ABSTRACT

Returning old photographs to Sámi communities has been a part of modern repatriation policies, trying to recollect the Sámi heritage from museums, archives and collections outside the modern Sámi area. It is not only important to return items, such as photographs, but also to reconstruct the knowledge around them: to re-identify the old encounters and stories. The article suggests that the earlier interpretations have emphasised the inter-ethnic relations between the Sámi and the majority societies. When returned to local levels of Sámi communities, however, to be interpreted through the lenses of the Sámi subjects, the photographs tell multiple visualized stories about intra-ethnic “our histories”, the recent past of families, kinships and small Sámi communities. The article is based on my experiences and the projects that have been carried out in Finland in the past 15 years, repatriating photographs to Sámi societies.

In archives, museums, and collections all over Europe and USA, there are vast numbers of photographs concerning the Sámi people. Multiartist Nils-Aslak Valkeapää is probably the first Sámi who started to repatriate photographic heritage systematically to his people. When travelling the world as “a Sámi ambassador”, participating in indigenous peoples’ events and giving concerts at the venues of the world, he started to collect photographs of Sámi from different collections from Paris to London and Berlin.

Later Valkeapää said that he had spent six years actively collecting almost 400 photographs, which became a central part of his epic poetry book Beaivi, áhčážán (1988 The Sun, My Father). Apart from historiographical, mythical and personal levels, the archival photographs form a story of their own inside the work: the story also unfolds through them, because they were placed in certain phases of the poetic narrative. They reflect the cultural diversity of Sámi groups in marketplaces, for example. They present racial science studies, which the poems refer to. Photographs depicting the leaders of the Kautokeino Rebellion (in Norway 1852) naked after their capture are related to Sámi resistance.Footnote1

The author called his book “a Sámi family album”, because he wanted to demonstrate that collecting and repatriating photographs also communicated his affection towards his own people. When Valkeapää’s main work was being translated, he did not allow photographs in the other language versions. He stated that “the photographs belong to the Sámi”. Perhaps his choice also reflected bitterness of how researchers and photographers from the majority population had used his ancestors as guides, informants and photographic models, but he himself had to pay the museums for the right to return photographs of his ancestors or to publish them.Footnote2

Anne Heith has analysed Valkeapää’s way of using photographs in his book as an indigenous counter-history. According to Heith, two diametrically different perspectives are evoked at the same time in Beaivi, áhčážán, one of the colonial centre, including the people who arranged and exhibited the photographs for their purposes, and the other of a Sámi cultural mobiliser in the 1980s who uses them as a reflection of a post-colonial society’s emerging cultural identity. “Valkeapää’s book functions as a specimen of Sámi metahistory which exposes the conceptual strategies used in nineteenth and twentieth century production of knowledge about the Sámi”. Footnote3

I would also like to propose another dimension, which seems to emerge as at least equally important to the Sámi themselves, both in Valkeapää’s work and more generally in relation to old archival photographs. The Sámi themselves approach the archival photographs often from the community perspectives, revealing “small stories” of us and our ancestors rather than “big histories” of colonial circumstances and contradictions with outsiders’ societies. I have used the concept of our histories to depict the local understanding of the past, maybe not referring to inter-ethnic relations at all.

As the Finnish historian Jorma Kalela notes, many small communities tell their own histories, which can strongly differ from established or official historical descriptions or scientific representations of the past.Footnote4 In addition to majority interpretations on Sámi histories that were challenged by the Sámi movement from the 1970s onwards, the institutionalisation of modern Sámi society also regularised “official histories” of the Sámi, dominated by an emancipatory perspective which emphasises asymmetric power relations, subjugation, and colonialism.

Contrary to these, interviews in Sámi communities reveal that the individual and local levels usually dictate the approaches to the past. The do not necessarily recognise themselves in the general histories of Finland, Lapland or even (North) Sámi people, nor do they identify with histories of oppression, although these histories can be interpreted from their stories.Footnote5

Instead, their cultural memory is based on local connections between “us”, forming a network of belonging that is different to the official discourse on Sámi history. The latter concentrates heavily on inter-ethnic relations, while in “our histories” the insider context of individuals and families on a local level becomes essential when interpreting the past. Lien and Nielssen have interpreted this kind of process as an aim to create an open history as an alternative to the “Grand history”, the official and closed writing of the history books.Footnote6

My article concentrates on the photographic material in archives and in the Sámi area in Finland,Footnote7 although I make some references to other Scandinavian countries and other indigenous groups. At first, I shall describe the diverse context of the photographs in which the “outsiders” were taking about the Sámi from the middle of 19th century to the post-war era, focusing on the main archives of Finland. Secondly, I will turn to the Sámi perspective of the past 20–30 years, also using my own experiences in repatriating photographs to Sámi communities in the projects of Sámi Siida museum in Inari,Footnote8 as well as editing Sámi publications with photographs, including my own research Saamelaiset suomalaiset (2012) on Sámi-Finnish relations in the first half of the 20th century.Footnote9

Photographs of the others

Until the 1960s and 1970s, photographs of the Sámi were mainly taken by outsiders. The earliest photographs of Sámi people are from 1855, but some collections from the 1860s have been labelled as pioneering work, especially the photos by J. A. Friis in Finnmark and on the Kola Peninsula in 1867, as well as the collection of Lotten von Düben in Kvikkjokk in 1868, published in Gustaf von Düben’s On Lapland och lapparne (1873) ().Footnote10

Figure 1. The Sámi could be quite pictorial for the photographers. The postman of Utsjoki, Oula Guttorm, was visiting the city of Oulu in 1932, when the newspaper Kaleva photographed him. Kaleva Archive.

Scientific expeditions focusing on polar research especially in the 1880s became important for creating Sámi photographical imagery both in Norway and Finland. Danish Sophus Tromholt was a scholar of northern lights, travelling with an expedition and later publishing his portraits on the Sámi in Finnmark in the book Under the Rays of Aurora Borealis in 1885, when the book Om den Finska Polarexpiditionen was also published in Finland, based on the travels of Finnish researchers on the Kola Peninsula.Footnote11

Researchers, civil servants and travellers carried heavy cameras with them and recorded what they saw and experienced. There were two main subjects in the early photographs from Sápmi: nature and Lapps. Settlers, for example, (whether they represented the majority populations or farming Sámi in majority clothing) were photographed as considerably less than “genuine” Sámi, whose distinct clothing and culture were emphasised by the photographs.

