ABSTRACT

For several decades now, audio-visual artworks have routinely been described as “research” or “research based”. However, the relationship between image, research and theory is often unclear, particularly when the artwork in question is produced outside formal academic frameworks like practice-based PhD or MFA programs. This essay asks how we can understand and interpret artworks that use materials and methods that approximate those used by academic researchers but do so through audio-visual means. Four artworks are discussed: Kajsa Dahlberg’s Reach, Grasp, Move, Position, Apply Force (2015); Kalle Brolin’s I am Scania (2016) and I am the Sun (2018); and Hanni Kamaly’s HeadHandEye (2017/2018). All four highlight how image practices establish, reinforce, and subvert specific attitudes, ideas, and practices relating to work or the human body. The author’s key argument is that the selected artworks can be understood as examples of the media-theoretical method of analysis known as cultural techniques. Cultural techniques have been defined within media theory as the chains of operations that link humans, things, and media. The scholar who uses this perspective searches for the rules, procedures, and documented practices that preceded and directed the development and formats of specific media technologies. This essay proposes that the four selected artworks show how fragmentation operates as cultural technique in different contexts. Fragmentation is shown to be at work beneath efficiency studies of industrial workers in the early twentieth century and the early twenty-first (Dahlberg); in the relationship between the sugar industry and coal mines in the south of Sweden in the early twentieth century (Brolin); and in the de-subjectification practices among colonial rulers in the nineteenth century (Kamaly).

In a filmed and transcribed conversation with Bernard Stiegler in the mid-1990s Jacques Derrida recounted how two of the students attending his seminar at a Californian university submitted videocassettes in place of the assigned written essay.Footnote1 Derrida told the students that although an image-based research output was acceptable in principle, it would need to include as much demonstrative and theoretical power as a good research paper. Having watched the submissions, Derrida felt unable to give the students a passing grade: “I did not refuse the image because it was the image”, he explained, “but because it had rather clumsily taken the place of what I think could have and should have been elaborated more precisely with discourse or writing”.Footnote2 Stiegler and Derrida speculate that a scholarly “practice of the image” that does not sacrifice rigour, differentiation, and refinement was likely to develop with new technological advances, and that various audio-visual and other image-practices may soon become part of a new “modality of the transmission of knowledge”.Footnote3 I think it is fair to say that we are still some distance away from such a shift in scholarly output despite the three decades that have passed since these pronouncements. But what about artistic work? I begin this essay with Derrida’s anecdote because of the way it highlights the potentially fraught relationship between image practices, research, and theory—a relationship that is central to many present-day artworks and therefore also to those of us who study them. For several decades now audio-visual artworks have routinely been described as “research” or “research-based”.Footnote4 At times, this refers to artworks that are part of practice-based PhDs, but the terminology is also frequently used for a more wide-spread set of practices, for example when artists use archival material in ways that propose or challenge historical narratives. My focus here is on the latter, i.e. artworks created without a clearly defined academic purpose, but that nevertheless refer to and resemble research in different ways.

I discuss three recent video artworks and a related lecture-performance that incorporate audio-visual elements. Kajsa Dahlberg’s Reach, Grasp, Move, Position, Apply Force (2015); Kalle Brolin’s I am Scania (2016) and I am the Sun (2018); and Hanni Kamaly’s HeadHandEye (2017/2018) all make extensive use of photography and film footage from the nineteenth and the early twentieth century. In these works, the historical material appears alongside other images, sound, and text elements in ways that draw explicit and implicit connections between the older images’ historical contexts, the ideologies they represent, and present-day debates, discourses, and concerns relating to labour conditions, the effects of tools and technologies on the bodies that use them, and processes of de-subjectification of the racialized body. There are obvious and crucial differences between arguments carried out and evaluated within an academic setting (like Derrida’s student submissions in California) and arguments carried out in artworks like these—for one, the latter do not have any necessary claims of veracity or verifiability. This, however, does not mean that such artistic-scholarly practices of the image cannot, in some cases, be productively analysed as audio-visual activations of methods and theories that were developed within traditional academic contexts. Such artworks may even exhibit a high degree of demonstrative and theoretical power as well as the rigor, differentiation and refinement that was seemingly lacking in Derrida’s students’ video works. Derrida’s remarks are a starting point for my discussion, but the theoretical framework I claim for my selected artworks is not one of deconstructive philosophy, but is rather tied to a particular branch of media theory. The key argument in this essay is that my four selected artworks, when read alongside one another and in light of other text and image material, can be understood as artistic examples of the media-theoretical method of analysis known as cultural techniques.

History by other means: cultural techniques as artistic methodology?

Developed within the field of German media studies, cultural techniques can be described as the chains of operations that link humans, things, and media.Footnote5 One of the methodological consequences of working with cultural techniques is that instead of considering a specific phenomenon in and of itself, the scholar tries to unearth the level below it by investigating the conditions and operations that made that kind of thinking possible in the first place, and whether these conditions and operations can also be found in other contexts or historical periods. Well-known implementations of this method have approached artifacts like doors, ships, grids, or legal paperwork as carriers of protocols, instructions, processes, and modes of usage that create complex operations of differentiation—between inside and outside; between land and sea; between mathematical, topographical, and governmental knowledge; and between jurisprudence and non-legal operations, respectively.Footnote6 Approaching historical analysis via cultural techniques can be seen to offer a productive path between two equally untenable positions as it eschews both the cynicism of techno-determinism and the naiveté of the view that human actors stand totally free from the objects and technologies we use.Footnote7 In a well-known formulation, Cornelia Vismann suggested that if we look at media theory as having a grammar, then cultural techniques would stand in for verbs since the focus is on the acts, or operations, that shape things and media.Footnote8 Geoffrey Winthrop-Young has described cultural techniques as “drills, routines, skills, habituations, and techniques, as well as tools, gadgets, artifacts, and technologies”.Footnote9 The scholar who uses this perspective search for practices that preceded and directed the development and formats of specific media technologies. Importantly, cultural techniques are not “just” acts and procedures in a general sense, but they are rather things that we do that have real epistemological consequences, linked to but not equated with specific technologies.Footnote10 For instance, the use of the grid to chart the land simultaneously structures knowledge and is a result of structures of knowledge that already exist, just like the operation of filing has consequences for knowledge production and memory in ways that is determined by technologies while also making certain technologies possible and viable in the first place.

