ABSTRACT

Central to art was once its relationship to the imaginative interior of the artist. The legacy of romanticism and the sublime has been systematically eroded throughout the 20th and 21st centuries. Although for some not entirely lost. Contemporary discourses around the posthuman have played their part in the erasure of the artist, through the breakdown of the centrality of our bodily self in the world, and correspondingly, our imaginative interior as previously conceived has been jettisoned. Through the rise of the anthropocene, attention is now paid to the more or other-than-human, and even for those who take the person as part of this schema, the body is no longer closed, its interior bracketed off from the world, but part of a wider nexus, where fundamentally for the posthuman, the body-mind of the artist is not necessarily the originating source for creativity. This paper seeks to consider the material embodiments of these developments through exploring the working practice of artist Katie Paterson. Multidisciplinary and cross-medium, her work is concerned with immensity and particularity; her material is the stuff of the world, through which she tells the story of nature’s elusive phenomena. The artist is quelled and transformed in Paterson’s work through a re-articulation of the structures and processes normally hidden from us. In this way the register of the artist shifts and the subjective self is dispersed and reconstructed through alternative frames of reference, most notably geological time and the space of the cosmos. Heir to the romantic sublime, her work offers a reappraisal of the place of artistic subjectivity in the era of the posthuman. In so doing her work reveals the potential for a new posthuman sublime.

Introduction

The interrelationship between the body and the phenomenal world is premised on the relation of self to world. Further to this is the interior of the body as the site of subjectivity. As Lajer-Burcharth and Söntgen (Citation2015) rightly note, the assumption of subjectivity as an interior space is longstanding with a varied genealogy. Central to its development in the twentieth century is Freud’s conceptualization of the psyche (1930), which has held sway over its theorization. For Freud, the psyche can be conceived of in spatial terms as an “internal topography” (Lajer-Burcharth and Söntgen Citation2015, 4) distinct but depended upon the body and that which is exterior from it. Correspondingly, subjectivity is spatialised and belongs to this internal realm. But as the home of subjectivity, the body is co-extensively defined as autonomous and distinct for each individual but interdependent on other selves. With the rise of postmodernism, this model has been called into question (see Callus and Herbrechter Citation2012). Transformations in the reach of technology have supported or perhaps given rise to the consequential revision of the self and its delimitation (see Scharff and Dusek Citation2003). The arts are a fertile ground from which to view these developments. Whilst once the internal thinking mind of the artist underpinned how we approached art through the legacy of romanticism and the sublime, this approach has been throughout the 20th and 21st centuries systematically eroded. Although for some not entirely lost. What is of interest here is how contemporary discourses around the concept of the human have fed into the reappraisal of the role of the artist for those whose work is heir to this romantic lineage, in which the presence of the artist has historically been indelibly inscribed upon the work. Specifically, I want to call attention to the displacement of the artist as the site of meaning and the mechanisms through which this occurs. For some, authorial intention or agency has been revoked and with its artistic subjectivity as previously understood through the heritage of the romantic sublime has been cast asunder. This has been felt most keenly in our relationship to “nature” and the art that reflects it. Where once nature was a mirror upon which the self could be explored, chiefly embodied in the concept of the sublime, nature is now contingent. Best expressed in trans-disciplinary discourses of the posthuman (see Wolfe Citation2010; Hayles Citation1999; Haraway Citation1985; Braidotti Citation2013; Ferrando Citation2016; McCornmack Citation2016), we have now begun to break down the centrality of a unified bodily self in the world (Latour Citation2005), and correspondingly, our imaginative interior as previously conceived has been jettisoned and fragmented. This rupture has been engineered through the breakdown of the normative distinction between the human and non-human, and correspondingly or causally that between nature and culture as traditionally designated.

Its breakdown is, however, not its erasure. The posthuman as a critical discourse across the humanities can be seen in part as a response to the anthropocene, that is, it is a re-imagination of the human, in light of what the anthropocene proposes.Footnote1 Confirmed in 2016 as a definable geological epoch, the age of the anthropocene is characterized as one in which humanity has a defining effect on the planet. As Vincent Normand notes, “the anthropocenic stage organizes a collision of humans with the earth” (Citation2015, 65). In the age of the anthropocene, we are witnessing the ever-increasing reach of the human. This in turn has redefined what more or other-than-human is in an age where nothing is out of bounds from us. But as theoretician Rosi Braidotti (Citation2013) points out, the anthropocene does not designate one singular perspective. Indeed, the anthropocene is a “condition”, which has acted as the foundational catalyst for a number of schools of thought, including the posthuman (McCornmack Citation2016). It is a symptom that for some can only be addressed through a move towards a more full post-anthropocentrism (Ferrando Citation2016). The posthuman, then, as a neologism has ushered in a new vocabulary to voice and correct the shifts that we are witnessing across the globe. But as Cary Wolfe notes in the opening to “What is Posthumanism” (Wolfe Citation2010) there is not a broad consensus as to its definition. Whilst it can be seen as oppositional to humanism, with CitationFoucault’s ([1966] 2001) prophetic image of humanity’s changeability as certain as the waning of drawings on the sand at the edge of the sea acting as something of its mantra (see Wolfe Citation2010), how this opposition is realized or accounted for is multiple.

Residing in cultural posthumanism in particular (see Badmington Citation2000) is the invitation to re-engage with the things of the world through decentering the place of the human in our analysis and in so doing opening up a space for alternative materialities and affects. For New Materialism, which has found particular resonance within the arts, and which pays attention to the more or other-than-human (See Barad Citation2007; Bennett Citation2010; Dolphijn and Van Der Tuin Citation2012), posthumanism is the starting point from which their analysis unfolds. The body within this schemata is no longer closed (if ever it was), its interior bracketed off from the world and the means of mediating between the real and the imaginary, but part of a wider nexus, where the body-mind is not necessarily the originating source for creativity. The posthuman turn is a collection of ideas that attempt to address how the delimitation of people is now fundamentally, differently structured. The posthuman turn is representative of a line of thinking that has been arguably forged though crisis, best epitomized in the anthropocene it can be seen as a call to arms. In theorist Donna Haraway’s book, “Staying with the Trouble”, she uses her platform to incite a need to remain active and to push forward—often against the idea that the anthropocene can be understood in the singular. In her suggestion that “staying with the trouble requires making oddkin; that is, we require each other in unexpected collaborations and combinations” (Citation2017, 4), we see the value that art may play here.

