Abstract

This study focuses on production engineers’ skill formation to explain how the Hyundai Motor Company has succeeded remarkably since the 2000s as a litmus test of the post-catch-up question. Upgrades in Hyundai’s technological capabilities, and in the sophistication of its production system during this period, are described and analysed in relation to a change in corporate governance, monopolised domestic market structure followed by industrial restructuring in the late 1990s, hostile industrial relations and the working of the internal labour market for production engineers. This study concludes that production engineers’ skill-formation process is closely related to Hyundai’s production system, which is distinct from those of foreign automakers. Its excessive automation utilises flexible production technology, which saves on skills on the shop floor; this is the key factor in Hyundai’s considerable growth since the 2000s, given the systematisation and codification of project-based problem-solving capabilities as an engineering skill, and the implementation of a more systematic, performance-based personnel management strategy. The analysis suggests that Hyundai as a litmus test of the post-catch-up question appears to be a mixture of discontinuity and continuity, which is reminiscent of the concepts of ‘POST-catch-up’ versus ‘post-CATCH-UP’.

1. Introduction

The auto industry, as a key industry, has propelled the Korean economy’s prosperity in terms of production level, the number of firms and the rate of employment (Korea Automobile Manufacturers Association, Citation2013).Footnote1 Korean automobile producers have recently caught up with the United States and Japan, and have progressed from simply imitating foreign technologies to showcasing their own innovation (Kim, Citation1998; Lee and Jo, Citation2007). The Hyundai Motor Group, hereafter referred to as ‘Hyundai’, is the only indigenous automaker among these to have survived, thus far. Hence, it maintains its position as the national champion of this industry, given its considerable market share of approximately 70%. The remaining 30% share is ascribed to other foreign automakers, including General Motors (GM) Korea, Renault-Samsung, and SsangYong Motors (Korea Automotive Research Institute, Citation2013).

Most foreign commentators have been pessimistic about the development prospects of the Korean auto industry. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) International Motor Vehicle Programme group highlights the Toyota production system as the ‘lean production system’, namely a universal system that all car manufacturers should adopt. However, it concludes that Korean carmakers cannot obtain competitive advantages by introducing the Japanese production system, given Hyundai’s failure to penetrate the American market as a result of its product quality (Womack, Jones, and Roos, Citation1990, pp. 261–263). Despite massive industrial restructuring following the 1998 financial crisis, most foreign commentators considered the Korean auto industry’s future to be bleak, and three out of five Korean auto brands have been purchased by foreign firms. Hyundai, since the early 2000s, has remained the sole surviving indigenous carmaker. Ravenhill (Citation2003) predicted that automakers that have been purchased by foreign companies would focus on domestic sales rather than technological innovation, and given its incomplete technological independence, Hyundai overcoming its reputation as a low-price, low-quality car is difficult. However, Hyundai has exceeded these expectations, and has continually grown. Therefore, the company has remained among the top five international automakers in terms of car production since 2010 (Korea Automotive Research Institute, Citation2013). Additionally, Hyundai has steadily improved its quality, which approaches that of leading automotive producers.Footnote2 Hyundai, as per an initial quality study of new cars and a vehicle dependability study of the American market, has presently caught up with Japanese carmakers (J.D. Power, Citation2013).Footnote3

Although Hyundai utilises excessively automated, modern, flexible production technology, and subsequently saves on skills through the optimisation of automation and informatisation, partly due to adversarial industrial relations (Jo and Kim, Citation2013a), which may maximise the numerical rather than functional flexibility of workers on the shop floor (Kim, Jo, and Jeong, Citation2011), its human capital role remains unquestioned. If human capital should not be downplayed as a factor in Hyundai’s strong growth after the 2000s, then it can be posited that employees other than production workers may also drive this growth. We infer that engineers’ high level of accumulated technological skills compensates for workers’ limited skills on the shop floor, and facilitates Hyundai’s progress. Hyundai’s production system, in which engineers’ technological skills play a relatively critical role in its operation, can strongly differ from that of Toyota, in which workers’ skills and commitment on the shop floor are highly respected (Lee and Jo, Citation2007).

Hyundai, as a latecomer, has successfully managed to defy the existing trend in the first half of the 2010s by narrowing the gap in product quality and productivity in the automotive frontier. It is generally known that successful catch-up means that the follower becomes the frontier in terms of productivity and management performance. The catch-up question only focuses on the gap between the follower and frontiers in this manner, while the post-catch-up question progresses beyond this simple dichotomy, as the latter can provide a heuristic device to explore the diversity of unknown catch-up process, and to reflect on the existing successful catch-up. The post-catch-up question could be relevantly addressed in this regard by the following: Given this context, how has Hyundai survived since the 2000s despite the negative views of foreign commentators? Does Hyundai’s remarkable growth demonstrate a new and sophisticated way of catch-up to, or a break with, that of the automotive frontier? These are among the questions to be discussed in this paper.

This paper hypothesises that the skills of internal engineers drive Hyundai’s successful growth, and particularly after the 2000s. It explores engineers’ skill formation in this firm as a litmus test of the post-catch-up question, and aims to unpack the ‘hidden black box’ in this phenomenon. The following specific research questions are raised: First, how have engineers’ skills been formed during Hyundai’s historical development? Second, what concrete roles have engineers played in Hyundai’s remarkable growth, and especially since the 2000s? Finally, what inspires engineers to internally commit to a company, rather than changing jobs? The next section suggests research framework based upon a review of relevant literature. Section 3 describes Hyundai’s transition period in terms of a change in corporate governance, and the build-up of Hyundai’s production system since the 2000s. Sections 4, 5, and 6 examine production engineers’ skill formation and their roles relative to the build-up of Hyundai’s production system and the function of an internal labour market. Section 7 concludes, with implications for the post-catch-up question.

2. Relevant literature review and research framework

An engineer is defined as a ‘professional practitioner with an application capability of scientific knowledge to develop solutions for technical problems’ (Sako, Citation2013). Specifically, this definition refers to a white-collar worker who performs professional technical work. An engineer possesses technological skill and applies scientific knowledge (Black, Citation1997), unlike production workers, who are regarded as having craftsmanship skills acquired through experience. However, skills not only correspond to a narrow range of capacity necessary for a specific task, but can also consist of various professional aspects, and subsequent employability. McQuaid and Lindsay (Citation2005, pp. 209–210) illustrate the different components of skills, namely job-specific skills, such as formal qualifications; key skills, including reasoning, problem-solving, and adaptability; basic skills, such as document literacy, writing, numeracy and verbal presentation; and social skills, including reliability, responsibility, self-discipline, and work attitude. This paper will broadly employ the concept of skills to explain those of engineers.

Many research studies have been conducted regarding production workers; however, engineering literature from a social science perspective is scarce.Footnote4 Amsden (Citation1989, pp. 188–198) pioneered the study on this topic by reporting how Hyundai engineers adopted and learned advanced technologies by perceiving Korea as a ‘small Japan’. Hyundai at the time had implemented major components of the Japanese production system, such as quality checking, just-in-time processing and job rotation. Despite the author’s academic contribution, with an emphasis on the roles of engineers, it would be difficult for this perspective to explain Hyundai’s continuous progress since the late 1990s, given that the company has established an indigenous production system that differs from that of the Japanese. Hyundai’s engineers have spearheaded the construction of this system, which complements production workers’ low skills.