As a visual novelty, photography came to continue and challenge the tradition of drawn and painted representations of Sámi people. Nicholas Mirzoeff has described this connection provocatively as the “death of painting” and the rise of photography as the “birth of a democratic image” or a modern way of capturing time.Footnote12 Photography became one of the most powerful methods for the evolving discipline of anthropology, contrasting the “primitive peoples” and the normative European cultures. Hannu Sinisalo describes:

“Although the photography was, for anthropologists, just one method of field documentation along with writing and recording, observations were based first and foremost on visual phenomena. A photograph documented, copied and delivered the visual data of research to other members of one’s own culture. When these artefacts were collected to archives, museums and exhibitions, they became part of the Western framework through which we see the remains and objects of strange cultures.”Footnote13

Many studies have testified that the photographs were often used as a central method of racial characterisation and documentation, which resulted in their visual “anthropologisation” and classification for “folk types”. The main character of this material is racialisation, cultural homogenisation and—in the words of Homi K. Bhabha—the notion of “the many as one”. As Heith states, in this construction of Sáminess there was no space from where the Sámi could speak. Footnote14

All image material cannot be directly categorised as anthropological material, however, because photographs were taken and used for quite different purposes from the start. The media and the general public were also interested in them. There must have been earnest curiosity and thirst for knowledge of different cultures and ways of lives. The photographs also strengthened the status of the photographer as an expert in Sámi culture. Additionally, the technological development made it possible to introduce photographs for wider audiences.

An interesting question in relation to historical photographs of the Sámi is the sliding border between documentary and artistic forms of photography. Such idealisations or iconification tend towards stereotyping the sitter, as for example “noble savages”. Already the early photographers from von Düben to Tromholt seem to have idealised their objects in their portraits, in a way that highlights the “traces of life” in the faces of natural people, rather than focusing on their characteristics. Thus, the most famous historical Sámi portraits may be compared to Edward S. Curtis’ Indian pictures of “a dying race”. The documentary value of the photographs varies. Some photographers provided scientifically detailed information on the subject, while others saw the subjects as representatives of the whole group without need for individual characterisationFootnote15

In Finland too, geographers and cartographers, such as researchers in the geological department, were the first documenters. The goal of the photographers, apart from capturing majestic wildernesses with their indigenous inhabitants, was to immortalise “a vanishing culture” that was about to give way to civilisation. Natural scientists seem to have been interested in the Sámi as “a phenomenon”, a cultural form adapted to nature, but also endangered. This is why they considered it more important to write down places and geographical areas, where the photographed groups lived, than names or kinship backgrounds.

Contrary to this, scholars of human geography and Sámi culture had another attitude. One of the first researchers to systematically take photographs of the Sámi and publish them in books, for example in the monograph Lappi (1911), J. E. Rosberg, was professor of geography and the leading expert in Sámi issues at the beginning of the 20th century. As the first researcher in Finland, he wanted to use photographs to create research material for race theoretical measurements. For that purpose, he gathered Sámi people next to shed walls or in front of their homes for group photographs and listed their names, measurements and physique in minute detail.Footnote16 In 1910 in Helsinki, Rosberg arranged a Skioptikon presentation where he reflected images of Lapland’s nature and Sámi on the wall for the general public to see. The presentation was vivified by real Sámi when Finnish Sámi participants of the so-called Lapp caravan headed by Juhani Jomppanen were returning from a German tour.Footnote17

During the 1920s and 1930s, cameras became more widespread, and Finnish public servants such as pharmacists or vicars in northern regions could also get enthusiastic over photography.Footnote18 The general trend in the 1920s and 1930s was still ethnological photographs, where Sámi were portrayed as an exotic group in nature. Photographing outdoors was necessary for lighting, although indoor photos were also taken next to the fireplace, by the window or with artificial light such as mirrors.

In their time and afterwards, the ethnographic archival photos have been used as illustrations for books and articles, usually without interest in their contents and meanings. Printed as numerous photographs in the 1920s and 1930s for instance, it was typical to refer to the Sámi as “Lapps from Enontekiö. Photo: J. E. Rosberg”, “Lapp girls. Photo: A. Nurmela” or—in a book cover in 2004—“A Lapp family in a reindeer corral in 1920s. Photo: E. Mikkola”. Photographers and sometimes even cameras were carefully mentioned, while the subjects were nameless, representing cultural or racial “Lapps” ().

For the Sámi, this way of using photographs is considered to be highly problematic. Berit Åse Johnsen from the Sámi museum in Karasjok has stated that “the postcard-Sámi is a notion”: according to her, the Sámi often juxtapose the postcard use of photographs with the abuse of Sámi culture.Footnote19 In books even up to the present day, it has often been more important to identify “Lapps” as a separate group rather than as individuals, although one reason can also be that original information about the contents is sparse.

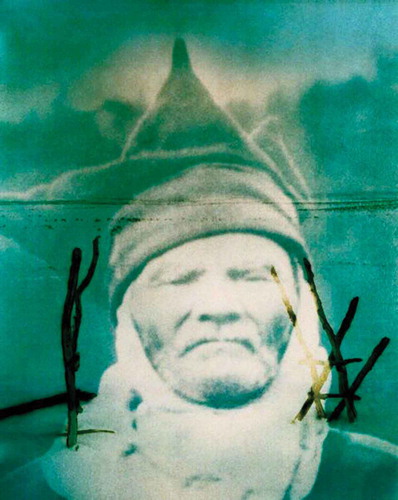

Today, in the “double exposure” of the past and present, archival photographs can provide a direct viewpoint to the borderlands in Sápmi. There are many ways to apply them in order to reconstruct memory of the past. In the manner of the Finnish photographer Jorma Puranen and Sámi artist Marja Helander, they can be utilised as tools or as inspiration for artistic work, returning the “nameless” Sámi to their own contexts and building a bridge between the past and modern Sámi identity. Puranen has said that it was Nils-Aslak Valkeapää who familiarised him with old photographs, and he was especially thrilled by the work of G. Roche from the expedition of Roland Bonaparte. With the title “Imaginary Homecoming”, Puranen started to make collages aimed at studying “temporal and spatial distance”.Footnote20 ()

Figure 3. In 1990s, photographer Marja Helander made a collage about her ancestor, Kadja-Nilla Vuolab.

