ABSTRACT

This article explores how photographs of Sámi peoples were used in the context of Norwegian physical anthropology in the interwar period, but also how they are re-appropriated in the Lule Sámi community in Tysfjord today. It also demonstrates how photography as used in in the Norwegian racial research publications, although designed to highlight physical characteristics, also include references to cultural characteristics and context. Such inclusion of cultural markers and contextual information may be understood as a strategy to overcome the failure of the scientific community to isolate race as a biological fact. The photographs worked to secure “evidence” where evidence could not be found. This strategy is based on the abundancy, or excess of meaning, of the photographic image as such. The article argues that it is precisely this photographic excess that is the key to understanding why and how photography contributed to establish credibility to a scientific discipline in continuous struggle and with frequent breakdowns. The abundancy, or photographic excess, is also a key to understand how photographs that once were used as instruments of racial research, over time have undergone a series of transmutations of functions and meanings. Thus, racial photographs may acquire new meanings when circulating in time and space.

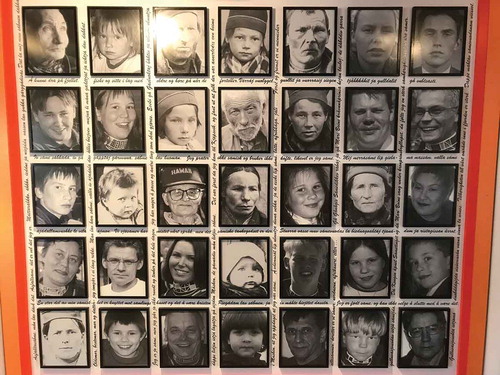

“I am born Sámi, and cannot choose not to be”—racial photographs in a Sámi cultural centre

In the main hall of Árran Julevsáme guovdás, the Lule SámiFootnote1 Centre in Tysfjord, northern Norway, there is a wall-size montage of thirty-five enlarged black and white photographic portraits depicting members of the local Sámi community (). The montage is mounted in a solid wooden frame painted in Sámi signal colours, vibrant yellow and red. Centrally positioned, it serves as an introduction to the exhibition area. The images show children, young, adult and elderly people of both sexes, some with, others without, local Sámi costumes. At first sight, the photographs seem to be of recent date. However, some of the portraits are in fact of older date, although technically manipulated to resemble the more recent ones. These older photographs originate from racial research expeditions to the Tysfjord area in 1914 and 1921, carried out by the head of the Department of Anatomy and professor in physical anthropology, University of Oslo, Kristian Emil Schreiner, his wife Alette Schreiner and their colleague, Dr. Johan Brun. They were once used as tools in the search for, and documentation of, the so-called lapponoid race.

Figure 1. Photographic montage consisting of racial photographs from the original Schreiner Collection at the Department of Anatomy, and contemporary portraits of unnamed Sámi individuals, all from the Tysfjord area (photographer unknown), situated in the entrance hall of the Lule Sámi Centre. Photograph reproduced with permission from Árran Julevsáme guovdásj/The Lule Sámi Centre.

In the montage of these old and new photographs, the portraits are framed by quotations in “handwritten” fonts; utterances such as: “when the king opened the Sámi parliament, I felt a strong Sámi identity”; “we Sea-Sámi have lost our language, but our cultural ideas are there”; “I am born Sámi, and cannot choose not to be”; or “I do not speak Sámi and do not wear Sámi clothes, but I am still Sámi”; and “yes, I am Sámi, but I do not think about it all day. I have children to take care of and other things to do”. These quotations originate from interviews with members of the local population conducted by the museum staffs. According to the museum staffs, the montage is used as a point of departure for talking with visitors about the abuse and oppression inflicted on the Sámi peoples by the majority society, including the governmental policy of Norwegianization and the resulting losses of language, identity and memory.Footnote2 The museum staffs also point to how memories of the racial research expeditions remain painfully vivid among the locals in the area. The way family members were photographed, undressed and measured by strangers from the South of Norway, is still something that people talk about.Footnote3 The centre acquired the collection of photography from the Schreiner couple’s racial expeditions in 1914 and 1921 only a few years ago. The material that documents the actions that inflicted the painful memories, is thus now in Sámi possession. The installation exemplifies how the local community is in a process of re-appropriating the photographs and putting them into use in new ways with new meanings.

The photographs have what Elizabeth Edwards has labelled a social biography. She emphasizes how the photographs’ “[s]ocial efficacy is premised specifically on their shifting roles and meanings as they are projected into different spaces to do different things (Edwards Citation2012, 222). As already indicated through the presentation of the photographic installation at Árran, the social biography of the photographs from the Schreiner expeditions is a story of a trajectory involving radical shifts in photographic meaning. This article is a closer exploration of these shifts in meaning. How is it possible that photographs that originally were used to document racial specificity and inferiority now work as markers of identity and pride in a Sámi cultural centre? Let us start with the beginning, which brings us to the research environment of physical anthropology in Norway before World War II.

Racial mapping of Norway

The historian Jon Røyne Kyllingstad is responsible for the major research contribution on the development of physical anthropology in Norway in the interwar period. He describes it as partly motivated by the quest to determine the racial constitution of the Norwegian population. This enterprise was fuelled by international research trends as well as by the nationalist sentiments of a young nation, politically independent only since 1905 (Kyllingstad Citation2014a). Kyllingstad notes how physical anthropologists conducted research on carefully selected population groups, with particular attention given to the Sámi people.