I suggest that all four of my selected artworks show how fragmentation functions as such a basic operation. Each artist is concerned with somewhat different aspects of this operation, and the operation of fragmentation takes place in relation to different objects and historical contexts. For instance, there is fragmentation of the body (the breaking up of movement for the sake of efficiency or as sign of pathology or inferiority); fragmentation of space (gridded backgrounds that divide space into measurable units); and fragmentation of time (atomizing time into measurable units, and into work and leisure periods).Footnote11 I suggest that all four artworks examine how this basic operation had significant epistemological consequences at the turn of the twentieth century and how some of these consequences continue to play out in the current moment as well. By showing the effects of this basic operation at work in media technologies like photography and film, in conveyor belts, paternoster elevators, watches, grids, whistles, gates, guillotines, measuring devices and mirrors but also in management ideas, notions of work, the body, and broad ideological structures like colonialism, I argue that the artworks indirectly propose fragmentation as a cultural technique. It is precisely because the artworks reflect and make visible the interaction between imaging technologies and different knowledges that it is possible, and worthwhile, to analyze them as activations of cultural techniques.Footnote12 Prying open this broad methodological approach and its effects by focusing specifically on how it operates in four selected audio-visual artworks, is the aim of this paper.

I begin my discussion with Kajsa Dahlberg’s work. This section is the longest since it also lays the foundation for the discussion of the other three artworks.

Efficiency, work, and the moving image: Kajsa Dahlberg’s reach, grasp, move, position, apply force

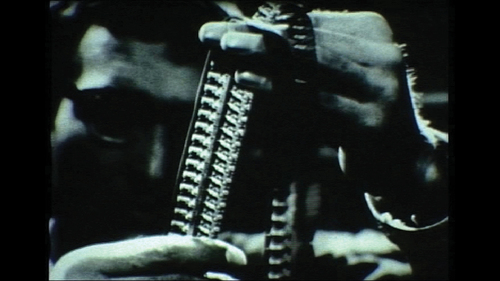

Kajsa Dahlberg’s 40-minute long video Reach, Grasp, Move, Position, Apply Force (2015) mixes historical footage with present-day accounts by representatives for time management practices, scholars, activists, factory workers and workers in Amazon warehouses. Running throughout the video are film sequences from Frank and Lillian Gilbreth’s efficiency studies carried out in the early decades of the twentieth century [. The soundtrack consists of Dahlberg’s interviewees and a female voice-over taken from the Gilbreths’ own promotional material. Since no separate narrator or explanatory intertexts are included, the viewer has to actively navigate the meaning of the different strands of the audio-visual material as it moves back-and-forth between different people and contexts and between present-day and historical material.

Figure 1. Kajsa Dahlberg, reach, grasp, move, position, apply force (2015), HD video, 40 minutes, 16:9. Images courtesy of the artist.

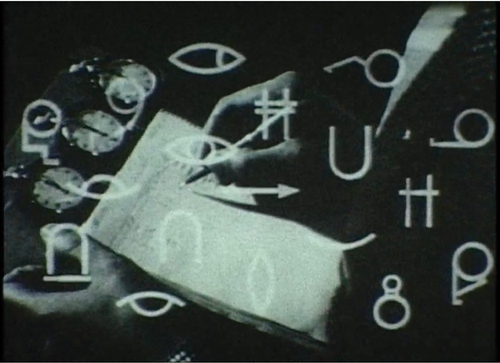

Over black-and-white footage showing hands, a clipboard and three clocks that fade into an image of what look like hieroglyphs [, the female voice declares:”The MTM system is based on the premise that all manual labour can be divided into separate basic movements. Every movement is assigned a predefined temporal value.”Footnote13 The story of the system’s origin is recounted by the Executive Director of the German MTM Association, interviewed by the artist. He describes how Frank Gilbreth in the very beginning of the twentieth century began careful study of bricklayers’ movements after noticing that their level of fatigue did not correlate to their productivity. After carrying out careful study of the bricklayers and numerous other professions, Gilbreth came up with a system where all manual work could be described in 18 predetermined movements that he claimed could be used to standardize and make industrial work more effective. The title of Dahlberg’s video, Reach, Grasp, Move, Position, Apply Force comes from five of the movements named within the MTM system, and the shown hieroglyphs are in fact shorthand symbols assigned to each movement. Immediately following the section that describes the MTM system and Gilbreth’s motion studies, the viewer is introduced to a present-day researcher specialized in the delivery industry. He describes how United Parcel Service (UPS) for decades has carried out “very intensive time and motion studies” in order to control their workers. Having first heard the account of how Gilbreth atomized all movement in order to achieve standardization and effectivization of work, the viewer is invited to conclude that today’s practices by UPS operate according to similar general principles. Dahlberg’s video brings up several other examples as well: workers in Asian electronics factories describe how their time is constantly monitored and workers at Amazon warehouses in different parts of the world recount how they are expected to pick 500 items per hour while managers and electronic devices supervise their work and ensure that quotas are met. A German academic complains about the increased levels of control of both lecturers’ and students’ time following the Bologna reform of higher education.

Figure 2. Kajsa Dahlberg, reach, grasp, move, position, apply force (2015), HD video, 40 minutes, 16:9. Images courtesy of the artist.

Workplace control, the study of time and movement and the precise measurement and classification of work in the early twentieth and early twenty-first centuries are the overt themes of Dahlberg’s video: this is what the artwork is about. But how does Reach, Grasp, Move, Position, Apply Force and the other audio-visual artworks examined in this essay deal with their overt topics and themes? What methods do they use to demonstrate to their viewers that there are complex links between different historical and present-day phenomena? And, more, specifically, how do these works propose fragmentation as an underlying operation of the different topics they set out to investigate?

Although the Gilbreths worked a great deal with photography, it is their work with film that is primarily shown and accounted for in Dahlberg’s artwork. Over footage of a man carefully studying a set of film strips [, the voice-over describes how films showing qualified workers performing specific tasks were “projected frame-by-frame, analysed and classified into a predetermined format of basic motions.” A subtext of Dahlberg’s video is how the turn of the twentieth-century marks both increasing control and standardization of industrial work and the emergence of the medium of cinema. The video argues that the two are intricately linked in numerous ways by exploring layers of connections between Gilbreth’s management practices and the image practices these built on, and by showing how these underlying processes of viewing and acting are developed into, expressed in, and made possible through the film medium itself.

Figure 3. Kajsa Dahlberg, reach, grasp, move, position, apply force (2015), HD video, 40 minutes, 16:9. Images courtesy of the artist.

