ABSTRACT

Globalisation, migration and super diversity have urged teachers to cultivate their intercultural competence so as to work more successfully in their culturally diverse schools. Previous literature argues that teacher professional development for building intercultural competence plays a pivotal role in improving the intercultural school. For teacher professional development programmes to contribute to the improvement of the intercultural school, we should pay attention to their theoretical framework, content, and format. However, there is a shortage of literature and research that engages in in-depth descriptions of specific teacher professional development courses with an intercultural orientation. In order to bridge this gap, in this paper we critically discuss on a participatory course on stereotypes that we have developed and implemented in Greece aiming to promote teachers’ intercultural development. What stems from our project is that it is only through participatory, collaborative, critical and action-research models of professional development that we may achieve change in teachers’ attitudes and practices, and, in turn, facilitate school improvement.

Introduction

In recent years, globalisation has brought about many challenges to the traditional teachers’ roles, varying from increased migration and cultural diversity, to distance learning, transnational project collaboration, and teachers’ and students’ mobility. In the era of globalisation, teachers are called to adopt teaching methodologies to cultivate intercultural competence, while integrating teaching ethics that stem from a sense of global responsibility outside the strict boundaries of the knowledge economy (Hajisoteriou & Angelides, Citation2016). On top of this, over the last years, Europe has faced a severe refugee crisis. As a result, an unpresented number of refugees move towards various European countries in order to seek asylum and international protection. Arguably, migrant and refugee populations are going to become an integrated part of European societies in the near future. Nonetheless, needs arise, as far as required skills from teachers are concerned, in order to be able to effectively deal with ethnic, linguistic and cultural diversity (Hajisoteriou, Citation2013; Magos, Citation2007; Sales, Traver, & Garcia, Citation2011).

In these super-diverse settings, teachers are called to perform complex roles to meet the needs of the learning environment. They have to deploy methods that cultivate all students’ decision-making and critical-thinking skills to avoid future risks of social exclusion and marginalisation. Additionally, they have to take into account all their students’ identities in their educational practice so as to provide them with equal learning opportunities (Gewirtz & Cribb, Citation2008). Teachers should not exclusively focus on the cultivation of knowledge, rather than at their students’ moral and socio-emotional development. Empowering teachers to endorse these roles through professional development courses contributes decisively to school success and improvement (Hajisoteriou, Karousiou, & Angelides, Citation2018). Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that previous research cautions about teachers being still ill prepared to enhance their students’ hybrid cultural identities and to equip them with the qualities of cultural knowledge and intercultural competence, critical consciousness, interpersonal skills and cultural empathy.

Previous research emphasises that teacher professional development for building intercultural competence plays a pivotal role in the field of school improvement in culturally diverse settings (Hajisoteriou, Citation2013; Hajisoteriou et al., Citation2018). Sales et al. (Citation2011, p. 911) explain that “teachers are a key factor in school improvement and this improvement can and must be encouraged through teacher professional development”. It is one of the key determinants in improving the quality of education, while enhancing all pupils’ learning regardless of their ethnicity, socio-economic background, academic performance, etc. Murillo (Citation2007) argues that factors related to the school staff in general, and teacher professional development in particular, play a pivotal role in improving the school. On a similar route, Hajisoteriou et al. (Citation2018), in their research of the successful components of school improvement in culturally diverse schools, suggest that teacher professional development should have an intercultural orientation. They explain that as schools are turning into “super-diverse” institutions, there is a growing need for teachers to become skilled in building intercultural competence, tolerance and understanding of other cultures, as well as cultural self-awareness. Teachers should be given the opportunity to collaboratively explore their own answers to achieving improvement and to initiate and manage change inside their own culturally diverse schools.

Despite the benefits of teacher professional development for improving the intercultural school, there are still many problems with regard to the design and implementation of successful intercultural professional development programmes (Hajisoteriou, Citation2013). Research conducted thus far cautions about the content, but especially about the models and format of the offered programmes (Ogay & Edelmann, Citation2016; Solarczyk-Szwec, Citation2009). Literature in the field usually engages in an evaluation of the implementation of intercultural professional development programmes which only describes briefly and rather superficially. There is thus a lack of literature that explains, explicitly and in thorough detail, the content and format of such programmes. It is nonetheless for the benefit of the improvement of the intercultural school to engage in in-depth descriptions and critical discussions of specific teacher professional development courses with an intercultural orientation. In order to bridge this gap, we have developed and implemented a participatory course on stereotypes aiming to promote teachers’ intercultural development. This is part of a bigger research project that also examines the outcomes of the implementation of our programme. However, for reasons discussed above, in this paper we place more emphasis on the conceptual underpinnings and the critical description of the development and implementation of our programme. We aim to contribute to theoretical knowledge, but also offer valuable insights into the ways in which we might effectively design and implement intercultural professional development programmes that in turn may enhance school improvement in culturally diverse schools.

Conceptualising teacher professional development

Teacher professional development programmes are rather diverse in terms of their objectives, content, organisational structure and research design (Timperley, Wilson, Barrar, & Fung, Citation2007). With regard to the content, Ogay and Edelmann (Citation2016, p. 388) argue that intercultural teacher professional development usually shows “excessive enthusiasm” for the concept of culture leading to culturally essentialist stances. Nonetheless, so as to combat prejudices, it should rather “foster a dynamic and complex understanding of culture” that draws from cultural hybridity. In more detail, cultural essentialism offers an oversimplistic understanding of culture as it reinforces the argument that different communities have separate, self-contained and unified cultural identities (Hajisoteriou & Angelides, Citation2016). Hence each community demonstrates a single homogenous and enduring culture that is independent of interaction with other groups or the economic and political context. On the other hand, cultural hybridity argues for the dynamic nature of cultures, which are an unstable mixture of not only sameness, but also otherness. Cultural boundaries alter and overlap to create a third space, within which individuals develop multiple or hybrid identities. To this end, Faas, Hajisoteriou, and Angelides (Citation2014) explain that we do not have single or monolithic identities, but we rather employ ethno-national, ethno-local and national-political identities.

With regard to the chosen format of the programmes, this reflects the assumptions made with regard to education per se, the teaching profession and teacher’s roles in contemporary schooling. It reflects the predominant assumptions of what quality education is and what the qualities of a successful teacher consist of. In essence, each teacher professional-development course aims to respond to the fundamental question “What kind of education do we want?” by making assumptions about education policy, teachers’ professional identity, lifelong learning, etc.

In attempting to develop a taxonomy of professional development courses we draw upon Habermas’ theory of cognitive interests. To begin with, the treatment-of-deficiencies approach has a rather positivistic character as it aims to respond to technical-knowledge interests. Secondly, the developmental approach, which emerges from the interpretivist epistemological paradigm, seeks to address practical interests. Lastly, the critical-examination approach seeks to address emancipatory interests by empowering teachers and promoting their awareness of the emancipatory roles played by social and political stakeholders (Adey, Citation2004; Fullan, Citation2014).

