ABSTRACT

This article contextualises a previously unpublished manuscript on the subject of kitsch written in 1922 by the Bauhaus practitioner Oskar Schlemmer and provides an original annotated translation as an appendix. The article positions Schlemmer’s manuscript as a response to debates about the aesthetics of kitsch among his contemporaries in the German and Austrian intelligentsia, including Austrian architect Adolf Loos; Stuttgart-based art historian and member of the Deutscher Werkbund Gustav Pazaurek; the founding member of the Dürerbund, Ferdinand Avenarius; and the avant-garde satirist Frank Wedekind. Schlemmer’s unpublished manuscript is also located as part of a broader response to the social upheavals of industrialisation and the First World War, where the concept of kitsch figured centrally in discussions among taste-makers about the progress and purpose of art and design in the new century. While “kitsch” in Germany before 1920 was generally considered to be in poor taste and an expression of bourgeois excess, Schlemmer argues that not all kitsch is bad. Schlemmer’s manuscript highlights a shift, following the First World War, in attitudes among the German avant-garde towards what constituted kitsch and the role that it may have had on design inspiration within modernist theatre. Like Pazaurek, who classified different categories of kitsch, Schlemmer, too, identifies a new category of kitsch—“true” kitsch—and states not only that it appears as an expression of the joy found in popular entertainment, such as at circuses and market fairs, but that it is beautiful and as such should be celebrated.

Introduction

An unpublished manuscript on kitsch sits in AOS Box 2, Mappe 2 Manuskripte/Briefe 1919–1922 at the Archiv Oskar Schlemmer in Stuttgart, Germany. Written in 1922 by the German artist, designer and Bauhaus practitioner Oskar Schlemmer (1888–1943), the essay predates Fritz Karpfen’s Der Kitsch: Eine Studie über die Entartung der Kunst (Kitsch: A study into the degeneration of art) (Citation1925) and Walter Benjamin’s (1892–1940) work on kitsch, which commenced in the late 1920s and continued until his death. This article considers Schlemmer’s 1922 manuscript within the context of debates among prominent art historians, educators, artists and intellectuals in Germany and Austria before, during and immediately after the First World War about what constituted kitsch and its relationships to folk art and popular taste. The problem of kitsch was widely debated and discussed in Germany and Austria in the first two decades of the twentieth century by figures such as Austrian architect Adolf Loos (1870–1933); Stuttgart art historian, critic and Deutscher Werkbund (DW) member Gustav E. Pazaurek (1865–1935); and conservative lyric poet, DW member and founding member of the DürerbundFootnote1 Ferdinand Avenarius (1856–1923).Footnote2 The primary critiques considered here include Loos’s manifesto, Ornament and Crime (Citation1910, 1970),Footnote3 Pazaurek’s Guter und schlechter Geschmack im Kunstgewerbe (Good and bad taste in the applied arts) (Citation1912), Frank Wedekin’s unfinished play entitled Kitsch (Citation1917), and Avenarius’s essay “Kriegs-Kitsch” (War kitsch) (Citation1916) and his ([Citation1920] 2007) exploration of the etymology of “kitsch” in his monthly newspaper, Der Kunstwart. These texts serve as key reference points for Schlemmer’s meditation on kitsch, while Wedekind’s farce provides insight into how kitsch had come to be viewed, within art and design circles, as the dominant popular aesthetic of the postwar era, despite rigorous attempts by German taste-makers to stamp it out.

Schlemmer’s manuscript highlights a shift, following the First World War, in attitudes among the German avant-garde towards what constituted kitsch and points to the role that this shift may have had on design inspiration within modernist theatre. Like Pazaurek, who classified different categories of kitsch in 1912 and Avenarius, who expanded Pazaurek’s taxonomy of kitsch in 1916 to include two new categories of kitsch, Schlemmer, too, identifies a new type that he calls “true” kitsch, which is found at circuses and market fairs like Oktoberfest. This “new” category in fact had its roots in prewar Germany: Pazaurek, for example, lambasted market fairs as sources of kitsch (Citation1912, 354), while Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), who was a colleague of Schlemmer’s at the Bauhaus, also identified connections in 1913 between kitsch and the commercialised folk art at Oktoberfest (Obler Citation2006, 86). Schlemmer argues in 1922, however, that such kitsch is not only an expression of the joy and fun found in this form of popular entertainment, but is also beautiful and must therefore be celebrated. This article thus aims to situate Schlemmer’s thinking about the aesthetics of kitsch in Weimar society within the context of these key discourses on taste by German and Austrian intellectuals, artists and the avant-garde as an introduction to the annotated translation into English of Schlemmer’s unpublished manuscript on kitsch, which is provided in Appendix 1.

Striving for good taste: Avenarius and Pazaurek

Avenarius’s exploration of the etymology of the term “kitsch” appeared in 1920 in Der Kunstwart. The journal was published in Dresden between 1887 and 1937 by Avenarius, Wolfgang Schumann and Hermann Rinn, and focused on promoting good taste in poetry, theatre, music and fine and applied arts. It was, between its inception and the start of the First World War in 1914, considered one of the leading contributions to the cultural education of students in Germany. Avenarius writes that the term “kitsch” arose in the late nineteenth century within German aesthetic and philosophical circles in response to the rise of industrialisation and mass production. The term blended similar-sounding words found in different German dialects, English and Russian, which allowed it to encapsulate a range of meanings linked to art, tourism, mass production, fashion and commerce. Kitsch was linked to art from beginning; the term itself was derived from the German word Skizze, which means “sketch”. These terms were used by middle-class English and American tourists in Munich in the 1870s and 1880s to order small, cheap souvenirs from street artists (as in, “I’d like a sketch”) (Avenarius Citation1920, 2007, 89–90). The word was also tied to the following terms:

The Southwest German word kitschen, which is the verb “to smooth” sludge/mud on the street with a tool like a daub called a Kotkrücke [also known as a Kitsche]. The metonymic derivation of “mud” (Matsch in German) also supported the association of kitsch with waste and trash.

The usage in the Mecklenburg and Rheinland regions of Germany of Kitschen as a term for cheap, quickly made, disposable objects.

The Russian КИЧИТЬСЯ, which roughly means “to brag” or “to boast”. This usage was linked to excess, status and the consumption of fashion, and corresponded with what the American sociologist Thorstein Veblen (1857–1929) called the “conspicuous consumption” of valuable and luxury goods by the leisure classes (Veblen Citation1899).

The Swabian and South German noun Kitsch, which is an off-cut of wood, or rubbish; and the verb verkitschen, which means to sell and trade on a small scale. (Kliche Citation2010, 275–6)

These linguistic derivations quickly meant that objects classed as kitsch were placed outside the realm of refined high art and tied to consumer and industrial culture. Avenarius notes that “the artist considers a picture to be kitsch if it appeals broadly to popular tastes, while also being easy to sell” ([Citation1920] 2007, 90). The aesthetic of kitsch also quickly became associated in Germany with cheap, highly ornamental, mass-produced goods that generally portrayed an exaggerated sentimentality, warmth and/or melodrama. The term grew in popular usage from the 1880s and the German fascination with the aesthetic of kitsch continued into the early twentieth century, when it coincided with the advent of large-scale industrialisation and massive urbanisation.

In 1909 Pazaurek established himself as an authority on the subject of kitsch when he founded the Museum of Kitsch in Stuttgart in connection with the Kunstgewerbeschule Stuttgart (Stuttgart School of Applied Arts). Pazaurek’s museum largely comprised applied arts-and-crafts objects that he deemed Geschmacksverirrungen, or aberrations of taste, and extended the design ethos espoused by the DW. The DW was founded in Munich in 1907 by Peter Behrens, Justus Brinckmann, Alfred Greander, author and diplomat Hermann Muthesius (1861–1927), who was well known for promoting the English Arts and Crafts movement in Germany, Theodor Fischer and others to foster working partnerships among artists, designers, architects, product manufacturers and industry. Its aim was to integrate traditional methods of craftsmanship into industrial mass-production techniques in order to develop a unified German identity and make Germany a leading global manufacturing centre. The idea of creating a unified German identity was important in 1907 as Germany had only been a unified nation for thirty-six years. The ideals of “good taste” and craftsmanship were seen as solid values that Germans from all of the twenty-six German-speaking states that constituted the German Empire could agree on. The Museum of Kitsch and Pazaurek’s design theory informed Schlemmer’s early thinking on the subject of kitsch: in 1906 Schlemmer won a scholarship to attend the Akademie der Bildenden Künste (Academy of Fine Arts Stuttgart) between 1906 and 1910; prior to that, he studied at the Kunstgewerbeschule Stuttgart; and his 1922 manuscript refers directly to the Museum of Kitsch.

