ABSTRACT

This article concerns how nostalgic photographs are circulated in new contexts such as packaging and social media. The purpose is to explore the ontological transformations of photographs in the contemporary image ecology, blurring the categories “analogue” and “digital”. What new meanings and materiality can old photographs acquire when for instance put on packages that are used, thrown away, recycled and sometimes upcycled? The crisp producer Tyrrells is used as a case study, since quirky old photographs is a vital part of their packaging design, as well as on their website and social media channels. The company makes use of Monty Python-style collages to conjure up the English eccentric and their marketing communication is characterised by ironic nostalgia. Although the package is a throw away object, it can be upcycled by craft makers and sold at online marketplaces, which means that the photographs continue their circulation, from analogue film and cameras, to press agencies, to the printed page, to stock image databases on the Internet, to crisp packages and birthday cards, to Facebook and Instagram, to crafted bags in digital marketplaces and so forth. The package has a twofold appearance, as a physical object and as a virtual object on the web, both of which constitute the other. The ontology of the photograph has changed, since the different forms of appearance can no longer be disentangled from each other and join hands in the trajectory of the photograph in the contemporary image ecology.

In 1969, in the third episode of the first season of the British TV series Monty Pythons Flying Circus, an animation appears that contains a mock commercial that encourages the audience to upgrade their past with the help of old photographs. The animation shows a man sitting in a room that is gradually filled up with early twentieth century family photos, from which his new “ancestors” come to life and invade his home. The voice over says:

Tired of that dreary, boring life you lead? Then purchase a past. Thousands of people have lead far more interesting lives than you will ever lead. And they will undoubtedly continue to lead interesting lives whereas you just assuredly will not. But now, for the very first time, bits of their lives are being made available for purchase, for only 15 shillings. Dullards like yourself can obtain beautifully-framed photographs of other peoples’ lives. Hang them in your den, stand them on your desk, or next to your bed. Pretend they are pictures of your past.Footnote1

Translated into scholarly language, the message of the animation resounds in Russell Belk’s article “Possessions and the sense of past” written 20 years later:

As more of our lives are given over to mass production, mass media, mass marketing, and mass consumption, it should come as no surprise that the past is also becoming a commodity that is produced and consumed on a mass scale with standardization, pre-packaging, and advertising.Footnote2

Belk stresses the importance of snapshots and family photographs for the creation of a sense of past and for the evocation of nostalgic memories. However, he states that the photographs have considerably less value for other people, for whom they would only have a general historic interest. Although Belk’s main tenets are still valid, the image ecology has undergone great changes and made the Monty Python commercial seem nearly prophetic. Snapshots are collected by art dealers and exhibited by art museums.Footnote3 Vintage photographs are bought and sold on online marketplaces like eBay and displayed in collections on image sharing sites like Flickr and Pinterest.Footnote4 Old photographs, amateur as well as professional, are circulated in new contexts such as packaging and social media and used in marketing of diverse products. Consumption at large is not as pre-packaged and mass-scaled as when Belk wrote his article, and there are several new positions people can take in their role as consumers. The circulation of images occurs within the global cultural industry, where, according to Scott Lash and Celia Lury, media has become things and meaning operational, and not only a question of interpretation. Computer games is one case in point.Footnote5 Focussing on the visual part of the culture industry, I have chosen the concept image ecology, due to its broad perspective, to designate the context of circulation in this article. First used by Susan Sontag, the concept has been developed by Sunil Manghani and concerns the production, meaning and consumption of images. He wants to stress the complexity of the image and “to understand image histories, connections, cultures, and adaptations.”Footnote6 The image ecology involves economic as well as social aspects. With the help of the concept social biographies, Elisabeth Edwards has directed attention to the materiality and objecthood of photographs.Footnote7

The purpose of this article is to explore the ontological transformations of photographs in the contemporary image ecology, blurring the categories “analogue” and “digital”. What new meanings and materiality can old photographs acquire when for instance put on packages that are used, thrown away, recycled and sometimes upcycled?

The case study of the article will be Tyrrells, a crisp producer founded in 2002, based in Herefordshire where the potatoes are grown and refined into an “artisan delicacy.”Footnote8 Their marketing is to a large extent based on Internet communication and packaging design. Old stock photographs, mainly from the first half of the twentieth century, appear on the packages, on the company web site as well as on the Facebook page. A selection of these crisp bags and their photographs will be discussed with regard to their motifs, function and context.Footnote9

Reflective and ironic nostalgia

The images on Tyrrells’ crisp packages can be labelled nostalgic, but a particular brand of nostalgia, self-aware and somewhat self-mocking, in contrast to the originally serious meaning of the concept. Nostalgia was in the 17th century seen as a serious condition of homesickness,Footnote10 but the term has since come to designate a general feeling of longing, and has moved from the spatial dimension toward the temporal. Nostalgia has become a longing for the past rather than for distant places. Several typologies of nostalgia have been suggested: for instance, Fred Davis differentiates between private and collective nostalgia,Footnote11 whereas Svetlana Boym distinguishes between restorative and reflective nostalgia.Footnote12 These typologies are not totally incompatible; Davis’ collective nostalgia and Boym’s restorative nostalgia both pertain to national revivals and national symbols such as flags. Boym’s reflective nostalgia resembles Davis’ private nostalgia as it “is oriented toward an individual narrative”.Footnote13 She further describes reflective nostalgia as being aware of itself as nostalgia and, in contrast to restorative nostalgia that takes itself very seriously, as being capable of irony and humour.