This paper seeks to consider the material embodiments of these developments through exploring the working practice of artist Katie Paterson. Her work is not a philosophical treaty on the posthuman, but a means of reworking how art can function. It acts as an illustration of the conundrum that the posthuman, and the posthuman sublime in particular, poses and is one example of the visualization of these discourses. It is to her work that I turn to next.Footnote2

Katie Paterson

Multidisciplinary and cross-medium, Scottish-born artist Katie Paterson’s work is concerned with immensity and particularity. It alludes to a scale beyond the human, that speaks to the vastness of the planet or the cosmos. But this vastness is revealed through the smallest of sand grains or a singular eclipse of the moon. The particular becomes a lens through which we witness the immeasurable. To do so her material is the stuff of the world, often millions of years old, through which she tells the story of nature’s elusive phenomena. Not limited to the boundaries of the earth however, her work reveals her fascination with the universe and in her telling nature and the cosmos are brought into a more intimate dialogue with the work’s spectator. Resolutely conceptual, Paterson’s objects, installations, photographs and sound work are all inspired by the fields of ecology, cosmology and geology. The abstracted and unknown knowledge of science that takes these arenas as their subject is made manifest. The range of her output and its links to both art historical movements as well as further afield in disciplines such as geology, cosmology and biology means that her work is subject to a host of descriptive terms such as; intermedia, new media, conceptualism, neo-romanticism, with each honing in on a different aspect of her work. It is the crossovers between each that is generative and allows the work to be rich in depth and association.

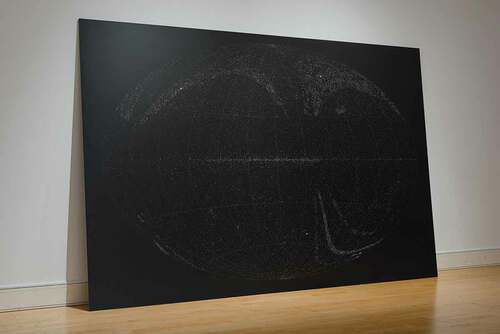

This approach is best exemplified in her recurring motif of stars, such as in “All the Dead Stars” (2009) (See ), in which she produced a map that charts all 27,000 dead stars that have been observed and documented. Following this, in 2011, she started her “The Dying Stars Letters” series, which is ongoing and sees the artist writing a letter to inform a person about the recent death of a star. This approach is markedly distinct from more normative representations of the sky and stars, such as can be seen in the work of Latvian-American artist Vija Celims. Over her career Celims has produced a number of portfolios of work based on the stars and cosmology; from the 1990s the artist completed a suite of charcoal drawings entitled “Night Sky” which itself built on early bodies of drawings from the 1960s and 1970s. All of which were drawings made from images of the night sky gleamed from newspapers, photographs, magazines and books (see Relyea, Gober, and Fer Citation2004). These works were not directly observed natural phenomena, rather her interest was in how representations of stars function. Again this can be seen in a more recent mezzotint print from 2010 entitled “Falling Stars” which captures the view from a telescope of a particular moment of observation of the night sky. But as “The Dying Stars Letters” reveals, Paterson’s approach to this subject is not purely representational. She does not set out to illustrate the findings of astronomy but instead seeks to transform our relationship with it through an intervention that is both methodological and philosophical. In writing a letter to address the death of a star, she is proffering an alternative view from that normally given in representations of stars as constellations, as patterned images. Here she evokes time in this presentation, as well as the fragility and finite nature of the cosmos. Stars become in this approach closer to the fragility of human and non-human life on earth.

Figure 1. Katie Paterson, All the Dead Stars, 2009Photo © Mead Gallery Installation view, Mead Gallery, Warwick Arts Centre, 2013

Paterson’s ability to find a commonality between the cosmos and everyday life is played out in her use of materials. For instance, in her piece “Streetlight Storm” (2008), set on a pier in Kent, UK, the artist strung up a series of light bulbs on the pier that were adjusted to pulse in tandem with lighting strikes taking place across the world. A similar technique is employed eight years later in “Ara” (2016). Suspended across a gallery space, each light bulb’s shine corresponds to the luminosity of a star. In both pieces, as Tufnell notes, “impossible vast cosmic events are rendered at a domestic scale” (Citation2014). In all of these works a mediating technology, such as an antenna housed on the pier in “Streetlight Storm”, expands the literal range of things we live alongside, into a new arena through which they tell a new story or narrative. This habit of combining the quotidian with the cosmos is commonplace across her art; from light bulbs to LP players and candles, the seemingly simple materials she uses, mostly manufactured or synthetic, belies a complex engagement with matter and artefacts. These items are co-opted into playing a new role, recast into an engagement with something more profound than they were originally engineered for. Her utilization of these materials and the pedestrian technology that they symbolize does in many of her work stand, potentially, in stark opposition to the technology used to realize this data. Often the method of display she uses is deliberately simple, if not outmoded. For instance, “History of Darkness” (2010) consists of a slide archive of images of darkness taken over a twelve-year period, the chosen form of presentation, the slide, does not mirror the cutting edge, technological innovation that is needed for the production of the images. These simple everyday prosaic technologies are juxtaposed against the highly engineered, esoteric technology that her presentation implicitly reveals. The apparatus and findings of astronomers and geologists which forms the subject of Paterson’s work is then a means of aligning everyday technology with feats of engineering usually the preserve of the few. As Pryle Behrman notes, Paterson uses technology to unite the “commonplace and the cosmic” (Citation2010, 25).

As a visual artist, this transformation is orchestrated through a visual presentation of her subject and whilst highly conceptual in content, her work provides the viewer with a way of witnessing something more normatively out of reach; a means of representing it and in so doing transforms our relationship not only with the phenomena explored but the instruments used to articulate it. Correspondingly, the register of cosmological time and space coalesces with the human. But the potential indivisibility between the human and the cosmos that Paterson’s work points towards is not realized through the display of the artist’s personal subjective experience of the phenomena. Indeed, it commonly functions to decentre the artist from the artwork. This becomes most apparent when we see the occasional artwork that does not function in this way. For instance, as writer Lars Bang Larsen argues “Candle (from Earth into a Black Hole)” (2015) (See ) is the most subjective of Paterson’s work (Citation2016). For this piece a candle is infused with a series of scents which are designed to evoke the planets and stars in the cosmos, with each celestial body aligned with a hand-picked smell, chosen by the artist to conjure up her own ideas about how each should be best represented. The moon, for instance, is symbolised by the smell of burnt almond cookies and Jupiter by ammonia. As the candle burns, each smell is released in turn and a journey across space between the Earth and a black hole is olfactorily portrayed. But what is critical here, as Larsen notes, is that the scents used by the artist are entirely arbitrary and in fact “lay bare her own cultural programming” (Citation2016, 225). There is no scientific rationale at play here that underscores the association of one scent over another and it is in fact a window onto the artist’s own preferences and tastes. This more obvious reference to Paterson’s own personal perceptions is pared back and almost extinguished across the rest of her oeuvre, where it could be suggested that the work functions to rid the art piece of any marker of the artist herself.