The DW believed that a focus on craftsmanship in production would inspire workers to produce tasteful, high-quality goods in an industrial setting, an ideal that supported the “German bourgeois, nationalist-industrialist cause and … translated the aristocratic sense of purpose into a principle of visual culture” (Jarzombek Citation1994, 13–14). This philosophy led to an ideology of aesthetics within the DW that “lay in a highly moralized discourse surrounding what came to be known as die Kultur des Sichtbaren (the culture of the visible)” (Jarzombek Citation1994, 9). The view was that if the middle-class German “were to avoid the vices of rootless capitalism, [he] would have to be taught not so much how to behave, vote, or think, but ‘how to dress, how to furnish his room and his house, even how to walk down the street’” (Jarzombek Citation1994, 9–10). The propagation of the concept of quality within the applied arts was central to the DW, and Fischer noted from the outset of the DW that this was to be supported through exhibitions that were deliberately designed to communicate an understanding of what constituted both good quality and good taste (Fischer Citation1908, 46–7). The DW was diligently dedicated to fighting bad taste, which, as Pazaurek aimed to demonstrate, had infiltrated every aspect of modern urban life in Germany as a result of mass production. The Museum of Kitsch would therefore have had the dual purpose of entertaining the nation’s bourgeoisie and educating them on how to be “good Germans”—that is, by guiding them away from the consumption of kitsch towards the consumption of tastefully designed, high-quality, German-made goods.

Following Pazaurek’s 1909 exhibition of kitsch, the German press increasingly described paintings, literature, theatre, applied arts, advertising posters, and even the burgeoning medium of motion pictures that were in poor taste as “kitsch” (Kliche Citation2010, 275). By 1912 the term “kitsch” had been firmly established in common usage in German, and Pazaurek’s treatise Guter und schlechter Geschmack im Kunstgewerbe (Citation1912) was published with the aim of articulating and guiding the development of good taste among practitioners and the public alike by discussing the design and construction of applied arts and crafts. Pazaurek opines that kitsch is the

absolute antithesis of high quality, artistic works; it is tasteless, mass-produced trash that in no way concerns itself with aesthetic, ethical or logical demands. Kitsch is a crime and offence against materials and technique; it is completely indifferent to purpose and form and only has one purpose: a kitsch object must be as cheap as possible, but must at least evoke some semblance of appearing to be a precious, valuable item. (Citation1912, 349)

Pazaurek’s treatise focused on what constituted good taste within materiality, form, line, ornamentation and construction techniques, and provided detailed examples of what constituted bad taste and made an object kitsch, including an excessive use of ornamentation.

Pazaurek’s book, which also likely influenced Avenarius, acknowledged that the rise of poorly-made “kitsch” goods within the applied arts sector was a direct result of nineteenth-century industrialisation and mass-production in the various German states. For example, as early as 1827, the finance minister for King Wilhelm I of Württemberg, a Herr Weckherlin, noted that the kingdom’s industries could not improve as long as manufacturers refused to adhere to the principles of good taste within the production of applied arts (Pazaurek Citation1912, 349). Indeed, Kaiser Wilhelm II (1859–1941) expressed a similar sentiment in 1901, though he did not specifically use the term “kitsch”. His Majesty’s speech on “True Art”, delivered at the December 1901 unveiling of the last monument on Berlin’s Siegesallee, warned that “art that violates the laws [of aesthetics] … is no longer art. It is factory production, commercialism, and that can never be art” (Wilhelm II Citation1901, emphasis in original).

Pazaurek’s study also positions kitsch as a commodity aesthetic that, like popular culture itself, is easy to obtain and consume and is enjoyed within the domestic sphere. He rails against the commercial production of knick-knacks and souvenirs tied to religious and patriotic festivals, famous cities, “gifts for all occasions” and trinkets linked to advertising. These objects are kitsch even if they are created with a modicum of artistic endeavour, because they are made with the express intent to make money (Pazaurek Citation1912, 350). Examples of such kitsch include the souvenir ashtrays, Christmas tree ornaments, spoons, coins, sweets, cups and clothes that are commonly found at every Jahrmarkt (market fair), jubilee celebration and theatrical production, church, and event where cheap commemorative items are sold (Pazaurek Citation1912, 354). Pazaurek included examples of all of these types of objects in his Museum of Kitsch, and his 1912 work contains photographs of many of these objects, including a porcelain beer mug shaped like the head of the former German Chancellor, Otto von Bismark (1815–1898), as seen in . Pazaurek’s Museum of Kitsch was so popular in the prewar years that it attracted visitors far and wide, it was the subject of numerous newspaper and magazine articles, and its exhibits were replicated in other German cities (Kliche Citation2010, 274). The widespread popularity of Pazaurek’s work, along with the work of other groups including the DW and the Dürerbund, meant that the ideas of what constituted an object of kitsch were firmly cemented within the German popular imagination in the years preceding, and during, the First World War.

Figure 1. Otto von Bismark beer mug, an example of what Pazaurek classified as “Hurra-Kitsch”, or kitsch linked to patriotic sentiments. Image from Pazaurek (Citation1912, 351)

It was through the association of kitsch with bad taste that the DW could offer a new model of bourgeois refinement that would, in its view, elevate well-made and well-designed, yet commercial, products to the status of art. The introduction of the distinction between “high” and “low” culture in an era of mass production meant that the DW in Germany felt it could be assured of its continued relevance as the new arbiter of taste and of promoting industrially made German goods at home and internationally.

Classical Kitsch: Loos, Wedekind and the critique of German Nostalgia

In early twentieth-century Germany, taste was a significant site of cultural contestation in the construction of bourgeois identity. According to Frederic Schwartz, bourgeois intellectual tussles over the meaning of culture and its relationship to the German nation were articulated in response to “the social decline of the traditional educated bourgeoisie; the rise of a nouveau riche seeking legitimation; and the political marginalization of both groups in the new German Reich” (Citation1996, 14). Among the bourgeoisie, the “longing for a precapitalist past as a more or less radical critique of modernity” formed “the common core of the discussions of Culture in Germany” (Schwartz Citation1996, 14). These discussions often idealised life in precapitalist rural and artistic communities because there was a broad social perception that the rapid rise of urban, industrialised life in Germany had created a loss of a common spirit and the alienation and isolation of the individual (Schwartz Citation1996, 14). This sense of loss of authenticity would be expressed most famously in Walter Benjamin’s 1935 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” ([Citation1935] 1969). But anxieties about the eradication of the arts and the cultural and economic place of the artisan with the onset of industrialisation were not restricted to Germany. These concerns had also given rise to the earlier British Arts and Crafts Movement, led by decorative artist William Morris (1834–1896). Morris argued for the restoration of the decorative arts in an age in which the craftsman’s relationship to the product had become alienated by machines. His romantic ambition was to reunite the craftsman with the object of his labour through the ornamental arts, which would recentre art as culturally valuable and reinvest the modern age with a rejuvenated passion for beauty and pleasure (see Morris Citation1898; Thompson Citation2011, 658). Morris’s ideas about the importance of the craftsman were also central to the founding principles of the DW.

