ABSTRACT

This article examines the work of the anonymous Sámi artist and activist group Suohpanterror as an example of Indigenous culture jamming, which uses global visual archives and the social media to articulate a contemporary Sámi subjectivity politically. In a short time, Suohpanterror has gained national and international recognition as a new Sámi voice, which is challenging earlier representations and conceptions of the Sámi. However, instead of focusing upon Suohpanterror’s efforts to address the dominant society, this study is concerned mainly with Suohpanterror’s operation within, and at the fringes of, the Sámi community itself. To this end, I examine Suohpanterror’s entanglements in the small Sámi “uprising” that took place in the social media in spring 2013 around the interconnected issues of Sámi definition, identity and the potential ratification of the ILO convention 169 in Finland. I argue that in the context of a highly politicized national public sphere which is considered insensitive to Sámi perspectives, “liking”, consuming and sharing Suohpanterror’s work online has offered an easy, effective and unmistakably trendy way to publicly identify with a certain set of (Sámi) political views, and to perform a political “us” which feeds, in particular, on experiences of a shared community of knowledge, and of collective laughter.

Suohpanterror, an anonymous artist group known primarily for provocative online poster art disseminated through Facebook, is undoubtedly one of the most transformative phenomena that have emerged within Sámi cultural life in Finland over this decade.Footnote1 Bringing forth imaginaries of direct action and even militancy instead of “silent disapproval”, Suohpanterror has successfully renewed the image of the Sámi and updated Sámi political articulation in the age of the social media. This is reflected already in the name of the group, which ironically negates the attributes that have traditionally been attached to the Sámi as a peace loving and accommodating people, by others as much as the Sámi themselves (see Lehtola Citation1994; Näkkäläjärvi Citation2010, 4).Footnote2 However,, in the present especially the reindeer herding Sámi often find themselves in the firing line when conflicts over land use, natural resources and wildlife protection in the Sámi homeland area flare up (Magga Citation2012; see also Heikkilä Citation2006). While suohpan, in Northern Sámi, is the word for the rope or the lasso used for catching a reindeer, terror in Suohpanterror can therefore be seen to refer to a perceived threat (or resistance) waged by the reindeer herding Sámi, or simply to ironically mimic those contemporary discourses that are hostile to Sámi reindeer herders. According to the artist-mastermind behind Suohpanterror, it was precisely the negative press towards reindeer herding Sámi and the fact that they were called publicly “terrorists” that originally prompted the name and the idea of Suohpanterror.Footnote3

This article will examine Suohpanterror’s work as a case of Indigenous culture jamming, which uses global visual archives and the social media to articulate a contemporary Sámi subjectivity politically. To this end, I shall focus on Suohpanterror’s entanglements in a small Sámi “uprising” (or, as I shall call it here, a Sámi Spring), which took place in the social media in spring 2013 around the interconnected issues of Sámi definition, identity and the potential ratification of the ILO convention 169 in Finland. The vast body of Suohpanterror’s online poster art is often described as an example of decolonial art, which makes innovative use of global visual archives to renew the image and representation of the Sámi, and to make their voices audible within the wider society (for instance, Tamminen Citation2014; West Citation2017). While the ways in which this artist collective is representing the Sámi, and communicating Sámi concerns, identity and resistance to others—to the dominant Finnish society and to international audiences—is certainly also worth exploring, here I am more interested in the meanings and uses that this body of online poster art has for the Sámi themselves, within and at the fringes of the Sámi community, and on the level of local political articulation.

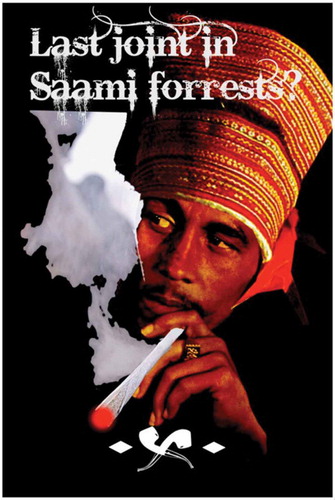

The first online posters associated with the group were uploaded on the newly created Suohpanterror Facebook site (https://www.facebook.com/suohpanterror/) in August 2012.Footnote4 At first sight, they appeared as simple Sámi appropriations of well-known popular culture images, but many of them contained also ample references to local Sámi politics and micro-history. Examples of the early posters include, for instance, a well-known photograph of Bob Marley smoking a giant marihuana joint, but in Suohpanterror’s interpretation, wearing a handsome, high Sámi men’s hat from the Enontekiö area in the North-West (). The meanings conveyed by the image, however, are complicated by the underlying text: “Last joint in Saami forrests?” (sic) which, instead of a general statement, actually refers to a particular, ongoing conflict over natural resources at Nellim in the Inari region, where Sámi reindeer herders together with Greenpeace have struggled against the forest industry to prevent the logging of old forests that are among the last of their kind in Europe, and vital for the life of the reindeer.

The conflict, which was particularly intensive around the year 2005 and which gained strong ethnic undertones also as a conflict between Sámi reindeer herders and Finnish labourers aspiring to gain a living from forest industry (Vartiainen Citation2008), was documented in a film titled Last Yoik in Saami Forests? (2007) by Hannu Hyvönen.Footnote5 Through a direct reference to the documentary, the poster conveys irony and criticism on several different levels. The joint-smoking Sámi-Marley is clearly a peace-loving, even passive, rebel who seeks dissociation from the state and its imposing laws. However,, is it the last joint, or the forest, or both, that we are supposed to be mourning here? And what is the political status of the joint-smoking Sámi? Is he a resilient figure who is subverting the dominant society in his own, particular ways? Or, is he actually represented as a figure of inertia and inaction, smoking a trivial joint and wasting his time while the old Sámi forests, vital to his People’s wellbeing and culture, are being cut down? In summer 2012, there were signs of rapprochement between the Sámi Parliament and the Finnish Ministry of Forestry (the body which was largely antagonistic to the Sámi in the Nellim case), in terms that could be seen as far too compromising. As such, the poster can be interpreted also as a criticism of the Sámi Parliament and its policies, particularly since Enontekiö, represented by the showy hat connected to the area, is the homeland of Klemetti Näkkäläjärvi who acted the president of the Sámi Parliament in Finland that time.Footnote6

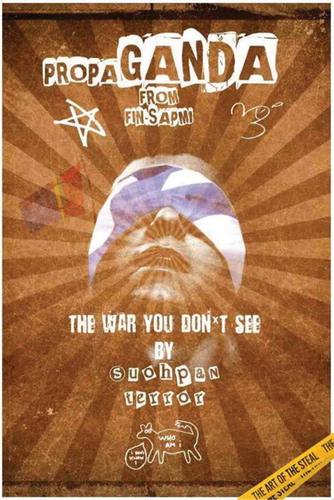

Another example of early posters (uploaded 30 August 2012) presents a hazy image of a blinded male face, whose eyes are bound by the Finnish flag; somewhere behind him, further in the haze, is the Sámi flag (). The image, which is clearly an adaptation of John Pilger’s critical documentary film on media and war propaganda The War You Don’t See (2010),Footnote7 is accompanied by the text “Propa-Ganda from Fin-Sápmi: The War You Don’t See”, undersigned “by Suohpanterror”, and completed by a number of other elements, including two daub drawings presenting a star and a penis; a confused stick dog, who asks “who am I?” and gives a direct answer “I don’t know”; and a yellow caution tape, fixed over the lower right corner, displaying a text “The art of the steal”. Although the image can be interpreted as a general commentary on the invisibility of Indigenous struggles at the face of the dominant society, also here the context matters: this poster refers very clearly to a highly particular struggle that is specific to the situation in Finland and which centers around questions of Sámi identity, and the legal definition of who is considered as a Sámi in official records.