He also explores the institutional frames of this research activity, with its networks and connections in Norway and abroad. Until 1946 the University in Oslo was the only university in Norway. Much scientific research took place outside the university context, also within the field of physical anthropology, racial research and eugenics (Kyllingstad Citation2014a). Individual researchers and privately funded research institutes maintained close contact with the university, and the ties between Norwegian researchers and international research environments, in particular in Sweden and Germany, were close. The Department of Anatomy formed a main centre of Norwegian physical anthropology. Kristian Emil Schreiner was the head of the Department of Anatomy between 1908 and 1945. Although not formally employed by the department, Schreiner’s wife, Dr. Alette Schreiner worked closely with her husband, and they both published a series of monographs and articles on the racial constitution of the Norwegian population.

They were also the first to carry out more systematic physical anthropological investigations among the Sámi population than earlier predecessors, such as for instance Roland Bonaparte (see Lien’s article in this issue). Apart from a few early instances, physical anthropology had mainly focussed on southern Norway. Thus, at the time when the Schreiner couple initiated their research, Northern Norway remained a white spot on the racial anthropological map.

The sudden urge to study the Sámi population by this and other research communities, Kyllingstad argues, should be seen in a broader political perspective. On a political level, he holds, two matters in particular created a demand for more knowledge of the Sámi population (Kyllingstad Citation2014b). First, there were several cultural and territorial disputes connected to the Sámi, such as conflicts about reindeer pastures following the Norwegian independence from the Swedish- Norwegian union in 1905. This actualized physical anthropological research connected to an interest in the Sámi peoples’ historical affiliation to the Norwegian territory. Secondly, the growth of the eugenic movement contributed to put the racial biology of the Sámi people on the agenda. In a broader perspective, the exploration of the nation’s racial identity and origin was intertwined with the young nation’s ongoing academic, political and cultural debates on Norwegian national identity (Kyllingstad Citation2014a). In this climate, racial research on the Sámi formed part of a broader research on the peoples of Norway.

The Schreiner couple and their colleague Halfdan Bryn published several studies based on research on the population in various parts of Norway in the Interwar period. A large-scale collection of data on army conscripts from the whole country collected by army physicians between 1919 and 1923, involved anthropometric examination including photography of the young soldiers. The photographs of the army conscripts reappeared in a number of subsequent publications by the Department of Anatomy. The research on army conscripts were supplemented by studies of selected communities in particular areas in order to explore the racial composition of the Norwegian population, believed to vary between a short sculled dark alpine type, and a long sculled blond type, the supposedly original Nordic master race. Specific areas were selected because they were assumed to host particularly “pure” concentrations of these types (Kyllingstad Citation2014a). Thus, one of Alette Schreiner’s publications, the monography Anthropologische Lokaluntersuchungen in Norge: Valle, Hålandsdal und Eidfjord from 1929, was based on research carried out in areas in inner southern Norway considered as centres of the long-sculled blond race.

A few years later, in 1932, Alette Schreiner published a second monography in the same series, Anthropologische Lokaluntersuchungen in Norge: Hellemo (Tysfjordlappen). Among the Sámi groups studied by the researchers at the Department of Anatomy, the choice to focus on the Lule Sámi in Tysfjord in northern Norway was based on the presumption that this group had lived more isolated than other Sámi peoples (Schreiner Citation1932). They had to a larger extent kept their language and Sámi costumes, and were considered to be less integrated into the Norwegian society than other Sámi groups. It was therefore assumed that this group was of purer Sámi descent than the rest of the Sámi peoples, and that they had physical features that distinguished them from the surrounding Norwegian population (Evjen Citation2000). As part of the racial mapping of Norway, these studies were later complemented by studies from several other regions, including the Finnmark County that had the largest concentration of Sámi peoples. Rolv Gjessing, a student of Kristian Emil Schreiner and a medical doctor and psychiatrist, published the monograph Die Kautokeinolappen: eine anthropologische Studie in 1934. The same research environment carried out systematic research on the skeletal remains of the Schreiner collection. Kristian Emil Schreiner published his major two-volume work Zur Osteologie der Lappen 1931/1935.

As Kyllingstad shows, the larger frame of this racial mapping may be summed up as the quest for the Nordic master race (Kyllingstad Citation2014a). Initiated by the founder of the Swedish Institute of Racial Biology, Hermann Lundborg, this research was designed as a joint Nordic venture. Fuelled by ideas of racial purity as the highest biological and aesthetic attribute, as well as by notions of racial hierarchy, the research rested on notions of Nordic superiority and Sámi racial inferiority. The Norwegian partners in this venture were the Schreiner couple and their colleague Bryn. The assumption that the Nordic race was a dominating element in the population, which Norwegian scholars in the beginning shared with their Swedish colleagues, was further nurtured through influence from German racial anthropology and racial ideology. In Norway, racial determinism and Social Darwinism held a strong position until the 1920s but lasted much longer in Sweden. The Swedish project, which was far more systematic and comprehensive than the Norwegian branch, resulted in the three-volume work The Racial Characters of the Swedish Nation (Lundborg, Linders, and Wahlund Citation1926). According to Kyllingstad, the Swedish project was considered as a success at the time, while the Norwegian results appeared as fragmented and disputed.

