Abstract

Tenants all over the globe face the challenges of increasing rents and even forced evictions, particularly in the private urban rental sector. Affordable housing shortage and displacement have become severe societal problems for the lower- and middle-income segments. Certain legal institutions, including tenancy law, provide a decommodifying capacity for more tenure security and stability. This paper studies this capacity of tenancy law by comparatively examining the tenants’ and landlords’ rights in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland through the lens of decommodification. The focus is (1) on the rules of access to housing for new residents entering the housing market and (2) the rules of exit that govern the ability of the occupants to continue living in their apartments. Findings show that while tenants’ rights in Switzerland are weakly protected by law, tenants in Austria and Germany receive robust protection. Austrian and German tenants cannot be evicted at short notice, nor are landlords allowed to dismiss them unless they declare legitimate self-usage. Also, tenants remain protected from arbitrary rent increases in case of rental upgrading. Conclusions help practitioners to consider tenancy law as an influential way to counteract the market-driven dynamics in housing and to enhance the protective capacity within renting property.

Introduction

Affordable housingFootnote1 shortage and tenant evictions have become severe global societal problems for lower- and middle-income households (Marcuse, Citation2016; Rolnik, Citation2019; Slater, Citation2021). An increasing number of tenants are struggling to access housing markets and suffering from displacement due to rising rents and housing commodification (Aalbers, Citation2017; Christophers, Citation2022). They are pushed to the margins of cities and lose control over the places they call home because they can no longer afford to live in central locations and experience unstable or legally insecure housing conditions (Kadi et al., Citation2022; Lees & White, Citation2020; Slater, Citation2015). Increasing urban densification initiatives have further worsened the housing situation for many residents (Götze & Jehling, Citation2022; Wicki et al., Citation2022) as rents continue to rise due to urban redevelopment, intensive renewal, and new-build gentrification (Theodore, Citation2020).

Policymakers try to solve these current housing problems with various policy interventions (Debrunner & Hartmann, 2020). Some policy instruments shall, for instance, support tenants (e.g., through housing benefit payments), while others (e.g., public housing subsidies) may motivate housing providers to build and offer more affordable housing for lower- and middle-income segments. Sometimes, these policy instruments focus on landlords or tenants in urgent need of housing (Kadi et al., Citation2021).

This paper looks at the differential legal protection of tenancy law to tenants and landlords in three European countries with an integrated rental housing system: Austria, Germany, and Switzerland (Kemeny, Citation2001). More precisely, we ask: (1) How is the relationship between tenants and landlords in these three countries legally regulated by tenancy law? (2) What are the consequences of tenancy rules on tenants’ and landlords’ rights and protection in housing? By answering these research questions, our objective is to comparatively investigate the protectionist legal mechanisms of tenancy law regulating the often conflicting relationship between tenants (as housing seekers) and landlords (as housing providers). Our research focuses on affordability, tenure security, and tenant versus landlord legal disputes while leaving other challenging housing aspects for tenants aside, such as a sense of home, or quality of property conditions (Soaita et al., Citation2022). We systematically explore the differences in tenancy law among these three European states through a descriptive analysis of legal and policy documents.

The paper is structured as follows: in the next section, we introduce our concept of ‘de-commodification capacity’. Following a brief description of the methodological approach, which includes the reasoning for the case selection, we engage in a comparative discussion of the decommodification capacity of tenancy law in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland. Subsequently, attention shifts to our second question and its implications. This discussion is then followed by concluding remarks.

Tenure systems and the decommodifying capacity of tenancy law

The housing-related challenges outlined in the opening section of this article have prompted advocates to call for the decommodification of housing, such as by expanding public or social housing options. Hence, decommodification is mainly equated with state provision (Doling, Citation1999; Harloe, Citation1995). The current paper avoids delving into the debate on what decommodification entails concerning an entire housing system. Rather than that, we examine the capacity of tenancy law to decommodify and explore how it emancipates tenants and landlords from market pressures.

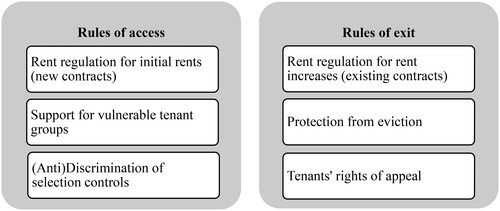

By ‘decommodifying capacity’, we mean the capacity of the tenancy law to support new residents to enter housing markets (rules of access) and to secure tenants to continue living in their apartment in case of income or rent level changes (rules of exit) (Korthals Altes, Citation2016).

In international comparisons of housing systems, the discussion of the legal differences among states (often OECD countries) is typically based on the welfare state typologies deriving from Gøsta Esping-Andersen’s (Citation1990) work on welfare states regimes (Baptista & O’Sullivan, Citation2008; Benjaminsen & Dyb, Citation2008; O’Sullivan & de Decker, Citation2007). Countries were then classified as dualist or unitary, sometimes called integrated, rental systems (Fitzpatrick & Stephens, Citation2014; Hoekstra, Citation2013; Hoekstra & Boelhouwer, Citation2014). In dualist rental systems, the renting sector is small and characterised by significant differences between a social rental sector, which is strongly subsidised and heavily regulated, and a dominant market rental sector, with few or no subsidies or regulation (Kemeny, Citation2001). Social housing is limited, strictly regulated, and reserved for vulnerable social groups. Countries with this system, such as the U.K., the U.S., Australia, and New Zealand, have high homeownership rates (Elsinga & Hoekstra, Citation2005). In contrast, the unitary system, as seen in Austria, Switzerland, and Germany, features a well-developed supply of rental apartments with only limited differences in the regulation and subsidies between the social rental sector and the market rental sector (Kemeny, Citation2001; Lennartz, Citation2011; Ronald, Citation2013). All systems are, however, under a process of continuous change (Stephens, Citation2020).

For Esping-Andersen (Citation2015), decommodification refers to the degree to which individuals or families can uphold a socially acceptable standard of living independent of market participation. The term, that is, refers to emancipation from market dependencies in consideration of rights. Esping-Andersen considered labour markets and examined the decommodification of workers through old-age pensions, sickness benefits, and unemployment payments. Other scholars included housing, land use, and other markets in their decommodification research (Kadi & Ronald, Citation2014; Kolocek, Citation2017). Holm (Citation2006), in addition, emphasised that the emancipation from housing market dynamics occurs in three different areas: money (through funding and subsidies), property (when building permits are equipped with specific duties for the developer), and rights. Examples of decommodification through rights include legal protections from fast-rising rents or eviction; both are typical tenancy law instruments.

Tenancy law: rules of access and exit

Tenancy law presents a private law instrument (enshrined in the Civil Code or the equivalent in common law countries) (Debrunner & Hartmann, Citation2021) aiming to balance the individual interests between tenants and landlords (Kettunen & Ruonavaara, Citation2021). The tenant-landlord relationship is inherently unequal, as the landlord has the discretionary power to withhold access to goods central to a person’s basic human needs and well-being (Zimmer, Citation2017). Therefore, tenancy law and its corresponding rules, e.g., rent regulation, protect the tenant from unfair treatment (Kettunen & Ruonavaara, Citation2021).

