ABSTRACT

In this article we propose a case selection strategy for comparative studies of school improvement. The strategy is based on two assumptions. First, we emphasize the importance of a strategic selection of cases (schools), which allows systematic comparisons between successful and failing schools. We claim that cases should be selected on the dependent variable, and, more specifically, on the variation in the dependent variable (i.e. school success or no school success). Second, we recognize the importance of a longitudinal perspective in the case selection process. We argue that quantitative longitudinal data should be used to identify consistently succeeding and consistently failing schools. Furthermore, we demonstrate the fruitfulness of the strategy by using it in a case selection process of successful and failing schools in Sweden. In sum, the strategy addresses the demand for research designs, which allow causal inference, in school improvement and school effectiveness studies. Systematic comparisons between successful and failing schools are essential to elaborate our insights of the mechanisms behind school success.

Introduction

In this article we propose a case selection strategy for studies of school improvement. Essential to our argument is the assumption that in order to investigate phenomenon in school improvement and to develop theoretical understandings of these phenomena it is of uttermost importance to compare successful and failing schools. Therefore we outline a case study design using an indirect method of difference (Mill Citation1967) selecting cases (by cases we refer to schools) based on student outcome. Also, we demonstrate the fruitfulness of this strategy by using it in a case selection process of successful and failing schools in Sweden.

We agree with Frank Cofield who commented on methodological problems of policy reports on how to improve educational systems by stating that the basic weakness is the lack of comparisons between improving and non-improving systems. In a Swedish radio program addressing these issues (Konsulterna som styr skolpolitiken Citation2015), Frank Cofield stated: “If you want to claim that certain policies are more successful than others you would have to look at successful systems and non-successful systems and say here are the policies that work in successful systems, and here are the policies but they don’t work in the non-improving systems”. If features pointed out as important are used in most educational systems, then there is no evidence that these are the ones that would lead to success.

This article is the first of two involving a project investigating the impact of schools’ internal organization on student outcomes. Causes of variation in student performance between schools due to factors and processes associated with the internal organization of schools are receiving growing attention in the fields of school improvement and school effectiveness (Hopkins et al. Citation2011; Reynolds et al. Citation2011). This article makes an important contribution by using an indirect method of difference (Mill Citation1967) comparing the inner life of consistently successful and consistently failing schools. We argue that the cases should be selected from longitudinal data on the dependent variable, which is student outcome. Setting this type of high demand, we outline a systematic case selection strategy—paving the way for the next part of the study as well as for future case studies of school improvement and aiming to explain why some schools produce better results than others.

This article is structured as follows. First, we briefly outline the methodological strengths and weaknesses of research on school improvement and school effectiveness. We argue that case studies based on a strategic selection of cases hold the key to making causal inferences between different factors of effectiveness and student outcomes. Second, we discuss recent trends in the Swedish educational system and why Swedish education provides good conditions for the use of the case selection strategy proposed in the article. Third, we present the case selection strategy in more detail. We discuss the operationalization of the dependent variable and identify control factors that enable a strategic selection of cases. Fourth, we demonstrate the use of the strategy by selecting four of the most successful and four of the most unsuccessful schools in Sweden. Finally, we conclude our arguments and discuss the implications of the case selection strategy in the context of comparative case studies of school improvement.

Theory and previous research

Although many countries seek an equitable educational system, they face a reality where schools produce different results. Understanding the causes of variation in student performance between schools has become a priority among researchers in the fields of school improvement and school effectiveness (Hopkins et al. Citation2011). Especially, there is an increasing body of literature looking into the importance of factors and processes associated with the internal organization of schools (Hopkins et al. Citation2011; Kyriakides Citation2007; Reynolds et al. Citation2011; Teddlie and Reynolds Citation2000). It is acknowledged that the internal organization can play a decisive role on student performance regardless of the student’s individual background, such as parents’ educational level or home conditions. This is an encouraging line of thought as it signals the possibility of affecting students’ outcomes through informed and conscious decisions.

As the internal organization of schools receives growing attention, so does the need of developing the theoretical foundations of school improvement and school effectiveness studies (Creemers et al. Citation2000; Lincon and Guba Citation2000; Bogotch, Mirón and Biesta Citation2007; Gustafsson and Myrberg Citation2002; Kyriakides et al. Citation2010; Rothstein Citation2012; Townsend and MacBeath Citation2011). “What is missing”, argue Bogotch et al., “is a deeper understanding–or at least an attempt to understand–how different variables interact inside the ‘black box’” (2007, 98).

School improvement research (SIR) has played a crucial role in deepening our understanding of what drives improvement processes at the local school level. SIR research has mainly focused on generating “thick” descriptions of schools using case study approaches, thereby providing contextually embedded “stories” of the importance of different factors (Bogotch, Mirón and Biesta Citation2007; Reynolds et al. Citation2011; Teddlie and Sammons Citation2010). However, SIR research often lacks generalizability. “Stories” of some schools are not contrasted to “stories” of other schools, making it hard to determine whether observed factors and processes are unique to a particular school setting or valid in school settings in general.