As Kyllingstad shows, the making a racial map of Norway ended with a profound schism between the Schreiners and Bryn (Kyllingstad Citation2014a). The division of the Norwegian research community connects to increasing international critique of radical racist ideas. This wave of criticism evolved in particular in the English-speaking world, partly as a response to Nazi Germany. While Bryn maintained a close connection to Germany until he died in 1933, he become gradually more marginalized in the Norwegian academic environment. Thus, while the Swedish proudly proclaimed that they had the highest percentage of the Nordic race in the world, the Norwegian researchers reached other conclusions. The Schreiner couple had for example become increasingly sceptical towards the idea of a Nordic master race. Notably, in the second volume of his Cranica Norvegica, published in 1946 at the end of his career, Kristian Emil Schreiner concluded that the Nordic race derived from the merging of different groups and was nothing but a product of racial mixing (Schreiner Citation1946, Kyllingstad Citation2014a, 222). He did not denounce the concept of “race”. Nevertheless, this marks the beginning of a process where “race” lost its validity as a scientific term in the Norwegian context.

Schreiner came to similar, but also different, conclusions in his research on the Sámi peoples. The Sámi, he claimed, were also a product of the merging of different groups. However, by arguing that he had identified a primordial lapponoid element in the racially mixed skeletal material, he maintained the existence of a prehistoric, primordial Sámi (Lappish) type (Schreiner Citation1935; Kyllingstad Citation2014a).

The way the Schreiner couple developed, redefined and sometimes also rejected concepts and theories through their careers is typical to the field of racial research. As racial science evolved, theories, scientific concepts, and categories multiplied. The research field expanded with different and opposing positions, marked by internal inconsistencies and frequent theoretical breakdowns. Throughout their research the Schreiner couple came to renounce many of the past and contemporary theories and assumptions of racial research. They took an explicit stance against radical eugenics and the racial ideology of Nazism (Kyllingstad Citation2014a, 215–217). Based on their own findings, they argued against the existence of racial purity, and held that both Norwegians and the Sámi were products of complex and long-time merging. For instance, their research on the Lule Sámi in Tysfjord concluded that it was more difficult to find original racial characteristics than initially assumed. Neither did the proposed predominant Nordic population of inner southern Norway (Valle, Hålandsdalen and Eidfjord) confirm with the ideals of the Nordic type.

Photography as evidence: the racial imaginary

As observed by Kyllingstad, the main source material for these physical anthropologists was collected skeletons, supplemented by detailed measurements and meticulous notes of physical characteristics of living human bodies. He also mentions how they invested in building a photographic archive. The researchers attached to the Department of Anatomy were not the first to use photography as a research tool in physical anthropology in Norway. However, the Schreiner couple, together with their partners Johan Brun and a military doctor based in Trondheim, Halfdan Bryn, were the first to use photography more systematically and in a large scale (Evjen Citation2000; Kyllingstad Citation2014a). While a closer analysis of the photographs themselves is not included in Kyllingstad’s discussion, Bjørg Evjen has researched the Schreiner couple/Brun’s photographic practices more closely. She has also studied how members of the local population in Tysfjord remember being photographs and measured (Evjen Citation2000). As she observes, both Alette Schreiner and Brun photographed extensively during the research expeditions. A closer look at the collection today as it appears in copies at Tromsø Museum, Archive Nordland in Bodø, and the few left at the Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Division of Anatomy, University of Oslo, reveals how the Schreiner couple/Brun also complemented their own photographs by images from other sources. A major source was photographs of army conscripts. In addition to their own photographs from Sámi communities, their collection comprised images by the ethnographer Ole Solberg, who at the time was professor and director of the Ethnographic Museum in Oslo. Drawing on both Kyllingstad and Evjen’s research contributions, that among other things demonstrate the shortcomings and inconsistencies of racial research, I will argue that photography was used strategically to support the credibility of their scientific venture.

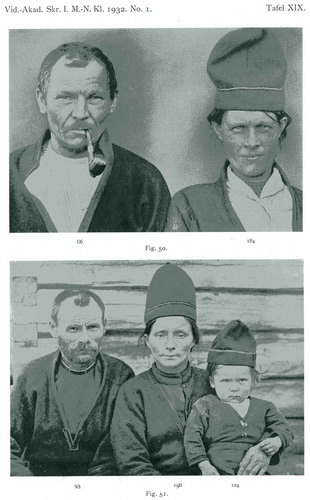

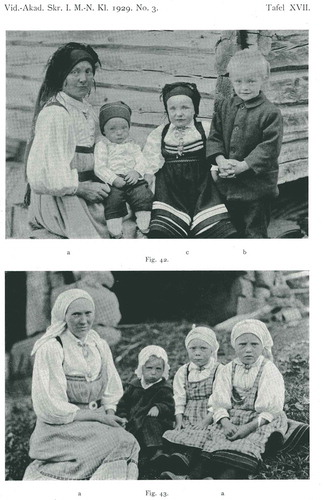

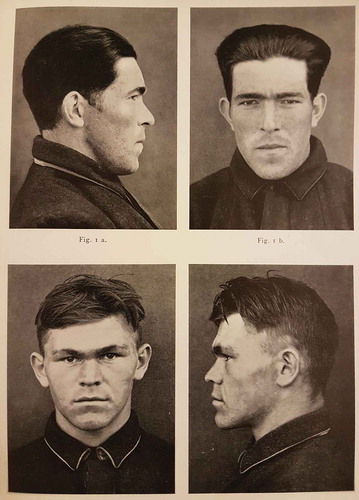

Let us now turn back to the racial type photographs in the two monographs by Alette Schreiner, the one on Tysfjord in the North, and the other from Valle, Hålandsdal and Eidfjord in the South of Norway. In both books, the subjects are photographed outdoors in the setting of their native landscape, and in local costumes. The landscape element is more emphasized in the Tysfjord volume, where the local Sámi are depicted against the background of the sublime, northern landscape situated on the outskirts of civilization (). Both areas were perceived as marked by a higher degree of racial purity. Nevertheless, the portrayed subjects in both volumes are posing in costumes that accentuate ethnic and local affiliation more than physical features (). The photographs used in these two volumes are remarkably different from the photographs in for example the study from Rogaland county that uses anthropometric portraits of army conscripts (Schreiner,Citation1941, Citation1951) ().

