ABSTRACT

The relation of law and art is conventionally understood through a disciplinary divide that presents art as an instrument of legal practice and scholarship or, alternatively, presents law as potential context for artistic engagement. Moving beyond disciplinary definitions, in this article we explore how art and law, as modes of ordering and action in the world, often overlap in their respective desires to engage existing material orders. Whereas law’s claim of producing order appears self-evident, we try to highlight, through a concept of legislative arts, the often-overlooked similar function of artistic practices. At the heart of what we refer to as legislative arts are practices that aim to challenge law’s claim of authority in ordering social life through tactical combinations of elements of art and law. In examining a set of examples that include the Tamms Year Ten campaign to close a super-max prison in the United States, the work of Forensic Architecture and practices of passport forgery, we aim to highlight the possibility of manifesting social orders beyond an exclusive reliance upon state laws. Pointing to the potentials of such legislative arts practices, this article suggests that the material ordering quality of artistic and legal practices can, and perhaps should, be weaponized for challenging and remaking the world of unjust state laws.

Introduction

The year is 2016 and setting Copenhagen’s now defunct Center for Art on Migration Politics (CAMP) community center. Artist Daniela Ortiz is seated on stage, reading a prepared statement while receiving a blood transfusion from a Spanish national seated next to her. In the course of its brief duration that comes across as part press conference, part performance, Ortiz’s reading is a gesture of impassioned dissent against contemporary Spanish and EU nationality laws.

Originally of Peruvian descent and four months pregnant, Ortiz speaks of how, despite having lived in Spain for nine years, both she and the child she is due to give birth to are not eligible for Spanish and EU citizenship. A result of Spain’s criteria for nationality and citizenship relying on the legal principle of Jus sanguinis (“right of blood”), according to which citizenship is granted and transferred via family bloodlines. A legal principle which, as Ortiz makes clear in her statement, has long and enduring roots in exclusionary racist and colonial practices.

The reading is affecting. Ortiz is deliberately employing her platform as an internationally recognized artist known for a strong anti-colonial practice to denounce this particular and personal example of colonial violence. Doing so by situating and giving embodied witness to how such regimes play out in practice—both on her and the baby to be.

The CAMP performance (Ortiz Citation2016)Footnote1 is recorded for posterity and regularly included in exhibitions of Ortiz’s work under the title of Jus sanguinis, circulating as one example of an artistic craft capable of both dynamically and forcibly articulating political issues across a range of different modalities, and also as a statement that makes visible and draws further attention to the workings and effects of a specific legal practice, whose name the work bears. In a work such as Ortiz’s, it is possible to witness an art practice that addresses the law—that calls out and questions the law’s normative modes of ordering within the equally normative and rendered traditions of art, the gallery space, and so on. The performance and its filmed recording circulate as personal testimony and witness statement with no functional legal bearing, but nonetheless are still crafted and carefully staged so as to render the law as material to be contested, questioned and, potentially, imagined anew—or differently.

Ortiz’s performance is one example of a visibly growing interest on the part of both artists and lawyers engaging with and adapting methods from both art and law with an aim of effecting change within the law. While such intersections between art and law are not a new phenomenon, they have in recent years increased in number and form. In the domain of law, there is the significant rise in the range, consistency, and scale by which artistic practices have taken center stage in legal practice. These include visually crafted modes of presentation and argumentation within legal practice that are only likely to increase with the ongoing tide of digitalization. Indeed, the future of law and visual arts as intertwined practices appears to be so evident that legal scholars now regularly call for the necessity of visual literacy for law school graduates (e.g. Sherwin Citation2019)—not to mention multiple law and art initiatives emerging at law schools and related international institutes.Footnote2 Meanwhile, on the arts end of the spectrum, so-called politically oriented modes of artistic practice have become a relative commonplace, but the specific act of engaging more directly with the law as material for artistic intervention represents an important, though under analyzed, emerging terrain.

These intertwined momentums and practices of art and law, coming from both disciplines, invite re-examination of the relationship between art and law. Raising a number of questions along the way, such as what elements do these two seemingly separate disciplinary practices have in common with one another? What emergent relations between the two are being imagined and put into practice by contemporary practitioners from art and law? And what other productive modes of interaction between the two might be possible if one works through their relations not via a disciplinary lens but rather through one of what they do in the world?

In this article, we intentionally do not depart from questions such as what constitutes law and what constitutes art, not least because such questions invoke debates, categorizations, and gatekeeping practices that we specifically aim to overcome in our own provocation under the rubric of legislative arts. Instead, the article understands both law and art as modes of acting in the world, with a shared interest in engaging material and relational orders of the world. Nevertheless, while law and art are both modes of acting in the world, it is important to remember that law makes a more dominant claim on modes of ordering the world. With Ortiz’s critique in mind, it is also imperative to note that most of the examples examined in this paper emerge from and craft their modes of address to the legal systems of settler colonial and colonial nation states, whose many ruinous legacies of what counts as law and legality should continuously be kept in mind.

In engaging with law, the jurisgenerative tendencies of artistic practice are often overlooked. By jurisgenerative tendencies we mean the legally common language of referring to acts of authoring law, or at least claiming to having authored a rivalrous mode of action that orders the world in its own limited manner.Footnote3 Clearly art and artistic practices, unlike law’s modes of action, do not possess the guarantees of the state apparatus of force to enact its orders in the world—especially when such orders rival those of state law. Yet there are occasions—such as the examples of the Tamms Year Ten prison campaign and of passport forgery looked at here—where artistic practices act in the world in ways that can be understood as nothing less than a jurisgenerative force. Legislative arts therefore refers to the often overlooked potential of both artistic and alternative legal practices as capable of remaking the orders of state laws.

This article will give an overview of the ways in which relations between art and law are commonly conceptualized in and from these two disciplinary milieux, including discussion of the original naming and conceptual framing of the term “legislative art” by Reynolds and Eisenman (Citation2013). In pluralizing Reynolds and colleagues’ original term as legislative arts, we take both direct inspiration from their conceptualization, while also working to further develop the stakes and potentials held in this evocative naming of a field of conceptual and practical possibilities. By examining and, in a sense, curating a diverse set of examples of legislative arts, we aim to bring to the fore certain existent and emerging characteristics, tensions, and productive modes of practice as they can be seen to arise in notable interplays of art and law.

Law within the arts

“What do you mean, a poetic revolutionary, a meditating gunrunner?”

—Audre Lorde (Citation1984)

While art practices have established traditions of addressing questions of power and politics,Footnote4 it is noticeable in recent decades that increasing numbers of artists openly claim and attend to political and activist dimensions or approaches in their work. Amidst such politically directed forms of artistic practice, there have in recent years emerged a small but intriguing subset of examples of artists directing their attention more specifically towards the material, social, and political effects that law and legality have the power to produce. In addressing this paper’s aim of examining intersections of art and law, this section will consider examples of what can be understood as law within the arts, examining art practices that, in one way or another, use the law as a direct context or material for their approaches.

