ABSTRACT

This article discusses photographs of Sámi people produced in 1883 and 1884 by the Danish-Norwegian scholar and photographer Sophus Tromholt (1851–1896) and G. Roche, the expedition photographer of the French prince, Roland Bonaparte (1858–1924). While Tromholt’s photographs have been understood as an example of how Sámi people were portrayed as individuals, and how they adapted the medium of photography for their own purposes, Roche/Bonaparte’s anthropometric photographs are seen as the opposite, an attempt to document the typical, racial features of the Sámi population. Contrary to such an understanding, the article argues that there are more common features between these portraits and their contexts of production than earlier suggested. Inspired by Ali Behdad’s discussions on the nature of orientalist photography, it neither sees Roche’s/Bonaparte’s nor Tromholt’s photographic representations as entailing a binary visual structure between the Europeans as active agents, nor Sámi people as passive objects of representation. Furthermore, it suggests that there are common features to be observed in relation to their respective contexts of production, stressing how both Tromholt’s and Roche’s/Bonaparte’s photographs of Sámi people and northern landscapes must be understood not only in the context of the photographic identity performances of the academic male subjects who represented them, but also in relation to the visual economy in which these representations were embedded. This involves a consideration of how travel narratives from pre-photographic Arctic expeditions played a mediating role for the later photographic practices in the Sámi areas.

Setting off towards the north

In 1883 and 1884 two men, the Danish-Norwegian scholar and photographer Sophus Tromholt (1851–1896) and the French prince, Roland Bonaparte (1858–1924), undertook expeditions to the Sámi areas in the North of Norway. Tromholt’s visit in 1883 was spurred by an ambition to photograph the Northern lights. But while he was there, he also turned his camera towards the northern landscape and its inhabitants. A year later, Bonaparte, who was a fervent admirer of the French pioneer of the anthropometric measurement system, Paul Broca (1824–1880), travelled to Northern Norway as part of his grand scheme of building a large collection of anthropometric photographs. The two explorers left behind important collections of photographic material, not only portraits of the Sámi population, but also expedition shots: (group) selfies; fjord and mountain landscapes; Sámi dwellings; boats; towns, trains, historic and modern buildings etc.

Tromholt’s photographic archive of about 200 unique motives (among them 50 portraits) are now kept in the picture collection of the University library in Bergen, Norway. It consists of his glass-plate negatives, a photographic portfolio with positive photographs on paper, and printed versions of his illustrated publications (Fjellestad and Greve Citation2017).Footnote1 Bonaparte’s photographs, produced by his photographer G. Roche,Footnote2 are to be found at the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris. This collection similarly consists of glass-plate negatives, but also paper positives mounted on archive cards, and a small number of glass plate positives. Most of the images (120) are anthropometric portraits of individuals of Sámi heritage. The majority of these portrait subjects (103) are named, but17 of the sitters still remain unnamed in the archive. There are also positives mounted in albums, kept in the Bonaparte collection at Société de géographie, BNF.Footnote3

In addition to photographic documentation, Tromholt and Bonaparte produced written accounts of their journeys. In 1885, two years after his stay in the North, Tromholt published a book Under the Rays of The Aurora Borealis: In the Land of the Lapps and Kvæns (Under Nordlysets Straaler: Skildringer fra Lappernes Land) in English and Danish editions, richly illustrated with his own photographs (Tromholt Tromholt Citation1885a, Citation1885b). Bonaparte wrote three short articles about his Northern adventures. Two of these appear to be transcripts of public lectures and conference presentations which included the display of a large number of expedition photographs (Bonaparte Citation1885, Citation1886, Citation1889). One of his fellow travelers, François Escard, did however publish a series of diary notes from the expedition that offer a more detailed description of the journey and the process of accumulating images (Escard Citation1886).

It is nevertheless primarily their photographic work, and particularly their portraits of Sámi people, that have saved the two explorers from oblivion. Let us therefore start by introducing their portraits through a comparison between two chosen examples, respectively from Tromholt’s and Roche/Bonaparte’s production. Both images are evenly lit, three quarter length portraits of young Sámi men, positioned in front of neutral backdrops. In Tromholt’s portrait from 1883, we are facing Josef Henrikson Buljo from the Sámi village, Kautokeino, near the Finnish border in Norway. He is posing in pesk (Sámi winter coat made of fur) with a pipe in his mouth and melting snow in his hair (). Buljo is photographed frontally, but his gaze is slightly turned away from the photographer, with his eyes slightly narrowed in the sharp daylight. In his mind, he seems already to have drifted off to somewhere else. It is as if we are observing him in the process of attending to the movements of his herd in a snowy landscape.

Figure 1. Sophus Tromholt, Josef Henriksen Puljo, Kautokæino, 1883. Photograph reproduced with permission from the Picture Collection, University of Bergen Library.

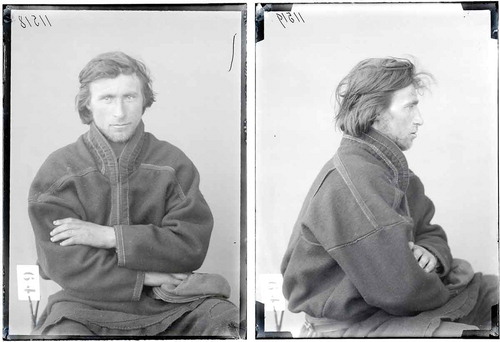

The young man whose appearance has been documented in the Roche/Bonaparte portrait from 1884, was Jol Andersen (). According to the notes taken by the expedition members, he was a member of the coastal Sámi population in Finnmark. He is wearing a typical Sámi kofte (woolen coat), and is sitting with his hands folded over his chest, and his hat in his lap. Unlike Tromholt, the French expedition photographer not only posed his sitter once, but twice—in accordance with the en face and profile formula of anthropometric portraiture. Furthermore, a number plate held by a metal clamp is visible in the left corner of the images. The plate served to associate the sitter with the data collected about him. The standardized setting is in itself a reminder of how this kind of portraiture was intended to display the sitter as a typical example of one of nature’s species. Jol Andersen nevertheless comes across as something else than a typological specimen. It is a portrait that clearly exposes the sitter’s personal integrity. Andersen’s gaze is mild, but also direct and almost confrontational. While the crossed arms could be seen as protective, they can also be understood as indicating distance and resistance. His back is straight, and he makes no attempt of hiding hands that bear witness of life dominated by manual labour in a harsh climate. So how then, are we to understand the complex nature of such a portrait?

Figure 2. Roland Bonaparte/G.Roche, Jol Andersen, anthropometric photographs, 1884. Photograph reproduced with permission from Musée du Quai Branly, Paris.