Yet ornament, too, eventually came under attack by members of the German-speaking intelligentsia, who came to regard as kitsch the decorative styles that had become increasingly popular among the bourgeoisie, such as Jugendstil (the German response to Art Nouveau) and the Neubarok (Neo-Baroque) and Neugotik (Neo-Gothic) revival styles particularly in churches and civic centres. Around 1900, Jugendstil was a popular aesthetic style that dominated the German marketplace, and because of its pretensions to being the modern expressive form, it was vulnerable to critique as an example of a manufactured style without substance. For example, even Muthesius ridiculed the “exaggerated forms and superficial ornaments” of Jugendstil as a “false culture” (Scheinkulture) (Jarzombek Citation1994, 13). In 1909, Viennese architect Adolf Loos gave a lecture titled “Critique of Applied Art” (Kritik der angewandten Kunst) at the gallery of the art dealer Paul Cassirer, where he launched a scathing attack on the so-called floral branch of Jugendstil, targeting painter and graphic artist Otto Eckmann (1865–1902), whose work had already begun to look dated. The lecture was an early version of his manifesto, Ornament and Crime (Loos Citation1910, 1970; Long Citation2009, 203–4), in which he declared ornamentation to be in bad taste (and, by association, kitsch). Loos’s new framework explicitly linked “bad taste” to criminality and degeneracy. He declared that the “ornament disease” was a “symptom of degeneracy” in the modern world, equating it with the primitive erotic symbology of children, childlike races (the “Papuans”) and criminals. Using the language of evolutionary eugenics, Loos argued that “the evolution of culture is synonymous with the removal of ornament from utilitarian objects” ([Citation1910] 1970, 20, emphasis in original). In Loos’s view, ornament had become an evolutionary throwback, irrelevant to the new age and an obstruction to “the cultural evolution of the nations and of mankind” ([Citation1910] 1970, 21). For Loos, ornamental and revival styles eclipsed the beauty of utility, represented the retardation of artistic progress and were anachronistic.

Between 1900 and the close of the First World War, revival styles were often seen by a new generation of young artists as kitsch because they were thought to be imitative, passé and in no way indicative of society, and later, the reality of war. This included artists like the expressionist Gabriele Münter (1877–1962), who in 1905 described the art of the previous generation as kitsch, specifically the work of Conrad Kiesel (1846–1921), a painter who was favoured by the conservative Kaiser Wilhelm II (Obler Citation2006, 46). In his 1916 essay, “Kriegs-Kitsch” (War Kitsch), Avenarius similarly lamented that it would be marvellous to have a genuine Pathetiker (someone who paints with great pathos) to express the ‘Spirit of 1914ʹ, rather than the glut of revival-style images of muscle-bound, Old-Germanic men and women in heroic poses that appeared in patriotic pictures everywhere, such as on postcards and in every memorial page (Citation1916, 67). This jingoistic climate of patriotism and the category of “Pathos-kitsch” that Avenarius claimed emerged in response to the war meant that

contemporary dwellings and men’s minds alike are being soiled and slimed with so much bad art (Unkunst) from all sides – by men of commerce, through illustrated magazines and books, through different clubs, by the authorities – that it will likely take decades to clean them. (Avenarius Citation1916, 67)

In 1917 the avant-garde German satirist, actor and playwright Frank Wedekind (1864–1918) wrote in his unfinished play, Kitsch, that “Kitsch was the contemporary form of the Gothic, Baroque, Rococo and Biedermeier” ([Citation1917] 2007, 44). Here, Wedekind ridicules as “kitsch” the architectural and interior revival styles—Gothic, Baroque, Rococo and Biedermeier—heavily favoured by the bourgeoisie, which, at that time, embodied the essence of German nostalgia. Wedekind was no stranger to poking fun at bourgeois taste. His dramas—Spring Awakening (Citation1891), Earth Spirit (Citation1895) and Pandora’s Box (Citation1904)—and his essays, cabaret performances and contributions to the illustrated weekly satirical magazine Simplicissimus (published in Munich) regularly mocked establishment authority and offered stinging criticisms of conservative German bourgeois attitudes to sex, class and social hierarchy, as well as the artistic and material expressions of those attitudes (Garebian Citation2011, 52). Wedekind, who had performed with a circus when he was younger, understood the appeal of kitsch within popular entertainment, and the existing fragment of Kitsch shows that it is a farce that draws on the conventions of clowning and burlesque. The characters are exaggerated caricatures through which Wedekind mocks the passionate defence of art and taste in contemporary German society as itself belonging to the realm of “kitsch”.

Kitsch contains a scene in which Zugschwert, a professor of art history who represents the traditional educated bourgeoisie, and Robert Peter, a divorced bohemian modernist painter, argue because Zugschwert has caught Peter in the act of cheating with Mathilde, a young woman who is involved with both men. Peter’s presence is detected as Zugschwert enters his own apartment and finds Peter’s top hat sitting on an antique bust of the Greek goddess of family and motherhood, Hera, underscoring Wedekind’s lampooning of conservative bourgeois family values. Zugschwert then creeps to the curtain covering a door and pulls it aside with a scream of fright at finding Peter standing there. The two men begin to brawl about the infidelity, which results in Zugschwert insulting Peter by opining that his paintings are not art because modern art is kitsch and real art is made in the “absolute” aesthetics of the classical tradition (Wedekind Citation1917, 2007, 44). Peter retorts that he would rather starve in penury than paint in classical styles that Zugschwert prefers because it is those paintings that are kitsch, and their only value is to be sold at the Jahrmarkt. In this sentiment, Peter typifies the modernist “indictment of kitsch as a cultural product that was superficially attractive, yet fundamentally empty of Geist and sullied by a desire for publicity and profit” (Simmons Citation2000, 87). This exchange is grounded in the full usage of the term “kitsch” in German during 1917 and demonstrates Wedekind’s understanding of the slippery subjectivity of kitsch and its use as a pointed satirical barb.

Wedekind’s use of dramatic conventions conveys the sense that even having such debates about the nature of art is kitsch. Peter’s retort was an expression of the disdain of the young artist towards the old order; but it was also a rebuke of the romantic nostalgia for the past that had dominated discussions of culture-in-crisis, which exhibited a romantic longing for “a past in which the modern socioeconomic system was not yet fully developed. Nostalgia for this lost paradise [was] generally accompanied by a quest for what [had] been lost, an attempt to recreate … the ideal past state, although [not] … literally” (Sayre and Löwy Citation2005, 435–6). This rebuke was also evident in Avenarius’s 1916 essay, in which he criticises commercially produced art that drew on Old-Germanic imagery and imitated genuine feelings in hollow, superficial paintings. The exchange between Zugschwert and Peter could also be interpreted as satirising the bourgeois approbation of the Gothic and Baroque revival styles used in the architecture of many German bureaucratic institutions. In Munich, where Wedekind lived, these styles could be seen in structures such as the Neo-Gothic Neues Rathaus (New Town Hall, completed in 1908). Gothic Revival architecture became increasingly popular in Germany in the nineteenth century and contributed to a new regime of historicity linking Christianity and modernity. Within the framework of Sayre and Löwy’s typologies of Romanticism, the Neues Rathaus may be seen to represent both a form of Restitutionist and Conservative German Romanticism, in that it aimed to recreate the feeling of the medieval period in order to “maintain traditional elements of society (and government)” (Sayre and Michael Citation2005, 441). In addition to an interest in Neo-Gothic architecture and imagery, the late-nineteenth-century writings of the Viennese art historian Alois Riegl (1858–1905) also fuelled a renewed social interest in the Baroque in relation to Renaissance art and in the Biedermeier style in relation to Neoclassical design. Biedermeier style, popular in Central Europe between 1815 and 1845 and synonymous in satirical circles with middle-class domesticity, became increasingly ornate throughout the nineteenth century as the bourgeoisie sought to show off their wealth. By the early twentieth century, Biedermeier was “widely seen as a domestic style perfectly embodying the values of the newly empowered central European bourgeoisie, and had been praised by Loos in his early articles as a style whose simplicity had enabled the new elite to rise to new heights of political and artistic expression” (Overy Citation2006, 255). The ideological Romantic nostalgia of Biedermeier revival style, and its links to excessive ornamentation and bourgeois status and wealth, was another of the key domestic material expressions of the very people, and their social attitudes, whom Wedekind sought to satirise as “kitsch”.

Through the character of Zugschwert, Wedekind also makes reference to the use of “kitsch”, among the conservative bourgeois art establishment, to deride modern art as commercialised worthless trash. The artists of Der Blaue Reiter (The blue rider), for example, had come under fire in 1913 by director of museums in Prussia Wilhelm von Bode (1845–1929) for being “sandwich men”—that is, for using “advertising to gain the financial support of rich, female art enthusiasts” (Simmons Citation1999, 125). The association of modern art with rubbish was also echoed in the content of the highly popular Munich-based weekly humour and satire magazine, Fliegende Blätter (Flying pages), which good-naturedly lampooned its target audience, the bourgeoisie. In early 1917, for example, the publication contained the following joke about a man on trial, which pointed to the tensions between the traditional bourgeois establishment and modernist artists

Judge (to Modernist Painter): What is your occupation?

