whether positive or negative. This formula was proposed as it is sits within the range of the most widely used CLT formulae in the USA, which return to the resident between 25 and 30 per cent of equity change (although note that no survey of resale formulae has been undertaken since 2002; Girga et al., Citation2002, Davis, Citation2009). The resident’s share was inheritable, such that inheritance would trigger a termination and valuation subject to the resale restriction, with heirs subsequently carrying the rights stipulated in templates of legal agreements via a new agreement (Crabtree et al., Citation2013).

It was clarified that the home would be owned in partnership with a non-profit entity, most likely a CHP, and that staircasing to full ownership would not be possible. It was also clarified that, on that basis, residents seeking full ownership would be encouraged to move into market ownership by selling their equity back to the partner organisation or to another pre-qualified buyer with oversight from the partner organisation, at the resale restricted price as calculated by the agreed formula. While international studies are small, that research suggests residents in shared equity home ownership are able to transition to market ownership following residency in a resale restricted home (e.g., Davis & Demetrowitz, Citation2003).

To enable ‘ownership-like’ features such as the resident paying an upfront premium (‘buying’ the lease) and being able to make repairs, CLT leases in Australia need to sit outside of current State- or Territory-based residential tenancies legislation, as such legislation does not allow these features and so carries risk of legal challenge. In Victoria at the time of the research, long term leases were exempt from the State’s Residential Tenancies Act 1997 if they prohibit termination for reasons other than a breach within the first five years of their term (see Crabtree et al., Citation2013). This means residents buying resale-restricted homes through a 99-year lease in Victoria could not sell during the first five years and this stipulation was explained to all focus groups. An overview was provided of the focus of CLTs in both the USA and the UK on resident participation in the governance of the organisation, with subsequent focus group discussion on participants’ levels of interest in being involved in organisational governance.

As the research team has extensive knowledge of and experience with CLT models in the USA and UK, and have examined the legal requirements to be addressed in the adoption of CLT principles in Australia, they were able to then answer any clarifying questions that participants had. The team were careful to represent the models conservatively and to be clear about international experiences of both success and failure. Consequently, claims regarding affordability were given with caveats as to this hinging on construction and other site-specific costs, while the tightness and non-negotiable nature of the resale restriction were made clear. The approach contrasts with that adopted by Pinnegar et al. (Citation2010, p. 28), which ‘deliberately built in a degree of ambiguity on a number of key points, or did not cover all the caveats and detail required to make a fully informed decision’ on the assumption that the resultant ambiguity would prompt questions from attendees. As much research shows, not all research participants feel equally confident to speak up, so a less-than-thorough explanation of the models could in itself negatively affect participants’ responses, as participants might not know what questions to ask in the face of incomplete descriptions or may feel uncomfortable asking questions. This may also skew participants’ preferences towards models that seem familiar; that is, those more in line with dominant market expectations and narratives of capital gains. It might also be that respondents were deterred by the researchers’ vagueness, if this created a sense that the models were so complicated or unusual that the researchers couldn’t or wouldn’t explain them properly. Australia’s housing system has been documented to exhibit strong path dependency (see Crabtree & Hes, Citation2009), so it is possible that the earlier research into resale-restricted models may have unknowingly reinforced that.

Therefore, the team in this research drew on their knowledge of the international sector and models, recognising the necessity for clarity in communication and the importance of awareness building in establishing markets for new products. Diverse housing models can struggle in the face of path dependency amongst planners, lenders, developers, builders, government, and community—including would-be residents. Complex systems such as housing sectors tend to not innovate unless pushed (Crabtree & Hes, Citation2009); consequently, new tenure or equity forms can struggle or be rejected simply because of their newness and unfamiliarity. On that basis, the shared equity sectors in the USA and UK, especially CLT sectors, have learned to place substantial focus on building familiarity for their models amongst all stakeholders to facilitate understanding and uptake. Hence the research team was careful to provide detailed explanations and check if the models were clear to participants.

Results – exploring market demand

How do we find out about this? Can we sign up?

I mean what’s not to like? Really, what’s not to like?

