ABSTRACT

The question of how students’ sense of membership and connectedness to their school can be supported through school practices concerns educational contexts internationally. According to the Programme of International Student Achievement test, students’ experiences of school belonging have decreased and polarized in many of the participating countries since the 2003 test. This study provides new knowledge about the topic by investigating students’ experiences of schoolwide activities from the perspective of social integration. The study approaches social integration from the conceptual pre-understanding presented in Jürgen Habermas’ (1984; 1987) theory of communicative action about the creation of solidarity among groups. The study is based on interview data with Finnish lower secondary students (14–16 years old). The findings show that schoolwide events can be valuable for creating social integration, but the negative aspects of school community may also culminate during these occurrences. This study provides new knowledge about how social integration is constructed in schoolwide events through cultural-level values and commitments, school community-level practices, and personal-level interactions among students. This study has practical importance for developing school practices internationally.

Introduction

The question of how students’ sense of membership and connectedness to their school can be supported through school practices concerns educational contexts internationally. Studies have shown that students’ experiences of belonging to their school community relate to their general wellbeing, as well as to their level of academic performance (e.g., Nichols Citation2008; Roffey Citation2013; Upadyaya and Salmela-Aro Citation2013). However, according to the findings of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD) 2012 Programme of International Student Achievement (PISA) test, students’ experiences of school belonging had decreased in many of the participating countries since the 2003 test (OECD Citation2013). The findings also showed that the students’ experiences of belonging had polarized both within and among schools (OECD Citation2013).

Empirical studies from school contexts around the world have shown that students’ sense of membership within their school community is created both within and outside the formal classroom settings (e.g., Cemalcilar Citation2010; Ma Citation2003; Meeuwisse, Severiens and Born Citation2010; Rowe and Stewart Citation2009; Tinto Citation1997). Studies have also shown that the primary factors for creating a sense of membership and connectedness to the school comprise students’ experiences with their peers and teachers (Goodenow Citation1993; Rowe and Stewart Citation2011). Additionally, the general sense of cohesion within the school has been suggested to be associated with students’ personal-level experiences of belonging (Demanet and Van Houtte Citation2012). However, minimal research has focused on understanding students’ experiences of schoolwide activities and their role in creating cohesion and membership in school (e.g., Allen and Bowles Citation2013; Rowe and Stewart Citation2011; Upadyaya and Salmela-Aro Citation2013).

This study contributes to this knowledge gap by investigating students’ experiences of schoolwide activities from the perspective of social integration. The study approaches social integration from the conceptual pre-understanding presented in Jürgen Habermas’ theory of communicative action (Citation1984; Citation1987). A German philosopher and sociologist, Habermas has become particularly known for his extensive work on critical social theory (see De Angelis Citation2015; Outhwaite Citation1996; Wellmer Citation2014). The theory of communicative action (Citation1987) focuses on the ways that people create meanings through intersubjective communication and control their actions within the social reality. The theory also provides a comprehensive and analytical approach to the concept of social integration that is used in this study to deepen the understanding of students’ experiences about the values and practices related to schoolwide events. Using the philosophical and sociological presuppositions (Habermas Citation1987), this study regards social integration in school as a multidimensional process involving both the individual and the school as a community. Therefore, personal- and group-level processes are considered when examining students’ experiences of schoolwide activities. The following sections present detailed definitions of the social integration concept and the analysis procedure.

This study is based on Finnish lower secondary students’ (14–16 years old) experiences about schoolwide activities. This study aims to reveal how and why schoolwide activities shape social integration in schools. This starting point is linked with Carr and Kemmis’ (Citation1986, 86) statement that the educational sciences aim to gain an “understanding [of] the social processes through which a given educational reality is produced and becomes ‘taken for granted’.” The study is also linked with the objectives of the Finnish National Core Curriculum for Basic Education (Finnish National Board of Education [FNBE] Citation2004; Citation2014), according to which, schoolwide activities are among the ways in which the creation of a sense of community within the school can be supported (FNBE Citation2004; Citation2014). Schoolwide events include celebrations, theme days, and other happenings in which all students are invited to participate. This study is topical from the Finnish and international perspectives because the question of how to increase students’ sense of membership in their school is a significant issue in many countries (OECD Citation2013), as well as why it should be addressed.

Theoretical framework—social integration as a reproductive process of the lifeworld

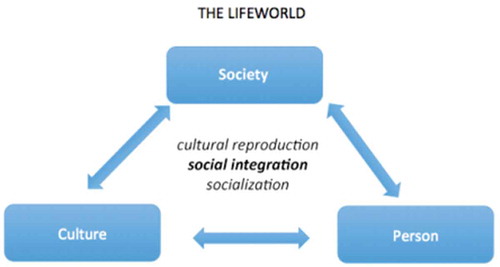

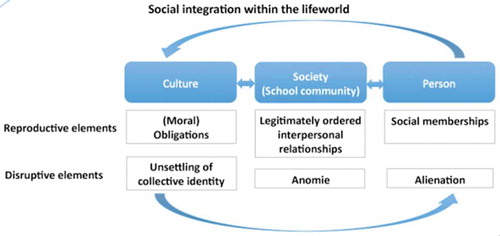

One of the key terms in Habermas’ theory is the “lifeworld,” referring to a socially constructed reality that is constantly negotiated and re-established through communication and subsequent actions (Habermas Citation1984; Citation1987). The lifeworld consists of three structural components, called “culture,” “society,” and “person,” () which are defined as follows:

I use the term culture for the stock of knowledge from which participants in communication supply themselves with interpretations as they come to an understanding about something in the world. I use the term society for the legitimate orders through which participants regulate their memberships in social groups and thereby secure solidarity. By personality I understand the competence that make[s] a subject capable of speaking and acting, that put[s] him in a position to take part in processes of reaching understanding and thereby to assert his own identity (Habermas Citation1987, 138).

