ABSTRACT

In this study, we analyse 126 secondary pupils’ responses to national test questions designed to make them think and care about the history of national minorities in Sweden. Using a mixed method approach we find that historical thinking and empathy as caring are tightly interlinked in the responses. In particular, the cognitive act of corroborating historical sources about the treatment of minorities is linked to historical empathy as caring – while sourcing seems like a separate process. We also find that pupils struggle to link the past to the present and the future more than they do with sourcing and corroboration. Engaging with the past of discrimination of minorities makes pupils take critical positions beyond established dimensions of historical thinking. Our findings highlight how we need to better understand how to scaffold pupils’ practical knowledge, skills and attitudes in ideologically and emotionally charged issues.

Introduction

The neglect of minorities in history education has been identified as a problem since the Second World War. To safeguard democracy and unity in diversity the Council Europe recommended that history teachers focus more on stimulating critical mindsets in combination with a positive awareness of minorities living in Europe (Bruley & Dance, Citation1960; Council of Europe, Citation1995, Citation2001). Pupils’ critical mindsets should help them identify propaganda and totalitarian tendencies. History teaching should no longer promote nationalism and militarism; instead it should promote understanding between ethnic groups and across borders (Nygren, Citation2016a). History lessons were to counter prejudices between people, by concentrating on the peaceful social and cultural history of Europe with links between people of the past and present (Bruley & Dance, Citation1960). Today, history education in Europe should promote pupils to learn “a common historical and cultural heritage, enriched through diversity, even with its conflictual and sometimes dramatic aspects” (Council of Europe, Citation2001).

Even if history education in Sweden has developed in line with recommendations from UNESCO and the Council of Europe since the 1950s (Nygren, Citation2016a), the history of national minorities in Sweden did not become a compulsory aspect of the national history education syllabus until 2011, when the history of the Romani and Sami people was introduced (Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2011). This new content was implemented after Swedish scholars of history education had stressed the need for a more inclusive, diverse and multicultural history syllabus (HLFÅ, Citation2007; Lozic, Citation2010; Nordgren, Citation2006). Following this reform, history education in Sweden was intended to promote the understanding of national minorities, historical thinking and historical consciousness (Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2011). However, implementing values and skills in history education is not a simple top-down process. What is stated in guidelines does not automatically trickle down and reach the minds of the pupils (Nygren, Citation2016a). In this case, it is a complicated matter of implementing historical empathy and thinking when dealing with the neglected history of minorities.

This study intends to examine the interplay of historical thinking and empathy as caring in pupils’ writing about the history of the Swedish minority the Romani people in the national test in history for year 9. We analyse tests designed to assess pupils’ abilities to think historically and understand the situation of minorities in the past. We look at the national tests from 2014 and study how pupils (1) critically scrutinise sources from the history of the Romani people; (2) corroborate sources describing the situation of Jews, Romani and Sami people in the seventeenth-century Sweden, and (3) reflect upon the past and present of the Romani people. In light of theories of historical thinking and empathy as caring, we analyse what perspectives are set in the foreground and in the background and to what extent it is possible for pupils to think and care about the history of the Romani people.

Theoretical framework

The complexity of implementing critical thinking and understanding of minorities

International guidelines and the national Swedish curriculum state that schools should foster citizenry and universal moral values as well as critical thinking skills. However, the process of implementation in schools is far more complex than simply a top-down process (Nygren, Citation2016a). Using John Goodlad’s curriculum theory, implementation may be seen as a transaction, interpretations and resistance to change among the agents bound to enact the demands of the syllabus (Ball, Maguire, Braun, Perryman, & Hoskins, Citation2012; Goodlad, Citation1979). Samuelsson and Wendell (Citation2016) have noted how national tests in history can be understood as a part of a bureaucratic national accountability system in which the classroom practice and the national tests constitute the last link in a “delivery chain” (Ball, Maguire, Braun, Perryman & Hoskins, Citation2012 p. 513; Samuelsson & Wendell, Citation2016).

Hence, by writing about the Romani people’s situation in the past, pupils can “perform subject-analytical tasks in a context of [national] accountability” (Samuelsson & Wendell, Citation2016, p. 480) and how this may relate to the interplay of thinking and caring about people in the past. The current Swedish national compulsory curriculum states that a “historical perspective enables pupils to develop an understanding of the present, and a preparedness for the future, and develop their ability to think in dynamic terms” (Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2011, p. 11). What this means from the perspective of pupils; how they think and care about the history of national minorities, needs to be better understood.