Recruitment questions – household characteristics

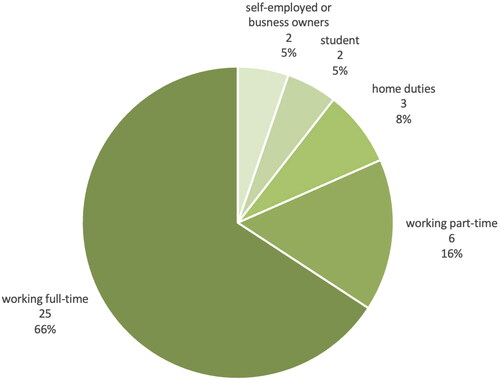

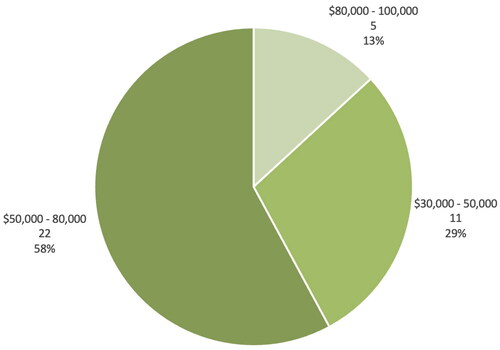

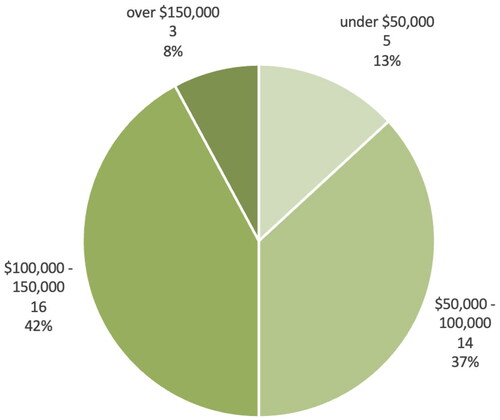

In their recruitment responses, most participants (25 of 38) stated they were in full time work, with six in part time work, three in home duties, two self-employed, and two studying (see ). The majority (22) were on individual incomes of between $50,000 and $80,000 (). This categorises the individuals as moderate- to high-income as the median individual income in the greater Melbourne area at the time of research was just under $35,000 per annum. Five individuals were on $80,000 - $100,000 per annum and 11 were on $30,000 - $50,000 per annum. Household incomes ranged from under $50,000 per annum (13%), through $50,000 - $100,000 per annum (37%), $100,000 - $150,000 per annum (42%), to over $150,000 (8%) (). Again, this places the majority of respondents in above-average income households, as the median household income across the greater Melbourne area was just over $80,000 per annum.

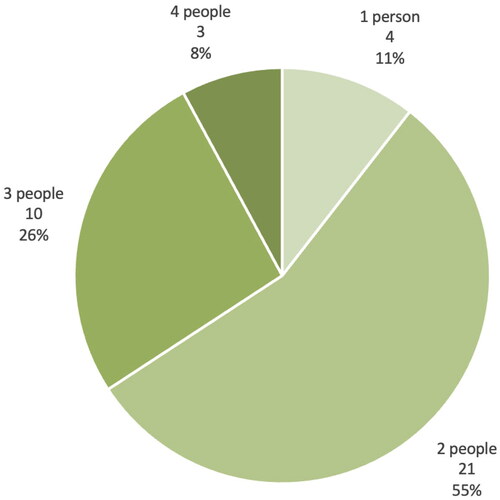

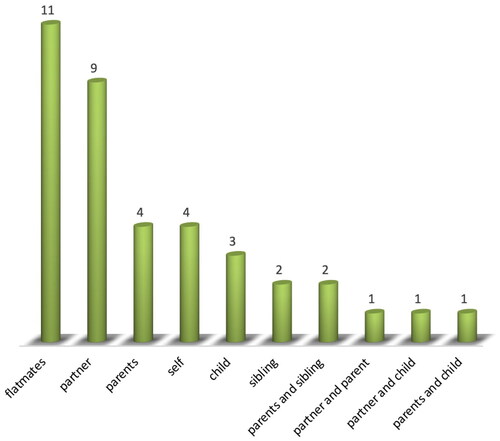

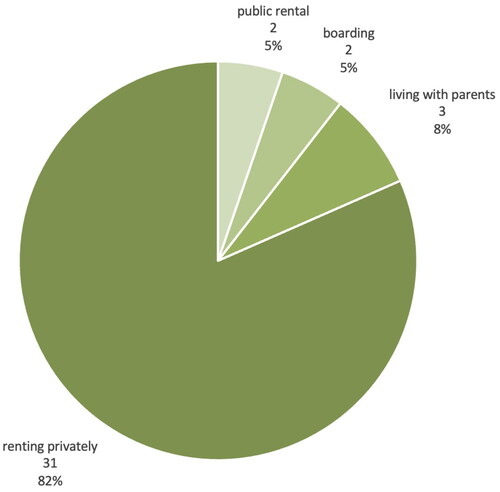

Most respondents lived in households of two people (21 responses) or three people (10 responses), with a minority in households of four people (three responses) or one person (four responses) (). As shown in , most respondents lived with flatmates or an intimate partner. The remaining minority of responses were highly diverse, with respondents indicating living with mixtures of partners, parents, siblings, and/or children. As shown in , three of those respondents lived with their parents, while the majority (31) lived in the private rental market. Two respondents lived in public rental housing and two were boarding.