Figure 1. Structural components and reproductive processes of the lifeworld, based on Habermas’ theory of communicative action (Citation1987).

It is important to note that the concept of “culture” refers to all kinds of the “stock of knowledge” shared by people (Habermas Citation1987, 138), not to any particular culture or belief system.

According to the theory of communicative action, the lifeworld is negotiated through the processes of “cultural reproduction,” “social integration,” and “socialization” that take place in all of the levels of the lifeworld (Habermas Citation1987). Each of these processes can either contribute to the maintenance of the current status of the lifeworld or disrupt it (Habermas Citation1987). Briefly defined, cultural reproduction refers to the ways in which cultural knowledge is acquired and transmitted within social groups. Socialization involves the ways in which people interpret their personal experiences and life histories in relation to the collective interpretations upheld by their group. However, this study focuses on social integration as it represents the core process through which a group becomes cohesive and establishes membership (Habermas Citation1987, 140–145).

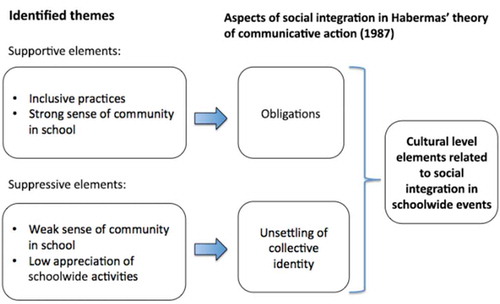

According to the theory of communicative action, the “stabilization of group identities” (Habermas Citation1987, 141), through which a group creates solidarity and its collective identity, is based on the ways in which new situations are connected with the existing conditions, as well as on the ways that actions are carried out within the social space. In this study, organizing and carrying out schoolwide events are viewed as activities that shape the social space and solidarity within schools. The question is how students interpret and share the meanings related to school activities and, based on these, experience a sense of solidarity or a breakdown of group identity. illustrates the ways in which social integration takes form in the different levels of the lifeworld.

Figure 2. Social integration as a reproductive process of the lifeworld, based on Habermas’ theory of communicative action (1987).

At the level of culture, social integration takes the form of “obligations,” referring to certain moral foundations that support the creation of a collective identity among the group members (Habermas Citation1987, 144). These kinds of cultural-level “obligations” comprise commonly accepted values and moral duties that are shared and passed on within the social community. These cultural-level obligations refer to the consensus about the purpose and value of schoolwide events that become visible through the content of these events and through the views attached to the traditions. The countering process of “unsettling of [the] collective identity” pertains to elements that disrupt the moral unity of the group (Habermas Citation1987, 140–145). In relation to schoolwide events these include, for example, the ways of perceiving the events as worthless for the solidarity of the school community or questioning their purpose.

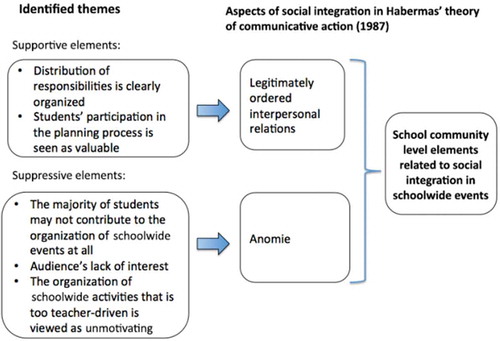

The level of society is used in this study to refer to the school community that includes students and teachers. At this level, social integration takes the form of “legitimately ordered interpersonal relations” that stabilize the group identity (Habermas Citation1987, 140). This means that interpersonal relationships within a group are coordinated up to an extent that allows the group to function in everyday practices (Habermas Citation1987, 140). In relation to schoolwide activities, these primarily include the ways in which the schools share the responsibility of organizing these events and the roles that students play in the process. The countering process of “anomie” refers to a state where intersubjective relationships cannot be coordinated, and the “social solidarity” within a group decreases (Habermas Citation1987, 140–141). In relation to schoolwide events, anomie refers to organizational practices that are being questioned by the students as unjust or meaningless.

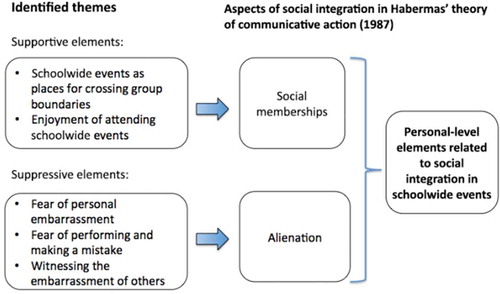

At the level of the person, the cultural-level resources and social patterns of action are linked with the personal experiences and the psychological personality of the individual. Social integration is carried out through the “reproduction of patterns of social memberships” (Habermas Citation1987, 140–144). This refers to the legitimate regulation of memberships and the solidarity among group members. In this study, these include elements within schoolwide events that reinforce students’ sense of community and social membership in their school. The counter-process of “alienation” involves experiences that reduce the sense of cohesion and membership. In relation to schoolwide events, alienation is likely caused by negative and discriminatory experiences.