This struggle, which has been ongoing for more than two decades now (but was, in 2012, still less known on the national level than it is today), originates in the 1990s when the political status of the Sámi in Finland was transformed through the institutionalization of the Sámi Parliament, and when talks about the potential ratification of the ILO convention no. 169—involving also Indigenous land rights—began in earnest. Although both the fears and hopes associated with the ILO 169 have been premature—the convention has not been ratified to date—these processes gave rise to a number of long-standing campaigns on behalf of individuals and groups in Northern Finland to expand the legal definition of Sámi in Finland so that more people could join the Sámi Parliament’s electoral roll and hence acquire an “official status” as a Sámi (see Aikio and Åhren Citation2014; Hirvonen Citation2001; Junka-Aikio Citation2016; Lehtola Citation2015; Pääkkönen Citation2008; Valkonen, Jarno, and Koivurova Citation2017). Over time, these campaigns which Pääkkönen (Citation2008) describes in terms of a “local-based counter movement”, have taken on an increasingly professional character, taking place both in the media and the realm of academic research, and also the focus of argument has changed: today the desire to expand Sámi definition is argued for largely on grounds of identity politics, and the more mundane genealogy of interests associated with Indigenous rights has been faded to the background (see for instance Sarivaara Citation2012; Sarivaara, Uusiautti, Määttä Citation2013a, Citation2013b).

It is this kind of the “art of the steal” that the poster, which also seems to make clever use of Sámi language to articulate a position, is referring to (“Ganda” in “Propa-Ganda” reminds one of the Northern Sámi word gánda, which means a boy or young male). Despite the amount of media attention afforded to questions of Sáminess in the Finnish media currently, this “war” over identity—or, as many Sámi see it, a war waged by ethnic Finns to appropriate and take over their Sámi identity—has remained largely invisible, and thus unrecognizable, for the majority of Finns who are not familiar with local micro-histories and ethnic relationships in Northern Finland, and for whom the debate on “who is a Sámi” has, consequently, appeared largely as an internal Sami debate instead of a conflict between ethnic Finns and the Sámi (Junka-Aikio Citation2016). Moreover, the poster’s references to John Pilger’s work point to the active involvement of the media: this is a war against an Indigenous population in which the media has taken an active role through the dissemination of propaganda and outright disinformation.

Who, then, is Suohpanterror? In an early interview, the artist returns the question by asking: “who, indeed, wouldn’t be Suohpanterror?” (Näkkäläjärvi Citation2014).Footnote8 Over time, the number of associates around the successful pseudonym has clearly multiplied, and today it is often characterized as a large group of Sámi artists and activists involving people from Finland, Sweden and Norway. In general, however, Suohpanterror has sought to preserve anonymity, and presented two main reasons for doing so. First, anonymity is described strategic insofar as it helps to focus attention on the issues their work discusses, rather than on the persons that are behind this work. Secondly, anonymity supports also freedom of, and courage to, expression. As one of the group’s members puts it, “here [in Finland’s Lapland] no-one wants to participate in discussion on one’s own name, you will just get into trouble for doing that’ (quoted in Tamminen Citation2014). Given the rather harsh political environment prevailing around issues concerning the Sámi, especially in regard to land rights, ILO 169 and the legal Sámi definition, “speaking out” is not particularly inviting for those living in the small communities in Northern Finland. In this sense, anonymity is not only a strategy, but also a precondition for the strengthening of Sámi voices represented by Suohpanterror.

Despite the commitment to anonymity, some individuals around the group have come out in public, first in 2014 when Finland’s leading newspaper Helsingin Sanomat published a several page interview with Jenni Laiti, a Sámi woman from Inari, who now resides in Sweden and has been particularly active in the protests against the planned mine in Gallok and other struggles related to Indigenous rights and the environment. The group has not clarified whether this “coming out” was a decision taken collectively, and if so, why, but she has, since then, largely acted as the group’s public representative. Another figure is Niillas Holmberg from Utsjoki, who also has moved to Sweden, and who is known more broadly as a Sámi poet, musician and actor. Holmberg’s association with Suohpanterror became particularly visible in October 2015, in the context of an act performed together with Greenpeace in Helsinki, where Holmberg climbed the statue of General Mannerheim which has high patriotic symbolic value for the Finns, and covered it with the Sámi flag, in a protest against the current government’s policies towards the Sámi and the Arctic regions.Footnote9 This notwithstanding, the group’s Facebook page still brands anonymity as a central part of their strategy, and when other members appear in public, they always hide their face behind a balaclava or a ski-mask, in a highly provocative manner which resembles the Zapatistas. For both the Zapatistas and Suohpanterror, the mask effectively serves two main ends: it protects the invisibility and security of the individual at the same time as it underscores collective visibility due to the mask’s high media value and by making the anonymous group into an instantly recognizable, collective actor (Schools for Chiapas Citation2014). Since we cannot see who they are exactly, anyone could, indeed, be Suohpanterror.

Suohpanterror has directly challenged Finland’s self-image as a model country of Human Rights and societal responsibility and equality. At the same time, it has become, in just a few years, a widely recognized, award-winning actor in Finland’s cultural and artistic circles and, increasingly, also abroad. At the beginning, Suohpanterror’s posters were disseminated in the social media mainly by people with some personal connection to, or interest in, the Sámi, but since then their work has appeared in countless national newspaper and magazine articles, in television, in distinguished art exhibitions in Finland and elsewhere, and as illustration in books, academic journal articles and book covers.Footnote10 In addition to poster art, the group is known also for other forms of expression, such as street art, performance, collaboration with musicians, and direct action in support of Sámi rights and the environment. In 2016, the Finnish Critics’ Association SARV presented the group their annual prize “Kritiikin kannukset” in recognition of an unusually powerful and meaningful artistic breakthrough. They praised, in particular, Suohpanterror’s “innovative use of public space”, especially in the internet and the social media, and highlighted the ways in which “this has given them a clear voice also outside of traditional art institutions” (SARV Citation2016).

Accordingly, Suohpanterror has turned, in a relatively short time, into a well-known societal and cultural actor, which is influencing and changing perceptions of the Sámi. Correspondingly, the group is facing also increasing attempts at censorship, which feed freely on Suohpanterror’s ironic, provocative and sometimes even militant style. For instance, Anu Avaskari, a member of the Finnish right-wing party Kokoomus, and a politician in the Sámi Parliament and the municipality of Inari (one of the four municipalities comprising the Sámi homeland area in Finland), has repeatedly compared Suohpanterror to international terrorism. Her public speech, held for the Inari municipality on Finland’s Independence Day in 2016, is a case in point: there, she presents an analogy between the violence and famine faced by suffering children fleeing war and terrorist attacks internationally, and Suohpanterror, which “uses a terrorist title and symbols”, “[D]isseminates violent armed images especially in the social media” and hence, “increases insecurity” locally (Avaskari Citation2016). In Spring 2017, Avaskari blocked Suohpanterror’s participation at a large and significant event on Sámi arts and research in Paris, acting as the representative of Inari Municipality, which was also one of the event’s main organizers.Footnote11 This decision aroused criticism from a number of prominent Sámi artists, who found the municipality’s involvement as an art critic and a curator unacceptable.Footnote12 Since Avaskari is well known for political views that are opposite to those advanced by Suohpanterror—she has, for instance, opposed the ratification of the ILO 169 in Finland, and is an active campaigner for the expansion of Sámi definition—many felt that the treatment of Suohpanterror, in this case, amounted to outright political censorship.

Indigenous culture jamming

Suohpanterror exemplifies new ways in which an Indigenous people may use and re-use the existing landscape of popular images and aesthetic styles familiar from political propaganda art, marketing and the mass media. Most of their posters rely on a globally recognizable archive of iconic pictures, which are given a new, Sámi twist through clever, subtle changes, additions and editing. In this way, Suohpanterror skilfully appropriates popular visual culture to draw attention to issues that they—as Sámi, and as an Indigenous people—want to talk about, and to rearticulate their presence and representation in the present context of late modern, yet persistently colonial, society.

This method, known widely as “culture jamming”, is usually associated with the practices of anti-consumerist social movements such as Adbusters,Footnote13 which seek to criticize assumptions underlying the prevailing commercial, capitalist culture through the subversion and distortion of images and messages disseminated by corporate actors and the world of advertisement. Bart Cammaerts (Citation2007) contextualises culture jamming historically as part of the Gramscian tradition of counter-hegemonic (cultural) struggle, and links it with several artistic and cultural movements that emerged in the latter part of the 1900s, including Dadaism, surrealism, Fluxus and situationism. He points out that the actual notion appeared for the first time in the mid-1980s, when it was used in conjunction with the so-called “billboard activists”. Since then, the IT revolution and the rise of the internet have provided ever-expanding potential for image manipulation, appropriation, distortion and photo doctoring central to the practices of culture jamming.