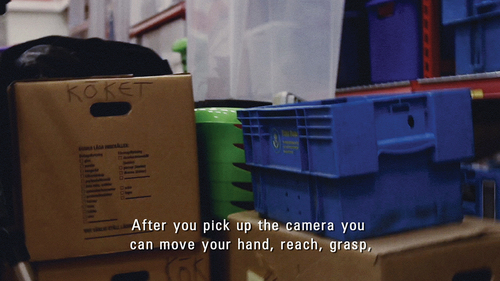

The opening of Reach, Grasp, Move, Position, Apply Force shows the well-known footage of workers leaving the Lumière factory in Montplaisir-Lyon in 1895, one of the very first films ever shot. When placed into Dahlberg’s video and its flow of images that deal with work and the breaking-up of time and movement, this historical footage hints at the underlying societal changes represented by this flow of people pouring out the factory gates. With industrialization time became sharply divided between work and leisure. No longer structured by seasonal changes or the rising and setting sun, industrial work broke time into increments that could be “spent” or “saved”; metaphors that point to temporal waste or profit since time was now standardized, atomized and possible to buy and sell. By opening with this well-known footage, the connection between the history of film and this newly cemented distinction between work and leisure is visualized. This intertwined history of controlling industrial workers on the one hand, and the development of visual media on the other, are shown to be at work also today. All the people that Dahlberg interviewed who describe working conditions and various forms of control mechanisms are in fact workers involved in producing or shipping the kind of equipment and services needed to make Dahlberg’s own artwork. They are workers in factories that make cameras and computers, drivers that deliver these goods, as well as academic researchers and translators who help analyse and contextualise the topic of the artwork. The very technology used by Dahlberg herself is thus highlighted as embedded in the same processes of temporal fragmentation that the artwork sets out to investigate. This is further highlighted when Dahlberg meets the Swedish training manager for the Nordic MTM Association who demonstrates their system of defining each work task according to a pre-determined set of micro-movements by using Dahlberg’s own camera, measuring and categorizing the different movements involved in taking a photograph and making a video [.

Figure 4. Kajsa Dahlberg, reach, grasp, move, position, apply force (2015), HD video, 40 minutes, 16:9. Images courtesy of the artist.

What do I mean when I claim that Dahlberg’s video makes visible the notion of fragmentation as cultural technique? I simply mean that this audio-visual artwork brings to light deeper operations that stretch over and beyond figures like the Gilbreths in the 1910s and 20s, or the individual workers or managers that implement or are subject to time management practices today. I argue that the artwork describes a set of operations that are connected to one another; that the basic operation of fragmentation is shown to shape media, technologies, and cultural expressions that made possible these specific instances, and that are in turn shaped by them. Consider for instance the film sequence from Gilbreth’s motion studies where a young woman is shown carrying out some kind of assembly work (see ). On one level, this is a study of the work carried out by the woman; timing, naming, and classifying each movement in order to improve it. This much is stated in the voice-over. But within Dahlberg’s video the edited film sequence also highlights this operation of fragmentation of time, movement, and space in other ways. Surrounding the woman’s work space are several clocks, set up not for her to look at, but to be recorded by the film camera. The mirror held up behind her visualizes the surveillance that was a key part of this system, but it also fractures the space of the image, drawing attention to the fact that the most important part of the working woman is her hands. When looking carefully at this image one notices that the mirror is held up by another pair of hands, but the man to whom they belong is only partly visible. Whereas the woman is important in the workplace as manual labour, however, the man is a manager and as such an all-seeing observer. Both are reduced to specific body parts: metaphoric and actual processes of fragmentation of hands and eyes, respectively. Yet another way that fragmentation is visually evoked in this image is the allusion to the division of space into measurable units by the gridded background and fabric draped across the woman’s work table. The Gilbreths used such gridded patterns in order to facilitate measuring the worker’s movements in their filmed or photographic documents. The point here is that a video artwork like Dahlberg’s Reach, Grasp, Move, Position, Apply Force, by selecting and putting together a number of different images, film footage, written documents, personal, official and fictive narratives can allow for various links and overlaps between different phenomena and practices to be discovered by the viewer. The different parts that make up the video become meaningful by the way they link to one another. Through these links fragmentation emerges as an object of study that that artist considers in a nuanced way without confronting the viewer with an overly didactic form of address.

The artworks analysed in this essay are not only visual objects. In addition to still and moving images they all also include discursive voice-over narratives and other sound and text elements. In the case of Reach, Grasp, Move, Position, Apply Force the discursive elements are made up of brief texts from the Gilbreth’s own promotional films, the female voice-over explaining the MTM system, a child reciting a text, accounts from the various interviewees and Dahlberg’s own comments and questions during the interviews. Throughout the video, the sound of a ticking clock recurs, as do images of the Gilbreths’ time-keeping devices, thus making audible and visible the division of time. Since many of the interviews were done over Skype, a present-day technological fragmentation of space is visualized in the screen-in-screen effect showing the interviewee talking to a smaller screen that shows the artist’s face. What unfolds through the layering of the visual, text, and audio elements like these, albeit not stated explicitly, is that audiovisual technologies, film, photography, and more recent video and digital communication technologies, are not only used to document and study workplace efficiency, but these image-technologies also operated and continue to operate in ways that align with the repeated, standardized movements that they document. According to the broad approach of cultural techniques, technologies always spring out of such basic operations, but they also simultaneously contribute to their continued effects. What Dahlberg’s video demonstrates, is that while film is what makes the operation of fragmentation visible (for example in the Gilbreths’ workplace studies), the medium also contributed, and continues to contribute to its ongoing implementation by newer technical media like video and digital tracking solutions such as those used by Amazon, UPS and in electronics factories around the world.

