ABSTRACT

This article sets out to review the films of Chantal Akerman, mainly those that she made in the 1970s and 1980s, observing how her filmmaking formulates a journey to and from the home against the background of the historical scene post 1968. Through a selection of examples, I will argue that the singularities of her filmmaking—the exploration of suspended time, the preference for a frontal gaze at the female body, or the inclination to autobiography, being the most noteworthy traits—have their basis in her critical observation of the life of women in social spaces, and also in a commitment to their emancipation through desire. Seen in perspective, the path that Akerman takes is one of unstable—though coherent—movement through the rejection of domesticity as the place from which the oppression of women originates, the flight from this (in other words, nomadism), and a search for other interiors that function as the opposite of the family home. These other interiors are empty and anonymous rooms where time and the rules that govern society are suspended, where Akerman herself, or other characters who are her alter ego, go from one corporeal state to another, carrying out the basic activities of the body, such as eating, sleeping or having sex.

Introduction: Chantal Akerman’s phenomenological vein, or the importance of space and the body in her cinema

In her extensive genealogy of the uses of the bedroom throughout history, Michelle Pierrot reflected on the particularity of the women’s bedroom, a space that is especially complex as it has been assigned many functions and practices. The bedroom is a space of great interest to this historian, above all because of the changing ways in which it has been conceived by those same women who have inhabited it over time:

The bedroom is a woman’s sacred space par excellence. Everything contrives to isolate them there: religion, domesticity, morality, decency, modesty. […] [Because of this,] contemporary feminists vigorously contested the idea of enclosure as being intrinsic to women’s ‘nature’. They claimed the practice of traveling and nomadism as a philosophy and a way of life. [But] the bedroom has [also] been claimed by many women of all ages and diverse conditions, from the woman who works at home to the writer […] even the liberated women of 1968 … […] It swings from a place of constraint to one of freedom, between duty and desire, real and imaginary – distinctions that are difficult to distinguish in the semi-darkness, where boundaries are blurred.Footnote1

The career of Belgian filmmaker Chantal Akerman during the 1970s and 1980s can be read in the light of these words. The journey revealed by her films encapsulates the particular story of rejections and affinities that exist between women and the private room. Conceived in the period after the events of 1968, her films are as interested in exploring interiors, in evoking “houses, rooms, and notions of domesticity and seclusion”,Footnote2 as they are in transcending the spatial limits of those same interiors in various ways, including flight, nomadism, and even destruction. As a whole, her filmography can be understood as an exercise in “dialectics between interior and exterior spaces”,Footnote3 as a constant movement between public and private spaces, between the city and the rooms it contains.

My aim in this article is to examine this continual oscillation, which reverberates in her films, between the longing the female characters feel to escape and immerse themselves in the streets, fleeing the home, and the need, afterwards, to find shelter in suitable spaces, conceived as places of experimentation and desire, non-domestic hideaways in which to ponder the alienating logic and time that govern life (that were particularly harsh against women). Using a selection of examples, I will thus follow that route—not chronological but well-defined—that her heroines outline: leaving the home to reject it, to the point of making it explode, going out to the exterior and moving through the thresholds of modern cities, moved by the desire to find the one they love or another yearned-for subject. For here is a second original element in Akerman’s cinema that is related to this concern for interiors: her protagonists are, in many cases, women who move (through the city, the streets, or the rooms), driven by desire. Desire is the driving principle, whether they try to repress it or be guided by it. As Bérenice Reynaud states: “The originality of Akerman’s representation of women is that she shows them as active desiring subjects, even when they seem to be repressed or in a position of passivity.”Footnote4 This centrality of desire means that her cinema undertakes an appraisal, not for that reason uncritical, of the places where women live, from public to private. Similarly, this centrality of desire entails that in her films temporality does not always follow a linear or progressive pattern. In Akerman’s works, time often comes to a standstill or becomes repetitive, because time is lived according to an affective experience governed by desire. The temporal structure of the film is thus filled with ruptures and holes.Footnote5

That is why her cinema, although born of the admiration she felt for the street cinema of the French Nouvelle Vague—which had a strong impact on her—represents a significant change in the conception of social space with respect to it. Akerman’s approach can only be understood in the political and social context of the 1970s and 1980s, marked by the emergence of feminist struggles for liberation and by interest in issues related to the sphere of intimacy and private life. It is said with certain frequency that one of the greatest discoveries of modern cinema in the 1960s was the act of taking the camera to the streets. Through its forced anonymity and accelerated rhythm, through its crowds and neighbourhood people, the streets offered the perfect stage for young generations to create a new cinema focused on the concrete terrain of everyday life.Footnote6 In effect, the most daring creators of the Nouvelle Vague felt the need to take their cameras, go out onto the streets and make film sensitive to vibrant urban reality. Think about the documentary and street-based vocation of the sixties films by Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Agnès Varda or Chris Marker. At the end of the decade, the events of May 1968 entailed a profound alteration in the relationship between space and a cinema: in parallel to this street-level and public cinema, we find critical attention paid to the enclosed, private, solitary places of the contemporary world by a batch of directors who have been grouped together under the label “post-nouvelle vague”. The cinema of that period turned towards themes and areas such as interpersonal and sexual relationships, the body, daily life in the home and the private room or all those places through which subjects began to pass through.Footnote7 Marguerite Duras, Agnès Varda, Maurice Pialat, Philippe Garrel, Jean-Luc Godard and Chantal Akerman are milestones in this regard.Footnote8 But here I will focus on the career of Chantal Akerman, as I believe that, more than any other auteur of her generation, she functions as a link between the two decades, and is a prime example of this new and critical interest in interiors.

Akerman depicts and amplifies the legacy, the repertoire, of formulae and aesthetics both critical of and fascinated by the city of the French New Wave, such as filming the big city as a set of fragmentary experiences, taken from the daily stroll—or as Deleuze would say, from the balade of the main character—or the preference for places not always emblematic but common or ordinary, such as industrial or peripheral areas of the city. But she does so in the context of the 1970s. This was a period of society and life in which, on the one hand, cities became ever more hostile—think for example of the New York of the seventies she was about to film—but, on the other hand, new voices and other bodies, such as those of women, emerged to give an account of their urban experiences and to judge them. It makes sense, therefore, that Akerman’s characters are housewives, adolescents, poor people, migrants, ethnic minorities, and displaced people, who do not undertake great deeds but live through trivial situations, though they are not lacking in interest because of this.Footnote9 Upon observing their lives, Akerman leads to a reflection on some of the crucial questions that were dealt with by feminism and, in general, the critical thought of the era that is still relevant today: female oppression, the reproduction of labour, loneliness, desire, homosexuality, social marginalization, mobility, and so on. This is also why Akerman is interested in what happens inside houses, with their oppressive kitchens and their closed bedrooms, in whose beds intimate relationships are forged. She sheds light on and at the same time challenges the home, where, moreover, women worked in silence and without recognition, and where, of course, they were suffocated by the familiar. Or she takes the viewer to empty hotel rooms and station waiting rooms and travel by roads and service roads—interchange points that talk about the gradual imposition of a forcedly nomadic life that makes affection fragile. Or she has an inclination for “blank” or “empty” spaces, such as rooms in empty apartments or abandoned areas that serve as a laboratory for different practices of life. And, above all, she closes in on the body as the primary place because any experience of environment and any malaise are felt, firstly, in the skin itself. Thus, in Akerman’s films, the interiors and the bodies become the battlefield; they are political in their own right.

