ABSTRACT

This paper deals with possibilities and difficulties involved in the integration of academic and professional goals in two final thesis models in European teacher education, the thesis model and the portfolio model. The methodology used is a review of relevant research articles. The thesis model was identified in 19 articles and the portfolio model in 41 articles. Five dimensions were found to promote the integration of the two kinds of goals while four hamper this integration. The dimensions identified are similar in the two models. The implications of this result for future teachers are discussed using the concepts of vertical and horizontal discourses. One such implication is that teacher education should use the adaptive function of the final thesis in a more developed way in order to strengthen the fusion of academic and professional orientation in the education.

Introduction

Over the last few decades there has been a significant shift of emphasis in teacher education programs in Europe from professional education towards a more academically informed, university-based education (Ek, Ideland, Jönsson, & Malmberg, Citation2013; Laiho, Citation2010).

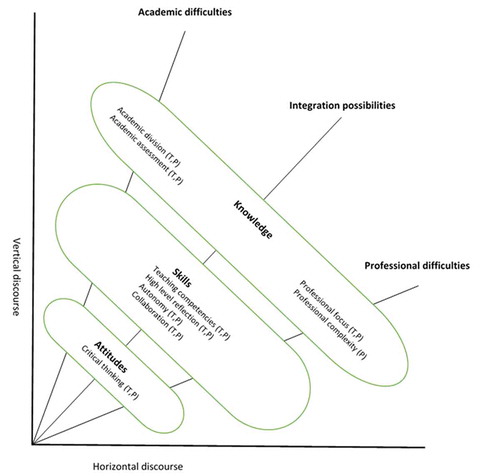

Figure 1. Dimensions promoting or hampering the integration of academic and professional goals of the thesis model (T) and portfolio model (P) in teacher education, and the dimensions’ connection to vertical and horizontal discourse

This change has resulted in some productive developments within teacher education, but also in tensions between the theoretical/academic and the more vocational dimensions of professional education (Harwood, Citation2010). Across many occupational fields there has been a rise in status as a result of the incorporation of professional formation within universities (Cornu, Citation2006), the consequent lengthier education, but also the development of a research-based scientific development for practice, in a process of professionalisation (Freidson, Citation2001). Within teacher education this process is being continuous expanding. The introduction of a final thesis at the bachelor or masters level in teacher education in many European countries, performs this function (Gunneng & Ahlstrand, Citation2002). But, there are tensions in this process that are captured by the often contradictory demands that teacher education courses face between the academic and the vocational elements of professional development. The traditional thesis model, for example, has been found to be an effective way to learn scientific methods (Drennan & Clarke, Citation2009). However, it has also been criticised for having too much focus on a research or theory orientation and not being always relevant to the concerns of professional formation and the pedagogic dimensions of practice (Reis-Jorge, Citation2007). The portfolio model, by contrast, has often been highlighted as being more oriented towards the vocational goals of a professional education (Meeus, Van Looy, & Libotton, Citation2004; Zeichner & Wray, Citation2001).

Even though the academic and vocational dimensions of a professional education are often perceived as distant, the main reason for integrating teacher education into universities has been to establish research and theory-informed practice. This has been the main purpose for the inclusion of the final thesis at the end of teacher education, as part of the goal to form future teachers with an understanding of research practice (Maaranen, Citation2009).

The focused on the possibilities and difficulties related to the integration of theory, practice and research in the thesis and portfolio models in teacher education across Europe. Using the concepts of vertical and horizontal discourses proposed by Bernstein (Citation1999), the study aims to contribute to debates around teacher education as professional formation across Europe, and to discuss its consequences for the future teachers.

The thesis model and the portfolio model

A main problem when studying the final thesis in higher education is that the terminology used in different European countries varies. The terms dissertation, essay, thesis, research project, degree project, report and paper are all used to refer to the final thesis (Luck, Citation1999; Svärd, Citation2014). In this study, the term final thesis is used as a comprehensive concept, which includes bachelor thesis, master thesis and similar project work (Gunneng & Ahlstrand, Citation2002). The reason for this wide definition of final thesis is that teacher students in different countries write a final thesis or similar report at different levels (Svärd, Citation2014). The final thesis is defined as an assessment of the core content of the education, usually carried out at the end of the program (Råde, Citation2014).

In previous research, different models of the final thesis in teacher education have been recognised. Meeus et al. (Citation2004) identified four models in a Belgian context, viz. literature study, portfolio, action research and didactic box. In a Swedish context, Mattsson (Citation2008) found four models, the short thesis model, which is focused on text representation, the portfolio model focused on different media, the case-based model focused on an illustrative example and the practicum model focused on actual performance. According to Mattsson (Citation2008), the thesis model is the most frequently used model in Swedish teacher education while the portfolio model is uncommon and the last two models are only very rarely used. In a European context, Råde (Citation2014) studied three models, viz. the portfolio, the thesis and the action research models, all of which provide opportunities for the integration of academic and professional goals. The current study studies the possibilities and difficulties involved in this kind of theory and practice integration and aims to analyse what different orientation of the final thesis may mean for the teacher students by using the concepts of vertical and horizontal discourses (Bernstein, Citation1999). In order to make this meaning visible, a deliberate choice is made to study the thesis model with a focus on academic goals and the portfolio model with focus on professional goals.