Scientific methodologies

The displacement of the artist in Paterson’s work is operationalized through her recourse to the methods and procedures of science. This, however, is entirely collaborative and Paterson’s work with those such as biologists, scientists, and geologists forms the backbone of her practice. In this respect, her work typifies the now populist approach by artists to draw not only on the knowledge of the sciences but also their methodologies and language to realize a work of art, as Larsen notes she “works like them” (Citation2016:224 italics in original). This mirroring of sciences’ specifications, its regulations and guidelines, provides a means of structuring the work, avoiding the fanciful and maintaining a validity in what she expresses. Whilst this may appear to be a straightforward process of translation, in which the unreachable, abstract knowledge contained within the sciences is made into material form, in order to show the world’s sublimity, it is under the stark minimalist presentation she employs a subtle dialogue with science rather than is elucidation. Again, it is through the juxtaposition of the quotidian and the highly engineered that this is operationalized. Larsen suggests this is potentially a confrontation between science and its “platforms and procedures” and the domestic, which results for Larsen in the admission of a “certain fragility or message-ability of science” (Citation2016, 222).

Science’s communicative efficacy is not assured in her work and Paterson presents the fault lines of our relationship to science. Her work becomes a serigraph to wider societal, including its technological developments and, importantly the issues our advancing progress raises. The role of observation is crucial for Paterson in teasing apart these ideas. She mirrors scientific procedures through adopting their strategies of observation and processes of looking, but in the presentation and display of her work she undermines the very methods used to produce them through failing to contextualize her findings. That is, her work does not reinforce science’s authority. As Mary Jane Jacob (Citation2016) notes, Paterson’s work shares with science a commitment to observation. This can be seen in her 2016 piece “Totality” (see ). Decorating the outside of a mirror ball, which when exhibited is hung from the gallery ceiling, the artist has covered the surface of the ball with 10,000 images of all known solar eclipses. Ranging from early drawings to photographs from the 19th century, the ball reveals on the gallery walls the movement of the moon and sun through a solar eclipse from crescent to full. This collage of solar eclipses forms one image through displaying multiple, individual representations. In this, she has foregrounded the observations of science but her presentation stops short of an interpretative exposition of her findings, or indeed, revealing those of the experts in the field. There are no analytical interpretations to accompany the visuals she provides and instead she presents the barebones of what is observed without any contextual frame of reference. In this choice she deviates from imitating science’s approach and the corresponding authority that it imbues upon its subject. The apparatus that provides science with its legitimacy is absent and we are left with ideas and data that are denuded of their traditional power. The artist then is not the handmaiden of either the established tenets of science or technology. Instead, her work is in correspondence with scientific endeavor. But this correspondence is one that is mediated through particular art historical concepts and categories, namely that of the romantic sublime and conceptualism. It is this prism between the heritage of romanticism and the sublime and the technological innovation within her work we find a rumination on the self as the author of the work, and leading on from that, to the notion of selfhood embedded within these new paradigms. This link has been further reinforced in recent years through her 2019 exhibition at Turner Contemporary in Margate, in which the artist is shown alongside the great British romantic visionary JMW Turner. Here we see the centrality of romanticism for Paterson: it anchors the artist’s work whilst simultaneously allowing her to move beyond it and suggest something new.

The romantic sublime and conceptualism

At its height, romanticism, circa 1780–1830, was the prevailing artistic and literary genre across Western Europe.Footnote3 Its emphasis on heightened emotion, through the prism of the psychological and our relationship to the natural world, was formed in opposition to the rise of modernity seen in the industrial revolution. As a backlash to the dominance of neoclassicism and its measured restrained aesthetic, romanticism’s antecedents were found in the myths and symbolism of the medieval world. From the visionary, apocalyptic rendering of William Blake to the sublimity of J.W.M Turner, romanticism stressed a reverence for natural landscapes alongside advocating unbridled imaginative expressions of originality that ensured the artwork became an index of the artist’s subjectivity (see Larmore Citation1996; Vaughan Citation1994). The personal expression of the artist was foregrounded and with it the seeds for notions of artistic genius, which found greatest notoriety in the early years of the 20th century, were sowed.Footnote4 In its stress on the primacy of the individual, it was paired with the sublime, for as Lyotard suggests “the word is from a romantic vocabulary” (Citation1991, 126).

Like romanticism, which Baudelaire (cited in Vaughan Citation1994) described as not belonging to an object or theme but a “feeling”, the sublime was not restricted to one style or genre but was instead suggestive of qualities or sensibilities within the work of art. This sensibility accords with the word’s etymological root: for sublime derives from the Latin “sublimis” meaning elevated or lofty. The sublime as a subject reached its zenith in the 18th century, and spanned an array of disciplines, from philosophy to the sciences. It took particular hold within the arts and within aesthetics and literary studies (see Courtine Citation1993; Battersby Citation2007), where various iterations of the concept were proffered. Its relevance and continual reappraisal has persisted apace since its inception, moving on from classic conceptions of the Kantian sublime in the 18th century towards contemporary technological and eco-sublime in recent decades (see Bell Citation2013). The persistent reinvention of the term has for some meant it is now too diffuse to be meaningful (Elkins Citation2011). However, taken collectively, these iterations of the sublime map the shifts in conceptions of the self through the prism of the natural world. This can be witnessed in one of the earliest treatises on the subject, Edmund Burke’s 1757 “A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful”, where the author abandons nature in favour of the experience of it, and in so doing shifts the analysis towards the psychological.