On the basis of what has been said so far, it is my aim to recognise that Akerman’s cinema is phenomenologically feminist cinema, that is, it gives an account of, but also leads to, another experience of time and space, one that is no longer subject to the rhythm of work or marked by oppression. Certain artists and filmmakers of her generation (such as Laura Mulvey, Helke Sander, Martha Rosler or VALIE EXPORT) propounded a laborious, activist discourse with which to recover the voice of women that had been silenced for so long, or they offered a complex critique of female stereotypes, making use of editing or other techniques under the pretext of the philosophical apparatus of feminism. Akerman, however, prefers to set language and theoretical standpoints aside, dismissing them, in order to focus on the manipulation of time, on capturing space and on the bodily movements and gestures of her protagonists. Similarly, at the same moment in which she shows this, she also reclaims and produces other postures of the body, other subjectivities and another form of erotica, beyond those that are stipulated for women. So, as Chamarette suggests, Akerman’s works, “permit an unfolding of the concerns that often emerge in a phenomenological approach. Issues of voice, embodiment, temporality, relationality are brought to the fore by the resistant, experimental qualities of Akerman’s works”.Footnote10 In her cinema, time, bodies and the places through which they glide, were gazed at directly, face to face, as political elements. I turn to Deleuze’s diagnosis:

The Post-New Wave will continually work and invent in these directions: the attitudes and postures of the body, the valorizing of what happens on the ground or in bed, the speed and violence of co-ordination, the ceremony or theatre of cinema which is revealed […]. Female authors, female directors […] have produced innovations in this cinema of bodies, as if women had to conquer the source of their own attitudes and the temporality which corresponds to them as individual or common gest.Footnote11

At the same time, let us look at Akerman’s own testimony: “In my films I follow an opposite trajectory to that of the makers of political films. They have a skeleton, an idea and then they put on flesh: I have in the first place the flesh, the skeleton appears later”.Footnote12 Alongside this interest in the flesh, Akerman also showed an interest in the body as a multidimensional entity. She gazes at the body at the same time as being seduced by it; she is desirous to show it, but is equally moved by the aspiration to take account and explain the impossibility of living in injustice and daily violence, which is revealed, precisely, in the bodies. The Belgian director patiently scrutinizes bodies, their ceremonious attitudes, their states, which are sometimes insignificant, and in other cases extreme, pausing in the quotidian spaces through which they pass and implicating the viewer in their physicality. This phenomenological vein emerges partly thanks to a singular combination of the language of minimalism and structuralism—trends that she may have learned about upon her arrival in New York at the start of the seventies and that were strongly influenced by dance and performance. This is combined with concerns of a social nature, linked to the problem of seclusion and alienation that originated both from her biographical data (Chantal is a woman, Jewish, middle-class and her family had been sent to Auschwitz) and from the cultural, politically turbulent atmosphere of Europe after May ‘68, which took place when she was a teenager.

The mechanical house, literal time and a knife, or the overwhelming minimalism of Jeanne Dielman

Akerman’s journey or journeys (better to say it in the plural) rarely respect chronological order, for these are primarily interior journeys rather than of a spatial kind. Therefore, in order for me to tell this story, I do not need to start from the beginning either. It makes sense, conversely, to skip lightly over her first films—which date from 1968, and which I will turn to later—and place ourselves right in the middle of the decade, in 1975,Footnote13 the year in which she completed her best-known film, Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. Here, she undertook the most complete and rigorous examination of female isolation in that place, the home, that was historically constituted as primordial for women. And although this may not be her first work, it is in reality her point of departure.

With such a descriptive title, so transparent and so typical of conceptualism, Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles is just that, the life of this woman in that specific house and nothing else. Moving between documentary and fiction, description and action, for more than three and a half hours the film shows the anodyne and implacable routine of Jeanne (played by Delphine Seyrig), a young widow and housewife who tidily splits her day into two: in the mornings she takes care of domestic chores with monastic discipline, and, when it turns to afternoon, she works as a prostitute with equal diligence. With the camera positioned slightly lower than normal, on a tripod at waist height, shooting entirely front-on and slowly tracking Jeanne’s movement, the film refuses to take any psychological tone, focusing on the obsessive recording of the repetitious labour of the woman, which tends to take place in the kitchen or the bedroom []. As has been commented, “Akerman’s static camera visually limits the space in such a way that both the setting of the apartment and the camera create the effect of a cage”.Footnote14 This apparent insipidness and that demotivated camera were already an insult to the hierarchy of cinema, since what is found here is what would be considered waste in any traditional film:

I do think it’s a feminist film because I give space to things which were never, almost never, shown in that way, like the daily gestures of a woman. They are the lowest in the hierarchy of film images. A kiss or a car crash comes higher, and I don’t think that’s accidental. […] I let her live her life in the middle of the frame. I didn’t go in too close, but I was not very far away. I let her be in her space. […] But the camera was not voyeuristic.Footnote15

Little more than these actions, which for traditional cinema are disposable can be seen; they are the actions that make up the existence of a woman. “I made this film to give all these actions that are typically devalued a life on film,” said the auteur.Footnote16 Certainly Akerman shows them with such a degree of fidelity that time is made literal. That is to say, Jeanne’s chores in film time last exactly the same as in real time. If Jeanne takes eight minutes to prepare a piece of meat, the viewer must endure those entire and unavoidable eight minutes, because that is simply what it takes to cook that meat []. Akerman always fixes upon the most banal surfaces, although her intention is to subvert them. Every peaceful relation with the surrounding space yields before this time, which falls under its own weight. Therefore neither psychologism nor melodrama of any type is needed. Only an emotional minimalism: what you see is what you see, until for you, the spectator, it is also unbearable. This is, I could say, a subversive or existentialist variant or the direct and aprioristic treatment of space-time in minimalism. Akerman explains it in her own words:

You know, when most people go to the movies, the ultimate compliment—for them—is to say, “we didn’t notice the time pass”. With me you see the time pass. […] You also sense that this is the time that leads toward death. […] And that’s why there’s so much resistance. I took two hours of someone’s life. During this time we feel our existence.Footnote17

During that time of everyday existence, Jeanne marinades the meat for the dinner, she peels the potatoes, opens a window, closes it, or she receives and services a client in her bed. Both in her treatment of time and in her filming, so flat and meticulous, of the ordinary, Akerman is flirting with the idea of familiarizing things to make them strange, unheimlich.Footnote18 “Every view of things that is not strange is false,”Footnote19 said a graffito in the Sorbonne occupied by the soixante-huitards, retrieving a quote from Paul Valéry … So, everything happens as if the feminists had wanted to paint on the walls of their kitchens and bedrooms, because the true political triumph would have been to take those slogans to any other place as well as the streets, and some of that spirit is recognizable in this film. Thus, the director observes, describes and questions the ordinary through detailed analysis until its reverse emerges:

I’ll put the camera there, in front, as long as is necessary and the truth will appear. […] that cannot be said except by taking it to the end, saying it in halves, as Lacan suggests. […] When we show the things that the whole world has already seen, perhaps, then, at a given moment, we start to see for the first time. […] Suddenly, in one blow, without warning, we feel that something appears that could be, at the same time, pleasure or fear, or a heartbeat. So either we close our eyes and leave or we accept this upheaval.Footnote20

In effect, here we only see the most normal things in a rigid present and in a home that functions as a perfectly oiled machine, where nothing moves, much less the countenance of Jeanne. Once edited, these almost autonomous sequences form the story of Jeanne’s life. And the story is nothing more than her own body in movement, because Jeanne does not have a voice, she only has her mechanical body, always working, a body that a body that is seen so directly from the front, when she cleans or showers, when she cooks or has sex, when she moves around the house, who seems to say that this is all she has and that, in this, the entirety of her story is contained. “Chantal Akerman’s novelty lies,” Deleuze reiterates, “in showing in this way bodily attitudes as the sign of states of body particular to the female character, whilst the men speak for society, the environment, the part which is their due, the piece of history which they bring with them […], a female gest which overcomes the history of men and the crisis of the world”.Footnote21

Everything speaks of the fact that Jeanne’s time has no frontiers, it is that unproductive time of the productive, which is prolonged day and night without break. She is an engine that does not stop. What Akerman has done is to reveal, precisely, the void that it leaves her with, that black hole that never gets sutured however much Jeanne fulfils her hours and displaces her energy with any chore. “These are not ellipses,” says Ishaghpour, “that depend on a story, but black holes of time between shots”.Footnote22 Curiously, or logically, one year earlier, Marguerite Duras, then with a way of thinking that was so similar to Akerman, and who had no doubt that “it is in a house that one is alone”,Footnote23 considered that the act of showing these holes in time that are sensed in the domestic space was linked to a destructive impulse:

M. D.: … it’s a little like a film that’s inside out, meaning that I show everything that normally isn’t shown [like doing the ironing, the laundry, the dishes]. Like the negative of the usual film where women come into play. […] It was time, the passage of time: they eat, the children leave for school, the husband goes away, they telephone, there are the two or three small chores, they clear the table, they wash the dishes, the dishes are put away, and then presto … there’s emptiness, free time; the women have two or three hours in front of them, empty, like that.