Dahlberg’s video hints at how the film medium also affected movements of bodies directly. Historical research into the Gilbreths has described how they edited their films by cutting out inefficient movements and then used the shortened film to show workers how they could make a particular work sequence more efficient.Footnote14 Another, less direct relationship is the associative connection between the projected image and the body in terms of the apparatus (camera or projector) as a machine. There is a scene around mid-way through Reach, Grasp, Move, Position, Apply Force that shows men walking one by one along a city street. They are World War One veterans who returned shell shocked from the front and the footage was taken in order to study their bodies as they tried to engage in the mundane mechanics of walking [. Over this scene, a child’s voice reads from Momo a book by Michael Ende about a different kind of time management than that carried out by the Gilbreths. Ende’s fantasy novel is about pockets of resistance against mysterious men in grey who suddenly arrive and begin to steal people’s time.Footnote15 In the very beginning of the video, Dahlberg interviewed a researcher in the field of machine vision who described studies of outward signs of malfunctioning movement—how present-day researchers use technologies to detect dementia or other cognitive issues in a microsecond of movement. The two scenes of the shell-shocked war veterans and the present-day scholar are separated by almost fifteen minutes but together suggest a connection through a “symptomatic” gaze—the idea that the outward signs of the body indicate mental states. Scholars have shown how this view was important for the study of mental illness at the turn of the century, as well as in racial sciences like eugenics, and Dahlberg’s video not only draws out a connection between this gaze and machine-learning systems and artificial intelligence a century later but also positions these in relation to different forms of time-management, surveillance and control mechanisms in the fictional world of Ende’s novel, within early twentieth-century efficiency studies, and through working conditions among delivery drivers and factory workers today.Footnote16 These are things that would seem to have little in common, but Dahlberg’s video reveals how fundamental epistemological operations of fragmentation link these different periods and contexts with one another.

Figure 5. Kajsa Dahlberg, reach, grasp, move, position, apply force (2015), HD video, 40 minutes, 16:9. Images courtesy of the artist.

What is striking about the filmed war veterans is that they do not have the fluid and continuous movement that characterizes healthy walking; and this give their gait a machine-like quality as though one movement is separated from the next by a brief gap, like a flickering film. The veterans who struggle to walk are reminiscent of Charlie Chaplin’s character in Modern Times (1936) one of the most well-known popular culture descriptions of time management. Modern Times brings up both the surveillance and control by visual technologies and the effects of industrial work on the human body. In the film, the factory manager views his workers on large screens from the comfort of his office, a kind of close-circuit TV system imagined well before its actual invention and common usage. In one scene, Chaplin’s character takes a break after a long stint of monotonous work at the assembly line. As he walks away from the belt, his body twitches in a mechanical jerky gait—the monotony of the assembly line has created tangible physical effects in the worker’s body, just like the effect of technologies of war created the mechanical movements in the shell-shocked veterans shown in Dahlberg’s video.

What I have tried to clarify in this section is how Kajsa Dahlberg’s artwork demonstrates how the operation of fragmentation is at work on several levels in the historical phenomena she examines, and how such operations also link this history to conditions and concerns in the present. Such operations of fragmentation are visualized in the machine-like locomotion of the soldiers and the described symptomatic movements of dementia patients; in how film as a medium is based on separate frames and methods of editing that draw together disconnected elements; and in the way that the management practices of the Gilbreths directly involved breaking up and reassembling worker’s movements.

The human motor and the miner’s squat: Kalle Brolin’s I am Scania & I am the Sun

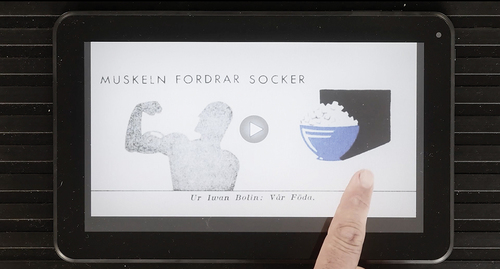

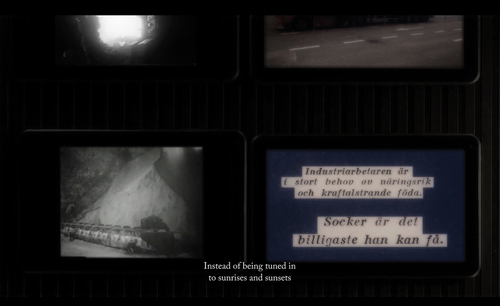

Kalle Brolin’s 23-minute video I am Scania is about the intertwined histories of coal mining and the sugar industry in the south of Sweden, and it deals directly with a set of practices designed to control and maximize energy input and output among workers in the early twentieth century. The opening images make the connection between the body and machinery explicit: an information pamphlet states that just as steam engines need coal, the human body needs sugar [. Different archival material, online image- and film databases and the voice-over by the artist describe various schemes to increase sugar consumption for workers: sugar was deemed an efficient and cheap energy source, particularly suitable for the lower classes. I am Scania includes repeated footage of the constantly-moving open-faced elevators known as paternoster. This device—similar to revolving doors—evokes the looped film, seamlessly moving without pause. Historically, the paternoster elevator represented a vision of the future in which the wheels of industry and capital keep turning day and night, a world-view that shaped the hope that sugar will prove to be a panacea for fatigue. The paternoster elevator is thus reminiscent of the assembly line: both operate on the principle that time should not be wasted on waiting or stopping. In both cases, the worker has to adjust to the pace of the machinery: be it a moving conveyor belt or a constantly revolving elevator. I am Scania reinforces this conceptual connection by the way that the video has been sound edited: throughout the video the sound of the clonking lift is used as the soundtrack to images showing the conveyor belt thus conceptually merging the two together in the viewer’s experience of the film.

Figure 6. Kalle Brolin, Jag är Skåne/I am Scania (2016), video, ca 23 min. Images courtesy of the artist.

The conveyor belt is used in Brolin’s film as an editing device: iPads showing still and moving imagery, photographs and documents are placed on a moving belt so that new footage is “edited together” when new iPads come into view and the old ones move out of the frame [. At times, this imagery fills our entire screen but often we see footage and still images on several iPads simultaneously as they move steadily past until they disappear from view. Workers are shown with their backs bent over while harvesting beets, at work in sugar factories and in coal mines, or enjoying time off. In I am Scania the editing process itself enacts the basic operation of fragmentation in the way that the digital images and their viewing technologies are only shown in extracts, short clips moving steadily across the screen, immediately replaced by another set of images, literally fragmenting the viewer’s experience of the visual material on view.

Figure 7. Kalle Brolin, Jag är Skåne/I am Scania (2016), video, ca 23 min. Images courtesy of the artist.