Kim (Citation1998) examines Hyundai’s product development process ‘from imitation to innovation’ by adopting and learning overseas technology. He documented the progress of auto industries in developing countries, such as Korea, regarding technological innovation, in which Korea has dynamically caught up with that of other countries. However, this work attributed this enhancement solely to highly educated, diligent, and industrious human capital, and disregarded the conflicts between social and economic agents, such as the labour force and management. The author, in addition to this emphasis on human capital, did not analyse engineers in detail. Nevertheless, his study provides a theoretical basis for explaining Hyundai’s engineer-based strong growth as a litmus test of the post-catch-up question by emphasising the development of Hyundai’s own technological capabilities.

Moreover, Jeong (Citation1999) claimed that large Korean firms are passive regarding on-the-job training (OJT) for engineers because such firms produce inexpensive products that are not technologically complicated, and the core parts and components of these products are sourced overseas. Additionally, universities and government agencies have failed to meet the appropriate, customised industry needs for education and training (Jeong, Citation1995, Citation1999). However, the author’s perspective is limited in explaining engineers’ leadership role in Hyundai’s progress, given that the company has not only successfully developed its own model by assimilating imported technologies, but has also continuously improved its own technology. Moreover, his view cannot clarify the high values of engineers’ skill formation in Hyundai, which is a strong competitor of Western automakers, because his results imply that large Korean firms are inferior to their Western counterparts. This paper believes, in contrast, that engineers’ skill formation has predominantly contributed to Hyundai’s considerable growth.

Exceptionally, Smith and Meiksins (Citation1995) argue that engineers play a contradictory and independent role in the interactions between management and workers on the shop floor. They posit that engineers act as administrators on behalf of management, although they are considered workers, as wage earners. The authors also maintain that although engineers have led various production systems’ innovation since the introduction of Taylorism, their roles have been relatively neglected in social science research; the authors then developed a typology based on specific national labour–management relations that describes engineers’ different roles.

Generally, engineers are largely divided into two categories: those specialised in product development, that is, research and development (R&D); and those in the development of process technology. This study focuses on the latter because Hyundai considers production technology to be more important than the product itself. The rationale behind this decision is that production technology can affect productivity and product quality through the efficient mass production of high-quality products, and is regarded as a core element of competition in the auto industry. A skill-saving production system is needed in Hyundai’s specific case, to determine the role of production engineers in effective overall performance, as well as their roles in the management of many production workers. Hyundai’s production engineers are primarily responsible for tasks including production and process technologies, maintenance, and quality control management.

Inspired by the insights of Smith and Meiksins (Citation1995), this paper adopts the research methods described as follows to analyse Hyundai production engineers’ skill formation. First, the characteristics of this skill formation are explored, in line with the historical trajectory of the company’s growth. Problem-solving capability and the efficient, flexible meeting of project targets are at the core of the company’s culture, or ‘Hyundaism’. In this regard, this paper investigates the accumulation of production engineers’ skills as organisational agents of these capabilities over time. Moreover, as Thelen (Citation2004) and Streeck (Citation2012) discussed skill formation from an institutionalist perspective, this paper reports the theoretical implications of this skill formation as it pertains to Hyundai.

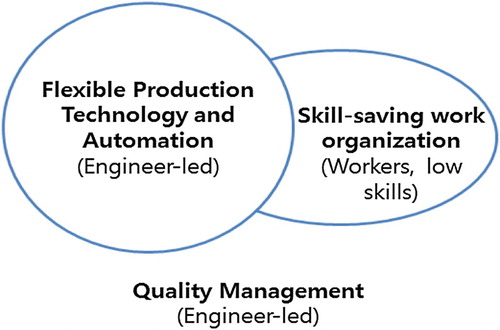

Second, this paper illustrates how production engineers’ skills complement the limited skill level of production workers in Hyundai’s production system. This system is borne of the premise that production workers cannot address product quality issues in a given process fully and responsibly (Jo and Kim, Citation2013b). A production system involves production technology and work organisation, and this production is efficient when individual components on the shop floor are integrated through quality (Fujimoto, Citation2003, pp. 69–70). The organisational capability refers to engineers’ ability to manage individual elements on the shop floor in an integrated way. We hypothesise, as illustrated in , that production technology engineers are leaders in Hyundai’s production system. Furthermore, they complement the limited skills of the organisation’s production workers, and facilitate quality management. The characteristics of this production system, to this end, are illustrated using several examples: A pilot centre, in which process-related issues can be resolved prior to the launch of new, mass-produced cars; a fool proof system that prevents workers from committing mistakes in the production process; and a total quality management scheme, which was introduced by the new CEO as a business strategy for the systematic improvement of product quality.

Finally, this paper hypothesises that the development of an internal labour market generates an institutional incentive for engineers to commit to the enhancement of Hyundai’s production system. This incentive deters engineers from changing jobs, while the introduction of meritocratic personnel management has encouraged engineers to perform their jobs competitively since the late 1990s. summarises the discussed research methods, thus far.

This topic is studied both qualitatively and quantitatively. From 4 October to 6 December 2013, unstructured, in-depth interviews were conducted with four executives who manage engineers at the Ulsan plant, a Hyundai parent plant; 10 middle managers, as well as one union representative, were also interviewed. Concerning major disputes, an attempt was made to avoid errors and distortions by conducting face-to-face interviews several times. provides details of the interviewees.Footnote5 Moreover, survey questionnaires were distributed to the 300 production engineers at this plant from 25 November to 6 December 2013, with the help of the personnel management department. These questionnaires inquired regarding engineers’ education and training; the management of human resources, bosses, and colleagueship; and job performance and identity. One hundred and eighty-nine questionnaires were returned. The population and sample, as exhibited in , are similar regarding the ratio of job title, as the stratified sampling process referred to the ratio of engineer population.

Table 1: Hyundai engineers interviewed in this study.

Table 2: Distribution of samples according to job title for a survey questionnaire.

3. A transition period: a change in corporate governance and the build-up of Hyundai’s production system.

The momentum for Hyundai’s strong growth after the 2000s, as a litmus test of the post-catch-up question, was initiated by the shift in Hyundai’s corporate governance during the economic crisis in the late 1990s. This section describes this change, which is attributed to the auto industry’s corporate restructuring, and the Hyundai production system’s unique characteristics, formed by the development of production modularisation. The transformation of Hyundai’s engineering group is then discussed.

3.1. Restructuring in the auto industry and change in Hyundai’s corporate governance

The 1998 financial crisis resulted in the following events: the bankruptcies of Daewoo, which was subsequently acquired by GM, and Kia Motors; the fire sale of Samsung Motors’ assets, and Hyundai’s severe layoffs and restructuring. The Korean auto industry underwent radical industrial restructuring as a result, during which the Hyundai production system evolved through significant changes in the company. Hence, the late 1990s marked a significant turning point for Hyundai as a global automaker.

The governance of Hyundai shifted significantly in this period. This change in management was highlighted by the replacement of the existing CEO in 1998. Additionally, Hyundai broke away from the Hyundai Group and was renamed as the ‘Hyundai Motor Group’ in light of high tension among insiders associated with the Hyundai Group’s corporate secession. This altered corporate governance drove the development of an ambitious plan to establish Hyundai as a Global Top Five company by 2010. Hyundai, to this end, has adopted an aggressive management strategy that advocates quality management and the dynamic expansion of overseas production.