Figure 2. Facsimile from Alette Schreiner, Anthropologische Lokaluntersuchungen in Norge: Hellemo (Tysfjordlappen), Oslo: Det Norske Vitenskaps-akademi. 1932, Tafel XIX, fig. 50 & 51.

Figure 3. Facsimile from Alette Schreiner, Anthropologische Lokaluntersuchungen in Norge: Valle, Hålandsdal und Eidfjord, Oslo: Det Norske Vitenskaps-akademi, 1929, Tafel XVII, fig. 42 & 43.

Figure 4. Facsimile from Karl Emil Schreiner. Bidrag til Rogalands Antropologi. Oslo: Det Norske Vitenskaps-akademi, 1941, . Nr. 438. Ryfylke & . Nr. 207. Stavanger.

The photographs in Alette Schreiner’s monographs from Tysfjord differ considerably from the earlier ideals of the anthropometric photograph. The anthropometric photograph was originally intended to eliminate disturbing details of gesture, expression, culture, or context from portraits of natives, in order to reveal the underlying details of cranial structure and “race” (Maxwell: 2010, 10) . As Debora Poole formulates it, “[f]rom its beginnings, race was about revealing—or making visible—what lay hidden underneath the untidy surface details—the messy visual excess—of the human, cultural body.” (Poole Citation2005, 164). In contrast to ethnographic photographs, racial photographs should omit disturbing elements of context and culture, in favour of a mere focus on physiognomy (Edwards Citation2001; Poole Citation2005). As we have seen, Alette Schreiner’s portraits do not conform to this ideal. In fact, they frequently expose ethnographic details and contextual surroundings. They are by no means void of reference to place, time, and context. Often, people wear local costumes, and are posited against the background of site-specific houses and dwellings.

Although photography was a scientific tool in an anthropometric project, and the photographs were aimed to serve as visual scientific evidence of racial physiognomy, contextual and ethnographic details seem to have become more important, or perhaps even more important than bodily shape. Racial specificity or “purity”, it appears, could only be made visible and irrefutable through showing where and how people live and dress. Ironically, although race was seen as an indisputable biological fact, it could only become evident through expressions of cultural particularities. This odd tension seems to be a particular feature of the development of racial photography. Amos Morris-Reich describes this tension as being “between belief in ‘race’ as stable and observable on the one hand and as increasingly fluid and concealed on the other” (Morris-Reich Citation2016, 3).

There are significant contrasts between the use of photographs in Alette Schreiner’s books and the earlier mentioned Swedish work The Racial Characters of the Swedish Nation from 1926. While the Swedish volume also makes extensive use of individual and group portraits, often in folk costumes as in Schreiner’s books, it has in addition a large number of full-figured anthropometric nudes.Footnote4 In fact, the photographic material in this work is remarkable varied in both style and performance. The lack of consistency in the photographic approach stands in sharp contrast to the rigid and schematic approach of the research programme with all its statistics, schemes and tables. The photographic inconsistency could be explainable in terms of the many different photographers involved. However, considering the meticulous and uniform methodology that characterized all other dimensions of the research methods applied, this explanation seems not fully satisfactory. This lack of photographic stringency also signals a pragmatic and multiple use of photographs in order to fill the scientific voids. Ulrika Kjellmann argues in her discussion of the use of photographs in the scientific practice of the Swedish State Institute for Race Biology, that the photographs served to manipulate and bias the data (Kjellman Citation2014). The pictorial rhetoric supported the researchers’ ideas and ideology in ways that the stricter research methods and data would have prevented. Nude poses proved insufficient as scientific evidence. Thus, photographs showing aspects such as clothing, environment, expressions and postures could outweigh photography’s failure to capture shared biological traits within a race group. In this way, the multiple and inconsistent manners in which people are depicted expose the methodological inconsistencies within this scientific venture. Kjellmann’s observation also applies to the Schreiner couple’s research on the Sámi peoples. Photography could potentially support the image of racial difference and the inferiority of the Sámi, when biometrics failed.

For the Schreiners, the superiority of Norwegians or Europeans over the inferior Sámi peoples was self-evident. However, hierarchy, superiority and inferiority could neither be confirmed through measuring living people, nor through the careful examination of bones. Photographs, then, became tools aimed at visualizing invisible or more hidden characteristics of race, through the materialization of assumed social, spiritual and mental capacities. The Schreiner couple believed, as many scholars of race had done before them, such as Roland Bonaparte, Gustaf von Düben or Sophus Tromholt to mention some of the most prominent examples (see Lien in this issue, Larsen and Lien Citation2007, 168–174), that the Sámi people belonged to the childhood of human kind. As Karl Emil Schreiner says about the psychological constitution, typical mentality, and general attitude of the Sámi in his work Zur Osteologie der Lappen:

The carelessness often encountered among the Lapps, sometimes with a childish confidence, sometimes with great shyness, and not quite seldom with a complete irresponsibility, agrees with the somatic type, and directs the thoughts towards the protomorphic races of Eurasia (Schreiner Citation1935, 286).