In a related work, the performative lecture I am the Sun (2018) the artist stands in front of a microphone on a large stage. This filmed performance took place in November 2018 at Moderna Museet in Stockholm, and incorporated two large screens with continuously shifting still images and filmed footage, a live gospel choir, and pieces of music played directly from the artist’s cell phone. During approximately 25 minutes, Brolin describes various aspects of the work in the sugar beet farms and mines in the region of Scania. The method used by the artist in this work also brings out perspectives that line up with the approach of cultural techniques. A key theme of Brolin’s lecture-performance has to do with the lingering traces of work on the working bodies, and the centrality of techniques in a broad sense. In 1934, the French anthropologist Marcel Mauss described what he called “body techniques” (techniques du corps), now often seen as a precursor to subsequent theorization of cultural techniques.Footnote17 Mauss claimed that the way people use their bodies was directly affected by technologies and traditions. Things that we find natural were actually historical: what he called “physio-psycho-sociological assemblages of series of actions.”Footnote18 One of the impulses for this theory was that Mauss had become aware that young women in Paris suddenly walked differently, something he attributed to the popularity of American cinema. Walking was thus not just a matter of physiology, gravity and kinetics; it involved chains of operations that linked ambulatory abilities to cultural protocols.Footnote19 Dahlberg’s shell-shocked veterans, and Chaplin’s mechanical gait are both examples of such bodily techniques, where cultural protocols, tools, and technologies cause bodies to move in mechanical—“unnatural”—ways. Although not a direct reference in these artworks, Mauss’ notion that the body is always intertwined with the tools, technologies and objects it uses, and the environments in which it operates, is implicitly present in both Dahlberg’s and Brolin’s artworks.

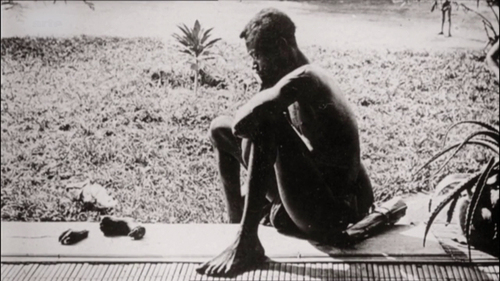

I am the Sun describes several such bodily effects. First, they appear in a poem cited by Brolin that recounts how children who grew up close to the coal mines would mimic the end-of-day-whistle, thus bringing the factory sounds into their bodies. A second example of a bodily technique is Brolin’s inclusion of images and verbal descriptions of the characteristic “miners’ squat” (gruvarbetarsits), a type of squat that was used in the cramped space of the mine.Footnote20 Brolin describes how at the day’s end the workers left work “but work did not leave them, it stayed in their bodies.” This lingering work was evident in their miners’ dirty faces and the dust they coughed up, but also in the way they moved and sat. Brolin describes how these workers continued to sit in the squatting position even during their leisure time when they no longer were constrained by physical space of the mine [. A third example that Brolin brings up in his artist-lecture is a program on the Swedish public service radio called “music during work” (Musik under arbetet). The artist explains that the program ran between 11 and 12 o’clock for two decades beginning in the mid-1940s. The broadcast time was the result of discussions with an industrial organization (industriförbundet) that claimed that production levels went down right around that time presumably due to the workers’ low blood sugar levels before lunch. The hope was that lively music could help speed up and energize work, as the music would cause the workers to forget their fatigue and continue to work at a fast pace. Historical footage and photographs of workers and people from villages where coal miners or sugar beet harvesters lived, poems and diaries as well as various official documents appear in the performance and the video, at times with precise references and citations, at times not. The effect is a rhythmic layering of language, footage, and texts that, again, draw out deep links between seemingly distinct historical phenomena and human stories.

Figure 8. Kalle Brolin, Jag är Solen/I am the Sun (2018), video recording of a lecture performance at Moderna Museet, Stockholm, ca 30 min. Images courtesy of the artist.

The footage from the Lumière factory that opened Dahlberg’s video makes an appearance in I am the Sun as well. Here, it is shown on the screens behind the artist as he reads the poem about how children mimicked the 4 o’clock whistle [. The whistle, like the opening of the factory gates marks the end of the working day, but through the different stories and materials Brolin brings up in his lecture, the delineation between work and leisure time, technology and body are shown to be continuously undermined. It is undermined in the miner’s squat, but also in the idea that sugar could overcome fatigue so that the miners could work continuously, unconcerned with the natural rhythm of day and night, work and rest. The poem recited by Brolin goes on to describe how the workers would pour out of the mine as though “thrown out of a bag”; they had to hurry, “the evening was so brief, the night so short, soon it was again early morning and then they had to be on their way again.” The rhythm of the poem mimics the churning of the machinery in a factory, the ever-moving paternoster elevator, but also the conveyor belt with its succession of iPads depriving the viewer of a prolonged engagement with any of the images steadily moving along. Again, I want to suggest that the format and methodology of these two audio-visual artworks reinforce the idea of fragmentation as a basic operation that structured work in different industries and agricultural sectors, but also directly affected the machines used, the bodies that carried out the work, their leisure activities, as well as the poetry they wrote and the music they listened to.

Bodily mutilation and racial oppression: Hanni Kamaly’s HeadHandEye

The fourth and final artwork that I want to discuss is a ca. 18 minute long video by Hanni Kamaly. HeadHandEye (2017/2018) deals with the history of physical mutilation—literal and symbolic—of the three body parts mentioned in the work’s title. The video draws direct associations between practices of mutilation and image practices related to these: ranging from antique sculptures, baroque paintings, death masks and ethnographic films to present-day cartoons, emojis, and digital image databases [. HeadHandEye includes many features that recall a traditional documentary: throughout the work a monotonous voice-over by the artist recounts factual information that explains and situates the historical and present-day visual material that makes up the video’s three chapters. The focus throughout is on different ways that bodies are separated into disparate parts, and how this process is used for subjugation, often based on racist ideologies. Towards the end of the video, the voice-over describes such severing of body parts as an inversion of the experience of the subject-as-a-whole, a notion that is tied to Jacques Lacan’s writing about the mirror stage and the connection between the seeing “eye” and the subjective “I”. Kamaly’s video can thus be described as a meditation on how operations of fragmentation are connected to processes of de-subjectification embedded in colonial practices of differentiation.

The first part of the video deals with hands: the symbolism of the hand, how the term is etymologically connected to labour, productivity, action, trade, friendship, control, resistance, and surrender: raise a hand, raise a fist, hands-up don’t shoot. One passage recounts how hands were cut off by Belgian colonial rulers if the local Congolese workers did not meet their quotas at the rubber plantations [. The narrator reflects: “Hands as a site for corporal agency, turn into tools of imperialism.”