Although nostalgia is prevalent in contemporary marketing, this is not a new phenomenon.Footnote14 In the late nineteenth century marketers created “the commodified authentic”, putting the dream of the British pastoral past within reach for consumers, yet bestowing products with a non-commercial aura.Footnote15 Writing from a critical theory perspective, S.D. Chrostowska regards nostalgia as the commodification of memories and as dependent on borrowed or second hand memories.Footnote16 This brings us back to the Monty Python commercial, where the photographs fulfil the role of such vicarious memories. As much of Monty Python’s humour, it is steeped in irony. In her essay “Irony, Nostalgia and the Postmodern”, Linda Hutcheon asks herself whether it is possible for the same cultural artefact to be interpreted as either nostalgic or ironic, or as both. She concludes that irony and nostalgia have been connected in the postmodern and that both irony and nostalgia offer ways of responding to cultural artefacts instead of being inherent in the objects themselves. “The ironizing of nostalgia” is a way of creating a distance for reflective thought.Footnote17 The mixing of nostalgia and irony, both through textual and visual means, characterizes Tyrrells’ marketing, as I will show below.

Tyrrells’ images: the glue that unites packaging, website and social media

Photographs are commonly used on packages to show the product itself, or its origin, or how it should be served. When people are shown, it might be a group of happy people enjoying the product together. When a company uses old photographs on their packages, it is often sepia toned photographs of the founder and his/hers family which connote the long traditions of the business. An example is the Israeli cookie producer Elsa’s Story, that features the fictional figure Elsa as the founder and uses the slogan “taste, enjoy, remember” under old family photographs where Elsa has been marked with a red circle.Footnote18 This can be seen as an example of what Chrostowska referred to as the borrowing of second hand memories.

Tyrrells has opted for a different strategy—instead of identifying the company with a specific character, they have made the old, quirky photograph their hallmark, evoking a general nostalgia for the good old days when food production was small scale and craft based (). The English and especially the English eccentric is the all-pervading theme of the imagery used by the company.Footnote19 This is evident not least in the communication with consumers revolving around images.

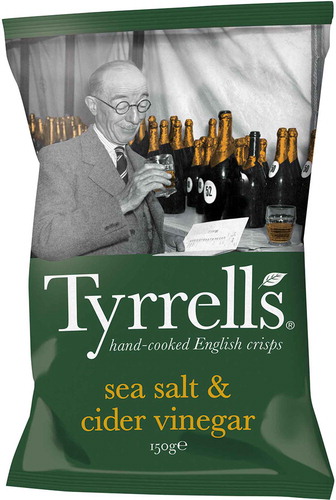

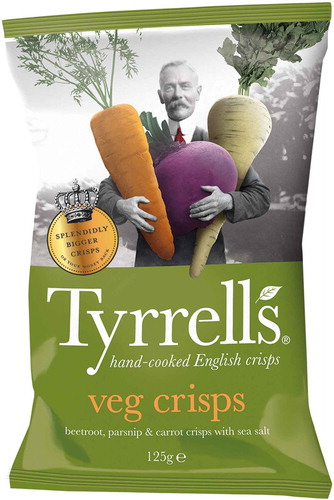

The photographs on Tyrrells’ packages occupy a central position by covering the upper half of the front side. A few examples of motifs are young girls doing handstands on the beach in the 1930s, respectable ladies in hats and coats in front of price winning cheese, an old man tasting cider in the 1940s, a fire engine turning out in the beginning of the nineteenth century, a woman collecting eggs from a flock of hens during the second world war, and a woman in a sun chair being kissed by a donkey in the 1920s. What they have in common is that they are often humorous and light-hearted and they always connect to the flavour in the package. They usually have an uncomplicated composition with the main subject placed in the centre of the picture and with a clear figure/ground contrast, which make the images easy to perceive for a shopper walking down a supermarket aisle.

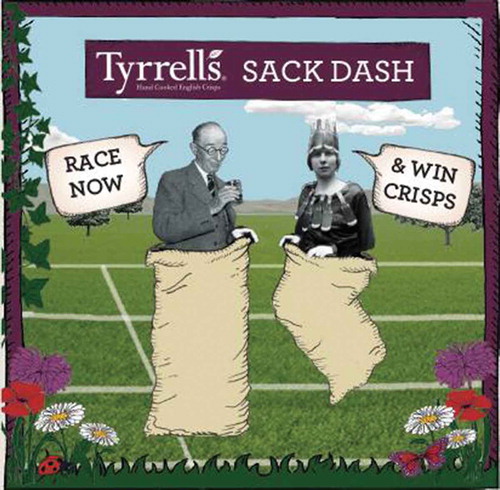

Several of the photographs used by Tyrrells have an origin in British picture agencies like Hulton archives, Fox photos, and Topical press agency, all of which are now part of Getty images.Footnote20 Very scarce information is to be found there, and I have not been able to reconstruct the social biographies of the photographs. In her article on stock photography and advertising in 1930s Britain, Helen Wilkinson shows that tracing the history of such images and their previous use is difficult, and in most cases impossible. Many of the stock photographs had a long shelf-life and were used over several decades. The pictures were often seen as raw material for an advertisement and were usually cropped, retouched or altered in some other way.Footnote21 This is a practice also in use at Tyrrells, where photographs serve as a basis for Monty Python-style collages and animations. Figures from the photographs have been cut out and function among other things as characters in the game Sack Dash that until 2015 could be played on the website. When you start a game, you pick a character such as Cecil “Sweet Chilli” Choddle or Archie “Cider” Sodhampton, whose nick-names are the names of the flavours of crisps ().