Similarly, Kant’s theorization of the sublime, which followed in the wake of Burke, was principally concerned with mapping the egotistical sublime, which reinforced the contention that the sublime was not descriptive of the appearance of concrete phenomena, but instead a subjective response which happens internally within the mind of the beholder. For Kant, this reaction is predicated on having a primary first-hand experience in nature. Through which the individual undergoes feelings of terror and uncertainty in the face of a direct threat. But to achieve a sense of the sublime the danger is witnessed but not actual, and through this distance a pleasure is realized. For Kant, in the recognition that we have not succumb to the risk posed by the natural world there is an affirmation of our sovereignty. Thus, the sublime both evokes the limits of our comprehension and also our ability to transcend it. Central to this theorization of the sublime is the role of nature in creating this experience. In respect to art, this interpretation also ensures that works of art in themselves cannot be sublime, and are derivative only. Philosopher Emily Brady (Citation2013) adheres to this line of thinking, and advocates that art cannot fully emulate the experience of being in nature. For Brady, Kantian sublimity is the most accredited and far ranging treaty on the sublime that still holds sway today. But within her writing Brady proposes Kant’s interpretation of the sublime can be understood as non-anthropocentric, based as it is on a relationship between us and nature, in which nature is autonomous. As she says: “the core meaning of the [Kantian] sublime, as tied mainly to nature, presents a form of aesthetic experience which engenders a distinctive aesthetic-moral relationship between humans and the natural environment” (Citation2013, 3). This accords with more recent thinking on the agency of the non-human, as seen across theories of the anthropocene and the posthuman more broadly. But for the work of art as a second-order sublime only, the register of the human is still ever-present. Central to any discussion on sublimity in works of art then is the contention that the sublime is a first-hand experience only. Whilst Brady’s position has been critiqued, most recently by Nicola A. Hall (Citation2020), who advocates more ambitiously that art can potentially be sublime through situating it as an imaginative faculty, it is still the argument for this paper that the sublime in art is usually only indirectly given. The work of art is most commonly an index of the artist’s experience conveyed in pictorial form across the canvas. In these evocations of the sublime, the centrality of the artist is reinforced. For however much the artist may experience a moment of transcendence in nature which forms the inspiration of their work, once sublimity becomes a representation on canvas then it speaks back to the point of origin of its expression: the artist themself. This is where we see a divergence with the work of Paterson, which arguably bypasses the artist as the origin for the work. This is not to advocate that Paterson’s artworks offer a first-hand experience of the sublime but to more tentatively suggest that her work is symbolic of a shift in the how the natural world is engaged with in contemporary art. A shift in which the artist is no longer the thread that connects the viewer to nature’s phenomena.

To clarify this argument we can turn to the neo-romantic work of German artist Mariele Neudecker. Neudecker articulates her work through the prism of the sublime in a myriad of ways. Early in her career she began to reference the romantic sublime through casting models of landscapes found in quintessential romantic paintings, such as those by Caspar David Fredrich. These castings were subsequently shown in glass vitrines, filled with water as replacement air. The vastness of the landscape that is implied in the paintings is condensed down, contained in sculptural form. Neudecker’s iteration of the sublime is even more removed from the natural sublime that was its original source, but this distance is purposeful. In Neudecker’s work there is a concern with the visualisation of the sublime. Paterson and Nuedecker exhibited together in 2018 in an exhibition entitled “Scaling the Sublime: Art at the Limits of landscape”, curated by Nicolas Alfrey, Rebecca Partridge and Neil Walker, at the Djanogly Gallery, Nottingham. In the exhibition text for the show Neudecker’s work is described by Alfrey and Partridge as explicitly concerned with the socio-cultural history of the sublime: “in her work she lays out some of the processes, perceptions, apparatus, and conventions by means of which landscape is constructed” (Citation2018, 38). In comparison, there is no such questioning in the work of Paterson, which is more intent of revelation. However, in her opening essay for the exhibition catalogue Partridge designates all the work shown as embodying a “critical subjectivity”. As she says:

‘It is a space built on objectivity; on looking, calculating and mapping, but which leads us to incalculable perceptual experiences, to emotional responses such as wonder or self-transcendence’ (Citation2018, 22).

But for Paterson’s work the applicability of this designation needs to be questioned. Arguably in the case of her work it is more accurately an emotional response of the audience to the work that Partridge is referring to, not the artist’s subjectivity per se. Whilst a critical subjectivity is certainly apparent in the work of Neudecker, through her presentation of the social-cultural underpinnings of the sublime, it is misplaced in analysing Paterson and would be better understood as a potential move to its negation.

As the exhibition “Scaling the Sublime” attests, the sublime is still a topic that garners interest in contemporary practice.Footnote5 In recent years, this interest has gathered pace but as is evident in the work of Paterson, the contemporary sublime now is filtered through the subsequent developments in contemporary art that have occurred during the twentieth and twenty-first century. For historically the classic sublime in art as a subject was only taken up for a relatively short time. Its affiliation with natural motifs led to it suffering the same fate as landscape art more generally, which saw a downturn in popularity at the beginning of the twentieth century. From which time the personal expression of the artist was no longer filtered through a response to landscape and environment. However, as Simon Morley notes, following World War II, we see a return to the search for transcendence and awe in the abstract expressionists. Then, again in the 1980s, the sublime was picked up by such artists as James Turrell (Morley Citation2010). In more recent decades themes pertaining to ecology and the environment through the prism of the anthropocene and climate change have once again seen the sublime take centre stage, albeit through a more diffuse lens.

Paterson’s artwork is heir to this trajectory and in her work we see the confluence of the romantic sublime with conceptualism, in particular. Instigated in the 1970s, conceptualism advocated that art’s material reality was of secondary importance to the ideas that the artwork conveyed. With the theorisation of an artwork taking precedence, it was for many an opportunity to explore how far the process of artmaking could be discarded entirely. This approach was adopted as a way of countering the then prevailing authority of modernist formalism. For curator Andrew Wilson (Citation2016) this was achieved by conceptualism through a rejection of visuality, medium specificity and materiality. For each of these conceptualism would proffer an alternative; a focus on language, everyday objects and events. As Wilson suggests, the effect was the production of art that was “not defined by its own conditions—its self referentiality—but which drew its material and its content from the world in which it existed and acted within” (Citation2016, 53). With the process of making taking centre stage in presentations of work, to favour events rather than finished, closed objects, there was a corresponding reappraisal of how time and space were conceived and represented. As Wilson notes, this shift from object to performance also ushered in a change for the art viewer who was moved from passive receptor to active participant. This change would find greatest expression in the decades that followed in participatory art of the 1980s and site-specificity of the 1990s in which art moved out of the studio and gallery space and into the street and home. But in returning to conceptualism, we can note that despite its claims to the contrary it did have a specific aesthetic that privileges a documentary style of presentation, which included the use of photographs as well as presenting as art the material collected during research and exploration of chosen topics. This aspect of Paterson’s work has the effect of further distancing the artist herself from the work and is particularly effective when Paterson engages with the subject of the cosmos. Here a conceptualist aesthetic is at play and used in part to reinforce the work’s collaborative association with science and science’s subjects.