Some of these problems are addressed in school effectiveness research (SER) where we witness a domination of large-scale quantitative methods to identify and measure differences in school effectiveness. SER research has contributed to a general understanding of different factors associated with school effectiveness by isolating explanations for observed outcomes using statistical analyses. However, SER research also faces specific weaknesses, the most important being that explanations of why and how these factors matter to school effectiveness are not explicitly outlined (Bogotch, Mirón and Biesta Citation2007; Creemers, Kyriakides, and Sammons Citation2010). Another weakness is that it is problematic to demonstrate causality when using cross-sectional data, which is often the case in school effectiveness research (Creemers and Kyriakides Citation2010; Kyriakides Citation2007; Creemers, Kyriakides and Sammons Citation2010).

We argue that the present state of school effectiveness and improvement research can be described as a paradox. On the one hand, school effectiveness research has been criticized for continuing to rely too heavily on the interpretation of findings that do not explicitly describe change and improvement in schools (see for example Barth Citation1986; Hallinger and Henck Citation2011). On the other hand, case studies describing close up school ‘turn around’, or day-to-day efforts to improve schools in specific contexts, are considered of limited value as case study findings often lacks generalizability. Hallinger and Henck (Citation2011, 2) have pointed to the fact that “a knowledge base from case studies alone will be both laborious and of limited validity and utility”.

The overarching aim of most studies in the fields of school effectiveness and school improvement is to make causal inferences between different factors of effectiveness and student outcomes. However, school effectiveness and school improvement research have been criticized for not trying hard enough to deal with causal direction in research designs (Nordenbo et al. Citation2010; Gustafsson Citation2013). Quantitative studies using cross-sectional data that investigate correlations, not causality, and qualitative case studies in the form of outlier studies investigating schools with exceptional student achievements dominate the field (Nordenbo et al. Citation2010). As the gold standard of research designs for making causal inferences, experimental research is seldom applicable to school effectiveness and school improvement research, and thus we need other options.

Despite its shortcomings, we argue that case study design holds advantages for making descriptions of what occurs during efforts to improve schools. When one cannot fully control for factors that might interfere with the observed relationship between outcomes and causes, the possibility of clarifying mechanisms mediating the effect provided by case studies is of huge importance. To understand the causal mechanisms in internal school organization, case studies are a superior research method (George and Bennett Citation2004; Teorell and Svensson Citation2010). In the search for variables explaining school success, close-up studies of decision-making processes and patterns of action and interaction in schools are preferable (Cohen, Manion and Morrison Citation2006; Hitchcock and Hughes Citation1995; Nisbet and Watt Citation1984) and needed (Yin Citation2009). By intensively studying the deviant schools, we might provide significant theoretical insights (George and Bennet Citation2004). Results generated from the case studies could then be transformed into hypotheses whose generalizability should be tested using large-scale quantitative methods.

However, a basic condition is a strategic selection of cases which allow for systematic comparisons. Systematic comparisons have rarely been the case in school improvement studies, which has led Harris (Citation2006) and Jackson (Citation2000) to conclude that outlining basic principles for case selection is an important improvement area. As an example, Ainscow and Chapman (Citation2005) studied leadership and organizational impact in turn-around schools during particular improvement initiatives without comparison with non-turning-around schools. There are also examples of studies of processes and actions of failing schools without comparisons with successful schools (Nicolaidou and Ainscow Citation2005; Ainscow and Howes Citation2007).

Looking at comprehensive Scandinavian projects, the same pattern is observed. For example in a large study by Johansson and Höög (Citation2010) investigating the relationship between structure, culture, and leadership as preconditions for successful schools, 24 Swedish schools were investigated. It is, however, unclear why these particular 24 schools were selected, making the analysis and results unspecific (Höög, Johansson, and Olofsson Citation2005, Citation2009; Johansson and Höög Citation2010).

We argue that case selection in comparative school improvement studies should be designed based on two basic assumptions. First, we emphasize the importance of comparisons between successful and failing schools. We argue that cases should be selected on the dependent variable, and, to put it more specifically, on the variation in the dependent variable (i.e. school success or not school success). Second, we recognize the importance of a longitudinal perspective in the process of case selection as well as in the empirical search for explanatory factors and mechanisms within the selected schools. Taken together, this article outlines a case selection strategy using quantitative longitudinal data to identify consistently succeeding and consistently failing schools.

Recent trends in the Swedish education system

The use of the proposed case selection strategy for comparative case studies on the role of schools’ internal organization presupposes an educational system where individual schools have discretion and a mandate to decide on their own organization, and where there is variation between schools in terms of outcome. The Swedish educational system provides good conditions for these conditions to be met. It is to be noted that previous research has shown that the variability between student outcomes is higher in countries with organizationally differentiated school systems (Van der Werfhorst and Mijs Citation2010).

During the last decades, the former Swedish educational system—characterized as a centralized educational system where the state directly governed individual schools in accordance with the social democratic heritage and the notion of a strong state—has been changed (Blossing, Imsen and Moos Citation2014). Swedish education may still appear to be more cohesive than other systems due to the presence of, for instance, a national curriculum, national tests, and a school inspectorate. Decentralization and new public management reforms that were introduced during the early 1990s have, however, distributed decision-making power from the national to the municipal and local levels as well as to independent producers of education, that is, independent schools, substantially increasing the level of differentiation in the educational system compared to two decades ago (Jarl, Fredriksson and Persson Citation2012; Lundahl Citation2002). The share of students of compulsory school age that attend independent schools has increased dramatically: from about five percent in the academic year 2001/02 to 13 percent in the academic year 2011/12 (Skolverket Citation2012a).