Not much has been written about the photographs Tromholt and Roche/Bonaparte produced during their stays in the North. The rather limited existing literature seems to be divided in two directions. On one hand, the attention has been directed towards contemporary artistic reengagement with the Bonaparte images, as “a dialogue between past and present concerns” (Edwards Citation2001, 213) and as part of visual repatriation processes (Dobbin Citation2013). On the other, Roche’s/Bonaparte’s and Tromholt’s work has been compared with the purpose of demonstrating how those who posed in front of Tromholt’s camera, contrary to Roche/Bonaparte’s sitters, were portrayed as individuals, not as types. Furthermore, Roche/Bonaparte are claimed to have been in an asymmetrical power relationship with their subjects, while the contact between Tromholt and his sitters is understood as reciprocal and equal in character. The comparative efforts also tend to be “nicely tied up” to a suggestion of how the differences between the photographs must be understood in relation to differences between their respective contexts of production. Unlike Bonaparte’s Sámi portraits, Tromholt’s are claimed to be commissioned by the Sámi people themselves. Consequently, they are not representing the sitters as examples or types, but as individuals adapting the medium of photography for their own purpose (Larsen and Lien Citation2007, 165–174, Fjellestad and Greve, 190–203).

A version of this line of argument recently also secured Tromholt’s Sámi portraits a place on the list of UNESCO’s world heritage documents. In the nomination of the Tromholt archive, it was even proposed that without this archive, there would only exist images of Sámi people produced in a colonial context.Footnote4 Tromholt is thus seen as a kind of anti-colonial hero, devoid of any attachment to the international colonial culture of his time, while Roche/Bonaparte is conceived as representative of the opposite: the typological othering of the Sámi performed through the medium of photography. His Northern sojourn has tellingly been characterized as “a small act in a grand production of imperial hubris” (Lee, Weaver, and Prebensen Citation2017, 16).

The binary oppositional structure of this argument may nevertheless overshadow the common features that also seem to exist in the two explorers’ Sámi portraits. This is exactly why I have chosen the two portraits presented initially. Both collections comprise images of Sámi individuals of both genders and all ages, as well as examples of varying degrees of asymmetry and reciprocity in the relation between the sitters and the photographer. However, while earlier readings have singled out images that seem to emphasize the assumed contrast between Tromholt and Roche/Bonaparte’s photographic agendas, my selection emphasizes similarities. The selected images both represent handsome young men with a strong presence,as the interplay with native masculinity is important to the formation of the particular kind of academic masculinity that will be discussed in this article. Furthermore, when looking at Bonaparte’s anthropometric images, it is not the measurements of the individual sitters’ craniums that take our fascination. No different than those of Tromholt, Roche’s/Bonaparte’s photograph stir a desire to know more about the photographed subjects: who they were; how they lived their lives—and their thoughts and dreams. Even though the photographs could be claimed to be inscribed into different agendas and thereby belong to different genres, their similarities demonstrate how ethnographic and anthropometric photography are overlapping in terms of genre. Inspired by Ali Behdad’s discussions on the nature of orientalist photography, I neither see Roche’s/Bonaparte’s nor Tromholt’s photographic representations as entailing a binary visual structure between the Europeans as active agents, and Sámi people as passive objects of representation (Behdad Citation2013, 13). Yet, their images are each in their own way embedded in asymmetric power relations.

The photographic albums and written accounts that Tromholt and Bonaparte produced from their journeys, reflect not only how they positioned themselves in relation to their Sámi subjects, but also how they addressed a wider international audience as adventure seeking scientists and explorers. In this article, I will therefore approach their images in relation to the visual economy of the 19th century culture of travel and exploration. This will include a consideration of the mediating role of the visual travel narratives from the era of pre-photographic Arctic expeditions. Furthermore, Tromholt and Bonaparte did not exclusively photograph the indigenous population during their stays in the North. In addition, they both produced elaborately staged self-portraits. I will thus also propose that their photographs of Sámi people and northern landscapes must also be understood in the context of the photographic identity performances of the male subjects who represented them, and their respective efforts to perform academic solemnity.

Academic masculinities

In his self-portraits, Sophus Tromholt firmly establishes his own bodily presence in the Arctic communities and landscapes. He poses with confidence at work, as an astronomer, in front of his outdoors Aurora Borealis-observatory (), and as an ethnographic photographer, bent down behind the camera (). Bonaparte, who prior to his own journey, had purchased a copy of Tromholt’s expedition portfolio,Footnote5 likewise made considerable efforts to immortalize his own scholarly presence in the North. Not only does Escard’s written account of the Bonaparte expedition, emphasize the prince’s “affectionate”, almost heroically active participation in the process of gathering data, he describes how Bonaparte himself took charge of preparing the sessions, and how he “most of the time”, single-handedly conducted the measuring of the Sámi subjects (Escard Citation1886, IX, 59). The prince was of course also photographed while actively engaged in such a session (). This photograph, taken outdoors in front of a small, weather-beaten timber house, displays Bonaparte humbly posing on his knees in the service of science, while taking the measures of a young woman’s head. Centrally positioned in the pictorial space, he is flanked by a group of roughly bearded fellow travelers, who are busily acting as his note-taking assistants. In fashionable bowler hats and shiny shoes, they form a stark contrast to the members of the local Sami community, lined up passive observers in the background.

Figure 3. Self-portrait at the Aurora Borealis Station in Kautokeino, 1883. Photograph reproduced with permission from the Picture Collection, University of Bergen Library.

Figure 4. Sophus Tromholt, Self-portrait with camera, 1883. Photograph reproduced with permission from the Picture Collection, University of Bergen Library.

Figure 5. Roland Bonaparte/G.Roche, The prince engaged in an anthropometric session, 1884. Photograph reproduced with permission from Musée du Quai Branly, Paris.

This photographic accentuation of professional activities in relation to the building of male scholarly identity was a very modern phenomenon at the end of the nineteenth century, and by no means exclusive to Tromholt. In a study of the self-presentations of the Finnish archaeologist, Juhani Rinne, Visa Immonen demonstrates how the photographs of this prominent academic, in resonance with discourses of civilized men, particularly drew attention to Rinne’s body at work (Immonen Citation2012, 37–52). Thus, the way both Tromholt and Bonaparte staged themselves in the process of performing scholarly work, was very much in line with the key-transformations of masculinity at a time where “‘men’ and ‘work’ were used as virtual synonyms” (Danahay Citation2016, 1, White Citation2014). Masculinity became associated with industriousness and enterprise.

Such qualities were even further emphasized and developed within the culture of exploration with the traveller-as-a-hero as centrally staged idealized figure. According to Wendy Mercer, this figure “serves to validate (or indeed glorify) the activity of the explorer in terms of physical strength and/or courage” (Mercer Citation2006, 6–7). She stresses how the traveller-as-a-hero in mid-nineteenth century travel writing on one hand is described in a vocabulary associated with traditional masculine heterosexual activity. Nature and wilderness is for example something to be penetrated and conquered. Tromholt and Bonaparte’s additional roles as leaders of scientific expeditions under difficult circumstances, typically invoked classically military requirements: such as braveness, determination, stamina etc., but also the ability to stay calmly detached and undisturbed observant. On the other, the masculinity of the travelling hero connects to a scientific discourse where natural phenomena can be mapped, “measured, classified, surveyed and explained in terms of cause and effect” (Mercer Citation2006, 10). Like many other nineteenth century explorer travellers, Tromholt and Bonaparte thus are performing academic masculinity in their self-representations. These identity performances must however be understood in relation to the broader context of their respective endeavours, the nineteenth century international culture of travel and exploration.