Except from photographs of skeletons and excavation sites, only one photograph in this two-volume work depicts a living human being. On the front page, there is a portrait of an old weathered-faced woman with untidy hair, used, perhaps, to underline the wild unruliness of a people of the outskirts of civilization. In a similar vein, Alette Schreiner writes in her study of the Lule Sámi in Tysfjord:

As is often the case with primitive people, most of our Lapps, in spite of their childlike curiosity and friendliness, were reluctant to submit themselves to an accurate examination, especially when it came to undressing the body. (…). By using small gifts, it was possible to get most of them to submit themselves to a more or less thorough examination; not infrequently, it was necessary to resort to mild force (Schreiner Citation1932, 13).

This way of pointing to invisible physical (such as the “lapponoid” element), or psychic distinctions (mental capacity), visualized and emphasized through the photographs’ reference to external and visible distinctions such as cultural emblems (clothes, habitat), or social inferiority (unruly hair, dirty working clothes, weathered face), shows how desperately racial theorists sought to re-establish order in a racial chaos that they themselves uncovered through anthropometric research. As Morris-Reich formulates it:

What happens when identification based on inherent, genetically transferred, foolproof racial principles proves defective? To those committed to racial principles, these “inconvenient realities” do not alter the fixation of their principles but rather give rise to attempts to fine tune their distinctions and definitions and to overcome the obstacles in reality. Particularly important is the gradual replacement of physiognomy by internal, often latent, indicators not easily applied to identification and representation (Morris-Reich Citation2016, 24).

The concept of race was never only about visible difference, but also about hidden, deeper, and often disturbing qualities. And the photographically emphasized visible differences were used to signal the deeper structures of race that remained hidden and undetectable. No comparative osteology and analyses of hair structure, nose profile, eye shape or colour could uncover these profound and essential layers. While bone structures and bodily features never could verify assumptions of mental capacity, moral conduct or racial inferiority, the photographs made it possible to bypass the faults of science through a visual rhetoric that both evoked and played on the cultural stereotypes and convictions active at the time. The continuous failure to isolate race as a biological fact is precisely what made photography so important in this context.

Photographic instability and transformations of meaning

Today however, the use of photographs in the Schreiner couple’s publications no longer works as a convincing cover-up of the inconsistencies between their basic theses, research observations and conclusions. Instead they contribute to highlight scientific failure, and how racial science typically refrained from drawing a clear line between physical, bodily, or cultural attributes (Morris-Reich and Rupnow Citation2017).

The Schreiner couple increasingly became aware of the limits of their own research methods, or, as we might phrase it today, they failed to validate their research hypotheses. Nevertheless, even though they recognized the complexity of the reality they were investigating, and moderated their hypotheses accordingly, they never abandoned the idea of race. While their own research in practice failed to prove the existence of race and (“degenerated”) racial purity, they remained committed to the notion of race and racial hierarchy throughout their careers (Kyllingstad Citation2014a). The Schreiner couple argued in their works against other researchers on scientific grounds, and frequently pointed to the way others exceeded the limits of science in their methods, findings and conclusions. Nevertheless, in spite of their commitment to strict and rigid scientific methods, the Schreiners also exceeded the frame of their own scientific methodology and its evidentiary requirements. Their paradoxical use of photography is one example of such transgressions. In this they conformed to the general tendency in this line of research, which is the main reason why racial science today is often labelled pseudoscience.

Photographs, apparently, increased their value to racial research, at the moment when the science was on the verge of collapse. Although the photographs failed to demonstrate typical racial features, they still contributed to bring forth and manifest “race” in cultural terms, which as a phenomenon continued to remain elusive within the parameters of biometrics. Ironically, although physical anthropology had come to distrust photography as a means of documentation of accurate measurement, the photographic medium maintained, and even increased its central position and truth-telling power in the study of human difference, at a time when the concept of race gradually became replaced with “culture” and “ethnicity” (Möschel Citation2011). Photography was deemed unsuitable as a biometrical instrument. Yet, it remained useful to racial researchers because of the its asserting power, founded in a belief in its indexical integrity. Or, as John Roberts argues, “[P]hotography is the very act of making visible and, therefore, is conceptually entangled with what is unconscious, half-hidden, implicit” (Roberts Citation2014, 2). The truth-claiming force of photography was vital to the process of naturalizing and making real the racial imaginary.

However, when the racial imaginary in which the photographs were inscribed crumbled, they lost their truth-value as racial evidence. As Roberts formulates it, “the photograph’s claims on the indexical truth of a given moment is always governed by the position of the photograph within an imaginary continuity before and after the photograph is taken” (Roberts Citation2014, 151). This is the photographic paradox; the photograph’s ability to fixate truth while simultaneously being uncertain and unstable (Roberts Citation2014, 152).

There is an ambiguity in the use of photography as scientific evidence in racial science. This ambiguity is connected to the earlier mentioned abundancy of the photographic material (Edwards Citation2015). This photographic excess is the key to understanding why and how photography contributed to establish credibility to a scientific discipline in continuous struggle, and with frequent breakdowns. But it is also this excess that makes it possible to open up the images for new meanings in new contexts. Roberts’ notion of the social ontology of photography is helpful in order to understand how such shifts are possible:

Photography […] in its overwhelming embodiment as a social relation between photographer, world, image, and user, is an endlessly englobing and organizational process in which representations of self, other, “we”, and the collective are brought to consciousness as part of everyday social exchange and struggle (Roberts Citation2014, 5).