X. G.: The house needs to be destroyed.

M. D.: Yes. Footnote24

In Jeanne Dielman, that void, like everything in that house, is certainly loaded with anguish. This is a horror film, quotidian terror of course, but not the less terrifying for it (quite the contrary). Akerman once confessed that she had written the script as a nouveau roman, keeping herself totally on the outside, a little à la Robbe-Grillet, one might say. Except that things are an exterior (of an interior, don’t forget), and they are extremely strong signs of Jeanne’s perfectly normal hysteria. In this minimalist choreography or—perhaps it would be better to say—in this domestic mechanism, everything is full of meaning: every object that decorates the living room, every kitchen utensil, every gesture of Jeanne’s is a symbol of her oppression, a muffled scream. Her home is sinister because everything bears the mark of her absence of desire. She has organized her routine in such a way that she has no time left for anything else, not even to desire. There is no time, clearly, for her desire, nor is there a minute in which Jeanne lets chance decide. “Free” time to think could unleash catastrophe and that is something Jeanne fears. She has filled up her life to the point that the only thing left is to wait for it all to blow up, for the machine to short-circuit. This accident will take time, but when it comes it will change everything. And, not by chance, the event concerns a release of female libido, for, as the director would say, “things can explode into pieces when sexuality comes into play”.Footnote25

In one of her meetings with a client, Jeanne seems to feel something different, perhaps an orgasm or, in any case, some pleasure that she understands as an intrusion into her small, ordered universe. It is then that the film changes its course, and a series of disasters unfold, to which Jeanne, distressed, does not know how to react. She has burnt the potatoes, her hair is unkempt, she has left the doors open and her kitchen is somewhat messy. Jeanne is desynchronized, her time has shattered and, suddenly, time starts to pass, to tell something. As Margulies argues, “After the first link is established between Jeanne’s disheveled hair (the obscene) and the burned potatoes (the scene), there is no way back. […] Jeanne’s breakdown […] is staged mostly as a struggle against objects”.Footnote26 But not only is there a struggle with the things in her house, but also with her clients. Flustered by the sexual pleasure that proves to be intolerable for her because it changes everything, at the end of the film Jeanne coldly stabs the man with whom she had had sex for the second time, again pleasurable. After stabbing him with a knife with the same nonchalance with which she had kneaded the meat, Jeanne stays for a long while in her living room, sitting down with a lost gaze and her hands stained with blood, in what seems to be the only moment that she has stopped to think []. “Is [Jeanne] a hysteric or a feminist revolutionary?” Margulies wondered. It will never be known, although it can be intuited, through Akerman, that she is somewhere between the two: “It is the last freedom of not taking pleasure that condemns Jeanne” [in the original: “C’est la dernière liberté de ne pas jouir”], the director reasoned.Footnote27 There is nothing in that house, it seems, nothing that will help Jeanne come out of herself; the only thing left to her is to take the knife in the most destructive act that exists: the murder that is, above all, an assault against her own desire.

Subjectivity in fugue: rejection of domesticity, between explosion and flight

How not, therefore, to understand that strong need, in Akerman, to reject the spaces assigned to women and the objects they contain, whether by denouncing them, as she does in Jeanne Dielman, as the sign of what is unbearable and the hallmark of social and sexual repression that women suffer, by escaping them, or by blowing them up, as happens in Saute ma ville, the auteur’s first film, from the vital year of 1968. She said of this film that she could play with the idea that the protagonist was Jeanne’s daughter, an unruly adolescent who does everything that her mother would not dare to. This is a short film set in a block of flats on the outskirts of Brussels, where a singing Akerman enters and, like a bull in a china shop, starts to turn everything upside down in order to make some spaghetti. Close to the Chaplin- or Keaton-style character, or to the clumsy-mannered antiheroes of Godard or Beckett, she is an “anti-Jeanne” in every way.Footnote28 “The burlesque,” Akerman stated, “is subversive, above all in the domestic space, my speciality. It means altering the order, even when putting things in order”.Footnote29 After getting up to a lot of mischief (throwing all the pots onto the floor, chucking around the dustpan and brush, and so on), and after looking at herself for a few seconds in the mirror, she turns on the gas until the whole kitchen, with her inside, explodes []. Akerman described her intentions as follows: “You see an adolescent girl, 18 years old, who goes into the kitchen and starts to do the most infra-ordinary things, but as though half-heartedly, and she ends up killing herself. The opposite to Jeanne Dielman: Jeanne represents resignation. Here we encounter rage, death”.Footnote30

“I began to sense the smell of death,” said Jean-Paul Belmondo in Pierrot le fou (1965), that film—part dynamism and part desperation—that marked a whole generation of discontented youth. Akerman repeatedly confessed that she decided to study film the day she saw Godard’s great work in a cinema in Paris.Footnote31 That tragic sensation in Godard’s hero of an alienated present, turned into energy and violence (even against himself), infects Akerman, and it is intensely tangible in the Belgian director’s first films. She takes up that violence, latent but stark, and she does it at a fraction of the total explosion that both the auteur of Pierrot le fou and other modern filmmakers had been denouncing since the end of the 1960s. But, in her case, this is perceived and felt above all in private enclaves and always as though it came from within each person. In contrast to some French New-Wave cinema, which was very much at street level, fused with an exterior in turmoil and conflict, Akerman works alone from an interior. Yet it is not exempt from strong aggressiveness for all that, in a desperate attempt to get out of those houses, to no longer see those objects that furnish them. For her, the revolution is not the shout of a dense mass that fills the streets with people, but a much more silent (though necessary) attempt to escape from that enclosed state that is the psyche or the body itself. Thus, as in Pierrot le fou, Akerman blows her head off, though obviously not on the island of Porquerolles after having her heart broken, but in the kitchen of her grey and sad suburban apartment after throwing her cat out of the window and without apparent motive. This attitude of rage (certainly, singing, burlesque, jovial, but none the less frenzied for it) to the point of death, can be associated to the mushroom cloud of purifying fire with consumer objects flying through the air in the middle of the desert in Zabriskie Point (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1970); except that now, newly, the most interesting thing is that in Saute ma ville that fire is lit by a girl.

Perhaps, in the seventies, the kitchen, familiar spaces, all that private, enclosed world of unseen labour, had to be made strange and even demolished until completely losing their meaning. It has been said, perhaps because of this, that “by blowing up her kitchen, Akerman figuratively blows open women’s historic space: no longer confined to the kitchen, women’s gender roles may change and expand”.Footnote32 And so, with her short film, she anticipates the feeling of a later generation. How can one not recall here the well-known video by Martha Rosler, Semiotics of the Kitchen, which dates precisely from 1975, and in which the artist transgresses the domestic “meaning” of kitchen utensils by taking them to speak of the frustration of those who use them? How can one not think, to take another example, about the violent sex that Pierrot and Sandrine have in the kitchen in Numéro deux (Jean-Luc Godard and Anne-Marie Miéville, 1975)? Or about the arguments of Roswitha and Franz in their kitchen in Gelegenheitsarbeit einer Sklavin (Alexander Kluge, 1973)? In these films from the seventies, priority was given to recognizing a materiality in quotidian spaces that they effectively had but, in an instant, it could be that someone sets fire to all those objects, as happens in this short, or that someone flees from them.