Journeys in time

Tromholt and Bonaparte’s journeys was part of this this grand era of scientific expeditions, seeking knowledge about natural phenomena and exotic others. Their ventures were adapted to an evolutionary model where culture and “race” corresponded step by step. Primitive customs were perceived as a lack of mental maturity among the wild peoples. Thus, their mental immaturity formed a radical contrast to their own academic masculinity. This immaturity was understood as biologically anchored and hereditary—and therefore as something that could be scientifically established through the methods of physical anthropology. The theory of evolution was in other words based on an understanding of correspondence between time and space. Journeys to far and distant places unfolded in this way as a practice where science intersected with adventure. Such journeys thus also became journeys back in time (Johansen Citation2007, 364–366).

Sentiments of travelling back in time are expressed in both Sophus Tromholt’s and Roland Bonaparte’s descriptions of the people they encountered in the north. In 1885 Tromholt presented some of his photographs from Finnmark in his book Under the Rays of the Aurora Borealis: in the Land of the Lapps and Kvæns. Quoting the Swedish doctor and anthropologist, Gustaf von Düben (1822–1892), he characterized the people that trustingly had placed themselves in front of his camera as “savages” and “true children of nature” (Tromholt Citation1885a, 158). In an article published the same year, Bonaparte, who also referred to Düben, accordingly described the Sámis as an ancient people, living a pastoral life close to the border of European civilization (Bonaparte Citation1885, 119).

Even though they thus adapted a similar view on the Sámi people, their actual encounters with the Sámis differed from each other in duration and character. Tromholt, who primarily wanted to do research on the Northern light, stayed for a whole year in the village of Kautokeino in Finnmark, where he gradually became interested in the local Sámi population (Larsen and Lien Citation2007, 165–174, Fjellestad and Greve, 190–203). Roland Bonaparte (a grandnephew of Napoleon B.) travelled northwards only for a few summer months with the primary intention of studying the Sámis. Unlike Tromholt, he lacked academic training.

After having embarked on a military career as a young man, Bonaparte became wealthy through his marriage to a rich heiress, who died in childbirth in 1882. Two years after the death of his wife, he enrolled as a member of the Société d’Anthropologie. As a fervent admirer of Paul Broca (1824–1880), a pioneer of the anthropometric measurement system, Bonaparte started building a large collection of anthropological photographs (CitationBeaugé, 134–135). He did in general not travel far to produce, or buy, such images. Being basically an armchair anthropologist, he simply visited the many and immensely popular displays of exotic peoples that took place in many European cities at the time; in Amsterdam (1883); Paris (1883,1889); Berlin and London (1884). In the archives of Musée Quai Branly and in the collections of Société de géographie, at the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, there is much evidence of his photographic engagement with these displays. Indeed, as most of his anthropometric photographs were taken in such venues, Bonaparte’s expedition to Norway in 1884 was quite exceptional. It was also his first, which was followed by his other expeditions to North America (1887–1893), Eastern Europe and to Corsica (1887). (Jehel Citation1994–1995, 68–70). However, the governing idea behind both his and Tromholt’s journey, was one that was common among most 19th century travellers of adventure and exploration: that genuinely distant places and unknown tribes were still to be found—as white spots on the map (Johansen Citation2007, 365).

A visual economy of scientific explorations

Moreover, the landscapes that met Bonaparte and Tromholt’s eyes in the north were no longer to be perceived as such white spots. Neither was Bonaparte the first French aristocrat to set foot on these parts of the world, nor to produce images of Sámi landscapes and Sámi people. Inspired by Stephen Bann, I will argue that he, when travelling north with his photographer, G. Roche, also moved into an already existing, dense visual economy (Bann Citation2002 16–25). What then, characterized what might be conceptualized as “the visual economy of scientific explorations”, and in particular the relationship between photography and other visual media?

It seems pertinent here to draw also on Ali Behdad’s argument about how early Orientalist photographic projects were in dialogue, not only with travel writing, but also with and other kinds of visual representations, primarily painting. According to Behdad, “early- and mid-nineteenth-century European travelogues and Orientalist genre paintings defined what was worthy of photographing in the orient, the Oriental photograph in turn powerfully mediated the vision of every traveler who went to the Orient” (Behdad Citation2013, 18).

Such a dialogue is also noticeable in the visual and written material from the Arctic areas, paintings, travelogues and photographs. Some of the first genre paintings from the Sámi areas were produced in 1839–1840, just after the introduction of photography by François-Auguste Biard (1798–1882), an artist known to have experimented with the new medium (Barbara.Citation1985, 86). The French government was at the time in the midst of launching a series of polar expeditions. Encouraged by king Louis-Philippe of Orleans (1773–1850), Biard joined a scientific expedition to the Northern areas of Norway and Sweden. The expedition that took place between 1838 and 1840, was led by Paul Gaimard. Let us shortly consider some of Biard’s paintings from Sápmi in order to see what was considered worth representing, and how the chosen subjects were represented.

Importantly, these works, a series of history paintings, were commissioned by the king to commemorate his own former journey to the North of Norway and Sweden, which took place in 1795, in the aftermath of the French revolution (Chaudonneret Citation1999; J.I Citation1996). Travelling incognito as Mr. Müller (in the company of Marquis de Montjoie, who called himself Froberg, and his valet Baudoin) he got as far as to the North Cape (With and Wessel Citation1930 1940, 22). Why he singled out these Northern, mainly Sámi areas, as his destination, remains a mystery. The prince himself never wrote about his journey. In Norway, however, a collection of the stories about and memories of his stay was published in 1930. Well aware of the political circumstances around Louis Philippe’s sojourn,Footnote6 the two authors describe it as a strange whim of fashionable Romanticism, connected to the general urge among travellers to produce written as well as visual travel memories (With and Wessel Citation1930, 10).

The paintings that Louis-Philippe commissioned from Biard several decades later in his new role as king of France, were originally displayed at the Palais Luxembourg. Today, however, they lead a quiet existence in one of the wings that is not generally open to the public at the Château de Versailles. One of them (), “Le Duc d’Orleans recu dans un campement de Lapons, août 1795”, is particularly interesting—and not just as a masterpiece in political propaganda.

Figure 6. François-Auguste Biard, Le Duc d’Orleans recu dans un campement de Lapons, août 1795,1841. Oil on canvas, 132 × 163 cm. Reproduced with permission from Château de Versailles.