In parallel, the variation between schools in terms of student outcomes–what we refer to as “between school variation”–has grown dramatically (Böhlmark and Holmlund Citation2011; Gustafsson and Yang Hansen Citation2011; Skolverket Citation2012b). There has, during the last decade, been an increase in the variation between schools while, at the same time, differences within individual schools have decreased. We have witnessed a homogenization of individual schools while the differences between individual schools have increased (Skolverket Citation2012b). Studies also show that the between-school variation increase is most apparent in large city areas (Skolverket Citation2012b; Gustafsson and Yang Hansen Citation2011). Thus, understanding what processes go on in metropolitan areas and how these processes relate to school success is a very important task for future research (Gustafsson and Yang Hansen Citation2011). According to Gustafsson and Yang Hansen, the high level of competition among schools in metropolitan areas could be a factor of special importance (Citation2011). The share of students that attend independent schools is larger in metropolitan areas–about 23 percent–than in Swedish municipalities on average–13 percent (Skolverket Citation2012a). Understanding the mechanisms by which competition affects the increase in between school variation is thus a research task of special importance.

Focusing on Sweden also gives us the opportunity to use an exclusive dataset: Gothenburg Educational Longitudinal Database (GOLD). As GOLD contains information on all individuals born between 1972 and 1995 who were registered in Sweden at the age of 16, it provides the possibility of identifying schools with stable patterns (over a 14-year period, 1998-2011) concerning the development of student outcomes over time. The case selection from longitudinal data, where schools are selected based on their continuous development of student results, is considered a deficit in the literature (Creemers and Kyriakides Citation2010; Kyriakides et al. Citation2010; Kyriakides Citation2007).

Next we present the case selection strategy in more detail. First, we discuss the operationalization of the dependent variable, arguing that student grades are the most reliable way to define school success. Also, we identify control factors that enable a strategic selection of schools. Second, we present the process of case selection using the proposed strategy. We describe the GOLD data and the statistical model used for case selection more closely, as well as the validation process for identifying the final eight schools (four consistently succeeding and four consistently failing).

Defining and measuring the dependent variable

There are different understandings in the literature on how to measure school effectiveness, although most scholars argue that student outcomes should be involved and that cognitive outcomes, such as student grades or results on national tests, are the most valid effectiveness criteria (Bogotch, Mirón and Biesta Citation2007; Hopkins Citation2001; Reynolds et al. Citation2011). However, there is an increasing awareness that non-cognitive outcomes could be relevant to include (Gray Citation2004; Höög Citation2010; Reynolds et al. Citation2011; Walford Citation2002). As an example, on occasion, the quality of student learning is seen as something that should be included in the definition (Bogotch, Mirón and Biesta Citation2007; Trupp Citation2002; Pring Citation2000).

We focus on cognitive student outcomes. More precisely, we are interested in students’ total achievement in their first nine years of compulsory school. By looking at the sum of ninth graders’ grades, we can review the schools’ performance concerning student outcomes: that is, we argue that student outcomes should be limited to the “output” side of the school system. The reason for not including the quality of student learning in the definition of student outcomes is that these aspects empirically may be a part of what we want to explain (Bogotch, Mirón and Biesta Citation2007; also compare Creemers, Kyriakides and Sammons Citation2010). For example, there are currently tracks of research in the school improvement literature aiming to enhance students’ learning as well as those aiming to improving the schools’ capacity for managing changes—so-called “authentic school improvement” (Hopkins Citation2001; Hopkins and Reynolds Citation2001). The main problem with these studies, as we see it, is that what is defined as the improvement is very close to what the program intends to achieve.

However, in Sweden the validity of student grades as a measure of student outcomes is sometimes debated (Böhlmark and Holmlund Citation2011; Gustafsson and Yang Hansen Citation2011; Höög Citation2010; Gustafsson, Cliffordsson and Ericksson Citation2014). The existence of grade inflation— that is, that grades increase at a national level while, at the same time, results on national or international tests do not improve—is troubling researchers primarily because grade inflation is a complicated variable to control for. In the next section we will present a technique to test the relative grade inflation in our sample of schools, dealing with the problem although not solving it.

Data

Understanding the nature of school effectiveness is a complex task. Although we know that schools have effects on student outcomes, we also know that these results are affected by factors outside of the schools. There is an ongoing debate in the literature of school effectiveness concerning what kind of internal and contextual factors are appropriate to control for when looking at differences in student outcomes at the school level (Böhlmark and Holmlund Citation2011; Gustafsson and Yang Hansen Citation2011). We argue that a suitable statistical model categorizing successful and failing schools should focus on student composition regarding education background and the students’ migration background.

There are at least two arguments that make a restrictive selection of control variables to the statistical model a suitable posture. First, since we are interested in internal school factors we have to be careful not to control for possible school organizational factors in the quantitative analysis. School organizational aspects like how schools handle and optimize their teachers’ competencies may be a part of the processes and interventions we want to understand.

Second, besides the two variables of education background and migration background, there is little agreement or consistency in the literature concerning what contextual factors affect student outcomes (Böhlmark and Holmlund Citation2011; Gustafsson and Yang Hansen Citation2011). When it comes to contextual factors, the literature presents two usual suspects and a lot of vague traces. To conclude, we stick to the usual suspects, making the model moderately simple.