Our paper builds on Doling (Citation1999), who studied the level of decommodification in housing based on two kinds of rules or interventions: the rules of access and the rules of exit (). The former refers to nonfinancial criteria, providing new residents access to housing as a fundamental right (Kolocek, Citation2017). As Doling stated, ‘[w]here the nonfinancial criteria, providing access as a right of citizenship, are dominant, there will be a high level of decommodification’. The latter are the rules of security that govern the tenants’ ability to continue living in the apartment when, for whatever reason, their income or rent levels change (Doling, Citation1999).

Figure 1. The decommodifying capacity of tenancy law for tenants through strategically activating the rules of access and the rules of exit. Based on Doling, Citation1999; Haffner et al., Citation2018; Kettunen & Ruonavaara, Citation2021; and Lind, 2001.

Transferring the rules of access to tenancy rights sectors, we interrogate the nature and extent of these countries’ rent regulations for initial rents, support for vulnerable groups, and discrimination issues. Analysing rules of exit means that we investigate rent regulations for rent increases, eviction protections, and tenants’ rights of appeal.

This paper is based on the theoretical premise that certain legal institutions, including tenancy law, provide a decommodifying capacity (Korthals Altes, Citation2016). This capacity potentially reduces the vulnerability of tenant and landlord relationships to eviction, thereby offering tenants increased security and stability. The specific projections are:

This decommodifying capacity of tenancy law differs among legal tenure systems. Unitary rental systems—in which Austria, Germany, and Switzerland participate—are expected to show higher decommodifying capacities, as renting is the norm for a significant share of the population, and financial support for financially weak tenants has been enforced over many decades.

Tenancy law, even where organised within private law and not regulated via public housing policies or subsidies, matters to effectively provide affordable, socially inclusive housing that is not driven solely by market forces.

In unitary tenure systems where both the rules of access and exit are strong, tenants experience a high decommodifying capacity. Thus, they are highly protected from housing market dynamics.

Methodological approach

We obtain data through a qualitative and comparative case study. First, we explain the reasons for case selection and briefly introduce each country’s housing situation and tenure system. Then, we elaborate on the methods of analysis.

Case selection

Austria, Germany, and Switzerland were selected for various reasons related to their tenancy laws, tenure structure, and housing systems (). First, these countries face similar challenges in providing affordable urban housing due to rising rents (Debrunner et al., Citation2024). Finding a cheap rental apartment in cities such as Munich, Frankfurt, Zurich, and Vienna has become increasingly difficult for tenants. In all three countries, therefore, rent increases due to housing commodification have yielded undesirable outcomes such as tenants’ evictions (for discussion, see Kadi, Citation2015; Madden & Marcuse, Citation2016). Second, we selected three German-speaking countries because they show the lowest homeownership rates within Europe and are therefore regarded as ‘nations of tenants’ (Lawson, Citation2009) in liberal housing markets. In each country, private rental housing has become a widely accepted form of tenure for most people, and it is considered an essential component of housing policy (Gilbert, Citation2016; Haffner et al., Citation2018). Third, German-speaking countries are under-represented in international housing studies not least because of linguistic matters.

Table 1. Housing structures in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland (Gilbert, Citation2016; Kettunen & Ruonavaara, Citation2021; Schmid & Dinse, Citation2014).

However, despite the shared housing challenges encountered by all three countries, we identified noteworthy differences, underscoring the relevance of comparisons. For instance, exploring how tenants are protected from rent increases and can (or cannot) resist redevelopment or upgrading obtained by the landlords (Korthals Altes, Citation2016; Marsh et al., Citation2022; Slater, Citation2021).

Methods

We first collected each country’s policy documents of formally binding and non-binding nature, such as legal texts, norms, policy instruments, legislations, formal petitions, federal resolutions, federal statistics, protocols, policy reports, historical records, strategic policy documents as well as scientific literature. All data collected was chosen due to its incorporated and contemporary information about federal tenancy law and tenure regulations in the Austrian, German, and Swiss housing policy systems, as well as due to our prior knowledge and specialism of the topic. For instance, the specific country data comes from the TENLAWFootnote2 project’s state reports (Korthals Altes, Citation2016; Schmid & Dinse, Citation2014) and various other published sources (e.g., government documents, policy papers, and published research). This resulted in a database with up to 40 papers per country, with most of the documents originating from the last decade (2010–2023). The data collection process took place between November 2022 and March 2023.

Second, we conducted a descriptive and systematic qualitative data analysis and evaluated all collected documents. Based on the variables defined in the research questions (see theory section), we deductively analysed for each document the differences in tenancy law among the selected countries (research question 1) while reflecting at their potential impacts for tenants and landlords resulting out of these juridical distinctions (research question 2). Finally, we compiled the evaluated data, categorising the findings in alignment with the two research questions. This was done through repeating reviews by the authors and accompanying discussions that sharpened the comparative analytical aspects. The analysis involved comprehensively synthesising the outcomes to provide a cohesive and insightful presentation. We now proceed to presenting our findings in three main sections, focusing in turn on the decommodifying capacity of the countries’ tenancy laws.

The decommodifying capacity of tenancy law in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland

We start with exploring the tenure system disparities in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland. This helps us to detect how the involved parties manage the regulations concerning the rules of access and the rules of exit differently.

Tenure systems in Austria, Germany, and Switzerland

Austria is a federal republic in central Europe with gravely limited areas for potential development due to the alpine topography. While there is no actual shortage of housing stock in Austria, the need for more affordable dwellings in cities and economically thriving regions is an increasing issue, particularly in the metropolitan area of Vienna. In Austria, access to typically low-cost municipal housing and non-profit cooperative housing is limited, and the demand far from the supply. Many tenants are, therefore, compelled to lease properties on the ‘free’ market under contracts lasting three to five years, thereby being subjected to rising rents (Kadi, Citation2015; Kadi et al., Citation2022).

The complexity of the Austrian housing sector can be traced to its historical development (Doralt, Citation2023; Kadi et al., Citation2022). Austrian tenancy law originates from the first Civil Code in 1811 and is generally assigned to the federal state, while the execution lies with the nine states. In their executive role, the states adopted Housing Subsidy Laws and administered federal acts, including the Tenancy Act. Housing production, funding, and exploitation in Austria are thus controlled by legal acts and state actors on different levels. Housing project financing is provided through public housing policies such as the Housing Subsidy Program, general bank loans, specific housing banks, and historical building and loan associations. Rental law is, in the first place, regulated through the Tenancy Act; where this is not applicable, the Civil Code applies. The nearly unmanageable number of tenancy-related legislation started with the first Tenancy Act in 1922 following emergency ordinances during World War I. Additonal to the laws already in force, complex responsibilities and legal norms were added over time (Stabentheiner, Citation2009). This led to a situation where even experts describe the legal fragmentation in Austrian tenancy law as confusing and conflicting with the rule of law (Stabentheiner, Citation2012a). Moreover, the rent in Austria is composed of the actual rent per square metre, the operating costs, and VAT. Between 2012 and 2021, the rent per square metre increased by 33%, while inflation during this period accounted for ca. 18%, meaning that rents have increased significantly above inflation. In the capital provinces and Vienna, rents per square metre in new rental contracts are over 50% higher than in the 2010s.