Historical thinking and empathy as caring

Since the 1950s, thinking and caring about people has been central in guidelines. Scholars have debated the extent to which history education can, or should, foster citizens or just focus on educating pupils to read like historians. In the theory of history education, we find two approaches towards history as a school subject: historical thinking and historical empathy as caring. Historical thinking is an approach in which the pupil takes the role of the professional historian; embracing subject disciplinary thinking where the ability to critically scrutinise the source, corroborate, use evidence and contextualise historical information is central (Wineburg, Citation1991, Citation2001). British scholars who advocate this perspective emphasise the importance of history education in pupils’ development of cognitive skills, rather than fostering democratic and moral values (Lee & Ashby, Citation2001; Foster, Citation1999). Accordingly, pupils should not judge events and people in the past learn how to pay attention to historical context in order to avoid presentism, and to separate the past from the present and the future (Davis, Yeager, & Foster, Citation2001). This epistemological principle may be regarded as fundamental for the professional historian and thus in the historical thinking approach to history education. As an advocate of historical thinking historian Peter Lee once stated that “[i]f history is taught so that priority is given to shedding light on the present, to pointing up origins, to offering lessons, or to encouraging–let alone inculcating–political or moral attitudes, it ceases to be adequate history, and fails to deliver what it legitimately offers” (Lee, Citation1992, p. 30). Thus, historical thinking is regarded as a cognitive act in this study. This approach to learning about the past has been described as an inquiry into the past where emotional involvement and imagination endangers the historical study, which “[…] depends on a process of disciplined reasoning based upon available evidence” (Foster, Citation2001, p. 170). This disciplinary approach to the historical past may be seen as a contrast to a practical approach to the past where history should have relevance to lived experiences in the present (Nygren & Johnsrud, Citation2018; White, Citation2014).

Advocates for a more practical approach to the past underscore that history education in addition to historical thinking can and should hold moral and emotional dimensions, what may be labelled historical empathy as caring (Barton & Levstik, Citation2004). From this perspective, not only does the past constitute a great source of analytic examples and possibilities for discussions of cause and effect, but may serve as a “training ground for moral response” stressing that “some aspects of morality will vary among groups, others are rooted in the nature of the democracy we envision” (Barton & Levstik, Citation2004, p. 106). This perspective on history education acknowledges the importance of historical thinking but also finds that democratic values and emotions are important parts of schooling. Learning history is described as an intellectual and emotional act (Endacott & Brooks, Citation2018; Levstik & Thornton, Citation2018). Furthermore, the theoretical understanding of historical empathy as caring may be enriched by acknowledging the understanding that the past affects how we perceive our present and what perceptions and expectations we have on our future – i.e. historical consciousness (Jensen, Citation1997; Rüsen, Citation2004; Shemilt, Citation2009). Accordingly, history from this perspective can be seen a matter of emotions and justice aiming to explore and understand historical perspectives: caring, not only about the lives and experiences of the past, but also for the present and future.

Consequently, there is a divide in theory between scholars regarding the purpose of historical studies. Some underline the importance of connecting with the past on cognitive and emotional levels while others emphasise the importance of studying the past as an objective and “disinterested judge” (Novick, Citation1988, p. 2). How this plays out when pupils are prompted to consider the past and present of Romani in Sweden can help us better understand the complexity of pupils’ thinking and caring about the past.

Previous research

Pupils’ thinking, writing and reasoning in history education is studied regularly: often with a focus on pupils’ evaluating historical sources – an act that can be seen fundamental in history as a scholarly discipline (Rüsen, Citation2004). Furthermore, studies have shown that the cognitively challenging act that is reading like a historian – thinking disciplinary like the professional historian – can be learned by practicing skills such as sourcing, contextualisation and corroboration whilst thinking of the past in the classroom (De-La Paz et. al., Citation2014; Nygren, Vikström & Sandberg, Citation2014; Reisman, Citation2012). In addition, studies have explored and examined how subjective and objective elements of historical empathy may be stimulated in the classroom: suggesting that pupils are capable of both thinking and caring (Brooks, Citation2011, Citation2014; Nygren, Citation2016b). In her research, Sarah Brooks has examined how pupils and teachers reason about the past in terms of historical empathy, suggesting perspective recognition and care as well as past-present discussion elements of empathy as caring: giving insight into what she describes as “the complex and nuanced task of inviting pupils to use the past to understand and act for the common good in their current world” (Brooks, Citation2014, p. 89).