The GOLD database compiles information from many different sources, taking advantage of the fact that in Sweden registry data is stored with a personal identification number. A key population component of GOLD is registry data for all cohorts born between 1972 and 1995 and registered in Sweden at the age of 16. For each individual there is information concerning family background and school achievement: grades from compulsory school and merit rating (calculated from the best 16 grades for each individual student in the ninth grade, the maximum rating is 320). GOLD also includes information about all primary schools in Sweden such as how many students the school has, if it includes all grade levels, when the school started, and if the school has been closed.

Selecting a sample of cases

The data analysis included three phases. In the first phase of the statistical analysis we used Ordinary least squares regression (OLS regression). By making 2,081 OLS regressions, one for each primary school, we investigated whether the student outcomes, measured as mean merit rating, at the school level increased or decreased during the fourteen-year period from 1998 to 2011. Separate analyses were conducted for each school, with the number of years (14) as the number of observations, the merit rating as the dependent variable.

In the model we included two control variables: student education background and migration background. To provide a control of possible changes in the student composition at the schools we estimated change in the proportion of students over time by comparing the proportion of students the last year 2011, with the first year 1997. The educational background was measured by a trichotomous variable categorizing students’ parents’ level of education. At least two years of university studies was categorized as high educational background (2), less than two years of university studies but nine or more years of primary- and secondary school as medium (1) and others as low (0). The migration variable was dichotomous, categorizing students not born in Sweden or with both parents born outside Sweden as immigrants (0) and others as not immigrants (1). Adopted students or those with parents working abroad were categorized as not immigrants.

Regarding the issue of whether the schools could exhibit different levels of grade inflation a test were made using another measure of student outcome. Instead of mean merit rating we used a measure of the percentile equivalence merit rating (grouped on graduate year). This test showed the same results as when using mean merit rating, i.e. grade inflation did not seem to be a key explanation for the trends in the schools. Based on this test it is, however, difficult to completely rule out that there are differences concerning grade inflation between schools, and yet we lack external measurements concerning this issue. Although grades are the most reliable operationalization of school success the existence of grade inflation is troubling researchers. In the case of Sweden there is, however, a general understanding that the degree of grade inflation is smaller in primary than in secondary schools where the competition among schools is higher (Gustafsson & Yang Hansen Citation2011).

In the second phase we made a selection from the 2,081 schools in the GOLD database. We were only interested in primary schools that were active during the entire time period and are still active. Further, the sample would only include schools with all grade levels from year one to year nine. We also wanted to make sure that our sample exclusively included schools of a certain size. We included schools that had at least 12 students in the first grade and at least 224 (25 students in each grade level) students in total during all 14 years analyzed. These constraints made a sample of 364 schools.

In the third phase we matched the 364 schools with the results from the OLS regression analysis. We sorted schools from most successful (continuous improvement in student outcomes over 14 years) to most failing (continuing negative outcomes over the 14 years). In the third phase of the analysis we also took the variable of competition into consideration. As argued earlier, the intensity of competition in the Swedish school system varies in different parts of the country. In the three metropolitan areas (Stockholm, Gothenburg, and Malmö, including their suburbs) there is a fully functional school market with a wide variety of schools with different profiles. In other parts of Sweden, especially in the smaller cities and in the countryside, there is not such a wide variety. Given the possibility that the level of competition might have an impact on the local organization of the schools, we divided the group of 364 schools in two strata. One stratum includes the schools in the metropolitan areas, and the other includes schools in non-metropolitan areas (schools located in smaller cities and rural areas). The two strata included 133 and 231 schools respectively.

Selecting and validating cases

Next we will present the result of the analysis of the longitudinal GOLD data, discussing the difference between successful and failing schools. Second, we describe the final stage of the selection process, downscaling the group of schools that are among the most successful and the most failing into eight candidates qualifying for the case studies.

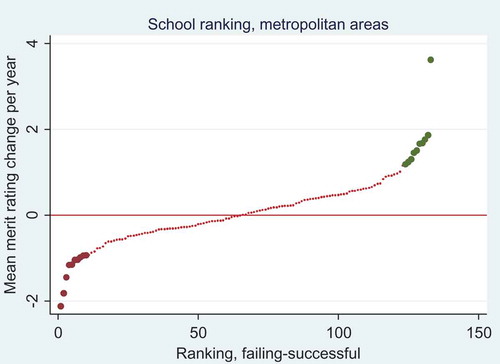

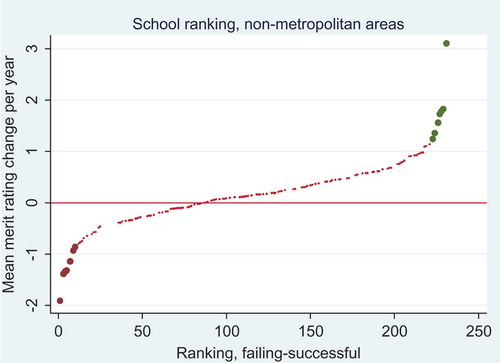

The results from the 364 regression analyses are presented in two scatterplots: includes the 133 schools in the metropolitan areas, and includes the 231 schools in non-metropolitan areas. The two scatterplots reveal similar information. Each point identifies a school. The position of the school on the scatterplot illustrates the result from the OLS regressions comprised of controls for the education level of students’ parents and the students’ immigration backgrounds. In the scatterplots the schools are ranked based on their mean merit rating increase, or decrease, during the 14-year period from 1998 to 2011.

