ABSTRACT

Children in foster care may face difficulties during their school years. When it comes to academic achievement, there is reported low school performance and lower grades. However, school may be strong protective factor in difficulties if supports are individual. School-based interventions represent a possibility for supporting children whose home life may make them vulnerable. This discussion paper presents Finnish initiative, which is based on Skolfam® model used in several Nordic countries.

Introduction

Children in foster care are vulnerable in many ways – not just emotionally, but also when it comes to school achievements. Teachers estimate (Zetlin, Citation2012) that most children in foster care encounter difficulties during their school years more often than other children. However, it is important to note that not all children living apart from their birth parents have difficulties (Bernedo et al., Citation2012, Iversen et al. Citation2010). There are obvious risks of educational under-achievement if a child has spent time in foster care, but it is clear that placement in a stable home may do much to help and support a child. It is estimated (Zima et al., Citation2000) that 69% of children in foster care have behavioural problems and experience delays in academic achievement, or are not successful at school.

When it comes to academic achievement and grades, Berlin, Vinnerljung, and Hjern (Citation2011) reported low school performance and lower grades among children in foster care, and it is of particular concern that grades in so-called academic subjects are poor. This also has been observed in several other surveys (Evans Citation2001, McCrae et al., Citation2010; Rosenfeld & Richman, Citation2003; Iversen et al., Citation2010, Trout et. al. 2007). Vinnerljung and Hjern (Citation2011) found that foster children’s cognitive competence at the age of 18 was lower than that of adopted or other children.

Learning difficulties are common among foster children (Iversen et al., Citation2010), along with problems with reading and math (Trout et al., 2007). Mitic and Rimer (Citation2002) calculated that about 40% of all children in continuing foster care in British Columbia showed weaker reading and writing skills than their peers, and half of them encountered frequent problems with numerical literacy. Zima et al. (Citation2000) said 23% of the children in foster care (n=302) had serious problems with reading and math. However, children in foster care have access to special education (Geenen & Powers, Citation2006; Iversen et al., Citation2010). The results of a large-scale meta-analysis (Scherr, Citation2007) indicated that 27% to 35% of children placed outside of their biological parents’ homes get or need special education.

Research shows that foster care is also linked to poor school adjustment (Fantuzzo, Citation2007), which limits school achievement and increases dropout risks. Kestilä et al. (Citation2012) verified in their study that young foster adults are five times more likely to have only basic education compared with other young adults. It is clear that a poor educational background may cause problems in attaining further education or finding employment.

Evans (Citation2004) said the academic development of students at risk could be improved through their school experience. Font et al. (Citation2013) argue that foster children are more emotionally attached to school than their mistreated peers. Thus, there is evidence that foster children’s attitudes to school are more positive following placement in homes than they were before it (Hedin, 2010; Harker et al., 2003). Although children may have difficulties with learning, school provides routines and predictability, which help them cope. Support from both foster parents and a school is a motivating factor for children as well (Harker, 2003). Johansson and Höjer (Citation2012) noticed that if a person with a care background has a stable educational identity, in addition to cultural and social capital, he or she can benefit from effective protection against low-income and other factors, which, in turn, will help with engagement in studies. Forsman and Vinnerljung (Citation2012) said interventions usually improve foster children’s poor academic achievements. School and education can be powerful protective factors in supporting children in spite of the situation at home.