The website functions mainly as a catalogue, a bulletin board and an information repository, where customers can find all sorts of information about the company and its products. Different flavours were until 2017 displayed in the form of bags hanging from washing lines, attached with clothes pegs. Together the packages form a collection, held together by a similar design. The visual metaphor of the washing line adds to the materiality of the packages in the web context.Footnote22

In contrast to the website, the Facebook page is time oriented like a blog, with the last post appearing at the top. Staff from Tyrrells interact with visitors and publish material that can spur comments and conversations. Here, like on the website, Tyrrells publishes calls for competitions, but also pictures of current marketing events, enticing pictures of potatoes and serving suggestions, funny pictures sent in by customers, and current pictures of tennis players, politicians and royalties. The latter images are often enhanced with a package of crisps, placed there with the help of Photoshop. In addition, the pictures from the packages are posted here too, often in their original version without alterations. Tyrrells also has a Twitter account that frequently mirrors and links to the Facebook page.

In this way, the photographs and their characters are constantly being repeated: first they appear on the packages, then on representations of the packages on the website and as cut-out figures in games, then again as pictures posted on the Facebook timeline and on Twitter. Especially in this last context, the old photographs become current pictures that could have been shot today. Here they are independent photographs to be viewed detached from the graphic design of the package. The Facebook interface constitutes another visual context for the photographs, but since Facebook is such a pervasive application within social media, the interface becomes somehow transparent. The written text now accompanying the photographs is not the copy on the packages or on the website, but comments from Facebook members. Tyrrells’ staff often invites the visitors to a come up with caption for the image, which sometimes generate a chain reaction of comments.Footnote23 Through this procedure, the images become impressed in the memory of the consumers and will make them notice and recognize the packages in the shop.

Common themes and characteristics of the images

Instead of using pictures of one specific brand character or pictures of the founders of the company, Tyrrells uses a whole gallery of characters from the past, previously unrelated to the company, but now put to the service of promoting Tyrrells’ brand identity. It is reasonable to assume that the images have been chosen with the aim of attracting attention, which is achieved by characters that meet the gaze of the beholder or perform funny actions. The original images are cropped so that the human figure becomes the most prominent element of the picture.

I will briefly highlight five examples of photographs that can be regarded as representative. When I started this study in 2012, the photographs were in black and white. In 2015, colour was added to some elements in the images, creating an effect like Instagram Splash of colour. On the package of Sea salt & cider vinegar (), the photograph shows a man tasting cider in a tent with shelves full of cider bottles. He seems slightly intoxicated, which gives the image a humorous touch.Footnote24 Veg crisps () shows a man holding three oversized vegetables: a carrot, a beetroot and a parsnip. It is a collage which shows the ingredients for the product and the producer. On the package of Mature cheddar & chive () three ladies are standing in front of a pile of cheese, dressed in hats and fur collar coats. The word “mature” refers supposedly to the age of the women as well as the cheese.Footnote25 English barbecue () shows spectators at a polo match in wicker chairs with blankets over their laps, sharing umbrellas in the rain.Footnote26 The rainy English weather is an important national symbol; the cover of the book Watching the English: The Hidden Rules of English Behaviour depicts a similar scene.Footnote27 The package of Lightly sea salted () sports a photograph of young women doing handstand on a beach. This is a dynamic image on the theme of the British seaside.Footnote28

Figure 2. A game that could be played on Tyrrells’ website, designed in a pythonesque style. The characters portrayed are Archie “Cider” Sodhampton and Wendy “Worcester” Wigglethope.

By the selection of the five examples above, I have wished to point to some recurring themes. Leisure activities is one such theme, which is in line with the type of product; snacks are typically consumed in your spare time and in the company of friends. Another theme is personalities. Several of the people occurring in the images are ordinary people, who could have been your grandparents or your great-grandparents. The people portrayed are of all ages, but women dominate. The third theme is female beauty. Representing women in decorative roles is common in advertising.Footnote29 In the photo archives used by Tyrrells there are plenty of staged images depicting beautiful young women sunbathing or playing on the beach.

The common denominator for all the images used on Tyrrells’ packages is Englishness and humour. In some instances, the humour may well have been intended when the photographs were shot, in others it might be an effect of the distance in time and the displacement of context. For the English, humour is the “default mode” which permeates every conversation among them. Humour, and especially irony, is seen as a national trait, as a discipline in which they excel.Footnote30 There is probably no better representative of eccentric English humour than the Monty Python group.Footnote31 Terry Gilliam’s used old photographs in a way that made them seem funny regardless of their original purpose and context. The pythonesque collages make Tyrrells’ humorous approach extra clear (see ) and the company also applies the collage style when making fun of a marketing genre, the celebrity endorsement.Footnote32 In a photo on Tyrrells’ Facebook page of Andy Murray serving during Wimbledon 2013, the tennis ball has been replaced with a pack of crisps. Another photo shows the queen performing one of her official duties with a pack of crisps tucked in her handbag.

Filter nostalgia and user generated content

An important part of the contemporary image ecology is played by image sharing sites, where people can collect and organize images on different subjects and themes. One such site is Pinterest, where old images are often seen alongside new ones, but sometimes it can be hard to determine whether it is an old picture or a picture that has been made to look old. A prominent feature of another popular photo sharing service, Instagram, is the filters that will provide your mobile phone pictures with a patina. The vintage effects include the square format of the Kodak Instamatic and Polaroid cameras, color tinting and border formats reminiscent of analogue technology. The use of filters have become so widespread that the hashtag #nofilter has come to designate not only unadulterated photos, but also become a metaphor for being real, honest and authentic.Footnote33

According to Gil Bartholeyns most users of such mobile phone apps are digital natives, young people who have never themselves used analogue photography. He sees this kind of photography as a way of appropriating the present, of rendering it more poignant. Rather than bringing up memories from the past, it is a staged nostalgia without a referent.Footnote34 The study Bartholeyns made was an analysis of images tagged with nostalgia in a media sharing site, and I would argue that his findings are resonant with the way some Instagram filters are presented in The Atlantic magazine:

Nashville Effect: Sharp images with a magenta-meets-purple tint, framed by a distinctive film-strip-esque border

Use for: Photos that call for ironic nostalgia

1977 Effect: Gloria Gaynor-level ‘70s flair

Use for: Photos that call for in-your-face nostalgia (particularly useful now that Facebook is Timelined)

Lord Kelvin Effect: Super-saturated, supremely retro photos with a distinctive scratchy border

Use for: Photos that call for actual nostalgia.Footnote35

Note the distinction between “ironic”, “in-your-face” and “actual” nostalgia, which indicates that the readers of the article is supposed to be versed in the phenomenon of nostalgia and how to apply different aspects of it to images. In order to reach out to this kind of consumers, marketeers need to be fluid in the jargon used by the consumers and to be present in the places where they gather.