The cosmological

As a subject, the cosmos offers Paterson an opportunity to engage simultaneously with the history of romanticism, the sublime and science. For early romantic painters such as William Blake the cosmos was an extension of the sublime landscape, terrifying and awe-inspiring but ultimately at the behest of the human. Scientific enquiry has shifted this position and Paterson’s work reveals these developments whilst also reminding us of its lineage. Space is now part of our landscape in a way that is distinct from its previous conceptualisations. It has become part of our environment, subject to the same principles as land and sea on Earth. Through scientific methods we can map, survey, enumerate and account for it. Through this the universe is no longer entirely alien to us and has become instead, as O’Reilly notes “a multiple of interrelated points with particular properties that precipitate and participate in observable events” (Citation2016). As writer Lars Bang Larsen (Citation2016) notes, there has been a shift in how the cosmos is regarded through the development of technologies that enable us to reach and see further. The safety of the historic sublime was premised on a largely unreachable distance, a distance that has now been ruptured and correspondingly, our supremacy has been called into doubt: “the cosmos is no longer at a safe and antithetical distance to us—no longer a wilderness to which astronomers turn their telescopes—it is now a domain that is legislated and claimed” (Citation2016, 222). The cosmos has shifted from a place removed from us to one that is potentially governed over, and the certainty of the historical sublime that assumed our sovereignty over what was largely an imaginary space is now a relationship in actuality. This has meant that it is now well suited to the documentary approach so keenly used by Paterson. But as Morley (Citation2010) points out, our classificatory devices are arguably attempts at comprehending the cosmos only. For it is an example of a reality too complex to fully understand, the evidence of which can only be discerned through metrics. Within this new reality “the human subject disappears” (Larsen Citation2016, 221).

Writing on the role of the cosmos in art, curator Didier Ottinger suggests that art has gone through three distinct phases in its engagement with the cosmos: the Renaissance, the age of romanticism and modern times (Citation1999). The first is epitomized by artists such as Leonardo da Vinci and the indivisibility of artist and scholar. The second is defined by the irreconcilability between intuition and objectivity. The third most recent phase is characterized by Ottinger as premised on the “irony generated by a scientism reduced to ‘technologism’, to the cult of the machine” (Citation1999, 282).Footnote6 Whilst it may seem at firsthand that Paterson’s work speaks directly to the final phase in Ottinger’s classification, this would deny the persistent and enduring role that romanticism plays in her work. For Skye Sherwin, Paterson’s work follows directly in the wake of such Romantic painter’s as Caspar David Friedrich. But for Sherwin this is not, then, perhaps in contradistinction to Ottinger’s proposition, oppositional to Paterson’s use of technology. Indeed for Sherwin, her utilisation of contemporary technology does not rupture this lineage but in fact supports it. In this, we can see a confluence of Ottinger’s second and third category of approaches to cosmology. We can see this played out in her 2007 piece, “Earth-Moon-Earth (Moonlight Sonata Reflected from the Surface of the Moon)” (see ). For this piece, Paterson took Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata and converted into Morse code before sending it as a radio signal to the moon, from where it bounced back to Earth. In the process of transmission, the surface of the moon interfered with the score and only sent back a partial recording. In the subsequent exhibition, a self-playing, pre-programmed Disklavier Grand piano plays the new score, translating the indentations and crafters of the moon as breaks and gaps in the music. In his analysis of this piece, art historian Nicolas Alfrey reflects on Paterson’s choice of music. As the epitome of romantic music, the Moonlight Sonata is an icon to this particular sensibility that has arguably lost its ability to invoke “authentic feeling” (Citation2009, 8), and in making this choice, Paterson is not only engaging with the music but the wider narrative in which it is embodied. For Alfrey, sending Beethoven’s piece to the moon may at first glance suggest a cynicism in Paterson’s regard for the romantic sublime, highlighting the disconnection between the representations of a thing, in this case the musical score, and its actuality. As Alfrey also notes, the playing back of the musical score through a pre-programmed piano flies in the face of the stress of heighten individual expression that underlies romanticism.

Figure 4. Katie Paterson, Earth–Moon–Earth (Moonlight Sonata Reflected from the Surface of the Moon), 2007 Installation view, the Slade School of Fine Art, 2007 Photo © Kathryn Faulkner, 2007

Within Paterson’s piece the artwork is devoid of any human intentionality in its final form. Initiated by the artist as an idea, its realization is left to the vagaries of satellite signals and a moment in which it touches the surface of the moon. The appropriation of this sophisticated technology is not at the behest of the idea itself, and Paterson does not use it as a platform to champion our technological achievements. This is not then the celebration of an unfaltering advancement of science. Alfrey offers this caveat: “Paterson is an artist who is genuinely engaged with scientific ideas, but she is wary of making any easy connections between, say, the traditions of the sublime in western art and hitherto unimaginable new domains revealed in fields such as communications technology or space research” (Citation2009, 8). But this is not to deny that Paterson is not herself interested in the possibilities offered by these art historical traditions. “Earth-Moon-Earth” has been exhibited in a number of locations, and with each the association between the work and its possible antecedents is heighten and made more complex, as its recent inclusion in her 2019 exhibition at Turner Contemporary attests to. Prior to this in 2008 the piece was presented at the Modern Art Gallery in Oxford, UK. Here the artist was shown alongside the sublime landscapes of Anselm Adams. A secondary piece entitled “Earth-Moon-Earth (4ʹ33”)” was produced in Japan in 2007 during which time the artist sent a new signal to the moon. Its title suggests its association with the composer John Cage, and as Alfrey notes, the movement from Beethoven to Cage is telling. For him a represents a shift from “romanticism to modernism and from a found musical object to an avant-garde work structured by an interval of time but entirely open to chance” (Citation2009, 15). It is clear from each of these iterations that Paterson’s practice is premised on offering us an altered, transformative version of the sublime, which I would argue is best allied with the notion of the posthuman sublime. It is to that I now turn.