Focus group discussions – housing experiences and reactions to CLT models

Introductory conversations about participants’ current housing situations highlighted recurrent issues across all focus groups with regards to the inadequacies of the private rental market. These centred on the instability and lack of autonomy experienced. Issues such as not being able to readily hang pictures and not being able to keep pets (or having to hide pets for housing inspections) were repeatedly raised by attendees. One attendee spoke of having to:

…lie on your application about having a dog. I've done it four times and every time they came to do the inspections, I'm just looking after my sister’s dog just for the day.

Focus group discussions then turned to attendees’ general thoughts and aspirations regarding home ownership. All stated they would like to buy a home but were unable to do so at the time. Some had a deposit saved but were worried their current savings were being outstripped by the growth in home prices, such that their deposit might not be enough to buy a home close to their current employment, community, education, and/or family connections. As one participant put it:

You could think – a couple of years ago – right, we’ll save 50 grand and buy a $500,000 house. Now if you haven’t saved that say three or four years ago, that house is now worth $800,000 to $900,000. Now you need $80,000 to $90,000 for a deposit… wages don’t go up – haven’t gone up anywhere near the price that the housing boom’s gone in the last six, seven, or eight years.

I feel pretty daunted by it. I feel like it’s the impossible dream that we’ve all been kind of sold.

I know, I’ve even looked at everything from tiny homes, to motor homes, to simple living alternatives. I’ve devoured the internet with stuff like that. I guess that’s a little alternative, I never thought I’d be that person. But in reality, just trying to make it work.

Unless you want to really compromise your lifestyle and move 40 or 50 kilometres out of town into a suburb you don’t want to live in just for the sake you can say you own a house, I don’t think you’d – I wouldn’t enjoy it anyway.

Discussion of the two proposed options for CLT home ownership options revealed no preference for leases or deeds amongst attendees. Both were seen as immediately appealing by most participants; 32 of the 35 participants would have signed up immediately if housing was available. The five-year restriction on reselling in a leasehold option did not trouble participants, who quickly suggested ways that the restriction might be worked around should an urgent relocation be required within the five-year period, such as by finding an income-qualified tenant in discussion with the hypothetical CLT. That is a workaround that has been developed in the USA for such instances and interestingly, was proposed by focus group attendees and not the research team.

The attraction that participants felt towards the models essentially was the flip-side of the problems identified with rental housing. Participants were greatly attracted to the security of tenure, ability to have pets, ability to make minor repairs, and the ability to access their equity upon termination—regardless of its limited nature—rather than continuing to pay ‘dead money’ as rent:

I think too like also having the ability to make decisions about how you live your life and what you do without having to get approval – whether it’s painting or decorating or owning pets.

…the long term security is good too because you know that’s it. You don’t have to worry about when my lease is up or inspections or could the owner sell or all these things are major things to worry about.

…you’re paying something into your own thing rather than paying the landlord, making him pay his mortgage, you’re paying your own mortgage.

So I’m looking into family day care as my life’s long term career objective. It’s really difficult to do in a rental space, to comply with the regulations. But beyond that, I want to create a workspace that really works and… You can’t adapt a rental space to do that sort of thing… the other thing is, is at the moment we’ve had – I’ve had five rental properties in the last seven years. Trying to get in and remodel and remodel again and again and again, is completely impossible.