Previous research in a Swedish context suggests that the conflicting ideals of historical thinking versus empathy as caring may not be in opposition in practice. In pupil essays about the history of indigenous people’s human rights, Nygren (Citation2016b) finds an intertwined relationship between the thinking and caring. A vast majority of the pupils combined normative moral judgments with the cognitive act of perspective recognition and this suggests that it is in fact possible to balance thinking and empathy (Nygren, Citation2016b). In classrooms Swedish pupils have also been noted to think and care about the human lives they encounter when working with digitised primary sources (parish registers). In this case study pupils managed to think historically but moral and affective reactions were common and not always productive (Nygren, Vikström & Sandberg, Citation2014).

Promoting and assessing historical thinking and democratic values have been noted to hold challenges, in theory and practice in Sweden (Alvén, Citation2017a; Nygren, Citation2016a). Pupils with opinions contrary to the common values of the Swedish school may write “compelling historical narratives with the help of historical thinking skills”: a fact that makes some teachers award a pass, while other teachers consider the moral and political values manifested, and fail the pupil on moral grounds (Alvén, Citation2017b). Thus, pupils may write in line with the value-system of the Swedish school and not be acknowledged for their historical thinking skills if they state the wrong values, and learn to focus more on caring than thinking.

Furthermore, historical thinking may be a challenge to pupils. Especially contextualising sources and evidence is a challenge in practice and in national tests (Foster & Yeager, Citation1999; Kohlmeier, Citation2005; Nygren & Vikström, Citation2013; Reisman, Citation2012; Rosenlund, Citation2016; Samuelsson & Wendell, Citation2016; Stolare, Citation2017). In a Swedish context, Samuelsson and Wendell (Citation2016) found that most pupils in year 6 had a hard time sourcing and contextualising historical information in the national tests. This study finds that most of the pupils were given a passing grade by the assessing teachers although they show limited subject disciplinary knowledge in the assignments: suggesting that teachers “[do] not fully enact the demands of the syllabus (Samuelsson & Wendell, Citation2016). Also, in upper-secondary schooling, Swedish students at more advanced level (History 2 & 3) may struggle with test questions designed to assess historical thinking (Rosenlund, Citation2016). Lack of domain-specific knowledge can make it hard for students to contextualise historical sources, to understand temporal dimensions of the past and critically scrutinise information in relevant ways (Nygren, Haglund, Samuelsson, Af Geijerstam, & Prytz, Citation2018; Rosenlund, Citation2016).

Studies of textbooks and teaching materials have noticed an apparent lack of historical narratives about national minorities. Mattlar (Citation2014, Citation2016)) describes the history of minorities as a silent historiography, suggesting that the Swedish commitment to follow The Framework Convention for the Protection of National MinoritiesFootnote1 may not be fulfilled in classroom practices (Indzic Dujso, Citation2015; Mattlar, Citation2014, Citation2016).

The Swedish history syllabus has a long tradition of following international guidelines, promoting international understanding and a moulding of attitudes (Nygren, Citation2011). In recent years, Sweden has seen what can be described as an epistemological shift in the curriculum. Whereas the previous syllabus stressed interdisciplinary perspectives and the weight of taking pupils’ personal interests into account, the current curriculum focuses more on stimulating disciplinary thinking in subjects (Nygren et al., Citation2018; Wahlström & Sundberg, Citation2015). Ideals of universal values and critical thinking are evident today, but how pupils think and care about the history of national minorities is so far not researched.

Data and methodology

In this paper, we analyse the answers to three questions from the national test in history from 2014. The analysed sub-section was called The Development Line of Intercultural interaction and had a special focus on the Romani peoples’ situation in the past and present. This sub-section of the national test was built upon a handful of multiple-choice questions and three essay questions. The guidelines to teachers scoring the tests tells us that one essay question was designed to test primarily pupils sourcing skills, a second was designed to assess sourcing, perspective recognition and corroboration, and a third question was designed to test pupils’ abilities to connect historical events to present society: for example identifying, discussing and linking present-day problems and political debate to the past, and discussing future development in light of the past (see ). Considering the nature of the test and the aims of this study, the pupil answers to the three essay questions serve the object of this study, since they were designed to test and stimulate pupils’ historical thinking and empathy about the history of Romani and other national minorities in Sweden.