Pinterest and Instagram can be used as a marketing channel, just like Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. Many of the activities that were formerly carried out with the help of printed media or telephone, such as making consumers collect flaps from packages to get promotional gifts, issuing slogan competitions, and gathering feedback on products are now mainly performed with the help of the web. This does not mean that physical objects such as printed matter and packaging have become unimportant. Maintaining relations with consumers requires a range of different approaches and physical objects are still paramount, not least as carriers of photographs and other images. Packages, tags and gadgets can appeal to the tactile sense through use of different materials and textures, and in this way the visual message will be reinforced.Footnote36 The web also allows to a greater extent for two-way communication with consumers, who are now often contributing to marketing through posting comments and photographs on company websites and Facebook pages. Printing such user generated content on physical objects is a way for companies to acknowledge and gratify these efforts made by their consumers.

Tyrrells have encouraged customers to engage in their brand by sending in photographs to their website, or making up a caption for an existing photograph. The following text appeared on the back of a package of Veg crisps in 2012:

English eccentrics

Do you have English ancestors? If so, have a rummage around at home, and if you find any eccentric old photos of them, get in touch. You never know, old Auntie Ivy could be the next face of Tyrrells. Pop along and upload your piccies at www.tyrrellscrisps.co.uk/eccentrics

However, none of the pictures used so far on the packages are from family albums, instead they are stock photographs from former British picture libraries and press agencies, something I will return to further on. The family pictures received from customers were until 2015 displayed in a gallery on the Tyrrells website.

A request that appeared on packages in 2013 was “Coin us a caption.”Footnote37 On the webpage of the caption competition, the visitor could choose between some of the photographs that appear on the packages, send in the caption and also browse the gallery of previous contributions. In the food trade, this way of communicating with consumers through images is unusual. One of the few companies that does is the Canadian beverage producer Jones Soda, that under the slogan “Your photo Your soda Your brand”, encourages consumers to “Post your photo to our Jones Soda Gallery and if we like it we might use it for one of our labels.” They then display the selected labels as print ready files in a gallery on their website.Footnote38 In the fashion trade, however, the use of consumer photographs is frequent.Footnote39 In his article on the use of snapshot aesthetic in marketing, Jonathan Schroeder takes the British clothing company Burberry’s website Art of the trench as an example, where visitors are invited to upload photos of themselves or their friends wearing a trench coat. Photos taken by consumers appear in the gallery side by side with work by professional fashion photographers.Footnote40 A Swedish example is the campaign Swedish Export launched in 2010 by Björn Borg, which invites consumers to send in photographs of themselves wearing Björn Borg underwear to the company’s Facebook page, with the chance of winning a collection of underwear and to have their photograph selected as the profile picture of the Björn Borg Facebook page. The company has also printed a paper bookmark with some of the images from the campaign.Footnote41 Worth mentioning in this context is also Pashley, a British bicycle producer known for its classic-retro-nostalgic models, that devotes a section of its web gallery to consumers’ photographs, and print some of the best in their brochure.Footnote42

What companies using consumer generated content like these photographs gain is authenticity, emanating from the maker of the picture as well as from the snapshot aesthetic that in most cases characterizes the pictures.Footnote43 Noteworthy is also the use of physical artefacts in conjunction with online marketing campaigns. The Jones Soda package, the Pashley brochure, and the printed Björn Borg bookmark constitute physical instantiations of the images that would otherwise appear only on the screen. While some companies use photographs to increase consumer engagement in the brand, Tyrrells strategy is unique in its focus on old photographs, taken long before the advent of the camera phone.

Aura and the “original photograph”

Instrumental to explaining the appeal of the photographs on Tyrrells’ packages is the concept of aura. In his essay “Little history of photography” Walter Benjamin first defined aura as “a strange weave of space and time: the unique appearance of semblance of distance, no matter how close the object may be.”Footnote44 When Benjamin wrote about photography in the 1930s, the technology was nearly a century old and had gone through many changes since it was first invented, and it has undergone even more changes to this day. The aura of the old photograph is derived from both its subject matter and the technology with which the photograph was produced. The camera, the material and the process contribute to forming a sign with nostalgic connotations. In a study on new media and aura Jay David Bolter et al. compares an old paper copy of a black and white nineteenth century photograph of a cemetery with a virtual reality representation of the same place: “Even today a viewer is likely to feel the aura of such a photograph not in spite of, but because of its poorer quality, which suggests the technology of that time and emphasizes the historical distance between the original object and the contemporary viewer.”Footnote45

The paper copies of nineteenth century photographs have now become rare objects in themselves, as Jennifer Green-Lewis observes in her article on the attraction of Victorian photographs: “Old photographs, their negatives (and subjects) long gone, assume the aura of originals, not merely in terms of their economic value, but as points of reference or departure.”Footnote46 The abundance of prints advertised as “original photographs” on eBay testifies to the blurred line between original and reproduction within the field of photography. A seller of archive prints, NewspaperPhotographs, has published a guide to the confusing terminology under the title “What is an Original Photograph????” Phrases like “vintage reprint” and “original wirephoto” demonstrate that the perception and the appreciation of photography are not stable but change over time.Footnote47 A photographic copy that was transmitted over telephone lines by a news agency was once considered as an intermediary format without value outside that specific context. Today, wirephotos have become collectors’ items with an aura of their own, as is stated in another guide NewspaperPhotographs: “To be sure, with the advent of digital photography, the wire photo is truly an artifact of a bygone era.”Footnote48 This is a good example of how materiality matters in the contemporary image ecology.