School-based intervention to support success in school

Skolfam® based intervention SISUKAS in Finland

School-based interventions represent a promising possibility for supporting children whose home life may make them very vulnerable. Swedish Skolfam® programme is an intervention-based effort to support children (Skolprojekt inom familjehemsvårde, 2014). The programme is also put into practice and evaluated also in Norway (Havik Citation2013) and Denmark (Skolen rolle i…, n.d.). The aim of Skolfam® is to support the achievements of school-age children who are in foster care. Skolfam® intervention takes at least two years, and is based on large and multi-faceted psychological and educational assessments, follow-up, and support that cater to the individual needs of each child (Skolfam® 2016). Special-needs education teachers, class teachers, psychologists, and social-service workers organise the assessments/testing. Following the assessments, children’s strengths and weaknesses are analysed by the Skolfam® team so that the best possible intervention can be established. The team consists of parents, pedagogical and psychology staff, staff from social services, and foster care personnel. After the intervention, a new assessment period takes place, and a follow-up is planned (Om Skolfam®, 2014). Poor educational performance by foster children is expected to be improven through systematic work by foster care specialists and schools. The reported positive outcomes in other Nordic countries also have attracted interest in Finland, and the first intervention programme based on the Skolfam® model has been launched (Välivaara, Citation2014). The initial assessments in the Finnish project have been completed (Räty et al., Citation2014), and preliminary findings showed some progress (Oraluoma & Välivaara, Citation2016). Influenced by the Skolfam® model, the Finnish ‘Foster Child at School Intervention’ programme (SISUKAS) aimed to improve school achievement and the well-being of children in foster care. During the project (2012-2016), a two-year intervention period was organised. The child’s social worker, psychologist, and special-education teacher formed a cooperative –project team that tested 20 foster children. In the cooperative, there were 16 schools and six kindergartens with 15 girls and five boys (ages 6-10) included in the project.

The procedure

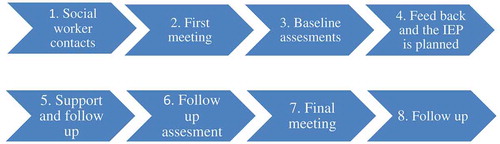

The SISUKAS intervention started when a child’s social worker contacted the child, family, foster family, and school, then organised the first meeting with the foster family and child. Soon afterward, the entire network (SISUKAS project team, parents, child and school professionals) met at the school. The meeting was followed by the first surveys/tests, given by the special-education teacher and psychologist, as well as the social worker. The findings were shared with all intervention parties, who planned the individual support efforts in close cooperation with parents, the child himself/herself, and the school. The progress of each child was followed intensively. The network had two to three meetings monthly. Follow-up was done after the two-year intervention period, and the findings were shared and discussed within the network meeting (Liukkonen, Oraluoma, Saksola & Välivaara Citation2015). shows the whole procedure.

Figure 1. Working procedure in Finnish SISUKAS program (Oraluoma & Välivaara Citation2016, 19, permission from Pesäpuu).

Baseline assessments

The intervention started with the assessment of the children’s baseline situation, and the same tests and assessments were done after two years of intervention. Standardised psychological and pedagogical instruments were used for assessing the child’s potential, strengths, and difficulties. Assessed areas included cognitive skills (WISC-IV), psychological well-being (SDQ, Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire), problem behaviour (CBCL, Child Behaviour Checklist) student-teacher relationship (STRS, Student-Teacher Relationship Scale), reading skills (ALLU), and math skills (MAKEKO). Writing skills and school readiness also were assessed. The ‘Me as a Learner’ questionnaire (Aro et al. Citation2014) assessed students’ thoughts about strengths and difficulties in learning. Classroom observations were made as well (Räty, Välivaara, Mäntymaa, Saksola & Pirttimaa Citation2014).

Intervention

During two years’ time, the children were supported by all available methods at school and home, following an individualised education plan (IEP) based on the test results and observations. The role of the project team was to consult the adults who worked with the child and to monitor progress.

What did this individual plan consist of? In all cases, the selection of objectives was justified on the grounds that the tests involved in the SISUKAS programme also were used in the Skolfam® programme. Nevertheless, all participating children had objectives that were also justified by other observations. ‘The teachers had already noticed that there is need for support’, and ‘The foster parents raised concerns’, told the project team members. In addition, the observations made by project team in the classroom supported the information received from the tests. When these plans and objectives were screened, the most prominent division that emerged was between consolidating students’ performance in school subjects on the one hand, and supporting their psycho-social skills on the other. Not all children had both of these aspects noticed in their individual plans. The ways to reach the objectives varied.

What did schools actually do to support students’ emotional and social well-being and success in academic school subjects? Which methods were employed? According to the cognitive learning theory/activity theory of learning (Engeström Citation1987/2007), teaching methods can be observed by dividing them into external and internal methods. External teaching methods are used to control students’ perceptible behaviour and situation. Internal teaching methods focus on guiding students’ cognitive processing. In the objectives concerning school subjects, external methods were mentioned and written down in the plan, but this does not mean that teachers did not plan how to tutor students on cognitive processes. These methods were fully aligned with the principles, curriculum models, and structures in Finland’s educational system. In Finnish comprehensive schools, when the need arises, the supports include individual special supports/tutoring or small-group remedial special teaching, either on a full-time or part-time basis, provided by a special-needs education teacher. In support of psycho-social well-being, both individual supports and group supports were used. Both external and internal teaching methods were mentioned in individual plans.