While racial theory collapsed after World War II, Schreiner and Brun’s photographs have gained an archival afterlife and new meanings in the museum context.

Archives, controversies and repatriation

Most of the photographs of the Sámi peoples that once formed part of the photography archive of the Schreiner Collection (named after Kristian Emil Schreiner) at the Department of Anatomy, have since WW2 been transferred to other archives. They are now to found in the archives of Tromsø Museum, where the images were incorporated into the photography archive of the cultural history collections, and more recently, in the Archive Nordland in Bodø, and the Lule Sámi Centre Árran in Tysfjord.Footnote5 Tromsø Museum discovered as late as in June 2017 that their archive holds a large collection of original glass plates, in addition to the already known paper positives. Both the paper positives and glass plates were acquired during the 1970s, as part of the museum’s systematic collection of ethnographic photographs from the northern region.Footnote6 Only a few are of the photographs from the Schreiner Collection are now left in the archive of the Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Division of Anatomy, University of Oslo.

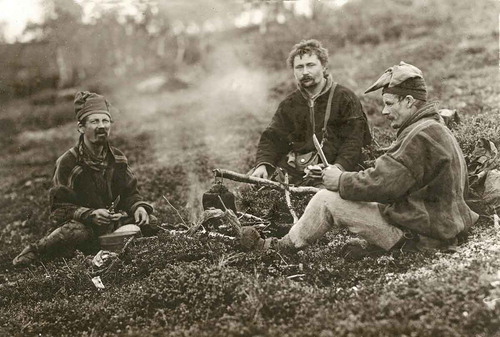

Many of Schreiner and Brun’s photographs in the collections show scenes from Sámi daily life in a way that direct the attention towards livelihood and cultural characteristics more than towards physical or “racial” features (). Thus, a large proportion of this material is very similar to its contemporary ethnographic collections. This in itself suggests that the line between racial and ethnographic photographs is not easily drawn. The material is characterized by diversity in genre, ranging from landscapes, expedition photographs and ethnographic scenery to group and individual portraits.

Figure 5. Ethnographic photograph originating from the Schreiner Collection. Photographer: Alette Schreiner. Published with permission from Tromsø Museum—University Museum.

Why and how the photographs originating from the Schreiner Collection at the Department of Anatomy was dissolved is uncertain. However, the dispersion of the photographic archive indicates that the material it contained had been subjected to a process of redefinition even before the ongoing process of Sámi re-appropriation. The collection of photographs acquired new functions and meanings as historical and ethnographic documentation of the Sámi peoples. These transmutations of photographic meaning can be seen in relation to ideological changes and shifting historical actors engaging with the photographs through time.

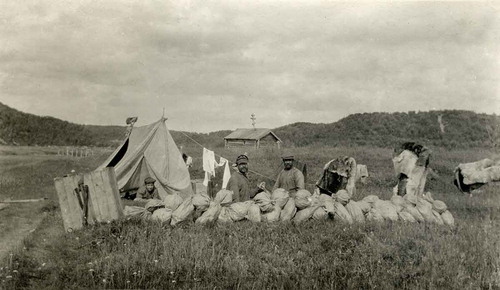

The copies of the photographs from the Schreiner Collection arrived Árran almost by accident. The director, Lars Magne Andreassen, received a phone call from NIKU, The Norwegian Department of Cultural Heritage Research, where some boxes with photographs had been found during a clean-up. Noticing that the images were from the Tysfjord area, the staff thought they might be of interest to Árran .Footnote7 Thus, the return of the images was not a result of a conscious repatriation policy prompted by the Norwegian government. As mentioned in the introduction, the photographs from the Schreiner Collection epitomize the abuse and oppression committed by the Norwegian government and majority society. Not only do the images originate from humiliating encounters where people were subjected to racial research by researchers who saw them as racially inferior. This research history also includes desecration of holy grounds and the removal of ancestors from burial sites and church yards, as the Department of Anatomy also actively collected skeletons.Footnote8 The Schreiner/Brun photographic production even contains a series of expedition photographs, which shows the researcher team’s triumphantly displaying freshly excavated Sámi remains, gathered in large sacks in the churchyard in Neiden ().

Figure 6. Expedition photograph from the excavations in Neiden, Finnmark in 1915. Photographer: Johan Brun. Published with permission from Tromsø Museum—University museum.

In contrast to the dispersion of photographs, the collection of skeletons still largely remains at the Division of Anatomy, University of Oslo. The collection comprises more than 8000 archaeological and other skeletal finds, of which a collection of Sámi remains of about 1000 individuals (Sellevold Citation2014). However, during the last decades the archive has been surrounded by much controversy, which in itself speaks about the contemporary political and emotional context of the photographs in question. While the Schreiner collection once brought Kristian Emil Schreiner and the Department of Anatomy much honour and fame, for the Sámi peoples it first and foremost materializes a painful history of oppression and abuse, as well as violations of religious beliefs.Footnote9

Members of the Sámi population made the first reburial claims in the 1980s. The reluctance, or more precisely, active resistance, of the division of Anatomy to return the remains resulted in a heated and long-lasting public debate. From a Sámi point of view, the remains belong to the descendants and the local community from which they were once taken.Footnote10 The staffs at the Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Division of Anatomy, on their hand, maintained that the collection of Sámi human remains ideally should stay in Oslo and be available for future research. Furthermore, they have also been reluctant to recognize the physical anthropological expeditions as a form of abuse. As Dr. Gunnar Nicolaysen, former head of the Department of Basic Medical Science, formulated it in a television interview: “Since our people had all the necessary authorizations from the government, it is difficult to see that it was abuse” (Broadcast on Norwegian national television in 2007, www.nrk.no/troms/). In the same broadcast, the prominent politician and former president of the Sámi Parliament Aili Keskitalo characterized the excavation as a disgrace to Norwegian research history. She also held as important that the contemporary research environment contributes to secure the restauration of honour and human dignity to the Sámi community.