Germany comprises 16 partly sovereign federal states (Länder in German, equivalent to the Swiss cantons). Because of the increasing demands and needs of the population, urban areas are experiencing an intensifying shortage of affordable housing in Germany (Schönig, Citation2020). Providing land for new housing has thus become an important policy goal to cope with rising housing demands and urban population growth (Hengstermann & Hartmann, Citation2021). Despite different programs to increase the homeownership rate in the past decades (Behring & Helbrecht, 2003), Germany is still a tenants’ country (53.5% tenancy share). Examining Germany’s housing policy over the past two decades, Stephens (Citation2020) asserts that the country’s rental market has undergone significant changes. Stephens (Citation2020) states that the traditional dynamic between cost and for-profit rental sectors is no longer central. Instead, the decrease in the social housing sector and the privatisation of municipal housing stocks are signals of recommodification. However, these changes have also increased the dependence on regulatory interventions in the for-profit sector.

Moreover, the German Constitution does not explicitly mention a right to housing. Still, housing rights are directly linked with the right to property (Article 14) because a rented apartment is considered property protected by Article 14 of the German Basic Law. The most relevant legal source for the relationship between tenants and landlords is the German Civil Code (BGB), which, as private law, regulates the law of persons, property, family, and inheritance. Sections 535–597 are most relevant, including the tenancy law section. These sections deal with general provisions on the rights and duties of landlords and tenants (regarding all goods with a use value, including residential space; section 535–548a, BGB) and provisions applicable to leases of residential space, including structural maintenance and modernisation measures (Article 549–556, BGB). The BGB dates back to 1900, but its first version did not contain any specific regulations on renting an apartment. A common saying was that the rent for an apartment was subject to the same regulations as the rent for a donkey (Wissenschaftliche Dienste des Bundestags, 2018). For a long time, tenants’ rights were spread across several special laws, and it is only since 1960 that the tenancy law has been structured and summarised in the BGB (Koch, Citation2005).

In Switzerland, population density is substantially higher than in Europe on average (Bourassa et al., Citation2010), and land for urban development has become scarce in recent years. Urban affordable housing shortages have started to affect particularly vulnerable resident groups (e.g., old aged and single-parent households) (Debrunner et al., Citation2022; Debrunner et al., Citation2024), as newly-modernized apartments are primarily affordable for higher-income households and non-profit housing suppliers have long waiting lists (Balmer & Gerber, Citation2018; SFOH, 2017).

The Swiss federal state plays a crucial role in this matter as it signals how to deal with housing and tenancy matters for cantons and municipalities. Switzerland is organised on three executive levels (the confederation, cantons, and municipalities) and characterised by cooperative federalism: legislation favouring social inclusion in housing is introduced by the federal state and implemented by cantons and municipalities (Linder, 1994). Vital public policies targeting ‘housing’ include the Swiss Federal Constitution (CSC, Articles 108–109) and its subsequent housing and social welfare policies (e.g., the 2003 Swiss Federal Housing Support Act). In private law, the Swiss Civil Code (1907), deriving from the Federal Obligations Code (1911; Articles 253–274), including the Swiss Tenancy Act, delivers the basis to regulate tenant-landlord relationships in detail. Swiss Tenancy Law was enacted in 1911 but was not formally recognised in the Federal Constitution until 1972 (Art. 109). Since its inception, various members of the legislative parliament, spanning left, liberal, and conservative wings, have endeavoured to amend tenancy law to enhance its adaptability and responsiveness to evolving market dynamics (Thomsen, Citation2008). Despite numerous revisions to acts such as the Swiss Federal Spatial Planning Act or the Swiss Energy Act since the 1970s, tenancy law itself has largely remained untouched, primarily due to challenges in garnering political majorities for a unified objective regarding specific revisions to the law (Thomsen, Citation2008). Generally, the Swiss political system is characterised by direct democratic rights, including initiatives and referendums on all administrative levels (Bourassa et al., Citation2010).

Rules of access: support for new residents to enter housing markets

Findings () show significant legal differences among Austria, Germany, and Switzerland in balancing tenant and landlord relationships through tenancy law. Significantly, even though all three countries belong to unitary rental systems, Swiss tenants are weakly protected under tenancy law in comparison to Austrian and German tenants.

Table 2. Differences between Austria, Germany, and Switzerland in the decommodifying capacity of tenancy law.

Rent regulation for initial rents (new contracts)

An effective way to facilitate access to the rental market is the regulation of admissable rents initially set in new contracts. Rents generally have to align with prevailing market prices in all three countries. Austria and Germany are, however, quite strict concerning rent regulation for new contracts. Austria, for instance, maintains a rigid rent control system that limits free market rents (new contracts) depending on the size, type, location, maintenance condition, and furniture of a dwelling in buildings constructed before 1945. This effective date is entirely arbitrary, lacks objectivity, and was introduced with the highly complex Tenancy Act in 1982 (Doralt, Citation2023). The large subsidised housing sector, mainly developed by non-profit housing associations and municipalities themselves, also has complex restrictions for initial rents. The Austrian private housing segment, which includes all rental properties not covered by special rules, can set rent levels freely based only on market prices. In Germany, there is a prohibition on increasing rent by more than 10% compared to the so-called reference rent customary in the locality (German: Vergleichsmiete) for tenants who newly rent an apartment (section 556d, paragraph 1, BGB). This regulation is referred to as the ‘rental price brake’ (Mietpreisbremse), which was implemented in 2015 by the coalition of the Christian Democratic Union (CDU) and the Social Democratic Party (SPD). The SPD played a leading role in advocating for this measure, while the Union successfully implemented a scheme to promote homeownership, mainly supporting families in building new homes. The purpose of the Mietpreisbremse is to limit rent increases for new leases. Each German federal state declares the areas where the instrument must be applied and implemented. It only applies in areas with housing markets under pressure, so the rule covers 315 out of 11,000 municipalities. Nevertheless, 28% of the population is affected by it (Michelsen, Citation2018). The rule does not apply to apartments built after October 2014. Unlike Austria and Germany, Swiss landlords are not required to align new rents with average rents in the surrounding neighbourhoods or with previous rent levels. In some cantons (e.g., Nidwalden, Zug, Zürich, Fribourg, Vaud, Neuchatel, and Geneva), however, there is an obligation to inform the new tenant of the rent previously paid using a form approved by the canton (German: Formularpflicht)—but only if the tenant requests for it.