The test was taken by circa 25% of all Swedish year 9 pupils, age 15 or 16. Our data, a total of 126 tests, comes from three different public secondary schools with pupils of diverse cultural and socio-economic backgrounds, where all pupils in year 9 took the national test in history (see ). The pupils’ history grades were on average just above national average. Each test varies between 7 to 12 handwritten pages in length. [First-author] collected and copied the tests at respective schools’ archive and transcribed the handwritten texts manually. The quotes presented in this article are selected to be representative for the whole cross-section and reflect more general standpoints of the pupils that we find in the data. The study is limited to pupils written responses and it is not possible to link their responses to different teachers and classroom practices.

The coding scheme was adapted from previous research on historical thinking and historical empathy as caring to fit the aims and materials of this study (Nygren, Citation2016b). In the coding scheme () historical thinking was constructed as a cognitive matter of sourcing, corroboration and perspective recognition (Lee & Ashby, Citation2001; Reisman, Citation2012; Wineburg, Citation2001).

Figure 1. Coding scheme adapted from Nygren (Citation2016b, p. 8)

Codes for historical empathy as caring relate to processes of values and emotions, namely judgment and compassion (see ; Barton & Levstik, Citation2004; Brooks, Citation2011). Noting how advocates for historical empathy as caring find it important to link history education to the present and the future, we also include codes stemming from theories of historical consciousness (Rüsen, Citation2004). Coding was conducted by [first-author] using qualitative and quantitative data software. Attention was paid to the research aims, and the audit coding trail was documented through digital and analogue memorandums, in order to avoid falling into what previous researchers have described as the coding trap (Bazeley & Jackson, Citation2013; Johnston, Citation2006). In a bid to strengthen the validity and reliability, an inter-coder reliability test was conducted by a colleague familiar with the theories, who coded randomly selected tests and passages. The agreement of coding was 90% on the level of phrases. The uncertainty was a case of differences in coding sourcing and corroboration, which was noted, discussed and addressed to safeguard reliability.

Setting and context

Romani people in public debate

Several studies have shown that the Romani in Sweden have been disadvantaged and discriminated during the twentieth and twenty-first century (Rodell-Olgac, Citation2006; Selling, Citation2013).

The national tests were designed and taken by the pupils in this study when the history and present situation of the Romani people in Sweden was brought to the front of public debate. At this time, the government had introduced A coordinated and long-term strategy for Roma inclusion 2012–2032 to safeguard the welfare of this minority (Gov. Citation2011/12:56). The government also initiated an investigation of historical abuses and human rights violations of Roma in the twentieth century resulting in the white paper, The Dark Unknown History, presented as an act to promote reconciliation (Government offices, Department of Culture, Citation2015).

Unjust treatment and sufferings of Romani people was also covered in the national press. Journalists revealed that the Swedish Police in the county of Skåne held an unofficial, and illegal, register of Romani families with approximately 4700 people of all ages and genders in order to “trace family ties” (Radio Sweden, Citation2016). A case of discrimination where a municipality had refused to fly the Romani flag on the International Romani Day also made the headlines (TT News Agency, Citation2013). While this news was new, a public debate on vulnerable EU citizens (EU-migrants) and begging arose in national media. This debate, talking about EU citizens in terms of ethnicity (Romani people) reached first peak a few months prior to the European Parliament Elections in 2014 (Hansson, Citationforthcoming). Perspectives shifted from one group of Romani people (the Swedish national minority) to another (vulnerable EU citizens).

This series of detrimental events made the public consider the past and present of the Romani in Sweden. Thus, it is of interest to see whether these morally, emotionally and ideologically charged present events made an imprint on the social sciences subjects in school.

National minorities in curriculum and national tests

Today, Swedish pupils are supposed to obtain knowledge “about the cultures, languages, religion and history of the national minorities” (The Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2011, p. 15). Pupils should “empathise with the values and conditions of others” and learn “critical thinking and [to] independently formulate standpoints based on knowledge and ethical considerations” and “critically examine facts” (Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2011, s. 9, p. 11).