In fact, parallel to the interest in/rejection of the domestic, from the seventies onwards Akerman pursues another line in her work, politically defiant because it places subjectivity in process, a process normally represented through the image of exodus and the search for what one desires (although this, sometimes, can be frustrated). The power of these films lies in the fact that they are no longer content to denounce alienation but to deploy a transitive character, a subject that yearns and seeks what is far from the machinal and patriarchal family home. The films thus acquire the consistency of a subjective becoming, passage or process. It is not linear because of that, although it continues to make sense; rather, it is full of fluctuations, absences and returns—in other words, of contradictions. This also explains the spaces and rooms that her characters pass through in the more autobiographical films, in which, unlike Jeanne, the protagonist is not a deranged older woman but that young rebel who takes flight. Her new heroines no longer have any attributes other than that of being “a roving body in search of love and subject to a growing confusion between the past and the present, what is objective and what subjective: the roving body as a place of exploration of the visible”.Footnote33 Her characters undoubtedly lack something and go in search of it, and although what is sought and desired is there from the beginning (as it is nothing more than the primary drives such as eating or loving, finding the other that is there in the self, obtaining a refuge, returning to the motherFootnote34), that journey of flight and return is necessary, because it involves an alteration of consciousness.Footnote35 But what always remains between journey and journey, between room and room, is a gap, a spatio-temporal interlude that does not appear to have consistency because it is what remains between one quest and another. I say again: desertion is inevitable, even though the young nomad must accept solitude and the possibility that it may surprise her on the way, and even though, from afar, she feels the need to take up the bonds of origin again (hence the profusion of letters, messages and calls homeFootnote36). Above all, she feels anxious to construct a new idea of liberating intimacy and privacy, one that will never again deny desire, including the desire that had been forbidden up until then, lesbian desire. Having fled, she will have to make herself a home—in other words, a new way of being present in and experiencing time, space and body, in a place of one’s own.

In Akerman’s career, the first example of a film along these lines is Je, tu, il, elle, from 1974, a black-and-white film about three moments in the life of a young woman (none other than Akerman herself, again) who leaves a room, begins a journey by road in which she shares the journey in a lorry and coffee with a stranger, until she reaches the house of her lover, with whom she makes love and spends the night. Her peripatetic self-discovery is divided into three sections of analysis: “Time of Subjectivity”, “Time of the Other”, and “Time of the Relationship”, which correspond with the personal pronouns that give the film its title. At the beginning, in the scenes that could correspond to the first two pronouns “Je” and “Tu”, Akerman appears naked and alone in a spartan room, barely furnished by a chair, a bed, a mirror and some blankets. Gradually the pieces of furniture disappear, first pushed against the wall, then moved to the corridor, until only a mattress remains on the floor []. Lying on it, Akerman writes letters, compulsively eats little spoonfuls of sugar, orders handwritten sheets of paper on the parquet floor, gazes outside and at her reflection in the window, sleeps, feels herself breathing, strolls around the space, goes back on these actions, narrates them, undresses or looks attentively at a point. Akerman uses a Beckettian repetition of gestures, postures and noises that, in their overloaded simplicity, work to explore the limits of the body. The framing is always kept front-on and slightly below the eyes, I would say, if not at floor level, at least at waist height. It is as though time is dragging on, made long to take in Akerman’s movements, although in this case the cuts are much more frequent and never fall into the still literalness of Jeanne Dielman. Through this sort of filmed performance in which she undresses, at the same time as she undresses her room, Akerman dramatizes her anxiety for getting rid of everything unnecessary, including the psychic burden that everyday objects can contain. The room, as the auteur herself confesses, is left in nothingness, in space-time and body, three denuded walls from which, moreover, there is the possibility of escaping:

The room, still space-time. There is almost always a corridor that leads to the room. And the room to a corridor. From day as from night. Sometimes the room is empty. Sometimes there is a body in the room. Sometimes two. Sometime a body is rejected, sometimes it is given. Sometimes it eats some sugar, sometimes it writes. Sometimes it leaves the room never to return again.Footnote37

In the room not a single object remains, not one thing to serve as a repository of the person who inhabits it. Only the window, that serves as a mirror, returns her gaze, giving her an image of her body before the departure. This is not by any means the only case of a women contemplating herself, being confronted with her own image, with her reflection, and then an event taking place, whether in the form of an explosion, a flight or the taking of a decision. It happened like this in Saute ma ville, just before the explosion, or in Jeanne herself, who before murdering her client, gets dressed in anguish in front of the mirror on the dressing table where there is also a photo of her and her husband. It also happens in L’Enfant aimé ou Je joue à être une femme mariée (1971), a short film about a single young woman who looks and looks at herself in the mirror, doubtful, because, according to the director, “she is debating between motherhood and a narcissist femininity”.Footnote38 The same could be seen in Le 15/8, a little known film co-directed by the Belgian with Samy Szlingerbaum in 1973, which is a long monologue of a girl who spends her time in a Paris apartment, smoking, gazing at herself and voicing her own reflections. From this point, it will be easy to find all kinds of split reflections and images in train windows, hotel bathroom mirrors and shop windows in the journeys her heroines make.

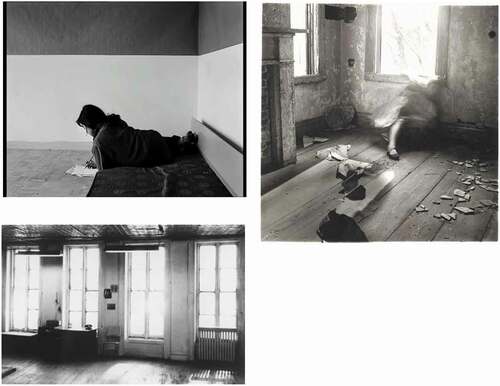

It makes sense, therefore, that in Je, tu, il, elle, only the mattress, a blanket and the window that plays at being a mirror remain. It could be said that the room becomes something akin to a domestic blank space that lends itself to childish and repetitive experimentation—eat, walk naked, sleep, look for the other (in this case through the letters) or not do anything—but always in a tremendously physical, bodily way. In short, the only thing left there, in that room, is her body, which gives a series of minimal gestures that seem to represent a performance. In fact, some authors have recognised, in these first frames of the film, an air of kinship with the works of artists such as Francesca Woodman or Lili Dujourie or the actions of dancers such as Trisha Brown and Pina Bausch (with whom Akerman herself would collaborate for the documentary, One Day Pina Asked).Footnote39 This work is similarly made up of a series of minimal gestures and small bodily rituals that unfold in those “spaces of the possible”, in the New York City in the crisis of the seventies: abandoned factories and buildings, warehouses, plots and strips of wasteland, rooftops, all empty places, heterotopic spaces loaded, in the eyes of creators, with poetic and political possibilities [].Footnote40 Certainly, this room is also reminiscent of the one in Wavelength, the influential film by Michael Snow that Akerman came to know in her New York years and that is a continuous zoom across space, a valid excuse to explore time, lighting, sensations and the psychedelic effects of cinema [].Footnote41 However, as Catherine Fowler has pointed out:

A distinction must be made between Akerman and Snow here: If Snow carries out his work purely in the name of a structuralist experimentation, then Akerman’s stance is inflected with a sense of her sexual difference. Although both film-makers might claim to challenge the ‘patriarchal’ nature of the apparatus it is only Akerman who offers any real alternative for women.Footnote42

Figure 6,7. Upper-left corner, frame of Je, tu, il, elle, Chantal Akerman, 1974. Below, frame of Wavelength, Michael Snow, 1967. Above, on the middle, photograph of Francesca Woodman, house #3, Providence, Rhode Island, 1975–76

In Akerman, beyond this desire to expand the field of vision (that is characteristic of minimalism and conceptualism) there is always a conflict that concerns the life of a woman. In her rooms, a woman’s body is always wandering around. Or, as Margulies writes, “minimalism here becomes a willed form of defining the self”.Footnote43 Therefore, in Je, tu, il, elle after this intense ritual of dispossession, of this encounter or dialogue with the self (and with the other that is implicit to it), which occurs in the space of a deserted room, the protagonist goes outside [] . She first comes across a lorry driver (Niels Arestrup) who agrees to take her, but in turn he—although the agreement is always tacit—tells her of the life and sexual miseries that he is undergoing in his family life, in a long monologue that Akerman listens to in silence, as she remains when he asks her to masturbate him. They make a few stops at roadside bars. Finally, one night, the young woman arrives at the house of a girl (Claire Wauthion) whom she barely speaks to but whom, without a doubt, she knows. Without speaking, they feature in a small ceremony of reunion carried out through various looks and gestures, until she offers Akerman dinner [] and they end up making love in a room at the end of the film, in a scene twenty minutes long that is shot with few cuts and front on so that the bodies in movement, on the bed, take up the whole frame [].