Integrating of academic and professional orientations through the final thesis

Earlier research on university-based professional educations has shown that professional and academic goals can come together in the final thesis in different ways. One of the most frequently used strategies in teacher education is to provide a research-based thesis aimed at getting future teachers to think in a scientific way and use research methods in their professional life (Westbury, Hansén, Kansanen, & Björkvist, Citation2005). Integrating academic and vocational concerns is effectively done through a final thesis with an action research orientation (Maaranen, Citation2009). A more implicit way of integrating these two dimensions is when analytical thinking is applied on the discussion of vocational and professional issues. (Andersson, Day, & McLauglin, Citation2006; Råde, Citation2016). At the same time, the successful integration of the two areas in the final thesis may be hampered by an over-emphasis on highly theoretical questions that may not be relevant for a final thesis in a professional education (Holmberg, Citation2006; Råde, Citation2016). Moreover, the choice of supervisors may be based on their academic competence, rather than their professional competence, which again, could lead to a lack of balance between the two requirements (Carlgren, Citation2009). The final thesis’ connection to academic and professional knowledge seems to be of importance for its function as an integrator.

Vertical and horizontal discourse

The literature distinguishes two fundamentally different kinds of discourse that reflect a dichotomy between academic and practical knowledge (Beach, Citation2011; Bernstein, Citation1999). A horizontal discourse is connected with everyday language and common-sense knowledge related to practical goals (Beach, Citation2005). This knowledge is often oral and context-bound. A vertical discourse is developed in special fields, often within academic disciplines, and forms a hierarchically organised knowledge with special concepts and language (Bernstein, Citation1999). There is an important difference between horizontal and vertical discourses in that the former is more bound to a practical context and often bears little relationship to other contexts. This type of discourse provides a poor basis for developing a reflective professional practice (Bernstein, Citation1999). A vertical discourse on another hand, has a robust system of concepts that can be used by teachers and help them to describe and theorise from empirical situations, which gives a broader understanding of the teaching situation (Beach, Citation2011). This kind of thinking is important for making it possible for teachers to analyse trends and think critically and strategically in order to better serve pupils and children in schools and preschools (Darling-Hammond, Citation2006; Zeichner, Citation2010). Even if the division in these two discourses is relevant in broad sense, all professions contains activities from both discources, and they are overlapping to some extent (Beach & Bagley, Citation2012). Research-activities, in the vertical discourse, contains practical activities, for example interviewing-technique. Teaching, in the horizontal discourse, contains theoretical activities as for example reflection and analytical thinking in connection to planning and evaluation of teaching situations.

The final thesis is often seen as a key component of the more academic goals in higher education and is consequently important for the acquisition of “vertical” knowledge in teacher education and for the students’ future professional practice. However, there is also a risk that the final thesis becomes too theoretical, making it difficult for the students to see how such knowledge is related to the professional work (Gustavsson & Eriksson, Citation2015). Some connection to practical, “horizontal” knowledge is needed in the final thesis, which also has the benefit of motivating the students (Mattsson & Kemmis, Citation2007). On the other hand, there is also a risk that the final thesis becomes too practical and that the benefits of broader analysing and critical skills are disadvantaged (Beach, Citation2011). Studies have also shown that there are tensions between vertical and horizontal goals of the final thesis (Arreman Erixon & Erixon, Citation2015). Ideally, there should be a balance between “vertical” and “horizontal” knowledge in TE, which can be even more effective if “vertical” and “horizontal” knowledge can be integrated to some extent (Råde, Citation2016). The analytical use of the concepts of vertical and horizontal discourse can thus be helpful in acquiring a deeper understanding of the consequences of the different focuses of the two types of discourse in teacher education.

Methodology

This study was conducted in the form of a systematic review of international research articles on the thesis model and the portfolio model used in European teacher education. It follows the guidelines for literature reviews set by the American Psychological Association, which means that it is a critical evaluation of already published material written with the ambition of clarifying a problem (American Psychological Association [APA], Citation2010).

The empirical material consisted of articles in English published in international scientific journals in the past 30 years, as most teacher education was not university based before this period. The articles were found in the database Academic Search Elite using the search terms “teacher education“ in combination with “thesis“/”degree project”/”dissertation” and “portfolio.” Only articles concerning European countries were selected, even if some articles from countries close to Europe was included as for example Turkey. One selection criterion was that the studies, at least to some extent, should be empirical studies partly or wholly focused on final assessment in teacher education. The articles selected were mainly about pre-service preschool teacher and primary school teacher education. As it was difficult to find relevant articles about the thesis model in this way, a “snowball” method based on reference lists in recent articles was employed as a complement to the search.

In total, 60 relevant articles from 14 European countries were obtained from 27 peer-reviewed scientific journals published between 1999 and 2017. The thesis model was identified in 19 articles and the portfolio model in 41. All articles were to some extent empirical and 48% used a mix of research methods, 22% used documents/artefacts, 13% were case-studies, 9% used solely interviews and 7% used solely questionnaires/surveys. The level of the final thesis in the articles were in 25% clearly on master level, in 12% clearly on bachelor level, and in the remaining 63% were the level not possible to identify. The examination of the articles was performed using a qualitative content analysis (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2009). For each model, the research presented in the articles and its connection to the two types of discourse were scrutinised with a view to identifying the promoting or hindering dimensions of the integration of the two kinds of professional formations. The promoting dimensions were found inductively in the articles if the text clearly connected academic goals with professional goals of the final thesis. The hindering dimensions were found in a similar way when problematic and hindering dimensions of the final thesis occurred in the articles and if these dimensions were mainly connected with one of the discourses. The findings of this review were also visually presented in a figure where the different dimensions of the final thesis are categorised under “knowledge”, “skills” or “attitudes”, based on figures used in earlier studies by Boyd (Citation2014), Boyd and Bloxham (Citation2014) and Råde (Citation2016). In the following text the findings is presented under one heading for each model and one for the two models relationship to the vertical and horizontal discourses and is completed with a heading with a summary. To illustrate the result, and some of the variations in the categories, each category found is described and supported by two examples from the studies.