This study aims to reveal how schoolwide events shape these processes of social integration at the lower secondary level of basic education. It should be noted that the three levels of the lifeworld depict different aspects of the social reality, but they are also all intertwined, and changes in one of them influence the other levels. Likewise, it is noteworthy that schoolwide activities represent just one form of school activities; thus, the experiences related to them do not signify the students’ overall experiences of their school.

Research question

To gain an understanding of the ways in which schoolwide activities may contribute to social integration, the main research question is as follows: How do schoolwide events shape social integration at a) cultural, b) school community, and c) personal levels, according to students’ experiences?

Participants

The data were collected from students at three Finnish lower secondary schools, coded as School 1 (S1), School 2 (S2), and School 3 (S3). All are public schools, mainly attended by students from the surrounding areas, and located in the southern part of Finland. At the time of the study, each school had a population of approximately 300 to 500 students. Official permission to conduct the interviews was obtained from the municipalities and principals, and all the guardians of the eighth and ninth graders were informed about the study. The students participating in the interviews were each required to return a consent form that was signed by a guardian. The semi-structured interviews (approximately 45 minutes each) were carried out during the school day in Finnish and translated later by the researcher. Altogether, the researcher held 14 interviews with 30 students, either in pairs or groups of three. Appendix A presents the list of participants (their names have been changed). Appendix B shows the basic structure of the interviews.

Method and analysis

The analysis had four phases. Table 1 provides an example of the analysis process.

Step 1: The process started with an inductive content analysis of the transcribed data (e.g., Cohen, Manion and Morrison Citation2007; Tuomi and Sarajärvi Citation2012, 117). The individual interviews were viewed holistically through the analysis process so that possible contradictions emerging from the students’ comments were taken into account.

Step 2: A second round of content analysis was carried out to categorize individual experiences under broader thematic concepts (Cohen, Manion and Morrison Citation2007). In the example in Table 1, the quote from Paavo related to the question about the importance of having school events that should be open for all students. Paavo’s authentic remark was formulated into the theme, “It is important to have events that all students can attend” and then summarized under the higher-level category of “inclusive activities.”

Step 3: The inductively formed themes were reflected on in relation to the elements of social integration within the different levels of the lifeworld as depicted in Habermas’ (Citation1987) theory of communicative action. This was done to gain an understanding of the ways in which these elements were related to the cultural-level commitments, the institutional structures of the school, or the personal-level experiences of membership and alienation. In the sample case, Paavo talked about a value that should be present in school events; therefore, the theme represented the moral position that supported the creation of a collective identity within the group. The theme of inclusiveness was therefore situated under “obligations and commitments” that represented a form of internalized moral commitment (step 3 in Table 1).

Step 4: The social integration elements were viewed in relation to the cultural, school-community, and personal levels of the lifeworld (Habermas Citation1987). In the example Paavo addressed the topic from an ethical perspective (saying that it would be wrong to exclude some people from joint activities) and approached inclusive practices as core values concerning all members of the school community. His quote was, therefore, categorized as an example of cultural-level moral obligations (see and step 3 of the analysis procedure). As the levels of the lifeworld are intertwined, inclusion could also be approached from the perspective of school community-level practices and personal-level creation of memberships. However, these aspects were not explicitly discussed in the given example. Therefore, Paavo’s quote represented cultural-level elements of social integration despite having consequences for other levels as well. The Habermasian theoretical concepts were thus used to interpret students’ descriptions in the light of the theoretical frame and to identify various ways in which schoolwide events shaped social integration. In the analysis, the results are presented one level at a time to show in-depth illustrations of how social integration takes form at the different levels.

Findings

Cultural-level perspectives

The values and social practices that guided the ways in which students were treated as a community in schoolwide events were central in many of the interviews. Especially the value of inclusive practices was discussed in the interviews from various perspectives. For example, the students were asked to take a stand on segregating school practices by thinking about an imaginary situation where some students could not attend the joint event (for instance, because of their religious convictions) or by imagining a situation where they themselves could not attend the event for some personal reasons. As shown in the following quotes, the importance of inclusion was justified in many ways. The general value of having schoolwide events was indicated in Niina’s and Emmi’s (S1) explanations that they would feel displeased if they were not allowed to participate in schoolwide activities.

[1] Interviewer: […] So how would you feel if you would not be able to participate in some of the joint activities?

Niina: It would be quite boring in a way […].

Emmi: And perhaps you’d like to anyway see what it’s like in there [in the events].

Niina: Yeah.

In the other parts of their interview, Emmi and Niina described that they usually enjoyed the schoolwide events and regarded some of the activities as highlights of the year. The way they talked about the imaginary situation from an outsider’s perspective (“it would be quite boring” and “perhaps you’d like to”) showed difficulties in placing themselves in circumstances where they would actually be left out; they viewed the right to participate in these activities as self-evident. On the other hand, Paavo, Robert, and Ali (S2) approached the question from a moral point of view and argued that it would be ethically unfair to treat students differently.

[2] Paavo: I think it’s in a way a bit wrong [to leave some people out of these events]. Like so that you leave that part of the group like outside […] the rest of the group.

Interviewer: Okay. What do you think?

Robert: I also think that it’s quite unfair; […] everybody should also take part in all the activities in my opinion.

Ali: I agree. You should have, they [those who cannot participate] should also have a celebration of some sort; it should be organized.

For Paavo, Robert and Ali, the question of inclusion was not restricted to the idea of being in the same physical place but also having equal access to experiences offered by the school. Whereas Ali pointed out that if some students could not attend the main event, the school should organize an alternate program for them, Eero (S2) suggested that a joint activity for all would be better than separate events for different student groups.