Figure 1. School ranking. Mean merit rating change, Schools in metropolitan areas.

Note: In the figure, the schools in the metropolitan areas are ranked based on their mean merit rating increase, or decrease, during the period 1998-2011.

Source: The GOLD database, Department of Education and Special Education, University of Gothenburg.

Figure 2. School ranking. Mean merit rating change, Schools in non-metropolitan areas.

Note: In the figure, the schools in the non-metropolitan areas are ranked based on their mean merit rating increase, or decrease, during the period 1998-2011.

Source: The GOLD database, Department of Education and Special Education, University of Gothenburg.

As indicated by and , most schools have a mean merit rating change between +1 and -1 merit point per year. There is, however, a quite considerable difference between the most successful and most failing schools in both non-metropolitan and metropolitan areas of Sweden. Schools that have decreased their mean merit rating are located in the lower left in the figures (the ten most extreme are highlighted). Schools that have increased their mean merit rating are at the upper right. The most successful schools have a mean merit rating increase of approximately one to two merit points per year during the 14-year period. Failing schools have a mean merit rating decrease of approximately one to two merit points per year during the same period. In these schools there appears to be a fairly large difference in the schools’ outcomes because of something that has to do with the organization of the individual school. Successful schools have, over a 14-year period, increased their mean merit rating approximately 30 points, while failing schools have decreased their rating 30 points. Taking into consideration that the mean merit rating for all schools in Sweden in 2012 was 211.4, these numbers are quite conspicuous. In theoretical terms the mean merit rating change over the 14-year period might render a mean merit difference from approximately 181 in failing schools to 241 in successful schools.

In sum, the use of longitudinal data has provided us with a solid base for selecting successful and failing schools for systematic comparisons. Next we describe the validation processes for the final selection of eight schools.

The process of validation

The validation process aiming at selecting schools includes deciding the number of schools to select. We aimed at selecting four schools from each stratum, two failing and two successful schools in metropolitan areas and two failing and two successful schools in non-metropolitan areas, as a common recommendation in case study literature is to think in terms of replication. According to Yin (Citation2009:58), one case study should be followed by a replicating study of a case with similar conditions and the same outcome. Thereby, the researcher can compare and analyze whether there is a similar phenomenon causing the outcome.

To make the selection we needed additional information on the schools in order to ensure, as far as possible, that there were no exceptional circumstances which could jeopardize the reliability of our selection. We started by looking deeper into the five most successful and the five most failing schools in each stratum, that is, schools in metropolitan areas and schools in non-metropolitan areas. In total, 20 schools were examined more closely.

We gathered relevant information of each of the 20 schools, including locations and surroundings. Most importantly we turned to reports from the Swedish Schools Inspectorate. The Swedish School Inspectorate conducts regular inspections of all municipal and independent schools and of the municipality or the owner of the independent school. The focus of the inspections is the extent to which the school meets the national requirements: goal achievement and the school climate, including the school’s work on democracy and values. The reports provided us with an overarching picture of the workings of the schools at the time of the inspections. It is important to note, however, that the reports do not cover the entire period we are studying. Nevertheless, we concluded that results from the inspections could function as an indicator of the sustainability of our school rankings.

In a majority of the inspection reports of the schools we examined more closely, there was an overall match with our information on the categorization of the schools being successful or failing. For successful schools in general there were fewer deficiencies documented in the reports than for failing schools. However, there were exceptions. For some successful schools the inspection reports told the story of shortcomings at the time of the inspections, which made these schools less likely to be selected in the second step of the validation process.

Complementary to the reports, we made an overall assessment of how the schools were pictured in the news media as well as of how the schools pictured themselves on their webpages. Roughly, we were interested in whether the schools were described, and described themselves, as well functioning or problematic or dysfunctional.

We found that news media mainly covered the Swedish Schools Inspectorates’ inspections of the schools or principals or parents commenting on the inspection reports. In some cases, however, we found descriptions of the schools’ neighborhoods and of rapid and major changes regarding, for instance, population composition or the closure of large companies— descriptions which we feared could jeopardize comparability between schools. Furthermore, we found that some failing schools were rewarded by the municipality for their successful work on quality assurance, a fact which we believed to be problematic to our purposes. Also, most of the successful schools described themselves in positive and future-oriented terms on their webpages. We did not, however, find similar visions on the webpages of the failing schools. In sum, the complementary analysis made some schools less likely to be selected in the second step even though the general conclusion of the complementary analysis did confirm the results of our ranking of schools.

The second and last step of the validation process included making the final school selection. To maximize the possibilities of inference, we made within-stratum comparisons. In each stratum the top and bottom candidate schools were matched with each other. In particular, characteristics such as a similar number of students in the school and similar geographic locations of the schools were taken into consideration. Especially the geographical location became decisive. We examined the areas and the municipalities in which the schools were situated by using statistical data on the number of inhabitants in the municipalities and their geographic location (proximity to a metropolitan area or smaller city).

illustrates the final eight schools selected for the qualitative study. In the metropolitan stratum, the failing schools are represented by school A (ranked second from the bottom) and school B (ranked fourth from the bottom). One is located in a suburb of one of the three largest cities in Sweden; the other is an inner-city school. The two schools were matched with the two successful schools, C and DFootnote1, in the metropolitan stratum, which are ranked third most and seventh most successful. School C is located in a neighboring suburb of school A and school D in the same city as B.