The thesis model

The thesis model was identified in 19 articles in which five dimensions were found as promoting integration between the academic and the professional goals of teacher education ().

Table 1. Dimensions, found in articles, promoting the integration of professional and academic goals of the thesis model in teacher education.

The first dimension promoting integration in the thesis model is Teaching competency, as students can acquire skills useful for their future profession through the final essay. Most articles in this category finds clear teaching skills as in Ion and Iucu (Citation2016) that studied student’s perceptions of their thesis work and found that the thesis helped to enhance the quality of the students’ professional activity and their innovation of teaching strategies. A few studies in this category lifts indirect teaching skills, as for example that skill from the thesis can be transferred to teaching in a general way (Maaranen & Kroksfors, 2008). The second promoting dimension is High-level reflection, as the thesis provides students with opportunities to reflect on practice at different levels. Gadsby and Cronin (Citation2012) studied reflective journals and found that students, through repeated reflections, reached a more advanced level of reflection appropriate for both master-level studies and professional use. The reflection is sometimes connected to several levels as the results from the thesis has benefits for the teacher, the pupils, parents the working society as well as wider society (Maaranen, Citation2010). Critical thinking is a third promoting dimension, and is understood as the students having a critical attitude and more analytical way of thinking. Erixon Arreman and Erixon (Citation2017) analysed published theses and found that most of them had some form of critical perspective. In some studies the critical thinking is described in other words as a more nuanced considerations of concrete incidents (Lund Nielsen, Citation2015). A fourth promoting dimension is Collaboration, as the work with the thesis involves communication with a supervisor, other teacher students, teachers, and students. Here, Maaranen (Citation2009) found that students’ MA thesis work provided them with interaction skills. The collaboration is also described that the students can learn by reading published final thesis of other students (Meeus et al., Citation2004). The fifth promoting dimension is Autonomy, as the thesis model also entails training for students to act independently in different ways. Here, Wyatt (Citation2011) found that thesis work improved students’ self-awareness, self-efficacy and autonomy. In Maaranen and Krokfors (Citation2007) the students after writing the thesis experienced a personal growth, and that a lack of faith was overcomed.

In the articles on the thesis model, three dimensions emerge that make the integration of academic and professional goals more difficult. (). Two of these relate to academic, and one to professional goals.

Table 2. Dimensions, found in articles, hindering the integration of professional and academic goals of the thesis model in teacher education.

The first academic dimension hampering integration in the thesis model is Academic division, as supervisors from different departments and faculties often have quite different views on the thesis, which may interfere with the professional orientation of the thesis. Erixon Arreman and Erixon (Citation2015) found varying perceptions of degree projects among supervisors related to the fact that different disciplinary fields pose multiple and often contradictory requirements for the thesis. Also at same department students experienced an inconsistent approach from supervisors as they had different scientific backgrounds (Sozbilir, Citation2007). Similarly, Academic assessment-issues underpin different conceptions of what are valid and scientific ways of assessing a thesis, and these may interfere with its professional orientation. Gadsby and Cronin (Citation2012) highlighted problems connected with assessing reflective writing, especially ethical considerations, and the selection of excerpts from private reflective text must be decided by students. This means that the assessment can be limited as not the all the reflective text can be assessed as we must not reveal personal issues of the students that might be included in the text. A more indirect hampering effect of academic assessment is the new writing requirements in the professional field, which the thesis is a part of, causes tensions between different professional groups and also between teachers with older and newer education (Erixon & Erixon Arreman, Citation2017)

There are also dimensions of a professional nature that may inhibit integration in the thesis model, captured under the category of Professional focus, as a narrow and contextual perspective may interfere with a broader and analytical perspective. Gadsby and Cronin (Citation2012) found that students’ thesis writings were often descriptive, and Erixon Arreman and Erixon (Citation2017) showed that many students simply adopted the perspective of the teachers studied in their theses, both resulting in uncritical and unreflective pieces of work.

The portfolio model

The portfolio model was identified in 41 articles, where five dimensions of integration of academic and professional goals of teacher education were found ().

Table 3. Dimensions, found in articles, promoting the integration of professional and academic goals of the portfolio model in teacher education.