The posthuman technological sublime

Early theorization of the posthuman sublime linked it to the rise of technology (Lyotard Citation1982; Jameson Citation1991). Cultural theorist Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe in his text “Beauty and the Contemporary Sublime” (Citation1999), characterized it as the “posthuman technological sublime”. For him the role of technology is definitive in the modern manifestation of the sublime. Technology has absorbed nature and unlike its predecessor it is potentially without end: “technology has subsumed the idea of the sublime because it, whether to a greater extent or an equal extent than nature, is terrifying in the limitless unknowability of its potential” (Citation1999, 128). Gilbert-Rolfe’s interpretation of the new sublime comes in the wake of the work of David Nye, and his book “American Technological Sublime” (1994). Nye ties this new iteration of the sublime to the rise of industrialisation in the US, which produced awe-inspiring engineering feats that ensured that technology replaced nature as a site of wonder for the spectator. Nye develops a series of categorisations of the technological sublime that speak specifically to the American context he is working within, culminating in the sublime of the consumer. In his analysis the products of our technological advancements replace nature as the foci for the viewer’s gaze. This line of thinking retains the more classic understanding of the sublime which sees a phenomena, be it nature or technology, as its site of origin; now artificial landscapes emanate sublimity.

Gilbert-Rolfe’s interpretation of the new sublime aligns with Nye’s focus on technology, but incorporates the posthuman to stress technology’s distance from the human. Our relationship to technology in the posthuman sublime is fractured with technology achieving a degree of autonomy from us to the extent that we are redundant. Gilbert-Rolfe also posits that the sublime can only now in fact be found or expressed by technology not nature, due to the limitlessness of the former over the latter. Critically for Gilbert-Rolfe, this means that there is no “single determining form” (Citation1999, 55) from which the posthuman sublime issues forth. What is central to this manifestation of the sublime is the platform it effectively gives to the non-human: it is a movement that allows for the realization of the voice of multiple others that are no longer relationally constituted by us.

This is where we can see an alignment with Paterson’s work. The posthuman sublime at work in Paterson’s art is a pincher movement through the coming together of the new sublime, which takes as its subject variegated landscapes and environments beyond human control, and the posthuman which proposes the decentralization of the human more broadly. This sublime enables the rejection of artistic subjectivity as the mediating framework for the work. The most consistent means through which this is actualized in Paterson’s work is through the harnessing of technology. However, technology is not a replacement for nature and in this respect it does not align with Nye’s interpretation of the technological sublime. Instead, technology is instrumental in releasing her art from its reliance on the intention of the artist for the final form of the work. This opens up a space in which other voices can be articulated. Technology is not then the intentional agent in this process, as Paterson’s work demonstrates, but it enables the subject of the work to (potentially) bring forth its own. For instance, in 2007–2008, Paterson connected a live phone line to an Icelandic glacier via an underwater microphone. The piece entitled, “Vatnajökull (the sound of)”, allowed participants to call a number and listen to the sounds emitting from inside the melting glacier itself. This explicit message on climate change situates the work firmly within discourses on the anthropocene, and chimes with Davis and Turpin’s definition of the anthropocene as being a “sensorial phenomenon: experience of living in an increasingly diminished and toxic world” (Citation2015, 3). But this experience belongs to the audience as viewers of the artwork and not the artist who engineered its telling.

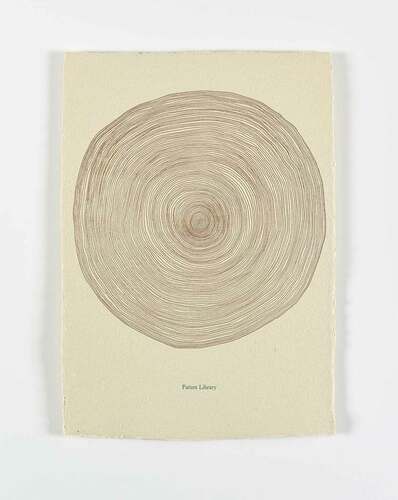

We can see this disavowal or decentring of the artist realised even further in Paterson’s “Future Library” (2015–2115) (See ). Highly collaborative and ambitious in scale, “Future Library” will only be completed in 2115 and will outlive the artist herself. For it Paterson has to date planted 1000 trees in a forest just outside Oslo in Norway. Upon their maturation, the trees will be felled and made into an anthology of books. The anthology will be made up of a collection of writings by selected authors, one per year, over the next hundred years. Each volume will only be read once printed and housed in a purpose-built library in 2115, in Norway. As this work indicates, we see in Paterson the transformation of the role of artistic subjectivity shifting from the person to multiple points across a collection of objects, materials, and networks. As Nicholas Bourriaud suggests, Paterson’s work “presupposes a way of seeing that is beyond human”. And whilst her work is certainly the outcome of an individual’s agenda and labor it also functions to move beyond it. The internal intention for a work of art as an expression of an individual self, as previously conceived, does not then frame the operations through which this process occurs.

Figure 5. Katie Paterson, Future Library Photo © John McKenzie 2015. Future Library is commissioned and produced by Bjørvika Utvikling, and managed by the Future Library Trust. Supported by the City of Oslo, Agency for Cultural Affairs and Agency for Urban Environment

Paterson’s “Future Library” revolves around playing with scale and time, both of which are central to her articulation of the posthuman sublime (see Le Feuvre Citation2017). Again, the everyday objects she uses to convey her findings are instrumental. They anchor the cosmos to the earth, collapsing the distance between them. In so doing the assumed separation between us and the cosmos is ruptured. This is as Tufnell (Citation2014) notes a sensibility that underlies much of the artist’s work; for whilst the object may be present before our eyes they never the less denote something elsewhere, often not only across distances but also time. Others, such as curator Nicholas Bourriaud, suggest a potentially counter reading in relation to Paterson’s work. Invoking the writing of art historian and cultural theorist Aby Warburg in thinking through Paterson’s work, Bourriaud suggests that Paterson’s use of the cosmos is akin to Warburg’s use of the term for it “represents a space that is empty, open and receptive, a space for projections. In short, the opposite of the immediacy of contemporary communication, which eliminates time and distance” (Citation2016, 5). The ambiguity that pervades Paterson’s work ensures that both readings are legitimate and can exist side by side. In this, they reflect a wider uncertainty over how our relationship with time and space has altered with the advent of technology. And whilst some may suggest that Paterson’s work reveals the unequivocal authority we now have over our world and the stars, this is in fact more accurately a recognition of a new relationship with the natural world and the cosmos beyond, in which it speaks back. It has gained an authority that it was previously lacking. With this we can clearly see a breakdown or a renegotiation in the terms that once framed the historic sublime. The affirmation of the human that the sublime once supported is called into question in the posthuman sublime.