Arguably, the technocratic approach, which focuses on “treating” teachers’ deficiencies and gaps in their practices, has dominated the field of teacher professional development. This approach – through its linear design and hierarchical organisational structure – attempts to transcend theory to practice (Day, Citation1999; Hammerness et al., Citation2005). However, previous research cautions about the weakness of such traditional forms to meet the needs of an ever-changing educational framework, while recording teachers’ negative attitudes towards them (Alton-Lee, Citation2003).

Accordingly, a debate has arisen concerning the design of teacher professional development courses in order to address teachers’ needs (as perceived by them) and the needs of the school unit. Therefore, in recent years, more dynamic, reflective and participatory forms of professional development courses have gained momentum, aiming to empower teachers through their active participation. The focus is on maintaining a high degree of teachers’ autonomy, but also on pursuing the use of strategies, such as collaborative learning and reflection (Fullan, Citation2014). Teachers employ an interventionist role as they redefine and reformulate their teaching practice through processes of critically reflecting, reading, and analysing the educational and social reality (Adey, Citation2004; Hilton, Assunção, & Niklasson, Citation2013). Courses that use action research methodology entail a classic example of the dynamic form of teacher professional development. Action research allows teachers to analyse, understand and solve issues and problems that they face in their everyday practice (Angelides, Georgiou, & Kyriakou, Citation2008; Magos, Citation2007). Self-reflection has a central position in action research, as teacher-practitioners are the ones enquiring into their practice, identifying their “struggles”, analysing and understanding problematic situations, investigating possible solutions and finally resolving these issues. Action research may also have a collaborative form in contrast to the often solitary character of teacher action. Ιn this form of professional development, theory is not represented as the objective truth that has to be put into practice. On the other hand, theory serves in reformulating the way we understand and experience educational practice, while such reform comes to enrich theory itself (Ainscow, Citation1999; Alexandrou & Swaffield, Citation2016).

In conclusion, literature claims that only through critical and participatory approaches we may free teachers from their prejudices and stereotypes, while transforming their understanding (Solarczyk-Szwec, Citation2009). This assertion brings us to the question: What kind of teacher professional development do we need for improving the intercultural school? In the following section, we discuss the components of successful intercultural teacher professional development.

Teacher professional development with intercultural orientation

The ever-changing cultural character of schools raises concerns about teachers’ preparation to teach in super-diverse classrooms. Arguably, the extent of implementation of any educational policy with intercultural orientation depends on teachers’ ability to meet the needs of the increasingly diverse school population. An examination of European Union (E.U.) policies on teacher education points out the importance of cultivating teachers’ competence to successfully “manage” cultural diversity in their classrooms, which is recognised as an important element of European teachers’ profile. Since 1993, the E.U. has brought forward the development of teachers’ multilingual and intercultural skills, intercultural respect and understanding of others (Faas et al., Citation2014). Teacher professional development with intercultural orientation aims to empower teachers to work in more inclusive ways, and therefore transform their schools into more inclusive entities. What Ainscow, Booth, and Dyson (Citation2006) explain is that by becoming more inclusive, schools improve, and vice versa; by improving, schools become more inclusive of diversity. Inclusion is bounded to “equity, participation, community, compassion, respect for diversity, sustainability and entitlement” (Ainscow et al., Citation2006, p. 23).

Arguably, there is an imperative need to organise and implement teacher professional development courses which may lead to the development of teachers’ intercultural competence, meaning the ability to operate effectively in culturally diverse settings. In the context of this research, we define intercultural competence as having the following dimensions: cultural knowledge, intercultural values and interpersonal skills. To begin with, cultural knowledge is not exclusively the knowledge of a specific culture or cultures. Cultural knowledge is rather the knowledge of how cultural identities are formatted, in what ways social groups function, and what are the components of intercultural interaction. Furthermore, cultural knowledge refers to the updated knowledge of the changing policy circumstances, such as current public and education policies addressing cultural diversity. Moving a step forward, intercultural values refer not only to cultural empathy, but also to other first-order values such as “autonomy, criticality, care, tolerance, equality, respect and trust” (Thrupp & Willmott, Citation2003, pp. 28–29). Lastly, interpersonal skills entail important sets of skills that are necessary for building and sustaining effective interpersonal relationships, face-to-face interaction, and team collaboration in culturally diverse school environments (Arasaratnam & Doerfel, Citation2005).

To this end, the notion of cultural identity should have a central position in all intercultural professional development courses. To begin with, a fixed and homogeneous form of cultural identity is incompatible with the task of interculturalism. Cultural identity does not only refer to individuals’ affiliations with their communities, but also the relationships formed between individuals and their communities that further shape their personal definitions of their cultural identities. Interculturalists stress the dynamic nature of cultures, which are an “unstable mixture of sameness and otherness” (Leclercq, Citation2002, p. 6). Cultural boundaries alter and overlap to create a third space, within which natives and immigrants develop multiple or hybrid identities (Hajisoteriou & Angelides, Citation2016). Bhabha (Citation1995) defines hybrid identities as “mixed identities”, which derive from the interrelationship between diasporic or ethnic affiliations and political identities (e.g. such as being European). The multidimensionality and multiplicity of identities reflect the shifting nature of society. As society shifts, identities are not fixed, stable or of a binary nature (i.e. Black or White) but are negotiated and renegotiated in a process of cultural syncretism. Faas (Citation2007a, Citation2007b) argues that individuals do not have single identities, but employ ethno-national, ethno-local and national-political (e.g. national-European) identities. Thus, he urges theorists and researchers to reconceptualise their understanding of identity formation in order to acknowledge the interconnections between ethnic and political citizenship identities.

Brah (Citation1996) defines identity as a process that allows for multiplicity and contradiction between shifting identities. Nevertheless, he contends that identity is “that very process by which multiplicity, contradiction and instability of subjectivity is signified as having coherence, continuity and stability, as having a core … that at any given moment is enunciated as the ‘I’ ” (p. 124). Thereafter, Brah suggests that individuals could potentially perceive their multiple identities as cohesive and feel strongly about them. In this paper, identity is being defined as a constantly evolving, dynamic phenomenon which is neither fixed, static nor decontextualised following Gee’s (Citation2005) perspective that identity is not “once and for all”; instead it is “settled provisionally and continuously, in practice, as part and parcel of shared histories and ongoing activities” (p. 25). Identity transforms over time under the influence of several dynamics. Consequently, all the technological, economic, ideological and political changes as well as demographic shifts in the population affect to a great extent individuals’ experiences and interactions with and within the social setting.

Previous literature points out that teacher professional development with intercultural orientation should have three interrelated dimensions; namely, ethical orientation, efficiency orientation and pedagogical orientation (Jokikokko, Citation2005). Firstly, ethical orientation refers to the values and interpersonal attributes, and positive orientation towards cultural diversity. Secondly, efficiency orientation includes the organisational skills and abilities to act in various roles and situations. Lastly, professional development should also have a pedagogical orientation that encompasses intercultural, inclusive and socially just pedagogical competences (Jokikokko, Citation2005). To this end, Conklin (Citation2008) asserts that professional development with intercultural orientation should model compassion. She explains that only through such “pedagogy of compassion”, teachers’ professional development may have a transformative, critical and justice-oriented character.