A long struggle culminated by the end of the 1990s, when the University Council ordered the Department to return the remains to the authority of the Sámi Parliament. The process of returning the remains and reburials is still ongoing. The Department of Basic Medical Sciences maintains the administrative responsibility of the collection, but the Sámi Parliament has the right to claim all Sámi human remains if they should wish so. All remaining Sámi skeletal materials in the collection is under restricted access, stored and treated according to particular regulations. Permission to study the collection must be authorized by the Sámi Parliament.

For the Sámi community, the importance of submitting the collection to Sámi control not only concerns issues of the return and proper and dignified treatment of ancestral relatives. In a larger perspective the questions related to the Schreiner collection, the photographs included, is about obtaining ownership over their own history and heritage. Equally important has been the wish from the Sámi community to gain control of future research in order to secure ethical management of the collection and avoid future repetitions of abusive and offensive research practices. The regulations apply not only to the human remains, but also to the rest of the Sámi-related part of the Schreiner Collection, including photographs as well as written materials.Footnote11

Conclusion

Let us finally return to the photographic installation in the entrance hall of Árran (), which not only is about gaining control and ownership of a difficult photographic heritage. It is also a way of inscribing the images into new practices of self-representation. By literally evening out the differences between old and new photographs, between images taken by outsiders and photographers within the Sámi community, framing the images with bright Sámi colours as well as Sámi statements, the montage deprives the outsiders of their power to confine Sáminess. The images of historical and contemporary individuals form a community and shared Sámi identity across time and space. The way Árran make use of, and re-appropriate historical photographs taken by outsiders, forms part of a larger Sámi effort going on many places in Sápmi (see Veli-Pekka Lehtola, this issue, Lien and Nielssen Citation2012).

Thus, both the social biography and the complex of social relations and processes of which they form a part help explaining how the Schreiner and Brun photographs’ role and meaning could change. Initially they functioned as representations of racial specificity and inferiority. Then they became ethnographic documentation stored and used in museums, before they changed again by gaining value as historical documentation of an unsettled past and by serving as memorials of traumatic experiences of oppression and abuse. Finally, today the photographs are reclaimed and engaged in processes of restoring dignity and subjectivity.

Lastly, photographs always include a certain abundancy, a surplus or excess. They can never be fully contained, even when serving as instruments of abuse, objectification and subjugation. This is why the faces in the photo-montage in the entrance hall of Árran, the Lule Sámi Centre in Tysfjord, do not appear as victimized and objectified, but as vivid subjectivities speaking of their own experiences on their own terms.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Hilde Wallem Nielssen

Hilde Wallem Nielssen is Associate Professor at NLA University College, Bergen, Norway. She holds a Ph.D in Social Anthropology from the University of Bergen, Norway. Her research ranges from to spirit possession rituals in Madagascar to photography, museums and colonial culture. Colonialism, post-colonialism, representation, aesthetics and the study of visual cultural forms have been central to all her research. Her publications include Ritual Imagination. Tromba possession among the Betsimisaraka of Eastern Madagascar (Brill 2012); Protestant Missions - Local Encounters in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Century. Unto the Ends of the World, co-edited with Inger Marie Okkenhaug and Karina Hestad Skeie (Brill 2011); Museumsforteljingar. Vi og dei andre i kulturhistoriske museum (Museum Stories. We and the others in cultural history museums) (Samlaget 2016), co-authored with Sigrid Lien. She is currently collaborating with Sigrid Lien on a major project on the role of photographs from the Sámi area in past and present negotiations of history and identity; Negotiating History: Photography in Sámi Culture, financed by the Norwegian Research Council.

Notes

1. This work forms part of the joint research project Negotiating History: Photography in Sámi Culture, supported by the Norwegian Research Council, Programme for Sámi Research. The Sámi Parliament has granted me permission for conducting research on the photographs originating from the Schreiner Collection. Thank you to the staffs at Árran Julevsáme guovdásj, in particular Lars Magne Andreassen and Ragnhild Lien Ráhka for generously receiving us during our visit in June 2017. I am also greatful to Sveinulf Hegstad at Tromsø Museum and Per Holck at Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Division of Anatomy, University of Oslo for facilitating my research visits. I am also grateful to Sigrid Lien and the anonymous reviewers for useful commentaries on this article.

2. The Sami peoples in Norway, Sweden, Finland and Russia include several subgroups. One of these are the Lule Sámi (julevsáme), who have their own cultural distinctions and language.

3. From 1850 onwards, the Norwegian government introduced a massive assimilation policy, intended to civilize and transform the Sámi population into modern citizens of the newly established nation state Norway (Kjeldstadli Citation2010, 25).