Support for vulnerable resident groups

None of the tenancy laws in the three countries offer specific assistance for vulnerable tenants such as older people, migrants, disabled individuals, or single parents seeking access to private housing markets. However, at the municipal level, new residents, including those with documented status, can receive assistance through municipal agencies, local tenant or housing associations, or social welfare programs. Discrimination of immigrants or citizens with foreign-sounding names and limited language proficiency is a significant concern in all three states within the free people housing market. Therefore, people prone to discrimination seeking rental properties are advised to have a local accompany them during viewings to serve as a translator and mitigate communication issues or misunderstandings. Navigating the housing market often involves adhering to informal practices, prompting vulnerable resident groups to seek assistance from locals (Schmid & Dinse, Citation2014). Additionally, all three countries support low-income individuals and those with refugee status through social welfare assistance or demand-side subsidies available through housing policies.

Anti-discrimination of selection criteria

In Austria and Germany, the Federal Acts of Equal Treatment mandate that, in the provision of goods and services to the public, discrimination based on gender, religion or belief, disability, age, sexual orientation, ethnic background, or civil standard is forbidden. This rule applies to housing and must be considered by landlords in every phase of tenancy. Consequently, discrimination against vulnerable resident groups or by any socio-demographic characteristic is prohibited (Wolf, Citation2013). However, concerning migrants, barriers denying access to the rental housing markets are often due to the irresponsible practices of institutional housing providers (Hanhörster & Ramos Lobato, Citation2021).

Swiss landlords, by contrast, are free to choose their tenants. Even though discrimination against a prospective tenant on the grounds of race, ethnic origin, sex, or religion is a criminal offence under Swiss criminal law, landlords are still empowered to prohibit new tenants from moving into their apartments. Applicants can go to court to allege discrimination and infringement of their rights, but this does not give them the right to move into the dwelling they applied (Schmid & Dinse, Citation2014).

Rules of exit: support tenants to continue living in their apartment in case of income or rent level changes

Rent regulation for rent increases (existing contracts)

The housing rental systems in Austria and Germany have long employed rent regulation to control rent increases for existing contracts. In both states, the system to control rent increases is highly complex. In Austria, private rents must not exceed a standard rent set by the Ministry of Justice for every state if the rented property falls within the complete application of the Austrian Tenancy Act (buildings constructed before 1945) (Knoll & Scharmer, Citation2016). Rents in subsidised housing schemes have rules of rent calculation and indexation that align with consumer prices (Feichtinger & Schinnagl, Citation2017). For all other rents, the contracting parties are, in principle, free to agree on any clause of rent increase, but the rent after a rise due to things such as maintenance or upgrading work is not allowed to exceed the limits for ‘adequate rents’. Tenants in Austria are thus rigidly protected through strict rent limits, and rent increases due to structural restoration, upgrading, or renovation of the already-built housing stock are not permitted at tenants’ expense. The number of limited contracts in Austria is rising, but most tenants remain on unlimited contracts that only permit rent adjustment aligned to inflation (Kothbauer & Malloth, Citation2013).

Under German tenancy law, the landlord may demand approval of a rent increase up to the so-called ‘reference rent’ customary in the locality (section 558, paragraph 1; German ortsübliche Vergleichsmiete). However, there are restrictions, such as the capping limit (German: Kappungsgrenze), which prohibits the rent in existing contracts from being raised by more than 20% within three years (except for increases under sections 559–560, which deal with modernisation measures) (section 558, paragraph 3, BGB). In areas with highly pressured housing market situations, the capping limit is 15% (Deschermeier et al., Citation2016). Landlords who carry out modernisation measures may increase the annual rent by 8% of the costs spent on the dwelling. As a simple illustration, a landlord may demand €800 more yearly rent for a renovation, which cost €10,000.

In Swiss tenancy law, existing rents in established housing stocks must align with the current interest rate (German: Referenzzinssatz), corresponding to average mortgage rates, and, therefore, cannot be continuously increased. However, unlike Austria or Germany, the Swiss tenancy law system lacks nationwide reference rent regulations or capping limits, even in modernisation, renovation, or upgrades. This allows landlords to exploit legal loopholes to raise rents after renovations, resulting in ‘significant’ improvements for tenants (Debrunner et al., Citation2020). Landlords are not obligated to inform tenants in advance about prospective rent increases. Furthermore, in Swiss practice, renovations related to energy efficiency are considered maintenance costs, justifying rent hikes. Consequently, private landlords can transfer up to 50–70% of the total investment in energy-saving measures to tenants. Additionally, Swiss landlords can pass on energy costs (e.g., heating) and the CO2 levy to tenants (Debrunner et al., Citation2020).

Eviction protection

Even when rent increases are tightly regulated, tenants may still encounter eviction or dismissal from their residences. In Austria, for example, evictions due to urgent personal needs or severe damage caused by tenants to the rental property are generally permissible (Kothbauer & Malloth, Citation2013). Both terminations must be processed through the courts, which favour tenants. Nevertheless, tenant protection in Austria is generally robust, and tenants cannot be compelled to relocate involuntarily. In Germany, there are three possible reasons to justify evictions: (1) the tenant has violated its contractual duties, (2) the landlord needs the dwelling for themself or their family members (German: Eigenbedarf), or (3) the landlord would be prevented from making appropriate commercial use of the plot of land and would therefore suffer substantial disadvantages (Gerber & Nasemann, Citation2023).

Unlike neighbouring states, Swiss landlords are not obliged to give an eligible reason for rental contract termination. They can terminate an open-ended rental contract any time of the year without giving a reason as long as they assure a minimum termination deadline of three months. Temporary contracts (e.g., subletting) can even be terminated within days or weeks, according to the deadline set in the contract by the parties involved. Under Swiss tenancy law, tenants are not protected from eviction in the event of renovation, demolition of the premises, upgrading, or modernisation, even though they might have lived in their apartments for decades. It remains the exclusive legal right of Swiss landlords to decide whether the housing stock needs retrofitting or renovation. In recent years, however, legal changes have been announced (e.g., in the cantons of Geneva and Basel City), where tenants increasingly receive more substantial protection from eviction (City of Basel, Citation2020).