Hyundai has transformed the domestic market’s formerly oligopolistic structure, consisting of Hyundai, Kia, and Daewoo, into a monopolistic one by acquiring the bankrupt Kia Motors, and commanding approximately 65–75% share. Thus, the company confidently implemented an aggressive management strategy in the 2000s. This monopoly prevented engineers from changing jobs, and was a catalyst for them to actively commit to Hyundai.

3.2. Modularisation of production and skill-saving production system

After acquiring the bankrupt Kia Motors, Hyundai’s top management aggressively pursued platform integration and production modularisation to respond to the external environment with agility, which resulted in the diversity of product models and economies of scale. Hyundai actively pursued production modularisation through a task force team as a part of this management strategy in the early 2000s (Jo and Kim, Citation2013a). This strategy resulted in the introduction of Hyundai MOBIS as a new auto parts subsidiary. Hyundai MOBIS originated from a former subsidiary of the auto parts division of Hyundai Precision Industry Co., Ltd., and was renamed in 2000. This subsidiary acts as the core parts supplier for the production of Hyundai automotive modules (Kim et al., Citation2011), supplying core chassis, cockpit, and front-end modules, and has improved continuously. Furthermore, Hyundai not only pursued platform sharing among the same car model segments, but it also expanded module production by enhancing their applicability during new vehicle models’ development.

Production modularisation merges the final stages of vehicles’ assembly processes with those of module suppliers to integrate multiple parts into only a few modular components, transferring considerable parts of carmakers’ final assembly processes to module suppliers. The advancement of modularisation streamlines vehicles’ final assembly processes for carmakers through the assembly of a few modules. Hyundai has not only extended its modularisation in this respect, but has also maintained automation to streamline its assembly processes. This simplified production process reduces the company’s dependency on workers’ skills, and this modularisation enables Hyundai to establish its own production system, which limits the dependency on skilled workers while enhancing automation and informatisation. Engineers’ skills have played a significant role in supplementing workers’ limited skill.

Why has Hyundai intensified the development of the skill-saving production system since the 2000s? First, prior to the 2000s, Hyundai had undertaken the management strategy of exploiting technological skills, rather than those of workers on the shop floor, by which it could accumulate engineers’ skills. Major industrial companies’ growth strategies, including that of Hyundai, led Korean industrialisation during the 1970–1990s to catch up with the industry’s frontier, and can be epitomised as an ‘assembly’ strategy (Levy and Kuo, Citation1991; Hattori, Citation1997). Given this strategy, the procurement of the latest process technologies, rather than the skills of shop floor workers, is essential to enhance productivity and to sustain competition based on prices. Thus, Hyundai as a large chaebol is heavily invested in the latest production facilities and process technologies, and engineers quickly assimilated imported technologies and applied them to Hyundai’s own product development. On the other hand, shop floor workers’ skill formation was indeed neglected. This technology-centred assembly strategy involved engineers’ relatively advanced skill, while subsequently limiting the skills of workers on the shop floor. The strategy, which was employed to catch up with the industry frontier before the 2000s, acts a basis for Hyundai’s path-dependent development in the 2000s. This has resulted in increased progress of the skill-saving production system through production modularisation.

Second, repeated failures of shop floor workers’ skill formation in the 1990s allowed Hyundai to advance their skill-saving production system. The company attempted in the early 1990s to systematically upgrade shop floor workers’ skills through the introduction of the vocational qualification system, based on the premises of individual ability development and meritocratic personnel management. However, this programme was not adopted due to backlash from labour union members, because the system could have resulted in a reduction of the labour union’s collective forces (Jo, Citation2005, pp. 110–112). Hyundai also attempted to upgrade shop floor workers’ skills through the 1997 Training Road Map programme, but this also failed due to mass layoffs in 1998, and the subsequent replacement of the existing CEO (Lee and Jo, Citation2007). These experiences acted as a catalyst for the progress of the Hyundai production system, which excluded shop floor workers’ skills as much as possible.

Finally, a series of industrial relations events during the 1998 financial crisis strongly affected the skill-saving production system’s progress in the 2000s. Hyundai’s engineer-led, highly flexible production system combines the latest process technology and skill-saving work organisation strategies with numerical flexibility. Hyundai has provided a technological condition for excessive numerical flexibility, by building a work organisation in which even shop floor workers with few skills can perform their tasks easily. As hostile industrial relations, and particularly due to mass layoffs in 1998, made it difficult for shop floor workers to participate in actively upgrading their skills, Hyundai has developed its production system to capitalise on engineers’ technological and human potential as much as possible (Jo and Kim, Citation2013b).

3.3. Growth and change in the engineer group

With the shift in Hyundai’s governance structure, the number of engineers has increased over time. illustrates a changing pattern in the total number of Hyundai’s domestic employees, based on job categories after the late 1990s. The total number of domestic employees in this period increased from 47,174 to 58,271, proportionate to the increase in the total number of produced vehicles, from 1.28 million units to 1.91 million units. Although much automation and outsourcing occurred during this period, per capita labour productivity also increased continuously. The total number of R&D staff generally tripled in terms of job composition, but that of white-collar office workFootnote6 and production increased only slightly.Footnote7

Table 3: A change in the trend of employees by job category and production volume in Hyundai.

Engineering groups in Hyundai have not developed equally, and this change in the composition of production engineers deserves attention. Although the total number of white-collar office workers has increased slightly, the total number of production technology engineers began increasing in the late 2000s. Moreover, the total number of production technology engineers increased only slightly by 2007–2008, compared with the larger increase in 1998. However, production technology engineers are currently being recruited to support overseas plants that were established only four to five years ago (interviews, 2013). displays the proportion of engineers regarding the total white-collar office employees employed in Hyundai’s Ulsan plant, in terms of job category and job title. White-collar office employees drive much of the company’s strong growth; production engineers alone account for 65.3% of this force.Footnote8

Table 4: Composition of white-collar office job at the Ulsan plant as of 2013 (person, %).

4. Engineers’ skill formation in Hyundai

This section examines the skill formation of Hyundai’s engineers because this has facilitated the company’s strong growth and production system improvement since the 2000s. This study explores, to this end, how the capability to solve project problems, as a skill of Hyundai engineers, was embodied for the catch-up prior to the 2000s. The evolution of a group of such engineers after the 2000s is then followed as a touchstone for the post-catch-up question.

4.1. The embodiment of project-based problem-solving capabilities for the catch-up

The ‘challenge’ concept is encapsulated in the managerial ethos of Hyundai’s founder, which is labelled as the ‘Hyundai Spirit’ (Kirk, Citation1994). This represents, in reality, the propensity to push ahead with problem-solving through the intensive mobilisation of resources within the chaebol group, despite a reckless plan. The acquisition of problem-solving capabilities through group-wide assistance effectively illustrates an attribute of the Korean chaebol, which emphasises swift and unilateral decision-making and the mobilisation of management resources through the centralisation of power in a group chairman. Hence, technological skills can be experienced and quickly learnt through an insensitive approach to problem-solving in extreme projects (Kim et al., Citation2011). This spirit of challenge was adopted in the early days of industrialisation as the group’s organisational culture, given the success of construction and shipbuilding industries.