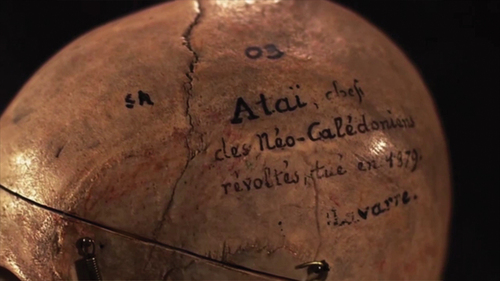

Kamaly’s video suggests that if the severing of hands rendered the amputee powerless and a living warning to others to work harder, the severed head is tied to ideological and philosophical ideas: the Enlightenment separation of mind and body, claims of the superiority of some races over others, the notion that intelligence, purity and goodness could be discerned from the shape of a skull. Key to HeadHandEye is establishing the ways in which various operations of fragmentation structures knowledge of the world, and how these have been tied to racist ideologies. One such direct connection is the use of heads and craniums by phrenology and eugenics in order to find “the answer of difference” between people and races. As the narrator describes this, the video shows collections of such heads from different ethnographic and science museums [, heads that were often taken from subjects who had dared to resist colonial rule—in Algeria, New Caledonia, and Ghana. As Elizabeth Edwards and others have shown, the preoccupation with measurement and quantification during the mid- and late nineteenth century coincided with a reconfiguration of the abstract concept of the “racial type” into something seemingly real and concrete.Footnote21

What Hanni Kamaly does in HeadHandEye is to show what scholars in different disciplines have pointed out in writing, namely that notions of racial superiority are embedded in complex structures that are key to understanding other, seemingly unrelated phenomena. For instance, Fatimah Tobing Rony has noted that Anthropology was fuelled by a desire to see difference and that it set up iconographies, like the background grid, for immediately recognizing difference, and to establish the ways in which the “primitive” was associated with a “pathological” counterpoint to the European.Footnote22 This general operation of taxonomic comparison was also evident in the broad interest at the end of the nineteenth century in categorizing and systematizing the knowledge of how to distinguish healthy from sick, and the delinquent from the law-abiding outlined by Allan Sekula and others.Footnote23 These attempts at efficient classification were enacted by image technologies at the time: in the mental hospitals, in police archives, in colonial administration, but also in industrial manufacturing work and in the coal mining industry. The Taylorite suggestions that the worker should function as an ever more efficient mechanical device is most clearly evoked by Dahlberg and Brolin, but it is also present in Kamaly’s HeadHandEye in the way that racist ideologies are shown to be based on ideas of the inefficient, faulty, or non-ideal body that needs to be transformed and subjugated for the sake of some implicit greater good. In all three artists’ works the modern subject is challenged by technologies that divide her up, for Kamaly, fragmentation is described as a literal existential threat to the very identity of those deemed to be other.

In HeadHandEye Kamaly juxtaposes different types of material and screen windows often appear layered within a larger screen [ as the artist’s voice-over moves freely from one topic to another. Here again, the artist’s method of editing through quick successions or layering of different types of sources, reinforces the sense of an underlying set of fragmenting operations that structure the seemingly very different image-practices, conditions and phenomena that Kamaly examines in her artwork.

Concluding discussion

I began this essay with a reference to the conversation between Jacques Derrida and his colleague Bernard Stiegler about the possibility of using audio-visual formats to communicate academic research. What exactly would it mean to take Derrida’s and Stiegler’s proposition seriously? What kind of research would benefit from such a format and what kind of institutional and infrastructural hurdles would need to be overcome for this to be a serious option in today’s academic eco-system? On the face of it, it makes a great deal of sense for scholars to make use of the full range of technologies, media and distribution channels available. It is also possible to imagine that what takes a scholar of history, aesthetics, philosophy, media studies or visual culture a great deal of time and space to describe in written text could be more effectively demonstrated in an audio-visual format. Whereas humanities could in principle use such methods, the strictures of academic output (journals, books, posters, lectures) means that the full potential of such media have not, so far, been utilized, even when the scholar’s subject matter and ideas could possibly benefit from them. Such media have, however, been used to great effect within the field of visual art. This essay has looked at how we can understand and interpret artworks that use materials and methods that approximate those used by academic researchers but that do so through audio-visual means.

Kajsa Dahlberg’s Reach, Grasp, Move, Position, Apply Force; Kalle Brolin’s I am Scania & I am the Sun; and Hanni Kamaly’s HeadHandEye all use montage of images, film footage, text and sound sourced from historical and contemporary material, factual documents as well as poems, novels and popular culture. For the viewer it is impossible to know what exactly is factual and what is not. That alone makes it clear that these are decidedly not research outputs in the same way that a peer-reviewed essay by a scholar in the humanities or social sciences would be research. But how, then, are they related to research? What are the points of intersection between image, theory and research in these particular audio-visual artworks? In this essay, I have tried to show two things. First that these four contemporary artworks can be understood in light of the media-theoretical method of analysis known as cultural techniques. And, second, that they indirectly also make visible important elements of this method. What the artworks do in audio-visual terms, by way of montage, editing or layering of material—bringing together cultural expressions from different periods and contexts with historical facts and archival documents—is similar to what is done in other ways by scholars who are working with more traditional media. Such scholars include Elspeth Brown, Mary Ann Doane, Elizabeth Edwards, Anson Rabinbach, Allan Sekula and Bernhard Siegert.Footnote24 Except for Siegert, none of these overtly align themselves with the terminology of cultural techniques, but their work can nevertheless be seen to share elements of its approaches to history writing. Dahlberg’s, Brolin’s and Kamaly’s works can be compared to these types of scholarly works in the sense that the artwork probes different types of materials (film and video footage, photographs, text, audio) for signs of operations that lie beyond, or underneath their most obvious or overt meaning. And, more specifically, that the particular themes that they process in their works—workplace surveillance and control (Dahlberg), consequences of the working conditions for sugar beet harvesters and coalminers (Brolin) and racist de-subjectification and oppression (Kamaly) all operate according to a logic of fragmentation—in corporeal, subjective, locomotive, temporal and spatial terms. All four artworks exemplify a method of drawing attention to the types of procedures and actions that give rise to ideological systems, technologies, media and image practices, and in that sense they also show that audio-visual art practice may well be particularly well suited to an analytical method that is interested in associations and connections between different phenomena, technologies and the subjects who make use of or are recorded by them.

It is important to stress here that I am not suggesting that Dahlberg, Brolin or Kamaly have set out to systematically analyse phenomena by way of cultural techniques—I have no evidence that they are interested in, or even familiar with, this rather specialized academic practice. What I am suggesting is that when these specific audio-visual artworks are considered in light of cultural techniques, we can deepen our understanding of the artworks’ explicit concern with the complexities of the relationship between knowledge, technology and images. These artworks exemplify and make visible the perspective of cultural techniques precisely in the way they show how historical phenomena can be described and understood in relation to various interlocking ideas, histories and technologies that all articulate and reinforce the basic operation of fragmentation. That they do so within a framework of contemporary artistic practice and by using audio-visual means can perhaps also help clarify how scholars of academic disciplines could make use of such media modalities within their own fields as well.

