ABSTRACT

This article shows how contemporary artistic practice seeks to re-evaluate, re-interpret and re-imagine (historical) Arctic exploration narratives that have generally been considered gendered and dominated by men. It particularly examines the work of contemporary Norwegian artist Tonje Bøe Birkeland, whose entire practice emerges from embodying and staging imagined turn of the century woman explorers. One of Birkeland’s explorers travels to the Arctic and the circumpolar North and explicitly references persisting narratives deriving from the so-called heroic era of polar exploration. In order to change these narratives, I argue, Birkeland employs two feminist strategies: firstly, by storytelling and speculative fabulation (Haraway); secondly, by simultaneously complying with and disrupting re-occurring Arctic motifs and representations. Photography, travel writing and found objects are hereby her primary artistic mediums and “accomplices” in fulfilling these strategies, carefully orchestrated in a photobook in order to establish her story and view on the Arctic world. As a result, Birkeland not only reveals which stories about the Arctic are missing and could have been told. She also asks us to imagine how our relationship to the Arctic could have been shaped differently and how, through this process, it is possible to influence a future narrative of a (still) gendered Arctic.

Introduction

When considering the polar regions as a gendered space, a direct reference is made to the so-called heroic age of exploration during the period of high Imperialism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. More concretely, the polar regions have been considered a testing ground for white male European and North American explorers, scientists and adventurers alike (Reeploeg Citation2019, 6; Hansson and Ryall Citation2017; Aarekol Citation2016; Kjeldaas Citation2015; Glasberg Citation2012a; Bloom Citation2010; Berg Citation2006; Glasberg Citation2002; Bloom Citation1993). Not only were women generally excluded from these explorative endeavours, thus turning these into male-only homosocial conventions. But also, the frozen terrain itself (or the prospect of reaching it) acted as a mould or device in the rite of passage for becoming a fearless heroic explorer in which a sort of heroic self-fashioning was taking place (Thompson Citation2011, 174). To have the courage and strength to discover and conquest the supposedly uninhabited, frozen and dangerous place on earth was seen as an act of manliness deserving heroic merit. Lisa Bloom writes:

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, polar exploration narratives played a prominent part in defining the social construction of masculinity and legitimized the exclusion of women from many public domains of discourse. As all-male activities, the explorations symbolically enacted the men’s own battle to become men. The difficulty of life in desolate and freezing regions provided the ideal mythic site where men could show themselves as heroes capable of superhuman feats. (Bloom Citation1993, 6)

While motivations for the polar expeditions in which these men participated varied, many scholars have pointed out that these male endeavours frequently combined commercial, national and imperialist motives (Ryall Citation2019, 179; Stam Citation2019, 79–80; Thompson Citation2011, 173–179; Bloom Citation1993; Arlov Citation1989).Footnote1 One can thus infer that more recent academic research related to the history of the Arctic and polar exploration pays attention to the lack of agency and representation by women, while there is also a focus on the missing voices of indigenous Arctic peoples and nonhuman actors.Footnote2 All point out that primary agency was generally attributed to selected (non-indigenous) men who at the same time often acted as representatives of larger commercial or national entities, and were thus not only driven by obtaining scientific knowledge but also by prospects of territorial ownership and securement of resources, often in the wake of nation-building processes. The polar regions were treated as terra nullius, or “no man’s land”, a blank space just waiting to be examined, measured, mapped, extracted and/or territorialized.Footnote3 This supposed blankness, in combination with general inaccessibility and geographical remoteness, was also an important factor in treating the polar regions—especially the Arctic—as spaces open for speculation and fictionalization, which the long history of Arctic myth-making processes reflects (Frank Citation2015; McGhee Citation2007, 20–33).Footnote4 As Lund and Berg have shown in the Norwegian context, these myth-making processes were still at play and consciously used in the period of heroic polar exploration, despite, at the onset of modernity, manly endeavours to strive for scientific and objectivist truths. In fact, these processes were an essential element in constructing the modern heroic image of the white male polar explorer and in which paradoxically enough also photography, as the supposed truth-bearing medium, played an essential role (Berg and Lund Citation2011, 23).

In her artistic practice, contemporary Norwegian artist Tonje Bøe Birkeland (born 1985) Birkeland Citation1985) refers to, plays with and re-evaluates these narratives and fictionalizing processes to disclose women’s lack of representation in historical polar narratives. Birkeland does this by speculating which stories about the Arctic have not, but could have been told. She encourages us to reflect on who and what has shaped or still shapes the image of the Arctic and how it is possible to shape it differently. In an interview with the author Birkeland re-confirms: “One could say that I am imagining what could’ve been, what probably happened but was never retold. It is what we retell and how we tell it that shapes our shared, universal history” (Birkeland Citation2019).

I argue that Birkeland employs two feminist strategies to re-evaluate past and present representations of the Arctic: firstly through storytelling and speculative fabulation (Haraway Citation2016); secondly, by simultaneously complying with and disrupting Arctic motifs and representations and with it, male polar narratives. According to Foote and LeMenager “[…] storytelling is a narrative and argumentative strategy that provides adaptable points of view, ways of seeing the world that can be picked up, pieced apart, borrowed and bricolaged into modes of resistance and response” (Foote and LeMenager Citation2014; Blum Citation2019, 32). Storytelling and “modes of resistance and response” are thus closely entangled with one another, and are, as I will show, detectable in Tonje Bøe Birkeland’s practice. Photography, text and appropriated objects are hereby her primary artistic tools and “accomplices,” carefully orchestrated in order to establish her story and communicate that it is possible to imagine alternative views on the Arctic world.

The Characters and Character #I Aline Victoria Birkeland

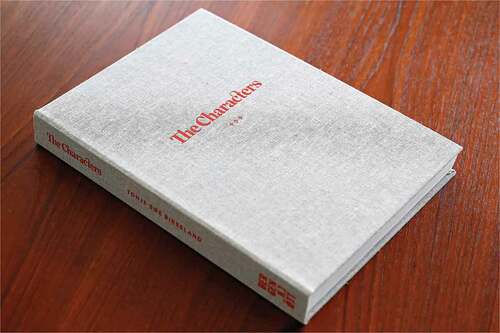

Tonje Bøe Birkeland’s artistic practice emerges exclusively from the construction of so-called Characters which personify imagined woman explorers during the heroic age of exploration. So far Birkeland has constructed six characters, each travelling to remote and/or mountainous regions of the world: Northern Norway/Svalbard/the Arctic (Character #I, Aline Victoria Birkeland), Mongolia (Character #II, Tuva Tengel), Orkney Islands/New York (Character #III, Luelle Magdalon Lumiére), Greenland (Character #IV, Anna Aurora Astrup), Bhutan (Character #V, Bertha Bolette Boyd) and the Swiss Alps (Character #VI, Golette Grepp). The stories of the first four characters have been united in the photobook The Characters and present the viewer with a visual and textual narration of each woman’s explorative travels (Birkeland Citation2016). The accounts of three consecutive travels to Bhutan (2016, 2017, 2018) by Character #V have been published as a photobook in 2021 (Birkeland Citation1985). Character #VI has so far only become visualized through a public art project at a primary school in Hamar, Norway.

Character #I Aline Victoria Birkeland is the woman explorer I closely examine in this paper. This character travels to regions that are most thoroughly bound to the Norwegian territory and polar history (Bergen, Tromsø, Finnmark, Svalbard), where not only I situate my own research but which is also the artist’s experiential space.Footnote5 Although polar exploration was an international (meaning: Euro-American) enterprise, here specific references to Norwegian polar history abound, such as by referral to Norway’s biggest declared polar heroes Fridtjof Nansen and Roald Amundsen.Footnote6 However, Tonje Bøe Birkeland’s practice not only references the carefully constructed visual and textual self-representations of these (and other) male polar heroes, she also plays with a wide range of visual and literary genres and motifs that disclose the Arctic as a gendered space. The photobook The Characters hereby becomes my main object of analysis, since it is here where Tonje Bøe Birkeland most comprehensively weaves together text, photography and objects to tell the story of her characters, including Character #I (). Significantly, the photobook is the artistic medium that prominently lays bare that these characters are fabulations on the one hand, yet quite “real” on the other: it is namely the artist herself who embodies each of them, dresses up in the period’s attire she refers to, physically travels to all the places recounted and “documents” them in the book.Footnote7

Storytelling and speculative fabulation to change the story

Tonje Bøe Birkeland’s Characters, I argue, are an artistic materialization of Donna Haraway’s invocation to use storytelling and speculative fabulation as feminist strategies to re-think, re-evaluate and, ultimately, change the story. That is: what and how the past was written, how to shape the present, as well as what is to come. For Haraway, the String Figure is a metaphor for “worlding” and “storying” and which, through the use of the acronym SF, opens up for practicing different forms of thinking-with, becoming-with and entangling-with for changing the story. Here SF not only stands for “String Figure” but also its entangled threads: Speculative Fabulation, Science Fact, Science Fiction or So Far. Like in the String Figure game, different threads entangle and intersect, create patterns, assemblies and relations—a sympoeisis in which (feminist) world-making takes place across myriad temporalities, spatialities and entities. Thus, according to Haraway, storytelling is a so-called “SF” or “String Figure” thread and an essential practice: “[…] one more SF thread is crucial to the practice of thinking, which must be thinking-with: storytelling. It matters what thoughts think thoughts; it matters what stories tell stories.” (Haraway Citation2016, 39).