In her “The Generations” series and in her Kadja-Nilla pictures in the 1990s combining landscape pictures with old archival photos, Helander explored her own relationship with ancestors, making her identity work as a Sámi who has grown in a city and later comes back to her roots in Utsjoki. The definition of Puranen, concerning his own works, also describes Helander´s work, attempting “a dialogue between the past and present; between two landscapes and historical moments, but also between two cultures.”Footnote21

In addition to artistic approach, old photos can be considered in research as evidence of encounters between the Sámi and outsiders. For visual anthropologists, photographs capture our gaze at the Other as a way of looking at something culturally different. In fact, they can tell as much about the photographers themselves as about the objects, because the way to depict the Other can be considered a reflection of your own context or as “a visual mapping of colonial experience”, as Elizabeth Edwards states. Footnote22

A third way to examine ethnological photographs is to restore them to the local level, to those people whose ancestors they depict. Among the Sámi, they have been used and are still used by Sámi artisans, for example, as historical sources (and inspiration) in reconstructing old costumes and handicrafts. Moreover, the Sámi can recognise their own ancestors or prominent persons and events from their home area. The persons in the photographs are no longer just any Lapps from the wilderness, but the photographs convey personal narratives, histories of families or clans. When nameless photographs have been moved from archives back to the Sámi communities, they have started to tell completely new stories—“our histories”.

Repatriation of visual memories

For centuries, Sámi culture has served as a resource pool of information, collecting objects, and cultural imagery, including photography. Participating in linguistic and cultural research or being subjects of racial studies or anthropological or touristic photography have engaged the Sámi, generations after generation; possible modest implications of compensation have been countered with offended astonishment about the mercenary ways of the nature folk.

A general trend has been that the knowledge and information collected in the name of ethnological, archaeological or linguistic research have not returned to Sámi communities. As Heith describes, the Sámi were documented by scientists, photographers and collectors from numerous countries, and the collected material was catalogued and displayed in various locations not connected to the world of the Sámi people.” Footnote23

Especially from the 1980s on, the Sámi have become more aware of the vast collections of their heritage in museums, archives and collections in different states, as the collections of Nils-Aslak Valkeapää reflect. The intensified interest in repatriating or returning the Sámi material heritage to the Sámi area especially in the 1990sFootnote24 also increased desire to learn more about the “photographic heritage”. In Finland, establishing the Siida Museum in Inari both implicated and created a remarkable development.

In the Sieivagovat seminars in the Siida Museum in 2001–2006 for instance, archival photos were brought back to the local people, to be identified and contextualised. In addition to collecting information, the photographs were discussed in public meetings around the photographic presentations, bringing up vivid memories and partly forgotten experiences from the past. In the manner of yoik music for instance, the photographs could also recall already departed people to join you. The stories collected about the photos—their contexts, persons and events—turned out to be precious histories of persons, families. and areas—“our histories”.

This repatriation process was simultaneous with decolonisation projects among other indigenous peoples, often carried out without knowledge of each other. As Lien and Nielssen describe, Australian Aboriginals, the Blackfoot people in Canada or the Sámi museum of Karasjok, Norway, had similar tendencies in the beginning of 2000s to add situation, time and context to colonial photographs, thus transforming “us” into agents in their own histories. “The pleasure of recognising a family member seems to overshadow the negative experience of been regarded by the gaze of powerful outsiders.” Lien and Nielssen state:

In this way, photographs that work as a reminder of oppression and a lost past become instead important in the effort to strengthen local identity and recreate history. And the stories now told through these images are stories of local communities otherwise ignored or denied by history writings.Footnote25

When the perspective turns the other way around, the illustrations or postcards “without contents or even names” start telling different stories. Considering the postcard “Lapps from Enontekiö. Photo: J. E. Rosberg”, they are not just any Lapps, but famous persons of the “Kova siida” reindeer Sámi community in the Enontekiö-Kilpisjärvi region. Moreover, it is an interesting historical situation: on the shore of Lake Kilpisjärvi in 1905, Aslak Juuso, a poor shepherd, has just arrived from the Swedish side (which can be recognised by the tassel in the hat) to serve Labba brothers Duommá, Nils, and Jovnná. For Juuso or Gáijjot, or Kaijukka in Finnish, this moment meant a starting point in his rise to lead the renowned Kaijukka reindeer village and become a major figure and “the patriarch” of reindeer siidas in Eastern Lapland. The photograph also documents Finnish racial studies even ironically. The photo was taken by Professor Rosberg (behind), the most prominent expert on Sámi issues at the time, acting as a yardstick for comparing the heights of the races, from Rosberg himself, 183 centimeters tall, to the “Lapp race” represented by Aslak Juuso, 153 cm tall.Footnote26 ()

Figure 4. Geographer J. E. Rosberg visited Kilpisjärvi in 1905 and met Labba brothers Duommá, Nils, and Jovnná with their new hired hand Aslak Juuso from Swedish side. When the photograph was later copied for a post card, it only commented: “Lapps from Enontekis.”

Identification of the photographs was cumbersome but also rewarding work, especially when finding eye witnesses with a particularly accurate memory of ancient events. I was for example able to trace one of the women who were photographed as young girls in the postcard “Lapp girls” at the end of 1920s. The postcard-image shows girls in a boat on the shore near Riutula orphanage home. My informant could, after more than a half century, name all the girls sitting in the boat, including one whose face was outside the frame of the photograph. She remembered not only the situation when the image was taken, but she could tell me all their earlier and later phases in the life, including new family names.

The same accuracy of memory was also astonishing in another informant who features as a child in a photograph of Erkki Mikkola entitled “A Lapp family in a reindeer corral in 1920s” (later published on a book cover). She too was able to provide precise information on the other subjects in the photograph, with one exception. Amazed by her explicit memories, the interviewer jokingly asked her to also identify the dogs. The informant (who was not a playful person) named all the dogs, except one which—according to her—“obviously has to belong to that man that I don´t know” ().