Acknowledgement

I want to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their comments on this essay. My work has been financed by the Swedish Research Council.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Jacques Derrida and Bernard Stiegler, Echographies of Television: Filmed Interviews, trans. Jennifer Bajorek (Cambridge, UK: Malden, MA: Polity Press; Blackwell Publishers, Derrida, Stiegler, and Bajorek Citation2002), 141–43.

2. Derrida and Stiegler, 143.

3. Derrida and Stiegler, 143, 141–42.

4. For a discussion of the topic of research-based installation (albeit not audio-visual artworks), see Claire Bishop, “Information Overload,” Artforum (blog), April 1, Citation2023, https://www.artforum.com/features/claire-bishop-on-the-superabundance-of-research-based-art-252571/. See also Hito Steyerl, “Aesthetic of Resistance?,” in Intellectual Birdhouse: Artistic Practice as Research, ed. Florian Dombois et al. (London: Koenig Books, Citation2012), 55–62.

5. Bernhard Siegert, “Cultural Techniques: Or the End of the Intellectual Postwar Era in German Media Theory,” Theory, Culture & Society 30, no. 6 Special Issue on Cultural Techniques (Siegert Citation2013): 48, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276413500828. I use the term medium/media in this essay in a fairly straight-forward way: either referring to the field of media studies, or else to refer to a medium like photography, film, video, etc.

6. Bernhard Siegert, Cultural Techniques: Grids, Filters, Doors, and Other Articulations of the Real, trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young, First edition, Meaning Systems, Volume 22 (New York: Fordham University Press, Citation2015); Cornelia Vismann, Files: Law and Media Technology, trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young, Meridian (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, Vismann Citation2008). The English translation is an abbreviated version of her published PhD dissertation published in German under the title Akten: Medientechnik und Recht.

7. Johan Fredrikzon, Kretslopp av data. Miljö, befolkning, förvaltning och den tidiga digitaliseringens kulturtekniker. (Lund: Mediehistoriskt arkiv, Fredrikzon Citation2021), 21.

8. Cornelia Vismann, “Cultural Techniques and Sovereignty,” Culture Theory & Society 30, no. 6 (Vismann Citation2013): 83, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276413496851. Cited in Siegert, Cultural Techniques, 11.

9. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young, “Translator’s Note,” in Cultural Techniques: Grids, Filters, Doors, and Other Articulations of the Real, by Bernhard Siegert, trans. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young, First edition, Meaning Systems, Volume 22 (New York: Fordham University Press, Winthrop-Young Citation2015), xv. It is worth noting that the German term Technik is significantly broader than the English “technique”, as Geoffrey Winthrop-Young notes when commenting on his translation of Bernhard Siegert’s book: its “semantic amplitude ranges from gadgets, artifacts, and infrastructures, all the way to skills, routines, and procedures” and thus could be translated as technique, technology or technics. Geoffrey Wintrop-Young’s”Translator’s note” in Siegert, Cultural Techniques, xv.

10. Fredrikzon, Kretslopp av data, 20.

11. For a perspective fragmentation from a perspective of cultural history, see Stephen Kern, The Culture of Time and Space, 1880–1918 (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, Citation2003); Philipp Blom, Fracture: Life & Culture in the West, 1918 – 1938 (Toronto: Signal, Citation2015).

12. The formulation is borrowed from Siegert who describes that it is the interaction between imaging technologies and different knowledges that turns the grid into a cultural technique. Siegert, Cultural Techniques, 98.

13. MTM stands for Methods-Time Measurement.

14. Elspeth H. Brown, The Corporate Eye: Photography and the Rationalization of American Commercial Culture, 1884–1929, Studies in Industry and Society (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, Brown Citation2005), 77.

15. The novel, published first published in 1973 had a lengthy sub-title in its original German that translates to Momo, or the strange story of the time-thieves and the child who brought the stolen time back to the people.

16. Joanna Lowry, “Projecting Symptoms,” in Screen/Space: The Projected Image in Contemporary Art, ed. Tamara Trodd, Rethinking Art’s Histories (Manchester, UK ; New York: Manchester University Press, Lowry Citation2011), 93–110; Felicia McCarren, “The ‘Symptomatic Act’ circa 1900: Hysteria, Hypnosis, Electricity, Dance,” Critical Inquiry 21, no. 4 (Summer McCarren Citation1995): 748–74; Brown, The Corporate Eye; Georges Didi-Huberman, Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, Citation2003); Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (Durham: Duke University Press, Citation2015). For a direct meditation on the relationship between Gilbreths and AI generated systems, see “PATTERNS OF LIFE by Julien Prévieux—YouTube,” accessed October 5, Citation2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c45IfGRkJ_w.; Grégoire Chamayou, “Patterns of Life,” in Nervous Systems: Quantified Life and the Social Question, ed. Anselm Franke, Stephanie Hankey, and Marek Tuszynski, Haus Der Kulturen Der Welt and Tactical Technology Collective (Leipzig: Spector Books, Citation2016), 194–203. I discuss this work in a forthcoming text (in Swedish): “Fotografiska rörelsestudier och det effektiva arbetets ikonografi” in the anthology Lära om fotografi edited by Henrik Andersson.

17. Marcel Mauss, “Techniques of the Body [1934/1968],” Economy and Society 2, no. 1 (Mauss Citation1973): 70–88, https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147300000003.

18. Mauss, 82–83, 85.

19. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young, “Cultural Techniques: Preliminary Remarks,” Theory, Culture & Society 30, no. 6 Special Issue on Cultural Techniques (Winthrop-Young Citation2013): 10, https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276413500828.

20. Note too that Marcel Mauss writes about squatting in his text about bodily techniques, see Mauss, “Techniques of the Body [1934/1968],” 77.

21. Elizabeth Edwards, “Photographic ‘Types’: The Pursuit of Method,” Visual Anthropology 3, no. 2–3 (Citation1990): 240, https://doi.org/10.1080/08949468.1990.9966534. See also Edwards, 241. For a key text and exhibition on the relationship between anthropology and photography, see Melissa Banta et al., From Site to Sight: Anthropology, Photography, and the Power of Imagery, Thirtieth Anniversary Edition (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Peabody Museum Press, Harvard University, Citation2017).