The technical changes that the photographic medium has undergone in the past decades thus contribute to augmenting the aura of old photographs. Only with the advent of digital photography has “analogue photography […] become a medium in the fullest sense of the term” according to Margaret Iversen.Footnote49 A parallel to this development can be found in the recording industry, where the vinyl record has gained aura in the digital era of downloading and streaming of music. Not only have vintage LP:s become attractive collectibles, but classic albums are being reissued and regarded as the “‘authentic’ way to experience the pop and rock canon.”Footnote50

Although the photographs concerned in this article have an analogue origin, they are able to adapt to and form part of digital contexts such as websites and Facebook. They do not represent a sharp dividing line between old and new technology, but rather accrue new meaning and take part in defining their new context. Most photographs used by Tyrrells on their packages originate from press agencies and were thus intended for commercial use from the beginning, which means that the change of context is a matter of degree rather than kind.

Ephemeral carriers of durable images

In the case of the stock photographs on Tyrrells packages, their original presentational context was the printed page. The paper print was filed in the archive until the license to use it was sold by the agency to the next client. When the photographs appear on the crisp packages, they have moved from one commercial context to another, albeit one that was not foreseen by the photographers and the editors at the time.Footnote51 The newspapers and magazines were also mass-produced articles and the distribution shows similarities: both the crisp packages and the papers need a wide distribution at many retailers and their news value lasts only for a certain time before they are exchanged and new issues appear. Although Tyrrells has a number of flavours that are constant, they change the photographs on them from time to time. They also issue limited editions of certain flavours.

Newspapers, magazines and packages are throwaway objects that serve their purpose for a short time and then becomes waste. Press cuttings are brittle and turn yellow with age. Until the beginning of the 20th century, most packaging was meant for reuse, but with the emergence of the discourse of personal hygiene, disposable packaging became the norm.Footnote52 Tyrrells’ plastic snack bags are disposable packages that will rip open easily, which will inevitably damage the photograph. In a short news item in the Daily Mirror announcing a new flavour from Tyrrells, a reporter wrote: “We hesitated before opening as we didn’t want to ruin the pic.”Footnote53 This statement demonstrates that the packages are seen, not only as protection for food, but as carriers of photographs as well. In contrast to the ordinary paper supported photograph, the package is not flat and smooth. It is like a cushion, inflated with air and a little creased, which makes it difficult to see every detail of the image at once. You have to straighten it out and turn it a little in order to see the whole image properly. But flatness is not only about function, it is an ideal in photographic printing.Footnote54 The rattling sound of the crisps inside is also a distraction that usually does not belong to the experience of viewing photographic prints. All viewing is embodied, although the visual sense has been privileged over the others, and seeing photographs as objects means taking other senses such as smell and touch into consideration.Footnote55 Touching the surface of a photograph print will damage it, but in the case of packages the photograph is supposed to be touched and handled.

Tyrrells in the eyes of its customers: use and reuse

To get an impression on the use and reuse of the crisp bags I have turned to Instagram and to bloggers who write about Tyrrells’ pictures when reviewing the crisps. Furthermore, I have searched for Tyrrells’ bags on Etsy, an online marketplace for people who sell unique goods, including crafts made from recycled packages.

An examination of #tyrrells on Instagram reveals that a major occasion for consumption of Tyrrells’, like other snacks, is in conjunction with watching sports, TV series or films at home. The snacks are either held or placed in front of the TV in the manner of (), often with a comment of the taste of the snack.

The blogger Sharmaine Kruijver let her children test the crisps and then wrote in her review:

And finally, fourth of all…. HOW COOL IS THE PACKAGING??!!!

Oh my!

I smiled so broadly when I saw the fun pictures that were printed on each packet!

The crafter in me saw amazing possibilities

And can’t wait to add some packaging to my art journal pages!Footnote56

Mylittlesweethearts, an alias for Julia Romanus who sells her products at Etsy, shares this view of packaging as a material with great potential for craft making and she makes decorations, keyrings and small bags out of used wrappers in order to “preserve the images and designs we currently have for future generations.” Most food packages are throw-away objects, and with the growing concern about waste in terms of environmental impact, there is also an awareness of the cultural values that are discarded, something the exhibition To Pretty to Throw Away testifies to.Footnote57 The acompanying text to one of Mylittlesweethearts bags () reads:

Tyrrells are brilliant with their wrapper designs and this crisp packet is no exception. I have a new bag which has at its showpiece this fabulous photograph of a gentleman sampling some alcohol. My unique zipped pouch made from a recycled wrapper is handmade by me, fully lined with a black watch tartan material and backed with a classic linen-cotton beige fabric.Footnote58

Here the mass-produced item is made into a unique craft artefact, with the aura of an “original photograph” referred to above. It is an example of upcycling, which makes the disposable crisp package into a durable object, the thin plastic reinforced with fabric, to be preserved for posterity. It also gives the photograph a new and more robust tactility, different from the original, brittle package. This kind of upcycling is interesting seen in the light of a recurrent theme in the discourse about photography in the digital age, namely the loss of the materiality of photographs as objects. Daniel Rubinstein and Katrina Sluis have noticed how snapshot photography has moved from the family album and the shoebox, to online sharing sites such as Flickr. They argue that the large amount of images has turned the viewers’ attention from the single image to the slideshow and the photostream, where the photographs have become non-objects: “Within online networks the individual snapshot is stripped of the fragile aura of the photographic object as it becomes absorbed into a stream of visual data.”Footnote59 In a craft-making context, the ephemeral package and the ephemeral photograph have joined forces to halt the stream and assert their objecthood.