The first dimension promoting integration in the portfolio model is High-level reflection, meaning that the reflection is based on teaching situations and is relevant in other situations or in an even wider perspective. This makes it easier to analyse and understand the teaching practice. A study by Toom, Husu, and Patrikainen (Citation2015) found that students could reflect beyond solely practical teaching issues, highlight multiple concerns about practice and integrate insights, which are important for their future professional work. Stenberg, Rajala, and Hilpoo (Citation2016) found that students in thematic practicum portfolios used more theory in their reflections, and that the reflection was more robust than in traditional practicum. The second promoting dimension is Teaching competency, as this dimension can be included and assessed in the portfolio in a systematic way. Here, Struyven et al. (Citation2014) found that teacher trainers and mentors considered the portfolio a useful instrument in the assessment of teaching competencies. Van Tartwijk, Van Rijswijk, Tuithof, and Driessen (Citation2008) shows that an analogy between portfolio and professional methods, as for example application letters, helped students to understand and appreciate the portfolio model. The third promoting dimension is Critical thinking, as this dimension is fundamental both in academia and in the teaching professions. Turner and Simon (Citation2013) found that the portfolio is a mediating object that enables students to write critically about their professional learning in master-level teacher education. In Layne and Lipponen (Citation2016) an even more extensive critical thinking appeared where the portfolio gave students the possibility to recognised power, hierarchy, injustice and to promote changes. The fourth promoting dimension is Autonomy, as independent thinking and acting are important both in the academic world and in the profession. A study by Koutsoupidou (Citation2010) concluded that the portfolio is useful for student teachers’ self-assessment. In Lambe, McNair, and Smith (Citation2013) the students reported a sense of pride and ownership when presenting their portfolios. The fifth and last promoting dimension is Collaboration, as the portfolio develops students’ contact with other people, which is both an academic and a professional competence. Here, a study by Hauge (Citation2006) showed that the portfolio stimulated contact and dialogue between students on the program. In Tur and Urbina (Citation2016) the openness of the portfolio had a positively effect on the collaboration among peer students.

In the articles on the portfolio model, four dimensions emerge that make integration difficult (). Two of these dimensions are related to academic, and two to professional goals.

Table 4. Dimensions, found in articles, hampering the integration of professional and academic goals of the portfolio model in teacher education.

The first academic dimension hampering integration in the portfolio model is Academic assessment, as the demands regarding validity and reliability in the assessment of the portfolio can be problematic. Chetcuti (Citation2007) found tensions between formative and summative assessment in the portfolio model. Tummons (Citation2010) proposes that the validity and reliability in the assessments of portfolios is contestable as it mask the complexity and contradiction that are involved in the creation of them. The second academic dimension hampering integration is Academic division, as teacher educators’ different views can interfere with the implementation and use of the portfolio. Granberg (Citation2010) highlights the importance of the social construction of the e-portfolios across TE faculties for making the final essay an effective instrument, rather than just an implementation. In Dysthe and Engelsen (Citation2011) they found systematic differences between educational departments regarding the inclusion of reflective texts in portfolios.

The first professional dimension hampering integration in the portfolio model is Professional focus, as it interferes with a wider academic focus that makes it possible to analyse phenomena using theoretical concepts. Mansvelder-Longayroux, Beijard, and Verloop (Citation2007) identified a trend whereby students using the portfolio model tend to focus on their own practice and the improvement of it, rather than on acquiring an understanding of teaching situations. Körköö, Kyrö-Ämmälä, and Turunen (Citation2016) found that students´ reflections gradually broadened throughout the teacher education but remained primarily descriptive. The second hampering professional dimension is Professional complexity, as the professional practice and teaching competency are affected by many factors, are difficult to study, and analyse in a systematic way. Admiraal, Hoeksma, van der Kamp, and van Duin (Citation2011) showed that while some portfolio models have problems with the assessment of this dimension, video portfolios could facilitate a reliable and valid assessment of teaching competencies. Another study shows that written reports do not justice the complex nature of teaching as they tend to lead to evidence in which teacher competencies are disconnected and removed from the actual teaching practice (Admiraal & Berry, Citation2016)

The thesis and portfolio models’ relationship to vertical and horizontal discourses

The findings are visualised in , which shows the dimensions’ relationships to the two types of discourse. There are many similarities between the potential of the two models to integrate academic and professional goals in teacher education. The difficulties involved in this integration are also more or less the same in the two models, even though the dimension of professional complexity is unique to the portfolio model.

Interestingly, the current review of research articles shows that both models of final thesis offer the capacity to integrate teaching competency, a dimension that belongs to horizontal discourse around professional formation. This can be a good argument to motivate students to work with the final thesis which can be quite demanding for many students. However, other professional dimensions as professional focus and professional complexity are also causing difficulty for the integration. However, it is likely that this integration is also involved in causing the professional difficulties noticed in this study. The more restrictive dimensions of professional focus and professional complexity can also be seen as examples of the problem of too much focus on horizontal discourse within teacher education (Beach, Citation2011; Bernstein, Citation1999). If the final thesis has a narrow focus on unique situations, or if a situation is very complex, this of course makes it difficult to create knowledge transferable to other situations. On the other hand, it can be argued that also in research it is possible to study unique and more limited situations as for example case-studies (Yin, Citation2014). It can also be argued that complex situations can be studied in an academic way, and this occurs in social science studies about human behaviour and especially in research about education (Davis & Sumara, Citation2010). Therefore, these problematic professional dimensions may not be so severe, but rather indications that teaching is about human activities, that is often unique and quite complex. In addition, Bernstein (Citation1999) has a relevant point here, which favours the vertical discourse, namely that theoretical concepts and hierarchical knowledge are important. It is of great value also for teachers to learn from unique situations in relation to other situations in a systematic way. Moreover, in this connection, the final thesis can be a useful tool for this ambition as a kind of “boundary object” between theories and practice (Bowker & Star, Citation1999). In favour of a balance between theory and practice in the final thesis, it can be argued that both research and professional work initially often require a kind of description of situations and that in both worlds, an understanding of the situation depends on some form of theoretical analysis, which highlights this very important dimension.