Such a process has as its starting point one’s “self” and the awareness of subconscious assumptions that determine teachers’ choices and educational practice, in general. These subconscious assumptions are shaped, to a large extent, by teachers’ stereotypes. Therefore, intercultural teacher professional development should play a significant role in challenging teachers’ stereotypes. A stereotype is “a fixed, over generalised belief about a particular group or class of people” (Cardwell, Citation1996). Fiske (Citation2010) defines stereotyping as the application of an individual’s own thoughts, beliefs and expectations to other individuals without first obtaining factual knowledge about the individual(s). Stereotypes infer that individuals shares a whole range of characteristics with all other members of their group. For this reason, stereotypes lead to the creation of in-groups and out-groups on the basis of social categorisation, which in turn leads to prejudicial attitudes (Cardwell, Citation1996). In the context of this research, when we refer to stereotypes we mean “heterostereotypes” that are stereotypes targeting the out-groups. Although most stereotypes tend to bear negative impressions, stereotypes conveying a positive and respectable set of characteristics also exist.

Moving a step forward, the development of intercultural competence requires a professional development process that leads to a critical review of personal assumptions, pedagogical and didactical approaches, and change of consciousness (and the way of becoming self-aware), while gaining an insight into the action needed towards the mitigation of their reproductive role (Gallavan & Webster-Smith, Citation2009). Thus, this intervention can be done through professional development programmes, which transcend traditional schemes of “transferring” academic knowledge or “learning” teaching skills. Such programmes view learning as a personal-individual experience, allowing the formation of learning communities, in which teachers engage in activities that not only lead to the construction of knowledge, but put under critical examination teachers themselves (Villegas & Lucas, Citation2002). It is an approach to teacher professional development which emphasises the social nature of knowledge and its dependencies, but also the previous experiences of the subjects leading them to the construction of new knowledge. The key element of such an approach is to guide teachers through an examination of societal and personal stereotypes by applying techniques that promote reflection and self-awareness. Due to the central role of attitudes and perceptions, this form of teacher professional development is a prerequisite for the development of a critical self-examination schema that puts under investigation the subjects’ personal theory and draws interconnections between theoretical knowledge and teaching practice (Dooly & Villanueva, Citation2006).

According to Deardorff (Citation2008, Citation2009), the intervention at the subjective level (individual) entails the first step towards the development of an individual’s intercultural competence, leading to the level of interaction between subjects. However, the intervention at the level of perceptions and attitudes entails the cornerstone of individuals’ efforts to exceed the “safe zone” of their cultures and to communicate with others. For this to happen, individuals should be confronted with questions such as: “How open am I to diverse cultural, religious or other traditions?”; “Do I endorse unevidenced claims or anticipate events and situations?” This means that to enable individuals to effectively respond to cultural diversity, they should, first and foremost, “face” their consciousness, so as to change their entrenched attitudes, perceptions and beliefs about diversity. International literature points out the importance of teachers’ attitudes and perceptions, mainly because earlier beliefs function as a “perceptual filter” while receiving new information or knowledge (Alexandrou & Swaffield, Citation2016; Hammerness et al., Citation2005). Previous literature also explains that earlier beliefs are so strong that often the new information is used to reaffirm existing beliefs and attitudes, rather than challenging and changing them (Alton-Lee, Citation2003).

The theoretical framework of this research is informed by the assumptions imbuing professional development courses that set, in the centre of the process, teachers as people who have specific experiences, values and perceptions, and a certain biography, which influence and shape not only their personal but also their professional life (Blandford, Citation2014; Knobel & Kalman, Citation2016; Timperley et al., Citation2007). The teacher endorses particular, and even demanding, roles in terms of the expectations and rules set by society, which, however, they experience in a personal way. Their values, opinions and attitudes, and thus their personal identity, shape their professional identity. Accordingly, all these aspects of their personal identity influence the ways they understand their profession, in terms of the specific choices they makes and the decisions they take.

The intercultural-competent teacher is nothing more than an aspect of the critical self-reflective teacher, who understands the sociopolitical aspects of their teaching practice, as they are concerned about the goals and content of the curriculum, the learning process, and the educational and social roles of school (Hajisoteriou et al., Citation2018; Leeman & Ledoux, Citation2003). The concept of the critically reflective teacher that we use here contrasts with the concept of the teacher as a technocrat, who perceives the educational process as a set of “technical” issues and is primarily focused on the undiversified implementation of the curriculum (Schön, Citation1983; Timperley et al., Citation2007).

Taking into consideration both the theoretical underpinnings, the desired objectives and the successful components of teacher professional development with an intercultural orientation, we developed a participatory course on stereotypes in order to build teachers’ intercultural competence that in turn would help them to work more inclusively and thus improve their intercultural schools. In the sections below, we critically describe, discuss in detail and reflect on the methodology of this research and the format and content of this course.

Methodology

In this study, we implemented an action research programme in order to improve teachers’ intercultural competence. By the term “action research” we mean that process of inquiry where teachers work in collaboration in their own workplaces for the whole process of inquiry (initial design, data collection and analysis, conclusions, implementation of practices that arise from conclusions) for the purpose of improving their practice (Ainscow, Citation1999).

The professional development course had two distinct phases or levels: it began with the exploration of personal stereotypes and attitudes towards diversity, and then it focused on the connection to practice. At the same time, the programme aimed at promoting teachers’ active involvement in, firstly, understanding classroom realities, and thereafter in designing and implementing teaching interventions based on the initial observations. Moreover, the reflection that followed the teaching interventions created the conditions that, in the long run, would have an empowering character. The course was launched in Athens, Greece, from January to June 2017. The participants consisted of 29 teachers. In more detail, the sample consisted of 7 teachers from pre-primary and 22 teachers from primary schools, of whom 5 were men and 24 were women. Teachers expressed interest in participating in the training programme after we communicated the course to their schools. Therefore, their participation was voluntary on the basis of their professional development needs and educational interests.

Upon the completion of the course, and in order to examine the results of the professional development course, we carried out semi-structured interviews by the end of the process. The semi-structured character of the interview provided flexibility in the data collection process. During the interview process there was a body of questions and, depending on the interviewee’s responses, the researcher could change their course or add further clarification questions (King, Citation2004). We aimed to follow the course of the interviewees’ thoughts and to analyse further issues that had arisen. The fact that we did not used a standardised form of interview allowed the participant teachers to respond in a personal style and express their thoughts and attitudes and the prospects of their action. Teachers were asked to respond to questions about the positive and negative elements of the course, as well as the degree of fulfilment of their expectations. Nonetheless, the course focused on a topic area that is rather difficult to assess in terms of its effectiveness with regard to combating stereotypes.