Trust was an important aspect when the project team described the methods of support for social well-being. This was important during discussions between students and teachers. Humour was another element that was mentioned as a useful tool in interactions. Individual plans also included activities that were carried out with entire classes. Social-drama exercises, as well as programmes to help children recognise their emotions, were used. While inspecting so-called external methods of supporting psycho-social well-being, implementation most often consisted of personal care by psychiatrists, psychologists, physical therapists, or social workers outside of school hours. In more demanding situations, personal assistance in classrooms was provided. Sometimes, discussions on the use of medications were planned and later held. Special equipment and physical arrangements had to be made in some cases, such as a special chair or an isolated working space to aid in concentration. shows the details of the supports planned in IEPs

Table 1. Supports mentioned in individual education plans (Summarized table from Oraluoma & Välivaara Citation2016, 29-30).

Findings

After two years of intervention, re-testing was done. These test results were compared with pre-intervention for assessing outcomes. Results showed improvement in some of the academic skills at the group level and individual improvement in psychosocial well-being (detailed statistics in Oraluoma & Välivaara Citation2016). The follow-up research (Oraluoma & Välivaara, Citation2016, 50- 53) add up the detailed findings and said most of the children who raised concerns in the beginning reached two or more goals during the intervention. Most often, successes were revealed in the Strengths and Difficulties survey, in math, and in writing skills. Findings connected to the psycho-social well-being on the group level showed that some of the children achieved the goals well by the end of the intervention period. Those with more severe difficulties continue to receive more intensive support at school and outside of their school (Oraluoma & Välivaara Citation2016). On the group level, statistics showed no significant differences before or after testing/assessment. It must be argued that although the statistical value might be weak in this relatively small case study, on the individual level, intensive work was experienced to be successful (see also Durbeej & Hellner Citation2016). This Finnish experience strengthens the earlier findings of Eronen (Citation2013, 49) that the situations and needs of children in foster care are very specific to each child and change over time. Aid is not possible to plan on a general level (Oraluoma & Välivaara Citation2016).

General comparisons between the Swedish Skolfam® and Finnish SISUKAS programmes were possible, although the assessment tools were partly different, and the statistical tests used were not in the same manner. It was found that children developed their learning abilities and academic skills in both programmes. However, in the Finnish research, no changes in general intelligence were found. The findings concerning psychosocial well-being under Skolfam® and SISUKAS found similar positive changes. Also, SISUKAS results showed that parents and teachers’ worries declined. (Oraluoma & Välivaara Citation2016).

Conclusions

In Finnish schools, an IEP is a legally regulated document, and intervention practices for foster children did not differ from general school work. IEPs are written documents produced by a multi-professional team. Thus it is quite easy to fit the earlier described intervention program into the school system. In Finnish schools, the supports are organised by three-tiered systems. Immediate and flexible support for everyone is called general support, the first tier. If general support is not sufficient, a new plan is made, and intensified support, the second tier, is utilised. The third tier is special support, which is the most intensive and ongoing support system. The level of intensity of needed supports varied from child to child (). However, the children in the SISUKAS programme more often received support, compared with other schoolchildren in Finland (Statistics Finland, Citation2015). In the case of three children, the intensity of support changed during the two-year period: Two students moved from the intensified to the special support tier, while one child moved from general to intensified support. The problems among those moving to a more intense tier of support mostly concerned psycho-social well-being (Oraluoma & Välivaara Citation2016).

Table 2. The supports used in the beginning of the intervention for pupils in foster care (Oraluoma & Välivaara Citation2016, 28).

What overall issues are important in planning, goal setting, and choosing individual support methods that are aimed at helping children in foster care achieve success in school? After two years under SISUKAS intervention, a discussion with project team members (special education teacher, psychologist, social worker and project manager) was held. They cited three factors that are integral to success: 1) cooperation, 2) teaching and 3) the child’s growth and development.