Figure 3. Selected schools in the two strata and their mean merit rating increase or decrease during 1998-2011.

Note: The Figure shows the selected schools in the two strata, and their mean merit rating increase, or decrease, during the period 1998-2011.

Source: The GOLD database, Department of Education and Special Education, University of Gothenburg.

In the non-metropolitan stratum, the failing school, E, ranked second from the bottom. The school is located in the countryside of northern Sweden. School F ranked fifth from the bottom and is located in a smaller city in the southern part of Sweden. The two schools were matched with two successful schools. School G, ranked second most successful and located in a similar countryside province in northern Sweden as school E and school H, ranked third most successful, located in a small city similar to the city where school F is located.

In sum, seven schools were selected from the groups of the five most successful and the five most failing schools in each stratum while one school, ranked seventh most successful in metropolitan areas, was not.

Conclusion

The article has presented a case selection strategy for comparative case studies of school improvement. In essence, the strategy consists of two basic components: i) selecting cases based on variation of the dependent variable—student outcomes and ii) using longitudinal data to identify cases. By the use of quantitative longitudinal data to identify consistently succeeding and consistently failing schools, the case selection strategy allows a strategic selection of cases, paving the way for systematic comparisons of successful and failing schools. Ultimately, the strategy addresses the demand for a deeper theoretical understanding of how to explain differences in student outcomes between schools. It provides a stable ground to further deepen the understanding of the mechanisms that mediate the effect of schools’ internal organization on student outcomes as observed in school improvement and school effectiveness research. Thus, the article makes an important contribution to the ongoing debate concerning the methodological challenges facing research of school improvement and effectiveness.

We advise future studies in the field of school effectiveness and school improvement to use a systematic approach when selecting cases. A strategic selection of cases opens up for comparisons of the inner lives of successful and failing schools. To be more specific, it allows comparisons of school level factors and processes such as schools’ organizational characteristics. However, deciding what kind of factors, processes and mechanisms to focus on in the case studies should be theoretically guided and the choice of each individual study. In that sense, our recommendation is generic focusing on the intrinsic value of comparisons between schools.

We have not only proposed a case selection strategy for comparative case studies of school improvement, but also demonstrated the strategy’s usefulness. By using a unique data set containing information on family background and student achievement of all individuals born in Sweden between 1972 and 1995, we were able to select four of the most successful and four of the most failing schools in Sweden. The selected successful schools have a mean merit rating increase of approximately 1.4 – 2.1 merit points per year during the fourteen-year period, while the selected failing schools face an equivalent decrease in the mean merit rating during the same time frame.

It should also be noted that the selection was made with controls for the educational level of students’ parents and students’ immigration background. Furthermore, the selection required a validation process in with we gathered additional information of the schools in the sample. We needed to ensure, as far as possible, that there were no other circumstances that would jeopardize the reliability of our selection. Inspection reports from the Swedish Schools Inspectorates’ regular inspections of schools and of the school owner (i.e. municipal or owner of independent schools) provides us with valuable information on the workings of the schools and of the schools’ surroundings. The inspection reports, and some complementary information, made it possible to draw an overall picture of how reliable our categorization of schools as successful or failing was. Even though the validation process showed an overall match with our categorization, it made us aware of the potential shortcomings of relying solely on quantitative data.

To conclude, we believe that the case selection strategy proposed in the article could serve as the basis of empirical studies of school improvement in educational systems other than Sweden’s, with a few adjustments and adaptations. However, the availability of longitudinal data that allows a strategic selection of schools based on students’ results over an extended period of time is a necessary precondition. The abundance of data in Sweden provides unique opportunities to identify schools based on their performance over an extended period of time. Shorter time frames could be used without compromising the strengths of the design. Should there be a lack of longitudinal data at the national level, regionally or locally based data could serve as a valid substitut. However, we advise that further research utilize the strategic case selection process. Selection of schools based on differences in student outcomes under control for relevant aspects of students’ individual background is essential to make inferences on factors and processes influencing schools’ success. We advise that research community and policy makers take initiatives to enable the construction and maintenance of longitudinal datasets regarding student performances.

Systematic comparisons between successful and non-successful schools are essential to elaborate our insights of the mechanisms behind school success. Only by providing causal inference can school improvement and school effectiveness research generate policy recommendations that could make an actual difference for schools aiming at improving student achievement and thus create a better future for their students.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Maria Jarl

Ph.D. Maria Jarl, assistant professor at the Department of Education and Special Education, University of Gothenburg. Her research interests include educational politics and policy, new public management reforms and its impact on the educational system, especially on the professionalization of school principals. She has consulted on educational policy for the Swedish government.

Klas Andersson

Ph.D. Klas Andersson, assistant professor at the Department of Education and Special Education, University of Gothenburg, does research on school improvement and on different aspects of effects of education including political behavior and attitudes towards sustainable development among students.