It is noteworthy that all interviews were audio-recorded. With regard to the data analysis process, we initially fully transcribed the interviews so as to record the information provided by the interviewees, both through the questions and other spontaneous comments. Thereafter, we used the method of “Interpretive Content Analysis”. Content analysis is considered to be an effective and appropriate research tool used to identify the existence of specific words or meanings in a text. Qualitative research acknowledges the researcher’s independence and ability to form the collected data by analysing and interpreting them (Creswell, Citation2002; Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2000). As data were categorised, categories and subcategories were formed, and, based on these, the content was also categorised. For the interpretation of the results, we used descriptive meanings of synthesis and analysis to identify similarities and differences between and between categories and subcategories. Lastly, we used the contextual interpretation in order to examine how the meaning of the text (interview) has been influenced by the historical and sociopolitical context.

An example of a participatory professional development course on stereotypes

What we have discussed above is that in order to foster school improvement, we should build schools’ and, by extent, school actors’ capacity for managing change (Hopkins, Stringfield, Harris, Stoll, & Mackay, Citation2014; Thoonen, Sleegers, Oort, & Peetsma, Citation2012). Hajisoteriou et al. (Citation2018) claim that for school actors, and particularly teachers, to initiate and manage change in their culturally diverse schools, we should build their intercultural competence. Taking into account what we have discussed above, we designed and implemented a professional development course aiming to develop teachers’ intercultural competence by focusing on stereotypes and their role in the educational process.

The programme had the form of a distant asynchronous course. It provided a mixture of synchronous and asynchronous professional development activities, where teachers were directly involved in synchronous activities only at the beginning and at the end of the programme. In the meantime, teachers planned, piloted and implemented interventions in their school, while at the same time they had online communication with the course facilitators, who acted as their critical friends (Knobel & Kalman, Citation2016). This form of professional development combines face-to-face and distance-learning activities, while also having a practical dimension, since participants are asked to apply and implement in their classrooms what they learn and to present their work in the form of a course assignment.

One of the benefits of this form of professional development is the fact that it involves an experiential orientation based on certain theoretical assumptions, which, however, are redefined through practice and action. Therefore, a key element of this course is that it draws upon reflection on action. The course activities were designed in order to support teachers to reflect on their practices and the underlying assumptions behind their practices. What is important, apart from the implementation of specific teaching interventions, is that teachers gain an insight into the educational reality, and interpret its contradictions, dysfunctions and dead-ends so as to suggest improvements that they will actually implement (Adey, Citation2004; Blandford, Citation2014). In this approach, the teacher becomes the researcher, who observes and analyses their teaching practice, in an effort to understand their own educational choices along with the other aspects of the educational process (Altrichter, Somekh, & Posch, Citation2001). This approach aims to link theory to practice by implementing specific activities that draw upon experience or its representation, and, accordingly, to link theory to the development of a reflective process that leads to empowerment and self-improvement, and, by extent, school improvement. Connection to practice should be accompanied by reflection on the emotions caused by practice leading to the re-evaluation of practice itself, which can either lead to the creation of new knowledge or to the change of attitudes and behaviours (Day, Citation1999; Fullan, Citation2014).

Reflections on past experiences and how they affects future practices, as well as the disclosure of such reflections, are essential elements of this approach of professional development, since they lead to the legitimation of experience, allowing the subjects to express their perceptions, and, consequently, to shape specific identities (Timperley et al., Citation2007). Developing reflection and self-awareness has been attempted through activities and methodological techniques including critical self-exploration schemes such as autobiographical narratives, expressing one’s position or opposition, etc.

The first part of the professional development course consisted of two meetings in a period of one month. At the first meeting, we presented the professional development programme that is discussed below. During the meeting, we also carried out presentations about the basic theoretical principles on stereotypes, biases, experiential learning, and the pedagogical principles and teaching techniques underlying the development of interventions for deconstructing and combating stereotypes. Moreover, we implemented experiential activities allowing the participants to trace various stereotypes, and to identify how these stereotypes affect consciously and/or subconsciously the educational process. In their initial training, teachers were also actively involved in the development and implementation of teaching interventions as part of their participation in classroom-simulation processes, and through the implementation of lesson plans and scenarios in their classrooms – for the purposes of an assignment. At the second meeting, the participants presented their teaching interventions and, in the discussion that followed, they highlighted the contributing factors to successful implementation, and the barriers to their efforts that concerned the micro-level of the classroom, the mezzo-level of the school unit and/or the macro-level of the structures of the educational system. The goals of the professional development programme were the following:

Teachers should:

understand the function of stereotyping mechanisms;

understand the function of the classroom as a group and the way interpersonal relationships are formed in super-diverse environments;

reflect on their own stereotypes and the ways these influence their pedagogical views and their teaching choices;

implement techniques for examining classroom interactions; and

get acquainted with strategies regarding the development and implementation of experiential learning approaches.

As we have already discussed, the professional development programme primarily aimed to highlight relationship dynamics in the culturally diverse classroom, the role of stereotypes as an element of personal identity, and the importance of stereotypes in shaping expectations.

First phase

The first phase began with the exploration of the participants’ expectations in order to reflect upon and discuss their personal theories. Since group bonding has been of great importance for the success of the initial training, the first meeting started with a “get to know each other” activity. All participants asked another participant two questions, and then presented the profile of their peers to the whole group. Thereafter, at both the individual and group levels, the participants noted down and discussed what they wished or wished not to happen during the professional development programme. According to their views, the groups compiled a list of rules that had the role of a team contract. Teachers’ expectations were examined by completing a worksheet with incomplete phrases. What emerged from their responses as a top priority was the improvement of specific aspects of the educational reality, and the need for an experiential orientation of the programme, while teachers expressed their opposition to theoretical courses decoupled from practice.

There followed a discussion about the concept of identity, its dynamic and evolutionary character and the possibility of coexistence of many diverse identities in the same social context. The discussion attempted to clearly spell out the fact that subjects are involved in communicative circumstances and not with identities that have a fixed and rigid character. The concept of identity is a “construction” based on specific historical, social, economic and political conditions, while it is linked to the specific direct and contemporary experiences of the subjects, thereby exerting a decisive influence on their self-determination, as well as on their interpersonal relationships.

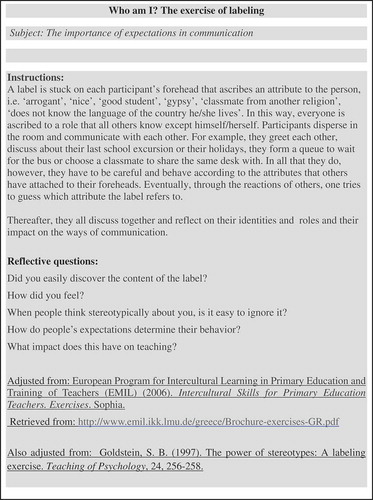

To understand the dynamic nature of identity, teachers were divided into groups that dealt with a case study, having as their primary goal to highlight the comprehensive nature of the subjects’ identities. The case study is a participatory educational process that allows an in-depth study of a phenomenon. In we provide an example of the activities that we used.

The working groups identified diverse versions of labels and identity, and by drawing upon the follow-up reflection questions they studied the development of hybrid identities in the case of their students. They also examined whether they take into account the hybridity of cultures and identities in the interactive context of their classroom’s “escape” from pre-fabricated schemes. As students enter the communication process, their identities are evolving and mutating while they do not maintain “unchanged” personal traits. The plenary discussion focused on students’ identities, their characteristics, and the diverse orientations that are shaping them. Teachers reported incidents about their students and their diverse attitudes towards their family cultures, highlighting the multifaceted and active character of individual identities. The follow-up reflection questions were the following:

What identities does the school aim to promote?