This film is a rite of passage, “it proposes an instability between private and collective, internal and external, subject and object, author and character. […] [This] radically unstable representation of subjectivity proposes the possibility of a ‘mutant’ being”.Footnote44 In this way, the notion of space also seems mutant: if, in Akerman, the interior of the room does not reflect the soul of the subject, but is a place of exploration of the other that forms part of an as yet unknown self, the exterior barely has consistency, it is only a gap until reaching another room, another bed, where to take refuge again. Like Jeanne Dielman, this is also a film about a silent woman but on the edge of a roar, whose instability is recognizable in her body long before her words, which are so few and so unnecessary. Thus it has been highlighted that “he, the lorry driver, talked, and his speech travelled as the kilometres went by. They, the women, on caressing one another, transform speech into desire, into intimate confessions: it is the body that speaks”.Footnote45 It is the story, in the words of its author, of “a character outside society, desperate, who expresses, gesture by gesture, in a kind of secret decision, a mute desperation close to a howl”.Footnote46 Only that this time, there does seem to be a way out, one that does not end in a denial of desire, in its knifing, but rather desire is unleashed when it is sought. This interior becomes a place without rules, which lends itself to the activities of the body: eat, sleep, have sex. After the nomadic journey and the ceremonies of self-knowledge and after having been in a simple bed almost deprived of furniture, this is no longer a family home but a space for the satisfaction of desire and therefore eroticized. It is a point where the law seems to be suspended, I could almost call it a pre-symbolic space, in which time is no longer mechanical or controlled or divided up in some way, but time is left to run. As regards the protagonist’s body, it has ceased to be that machine on the point of exploding, and instead becomes a body in movement that takes pleasure.

From this wandering woman who tries to free something within, let move on to another that also conceals an internal struggle; from this journey of consciousness, from this shift of the self, let move to another search, perhaps this time somewhat more nomadic. In 1978 Akerman completes one of her most successful films of the decade, Les Rendez-vous d’Anna (1978), which shares this fugitive and fragile spirit that characterizes Je, tu, il, elle. In Les Rendez-vous d’Anna, an evidently autobiographical influence is likewise recognizable in the wish to get outside, in that principle of separation from the home that is, also, a farewell to social norms and roles, shifting toward an erratic movement in which, at heart, what beats is desire. With a mise en scène and use of time that are much closer to traditional codes, she narrates the journey of Anna, a lone and introverted film director, through Cologne to present her film and her subsequent return to her home in Paris, passing first through Brussels to visit her mother. Dragging herself from hotel to hotel and station to station, throughout the few days that her trip lasts, Anna—which was Chantal Akerman’s second name—has encounters with a few people she meets on the way: a sometime German lover, a friend of her mother’s, her mother, a stranger on a train, and, lastly, another lover, maybe her boyfriend, now back in Paris, with whom she spends a night in a hotel before arriving at her apartment []. Her apartment, in fact, has almost the same soulless appearance as all the rooms she has passed through until then: the empty fridge, the dark and sad corridors, the minimally furnished rooms, the mattress again on the floor, while messages accumulate on the answerphone due to her absence [].

These encounters of Anna’s, which always take place in cold and depersonalized spaces, are marked by a severe lack of communication, emphasized by Akerman’s rigid, symmetrical and tremendously distant framing []. The conversations pass interspersed with long periods of uncomfortable silence. In these shots, there is no beginning and no end, they are shots that depict a discourse or a non-action, there is never an idea of temporal progress. Moreover, the objects that she handles are also “transit-objects”, telephones, coffee cups or suitcases. The constant swaying of Anna’s body between windows, shelves, counters and waiting-room seats or somebody else’s mattress, reveals her fatigue and disorientation. Anna listens patiently to the monologues of others, she is present when they tell their stories and complaints about the hardship of the economic crisis that has battered Europe or the wounds left by the war, and endures the advice that her mother and the friend give her about the virtues of marriage: “Being alone is not living, above all for a woman”. Silent and impassive, Anna does not seem able to assimilate what she receives from others. She barely speaks and, when she does, it is to barely nod or to sing, and she hardly rests at night. She barely responds and barely eats, she just moves from one place to another; she bears the long periods of waiting in thought.

The matter of food is not in any way trivial in the Akerman universe. Rather, allegorically, it functions as one brick more in that generational wall that separates baby boomers from their parents and that does not stop being, in spite of everything, a breach in the way of living. Akerman’s young women refuse to eat healthily or in an orderly fashion: either they eat the minimum to survive (for example, in Les Rendez-vous, Anna hardly pauses to eat breakfast, and it has been seen how the protagonist of Je, tu, il, elle basically lives on sugar, while in Portrait d’une Paresseuse (Ishaghpour Citation1986) she eats vitamin pills), or they compulsively eat as much as the city offers them. This austerity or mess contrasts with the strong presence of food in the maternal home, where it functions as social ritual that orders the hours. This is what happens with the coffee and the dishes that Jeanne Dielman prepares every day and always the same way, the meals with meat always so present in front of the camera lens; or it takes place with the almost obscene profusion of cakes and food on the lounge tables in Dis-moi, a short film from 1980. Here, upon her arrival in Paris, a young Akerman interviews a series of elderly women, the age of the previous generation, who having survived the Holocaust settled in the French capital and now do not want, cannot, do anything other than scare away any shadow or remembrance of hunger with their copious meals. Akerman herself reminisces:

For the generation that sacrifices itself, to eat was what mattered, you had to eat. You had to fill up the fridge, dress decently and warmly, you had to furnish the parents’ room and the children’s room with sheets and bedspreads and it had to be done well. To achieve this you had to make sacrifices and work hard, get up early every day of the week and even do likewise on the weekends. Suddenly I stopped eating. […] It was a way of turning against the sacrificed generation. A revolt that I turned on myself. […] Without knowing it, I did not want to form part of that food and that sacrifice. What I wanted was to sing and go on my bike and run far away.Footnote47

And that is just what Anna does: escape from those houses with bedspreads and full fridges, not paying attention to them. Anna is very distant from all of that world. During her entire journey, however, she appears meditative, thinking, perhaps, about the only person with whom she had an intense encounter and who is present in the film inasmuch as she is absent: an Italian woman whom she made love with on another business trip and whom, since then, she has been looking for constantly but in vain, through messages and phone calls that are always cut short. The secret of this lesbian encounter that Anna yearns to repeat—and which the spectator learns about thanks to the confession she makes to her mother—gives the clue to understanding the melancholy that her face emanates. But it also helps to understand her rejection, or, at least, her non-correspondence with all that domestic, familist and heterosexual universe that tries to impose itself upon her and clashes with a desire, feelings and life such as hers. Anna therefore sees herself heading towards being placed on the margin, to being a foreigner in her own world and to becoming nomadic from city to city, to silence. But she knows that the path is full of doubts and involves contending with alienation, solitude, disillusion, and fragility. These appear to take shape in the coldness of her apartment. Because of this, “Anna has […] a deep anxiety, an insecure identity”.Footnote48 In effect, far from any fetishist view of transnational travel or of any approach to the identitarian or closed subject, not even excessively activist or enraged with regard to gender roles or sexual identity, Akerman sets forth a liminal imagining of identity. She restricts herself to examining characters, normally women, in circumstances and spaces marked by instability, for the purpose of exploring their movements, observing their desires and listening to their silences.