Ulf Blossing

Ph.D. Ulf Blossing, associate professor in education, Department of Education and Special Education, University of Gothenburg. His research interest is school improvement, organizational development and school leadership on which he has published numerous books and articles. He is involved in principal master programs, action research with municipalities and gives lectures in schools and for the Swedish National Agency for Education.

Notes

1. As one of the matching schools could not be found among the five most successful schools in the metropolitan stratum, we repeated step 1 of the validation process among the 6th to 10th most successful schools in the metropolitan stratum which resulted in the selection of School D.

References

- Ainscow, Mel, and Chapman, Chris. 2005. The challenge of sustainable school improvement. Paper presented at the International Congress of School Effectiveness and Improvement, Barcelona, January 2–5.

- Ainscow, Mel, and Howes, Andy. 2007. Working together to improve urban secondary schools: a study of practice in one city. School Leadership & Management 27(3): 285–300.

- Barth, Roland, S. 1986. On sheep and goats and school reform. Phi Delta Kappan, 68(4): 293–296.

- Blossing, Ulf, Imsen, Gunn, and Lejf Moos (eds.). 2014. The Nordic Educational Model: ‘A School for All’ Encounters Neo-Liberal Policy. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Bogotch, Ira, Mirón, Luis and Biesta, Gert. 2007. “Effective for what; effective for whom?” Two questions SESI should not ignore. In Townsend, Tony (ed.). International Handbook of School Effectiveness and Improvement, 93–109. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Böhlmark, Anders, and Holmlund, Helena. 2011. 20 år med förändringar i skolan. Vad har hänt med likvärdigheten? Stockholm: SNS förlag.

- Cohen, Louis, Manion, Lawrence, and Morrison, Keith. 2006. Research Methods in Education 5th Edition. New York: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Creemers, Bert P. M., Leonidas Kyriakides, and Sammons, Pam. 2010. Theory and research. The problem of causality. In Creemers, Bert, P.M., Kyriakides, Leonidas and Sammons, Pam (eds.). Methodological Advances in Educational Effectiveness Research, 37–58. London: Routledge.

- Creemers, Bert P. M., and Kyriakides, Leonidas. 2010. Explaining stability and change in school effectiveness by looking at changes in the functioning of school factors. School Effectiveness and School Improvement: An International Journal of Research, Policy and Practice 21 (4): 409–427.

- Creemers, Bert, P. M., Scheerens, Japp, and Reynolds, David. 2000. Theory Development in School Effectiveness Research. In Teddlie, Charles and Reynolds, David (eds.). The International Handbook of School Effectiveness Research, 283–298. London: Falmer Press.

- George, Alexander L., and Bennet, Andrew. 2004. Case studies and theory development in the social sciences. Cambridge: Massachusetts.

- Gray, John. 2004. School effectiveness and the “other outcomes” of secondary schooling: A reassessment of three decades of British research. Improving Schools 7(2): 185–198.

- Gustafsson, Jan-Eric. 2013. Causal inference in educational effectiveness research: a comparison of three methods to investigate effects of homework on student achievement. School Effectiveness and School Improvement: An International Journal of Research, Policy and Practice 24 (3): 275–295.

- Gustafsson, Jan-Eric and Yang Hansen, Kajsa. 2011. Förändringar i kommunskillnader i grundskoleresultat mellan 1998 och 2008. Pedagogisk forskning i Sverige 16 (3): 161–178.

- Gustafsson, Jan-Eric and Myrberg, Eva. 2002. Ekonomiska resursers betydelse för pedagogiska resultat – en kunskapsöversikt. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Gustafsson, Jan-Eric, Cliffordsson, Christina & Ericksson, Gudrun. 2014. Likvärdig kunskapsbedömning i och av den svenska skolan – problem och möjligheter. Stockholm: SNS utbildningskommission.

- Hallinger, Philip and Heck, Ronald H. 2011. Exploring the journey of school improvement: classifying and analyzing patterns of change in school improvement processes and learning outcomes. School Effectiveness and School Improvement: An International Journal of Research, Policy and Practice 22 (1): 1–27.

- Harris, Alma. 2006. Leading change in schools in difficulty. Journal of Educational Change 7: 9–18.

- Hitchcock, Graham, and Huges, David. 1995. Research and the Teacher. A Qualitative Introduction to School-Based Research. London: Routledge.

- Hopkins, David. 2001. School improvement for real. London: Routledge.

- Hopkins, David, Harris, Alma, Stoll, Louise and Mackay, Tony. 2011. School and System Improvement: State of the Art Review. Keynote presentation at the 24th International Congress of School Effectiveness and School Improvement, Cyprus, January 4–7.

- Hopkins, David, and Reynolds, David. 2001. The past, present and future of school improvement: Towards a third age. British Educational Research Journal 27 (4): 460–475.

- Höög, Jonas. 2010. Vad är en framgångsrik skola? In Höög, Jonas, and Johansson, Olof (eds.). Struktur, kultur, ledarskap – förutsättningar för framgångsrika skolor. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Höög, Jonas, Johansson, Olof, and Olofsson, Anders 2005. Successful principalship: the Swedish case. Journal of Educational Administration 43 (6): 595–606.

- Höög, Jonas, Johansson, Olof, and Olofsson, Anders. 2009. Swedish successful schools revisited. Journal of Educational Administration 47 (6): 742–752.