Is there a specific one? Which?

To what extent education may recognise students’ “real” identities?

The module concluded with the assumption that any intervention in the classroom should start from understanding students’ “actual” identities and the grid of relationships that is developed.

As we discussed in the theoretical part of the first phase of the programme, stereotypes are a key factor in determining the quality of interaction in the classroom. They are characterised by their resilience, generalising character and regulatory role. In our professional development programme, our stereotype-analysis approach had a gradual and evolutionary character starting from their characteristics, their reproduction mechanisms, their study as an element of teachers’ personal theory that determines their expectations and behaviours, and the development of combat strategies at the classroom level.

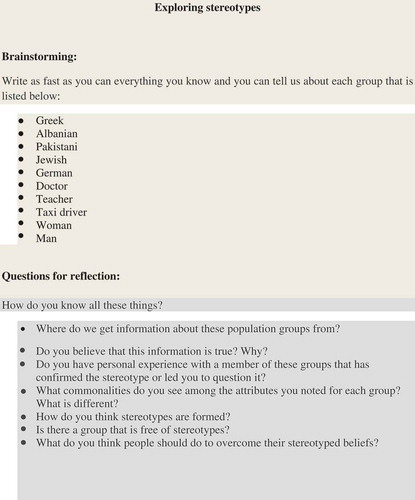

In the next stage, teachers themselves examined and reflected upon their own stereotypes. In their groups, they had to record stereotypes that relate to specific ethnic, cultural and social groups. provides an example of the activities we used to explore the participants’ stereotypes and help them reflect on those.

The groups recorded these stereotypes through the brainstorming method so as to provide spontaneous responses to specific questions such as: “Have you met someone belonging to the groups described? If so, does this person fit in the stereotype?”; “How did you become aware of these stereotypes?” In order to provide a more interactive and participatory character in the recording of stereotypes, the groups also carried out an experiential exercise with the same goal. The follow-up discussion focused on clarifying the source of these stereotypical assumptions, to what extent they have an objective basis and, above all, how difficult is it to avoid stereotypes. Both the activities and subsequent discussion allowed the participants to understand that stereotypes exist as part of the individual’s cognitive function – sometimes consciously and other times subconsciously – while they emerge as collective knowledge that is transferred from generation to generation, but most importantly it draws upon the constructed validity of self-evident and scientific certainty that cannot be disputed.

Thereafter, we defined the fundamental theoretical principles underlying stereotypes, their dynamics and the ways that they influence human behaviour. In order to present our theoretical framework in an interactive manner, we carried out an activity called “statement game” that ensured teachers’ participation in the debate and also in the formulation of the theoretical principles, which they had to discover. In this activity, teachers voiced their assumptions about what stereotypes are, what their dynamics are, how stereotypes are formed and in what ways they can be deconstructed. Teachers expressed their agreement or disagreement with the given statements by raising a coloured card. A discussion followed after each statement. If someone’s view about the original statement changed, the participant changed the chosen coloured card and switched groups. In this way, the participants identified the key characteristics and mechanisms of stereotype construction, and thus discussed the basic theoretical assumptions underlying our professional development course.

Our next activity had a dual purpose: on the one hand, to indicate that each individual’s identity has a multidimensional character; on the other, to highlight that each individual’s identity draws upon certain stereotypes, which, however, do not have an objective basis. The participants were asked to recall positive and negative incidents associated with their identity and the stereotypes attached to it. What has become clear is that all of us can be subject to indefensible thinking with negative consequences, but also that stereotypes do not correspond to the reality as they are subject to generalisation and traits-attribution.

We aimed to help the participants gain an insight into and reflect on their personal opinions. Therefore, the participants were asked to choose – from a list of stereotypical statements – one statement that they accepted as valid and rightful for the specific social group it referred to. The participants wrote down the rationale leading them to their specific selection and the ways they believed that the specific stereotype influenced their behaviour towards the members of the specific social group. According to their choice of statement, teachers were placed in the same team. Each team attempted to develop an action plan aiming to change the perception for that group. The implementation of this activity was of particular importance because it led teachers to a self-conscious preoccupation with their personal assumptions that, until then, were rather subconscious and “automatic”. This activity was in fact an autobiographical narrative that sparked reflection by putting on the table stereotypes which until that moment were considered as self-evident and given. It is notable that teachers primarily chose stereotypes associated with gender or ethnicity. In their proposals for combating the specific stereotype, they inter alia mentioned a search of relevant information, the presentation of examples that counteract the stereotype, and contact with people of the specific group.

Using the same methodological approach, the discussion shifted to the role of stereotypes in the educational process. Teachers were asked to recall an incident in which they felt that their behaviour was biased towards some of their students. The discussion concerned the characteristics of biased behaviour, the causes of prejudice and the possible consequences for the student. We then explored the role of expectations in shaping specific behaviours during the educational process. The team came to the conclusion that often the prevailing views of teachers, such as their subconscious stereotypes, influence their choices, expectations and attitudes towards their students. We concluded with an overall discussion on the role of stereotypes in the educational process and the formulation of general conclusions.

Second phase

The second phase of the professional development course aimed at exploring interaction and communication in the classroom, the specific characteristics of intercultural communication, and the role of stereotypes in shaping these relationships. Teachers, in a reflection process, were invited to think about their students, the relationships they develop and the factors that determine the quality of these relationships. Indicative questions used for reflection are:

Who are my students?

What do I know about them?

How do I negotiate their diversity?

Am I learning something from them?

How do I handle conflicts due to diversity?

How do I reinforce collaboration in my classroom?

Do I use specific strategies and techniques to combat stereotypes?

How do I encourage dialogue?

The discussion that followed concerned the classroom as a group, its structure and function, the ascription of specific roles, and the shaping of relationship dynamics. During the discussion, teachers were invited to reflect on their experience regarding the conditions prevailing in their classrooms, how relationship dynamics are shaped and whether subgroups (cliques) are formed in their classrooms and on what basis. Teachers also discussed the ways they intervene and manage conflicts and communication problems. The reflection process highlighted teachers’ views, but also crystallised that the educational process often has an automatic character that “traps” the involved subjects into established images and roles, which do not allow a critical approach to the relationships developed in a multicultural class with “intense” dynamics.

Thereafter, we presented the methodology for examining classroom relationships and school climate. Teachers practised studying a sociogram, as well as examing a survey regarding the climate in one classroom, in order to identify the dimensions of this climate. Using sociometry is an essential tool for detecting the quality of relationships that exist but also the criteria on the basis of which groupings are made (Bikos, Citation2004). Sociometry allows for the exploration and description of the psychological structures that exist and determine a social phenomenon, ultimately aiming at changing grouping procedures in order to improve the functioning of the groups (Maisonneuve, Citation2001).