What Cammaerts argues, however, is that since then, there has been a shift towards the politicization of culture jamming insofar as now culture jamming relates increasingly to politics and political institutions as such. Instead of attacking the corporate world, consumerism and the culture of brands and branding, “political jammers”, as Cammaerts calls them, focus their criticism on governments and government policies, on formal political actors and institutions, and, at times, on undesirable behaviour within society at large. At the same time, jamming has become a technique that is used by a widening spectrum of actors. In addition to “fringe activists”, Cammaerts writes, citizens, mainstream civil society actors and even political parties themselves are now involved in jamming for very different purposes, to advance their own interests, world-views, official party programs, which are not necessarily progressive, egalitarian nor anti-establishment. Accordingly, he emphasizes that as with any form of cultural expression, there is nothing liberating or subversive about jamming as such: the political and societal character of cultural and political jamming depends on the way jamming is done, by whom and for which purposes.

It is very easy to agree with this latter point. However, given the entangled nature of the relations between corporate and governmental worlds, or the capitalist and liberal-democratic systems, separating between cultural and political jamming in the way suggested by Cammaerts seems rather problematic, even if this is done for analytical purposes only, as a means of revealing broader shifts within the art of jamming. In the case of Indigenous criticism and struggles for self-determination, such differentiations make even less sense. Indigenous politics is not just about culture and identity but, even more importantly, about land and land-based livelihoods (Tuck and Yang Citation2012). In practice, these different aspects are entwined to a point at which separating them is not viable: Indigenous peoples’ struggles tend to be directed as much towards settler-colonial states, their histories of conquest and their detailed policies, laws and knowledge systems which uphold the state’s right over those of the Indigenous people, as they are against corporate power and neoliberal regimes, which challenge Indigenous peoples’ rights to natural resources, cultures and heritage in multiple different ways. This, and especially the ways in which Indigenous struggles re-connect political and environmentalist thought, has caused contemporary activists and critical scholars often to regard Indigenous struggles as emblematic of contemporary resistance. In addition to challenging present forms of exploitation shadowed by massive inequality, impending ecological crises and “predatory extractivism” (Gudynas Citation2013, 167), Indigenous struggles are seen to offer other, less exploitation-prone epistemologies and ontologies, and an alternative path to thinking about modernity as such (Gudynas Citation2013; Mignolo and Escobar Citation2013).

In the context of visual activism or “artivism” exemplified by Suohpanterror, it would therefore appear fitting to emphasize that we are talking about Indigenous culture jamming, in this case about the employment and appropriation of dominant visual and media scapes in order to articulate a broad variety of challenges (and possibilities) that Sámi as an Indigenous people are facing and engaging contemporarily. At the time of writing (March 2017), Suohpanterror’s Facebook site entailed already 208 online posters, and the number is rising weekly. These posters tackle multiple issues ranging from environmental and ecological threats such as the ongoing mining boom in Northern Scandinavia, questions of cultural appropriation and assimilation, and the challenges the Sámi are facing on the level of national and municipal politics and jurisdiction. Some of the posters use English, others Finnish, others Northern Sámi and yet few others, Swedish or Norwegian. Likewise, Suohpanterror has emphasized, in various interviews, that their work addresses audiences on different levels: some of the posters target international discourses and audiences, others are for the dominant society on the national level, and yet others are for consumption within local northern communities and by the Sámi themselves.

It is the last of these three levels—local and Sámi—that I find most intriguing. Conversely, this is also the level on which Suohpanterror’s work is least known and appreciated, as in general, reviews of their work fix attention on the ways in which Suohpanterror is confronting the “colonial gaze” and articulating Sámi views and concerns on international and national levels. Suohpanterror is readily assessed for their role at renewing the representation of the Sámi vis-a-vis the dominant society, for bringing forth Sámi perspectives on the level of national visual culture, and for connecting the experience of the Sámi with the broader discourses and history of settler colonialism and Indigenous struggles. In contrast, the remaining parts of this article seek to highlight those aspects of Suohpanterror’s work that address primarily Sámi audiences, and to look at some of the meanings, roles and uses that these images have had for the Sámi themselves. This shift brings attention not only to the concrete, day-to-day character of criticisms waged by the group, but also to the potential of online artivism as such, and to the importance of “sharing” and “liking” as means of producing collective political subjectivities and solidarities.

To this end, I look shortly at Suohpanterror’s entanglements in a small uprising that took place in the social media, particularly Facebook, in spring 2013, around the interconnected issues of Sámi definition, identity and the potential ratification of the ILO convention 169 in Finland. I argue that in the context of a highly politicized national public sphere which many consider insensitive to Sámi perspectives and where the threshold to “speak out” publicly has therefore been very high, “liking” and disseminating Suohpanterror’s work has offered one effective (and also unmistakably trendy) way to publicly identify with a certain set of Sámi political views, and hence to participate in the construction of a political “us” related to issues concerning the Sámi. Moreover, since many of the group’s online posters contain elements and meanings which cannot be decoded and read without a rather good knowledge of specific debates and developments, sharing and liking these posters with others who possess the same knowledge promotes a shared sense of intimacy and togetherness which is not tied to the digital world only. In so doing, Suohpanterror’s decolonial work extends well beyond the politics of representation of the Sámi, to the articulation and construction of a new sense of a community around subaltern Indigenous political struggles that have, so far, received little understanding on behalf of the dominant society and the Finnish state.

Jamming the “Sámi spring”

In spring 2013, public debate on Sámi politics in Finland experienced a new turn when Pekka Sammallahti, Professor Emeritus of Sámi languages and cultures at the Giellagas Institute for Sámi Studies (University of Oulu) began to use Facebook consistently to share his thoughts on the ongoing campaigns to expand Sámi definition in Finland. Although this might not sound eventful as such, these status updates came out at a moment when public discourse on Sámi definition was rather one-sided. During the previous year 2012, the Sámi Parliament had been increasingly attacked and criticized by individuals and groups claiming that its conceptions of who is a Sámi and who is not were outdated, racist and exclusionist. The timing was not coincidental: the Sámi Parliament’s next elections were set for 2015, and since the application process for the electoral roll usually takes place one year before, these campaigns tend to intensify much earlier. Moreover, this time the government of Finland was preparing to open up and revise the Law on Sámi Parliament, suggesting unprecedented space and possibilities for lobbying. All this caused the debate on “who is a Sámi” in Finland to greatly escalate between the years 2012 and 2015.

Also new was the fact that these campaigns had become increasingly professional and also academic in nature: they used the finest terms of postcolonial and postmodern theory, and employed a large arsenal of academic references to articulate their case. This was fuelled, in particular, by the publication of two PhD theses which were used heavily to influence Finland’s policy and law makers—Tanja Joona’s comparative research on the implementation of ILO Convention no. 169 (2012), and Erika Sarivaara’s PhD research Statuksettomat saamelaiset (2012), both of which argued for the potential inclusion of anyone with traces of alleged Sámi family history in the Sámi parliament’s electoral roll—and by the subsequent establishment of VGDS (Vuovde- Guolásteaddji ja Duottar Sámit),Footnote14 an energetic organization led by Dr. Sarivaara, whose main objective was to advance this agenda and the rights of the “non-status Sámi” in Finland. All this left many Sámi, whose perspectives were built on lived experience and deep cultural knowledge rather than theoretical constructions and “research evidence”, feel highly alone and helpless at trying to articulate an opposite position (see Junka-Aikio Citation2016).

The societal and political importance of Sammallahti’s “thoughts of the day” comes into view against this background. The Finnish Ministry of Justice had asked him to prepare an expert opinion on the Sámi definition ahead of possible legal reform.Footnote15 This prompted Sammallahti to read the above-mentioned academic literatures (i.e. Sarivaara Citation2012; Joona Citation2012), and to share his thoughts publicly on Facebook. In a few days, his updates, the first of which was written on 19 April 2013, gathered a large following, becoming a social media phenomenon in its own right. While the first update, “Wrestling with the Sámi definition. There is a hopeless conceptual jumble in so-called research literature, legislation and legal practice” (translated from Finnish by the author) received 30 likes, two shares and prompted a thread of 62 comments, five days later he had already released 10 “thoughts of the day”, each of which was followed by an intensive and detailed debate with threads up to 118 comments long.