An even more interesting finding in this study concerns high-level reflection as an integrative dimension in both models. As per the reasoning above, it is important to distinguish between high-level reflection and low-level reflection, which only involves a unique situation. The study also shows that the interpretation of the concept of high-level reflection differs somewhat in the various studies, ranging from setting a situation in relation to future situations to setting a situation in relation to a broader context, for example a curriculum or society. Especially when the reflection is done in a more theoretical way, this is an example of the benefit of the vertical discourse, as it provides opportunities to understand a situation through an analysis of some kind. It might also be suggested here that there should be a balance between these analyses or reflections. The reflective focus of a practitioner is naturally on the situation today, tomorrow or the current semester, while a researcher’s analysis often has a wider scope. Even if this is obvious, it is of course important that teachers widen their reflections at times and question what is going on in their classrooms. Researchers, too, should sometimes narrow their reflection/analyses and conduct more delimited studies, for example classroom studies, that might have some important implications for the day-to-day work of teachers.

High-level reflection can also be called a generic skill, i.e. a skill that applies across a variety of situations (Barrie, Citation2007; Jääskelä, Nykänen, & Tynjälä, Citation2018). In addition, three other promoting skills in this study, critical thinking, autonomy and collaboration, can be seen as being generic skills, which explains why they are conducive to integration. Critical thinking, in particular, is an important dimension in the vertical discourse, which makes it possible to think in new ways about professional situations. However, the generic skills have also been criticised, for example by Jäskälää et al. (Citation2018) who argued that these skills, too, are largely bound to their context and field. This is a point of view to bear in mind, as many articles in this study are based on teacher educators’ and students’ perceptions of the future value of the final thesis. We do not know whether this transfer of generic skills will actually happen in real life. However, this study includes some studies of students pursuing their teacher education while working which show a more explicit transfer of skills (Maaranen, Citation2009).

What this study has also shown is that the connection to vertical discourse poses some severe difficulties. Both final essay models display two of these difficulties, which involve academic division and assessment providing points of tension for the fusion between of vertical and horizontal discourses. This is a dilemma in teacher education as a whole, as it sometimes has a fragmented structure made up of different departments with different disciplinary traditions (Carlgren, Citation2009; Ek et al., Citation2013). In one way, this is a problem, as it may be confusing for students to encounter various distinct writing traditions, theories, and research methodologies during their studies. However, this may also provide the students with an understanding of different approaches to subject knowledge as well as pedagogic approaches, which may contribute, to a better understanding of how schools and preschools can be studied. In general, a deeper focus on one single style of writing and theory tradition would be more helpful for the students in their writing of the final thesis. This may be an important point of view to consider in development efforts in teacher education towards some form of consistent and more unified theoretical focus throughout the different parts of the program.

The perspective of academic assessment is also of a serious nature and is to some extent connected with the problem of academic division. It might seem problematic to assess the content of a final thesis that has an orientation that is more professional, such as reflective texts, as this requires assessment that is more formative. However, a pragmatic understanding of the predominance of the portfolio model in teacher education indicates that this kind of assessment is possible. This difficulty may also explain why this model is not used in some countries (Mattsson, Citation2008). In addition, different academic traditions may view this kind of assessment in different ways, and some traditions may find it more complicated to perform than others did. One example of this is the critique about the portfolio that has occurred is that it is time-consuming (Zellers & Mudrey, Citation2007), and another problem is that students can have difficulties to write down their reflections. The problem might also be connected with the hampering professional dimension of professional complexity, as this diversity will require different kinds of assessment that can also capture for example, oral communication, body language. There are also examples of how teaching competencies can be assessed, such as video narratives, and one way forward might be for teacher education departments to be a bit more innovative or at least to develop relevant assessment criteria for the final thesis (Admiraal & Berry, Citation2016).

Summary

As in all cases of extensive reviews, it has not been possible to be wholly inclusive of all available articles in the field. The search for articles on the thesis model was to some degree problematic as the number of articles dealing with the thesis model is about half of those focused on the portfolio model. As such, the relatively limited basis for analysis of the former model might have affected the results of the review. In addition, it was not in all cases entirely clear which model some of the articles actually dealt with. They were nevertheless included in the study, as they were dealing with a model that corresponded more closely to one or other of the two models.

To sum up, some implications of this study can be emphasised. The current review suggests that the research in this field indicates that it is possible to integrate academic and professional dimensions in teacher education, both in the thesis and in the portfolio model. The reason for this might be the overlapping of competencies belonging to the vertical and horizontal discourse (Beach & Bagley, Citation2012). A suggestion might be that the portfolio could be used during the education as a complement to our basis for the thesis model. This can be argued based on the study’s findings regarding the positive integrational dimensions of the portfolio model as regards teaching competency and the development of high-level reflection. While such a combination of the two models seems to be used in many countries, for example in Finland (Maaranen, Citation2009), the portfolio model is only rarely used in higher education in other countries, for example in Sweden (Mattsson, Citation2008). On the other hand, this study also shows that the thesis model provides more or less the same integrational possibilities, which speaks in favour of that model. The crucial point, however, is probably how the models are used to support the integrative dimensions, as this study reveals that the models can be focused in quite different ways. It is an advantage if a final thesis has an established structure. The final thesis also has the capacity of adaptation, like a kind of “chameleon” (Dysthe & Engelsen, Citation2011; Pilcher, Citation2011). Thus, one implication of this study is that teacher educators should open their minds and develop this adaptability, whatever final thesis model is used, and to make the final thesis a functional boundary object for the integration of academic and professional goals in the education (Bowker & Star, Citation1999). Another useful metaphor is that the final thesis could be seen as a “flying fish” that can integrate two contexts, the future teachers’ capacity to “swim” in the water of the teaching world and their the capacity to “fly” with a bird´s-eye-view of the academic world (Råde, Citation2016).