Arriving in the big city, returning to the interior

Alongside these films of journeys, Akerman’s films also deal with the sensations produced by arrival in the city, something which she herself experienced on many occasions and that again brings about that double movement toward the exterior and the interior, toward the street and one’s own room. In her arrival in New York in November 1971, Akerman finds an adverse and socially atomized city that she gazes at, as she would with any other place, with the eyes of an uprooted loner who roams through hotels, subway stations and station cafés, struggling with the precariousness of such a life.Footnote49 In her filmmaking, the American city is a place of arrival, equally hostile and seductive. With the help of Babette Mangolte and strongly influenced by the structural cinema of the New York scene, Akerman submerged the camera into the cracks of a New York that was then in full social and economic breakdown.

In Hôtel Monterey (1972), a silent film, she documents a full day and a night in a cheap hotel where society’s vulnerable spend their days and nights. The camera moves patiently through the rooms, corridors and terraces, observing the hotel’s guests from the distance that the silent and far-off framing gives []. They do not do anything, they do not move, they limit themselves to being there and the spectator waits with them for the time to pass, which, as in Les Rendez-vous d’Anna, seems to be that temps mort of still observation. The strong presence of doorframes, windows, doorways and thresholds of all types, combined with the subdued brownish-grey light, imprint onto the image the same atmosphere of waiting and solitude that can be found in an Edward Hopper oil painting.Footnote50 With symmetrical posture, alert to the materiality of quotidian space and to ordinary people, the young filmmaker also went outside and began to document the streets. In News from Home (1977), the fixed camera draws up an inventory of the underground galleries and subway cars, the streets along the docks that relocate the viewer to a city whose consistency is made of the anonymous flows of people who pass through it every day []. Akerman’s detached voice reading the letters that her mother sent her from Belgium resounds over these takes and constitutes an attempt to establish a connection with home, a tie between these two spaces, which are also two forms of life, and two stages, the origin and the arrival, so far from each other.Footnote51

Years later, the director would insist on this account of the arrival of the lone and vulnerable adolescent in the great city, which receives her with a certain aggression in that nothing is made easy there and everything costs too much effort and money, but which will soon be her natural setting. This is the case of J’ai faim, j’ai froid (1984), a short film little longer than ten minutes whose eloquent title distils the brief story of two girls who arrive in Paris with just enough money and tobacco for a few days. Their strolls and conversations revolve around the basic drives that they feel: eating without pause, smoking, keeping warm and finding someone to love []. The two girls leap from their bed in a cheap attic to the bed of some young men they meet in a bar, and the rest of the time they walk aimlessly, looking at shop windows and trying to get money. At the end of their adventure, they get lost in the night walking along the streets, and nothing more is known about their final destination. What is certain is that the way they live the city is through these desires and in this state of precariousness, alone, in their almost clochard state. Akerman documents the hardness of the urban environment but the affable tone and humorous moments make think that she does not completely deplore the adverse circumstances inherent to urban life. Rather, to a large extent, what she has proposed is to film what it means to experience and explore a city when one is young, seeking a roof and a bed.

This mix of freedom and inclemency, this need to find a refuge in the streets, this wandering of the characters in thresholds, entering and exiting the interior but moved by desire is, again, the kernel of the plot of another Akerman film that is notable in this respect: Portrait d’une jeune fille de la fin des années 60 à Bruxelles (1994). Suffused with the feelings of the late sixties, specifically set in the crucial year of 1968, but filmed in the Brussels of the nineties, the film follows a day in the life of Michèle (Circé Lethem), a disorientated young woman who does not want to be at home with her parents or go to school, so she decides to spend the morning in a cinema. There she meets Paul (Julien Rassam), an army deserter, and they spend the whole day together walking, talking endlessly, kissing, sharing anxieties, mixing their thoughts. Together they think about issues such as: social alienation (“when we work we will become grey beings”); the possible coming of that revolution that ’68 was going to be (“everything needs to blow up, we are suffocating. And when everything explodes it will be different, it will no longer be obligatory to get married or dress well”); the severity of the family and the suffocation that the domestic dwelling produces (“I can’t bear Saturdays any longer and I leave home”); and, of course, sex (“The great matter of life is sex”). She has run away from her parents and he from the state, and they have nowhere to pass the time, nor him the night, other than in public places or the house of an aunt, where they enter on tiptoes to end up making love []. The film gets underway, precisely, with a symbolic suspension of law, as in her first appearance Michèle reads out forged letters from her parents in which she invents—and it could be said that she fantasizes about—the death of some relatives, among them her father, as an excuse for her not attending school. Similarly, the army does not know of Paul’s whereabouts. The couple would like to stop time, which is as blurred as they imagine the future, or perhaps they wish to accelerate it, so that the revolution they long for explodes and their future becomes clear.

Figure 17. Frames of Portrait d’une jeune fille de la fin des années 60 à Bruxelles, Chantal Akerman, 1994

In addition to this, Michèle’s confusion about her sexual orientation throbs throughout the film, adding another layer of meaning, if not the most important, to that very particular confusion and that symptomatically is felt in the very arrangement of the film, made of phrases, looks, and strolls without order. With the passing of minutes, it is suspected that, in reality, she is in love with a female friend, with whom, at the end of the film, she shares a silent but revealing dance and exchange of glances, although they are separated shortly afterwards []. Michèle is one more on that list of unstable women who fill Akerman’s films, women who are exposed to perilous circumstances, still undecided but somehow anxious to know where their desire is taking them.

Figure 18. Frames of Portrait d’une jeune fille de la fin des années 60 à Bruxelles, Chantal Akerman, 1994

The structure of the film is a long balade through the streets of Brussels, full of dialogue and in the purest style of the Nouvelle Vague, and it is even recognisable some nods to À bout de souffle (Jean-Luc Godard, 1960) []. Her attraction to peripatetic characters who are immersed in the urban hubbub, hopping from café to café and filmed with a handheld camera, is Akerman’s inheritance and tribute to the French cinema that she loved in her youth. But let us not forget that this is a film made by a woman post-’68. This means that, on the one hand, the space of the city is always judged according to its relation with an interior, and, on the other, that the main concerns are the private and the libidinous. In other words, these are issues and perspectives that only fully entered the political landscape in the decade of the seventies thanks to feminism and other radical movements (such as the movements fighting against the oppression of sexual minorities, psychoanalysis or the anti-psychiatric movement). Thus, apathy and social suffocation take the form of a critique of the oppression and narrow-mindedness of the family and its domestic space, and, by extension, of that life governed by the rhythm of work. It likewise appears in the aspiration of young people to live in a more liberated sense, more desired, as well as to find their place in the world and in the city. The city is not made for them, it does not belong to them, they have little money, they frequently walk through it against the current of the crowd. However, in some way they succeed in making it theirs, of delighting in it, although they are always seeking somewhere indoors to take refuge.

Turning time upside down: night and day, desire and laziness

Exactly this eagerness to hurl oneself into the urban jungle, but always trying to find a private corner within its undergrowth, continues to be the plot of many other films by Akerman. Except that perhaps it is perhaps possible to distinguish a trend, slightly singular, in which, before the wanderings, the Akermanian aim of turning the experience of time upside is made foremost. This is a confronting of the temporal norm in favour of the powers of desire and the passions of the body and upon the backdrop of a rejection of the drabness of salaried work.