Figure 5. In 1931, Erkki Mikkola took a photo of Henddo-Niillas or Nils Valle in Gámásmohkki, Utsjoki.

The photographs turned out to be an interesting encounter of two “travelling cultures” (in the words of James CliffordFootnote27) in Kaamasmukka, Utsjoki, in 1931. The other traveller was Erkki Mikkola, a man from the south with Lapland “fever”. He was a pioneer in using a panorama camera to depict Northern Finland; the talented man was later killed in the Winter War in 1940.Footnote28 Here, after an exhausting trip to Lapland with the heavy machinery and guided by Jovnnáš-Jovnná (second from the right), Mikkola met another traveller, Henddo Niillas or Niillas Valle (in white), who had just married Káre Aikio from the Panne family (third from left) and moved to the Finnish side from Norway with his herd of 3,000 reindeer. At the moment of the encounter, he was having the first round-up in the midsummer.Footnote29

There are some references to general histories, including border closures and the orphanage homes in Sámi area, but is seems, however, to be typical for “our histories” to be specifically local or even “private”, related strongly to certain families or kinsfolk. For an outsider cultural historian for instance, seeking for Sámi perspectives on colonialism, modernisation processes or even encounters between two cultures, these interpretations of the photographs could be a little disappointing or even boring. In the community level, “our” experiences—remembered in a detailed manner even after a lifetime—are emphasised, maybe without the slightest reference to Finnish society or Sámi-Finnish relations.

The perspective could be considered self-sufficient. When remembering all “our” people and even dogs by their names, informants can describe the other part of the encounter behind the camera by referring to “muhtun láddelaš”, some southerner. In the same way that the photographers were rarely interested in the individuals and their personalities, the Sámi were also now ignoring the people behind the camera. These perspectives are opposite to each other, but I do not find them contradictory or incompatible. They are both gazing on the “other”, but are doing it on different sides of the border.

Multiple histories in archives

It is true, however, that the perspectives initiated by the repatriation work of archival photographs seem to challenge some prevalent assumptions of Sámi histories and representations. One example is the role of modernisation in the lives of the Sámi. When collecting material from the post-war period mostly from private archives, the modernity seemed not to be as strange an element as expected. Modernity was not represented as an intrusion into a society frozen in traditionalism, but as an integral part of the normal life, so the elements of modernity in Sámi culture were neither seen as something shameful or exaggerated.

This also led to a re-evaluation of the archival contents. It became visible that historical collections are more complex in character than often assumed. They do not necessarily provide a one-sided image of the Sámis as “the others of modernity”.Footnote30 In his publication of historical photographs, Valkeapää for example presented a photograph of a proud Skolt Sámi from the 1920s with an accordion on his knee. In my material from the Finnish archives, there could be a self-assertive group of Sámi in the 1930s posing outside a car, or a smiling postman in a traditional Sámi costume speeding along powered by an outboard motor. For informants, these situations were normal and the comments were focused on the life stories of these persons and their relations to social networks, while the technical novelties were only referred to, mostly because the researcher was interested in them.

In his book Indians in Unexpected Places (2004), Dakota historian Philip J. Deloria has adopted the concept of anomaly or exception to highlight this issue. He starts with a photograph of a Red Cloud woman (Sioux) in full regalia at a hairdresser’s in the 1940s which, according to Deloria, arouses some chuckling among us because of “an unexpected anomaly”. Deloria notes that this is a typical stereotype of “primitive” or traditional in opposition to “modern”, which is a very deeply-rooted concept even among researchers.

When these anomalies start to increase and recur in the material, however, they make you suspect the rarity of “exceptions”. Thus, not only are they describing our biased attitudes and expectations, but also questioning the rarity of such situations in real indigenous histories. Deloria writes a whole book to argue that some Indian people very early, and more than we often are led to believe, leapt quickly into modernity; “not because they adopted political and legal tools from whites or because of acculturation or assimilation but because of their own will”. He suggests that “a significant cohort of Native people engaged the same forces of modernisation that were making non-Indians reevaluate their own expectations of themselves and their society”.Footnote31

This kind of interpretative change also requires a new stance towards source materials and the contents of archives. From another perspective, the archives also spoke another language, proving more multifaceted and diverse than expected. In the “unorthodox” photo material, there could be “Lapps in unexpected places”, like a Sámi group visiting a Sámi exhibition in a southern town, or a Sámi youngster in 1930 going to military service. This way, photographs can illuminate Sámi histories in different kinds of institutions in which they have been increasingly involved during the 20th century: in addition to military service, there were children’s homes and schools with dormitories, which became a dominant part of Sámi lives, especially after WWII ().

Figure 6. A North Sámi from Inari, Májjo-Ásllat (Länsman), going to military service in the city of Oulu in 1933. A national magazine Suomen Kuvalehti wanted to photograph him.

In Norwegian collections, there are similarly large materials covering the histories of “Sámi Globetrotters”, for example. Sámi reindeer herders going global in the 19th century: Sámi men guiding a Norse polar expedition in Greenland or Sámi groups moving from Finnmark, Norway, to Alaska to teach Inuits to herd reindeer, or “Lapp caravans” touring in Europe from the 1820s to the 1930s introducing Sámi culture within the framework of popularised ethnography.Footnote32

Especially in the case of institutions, there can be interesting double exposures depending on the chosen perspectives to analyse them from. One of the iconic images in Sámi history is the photograph of a Sámi classroom in Karasjok, where a Sámi boy is obviously reading text in Norwegian about “mormor”, grandmother, following the reading with a pointer (in fact, a similarly iconic piece of film shows a Sámi girl writing the word “mor” (mother) on the blackboard). The children in Sámi dresses are watching the scene. When the photograph was taken, it dignified the success of the Norwegian education system. Afterwards, it has been interpreted as a striking reflection of the assimilation policy (Norwegianisation) in Norway.