However, none of the respondents flagged this as a significant enough issue to reduce their interest in the options and some suggested that the savings generated by housing stability might enable them to put money aside for heirs in other ways. This often led to discussion of financial literacy, as several participants flagged concern about their inability to raise a mortgage and asked whether initial and/or ongoing financial counselling would be part of the package. This aligns with the provision of financial literacy and/or counselling services by CLTs internationally (see Martin et al., Citation2020). Cowan et al. (Citation2015) flag the need for legal counselling in UK shared equity and demonstration of independent legal advice is generally a prerequisite for CLT ownership in the USA. One focus group participant saw a substantial role for partner organisations in providing clear advice and support to residents, both as they moved into the programme and then on to the next stage in their housing pathway:

If there was part of the package that then says… we’re going to help you get into this home and… we also have a plan for in such and such years or whatever, we’re going to help you get out of this and into the next step. We’re going to have an adviser to help you with the equity you make, even though it’s a smaller portion. To guide you, support you, lead you into that next step of the home outside of this.

…another frustration of where I live anyway, is a lot of apartments are vacant and they’re just used as kind of like, short term rentals here and there for tenants. It’s really frustrating because people are buying and pushing up the price and then not using them. So it lends itself to that bigger question of sense of community and where people fit in…

One thing that I really love about this from kind of like an emotional side is the fact that it’s in perpetuity, because I feel like everyone has parents or aunties or something that bought their house for 120 grand, and it’s now worth 800 grand, which is amazing for YOU… So to kind of have a house that will appreciate, but isn’t going to price out that next buyer or next generation thing where a house is less of a money making investment and it’s more about that home and place – like I think that’s a really unique part of what the program is really trying to do. [original emphasis]

With this current issue I think there’s a bit of a social issue to resolve. In a positive way to go into this, it’s sort of like – the way I think is you have enough and you don’t take more than what you need and everyone’s equal. Even though it’s a smaller amount or something, putting it in perspective with other people around the world, it’s a bit of a social conscience sort of thing as well. That’s what my feeling towards it is.

I mean it probably depends completely on individuals. Some people probably just want to get their house and then save. But then other people would like to have a say in how things are run or their experience might influence how they do things in the future but I think generally what seems to happen is when people own, they do tend to get more involved… So yes, for me, but it might be different for other people.

I think it depends what you’re going to be involved in. Like if you’re going to be involved in something that’s actually going to impact you and its big decisions that are going to be made that you can be a part of, then yeah.

I would be interested in being [on a Board] as well obviously as long as it didn’t impact my actual – like my job or anything…

I don’t know where it leaves you if you want to leave. I feel like you’re kind of – it sounds a little bit suffocating to me. Because it’s like you’re in and you’re in for this thing and you can’t buy them out and there’s like, you’ve just got to keep going.

Discussion – implications for housing systems in Australia and beyond

While small scale, the focus groups would suggest that in Australia, there is a latent market for diverse affordable home ownership options that restrict resale values to maintain affordability. Nearly all focus group participants were prepared to forego equity gains in return for the stability and autonomy that the model provided, aligning with data on the lived experiences of CLT residents in the USA (Martin et al., Citation2020). However, the study scope, method, and results highlight several issues for consideration.

Firstly, the diversity of household forms amongst participants suggests that diverse physical design options are also of interest. For example, the current living situation of some participants in multi-generational households may require further investigation, as it was unclear whether these configurations were due to affordability concerns, convenience, and/or carer obligations such as caring for a parent, sibling, and/or child. Innovative design and development models such as Melbourne’s Baugruppen-inspired Nightingale developments are over-subscribed, which shows there is a definite market for that model’s typology of compact units complemented by high-amenity shared spaces (Walters, Citation2019). Hence the combination of diverse tenure/equity and design/development programmes is worth exploration. The history of CLTs as community-led organisations shows they are appropriate to deliberative development models and designs that respond to community needs, which is partly driving their uptake internationally in addition to their affordability mechanisms. This means there may be potential and market justification to combine diversity in tenure and design.

Secondly, the various issues regarding access to finance and financial literacy highlight the need for tailored, stable mortgage products and models like a prescribed lead-in/deposit period. This would need to consider appropriate risk management scenarios and processes that treat the resident’s equity as more of a liquid asset that the partner can manage the transferral of in cases of default, than a fixed asset that requires the lender to access and sell the home. There is also a role for awareness raising amongst lenders, especially with regards to the lower foreclosure rates of the USA sector, including through the mortgage crisis of 2008-10 (Thaden, Citation2010, Citation2011). It also highlights the relevance of wrap-around or partnered financial counselling services; some USA CLTs require and/or provide financial counselling or training as part of the process of preparing would-be buyers and risk management would suggest this would be appropriate.