Those closest cooperation partners to each case are schoolteachers, the family and, obviously, the child. School and project team members were the active partners to initiate the cooperative efforts. Children were involved in the planning discussions, as well as the assessments. Project team organised the cooperative efforts with different partners, including the foster families, school staff, local social workers, and other significant local actors. Meetings occurred in homes, at school, or at the offices of out-of-school professionals (psychiatrists, social workers, etc.). Face-to-face contacts were preferred, but information was exchanged via other ways as well, always in a manner that was deemed constructive and effective. Huge network meetings were avoided. Cooperation within the class meetings (parental meetings) often was not very strong because of the intimate nature of the issues that needed to be planned and implemented. Project team estimated that good preparation for scheduled meetings and collaborative efforts provided solid ground for collaboration. Cooperation and collaboration were estimated to be some of the most important ways to fulfil the goals of each individual programme. If it failed, the planning may have been successful, but the implementation was estimated to be slow or problematic. There is a clear need for mutual trust and understanding, especially open communication back and forth between programme workers and the foster families. Trust encourages collaboration and vice versa. As Daniels (Citation2006) says, ‘(If) well-being and trust are built in collaborative working cultures, then individuals feel more tolerant of the demands of work and more prepared to engage with problematic areas of work’.

There is no doubt that teaching and teachers’ work are meaningful. They are the main agents for directing schoolwork. It was stressed that successful teaching is possible if objectives are suitable for the student. Differentiation of materials and methods is useful. It is also good when teachers have immediate access to a range of services (special education, assistants, etc.) and are supported by school principals.

In addition, it is obvious that educators should trust in the normal development and growth of the child. Children mature at their own individual pace, and as they grow, they will better understand their situation and set their own goals, when the time is right for them. While growing, children face various changes. Puberty is one period when challenges may emerge not only at home, but also at school. ‘Learning needs time’, as project workers say. However, the ethos of the SISUKAS programme does not encourage waiting and discovering. Waiting does not support the growth of the child most effectively in challenging situations.

It is hoped that the intervention phase for foster children will generate no additional workload for teachers and is easily accepted as part of general school work. This is possible because schools have systems involving IEPs for special situations, and these have proven to be useful in practice. This available planning arrangement was fully in use in the programme, and it can be argued that the Skolfam®-based intervention system as SISUKAS is generic enough that it can be carried out in different school systems. Although schools might lack various professionals (such as school psychologists), and contact with the social-service sector is not yet common in Finnish schools, it has been estimated that the SISUKAS intervention model is suitable in the existing support system of Finnish schools, as well as special-education environments.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Raija Pirttimaa

Raija Pirttimaa PhD is a senior lecture in the University of Jyvaskyla and an adjunct professor of special education in the University of Helsinki.

Christine Välivaara

Christine Välivaara MA (Psych) is a development manager in the Finnish National Child Welfare Association Pesäpuu (registered).

References

- Aro, Tuija; Järviluoma, Elina; Mäntylä Marketta; Mäntynen Hanna; Määttä Sira; and Paananen, Mika. 2014. KUMMI 11. Oppilaan minäkuva ja luottamus omiin kykyihin. Jyväskylä: Niilo Mäki Instituutti.

- Berlin, Marie; Vinnerljung, Bo; and Hjern, Anders. 2011. School performance in primary school and psychosocial problems in young adulthood among care leavers from long time foster care. Children and Youth Services Review 33(12):2489−2497.

- Bernedo, Isabel M.; Salas, Maria D.; García-Martín, Miguel Angel; and Fuentes, Maria J. 2012. Teacher assessment of behaviour problems in foster care children. Children and Youth Services Review 34(4):615−621.

- Daniels, Harry. 2006. Rethinking intervention: changing the cultures of schooling. Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties 11 (2): 105−120.

- Durbeej, Natalie; and Hellner Gumpert, Clara. 2016. Effektutvärdering av arbetsmodellen Skolfam bland familjehemsplacerade barn i Sverige. [Estimation of the effects of Skolfam]. Centrum for psykiatriforskning. Rapport Dnr 2016/01. http://psykiatriforskning.se/siteassets/effektutvardering-av-arbetsmodellen-skolfam-bland-familjehemsplacerade-barn-i-sverige—kopia.pdf (Accessed 2016-12-05).