Accused: I paint artworks.

Judge: And what excuse can you give us for that? (Fliegende Blätter, Citation1917, 67, vol. 146 (1), Nr. 3728)

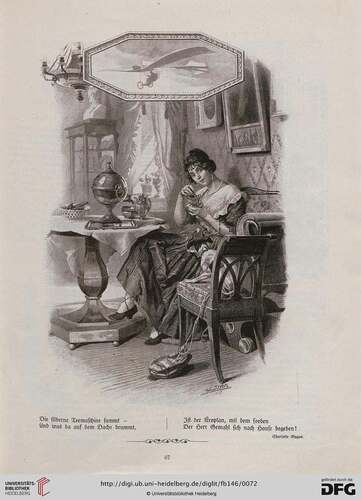

As can be seen from the 1917 issues of Fliegende Blätter, many of its illustrations, poems, stories and jokes aligned with definitions of what avant-gardists like Wedekind considered as kitsch: the written content was often nostalgic and saccharine and lauded Germany’s patriotic soldiers and the virtues of Heimat, while the illustrations were either in a realistic, nineteenth-century “sketch” style, like those produced for the magazine by the Austrian architectural and landscape painter Franz Kopallik (1860–1931), or line-drawing cartoon styles. The Fliegende Blätter masthead comprised figures wearing stylised medieval dress, including a jester, which recalled Neo-Gothic motifs, and in early 1917 the publication contained a humorous poem entitled “Modernstes Biedermeier” (Modern Biedermeier), which accompanied a sketch by the Austrian painter and illustrator Franz Xaver Simm (1853–1918), whose art was largely in the Neoclassical Empire style that Wedekind’s Peter finds so abhorrent.

The poem describes a scene of idealised Biedermeier domesticity, with a stylish, pretty young woman sitting in a sunny, elegantly appointed room that includes cherrywood furniture, white muslin curtains, potted flowers and a round table set for tea with fine Meissen porcelain cups and a basket of fresh pastries. The woman’s outfit, which Simm has drawn in the fashions of the mid-1910s, is described in the poem in such a way that it is redolent of mid-nineteenth-century “Biedermeier” women’s fashions, drawing on the image of the woman as a consumer of fashion who served as an “emblem of modernity” and of “the charm and triviality of mass culture” (see ) (Simmons Citation2000, 49). Even the poem’s punchline about the rumble on the roof caused by her husband arriving home in his aeroplane, which juxtaposes the machines of modernity with Biedermeier domesticity, is gently humorous rather than jarring, as it points to “the brave new mechanical world” that, in Germany, had been “particularly associated with the bourgeoisie” since the mid-nineteenth century (Blackbourn and Eley Citation1984, 187). The light humour of the piece evokes the nostalgia of a gemütlich, pre-War bourgeois domesticity for the readers as, perhaps, a temporary antidote to the brutality of the First World War, a sentiment that Wedekind found kitsch.

Figure 2. Franz Xaver Simm, “Modernstes Biedermeier”, Fliegende Blätter, 1917, 67, vol. 146 (6) Nr. 3728. Courtesy of Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg

Wedekind’s 1917 use of the term “kitsch” as a catchphrase for the bourgeois aesthetics of the industrialised era articulated many of the modern, fundamentally anti-classical and anti-traditional attitudes that resulted from the social, political and economic impact of the First World War on Germany (Kliche Citation2010, 274). His description of kitsch was “perhaps the first time that the essence of modernity was specifically identified as kitsch, and that kitsch, for all its strong, derogatory connotations, was seen as a broad historical style, as a distinctive embodiment of the modern Zeitgeist” (Calinescu Citation1987, 224). Yet this essence of modernity that Wedekind found kitsch was grounded in the proliferation of revival styles and the Romantic bourgeois nostalgia production of which they were expressions. To work with Neoclassical and revival styles in 1917 because of all they symbolised was bad taste, and Schlemmer, it appears, held similar views.

Schlemmer and Kitsch: a hate/love relationship

Oskar Schlemmer made his own intervention in these debates about the place of kitsch in culture in an unpublished manuscript he wrote in 1922, which I present here in English translation in Appendix 1. This piece provides a glimpse into the polysemic nature of the concept of kitsch and how it indexed shifting views about art and culture in Germany in a time of intense social upheaval introduced by the First World War, modernity and the struggle between nostalgia/loss and revitalisation of art for a new generation. Even prior to 1922, Schlemmer, like others of his milieu, identified kitsch with a certain artless vacuity, or cliché, and criticised as “kitsch” classical efforts to replicate nature in painting. Such debates about art and kitsch “had been growing for years, but … sharpened from 1914 to 1920 when war and revolution raised new questions about art’s relationship to a mass audience and reproductive technology” (Simmons Citation1998, 18). In the new, modernised century, classical and revival styles appeared stale and lacking in imagination, while the invention of photography had rendered the artistic pursuit of faithful reproduction of the object meaningless. In his unpublished notebooks, Schlemmer wrote:

The struggle in new painting was, in part, directed against the domination of the object. This ruled naturalistic painting, which reached its zenith with Impressionism, but which in our time appears to be reserved within the abyss of kitsch. Replicating nature is an absurdity and stands outside the realm of human capacity. (Schlemmer Citation1918)

Schlemmer argued that attempts to replicate nature in painting had become passé, and proven impossible, because the medium of photography could reproduce a direct copy of an object, liberating painting from the need to do so. This meant that art could be reinvested with new purpose and vigour. For Schlemmer, modernity brought with it the potential for new expressions and forms within the medium of painting (Schlemmer Citation1918). Almost all “avant-garde movements that followed naturalism … turned against it as they saw realism as concomitant with a non-creative, photographic depiction of this stance” (Glytzouris Citation2008, 136). Indeed, Schlemmer, like Wedekind’s Peter, argues that old styles of painting are no longer relevant because new art and forms are expressions of new ideas and symbols of modernity. This is, in part, because, as Schlemmer writes, “In this time of natural and spiritual evolution, in which States and world-views are collapsing, the artist seeks a centre within himself” (Schlemmer Citation1918).

By 1922, however, Schlemmer had refined his thinking on kitsch in his unpublished manuscript Der wahre Kitsch ist Schön (True kitsch is beautiful) (Citation1922a), a document that reveals the trajectory of his philosophy of the place of kitsch within German art and culture. It is clear that Schlemmer’s thinking on kitsch had shifted within his essay since his last discussion of kitsch in 1918, in that kitsch was now no longer a completely maligned style, but one which he sought to rehabilitate and invest with a new cultural value. Like Pazaurek, Avenarius and even Loos, Schlemmer agreed that kitsch relates to an object’s appearance, particularly if its origin, identity and function are purely commercial, and that there existed a particularly gaudy kind of ethos that was embraced by the working classes and bourgeoisie of the early twentieth century. Using what appears to be Pazaurek’s concept of taxonomies of kitsch, which Avenarius expanded in 1916, Schlemmer’s manuscript also considers Avenarius’s etymology of the term to develop the category of “true/authentic” kitsch, as it relates to the aesthetics of the commercialised folk art found at the circus and the German Jahrmarkt, and argues that this type of kitsch is beautiful.