[3] Eero: Well, I think one event would be much better so that everybody could be there, like, and at least, I don’t like the Christmas church [visit] very much, and I’ve heard that others have said that they would rather not go there anyway.

Unlike the others, Eero proposed that some of the current practices could be changed to make them more inclusive events.

These reflections illustrated the viewpoints—expressed in many of the interviews—about the importance of holding schoolwide activities that all the students could attend, in one form or another, regardless of their religious convictions or other backgrounds. Inclusion was thus perceived as a core value and a moral obligation that should also be followed in schoolwide activities. As a moral principle, it represented the cultural-level obligations and commitments that supported social integration within the lifeworld (Habermas Citation1987).

Although inclusion was generally discussed as an important principle and a moral guideline, the students had different experiences about the value of schoolwide events in creating a cohesive and inclusive school community. For example, according to Henna and Kaisa (S1), having school events where all the students would get together was not considered a priority. When examined through the interview, it turned out that the reason for this issue was the weak sense of community within the school that was projected onto schoolwide events.

[4] Interviewer: Okay. But do you think that it is important overall that there are like events in the school where everybody gathers together?

Kaisa: Well, I don’t see it as especially important.

Henna: Mm. It’s not like very important in that way.

[…]

[5] Interviewer: So do you think that it matters that there are events at the school that gather everybody together? Or is the sense of community created from some other elements?

Kaisa: It comes from other things.

Henna: Yeah, from something else.

Interviewer: Okay. What kinds of things?

[…]

Henna: Well, that there wouldn’t be any big groups [within the school].

Kaisa: Yeah.

The preceding excerpts showed that the overall sense of community within the school was not regarded as good because (according to Henna and Kaisa) the students were generally divided into small groups, and schoolwide events were perceived as having little significance in changing the situation. Emmi and Niina (from the same school, S1) shared the same experience about the division of students into groups based on grade levels.

[6] Niina: Well, ninth graders and eighth graders have their own [groups] in the lobby area.

Emmi: Yeah or like—like-minded people hang out [with] their own groups, and people who are a bit different hang out [with] their own.

As can be seen from the quote, the students were divided into groups according to their grade levels as well as according to their shared interests. Niina and Emmi also mentioned that they had noticed that some students were not involved with any of the groups but they were unable to identify any common features for these individuals or why they were on their own. Likewise, Henrik and Samuel (S1) reported that the students in S1 were separated according to classes and grades.

[7] Henrik: Well, there are, quite a lot so that each group is [hanging out] in their own groups and—like math graders are in one group and then others are in their own.

Henrik and Samuel also pointed some students’ lack of respect for the school as a community or an institution, with examples of how students stole things from the school’s vitrines or threw nondisposable plates in the cafeteria’s garbage can. When asked if they could think of some ways to improve the sense of school community, they found the question to be difficult. Instead of making suggestions, Henrik and Samuel mentioned that their school had made numerous attempts to promote cohesion through anti-bullying lessons and programs. Samuel also cited schoolwide activities, such as sports days, as among the ways of enhancing the sense of belonging. However, none of these had been considered quite successful; as Henrik admitted, their school was not communal.

[8] Henrik: […] we [students] are pretty separate, and all the places [within the school] get messed up and stuff. There are less of these kinds of things in other schools.

The interviewees’ inability to explain the reasons behind the group-formation processes in their school and their focus on providing examples of processes that had failed to support school unity revealed the students’ difficulty in conceptualizing the issue.

From S2, Linda and Markus were also familiar with the phenomenon of student groups that were not easy for non-members to penetrate. However, this pair of interviewees also acknowledged their own prejudices or even antipathies toward certain student groups.

[9] Linda: Well, it’s … I don’t know—some ninth graders […] are a bit more arrogant and [the] like.

Markus: Personally, I don’t really like the people in the exercise class because […] usually, everybody [gets along] well together [in] the team spirit, but then, like these students in the exercise class, they […] well, they think they are a bit better than others.

Although Markus and Linda talked about arrogant groups, they later clarified that they harbored no negative feelings for the entire class but only for certain individuals with haughty or self-centered behavior.

[10] Linda: [Some people] like take on a role or seek attention a bit too much perhaps.

Markus: Yeah, and that kind of breaks […] the group spirit.

The preceding excerpts showed the intertwined way in which the students were grouped and perceived the members of other groups. In cases where the students were clearly divided according to their classes or grades, the interviewees easily described other students mainly through their group status (e.g., “math graders,” “people in the exercise class,” “ninth graders”). For Markus and Linda, the behavior of individual students was reflected on how the group was perceived as a whole. In relation to the lifeworld, these kinds of processes could be identified as “unsettling of [the] collective identity” (Habermas Citation1987, 140–145) because in these cases, the schools lacked clear collective identities; instead, the students were only attached to their subgroups, if any.

Such divisions among the students disrupted the social integration in the schools and were reflected on the interviewees’ perceived value of schoolwide activities. For example, Henna and Kaisa found that these events had little impact on their school’s community spirit. However, other students regarded schoolwide activities as particularly important elements for enhancing collectivity in the school. In the following excerpts, Kira and Eline (S2) described the overall sense of community or team spirit in their school as very good. When asked about the possible reasons, Kira cited schoolwide activities as one factor.

[11] Kira: I think we have like a really good sense of community.

Eline: Yeah, it’s tight.

Kira: So that like, basically anyone can talk to anyone.

Eline: Yeah.