As indicated by its title, the painting seeks to represent how the native population of the distant North welcomed the prince, a political refugee from the violent events of his home country, with warm hospitality. It is painted in the style that at the time was favored at the Paris Salon, an almost photographic commitment to naturalism in combination with vivid romantic imagination. In a glowing atmosphere of peace, tranquility and understanding, a Sámi family is sheltering the heroic, thoughtful prince in their tent. Gathered around the open fire-place they are humbly offering him protection, support and bowl of food. The painting also opens up for a glimpse of the world outside the tent, with reindeers, herders, and wide, frosty landscapes.

As a post-revolutionary and post-Napoleonic king of France, Louis- Philippe had to be immensely cautious about his public image. The painting accordingly presents him as able to adapt to any kind of circumstance, modest, yet visionary. He is in short, represented as a man of the world (an important message to get through, perhaps also because his rivaling cousins in the Bourbon family never travelled). Even though the king had commissioned Biard to represent “une rencontre fraternelle avec la population” (J.I Citation1996, 331–332), it importantly also establishes a contrast between the aristocratic visitor and the indigenous population in the North. While Louis-Philippe is a man envisioning the future, the Sámi people are living in the state of a distant past. They are portrayed as generous and kind, but nevertheless marked by their primitive lifestyle—in other words framed in the kind of pastoral idyll that Roland Bonaparte lamented as being on the brink of disappearance 40 years later.

The retrospective painting of the king was probably based on sketches made by Biard while travelling in the north of Norway. An account of the artist’s journey, published after his return to Paris, describes his encounter with Sámi people in the city of Hammerfest. It reports how Biard was drawing the Lapons fervently for weeks in the midnight sun, while waiting for the boat for Svalbard. But it also articulates some amused reflections on their simplistic and superstitious way of engaging with his drawings. In the same vein, it characterizes the Sámis in a manner closely corresponding with the later writings of Tromholt and Bonaparte, as good people, but also as something out of another world—as equally strange and simple minded (Boivin Citation1842, 29).

Such ideas are linked to the concept of race-typological difference developed through the science of natural history by the end of the 1800-century, with Compte de Buffon (1707–1788) as a major figure in the French context. According to Buffon all human beings belongs to one race, originally created to live in an area of North East Asia in an environment similar to Europe. However, after the human race was diffused into other parts of the world, it was only the Europeans that had managed to hold on to the original human qualities. In other parts of the world non-optimal environmental conditions, had created races that in various degrees differed from the European norm. The Sámi people in the North and the Ethiopians by the equator were seen as the most degenerate variations (Eddy Citation1994, 658–661, Kyllingstad Citation2012, 6–7).

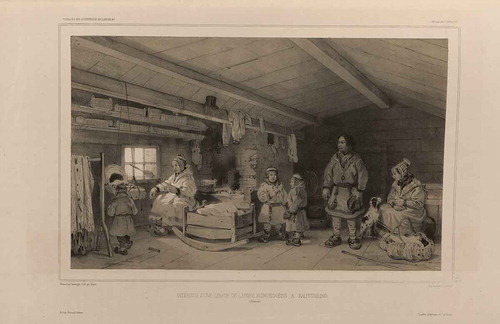

Even so, the visual representations produced by Biard and other artist travellers working in the service of the Gaimard expedition, seem to defy this particular version of race-typological thinking. An example of the kind of publication that was typically produced as a result of the expedition, is the double volume Atlas historique et pittoresque with lithographic prints produced after drawings by artists that took part in the enterprise (Mayer, Lauvergne, and Giraud Citation1852). There are a few references to race-typological ideology in these volumes, such as the image of what is labeled as a Sámi cranium. However, in the majority of the prints Sámi individuals portrayed are referred to by name, as in the portrait of a young man named Anders Persen. The Sámis are visualized in a manner that emphasize qualities such as beauty, strength and integrity. Their homes are inviting and harmonious, they are hard-working and productive, and their communities are presented as well organized ().

Figure 7. Barthélemy Lauvergne: Interieur d’une cabane de Lapons Norvégiens a Kautokeino (Finmark), from Voyages en Scandinavie en Laponie au Spitzberg et aux Feröe. Atlas Historiques et pittoresque, 1852. Lithographic print of drawing, reproduced with permission from the Norwegian National Library.

The Sámis are thus represented as a people more than capable of adapting to harsh circumstances, most likely reflecting the view of Xavier Marmier, the well-known French humanist that was in charge of the cultural-historical investigations of the expedition. The visual atlas may therefore also be seen as a modification of Buffon’s idea that the development of the human species could be reversed. For while Buffon had claimed that African people or Lapons could be elevated to the level of Europeans if they were moved to the more ideal European climates (Kyllingstad Citation2012), the prints produced by the artists headed by Marmier clearly demonstrates the ability of Sámi people to elevate their level of civilization within the context of their own environment. As noted by Wendy Mercer, Marmier’s travel writing testifies to how he not only sought “to diminish the distance between himself and the [Sámi] peoples encountered in order to share and gain some intimate understanding of their lives”. He also explained the differences between himself and the Sámi “in terms of their different physical and cultural context” (Mercer Citation2006, 14–15).

Biard’s painting of the Lutheran pastor Læstadius preaching to the Sámi people, which became immensely popular with the audience of the French Salon in 1841 (Thingstad Citation2013, 34) offers an even more dramatic and very literal interpretation of Marmier’s version of evolutionary theoryFootnote7 (). Here a group of Sami people have moved out of their simple dwellings, deeply seated in a sublime, frosty landscape of snow and ice. In an elevated open space in the foreground, they are facing the civilized Christian world in the shape of the Lutheran pastor with attentiveness, respect and curiosity. In the eyes of the pre-photographic artist-explorer, the indigenous people of the North were about to leave the distant past.

Leaving the past—encountering the present

The idea of transporting oneself to a distant past, as presupposed by the evolutionary model that formed the ideological basis of the scientific expeditions, gradually became more problematic with the progressing processes of globalization in the second half of the nineteenth century (Johansen Citation2007, 365). Bonaparte travelled to the North to photograph the Sámi, which he romantically envisioned as an isolated primitive people, still living as they had done for thousands of years. What he experienced when he arrived there by steamship, was something entirely different: “I would remark that there hardly are any pure Lapps”, he lamented in one of his articles. (Bonaparte Citation1886, 211). Not only was the Sami race, as he saw it, threatened by the Finnish invasion into the Northern areas of Norway and Sweden, but even more so by the rapidly approaching European culture and lifestyle represented by Norwegian settlements and modern steamships (Bonaparte Citation1885, 119).

Tromholt who likewise never had envisioned the Sámis as inflicted by the processes of modernization and globalization, wrote about his amazement when meeting a young girl in the Sámi village of Kautokeino, who greeted him in both German and French language:

One evening a Lapp damsel in green jacket went past me. “Guten abend mein Herr!” she said. Had my trusty friend Rolf [Tromholt’s dog] addressed me in German, I doubt I should have been more astonished than I was. But my surprise was greater still when she said, “Je parle Francais, Monseiur.” (Tromholt Citation1885b, vol.2, 127).