Aligning Paterson’s work with the posthuman sublime offers an interpretation of her work that attempts to qualify the artist’s relationship to her practice. But this is not without its drawbacks. Like the criticism levelled at the posthuman itself there are a number of issues that this alignment raises. Perhaps the posthuman claims too much. In its attempt to convey alien otherness, whether it is of the cosmos or technology itself, the self is side-lined. But this otherness is never truly adequately conveyed and there exists a residual anthropocentrism that is at odds with the claims of the posthuman, and indeed, within Paterson’s work too. Through her work, she posits, and arguably celebrates the potential of art to no longer be subject-centred. How this affects our self-understanding is one repercussion of her work. This, however, is not really her aim. Instead it is more accurate to suggest that she asks us to consider how the world turns without our input. This is not a nihilistic move but an acknowledgement that there are forces greater than us. Larsen advocates a similar stance in relation to Paterson. In his writing he takes as given the rise of the anthropocene and the self-destructive nature of how we treat the environment, what he terms a negative anthropology. But he sees within Paterson’s work what he defines as an intuitive suggestion which refuses to give way entirely to this line of thinking: her work “departs from this disintegration between anthropological and cosmological domains” (Citation2016, 221).

This disintegration is kept at bay by the spectre of the self in Paterson’s work. As we have previously mentioned in relation to the piece “Candle” (2015), sometimes this is a more obvious reflection on the artist’s own subjective feelings. But more often the artist is absent entirely and instead she provides us the opportunity to reflect on our place in relation to the phenomena she displays. Thus, the refutation of the person is not complete. More broadly, this is achieved through her reliance on the historic sublime, which acts as a relational component of her work, and alongside conceptualism is the framework through which she articulates her ideas. But whilst setting up the sublime as a straw man to enable her to illuminate the voice of other non-human actors, she never takes this to its conclusion and the shadow of the artist remains. But this indeterminacy is arguably the purpose of her work in which resolution is not the point. The power then of her work is in its ability to offer competing, contradictory positions that each sheds light on the other. Like theorist Donna Haraway (Citation2017) in her commentary on the anthropocene, Paterson seems to suggest that we should stay with the trouble of the sublime. If the sublime is essentially an exercise in trying to find our place in the landscape, then there is still much to be gained from engaging with this aesthetic category. Have we, for instance, really abandoned the artist’s voice in favour of the non-human? At its best Paterson’s work suggests there is room for both. Haraway’s work on the anthropocene is relevant here and speaks to the benefit of maintaining an equivocal stance. For Haraway, the anthropocene has been used as a means of suggesting an inevitable fate. Here Haraway evokes two terms to qualify and counter this: firstly, the “capitalocene”, which recognises the role that capitalism has played in the destruction of the planet, and the allied power inequalities that fuel it; secondly, the “chthulucene”, which Haraway uses to draw attention to the earth itself and the critters that live on it as a way of seeing a path forward. Etymologically derived from the word “chthon”, meaning “earth” in Greek, the concept for Haraway posits a “third story, a third netbag for collecting up what is crucial for ongoing, for staying with the trouble” (Citation2017, 12), that the anthropocene and capitalocene fail to provide. Specifically, here she suggests that we should look to “multispecies stories” and their practices of living. For the chthulucene is a call to take seriously the voice of others species and in so doing concede that humanity is part of a wider compost, in Haraway’s terms. This is a means through which we “stay with the trouble” that the anthropocene proposes. For her, citing the title of the book that takes this topic as its subject, the inevitability that is characteristic of the anthropocene is entirely misleading and unwarranted. We can see something of this played out across Paterson’s work, for staying with the trouble of the sublime is to stay with the trouble of the self. The individualism that is under threat within the posthuman sublime is entirely warranted. This is as it should be. But Paterson’s work is also a gentle reminder of the hurt of its entire abandonment. We see played out in her work the question of the role of the artist in the interstices between science, technology and the arts. Is the artist to be merely the spokesperson for the voice of others? Is the posthuman self to be entirely premised on its absence?

Conclusion

The individual artist is quelled and correspondingly transformed in Paterson’s work through her ability to articulate the structures and processes normally hidden from us. In this way the register of interiority shifts and the artistic subjective self is dispersed and reconstructed through alternative frames of reference, most notably geological time and the space of the cosmos. Overall Paterson’s work functions to question the role of the artist, which for her is more akin to that of a facilitator for the voice of others, others which are often, increasingly, non-human. In doing so art can no longer be pigeon-holed to a singular subjective, internal, self but is realized or even dissolved across competing articulations. Paterson’s ability to convey the philosophical implications of our technological advances within the realms of the quotidian ensures that her posthuman sublime is not the rejection of the human but something closer to its opening out. Not explicitly transcendent however, for her work does not offer the resolution that this would entail.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. The genesis of the posthuman, for Wolfe, orientates with systems theory. First articulated in the late 1950s by Gregory Bateson, Warren McCullouch, Norbert Wiener (see Wolfe Citation2010).

2. Images of Katie Paterson’s work can be viewed on her website: http://katiepaterson.org.

3. The idiom of the sublime has been a category that has been in flux since classical antiquity. First articulated by the first-century Greek writer Longinus, in Peri Hupsous, who limited to a literary style (see Guerlac Citation1985), it rose to prominence in the 18th century with Edmund Burke in his treatise on the subject A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful (1757) and following that, Immanuel Kant’s The Critique of judgment (1790).

4. Romanticism was instrumental in shaping the figure of the artist-genius, which saw a transformation from the artisan craftsman in the 18th and 19th century. An early text that instigated these ideas is Edward Young’s Conjectures on Original Composition from 1759. As Parker and Pollock state “these developing notions reached new heights with the genesis of the Romantic myth of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries when the artist not only inherited the mantle of priests and became the revealer of divine truths but assumed a semi-divine status as an heir to the original ‘creator’ himself” (1981). And as they go on to suggest “today, to be an artist is to be born a special person; creativity lies in the person not in what is made” (ibid.). Thus, the concept of the genius for the romantic sublime ensured that the artist was subjectively linked to the work they produced. And whilst this trend has both continued apace into the 20th century with artists who are closely aligned with the traditions of this movement, there are artists that pushed back against the romantic sublime. Paterson is directly heir to this lineage, and so the role of artistic subjectivity and how she works with and against it is directly relevant to her practice. For an overview of the legacy on romanticism more broadly for modernism see Cavell (Citation1979). There are also scholars that suggest that romanticism has had a lasting influence on postmodernism through its blurring of the distinction between the real and the imagined, and their focus on the fragmentary nature of experience (see Bowie Citation1990).