Kira: And everyone [is] friends [with] everyone, so there aren’t like people who’d just hate someone.

Eline: Yeah.

[12] Interviewer: So in your opinion, what are the reasons behind the fact that you have a good sense of team spirit in your school?

Kira: Well, I guess just like from those Valentine weeks and such […].

As shown from these quotes, the value given by Kira and Eline [quotes 11 and 12] to schoolwide activities was much stronger than in the case of Henna and Kaisa [quotes 4 and 5].

These discussions revealed that the value of schoolwide events was not being evaluated on its own but in relation to the cohesion of the school community and these events’ role in shaping it. As explained in the following sections, the general state of the community spirit was also demonstrated in school-level practices and personal-level experiences of schoolwide activities. In relation to social integration in schoolwide events, the sense of community might thus be reflected on them as a supportive factor of inclusion, or it might be a disruptive element that also reduced the experienced value and purposefulness of schoolwide activities. illustrates the main findings related to social integration at the cultural level. The findings are categorized according to their supportive or suppressive functions in social integration and viewed in relation to the theoretical frame provided by the theory of communicative action (Habermas Citation1987).

School community-level perspectives

The interviewees from all the schools pointed out that the schoolwide events were mainly organized by students of special emphasis classes, such as the drama or music class, or the board members of the student body. The following quotes from Ali (S2) and Matias (S3) exemplified the situation.

[12] Interviewer: So, who are the people organizing these weeks?

Ali: Tutors and the board of the student body.

[13] Interviewer: How was the [organizing] group formed?

Matias: […] From the board of the student body, it was like [asked] who want[ed] to go there and who [would] go, and then it was just decided to take a certain number of people.

This kind of division of responsibility seemed legitimate and taken for granted by these students since they did not mention here or in other parts of their interviews that they wished for other ways to organize these events. However, examining the participation of the students, both in the organizational process and in the actual events, revealed a more complex process.

The different ways of dividing the responsibilities and the active roles of the students are highlighted in the following quotes from Caroline and Kira (S2), as well as from Samuel and Henrik (S1). In both these cases, the interviewees had actively participated in organizing schoolwide events in their respective schools. Caroline and Kira had been involved in tutoring activities; therefore, they had often planned the joint activities in their school. Samuel and Henrik had attended music classes for many years and thus performed in the majority of the school events. The roles of these two pairs of interviewees were therefore similar, but their descriptions remarkably differed in terms of the input of other students in their respective schools. Whereas Caroline and Kira explained that in their school, the other students were generally eager to participate in the final program, for Samuel and Henrik, the situation was the opposite.

[14] Caroline: Every time we have those competitions, the audience is like always really on board so that there are those, if we have like some kind of a competition, who are like ‘I want to compete!’ and sometimes, sometimes, we’ve been like wondering if anyone will come to compete but always, someone has and […]

Kira: Never has it been so that everyone would have been accommodated] in the game, so that there have been really a lot of those who want to be involved.

[15] Samuel: Em … People are not necessarily so eager to get involved in all these things or […].

Henrik: Yeah, it’s like, we are the music class, so [people are like] ‘you’ve chosen it; you deal with it’ [the responsibility].

Samuel and Henrik (S1) explained that their school’s new way of organizing the Christmas celebration by delegating the responsibility to the eighth graders, was an effective approach that made everyone contribute to the process in some way.

[16] Henrik: It’s really good.

Samuel: Mm.

Henrik: That it [the responsibility] doesn’t just rest on the music classes, but everybody does something.

In comparing the viewpoints of Caroline, Kira, and Eline (S2) and Samuel and Henrik (S1) with their previous opinions about the cultural-level value of schoolwide activities [quotes 8,11, and 12], the overall value attached to these events was reflected on the organizational process and vice versa. Caroline, Eline, and Kira regarded schoolwide activities as important for developing the sense of community and described the student body as actively involved in carrying out these events. In contrast, Henrik and Samuel characterized their school community (S1) as strongly divided into subgroups; likewise, the organization of school events had been left to individual students and groups before the new way of sharing responsibility was established.

In relation to the theory of communicative action, the way that responsibility was divided among the different actors represented a form of ordering of interpersonal relationships since the organizational practices determined the way that students were expected to take roles and contribute to schoolwide events. As can be noted from the comments of Caroline [quote 14] and Henrik and Samuel [quote 16], these regulations could support the creation of social integration if the practices were perceived as legitimate by the students. However, this was not always the case. In addition to the lack of active participation in the organizational process, the legitimacy of organizational practices was also questioned. Based on the experiences of Pete and Kasper (S1)—students from the same music class as Samuel and Henrik’s—the students in their school did not pay much attention to the joint events, even when they were going on.

[17] Interviewer: How is your school as an audience?

Kasper: Well …

Pete: Pretty quiet.

Kasper: Yeah. I don’t think people are much interested; mostly, everyone just uses their phone there and … yeah.

Interviewer: So how does that make you feel?

Pete: Well, it doesn’t matter.

Kasper: Yeah, it doesn’t really matter or annoy [me].

The fact that Pete and Kasper were not bothered that their peers focused more on their mobile phones than on the performance showed that they were either not so engaged themselves or did not have much appreciation for the audience’s reactions. Either way, it showed that in these cases, the schoolwide events were not increasing social integration but suppressing it by making both the performers and members of the audience alienated from the joint activities. This lack of engagement by both the performers and the audience represented a state of purposelessness because the students in the audience did not seem to have internalized any kind of role for themselves in these events. In theoretical terms, this behavior signified a state of anomie or confusion (Habermas Citation1987, 140–145), caused by the lack of coordination of intersubjective relations due to the seeming absence of school-level guidelines or any justification for the members of the audience to participate in these events.