Conspicuously, the list of commentators entailed several prominent and/or expert figures, including politicians and academics, many of whom had mutually opposed views on the matters being discussed. As with social media communication more generally, all styles and tones of argument were used, from the scientific to the personal, and from serious to joyful and sarcastic. However, for the most part, the debate followed highly detailed and rich lines of argument, and no stone was left unturned in the battle on how Sáminess should be understood and defined, who held the right of doing so, and whether or not, and how, this question related to the possible ratification and implementation of the ILO Convention no. 169 in Finland. At the height of the debate, new comments would pour in every minute, on several different threads, some of which had already begun several days before.Footnote16

The number of people who followed from the side was even larger. Since Sammallahti’s page settings were public, practically anyone could read them. This does not mean that the discussion itself would have been entirely open: in order to “like” or comment Sammallahti’s “thoughts of the day”, a Facebook friendship was required.Footnote17 However, very often the discussions, which originated on Sammallahti’s page, would spill over also to other Facebook pages upheld by other individuals and also groups, such as the Sami Siida of North America,Footnote18 and take on a life of their own. To promote the internationalization of the debate, Sammallahti began to write some of his “thoughts of the day” in languages other than Finnish, such as English, Norwegian and Northern Sámi. In addition, Yle Sápmi, the Sámi branch of Finland’s national broadcasting company Yle, followed and interacted with the debates closely, lending them support. Many of their news stories in spring and summer 2013 originate in topics and themes that were taken up on Sammallahti’s Facebook page and in subsequent debates.Footnote19

The primary reason why this phenomenon may well be understood in terms of a small-scale uprising, or a “Sámi Spring”, however, is that these were debates that should have taken place in public much earlier. The Sámi in Finland share a long-standing experience of being voiceless within the national public sphere and vis-a-vis the Finnish media—an experience which is probably familiar to most ethnic minorities, and which finds support also in several studies on the politics of representation of the Sámi. These studies have highlighted different aspects of Sámi subalternity ranging from outright media invisibility (Pietikäinen Citation2000) to strong biases and imbalances in the ways in which the Sámi, and issues relevant to them, are (or are not) brought up and discussed in the media and in political institutions alike (Ikonen Citation2011; Magga Citation2012; Olsen Citation2004; Tuulentie Citation2001). The question of “who is a Sámi”, in particular, is a topic that has received disproportionate national and local media attention year after year, but primarily in terms defined by people other than the Sámi (Hirvonen Citation2001; Junka-Aikio Citation2016; Pääkkönen Citation2008: see also Ikonen Citation2011). The debates in spring 2013 may well have been the first in which different perspectives on this topic faced and confronted one another on a relatively even ground, and where direct, public debate on these topics became possible. Facebook, here, provided the kind of open, accessible public forum and a space for deliberation that the national media had never offered.

Although Suohpanterror did not participate directly, many of their posters in spring and summer 2013 were closely involved. Accordingly, sharing Suohpanterror’s images became one way of extending the debates beyond their site of origin, and in so doing, confirmed one’s belonging to the political online community that was consolidating around these debates. One of the most glaring examples is the poster presenting Sámi adaptation of the Facebook “Like” button. (). In this image, which has since been removed from Suohpanterror’s Facebook site,Footnote20 the familiar, white-cuffed Facebook hand giving the thumb-up is dressed in the traditional Sámi dress, gákti, and the English word “Like” has been replaced by the Northern Sámi equivalent, “Liikon”.

The image is highly appealing in its own right, and appears as a textbook example of Indigenous culture jamming, whereby a global brand and a logo is turned into a vehicle of Sámi meaning and message through simple, clever image manipulation. A closer analysis of the context in which the image was released, however, reveals a much more serious and politically meaningful message. As I have described, the scope of the debate initiated by Sammallahti skyrocketed in just a few days, and following, liking and participating in the discussion became a practice in which large numbers of people, particularly Sámi, took part. Given the admixture of politics and recent academic research, much of this debate focused on the relevance and truthfulness of the scientific evidence advanced by the publications in question, most especially in regard to the theses on the “non-status Sámi” (Sarivaara Citation2012; See also Sarivaara, Uusiautti and Määttä Citation2013a, Citation2013b).

This unusual “line of flight” did not go unnoticed, and over time it was not just the comments, but also who officially “likes” which comments that became part of the politics of these debates. On April 24, Sammallahti wrote in Facebook that he had heard that “some parents in the schools of Inari and Enontekiö had demanded that those teachers who participated in the social media debates on the Sami definition should receive disciplinary action”. In reality, participation, in this case, had amounted to the use of the Facebook “like” button. No actual comments were involved. In Inari, the teachers in question were two Sámi teachers who had liked one of Sammallahti’s comments in regard to the Sámi definition and Sarivaara’s research. Subsequently, the head of Inari Municipality’s educational division gave these teachers a verbal warning for their behaviour, and two days later, the municipality of Inari issued a letter instructing all teachers “to be cautious when participating in debates in the social media, and to refrain from taking sides in debates when that might risk the relationship between the school and its pupils.”Footnote21 The document claimed to address all teachers in equal measures, but those unnamed Sámi teachers who had been rebuked for liking comments on Sammallahti’s wall a day earlier, may have found it less general in orientation. In addition, it is worth pointing out that no such documents had been issued before, in the context of social media debates where Sámi political aspirations and people representing them had been heavily targeted.Footnote22

Liikon was Suohpanterror’s response to these events. Placed in this context, the image is loaded with messages of political resistance and resilience, but also humour and laughter, which can be collectively very empowering. The image appears as a direct invitation to share and like anything that bodies such as the municipality of Inari’s educational division, or any other actor seeking to stifle the debate, would not want one to share or like in Facebook. Accordingly, sharing and liking it at the time of its release allowed an instant, visible way to demonstrate one’s solidarity with the teachers and with the efforts to keep speaking critically and to carry on liking things freely, despite the attempts at intimidation and censorship.

Moreover, by being anchored on a specific event which is not obvious to everyone, images such as Liikon participate in the construction of a sense of political collectivity around those who can read the image in the same way, and who like and share it online, knowing that also others sharing and liking it know its particular background and points of reference. Here, shared knowledge, and the sensation of online solidarity and intimacy that follows, become essential to the politics of Indigenous culture jamming. Clearly, Liikon works perfectly well also independently and without background knowledge, and it can be regarded as “decolonizing” also when shared and adored by much broader audiences who might see it primarily as a clever subvertisement, a visual appropriation which loads Facebook with Sámi content. However, the image performs differently for those who share knowledge of its immediate background: awareness of this shared knowledge provokes an experience of an “us” online among those who like and share it “knowing that they know” its origins in the teachers’ case.

The political online community that is performed through liking and sharing Suohpanterror’s work is thus not an ethnic community per se. On the one hand, you do not have to be Sámi or Indigenous to be able to decode the messages hidden in these pictures—what you do need, however, is a good knowledge of, and interest in, the issues and events they refer to, and such knowledge probably cannot be gained without some personal relationship to the Sámi in Finland. On the other hand, there are many Sámi who do not possess such knowledge either, simply because not all Sámi are interested in politics, let alone in events taking place in the social media. In this sense, the political online community performing through liking and sharing Suohpanterror’s work may be best described as an epistemic community, which overlaps strongly with an ethnic Sámi community, but cannot be reduced to it.