Conclusion

I will now try to summarize the ontological transformations of photographs, that has been highlighted by my case study. The aura of Tyrrells’ photographs depend, as I have shown, on a combination of motif, materiality, and technology. The package has a twofold appearance, as a physical object and as a virtual object on the web, both of which constitute the other. The materiality of the physical package has been extended into the virtual object and can no longer be disentangled from it. Entrenched dichotomies such as past–present, digital–analogue, material–immaterial, and original–copy are dislodged and in some cases overcome in the contemporary image ecology, where new digital photos are made to look old and old analogue photos are made up to date by being posted and commented on Facebook. Digital technology, often regarded as immaterial, facilitates the production of photographic objects such as the packages.

The crisp package is an ephemeral object that is meant to be thrown away. When the bag is opened, the photograph is likely to be destroyed—the bag can be seen as a snapchat photo, that is made to last for a short moment and then disappear. However, there are millions of new pristine samples in the shops, and although most of them are destined to be discarded, some will survive. It is similar to posting pictures on the Internet, once there they are likely to live on.Footnote60

The photographs on Tyrrells’ packages are traces of the past, but their nostalgic value is the engine that propels them into the future. They will continue their trajectory from analogue film and cameras, to press agencies, to the printed page, to stock image databases on the Internet, to crisp packages and birthday cards, to Facebook and Instagram, to crafted bags in digital marketplaces and so forth. This chain shows that there is no straight timeline from one technology to another, from material to immaterial, or from past to present. I agree with Bartholeyns in his conclusion that nostalgic and retro photography is a way of appropriating the present. One does not have to go back in time, one can stay in the present, albeit with a reinforced sense of presence. Time has always been a vital feature of the ontology of photography, often focusing on the moment of capture. In the digital era, the shutter is never closed. Even analogue photos are open for potential changes of appearance and a shift of context. A photograph in a dormant archive can be actualised at any time. Barthes’ famous characterisation of photography, “This has been” could now be changed to “This will be.”Footnote61 The Monty Python cut out aesthetic can be seen as a metaphor for the whole image ecology, where a photograph is an element waiting to be inserted in a new collage.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Karin Wagner

Karin Wagner is a professor in Art History and Visual Studies at the Department of Cultural Sciences at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. Her research interests include photography, new media, digital culture and visual communication. The research for this article has been carried out within the project The (un)sustainable package.

Notes

1. My transcription. Animation by Terry Gilliam, in Monty Python’s Flying Circus Season 1 Episode 3, 19 October 1969. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mhFu86jb7MU.

2. Belk, “Possessions and the Sense of Past,” 123.

3. Batchen, “SNAPSHOTS,” 121–14.

4. Jones, “‘Retronauting’: Why We Can’t Stop.”

5. Lash and Lury, Global Culture Industry: The Mediation of Things, 12.

6. Manghani, Image Studies, 36. A feasible alternative would have been image economy and the framework of visual consumption developed by Jonathan Schroeder. See Schroeder, “Visual Consumption in the image economy,” 229–44.

7. Edwards and Hart, Photographs, Objects, Histories.

8. Quote from a package of Mature Cheddar & Chives whose design was in use until 2011.

9. Other sources for the study have been trade journal articles, food blogs, recycling blogs, digital marketplaces, photo archives, press releases and an interview with Tyrrells marketing director.

10. Hofer, “Medical Dissertation on Nostalgia,” 376–91.

11. Davis, Yearning for Yesterday.

12. Boym, The Future of Nostalgia.

13. Ibid., 49.

14. Wagner, “The Power of Nostalgia,” 4–5; Hamilton et al. “Nostalgia in the Twenty-First Century,” 101–04; Muehling et al. “Exploring the Boundaries of Nostalgic,” 73–84.

15. Outka, Consuming Traditions.

16. Chrostowska, “Consumed by Nostalgia?” 52–70.

17. Hutcheon, “Irony, Nostalgia, and the Postmodern,” 189–207.

18. See image at https://www.elsastory.com/products/mini-pastry-bites.

19. Reynolds, “Tyrrells’ Oliver Rudgard.” Bigfish is the brand, design and marketing consultancy that has developed Tyrrells’present packaging design. http://www.bigfish.co.uk/blog/portfolio/tyrrells-2/.

20. Especially Hulton archives have been a rich source for Tyrrells. Hulton Press was founded in 1937 and published popular magazines such as Picture Post. It also had a large picture archive that in its turn built on older collections. http://www.gettyimages.co.uk/creative/frontdoor/hultonarchive; Gibbs-Smith, “The Hulton Picture Post Library,” 12–24; McDonald, Hulton|Archive—History In Pictures.

21. Wilkinson, “‘The New Heraldry,’” 23–38.

22. Cf. Were and Favero, “Getting Our Hands Dirty,” 259–77.

23. The Great British Tea party, a catering company that arranges mobile vintage tea parties, has a similar Facebook page where they regularly post old nostalgic photos https://www.facebook.com/GreatBritishTeaParty.

24. The description in Getty database reads “William Bufton judging the cider making competition at the Royal Counties Agricultural Show”. The photographer Edward G Malindine took the picture in 1948 when working for Topical press. This picture has also been used on birthday cards from Pigment Productions Ltd and Modern Times GmbH.

25. I have not been able to find this picture in any stock photo agency, but it appears on Tyrrells’ Facebook page. It is likely from the 1930s.