Why, one might ask, the recent rise of elements of the law in artistic practice? In one sense, the answer is obvious in a time when the law stands in support of drone strikes, police brutality, the ongoing denial of queer and trans* rights, multiform violence of border and migration regimes and all manner of legally ordained predatory financial practices and environmental destructions—to name but a few. Walter Benjamin, writing in 1935 in Nazi Germany, famously spoke of the crescendo of forces by which fascism had charged certain elements of art, technology, and politics with a nihilistic embrace of destruction so total that it could be said to have become aesthetic in nature, a situation he only half-mockingly described as “the consummation” of an approach of art for art’s sake (“l’art pour l’art”). In the face of such movements, Benjamin spoke of the pressing need to resist such forces, demanding that the artist “responds by politicizing art” (Benjamin et al. Citation2008, 42). Today, almost a century on from Benjamin, politically oriented art practices are a relative commonplace, taking place across the political spectrum and manifesting in a range of different media and settings.

When attempting to consider art practices that might fruitfully be considered using a lens of legislative arts, perhaps most obvious is the use of art as a mobilizing tool for supporting legal actions or counteractions. In such examples, art applies its aesthetic capacities in ways that aim to draw attention to the legal cause in question, with the artist working in these contexts as a kind of creative comrade and campaigner. Legislative arts in this mobilizing mode of address can be understood as practices oriented towards a specific task of making perceptible, and thus ultimately legislatively actionable, the concerns and issues with which they are engaged.

The initial coining of the term legislative art emerged from the Tamms Year Ten project (hereinafter TY10), a particularly noteworthy example of art used as a mobilizing tool for challenging the law.Footnote5 Launched in 2008, TY10 was a legislative campaign advocating for the closure of the Tamms Correctional Center in the US state of Illinois. The Tamms Correctional Center was a so-called “supermax” prison facility that over the 10 years of its existence had enforced a set of heinous solitary confinement regimes. TY10 came into being as a project aiming to bring the prison and its practices to a halt. Initiated by the artist and teacher Laurie Jo Reynolds in collaboration with art historian Stephen Eisenman, attorney Jean Snyder, poet Nadya Pittendrigh, and the family members and inmates of Tamms, TY10 was carried out over a period of five years, ending with the successful closure of Tamms in 2013.

Inspired by Brazilian playwright Augusto Boal’s (Citation1998) concept and practice of legislative theater, Reynolds and colleagues began to describe aspects of the work done in TY10 as a form of “legislative art”. In an article co-written by Reynolds and Eisenman around the time of the closure of Tamms, they characterize legislative art as an emerging terrain of practice ripe for intervention and involvement by artists:

For centuries, artists have been concerned with systems of ratio, perspective, symmetry, geometry, anatomy, tactility and optics. For the last 50 years, they have taken on ecology, real estate, advertising, media, cybernetic, genetic, language, gender, racial and class systems. As political artists with real-world political goals, we need to engage with government systems. That’s legislative art. Prison policies are made by the state, so you go to the state to change them. (Reynolds and Eisenman Citation2013)

In this conception of Reynolds and Eisenman’s, legislative art is aimed at mobilizing and effecting change through state legislatures. As is often the case in any movements aimed at effecting legislative change—such as the highly instructive and dynamic examples from AIDS activismFootnote6—such a practice can involve becoming intimately familiar with legal and political ins and outs, while also collectively building ties with actors and institutions capable of aiding such efforts in modes of address that can be both pragmatic and creative in their approaches.

TY10 made explicit use of art practices in mobilizing community awareness and legislative momentum. Expanding on earlier efforts such as the Tamms Poetry Committee (of which Reynolds was a member), TY10 developed a range of art-oriented mobilizing approaches. This included what would become the relatively well-known Photo Requests from Solitary initiative,Footnote7 in which Tamms inmates could send requests for photos that could be fulfilled by members of the public (an initiative that has since continued beyond the Tamms project). Delivered both to the Tamms inmates and shared in public settings and online, each photo request and its fulfilment activates potential channels of communication between the public and those held in solitary confinement; small pinholes puncturing the carceral state with the affective light and shadow of everyday desires and enforced longing.

In examples such as these, it is possible to see what can be understood as essential components of a mobilizing legislative arts practice: working to connect with those most directly affected by the law and making visible—through artistically inflected methods and practices—the relevant experiences of these groups towards an aim of opening up or further mobilizing participation and action on the issue in question. Additionally, as witnessed in the example of TY10, a legislative arts approach can involve modes of practice that, because of urgency or deemed practicality, are willing to work within and on the terms of the law, resulting in artistic practices that craft their forms of address in ways that work to speak directly to the law. Rather than art for art’s sake, a mode of artistic address that, while imbued with certain abolitionist horizons, is at least partly also for the law’s sake.

Augusto Boal’s writings on what he termed “legislative theater” are instructive on aesthetic modes of address aimed ultimately at making claims for legislative and political transformation. For Boal, following in the traditions of Bertolt Brecht and Paulo Freire, at the heart of any such practice is the creation of modes of engagement able to effectively raise awareness and ultimately inspire resistance against epistemic and aesthetic injustices (Dalaqua Citation2020). Such work is achieved via approaches that work to reconfigure a subject’s relation to the legislative matter in question, a reconfiguration that can include a recalibrating of what the law might allow for. As such, a specific aim of legislative theatre, as outlined by Boal and his collaborators, is not simply to stimulate a desire for change, but “to go further and to transform that desire into law” (Boal Citation1998, 20).Footnote8 With the ostensibly artistic setting of the theater becoming not simply a kind of public moot court for the testing of claims, but a forum for comparatively more affective and autonomous participations, contestations and collective engagements with matters of the law.

Where some attend to potential limitations in what have been characterized as “activist” art practices,Footnote9 others, such as art critic and writer Lucy Lippard, in an early and helpfully expansive reading on what can count as activist art practice, shift away from a focus on the use-value of art to that of its involvement and commitment, making a distinction between political art that is “socially concerned” and activist art that is “socially involved” (Lippard Citation1984, 349). Such an emphasis on activating committed forms of involvement is evident in examples such as Boal’s legislative theater or TY10, and, conversely, it is often a lack of involvement and commitment on the part of any legislative arts practice that will be one of the more telling reasons for its shortcomings. In a talk reflecting on the work of TY10, Reynolds describes artistic modes of involvement in legislative campaigns as both a potentially unique element but also, ultimately, a co-creator in what is an overall commitment and mobilizing sensibility directed towards a common aim:

The way that I think about the aesthetics of this project, and about legislative art, is that, although there are clearly art forms imbedded in it, like the photo project and the posters, and, you know, the conceptual stuff, like the Supermax Subscriptions … that I sort of like think of the whole thing as an autonomous system … that is what is art … it’s that entire commitment, that entire, kind of, obsession, that drive … everyone facing in the same direction … the form of attention that we pay to everything … The way this came about, and the way we were connected to each other … like, all of the things that shaped us … all those things are the aesthetic. (Reynolds, cited in Stabler Citation2018, 250-1)

Over the course of five years, the TY10 campaign continued its modes of legislative intervention, using approaches that included classic (mud stenciling on busy public throughways) and novel (having the active hub of the TY10 “campaign office” at a city art gallery) forms of artistically influenced mobilization. Crafting and carrying out such actions in tandem with other central elements of their campaign, which included the pulling in of human rights monitors, arranging of hearings, working with various state legislators to introduce legislation and ongoing negotiations with the Department of Corrections. After a difficult battle with the guards’ union, the Tamms Correctional Center was successfully shut down in 2013.