In Sámi “our histories”, the focus would be moved more to the pupils: who they were, what kind of homes or environments they come from, what happened to them? Of course, the history of Norwegianisation could come up when considering the teacher, her personality and role among the other Norwegian teachers and more generally, authorities. The perspective would depend on the context of communication—who would be the interlocutor, and what is supposed to be discussed with him or her? “Our histories” differs from the perspectives you will deal with with a stranger, an outsider or even a Sámi researcher who has shown interest in analysing the interethnic relations.

As mentioned earlier, the emphasis on distinctive features has dominated both outsider and Sámi representations of the Sámi culture. In the repatriation process, this paradigm was also dismantled in the photographs of, for example, the Aanaar Sámi in their Finnish clothing, which they had begun to use along with Sámi as early as the beginning of the 20th century. The slouch hat had become the “national” or ethnic headwear of Aanaar Sámi men, while a white fabric linen belonged to the festive garment of women. The “our history” perspective ensured, however, that the Aanaar Sámi people were recognised in the photographs.

The prevalent trend was, however, for many photographers of that time not to have Fennicised Sámi in their photographs. Sámi in Finnish clothes were too similar or uninteresting models for them. An interesting period in the photographic material on Sámi is the evacuation of the Finnish Sámi to Central Finland during the German War in 1944–1945. There are hardly any photographs from this period in archives, except for a few in private collections. The clothing of the Sámi was left at home in the crisis and they often had to dress in Finnish clothing. Photographers or photograph archives were not interested in that. Among the only photographers who visited the Sámi at their evacuation locations was engineer Eino Jokinen, who had already visited Utsjoki at the end of 1930s.Footnote33 ().

Figure 7. Máret-Niillas Pieski (on the right) as an evacuee in Österbotten during the winter 1944–45. Piera Porsanger is using a Sámi costume, while Niillas and Jouni Porsanger are dressed on Finnish garments.

Although the Sámi were already living in a multicultural environment in the first half of 20th century, many researchers of that time considered the new influences as only damaging to genuine Sámi culture. Consequently, there exist only a few such pictures as geographer Karl Nickul, for example, took of Skolt Sámi girl Agni from the Sverloff family, drinking tea at the family’s summer dwelling. The photograph includes an element that many photographers would have felt disturbing: a food crate with the text “Cube Sugar. Tate & Lyle Limited, London”, which reveals the international character of the Pechenga dock area. In the life of Skolts, a crate could well serve as the table of a temporary dining place. Among Finnish travellers of that time, such a sight could have started a discussion about the degeneration of Skolts and the death of genuine culture ().

Figure 8. Agni Sverloff, a girl from Suenjel Skolt Sámi sijdd, is having an afternoon tee at the summer place of her family in Beahccam or Petsamo area in 1930s.

In his book, Deloria suggests that indigenous communities were often as active subjects in the modernisation processes as many other majority communities.Footnote34 His thinking can be applied to the relations between the Sámi and majority populations. The Sámi were subject to the same modernisation trends as the Finns. Sámi communities in Tana or Pechenga, for example, benefited from multinational markets and could be even more “international” than agricultural communities in the Finnish midlands in Savonia or Kainuu, for example.

Own pictures

What was the relation of the Sámi to photography in earlier history, then? Sophus Tromholt noted what kind of curiosity his heavy photographing equipment aroused in the Sámi communities. The positive attitude was counterbalanced by the rigidly negative Laestadian attitude to photography, as well as the connection between photography and racial research expeditions, which sometimes had to use small-scale pressure or even “mild violence” to get Sámi people photographed.Footnote35

Photography was at least partially connected with racial measurements from Rosberg onwards, in Finland too. Rosberg did not take nude photographs, for example, as later anthropological expeditions did. He was even reluctant to ask the Sámi to take off their moccasins, because he thought that the Sámi did not want to expose their feet, although “they were beautifully white”.Footnote36 When detailing the measurements of Sámi, Rosberg mentioned their heights with and without moccasins for the sake of correctness. In a sense, this revealed the absurdity of the measurements or the characteristic that drove Finnish racial studies into crisis in the 1920s and 1930s: the measurements produced so many different variables that it was eventually impossible to draw any kind of conclusions from them.

Anthropological research groups travelling with technical equipment, especially in the 1920s and 1930s, aroused various kinds of negative sentiments in the Sámi area. “Sometimes it turned out that a whole village folk went into hiding when they heard that researchers were coming,” complained research director Esko Näätänen.Footnote37 Photographing both adults and children in the nude became a source of irritation. There were rumours circulating among the Sámi that it was the goal of the photographers and researchers to take nude photographs and publish them in newspapers.Footnote38 Some researchers have implied that the anthropological interest could also have had an erotic and “voyeuristic” character.Footnote39

The accusations were not without foundation, although they could also be confused with the actions of “tourist photographers” resembling journalists. For example, Utsjoki county constable E. N. Manninen was a keen photographer who made feature stories for southern newspapers. The rumour may have started when E. N. Manninen published in a 1933 Suomen Kuvalehti magazine a photograph of a breast-feeding Sámi woman, which was even featured on the cover.Footnote40

The attitude towards racial studies at that time was, however, more intricate than has been later considered. This is reflected in the fact that Nils Thomasson, the first Sámi photographer, made part of his living specifically from racial scientific photography. Thomasson photographed his own people extensively in the first half of the 20th century especially in Jämtland. His works have become iconic as portraits of South Sámi individuals and families. He made postcards for the needs of increasing tourism in his home area to be able to support himself with photography. He also accepted work as an arranger and photographer for racial scientific studies.Footnote41

The earliest Sámi photographer in Finland was Uula Sarre, a fosterling of an Inari Sámi children’s home, who did not stay in the occupation, however. Uula’s father died when he was six years old, and he had to live almost as a beggar, until the newly founded Riutula children’s home in Inari took him in care. Eagerness in farm work and handicraft skills made the young man steward of the Riutula farm at the tender age of 20. At the beginning of the 1920s, Sarre acquired a folding camera, which he used to photograph both the stages of his own life and the lives of the Sámi. His photographs were published in the Suomen Kuvalehti magazine and Helsingin Sanomat newspaper. He gave up photography soon after moving to southern Finland.Footnote42