Although Birkeland does not explicitly refer to the current climate crisis (which however knowingly dramatically affects the space in which Birkeland’s first character is set) as Haraway does in relation to storytelling practices to “stay with the trouble”, I term this approach relevant in showing that Birkeland’s fabulated characters are a feminist strategy to “think-with” and that it “matters what stories tell stories” to influence how we act in the future. Birkeland’s character can be seen as a “String Figure” in which different temporalities and spatialities are at play and different artistic mediums, disciplines and genres interweave (photography, text, appropriated objects, staged photography, travel writing, photobook, visual art, literature, science). Through speculative fabulation, Birkeland’s work becomes what I call, in reference to Haraway, a “String Figure story” that actively enters into Arctic discourses and seeks to unravel how records of heroic polar narratives and representations of the Arctic lack women’s voices and whose assymetry is still reproduced today.Footnote8

Shifting perspectives

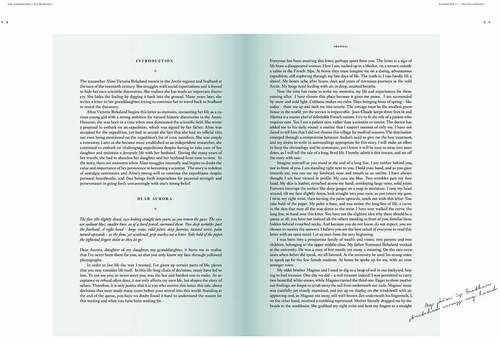

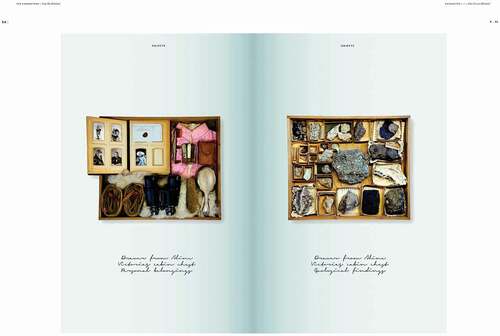

The structural setup for telling the story of Character #I, similar to the other characters in the photobook, is the following: a marbled cover page stating full name, birth/death date and a short characteristic description of the character (Character #I, Aline Victoria Birkeland (1870–1952) The Unknown Adventurer); a “JOURNAL” section containing a short narrator’s text that introduces the character followed by the character’s first-person narrative in the form of an autobiographical letter; a section with eighteen photographic colour plates “documenting” the character’s explorative travels in and near the Arctic; an “OBJECTS” section with photographic reproductions of personal objects and findings that supposedly belonged to the character. Altogether, reminiscent of a chapter, the different elements form a unified body of work separate from other characters’ stories in the book. An epilogue entitled A Curious Collection of Endnotes & images provides the reader with different background material from all of Tonje Bøe Birkeland’s travels/characters, including “behind the scenes” thumbnail photographs, small anecdotes, written reflections by collaborators and the artist herself, as well as a GPS tracking map from her trip to Greenland related to Character #IV.

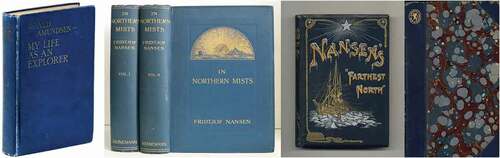

Within this structural setup the contemporary viewer/reader becomes entangled in a (life) story that is marked by constantly shifting spatial and temporal perspectives. Already the photobook’s design and layout leads the reader/viewer through different time periods: elaborate linen cloth-binding, embossed book title, marbled front- and endpapers and a serif typeface formally refer to nineteenth and early twentieth century published literature in general and travelogues in particular. The JOURNAL and OBJECTS sections appear as if they were the facsimile of an already published travelogue: text and photographs are printed on faded light-blue pages which are in turn “inserted” into the larger cream-coloured pages of the photobook (). That way the book mimics historical (polar) travelogues, examples of which are Roald Amundsen’s My Life as an Explorer (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1927) and Nordvestpassagen Beretning Om Gjøa-Ekspeditionen 1903–1907 (Kristiania: Aschehoug 1907 and Kristiania: Aschehoug 1908) Fridtjof Nansen’s In Northern Mists (London: William Heinemann, 1911), Farthest North (Westminster: Archibald Constable and Company, 1897) and various versions of Eskimo Life (1891–1893) (). On the other hand, characteristics such as the photobook’s size (considerably larger than historical travelogues with its 31.5 × 22.5 cm), crisp and almost full-spread colour photographs, and paper (Munken Lynx, an uncoated paper with a smooth surface and high colour saturation, which has seen popularity among contemporary photobooks) firmly indicate that the book belongs to the expanding artistic genre of the—often self-published and limited edition—photobook.Footnote9

Speculative travel writing and discursive pressures

These formal qualities establish an introductory reference to already published exploration narratives, like a prelude to the written and visual work which then thoroughly moves the reader/viewer through the story. The letter, which the character addresses to her granddaughter—and thus to a generation found among the contemporary reader—is a supposed primary source to disseminate the character’s biographical information: family background (upper middle-class, a supporting father, a mother constrained by women’s/girls’ societal expectations), hometown (Bergen, Norway), geographical locations of her travels (Tromsø, Finnmark, Svalbard/Grumant, Belkovsky Islands, Severnaya Zemlya), research areas (geology/glaciology), scientific discoveries (crystallization processes), family situation (married to a member of her first expedition, a daughter she has an alienated relationship with, the granddaughter the letter is addressed to) and most importantly, her expedition accounts. In many sections of the letter the reader is confronted with the character’s struggle with family expectations and as a woman scientist in a field dominated by men. Aline Victoria Birkeland’s letter is presumably written shortly before her death in 1952. At that time, the character hopes, a woman no longer needs to fear that her scientific discoveries are questioned or attributed to somebody else. She thus urges her granddaughter to “re-discover” and publish her scientific theory—based on an uncommon ice crystal she found but buried back into the ground during her final expedition. However, the letter ends with the statement “If you are not careful with how and where the finding is presented, it can easily disperse into the scientific discovery of your contemporaries” (Birkeland Citation2016) which expresses mistrust in that changes have taken place in the field and society at large.

The letter is a fictive text by a fictive character. It is a speculative fabulation on what it would have been like to follow a scientific career as a woman and publish her accounts at the time when explorers like Fridtjof Nansen, Roald Amundsen, Robert Falcon Scott, Robert E. Peary or Frederick Cook were taking centre stage in polar exploration narratives and scientific discourses. Mocking her text as an already published journal, Birkeland not only uses it as a device to tell the story of a woman explorer that could have existed. The text points to the discursive pressures women had to negotiate when publishing their travel writing at the time, as Sara Mills has noted (Mills Citation1991). Here especially the bourgeois woman—which Birkeland’s character is—met pressure both in terms of how to produce writing and how it was received. As also Griselda Pollock has argued in relation to visual art produced by women in the same period, women had to navigate the spaces and discourses they had access to and which consequently made visible which ones they were denied (Pollock Citation2003). The bourgeois women’s “spaces of femininity” were primarily the private and domestic spaces that in turn were connected with the attributes of (child)care, the emotional and the subjective. The public, professional and adventurous life was reserved for men, and their attributes associated with strength, rationality, objectivity and authority. As a result, visual and literary genres more open for the emotional and confessional became the cultural spaces women could often more easily navigate. In travel writing this meant that diary and letter formats were preferably used by women, especially if they were to step aside from masculine literary domains to guarantee publication—even if male critics still doubted the veracity of their acccounts (Thompson Citation2011, 184–5; Mills Citation1991, 5). Mary Wollstonecraft’s letters from Scandinavia (Wollstonecraft Citation1796/2004) and Mina Benson Hubbard’s accounts from Labrador in 1908 (Hubbard and Grace Citation2008) are striking examples, and especially Hubbard’s shows how they were discredited at the time: “When Mina returned south, she gave interviews and slide lectures and published articles about her expedition. Nevertheless, male opinion proved intransigent: one man, a clergyman who spoke with great authority, assured the public that she could not have done what she claimed in the time she had taken.” (Grace Citation2008, 5). Birkeland steps exactly in this discursive field with her character, even reinforces it by studding the letter with emotional and confessional elements in her struggle, such as conveyeing a sense of emotional loss following the decision to prioritize her work over family relationships (Birkeland Citation2016, 8) or admitting that her Arctic expeditions had a strenuous effect on her weakening body, now being rather a patient than a scientist or tourist (Birkeland Citation2016, 9). Such emotions and confessions indeed rarely appear in men’s polar exploration narratives as the example of Roald Amundsen’s first-person narrative My Life as an Explorer—also a memoir that looks back at a life of exploration—shows. Here strives are completely absent. Instead, Amundsen expresses what the core virtues of a polar explorer entail, namely (apart from physical) mental strength: “Man’s triumph over nature is not the victory of brute force, but it is the triumph of the mind.” (Amundsen Citation1927, 269). Accounts of weakness are completely absent, both in relation to past expeditions and in the aftermath. Amundsen and many of his male contemporaries were in fact extremely skilled in presenting themselves as the strong, rational, invincible explorers where bodily and mental weaknesses had no place. But, as many scholars have noted, one should be careful to take these at face-value and read them as truthful accounts and representations of the self (Gaupseth Citation2017, 33–35; Ryall Citation1989; Stam and Dean Citation2019, 49; Berg and Lund Citation2011; Thompson Citation2011, 27–28).