Another source of anomie was caused by programs that were only decided by the teachers, as highlighted in the following quotes from Pete and Kasper:

[18] Interviewer: So how do you feel about this kind of organizing where the responsibility is shared by all the classes?

Pete: I think it’s good; there’s nothing wrong with it.

Kasper: It’s alright.

Interviewer: Why is it good?

Kasper: Well, so it won’t go like the teachers say, ‘Let’s take some marine […] theme’ and then sing Under the Sea for three years in a row and make some ‘funny ha ha’ kind of choreography [for] it. So it’s better that you can have some say in it.

In the preceding excerpts, Pete and Kasper explained that the students’ involvement in the organizational practices was important because it increased their personal motivation and engagement in the events. Thus, to feel that their role would be legitimately regulated, students should be involved in the planning process. On the contrary, if the teachers carried out programs that were completely against the students’ interests, it might lead to a state of anomie, where the students would neither understand nor agree with the purposes of the programs, which had not been clearly communicated to them.

The main themes related to the school-level experiences of social integration concerned the students’ role in the organizational process of these events. summarizes the main findings.

Personal-level perspectives

One of the main elements shaping students’ experiences of schoolwide activities was the behavior of their peers in these events, both in positive and negative ways. As shown in the following quotes from Jani (S2), and Ali and Paavo (S2), many of the interviewees viewed schoolwide events as occurrences that brought the students together in a different way than other school activities. In relation to the cultural-level experiences of the school community, in the following comments, the interviewees reflected on the significance of schoolwide activities for crossing group boundaries within the school.

[19] Jani: Well, it’s also important that you do things together so that different classes like get together—you get a sense of community.

[20] Ali: I think that [having events that gather all the students together] influences the sense of community quite a lot, you know—I can’t really explain it.

Paavo: I also think that—now that I think about it—it has an impact. I’m sure that it plays a part [in shaping the community], having everyone gathered together and [having] nice competitions and performances.

These comments emphasized the schoolwide activities’ social and emotional values in shaping students’ experiences of their school as a community. Such communal experiences were also gained by participating in joint traditions. For example, Emmi and Niina (S1) described the Independence Day ball as one of the most important events of the year.

[21] Emmi: Well, [the Independence Day ball] is probably like the highlight of the year, like. Or so. It’s important for the school.

Interviewer: What makes it important? Or more important than other [events]?

Niina: Well, there is like a veteran talking about the war and …

Emmi: And because everyone takes part in it, all the ninth graders.

For Emmi, the special occasion served as a unifying experience because it included the whole school and created a rite of passage for all ninth-grade students by giving them the chance to play the leading role.

Another key factor influencing students’ experiences of these events and of their school was the overall atmosphere within the events themselves. In the following quotes, Erika and Nina (S1) and Pekka (S3) described how they regarded the events as positive and enjoyable to attend. Similar examples could be found in most of the interviews.

[22] Erika: I think a lot of people like going to the celebrations.

Interviewer: To some of the celebrations or all of them?

Nina: Well, all.

Erika: [They go] to all of them.

[23] Pekka: Those kinds of joint events, of course they create a kind of sense of team spirit within the whole school and [are] really nice in other ways as well.

These kinds of positive experiences gained from schoolwide events were supportive for students’ experiences of membership as they increased positive emotional experiences and solidarity within the school community (see Habermas Citation1987, 141). However, in addition to the positive aspects, students’ views of their school community were also deeply affected by negative experiences. The students were particularly sensitive about their peers’ attitudes and especially worried about the idea of being embarrassed in front of their peers. The fear of making mistakes while performing on stage was mentioned in several interviews as a source of concern because other students might start to comment on these, thus humiliating the target of their ridicule.

[24] Markus: Then some, some badass guys or such, they just like shout and try to …

Linda: Yeah.

Markus: Some people’s self-confidence, if they like make some kind of a problem or …

Linda: Mistake …

Markus: Mistake, mistake, blunder, then they like try to, like, demolish the self-confidence [of the performing students].

However, a mistake did not always have to be committed in order for the students to get embarrassed or humiliated as, according to Henna and Kaisa (S1), sometimes there is now external reason but simply the personality of the performer gets targeted.

[25] Henna: Well, if there are like some […] ‘special’ students there, then people from the audience shout all kinds of rude things to the stage.

Kaisa: Yeah.

Henna: So it’s not very nice.

These experiences showed that the students took the embarrassing situations seriously even when they were not the targets. Instead, the fear of embarrassment could also originate purely from observed situations, which were enough to make the students anxious.

Overall, the idea of being a performer at school events entailed a lot of anxiety. For example, this was shown in how Erika and Nina (S1) viewed the mere act of going on stage at schoolwide events as difficult because they were concerned about the gossip afterward. Likewise, Henrik and Samuel (S1), who had both performed at many school events, were aware that many students regarded the act of performing at school events as embarrassing.

[26] Erika: It’s, it’s, because everyone knows everyone—mostly everyone. So that people can say who anyone is, and so it starts from that.

Nina: They [the other students] start to remember it and talk about it.

Erika: Yeah, and to remind [others] about it everywhere.

[27] Samuel: If you do something in a wrong way, then it’s embarrassing and …

Henrik: Well, it’s the other students’ attitude, like ‘I’m not going there because it’s embarrassing.’ I’m not sure […] what’s the problem with it.