Another implication is that the integrational dimensions of the final thesis should be highlighted more in the course of teacher education programmes in order to make the students aware of the benefits of the final thesis for their future professional practice. In addition, such an awareness among teacher educators will give them the possibility to highlight and consolidate the integration of professional and academic goals in the educational process by pointing out to their students the benefits of acquiring competencies connected to horizontal discourse through their final thesis work, such as teaching and collaborative competencies. At the same time the connection to vertical discourse in the students’ work on the final thesis with high-level reflection, critical thinking and an autonomous attitude can help the future teachers to analyse why schools and preschools function in a certain way and to challenge any practices or policies found to be unsatisfactory. In line with the teaching of the core values of a democracy in schools, this may also inspire pupils and children to think for themselves and to dare to question issues in schools/preschools and society as a whole.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Anders Råde

Anders Råde has a Ph. D. in education, and is senior lecturer at teacher education at Umeå University, Sweden. His research interest focuses the relationship between theory and practice in academic professional education.

References

- Admiraal, W., & Berry, A. (2016). Video narratives to access student teachers´ competence as teachers. Teachers and Teaching, Theory and Practice, 22(1), 21–34.

- Admiraal, W., Hoeksma, M., van der Kamp, M.-T., & van Duin, G. (2011). Assessment of teacher competence using video portfolios: Reliability, construct validity, and consequential validity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(6), 1019–1028.

- American Psychological Association (APA). (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Andersson, C., Day, K., & McLauglin, P. (2006). Mastering the dissertation: Lectures´ representations of the purposes and processes of master´s level dissertations supervision. Studies in Higher Education, 31(2), 149–168.

- Arreman Erixon, I., & Erixon, P.-O. (2015). The degree project in Swedish early childhood education and care: What is at stake? Education Inquiry, 6(3), 309–332.

- Ayan, D., & Seferoglu, G. (2011). Using electronic portfolios to promote reflective thinking in language teacher education. Educational Studies, 37(5), 513–521.

- Bannink, A. (2009). How to capture growth? Video narratives as an instrument in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25, 244–250.

- Barrie, S. C. (2007). A conceptual framework for the teaching and learning of generic graduate attributes. Studies in Higher Education, 32, 439–458.

- Beach, D. (2005). The problem of how learning should be socially organized. Reflective Practice, 6(4), 473–489.

- Beach, D. (2011). Education science in Sweden: Promoting research for teacher education or weakening its scientific foundations? Education Inquiry, 2(2), 207–220.

- Beach, D., & Bagley, C. (2012). The weakening role of education studies and the re-traditionalisation of Swedish teacher education. Oxford Review of Education, 38(3), 287–303.

- Bernstein, B. (1999). Vertical and horizontal discourse: An essay. British Journal of Sociology, 20(2), 157–173.

- Boulton, H. (2014). ePortfolios beyond pre-service teacher education: A new dawn? European Journal of Teacher Education, 37(3), 374–389.

- Bowker, G., & Star, S. L. (1999). Sorting things out: Classifications and its consequences. London: MIT Press.

- Boyd, P. (2014). Using ‘modelling’ to improve the coherence of initial teacher education. In P. Boyd, A. Szplit, & Z. Brog (Eds.), Teacher educators and teachers as learners: International perspectives (pp. 51–73). Krakow: Libron.

- Boyd, P., & Bloxman, S. (2014). A situative metaphor for teacher learning: The case of university tutors learning to grade student coursework. British Educational Research Journal, 40(2), 337–352.

- Brinkman, F. G., & Van Rens, E. M. M. (1999). Student teachers´ research skills as experienced in their educational training. European Journal of Teacher Education, 22(1), 115–125.

- Carlgren, I. (2009). Lärarna i kunskapssamhället: Flexibla kunskapsarbetare eller professionella yrkesutövare [The teachers in the knowledge society: Flexible knowledge workers or professional professionals]. Forskning om undervisning och lärande, 3, 9–24.

- Chadha, D. (2015). Evaluating the impact of graduate certificate in academic practice (GCAP) programme. International Journal for Academic Development, 20(1), 46–57.

- Chetcuti, D. (2007). The use of portfolios as a reflective learning tool in initial teacher education: A Maltese case study. Reflective Practice, 8(1), 137–149.

- Chetcuti, D., Buhagiar, M. A., & Cardona, A. (2011). The professional development portfolio: Learning through reflection in the first year of teaching. Reflective Practice, 12(1), 61–72.

- Cornu, B. (2006). Teacher training: The context of the knowledge society and lifelong learning the European dimension and the main trends in France. In P. Zgaga (Ed.), Modernization of study programmes in teachers´ education in an international context (pp. 26–36). Ljubljana: European Social Fund.

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Powerful teacher education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Davis, B., & Sumara, D. (2010). ´If things were simple…`: Complexity in education. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16, 856–860.

- Drennan, J., & Clarke, M. (2009). Coursework master´s programmes: Student’s experience of research supervision. Studies in Higher Education, 35(5), 483–500.

- Dysthe, O., & Engelsen, K. S. (2011). Portfolio practices in higher education in Norway in an international perspective: Macro-, meso-, and micro-level influences. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 36(1), 63–79.

- Dysthe, O., Engelsen, K. S., & Lima, I. (2014). Variations in portfolio assessment in higher education: Discussion of quality issues based on a Norwegian survey across institutions and disciplines. Assess Writing, 12, 129–148.