Laughing together

Another aspect that is central to such experiences of online collectivity and to Suohpanterror’s politics in general, is laughter. Laughter, it has been argued, is political largely due to its societal nature: since laughing usually entails laughing “with” someone and “at” others, it is constitutive of relations of self/other and us/them, and hence conducive to group formation (Särmä Citation2015). Although this means that laughing is just as bent towards processes of social exclusion as it is towards inclusion, in contrast with other political sentiments such as fear, laughter can appear as an inherently positive force: instead of building terror and apprehension, laughter is prone to relieving distress and anxiety, on both collective and individual levels. For this reason, laughter and humour can be effective especially in the context of minoritarian, feminist and subaltern struggles, where a good collective laugh can balance, and at times even replace, the emotionally burdening and exhausting job of a more confrontational approach associated with the figure of the (feminist) “killjoy” (Ahmed Citation2013; see also Särmä Citation2015, Citation2014, Citation2016).

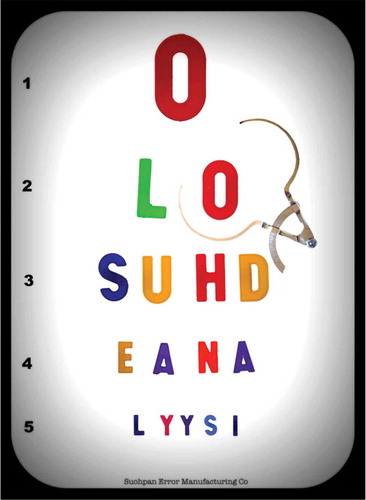

Olosuhdeanalyysi, another poster released during the “Sámi Spring”, exemplifies the ways in which Suohpanterror’s politics of laughter operate in the Sámi context. () The image depicts an optician’s board used for testing sight. Read together, the colourful letters on the board amount to “Olosuhdeanalyysi”, an ad hoc Finnish word, which could be translated as an “analysis of the circumstances”. The two other elements in this picture entail a strange, a little unpleasant measuring instrument (used for measuring the skull during the height of the colonial and social-Darwinist era?), which has been placed on top of the letter O, and a small text “Suohpan Error Manufacturing Co” which is found at the bottom of the optician’s board.

This poster was uploaded on 10 May 2013, after the debate on Pekka Sammallahti’s Facebook page had turned on the possible ratification of the ILO Convention no. 169. Far from calming down, the conversation was increasingly intensive, and each of Sammallahti’s “thoughts of the day”—of which there could be several every day—gathered a broad following and long comment threads ranging from about 20 to more than 200 comments. Besides Professor Sammallahti himself, one of the most active commentators was Mikko Kärnä, then the head of the Muncipality of Enontekiö. Risking simplification, whereas Sammalahti held that as an Indigenous people, the Sámi should have the right to define their collective identity by themselves, Kärnä—a Finnish politician known for vehement opposition to the Sámi Parliament and Sámi institutions in general—centred on three different positions. On the one hand, he suggested that there exist more Sámi than currently recognized by the Sámi Parliament, and that the ILO 169 cannot be ratified unless all those people who claim Sámi ancestry are included in Sámi Parliament’s electoral roll. On the other hand, he also suggests that the Sámi might not even be an Indigenous people in the sense understood in the ILO Convention no. 169, and therefore the ILO Convention no. 169 should not be ratified at all. The third position suggested that, in addition to the Sámi, there might be also other Indigenous peoples in Northern Finland that should be counted as such, in case the ILO Convention no. 169 concerning Indigenous peoples were to be ratified.

Each of these arguments was challenged, but Kärnä would always look for a riposte. Whenever he was cornered, the Municipality head would conclude that in order to resolve the questions in hand, the state should commission an objective “analysis of the circumstances” (olosuhdeanalyysi), whereby the status of the Sámi as an Indigenous people, and a number of issues that in his view were preventing the ratification of the Convention, could be examined in detail. For many others, however, this suggestion appeared as an attempt to distract and hinder the ratification process. Given the amount of research, reports and negotiations that the Finnish state has already commissioned in regard to Sámi rights, especially land rights, and the time spent on these (see Lehtola Citation2000, 135–192; Lehtola Citation2005; Pääkkönen Citation2008 100–111), the call for yet another study seemed akin to a “politics of distraction”, the main aim of which is to divert attention to concerns and cosmetic details which reflect the interests of the mainstream academy and society, rather than those of the Sámi (Minde Citation2008, 278). Moreover, given that the Finnish state currently claims to possess 90% of all land in the Sámi homeland area, the state is no neutral broker on this matter, but rather one of the main parties of interest.

On 8 May 2013, the debate on the political qualities of Kärnä’s suggestions grew increasingly animated, when Sammallahti posted a link to a text published in September 2011 on the website of the Finnish branch of the National Rifle Association (NRA Finland). The text, which appeared to lay bare the origins of the discourse on the “analysis of the circumstances”, was written by Jouni Kitti, a well-known figure in Sámi politics who has previously acted as a representative in the Sámi Parliament, but has, since then, become a passionate critic of Sámi institutions in Finland (Pääkkönen Citation2008, 250–251). In this text, Kitti argued vehemently against Sámi land rights in Northern Finland, and demanded an “analysis of the circumstances’, in terms identical to those presented by Mikko Kärnä.Footnote23 Although Kitti’s views might not have been surprising as such, many found his apparent affiliation with NRA, a US based lobby organization for gun rights and known for racist and ultra-nationalist attitudes, rather disconcerting. It was discovered that NRA Finland’s homepage presented a whole independent section of writings on the Sámi, all of them with Kitti as the author. This finding was tackled with a range of sentiments from bewilderment to a good dose of humour, and from thereon, much of the debate—which carried over to the next day—entailed also rather amused commentaries and gentlemanly jokes on Kärnä’s ideological forefathers and his potential links to a xenophobic gun rights organization.

Published on 10 May 2013, Suohpanterror’s poster depicting the letters o-l-o-s-u-h-d-e-a-n-a-l-y-y-s-i extended this joking mood to the visual realm. In this poster, Kärnä’s call for an “analysis of circumstances” seems to be equated with an obsession with, and insistence on, measurement. Together with the underlying text “Suohpan Error Manufacturing Co”, it stands as a visual portrayal of the “politics of distraction” which operates by framing and limiting attention to minute details and cosmetic surface, here in the form of a sight test and skull measurement. Interestingly, the fourth line of letters on the optician’s board—whether purposeful or not—forms the Sámi word eana, which means “land” in Northern Sámi. Here, eana could refer, for instance, to the ultimate, material interests behind calls for an “analysis of circumstances”, and to the matter being discussed in general—after all, among the most central aspects of the ILO Convention no. 169 are its stipulations regarding Indigenous Land Rights.

Accordingly, just like Liikon, also this poster appears in a somewhat different light for those who know its immediate context and who followed, perhaps even participated in, Sammallahti’s Facebook debates concerning this thematic. For this audience, the poster strengthens and extends the sensation of collective laughter that had already been experienced online: it brings subjects to laugh together, not only at the perceived contradictions and ulterior motives behind the rhetoric of an “analysis of circumstances”, but also at the person of Mikko Kärnä himself, a populist politician and a jack-in-the-box always ready to bounce back with the demand for an “analysis of circumstances”. In so doing, the poster performs bonds of togetherness and solidarity among political subjects who, by virtue of their shared knowledge, are able to identify a good amount of case-specific humour in an image which might otherwise look rather mysterious, even oppressive.

Both of the images pertaining to the Sámi spring that I have described above are therefore constitutive of online intimacies and a sense of a political community among those who know and who laugh together. Although the political we, especially in the last case, is constructed at the cost of the other who is being laughed at, it is worth remembering that here the relations of power and dominance between those who laugh, and the one being laughed at, are complex: although Kärnä might have stood rather alone in this particular online debate, he was not a solitary, private figure. Standing as the head of Enontekiö’s municipality (since then, he has become an MP at the Finnish Parliament), he spoke from the top of an institutional and structural colonial hierarchy, which especially the Sámi in Enontekiö have to face on a daily basis. In the Sámi homeland area, it is on the level of municipal politics that structural racism experienced by the Sámi tends to be most tangible, particularly within the municipalities of Inari and Enontekiö (Puuronen Citation2011, 111–67; Pääkkönen Citation2008, 246–51). Given the prevailing discursive environment in which speaking out in defence of Sámi rights can be highly consuming on a personal level, the opportunity to laugh together at a figure representing power and dominance on the local level can be collectively empowering and therapeutic, and hence conducive to a new sense of political community, togetherness and strength among those laughing.