Thirdly, the focus groups’ discussion of a subsidy retention model alone did not enable comparative scrutiny of the nature of the model’s appeal, beyond participants’ stated attraction to being able to not move, to have pets, and not pay dead rent money. Hence questions remain as to whether the high level of interest, especially in contrast to earlier Australian research, was because:

Participants weren’t given the option of a model that enables higher equity return

The housing market has become significantly less affordable since the earlier research on market interest in shared equity

The model has inherent appeal and was explained to participants’ satisfaction; and/or,

Participants were self-selecting to attend a focus group on the topic on a weeknight, so had at least some interest in alternative approaches.

It seemed that the team’s familiarity and comfort with the model was reassuring and of interest to participants; this may also have made participants more comfortable with the models. This highlights the significant power that researchers wield in their representations and discussions of diverse housing models, suggesting a possibly more active—or at least sensitive—approach in research exploring diverse housing models. It highlights the role that research might play in enabling housing diversification through building data, awareness, terminology, and understanding as to the strengths and weaknesses of various models. It also resonates with earlier research on innovation in sustainable housing that highlighted the critical need for real estate agents and other intermediaries and affiliated professionals who understand and can appropriately describe diverse housing models and their pros and cons (Crabtree, Citation2006).

Lastly, DeFilippis et al. (Citation2018) discuss why holding on to the community angle in CLTs is important. Community-led models such as CLTs and co-operatives often highlight this social orientation and their commitment to the provision of affordable, quality homes and ongoing partnerships in their communities. For example, CLTs often refer to themselves as ‘developers who don’t go away’ or as undertaking ‘development without displacement’ (Davis Citation2009). In the community-led housing space more broadly, Sharam et al. (Citation2015) propose a ‘deliberative development’ model, while a recent mixed-use, mixed-income cooperative housing development in Zurich has the name ‘Mehr Als Wohnen’, translating as ‘more than living’. These semantic shifts signal a more profound, emerging evolution in housing expectations and aspirations to questions of amenity, longevity, stability, diversity, deliberation, accountability, and community, rather than capital gain maximisation. They also suggest why describing, researching, promoting, or selling a resale-restricted home as a purely financial model may have limited success. In all of the focus groups, individuals referred to aspirations that by and large were non-financial, so stakeholders looking to examine or broaden affordable housing options may need to acknowledge these aspirations by thinking and talking beyond ‘traditional’ housing economics or mere asset considerations of housing. To an extent, research and policy discussions of shared equity can be seen to reflect broader trends of housing financialisaton and the corresponding realignment of welfare policies. Hence there are elements of research and policy that conceptualise and promote shared equity options as models of transience on a presumed trajectory towards full ownership; for example, citing the need to continue to free up housing stock, Cheung and Wong (Citation2020, p. 738) identify this transience as a central feature, stating ‘such a shared equity arrangement should have a clear policy objective of helping low-income families progress on the housing ladder.’ However, the focus group data suggests that exit was not a priority for participants and when issues of wealth generation were considered, participants quickly identified channels for this other than their home. This suggests that financialised and asset-based interpretations of shared equity might not align with or capture the entirety of market aspirations, which foreground the desire to make and stay in a home. This echoes recent research showing that the majority of affordable housing co-operative residents want to live in their homes for the rest of their lives (Crabtree-Hayes et al., Citation2024). Asserting or assuming that shared equity and other affordable housing models must be a stepping stone in markets that are heating up, has the potential to put upwards pressures on the models, which underscores the need to increase the scale and diversity of resale-restricted models rather than design them to meet the demands of, and contribute to, overheated markets.

Conclusion

As a model within the broader spectrum of community-led housing (Crabtree-Hayes, Citation2023), CLTs are often defined as focusing on community benefit and permanently affordable housing. That is an intentionally broad definition that allows each CLT to determine what ‘community benefit’ and ‘affordable housing’ need to mean. As a result, CLTs undertake an immense diversity of housing and other activities, utilising a variety of legal forms and tools to do so. The need to locally define and uphold those objectives means that CLTs focus on organisational governance and on broader community awareness of both the CLT and its objectives and activities.

However, holding these objectives in balance in landscapes increasingly shaped by public policy concerns about ‘affordable housing’ and attendant criteria regarding eligibility and housing form, is discussed as becoming increasingly difficult and as coming at the expense of community control (see DeFilippis et al., Citation2018). The adoption and adaptation of CLT principles in Australia is in its early days and, similarly to the USA and UK sectors, occurring within a landscape currently dominated by private, speculative property forms and government outsourcing of welfare. This presents a series of issues regarding the possible form, objectives, and activities of CLTs and of other forms of permanently affordable and community-led housing such as co-operatives. These issues are relevant in Australia but also in other countries grappling with heavily speculative, financialised, and duopolistic housing regimes.