Schlemmer’s association of the concept of authenticity, or “truth”, with folk art and expressions of kitsch alike was likely influenced, in part, by debates on folk art within the German Sprachraum around the turn of the twentieth century. These debates were largely a response to calls for measures “to preserve national folk traditions jeopardized by industrialization” (Obler Citation2014, 32). Riegl’s book, Volkskunst, Hausfleiss und Hauseindustrie (Folk art, domesticity and cottage industry) (Citation1894), posited that folk art was both the “expression of a cultural essence of a people and a preserver of regional and national identities during periods of social change” that existed outside of the commercial economy (Crown and Rivers Citation2013, 1). Riegl’s position, however, was that true folk art was dead—killed by industrialisation. He even implied that “folk art, strictly defined, may never had existed in its absolutely pure form, that it may have only been a romantic dream” (Obler Citation2014, 32). Kandinsky and his partner in the early 1900s, Gabriele Münter (1877–1962), were also “aware of how easily folk art can mutate into kitsch”, using their time in Murnau to explore and exploit in their own work “the tension between folk art and kitsch as part of their investigation into what could constitute a genuine art of their time” (Obler Citation2006, 30–1). Schlemmer’s categorisation of “true kitsch” also likely responded to Pazaurek’s observation that the commercialised folk art styles sold at German market fairs were kitsch (Pazaurek Citation1912, 354). Pazaurek’s statements, in turn, articulated the notion that, for the “self-urbanizing nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the main source of kitsch has been seen in the slackening of the cultural codification of folk cultures and in their subsequent swallowing up by city cultures” (Mihăilescu Citation1997, 51–2). Nonetheless, Avenarius defended authenticity in folk art in 1916, writing that the difference between folk art and kitsch was the idea and intent with which it is produced: “If one thinks and feels genuinely as the ‘Folk’ do, then one is not making kitsch, rather one is making folk art … Kitsch is, therefore, never an expression, rather it is always a formula” (Avenarius Citation1916, 66).

Despite their increasing commercialisation, however, the circuses and market fairs of the 1920s offered Germans an opportunity to have fun and indulge in a sense of social and cultural stability following the nation’s bitter, crushing defeat in the First World War; traditional Christmas markets, for example, have been running in Munich since 1310 and in Stuttgart since 1692, while the annual Bremen Freimarkt in Northern Germany has been held since 1035. Schlemmer’s text also specifically refers to the annual Munich “Oktoberfest”, extolling the joys of an overwhelmingly opulent affair fuelled by Bacchanalian excess. Schlemmer’s reappraisal of kitsch, therefore, agrees that mass-produced kitsch is tasteless, precisely because it is masquerading as high art; yet he argues that the great value of “true” kitsch lies in the context in which it is produced (that is, the circus and the market fair) and the subsequent feelings of joy and pleasure it produces in the beholder/consumer, a telling conflation that draws on the subjectivity of kitsch as well as its purely economic roots. Schlemmer’s manuscript offers the view that the true kitsch of circuses and market fairs is beautiful because such events are authentic cultural expressions of joy and play, and that life would be poorer were these expressions to be eradicated in the name of good taste.

Schlemmer’s love of the “true kitsch” of the fair and the circus points to why, just two years later, he lamented that, outside the Bauhaus, “this materialistic and practical age has in fact lost the genuine feeling for play and for the miraculous. Utilitarianism has gone a long way in killing it” (Schlemmer Citation1924, 1961, 31). His love of “true kitsch” was in keeping with the Bauhaus spirit of learning and developing creativity through play and positive emotions and with the Bauhaus development of theatre, in which Schlemmer was a key figure between 1923 and 1929. These theatrical events, ranging from plays to costume parties, from organized fetes to spontaneous festivities, were decreed by Gropius and “operated as essential binding agents for social life at the Bauhaus” (Koss Citation2003, 738–9). Schlemmer’s own experimental theatre productions for the Bauhaus, for example, include The Figural Cabinet I (Citation1922b), which took the fairground shooting gallery as its inspiration; and while his ideas about the “true kitsch” of the circus and the fair remained unpublished, it is visible as an influence in the works of other Bauhaus practitioners who expressed an appreciation of the skills, experimentation and artistry found in commercial popular entertainment.

Moholy-Nagy’s 1924 essay, “Theatre, Circus, Variety”, draws more direct links to an exploration of popular culture and kitsch. He stated, for example

Today’s CIRCUS, OPERETTA, VAUDEVILLE, the CLOWNS in America and elsewhere (Chaplin, Fratellini) have accomplished great things in eliminating the subjective – even if the process has been naïve and often more superficial than incisive. Yet it would be just a superficial if we were to dismiss great performances and ‘shows’ in this genre with the word Kitsch. It is high time to state once and for all that the much disdained masses, despite their ‘academic backwardness’, often exhibit the soundest instincts and preferences. ([Citation1924] 1961, 64)

This idea of the elimination of the subjective by forms of popular spectacular entertainment—that is, eliminating a reliance on figures based on subjective emotional effects and embracing the colourful and the playful—also echoes Schlemmer’s ideas on kitsch, which, concurrently with the advent of the neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) in the 1920s, describe the aesthetic experience of the mass audience more positively. Works like Schlemmer’s The Figural Cabinet I (Citation1922b) and Triadic Ballet, which premiered in Stuttgart in September 1922 and Bauhaus student Alexander Schawinsky’s(1904–1979) Circus (Citation1924) embraced the “true-kitsch” of aesthetic conventions of clowning, the circus and sideshows by including exaggerated lines and bright colours within their avant-garde scenography and costuming design. This provided social and cultural reference points of pleasure and play for theatre-goers and gallery-visitors that encouraged audience reception, rather than rejection, of these early modernist works.

These exaggerated lines and bright colours are also manifest in Kandinsky’s works of the early 1920s, showing traces of possible discussions with Schlemmer about Kandinsky’s own long-held views on the slippery, seductive nature of kitsch and its relationship to high art. On 5 June 1913, for example, Kandinsky wrote to Franz Marc (1880–1916) to suggest that they collaborate to produce old signboards and advertising displays such as those found at the Oktoberfest fairgrounds that include paintings on concession stands. Kandinsky wished to explore the “tensions between avant-garde and advertising art” (Simmons Citation1999, 125) and stated that he intended, through the project, “to go to the border of kitsch (or as many will think, across the border)” (in Obler Citation2006, 86). The 1913 project with Marc never came to fruition, but Kandinsky’s 1920s paintings at the Bauhaus, such as White Zig Zags (Citation1922), Blue Painting (Citation1924), and Yellow-Red-Blue (Citation1925) form a dialogue with the colours, lines and forms of Schlemmer’s The Figural Cabinet I (Citation1922b) andcostume designs of theTriadic Ballet. Schlemmer’s changing views on kitsch must therefore also be placed within the context of the Bauhaus collective’s willingness to embrace vernacular art forms and styles to encourage critical thinking and to create new aesthetics.

Conclusion and considerations

This article provides the context for the annotated translation of Schlemmer’s previously unpublished manuscript of kitsch which is provided in Appendix 1. It has sought to situate Schlemmer’s manuscript within discussions that were being held by art historians, educators, artists and intellectuals in Germany and Austria at the turn of the twentieth century about what constituted kitsch and its existence in art and the applied arts, and its expression of German bourgeois society. At the beginning of the twentieth century, groups like the DW pushed to educate the German bourgeoisie about the correct, tasteful, German way to live and sought to guide the consumption of art and applied arts and create new tastes that reflected a new, industrialised Germany that valued craftsmanship as much as it valued high art. There was, however, no place for commercialised kitsch in this tasteful new Germany, and while there were disagreements about what constituted good taste, guidelines about what constituted “kitsch”, such as those produced by Pazaurek, were generally agreed upon. Despite these discussions, however, satirists like Wedekind decried the bourgeoisie itself as “kitsch”, while avant-gardists like Schlemmer eschewed older styles of art as “kitsch” and no longer relevant, especially during the war. Following the First World War, younger artists used the term “kitsch” to mean dated as well as bad taste, but the avant-garde appears to have re-thought the value of certain forms of popular entertainment. This included an examination of the circus, market fairs and vaudeville, from which the Bauhaus and the Constructivists extracted and adapted principles of movement, spectacle and play alongside costuming and scenographic conventions to form wholly new works that would shape the future of theatre and art.

There is much scope, therefore, for scholars to consider the role that Schlemmer’s ideas about kitsch may have played at the Bauhaus across all of its disciplines, not just within theatre. This includes Moholy-Nagy’s Constructions in Enamel (Citation1923), which challenged ideas about high art and commercial reproduction, as well as his explorations into painting in a photographic age. There is also scope for scholars to trace the influence of Schlemmer’s ideas on writings about kitsch after 1922. Schlemmer’s manuscript and his reconfiguration of the idea of kitsch as something of value, for instance, points to the continuation of the breakdown of traditional distinctions between high and low art that groups like the DW and the Dürerbund were striving to reinforce. Schlemmer appears to be making an argument in favour of authentic, “true” common pleasures and his designs, along with those of his peers at the Bauhaus, sought to bring the essence of these pleasures into the rarefied realm of high art. It is hoped, therefore, that this article and the translated manuscript provided in Appendix 1 will prompt new discussions of kitsch to inspire artists and designers to continue to work with an aesthetic that has remained much maligned and yet highly popular for more than 100 years.