The best example of this is Nuit et jour (1991), which presents the story of a young couple, Jack and Julie, arrived from the provinces in Paris, where they move into an apartment that will be the setting for their love story. In this almost deserted apartment (where there are only beds and the odd chair), they try to create, with little rules and agreements, the rhythm of life in their own making, believing that in their routines, love must always be the axis along which life should be ordered. As Jack works as a taxi driver at night, they spend the daytime together, essentially to make love. This is a minimalist film to the extent that it explores, largely, one emotion, sexual desire, obsessively []. Soon, Julie meets another taxi driver, Joseph, with whom she begins to spend the nights, thus completing the ménage à trois that, in the style of Jules et Jim (François Truffaut, 1962) []. Although it takes a narrative form and is punctuated by the voice-over of Akerman herself, the film is formed more by creating an atmosphere and a sensation than by telling a story. The lyrical tone, always very far from being moralistic, concentrates attention on the observation of the bodies of the protagonists in their amorous rituals and in their conversations, which frequently take place in the bed or at a coffee table, and are about the sweet fragility of their situation. In Nuit et jour, the apartment thus becomes a utopian place, a paradise where neither family (the visit by his parents is quickly terminated), nor all those objects that decorate a house (telephone, wardrobe, etc.), nor the normal routines of a house, exist. The exterior universe, noisy and hostile, barely enters the apartment, whose windows Julie shuts as soon as she arrives. Julie and Jack want to stop time and not make a single plan. “In Night and Day (1991), the characters try to trick time,” states Margulies.Footnote52 The bare apartment is a place in pause that is, if I may put it in this way, made for a horizontal experience of the body. What stays outside, the city, with its cars, its commotion, its rhythms, seems to be no more than a gap between two interiors. The almost bodily fusion between the protagonists and their apartment is so literal that the apartment begins to fall to pieces as the love story between Julie and Jack breaks apart and the utopia of a life made of open, innocent desire, free of qualms or jealousy, unravels. At the end, after a phase of tension between them, anxious, they decide to reorganize and start to chip away at the walls and make holes, so that the outside light breaks through brightly as a symbol of lost innocence []. The film ends with a shot of Julie walking alone through the streets of Paris and, as is customary, it is never revealed where she is walking to, whether she will return home or leave for some other place [].

The omnipresence of desire, however unstable, and the contrast between that time that one wants to stop but that passes inexorably, through the image of the long and dense night and the arrival of the light of day, had already been the driving force of another Akerman film, called Toute une nuit (1982). This film is a kind of collage of fragmentary stories, of instants, in which it is seen how the people of Brussels, unable to bear the humid heat of a summer night, become restless: they go out into the street or the garden, they get out of bed and walk around their apartments, opening and closing windows, they smoke, they go from one house to another, from one café to another, they meet, they separate, they look for the cat and play around with it, they despair or they dance, they hug and kiss each other, they go up and down the stairs, or they carry out some palliative ritual. All of this is in reality a constant search for others, to combat the heat and to assuage desire, so that the consistency of the film is that of a kind of symphony or choreography (of embraces, most of the time), to the beat of desire []. In the words of Serge Daney:

The bodies, not being able to cope any longer with agitated desire, fall heavily into the arms of other bodies. They throw themselves at each other, they embrace each other. Once, twice, ten times, as variations on a single theme. That night, when the curtain lifts, it is all instant love in the shadows, […] somnambulist dialogues; throughout the night, the whole world seems to have won in the lottery of desire.

But as far as love is concerned, it stays off-field. A lot of sweat, no little sensuality, but no sex. Akerman films the before and after, except that the after bears the traces of the before. Toute une nuit imperceptibly becomes a documentary on ways of sleeping, rituals, sheets.Footnote53

This is a film about ephemeral time and the vibrations of the body, on small gestures and dances that take place on the thresholds of the city (doorways, windows, passageways, balconies, mezzanines), in which, not by chance, it is usually the women who flee from their houses and throw themselves into the night. Of Akerman’s oeuvre, this is perhaps the film that is the most removed from any big story, and far more so from the traditional linear love story, with a narrative outline of courtship and marriage. Toute une nuit is nothing more than a succession of meaningful moments, climactic instants that are loaded with energy, always palpable in the body more than in the words, which here are more meagre than ever. This is a work made from repetitions, serialities and bodily impulses that have something of that world of dance and performance that Akerman was always so close to. However, beyond the simple song to the breaking up of the story and the fleetingness of affections, what is suggested in this film has its roots in the political imagination of the seventies and above all delves into her own cinematographic work. That is to say, in this film, Akerman again wants to shake the spectator, to make the viewer feel the passing of time, warning that one’s own feeling and experience are both socially constructed and malleable, and that the wall that separates the public from the private is no more than a feeble membrane. Or, as Daney writes: “It is the spectator she wishes to keep from sleeping, suggesting to them that one whole night is a length of time long enough for a body to pass through all states, even the impossible states of desire and the unlikely states of amorous positions”. Akerman transforms everyday time into time of desire. She turns the night on its head, so that the night is not for sleeping, resting and preparing oneself for the day of work that will come with the light of the sun, rather it is for seeking others. Turning time on its head to give it to desire is the same as turning a house around so that it will never again be a factory or a cage but a liberated place of one’s own. Obviously, these deviations are, in the end, a revolt against work.

Coda: the bed, the artist working

However, there is here yet another paradox that Akerman’s cinema provides, because it should not be forgotten that she makes films, she works tirelessly: exactly in contrast to the idea of work and routine. And she does so not only through films that, like Nuit et jour and Toute une nuit, give free rein to desire above anything else, but by confronting the contradiction face to face, with the body itself, in order to try and turn it on its head or at least give an account of it. By this I mean that Akerman made a series of pieces that, along the same lines as Saute ma ville or Je, tu, il, elle, are played by herself, with the auteur in front of and behind the camera, but where—and this is their main value—she is shown in an indolent pose, reclining on the bed watching time pass and in movements that are the opposite of any heroic notion of work or the creative process. I am referring to experiments such as La chambre (1972) and Portrait d’une Paresseuse (1986), two short films in which Akerman appears lying down on her bed, without any willingness to get up, wash and start the day.

In La chambre, a slow circular tracking shot monotonously records the everyday objects in her room, including herself who, from her bed, unmoving, gazes at us, introducing minimal variations in her posture []. In Portrait d’une Paresseuse, a short film that is included in the collective film Seven Women, Seven Sins,Footnote54 an Akerman hidden among sheets confesses that she has no desire at all to get up, even though “to make movies, you’ve got to get up, get dressed … ” []. With a great deal of effort she ends up getting out of bed, but all that she does during the length of the film is to repeat two or three actions obsessively, none of any benefit, such as smoking, taking vitamins and listening to her female companion play the cello in the living room—a companion who is the protagonist of another short film set in an interior devoted to music, Trois strophes sur le nom de Sacher (1989). In these short films, there is a sense of lassitude, a desire to be lying down that clashes with the surrounding reality, with any sociality, as well as any heroic, vertical, masculinized or phallic image of the film director.Footnote55 Indeed, turning the camera around on oneself is to show oneself in the act of working, filming oneself in full productive process. But, here Akerman goes beyond the affirmation of the creative work of women, of their voice. Playing with contradiction and setting out a cinema made of minimal quotidian acts, she claims a right to laziness, to eroticism, to quietude, to the enjoyment of the room itself, to the sensorial pleasure of the small and the bodily and of the freeing-up of time. Thus, her films continue to breathe this atmosphere of liberation of life that was so much a part of ’68, leading to a still relevant reflection on the correspondence between work and desire.

Conclusion

To conclude, I can say that paying attention to elements that could be considered as phenomenological (space, time and body movements) in Chantal Akerman’s films is a useful strategy that throws new light on her filmography. Hers is a cinema that participates in the women’s cause by using tools that go beyond speech and voice to focus on something as simple as the body in the time and spaces of everyday life. This is why interiors are so important in her cinema: because it is in interiors that we spend most of our lives and, as a matter of fact, many women carry out their (paid or unpaid) work. Akerman’s filmmaking moves through all the states and possibilities of the inside, and of the postures of the body and the feminine subjectivity in them. Not only did she fully participate in the condemnation of domesticity and of work so typical of the seventies, but also, in a more complete and interesting sense, she condenses that double movement of leaving and returning to the interior, which is, above all, a movement of rejection and refoundation. The point is that, since hers is a cinema that is interested in desire, it is also a cinema that inevitably accepts the contradictions and ambivalent states to which it leads.