5. See the Tate’s research project, The Sublime Object: Nature, Art and Language, which held a summative symposium in 2007 at Tate Britain. In addition, some key exhibitions include: “The Sublime Void”, Musée des Beaux Arts, Brussels (1993); “The Big Nothing”, the ICA in Philadelphia (2004); “On the Sublime”, Guggenheim, Berlin (2007); “Various Voids: A Retrospective”, Centre Pompidou (2009).

6. For further literature on the cosmos in art see Clair (Citation1999).

References

- Alfrey, N. 2009. Transmission, Reflection and Loss: Katie Paterson’s Earth-Moon-Earth’, Exhibition Catalogue for Earth-Moon-Earth. Nottingham: Djanogly Art Gallery.

- Alfrey, N., and R. Partridge. 2018. Scaling the Sublime: Art at the Limits of Landscape. Exhibition Catalogue. Nottingham: Djanogly Gallery.

- Badmington, N., ed.. 2000. Posthumanism. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave.

- Barad, K. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

- Battersby, C. 2007. The Sublime, Terror and Human Difference. Abingdon and New York: Routledge.

- Behrman, P. 2010. “Katie Paterson”. Art Monthly, issue 338: July-August, p. 25.

- Bell, J. 2013. “Contemporary Art and the Sublime.” In The Art of the Sublime, edited by N. Llewellyn and C. Riding. Tate Research Publication, January.

- Bennett, J. 2010. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

- Bourriaud, N. 2016. “Foreword.” In Kate Paterson,edited by J. Bewley and J. Tarbuck, p5-9. Newcastle and Berlin: Locus+ and Kerber Verlag.

- Bowie, A. 1990. Aesthetics and Subjectivity: From Kant to Nietzsche. Manchester and New York: ManchesterUniversity Press.

- Brady, E. 2013. The Sublime in Modern Philosophy: Aesthetics, Ethics and Nature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Braidotti, R. 2013. The Posthuman. Cambridge: Polity.

- Callus, I., and S. Herbrechter. 2012. “Introduction: Posthumanist Subjectivities, Or, Coming after the Subject ….” Subjectivity 5: 241–12.

- Cavell, S. 1979. The World Viewed. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Clair, J., ed. 1999. Cosmos: From Romanticism to the Avant-Garde. Munich, London, New York: Prestel.

- Courtine, J.-F., ed.. 1993. Of the Sublime: Presence in Question. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Dolphijn, R., and I. Van Der Tuin. 2012. New Materialism: Interviews & Cartographies. Ann Arbor, MI: Open Humanities Press.

- Elkins, J. 2011. “Against the Sublime.” In Beyond the Infinite: The Sublime in Art and Science, edited by R. Hoffman and I. Boyd Whyte, 75–90. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ferrando, F. 2016. “The Party of the Anthropocene.” Relations 4: 2.

- Foucault, M. [1966] 2001. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. London and New York: Routledge.

- Gilbert-Rolfe, J. 1999. Beauty and the Contemporary Sublime. New York: Allworth Press.

- Guerlac, S. 1985. “Longinus and the Subject of the Sublime.”NewLiterary History 16 (1985): 275–89.

- Hall, N. A. 2020. “On the Cusp of the Sublime: Olafur Eliasson’s Ice Watch.” Journal of Comparative Literature and Aesthetics 43 (2): 3–21. Summer.

- Haraway, D. 1985. “Manifesto for Cyborgs: Science, Technology, and Socialist Feminism in the 1980s.” Socialist Review 80: 65–108.

- Haraway, D. 2017. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Hayles, N. K. 1999. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Jacob, M. J. 2016. “The Gedankenexperiments of Katie Paterson.” In Kate Paterson, edited by J. Bewley and J. Tarbuck, p9–22. Newcastle and Berlin: Locus+ and Kerber Verlag.

- Jameson, F. 1991. Postmodernism, Or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. London and New York: Verso.

- Lajer-Burcharth, E., and B. Söntgen, eds.. 2015. Interiors and Interiority. Berlin and Boston: Walter De Gruyter.

- Larmore, C. 1996. The Romantic Legacy. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Larsen, L. B. 2016. “Astronomy Domine: The Anthropological – Cosmological Squeeze in Katie Paterson’s Work.” In Kate Paterson,edited by J. Bewley and J. Tarbuck, p. 221-226.Newcastle and Berlin: Locus+ and Kerber Verlag.

- Latour, B. 2005. Reassembling the Social. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Le Feuvre, L. 2017. “The Time of the Artwork.” In Kate Paterson, edited by J. Bewley and J. Tarbuck, p161–166. Newcastle and Berlin: Locus+ and Kerber Verlag.

- Lyotard, J.-F. 1982. “Presenting the Unpresentable: The Sublime”, trans. Lisa Liebmann, Artforum April: 64-9

- Lyotard, J.-F. 1991. The Inhuman: Reflections on Time. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- McCornmack, P. 2016. Posthuman Ethics: Embodiment and Cultural Theory. London and New York: Routledge.

- Morley, S. 2010. Sublime. London and Cambridge, Massachusetts: Whitechapel Gallery and The MIT Press.

- Normand, V. 2015. “In the Planetarium: The Modern Museum on the Anthropocenic Stage.” In Art in the Anthropocene, edited by H. Davis and E. Turpin, 63–79. London: Open Humanities Press.

- Nye, D. 1994. American Technological Sublime. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- O’Reilly, S. 2016. “Of Great Magnitudes and Multiplicities”, Lowry exhibition essay, May.

- Ottinger, D. 1999. “Contemporary Cosmologies.” In Cosmos: From Romanticism to the Avant-Garde, edited by J. Clair, 282–323. Munich, London, New York: Prestel.

- Relyea, L., R. Gober, and B. Fer. 2004. Vija Celmins. London: Phaidon.

- Scharff, R. C., and V. Dusek. 2003. Philosophy of Technology: The Technological Condition. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Tufnell, B. 2014. “Katie Paterson, Sand and Stars”, 2017.katiepaterson.org, www.2017.katiepaterson.org/wpcontent/uploads/2017/04/Katie_Paterson_Springhornhof_text_Ben_Tufnell_2014.pdf

- Vaughan, W. 1994. Romanticism and Art. London and New York: Thames and Hudson.

- Wilson, A. 2016. Conceptual Art in Britain: 1964-1979. London: Tate Publishing.

- Wolfe, C. 2010. What Is Posthumanism? Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.