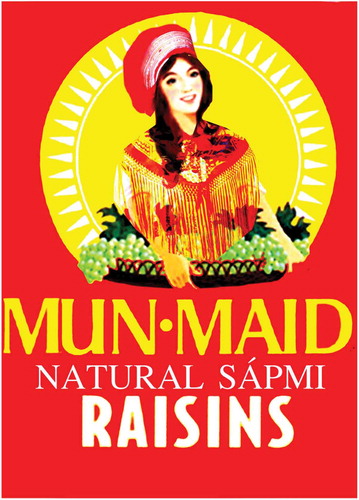

The last image that I will bring up here is Mun Maid, (), which was uploaded on Suohpanterror’s Facebook page on 12 May 2013. The poster is colourful and pleasing to the eye, a Sámi interpretation of the classic global brand, Sun Maid raisins. The beautiful maid holding a tray of grapes is dressed in Sámi clothes, and the text has been altered, so that instead of “Sun Maid: Natural California Raisins” the poster says “Mun Maid: Natural Sápmi Raisins”. There is really nothing that would stick in the eye: the Sámi woman’s hat and scarf suits the Californian maid perfectly, so well that it is almost hard to spot the difference from the original. In summary, the image appears as a particularly fine example of subvertisement, the most classic form of culture jamming which centres on the manipulation and subtle distortion of well-known global brands, logos and advertisement. Presumably, this is also the predominant way in which the image is interpreted and consumed, whenever Suohpanterror’s images are displayed in galleries, museums and other exhibition spaces.

However, also this image addresses people very differently depending on their cultural literacy and background knowledge, constituting audiences on various levels. This time, language is the key. By replacing the first letter in “Sun” with a capital M, the original brand name is transformed into a short Sámi sentence: in Northern Sámi, “Mun maid” means “Me too”. Subsequently, the text joins the poster with the debates that I have examined here, becoming a rather gentle parody of the discourse of the “non-status Sámi” advanced by groups such as the VGDS. The maid posing as an original Sámi girl is no longer unambiguously what she claims to be: the scarf, the hat and the text (“Natural Sápmi raisins”) are political statements, there in order to prove to oneself and the others that “I am a Sámi too”.

Of course, as with any image, this is not the only interpretation available. The poster can be read also in more general terms, for instance in relation to Indigenous subalternity and the colonial gaze. By giving Sámi content to a well-known global brand, the poster inserts the Sámi in a global economy of images and representation, insisting on their visibility and presence, as if saying: “We too exist, we are still here”. However, such an interpretation might suggest itself only for those who understand Northern Sámi, but are unaware of Sámi politics in Finland. Moreover, those who continued to follow the debates on Pekka Sammallahti’s wall in July 2013 know that also this poster was issued in response to the discussions there. The poster was released at a moment when the debate turned increasingly around the politics of the dress and around the authenticity of the clothing that those campaigning for the extension of the legal Sámi definition have produced in support of the argument that they, too, are Sámi. Against this background, the poster is hardly about natural Sápmi raisins being inserted in the global flow of consumerist aesthetics: it is a humorous, witty portrayal of a specific group presenting themselves as “non-status Sámi”, designed to bring laughter to those who know both the language and the context.

Speaking about the present

Clearly, the “Sámi Spring” provided the background for much of Suohpanterror’s work in 2013. This small social media uprising carried on well beyond the summer, slowing down in July (summer holidays) but picking up again in August and occasionally during the following months. It would be impossible to give an exact date to its end. One of its tangible results was the general Statement on Sámi Definition, which SSN (Suoma Sámi Nuorat), the Sámi Youth Organization in Finland, published on their website in May 2013.Footnote24 The archive of visual commentaries produced by Suohpanterror may well be considered as another. Together, these social (media) phenomena are supporting the crystallization of a new, more confident political Sámi voice in Finland.

Exploring Suohpanterror’s work in relation to Sámi audiences, which in this article meant studying the relations between Suohpanterror and the “Sámi Spring”, draws attention also to temporal aspects in the group’s work. First, although most of the posters appear to illustrate Sámi grievances and experiences on a very general level, placing them in conversation with their immediate background reveals a body of online art which responds very fast to specific events, developments and news, on a daily basis and as they emerge. Secondly, what this study has highlighted is the centrality of current experience to Suohpanterror’s decolonial project: instead of simply transferring “historical injustice” into contemporary media images using the tools of “Western entertainment propaganda” (Tamminen Citation2012), the injustice addressed by Suohpanterror relates, above all, to the now: to the colonial present which is taking place in Finland and Scandinavia today.

As I was writing this article, the group’s name seemed to pop up increasingly and everywhere (or was I just imagining?). Suohpanterror is becoming really popular in Finland, and probably also abroad. Having said that, it is conspicuous that so far, the surge of interest in Suohpanterror’s work has not been coupled with a similar interest in the themes and issues that the group seeks to speak about: Suohpanterror’s national breakthrough has taken place at the very same moment at which the Finnish state’s policies towards the Sámi have taken on increasingly hard tones, and even many of those rights that have already existed have been rolled back, without many even noticing.Footnote25 As such, one might be right to ask, what is the political value and impact of Suohpanterror’s art when it is detached from the original context, and consumed by large audiences in private galleries and world-famous museums? Are these images still politically meaningful and decolonizing? Or is Suohpanterror facing the threat of becoming mere entertainment—an exotic, decorative element which simply adds Sámi flavour to the multicultural neoliberal society where cultural difference is accepted on the surface only, and seen as highly marketable? Do people who consume Suohpanterror’s images get the political message at all, and do they get it right?

Although captivating for a social scientist, in practice these might not be questions worth pondering too much, or at least they do not appear too central in Suohpanterror’s own ideology: as the artist-mastermind points out, the question whether people understand the message is not so important, as long as they like the images: “All ‘likes’ increase publicity, and publicity is essential for generating a credible Sámi voice in Finland. When you are ‘cool’ and people like you, they are open to listening to the things you have to say”.Footnote26 Understood in this sense, Suohpanterror’s decolonial politics vis-a-vis the dominant society is not limited to the messages that they convey. Rather, their politics is about their ability to become a discourse of their own, and to fill the (Finnish) public space with new Sámi substance, even noise, so that when other Sámi speak, they will be noticed, and listened to more seriously.

When the focus is shifted on the level of Sámi audiences, however, there are no doubts about the political value of Suohpanterror’s work. On this level, the messages are clear, specific, and constitutive of a new sense of political community among people who are able to read these images in the same way, due to strong local knowledge and/or a shared cultural and political background. With the cover of anonymity, Suohpanterror has found a way to articulate a new Sámi voice that is provocative and bold, yet very easy to contribute to, or act in solidarity with, through online liking, sharing, and comments. These online activities can be politically empowering: even just seeing that many others like the images too, and share them, is encouraging in itself. Even more importantly, these online activities can contribute to the formation of a shared political subjectivity and sense of community among people who share them and laugh at these images, knowing that there are others, too, who “get it right” and in the same way, and who share these views. In a world in which the practices of colonial silencing and marginalisation take ever new forms and where acting politically has become an increasingly complex endeavour especially for Indigenous people, this is no small achievement.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Laura Junka-Aikio

Laura Junka-Aikio is a researcher at the Giellagas Institute for Sámi Studies, University of Oulu, Finland. Her work, which has spanned from Palestine and the Middle East to the Indigenous Sámi in Northern Scandinavia, is concerned mainly with the politics of knowledge, the relationships between knowledge and social change, and with questions of subalternity in colonial and Indigenous contexts. Junka-Aikio is the author of Late Modern Palestine: The subject and representation of the second intifada (Routledge, 2016), a co-editor of the Cultural Studies special issue “Cultural Studies of Extraction” (2017). She is currently working as part of research project “The Societal Dimensions of Sámi Research”, which is based at the UiT Arctic University of Norway.