Before moving to study examples of art emerging from within the domain of the law, it is worth briefly highlighting that a descriptor such as legislative arts can apply not only to art aimed at challenging the law but also what can be described as art in the service of the law. This can include everything from monuments dedicated to legislation to the many publicly commissioned and purchased pieces of artFootnote10 that decorate judicial and other institutional spaces of power, with art typically employed in such instances as institutional servant, commemorator, and propogandist of the power of law and the state.

Perhaps more relevant though are examples of art practices that, whether intentionally or not, serve the law in their shoring up, expanding or recalibrating of the perceptual and normative interpretive limits—and ultimately material reach—of what the law might allow for. Benjamin was hinting towards one such instance in comparing the techno-fetishist vectors visible in Futurist art practices with those of rising forms of fascism, a phenomenon that Benjamin described as “the aestheticizing of politics” (Benjamin et al. Citation2008, 42). Such strains of practice can involve overt but also more subtly intertwined examples of art and law, such as the development in the early 20th century of military camouflage, which involved synthesizing expertise and skills drawn from Cubism, natural ecology, zoology and biology with the laws of armed conflict (Forsyth Citation2013; Parsa Citation2017). In examples such as these, the artist(s) in question might be understood as naïve or willing collaborators in their crafting and shifting of the perceptual (and at a nearer remove than they might realize, the ethically and legally permissible). As Benjamin also makes clear, art practices—whether in the service of or against the law—can also act as important early indicators and signalers of things to come. With the question perhaps arising, as characterized by Virilio and Lotringer (Citation2005), to what degree the turn by art movements such as Cubism’s turn to the deconstruction of fields of perception and representation followed the destruction brought on by war.

Such directions of travel from art into law and from law into art highlight a potential for what Lippard (Citation1984, 341) characterizes as energies of empowerment and subversion that carry with them a variety of tensions and challenges. One central question in this respect for any legislative arts practice is the challenge of working on the terms of one mode of ordering or another, especially when that form of ordering and its discursive norms are understood as being substantially different from or resistant to the approaches being brought into it. A potentially rivalrous but also, in some cases, intimate relation that can be furthered traced by turning to questions and modes of artistic practices as they arise from within the domain of the law.

Arts within the law

On 17 November 2020, the Global Legal Action Network (hereinafter GLAN) filed a complaint against Greece to the UN Human Rights Committee concerning, in part, the illegal pushbacks of migrants across the Evros/Meriç.Footnote11 This submission included as part of its evidence visual reconstruction of events provided by Forensic Architecture (hereinafter FA). This is the regular format of collaboration between these two professional milieus: FA produces evidence of a human rights violation, often by visualization, 3D modelling or situated testimonies, from and around which GLAN constructs a legal complaint for submission to a relevant judicial body.Footnote12

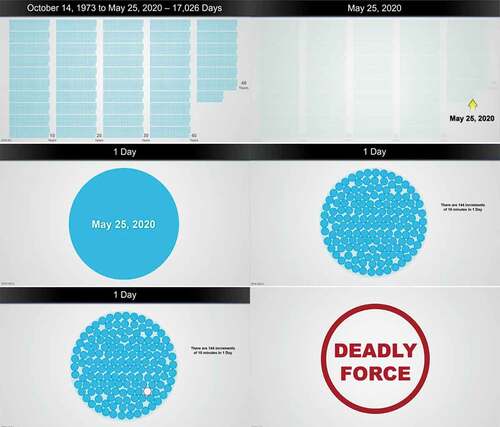

More recently, during closing arguments, the legal team representing George Floyd in the 2021 trial of a Minneapolis police officer presented a sequence of digital slideshow visualizations that began with a slide filled with dots standing for each day of George Floyd’s life. This slide was followed by an animated transition that zoomed into one enlarged dot representing the final day of Floyd’s life, which in turn was followed by a further transition in which the enlarged dot was shown to be composed of 144 dots representing 10-minute increments in Floyd’s life during this day, with one of those dots then shown to be empty. This single empty dot, the jury was told, represented the roughly 9 minutes that the police officer knelt on Floyd’s neck, resulting in his murder by the officer. The sequence concluded with a final enlarging of this empty dot and the text “DEADLY FORCE” imprinted in the middle. A sequence of carefully crafted images and animated transitions intended to illustrate, in an informative but also overtly affective manner, what it means to suddenly, and abruptly, not live anymore.

Examples such as these of artistically informed visual modes of presentation employed by lawyers to make their cases are by no means unique. They follow in the wake of many other examples, such as the case of Rodney King against the Los Angeles Police Department in 1992–93, where the fate of a trial with a diametrically opposing outcome to that of the George Floyd ruling hung upon the ways in which the visual evidence of racially motivated police brutality was presented, seen and interpreted.Footnote13 Another oft-cited example of such a visual turn in hearings of different kinds is US Secretary of State Colin Powell’s 2003 PowerPoint presentation of evidence of so-called “weapons of mass destruction” to the UN Security Council, imbued and intentionally crafted with knowing combinations of visual, audio, and textual artefacts. What Powell described as an “accumulation of facts” whose visually oriented mode of presentation a later biography revealed to have been chosen after members of Powell’s team decided specifically against using the text-only speech supplied to them by the Vice-President’s office (DeYoung Citation2006, 462; as discussed in Stark and Paravel Citation2008, 17). Such intentionally crafted modes of “professional vision” (Goodwin Citation1994), presenting and performing their aesthetically informed discursive effects under a pretense of expert technical and self-evident objectivity, are modes of representational and visual persuasion that now regularly transpire in courtrooms.

While positivist legal practitioners might prefer not to dwell on or acknowledge such an influx of artistic elements into modes of legal practice, others, such as GLAN and FA, work openly with what it means to infuse the law with practices from outside the law, and can be seen to be part of an emerging number of initiatives aimed at expanding the available capacities of the law with new tools from outside of its domain. The relatively recent initiative Logische Phantasie Lab, a research agency not dissimilar to FA, brings together a host of legal and artistic forms of expertise in order to investigate “injustices in their political, legal, economic, social, physical, environmental, temporal and spatial entanglements”.Footnote14 Other notable examples include the interdisciplinary laboratory NuLawLab and their offerings of “legal design” seminars and courses to law students aimed ostensibly at familiarizing them with tools of argument making, (re)presentation and persuasion from disciplines such as architecture, service design, user experience design, etc. The stated aim of NuLawLab is “transforming legal education, legal profession and delivery of legal services” through a reimagining of the legal system as such.Footnote15

The usefulness of artistic tools for legal practices may not be surprising, but a systematized and professional manner of integrating artistic practices as part and parcel of the legal practice—as seen in FA, NuLawLab, and the Logische Phantasie Lab—invites a revisiting of the relation of art and law, through posing questions such as how art and law relate to one another in such contexts? What forms of practices become possible in their coming together? What ways can each contribute to the other? And what can be expected in terms of any transformative force from such engagements with art in legal practice?

It is worth pointing out that lawyers and legal scholars have for some time talked about their profession as an artful craft—and rightly so, if we consider the dramatic aspect of the courtroom process (Leiboff Citation2018; Morgan Citation2005). That said, it is not just the material practices of law that have resulted in practitioners and scholars appealing to an artistic lens as a means of understanding or promoting their profession and discipline. The legal form itself has also been described aesthetically—i.e. as part of a sensory and perceptive regime amounting to apprehension of human identities and behaviors (Schlag Citation2002).