From a post-colonial and feminist perspective, Birkeland’s subjective position is exactly what makes her differ from the supposedly disembodied, objective accounts of her male counterparts. In her influential book Imperial Eyes, Mary-Louise Pratt has identified the “monarch-of-all-I-survey” scene, which she claims is one of the most gendered tropes in travel writing during the period of high Imperialism (Pratt Citation2008, 197–223). In this scene, there exists only one perspective, namely that of the (male) European traveller and explorer (and colonizer) whose perspective is the only one that is “objectively” valid. His is the one that determines how the virgin landscape (which Pratt equates with the other/female body) and its inhabitants are treated, which steps to take, and not least to map, name and ultimately possess it. In a similar vein, Donna Haraway coins the notion of the “god-trick” (Haraway Citation1988) in which she dismantles claims to objectivity that are traditionally asserted by the male, “disembodied” scientist in the quest for truth and knowledge. This claim, however, tricks us into believing that his view is the only legitimate and truthful one and that therefore the final (god-like) authority remains with him. Aline Victoria Birkeland’s account is the opposite of that. It is a counter-narrative in which no claims to objectivity are made, no places mapped, no stories of flag planting told, no condescending language towards others used—in spite of her striving for the same goals: knowledge and scientific truth, for “Science Facts”.

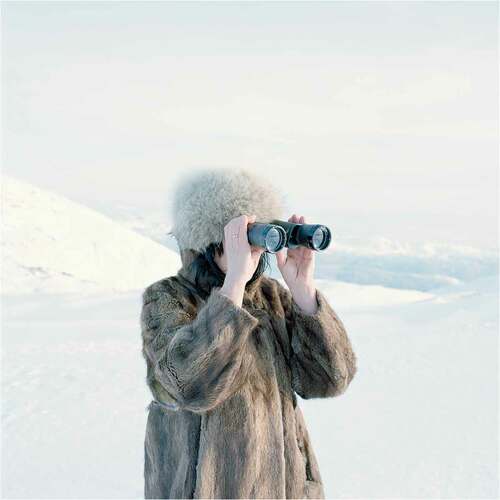

It matters what stories tell whose stories

While Tonje Bøe Birkeland’s written travel narrative is a speculative fabulation on the life, work and challenges of a female polar scientist around the 1900s, her photographs are a visual manifestation of inserting women into the story. They are an act of taking control to demonstrate that it “matters what stories tell stories,” to which I would add: it matters what stories tell whose stories. The photographs namely reveal that Birkeland is both photographer and model, narrator and protagonist, director and actress, author/producer and publisher. She is immersed in the (imagined) past and firmly anchored in the present. Out of the eighteen photographic plates, thirteen show the artist alias Aline Victoria Birkeland dressed up in historical attire within the Arctic/Nordic landscape, where any modern equipment is left outside the frame. In turn, Birkeland’s use of colour photography and accompanying captions reveal that all photographs were taken very recently (2008/2009). Information on size (varying from 90x90cm to 100x150cm) indicates that the photographs exist as three-dimensional aesthetic objects outside the book and show that they belong to a photographic tradition established at the end of the twentieth century when such large-scale photography made their entrance into the contemporary art circuit.Footnote10

Birkeland’s approach to photography and gender representation clearly connects to the deconstructive work such as Cindy Sherman’s staged photography. Not only are there parallels to the use of terminology borrowed from other cultural media, namely film and literary fiction, but also in their awareness of gender stereotypes disseminated through the media and how they feed back into the construction of new fictions and realities. But while Sherman slips into the role of various female stereotypes that primarily result in singular photographic artworks, Birkeland’s strategy is to comprehensively build up her character through different mediums and formats to make it as plausible as possible. In a sense it is her own “character”, or personality, that merges with her fictional character and becomes her alter ego. In the introduction to the photobook Birkeland writes: “The tale became my quest, conscience and concern. I would like to say it was my fantasy, dreams and desires, but as this hunt is my work, my artistic practice, it was far more real, physical and bothersome than a dream. One could say it bordered on an obsession.” (Birkeland Citation2016, 5). This merging of the fictional character with her own persona, bordering on obsessiveness, establishes parallels to the work of Sophie Calle, especially her book Double Game (Calle Citation1999). Here Calle plays out a fictional character from one of Paul Auster’s novels but also alters it by inserting her own personality and real actions back into the novel. This double game provides Calle both with the freedom to interpret but also invent the fictional character to her own ends. This playful approach to fiction and reality is also inherent in Birkeland’s character: on the one hand it is a fictive persona with a fictive biography and on the other it is the artist herself who makes the story come to life, shapes and physically experiences it—not least because she is a trained mountaineer familiar with and/or aware of the challenging territories she travels in.

The inaugural photograph in Birkeland’s photographic series, Character #I, Aline Victoria Birkeland, Plate #1 Aline 2009 (), is a striking example. It shows the character in close-up looking through binoculars, with a snow-covered landscape providing its backdrop. Although the viewer’s gaze directly confronts the character, she does not gaze back. Instead, her vision is directed at something or somebody that lies outside the picture frame and to which the viewer is denied access. This double-denial of the viewer’s gaze prevents the character from being objectified and therefore “figures as the subject of her own look,” as Griselda Pollock has pointed out in relation to art historical representations of the same motif (Pollock Citation2003, 109). Here Birkeland/the character controls her own story. But more than that: Birkeland places the character in a landscape that previously was “reserved” for the male explorer who determined what there was to be seen. Thus she both metaphorically invades his territory and literally replaces him. This switching of roles reveals the astute playfulness in Birkeland’s work in which she both changes the story and alters the conventional framing spaces (here: the Arctic landscape) Pollock refers to when problematizing the positioning of women within art historical discourse (Pollock Citation2003, 78–93).

Role reversals, complicity and disruption

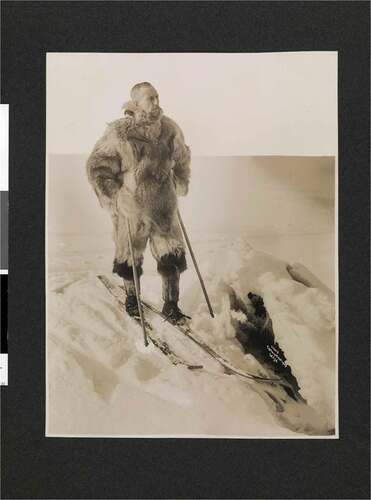

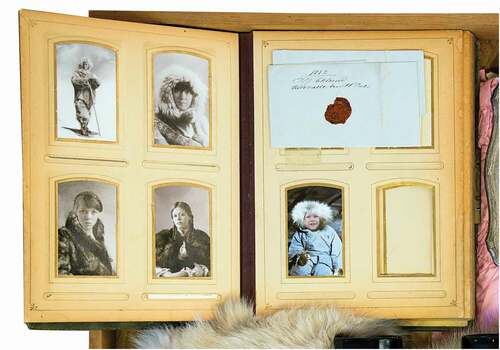

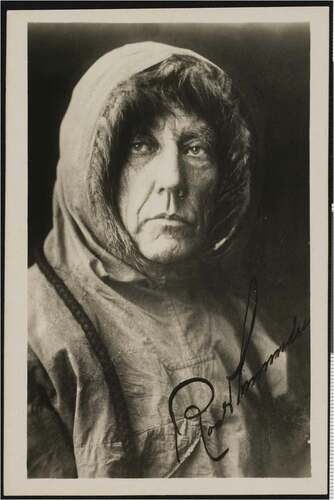

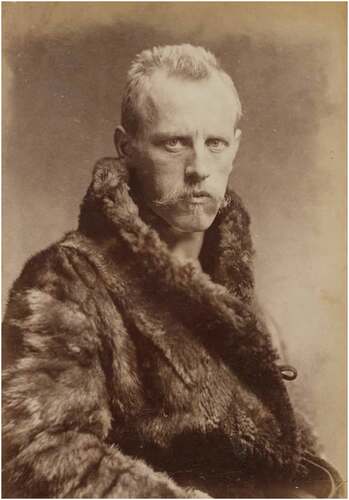

There exist several variations of the same motif—woman with binoculars—in the series (Plates #1, #11, #15, #16). This “impertinent” reversal of roles and framing spaces is detectable in all of Birkeland’s photographs. However, Birkeland’s strategic and most playful role reversal is found within the OBJECTS section of the book (). In the photographs “documenting” the character’s “Personal Belongings” there is a family photo album typically used in bourgeois households in the late nineteenth century (). In this yellowed album there are five cabinet-card sized photographs bearing portraits of the artist/character of which four re-enact iconic motifs found in historical photographic representations of the male polar hero: firstly the full-length portrait of the explorer fully dressed in fur and equipped with props such as a rod or weapon; secondly the half-length portrait clothed in a dark fur coat and thirdly the fur-hooded half-length portrait (embodied in two cards). Under the heading “Kabinettkorthelter” (Cabinet card heroes), Lund and Berg trace the genealogy of the first popular type to selected international explorers, especially the Americans Robert E. Peary and Frederick Cook. The Norwegian polar explorers Eivind Astrup and Roald Amundsen (), they claim, followed their footsteps (Berg and Lund Citation2011, 34–37).Footnote11 The other cabinet cards in the album reference two particular half-length portraits, one of Roald Amundsen (hooded) and one of Fridtjof Nansen (fur coat). Amundsen’s “hooded portrait” from 1920 shows him dressed in clothing “borrowed” from the indigenous populations of the Arctic, the Greenlandic anoraq (). Nansen’s portrait of 1897 in turn shows him dressed solely in a fur coat, returning a stern gaze at us (). Apart from that these cabinet cards were sought-after collectibles at the time, a phenomenon dubbed “cartomania” (Teukolsky Citation2015), Amundsen’s and Nansen’s portraits have additionally been endlessly reproduced in various contexts.Footnote12 They are thoroughly inscribed into a male-centered polar history.