Notes

1. am grateful for a number of people who have offered their support. In particular, I would like to thank the artist-mastermind behind Suohpanterror’s poster art, who still prefers to remain anonymous, for comments and for granting me the right to use the pictures included in this article: Thank you also to Antti Aikio, Saara Tervaniemi, Veli-Pekka Lehtola, Pekka Sammallahti and Pirita Näkkäläjärvi, each of whom has contributed to this article through private exchanges and comments to earlier versions of this article. Finally, thank you for the editors of this special issue, Sigrid Lien and Hilde Nielssen, as well as for the two anoymous reviewers for their brilliant comments and revision suggestions.

2. The discourse of the Sámi as a “peace-loving people” coexists with an equally persistent discourse of “quarrelling natives”, always envious of one another. Although this might seem contradictory, the pattern is familiar to colonial discourses in general, where mutually opposing characteristics—such as depicting the oriental other as both aggressive and barbarian and passive and childlike—are frequently combined (Bhabha Citation1994; Said Citation2003).

3. Personal email communication with the artist-mastermind, 23 March 2017.

4. More recently, the group has also published a website, found at http://suohpanterror.com.

5. The documentary is available for download with English subtitles via Youtube at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_0Bzjw7CLw0 [accessed 10 March 2017].

6. I thank Saara Tervaniemi for highlighting this point.

7. John Pilger, “The War You Don’t See” (2010).

8. All translations from Finnish or Northern Sámi to English are my own.

10. For instance, in 2014, Suohpanterror’s posters were showcased as part of the Finnish Artist Association’s Viimeinen taiteilijat -annual exhibition in Helsinki and toured around Scandinavia and Germany as part of the Sámi Contemporary,10 an international curated exhibition showcasing the work of contemporary Sámi artists. In 2015, Suohpanterror took part in Demonstrating Minds, an international exhibition at the Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art in Helsinki, and their work was bought in the Museum’s permanent art collection. An updated list of exhibition appearances is available on Suohapnterror’s recently opened website, http://suohpanterror.com/?page_id=22.

11. http://www.france.fi/uncategorized/lapland-tracing-the-sami-of-finland-in-paris-32017/?lang=en .

12. The debate took place in Facebook in March 2017.

15. The finished piece (in Finnish), “Muistio saamelaismääritelmästä”, (Sammallahti Citation2013) is downloadable at the Sámi Parliament’s website, http://www.samediggi.fi/index.php?option=com_docman&task=cat_view&gid=224&Itemid=10&mosmsg=Yrit%E4t+p%E4%E4st%E4+sis%E4%E4n+ei+hyv%E4ksytyst%E4+verkko-osoitteesta.+%28www.google.fi%29.

16. Also I followed (and sometimes participated in) these debates, largely along the lines present in Junka-Aikio (Citation2016). While I am not Sámi myself, the issues in question have become familiar to me after I met my husband who is a Sámi and a legal scholar specialised in Sámi rights.

17. According to Sammallahti, he received more than 200 new Facebook friendship invitations during the most intensive period, primarily from young Sámi people. Although most did not want to participate in the debate publicly and with their own face, many sent Sammallahti messages of support in private. Personal e-mail communication with Pekka Sammallahti, 30 February 2017.

18. Today, the same group is known as the North American Sami Searvi. https://www.facebook.com/groups/206865919326820/.

19. See, for instance, “Sammallahti: Vearrolappalaštearbma muitala ealáhusain ii etnisitehtas” Yle Sápmi (online) 25 April 2013, available at: http://yle.fi/uutiset/osasto/sapmi/sammallahti_vearrolappalastearbma_muitala_ealahusain_ii_etnisitehtas/6622177; Saijets (2013) “Emeritusprofessor: Buot gávtteláganat eai leat sápmelaččaid čeárdabiktasat”. Yle Sápmi (online), 20 June 2013, available at: http://yle.fi/uutiset/osasto/sapmi/emeritusprofessor_buot_gavttelaganat_eai_leat_sapmelaccaid_ceardabiktasat/6696652 [accessed 20 March 2017]; Guttorm and Länsman (2013) “Saarikivi: Soađegili jápmán sámegiela sáhtášii váldit atnui”. Yle Sápmi (online), 3 July 2013. Available at: http://yle.fi/uutiset/osasto/sapmi/saarikivi_soaegili_japman_samegiela_sahtasii_valdit_atnui/6698759.

20. According to the artist behind the image, he removed it because he didn’t consider it a proper poster. E-mail communication with the artist, 1 March 2017.

22. As an example, one might look at “Inarin kansalaiskanava” (“Inari citizens’ channel”) a community page where highly tedious speech on the Sámi is used frequently. https://www.facebook.com/groups/139277979453532/.

23. The article built, for instance, on the populist idea that instead of being Indigenous, many reindeer herding Sámi in Finland are immigrants who have arrived from Sweden and Norway superseding the “Lapps”, the actual Indigenous people of Northern Finland. Antti Aikio deconstructs this claim from the perspective of Nordic legal history in Aikio (Citation2009, Citation2010).

24. The document was developed largely through the collective debates in Facebook, and encouraged by them. Available in Northern Sámi, at http://www.ssn.fi/se/2013/05/suoma-sami-nuoraid-cealkamus-sapmelasmerostallamis/ and in Finnish, at http://www.ssn.fi/2013/05/suomen-saamelaisnuorten-lausunto-saamelaismaaritelmasta/ [Accessed 23 March 2017].

25. This was the case, for instance, in 2015 when, following the active campaigns on behalf of the “non-status Sámi”, the Finnish Supreme Court ruled that nearly a hundred persons, whom the Sámi Parliament’s electoral committee considered as ethnic Finns, would be included in the Sámi Parliament’s electoral roll against the will of the Sámi Parliament in a gross violation of the Sámi right for self-determination; Or, when the new Forest Law, from which earlier references to Sámi rights had been removed, was accepted by the Parliament in 2016; or when the Parliament accepted the new agreement concerning fishing rights at the Tana River in March 2017, cancelling, in practice, the rights of the local people—largely Sámi—in favour of holiday makers fishing for entertainment.

26. Personal email conversation with the artist-mastermind, 1 March 2017.

References

- Ahmed, S. 2013. “Making Feminist Points.” feministkilljoys -blog, September 11. Accessed 28 September 2017. https://feministkilljoys.com/2013/09/11/making-feminist-points/

- Aikio, A. 2009. “Saamelaiset - Maahanmuuttajiako? Suomen Saamelaisiksi Valtionrajojen Ristivedossa.” A Master’s thesis for the University of Lapland’s Faculty of Law, University of Lapland, Rovaniemi.

- Aikio, A. 2010. “Suomen Saamelaisten Historiallinen Erilliskehitys.” In Kysymyksiä Saamelaisten Oikeusasemasta, edited by K. Kokko. Rovaniemi: University of Lapland Press.

- Aikio, A., and M. Åhren. 2014. “A Reply To Calls For An Extension Of The Definition Of Sámi In Finland.” Arctic Review On Law And Politics 5 (1): 1–14.

- Avaskari, A. 2016. ““Itsenäisyyspäivän Juhlapuhe” (Independence Day Speech) 6 December 2016.” Accessed 10 March 2017. http://jounikitti.fi/suomi/maaoikeudet/avaskarinpuhe.html

- Bhabha, H. 1994. The Location of Culture. London: Routledge.

- Cammaerts, B. 2007. “Jamming The Political: Beyond Counter-hegemonic Practices.” Continuum: Journal Of Media And Cultural Studies 21 (1): 71–90. doi:10.1080/10304310601103992.

- Gudynas, E. 2013. “Transitions to Post-Extractivism: Directions, Options, Areas of Action.” In Beyond Development: Alternative Visions from Latin America, edited by M. Lang and D. Mokrani, 165–188. Quito: Rosa Luxemburg Foundation and Transnational Institute.