The disciplinary proximity of law and art was in fact evident and active within earlier Renaissance humanist traditions and educations (Douzinas Citation2008, 23). This proximity between law and art, as Goodrich points out, can be traced back to Cicero’s assertion that lawyers are budding actors trained in the art of persuasion for the purpose of appearing before judges and juries. In this sense, to be trained in legal rhetoric “was an inculcation in all of the artistic tools necessary for acting, or more prosaically for successfully staging a cause of action” (Goodrich Citation2009, 5). In a certain respect, more recent efforts in to bridge art and law—by establishing different institutions, art-law labs, and various scholarly “turns” such as academic programs in law and literature—are manifestations of a historical divide that has arisen as a result of an increased professionalization of both art and law. As Douzinas (Citation2008) writes, it was “positivist jurisprudence [that] started presenting law as the preserve of a specialist science-like expertise, without spiritual claims or emotional investment and set into motion the inexorable process of separation between art and law”. This positivist vision of law as reason versus art as emotion retains the language of this historical divide, to the degree that when lawyers invoke the language of art or artfulness it mostly refers to any aspect of the legal profession that is difficult to capture by law’s supposed reasonability, or aspects that are too complicated, technical, or abstract to be explained.Footnote16 Most famously, this is captured in former president of the ICJ (1991–94) Sir Robert Jennings referring to treaty interpretation as “an art rather than a science”, a part of which includes the artistry of keeping an “appearance of a science” while engaging in the art of interpretation (Jennings Citation1967, 544).

Outside of such disciplinary name-calling, what often remains is a general interest of lawyers in the performative, theatrical, and visual aspects of their craft. Artistic practices and expressions linger in the vicinity of the legal field to act as vehicles for presenting legal arguments effectively and persuasivelyFootnote17; as a means of materializing and operationalizing abstract meanings and values, giving visibility and material existence to law (Goodrich Citation2009, 4; Stolk and Vos Citation2020); as a pedagogic tool (Sherwin Citation2019), offering of an ethical opening to reflect on the corporeal and scenic aspects of the legal profession (Leiboff Citation2018); or else as a means of telling the story of law’s violence by way of staging the law (Drumbl Citation2020).

Yet the historical concurrence of law and the humanities is rarely invoked as an indication of the legislative dimension of the disciplinary kinship of law, such as art, but only as an indication of the performative skills involved in the practice of law itself. In other words, in this history of being at first in proximity and then abandoning one another, only to come back together again, it is law that consumes other practices, techniques, and technologies—while in the imaginaries of its highest priests, law itself shall not be equally treated by other disciplines or practices. Cicero’s generosity in calling lawyers artists would appear not to be reciprocal. Lawyers may see themselves as engaging in the art of justice or acting out the requirements of justice in the scenic platforms of courts, tribunals, and other public forums, but they (lawyers) could hardly acknowledge that the artistic instruments they use are in themselves evidence of an independent, effective, or even more just form of order outside the restrictive staging of the state law.

Could any case of legislative arts be imagined in which the intertwined contours of art and law produce a legal-artistic practice persuasive and effective enough to go beyond showcasing law and its violence and instead alleviate law’s violence, undo it and replace its established orders? A similar trajectory of thinking has been expressed, although in a different context and for a different purpose, by media scholar Cornelia Vismann (Citation2008), who argues that new media practices such as printing, file making, and archiving have brought with them new forms of legalities and legal conceptualizations. Can we imagine the intersection of art and law as offering similarly novel relationships or legalities such as technology and law are often said to?Footnote18

In his observations of moot court competitions, international law scholar Wouter Werner comes very close to such a reflection. According to Werner (Citation2019, 168–9), moot courts, read as theatrics of law turned into pedagogic tools, can provide an apt forum for the emergence of different modes of legal reasoning, modes that might not fly easily within the courtrooms. However, this radical opportunity, Werner notes, is missed in a legal educational practice, which commonly ends up instrumentalizing theatre for the purpose of perfection through repetition of legal argument—as opposed to prioritizing nuances of theatrical rehearsal as a means towards a constant reimagination of laws’ limits and the limits of legal imagination (172).

A final point here is that the typically narrow view of understanding the intersection of law and art as one of the deployment of art as a tool in the service of the law—e.g. in evidence gathering, as persuasion technique, or mode of inquiry and critique—even though largely predominant, seriously confines our conception of the ways in which art can be conducive of alternative forces of legality.

Having attempted to outline several key dynamics and tensions that arise in certain interplays of art and law, we will now examine a pair of examples that emphasize the multifaceted ways in which certain practices can be read as examples of legislative arts, while also working to consider how legislative arts as a concept and practice might be pushed further.

Forensic Architecture: tactical maneuvers across art and law

Among the many different possible examples, one might read a concept and practice such as legislative arts through, the work of Forensic Architecture (FA) stands out as one of the most multilayered and instructive examples to date.Footnote19 Under the stewardship of founder and director Eyal Weizman, FA’s interdisciplinary investigations into contemporary conflicts and human rights violations have garnered increasing attention in the art world and beyond.Footnote20

As the name of the group implies, the work of FA brings together two seemingly separate domains of practice: forensics and architecture. As with a term such as legislative arts, this conjunction of different practices opens onto interesting possibilities, with FA having pursued several of these possibilities over their last decade of practice. Describing themselves as a “research agency” composed of a team that “includes architects, software developers, filmmakers, investigative journalists, artists, scientists and lawyers” (Forensic Architecture Citation2020), FA has long had a specific interest in crafting forms of evidence that can be used within legal and political processes.

In writings by Weizman and other members of the group,Footnote21 FA describes how their approach to evidence gathering and building cases is informed by a range of discussions on key topics such as truth, aesthetics, and representation. For Weizman, the group’s notion of forensics is one that attends to contested processes of “materialization and mediatization” by crafting forms of reconstruction and evidence-making that are not averse to using art and aesthetics to address the contested problems of truth-telling (Weizman, cited in Bois et al. Citation2016, 120–1). FA’s understanding of “forensic aesthetics” is one that “includes a close attention to image, frame, detail, and so on”, and for this reason, “people who come from art, photography, or film schools are incredibly useful. Some of them bring a kind of sensibility and attention that helps us decode images. And there’s an art to evidence-making too. It has to be composed, produced, performed” (122). Especially “in forums like courts, where forensic aesthetics is about the art of presentation” (123).

As with film-maker Harun Farocki’s (Citation2004) notion of the “operational image”, which Weizman and other members of the group acknowledge as a key influence, such an approach works to show how the always contested field of representation has been manifested and operationalized. As artist and theorist Hito Steyerl (Citation2014) writes of Farocki’s method, “Conflict is not only part of the content, but also of the production setting. […] Production holds conflict. It is its most basic form”. Given such an understanding of the contested and aesthetic nature at the heart of representation, evidence-making and (legal) truth claims, it is not surprising to hear Weizman argue that “seeing is a kind of construction that is also conceptual and culturally conditioned, hence the indispensability of artistic sensibility” (Weizman, cited in Bois et al. Citation2016, 122).