- Ek, A. –. C., Ideland, M., Jönsson, S., & Malmberg, C. (2013). The tension between marketization and academisation in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 38(9), 1305–1318.

- Erixon Arreman, I., & Erixon, P.-O. (2015). The degree project in Swedish teacher education and care: What is at stake? Education Inquiry, 6(3), 309–332.

- Erixon Arreman, I., & Erixon, P.-O. (2017). Professional and academic discourse: Swedish student teachers´ final degree project in early childhood education and care. Linguistics and Education, 37, 52–62.

- Erixon, P.-O., & Erixon Arreman, I. (2017). Extended writing demands: A tool for ‘academic drift and the professionalisation of early childhood education. Education Inquiry, 8(4), 263–267.

- Escobar Urmeneta, C. (2013). Learning to become a CLIL teacher: Teaching, reflection and professional development. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 16(3), 334–353.

- Frank, M., & Barzilai, A. (2004). Integrating alternative assessment in a project-based learning course for pre-service science technology teachers. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 29(1), 41–61.

- Freidson, E. (2001). Professionalism the third logic: On the practice of knowledge. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Gadsby, H, & Cronin, S. (2012). To What Extent Can Reflective Journaling Help Beginning Teachers Develop Masters Level Writing Skills? Reflective Practice, 13(1), 1-12. doi:10.1080/14623943.2011.616885

- Granberg, C. (2010). E-portfolios in teacher education 2002–2009: The social construction of discourse, design and dissemination. European Journal of Teacher Education, 33(3), 309–322.

- Groom, B., & Maunonen-Eskelinen, I. (2006). The use of portfolios to develop reflective practice in teacher training: A comparative and collaborative approach between two teacher training providers in the UK and Finland. Teaching in Higher Education, 11(3), 291–300.

- Gunneng, H., & Ahlstrand, E. (2002). Quality indicators in final thesis in higher education: A comparative pilot study. Linköping: Linköping University Faculty of Arts and Science.

- Gustavsson, G., & Eriksson, A. (2015). Blivande lärares frågor vid handledning: Gör jag en kvalitativ studie med kvantitativ inslag? [Teacher’s teaching questions: Do I do a qualitative study with quantitative elements?]. Pedagogisk forskning i Sverige, 20(1–2), 79–99.

- Halbach, A. (2016). Empowering teachers, triggering change: A case study of teacher training through action research. Estudios Sobre Educacion, 31, 57–73.

- Harwood, J. (2010). Understanding academic drift: On the institutional dynamics of higher technical and professional education. Minerva, 48, 413–427.

- Hauge, T. E. (2006). Portfolios and ICT as means of professional learning in teacher education. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 32(1), 23–36.

- Helleve, I. (2007). In an ICT-based teacher-education context: Why was our group ´the magic group`? European Journal of Teacher Education, 30(3), 267–284.

- Holmberg, L. (2006). Coach, consultant or mother? Supervisors´ views on quality in supervision of bachelor thesis. Quality in Higher Education, 12(2), 207–216.

- Imhof, M., & Picard, C. (2009). Views on using portfolio in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25, 149–154.

- Ion, G., & Iucu, R. (2016). The impact of postgraduate studies on the teachers´ practice. European Journal of Teacher Education, 39(5), 602–615.

- Jääskelä, P., Nykänen, S., & Tynjälä, P. (2018). Models for the development of generic skills in Finnish higher education. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 42(1), 130–142.

- Kaasila, R., & Lauriala, A. (2012). How do pre-service teachers´ reflective processes differ in relation to different contexts? European Journal of Teacher Education, 35(1), 77–89.

- Körköö, M., Kyrö-Ämmälä, O., & Turunen, T. (2016). Professional development through reflection in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 55, 198–206.

- Koutsoupidou, T. (2010). Self-assessment in generalist preservice kindergarten teachers´ education: Insights on training, ability, environments, and policies. Arts Education Policy Review, 111, 105–111.

- Kvale, S, & Brinkmann, S. (2009). Interviews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Laiho, A. (2010). Academisation of nursing education in the Nordic countries. Higher Education, 60, 641–656.

- Lambe, J., McNair, V., & Smith, R. (2013). Special educational needs, e-learning and the reflective portfolio: Implications for developing and assessing competence in pre-service education. Journal of Education for Teaching, 39(2), 181–196.

- Layne, H., & Lipponen, L. (2016). Student teachers in the contact zone: Developing critical intercultural ´teacherhood´ in kindergarten teacher education. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 14(1), 110–126.

- Luck, M. (1999). Your student research project. Aldershot: Gower.

- Lund Nielsen, B. (2015). Pre-Service Teachers´ Meaning Making When Collaboratively Analysing Video from School Practice for the Bachelor Project at College. European Journal of Teacher Education, 38(3), 341–357.

- Maaranen, K. (2009). Practitioner research as part of professional development in initial teacher education. Teacher Development: an International Journal of Teachers’ Professional Development, 13(3), 219–237.

- Maaranen, K. (2010). Teacher student’s MA thesis: A gateway to analytic thinking about teaching? A case study of Finnish primary school teachers. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 54(5), 487–500.

- Maaranen, K., & Krokfors, L. (2007). Time to think? Primary school teacher students reflecting on their MA thesis research process. Reflective Practice, 8(3), 359–373.