He explains this rather unusual familiarity with foreign languages by relating how the girl had visited Berlin and Paris as member of one of the Sámi families that were publicly exhibited in these cities in the1870s and 1880s. The modern culture of science and exploration with which both Tromholt and Bonaparte identified, had in other words made its impact on the North long before their own arrival. The two of them had to acknowledge, not only the absence of white spots and “pure lapps”, but for Tromholt, also the failure in photographing the Northern lights. As remarked in a review of his work in Science in 1885, “he utterly failed in getting any impression on a negative” (Unknown author Citation1885, 528). They thus had to face the present, while striving to maintain maintain or find new ways of confirming their scientific seriousness. Perhaps as a way of addressing, or working against such uncertainties, Bonaparte and Tromholt carefully staged themselves as men of science, “naturally” situated in the heart of the Northern landscape. These identity performances took place in several forms: through scholarly texts, written accounts of their journeys, and not least, through the production of expedition photographs (albums and diapositives).

Tromholt’s most important arena of self-presentation was undoubtedly his book, Under the Rays of The Aurora Borealis: In the Land of the Lapps and Kvæns, a curious, and typical of its time, mixture of a diary (where he, in a laid-back, good-humored tone, writes about himself in third person); a day to day account of his travels and experiences in Finnmark; an ethnographic study of the Sámi; and a scientific report (). Notably however, the majority of the chapters revolve around Tromholt’s encounters with Sámi peoples. It is anecdotal and personal in style, but in the typical way of the amateur ethnographer, it is at the same time striving towards scholarly characterizations of Sámi physiognomy, customs and lifestyle. It is in other words a text that performs academic masculinity by fusing a subjectivity (and thereby authority) typical of the Romantic discourse with the objectivity of science.

Figure 9. Cover of Danish edition of Sophus Tromholt’s Under the rays of the Aurora Borealis: in the land of the Lapps and Kvæns.1885.

He does, for example, not refrain from boasting about how he, in his eagerness to contribute to the noble cause of ethnography has secretly excavated a Sámi skeleton and four craniums in the middle of the night at the cemetery in Kautokeino: “What will not a savant submit to for Science” (Tromholt Citation1885a, 185). His research activity on the Northern Lights is on the other hand reduced to an appendix section in the end of the first volume.

In this way, the book indicates a shift in Tromholt’s self-presentation from polar researcher/astronomer, to ethnographer/photographer. The importance he attached to his own achievement as a photographer and the uniqueness of the images is clearly stated in the introductory chapter. He proudly states that “they form the sole complete collection of its kind in existence of life, people, and nature in the Land of the Lapps and Kvæns” (Tromholt Citation1885a, v).

The accumulation of photographs of Northern subjects similarly seem to have worked as a way of securing the scholarly profile of Roland Bonaparte’s expedition. It cannot be denied that Bonaparte’s grand scale anthropometric enterprise and his detailed description of the average Sami individual, of their height, facial form and features, eyesight, skin-color, voice, muscular strength, ability to walk in ice and snow, etc. (Bonaparte Citation1885, 119–120), appear as something of a paradox in view of his realization of how pure Sámi people no longer existed. However, the alleged rationality behind this accumulative activity was a presumption of the possibility of reaching the past through the present. By observing “modern” Sámi individuals as remnants or traces of a race on its brink of extinction, one could, as Bonaparte’s fellow traveler and historiographer, François Escard, phrased it, establish an understanding of their history (Escard Citation1886, IX).

Moreover, photography held a privileged position in the domain of science at the time, not simply due the belief in its objectivity and impartiality. The assertion of a seamless relation between the photographic image and appearances, also prompted a belief that the image could function as reality itself (Green Citation1984, 4). Additionally, imagination was deeply ingrained in practices of racial photography (Morris-Reich Citation2016, 21). Roland Bonaparte may as with many other racial authors, have employed photography to serve an imaginary clarification between the imaginary past and the empirically tangible present, or what he considered to be both visible and invisible features of race. Photography could in this sense be understood as a way to salvage the scientific credibility of his project and its originator—and to maintain the image of the expedition’s scholarly solidity, seriousness and stamina.

Biographical narratives and power relations

When comparing Bonaparte’s and Tromholt’s respective photographic oeuvre, it becomes visible how their numerous portraits of Sámi people were inscribed in narrative structures related to the performances of the academic masculinity of their creators. In addition to representing the indigenous population, their respective ”Arctic discourses” comprised photographs aimed at documenting the expedition itself. The iconography of these visual constructs, on one hand places itself in continuation of the pre-photographic visualisations landscapes and indigenous peoples as exemplified in the material from the Gaimard expedition.

Tromholt’s photographic portfolio, Billeder fra Lapperns Land/Tableaux du Pays des Lapons (Tromholt Citation1883), presents his many images of Sámi individuals, families and groups in the village of Kautokeino. But it also comprises photographs of local landscapes, rivers, mountains, traditional farm houses, as well as the (modern) homes of the local civil servants and tradesmen, churches and schools. He documents the streets of Northern towns, such as Vardø and Vadsø, and traditional industries, such as whaling and reindeer herding (–). Moreover, in resemblance to the Gaimard expedition members, and as noted above, both Tromholt and Bonaparte firmly establishes their own bodily presences in the Arctic communities and landscapes.

Figure 10. Sophus Tromholt, Coastal Sámis from Lærredsfjord.1883. Photograph reproduced with permission from the Picture Collection, University of Bergen Library.

Figure 11. Sophus Tromholt, Farm in Kautokeino. 1883. Photograph reproduced with permission from the Picture Collection, University of Bergen Library.

Figure 12. Sophus Tromholt, Kaafjord, 1883. Photograph reproduced with permission from the Picture Collection, University of Bergen Library.

Figure 13. Sophus Tromholt, Street in Vadsø, 1883. Photograph reproduced with permission from the Picture Collection, University of Bergen Library.