- Eronen, Tuija. 2013. Viisi vuotta huostaanotosta. Seurantatutkimus huostaanotettujen lasten institutionaalisista poluista. [ Five years after a care order: A follow-up study on the institutional paths of children taken into care]. National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL). Report 4. Helsinki. Tampere: Juvenes.

- Evans, Larry, D. 2001. Interactional models of learning disabilities: Evidence from students entering foster care. Psychology in the Schools 38(7): 381−390.

- Evans, Larry D. 2004. Academic achievement of students in foster care: Impeded or improved? Psychology in Schools 41(7): 527−535.

- Engeström, Yrjö. 1987/2007. Perustietoa opetuksesta. [Basics of teaching]. Opiskelijakirjaston verkkojulkaisu. https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10224/3665 (Accessed 2016-12-05).

- Fantuzzo, John and Perlman, Staci. 2007. The unique impact of out-of-home placement and the mediating effects of child maltreatment and homelessness on early school success. Children and Youth Services Review 29(7): 941−960.

- Font, Sarah and Maguire-Jack, Kathryn. 2013. Academic engagement and performance: Estimating the impact of out-of-home care for maltreated children. Children and Youth Services Review 35, 856−864.

- Forsman, Hilma and Vinnerljung, Bo. 2012. Interventions aiming to improve school achievements of children in out-of-home care: A scoping review. Children and Youth Services Review 34(6): 1084−1091.

- Franzén, Eva; Vinnerljung, Bo; and Hjern, Anders. 2006. Foster children as young adults: Many motherless, fatherless or orphaned: a Swedish national cohort study. Child and Family Social Work 11(3): 254−263.

- Geenen, Sarah and Powers, Laurie E. 2006. Are we ignoring youths with disabilities in foster care? An examination of their school performance. Social Work 51(11): 233−241.

- Harker, Rachel; Dobel-Ober, David; Akhurst, Sofie; Berridge, David; and Sinclair, Ruth. 2004. Who Takes Care of Education 18 months on? A follow-up study of looked-after children’s perceptions of support for educational progress. Child and Family Social Work 9(3): 273−284.

- Havik, Toril. 2013. Å styrke forsterbarns laering- erfaringer fra et utviklings- og forskningsprosjekt. [Strengthening learning experiences of children in foster care: A development and research project]. In Elisabeth Backe-Hansen, Toril Havik, Arne Backer Grønningsaeter (eds.) Foster hjem for barns behov. Rapport fra et fireårig forskningsprogram. Norks institutt for forskning om oppvekst, velferd og aldring. NOVA Raportt 16, 197− 222.

- Hedin, Lena; Höjer, Ingrid; and Brunnberg, Elinor. 2011. Why one goes to school: What school means to young people entering foster care. Child and Family Social Work 16, 43−51.

- Iversen, Anette C.; Hetland, Hilde; Havik, Toril; and Stormark, Kjell M. 2010. Learning difficulties and academic competence among children in contact with the welfare system. Child and Family Social Work 15(3): 307−314.

- Johansson, Helena and Höjer, Ingrid. 2012. Education for disadvantaged groups: Structural and individual challenges. Children and Youth Services Review 34(6): 1135−1142.

- Kestilä, Laura; Paananen, Reija; Väisänen, Antti; Muuri, Anu; Merikukka, Marko; Heino, Tarja; and Gissler, Mika. 2012. Kodin ulkopuolelle sijoittamisen riskitekijät: Rekisteripohjainen tutkimus Suomessa vuonna 1987 syntyneistä. [Risk factors for out-of-home care: A longitudinal register-based study on children born in Finland in 1987] Yhteiskuntapolitiikka 77, 34−52.

- Liukkonen, Johanna; Oraluoma, Elisa; Saksola, Maire; and Välivaara, Christine. 2015. SISUKAS-käsikirja. Työskentelymalli perhehoitoon sijoitetun lapsen koulunkäynnin tueksi. [SISUKAS-manual: Model to support children out of home placement in schools] Jyväskylä: Pesäpuu ry.

- McCrae, Julie S.; Lee, Bethany R.; Barth, Richard P.; and Rauktis, Mary E. 2010. Comparing Three Years of Well-Being Outcomes for Youth in Group Care and Nonkinship Foster Care. Child Welfare 89(2): 229−249.