In their bringing together of tools from different disciplines for forms of legislative and political claims-making, FA’s approach can be understood as being both pragmatic and tactical in nature. Weizman’s description of FA’s relation to the law makes this clear:

At present it is no longer enough to critique the politics of representation. I haven’t given up on uncertainties, contradictions, ambiguities. Our notion of truth is not positivistic, but one that is pragmatically constructed with all the difficulties of representation. Producing evidence depends on aesthetics, presentation, and representation. We don’t approach the law naively, as if courts were benevolent institutions – on the contrary, they are often disposed as instruments of oppression; rather, we understand all moves to be tactical. (120)

In this statement one witnesses, on the one hand, an example of art for the law’s sake—a practice that is willing to work, at least somewhat, on the terms of the law. At the same time, Weizman positions FA’s approach as not being naïve in respect to the workings and restrictions of the law. The group is fully aware of the ways in which, “The court itself is allergic to the work of aesthetics and art because it sees in them the danger of manipulation, emotional or illusionary, that takes the viewer away from supposedly unmediated experience” (122). To this extent, FA’s approach can be understood as a mobilization of arts and other practices aimed at challenging, or at least recalibrating, the boundaries of the law. It does so with a conscious political horizon in mind (even though not necessarily pronounced)—hence the language of tactics and strategies. That is to say, FA sees potential success in the courts as only one possible outcome of its practice—not the sole objective, nor the most significant one. This conscious approach to the limited utility of the courts and the legal system for the larger political horizons of FA makes their approach to law different from traditional ones in that it treats law as a forum of tactical operation and political instrumentalization.

Finally, as in the legislative theatre of Augusto Boal, it is noticeable how a notion of forum is central to FA’s work. For FA, the court of law is one of several possible forums towards which they direct their work. The same carefully crafted work of evidence submitted as part of a case against Israeli land grabs might also feature in an exhibition setting, with the gallery acting as a public forum for sharing such evidence, particularly for cases “that the courts won’t hear”, including “testimonies and oral traditions that they dismiss as hearsay” (Weizman, cited in Bois et al. Citation2016, 133). In both working within institutions but also moving from one institutional setting and its accompanying modes of ordering to another, there is a potentially generative questioning of the forums and settings within which FA’s evidentiary forms of address might be presented:

Maybe we can think of art institutions in a way analogous to courts. If the gallery is to a certain extent contaminated by its context, funding, and politics, so is the university and so are the courts and the institutions of law. From our perspective we must try to negotiate these problems, without adhering to a religion of the law or of art – that is, with recognition of the limits of each and being realistic about what is possible to achieve with each. (133)

This statement describes an approach that emphasizes rigidities and also potential elasticities within different modes of ordering, and how their being subject to manipulation by all actors involved make them into material battlegrounds and contested forums that FA attempts—through mobilizing infusions of artistic, documentary, legal, architectural, sonic, and other forms of evidentiary modes of address—to operate and make tactical gains within.

FA’s work to date has been highly novel but also takes its place in a lineage of approaches that, each in their own hybrid (Michael et al. Citation2018) and emergent fashions, attempt the tricky balancing acts of working across various disciplines, institutions, and their accompanying modes of ordering, resulting in outcomes that can be both innovative and subject to debate. In the case of FA, one can witness some of the strongest and carefully considered examples of what can at least partly be understood as a legislative arts practice, a practice that notably continues to develop through FA’s evolving practices and collaborations with a range of intriguing partners (as evidenced most recently in their latest partnership with the European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights). At the same time, when visiting an exhibition such as FA’s 2018 Counter Investigations show at the ICA in London, one might ask: what are the contours and forum-making potentials that an exhibit such as this one puts into motion? A visitor can move from room to room of technologically adept and skillfully rendered forms of presentation that offer multiple modalities and layers of detail and complexity, asking audiences to take time to dwell in the register of an investigative forensic aesthetic that is highly cognitive in its modes of information giving, but also imbued with affective contours that aim to deepen and also respect and reward attention giving.

But it is also worth considering what is lost or missed in such a courtroom-like forensic dissemination of information. Architect and researcher Nishat Awan takes up such questions in a careful articulation of how certain forms of forensically oriented modes of witnessing and presentation can “partake in the placing of expert knowledge and objects above political subjects” (Awan Citation2016, 318). Which raises the question of whether in those instances where FA takes the law as its central interlocutor, are there are ways in which certain forms of evidence-giving in an exhibition setting risk obscuring the political question by placing it too squarely in procedural and evidentiary modes of assessment. This risk is not as present in examples such as the Tamms Year Ten project, nor in an exhibition such as Ortiz’s recent This land will never be fertile for having given birth to colonisers (Citation2019) with its overt and assertive anti-colonialism that deploys art as social critique of the historical force and violence of law—aiming not at changing the law per se but engaging it to the point of hollowing the law from its claims of authority over any established order.

This is not to criticize FA’s overall mission. The political critiques and forms of evidence-making produced by FA to date have been crucial to a number of cases in which they have participated. Moreover, their work as currently constructed, unlike typical political art practices, carries with it the potential of more direct legal change-making. The recent shuttering of an FA exhibition at Miami Dade College’s Museum of Art and DesignFootnote22 is just one example of this legal, change-making threat that FA’s work carries within it, with the threat of litigation or crackdowns on legislative arts practices being perhaps one of the more telling signs of their potential power.

These are ongoing questions of what it means to work with and on the terms of one form of ordering or another, and how doing so carries with it both risks and potentials. Legislative arts approaches such as these raise questions of audience, effectiveness, and the difficulties of crafting and presenting work that might speak to judges and gallery visitors, individual law makers and wider general publics. Questions of crafting and tactics that point in turn to a fundamental issue lying at the heart of any legislative arts approach: that of where to position and practically enact one’s relation to the various forms of ordering that both law and art carry with them. Should a change or goal-oriented project adopt a pragmatic relation to the law, one that aims to try to change the law from within the law? Or is a fundamental disobedience and rejection of working in the service of the law and its forms of ordering necessary? Similarly, does any tactical deployment of art come at the cost of what Werner sees as the peak potential of interactions between art and law—i.e. entertaining thoughts that could not fly in a courtroom in order to expand the thinkable in the law (Werner Citation2019)? It is to such questions that we turn in the final example looked at here.

Rivalling arts of ordering

So far, this paper has worked to show how practices from art and law can use elements of each other’s respective practices to achieve various forms of legislative and political change. Legal professionals can call upon artists and artistic tools to aid in crafting effective and affective evidence, hoping to achieve change from and through the legal system. And artists can take the law as material for their craft, shaping, staging, and performing issues in order to convincingly and affectively reveal the law’s violence and the need for changes to the law. But if law can be performed and if its operations and orders are often made effective through artistic craftings of legal practice, is it not possible to assume that certain artistic crafts, performances, and actions can also, potentially, possess a claim to legality and order?

Our concluding example concerns the practice of border transgression using forged travel documents. According to the conservative count of the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the European border space has since 2014 claimed 9,623 lives in the Mediterranean Sea alone.Footnote23 Both Ortiz’s Jus Sanguinis performance and the ongoing collaborations and cases of FA and GLAN engage directly with this violence of European borders. Where Ortiz’s performance critiques the laws of European citizenship and migration for their racial and colonial pedigree, GLAN and FA take states’ enforcement of those laws to judicial forums, seeking legal accountability for border death and violence. A further possible function of legislative arts in this context can be that of providing a pathway, narrow as it may be, for a safer passage—compared to, for instance, braving the Mediterranean Sea—by exploiting the law’s dependency on material and artistic expressions for effective and concrete existence. Travel document forgery takes this extra step, engaging artistic craft to momentarily replace the official laws of movement by offering alternative material orders of mobility.