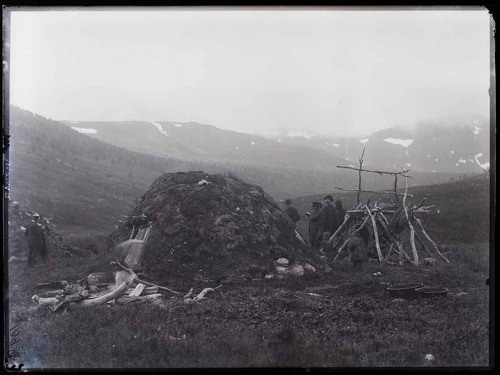

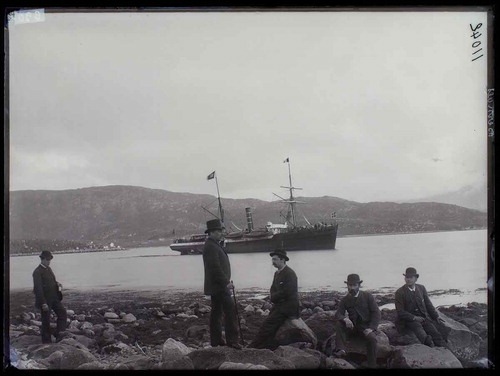

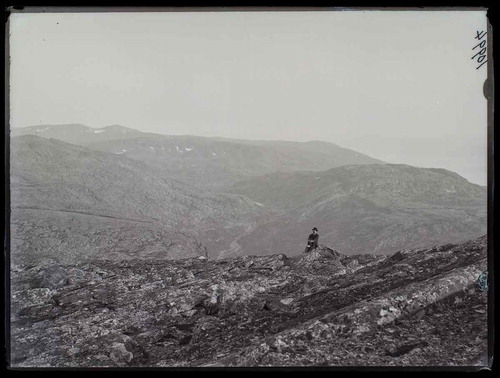

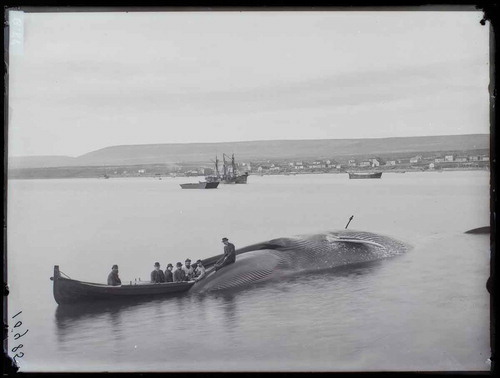

The evidence of Bonaparte’s Northern sojourn form part of a newly digitized collection of glass plate negatives at Musée du Quai Branly, consisting of 140 expedition images. This series provides a telling example of the structuring of the biographical body of the French prince as an academic and adventurer. It is the prince’s body, moving around in the Northern scenery, that works as the constitutive element of this photographic travel narrative. Surrounded by his crew, Roland Bonaparte is encountering members of the local indigenous population (), inspecting the shores (), contemplating dramatic seascapes () and the sublimity of the Arctic mountain areas (), as well as the specificities of the Northern lifestyle. He engages, for example, in the process of whale hunting, while also making time for a “selfie”, posing well-dressed on the whale’s back (). The photographs are demonstrating his ability to meet the challenges of an exploring traveller, but also to politely enjoy the hospitality of the local population. They thus strongly evoke Biard’s earlier, pre-photographic, romanticist representations of Louis Philippe’s fearless canoe rides and stoically humble visits in Sámi dwellings as “a man of the people”.

Figure 14. Roland Bonaparte/G.Roche, Bonaparte and his expedition members visiting Sámi dwellings, 1884. Photograph reproduced with permission from Musée du Quai Branly, Paris.

Figure 15. Roland Bonaparte/G.Roche, Bonaparte and his expedition members inspecting the shores in the North of Norway, 1884. Photograph reproduced with permission from Musée du Quai Branly, Paris.

Figure 16. Roland Bonaparte/G.Roche, Roland Bonaparte in coastal landscape in the north of Norway. 1884. Photograph reproduced with permission from Musée du Quai Branly, Paris.

Figure 17. Roland Bonaparte/G.Roche, Roland Bonaparte in mountain landscape in the north of Norway. 1884. Photograph reproduced with permission from Musée du Quai Branly, Paris.

Figure 18. Roland Bonaparte/G.Roche, Roland Bonaparte and his visiting a site of whale hunting. 1884. Photograph reproduced with permission from Musée du Quai Branly, Paris.

As part of their respective performances of courageous Arctic “adaption”, both Tromholt and Bonaparte pose for self-portraits, triumphantly dressed in fur as Sámis (,). Such images, are to use Homi Bhabhas’ expression, based on acts of mimicry. But while Bbabha is referring to mimicry in relation to how the colonized mimics the colonizer (Bhabha Citation1984, 126), Tromholt’s and Bonaparte’s self-portraits are on the contrary mimicking the colonized Sámi population. In this way they seem to appropriate the strength, ability to master nature and survive under harsh conditions and integrity of the local population. Importantly also, their performances of academic masculinity in the wilderness, both echoes and feeds on the Sámi masculinity displayed in their portraits of Jol Andersen and Josef Henrikson Buljo. Even so, the explorerers’ self-portraits obviously work as a way of transforming the other through the gaze of the two travellers, who both notably were participants in in the international culture of colonial exploration. Their self-portraits are therefore, and no less than the portraits of the Sámi people they placed in front of their cameras, firmly embedded in asymmetric structures of power.

Figure 19. Roland Bonaparte/G.Roche, Roland Bonaparte wearing Sámi winter outfit. 1884. Photograph reproduced with permission from Musée du Quai Branly, Paris.

Such structures frequently also reach the surface of the written accounts of their respective journeys. When voicing the observations of the Bonaparte expedition, Escard on one hand echoes Marmier’s ideas about indigenous people’s ability to elevate their level of civilization within the context of their own environment. Accounting for the lifestyle and culture of the coastal Sámi community at Mortensnes (where the expedition photographed Jol Andersen and his family), he stresses how their way of dressing is perfectly adapted to the climate, how their houses are constructed to keep warm in the winter and fresh in the summer etc. Tromholt likewise states how “the Lapps, like most natives, know best what suits their requirements” (Tromholt Citation1885a, 108). On the other hand, Escard makes it clear that Sámi dwellings lack “the elegance of the wooden houses of Norwegian and Finnish people” (Escard Citation1886, 58). Similarly, when describing the colourful Sámi costumes, he cannot help mentioning how they “unfortunately” differ from “our [French] taste” (Escard Citation1886, 46).

Tromholt, even more poignantly exposes underlying relations of power, when he exclaims how he misses “the homes in the South” where “comfort and refinement reigns”. Furthermore, he complains about how lonely it is to be among so few “civilized people” (meaning Norwegians), in the busy Sámi village of Kautokeino: “We are, with the exception of ladies and children, only three civilized beings, viz., the sheriff, the merchant—the man of oil- and the writer [Tromholt]”. He tellingly also writes about the necessity for visitors to Arctic areas to “strip off the European, and descend to the level of culture of the Asiatic; if not, he will never know them” (Tromholt, Citation1885b, 123).

As a contrast to his derogative characterizations of Sámi people, Tromholt immodestly (and in third person) establishes his own identity as someone who “has been the friend of Lapps and abused by people from Iceland. He had caviar in Russia and wine at the Rhine. He had spleen at Loch Lomond and stomachache in Amsterdam. He has solemnly contemplated Rafael’s Madonna as well having danced the Cancan at Ball Mabille” (Tromholt Citation1885b). Like other travelers before him, he strives to convincingly come across as nothing less than a man of the world. Both Tromholt and Bonaparte’s Sámi subjects are thus inscribed into what Anne Maxwell, in her characterization of colonial display, has termed as a language of stark opposition, with emphasis on evolutionary hierarchy (Maxwell Citation2010, 43).