Tenants’ right of appeal

The three tenure systems differ regarding tenants’ right to appeal against landlord proceedings or decisions. In general, tenants of all states can appeal, e.g., for excessive initial rent or unlawful termination. The tenant can then go to court within a regular civil procedure. While tenants in Austria and Germany can invoke social clauses in case of unfair treatment, Swiss tenants can legally go to the cantonal tenancy court, too. For this, tenants must assert hardship that makes the eviction unreasonable, such as a long period of residence, old age, illness, or pregnancy. In Austria, moreover, in tenancy proceedings before tenancy arbitration boards, no legal fees are charged at all; costs for legal representation only can be incurred, and tenants and landlords can always apply for legal aid if they are unable to pay for their representation without endangering their survival (Stabentheiner, Citation2012a). At the district level, tenants can file requests for legal aid or even file a lawsuit against another party orally. In Switzerland, whether the rent is considered unfair depends on the rate of return that is considered reasonable and does not exceed the reference mortgage rate by up to 0.5%. This means that Swiss tenancy law stipulates that rent is considered fair as long as it remains within a certain threshold compared to the prevailing market conditions and investment parameters. In particular, rent is typically deemed fair if it aligns with the customary rental rates in the local area or district. Similarly, rent is considered reasonable for recently constructed or renovated properties if it remains within the range of gross pre-tax yield necessary to cover associated costs. This often leads to court rulings in favour of landlords, either because their proceedings cannot be proven unfair or because tenants did not have the financial, personnel resources, or professional funds to appeal (Debrunner, Citation2024).

In conclusion, this section’s findings show that Swiss tenants are more weakly protected under tenancy law than tenants in Austria and Germany regarding the rules of both access and exit. These tenancy law provisions influence tenants’ and landlords’ rights and protection in housing and, in essence, how housing stocks are effectively decommodified.

Consequences of tenancy law on tenants’ rights and protection in housing

In the previous section, we have systematically examined the decommodifying capacity of tenancy law. This section gives answers to the second research question and considers the consequences of the identified rules on tenants’ rights and protection in housing. Results for Austria show that tenants are exceptionally well protected concerning (1) their right to access the housing market and (2) their right to stay in the rented property. It is crucial, however, to differentiate whether the Austrian Tenancy Act can be fully applied (e.g., to eviction protection and wide-ranging rent protection), partly applied to eviction protection, not applied due to free rental agreements, or whether the Act falls under the protective rental schemes of non-profit and subsidised housing. In any case, staying in an apartment with an unlimited contract is the most secure, stable, and affordable option for Austrian tenants in the long run. This option gives landlords no option to increase the rent drastically or terminate the contract (Stabentheiner, Citation2012b). However, newcomers in the larger Austrian cities often struggle to find affordable apartments, as market price rents are high and contracts are usually limited. This leads to high mobility of this group, while long-term residents in existing housing stock enjoy the benefits of the protective rental system. Tenants’ protection in Austria leads to immobility of tenants with old and favourable contracts, a comparatively low homeownership rate, and de facto discrimination against tenants entering the market (Kadi et al., Citation2022).

For the German case, results show that tenants living in already-built housing stocks are protected well from rental contract termination, evictions, sudden rent increases, and the negative consequences of redevelopment, modernisation, or renovation. Considering the rent regulations, as in Austria, staying in an apartment is the most stable option for German tenants in the long run. This results in people staying in their apartments even when the number of household members shrinks. Older people, in particular, often live in apartments that are larger than they require and occupy housing units that would better serve the housing needs of larger households (Statistisches Bundesamt, Citation2023). Younger families searching for a new apartment are thus often forced to look for new housing at the edge of the cities (Münter et al., Citation2021) and to commute into the inner cities for work.

Results for Switzerland show that tenants—both those entering new contracts and those with existing contracts—lack legal protection. For instance, an open-ended rental agreement can be terminated at any time with a minimum termination deadline of three months and without legal restrictions for landlords. The effects of this legal situation on tenants in Switzerland are, among other consequences, new-build gentrification (Rérat & Lees, Citation2011) and an ever-growing number of temporary rental contracts. Short-term rentals give landlords even greater flexibility and planning security to evict tenants at short notice, sometimes within days or weeks (Debrunner & Gerber, Citation2021). Swiss tenants can legally go to the cantonal tenancy court if they feel mistreated or unfairly evicted because of a rent increase. However, most tenants do not use this option because they do not have the legal competencies or the financial means to do so (Debrunner, Citation2024).

Consequences of tenancy law on landlords’ practices in renting out their properties

Finally, results show that legal differences in tenancy law yield substantial differences in landlords’ decision-making processes concerning how, why, and to whom they rent their properties.

In Austria, landlords possess the privilege to lease their properties, but there is no obligation. Over the past decade, this has led to the construction of condominiums that are bought only for investment and not to be offered on the rental market (Kadi, Citation2015; Aalbers, Citation2017). Landlords sometimes shy away from renting apartments because of the protective tenancy law or prefer to establish tourist accommodation instead (Van-Hametner et al., Citation2019). The rental rates depend on the legal classification of the dwelling. The numerous rules to set the correct, adequate rate are a source of tenants’ legal disputes (Kothbauer & Malloth, Citation2013). Real estate agents are commissioned to conduct a lawful calculation and are typically consulted (Hofer & Klinger, Citation2022).

Considering the German tenancy system and its regulations on protection from eviction, the high level of security for tenants in Germany might make landlords careful when choosing new tenants, with negative consequences for people with lower incomes. Recent studies indicate that migrants have lower chances of finding new housing (Hanhörster & Ramos Lobato, Citation2021). Indirectly, therefore, the high protection from eviction might catalyse unlawful discrimination in the housing markets (Horr et al., Citation2018).

The Swiss tenancy law enables landlords to evict tenants at short notice (within three months) without providing a reason. Targeted exclusion of vulnerable and low-income groups increasingly occurs because landlords do not have a legal obligation to protect or include them and because they seek stable rent revenue. Moreover, Swiss landlords are not compelled to pay legal or financial compensation to their evicted residents. They even receive public supply-side subsidies (direct subventions via the Federal Energy Act) to energetically invest in their properties, e.g., to install new heating systems or windows to foster redevelopment and renovation. Because Swiss landlords are not allowed to raise the rents continuously within the already built housing stock, receiving subsidies for renovation represents a strong incentive, triggering total demolitions and reconstructions (for which they also receive subsidies) (Kaufmann et al., Citation2023). Finally, under the current Swiss Federal Tenancy Law (which has yet to be revised since the 1970s), many loopholes exist for landlords to defend their interests effectively.

Discussion & conclusion

While there is a broad body of literature on the differences among countries in housing and tenure systems (Kemeny, Citation2001; Scanlon et al., Citation2014; Stephens, Citation2020) or distinctions in tenancy law per se (Kettunen & Ruonavaara, Citation2021; Korthals Altes, Citation2016; Schmid & Dinse, Citation2014; Slater, Citation2021), research on comparative tenure legislation studies and its decommodifying capacity in housing is still scarce (Doling, Citation1999; Holm, Citation2006). However, recognising the influence of tenancy law is essential to understanding how tenants in general, and vulnerable resident groups in particular, can be protected effectively from housing market dynamics. Our goal was to show that there are significant legal differences in handling this matter, even in three Western European social welfare states with unitary housing systems.