An immediate objection may arise against acknowledging passport forgery as a legislative arts practice that replaces, contests, and rivals legal order by pointing to the illegality of document forgery. But the legality and illegality of an action such as this is largely a matter of political contestation. Amir Heidari, a well-known passport forger and travel broker (otherwise known as a smuggler), speaking with the social anthropologist Shahram Khosravi, describes how states behave rather hypocritically in terms of defining the boundaries of legality and illegality, especially if put in a historical context. Reflecting on 14 years of imprisonment in Sweden for his role in assisting tens of thousands of people fleeing persecution, Heidari challenges the idea of the illegality of his activities by pointing to the manufactured nature of legality and lawful acts themselves:

Do you remember how the Canadian embassy forged passports for the staff of the American embassy and saved them from the Iranian revolutionary forces in 1980? They are heroes but I am a criminal …. In fact, I do not smuggle people. I take them to the border where they can seek asylum. When they have sought asylum a refugee lawyer takes care of their cases. Why is my job a crime but not the lawyer’s? We both have the same goal. (Heidari, in Khosravi Citation2010, 110)

Legal philosopher Hans Lindahl (Citation2013) observes that the boundaries of a legal order are defined by its spatial, temporal, membership, and content limits. That is to say, these orders define who ought to/not do what, when and where. But what we conceive as legal order is a contingent order resulting from various historical struggles. To contest these limits and to lay claims upon transformations of legal boundaries involves behaviors that, as Lindahl states, “call into question the distinction itself between legality and illegality as drawn by a legal order in a given situation” (31). What Lindahl refers to as not illegal but a-legal acts. In Lindahl’s conceptualization, illegal is distinguished by its privative form, indicated in the prefix “il”, whereas a-legal behavior “intimates another legal order” (37). At stake in such actions is the very normative framework that evaluates some acts as legal and others as illegal. For someone like Heidari, these distinctions are crystal clear: “humane law does not recognize any border. Borders are constructed by inhumane minds” (Heidari, in Khosravi Citation2010, 108). Or elsewhere, when he explicitly sets his actions vis-a-vis those of the nation-state:

I am my own migration board. I work for those who are declined visas and passports. I work for anyone who has no passport, and with pleasure help them go wherever they want […] My thesis is to make the world more international. (109)

In the book The Design Politics of the Passport, design scholar Mahmoud Keshavarz (Citation2018) explores the material configuration of the grossly unequal global migratory regime through, in part, studying practices of passport forgery. Keshavarz argues that the global hierarchy of travel is facilitated and maintained through material configurations that owe significantly to artistic craft, making, and design. In such a reading, that links bodies to identities, to states and ultimately to unequal rights of travel, lie material configurations that in part include passports, visas, border infrastructures, identification papers, and biometric technologies, etc. Understanding the legal mobility regime through its material and artificial composition allows for conceptualizing passport forgery as a form of negotiation by way of “technically reconfiguring and materially rearticulating the right to move”, and not as an anomaly of the legal order (75). A skillful forger and a persuasively forged passport grant its holder the otherwise denied right to travel across borders. Drawing from an intimate and expert knowledge of issues of legal and artistic practice, forgers “manipulate the material articulations of the world” and propose “alternative modes of acting in the world” (76).

Forgery can thus be understood as an aesthetic practice, one that redistributes modes of sensibility in relation to those put in place by laws of migration and border control. It is a material act of making and designing, one that not only might occupy a place in world art catalogues but also takes its holder around the world by seriously challenging, reticulating and rivalling the material and official ordering of the world as devised by state laws. In treating forgery here as an example of a legislative arts practice, we don’t intend to diminish the urgency and imperatives of this particular mode of intervening into orders of the world. Rather we want to register its qualities as a practice in both an intimate but also openly rivalrous relationship with the law and its modes of ordering. Travel document forgery uses the law and its many aesthetic elements as materials for its own craft, resulting in an aesthetically and legally directed practice that in this case is judged, not by art audiences and critics but by agents of the law (e.g. border guards, passport scanners, etc.).

An example such as travel document forgery also helps to emphasize, as in the examples of TY10 and FA, how a legislative arts approach can also be understood as a pluralizing practice. Specifically, in the case of travel document forgery, a legal plurality (including forms of law beyond state and state actions) and also a plurality that looks beyond conventional understandings of what counts as art, artistic practice and artistry. From such a perspective, a forger of passports can be understood as an artist, a crafts-(wo)man and a non-state agent of cross-border normativity, with forgery as a creative and forceful intervention into the meaning making practices of law. An intervention that, on the one hand, challenges and rivals state laws’ claims of authority and monopoly over normative productions of the world as a border space, and, on the other hand, takes art out of a relation of consumption and instrumentalization at the hand of legal practitioners.

Conclusion

“In our hands they must become weapons … ”

—Harun Farocki, The Words of the Chairman, 1967

As is evident in the range of examples looked at in this article, law and art have in many contexts been categorized as ostensibly separate, at times rivalrous discursive and operative modes of ordering. A term such as legislative arts partly serves to further emphasize the seeming uniqueness that a merging of the domains of legal and artistic practice might involve. At the same time, as we have seen, practices such as these are no longer unique, coming after many years of artists making a variety of challenges to preconceived partitions between art and politics, as well as growing numbers of examples from emerging legal initiatives of various kinds. These emerging practices point to notably pluralistic and potentially transformative approaches that are able to work their cases and causes through and across discursive and professional realms of practice typically treated as separate and distinct. In the legislative theater of Boal, the citizen can become legislator. Adopting forensic aesthetics such as that of FA, an artist or lawyer can become detective and evidence giver, both in the gallery and court of law.

Albert Stabler (to date, the main interrogator of Reynolds’ notion of legislative art), in speaking on the example of TY10 and attempting to address a question of “why is closing a prison ‘art?’” rightly highlights how the point is not to dwell on the naming of any such practices as art, but rather to explore “the discordant connotations of the analogies suggested by ‘legislative art’” (Stabler Citation2018, 6). In pursuing several such discordant connotations, we have attempted to trace and further expand on certain openings suggested by a concept of legislative art, while also arguing for those practices that deploy elements of artistic or legal craft in order to make up a rivalrous order vis-à-vis that of the law. This is done not so much with a view towards establishing some new, definitive label and category of legislative arts that can be seamlessly applied to certain practices of art and the law, but rather to look closer at the telling tensions and generative possibilities that arise in the linking together of these evolving modes of ordering, relating, and acting in the world.

When examining practices of legislative arts, it can at times be hard to ignore the rattling of disciplinary and institutional endeavors struggling to maintain their enforced kingdoms and the separations and distinctions carried under their names. Nevertheless, certain emergent formations can be seen to be working both through but also beyond such tensions and distinctions. Reminding one of Black feminist poet and thinker Audre Lorde’s comment on the intimate relations that inevitably transpire between supposedly separate or compartmentalized aspects of living, and how “yes, there is a hierarchy. There is a difference between painting a back fence and writing a poem, but only one of quantity” (Lorde Citation1984, 58).