Photographic encounters and negotiations

This language of contrasts importantly also permeates the way their actual photographic encounters with Sami people are described. Tromholt and Escard both relate episodes that are supposed to support an implicit understanding of their Northern subjects (not only Sámis, but also Kvens, i.e. Finnish settlers in Sámi areas) as ridiculously simple-minded, childishly naïve and prone to superstition. Escard writes at length about the Bonaparte expedition’s encounter with a Sámi man named Siva Elias Phara. Terrified of the camera box itself (and by discovering a reversed image of his own body with his feet in the air and his head in the lower part of the image), he vehemently resisted to be photographed (Escard Citation1886, 30). Tromholt’s paternalistic account of how people in Kautokeino daily gathered in fascination and awe around the “magical apparatus”, is also typical in this respect:

Among my instruments there was none which attracted their sympathy as much as my photographic apparatus. Daily some of them came begging to have their govva—portrait—taken. They never seemed to get tired of seeing themselves or their friends portrayed. My greatest pleasure was to take them up into my photographic chamber, and let them witness the production of the portrait. Then their surprise knew no bounds, and in awestruck wonder they gazed into the semi-darkness at the birth of their likenesses. In truth, we, who claim to know so much about the properties of light and the elements, have as much reason to watch this beautiful process in wonder as the simple Lapps; we understand it almost as imperfectly as they (Tromholt Citation1885a, 92).

Even though Tromholt admits to recognize their reactions to the beauty and magic of the medium in his own, he elsewhere takes on an even more condescending tone. The surprise and excitement about photography among people in the small community in Lærredsfjord could not, as he phrases it, have been greater “if the sea-serpent had suddenly made its appearance in the bay” (Tromholt Citation1885b, 216). His vain efforts to explain the locals “some rudiments of the theory of Daguerre and Talbot’s noble art” are in the same vein compared to “teach[ing] a cod-fish mathematics” (Tromholt Citation1885b, 217). Furthermore, he ridicules the way his sitters, after having been informed about the accuracy of the medium, painstakingly strive to look their best:

The stir and bustle became now as great as if they had been invited to a Court ball. The heads of all the little ones disappeared in buckets, after which operation the mother’s hands served as comb for the whole family. Then the old, dirty rags were exchanged for the newest coats, the jauntiest caps, the smartest aprons, and the gaudiest shawls. When an hour had been spent in these preparations, and another twenty minutes in placing the group—of course, everybody did his best, as on all such occasions, to place himself in the most ridiculous position and assume the strangest expression (Tromholt Citation1885b, 217).

The mediated and European-biased nature of the texts and images that were produced in relation to Tromholt and Bonaparte’s enterprises of exploration in the Sámi areas should thus be obvious. But as documented in other studies of similar material, such kinds of representations may nevertheless potentially harbour valuable insights about the “other side”—the indigenous perspective (Williams Citation2003, 140). In her study of early indigenous uses of photography in the Pacific Northwest, Carol Williams warns against dismissing the Euro-American produced photographs of Indians and Indian life as inherently biased or one-sided. She not only points to how Native Americans who were paid by Euro-American researchers eventually sought out and acquired photographs for their own use. Williams also claims that they played an important role as consumers of photographs, and that they probably exerted a degree of influence over the manner in which the photographs were taken (Williams Citation2003, 175–176).

With such perspectives in mind, Tromholt and Escard’s travel writing may indeed open up for glimpses of Sámi negotiation and resistance. It becomes evident that Sámi people were far from naïve in relation to their own role in the visual economy of scientific explorations. Their resistance to being photographed may just as well have been informed by indigenous cultural integrity and/or former negative experiences, as by irrational fear or superstition. Tromholt does account for how he is once denied access to photograph Sámi sacred places. He also recalls how people in the Sámi village, Næsseby, reacted to his camera with anger and suspicion after seeing themselves as exploited in the aftermath of an earlier scientific expedition:

I was desirous of taking some portraits of the Lapps, but it was with great difficulty I succeeded, not on account of the fog, but for another, very strange reason. It was this: that the previous year a French expedition, under Pouchet, had paid this place a visit, and having obtained some portraits of the people, published them in a French Journal. It had been forwarded to the parson, who showed it to the Lapps. Their rage knew no bounds. It was an insult to them to be thus paraded before the whole world, and they had conceived a great disgust for the noble art of photography (Tromholt Citation1885b, 289).

While Tromholt elsewhere remarks how Sámi people themselves frequently asked him to have their portraits taken, most likely for private use (images which he in turn circulated as ethnographic illustrations), his travel writing nevertheless discloses the Sámi understanding of how their images could cater for a large international market of exoticism. Many of his and Bonaparte’s Sámi sitters required compensation, for example in the form of tobacco (cigars) or money. Escard even mentions the rate for the anthropometric sessions: “une-demi couronne par tête mensurée et photographiée”—half a Norwegian Crown for every head measured and photographed (Escard Citation1886, 17).

To close this exploratory journey into Tromholt’s and Roland Bonaparte/Roche’s photographs, I will finally return to the two chosen portrait examples: the photographs of Jol Andersen and Josef Henrikson Buljo (–). As demonstrated above, both of the originators behind these portraits, the two men who travelled to Sámi areas in 1883 and 1884, took part in a wider late nineteenth century European colonial related culture of travelers, tourists and scientific expeditions. This culture was far from innocent, and cannot be understood in isolation from the political processes in which it was embedded. Neither can Tromholt be seen as an agent situated externally to this field of tension. It is furthermore a field that on one hand encompasses performances of male academic masculinity, but on the other indigenous agency. Even so, the beauty and integrity that radiate from the portraits of the two young men somehow enables them to transcend this complex historicity. They calmly face their photographers, as in premonition of their future importance, not as scientific evidence, but as visual documents of the Sámi peoples’ ancestors, and as potent objects for negotiations of a difficult past.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sigrid Lien

Sigrid Lien (b. 1958) is professor in art history and photography studies at the University of Bergen, Norway. Project leader for the Norwegian team in the HERA-project PhotoClec (Museums, Colonial past and Photography) 2010-2012, and for the project “Negotiating History: Photography in Sámi Culture», funded by the Norwegian Research Council (2014-2017). Has published extensively on nineteenth century as well as modern and contemporary photography. Recent publications include Uncertain Images: Museums and the Work of Photographs, Ashgate 2014, (with Elizabeth Edwards) and Pictures of Longing. Photography in the History of the Norwegian U.S.-migration,University of Minnesota Press 2018.

Notes

1. For digitized access, see: http://marcus.uib.no/instance/photograph/ubb-bs-fol-00621.html.

2. I have not been able to find G.Roche’s first name anywhere in the available source material.

3. According to François Escard, the Bonaparte expedition produced anthropometric portraits of 139 Sámi individuals (Escard Citation1886, 58–59). This number does not seem to correspond with the number of individual portraits in the Quai Branly-collection. For digitized access to this collection, see: http://collections.quaibranly.fr/#420db5a5-19a9-4551-8779-e57fe1daa959.