Historical thinking is explicitly and somewhat archetypally captured in one of the aims of history teaching, namely: that pupil should be able to “critically examine, interpret and evaluate sources as a basis for creating historical knowledge” (Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2011, p. 163).

The national syllabus of history in secondary school underscores historical empathy by addressing several aspects of how history and historical concepts can be used: among them that pupils should develop an understanding of “their own identities, values and beliefs, and those of others,” “[h]ow history can be used to understand how the age in which people live affects their conditions and values” and pupils should meet “[h]istorical narratives from different parts of the world” and draw conclusions from them (Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2011, pp. 163–175). Furthermore, the weight of historical consciousness is being highlighted through the process of understanding “that the past affects our view of the present, and thus our perception of the future” (Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2011, p. 163). To safeguard the implementation of the syllabus, national tests have been introduced in social sciences and history. Each year, all secondary schools are randomly assigned one of four national tests in the social sciences subjects of history, civics, religion or geography. National tests are primarily constructed with the purpose of giving teachers support in assessing a pupil’s knowledge in line with the national syllabus and come with detailed assessment instructions (see ). The history test was constructed by Malmö University on behalf of the National Agency for Education and was tested at a group of diverse schools in collaboration and dialogue with teachers and pupils prior to examination day. The test itself should reflect all knowledge requirements in the secondary school syllabus of history. Making pupils write the history of national minorities and reflect upon the past and present of the Romani may be interpreted as a way for the authorities to direct attention to this in history education. For us as researchers this provides authentic data telling us what pupils may think and care about when they write history about national minorities.

Data analysis

Below, our analysis of the 126 tests is presented. First, we present the representation of thinking and caring elements in pupil responses. In the following section, the three analysed essay questions are discussed under sub-sections with headings reflecting what each question in the national test prompts. In the final sub-section, the potential interplay of thinking and caring is discussed.

The representation of thinking and caring elements

Most pupil responses were coded for content identified as historical thinking and historical empathy as caring (see ). Categories connected to historical empathy as caring were given more room than those related to historical thinking, 86,142 and 38,961 words respectively. Compassion and judging stands out as the two most frequent codes. Almost all pupils connect the past to the future while the act of sourcing evidently constitutes the least salient category in the analysed tests. Corroboration stands out as the only historical thinking category matching the quantity of the categories related to historical empathy as caring (see ).

Table 1. Summary of coded categories in students’ tests in relation to average of words per node and student.

These results alone suggest that there is a complex interplay between historical thinking and empathy. To better understand when and how pupils think and care about the history of national minorities we need to separate the three essays asking pupils to respond to questions designed to test their historical thinking and empathy as caring in different ways.

Pupils sourcing an oral narrative of Romani history

One task in the national test was designed to test pupils sourcing abilities. Pupils were asked to scrutinise trustworthiness of the story of Hans Caldaras growing up as a Roma in 1950s Gothenburg. Pupils were asked to discuss one advantage and one disadvantage with using this source in order to tell about how living conditions for Romani people were.

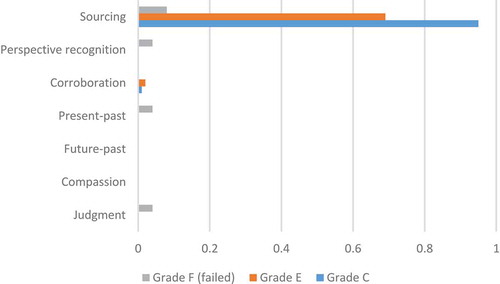

In (below) it is obvious how the task stimulated sourcing. Some pupils used corroborative approaches and referred to other sources in the test in order to contrast the trustworthiness of the oral account of Hans Caldaras about his childhood.

Figure 2. Presence of thinking and empathy elements in question 15 (average coding references per pupil and grade)

Most pupil responses received a passing grade (E) or a better grade (C) (). Passing marks were given to pupils that scrutinised or reasoned about the source in a more general sense rather than sourcing as a historian. Pupils given a C considered tendency and time aspects more ().

Table 2. Grade distribution in question 13. How did the Swedish state view Jews, Roman and Sami in the 1600’s?