As witnessed in the examples looked at here, such emergent formations and their attentive interplays and modes of ordering carry within them overt and covert quantities of empowerment and obedience, ignorance and intimacy, subservience and subversion. In the historical and present relations of law and art, and beyond the inconsequential instrumentalizations, tactical deployments and artistic or legal critiques, lie grounds for alternative practices of law and art, and the accompanying modes of ordering, relating, and acting in the world that might emerge from such constellations. Practices that, regardless of whether the practitioners involved identify as artist or lawyer, might weaponize—in intimate, subversive, and potentially empowering fashion—generative interplays of law and art capable of producing rivaling orders to those of the present.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Mahmoud Keshavarz, Loren Britton, and participants of the seminar series at the Center for the Politics of Transnational Law at the Vrije University of Amsterdam and the Values group at Tema T, Linköping University for helpful engagements and comments on earlier versions of this text.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Amin Parsa

Amin Parsa is lecturer in sociology of law and public international law. His research looks into the relation of law and technology in various contexts such as counterinsurgency, war and border control.

Eric Snodgrass

Eric Snodgrass is a Guest lecturer in the Department of Technology and Social Change at Linköping University, Sweden, and Senior lecturer at the Department of Design+Change at Linnaeus University, Sweden. His research looks into bottom up infrastructures that work to imagine, materialise and sustain forms of change.

Notes

1. Performed as part of CAMP’s Deportation Regime: Artistic responses to state practices and lived experience of forced removal event: http://campcph.org/past/deportation-regime. See also Marronage’s (Citation2019) “The white gaze within the structure” for a critique of certain elements of CAMP’s curatorial practices.

2. To name but a few: the Art Lab for Human Rights at UNESCO, the Centre for International and European Law’s “The art and International Law Laboratory” at the Asser Institute, or the Centre for Law, Arts and the Humanities at Australian National University. Also of interest are legal practices that have turned into art projects, such as The Congo Tribunal Project (http://www.the-congo-tribunal.com), as well as examples such as The Informal Justice Court Project, in which inmates of Lagos prison stage court proceedings of their own cases as a way of gaining legal skills, receiving legal help but also gaining control over their own life within the law and legal process (https://informaljusticecourt.com, last accessed on 27 June 2021).

3. In this article, we draw on Robert Cover’s notion of jurisgenesis. Accordingly, “the creation of legal meaning—‘jurisgenesis’—takes place always through an essentially cultural medium. Although the state is not necessarily the creator of legal meaning, the creative process is collective or social” (Cover Citation1983, 11).

4. For writings touching on political and activist dimensions in art see, amongst many others, Lippard (Citation1984) Rancière (Citation2004), Groys (Citation2014) and Castellano (Citation2020).

5. See Stabler (Citation2018) for a thorough and helpful account of both the Tamms Year 10 project and his own analysis of the project’s concept and practice of legislative art.

6. To name but a few from the many rich histories of AIDS activism, see Crimp (Citation1988), Epstein (Citation1998) and Gould (Citation2009).

7. Photo Requests from Solitary can be found at https://solitarywatch.org/photo-requests-solitary/. See also http://photorequestsfromsolitary.org.

8. Boal’s book highlights thirteen pieces of legislation that were successfully passed as a result of his group’s work.

9. E.g. Groys’s (Citation2014) “On Art Activism”. In writing on how a “quasi-ontological uselessness infects art activism and dooms it to failure”, Groys highlights tensions and perceived contradictions raised already a century earlier by figures such as Tolstoy (Citation1996[1897]) in his tract What is Art? See also Steyerl’s (Citation2015) recent descriptions of the hollowing out and co-option of “art’s conditions of possibility” by a range of oppressive state and financial actors.

10. See Hoffman (Citation1991) for a discussion of legal debates in the US over controversial government purchased or commissioned pieces of art in the public realm.

11. Details of this case can be found on the GLAN webpage at https://www.glanlaw.org/enforced-disappearance-greece (last accessed on 27 June 2021). For the submitted complaint to the UN Human Rights Committee see https://c5e65ece-003b-4d73-aa76-854664da4e33.filesusr.com/ugd/14ee1a_40d2099ffe3e48a4a36862c76638fa1c.pdf (last accessed on 27 June 2021).

12. In February 2017, GLAN and FA submitted a complaint against Australia to the International Criminal Court concerning the potential commission of crimes against humanity as a result of the Australian government’s infamous offshore refugee detention centers in Nauru and Papua New Guinea. Moreover, in December 2018, GLAN and FA announced in a joint press conference the submission of another complaint to the UN Human Rights Committee, this time against Italy for illegal pushbacks of people on the move in the Mediterranean Sea towards Libya. For the joint press conference, see: https://www.glanlaw.org/nivincase (last accessed on 27 June 2021). Additionally, the two have collaborated further in the submission of a case against Italy to the European Court of Human Rights in 2019. For instance, see https://www.icj.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/ECtHR-SS_v_Italy_final-JointTPI-ICJECREAIREDCR-English-2019.pdf (last accessed on 27 June 2021).

13. For a well-known analysis of the decisive role of visual presentation and interpretation in this case, see Goodwin’s (Citation1994) “Professional Vision”.

14. See Logische Phantasie Lab’s homepage: https://lo-ph.agency (last accessed on 27 June 2020).

15. See NuLawLab’s homepage: https://www.nulawlab.org/ (last accessed on 27 June 2020).

16. For an example of seeing art as a matter of emotion vs. law as a matter of rationality, see Linderfalk (Citation2015).

17. See, for instance, Morgan (Citation2005).

18. See Sollfrank (Citation2011) for one such account of an art-directed enquiry into intellectual property laws and its examples of how “artistic practice can promote a subversion of ‘the law’” (362).

19. It is important to note that it can be somewhat difficult to speak of Forensic Architecture’s work as a singular body of work, as the group and its work has expanded greatly over the years and includes several offshoots and members working with a diverse range of topics and approaches.

20. In 2018, FA was nominated for Britain’s Turner Prize, and a year later one of its members, Lawrence Abu Hamdan, won the prize for his “earwitness” audio investigations, a component of which involved collaboration with Forensic Architecture and Amnesty International.

21. For example, Forensic Architecture (Citation2014), Weizman (Citation2017), Schuppli (Citation2020). See also the “Real Fictions” and other chapters in Foster (Citation2020) for further discussion of these themes in FA’s practice as well as other recent artworks and practices.

22. See Landres (Citation2021) for one account of this closing of the exhibition.

23. See IOM Missing Migrants Project available on IOM website: https://missingmigrants.iom.int (last accessed on 27 June 2021).

References

- Awan, N. 2016. “Digital Narratives and Witnessing: The Ethics of Engaging with Places at a Distance.” GeoHumanities 2 (2): 311–14. doi:10.1080/2373566X.2016.1234940.

- Benjamin, W., M. Jennings, B. Doherty, T. Y. Levin, and E. F. N. Jephcott. 2008. The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Boal, A. 1998. Legislative Theatre: Using Performance to Make Politics, Translated by A. Jackson. London: Routledge.

- Bois, Y.-A., M. Feher, H. Foster, and E. Weizman. 2016. “On Forensic Architecture: A Conversation with Eyal Weizman.” October 156: 116–140. doi:10.1162/OCTO_a_00254.

- Castellano, C. G. 2020. “Decentring the Genealogies of Art Activism.” Third Text 34 (4–5): 437–447. doi:10.1080/09528822.2020.1823723.