Firstly, there is an opportunity and need here to build or reform tenure models to address key ontological aspects of home regardless of form, with the flexibility to adopt and retain key objectives according to circumstance. As the focus groups showed no preference for leasehold or co-ownership models, and a primary concern with issues of stability and autonomy, it would seem there are grounds to use that core insight to both reform rental housing and develop resale-restricted ownership models. The former could include reform to rental tenures in line with countries that already have long-term, stable rental housing in which residents can make minor additions and repairs. The latter could involve either the establishment of new CLT organisations as underway in Australia and other jurisdictions, or refinement of existing community housing (CHP) products. The latter could include refinement of existing or proposed shared equity models in line with CLTs’ greater focus on and opportunity for community input. This could both remedy CHPs’ relative lack of community input into governance and address the perceived reluctance documented by Pinnegar et al. (Citation2009), which could be reflecting resident unease about partnering with a distant entity that has significant control over their rights and equity.

Secondly and relatedly, there is a clear need for research in this space to be cognisant of its role in shaping discourse and practice. All research creates rather than merely reflects the object of study, and so shapes possibility. This is amplified in nascent and unfamiliar fields in which the perception or expectation of researchers as experts is acutely sharpened. When combined with the intense path dependency of housing regimes, this foregrounds researchers’ roles in facilitating understanding before assessing interest. In this research, it was clear that both the researcher’s and the research assistant’s knowledge of CLTs was pivotal in assessing participants’ interest in the proposed models. It is also worth noting that the team’s long-term and ongoing experience as precarious renters was vital in building rapport and demonstrating understanding of focus group participants’ situations and experiences.

Thirdly and as crucial to enabling housing diversity, there is a clear need for knowledge building in affiliated sectors such as finance. This includes the need for long-term, fixed-rate mortgages, and for lender understanding and comfort with relational models of risk management in which defaults are managed as a relationship between the resident, the CLT, and the lender, rather than a transactional process of asset disposal. In heavily financialised housing regimes, this has implications for financial sectors that warrant further exploration.

The global need for, and interest in, diversified tenure forms appear to only be increasing. As a microcosm of broader systemic issues, Australian households are carrying higher rates of mortgage debt amidst increased living costs and pending interest rate increases. This positions Australia as possibly set to replicate the 2008-09 foreclosure crisis of the USA. In this context, Australia and other countries are seeing innovative models emerging that might not deliver affordability in perpetuity or enable community voice; for example, for-profit build-to-rent models and as discussed above, shared equity models that enable staircasing. If and as new public funding streams or support mechanisms are developed, the criteria for their award need to be clearly oriented to ongoing benefit, including perpetual affordability, accountability, design excellence, and opportunities for genuine resident involvement. The research in this paper suggests market appetite may be greater than believed and based on ontological rather than financial aspects of housing, offering ground for diversification into a greater range of stable and dignified housing options.

Note

1. Quotes from participants are presented anonymously.

Ethics statement

The focus group recruitment process and discussion schedule were granted ethics approval by Western Sydney University’s Human Research Ethics Committee. The approval number was H10705.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to acknowledge the beautiful lands of the Wurundjeri and Bunurong Peoples of the Kulin Nation, on which the research took place and acknowledge local Elders past and present for their enduring knowledge of caring for Country. Acknowledgement is also due to the focus group participants for their time and insights, the project’s funders and steering committee for support, insight, and guidance, and the project’s stellar research assistant for wrangling focus group logistics so utterly smoothly.

Disclosure statement

The author is a member of the Technical Advisory Committee of the International Centre for Community Land Trusts, an advisory member of the Blue Mountains Community Land Trust, a member of the Inner West Council’s Housing Affordability Advisory Committee, and the chair of the Australian Community Land Trust Network, which advocates for community land trusts in Australia. These are voluntary unpaid roles.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anglicare Australia. (2023). Rental Affordability Snapshot. National Report. Fourteenth Edition. https://www.anglicare.asn.au/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Rental-Affordability-Snapshot-National-Report.pdf

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2022). Housing: Census. Information on housing type and housing costs. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/housing/housing-census/latest-release#:∼:text=Description-,Housing%20tenure%2C%202021%20Census,30.6%20per%20cent%20are%20rented.