In the early 1970s, Hyundai’s joint venture with Ford failed. Thus, Hyundai developed its first car model, Pony, in line with the Long-term Promotion Plan for the Automobile Industry established by the government. Hyundai supported the Pony project by transferring engineers in other subsidiaries to its company and utilising management resources. These dispatched engineers, who were successful in the early periods of Hyundai Construction and Hyundai Shipbuilding, were instrumental in the completion of the Pony project as Hyundai’s first self-branded car (Kim, Citation1998, pp. 518–519). This success encouraged sharing of the group’s organisational culture; Hyundai has since established its leadership position in the Korean auto industry. Hyundai’s corporate culture has also been associated with the spirit of challenge.

Project-based problem-solving capability, in this sense, corresponds to the specific integration of the spirit of challenge in an organisational dimension. Hyundai, in other words, can be characterised by a project organisation in which the development, production, and regular replacement of new car models are the targets (Whitley, Citation2006). These project-based, problem-solving abilities have contributed significantly to Hyundai’s ongoing success regarding the development of their self-branded car models. These engineers, by adopting and assimilating major foreign technologies in these models, have been crucial in providing Hyundai with a competitive advantage. Thus, the success of a series of projects is primarily attributed to Hyundai engineers’ prior learning and commitment. Furthermore, they emphasise efficient technological learning by collectively assimilating the concept of ‘challenge’ into the spirit of Hyundai.

Hyundai, following the success of the Pony project, has developed an organisational culture that meets its targets through the regular, repeated development and production of its car models. The company’s CEO has also contributed to this culture by providing employees ‘carrots and sticks’, and particularly in times of crisis situations (Wright, Suh, and Leggett, Citation2009). As per an interview conducted in 2013,

the nature of Hyundai’s organisation culture seems to be the gumption to be intensively done in times of crisis. Once a target would be given, employees must be prone to reach it by all means through collaborating collectively and showing driving force strongly.

In Hyundai’s early days, there was an inadequate number of skilled engineers. Thus, many engineers learned to perform tasks through trial and error, rather than being systematically educated. Nevertheless, they were trained with an ability to meet targets at all costs.Footnote9 According to one respondent,

At that time it was natural to get a job in the auto company when graduating from mechanical and related engineering schools. While I stuck to my job of product development and production after my entry into the company, time has so quickly flown. Once the goal was fixed, we must accompany it at any costs on time. Although I have so far gone through all kinds of troubles beyond description, I find my experience very rewarding.

4.2. Systemisation of skill formation as a touchstone for the post-catch-up period

Engineers’ skills prior to the 2000s were embodied as Hyundai’s ‘project-based, problem-solving ability’. Engineering skills since the 2000s have been intensified systematically to steer Hyundai’s strong growth. Those skills acquired through trial and error prior to the 2000s, in other words, have been more systematised through adequate education and training during Hyundai’s substantial growth period.

After the 2000s, as illustrated in and , Hyundai engineers developed their skills through education and training in their current job titles. The company provides education and training programmes for white-collar workers, including engineers, according to their job titles and posts. These programmes for firm-specific skill formation begin with the open recruitment of engineers at the Hyundai Motor Group level, who are then subject to an educational course for newcomers, followed by off-the-job training, then OJT to facilitate the performance of assigned tasks. They take off-the-job training courses of two and three weeks, for the group and Hyundai, respectively. Organisational culture as a core value of ‘challenge’ permeates newcomers through these training courses, involving Hyundai’s history, its core values and basic vehicular knowledge. After their appointment to relevant departments, such as production technology or quality management, they train intensively, involving an off-the-job education of three or five weeks, and OJT in the relevant department.

Table 5: Education and training of newly recruited engineers in Hyundai.

Table 6: Education and training of incumbent engineers in Hyundai.

notes the education and training courses for Hyundai’s incumbent engineers. Promotion candidates take online courses for automotive structural engineering and labour laws, while engineers on the promotion list receive a consecutive three-day training course, for three modules by job title. Engineers with two to five years’ seniority are also asked to take isolated remedial education, according to the results of competency evaluations. Moreover, production engineers with low scores for annual personal capacity are provided improvement courses. If their scores were lower than B, out of a scale of S, A, B, C, and D, they are required to take three-day educational courses to supplement their personal capacity for the item in question (interview, 2013).

Hyundai has also recently enhanced routine education and training to improve engineers’ abilities. First, all employees across all job functions receive special education, for example, ‘how to think in a creative way’, for a specific time. Second, the training for specific jobs, including product quality, finance, personnel and labour management, and marketing, is conducted under ‘00 Academy’. This one-week training is compulsory for an assistant manager or lower position, but is voluntary for a manager or higher. Finally, an annual education programme is conducted every four years. This programme is known as the ‘Global Expert Program’, and focuses on competent middle managers. These middle managers are appointed based on a combination of their education and personnel appraisal scores (interview, 2013).

Hyundai, as aforementioned, has systematised the upgrading of engineers’ skill programmes since the 2000s as a litmus test for the post-catch-up question. What are the characteristics of this skill formation, which has been performed for engineers since the 2000s? The most important concept is that the project-based, problem-solving capability, considered as an engineering skill prior to the 2000s for catch-up, retains significance after the 2000s. and note that attributes of organisational culture persist that support the catch-up even after the 2000s. Most of the current study’s respondents consider the achievement of project targets as this culture’s most important characteristic. Moreover, they feel the strongest sense of belonging to their respective teams and working groups regarding organisational level.

Table 7: Striking characteristics in the organisational culture of Hyundai.

Table 8: Organisational units in which Hyundai engineers feel a sense of belonging.

Despite the existence of continuity in Hyundai’s organisational culture, the results of the survey questionnaire report an attribute distinct from that prior to the 2000s, that is, ‘collaboration’. Hyundai biannually holds seminars within the team, and between teams, to spread its core values to engineers. The conference is then annually organised by an umbrella body, in which team leaders present what was discussed in the team. The annual survey evaluates the extent to which engineers assimilate Hyundai’s core values (interview, 2013). As presented in , 56.0% of the respondents regard ‘collaboration’ as the company’s most important core value. Prior to the 2000s, ‘challenge’ was considered as a core value of the company. The post-2000 period witnesses ‘collaboration’ as its core value. This change seems to reflect an increase in the need to communicate and cooperate with outside companies, arising from increasing outsourcing through platform integration and production modularisation in the 2000s. On the other hand, this could be attributed to a surge in the need for intra-firm collaboration and communication, resulting from a growth in the company’s size and complexity. In other words, Hyundai’s vertical, hierarchical mobilisation system and self-interested departments’ behaviours, established and intensified for quick catch-up, should be overcome through communication and cooperation. above demonstrates that the training courses, to supplement engineers’ personal capacity who have two to five years’ seniority, appear to target acquiring a core value of ‘collaboration’.

Table 9: The most appreciated core values of Hyundai.

However, the results of the survey questionnaire report that Hyundai engineers’ skills can be characterised as industry-specific, or those that are transferable within the industry, rather than firm-specific, or skills that are only useful within the firm (Lauder et al., Citation2008). As indicates, 51.3% of engineers considered industry-specific skills to be more important than firm-specific ones (6.3%); thus, most engineers cultivate this type of skill. shows that 41.3% of the respondents were dispatched to other departments, and to overseas plants. This result suggests that Hyundai has implemented significant intra-personnel exchanges. Although engineers’ skills are firm-specific in light of the conditions of labour markets, they cultivate additional and substantial skills through these dynamic interchanges. Concerning the durations of dispatch, 22.1% of respondents have less than one year of employment, followed by those with one to five years (32.3%), and those with more than five years (45.6%). Active personnel exchanges, in this regard, occur over the long term; see also .