Disclosure statement

I confirm that this article has not been published elsewhere and is not under the consideration of any other scientific journal. In addition to this, I want to point out that I have no conflicts of interest to disclose. This article is an original reading of the films of Chantal Akerman, one of the most important authors in the feminist film scene, past and present. With a novel approach, it offers an interpretation of her main works from the 1970s and 1980s from the point of view of the affective experience of space, that is, according to the desire that this can unleash and/or repress, a central element in her particular way of understanding the social situation of women and the artistic creation associated with it, but one that has been historically neglected in most of the monographs that analyse her cinema.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Irene Valle Corpas

Irene Valle-Corpas has a PhD in Art History from the University of Granada under the supervision of Manuel Borja-Villel (director of MNCARS) and Esperanza Guillén (University of Granada, Spain). She works on several research projects, one of them in the Pompeu Fabra University, where she did a Master’s Degree in Comparative Studies. She has published articles on art historiography, cinema, contemporary art and urban space (that have appeared, among other journals, in Quarterly Review of Film and Video, Boletín de arte …). She has been visiting researcher at EHESS and ENSBA in Paris and has been researcher at the Residencia de Estudiantes in Madrid.

Notes

1. Michelle Perrot, The Bedroom: An Intimate History, (New Haven: Yale University Press, Citation2018), 112, 114–115, 147.

2. Steven Jacobs “Semiotics of the Living Room: Domestic Interiors in Chantal Akerman’s Cinema” in Chantal Akerman : Too Far, Too Close. Amsterdam, The Netherlands ; Antwerp (Belgium: Ludion ; Muhka, Citation2012), 73.

3. Ibid, 76.

4. Bérenice Reynaud, “These Shoes are Made for Walking,” Afterall, n.o 6 (Reynaud Citation2002): 51.

5. In her essay “Women’s Time”, Julia Kristeva established a strong connection between the emergence of the feminist movement after May 1968 and the mistrust of the linear and teleological models of history considered until then. This essay serves as a context for Akerman’s work and is in tune with the manipulation of different temporalities (fluid or plural) that she displays in her films. See Julia Kristeva, “Women’s Time,” Signs 7, nº 1 (Kristeva Citation1981): 13–35.

6. For the urban vein in modern cinema in general see Pierre Sorlin, European Cinemas, European Societies. 1939–1990 (London: Routledge, Sorlin Citation2004). On the importance of bringing cameras to the city ground in the Nouvelle Vague movement see Jean Douchet, Nouvelle Vague (Paris: Fernand Hazan, Sorlin Citation2004). The inclination towards urban everyday life in the cinema of the 1960s—both in Parisian cinema and in that which, in parallel, flourished in New York—has been studied in Juan Antonio Suárez “Styles of occupation: Manhattan in experimental film and video from the 1970s to the present” in Cooke, Lynne, y Douglas Crimp. Mixed Use, Manhattan Photography and Related Practices, 1970s to the Present (New York: MIT Press, Cooke and Crimp Citation2010).

7. On the transition from the street to the interior, or rather on the extension of the political struggle into the private sphere from 1968 onwards, see André Habib, “ La rue est entrée dans la chambre!: Mai 68, la rue et l’intimité dans The Dreamers et Les amants réguliers,” Cinémas. Revue d’études cinématographiques, no 1 (Habib Citation2010): 59–77.

8. On the affective turn and the inclination towards reduced spaces in French cinema immediately after 1968, see Doménec Font, “En la órbita post-Nouvelle Vague. La Cicatriz Interior,” [“In the post-Nouvelle Vague orbit. The Inner Scar”] in En torno a la Nouvelle Vague. Rupturas y horizontes de la moderndiad. (Valencia: Filmoteca de Valencia, Font Citation2003), 370–71. And María Velasco, Les enfants perdus. El cine independiente francés. Pialat, Eustache, Doillon y Garrel (Madrid: Ediciones JC, Velasco Citation2012). On the other hand, an overview of the cinema made by women after 1968 can be found in François Audé, Ciné-modèles, cinéma d’elles: situations de femmes dans le cinéma français, 1956–1979, (Lausanne, Éditions l’Age d’homme, Françoise Citation1981). In addition, Ann Kaplan’s important study on women and cinema points out that the authors of the 1970s she analyses (Marguerite Duras, Yvonne Rainer, Laura Mulvey etc.) address the problem of female subjectivity in indoor spaces, often associated with the roles imposed on women. In her influential essay, she draws parallels between independent films made by women in the USA and those made in Europe—especially in France and Great Britain. This international exchange is very reminiscent of Chantal Akerman’s own work, always halfway between the New York and the European scenes. See Ann Kaplan, Women and Film. Both sides of the camera (New York: Routledge, Kaplan Citation1983), 83–200.

9. Marion Schmid, Chantal Akerman (Manchester: Manchester University Press, Schmid Citation2010), 6.

10. Jenny Chamarette, Phenomenology and the Future of Film: Rethinking Subjectivity beyond French Cinema (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 143.

11. Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time Image (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, Deleuze Citation1997), 195–197.

12. Quoted in Ivone Margulies, Nothing Happens: Chantal Akerman’s Hyperrealist Everyday (Durham: Duke University Press), 42.

13. It was precisely 1975 that was declared, by the UN, International Women’s Year. Due to this, activities were carried out around the world but also protests against the deactivation of feminist struggles that the governments of wealthy countries, using this declaration as an excuse, tried to bring about. It is interesting to observe how, parallel to the whole theatre of official acts, feminist filmmakers chose either to document the protests of activist women, or to make films of this true quotidian life. Regarding this question see the catalogue: Nicole Fernández, Nataša Petrešin-Bachelez, Giovanna Zapperi, et al., Defiant Muses. Delphine Seyrig and Feminist Video Collectives in France in the 1970s and 1980s (Madrid: MNCARS, Petrešin-Bachelez et al. Citation2019).

14. Cybelle McFadden, Gendered Frames, Embodied Cameras: Varda, Akerman, Cabrera, Calle, and Maiwenn (Nueva Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2014), 88.

15. Chantal Akerman, “Chantal Akerman on Jeanne Dielman,” Camera Obscura 2 (Autumn 1977): 119.

16. Stated here: “Chantal Akerman on Jeanne Dielman” (Criterion Collection, Akerman Citation2009), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v = 8pSNOEYSIlg. Minute 0:46.

17. Chantal Akerman, “In Her Own Time: Interview with Miriam Rosen,” in The Cinematic (Whitechapel: Documents of Contemporary Art) (London: Whitechapel, Akerman Citation2007), 197.

18. I have taken this idea from Margulies, op. cit., 84.

19. Paul Valéry, Oeuvres II (Paris: Gallimard, Valery Citation1960), 379.

20. Chantal Akerman, Chantal Akerman. Autoportrait en cinéaste (Paris: Cahiers du cinéma, Akerman Citation2004), 30–31& 39. My translation.

21. Deleuze, op. cit., 196.

22. Youssef Ishaghpour, Cinéma contemporain de ce côté du miroir (Paris: Éditions de la Différence, Ishaghpour Citation1986), 261.

23. Marguerite Duras, Écrire (Paris: Gallimard, Duras and Gauthier Citation1974), 13.

24. Marguerite Duras and Xavière Gauthier, Les Parleuses (Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, Duras and Gauthier Citation1974), 49 & 68.

25. Spoken by Akerman, recorded by Janet Bergstrom, “Chantal Akerman y el espíritu de los años setenta” [“Chantal Akerman and the Spirit of the Seventies”], Lectora, nº 7 (Bergstrom Citation2001): 39 [My translation]. And she was not the only one. Years before, Simone de Beauvoir had written: “This escape, this sadomasochism in which woman persists against both objects and self, is often precisely sexual” (The Second Sex, New York: Vintage, Citation2011, 544).

26. Margulies, op. cit., 76 & 89.

27. Taken from Marion Schmid, op. cit., 45–46.

28. Idea taken from Jean-François Chevrier, Agir, Contempler (Paris: Éditions ArtLys, Chevrier Citation2016), 134.

29. Quotation taken from Akerman, Chantal Akerman. Autoportrait en cinéaste,178. My translation.

30. Taken from Bergstrom, op. cit., 35.

31. See the already cited book by Margulies and this 1991 interview for French radio: “J’ai rencontré le cinéma en voyant Pierrot le fou”: https://www.franceculture.fr/emissions/les-nuits-de-france-culture/chantal-akerman-j-ai-rencontre-le-cinema-en-voyant-pierrot-le