In this paper, we have introduced two intervention ways of tenancy law (i.e., the rules of access and the rules of exit), which tenants and landlords can strategically activate to defend their (de)commodification interests effectively. We have focused on the nature of the tenant/landlord relationship in three unitary rental systems—Austria, Germany, and Switzerland—and each country’s decommodifying capacity of tenure legislation. Our results are as follows.

First, although Switzerland belongs to a unitary rental system and advanced capitalist economy with a high tenancy share (over 60%), its tenancy law is not structured primarily to benefit tenants and possesses limited ability to decommodify housing. Swiss tenancy law has remained unchanged, even as legislative adjustments pertinent to landlords and tenants have been introduced in Swiss Federal Energy or Spatial Planning Laws. This is also related to the fact that those who create the laws (the legislative parliament) often have conflicting and biased roles as landlords or as members of landlord’s lobbying organisations themselves, leading them to vote in ways that may not always align with the public interest (Debrunner & Hengstermann, Citation2023). In contrast, the Austrian and German tenancy legislations effectively strengthen tenants’ rights and protect them rigidly from eviction. Tenancy law appears highly protective for tenants here, and no political party would dare to change the established system substantially. Even though private property rights are valued highly in the Austrian Constitution, tenancy law severely impinges on these rights. Indeed, in many cases, the Austrian constitutional court has confirmed the legitimacy of the protective rental system at the cost of landlords (Prader, Citation2021).

Second, our results confirm that tenancy law has a decommodifying capacity. Through strategically activating the rules of access and the rules of exit, tenants secure protection from the profit-driven intentions of their landlords. In particular, the decommodifying impact of tenancy law appears most robust within the already-built urban housing stocks (rules of exit), where tenants in Austria and Germany are strongly protected from eviction. However, Swiss tenants appear powerless to make their voices and rights visible in renovation, modernisation, and upgrading situations. The private for-profit rental industry has not been forced to protect tenants from eviction or rent increases after redevelopment, nor have political efforts in favour of monument conservation policies (e.g., to preserve architectonic and social qualities within the built environment) received the support of the political majority.

Third, our results confirm that tenants benefit from higher levels of decommodification in tenure systems in which both the rules of access and the rules of exit are dominant. Rent controls work best when paired with tenant security measures (such as eviction controls) and when acting in tandem with the rules of access towards the use values of homes and land (Slater, Citation2021). However, it must be noted that even in the more egalitarian Austrian and German housing systems, tenants and landlords might look for loopholes to defend their interests. For instance, landlords try to improve their legal possibilities to pass on investments to tenants through operating costs, and tenants choose not to terminate existing contracts, even when they have not lived in the city for many years. This increasingly leads to ghost city areas because most apartments are rented out only through short-term lease contracts (or AirBnB arrangements) by people who only temporarily contribute to the local urban life. In some parts of Germany, for instance, the share of subtenants (individuals who are not the primary tenants) has risen to 25% (van Holm, Citation2020).

We conclude that tenancy law can play a significant role in eliminating the vulnerability of tenants to economic marginalisation and exclusion performed by landlords. One main conclusion is that housing production per se is not the only determinant of individual welfare. Instead, the specific arrangements—such as the rules of use, valuation, or allocation—constitute the essential basis for evaluating the degree of decommodification. These are adequately captured by the rules of access and exit of tenancy law introduced in this paper (Doling, Citation1999).

Moreover, we expect that in countries facing declining social housing and a growing private rental sector (e.g., Germany), the decommodifying capacity of tenancy law will become increasingly important (Stephens, Citation2020). Being a tenant remains economically viable in Austria and Germany, even within the private rental sector. Because of tenure legislation like rent controls, which prevent rents from skyrocketing suddenly and pricing out entire segments of current residents, Austrian and German tenants do not need to worry about imminent dismissal or eviction. Landlords, in turn, have no incentives to treat tenants as mere obstacles to procuring higher rents (Zimmer, Citation2017). From a landlord’s standpoint, the question arises as to why and when it is profitable to proceed with construction and rental activities. In Switzerland, the push to amend tenancy laws in favour of tenant rights is expected to intensify amidst ongoing tensions within rental markets, especially concerning densification initiatives (Kaufmann et al., Citation2023).

Tenancy law is thus not about affordability as such. Still, it is, more profoundly, about socio-economic exclusion and decision-making norms and rules that determine who can live where, how, and why (Lasswell, Citation1936). Perhaps most importantly, tenancy law (and its enshrined rules, such as eviction or selection controls, rights-of-appeal, etc.) can act as a buffer and safeguard against market forces that would otherwise expel tenants from their local communities. Stabilising or freezing rents can protect the status of lower- and middle-income segments as equal members in good standing of a particular district or city. Planners should, therefore, be more actively, strategically, and sensitively aware of this decommodifying capacity of tenancy law to create cities of inclusion, not for profit.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Housing affordability in this paper relates to the cost of housing relative to a household’s income and other legitimate expenses (Anacker, Citation2019; Mulliner et al., Citation2013). Depending on the respective income, housing costs levels, and each country’s federal tax or health insurance deduction system, this ratio differs between states. Normally, 20–30% of the household’s monthly net income is regarded as reasonable to spend for gross monthly housing costs (Balmer & Gerber, Citation2018).

2 For more information on the EU TENLAW project, see https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/290694.

References

- Aalbers, M. B. (2017). Symposium on variegated financialization. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 313376, 542–554. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijur.12522

- Anacker, K. B. (2019). Introduction: Housing affordability and affordable housing. International Journal of Housing Policy, 19(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2018.1560544

- Balmer, I., & Gerber, J. D. (2018). Why are housing cooperatives successful? Insights from Swiss affordable housing policy. Housing Studies, 33(3), 361–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2017.1344958

- Baptista, I., & O’Sullivan, E. (2008). The Role of the state in developing homeless strategies: Portugal and Ireland in comparative perspective. European Journal of Homelessness, 2, 25–44.

- Benjaminsen, L., & Dyb, E. (2008). The effectiveness of homeless policies-variations among the Scandinavian countries. European Journal of Homelessness, 2, 45–68.

- Bourassa, S., Hoesli, C., & Scognamiglio, D. (2010). Housing finance, prices, and tenure in Switzerland. Journal of Real Estate Literature, 18(2), 262–282.