In relation to the personal-level experiences about schoolwide activities and the social integration in them, it could be observed that the anxiety related to these events was alienating as it prohibited or hindered the individual students from engaging with their schoolmates and from trusting them.

Discussion and conclusions

This study investigates students’ experiences of schoolwide events from the social integration perspective (Habermas Citation1987). This study uses Habermas’s (Citation1984; 1987) theory about the structural components of the lifeworld for analyzing students’ experiences from the perspectives of culture, school community, and the person.

Regarding the cultural level (Habermas Citation1987), this study’s findings indicate that social integration can be supported by highlighting inclusion as a moral obligation that should penetrate all school activities. The findings of this study highlight the importance of having practices that include all students and thus confirms previous studies’ reports about the importance of inclusion for students’ wellbeing (Nichols Citation2008; Roffey Citation2013). However, the findings also demonstrate that the perceived value of schoolwide events is linked with the personal- and group-level social cohesion that students experience in their school. When the communal feeling is weak, the possibilities for schoolwide events to strengthen it are regarded as miniscule. When the sense of community is generally strong, the value of schoolwide events is also considered high.

Concerning the school-community level of the lifeworld (Habermas Citation1987), the findings show that social integration is supported by organizational practices that foster student participation. This is achieved mainly by delegating responsibilities in a clear and legitimate manner that allows the students’ active involvement in the planning process instead of the teachers being the sole decision makers. On the contrary, social integration is disrupted by practices that are perceived as assigning much responsibility to some student groups, while leaving others without any task. Such practices, along with the lack of audience interest and the disrespectful attitude toward school performances, suppress social integration by reducing students’ motivation and understanding about the purpose of these events. These findings support previous studies’ arguments for the positive value of school activities outside classrooms (e.g., Ma Citation2003; Rowe and Stewart Citation2009; Tinto Citation1997), especially the events’ worth in creating a sense of membership in school (Rowe and Stewart Citation2009; 2011). However, this study’s results also show that poor planning may lead to a state of anomie, where some students fail to internalize any kind of role or code of conduct for themselves in these events. This situation is particularly troublesome in schoolwide events, given their primary aim to gather all students and support their active participation in the school community (FNBE Citation2004; Citation2014). These viewpoints are important to consider when developing school practices from the social integration perspective.

The findings also indicate schoolwide events as social occurrences shaping students’ experiences of themselves as members of the school community. Regarding the personal level of the lifeworld (Habermas Citation1987), social integration is created by a sense of membership based on positive experiences of crossing group boundaries and peer encounters in schoolwide events. However, the experiences of membership are disrupted by the fear of embarrassment in front of peers and by some students’ rude attitudes toward performers on stage. Such negative encounters hinder social integration in the school community by causing students’ reluctance to participate and their dread of being bullied by peers, thus leading to alienation. These outcomes extend previous findings that peers are crucial in creating a sense of belonging (e.g., Cemalcilar Citation2010; Ma Citation2003; Meeuwisse, Severiens and Born Citation2010; Rowe and Stewart Citation2009; Tinto Citation1997), and peer relations are central in influencing students’ experiences of schoolwide activities. Thus, this study highlights the significance of students’ mutual interest and respect at the schoolwide level, beyond friendships or classroom-level relationships.

Habermas’s (Citation1984; Citation1987) theory is found beneficial for identifying the different ways in which schoolwide events shape social integration within schools because it provides a conceptual framework for analyzing social reality while recognizing the intertwined nature of social processes. This study’s main limitation is its exclusion of the other processes of cultural reproduction and socialization (Habermas Citation1987); therefore, future research is required to address their roles. Another drawback is this study’s sole focus on social integration in schoolwide events. Further studies should thus examine the function of social integration in other aspects of school life, such as classroom activities and the roles of parents and the administration. In addition to the Habermasian framework, applying network analysis could be beneficial in this regard.

The fact that the students in this study manifested difficulty in verbalizing questions of social integration makes it imperative to probe deeper into how social reality is constructed in schools (e.g., Carr and Kemmis Citation1986). Despite its shortcomings, this study provides new knowledge about how social integration is constructed in schoolwide events through cultural-level values and commitments, school community-level practices, and personal-level interactions among students. This research emphasizes the need to learn more about students’ experiences concerning the values and practices involved in schoolwide events to make these motivating and meaningful celebrations that support cohesion and membership in schools.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Professor Fred Dervin, PhD, for his valuable comments on this paper. She also expresses her gratitude to the Finnish Cultural Foundation for the research grant that supported this study.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pia-Maria Niemi

Pia-Maria Niemi, MTh, is pursuing her doctorate in education at the Department of Teacher Education at the University of Helsinki, Finland, where she has also worked as a university teacher. Her research interests include the school as a social context, intercultural education and pedagogical choices. Niemi is a qualified subject teacher and holds a master’s degree in theology with a major in comparative study of religions and minors in education and psychology.

References

- Allen, Kelly and Bowles, Terence. 2013. Belonging as a guiding principle in the education of adolescents. Australian Journal of Educational and Developmental Psychology 12: 108−87.

- Carr, Wilfred and Kemmis, Stephen. 1986. Becoming critical: education, knowledge and action research. London: Routledge Falmer.

- Cemalcilar, Zeynep. 2010. Schools as socialisation contexts. Understanding the impact of school climate factors on students’ sense of school belonging. Applied Psychology: An International Review 59 (2): 243–272. DOI: 10.1111/j.1464-0597.2009.00389.x

- Cohen, Louis, Manion, Lawrence and Morrison, Keith. 2007. Research methods in education. 6th ed. London: Routledge.