Two North Sámi men are also known to have photographed in the 1930s, although only a few of the works have been published. Aslak Outakoski was son of a Sámi teacher who had moved from the Sámi area to the Oulu region on the shores of the Gulf of Bothnia. The family was politically active in Sámi issues, and Aslak Outakoski became known as a prominent researcher who also took photographs on his travels to the north. He resembles Thomasson in that he also helped to carry out racial studies in the Sámi area by making Sámi portraits for the researchers.Footnote43 The teacher in the Outakoski village in the Utsjoki county, North Sámi writer Hans-Aslak Guttorm, is also known for using a camera before WWII. Footnote44

Pekka Paadar was an Inari Sámi who also took up photography before WWII. He photographed his own environment or the Nellim “borderlands” where the Sámi and Finns had lived side by side for a long time. Apart from traditional hunting economy, he photographed the cultural change of a “roadside” village and life at logging sites for example, in which Inari Sámi people also participated. Compared to Sarre, Paadar’s works manifest artistic ambition, although he was not known to have offered his photographs to magazines. The value of the photographs was not recognised until the 1990s when they were collected for an exhibition at the Provincial Museum of Lapland.Footnote45 ()

Figure 9. An Aanaar (Inari) Sámi Pekka Paadar bought a camera at the end of 1930s and started to depict the everyday life of his home village, Nellim. Aapo Paadar or Palokuja in the photograph.

The “inside perspective” of Pekka Paadar reflected the change in photography in the post-war period, when the technical developmentmade the photography even more democratic in that ordinary tourists, journalists and Sámi themselves could start it as a hobby. Snapshots could better reach the private lives of the Sámi and bring new possibilities for capturing “our histories”. It is also obvious, on the other hand, that new techniques produced a chosen material and imagined reality when, for example, “the family album gaze” focused on the special moments of families, such as festivities, marriage and funerals.

In addition to indigenous photographers, Carol J. Williams has interestingly focused on early indigenous photograph collections with the native peoples in British Columbia. Compared to dominant imageries of “Indian exhibitions” by outsiders, the collections of Native Americans themselves represent a very different genre, containing mostly images of “our histories”: portraits of families and other relatives. In these photographs, exotic or ethnic markers are even strikingly missing for the most part, since the people are usually presented in neutral contexts, such as in photographer’s studios and dressed up in “Western” clothing. Photographs challenge many of the “othering” features when, for instance, introducing portraits of Native American individuals or families looking prosperous in European terms (!)—thus, reminding us that prosperity is equated with the images of sophistication.Footnote46

Information about the earliest Sámi collections has been difficult to find in Finland, because much of it was destroyed in the Lapland War when the Germans devastated much Sámi property during their retreat. Although many of the researchers and photographers roaming in the Sámi area never sent the photographs they took to their subjects, it is probable that some of them sent photographs or delivered them by some other means, on their next trips to Lapland, for example. Travelling photographer’s studios also became more common in the 1920s and 1930s, and Sámi could have a photograph taken of themselves and their families on their visit to the marketplace.

There could also be other interesting photographs in Sámi possession. Finnish Sámi participated in the previously-mentioned Lapland caravans in 1910, 1925 and 1930, when they toured Germany, among other places. There is information concerning the latter tours that the entourage was photographed for selling postcards on the tour. The best salesmen were the Sámi themselves, of course, who also kept photographs as “souvenirs”. These photographs still existed in private collections in Inari, for example, despite the destruction of the German War.Footnote47 ()

Figure 10. The Sámi traveled in Middle-Europe in “Lapp caravans“ even in the year 1930, when they were photographed. They sold photographs, which also drifted to their home albums afterwards.

As noted earlier, distinctive characteristics were emphasised in postcards. On the other hand, photographs taken in travelling studios, for example those that the Siida Museum later found in private collections, are reminiscent of Williams’s observations. To an outsider, these portraits contain hardly any ethnic characteristics, while an insider—or an outsider with adequate cultural knowledge—can recognise them by the woman’s white scarf, the man’s shoes or generally from cultural knowledge. Dressing in Finnish clothes when posing for a photograph may have been “fine” for the Sámi themselves especially in the post-war times.

Conclusions

Returning old photographs to Sámi communities has been a part of repatriation policies in general, trying to re-accumulate the Sámi heritage from museums, archives and collections outside the modern Sámi area. It is not only important to return items such as photographs, but also to reconstruct the knowledge around them: to re-identify the old encounters and stories. They are not only testimonies of past events or cultural encounters. When interpreted through the lenses of the Sámi subjects, the photographs tell multiple illustrated stories about “our histories” and the recent past of families, kinships and small Sámi communities.

Thus, photographs can serve as components of “emotional archives”, transmitting experiences and memories. This approach differs from conventional historiography, even when constructed by the Sámi themselves. Such historical writing tends to emphasise the inter-ethnic relations between the Sámi and the majority societies. Although the interpretations can differ greatly and even seem contradictory to each other, I consider them rather as different perspectives, which may complement each other.

I totally agree with Heith that “the experience of colonisation is a continuing aspect of a postcolonial society’s developing cultural identity” among the Sámi.Footnote48 However, this specifically concerns the photographs reflecting the relations between the Sámi and majority peoples, studying how distinctive features of the Sámi culture have been emphasised in the visual representations of the Sámi. In “our histories”, the gaze seems to be aimed in another direction, focusing rather on features that are common to “us” in the local network.

The other analyses the inter-ethnic power structures, problematising the colonial encounters, while the other point of view concentrates on the Sámi agencies operating in their own communities. Concerning the “double exposure” the same image can be interpreted very differently depending on the perspective. The point of view of Sámi communities, for instance, highlights their own representations of “modernity” in an anomalous way, thus problematizing essentialistic conceptions of the indigenous cultures being opposite to modernity.

The repatriation of photographs is one means to analyse these perspectives. To have a whole picture, you must to examine the contexts and the experiences of both sides. The point of view of the Sámi has been underrepresented and more studies are definitely needed. My notions have hopefully implied, however, that there would also be need for deeper analysis of the diverse approaches of the photographers and their imageries on the Sámi.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Veli-Pekka Lehtola

Veli-Pekka Lehtola is Professor of Sámi culture at the Giellagas Institute for Sámi studies at the University of Oulu, Finland. He has been focusing on the history of the Sámi and northern Scandinavia, as well as the representations of the Sámi people, also produced in Sámi arts, politics and research. Professor Lehtola is the author of The Sámi People – Traditions in Transition (University of Alaska Press, 2004). He has published twelve monographs, mostly in Finnish, and about 90 scientific articles. He is from Aanaar / Inari, Sápmi (Finland).