Figure 5. Reproduction of OBJECTS section in Tonje Bøe Birkeland’s photobook The Characters. Courtesy the artist

Figure 6. Detail from OBJECTS section (“Personal Belongings”) in Tonje Bøe Birkeland’s photobook The Characters. Courtesy the artist

Figure 7. Portrett av Roald Amundsen i polarutstyr (Portrait of Roald Amundsen with polar equipment), cabinet card, Daniel Georg Nyblinn photo studio, 1899, Courtesy National Library of Norway, Oslo

Figure 8. Roald Amundsen Wearing a Fur Lined Parka, Nome, Alaska, 1920, photographed by Lomen Bros., Courtesy National Library of Norway, Oslo

Figure 9. Fridtjof Nansen, albumen print, photographed by Henry Van der Weyde, 1896. Courtesy National Portrait Gallery, London

Birkeland reproduced all three iconic types with great attention to detail. Not only in terms of motif (dress, props, pose and background) but also in terms of their original material properties (faded black-and-white photograph/albumen print, cabinet card format). The stern and condescending gazes that characterize the original portraits are also repeated in her re-enactments. Amongst the five cabinet-card sized photographs, the only “odd one out” is a small colour photograph of a friendly-looking child in a modern snow overall and fur hat, which appears to be a non-staged childhood photograph of the artist. It nevertheless presents her as a “snow and ice native”. In speculating herself into the same genealogical tree as the strong and heroic male polar explorers, Birkeland’s work becomes both homage and persiflage, complicit and disruptive. Her performative act inverts the gender role of the heroic Arctic explorer while she also, in this act of disruption, deconstructs the photographs as carefully staged, myth-making acts of self-representation.Footnote13

Staging of the self

Studio photography and its resulting collectible cabinet cards played a major role in disseminating the image of the invincible male polar explorer. But such constructed acts of self-representation were also rehearsed in the open, preferably snowy, landscape, and often closer to the explorer’s home. This was the case for Roald Amundsen’s infamous portrait on skis which the print media widely disseminated when the news arrived that he had reached the South Pole in 1911 (). The portrait had in fact been taken prior to departure at the shore of Amundsen’s villa Svartskog south of Oslo by the photographer Anders B. Wilse, just waiting to be disseminated together with the news (Berg and Lund Citation2011). Two of Birkeland’s photographs, Character #I, Aline Victoria Birkeland, Plate #4 Gullfjellet 2009 and Character #I, Aline Victoria Birkeland, Plate #5 Gullfjellet 2009 () repeat such an act of self-representation: here the character is photographed doing field work, with hammer and chisel in hand, surrounded by a rocky mountain. The captions however reveal—at least to a Scandinavian audience—that the photographs were taken at Gullfjellet (“The Golden Mountain”), a mountain in the vicinity of Birkeland’s/the character’s hometown, Bergen, which lies about 1200 km south of the Arctic Circle and about 2000 km south of the Arctic archipelago Svalbard. At the same time, Birkeland’s double-performative act plays with a motif frequently found in illustrated expedition narratives, as Fridtjof Nansen’s Farthest North or Herbert Ponting’s The Great White South show ().Footnote14 It is the motif of the polar explorer engaged with taking measurements, collecting specimens or doing other fieldwork. This trope, especially in photography, was an important element in the documentation and justification of explorative endeavours (and important to finance new expeditions). Following Fridtjof Nansen’s influential publication The First Crossing of Greenland (Citation1890) many subsequent exploration narratives in fact meticulously list the equipment taken on board the expedition ship, and often mention scientific instruments separately.Footnote15 Here the explorer was in his own element and could show his expertise. When the equipment was used and this act photographically documented, the explorer’s authority could be confirmed. Thus the photograph not only served as a document, but also provided a further platform for self-staging and confirm the explorer as an authorative figure.

Photography and surviving objects as storytelling elements

For the modern polar explorer, photography became a major tool for constructing the mythological and iconic figure of the polar hero on the one hand and proof of “having-been-there” and as an “objective” eyewitness account on the other. As soon as technical developments allowed for it, the camera became an essential item to be included in the explorer’s packing list to document the explorer’s life in the Arctic (Larsen Citation2011). It also became the perfect tool for freezing the one essential element that could not be taken home: snow and ice.Footnote16 What did return with the explorers, however, were the surviving, often personal objects used during the expeditions, and which are treasured like sacred relics in polar museums and collections to this day.Footnote17 Together with the photographs, they are important storytelling elements, or props, to recount the expeditions and in which singular male heroic explorers continue to take centre stage (often attributing minor roles to other crew members). This is exemplified by an exhibition at the Polar Museum of Tromsø which is dedicated to Amundsen’s last journey in 1928, when he tried to rescue Umberto Nobile’s airship expedition but himself disappeared in the ice (). Here the museum’s website communicates that Amundsen’s story takes a central place in the museum and his personal objects and photographic material are essential elements in telling his story.Footnote18

Figure 13. Exhibition views from the exhibition commemorating Roald Amundsen’s disappearance into the ice 1928, Polar Museum, Tromsø

Museum displays are important discursive spaces that, once the headlines are gone, continue “[…] to formulate, give shape to and communicate the narratives of the exploration of the most inaccessible places in the world” (Houltz Citation2013). In their informative and affirmative role, as Houltz has further pointed out, they are not only shapers of a narrative but are also shaped by the narratives of display. This might also be a reason why in one case, when Tonje Bøe Birkeland exhibited her work at a museum of cultural history, her character was perceived as real:

With Character #I Aline Victoria Birkeland, I got to prove how little we actually know about the women explorers, when the Norwegian Polar Institute got in touch with Bergen Museum making inquiries about Aline [where the artwork was shown in 2009]. I never attempted to trick anyone. Perhaps that is what makes The Characters convincing. That a very big part of their stories happens, for real, it happened to someone in the past – or – it happens to me during the process of creation. (Birkeland Citation2019).

Within the context of the Bergen Museum, but also in Birkeland’s photobook, textual and visual elements (surviving objects counted among them) take on reciprocal supporting roles to advance the explorer’s story. The visibly nagged clothes, vanity objects and travel equipment, like in the polar museum, are presented as the surviving relics that further “prove” the character’s existence, while the “Geological Findings” support the character’s credibility as a scientist. The geological objects of course also refer back to the field work executed in Plates #4 and #5 and in fact make a direct reference to historical archiving practices, as a comparison with historical geological collections shows.Footnote19 The Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle in Paris, for example, houses a collection of minerals brought back from one of the most elaborately documented expeditions to the Arctic and Northern Norway (including Svalbard, Aline Victoria Birkeland’s expedition focus), the La Recherche expedition from 1839 and 1840. Here, similarities are striking in terms of labelling, arranging and use of specimen trays from their collection in comparison with Aline Victoria Birkeland’s findings ().

Figure 14. Drawer with geological specimen from the E. Robert collection deriving from the La Recherche expedition to Scandinavia, Laponia, Spitsbergen and the Faroe Islands 1838–40. Courtesy / Copyright Pierre Sans-Jofre / Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris

Tonje Bøe Birkeland’s “String Figure story” thus re-evaluates both museum displays, collections and published travelogues that continue to shape the narratives of the male polar explorer. However, whereas specialized museums are traditionally geographically bound to a limited physical audience (though that has changed with the corona pandemic), the published travel narrative I would argue is the most popular, widely distributed and permanent record used to disseminate the story of the male polar explorer. Evidence is here found in the—still surviving—infinite number of published first-person exploration narratives, which usually were disseminated within a short period following the explorer’s return. Publishers were eager to secure publication rights for such narratives and often pressured explorers to make their accounts available as soon as possible, smelling bestseller material.Footnote20 Translated editions were also largely negotiated at an early stage, reflected in the almost simultaneous publication and distribution in other European countries.Footnote21 In public libraries, and especially those with a polar focus such as the library of the Norwegian Polar Institute in Tromsø, numerous shelves are filled with these surviving male-authored narratives. Also, in the open market rare first editions, new editions or reprints as well as secondary literature on male polar explorers still abound.Footnote22 Thus these polar exploration accounts were not just a visible part of the media landscape then, but still remain with us today. Together with the prevailing visual representations of the Arctic, they are the most pertinent intertextual continuations that connect past and present narratives and continuously feed—despite the climate crisis and the dramatically changing reality of the Arctic—into contemporary Western perceptions and further explorative approaches to the Arctic.Footnote23

Untouched Arctic landscape?