- Basile, P., & Ehlenz, M. M. (2020). Examining responses to informality in the global South: A framework for community land trusts and informal settlements. Habitat International, 96, 102108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2019.102108

- Cheung, K.S., & Wong, S.K. (2020). Entry and exit affordability of shared equity homeownership: An international comparison. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 13(5), 737–752. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHMA-06-2019-0059

- Clarke, A., & Heywood, A. (2012). Understanding the second-hand market for shared ownership properties. Cambridge Centre for Housing and Planning Research.

- Community Land Trust Network. (2023). What is a Community Land Trust (CLT)? https://www.communitylandtrusts.org.uk/about-clts/what-is-a-community-land-trust-clt/

- CoreLogic. (2022). How much has house price growth outstripped growth in wages? https://www.corelogic.com.au/news-research/news/archive/how-much-has-house-price-growth-outstripped-growth-in-wages

- Cowan, D., Wallace, A., & Carr, H. (2015). Exploring experiences of shared ownership housing: Reconciling owning and renting. The Leverhulme Trust. https://www.york.ac.uk/media/chp/documents/2015/sharedOwnershipCHPL.pdf

- Crabtree, L. (2006). Sustainability begins at home? An ecological exploration of sub/urban Australian community-focused housing initiatives. Geoforum, 37(4), 519–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2005.04.002

- Crabtree, L., & Hes, D. (2009). Sustainability uptake in housing in metropolitan Australia: An institutional problem, not a technological one. Housing Studies, 24(2), 203–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673030802704337

- Crabtree, L., Blunden, H., Phibbs, P., Sappideen, C., Mortimer, D., Shahib-Smith, A., & Chung, L. (2013). The Australian Community Land Trust Manual. University of Western Sydney. https://www.westernsydney.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0006/600567/Australian_CLT_Manual.pdf

- Crabtree, L., Moore, N., Phibbs, P., Blunden, H., & Sappideen, C. (2015). Community Land Trusts and Indigenous Communities: From Strategies to Outcomes. Final Report No. 239. Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute. https://www.ahuri.edu.au/sites/default/files/migration/documents/AHURI_Final_Report_No239_Community-Land-Trusts-and-Indigenous-communities-from-strategies-to-outcomes.pdf

- Crabtree, L., Sappideen, C., Lawler, S., Conroy, R., & McNeill, J. (2019). Enabling Community Land Trusts in Australia (p. 333). Arena Publications. https://arena.org.au/product/enabling-community-land-trusts-in-australia/

- Crabtree-Hayes, L. (2023). Establishing a glossary of community-led housing. International Journal of Housing Policy, 24(1), 157–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2022.2155339

- Crabtree-Hayes, L., Ayres, L., Perry, N., Veeroja, P., Power, E. R., Grimstad, S., Stone, W., Niass, J., & Guity, N. (2024). The value of housing co-operatives in Australia. Western Sydney University. https://doi.org/10.26183/0xpp-g320

- Davis, J. E. (2006). Shared equity homeownership: The changing landscape of resale-restricted, owner-occupied housing. National Housing Institute. https://groundedsolutions.org/sites/default/files/2018-10/13%202006-Shared-Equity-Homeownership.pdf

- Davis, J. E. (2009). Personal communication.

- Davis, J. E., & Demetrowitz, A. (2003). Permanently affordable homeownership: Does the community land trust deliver on its promises? Burlington Community Land Trust. https://www.getahome.org/wp-content/uploads/CHT-Permanently-Affordable-Housing.pdf

- DeFilippis, J., Stromberg, B., & Williams, O. R. (2018). W(h)ither the community in community land trusts? Journal of Urban Affairs, 40(6), 755–769. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2017.1361302

- Ehlenz, M. M., & Taylor, C. (2019). Shared equity homeownership in the United States: A literature review. Journal of Planning Literature, 34(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412218795142

- Girga, K., Rosenberg, M., Selkowe, V., Todd, J., & Walker, R. (2002). A survey of nationwide community land trust resale formulas and ground leases: A Report prepared for the madison area community land trust. URPL 844: Housing and Public Policy. University of Wisconsin. https://affordablehome.org/homeowner-resources/index_assets/resale-formulas-ground-leases-2002.pdf

- Jacobus, R., & Lubell, J. (2007). Preservation of Affordable Homeownership: A Continuum of Strategies. Center for Housing Policy. https://groundedsolutions.org/sites/default/files/2018-10/11%202007-Preservation-of-Affordable-Homeownership.pdf