Table 10: Application range of knowledge or technology acquired from Hyundai.

Table 11: Personnel appointment to other departments (including overseas plants).

Table 12: Terms of personnel appointment to other departments (including overseas plants).

Hyundai engineers who have been recruited from the top engineering schools in Korea, as aforementioned, have developed their skills through project-based problem-solving, in conjunction with the corporate culture of a challenging spirit. Skills acquired through trial and error have been systematised through various OJT, and are a foundation on which Hyundai has developed its own production system since the 2000s. During that time, Hyundai engineers were additionally asked to accept a core value of ‘collaboration’, and accumulated general and/or industry-specific skills through participation in a variety of projects.

4.3. Theoretical implication of engineers’ skill formation

How can Hyundai engineers’ skill formation be understood in theoretical terms? Thelen (Citation2004) and Streeck (Citation2012) discussed skill formation from an institutionalist perspective to determine its relevant theoretical implications. Thelen (Citation2004) distinguished between general and specific skills, and argued that both skill sets can complement, rather than conflict with, each other. For instance, the effective establishment of general skills through universities’ engineering education system can save on the costs of OJT to develop firm-specific skills after hire, and vice versa.

Hyundai engineers’ skills in this regard have primarily applied scientific knowledge derived from the university engineering education system in Korea. These general skills can significantly enhance Hyundai’s production system. However, the effect of firm-specific skills formed through training and OJT may be more significant. Thus, both skills can combine and interweave to complement each other. Furthermore, even Hyundai engineers’ industry-specific skills can be treated as firm-specific because the company monopolises the domestic market as a result of the development of the internal labour market. These factors are detailed in subsequent sections.

Streeck (Citation2012) also discusses the dichotomy between general and specific skills, both theoretically and in depth. These skills are differentiated not only by the transferability of skills given the conditions of labour markets, but also by their substance. Therefore, specific skills that are non-transferable can be classified into various general skills in terms of substance. The skills of Hyundai engineers, in this regard, may not be highly transferable under the circumstances of Korean labour markets because Hyundai offers the best wages and corporate welfare system in the Korean auto industry. Nevertheless, the active promotion of personnel exchange within the company can generally enhance and broaden its engineers’ skill set; see also .

Table 13: General versus specific skills: Transferability versus substantive contents.

5. The production system of Hyundai and the roles of engineers

This section illustrates some examples of Hyundai’s engineer-led production system, and demonstrates how these engineers complement the limited skills of production workers. Engineers cannot work directly on the shop floor. Thus, this paper investigates the ways in which Hyundai engineers have attempted to prevent product defects, to improve product quality through project-based problem-solving and communication and cooperation among them, and to systematically offset the inadequate skills of workers since the 2000s.

5.1. Pre-emptive problem-solving through pilot production

Hyundai’s new vehicle development is most significantly characterised by its pilot centre. At the large Namyang pilot centre near Seoul, which was constructed following the merger between Hyundai and Kia, all problems that may be encountered during the mass production of new cars can be detected in advance, and addressed through pilot production. This task was previously performed by the pilot production department at Hyundai’s production technology centre. The pilot centre belongs to the quality management department, and engineers have primarily solved problems incurred at the development stage.

By the implementation of pilot production lines, similar to those in the mass production plant at the pilot centre, skilled workers can produce approximately 100 vehicles in stages P1 and P2 over a period of 1.5 months when new car development is initiated. During vehicles’ pilot production, engineers can modify car designs and determine assembly and product quality problems in advance. Pilot production has developed technically with the accumulation of experience and data in the pilot centre. The pilot centre’s efficiency shortens the duration necessary to get new vehicles’ mass production back on track, from six months to less than one month. The large-scale pilot centre constructed by Hyundai highlights the company’s advanced car development that differs from the Japanese production system, which emphasises shop floors operated by skilled workers.Footnote10 Pilot production significantly affected all new vehicle development processes by more than 50% (interviews, 2013).

5.2. Quality improvement through informatisation

Engineers also complement workers’ limited skills through a foolproof system that uses innovative production technology on the shop floor. This system prevents workers’ mistakes and negligence on the shop floor from affecting product quality, and prevents the installation of parts with incorrect specifications for processes with complex requirements. It was developed by production technology engineers based on advice from their counterparts at the assembly plants. Major carmakers also adopt a comparable system, but Hyundai exploits theirs because of the limited participation of shop floor workers.Footnote11

This foolproof system has four stages. When a vehicle approaches a production line in the first stage, a parts box signals the correct specification. The vehicle then enters the production line in the second stage, and the correct specification is displayed on a computer screen. Thus, workers not only receive the specifications of critical components on screen, but they also assemble these parts by scanning their barcodes after acknowledging the light signal from the parts box. During parts assembly in this stage, the impact driver automatically stops when the fastening of bolts and nuts reaches a certain level of torque. When the lamp emits a red light, workers are warned against assembly. The assembled products’ quality is automatically inspected in a full-length test involving U-robots in the final inspection stage. The efficiency of this system has considerably limited the production of defective products (interviews, 2013).

The system is typically applied during the introduction of new models. Engineers in the production technology centre improve the system based on the suggestions of workers or other engineers. A successful enhancement is then extended to the other plants. Moreover, this system supports most of the assembly plant processes that frequently encounter problems. Hence, responsibility is easy to investigate because the history of the production processes is recorded in the system.

Recently, Hyundai has attempted to prevent workers from assembling parts inaccurately by simplifying and integrating various parts, and by modifying the structure of parts specifications from the car design stage. The company, in other words, fundamentally limits mistakes in car designs, wherein similar parts are commonly used in vehicles with different specifications, or those wherein the structures of components in a single model are differentiated locally. This attempt to improve product quality by design modification can be attributed primarily to the development of the foolproof system. Hyundai engineers, in sum, complement shop floor workers’ limited skills by innovating production technology, and modifying parts’ design (interviews, 2013).

5.3. Quality management

The quality headquarters (HQ) is pivotal to Hyundai’s quality management, as it establishes some product quality standards and evaluates achievements by generating feedback. If a new car does not meet a quality standard in terms of design or pilot production, its development cannot proceed to the next stage. This product quality management technique considerably enhances design quality. Additionally, the improvement in Hyundai’s product quality can be attributed to the enhanced quality of supplied parts. Upon the initial receipt of parts from suppliers, the quality management HQ directly audits the parts. This department urges suppliers to fix any problems in pilot production by modifying the parts design. This process not only improves the initial quality of vehicles, but also enhances the products’ durability.

Hyundai maintains a certain level of quality in new models by holding frequent, regular conferences on quality control, the participants of which include the design, purchasing, quality control and production technology departments. At these conferences, these parties review experiences with old models at the initial mass production stage. Therefore, Hyundai continues to improve its product quality even after the mass production process has stabilised, in terms of quality control. Hyundai prevents the recurrence of accidents by modifying designs and innovating processes based on customer complaints and quality-related information. As a result, Hyundai attained a final acceptable quality level of approximately 92%, compared with the 95% reported by Toyota (Jo, Park, Cho, and Lee, Citation2008, p. 48).