In telling her “String Figure story”, I argue, there is not a single element in which references to historical polar narratives and visual representations are absent. It confirms that it is impossible to engage with the polar regions and escape references to previous representations; it is our collective memory and imagination that influences our current views on the Arctic landscape.Footnote24 But Tonje Bøe Birkeland shows that it is possible to disrupt them. When she inserts herself into the genealogy of polar hero portraiture and thereby subverts gendered roles and spaces, this disruption becomes very obvious. Her strategy becomes somewhat subtler when she references other common Arctic tropes: that of the sublime Arctic landscape devoid of any living being and that in which a solitary figure is seen in the distance. Here Birkeland specifically builds on Arctic tropes that are firmly inscribed in our collective consciousness since the onset of Romanticism, but are today increasingly perceived as sites of mourning and loss.Footnote25

Character #I, Aline Victoria Birkeland, Plate #8 Von Post 2009 () is a panoramic photograph of a glacier emerging in all its grandness. Photographed from a distant and elevated vis-à-vis position, the glacier appears majestic and subtle at the same time, rising above a sea of clouds while pushing back the cloudy sky in the background. Variations of white, light grey and turquoise tint the glacier’s rugged surface, a mountainous icescape revealing cracks and gorges. Like a castle in the air, the glacier’s bottom and end are concealed by clouds of similar colour hues, leaving it up to the viewer to imagine where it may end. Nothing seems to disturb the pristine scene, no human or animal traces visible.

The photograph makes clear references to motifs found in the tradition of Western Polar landscape painting which, according to Samuel Scott, lasted between the 1830s and 1930s (Scott Citation2008). In this period, concurrent with the scientific and popular interests in the polar regions and its expeditions, the Arctic landscape was frequently represented as untouched, sublime and mysterious, often with a spiritual undertone—which did not obstain fearless men from investigating it. There are diverging views as to how the Arctic/Northern landscape was represented during this period, depending on its (national) perspectives. Spring and Schimanski argue that in Austria-Hungary descriptions of landscape and fauna were largely based on symbolic forms of fiction and fantasy, while in Norway it is argued there were more profane descriptions because the Arctic was seen as a working place and economic resource (Spring). Contrary, Sigrid Lien argues that landscape representation in the Norwegian context was overtly symbolic and that until the beginning of the twentieth century, imagery—including photographic—was following the footsteps of national romantic painters, whose motifs were dramatic, nationally charged representations of glaciers, fjords, mountains and waterfalls. Lien, however, detects a representational shift in the second half of the nineteenth century, when Norwegian nation-building processes were heavily pushed and Norway also wanted to represent itself as a modern nation (Lien Citation2014).

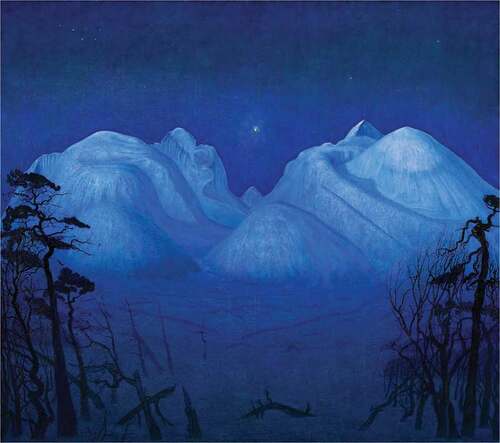

Norway was not alone in building its national image during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and romantic representations of the Arctic/Northern landscape as sublime was a popular genre across national boundaries. Caspar David Friedrich’s Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer (Wanderer above the Sea of Fog) from ca. 1817 is an early example of this romantic tradition, with the sea of fog acting as an amplifier to perceive the mountainous landscape as mysterious and sublime (though it is not necessarily an Arctic/Northern landscape). In a Norwegian context, Peder Balke’s Kystlandskap (Coastal Landscape) from ca. 1860 () and Harald Sohlberg’s Vinternatt i Rondane (Winter Night in the Mountains) from 1914 () even show that the Romantic tradition, despite their overtly different styles and use of artistic materials, expanded over a considerable period of time and well into the twentieth century.Footnote26 Russell Potter expresses that, especially in the context of the Arctic, representations of the sublime outlasted the period of Romantic painters and additionally extended well beyond painting into the illustrated press, magic-lantern shows and circular panoramas, as well as photographic representations and film (Potter Citation2014). Oftentimes painting and photography also worked together:

In the context of time, the painting and the photograph worked in concert, each reinforcing each other. The painting, accepted as the most refined medium of visualization, validated the polar subject matter as worthy of cultural contemplation while at the same time capturing the surprisingly vibrant colors of the polar environment. At the same time, the photograph irrefutably established the veracity of the painting as an “authentic” depiction of polar conditions. (Scott Citation2008, 9)

Figure 16. Peder Balke, Kystlandskap (Coastal Landscape), presumed 1860s, oil on paper, glued on wooden plate, 34 × 52 cm. Photo: Børre Høstland. Courtesy The National Museum of Norway

Figure 17. Harald Sohlberg, Vinternatt i Rondane (Winter Night in the Mountains), 1914, oil on canvas, 160 × 180 cm. Photo: Børre Høstland. Courtesy The National Museum of Norway

Birkeland’s photograph merges this approach: its tableau-like character and the nuanced and precise use of colour photography makes painterly references, while the photographic technique itself relates to the idea of “veracity” to convey an image of the Arctic “as-it-is”.

This is, however, far from the truth. Birkeland’s photograph in fact depicts one of the most visited glaciers of the Svalbard archipelago, the Von Postbreen. Debouching into the Tempelfjorden (earlier called Temple Bay) on the archipelago’s West coast, the glacier became popular as a tourist destination already from the late nineteenth century, in addition to being a place of investigation for numerous scientific expeditions. The tourism industry for the upper classes took off in the second half of the nineteenth century. It is argued that the first midnight sun cruise to Northern Norway was organized from London as early as 1874 (Serck-Hanssen Citation2005, 24). Svalbard (then still called Spitsbergen) soon became a popular tourist destination, too, and subject of interest for different tourist “types”: the singular adventurer exemplified by persons such as mountaineer and art historian Sir Martin Conway; the wealthy magnate who also happened to combine his trip with commercial interests, exemplified by persons such as John Munroe Longyear (Arlov Citation1989) or the larger tourist groups participating in organized luxury cruises and excursions.Footnote27 A photographic postcard with a view of Tempelfjorden from the period between 1910 and 1920 located in the archive of the Norwegian Polar Institute, gives a good indication that this area was already an established tourist destination at the time, thus far from inaccessible and untouched.Footnote28

Tourism, however, should be considered one of the latest invasions of Svalbard, following a long history of what Robert McGhee has called “The Rape of Spitsbergen” (McGhee Citation2007, 173–189). Although Svalbard is not inhabited by a human indigenous population, its land and fauna has been subject to colonization and exploitation through resource extraction—both animal and fossil—early on, documented since the sixteenth century. By the early twentieth century, a large number of animal populations were almost extinct and today we see a further disappearance of wildlife through climate change. Also, fossil resources are mostly exhausted (at least the licensed ones). In addition, numerous scientific expeditions investigated the archipelago, which the nineteenth century art historian and Arctic adventurer Sir Martin Conway argued had begun in earnest in the mid 18th century (Conway Citation[1906] 1995). The already mentioned French La Recherche expedition from 1838–40 is emblematic of these endeavours, resulting in a 26-volume scientific report and five large pictures atlases (Knutsen et al. Citation2002). Though few exhaustive accounts of the number of expeditions to Svalbard and the Arctic exist, in the light of singular written and visual material it is evident that especially Svalbard has been of long-standing interest to people as diverse as whalers, hunters, trappers, capitalists, adventurers, explorers, tourists, politicians, geologists, archaeologists, geographers and other scientists, as well as photographers and artists. To represent Svalbard as pristine, untouched and unattainable then appears to be a paradox when realizing that men have visited and subjugated the archipelago and its surroundings over centuries.

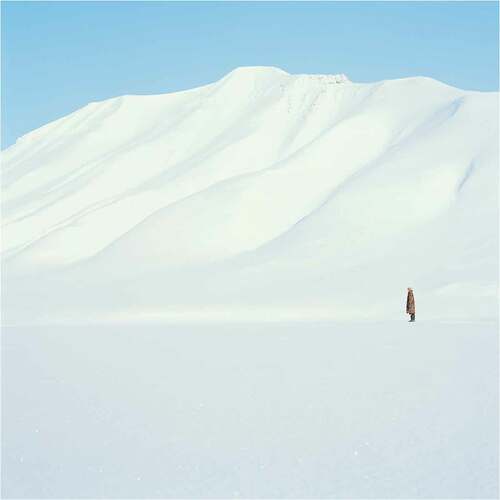

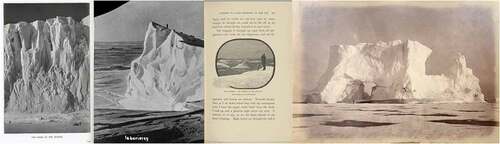

Also, the photograph Character #I Aline Victoria Birkeland, Plate #12 Hiorthfjellet 2009 () plays with the motif of the Arctic sublime, though in this case a small solitary figure is added. The photograph shows the character standing in the vast, snow-covered landscape at the foot of a mountain. It presents us with a clichéd image of human presence in the Arctic—nature is big, and we are small—and has, similar to the image of the sublime, empty landscape, been circulating as a recurrent motif in different visual media including painting, drawing, lithography and photography. According to Susan Barr:

During most of the nineteenth century, however, there is a tendency for both landscape painters and photographers in Norway and abroad to emphasize the romantic aspect of the wild, polar nature: the contrast between small, insignificant people and large and powerful nature, and between light and dark as portrayed by land and sea compared with snow and ice. […] Although the scenery appears recognizable and naturalistic, there is scarcely an image that does not show tiny people amongst the high, sheer mountains or deeply-crevassed glaciers, or even the ultimate symbols of man’s misguided attempts to penetrate the Arctic wilderness, crosses and shipwrecks. (Barr Citation1997, 48).