Sociometric techniques provide information about the sociometric characteristics of the group members, the interpersonal relationships they develop (sympathy, friendship, antipathy, antagonism, hostility, hatred, indifference). Additionally, they allow the diagnosis of friction and conflict within a group, while contributing to the knowledge of the motivation underlying individuals’ behaviour and revealing the underlying conflicts and contradictions among the members of the group (Tsiplitaris, Citation2004).

Teachers applied the sociogram in a process of class simulation. They set a sociometric question according to which they decided on their preferences and rejections. Alternative forms of sociometric queries and sociograms were presented, so that teachers could become familiar with reading sociometric tables. Then teachers examined the sociogram in order to identify different categories of sociometric status (popular students, average students, rejected students, etc.) and to detect already formed communication networks or conflicts. The discussion that followed focused on the importance of drawing upon the knowledge of classroom interactions and social relations in education. Understanding group dynamics and using this knowledge may promote learning and other social processes. By delineating the importance of classroom dynamics and interaction, the discussion focused on the barriers that emerge when participants in a communicative situation come from diverse cultural backgrounds. Our main objective was for the participant teachers to realise the cultural dimensions that define communication in a culturally diverse classroom.

The final phase of professional development concerned the role of stereotypes in shaping students’ relationships and in the development of strategies to combat them. We introduced the basic principles of experiential learning as our theoretical framework of teaching. Experiential learning entailed the basis for the implementation of specific activities, but also for the planning of actions to deconstruct stereotypes by teachers themselves. Our theoretical presentation paid attention to the value of experience in the learning process by examining concrete implementation models (e.g. the Kolb cycle), as well as pertinent methodologies of designing and implementing experiential learning techniques such as role-playing, case study, brainstorming, etc. (Timperley et al., Citation2007). We also placed emphasis on the methodology of reflection as a key part of these activities.

After our theoretical presentation, the participant teachers were called to actually implement specific experiential activities. The activities developed in this phase of the professional development course aimed at the deconstruction of stereotypical thinking and the acceptance (or rejection) of “the other” on the basis of objective data. Teachers in their groups were called to implement various activities in a classroom simulation process by drawing upon the basic principles of experiential learning. Therefore, in this phase, we applied techniques aiming at empathy development and techniques that contribute to the recognition of constructed images about “the other” in order to combat the depersonification created by stereotyping through robust categorisation. We also launched activities involving life narration either on behalf of one’s “self” or on behalf of the “other” aiming to demonstrate the multiplicity of viewing, the one-dimensional character of single interpretation, but also the importance of developing empathetic understanding in the development of relationship with the “other”.

In the following stage, we gave instructions about the practical implementation, which entailed an organic part of the professional development course. Teachers were also asked to write an essay focusing on the implementation part. Then, the participants had to apply techniques for examining the relationships that were formed in the classroom and then to design and implement specific instructional interventions aiming at combating stereotypical thinking, recognising and valuing diversity, and developing empathy. The examination of the relationships that were formed in the classroom was mainly carried out by means of sociograms or observation schemes.

During the interval between the two meetings, we carried out the long-distance part of our professional development course. We sent detailed instructions to teachers on how to prepare their teaching interventions. The teachers prepared a draft of their interventions, on which they received feedback. In each teaching intervention, teachers had to highlight the intercultural perspective at the level of both goals and objectives, and activities, building upon what had been discussed in our meeting.

At our second meeting, the participants presented their teaching interventions including worksheets, children’s assignments, and an evaluation of the implementation and of the impediments and facilitators of their work. In the discussion that followed, each teacher, with their reviews, comments or remarks, worked as a “critical friend” for the others. In this way, the participants identified the factors that contributed to the implementation of their interventions, and the obstacles they encountered either at the micro-level of the classroom and school unit or at the macro-level of the educational system structures. The questions raised were:

What obstacles did you encounter during the planning and implementation of the intervention?

Where there any issues raised that were not included in the initial design?

Did you reconsider or reaffirm any of your initial views and opinions after the implementation of the teaching intervention?

What did you learn from the whole process?

The implementation of the course

The process of school improvement is unique for each school because each school’s context and culture is unique. This means that schools have to address these processes in diverse ways as there is no recipe to be proposed for all schools. As we have already discussed, intercultural teacher professional development is a necessary component for improving the culturally diverse school (Hajisoteriou et al., Citation2018). As such there are no universal remedies of teacher professional development, rather than programmes of professional development which are designed according to the school’s and teachers’ needs. To this end, the implementation of our intervention highlighted the importance of participatory educational activities that stem from teachers’ needs, while having a learning-by-doing orientation. Such teachers’ professional development courses may bring about changes in teachers’ perceptions and attitudes regarding their personal and professional identities, and their collaboration with colleagues, but also their teaching practices.

At the centre of our professional development course were teachers and their perceptions and preconceptions, which in turn influenced the development and organisation of our interventions. Such an approach is of particular importance as it views the teacher as a whole, whose professional and personal identities are interdependent. The examination of stereotype formation mechanisms and processes and the inquiry for teaching practices that may break through stereotypes was initiated by teachers themselves; teachers came to acknowledge themselves as stereotype bearers, while reflecting on how their stereotypes were represented in educational processes by influencing their expectations. Nevertheless, in recognising the barriers to this form of professional development course, teachers are not always willing or adequately prepared to self-reflect on their stereotypes as such an approach is not widely known or used. Accordingly, sometimes there were difficulties in the process of teachers’ self-reflection on stereotypical assumptions and on the ways they affect their teaching practices.

An important contribution of our professional development course is that it provided for a link between theory and practice, while creating a spirit of collaboration among the participants. The methodology that we adopted has allowed us to observe that it is not only important to reach cognitive goals or implement specific technical teaching skills. It is also necessary to promote and develop teachers’ familiarity with experiential-learning techniques and models of collaborative learning. Therefore, beyond the achievement of its objectives, each professional development course should aim at the development of a collaborative network, which will operate as a learning community. In our course, teachers were “educated” to work collaboratively, which is not a common practice in an educational system such as the Greek one that, at least until now, does not foster collaboration.

An essential aspect of our course was also the reflective discussion that took place during the second meeting. Although this discussion was initiated by the specific activities/teaching interventions that were implemented in real classroom settings, it came to redefine theory by addressing the questions of what intercultural education is, to what extent its implementation may lead to the deconstruction of stereotypes, what teaching strategies may promote its goals, and what are its potentials and its limitations with regards to school improvement.

In conclusion, it is rather difficult to assess our intervention in terms of its effectiveness in stereotype deconstruction. Nonetheless, at the cognitive level, our participants appeared to understand the meaning of stereotypes, the mechanisms of stereotype formation, and the influence of stereotypes in the development and quality of interpersonal relationships. Moreover, teachers came to recognise the basic principles that should permeate the operation of a classroom as a group and allow the formation of positive relationships. They also developed an in-depth understanding of the basic principles of experiential learning and teaching and the uses of collaborative-learning strategies and techniques. In terms of skill development, the participant teachers were actively involved in using research methods and tools for examining classroom dynamics including sociometric tools, as well as in designing and implementing teaching approaches that may contribute to stereotype deconstruction. Last but not least, because of their participation in the activities of the course, teachers engaged in a reflection process with regard to both their personal identities and their students’ identities, but also how these identities are formed. They thus became involved in a process of self-awareness and introspection that led to a critical reflection on unquestionable assumptions, both on personal and professional levels.