Appendix 1. Oskar Schlemmer, True Kitsch Is Beautiful (unpublished manuscript, 1922a): An Annotated Translation

What Is Kitsch?

From the perspective of the genius, kitsch must be everything that does not align with his concept of what constitutes art because, when the genius looks out from his lofty ivory tower, everything he sees that is not art is inconsequential, weak, of little worth, has a “narrow horizon”, etc.

Yet the genius is not completely infallible and there are no guarantees that he, in an unguarded moment, might not create something kitsch. But he’ll destroy it, because his vanity will prevent it from seeing the light of day.Footnote4

Oscar Wilde paradoxically claimed that “bad art stems from genuine feelings”.Footnote5

Certainly, a true „.kitsch-maker„.Footnote6 is also ruled by genuine feelings; he does the best he can and, just like the great artist, does it with complete conviction in the righteousness and importance of his work.

This true kitsch, like that which one encounters among „.travelling folk„.Footnote7 at sideshows and at the circus,Footnote8 can be touchingly beautiful and it would be a crime were the Arts and Crafts evangelistsFootnote9 to eradicate it. This kind of kitsch has a beauty in and of itself as an intrinsic part of the world’s rich tapestry.Footnote10

Kitsch is a thoroughly relative matter.

This matter becomes disconcerting and uncomfortable in the event of an “unfair competition”; that is, if deliberate dishonesty rules the maker’s actions—such as when objects are made due to a pure craving for attention or for commercialism—and the motives behind their production are not critiqued. Kitsch of this kind is, with few exceptions, apparent on the majority of movie posters, which gives rise to a particularly hideous affect when compared with the films themselves, that is, the original photography.

Kitsch is everything that springs from an unjustified, undeserved craving for attention and from false ornamentation. Every artist strives to please; he asks himself only whether it be justly, i.e. through artistic means, or unjustly, i.e. tastelessly and vulgarly.

The Director of the State Museum of Stuttgart, Professor Pazaurek, has curated a unique permanent exhibition, entitled “Aberrations in Taste”, of objects that are commonly considered kitsch. The exhibition only includes applied arts and crafts, but because kitsch can apply broadly to any object, from all realms of art—and realms of life!—then it could be expected and construed that kitsch is evident in the visual arts, painting, and plastic architecture, in the realm of the theatre, as well as music, poetry and last but not least, life! as it is categorized in the museum! The exhibition thus has the purpose of educating the public about the types and categories of kitsch through the objects on display.

There is a specific section in the Stuttgart Museum, however, namely War KitschFootnote11: you blow your nose on the Kaiser and the military leaders of the World WarFootnote12; or you can ash your cigar into an ashtray made from grenade shrapnel that shredded a human corpseFootnote13 … these two examples are enough to highlight the never-ending list of mass-produced objects, and callousness, that comprised this most tragic chapter in the realm of kitsch.

More harmless, if no less vile,Footnote14 however, is industrialisation that reduces the great, the perfectly formed, and the aesthetically beautiful into tiny, cute bric-a-brac, such as a metallic, electroformed death mask of Beethoven, a paper weight shaped like the Milan CathedralFootnote15 or light bulbs shaped like grapes! These tasteless, mass-produced articles sold by the more unscrupulous merchants populate the dwellings of workers and the bourgeoisie. There, through constant contact,Footnote16 the objects bore themselves into their owners’ consciousness and produce the gaudy ethos that is so characteristic of our time and of those specific social classes.Footnote17

There is no doubt that the joy in these objects is genuine; genuine like the joy that BlacksFootnote18 have in everything that shines and glitters, genuine like the joy that a child has in everything that shines and glitters; genuine joy like that of a child who has woven these objects through its dreams of paradise. Perhaps people need this glitz, even if it’s spurious; perhaps people need something they regard as beautiful that is cheap, and so they decorate their homes with objects they are proffered, like those they’ve seen at their neighbour’s, or at the department store.

The DürerhaüserFootnote19 were founded in in opposition to the shoddy goods of department stores. These workshops, the refuge of the Jugendbewegung, brought to bear a Protestant form of applied arts that flirted with the medieval. This was a protest against the type of kitsch in the domestic sphere and in dress that had sprung from the milieu.Footnote20 The so-called “Jugendbewegung” had a purifying effect it lacked an expression of our time, the modern world, and modern attitude to life.

One could surmise that the ‘Bauhauses’Footnote21 were founded in opposition to the “Dürerhaüser”, specifically the Bauhaus itself, a pioneer in the fields of contemporary buildings and dwellings and which leads modern art and living. A convention grounded in reason and discernment from which no false tone can sound will result from this objectivity, from which directions for collectivism, standardisation, and categorisation will guideFootnote22 the style of dwellings and, hopefully also, lifestyle of the next generation.

If, so to speak, the origin of an object is established, then any grotesque deformities/excesses it may have that are considered kitsch are obvious. This, however, can also be articulated from the perspective of high culture when considering the visual arts, theatre, music, and poetry: works that do not correspond to the unconditional requirements of the old or new ideals may also seem dubious.

The contested realms of taste, truth, beauty, and perfection lie between the pure, unequivocal expressions of kitsch and the pure, unequivocal heights art and indeed there is not the room here to demarcate these realms precisely, if it is even possible to do so.

In any case, back to kitsch: to its most mollifying, satisfying form in which it does not constantly, daily surround us; rather, where we revel in it for a short time, such as at the carnival. Here I mean the kitsch of a town’s JahrmarktFootnote23 with its sideshows and fairgrounds, and of the circus. It is here, where one encounters the entire range of folk cultureFootnote24 expressions, where the travelling folk stage their grandiose “Griechenfest”,*Footnote25 that you’re immediately overcome by that feeling of it. One goes for pleasure, if not to immerse oneself, and takes part in the whole colourful world of carousels, shooting galleries, and collections of curiosities. This style enjoys an undisputed right to exist and it would be criminal to let the Arts and Crafts evangelists loose on it to carry out their refinements on objects that are simply unsuitable for that purpose. This is kitsch’s true home and it should bloom and flourish here as the most colourful, glittering,Footnote26 artificial blossom in the colourfulFootnote27 tapestry of our world.

The end.

* Ecstatic, Bacchanalian, rich and decadent; in this sense it’s an excessive realm in which one experiences a quasi-ecstasy, in which everything is opulent and lush, in which everything is extravagant. It’s about a loss of control in every respect in this time and a longing for an ancient world. For example, like the feeling you get at Oktoberfest.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Emily Brayshaw

Emily Brayshaw is an Honorary Research Fellow at the University of Technology Sydney. Her research interests include fashion, textile and costume designs in Europe and America between 1890 and 1930, specialising in the social, cultural and economic impacts of fashion, dress, military uniforms, and performance costume during World War I. Emily’s other research interests including the aesthetics of kitsch, and fashion and crafting during times of crisis. Emily also works as a costume designer in Sydney, and has an active practice as a viola player, visible mender and knitter.

Notes

1. The Dürerbund was founded in 1902 by Avenarius and the art historian Paul Schumann and named after the medieval German artist Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528). It was an organisation of writers and artists that became a leading cultural organisation in Germany and aimed to direct the aesthetic education of the masses in the early twentieth century. It was highly influential in the intellectual life of the German, Austrian and Swiss bourgeoisie and had close connections to the DW (Weikop Citation2008).

2. The Deutscher Werkbund (the German Association of Craftsmen) and the Dürerbund, the leading cultural organisation in Germany in the early twentieth century had close ties and shared similar aims of developing and guiding public taste.

3. According to Christopher Long (Citation2009), Ornament and Crime was first published in 1910, rather than 1908.

4. This likely refers to Avenarius’s idea that even a young genius, without the benefits of education to shape his tastes, can produce something kitsch (Avenarius Citation1920, 2007, 89). Schlemmer furthers this idea, however, noting that the artist will destroy it once he recognises that it is kitsch.