Both tropes repetitively appear in visual representations of the polar regions that were to a large extent executed by trained photographers, illustrators and artists. These were often either integral members of expeditions such as Herbert Ponting who was part of Scott’s expedition team to the Antarctic, engaged in tourism such as Anders B. Wilse for luxury cruises to Svalbard, or hired in the aftermath to make lithographs, drawings or paintings based on explorer’s photographs or sketches such as in the case of Roald Amundsen or Fridtjof Nansen.Footnote29 Less frequently artists took their own initiative to travel to the polar regions, such as British-American painter William Bradford (1823–1892) whose travels to Greenland in 1869 resulted in one of the most elaborate photobooks to this day, The Arctic Regions (Bradford Citation1873).Footnote30 Other artists in turn did not travel to the polar regions themselves but based their artworks on the available mediated narratives and foregoing visual representations. The motif of the small human figure in the vast polar landscape (), however, proved to be a recurring theme and became especially prevalent in photographic representations of the explorer in the “eternal” ice. This trope, Elena Glasberg argues, has helped to establish what she termed the “Heroic Age aesthetic” (Glasberg Glasberg, Citation2012b, 91–92).

Figure 19. From left to right: The Home of the Echoes, published on page 149 of Ponting’s book The Great White South (1924); Isbarieren, 1911 (reproduced by Anders B. Wilse from Amundsen’s South Pole expedition); Seal Hunting. The Captain on the Lookout, published on page 213 of Nansen’s book The First Crossing of Greenland (1890); Detail from William Bradford’s book The Arctic Regions (1873)

Conclusion

Tonje Bøe Birkeland’s practice of embodying imagined turn of the century woman explorers establishes direct references to textual and visual narratives deployed by historical Arctic explorers and their derivatives. At first glance this approach could be solely interpreted as an homage, with an uncritical reflection on their motivations for Arctic exploration and their self-fashioning activities. One could thus argue that Birkeland not only re-enacts their heroic stories but is also complicit with a male-centered canon that has dominated polar history for far too long.Footnote31

However, such a position would appear undifferentiated. It would not pay attention to an artistic practice that not only represents a different worldview than that of the male explorers Birkeland refers to, but also to a practice that raises questions of gender roles and representation, today. Birkeland’s character/alter ego communicates a subjective, situated, embodied worldview that, even if cloaked as a white European woman, opposes the idea that the world is there to be mapped, measured, extracted, conquered, colonized; in short, as Achille Mbembe pointed out, a worldview commonly found among Europeans that sees the Earth as belonging to them (Mbembe Citation2020). Birkeland’s position as an artist is not a “disembodied” one, and not one that claims authority and subordinate “other” voices. Whether this concerns the written descriptions of her own position as a woman and her experiences, or her impressions of the other persons she meets, neither judgmental language nor objectivist claims can be detected. Also, at no moment her character maps and names the territory she travels in. On the contrary. Like the fictional heroines reaching the South Pole in Ursula K. LeGuin’s short story Sur, Birkeland leaves no traces in the landscape; the only thing that remains is her fabulated “String Figure story” told through text, objects and photographic images. And although Birkeland references iconic motifs that were largely disseminated by the explorers and their expedition members, she also consciously excludes others. There are no photographs of successful animal hunts with slaughtered polar bears or seals; no photographs of other, lower-rank expedition members; no photographs of dramatic ship scenes or everyday homosocial activities on the ship; no photographs of indigenous peoples. In this context, Birkeland’s representation of the Arctic, and in particular Svalbard, as empty and untouched could even reversely indicate that the empty landscape is as a result of long-lasting exploitative human activities. Also, the small human figure in the vast Arctic landscape can be read differently in this context, where the human becomes insignificant and at the brink of disappearance. In that sense, the situated knowledge acquired in the process of following the character’s story is one that asks as to rethink, to reconfigure the Arctic as a gendered space in order to speculate: what if women had had a larger role in Arctic exploration narratives? What if alternative worldviews had dominated European societies in the long nineteenth century? What if scientific discourses had not claimed to be objective? What if fictional figures can help us to speculate about a future that is liveable and shared by all? Birkeland invites us to fabulate about the answers.

Acknowledgments

I am very grateful for the continuous and constructive support of my PhD supervisors Dr. Elin Haugdal and Dr. Hanne Hammer Stien in shaping this article and my thesis. Thank you also to Tonje Bøe Birkeland for providing me with illustrations and dedicating her time to a lengthy interview as part of my research for this article. Thanks also to the staff at the Musée de minéralogie and the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris, in particular to Pierre Sans-Jofre for digging in the museum’s archives to retrieve and photograph the collection of geological specimen brought back by E. Robert from the La Recherche expedition between 1838 and 1840.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stephanie von Spreter

Stephanie Von Spreter is currently Doctoral Research Fellow (PhD) in Art History at the Department of Language and Culture, UiT the Arctic University of Norway. The PhD is anchored in the research group Worlding Northern Art (WONA). Her thesis examines contemporary photographic art that engages with the Arctic as a gendered, colonial and ecological space. She recently termed responsible for the seminar Mediating the Arctic and the North. Contexts, Agents, Distribution in collaboration with Humboldt University (Dr. Linn Burchert, Department of Art and Visual History). Von Spreter previously served as the artistic director of Fotogalleriet, Oslo (2011-18) and has worked for international exhibitions including the 3rd, 4th and 5th Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, the 50. Venice Biennale and Documenta11. Stephanie von Spreter also works as a freelance curator and writer.

Notes

1. More specific motivations include the search for the Northwest/Northeast Passage; the search for lost expeditions; reaching the poles; scientific research; territorial expansion; resource extraction; trade; adventure etc.

2. In the context of UiT The Arctic University of Norway, see SARP—The Sámi art research project (2009-2013), Arctic Modernities (2013-16) and Arctic Voices (2020-2024).

3. Defining the polar regions as “terra nullius” or “no man’s land” has in Arctic discourses most often been applied to the Svalbard archipelago, which was not under any legislative rule until the Svalbard Treaty 1920. Surely, also the widely published book No Man’s Land by Sir Martin Conway following his travels to the archipelago (Conway Citation[1906] 1995) contributed to equating Svalbard with this term. However, also other (circumpolar) areas have been termed “no man’s land”. Regarding Greenland see (Jonsson 2010 (2003)). Regarding the opinion that the circumpolar north was still seen this way in the post-war period see (McGhee Citation2007, ch.7).

4. It was only discovered in the eighteenth century that there was a correspondent icecap to the Arctic in the South (Scott Citation2008).

5. I explicitly refer to Griselda Pollock’s “matrix of space” which determines the production and reception of an artist’s work. The experiential space is the social space from which the representation is made whereby the “[…] producer is shaped within a spatially orchestrated social structure which is lived at both psychic and social levels.” (Pollock Citation2003, 92).

6. In 2011 Norway celebrated the “Nansen-Amundsen-Year” on the occasion of Nansen’s 150th birthday and Amundsen’s 100th anniversary of reaching the South Pole. As part of the celebrations, the 1911 race to the South Pole was re-enacted, with both “teams” in place (Amundsen’s and Scott’s). The only major difference was that the impersonated Amundsen was greeted by the Norwegian prime minister upon arrival at the pole, in addition to numerous journalists. This re-enactment shows that Amundsen’s achievement is still relevant to Norway and the expression of a national identity. Houltz writes: “Re-enactment rituals such as this one show with great clarity that century-old narratives of polar exploration are still relevant in modern society, both culturally and politically. They remain important tools for justifying polar ambitions and for incorporating them in processes of national identity-making.” (Houltz Citation2013).

7. There is so far only one exception: in four photographs of Character #I the artist let her mother embody the character (Plates #1, #6, #9, #11).

8. One example is the recent MOSAiC Expedition, for which the RV Polarstern drifted in the Arctic ice for one year from September 2019 to October 2020, openly referencing Fridtjof Nansen’s achievement 1893-96. See https://mosaic-expedition.org/expedition/.

9. The Characters exists in a limited edition of 300, published by Bergen Kjøtt Publishing which the artist runs herself.

10. The photobook is one of Birkeland’s main artistic mediums. In an exhibition context her photography takes the most prominent place.

11. I would like to point out that Lund and Berg published their findings in 2011, while Birkeland’s Character #I was already executed in 2009/2010, thus prior to publication and pointing out this genealogy.