Conclusions

Nowadays, contemporary phenomena such as the refugee crisis and extended migration have stimulated the ever-changing character of student population in many schools across the world. The prevailing conditions, problems and needs that these schools face are context-specific and may be better addressed at the school level. Accordingly, top-down, centralised and one-size-fits-all approaches to teacher professional development are inappropriate for improving the intercultural school (Hajisoteriou et al., Citation2018). What we suggest is that in order to improve the intercultural school, it is important for schools themselves to integrate internal teacher-education systems that have an intercultural orientation. It is noteworthy that a common feature of successful education systems, according to international evaluations such as the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) and Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) (e.g. Finland, South Korea, Singapore, Canada, Japan), is that in these systems schools have built-in teacher-development systems. This process may help schools not only to have their teachers developed, but also to assess themselves, while gradually becoming autonomous from external evaluations that are rather decontextualised.

Moving a step forward, both the content and the format of intercultural professional development courses are particularly important so as to free teachers from their prejudices and stereotypes, and build their skills to successfully work in intercultural schools. What stems from our project is that it is only through participatory and critical models of professional development that we may achieve change in teachers’ attitudes and practices, and in turn facilitate school improvement. For designing successful intercultural programmes of teacher development we suggest taking into consideration Solarczyk-Szwec’s (Citation2009, pp. 22–23) principles, namely:

orientation for target groups, orientation for participants, work on interpretation patterns, adapting classroom language to participants, crossing of perspectives of teacher and student, orientation for objectives on learning, confrontation with content of education, self-education, integration of general professional and civic education, infuence of emotions on teaching – learning process, orientation for doing, aesthetisation, optimum use of time, probability of mistake, use of humour.

Moreover, successful and effective teacher development with intercultural orientation presupposes the development of both teachers’ intercultural awareness and competence (Hajisoteriou, Citation2013). Accordingly, intercultural professional development programmes should aim towards both teachers’ theoretical and practical preparation to manage diversity in their schools and classrooms. What we argue is that programmes aiming to combat racism, xenophobia and discrimination should help teachers to, on the one hand, critically reflect on issues of culture and stereotype, and, on the other hand, acquire a repository of teaching methodologies “appropriate” for diverse settings that are based on sociometric analyses and the principles of experiential learning. In the context of this project, involvement in a participatory course on stereotypes allowed teachers to reflect on the meaning of culture and their own personal stereotypes, while having the opportunity to exchange diverse ideas on the topics of classroom dynamics and interaction, marginalisation reduction and inclusion that eventually influenced their practice in their schools and classrooms. As the participant teachers engaged in designing and implementing teaching interventions, they improved their intercultural practice at the school and classroom level.

In conclusion, collaborative action research may help schools achieve the goal of sustaining built-in critical, participatory and transformative teacher professional development with intercultural orientation (Hajisoteriou & Angelides, Citation2012). Hargreaves (Citation2012) calls for collaboration as an essential element of a self-improving school system. Collaborative action research may adjust intercultural teacher professional development to the school context by acknowledging various school factors including school climate, teamwork, community involvement, leadership, resources, teachers’ working conditions, teacher–student relationship, and students’ diverse backgrounds (such as socio-economic status, prior achievement, gender and other personal characteristics). Murillo (Citation2007) claims that only by acknowledging these factors, schools may improve. Sales et al. (Citation2011, p. 911) explain that action research as a professional development process may “encourage professional and school culture towards an intercultural and inclusive approach” by challenging teachers’ pre-existing deficit theory perspectives and empowering them as leaders for school change. By integrating collaborative action research in their built-in teacher-education systems, schools may thus become communities of learning and practice that offer opportunities to teachers for joint learning and application of learning on intercultural issues; developing a sense of ownership amongst participants; enhancing teachers’ commitment to intercultural education and inclusion; producing and disseminating tacit knowledge; and reflecting on teachers’ intercultural practices (Angelides et al., Citation2008; Hajisoteriou & Angelides, Citation2012).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Christina Hajisoteriou

Christina Hajisoteriou received her PhD from the University of Cambridge, UK. She was also awarded her MPhil in educational research by the same university. Her research interests relate to intercultural education, migration, globalisation, Europeanisation, identity politics and social cohesion. She has published widely in international peer-reviewed academic journals, handbooks and edited volumes. Her latest book is entitled Intercultural Dialogue in Education: Theoretical Approaches, Political Discourses and Pedagogical Practices.

Panayiotis Maniatis

Panayiotis Maniatis, PhD, is teaching intercultural education at the University of Athens, Greece. He is also conducting many research programmes in the field of intercultural education and teaching. His research interests include intercultural education, social exclusion and education, intercultural communication and teacher education.

Panayiotis Angelides

Panayiotis Angelides is professor and the dean of the school of education at the University of Nicosia, Cyprus. Previously he served as an elementary school teacher. His research interests are focused on finding links between inclusive education, teacher development and school improvement. A particular feature of this research is to develop collaborative approaches that have a direct and immediate impact on teachers’ practice. His latest book is entitled Pedagogies of Inclusion.

References

- Adey, P. (2004). The professional development of teachers: Practice and theory. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Ainscow, M. (1999). Understanding the development of inclusive schools. London: Falmer. Press.

- Ainscow, M., Booth, T., & Dyson, A. (2006). Improving schools, developing inclusion. Oxon: Routledge.

- Alexandrou, A., & Swaffield, S. (2016). Teacher leadership and professional development. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Alton-Lee, A. (2003). Quality teaching for diverse students in schooling: Best evidence synthesis. Wellington, NZ: New Zealand Ministry of Education. Available at www.minedu.govt.nz/goto/bestevidencesynthesis

- Altrichter, H., Somekh, B., & Posch, P. (2001). Teachers investigate their work: an introduction to methods of action research. Trans. M. Deliyianni. Athens: Metaixmio. In Greek.

- Angelides, P., Georgiou, R., & Kyriakou, K. (2008). The implementation of a collaborative action research programme for developing inclusive practices. Educational Action Research, 16(4), 557–568. doi:10.1080/09650790802445742

- Arasaratnam, L. A., & Doerfel, M. L. (2005). Intercultural communication competence: Identifying key components from multicultural perspectives. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29(2), 137–163. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2004.04.001

- Bhabha, H. K. (1995). Signs taken for wonders. In B. Ashcroft, G. Griffins, & H. Tiffin (Eds.), The Identity. London: Sage Publications.

- Bikos, K. (2004). Interaction and social relationships in the school classroom. Athens: Ellinika Grammata. In Greek

- Blandford, S. (2014). Leading through partnership: Enhancing the teach first leadership programme. Teacher Development, 18(1), 1–14. doi:10.1080/13664530.2013.863801

- Brah, A. (1996). Cartographies of Diaspora. Contesting Identities. London: Routledge.