- Heikkilä, L. 2006. Reindeer Talk: Sámi Reindeer Herding and Nature Management. Rovaniemi: Lapland University Press. Accessed 6 July 2017. https://lauda.ulapland.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/61740/Lydia_Heikkilä_väitöskirja.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- Hirvonen, S. 2001. “Ylälapin mahdoton yhtälö: Lappalaisidentiteetti poliittisena strategiana ja Lapin kansan rooli vallankäyttäjänä.” Master’s thesis, University of Jyväskylä. Accessed 23 March 2017. https://jyx.jyu.fi/dspace/handle/123456789/12644

- Ikonen, I. 2011. ““Irvikuva, entäs sitten?” - Lapin Kansan ja Helsingin Sanomien luoma saamelaiskuva vuoden 2011 sanomalehtiteksteissä.” A Master’s Thesis, Giellagas Institute for Sámi Studies, University of Oulu. Accessed 13 March 2017. http://www.oulu.fi/sites/default/files/content/Giellagas_Ikonen_gradu.pdf

- Joona, T. 2012. “ILO Convention No. 169 in a Nordic Context with Comparative Analysis: An Interdisciplinary Approach.” Juridica Lapponica 37. Rovaniemi: University of Lapland Press.

- Junka-Aikio, L. 2016. “Can the Sámi Speak Now? Deconstructive Research Ethos and the Debate on Who Is a Sámi in Finland.” Cultural Studies 30 (2): 205–233. doi:10.1080/09502386.2014.978803.

- Lehtola, V.-P. 1994. Saamelainen Evakko: Rauhan Kansa Sodan Jaloissa. Inari: Kustannus-puntsi.

- Lehtola, V.-P. 2000. Nickul: Rauhan Mies, Rauhan Kansa. Inari: Kustannus-puntsi.

- Lehtola, V.-P. 2005. Saamelaisten Parlamentti. Suomen Saamelaisvaltuuskunta 1975-1993 Ja Saamelaiskäräjät 1996-2003. Inari: Saamelaiskäräjät.

- Lehtola, V.-P. 2015. Saamelaiskiista. Helsinki: Into.

- Magga, A.-M. 2012. “Pedot – monimuotoisen luonnon osa vai saamelaisen poronhoidon voimattomuuden symboli? Petokäsitykset ja diskurssit saamelaisten poronhoitajien ja suurpetojen suojelua ajavan diskurssikoalition välisessä petokiistassa vuosina 2010-2011.” Master’s Thesis (Pro gradu -tutkielma), Giellagas Institute, University of Oulu. Accessed 6 July 2017. http://docplayer.fi/3768751-Pedot-monimuotoisen-luonnon-osa-vai-saamelaisen-poronhoidon-voimattomuuden-symboli.html

- Mignolo, W. D., and A. Escobar. 2013. Globalization and the Decolonial Option. London: Routledge.

- Minde, H., ed. 2008. Indigenous Peoples: Self-Determination, Knowledge, Indigeneit. Delft: Eburon Academic Publishers.

- Näkkäläjärvi, K. 2010. “Klemetti Näkkäläjärven Puhe Saamelaisten Kansallispäivän Juhlissa Inarissa 6.12.2010.” Accessed 6 December 2017. http://www.samediggi.fi/index.php?option=com_docman&task=cat_view&gid=175&dir=DESC&order=date&Itemid=99999999&limit=15&limitstart=15

- Näkkäläjärvi, P. 2014. “Suohpanterror Tukee Utsjoen Kaivosvastaista Liikettä Katutaidenäyttelyllä.” Yle Sapmi (online), September 15. Accessed 10 February 2017. http://yle.fi/uutiset/osasto/sapmi/suohpanterror_tukee_utsjoen_kaivosvastaista_liiketta_katutaidenayttelylla/7471166

- Olsen, K. 2004. “The Tourist Construction of The”Emblematic” Sámi.” In Creating Diversities: Folklore, Religion and the Politics of Heritage, edited by A. Siikala, B. Klein, and S. R. Mathisen, 292–305. Helsinki: SKS.

- Pääkkönen, E. 2008. Saamelainen Etnisyys Ja Pohjoinen Paikallisuus: Saamelaisten Etninen Mobilisaatio Ja Paikallisperustainen Vastaliike. Rovaniemi: Lapland University Press.

- PietikäInen, S. 2000. “Discourses of differentiation. Ethnic representations in newspaper texts.” A PhD Thesis, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä.

- Puuronen, V. 2011. Rasistinen Suomi. Helsinki: Gaudeamus.

- Said, E. 2003. Orientalism. London: Penguin Books.

- Sammallahti, P. 2013. “Muistio Saamalaismääritelmästä.” Accessed 15 March 2017. http://www.samediggi.fi/index.php?option=com_docman&task=cat_view&gid=224&Itemid=10&mosmsg=Yrit%E4t+p%E4%E4st%E4+sis%E4%E4n+ei+hyv%E4ksytyst%E4+verkko-osoitteesta.+%28www.google.fi%29

- Sarivaara, E. 2012. Statuksettomat Saamelaiset: Paikantumisia Saamelaisuuden Rajoilla. Dieđut, Guovdageaidnu: Sámi Allaskuvla.

- Sarivaara, E., K. Määttä, and S. Uusiautti. 2013a. “Who Is Indigenous? Definitions of Indigeneity.” European Scientific Journal 369–378. December 2013 Special Edition no. 1.

- Sarivaara, E., S. Uusiautti, and K. Määttä. 2013b. “The Position and Identification of the Non-Status Sámi in the Marginal of Indigeneity.” Global Journal of Social Science Research 13: 1 (a).

- Särmä, S. 2014. “Hömppäfeminismiä kollaasin keinoin: Omaelämänkerrallisia seikkailuja maailmanpolitiikan tutkimuksen marginaalissa.” In Maailmanpolitiikan marginaalit: tieto, valta, kritiikki, Edited by Bordering Actors research collective (Tiina Seppälä, Hanna Laako and Laura Junka-Aikio). Kosmopolis, Vol 44: 3–4, 112–125.

- Särmä, S. 2015. “Collage: And Art-Inspired Methodology for Studying Laughter in World Politics.” E-International Relations, June 6. Accessed 14 March 2017. http://www.e-ir.info/2015/06/06/collage-an-art-inspired-methodology-for-studying-laughter-in-world-politics/Edit

- Särmä, S. 2016. “Collaging Internet Parody Images – An Art-inspired Methodology For Studying Visual World Politics.” In Understanding Popular Culture And World Politics In The Digital Age, edited by, 175–188. London: Routledge.

- SARV. 2016. “Kritiikin Kannukset Suohpanterrorille.” A press release, April 26. Accessed 9 February 2017. http://www.sarv.fi/2010/index.php?p=kritiikin-kannukset-taiteilijaryhma-suohpanterrorille

- Schools for Chiapas. 2014. “An Examination of the History and Use of Masks and Why the Zapatistas Cover Their Faces.” Accessed 10 March 2017. http://schoolsforchiapas.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Whats-behind-the-mask_.pdf

- Tamminen, J. 2012. “Suomi Saamelaisille.” Voima, 8/2012. Accessed 23 March 2017. http://voima.fi/blog/arkisto-voima/suomi-saamelaisille/

- Tamminen, J. 2014. “Arktinen Terrori.” Voima, 4/2014. Accessed 10 February 2017. http://voima.fi/blog/arkisto-voima/arktinen-terrori/

- Tuck, E., and W. Yang. 2012. “Decolonization Is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education, Society 1 (1). Accessed 23 March 2017. http://decolonization.org/index.php/des/article/view/18630

- Tuulentie, S. 2001. MeidäN VäHemmistöMme – ValtaväEstöN Retoriikat Saamelaisten Oikeuksista KäYdyissä Keskusteluissa. Helsinki: Hakapaino oy.

- Valkonen, J., S. Valkonen, and T. Koivurova. 2017. “Groupism and the politics of indigeneity: A case study on the Sámi debate in Finland.” Ethnicities, 17 (4). DOI: 10.1177/1468796816654175.

- Vartiainen, M. 2008. “Luonnonvarasuvereniteetti kansainvälisessä oikeudessa: Paikallisen väestön oikeudet alueensa luonnonvaroihin Ylä-Lapin luonnonvarakonfliktissa.” A Licentiate Thesis, Faculty of Law, University of Lapland.

- West, H. 2017. “Gallerista Rábmo Suohpanterrora - “Ođđalágan Vuohki Dahkat Politihkalaš Dáidaga.” Yle Sápmi (online), March 17. Accessed 18 March 2017. http://yle.fi/uutiset/osasto/sapmi/gallerista_rabmo_suohpanterrora__oalagan_vuohki_dahkat_politihkalas_daidaga/9516131