12. Examples are: museum displays, webpages informing about polar histories, memorial lectures etc.

13. Birkeland’s photographs can also connect to a tradition of cross-dressing and queer photography as it was already practiced in the late nineteenth century. Many such photographs often remained in the private sphere, presumably because they did not conform to normative gender representations. An exhibition shown at the Rencontres d’Arles in 2016 entitled Sincerely Queer. Sébastien Lifshitz Collection was one of the first large-scale public presentations of queer photography from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century that more closely examined the switching of gender roles and the subversive aspects of photography. See https://www.rencontres-arles.com/en/expositions/view/106/sincerely-queer (accessed 18.08.2021). In 1996 the Norwegian National Museum for Photography showed photographs that belonged to the photographers and women activists Marie Høeg (1866-1949) and Bolette Berg (1872-1944) who ran the photo studio Berg & Høeg. The photographs were found by coincidence in the 1980s in a box labelled “private” and had never been shown. It contained a number of staged photographs taken by and of Marie Høeg and Bolette Berg between 1895 and 1903. All photographs show the two women acting out different gender stereotypes of bourgeois society, all of them with a humorous undertone. Amongst the photographs there is also a portrait of Marie Høeg dressed up as a polar explorer in a hooded fur coat, clearly referencing Nansen’s portrait. See https://www.preusmuseum.no/nor/Oppdag-samlingene/Fotografer/Bolette-Berg-og-Marie-Hoeeg (accessed 18.08.2021).

14. Some illustrative examples in Farthest North are found on pages 163 (Magnetic Observations. From A Photograph), 203 (Chronometer Observations), 293 (Observing Eclipse of the Sun), 281 (Reading the Temperature with a Lens), 302 and 369 (Taking Water Temperature); In The Great White South, such imagery is found on pages 96 (Probing a crevasse), 115 (Dr. Simpson at the Magnetometer, and Sending up a balloon to test the air currents), 173 (E.L. Nelson at his biological “hole”).

15. In The First Crossing of Greenland, Nansen dedicates an entire chapter to equipment (Nansen Citation1890a, 66-69). Also Amundsen dedicates a chapter to equipment in his South Pole travelogue (Amundsen Citation1912).

16. This was first done on a large scale by the artist Olafur Elliasson with his work Ice Watch (2014) when twelve free-floating iceblocks from the Greenland icesheet were transported to London, Paris and Copenhagen. See https://olafureliasson.net/archive/artwork/WEK109190/ice-watch (accessed 18.08.2021).

17. There are in fact also other ephemeral objects that tell stories of and from the Arctic such as ship newspapers that largely disintegrated in the frozen seas and that previously have not received large attention. These more ephemeral objects have been traced by Hester Blum in her recent book The News at the Ends of the Earth: The Print Culture of Polar Exploration. Here it is also revealed that cross-dressing took place amongst expedition members when they set up theatre plays to motivate the crew and avoid depression and ennui. Because there were no women on board, men embodied the female characters. The ship newspapers announced the plays as if they were large public events (Blum Citation2019).

18. See https://uit.no/tmu/utstillinger/utstilling?p_document_id=398854 (accessed 18.08.2021).

19. Tonje Bøe Birkeland actually hunts, in a race against time, for these historical objects herself at flea markets, online auctions, private attics and derelict museum collections.

20. Historical sources reveal that the Norwegian publishing house Aschehoug & Co. competed with another publisher (John Grieg, Bergen) to secure the rights of Nansen’s Fram over Polhavet. He succeeded by offering Nansen a fee of 88,000 Norwegian kroner, in addition to a percentage of the sale. Records show that Nansen received a total fee of 112,926 Norwegian kroner, which according to the Norwegian National Bank would correspond to roughly 8,950,000 Norwegian kroner in 2019 (https://www.norges-bank.no/tema/Statistikk/Priskalkulator/). The number of copies set for the first edition was 20,000. In comparison, other authors connected to Aschehoug received a considerably lower fee and lower print-run (on average around 2,000 kr or less, print-run 3,000 copies or less). Nansen’s extraordinary fee and the decision to print Fram over Polhavet in an edition of 20,000 was based on the earlier sales success of Paa ski over Grønland and fierce competition amongst publishers. For detailed information see (Rudeng Citation1997; Tveterås Citation1972).

21. Examples of numerous reprinted editions are, limiting myself to the publications written by Norwegian explorers and first editions/translations: Fridtjof Nansen, Paa Ski over Grønland, 2 vol. (Oslo: Aschehoug, 1890), first English edition The First Crossing of Greenland, (London: Longmans, Green and Co., 1890), first Swedish edition På skidor genom Grönland (Stockholm: Albert Bonnier, 1890), first Finnish edition Suksilla poikki Grönlannin (Helsingissä: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava, 1896), first French edition A travers le Grönland (Paris, 1893), first German edition Auf Schneeschuhen durch Grönland (Hamburg: Verlagsanstalt und Druckerei AG, 1891, 1898); Fridtjof Nansen, Fram over Polhavet: den norske polarfærd 1893-1896 (first published Oslo: Aschehoug, 1897), first English editions Farthest North (London: George Newnes 1897 / Westminster: Archibald Constable and Company, 1897 and 1900 / London: Macmillan, 1897 / London: George Newnes, 1898), first French edition Vers le pole (Paris: Ernest Flammarion, 1897), first German edition In Nacht und Eis: Die Norwegische Polarexpedition 1893-1896 (Leipzig: Brockhaus, 1897); Roald Amundsen, Nordvestpassagen Beretning Om Gjøa-Ekspeditionen 1903-1907, 2 vol. (first published Oslo: Aschehoug, 1907), first English edition The North West Passage: being the record of a voyage of exploration of the ship “Gjøa” 1903-1907, 2 vol. (London: Archibald Constable, 1908); Roald Amundsen, Sydpolen: Den Norske Sydpolsfærd Med Fram 1910-1912 (first published Oslo: Dybwads, 1912), first Danish edition (København: Gyldendal, 1912), first English Edition The South Pole: An Account of the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition in the “Fram”, 1910-1912 (London: John Murray, 1912); first German edition Die Eroberung des Südpols: Die norwegische Südpolfahrt mit dem Fram 1910-1912 (München: Lehmann, 1912), first French edition Au Pôle sud (1913).

22. Between 2012-2015 for example, Cambridge University Press republished no less than 202 Polar exploration books under the series “Cambridge Library Collection—Polar Exploration”. See https://www.cambridge.org/core/series/cambridge-library-collection-polar-exploration/A74356110B19FE39ECE2FB41463BC531#, (accessed 11.12.2020).

23. Two recent examples are the Russian “flag planting performance” on the seabed underneath the North Pole in 2007 and the already mentioned MOSAiC Expedition 2019-20.

24. I here refer to Simon Schama’s argument that there exists an intimate link between terrain, mythology and culture and that “[…] inherited landscape myths and memories share two common characteristics: their surprising endurance through the centuries and their power to shape institutions that we still live with” (Schama Citation1996, 15).

25. A physical manifestation of such a site of mourning and loss is the ceremony commemorating the disappearance of the Okjökull glacier in western Iceland in August 2019. A similar ceremony took place at the former location of the Pitzol glacier in Switzerland in September 2019.

26. Vinternatt i Rondane was in fact awarded the title “Norges nasjonalmaleri” (Norway’s national painting) through a public vote initiated by the Norwegian national broadcaster NRK in 1995. See https://www.nasjonalmuseet.no/samlingen/objekt/NG.M.01185 (accessed 20.08.2021).

27. The image archive of the Norwegian Polar Institute holds a number of photographs of Tempelfjorden from a cruise with the ship S.Y. Irma to Spitsbergen in summer 1925. The archive also states that the Norwegian photographer A.B. Wilse photographed the area by commission of the cruise company in the years between 1905 and 1913. See https://bildearkiv.npolar.no/fotoweb/archives/5000-Bilder/?q=S.Y%20Irma%27s%20cruise%20tempelfjorden (accessed 24.08.2021). Still today tourist agencies offer guided boat tours to the glacier.

28. Owned by the image archive of the Norwegian Polar Institute, see https://bildearkiv.npolar.no/fotoweb/archives/5000-Bilder/NP_bilder/NP030000/NP025085.jpg.info#c=%2Ffotoweb%2Farchives%2F5000-Bilder%2F%3Fq%3DNP025085 (accessed 24.08.2021).

29. This was for various reasons: the first Kodak portable camera (#1) was sold in 1888, meaning that prior to that photographing in the polar regions was even more of a challenge, being in need of a mobile darkroom; thus, drawings were integral to a visual documentation of the polar regions, and subsequent lithographs and woodcuts essential for a larger visual distribution. Also, it was not until the early twentieth century that printing techniques were developed in a way that publications could entail a large number of photographic illustrations. For a detailed investigation of this subject, see (Larsen Citation2011).

30. Illustrative examples can be found in Herbert Ponting’s The Great White South (Ponting Citation1924), William Bradford’s The Arctic Regions (Bradford Citation1873) and Fridtjof Nansen’s Paa ski over Grønland (Nansen Citation1890b).

31. One could even argue further that Birkeland weaves on the complicity of bourgeois women within a colonial context, as has been raised in more recent scholarly literature, investigating the relationship between women, travel writing and Nordic colonialism (Reeploeg Citation2019).