- City of Basel. (2020). Kantonale Volksinitiative “Ja zum echten Wohnschutz“. Bericht über die rechtliche Zulässigkeit und zum weiteren Verfahren. Retrieved from https://grosserrat.bs.ch/dokumente/100392/000000392701.pdf?t=160772910520201212002505

- Christophers, B. (2022). Mind the rent gap: Blackstone, housing investment and the reordering of urban rent surfaces. Urban Studies, 59(4), 698–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980211026466

- Debrunner, G. (2024). The business of densification. Governing land for social sustainability in housing. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1008/978-3-031-49014-9

- Debrunner, G., & Hengstermann, A. (2023). Vier thesen zur effektiven umsetzung der innenentwicklung in der schweiz. The Planning Review, 59(1), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/02513625.2023.2229632

- Debrunner, G., & Gerber, J. D. (2021). The commodification of temporary housing. Cities, 108(7), 102998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102998

- Debrunner, G., & Hartmann, T. (2021). Strategic use of land policy instruments for affordable housing – Coping with social challenges under scarce land conditions in Swiss cities. Land Use Policy, 99(7), 104993. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2020.104993

- Debrunner, G., Hengstermann, A., & Gerber, J. D. (2020). The business of densification – Distribution of power, wealth, and inequality in Swiss policy making. Town Planning Review, 91(3), 259–281. https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.2020.15

- Debrunner, G., Jonkman, A., & Gerber, J. D. (2022). Planning for social sustainability: Mechanisms of social exclusion in densification through large-scale redevelopment projects in Swiss cities. Housing Studies, 39(1), 146–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2022.2033174

- Debrunner, G., Hofer, K., Wicki, M., Kauer, F., & Kaufmann, D. (2024). Housing precarity in six European and North American cities: Threatened by the loss of a safe, stable, and affordable home. Journal of the American Planning Association, 2024, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2023.2291148

- Deschermeier, P., Haas, H., Hude, M., & Voigtländer, M. (2016). A first analysis of the new German rent regulation. International Journal of Housing Policy, 16(3), 293–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2015.1135858

- Doling, J. (1999). De-commodification and welfare: Evaluating housing systems. Housing, Theory and Society, 16(4), 156–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036099950149884

- Doralt, W. (2023). Mieterschutz im Wohnraummietrecht – Historisch-Vergleichendes zur Entwicklung in Deutschland und Österreich. Graz Law, Working Paper No 19-2022. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4619334

- Elsinga, M., & Hoekstra, J. (2005). Homeownership and housing satisfaction. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 20(4), 401–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-005-9023-4

- Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Polity Press.

- Esping-Andersen, G. (2015). Welfare regimes and social stratification. Journal of European Social Policy, 25(1), 124–134. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928714556976

- Feichtinger, A., & Schinnagl, M. (2017). Die Vermögensbindung als Eckpfeiler der Wohnungsgemeinnützigkeit. Wohnrechtliche Blätter, 30(4), 99–105. https://doi.org/10.33196/wobl201704009901

- Fitzpatrick, S., & Stephens, M. (2014). Welfare regimes, social values and homelessness: Comparing responses to marginalised groups in six European countries. Housing Studies, 29(2), 215–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2014.848265

- Gerber, K., & Nasemann, A. (2023). Mietverhältnisse beenden. Kündigung, Schönheitsreparaturen, Instandhaltung. Haufe.

- Gilbert, A. (2016). Rental housing: The international experience. Habitat International, 54, 173–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2015.11.025

- Götze, V., & Jehling, M. (2022). Comparing types and patterns : A context-oriented approach to densification in Switzerland and the Netherlands. Urban Analytics and City Science, 2022, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/23998083221142198

- Haffner, M., Hegedüs, J., & Knorr-Siedow, T. (2018). The private rental sector in Western Europe. In J. Hegedüs, M. Lux, & V. Horvath (Eds.), Private rental housing in transition countries. An alternative to owner occupation ? Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hanhörster, H., & Ramos Lobato, I. (2021). Migrants’ access to the rental housing market in Germany: Housing providers and allocation policies. Urban Planning, 6(2), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v6i2.3802

- Harloe, M. (1995). The people’s home: Social rented housing in Europe and America. Blackwell.

- Hengstermann, A., & Hartmann, T. (2021). Land for housing: The reform of the German building code from an international perspective. Pnd, 01, 30–41. https://doi.org/10.18154/RWTH-2021-01677

- Hoekstra, J. (2013). A review of “Housing disadvantaged people? Insiders and outsiders in French social housing. International Journal of Housing Policy, 13(3), 327–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2013.820892

- Hoekstra, J., & Boelhouwer, P. (2014). Falling between two stools? Middle-income groups in the Dutch housing market. International Journal of Housing Policy, 14(3), 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2014.935105

- Hofer, V., & Klinger, M. (2022). Handbuch Immobilienverwaltung in der Praxis (3rd ed.). Linde.

- Holm, A. (2006). Urban renewal and the end of social housing: The roll out of neoliberalism in East Berlin’s Prenzlauer Berg. Social Justice, 33(3), 114–128.

- Horr, A., Hunkler, C. & Kroneberg, C. (2018). Ethnic Discrimination in the German Housing Market. A Field Experiment on the Underlying Mechanisms, Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 47(2), pp. 134–146. https://doi.org/10.1515/zfsoz-2018-1009

- Kadi, J. (2015). Recommodifying housing in formerly “red” Vienna? Housing, Theory and Society, 32(3), 247–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2015.1024885

- Kadi, J., Banabak, S., & Schneider, A. (2022). Widening gaps? Socio-spatial inequality in the “very” European city of Vienna since the financial crisis. Cities, 131, 103887. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2022.103887

- Kadi, J., Vollmer, L., & Stein, S. (2021). Post-neoliberal housing policy? Disentangling recent reforms in New York, Berlin and Vienna. European Urban and Regional Studies, 28(4), 353–374. https://doi.org/10.1177/09697764211003626

- Kadi, J., & Ronald, R. (2014). Market-based housing reforms and the “right to the city:” the variegated experiences of New York, Amsterdam and Tokyo. International Journal of Housing Policy, 14(3), 268–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616718.2014.928098

- Kaufmann, D., Lutz, E., Kauer, F., Wehr, M., & Wicki, M. (2023). Erkenntnisse zum aktuellen Wohnungsnotstand: Bautätigkeit, Verdrängung und Akzeptanz. Retrieved from https://www.research-collection.ethz.ch/bitstream/handle/20.500.11850/603229/ETH_SPUR_ErkentnissezumaktuellenWohnungsnotstand.pdf?sequence=5.

- Kemeny, J. (2001). Comparative housing and welfare: Theorising the relationship. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 16(1), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011526416064

- Kettunen, H., & Ruonavaara, H. (2021). Rent regulation in 21st century Europe. Comparative perspectives. Housing Studies, 36(9), 1446–1468. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2020.1769564

- Knoll, M., & Scharmer, M. (2016). IWD – Richtwert, Lagezuschlag und Befristungsabschlag am Prüfstand des Verfassungsrechts – Fällt das Richtwertsystem in Österreich? Wohnrechtliche Blätter, 29(4), 129–132. https://doi.org/10.33196/wobl201604012901

- Koch, U. (2005). Mietpreispolitik in Deutschland. Eine empirische studie unter berücksichtigung des qualifizierten mietspiegels. https://d-nb.info/982161085/34.

- Kolocek, M. (2017). The human right to housing in the face of land policy and social citizenship: A global discourse analysis. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kothbauer, C., & Malloth, T. (2013). Mietrecht (2nd ed.). LexisNexis-Verl. ARD Orac.