22. Fatimah Tobing Rony, The Third Eye: Race, Cinema, and Ethnographic Spectacle (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, Rony Citation1996), 32, 27.

23. Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” October 39 (Winter Sekula Citation1986): 3–64. The idea that taxonomy and ordering was tied to photographic practice nearly from its inception was examined in the exhibition In Visible Light (1997). See Russell Roberts and Chrissie Iles, eds., In Visible Light: Photography and Classification in Art, Science and the Everyday, Exhibition Catalogue: Museum of Modern Art Oxford (Touring Exhibition In Visible Light: Photography and Classification in Art, Science and The Everyday, Oxford, Citation1997).

24. See for instance: Brown, The Corporate Eye; Mary Ann Doane, The Emergence of Cinematic Time: Modernity, Contingency, the Archive (Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, Citation2002); Elizabeth Edwards, “Ordering Others: Photography, Anthropologies and Taxonomies,” in In Visible Light: Photography and Classification in Art, Science and the Everyday, ed. Russell Roberts and Chrissie Iles, Exhibition Catalogue: Museum of Modern Art Oxford (Touring Exhibition In Visible Light: Photography and Classification in Art, Science and The Everyday, Oxford, Citation1997), 54–68; Anson Rabinbach, The Human Motor: Energy, Fatigue, and the Origins of Modernity (Berkeley: University of California Press, Citation1992); Sekula, “The Body and the Archive”; Siegert, Cultural Techniques.

References

- Banta, M., C. M. Hinsley, J. Kathryn O’Donnell, and I. Jacknis. 2017. From Site to Sight: Anthropology, Photography, and the Power of Imagery. Thirtieth Anniversary ed. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Peabody Museum Press, Harvard University.

- Bishop, C. “Information Overload.” Artforum (blog). April 1, 2023. https://www.artforum.com/features/claire-bishop-on-the-superabundance-of-research-based-art-252571/.

- Blom, P. 2015. Fracture: Life & Culture in the West, 1918 - 1938. Toronto: Signal.

- Brown, E. H. 2005. The Corporate Eye: Photography and the Rationalization of American Commercial Culture, 1884-1929. Studies in Industry and Society. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Browne, S. 2015. Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Chamayou, G. 2016. “Patterns of Life.” In Nervous Systems: Quantified Life and the Social Question, edited by A. Franke, S. Hankey, and M. Tuszynski, 194–13. Leipzig: Haus Der Kulturen Der Welt and Tactical Technology Collective: Haus Der Kulturen Der Welt and Tactical Technology Collective.

- Derrida, J., and B. Stiegler Jennifer Bajorek, Translated by. 2002. Echographies of Television : Filmed Interviews. Cambridge, UK, Malden, MA: Polity Press; Blackwell Publishers.

- Didi-Huberman, G. 2003. Invention of Hysteria: Charcot and the Photographic Iconography of the Salpêtrière. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

- Doane, M. A. 2002. The Emergence of Cinematic Time: Modernity, Contingency, the Archive. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

- Edwards, E. 1990. “Photographic ‘Types’: The Pursuit of Method.” Visual Anthropology 3 (2–3): 235–258. 10.1080/08949468.1990.9966534.

- Edwards, E. 1997. “Ordering Others: Photography, Anthropologies and Taxonomies.” In In Visible Light: Photography and Classification in Art, Science and the Everyday, In Visible Light: Photography and Classification in Art, Science and the Everyday, edited by R. Roberts and C. Iles, 54–68. Oxford.

- Fredrikzon, J. 2021. Kretslopp av data. Miljö, befolkning, förvaltning och den tidiga digitaliseringens kulturtekniker. Lund: Mediehistoriskt arkiv.

- Kern, S. 2003. The Culture of Time and Space, 1880-1918. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

- Lowry, J. 2011. “Projecting Symptoms.” In Screen/Space: The Projected Image in Contemporary Art, edited by T. Trodd. Manchester, UK; New York: Manchester University Press, 93–110. Rethinking Art’s Histories.

- Mauss, M. 1973. “Techniques of the Body [1934/1968].” Economy and Society 2 (1): 70–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/03085147300000003.

- McCarren, F. 1995. “The ‘Symptomatic Act’ Circa 1900: Hysteria, Hypnosis, Electricity, Dance.” Critical Inquiry 21 (4): 748–774. https://doi.org/10.1086/448773.

- “PATTERNS OF LIFE by Julien Prévieux - YouTube.” Accessed October 5, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c45IfGRkJ_w.

- Rabinbach, A. 1992. The Human Motor: Energy, Fatigue, and the Origins of Modernity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Roberts, R., and I. Chrissie, eds. 1997. Visible Light: Photography and Classification in Art, Science and the Everyday. Exhibition Catalogue: Museum of Modern Art Oxford. Oxford.

- Rony, F. T. 1996. The Third Eye: Race, Cinema, and Ethnographic Spectacle. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Sekula, A. 1986. “The Body and the Archive.” October 39:3–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/778312.

- Siegert, B. 2013. “Cultural Techniques: Or the End of the Intellectual Postwar Era in German Media Theory.” Theory, Culture & Society 30 (6): 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276413488963.

- Siegert, B. 2015. “Cultural Techniques: Grids, Filters, Doors, and Other Articulations of the Real.” In Meaning Systems, edited by G. Winthrop-Young, First ed. Vol. 22. New York: Fordham University Press.

- Steyerl, H. 2012. “Aesthetic of Resistence?.” In Intellectual Birdhouse: Artistic Practice as Research, edited by F. Dombois, U. M. Bauer, C. Mareis, and M. Schwab, 55–62. London: Koenig Books.

- Vismann, C. 2008. Files: Law and Media Technology. Translated by Geoffrey Winthrop-Young. Meridian. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press.

- Vismann, C. 2013. “Cultural Techniques and Sovereignty.” Culture Theory & Society 30 (6): 83–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276413496851.

- Winthrop-Young, G. 2013. “Cultural Techniques: Preliminary Remarks.” Theory, Culture & Society 30 (6): 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276413500828.

- Winthrop-Young, G. 2015. “Translator’s Note.” in Cultural Techniques: Grids, Filters, Doors, and Other Articulations of the Real, by Bernhard Siegert, Xv. Translated by Geoffrey Winthrop Young.” In Meaning Systems, 1st ed. Vol. 22. New York: Fordham University Press.