However, active engineer-focused Six Sigma movements were halted in the 2000s because they did not fit into Hyundai’s situations. These movements were proposed by the quality control education team at HQ, and the Six Sigma method was initially developed and expanded by Motorola as a tool to improve product quality. This initiative aimed to lower the statistical probability of product defects to two billionths, and to effectively improve product quality. The Six Sigma method uses statistical analysis, rather than unconditional hard effort, to reduce errors.

However, this method has not improved quality for Hyundai engineers, who more highly regard the ability to solve problems empirically through project implementation. The results of a complex statistical analysis are inferior to engineers’ empirical intuitions, in a general manner. HQ initially implemented the Six Sigma method actively, but it fizzled out in 2011 when the level of a company division was empowered to voluntarily undertake the method. Moreover, Hyundai engineers prefer to work in terms of project-based problem-solving (interview, 2013). The application of the Six Sigma movement within Hyundai implies that engineers’ skills are more than simply technical. Hyundai engineers, in other words, apply not only their own scientific knowledge, but also tacit knowledge obtained from experiences with long-term, project-based problem-solving.

5.4. Favourable business performance of Hyundai after the 2000s

Can Hyundai’s success after the 2000s be justified as a litmus test of the post-catch-up question? The catch-up question is related to narrowing the gap between the follower and frontier in terms of product quality, productivity and business performance. As indicated in , as of May 2013, the Hyundai Motor Group came in second, seventh and sixth in terms of profits, assets and sales, respectively, boasting substantial business performance. Hyundai withstood the business performance list of world carmakers in the 2010s. Arguably, to consider Hyundai as a leader in the auto industry through time, it is insufficient to rely on production size and management performance. However, as discussed thus far, an historical perspective on the growth of Hyundai’s engineer-led production system in the 2000s may address the post-catch-up question.

Table 14: Management performance of major carmakers (as of March 2013, billion $).

6. Internal labour market for engineers

Engineers’ aforementioned skills were critical in the advancement of Hyundai’s production system after the 2000s, due to the existence of engineers’ skills accumulated during its catch-up phase. Thus, the influential factor in engineers’ commitment to this advancement is determined, and the internal labour market for engineers is explored, which has intensified since the 2000s.Footnote12

Hyundai engineers’ said skills are industry-specific skills, rather than firm-specific. Furthermore, their job turnover is rare, which reflects Hyundai’s status as a monopoly in the car industry. A tripartite competition market structure was established in the mid-1990s among Hyundai, Kia and Daewoo. However, following the late 1990s’ auto industry restructuring, Hyundai acquired Kia and monopolised the Korean vehicle industry, with a market share of approximately 70%. Engineers had no incentive to transfer elsewhere as a result. Hyundai engineers enjoy wages and fringe benefits that are superior to those of other competitors; thus, they commit to intra-competition and promotion. Movements to other companies are rare even in job-specific cases, such as computer simulations, because the wages offered by Hyundai are very high (interview, 2013). The skills of Hyundai engineers, in sum, become firm-specific, although they are technically considered industry-specific, because the company monopolises the market and because the internal labour markets for engineers have progressed (interview, 2013).

The internal labour market for Hyundai engineers has changed considerably since the 2000s. This change emphasises the human resources’ personnel competence appraisal system. Moreover, promotion and compensation practices have shifted. These alterations promote intra-competition and skill formation.

6.1. Promotion system

This section examines how the promotion system supports engineers’ skill formation. illustrates the personnel management system for Hyundai’s white-collar employees, including engineers.Footnote13 New recruits can be promoted according to a job ladder that consists of four levels, which require four or five years of experience. However, promotions are not automatically granted with time. Managers who supervise section chiefs can be screened for promotion if they meet certain competency and performance scores in the annual evaluation conducted by the team’s leader. Evaluation scores, which are assessed over five levels (S, A, B, C, and D), carry equal weight. The competency evaluation covers the company’s core values, job competency and leadership, whereas the performance appraisal considers the extent to which the target agreed upon by the employee and the team leader during consultation is reached.

Table 15: Promotion requirements for white-collar workers in Hyundai.

The personnel appraisal is scored as 100, 75, 50, 30, or 10. An employee can be promoted early if he or she continuously attains a score that exceeds the B level. However, promotion is not immediate, even if the required scores are satisfied. Depending on the number of candidates for promotion to a certain level, some can be promoted through screening.Footnote14 Thus, internal competition for promotion has gradually intensified (interview, 2013).

The hierarchical department/section system of Hyundai’s personnel management changed in 1998 to a novel team system, following a mass recruitment of white-collar workers in the mid-1980s, which resulted in severe personnel congestion. The new system distinguished job positions from job titles. The team leader supervises all organisations; hence, individuals with the same job title vary according to the team position. Conventionally, a team organised by the department head constitutes a basic unit; however, teams may be led by chief executives depending on size, as illustrated in . Under this team system, multiple team members may not necessarily hold a position and, as a result, roles in the team are gradually allocated, thereby aggravating human relations problems.

Table 16: A separation between job position and title.

As illustrated in , most engineers are pessimistic about their promotion prospects. This viewpoint is particularly dominant at the managerial level, whereas the view at other levels is generally optimistic. The pessimistic outlook, for the most part, is slightly more prevalent than the optimistic one, although prospective promotions are divided. Engineers, in sum, are concerned about their promotion prospects as the competition over position-based promotion intensifies.

Table 17: Prospects for the promotion of Hyundai engineers (%).

6.2. Compensation system

This section discusses Hyundai’s compensation and reward system. This company has implemented the team and annual salary systems only for managers, since 1998.Footnote15 As indicated in , managers’ pay system is commensurate with wage growth rate, depending on the increment in base-up wage,Footnote16 as per performance evaluation. If the rate of increase varies, the S and A levels differ significantly with the increment. Moreover, the difference in basic salary within the year and merit pay, which is based on the salary of the previous year, increases. Although the salary step system is applied to white-collar workers, managers are subject to the annual pay system based on competence evaluation. This system generates a remarkable wage gap between managers. When a differential increase in wage is maintained for several years, the gap in salaries at the same level must be gradually widened. Thus, the personnel appraisal strongly affects promotion prospects, and widens the pay gap. Furthermore, the performance-based annual salary system is commensurate with engineers’ competence and performance. Thus, compensation is differential, and is an institutional catalyst that encourages competition among engineers in the same department (interview, 2013).

Table 18: Annual salary system of Hyundai (1000 won).

Hyundai engineers were generally satisfied with the company’s offered system of wages and fringe benefits. As noted in , job performance was typically reflected positively in their employees’ wages. However, indicates a link between team and department performance and wage, and reports that the amount of positive responses was only slightly higher than that of negative ones regarding individual performance. This result implies that Hyundai’s salary system is based on the differential compensation system in relation to such performance.Footnote17 Engineers, as displayed in , consider Hyundai’s wage level and welfare system to be superior to those of domestic competitors in the auto industry. This observation can be linked indirectly to the extremely low, near-zero turnover rate.

Table 19: Extent to which Hyundai compensates the performance of an individual in wages.

Table 20: Extent to which Hyundai compensates the performance of a team in wages.

Table 21: Extent to which wages and company welfare packages of Hyundai exceed those of its competitors.