- Jackson, David, S. 2000. The school improvement journey: Perspectives on leadership. School Leadership & Management 20 (1): 61–78.

- Jarl, Maria, Fredriksson, Anders and Persson, Sofia. 2012. New public management in public education. A catalyst for the professionalization of Swedish school principals. Public Administration 90 (2): 429–444.

- Johansson, Olof and Höög, Jonas. (eds.) 2010. Struktur, kultur, ledarskap – förutsättningar för framgångsrika skolor. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Kyriakides, Leonidas. 2007. Generic and differentiated models of educational effectiveness: implications for the improvement of educational practice. In Townsend, Tony (ed.). International Handbook of School Effectiveness and Improvement, 41–56. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Konsulterna som styr skolpolitiken. 2015. Sveriges Radio, Vetandets värld. 2 april. http://sverigesradio.se/sida/avsnitt/583043?programid=412

- Kyriakides, Leonidas, Creemers, Bert P. M., Antoniou, Panayiotis and Demetris, Demetriou. 2010. A synthesis of studies searching for school factors: implications for theory and research. British Educational Research Journal 36 (5): 807–830.

- Lincoln, Yvonna. S., and Guba, Egon G. 2000. Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences. In Denzin, Norman K., and Lincoln, Yvonna, S (eds.). Handbook of qualitative research 2nd edition, 163–188. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Lundahl, Lisbeth. 2002. Sweden: Decentralization, Deregulation, Quasi-markets – and then what? Journal of Education Policy 17 (6): 687–697.

- Mill, John Stuart. 1967. A system of logic. Ratiocinative and Inductive. Toronto: University of Toronto Press (the original published in 1843).

- Nicolaidou, Maria, and Ainscow, Mel. 2005. Understanding Failing Schools: Perspectives from the inside. School Effectiveness and School Improvement: An International Journal of Research, Policy and Practice 16 (3): 229–248.

- Nisbet, John D. and Watt, Joyce, S. 1984 Case Study. In Bell, Judith, Buch, Tony, Fox, Alan, Goodey, Jane and Goulding, Sandy (eds.). Conducting Small-scale Investigations in Educational Managment, 79–92. London: Harper & Row.

- Nordenbo, Sven-Erik, Holm, Anders, Elstad, Eyvind, Scheerens, Jaap, Søgaard Larsen, Michael, Uljens, Michael, Laursen, Per Fibaek, Hauge, Trond Eiliv. 2010. Input, process, and learning in primary and lower secondary schools. A systematic review carried out for The Nordic Indicator Workgroup (DNI) (Technical Report Clearinghouse – Research Series 2010 Number 06). Copenhagen: Danish Clearinghouse for Educational Research, DPU; and Aarhus University.

- Pring, Richard. 2000. Philosophy of Educational Research. London: Continuum.

- Reynolds, David, Sammons, Pam, De Fraine, Bieke, Townsend, Tony and Van Damme, Jan. 2011. Educational Effectiveness Research (EER): A State of the Art Review. Paper presented at the 24th International congress of School Effectiveness and School Improvement, Cyprus, January 4–7.

- Rothstein, Bo. 2012. Varför är vissa skolor mer framgångsrika än andra? In Jarl, Maria and Pierre, Jon (eds.). Skolan som politisk organisation, 67–89. Malmö: Gleerups.

- Skolverket. 2012a. Beskrivande data om förskola, skola och vuxenutbildning 2012. Rapport 383. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Skolverket. 2012b. Likvärdig utbildning i svensk grundskola? En kvantitativ analys av likvärdighet över tid. Rapport 374. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Teddlie, Charles, and Reynolds, David (eds.). 2000. International handbook of school effectiveness research. London: Falmer Press.

- Teddlie, Charles, and Sammons, Pam 2010. Applications of mixed methods to the field of educational effectiveness research. In Creemers, Bert P. M., Kyriakides, Leonidas and Sammons, Pam (eds.). Methodological Advances in Educational Effectiveness Research, 115–152. London: Routledge.

- Teorell, Jan, and Svensson, Torsten. 2010. Att fråga och att svara. Malmö: Liber.

- The GOLD database, Department of Education and Special Education, University of Gothenburg, http://ips.gu.se/english/Research/research_databases/gold ( Accessed 2015-06-29).

- The SIRIS database, Swedish National Agency for Education, http://siris.skolverket.se/siris/f?p=Siris:1:0 ( Accessed 2015-06-29).

- Townsend, Tony (ed.) 2007. International Handbook of school effectiveness and school improvement: Review, reflection, and reframing. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Townsend, Tony and MacBeath, John (eds). 2011. International Handbook of Leadership for Learning. Springer International Handbooks of Education. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Thrupp, Martin. 2002. Why “meddling” is necessary: A response to Teddlie, Reynolds, Townsend, Scheerens, Bosker and Creemers. School Effectiveness and School Improvement 13 (1): 1–14.

- Van de Werfhorst, Herman G., and Mijs. Jonathan, J.B. 2010. Achievement Inequality and the Institutional Structure of Educational Systems: A Comparative Perspective. Annual Review of Sociology 36: 407–28.

- Walford, Geoffrey. 2002. Redefining school effectiveness. Westminster Studies in Education 25 (1): 47–58.

- Yin, Robert K. 2009. Case Study Research Design and Methods. London: SAGE.