- Korthals Altes, W. K. (2016). Forced relocation and tenancy law in Europe. Cities, 52, 79–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2015.11.020

- Lasswell, H. D. (1936). Politics: Who gets what, when, how (1st ed.). Springer.

- Lawson, J. (2009). The transformation of social housing provision in Switzerland mediated by federalism, direct democracy and the urban/rural divide. European Journal of Housing Policy, 9(1), 45–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616710802693599

- Lees, L., & White, H. (2020). The social cleansing of London council estates: Everyday experiences of accumulative dispossession. Housing Studies, 35(10), 1701–1722. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2019.1680814

- Lennartz, C. (2011). Power structures and privatization across integrated rental markets: Exploring the cleavage between typologies of welfare regimes and housing systems. Housing, Theory and Society, 28(4), 342–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2011.562626

- Madden, D., & Marcuse, P. (2016). In defense of housing: The politics of crisis. Verso.

- Marcuse, P. (2016). Gentrification, social justice and personal ethics. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(6), 1263–1269. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12319

- Marsh, A., Gibb, K., & Soaita, A. M. (2022). Rent regulation: Unpacking the debates. International Journal of Housing Policy, 23(4), 734–757. https://doi.org/10.1080/19491247.2022.2089079

- Michelsen, C. (2018). Mietpreisbremse ist besser als ihr Ruf, aber nicht die Lösung des Wohnungsmarktproblems, In DIW Wochenbericht -- Wirtschaft. Politik. Wissenschaft. Berlin: p.109. Access online: https://www.diw.de/documents/publikationen/73/diw_01.c.578090.de/18-7.pdf (Accessed: July 2nd 2024).

- Mulliner, E., Smallbone, K., & Maliene, V. (2013). An assessment of sustainable housing affordability using a multiple criteria decision-making method. Omega, 41(2), 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2012.05.002

- Münter, A., Tippel, C., & Albrecht, J. (2021). Vom „Abrutschen am Bodenpreisgebirge“. In S. Henn, T. Zimmermann, & B. Braunschweig (Eds.), Stadtregionales Flächenmanagement. Springer Spektrum. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-63295-6_28-1

- O’Sullivan, E., & de Decker, P. (2007). Regulating the private rental housing market in Europe. European Journal of Homelessness, 1, 95–117.

- Prader, C. (2021). Mietrechtsgesetz und ABGB-Mietrecht: MRG ; mit Anmerkungen, Literaturangaben und einer Übersicht der Rechtsprechung. 6. MANZ'sche Verlags- und Universitätsbuchhandlung.

- Rérat, P., & Lees, L. (2011). Spatial capital, gentrification and mobility: Evidence from Swiss core cities. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 36(1), 126–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2010.00404.x

- Rolnik, R. (2019). Urban warfare: Housing under the empire of finance. Verso.

- Ronald, R. (2013). Housing and welfare in Western Europe: Transformations and challenges for the social rented sector. LHI Journal of Land, Housing, and Urban Affairs, 4(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.5804/LHIJ.2013.4.1.001

- Scanlon, K., Whitehead, C., & Arrigoitia, M. F. (2014). Introduction. In K. Scanlon, C. Whitehead, & M. F. Arrigoitia (Eds.), Social housing in Europe (pp. 1–20). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118412367

- Schmid, C. U., & Dinse, J. R. (2014). My rights as a tenant in Europe A compilation of the national tenant’s rights brochures from the TENLAW Project TENLAW: Tenancy law and housing policy in multi-level Europe. www.Tenlaw.uni-bremen.de.

- Schönig, B. (2020). Paradigm shifts in social housing after welfare-state transformation: Learning from the German experience. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 44(6), 1023–1040. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12914

- Slater, T. (2015). Planetary rent gaps. Antipode, 49(S1), 114–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12185

- Slater, T. (2021). From displacements to rent control and housing justice. Urban Geography, 42(5), 701–712. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2021.1958473

- Soaita, A., Simcock, T., & McKee, K. (2022). Housing challenges faced by low-income and other vulnerable privately renting households, Access online: https://pure.hud.ac.uk/en/publications/housing-challenges-faced-by-low-income-and-other-vulnerable-priva/publications/ (Accessed July 2nd 2024).

- Statistisches Bundesamt [Federal Statistical Office of Germany]. (2023). Press release No. N 035, June 14, 2023.

- Stabentheiner, J. (2009). Wohnrecht und ABGB – Integration oder optimierte Verschränkung? Wohnrechtliche Blätter, 22(2), 29–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00719-008-1132-2

- Stabentheiner, J. (2012a). Legistische Betrachtungen zum Mietrechtsgesetz. Wohnrechtliche Blätter, 25(7-8), 260–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00719-012-0072-z

- Stabentheiner, J. (2012b). Das ABGB und das Sondermietrecht – die Entwicklung der vergangenen 100 Jahre. Wohnrechtliche Blätter, 25(3), 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00719-012-0044-3

- Stephens, M. (2020). How housing systems are changing and why: A critique of Kemeny’s theory of housing regimes. Housing, Theory, and Society, 37(5), 521–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2020.1814404

- Theodore, N. (2020). Governing through austerity: (Il)logics of neoliberal urbanism after the global financial crisis. Journal of Urban Affairs, 42(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2019.1623683

- Thomsen, J.P. (2008). Die Revision des Schweizer Mietrechts. Wieso findet seit 1997 keiner der Vorschläge zur Revision des Mietrechts eine Mehrheit? In Competence Centre for Public Management. Bern. https://www.kpm.unibe.ch/weiterbildung/weiterbildung/projekt__und_mas_arbeiten/e234429/e234461/ThomsenJean-Pierre_ger.pdf.

- Van-Hametner, A., Smigiel, C., Kautzschmann, K., & Zeller, C. (2019). Die Wohnungsfrage abseits der Metropolen: Wohnen in Salzburg zwischen touristischer Nachfrage und Finanzanlagen. Geographica Helvetica, 74(2), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-74-235-2019

- Van Holm, E. (2020). Evaluating the impact of short-term rental regulations on Airbnb in New Orleans. Cities, 104, 102803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2020.102803

- Wicki, M., Hofer, K., & Kaufmann, D. (2022). Planning instruments enhance the acceptance of urban densification. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 119(38), e2201780119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2201780119

- Wissenschaftliche Dienste des Bundestag [Research Service of the German Bundestag]. (2018). Wohnraummietrecht – Historisches und Statistisches [Residential Renancy Law – History and Statistics]. WD 7 – 3000 – 121/18.

- Wolf, P. (2013). Das Gleichbehandlungsgesetz und das Mietrecht. Wohnrechtliche Blätter, 26(11), 281–284. https://doi.org/10.33196/wobl201311028101

- Zimmer, T. (2017). Gentrification as injustice. Public Affairs Quarterly, 31(1), 51–80. https://doi.org/10.2307/26897016