Notes

1. Nils-Aslak, Beaivi, áhčážán.

2. Interview of Nils-Aslak Valkeapää by the author of the article May 25,1994.

3. Heith, “Valkeapää’s Use of Photographs in Beaivi áhčážan,” 41–58.

4. Kalela, Historiantutkimus ja historia, 29–39.

5. See Länsman and Veli-Pekka, ”Saamelaisliikkeen perintö ja institutionalisoitunut saamelaisuus.”

6. Lien and Nielssen, “Absence and Presence,” 295–310.

7. In Finland, the photographs concerning the Sámi have been studied in only a few more general overviews, see Sinisalo, “Three Northern Views”; Sinisalo and Kojo, Kolme Pohjoista, 42–59; about the photography in Northern Finland after the IIWW see Heikka ”Modernin maailman kokijat—pohjoinen dokumenttivalokuvaus 1950-luvulta 1990-luvulle,” 12–64. About the artistic perspective to old photos, see Puranen “Preface”; Edwards, “Essay”; Puranen, Imaginary Homecoming; Lohiniva, ”Ulkopuolella sisällä,” 123–7. About Sámi representations in Finnish photography, Saanio, ”Marja Vuorelainen—Lapin ihmisen kuvaaja”, Vuorelainen, Lapin kuvat, 9–12; Linkola. ”Ihmisten ja porojen maa,” Vuorelainen, Lapin kuvat, 13–31; Ruotsala, “Inkeristä Tenon varrelle,” 4–8; Dölle, “Kirkkoherra kameran takana,” 20–4.

8. See e.g. “Sieivagovat aloitti Talvadaksesta”, Lapin Kansa 22.1. 2002; “Sieivagovat pui saamelaisvalokuvaa” Kaleva 23.1. 2003; “Valokuvan valheen äärellä” Kaleva 23.1. 2003.

9. Lehtola, Saamelaiset suomalaiset—kohtaamisia 1896–1953.

10. See Broberg, “Bakom och framför kameran,” 137–8; Sinisalo, “Three Northern Views,” 44–5.

11. Sinisalo, “Three Northern Views,” 44, 45.

12. Mirzoeff 1999, cited by Heith, “Valkeapää´s Use,” 53.

13. Sinisalo, “Three Northern Views,” 56.

14. Heith “Valkeapää´s Use,” 55 Cathrine Baglo, “From universal homogeneity to essential heterogeneity,” 23–39.

15. See e.g Broberg, “Bakom,” 140; Edwards, “Essay,” 42–6.

16. See Lehtola, Saamelaiset suomalaiset, 110–4.

17. Lehtola, Saamelaiset suomalaiset, 111.

18. See e.g. Ruotsala, “Inkeristä Tenon varrelle”; Dölle, “Kirkkoherra kameran takana.”

19. Lien and Nielssen, “Absence and Presence,” 299.

20. Puranen, “Preface,” 11.

21. About Helander, see Lohiniva, “Ulkopuolella sisällä”; Puranen, “Preface,” 11.

22. Edwards, “Visual Anthropology and alternative Histories.”

23. Heith, “Valkeapää´s Use,” 49.

24. See Lehtola, “´The Right to One´s Own Past´,” 56.

25. Lien and Nielssen, “Absence and Presence,” 303.

26. Interview with Nils-Henrik Valkeapää 15.5. 2006 by the author.

27. Clifford, 156.

28. Mäkelä, “Erkki Mikkola tutki ja kuvasi Pohjois-Suomea,”

29. An interview with an informant from Kaamasmukka, Utsjoki.

30. Puranen, “Preface,” 12; Lehtola, The Sámi People—Traditions in Transition.

31. Deloria, Indians in Unexpected Places, 6.

32. About Sámi Globetrotters, see e.g. Gunnar 1981–82, “Lappkaravaner på villovägar,” 28–9; Vorren, Saami, reindeer, and gold in Alaska; Lehtola, “Sami on the stages and in the zoos of Europe,” 324–52.

33. Jokinen, “Ei mirkki eikä pissi.”

34. Deloria, Indians in Unexpected, 8–10.

35. Broberg, “Bakom,” 142–6.

36. Rosberg, Lappi, 85.

37. Isaksson, Kumma kuvajainen—Rasismi rotututkimuksessa, rotuteorioiden saamelaiset ja suomalainen fyysinen antropologia, 256–7.

38. Isaksson, Kumma kuvajainen, 260.

39. Broberg, “Lappkaravaner,” 28–9.

40. Suomen Kuvalehti 40/1933.

41. About Thomasson, see Utsi, Samefotografen Nils Thomasson; Jonsson, “Samer i bilder—bilder av samer. Ett fotografi och tre berättelser,” 107–20.

42. See Lehtola, Saamelaiset suomalaiset, 188–9.

43. See e.g. Outakoski, “Kolttakylän paastosta kevätmuuttoon,” Kaleva 27. 5. 1934.

44. Oral information from the daughter of Hans-Aslak, Inga Guttorm.

45. Even after the “Suunta on pohjoinen” (Direction: North) exhibition in the Provincial Museum of Lapland, Paadar’s photographs have been rarely seen in public. I myself used them in my work on the historical relations of Sámi and Finns, see Lehtola, Saamelaiset suomalaiset, 206–7 and 358–9. A North Sámi Jouni Antti Helander took a collection of photographs in 1950s and 1960s which were presented in Siida Museum, Inari, in 2000s.

46. Williams, Framing the West. Race, Gender, and the Photographic Frontier in the Pacific Northwest, 138–169.

47. For example, Jouni Piera Jomppanen from Inari preserved the photographs from the Lapp caravan in 1910, touring in Germany and led by his father Juhani Jomppanen, until 1990s. They were published, for example in my article, see Lehtola, “Sami on the stages”.