Engineers’ aforementioned skills and commitment, which reify the project-based problem-solving ability, are supported by a promotion and reward system in the internal labour market. The effect of changing jobs and companies in the same industry is negligible, and engineers must, therefore, compete with one another for promotion to Hyundai’s upper echelons. Additionally, engineers must significantly improve their performance in the company because enough compensation is made in terms of wage level and the welfare system. Therefore, Hyundai’s internal labour market is a factor in the progression of the company’s technological capabilities, and engineers participate and commit to this endeavour.

7. Conclusions

This study discussed the formation and development of Hyundai engineers’ skills based on project-based problem-solving ability, and examined their roles in the strong growth of Hyundai, especially after the 2000s, as these skills have complemented the limited skills of shop floor workers. The characteristics of Hyundai engineers’ skills were formed through interactions between Hyundai and Korean institutions. Their skill assets appear to have contributed decisively to the development of Hyundai’s distinct production system after the 1998 financial crisis and, subsequently, to Hyundai’s strong growth. Moreover, as Hyundai monopolised the domestic market in the 2000s, its internal labour market appears to be a factor that encouraged engineers to perform at their best instead of leaving the company. Hence, the system of promotion and rewards, based on the internal market of this large monopoly, is a strong incentive for Hyundai engineers regarding skill formation and commitments.

However, the skill formation of, and the internal labour market for engineers in this area has the following problems: First, it is difficult to continuously upgrade the Hyundai engineers’ capabilities given a relatively low level of 2.1% in R&D expenditure for Hyundai in 2013, compared with that of its competitors, for example, Toyota with 3.7% and VW with 5.8%. Particularly, given the fierce competition in the development of next-generation automobiles, including electric cars and fuel cell vehicles, engineers’ skills cannot expect to be further upgraded without a substantial increase in Hyundai’s R&D expenditures.

Second, a challenging issue exists regarding the inter-generational transfer of Hyundai engineers’ skills. Senior engineers have been able to share diverse experiences, and to undertake a wide range of jobs, through the accumulation of project-based problem-solving capabilities. With the technological enhancements within Hyundai and the increase in the proportion of new-generation engineers, a more systematic job training system should be implemented to further facilitate skill formation. Among white-collar workers at the Ulsan plant, workers with service durations of less than 10 years and more than 21 years both exceeded 40%, whereas 18.8% were white-collar workers with a service duration ranging between 11 and 20 years, as illustrated in . The middle range of white-collar workers is relatively small. Generally, 2046 white-collar workers will retire within 10 years, or a ratio of 17.9%. Thus, more systematic education and training can facilitate the transfer of Hyundai’s senior generation’s empirical skills to the next generation.

Table 22: Service years of white-collar personnel at the Ulsan plant of Hyundai.

Finally, engineers’ burdens have increased because they complement production workers’ limited skills in various ways. Moreover, production engineers are concerned not only with their own technical tasks, but also with labour management. The strike effect can expand significantly with the production flow that characterises the auto industry. Thus, these burdens can significantly reduce engineers’ chance at a happy family life.

Given changing domestic and overseas environments, Hyundai is faced with a new agenda, which postulates that qualitative upgrading should extend beyond catching up with advanced automakers. Thus, Hyundai’s future prospects depend on the extent to which the company can actively fix the aforementioned problems through its production system. Hyundai’s strong growth after the 2000s could be considered as a mixture of catch-up and post-catch-up, and not as clear empirical evidence of the latter. There are several reasons for this; first, Hyundai has not augmented its breakthrough production system and developed innovative vehicles. However, Hyundai has demonstrated a resilient organisational adaptation to internal and external conditions, integrating committed engineers’ skills into the company’s own production system in an agile way. Second, it would be difficult for other followers to imitate the case of Hyundai because this company is an historical and institutional product of hierarchical governance, as in the chaebol; monopolised domestic market structure; subsequently committed engineers; and antagonistic industrial relations, bringing about controversial issues regarding the Hyundai production system model’s instability, path-dependency, and sustainability. However, Hyundai has overcome Western pessimism to survive in the auto industry. The case of Hyundai, in summary, as a litmus test of the post-catch-up question appears to be a mixture of discontinuity and continuity, which is reminiscent of the concepts of ‘POST-catch-up’ versus ‘post-CATCH-UP’, although Hyundai’s remarkable business performance and production size, ranked Top Five in the 2010s, is undeniable for the company as a latecomer.

Acknowledgements

We thank the guest editor and anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments regarding the previous version of this paper. Based on these comments, we clarified the study’s points.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The number of firms, volume of production and employment rate in the Korean automotive industry respectively account for 5.8%, 11.4%, and 10.7% of the total manufacturing industry, as of 2011.

2. Toyota, GM and Volkswagen (VW) are fierce competitors at the top of the industry, followed by Renault-Nissan, Hyundai, and Ford.

3. This VDS determines the amount of problems reported by the original owners of three-year-old car models over 202 items, and scores these complaints in the form of the average number of consumer issues for every 100 cars. As per the 2011 VDS, 132 defects were reported for every 100 Hyundai vehicles, which was less than those of Honda (139), Ford (140), and VW (191). This result indicates an improvement in car quality that matches that of the best globally. Hence, the value of used Hyundai cars is expected to increase in the near future.

4. Various studies on the internal labour market of Korean manufacturing firms have primarily focused on the formation, transformation and function of production workers’ internal labour market (Jung, Citation1992, Citation2003; Joo, Citation2002) and hardly on that of engineers. This study argues that a critical factor in Hyundai’s strong growth and skill formation is the development of engineers’ internal labour market, rather than that of production workers.

5. Detailed personal information regarding the interviewees, which is displayed in , cannot be retrieved because of company security and personal privacy.

6. The white-collar office job category involves managers who are in charge of indirect tasks, such as finance, production management, personnel management, strategy and planning other than production engineers.

7. R&D prior to 2000 was classified under the white-collar office job category. However, it has since been considered an independent category because R&D investment has increased with Hyundai’s technological progress. Thus, the proportion of R&D engineers has increased with respect to total employees.

8. The ratio of subcontracted in-house production workers has increased by 20–30%. Hence, Hyundai can handle an increase in the total number of produced vehicles, even if the total number of regular workers remains constant.

9. In the formation of skills specific to Korean companies, Lauder, Brown, and Ashton (Citation2008, p. 22) report that a high degree of general education is necessary prior to the entry of employees into internal labour markets. This finding is particularly true for engineers in Hyundai, whose skills must be supported by a certain level of university education. In this regard, engineering schools with excellent reputations nurtured a qualified workforce for automotive companies from the 1970s to the 1980s.

10. Toyota has a pilot centre; however, it is small because the company focuses on feedback from skilled workers on the shop floor.

11. Workers at Toyota installed parts accurately by referring to the specification table. They then memorised the parts specifications according to the vehicle type for installation. However, with the recent increase in the proportion of irregular workers, Toyota has introduced the kit system, in which parts are supplied in advance according to specifications to avoid the parts’ inaccurate installation (Oh, Citation2013).

12. This section limits the discussion to internal labour markets for production engineers. R&D engineers are similarly recruited and trained, but their labour markets differ in terms of specific elements, such as job demarcation, the job ladder and promotion system.