- Mitic, Wayne and Rimer, MaryLynne. 2002. The Educational Attainment of Children in Care in British Columbia. Child and Youth Care Forum 31 (6): 397–414.

- Oraluoma, Elisa and Välivaara, Christine (eds.) 2016. Sijoitetun lapsen koulunkäynnin tukeminen, SISUKAS-työskentelymallin vaikuttavuuden arviointi [Foster Children at School – Results of Finnish SISUKAS-project]. Pesäpuu ry., tutkimuksia 2. Jyväskylä: Pesäpuu ry.

- Oraluoma, Elisa and Välivaara, Christine. 2017. Sisukas pärjää aina? Moniammatillinen tukimalli sijoitetun lapsen koulunkäyntiin. Oppimisen ja oppimisvaikeuksien erityislehti NMI-Bulletin 27(1): 45–53.

- Räty, Lauri; Välivaara, Christine; Mäntymaa, Sari-Maarika; Saksola, Maire; and Pirttimaa, Raija. 2014. Perhehoitoon sijoitettu lapsi koulussa – lasten psykologisen ja pedagogisen alkukartoituksen tulokset. [Foster Children at School: Baseline Results of Finnish SISUKAS-project]. Tutkimusraportti 2. Jyväskylä: Pesäpuu ry.

- Rosenfeld, Laurence B. and Richman, Jack M. 2003. Social Support and Educational Outcomes for Students in Out-of-Home Care. Children and Schools 25, 69−86.

- Scherr, Tracey G. 2007. Educational experiences of children in foster care: Meta-analyses of special education, retention, retention and discipline rates. School Psychology International 28(4): 419−436.

- Skolen rolle I LUKop for skolen (n.d.) http://gl.sfi.dk/omkring_lukop_for_skolen-12432.aspx (Accessed 2016-12-05).

- Skolfam, n.d. http://www.skolfam.se/in-english/(Accessed 2016-12-05).

- Skolprojekt inom Familjehemsvården. 2009. Resultatrapport och projektbeskrivning. [School project in foster care. 2009: Results and project description]. Ett forskarstött samverkansarbete mellan Skol- och fritidsnämnden och Socialnämnden i Helsingborgs stad år 2005-2008. Helsinborgs stad. http://www.skolfam.se/wp-content/uploads/2010/09/RAPPORT_SkolFam_2009.pdf (Accessed 2016-12-05).

- Statistics Finland, 2015. More comprehensive school students than before received intensified support. http://www.stat.fi/til/erop/2014/erop_2014_2015-06-11_tie_001_en.html (Accessed 2016-12-05).

- Tideman, Eva; Vinnerljung, Bo; Hintze, Kristin; and Isaksson, Anna A. 2011. Improving foster children’s school achievements: Promising results from a Swedish intensive study. Adoption and Fostering 35(1):44−56.

- Trout, Alexandra L.; Hagaman, Jessica; Casey, Kathryn; Reid, Robets; and Epstein, Michael H. 2008. The academic status of children and youth in out-of-home care: A review of the literature. Children and Youth Services Review 30(9): 979−994.

- Välivaara, Christine. 2014. Esipuhe [Foreword]. In Räty, Lauri, Välivaara; Christine, Mäntymaa; Sari-Maarika, Saksola Maire; and Pirttimaa, Raija. Perhehoitoon sijoitettu lapsi koulussa – lasten psykologisen ja pedagogisen alkukartoituksen tulokset. [Foster Children at School: Baseline Results of Finnish SISUKAS-project]. Tutkimusraportti 2. Jyväskylä: Pesäpuu ry.

- Vinnerljung, Bo and Hjern, Anders. 2011. Cognitive, educational, and self-support outcomes of long-term care versus adoption: A Swedish national cohort study. Children and Youth Services Review 33(10): 1902−1910.

- Zetlin, Andrea; MacLeod, Elaine; and Kimm, Christiea. 2012. Beginning Teacher Challenges Instructing Students Who Are in Foster Care. Remedial and Special Education 33(1):4−13.

- Zima, Bonnie T.; Bussing, Regina; Freeman, Stephany; Yang, Xiaowei; Belin, Thomas. R.; and Forness, Steven R. 2000. Behaviour problems, academic skill delays, and school failure among school-aged children in foster care: Their relationship to placement characteristics. Journal of Child and Family Studies 9(6):87−103.