26. According to the description in the Getty database this picture shows “Spectators at a polo match at Cowdray Park, Sussex, during Goodwood Week, sitting it out in the rain.” The picture is taken in 1926 by G. Adams. It has been reversed on the package.

27. Fox, Watching the English.

28. In its original version, this photograph shows five young women doing handstand on a beach in Teignmouth, Devon, England in 1938.

29. Plakoyiannaki and Zotos, “Female Role Stereotypes,” 1411–434.

30. Fox, Watching the English; Paxman, The English.

31. Hemming, In Search of the English Eccentric.

32. In 2017, Tyrrells made a pythonesque TV-commercial http://www.thedrum.com/news/2017/09/08/tyrrells-bags-first-ever-tv-ad-campaign-with-eccentric-absurdly-good-push.

33. Tagdef, “Social Media Dictionary.”

34. Bartholeyns, “The Instant Past,” 51–69. Mike Chopra-Gant claims that “the nostalgia expressed through ‘retro’ digital photography represents a therapeutic response to an existential crisis of the self in postmodernism”. See Chopra-Gant, “Pictures or It Didn’t Happen,” 121–33.

in the first place.

35. Garber, “A Guide to the Instagram Filters.”

36. Wagner, “‘Looks great, feels amazing’: The tactile dimension of packaging,” 139–152.

37. “Coin us a caption. Now, we don’t know about you, but when we see an eccentric old photograph—like the one on the front of this bag- we can’t help but dream up a silly caption. If you are the same, don’t suffer in silence, unleash your wit at www.tyrrellscrisps.com/caption” On package of Mature cheddar cheese and chives from 2013.

39. Griffith, “Brands and the User-Generated.”

40. Schroeder, “Snapshot Aesthetics.”

42. My gallery, http://www.pashley.co.uk/gallery/my-pashley.php#dragos-solot.jpg.

43. See note 39 above.

44. Benjamin, “Little History of Photography,” 519.

45. Bolter et al. “New Media and the Permanent,” 30.

46. Green-Lewis, “At Home in the Nineteenth Century,” 32.

47. NewspaperPhotographs, “What is an Original Photograph?”

48. NewspaperPhotographs, “What is a Wire Photo (wirephoto)?”

49. Iversen, “Analogue: On Zoe Leonard,” 796.

50. Bartmanski and Woodward, “The Vinyl: The Analogue Medium,” 7.

51. It should be noted that the most of the images mentioned in the article are not free, but have been bought by Tyrrells from Getty images.

52. Lucas, “Disposability and Dispossession,” 5–22.

53. Sayid, “Tyrells Barbecue crisps.”

54. Adams, The Print.

55. See note 7 above.

56. http://skruijver.blogspot.se/2014/08/review-tyrrells-crisps.html 6 August 2014.

57. Garbage matters, https://www.garbagemattersproject.com/2016/05/18/to-pretty-to-throw-away/.

59. Rubinstein and Sluis, “A life more photographic,” 23.

60. van Dijck, “Digital Photography,” 57–76.

61. Barthes, Camera Lucida.

References

- Adams, A. The Print. Boston, MA: Little Brown, 1983.

- Barthes, R. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. New York: Hill and Wang, 1981.

- Bartholeyns, G. “The Instant Past: Nostalgia and Digital Retro Photography.” In Media and Nostalgia: Yearning for the Past, Present and Future, edited by K. Niemeyer, 1–12. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

- Bartmanski, D., and I. Woodward. “The Vinyl: The Analogue Medium in the Age of Digital Reproduction.” Journal of Consumer Culture 15, no. 1 (2015): 3–27. doi:10.1177/1469540513488403.

- Batchen, G. “Snapshots.” Photographies 1, no. 2 (2008): 121–142. doi:10.1080/17540760802284398.

- Belk, R. W. “Possessions and the Sense of Past.” In Highways and Buyways: Naturalistic Research from the Consumer Behavior Odyssey, edited by R. Belk, 114–130. Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research, 1991.

- Benjamin, W. “Little History of Photography.” In Walter Benjamin Selected Writings, edited by Michael W. Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith, 518–519. Vol. 2. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999 [1931].

- Bolter, J. D., B. Macintyre, M. Gandy, and P. Schweitzer. “New Media and the Permanent Crisis of Aura.” Convergence: the International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 12, no. 1 (2006): 21–39. doi:10.1177/1354856506061550.

- Boym, S. The Future of Nostalgia. New York: Basic Books, 2001.

- Chopra-Gant, M. “Pictures or It Didn’t Happen: Photo-Nostalgia, iPhoneography and the Representation of Everyday Life.” Photography and Culture 9, no. 2 (2016): 121–133. doi:10.1080/17514517.2016.1203632.

- Chrostowska, S. D. “Consumed by Nostalgia?” SubStance 39, no. 2 (2010): 52–70. doi:10.1353/sub.0.0085.

- Davis, F. Yearning for Yesterday: A Sociology of Nostalgia. New York, NY: The Free Press, 1979.

- Edwards, E., and J. Hart, eds. Photographs, Objects, Histories: On the Materiality of Images. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Fox, K. Watching the English: The Hidden Rules of English Behaviour. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 2004.

- Garbage Matters. “To Pretty to Throw Away, May 18, 2016.” Accessed June 16, 2017. https://www.garbagemattersproject.com/2016/05/18/to-pretty-to-throw-away/.

- Garber, M. 2012. “A Guide to the Instagram Filters You’ll Soon Be Seeing on Facebook.” The Atlantic, April 10. Accessed July 27, 2015. http://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2012/04/a-guide-to-the-instagram-filters-youll-soon-be-seeing-on-facebook/255650/.

- Gibbs-Smith, C. “The Hulton Picture Post Library.” Journal of Documentation 6, no. 1 (1950): 12–24. doi:10.1108/eb026151.