13. In the early 1990s, Hyundai did not introduce a new personnel management system for employees’ systematic skill formation because it did not fit into the circumstances at the time (interview, 2013).

14. Clerk and assistant managers are screened for promotion according to biannual personnel appraisal scores when they reach the promotion term. The accorded scores are similar to those of mangers in terms of evaluation items and levels. Thus, clerk- and assistant manager-level promotions are relatively less competitive than manager-level ones.

15. White-collar workers are labour union members. Hence, they are under the same seniority-based wage system as production workers. However, the compensations of their efforts differ in terms of various aspects, such as promotion, recognition of the boss as sponsor, and opportunities for education, training and overseas assignment.

16. The increases in base-up wage are determined according to wage negotiations among management. Thus, the costs of labour and price increase. Regardless of union membership, performance-based lump-sum bonuses are paid to workers at the end of the year, as with managers. For example, Hyundai’s performance-based bonus corresponds to 350% of the base salary, and five million won of lump-sum pay as a result of wage negotiations between the labour force and management. This method is similarly applied to white-collar workers, who are not part of a labour union and are not managers.

17. Although the performance-based salary system is applied to Hyundai managers, the gap between individual competence and performance is considerable compared with companies in the electronics industry. The influence of the labour union in this industry is stronger than in other Korean industries. Moreover, the integrated and large-scale auto industry emphasises cooperation rather than individual performance. Hence, collective compensation is still highly regarded. The annual lump-sum, performance-based bonus granted to all employees at the end of the year may be a typical example of the collective compensation system (interview, 2013).

References

- Amsden, A.H. (1989), Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Black, J. (1997), Oxford Dictionary of Economics, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fujimoto, T. (2003), Nōryoku Kōchiku Kyōsō: Nihon No Jidōsha Sangyō Wa Naze Tsuyoi No Ka [ Competition on the Basis of Constructing Capabilities: Why the Japanese Auto Industry is Strong], Tōkyō: Chūō Kōron Shinsha ( in Japanese).

- Hattori, T. (1997), ‘Chaebol style enterprise development in Korea’, The Developing Economies, 35(4), 458–477. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1049.1997.tb00857.x

- J.D. Power (2013), ‘JD Power survey 2013 – Overall results,’ http://www.whatcar.com/car-news/overall-results/1206902.

- Jeong, J. (1995), ‘The failure of recent state vocational training policies in Korea from a comparative perspective’, British Journal of Industrial Relations, 33(2), 237–252. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8543.1995.tb00433.x

- Jeong, J. (1999), ‘Skill formation of college graduated engineers in large sized Korean firms: an analysis from an international comparative perspective’, Korean Journal of Labour Economics, 22(2), 163–187 ( in Korean).

- Jo, H.J. (2005), Work and Employment in Automobile Industry, Seoul: Hanul Academy ( in Korean).

- Jo, H.J., and Kim, C. (2013a), ‘Conversion from the captive type to the modular type in the supplier relations: focusing on the case of Hyundai Motor Company’, Korean Journal of Sociology, 47(2), 149–184 ( in Korean).

- Jo, H.J., and Kim, C. (2013b), ‘Evolution of flexible production system based on the conversion into collusive labor relations’, Korean Journal of Labor Studies, 19(2), 67–96 ( in Korean). doi: 10.17005/kals.2013.19.2.67

- Jo, H.J., Park, T.J., Cho, S.J., and Lee, M.H. (2008), An Exploratory Study on Hyundai Production System, Ulsan: Hyundai Motor Company ( in Korean).

- Joo, M.H. (2002), ‘The changes of internal labour market structure since ‘IMF economic crisis’ in Korea: a case of Hyundai Motor Company’, Korean Journal of Labour Studies, 8(1), 75–112 ( in Korean).

- Jung, E.H. (1992), ‘The change of internal labour market and industrial relations in manufacturing industry in Korea’, Ph.D. dissertation, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea (in Korean).

- Jung, K.H. (2003), ‘An institutional economics’ approach to the structural changes of labour markets’, Economy and Society, 57, 8–41 ( in Korean).

- Kim, C., Jo, H.J., and Jeong, J.H. (2011), ‘Modular production and Hyundai production system: the case of Hyundai MOBIS’, Economy and Society, 9, 351–385 ( in Korean).

- Kim, L. (1998), ‘Crisis construction and organizational learning: capability building in catching-up at Hyundai Motor’, Organization Science, 9(4), 506–521. doi: 10.1287/orsc.9.4.506

- Kirk, D. (1994), Korean Dynasty: Hyundai and Chung Ju Yung, New York: DRT International.

- Korea Automobile Manufacturers Association (2013), ‘Statistics of Automobile Industry’, http://www.kama.or.kr/.

- Korea Automotive Research Institute (2013), 2013 Korean Automotive Industry, Seoul, Korea.

- Lauder, H., Brown, P., and Ashton, D. (2008), ‘Globalisation, skill formation and the varieties of capitalism approach’, New Political Economy, 13(1), 19–35. doi: 10.1080/13563460701859678

- Lee, B.H., and Jo, H.J. (2007), ‘The mutation of the Toyota production system: adapting the TPS at Hyundai Motor Company’, International Journal of Production Research, 45(16), 3665–3679. doi: 10.1080/00207540701223493

- Levy, B., and Kuo, W.-J. (1991), ‘The strategic orientations of firms and the performance of Korea and Taiwan in frontier industries: lessons from comparative case studies of keyboard and personal computer assembly’, World Development, 19(4), 363–374. doi: 10.1016/0305-750X(91)90183-I

- McQuaid, R., and Lindsay, C. (2005), ‘The concept of employability,’ Urban Studies, 42(2), 197–219. doi: 10.1080/0042098042000316100

- Oh, J. (2013), Foolproof System in Japan, Tokyo: Mimeo, Department of Economics, University of Tokyo (in Japanese).

- Ravenhill, J. (2003), ‘From national champions to global partners: crisis, globalization, and the Korean auto industry’, in Crisis and Innovation in Asian Technology, eds. W. Keller and R. Samuels, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 108–136.

- Sako, M. (2013), ‘SASE annual meeting 2012, MIT, USA: professionals between market and hierarchy: a comparative political economy perspective’, Socio-Economic Review, 11, 185–212. doi: 10.1093/ser/mws024

- Smith, C., and Meiksins, P. (1995), ‘The role of professional engineers in the diffusion of ‘best practice’ production concepts: a comparative approach’, Economic and Industrial Democracy, 16, 399–427. doi: 10.1177/0143831X95163004

- Streeck, W. (2012), ‘Skills and politics: general and specific’, in The Political Economy of Collective Skill Formation, eds. M. Busemeyer and C. Trampusch, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 317–352.

- Thelen, K. (2004), How Institutions Evolve: The Political Economy of Skills in Germany, Britain, the United States, and Japan, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Womack, J.P., Jones, D.T., and Roos, D. (1990), The Machine That Changed the World, New York: Rawson Associates.

- Wright, C., Suh, C.-S., and Leggett, C. (2009), ‘If at first you don’t succeed: globalized production and organizational learning at the Hyundai Motor Company’, Asia Pacific Business Review, 15(2), 163–180. doi: 10.1080/13602380701698418

- Whitley, R. (2006), ‘Project-based firms: new organizational form or variations on a theme?’, Industrial and Corporate Change, 15(1), 77–99. doi: 10.1093/icc/dtj003