5. Schlemmer is referring to Wilde’s statement from his 1891 work The Critic as Artist (Upon the Importance of Doing Nothing and Discussing Everything) that “all bad poetry springs from genuine feeling. To be natural is to be obvious, and to be obvious is to be inartistic” (Wilde Citation1891, 2007, 98).

6. Schlemmer is intimating with his statement that creating “kitsch” can be a “truthful practice” that the craftsman can engage in. There is, therefore, more than one “truth” at play here: “truth”, like decadence, within art and aesthetics can be subjective, and kitsch, like Beauty, is in the eye of the beholder.

7. Here Schlemmer may be referring to itinerant carnival folk and circus workers, including the Roma, a nomadic people who entered Europe from the Punjab region of northern India between the eighth and tenth centuries CE, many of whom traditionally worked as craftsmen, blacksmiths, cobblers, tinsmiths, horse dealers and toolmakers. Others were performers such as musicians, circus-animal trainers and dancers (USHMM Citationn.d.).

8. The type of kitsch Schlemmer refers to here would have extended to the caravans of the Roma people. The exteriors of these caravans were often decorated with a blend of folk and baroque motifs in rich colours, while the interiors blended these rich colours and motifs with soft textiles, producing what, to modernists, would have appeared a quaint, cluttered nineteenth-century effect.

9. The Arts and Crafts Movement drew on folk styles of decoration, and its artists, like A. W. N. Pugin (1812–1852) and William Morris (1834–1896), advocated truthful material, structure and function. Schlemmer, however, is likely referring to second-generation Arts and Crafts practitioners such as William Richard Lethaby (1857–1931), who sought to break down the academic divisions between design and production. Lethaby’s work was adopted and adapted Muthesius.

10. The translation here is idiomatic, as Schlemmer actually uses the expression “bunten Teppich”, which literally translates as “colourful carpet”. In addition, the term bunt can have positive as well as negative connotations in German. It can mean that something is pleasant, gaily coloured and festive, but as an adjective it can also mean an object comprising a gaudy, tasteless riot of colours. The expression “Treib’s nicht zu bunt”, for example, literally means, “Don’t make it too colourful”, but is used to mean “Don’t behave too exaggeratedly or over the top”. Schlemmer, therefore, is applying the phrase to tasteful objects, works of art and cultural events, and to those which would be typically described as bad taste and/or “kitsch”.

11. The category of War Kitsch was first designated by Avenarius in July 1916. In his essay “Kriegs-Kitsch”, Avenarius notes that, despite the art that is developing in response to the experiences of the war, the public is asking for goods related to the war (Kriegsartikel). The businessman is driving this desire for such kitsch and, as Avenarius notes, the artist wants to survive, and so he is making banal, formulaic superficial art that is “easy to understand and sentimental” (Avenarius Citation1916, 66).

12. Presumably Schlemmer is referring to handkerchiefs with images of the Kaiser on them that were manufactured at the start of the First World War. Such handkerchiefs were made from cotton and often featured images of German ships, airships, geographical locations and the German flag. One extant example features the patriotic slogan, “Wir wollen und müssen siegen!” (We want and must have victory!) above an image of the Kaiser wearing his military regalia. War kitsch is related to what Pazaurek classified as “Hurrakitsch”, that is, items that that tapped into patriotic feelings (Citation1912, 350).

13. Saunders (Citation2000) refers to such items from the First World War as “Trench Art”, noting that they are “objectifications of the self, symbolizing grief, loss, and mourning … ; are poignantly associated with memory and landscape; and with issues of heritage, and museum displays which increasingly emphasize the common soldier’s experience of war. They are also associated with … tourism—particularly as regards their symbolic status as souvenirs” (45). Here Schlemmer, himself a veteran of the First World War, is bitterly critiquing the way in which the horrors of war are reduced to a souvenir, the kind of kitsch that Pazaurek categorised as Fremdenartikelkitsch (Foreign object kitsch), the kind of cheap trinkets that every aunt or cousin brings back for their relatives from their jaunt to the beach (Citation1912, 352).

14. Schlemmer uses the word verwerflich, which can also be translated as “reprehensible” “ignominious”, or “abject”. The term also literally means “disposable” and, in this context, encapsulates the idea of casting/throwing away. When juxtaposed with examples of War Kitsch in the previous paragraph, Schlemmer is also linking it to abjection, opining that the production and consumption of War Kitsch is a disgrace and that being forced to face objects of War Kitsch is inherently traumatic and repulsive.

15. The Gothic Milan Cathedral was the subject of acid criticism from Ruskin, who championed the Gothic Revival movement (Ruskin Citation1849, 45). Ruskin considered the Milan Cathedral in poor taste, but surely its tacky, industrially produced souvenir version is worse than something made by craftsmen.

16. Schlemmer uses the word Umgang, which also means “social intercourse”. This term enhances the sense of agency of an object that Schlemmer is referring to articulates the kitsch object’s active, rather than passive, effect on its owner and its environment.

17. Schlemmer is articulating notions about the consumption of kitsch within working class, petit bourgeois and bourgeois interiors, indicating that commodity capital has overtaken any notion of the aesthetics of good taste. This predates the Arcades project, which Walter Benjamin commenced writing in 1927 and included the notion that domestic interiors of the nineteenth century were furnished in “dreams” that were drawn from a range of historical styles. The notion also corresponds to Wedekind’s (Citation1917) articulation of kitsch as the Zeitgeist of modernity.

18. Schlemmer’s statement corresponds with early twentieth-century notions of racial hierarchy in Europe and Western nations that designated people of colour as unevolved, uncivilized and childlike. Schlemmer’s statement echoes the racial views espoused by Loos in his manifesto, Ornament and Crime (Citation1910). He uses the word “Neger”, which is highly offensive in contemporary German.

19. Schlemmer is presumably referring here to the plural of “Dürerbundhaus”.

20. The Jugendbewegung referred to the cultural and educational movement founded in 1896 in Berlin that saw young people escaping the industrialised German cities and turning to groups that embraced rural, pre-industrial ways of life and older culturally diverse traditions (Stambolis Citation2011). Avenarius promoted the idea that Dürer’s art “could provide Germany’s young artists with spiritual guidance” and openly attacked the “conventions of Wilhelminian culture” (Weikop Citation2008, 79–80). Schlemmer here is noting that Jugendbewegung members were rebelling against the tastes, dress and lifestyles of their conservative bourgeois consumerist parents.

21. It is unclear within the original document why Schlemmer uses the plural form of Bauhaus here. There was, however, a general psychological motivation towards construction (Bauen) in Germany following the destruction wrought by the First World War, which was “clearly evident in the manifestoes of postwar groups such as the Novembergruppe, the Arbeitsrat für Kunst, the Dresden Secession Gruppe 1919, and of course, the Bauhaus” (Weikop Citation2008, 90). Schlemmer may be referring quite literally, therefore, to these groups, or “houses” that were working in the more expressionist styles, compared with the aesthetics of the pre-War Dürerbund.

22. Schlemmer uses the word bestimmen, which also means to determine, or to design.

23. The tradition of Jahrmarkt carnivals in many German towns dates back to the early Middle Ages and is often aligned with the feast days of the Church. The carnivals give local people, merchants and travellers the opportunity to sell and display their wares and to enjoy amusements and entertainment. Jahrmarkt is often used as a synonym for Volksfest. The Jahrmarkt is the type of fair to which Wedekind’s “Peter” is referring when he states that he would rather starve than sell his art at a fair.

24. Schlemmer uses the word Volkstümliche, meaning folk culture in opposition to high culture.

25. At this point in the manuscript, Schlemmer uses a footnote for the first time to discuss his term Griechenfest. This term literally means “Greek festival”, but Schlemmer uses it to refer to the Bacchanalian mood often present at folk festivals and carnivals like Oktoberfest, where the beer flows freely.

26. Here he uses the word schillerndest, which means glittering, but also has connotations of the word “glamour”.

27. Schlemmer again here uses the phrase “bunten Teppich”.

References

- Avenarius, F. 1916. “Kriegs-Kitsch.” Deutsche Wille: Des Kunstwarts, 1916 29 (4): 65–15. Nr. 2.