- Cardwell, M. (1996). Dictionary of Psychology. Chicago IL: Fitzroy Dearborn.

- Conklin, H. G. (2008). Modeling compassion in critical, justice-oriented teacher education. Harvard Educational Review, 78(4), 652–706. doi:10.17763/haer.78.4.j80j17683q870564

- Creswell, J.W. (2002). Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed method approaches. London: Sage Publications.

- Day, C. (1999). Developing Teachers: The Challenges of Lifelong Learning. London, New York: The Falmer Press.

- Deardorff, D. K. (2008). Intercultural competence: A definition, model and implications for education abroad. In V. Savicki (Ed.), Developing Intercultural Competence and Transformation: Theory, Research, and Application in International Education (pp. 32–52). Sterling, VA: Stylus.

- Deardorff, D. K. (2009). Implementing intercultural competence assessment. In D. K. Deardorff (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence (pp. 477–491). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Denzin, N. K, & Lincoln, Y. (2000). Handbook of qualitative research (2nd edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Dooly, M., & Villanueva, M. (2006). Internationalisation as a key dimension to teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 29(2), 223–240. doi:10.1080/02619760600617409

- Faas, D. (2007a). Turkish youth in the European knowledge economy. An exploration of their responses to Europe and the role of social class and school dynamics for their identities. European Societies, 9(4), 573–599. doi:10.1080/14616690701318805

- Faas, D. (2007b). ‘Youth, Europe and the Nation: the Political Knowledge, Interests and Identities of the New Generation of European Youth. Journal of Youth Studies, 10(2), 161–181. doi:10.1080/13676260601120161

- Faas, D., Hajisoteriou, C., & Angelides, P. (2014). Intercultural education in Europe: policies, practices and trends. British Educational Research Journal, 40(2), 300–318. doi:10.1002/berj.3080

- Fiske, S. T. (2010). Social beings: Core motives in Social Psychology (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Fullan, M. (2014). Teacher development and educational change. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Gallavan, N. P., & Webster-Smith, A. (2009). Advancing cultural competence and intercultural consciousness through a cross-cultural simulation with teacher candidates. Journal of Praxis in Multicultural Education, 4(1). doi:10.9741/2161-2978.1006

- Gee, J. P. (2005). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method (2nd ed.). London: Routledge.

- Gewirtz, S., & Cribb, A. (2008). Differing to agree: A reply to Hammersley and Abraham. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 29(5), 559–562. doi:10.1080/01425690802381577

- Hajisoteriou, C. (2013). Duty calls for interculturalism: How do teachers perceive the reform of intercultural education in Cyprus? Teacher Development, 17(1), 107–126. doi:10.1080/13664530.2012.753936

- Hajisoteriou, C., & Angelides, P. (2012). Developing a collaborative inquiry programme to promote intercultural education in a school in Cyprus. Multicultural Learning and Teaching, 7(2), 2161–2412. doi:10.1515/2161-2412.1125

- Hajisoteriou, C., & Angelides, P. (2016). The Globalisation of Intercultural Education. The Politics of Macro-Micro Integration. London: Palgrave-Macmillan.

- Hajisoteriou, C., Karousiou, C., & Angelides, P. (2018). Successful components of school improvement in culturally-diverse schools. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 29(1), 91–112. doi:10.1080/09243453.2017.1385490

- Hammerness, K., Darling-Hammond, L., Bransford, J., Cochran-Smith, M., McDonald, M., & Zeichner, K. (2005). How terachers learn and develop. In L. Darling-Hammond (Ed.), Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do (pp. 358–389). San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons.

- Hargreaves, D. H. (2012). A self-improving school system towards maturity. Nottingham: NCSL.

- Hilton, G., Assunção, M., & Niklasson, L. (2013). Teacher quality, professionalism and professional development: findings from a European project. Teacher Development, 17(4), 431–447. doi:10.1080/13664530.2013.800743

- Hopkins, D., Stringfield, S., Harris, A., Stoll, L., & Mackay, T. (2014). School and system improvement: a narrative state-of-the-art review. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 25(2), 257–281. doi:10.1080/09243453.2014.885452

- Jokikokko, K. (2005). Interculturally trained Finnish teachers’ conceptions of diversity and intercultural competence. Intercultural Education, 16(1), 69–83. doi:10.1080/14636310500061898

- Knobel, M., & Kalman, J. (2016). New literacies and teacher learning: Professional development and the digital turn. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- King, N. (2016). Using interview in qualitative resarch. In: C. Cassell & G. Symon (Eds.). Essential guide to qualitative methods in organisational research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Leclercq, J. M. (2002). The Lessons of Thirty Years of European Co-Operation for Intercultural Education. Strasbourg: Steering Committee for Education.

- Leeman, Y., & Ledoux, G. (2003). Preparing teachers for intercultural education. Teaching Education, 14(3), 279–291. doi:10.1080/1047621032000135186

- Magos, C. (2007). The contribution of action-research to training teachers in intercultural education: A research in the field of Greek minority education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23, 1102–1112. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2006.09.001

- Maisonneuve, J. (2001). Introduction to Psychosociology. Trans. N. Christakis. Athens: Typothito. In Greek.

- Murillo, F. J. (2007). School Effectiveness Research in Latin America. In T. Townsend (Ed.), International Handbook of School Effectiveness and Improvement (pp. 75–92). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

- Ogay, T., & Edelmann, D. (2016). ‘Taking culture seriously’: implications for intercultural education and training. European Journal of Teacher Education, 39(3), 388–400. doi:10.1080/02619768.2016.1157160

- Sales, A., Traver, J. A., & Garcia, R. (2011). Action research as a school-based strategy in intercultural professional development for teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 911–919. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2011.03.002

- Schön, D. (1983). The reflective Practitioner: how professionals think in action. CA: Basic books, Inc.

- Solarczyk-Szwec, H. (2009). Significance of critical model of educational work with adults in building intercultural competence. In E. Czerka & M. Mechlińska-Pauli (Eds.), Teaching and Learning in Different Cultures: An Adult Education Perspective. Gdańsk: Gdańsk Higher School of Humanities Press.

- Thoonen, E. E. J., Sleegers, P. J. C., Oort, F. J., & Peetsma, T. T. D. (2012). Building school-wide capacity for improvement: the role of leadership, school organizational conditions, and teacher factors. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 23(4), 441–460. doi:10.1080/09243453.2012.678867

- Thrupp, M., & Willmott, R. (2003). Education Management in Managerialist Times: Beyond the Textual Apologists. Berkshire: Open University Press.

- Timperley, H., Wilson, A., Barrar, H., & Fung, I. (2007). Teacher Professional Learning and Development: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration. Wellington, NZ: New Zealand Ministry of Education.

- Tsiplitaris, A. (2004, March 7). Teachers on the edge of a nervous breakdown. Sunday Eleftherotypia, 48–49. [In Greek]

- Villegas, A. M., & Lucas, T. (2002). Preparing culturally responsive teachers: Rethinking the curriculum. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(1), 20–32. doi:10.1177/0022487102053001003