48. Heith, “Valkeapää´s Use,” 45.

References

- Baglo, C. “From Universal Homogeneity to Essential Heterogeneity: On the Visual Construction of ´The Lappish Race´.” Acta Borealia 18, no. 2 (2001): 1–13. doi:10.1080/08003830108580524.

- Broberg, G. “Lappkaravaner på villovägar. Antropologin och synen på samerna fram mot sekelskiftet 1900.” Lychnos 198182 (1981–82): 28–29.

- Broberg, G. “Bakom och framför kameran. Bilder av samer.” Västerbotten 2 (1997): 137–138.

- Clifford, J. Routes: Travel and Translation in the Late Twentieth Century, 156. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1997.

- Deloria, P. J. Indians in Unexpected Places, 6. Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2004.

- Dölle, S. “Kirkkoherra kameran takana. Juhani Ahola Valokuvaajana.” Raito 2 (2010): 20–24.

- Edwards, E. “Essay.” In Imaginary Homecoming. Kuvitteellinen kotiinpaluu, edited by J. Puranen. Oulu: Pohjoinen, 1999.

- Edwards, E. 2003: “Visual Anthropology and alternative Histories.” Unpublished paper in a seminar Sieivagovat in January 23, 2003, Inari, Finland.

- Heikka, E. “Modernin Maailman Kokijat – Pohjoinen Dokumenttivalokuvaus 1950-Luvulta 1990-Luvulle.” In Pohjoinen Valokuva, edited by J. Järvinen, A.-L. Räisänen, P. Siitari, and J. Vilkuna, 12–64. Oulu – Inari: Pohjoinen Valokuvakeskus, Kustannus-Puntsi, 2000.

- Heith, A. “Valkeapää’s Use of Photographs in Beaivi Áhčážan: Indigenous Counter-History versus Documentation in the Age of Photography.” Acta Borealia 31, no. 1 (2012): 41–58. doi:10.1080/08003831.2014.904996.

- Isaksson, P. Kumma kuvajainen - Rasismi rotututkimuksessa, rotuteorioiden saamelaiset ja suomalainen fyysinen antropologia, 256–257. Inari: Kustannus-Puntsi, 2000.

- Jokinen, E. “Ei mirkki eikä pissi.”Utsjoen elämää entisaikaan. Oulu: Pohjoinen, 1996.

- Jonsson, J. “Samer i bilder – bilder av samer. Ett fotografi och tre berättelser.” In För Sápmi i tiden. Nordiska museets och Skansens årsbok, 107–120. Edited by Christina Westergren and Eva Silvén. Stockholm: Nordiska museet, 1997.

- Kalela, J. Historiantutkimus ja historia, 29–39. Helsinki: Gaudeamus, 2000.

- Länsman, A.-S., and V.-P. Lehtola. “Saamelaisliikkeen perintö ja institutionalisoitunut saamelaisuus.” In Saamenmaa. Kulttuuritieteellisiä näkökulmia, edited by V.-P. Lehtola and U. P. J. H. Snellman. Helsinki: Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seura, 2012.

- Lehtola, V.-P. The Sámi People – Traditions in Transition. Fairbanks: University of Alaska Press, 2004.

- Lehtola, V.-P. “‘The Right to One’s Own Past’. Sámi Cultural Heritage and Historical Awareness.” In The North Calotte. Perspectives on the Histories and Cultures of Northernmost Europe, edited by M. Lähteenmäki and P. M. Pihlaja, 56. Inari: Kustannus-Puntsi Publishing, 2005.

- Lehtola, V.-P. Saamelaiset Suomalaiset – Kohtaamisia 1896-1953. Helsinki: SKS, 2012.

- Lehtola, V.-P. “Sami on the Stages and in the Zoos of Europe.” In L´Image du Sápmi II. Études compares. Edited by Kajsa Andersson, 324–352. Örebro: Örebro University, 2013.

- Lien, S., and H. Nielssen. “Absence and Presence: The Works of Photographs in the Sami Museum, RiddoDuottarMuseat-Sámiid Vuorká-Dávvirat (RDM-SVD) in Karasjok, Norway.” Photography and Culture 5 (2012): 295–310. doi:10.2752/175145212X13415789392965.

- Linkola, M. “Ihmisten ja porojen maa.” In Lapin Kuvat, edited by M. Vuorelainen, 13–31. Helsinki: SKS, 1992.

- Lohiniva, L. “Ulkopuolella sisällä: saamelaisuus Marja Helanderin valokuvataiteessa.” In Pohjoiset identiteetit ja mentaliteetit 1: Outamaalta tunturiin, edited by M. Tuominen, M. Autti, and V.-P. Lehtola, 123–127. Rovaniemi – Inari: Lapin yliopisto – Kustannus-Puntsi, 1999.

- Mäkelä, R. “Erkki Mikkola tutki ja kuvasi Pohjois-Suomea.” Kaleva 6 (newspaper), no. 12 (2007).

- Nils-Aslak, V. Beaivi, áhčážán. Kautokeino: DAT, 1988.

- Puranen, J. Imaginary Homecoming. Kuvitteellinen kotiinpaluu. Oulu: Pohjoinen, 1999.

- Rosberg, J. E. Lappi, 85. Helsinki: Kansanvalistusseura, 1911.

- Ruotsala, H. “Inkeristä Tenon Varrelle. Antti Hämäläinen Lapin Kuvaajana.” Raito 2 (2003): 4–8.

- Saanio, M. “Marja Vuorelainen – Lapin Ihmisen Kuvaaja.” In Lapin kuvat, edited by M. Vuorelainen, 9–12. Helsinki: SKS, 1992.

- Sinisalo, H. “Three Northern Views.” In Kolme Pohjoista. Three Northern Views, edited by H. Sinisalo and R. O. Kojo, 42–59. Tampere: Vapriikki, 2005.

- Utsi, J. E. Samefotografen Nils Thomasson. Östersund: Jamtli förlag, 1997.

- Vorren, Ø. Saami, Reindeer, and Gold in Alaska. The Emigration of Saami from Norway to Alaska. Prospect Heights: Waveland Press, 1994.

- Williams, C. J. Framing the West. Race, Gender, and the Photographic Frontier in the Pacific Northwest, 138–169. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.