5. The portfolio titled “Tromholts Vues de Laponie” with handwritten captions in French, is now kept at the collection of la Société de géographie, at the BNF. The album is a donation from Roland Bonaparte, who served as the president of the Société de géographie from 1910 until his death in 1924.

6. Louis-Phillipe, though related to King Louis XVI, was like his father, the Duke of Orleans, a supporter of the French Revolution. He joined the French army in 1792, but deserted in April 1793. Later that year, during the Reign of Terror, his Jacobin father (who after the revolution took the name Philippe Ègalité) and his two younger brothers were executed in France. Louis-Philippe who was forced to live in exile, travelled for the following years in Switzerland, USA and in the North of Norway and Sweden.

7. Today this particular painting form part of the collections at Nordnorsk Kunstmuseum in Tromsø, Norway.

References

- Bann, S. 2002. “Photography, Printmaking and the Visual Economy in Nineteenth-Century France.” History of Photography 26–1: 1–17. doi:10.1080/03087298.2002.10443249.

- Barbara.C, M. 1985. “François-Auguste Biard: Artist-Naturalist-Explorer.” Gazette Des Beaux-Arts 127e Anné: 75–87.

- Beaugé, G . 1995.“De l’apparence des caractères au caractère des apparances. Photographie et anthropologie: 1839–1912.” Revue régionale d’ethnologie 2–4: 81–144.

- Behdad, A. 2013. “TheOrientalist Photograph”.” In Photography’s Orientalism, edited by A. Behdad and L. Gartlan, 11–32. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute Publications program.

- Bhabha, H. 1984. “Of Mimicry and Man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse.” October 28, 125–133.

- Boivin, L. 1842. Notice sur M.Biard; Ses Aventures; Son Voyage en Laponie avec Madame Biard; Examen Critique de ses Tableaux. Paris.

- Bonaparte, R. 1885. “Les Lapons.” La Nature 2,: 119.

- Bonaparte, R. 1886. “Note on the Lapps of Finnmark (in Norway).” The Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 15: 210–213. doi:10.2307/2841579.

- Bonaparte, R. 1889. “La Norvége et la Corse.” Le Globe, tome 28: 53–64. doi:10.3406/globe.1889.1683.

- Chaudonneret, M.-C. 1999. L’État et les artistes. De la Restauration à la monarchie de Juillet (1815–1833), 143. Paris: Flammarion.

- Danahay, M. 2016. Gender at work in Victorian Culture: Literature, Art and Masculinity, 1. Routledge: London.

- Dobbin, K. 2013. “Exposing Yourself a Second Time.” Visual Communication Quarterly 20 (3): 128–143. doi:10.1080/15551393.2013.820585.

- Eddy, J. H. 1994. “Buffon’s Histoire naturelle: History? A Critique of Recent Intepretations.” Isis 85, (4): 658–661. doi:10.1086/356982.

- Edwards, E. 2001. Raw Histories: Photographs, Anthropology, Museums, 212–213. Oxford/New York: Berg.

- Escard, F. 1886. Le prince Roland Bonaparte en Laponie. Épisodes et tableaux. Paris: G.Chamerot.

- Fjellestad, M. T., and S. Greve. 2017. “Sophus Tromholts verdensreise.” In Han e´søkkandes go! Et festskrift til byarkivar Arne Skivenes, edited by Botheim, Ragnhild, et al. Bergen: ABM-media as.

- Green, D. 1984. “Veins of Resemblance: Photography and Eugenics.” Oxford Art Journal 7, (2): 3–16. doi:10.1093/oxartj/7.2.3.

- Immonen, V. 2012. “Photographic Bodies and Biographical Narratives: The Finnish State Archeologist Juhani Rinne in pictures.” Photography and Culture 5, (1): 37–52. doi:10.2752/175145212X13233396185035.

- J.I. 1996. “Le Du d’Orleans recu dans un campement de Lapons, août 1795.” In Les années romantiques. La peinture francaise de 1815–1880, 331–332. Palazzo Gotico, Plaisance: Exhibition catalogue Musée des Beaux-Arts de Nantes, Galeries nationales du Grand Palais.

- Jehel, P.-J. 1994–1995. Photographie et anthropologie en France, Mémoire de DEA “Esthétique, sciences et technologie des arts”, UFR “Arts, Philosophie et esthétique”. Paris: Université Paris VIII, Saint-Denis.

- Johansen, A. 2007. “Oppdagelsesreise.” Norsk Medietidsskrift årg 14–4:363–372.

- Kyllingstad, J. R. 2012. “Hjernen, rasene og kefalindeksen.” Arr – idéhistorisk tidsskrift 1: 6–7.

- Larsen, P., and S. Lien. 2007. Norsk fotohistorie. Frå daguerreotypi til digitalisering. Oslo: Det Norske Samlaget.

- Lee, Y.-S., D. Weaver, and N. K. Prebensen. 2017. Arctic Tourism Experiences: Production, Consumption and Sustainability. Wallingford and Boston: CABI.

- Maxwell, A. 2010. Picture Imperfect. Photography and Eugenics 1870–1890. Brighton/Portland: Sussex Academic Press.

- Mayer, A., B. Lauvergne, and J. Giraud. 1852. Voyages en Scandinavie en Laponie au Spitzberg et aux Feröe. Atlas Historiques et pittoresque. Paris: Arthus Bertrand.

- Mercer, W. 2006. “Arctic Discourses: People (s) and Landscapes in the Travel Writing of Xavier Marmier.” Edda, no. 01: 3–16.

- Morris-Reich, A. 2016. Race and Photography. Racial Photography as Scientific Evidence, 1876–1980, 21. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Thingstad, E. B. 2013. “Short note on Auguste Biard’s painting “Læstadius preaches for the Sámi.” Spor nr 2:34.

- Tromholt, S. 1883. Billeder fra Lappernes Land/Tableaux du Pays des Lapons, Bergen: printed photographic portfolio.: http://marcus.uib.no/instance/photograph/ubb-bs-fol-00621.html

- Tromholt, S. 1885a. Under the rays of the Aurora Borealis: In the land of the Lapps and Kvæns. Vol 1–2. London: Sampson Low.

- Tromholt, S. 1885b. Under Nordlysets Straaler: Skildringer fra Lappernes Land. København: Gyldendal. http://www.altabibliotek.net/finnmark/Tromholt/Nordlyset.php?kap=VII.

- Unknown author. 1885. “Tromholt’s under the rays of the Aurora Borealis.” Science 5, (125): 527–529. Accessed 28 September 2015. http://www.arrvev.no/artikkel/hjernen-rasene-og-kefalindeksen

- White, C. 2014. Work and Leisure in late nineteenth-century French Literature and visual Culture. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Williams, C. 2003. Framing the West. Race, Gender and the Photographic Frontier in the Pacific Northwest. Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press.

- With, E., and A. B. Wessel. 1930. Spredte trekk fra Ludvig Philip av Orleans’ reise i Nord-Norge og Lappland i 1795. Hammerfest: G. Hagens forlag.