- Avenarius, F. 1920 2007. “Kitsch.” In Kitsch: Texte Und Theorien [Kitsch: Texts and theories]. edited by U. Dettmar and T. Küpper, 98–99. Stuttgart: Reclam.

- Benjamin, W. 1935 1969. “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” In Illuminations, edited by H. Arendt, translated by Harry Zohn. 217–252. New York: Schocken Books.

- Blackbourn, D., and G. Eley. 1984. The Peculiarities of German History: Bourgeois Society and Politics in Nineteenth-Century Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Calinescu, M. 1987. Five Faces of Modernity: Modernism, Avant-Garde, Decadence, Kitsch, Postmodernism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Crown, C., and C. Rivers, eds. 2013. The New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture. Vol. 23. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Fischer, T. 1908. Die Veredelung Der Gerwerblichen Arbeit Im Zusammenwirken Von Kunst, Industrie Und Handwerk. [The refinement of industrial work in conjunction with art, industry and craft]. Leipzig: R. Voigtlaenders Verlag.

- Garebian, K. 2011. The Making of Cabaret. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Glytzouris, A. 2008. “On the Emergence of European Avant-Garde Theatre.” Theatre History Studies 28 (28): 131–146. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/ths.2008.0004.

- Jarzombek, M. 1994. “The Kunstgewerbe, the Werkbund, and the Aesthetics of Culture in the Wilhelmine Period.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 53 (1): 7–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/990806.

- Kandinsky, W. 1922. White Zig Zags. Venice: Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna, Ca’ Pesaro.

- Kandinsky, W. 1924. Blue Painting. New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

- Kandinsky, W. 1925. Yellow-Red-Blue. Venice: Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna, Ca’ Pesaro.

- Karpfen, F. 1925. Der Kitsch: Eine Studie Über Die Entartung Der Kunst. [Kitsch: A study into the degeneration of art].. Hamburg: Weltbund Verlag.

- Kliche, D. 2010. “Kitsch.” In Aesthetische Grundbegriffe: Band 3: Harmonie – Material, edited by K. Barck, M. Fontinus, D. Schlenstedt, B. Steinwachs, and F. Wolfzettel, 272–288. Stuttgart: J. B. Metzler.

- Koss, J. 2003. “Bauhaus Theatre of Human Dolls.” The Art Bulletin 85 (4): 724–745. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/3177367.

- Long, C. 2009. “The Origins and Context of Adolf Loos’s ‘Ornament and Crime’.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 68 (2): 200–223. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/jsah.2009.68.2.200.

- Loos, A. 1910 1970. “Ornament and Crime.” In Programs and Manifestoes on 20th Century Architecture, edited by U. Conrads. Translated by Lund Humphries. 19–24. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Mihăilescu, C.-A. 1997. “A Ritual at the Birth of Kitsch.” The Comparatist 21 (21): 49–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/com.1997.0010.

- Moholy Nagy, L. 1923. EM 2 (Telephone Picture). New York: MoMA

- Moholy-Nagy. 1924 1961. “Theatre, Circus, Variety.” In Theatre of the Bauhaus, edited by W. Gropius and A. S. Wensinger, 49–72. Translated by Arthur S. Wensinger. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

- Morris, W. 1898. Art and the Beauty of the Earth. London: Longmans and Longmans and Co.

- Obler, B. K., Intimate Collaborations: Kandinsky and Münter, Taeuber and Arp PhD diss., (University of California, Berkeley, 2006).

- Obler, B. K. 2014. Intimate Collaborations: Kandinsky and Münter, Arp and Taeuber. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Overy, P. 2006. “The Whole Bad Taste of Our Period”: Joseph Frank, Adolf Loos, and ‘Gschnas’.” Home Cultures 3 (3): 213–233. doi:https://doi.org/10.2752/174063106779090721.

- Pazaurek, G. 1912. Gute Und Schlechter Geschmack Im Kunstgewerbe. [Good and bad taste in the applied arts]. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlagsanstalt.

- Riegl, A. 1894. Volkskunst, Hausfleiss Und Hauseindustrie. [Folk Art, Domesticity and Cottage Industries]. Berlin: Georg Siemens.

- Ruskin, J. 1849. The Seven Lamps of Architecture. London: Smith, Elder and Co.

- Saunders, N. J. 2000. “Bodies of Metal, Shells of Memory: “Trench Art” and the Great War Re-cycled.” Journal of Material Culture 5 (1): 43–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/135918350000500103.

- Sayre, R., and Löwy, M. 2005. “Romanticism and Capitalism.” In A Companion to European Romanticism, edited by M. Ferber, 433–449, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Schawinsky, A. 1924. Circus, Zurich: The Xanti Schawinsky Estate, Karma International

- Schlemmer, O. 1918. Ein Hinweis [previously Zur Sache]. AOS Box 2, Mappe 1, 1918 Manuskripte: (Tagebuch und Briefe) AOS, 2016/1052, 1917. Archiv Oskar Schlemmer, Stuttgart.

- Schlemmer, O. 1922a. Der Wahre Kitsch ist Schön. AOS Box 2, Mappe 2 Manuskripte/Briefem 1919–1922, Archiv Oskar Schlemmer, Stuttgart.

- Schlemmer, O. 1922b. The Figural Cabinet I (Das figurale Kabinett), Joan and Lester Avnet Collection, MoMA, Manhattan.

- Schlemmer, O. 1924 1961. “Man and Art Figure.” In Theatre of the Bauhaus, edited by W. Gropius and A. S. Wensinger, 17–48. Translated by Arthur S. Wensinger. Middletown: Wesleyan University Press.

- Schwartz, F. J. 1996. The Werkbund: Design Theory and Mass Culture before the First World War. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Simm, F. X. 1917. Fliegende Blätter, 1917, 67, vol. 146 (6) Nr. 3728. Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg. Available at https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/fb146/0072

- Simmons, S. 1998. “Grimaces on the Walls: Anti-Bolshevist Posters and the Debate about Kitsch.” Design Issues 14 (2): 16–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1511849.

- Simmons, S. 1999. “Advertising Seizes Control of Life: Berlin Dada and the Power of Advertising.” Oxford Art Journal 22 (1): 119–146. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/oxartj/22.1.119.

- Simmons, S. 2000. “August Macke’s Shoppers: Commodity Aesthetics and the Inexhaustible Will of Kitsch.” Zeitschrift Für Kunstgeschichte 63 (1): 47–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1587426.

- Stambolis, B. 2011. “Jugendbewegung.” Europäische Geschichte Online (EGO), 16 March 2011. http://www.ieg-ego.eu/stambolisb-2011-de

- Thompson, E. P. 2011. William Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary. Oakland: PM Press.

- USHMM (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum). n.d. “Roma (Gypsies) in Prewar Europe.” The Holocaust Encyclopedia. Accessed 10 November 2020. https://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10005395

- Veblen, T. 1899. The Theory of the Leisure Class. New York: Macmillan.

- Wedekind, F. 1891 1969. Spring Awakening. Translated by Tom Osborn. London: Alma Classics.

- Wedekind, F. 1895 1918. Erdgeist (Earth Spirit): A Tragedy in Four Acts. Translated by Samuel A. Eliot Jr. New York: Boni and Liveright.

- Wedekind, F. 1904 1918. Pandora’s Box: A Tragedy in Three Acts. Translated by Samuel A. Eliot Jr. New York: Boni and Liveright.

- Wedekind, F. 1917. “Kitsch.” In Kitsch: Texte Und Theorien, [Kitsch: Texts and theories], edited by U. Dettmar and T. Küpper, 41–45. Stuttgart: Reclam.

- Weikop, C. 2008. “The Arts and Crafts Education of the Brücke: Expressions of Craft and Creativity.” The Journal of Modern Craft 1 (1): 77–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.2752/174967708783389823.

- Wilde, O. 1891 2007. The Critic as Artist (Upon the Importance of Doing Nothing and Discussing Everything). New York: Mondial.

- Wilhelm, I. I. 1901. “True Art.” Translated by Angela A. Kurtz. German History in Documents and Images. Available at http://germanhistorydocs.ghi-dc.org/pdf/eng/301_Wilhelm%20II_True_Art_50.pdf