- Maaranen, K., & Krokfors, L. (2008). Researching pupils, schools, and oneself. Teachers as integrators of theory and practice in initial teacher education. Journal of Education for Teaching, 34(3), 207–222.

- Mansvelder-Longayroux, D. D., Beijard, D., & Verloop, N. (2007). The portfolio as a tool for stimulating reflection by student teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23, 47–62.

- Mattsson, M. (2008). Conclusions and challenges. In M. Mattsson, I. Johansson, & B. Sandström (Eds.), Examining praxis: Assessment and knowledge construction in teacher education (pp. 209–227). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Mattsson, M., & Kemmis, S. (2007). Praxis-related research: Serving two masters? Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 15(2), 185–214.

- Meeus, W., Van Looy, L., & Libotton, A. (2004). The bachelor’s thesis in teacher education. European Journal of Teacher Education, 27(3), 299–321.

- Meeus, W., Van Petegem, P., & Meijer, J. (2008). Stimulating independent learning: A quasi-experimental study on portfolio. Educational Studies, 34(5), 469–481.

- Oner, D., & Adanan, E. (2011). Use of web-based portfolios as tools for reflection in pre-service teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 62(5), 477–492.

- Pilcher, N. (2011). The UK postgraduate masters dissertation: An “elusive chameleon”? Teaching in Higher Education, 16(1), 29–40.

- Råde, A. (2014). Final thesis models in European teacher education and their orientation towards the academy and the teaching profession. European Journal of Teacher Education, 37(2), 144–155.

- Råde, A. (2016). Mellan akademi och lärarprofession: Integrering av vetenskapliga och professionella mål för lärarutbildningens examensarbeten [Between the Academy and the Teaching profession: Integration of academic and professional goals in the degree project in Swedish teacher education]. Phd Diss., Umeå, Sweden: Umeå university.

- Reeves, J., & I’Anson, J. (2014). Rhetoric of professional change: Assembling the means to act differently? Oxford Review of Education, 40(5), 649–666.

- Reis-Jorge, J. (2007). Teachers´ conceptions of teacher-research and self-perceptions as inquiring practitioner: A longitudal case study. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(4), 402–417.

- Rifá-Valls, M. (2011). Experimenting with visual storytelling in students’ portfolios: Narratives of visual pedagogy for pre-service teacher education. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 30(2), 293–306.

- Smith, K., & Tillema, H. (2007). Use of criteria in assessing teaching portfolios: Judgemental practices in summative evaluation. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 51(1), 103–117.

- Sozbilir, M. (2007). First steps in educational research: The views of Turkish chemistry and biology student teachers. European Journal of Teacher Education, 30(1), 41–61.

- Spendlove, D., & Hopper, M. (2006). Using ‘Electronic portfolios’ to challenge current orthodoxies in the presentation of an initial teacher training design and technology activity. International Journal of Technology and Design Education, 16, 177–191.

- Stenberg, K., Rajala, A., & Hilpoo, J. (2016). Fostering theory-practice reflection in teaching practicum. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 44(5), 470–485.

- Struyven, K., Blieck, Y., & De Roeck, V. (2014). The electronic portfolio as a tool to develop and assess pre-service student teaching competences: Challenges for quality. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 43, 40–54.

- Struyven, K., Dochy, F., & Janssens, S. (2008). The effects of hands-on experience on students´ preferences for assessment methods. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(1), 69–88.

- Svärd, O. (2014). Examensarbetet: En kvalitetsindikator inom högre utbildning? Exemplet högskoleingenjörsutbildningen [Degree Project: A Quality Indicator in Higher Education? The example of college engineer education]. Phd diss. Uppsala: Uppsala universitet.

- Tanner, R., Longayroux, D., & Verloop, N. (2000). Piloting portfolios: Using portfolios in pre-service teacher education. ELT Journal, 54(1), 20–30.

- Toom, A., Husu, J., & Patrikainen, S. (2015). Student teachers´ patterns of reflection in the context of teaching practice. European Journal of Teacher Education, 38(3), 320–340.

- Tummons, J. (2010). The assessment of lesson plans in teacher education: A case study in assessment validity and reliability. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(7), 847–857.

- Tur, G., & Urbina, S. (2016). Collaboration in eportfolios with web 2.0 tools in initial teacher training. Culture and Education, 28(3), 601–632.

- Turner, K., & Simon, S. (2013). In what ways does studying at M-level contribute to teachers´ professional learning? Research set in an English university. Professional Development in Education, 39(1), 6–22.

- Van Tartwijk, J., Van Rijswijk, M., Tuithof, H., & Driessen, E. W. (2008). Using an analogy in the introduction of a portfolio. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24, 927–938.

- Westbury, I., Hansén, S.-E., Kansanen, P., & Björkvist, O. (2005). Teacher education for research-based practice in expanded roles: Finland’s experience. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 49(5), 475–485.

- Wyatt, M. (2011). Teachers researching their own practice. ELT Journal, 65(4), 417–425.

- Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5 ed.). London: Sage.

- Zeichner, K. (2010). Competition, economic rationalization, increased surveillance, and attacks on diversity: Neo-liberalism and the transformation of teacher education in the U.S. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26, 1544–1552.

- Zeichner, K., & Wray, S. (2001). The teaching portfolio in US teacher education programmes: What we know and what we need to know. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(5), 613–621.

- Zellers, M., & Mudrey, R. (2007). “Electronic portfolios and metacognition: A phenomenological examination of the implementation of e-portfolios from the instructors´ perspective. International Journal of Instructional Media, 34, 419–430.