- De Angelis, Gabriele. 2015. The foundations of a critical social theory: lessons from the Positivismusstreit. Journal of Classical Sociology 15 (2): 170–184. doi: 10.1177/1468795X14567286.

- Demanet, Jannick and Van Houtte, Mieke. 2012. School belonging and school misconduct: the differing role of teacher and peer attachment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 41 (4): 499−514.

- Finnish National Board of Education. 2004. National core curriculum for basic education 2004[Perusopetuksen opetussuunnitelman perusteet 2004].http://www.oph.fi/english/curricula_and_qualifications/basic_education ( Accessed 2016-01-03]

- Finnish National Board of Education. 2014. National core curriculum for basic education 2014 [Perusopetuksen opetussuunnitelman perusteet 2014].http://www.oph.fi/ops2016/perusteet. ( Accessed 2016-01-03]

- Goodenow, Carol. 1993. The psychological sense of school membership among adolescents. Scale development and educational correlates. Psychology in the Schools 30: 79−90.

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1984. The theory of communicative action: reason and the rationalization of society. Vol. 1.(M. McCarthy,trans.).Cambridge: Polity Press. (Original work published in 1981).

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1987. The theory of communicative action: lifeworld and systems: the critique of functionalist reason. Vol. 2.(M. McCarthy,trans.).Cambridge: Polity Press. (Original work published in 1981).

- Ma, Xin. 2003. Sense of belonging to school: can schools make a difference? The Journal of Educational Research 96 (6): 340−349. doi: 10.1080/00220670309596617.

- Meeuwisse, Marieke, Severiens, Sabine and Born, Marise. 2010. Learning environment, interaction, sense of belonging and study success in ethnically diverse student groups. Research in Higher Education 51: 528–545. doi: 10.1007/s11162-010-9168-1.

- Nichols, Sharon. 2008. An exploration of students’ belongingness beliefs in one middle school. The Journal of Experimental Education 76 (2): 145−169. doi: 10.3200/JEXE.76.2.145-169.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2013). Engagement with and at school. In PISA 2012 Results: Ready to learn: Students’ engagement, drive and self-beliefs ( Volume III). PISA: OECD Publishing: 39–62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264201170-en ( Accessed 2016-17-03).

- Outhwaite, William. 1996. General introduction. In W. Outhwaite (ed.). The Habermas reader. Cambridge: Polity Press, 3–22.

- Roffey, Sue. 2013. Inclusive and exclusive belonging – the impact on individual and community well-being. Educational and Child Psychology 30 (1): 38−49.

- Rowe, Fiona and Stewart, Donald. 2009. Promoting connectedness through whole-school approaches: a qualitative study. Health Education 109 (5): 396−413.http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09654280910984816 ( Accessed 2016-17-03)

- Rowe, Fiona and Stewart, Donald. 2011. Promoting connectedness through whole-school approaches: key elements and pathways of influence. Health Education 111 (1): 49−65. doi: 10.1108/09654281111094973.

- Tinto, Vincent. 1997. Classrooms as communities. Exploring the educational character of student persistence. Journal of Higher Education 68 (6): 599–623.

- Tuomi, Jouni and Sarajärvi, Anneli. 2012. Laadullinen tutkimus ja sisällönanalyysi [Qualitative research and content analysis]. 9th ed. Helsinki: Tammi.

- Upadyaya, Katja and Salmela-Aro, Katariina. 2013. Development of school engagement in association with academic success and well-being in varying social contexts. A review of empirical research. European Psychologist 18 (2): 136–147. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000143.

- Wellmer, Albrecht. 2014. On critical theory. Social Research: An International Quarterly 81 (3): 705–733. doi: 10.1353/sor.2014.0045.

Appendix A: Student interviews

Appendix B: Basic structure of interview questions

Warm-up question:

What kinds of school days do you enjoy most or look forward to most in the school year?

What is it that you like about these days?

Questions about the types of activities organized:

In addition to regular school days, what kinds of exceptional days do you have in the school?

Do you, for example, have some days with special programs? What events have been most memorable for you?

What kinds of activities do you have during these days?

Does everyone at your school attend these events or are some people left out? (For example, do you have Christmas parties that are not attended by students from different religious backgrounds?)

Could these events be replaced by classroom activities or programs broadcast on school radio? Why/why not?

Questions about students’ experiences of whole-school activities at their school:

How do you feel about the activities organized?

Are these events something you look forward to, or are they mainly an obligatory part of school work?

Do you think it is important to have these kinds of days at school? Why/why not?

Why do you think these kinds of events are organized at school?

Questions about students’ experiences of organizing whole-school activities:

How are the events organized at your school?

Have you taken part in organizing these events? How?

Have you ever performed on stage at school celebrations?

If yes, how did you find that experience?

If no, would you like to perform on stage at school celebrations? Why/why not??

Questions about students’ experiences’ of the sense of groupness at their school:

Do you think it important to have events at school that gather everyone in the school together? Why/why not?

How would you describe your school as a community? What kind of school spirit do you have here?

What do you think are the main aspects that create the kind of ‘school spirit’ you have at your school?

Questions about the ways students see the role of whole-school activities in shaping the sense of community at school:

What do you think in general are the key elements shaping the creation of team spirit in school?

In your opinion, do you think that having these kinds of whole-school activities influences the team spirit at your school in some way or not?

If yes, in what way?

If not, why?