- Manlangit, M., Karadimitriou, N., & de Magalhães, C. (2022). Everyone wins? UK housing provision, government shared equity loans, and the reallocation of risks and returns after the Global Financial Crisis. International Journal of Housing Policy, 24(1), 98–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2022.2123270

- Martin, C., & Pawson, H. (2024). Australian first home ownership assistance schemes: International comparison and assessment. Australian Economic Papers. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8454.12357

- Martin, D. G., Hadizadeh Esfahani, A., Williams, O. R., Kruger, R., Pierce, J., & DeFilippis, J. (2020). Meanings of limited equity homeownership in community land trusts. Housing Studies, 35(3), 395–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1603363

- Midheme, E., & Moulaert, F. (2013). Pushing back the frontiers of property: Community land trusts and low-income housing in urban Kenya. Land Use Policy, 35, 73–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2013.05.005

- Milcheva, S., Damianov, D., & Williams, P. (2023). The maturing shared ownership market: A data-led analysis. University College London. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10183951/

- Monk, S., & Whitehead, C. M. E. (2010). Making housing more affordable: The role of intermediate tenures. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- OwnHome. (n.d.) What is the Australian labor government’s help to buy shared equity scheme? https://ownhome.com/articles/what-is-the-australian-labor-governments-help-to-buy-shared-equity-scheme

- Pawson, H., Martin, C., Lawson, J., Whelan, S., & Aminpour, F. (2022). Assisting first home buyers: An international policy review. (Final Report no. 381). Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute. https://doi.org/10.18408/ahuri7127201

- Pinnegar, S., Milligan, V., Randolph, B., Quintal, D., Easthope, H., Williams, P., & Yates, J. (2010). How can shared equity schemes work to facilitate home ownership in Australia?. AHURI Research and Policy Bulletin No. 124. Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute. https://www.ahuri.edu.au/sites/default/files/migration/documents/AHURI_RAP_Issue_124_How-can-shared-equity-schemes-work-to-facilitate-home-ownership-in-Australia.pdf

- Pinnegar, S., Milligan, V., Randolph, B., Williams, P., & Yates, J. (2009). Innovative financing for home ownership: The potential for shared equity initiatives in Australia. AHURI Final Report 137. Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute. https://www.ahuri.edu.au/sites/default/files/migration/documents/AHURI_Final_Report_No137_Innovative-financing-for-homeownership-the-potential-for-shared-equity-initiatives-in-Australia.pdf

- Regional Development Australia. (2014). Doors to ownership: A business case and guidelines for a shared homeownership scheme with NSW community housing associations. Regional Development Australia. https://www.ncoss.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/140619-RDA-shared-home-ownership-report.pdf

- Ronald, R. (2012). The ideology of home ownership: Homeowner societies and the role of housing. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rose, S. (2018). The Case for a Community Land Trust for Hamilton, Waikato, New Zealand. Wel Energy Trust. https://www.lgnz.co.nz/assets/Uploads/831c08c78c/The-Case-for-a-CLT-for-affordable-housing-in-Hamilton-NZ-compressed.pdf

- Sharam, A., Bryant, L. E., & Alves, T. (2015). Identifying the financial barriers to deliberative, affordable apartment development in Australia. International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 8(4), 471–483. http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/10.1108/IJHMA-10-2014-0041 https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHMA-10-2014-0041

- Temkin, K. M., Theodos, B., & Price, D. (2013). Sharing equity with future generations: An evaluation of long-term affordable homeownership programs in the USA. Housing Studies, 28(4), 553–578. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2013.759541

- Thaden, E. (2010). Outperforming the market: Making sense of the low rates of delinquencies and foreclosures in community land trusts. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

- Thaden, E. (2011). Stable home ownership in a turbulent economy: Delinquencies and foreclosures remain low in community land trusts. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy Working Paper. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. https://www.lincolninst.edu/sites/default/files/pubfiles/1936_1257_thaden_final.pdf

- Thaden, E., & Lowe, J. S. (2014). Resident and community engagement in community land trusts. Lincoln institute of land policy working paper. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. https://www.lincolninst.edu/sites/default/files/pubfiles/1846_1154_lla10102_foreclosure_rates.pdf

- Troy, P. (2012). Accommodating Australians: Commonwealth government involvement in housing. The Federation Press.

- Walters, K. (2019). First ballot for Nightingale Village apartments oversubscribed by 435%. New ballot opens. https://www.dreamplanet.com.au/first-ballot-for-nightingale-village-apartments-oversubscribed-by-435-new-ballot-opens/