- Green-Lewis, J. “At Home in the Nineteenth Century: Photography, Nostalgia, and the Will to Authenticity.” Nineteenth-Century Contexts: An Interdisciplinary Journal 22, no. 1 (2000): 51–75. doi:10.1080/08905490008583500.

- Griffith, E. “Brands and the User-Generated Photo Conundrum. July 18, 2013.” Accessed August 3, 2015. https://pando.com/2013/07/18/brands-and-the-ugc-photo-conundrum/.

- Hamilton, K., S. Edwards, F. Hammill, B. Wagner, and J. Wilson. “Nostalgia in the Twenty-First Century.” Consumption Markets & Culture 17, no. 2 (2014): 101–104. doi:10.1080/10253866.2013.776303.

- Hemming, H. In Search of the English Eccentric. London: John Murray, 2009.

- Hofer, J. “Medical Dissertation on Nostalgia” Trans. by Anspach CK. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 2, no. 6 (1934): 376–391. (Original work published 1688).

- Hutcheon, L. “Irony, Nostalgia, and the Postmodern.” Studies in Comparative Literature 30 (2000): 189–207.

- Iversen, M. “Analogue: On Zoe Leonard and Tacita Dean.” Critical Inquiry 38, no. 4 (2012): 796–818. doi:10.1086/667425.

- Jones, J. 2014. “‘Retronauting’: Why We Can’t Stop Sharing Old Photographs.” The Guardian, April 13. Accessed July 27, 2015. http://gu.com/p/3zc5z/sbl.

- Lash, S., and C. Lury. Global Culture Industry: The Mediation of Things. Cambridge: Polity, 2007.

- Lucas, G. “Disposability and Dispossession in the Twentieth Century.” Journal of Material Culture 7, no. 1 (2002): 5–22. doi:10.1177/1359183502007001303.

- Manghani, S. Image Studies: Theory and Practice. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge, 2013.

- McDonald, S. “Hulton|Archive – History In Pictures.” August, 2004. Accessed December 8, 2017. http://corporate.gettyimages.com/masters2/press/articles/HAHistory.pdf.

- Muehling, D. D., D. E. Sprott, and A. J. Sultan. “Exploring the Boundaries of Nostalgic Advertising Effects: A Consideration of Childhood Brand Exposure and Attachment on Consumers’ Responses to Nostalgia-Themed Advertisements.” Journal of Advertising 43, no. 1 (2014): 73–84. doi:10.1080/00913367.2013.815110.

- NewspaperPhotographs. “What Is an Original Photograph? Guide on eBay, June 15, 2015.” Accessed July 27, 2015. http://www.ebay.com/gds/What-is-an-Original-Photograph-/10000000175046614/g.html.

- NewspaperPhotographs. “What Is a Wire Photo (Wirephoto)? Guide on eBay, June 15, 2015.” Accessed July 27, 2015. http://www.ebay.com/gds/What-is-a-Wire-Photo-wirephoto-/10000000020254581/g.html.

- Outka, E. Consuming Traditions: Modernity, Modernism, and the Commodified Authentic. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Paxman, J. The English: A Portrait of A People. London: Penguin, 1999.

- Plakoyiannaki, E., and Y. Zotos. “Female Role Stereotypes in Print Advertising.” European Journal of Marketing 43, no. 11/12 (2009): 1411–1434. doi:10.1108/03090560910989966.

- Reynolds, J. 2011. “Tyrrells’ Oliver Rudgard Has a Few Things in Common with the Posh Hereford Brand.” Marketing, November 3.

- Rubinstein, D., and K. Sluis. “A Life More Photographic.” Photographies 1, no. 1 (2008): 9–28. doi:10.1080/17540760701785842.

- Sayid, R. 2011. “Tyrells Barbecue Crisps Perfect for Summer.” The Daily Mirror, June 3. Accessed July 27, 2015. http://www.mirror.co.uk/money/personal-finance/tyrells-barbecue-crisps-perfect-for-summer-132316.

- Schroeder, J. E. “Visual Consumption in the Image Economy.” In Elusive Economy, edited by K. Ekström and H. Brembeck, 229–244. Oxford: Berg, 2004.

- Schroeder, J. E. 2013. “Snapshot Aesthetics and the Strategic Imagination.” In Visible Culture, 18. Accessed July 27, 2015. http://ivc.lib.rochester.edu/portfolio/snapshot-aesthetics-and-the-strategic-imagination/.

- Tagdef. nd. “Social Media Dictionary, Definition of #Nofilter.” Accessed July 27, 2015. https://tagdef.com/nofilter.

- van Dijck, J. “Digital Photography: Communication, Identity, Memory.” Visual Communication 7, no. 1 (2008): 57–76. doi:10.1177/1470357207084865.

- Wagner, B. “The Power of Nostalgia: Zeitgeist or Marketing Hype?” Pioneer University of Strathclyde Business School Magazine 4–5, Winter, (2010). Accessed July 27, 2015. http://www.strath.ac.uk/media/faculties/business/pioneer/issuepdfs/01-08_pioneer.pdf.

- Wagner, K. (2013). “‘Looks Great, Feels Amazing’: The Tactile Dimension Of Packaging”. In Proceedings of Nordic Conference on Consumer Research, 139–152. Centre for Consumer Research, Gothenburg University, May 30–June 1, 2012.

- Were, G., and P. Favero. “Getting Our Hands Dirty (Again): Interactive Documentaries and the Meaning of Images in the Digital Age.” Journal of Material Culture 18, no. 3 (2013): 259–277. doi:10.1177/1359183513492079.

- Wilkinson, H. “‘The New Heraldry’: Stock Photography, Visual Literacy, and Advertising in 1930s Britain.” Journal of Design History 10, no. 1 (1997): 23–38. doi:10.1093/jdh/10.1.23.