4. Interview with director Lars Magne Andreassen and senior advisor Ragnhild Lien Ráhka at Árran in June 2017.

5. For ethical reasons,I have chosen not to reproduce the images from this work.

6. I first became acquainted with the images from the Schreiner Collection during a visit to the photography archive at Tromsø Museum in September 2014. The photographs caught my attention as they carried the stamp “Anatomisk institutt” (the Department of Anatomy). The photographs, apparently, were copies of an original collection deposited elsewhere. In March 2017, I visited the Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Division of Anatomy, University of Oslo in search of the originals, but established disappointedly that they were not there, and that the department only had a few of the Sámi photographs left in storage. During a visit to Árran in June 2017, it became clear that also they only had copies of the material. However, during a revisit to Tromsø museum the week after, the photo archivist Sveinulf Hegstad discovered a larger collection of glass plates with the Schreiner Collection material in the museum storage. As this article is written, it is not yet clear whether the glass plate collection is partial or complete.

7. While I have seen the collection of paper positives, I have not yet seen the recently discovered glass plates.

8. Interview with director Lars Magne Andreassen and senior advisor Ragnhild Lien Ráhka at Árran in June 2017.

9. Interview with director Lars Magne Andreassen and senior advisor Ragnhild Lien Ráhka at Árran in June 2017.

10. Personal communication with the administration at the Sámi National Assembly in Norway, august 2015.

11. Personal communication with the administration at the Sámi National Assembly in Norway, august 2015.

12. Personal communication with the administration at the Sámi National Assembly in Norway, august 2015.

References

- Edwards, E. 2001. Raw Histories Photographs, Anthropology and Museums. London: Bloomsbury.

- Edwards, E. 2012. “Objects of Affect: Photography Beyond the Image.” In Annual Review of Anthropology 41: 1–12. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-092611-145708.

- Edwards, E. 2015. “Anthropology and Photography: A long history of knowledge and affect.” in Photographies 8: 3.

- Evjen, B. 2000. “Kort- og langskaller. Fysisk-antropologisk forskning på samer, kvener og nordmenn.” Heimen, 37, 4, 273–292.

- Kjeldstadli, K. 2010. ““Fra innvandrere til minoriteter.” In Nasjonale minoriteter i det flerkulturelle Norge, edited by A. C. Bonnevie Lund and B. Bolme Moen. Trondheim: Tapir Akademisk forlag.

- Kjellman, U. 2014. “How to Picture Race?” Scandinavian Journal of History 39: 5. doi:10.1080/03468755.2014.948054.

- Kyllingstad, J. R. 2014a. Measuring the Master Race. Physical Anthropology in Norway, 1890-1945. Cambridge, UK: Open Books Publishers.

- Kyllingstad, J. R. 2014b. “The Concept of a Lappish Race: Norwegian Research on Sami Skeletal Remains in the Interwar Years.” In Old Bones. Osteoarchaeology in Norway: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, ed. B. J. Sellevold, 287–304. Oslo: Novus.

- Larsen, P., and S. Lien. 2007. Norsk Fotohistorie frå daguerreotypi til digitalisering. Oslo: Samlaget.

- Lien, S., and H. Nielssen. 2012. “Absence and Presence: The Work of Photographs in the Sámi Museum, RiddoDuottarMuseat-Sámiid Vuorká-Dávvirat (RDM-SVD) in Karasjok, Norway.” Photography & Culture 5 (3): 2012. doi:10.2752/175145212X13415789392965.

- Lundborg, H. F., J. Linders, and S. Wahlund, ed.. 1926. The Racial Character of the Swedish Nation. anthropologia suecica mcmxxvi. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Maxwell, A. 2010. Picture Imperfect. Photography and Eugenics 1870-1940. Brighton: Sussex Academic Press.

- Morris-Reich, A. 2016. Race and Photography. Racial Photography as Scientific Evidence, 1876-1980. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Morris-Reich, A., and D. Rupnow. 2017. “Introduction.” In Ideas of ‘Race’ in the History of the Humanities, edited by A. Morris-Reich and D. Rupnow. London: Palgrave.

- Möschel, M. 2011. “Race in Mainland Legal Analysis: Towards a European Critical Race Theory.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 34: 10. doi:10.1080/01419870.2011.566623.

- Poole, D. 2005. “An Excess of Description: Ethnography, Race, and Visual Technologies.” In Annual Review of Anthropology 34. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.33.070203.144034.

- Roberts, J. 2014. Photography and Its Violations. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Schreiner, A. 1951. Anthropological Studies in Sogn. Oslo: Det Norske Vitenskaps-akademi.

- Schreiner, A. 1929. Anthropologische Lokaluntersuchungen in Norge: Valle, Hålandsdal und Eidfjord. Oslo: Det Norske Vitenskaps-akademi.

- Schreiner, K. E. 1935. Zur Osteologie der Lappen. Vol. I & II. Oslo: Aschehoug.

- Schreiner, K.E. 1941. Bidrag til Rogalands Antropologi. Oslo: Det Norske Vitenskaps-akademi.

- Schreiner, K.E. Anthropologische Lokaluntersuchungen in Norge: Hellemo (Tysfjordlappen). 1932. Oslo: Det Norske Vitenskaps-akademi.

- Schreiner, K.E. 1946. Crania Norvegica. Oslo: Aschehoug.

- Sellevold, B. J. 2014 (ed.): Old Bones. Osteoarchaeology in Norway: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow. Oslo: Novus, p 17–36.https://www.nrk.no/troms/Sámiske-skjelett-returneres-1.7573034