References

- Aarekol, L. 2016. “Arctic Trophy Hunters, Tourism and Masculinities, 1827–1914.” Acta Borealia 33 (2): 123–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08003831.2016.1238173.

- Amundsen, R. 1912. “ Sydpolen: Den Norske Sydpolsfærd Med Fram 1910-1912. Med Portrætter, Illustrationer Og Karter 1. Copenhagen: Gyldendal.

- Amundsen, R. 1927. My Life as an Explorer. Garden City. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company.

- Arlov, T. B. 1989 A Short History of Svalbard Polarhåndbok (Printed Edition) 4 . Oslo: Norsk polarinstitutt.

- Barr, S. 1997. “Expedition Photography in Polar Areas.” Photoresearcher 6 (March): 47–54.

- Berg, R. 2006. “Gender in Polar Air: Roald Amundsen and His Aeronautics.” Acta Borealia 23 (2): 130–144. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08003830601026818.

- Berg, S. F., and H. Ø. Lund. 2011. Norske Polarheltbilder 1888-1928. Oslo: Nasjonalbiblioteket.

- Birkeland, T. B. 1985. Character #V: Bertha Bolette Boyd, 1900-1985. The Bhutan Trilogy. Bergen, Norway: Bergen Kjøtt Publishing.

- Birkeland, T. B. 2019. “Interview between Stephanie Von Spreter and Tonje Bøe Birkeland.”

- Birkeland, T. B. 2016. The Characters. Bergen: Bergen Kjøtt.

- Bloom, L. E. 2010. “Arctic Spaces: Politics and Aesthetics in True North and Gender on Ice.” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art 26 (Spring) 2010 (26): 30–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/10757163-2010-26-30.

- Bloom, L. 1993 Gender on Ice: American Ideologies of Polar Expeditions 10 American Culture . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Blum, H. 2019. The News at the Ends of the Earth: The Print Culture of Polar Exploration. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Bradford, W. 1873. The Arctic Regions. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Low and Searle.

- Calle, S. 1999. Double Game. London: Violette Editions.

- Conway, W. M. [1906] 1995. No Man’s Land: A History of Spitsbergen from Its Discovery in 1596 to the Beginning of the Scientific Exploration of the Country. Oslo: Damms antikvariat.

- Foote, S., and L. Stephanie. 2014. “Editors’ Column.” Resilience: A Journal of the Environmental Humanities 1: 1. doi:https://doi.org/10.5250/resilience.1.1.00.

- Frank, S. K. 2015. “Mythos of the North Pole: The Top of the World.” Nordlit 35. april. doi:https://doi.org/10.7557/13.3422.

- Gaupseth, S. 2017. “How to Be A Heroic Explorer in A Friendly Arctic: A Chronotopic Approach to Self-Representation in Vilhjalmur Stefansson’s the Friendly Arctic: The Story of Five Years in Polar Regions (1921).” UiT The Arctic University of Norway.

- Glasberg, E. 2002. “Refusing History at the End of the Earth: Ursula Le Guin’s “Sur” and the 2000-01 Women’s Antarctica Crossing.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 21 (1): 99–121. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/4149218.

- Glasberg, E. 2012a. Antarctica as Cultural Critique: The Gendered Politics of Scientific Exploration and Climate Change. 1st ed ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US: Imprint: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Glasberg, E. 2012bPhotography on Ice Antarctica as Cultural Critique: The Gendered Politics of Scientific Exploration and Climate Change, E. Glasberg. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US: Imprint: Palgrave Macmillan 89–108 .

- Grace, S. 2008. “Inventing Mina Benson Hubbard: From Her 1905 Expedition across Labrador to Her 2005 Centennial (And Beyond).” S & F Online 7 (1): 7.

- Hansson, H., and A. Ryall. 2017. Arctic Modernities: The Environmental, the Exotic and the Everyday. Newcastle upon Tyne, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Haraway, D. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–599. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066.

- Haraway, D. 2016. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, North Carolina; London, England: Duke University Press.

- Houltz, A. 2013. “Displaying the Polar Nation: Nordic Museum Exhibits and Polar Ambitions.” In Science, Geopolitics and Culture in the Polar Region: Norden beyond Borders, edited by S. Sörlin, 293–327. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Hubbard, M. B., and S. Grace. 2008. A Woman’s Way through Unknown Labrador. Labrador, Canada: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

- Jonsson, S. 2010 2003. “Foreword to the Reprint of Stories from Scoresbysund.” In Stories from Scoresbysund: Photographs, Colonisation and Mapping, edited by F. Hansen and T. O. Nielsen. Copenhagen: Pia Arke Selskabet & Kuratorisk aktion.

- Kjeldaas, S. 2015. “Gendered Arctic.” Nordlit 35 April. doi:https://doi.org/10.7557/13.3443.

- Knutsen, N. M., M. Markussen, G. E. Barstad, A. Cassanello, and P. Posti. 2002. La Recherche. En ekspedisjon mot Nord/Une expédition vers le Nord. Angelica: Tromsø.

- Larsen, P. 2011. “Polfarernes Vei Inn I Den Visuelle Kulturen.” In Norske Polarheltbilder 1888-1928, edited by H. Ø. Lund and S. F. Berg, 12–17. Oslo: Nasjonalbiblioteket.

- Lien, S. 2014. “Not «just Another Boring Tree» - Landskapet Som Identitetsmarkør I Norsk Og Samisk Fotograf. [Not “ just another boring tree » - Landscape as identity marker in Norwegian and Sami photographer.].” Kunst Og Kultur 97 (3): 148–159. doi:https://doi.org/10.18261/1504-3029-2014-03-04.

- Mbembe, A. 2020 Out of the Dark Night 22.10.2020 Oslo & Johannesburg (Zoom) . Oslo & Johannesburg: Theory from the Margins.

- McGhee, R. 2007. The Last Imaginary Place: A Human History of the Arctic World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Mills, S. 1991. Discourses of Difference: An Analysis of Women’s Travel Writing and Colonialism. London: Routledge.

- Nansen, F. 1890a. The First Crossing of Greenland. London: Longmans, Green and .

- Nansen, F. 1890b. Paa Ski over Grønland. Aschehoug.

- Pollock, Griselda 2003Modernity and the Spaces of Femininity Vision and Difference: Feminism, Femininity and the Histories of Art Routledge Classics . London: Routledge 70–127 .

- Ponting, H. G. 1924. The Great White South or with Scott in the Antarctic. Being an Account of Experiences with Captain Scott’s South Pole Expedition and of the Nature Life of the Antarctic. 6. London: Duckworth & Co. .

- Potter, R. A. 2014. Frozen Zones: Bradford, Arctic Photography and 19th Century Visual Culture. New Bedford, Massachusetts: New Bedford Whaling Museum.

- Pratt, M. L. 2008. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. 2nd ed ed. New York: Routledge.

- Reeploeg, S. 2019. “Women in the Arctic: Gendering Coloniality in Travel Narratives from the Far North, 1907-1930.” Scandinavian Studies 91 (1–2): 182. doi:https://doi.org/10.5406/scanstud.91.1-2.0182.

- Rudeng, E. 1997. William Nygaard. Oslo: Aschehoug.

- Ryall, A. 2019. “Gender in the Twentieth-Century Polar Archive.” In Arctic Archives: Ice, Memory and Entropy, edited by S. K. Frank and K. A. Jakobsen, 177–196. Bielefeld: Bielefeld: transcript Verlag.

- Ryall, A 1989. “Reisebeskrivelser—etnologisk kilde eller topografisk eventyr?” Dugnad. Tidsskrift for Etnologi 15 (3 15–27).

- Schama, S. 1996. Landscape and Memory. London: Fontana Press.

- Scott, S. 2008. “Frozen Requiem. The Golden Age of Polar Landscape Painting.” In To the End of the Earth. Painting the Polar Landscape. Salem, Massachusetts: Peabody Essex Museum.

- Serck-Hanssen, C. 2005Fra Mørkets Rike Til Midnattssolens Land. Bilder Av Nord-Norge Fra Det 16. Til Det 19. Århundre Voyage pittoresque. Nordnorsk kunstmuseum: Knut Ljøgodt and Anne Aaserud. Tromsø 8–28 .

- Spring, U., and J. Schimanski. 2015. “The Useless Arctic: Exploiting Nature in the Arctic in the 1870s.” Nordlit 35 (35) (april): 13–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.7557/13.3423.

- Stam, D. H. 2019. Adventures in Polar Reading: The Book Cultures of High Latitudes. New York: Grolier Club.

- Stam, D. H., and J. F. Dean. 2019Arctic Survivals. The Restoration of Records Recovered from Lost Polar Expeditions Adventures in Polar Reading: The Book Cultures of High Latitudes, D. H. Stam. New York: Grolier Club 49–59 .

- Teukolsky, R. 2015. “Cartomania: Sensation, Celebrity, and the Democratized Portrait.” Victorian Studies 57 (3): 462+. doi:https://doi.org/10.2979/victorianstudies.57.3.462.

- Thompson, C. 2011 Travel Writing The New Critical Idiom . London: Routledge.

- Tveterås, H. L. 1972. Et Norsk Kulturforlag Gjennom Hundre År. Aschehoug 1872-1972. Oslo: H. Aschehoug & Co. (W. Nygaard).

- Wollstonecraft, M. 1796/2004. Letters Written during a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark. London: Centaur Press.