- Cover, R. 1983. “The Supreme Court, 1982 Term-Foreword: Nomos and Narrative.” Harvard Law Review 97 (4): 4–68. doi:10.2307/1340787.

- Crimp, D. 1988. AIDS: Cultural Analysis/Cultural Activism. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Dalaqua, G. H. 2020. “Aesthetic Injustice.” Journal of Aesthetics & Culture 12 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1080/20004214.2020.1712183.

- DeYoung, K. 2006. Soldier: The Life of Colin Powell. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

- Douzinas, C. 2008. “Subline Law: On Legal and Aesthetic Judgment.” Parallax 14 (4): 18–29. doi:10.1080/13534640802416819.

- Drumbl, M. 2020. “Staging Interntional Law’s Stories: Kapo in Jerusalem.” In International Law’s Collected Stories, edited by S. Stolk, and R. Vos, 37–55. London: Plagrave Macmillan .

- Epstein, S. 1998. Impure Science: AIDS, Activism, and the Politics of Knowledge. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Farocki, H. 2004. “Phantom Images.” Public 29: 12–22.

- Forensic Architecture, 2020. “About → Agency”. Website. https://forensic-architecture.org/about/agency Accessed 20 November 2020.

- Forensic Architecture. 2014. Forensis: The Architecture of Public Truth. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

- Forsyth, I. 2013. “Subversive Patterning: The Surficial Qualities of Camouflage.” Environment and Planning A 45 (5): 1037–1052. doi:10.1068/a44468.

- Foster, H. 2020. What Comes after Farce. London: Verso.

- Goodrich, P. 2009. “Screening Law.” Law & Literature 21 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1525/lal.2009.21.1.1.

- Goodwin, C. 1994. “Professional Vision.” American Anthropologist 96 (3): 606–633. doi:10.1525/aa.1994.96.3.02a00100.

- Gould, D. 2009. Moving Politics: Emotion and ACT UP’s Fight against AIDS. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Groys, B. 2014. “On Art Activism.” e-flux. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/56/60343/on-art-activism/ Accessed 15 February 2022.

- Hoffman, B. 1991. “Law for Art’s Sake in the Public Realm.” Critical Inquiry 17 (3): 540–573. doi:10.1086/448596.

- Jennings, R. 1967. General Course on Principles of International Law. Collected Courses of the Hague Academy of International Law, Vol. 21. The Hague: Brill.

- Keshavarz, M. 2018. The Design Politics of the Passport: Materiality Immobility and Dissent. New York: Bloomsbury.

- Khosravi, S. 2010. ‘Illegal’ Traveller: An Auto-Ethnography of Borders. Basingstoke: Plagrave Macmillan.

- Landres, S. 2021. “How Miami’s Museum of Art and Design Censored Forensic Architecture and Retreated from Social Justice.“ Hyperallergic. https://hyperallergic.com/624486/how-the-museum-of-art-and-design-censored-forensic-architecture-and-retreated-from-social-justice/ Accessed 15 02 2022.

- Leiboff, M. 2018. “Theatricalizing Law.” Law & Literature 30 (2): 351–367. doi:10.1080/1535685X.2017.1415051.

- Lindahl, H. 2013. Fault Lines of Globalization: Legal Order and the Politics of A-legality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Linderfalk, U. 2015. “Is Treaty Interpretation an Art or a Science? International Law and Rational Decision Making.” European Journal of International Law 26 (1): 169–189. doi:10.1093/ejil/chv008.

- Lippard, L. 1984. “Trojan Horses: Activist Art and Power.” In Art after Modernism,edited by B. Wallis, 341–358. New York: New Museum of Contemporary Art.

- Lorde, A. 1984. “The Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic as Power.” In Sister Outsider, edited by A. Lorde, 53–60. Berkeley: Crossing Press.

- Marronage. 2019. “The White Gaze within the Structure.” In Actualise Utopia: From Dreams to Reality , edited by N. J. Kulturrådet, 99–136. Oslo:Kulturrådet.

- Michael, V. A., K. Aidil Azlin Abdul Rahman, S. Fairs Abdul Shukor, and N. Azizi Mohd Ali. 2018. “An Analysis of Artists Practice in Hybrid Art and the Challenges toward Malaysian Art Scene.” Pertanika Journal of Scholarly Research Reviews 4 (2): 56–63.

- Morgan, E. 2005. “New Evidence: The Aesthetics of International Law.” Leiden Journal of International Law 18: 163–177.

- Ortiz, D. 2016. “Jus sanguinis.” Performed at Center for Art on Migration Politics, Copenhagen, 9 September.

- Ortiz, D. 2019. “This land will never be fertile for having given birth to colonisers” Performed at Virreina Centre de la Imatge, Barcelona, 23 November 2019-February 2020.

- Parsa, A. 2017. Knowing and Seeing the Combatant. War, Counterinsurgency and Targeting in International Law [Dissertation]. Lund: Media-Tryck.

- Rancière, J. 2004. The Politics of Aesthetics, Translated by G. Rockhill. London: Continuum.

- Reynolds, L. J., and S. F. Eisenman. 2013. “Tamms Is Torture: The Campaign to Close an Illinois Supermax Prison.” Creativetime.org. Accessed 15 February 2022.

- Schlag, P. 2002. “The Aesthetics of American Law.” Harvard Law Review 115 (4): 1047–1118.

- Schuppli, S. 2020. Material Witness: Media, Forensics, Evidence. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Sherwin, R. K. 2019. “Visual Literacy for the Legal Profession.” Journal of Legal Education 68 (1): 55–63.

- Sollfrank, C. 2011. Performing the Paradoxes of Intellectual Property: A Practice-led Investigation into the Conflicting Relationship between Copyright and Art [Dissertation]. Dundee: University of Dundee.

- Stabler, A. 2018. Legislative Art: Laurie Jo Reynolds and the Aesthetics of Punishment [Dissertation]. Urbana-Champaign: University of Illinois.

- Stark, D., and V. Paravel. 2008. “PowerPoint in Public: Technologies and the New Morphology of Demonstration.” Theory, Culture, and Society 25 (5): 30–55.

- Steyerl, H. 2014. “Beginnings.” e-flux. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/59/61140/beginnings/. Accessed 15 February 2022.

- Steyerl, H. 2015. “Duty-Free Art.” e-flux. https://www.e-flux.com/journal/63/60894/duty-free-art/. Accessed 15 February 2022.

- Stolk, S., and R. Vos. 2020. “International Legal Sightseeing.” Leiden Journal of International Law 33: 1–11.

- Tolstoy, L. 1996 [1897]. What Is Art? Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing Company.

- Virilio, P., and S. Lotringer. 2005. The Accident of Art, Foreign Agents Series. Cambridge, Mass: Semiotext(e).

- Vismann, C. 2008. Files: Law and Media Technology. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

- The Washington Post. 2021. “Closing Arguments in the Derek Chauvin Trial - 4/19 (FULL LIVE STREAM).” In. Youtube.

- Weizman, E. 2017. Forensic Architecture: Violence at the Threshold of Detectability. New York: Zone Books.

- Werner, W. 2019. “Moot Courts, Theatre and Rehearsal Practices.” In Backstage Practices of Transnational Law, edited by L. J. M. Boer, and S. Stolk, 157–173. London: Routledge.