Table 3. Grade distribution in question 15, Gothenburg in the 1950’s.

A failing grade (F) was given to 23 pupils (19%) failing to refer to the oral source in a narrative. In this group we find pupils who engaged in perspective recognition, linked the past to the present or made normative judgements; seemingly speculating because they did not manage to engage in the cognitive act of sourcing. The common denominator for E- and C-level answers is, on the other hand, that they are concise and focus on time and generalizability aspects, here captured in the words of a pupil:

Hans is a primary source since he’s a Roma and this happened to him, that’s why you could believe him. The text is only from his perspective and about his family’s situation. This excludes all other Romani people and gives no insight into how Romani people in general experienced it. And not all Swedes treated Romani people in that [good] way either.

Thus, historical thinking may be a challenge to a pupil in year 9 and historical empathy as caring was in this case not a constructive approach to get a passing or good grade.

Pupils and their corroboration of sources discussing national minorities

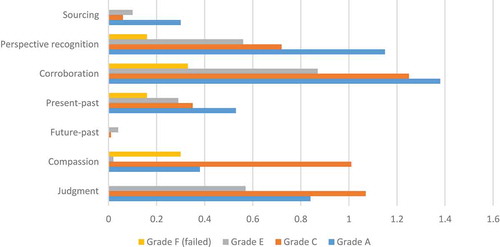

With the help from three sources – The Gypsy Law from 1637, The Royal Letter 1685 on the expulsion of Jews and A declaration from the governor of Västerbotten county, Hans Kruuse 1668 the pupils’ were assigned the task to draw conclusions about how the Swedish state look upon Jews, Romani- and Samí people in the seventeenth century. Noticeable is that historical thinking elements are far more prominent than the historical empathy ditto in pupils responses (see ).

Figure 3. Presence of thinking and empathy elements in Question 13 (average coding references per pupil and grade)

The cognitive act of critical thinking or sourcing was not as evident in the answers: merely two of the pupils who achieved the highest grade engaged in scrutinising sources. In other words, the question stimulated historical thinking abilities in general and especially corroboration and perspective recognition. The fact that the empathy elements, such as compassion, judgment and present-past were present suggests an interplay of thinking and caring in the pupil answers.

Most pupils managed to get a passing grade on this assignment () and we find that corroboration was needed in order to attain a passing mark in the assignment. Characteristic for several of the grade A answers is a pattern where corroboration was followed by an instant moral and judgmental reaction and affective response towards the state’s actions. Pupils would often describe past events in terms of it being a violation of present day human rights. This is by all grade A pupils and most grade C pupils followed by perspective recognition, where they drew parallels between the seventeenth-century legislation and orders to kill and expulse Jews-, Roma and Samí people and other historical events in past and present.

Noteworthy is that well-substantiated perspective recognition seems to be key in order to achieve the best grade in this assignment. Alongside with reasoning about the Romani peoples’ situation in the past in light of present-day antiziganism, i.e. manifesting historical consciousness and empathy in terms of a present-past discussion, the extent of perspective recognition constitutes a clear divide between pupil grades. Noticeable is that more than 30% of pupils, regardless of grade, emphasised the similarities between seventeenth-century Sweden and the Holocaust (without being told to do so).

Evident in the pupil answers were that affective stances and compassion may compensate for a deficiency in corroboration: this phenomenon is judging by the coding references what differs an answer graded C from an answer graded A. This is illustrated in the pupil answer (graded C) below:

During the 17th century they were tough on non-Christian ethnic groups. “We want to preserve the Christian religion in Sweden”, the king wrote in 1685. A few years earlier in 1637 they wanted to kick all gypsies out from Sweden and threatened to kill all of those who weren’t gone after the 8th of November. It seems like people throughout all times want to get rid of things that isn’t like themselves. Hitler wanted to get rid of Jews and Romani people almost 300 years after the law was written. It shows that humans pay more attention to religion than the person behind her god, praying, just as you do. To be able to live together we have to see beyond our differences, whether it’s about religion, skin colour or something else and instead focus on our similarities. We are all humans of flesh and blood. We live on the same planet. We have to take responsibility together.

Paying little attention to corroboration and engaging in perspective recognition briefly, the pupil ends with a seemingly normative predication in human rights and universal moral values. It is quite common for pupils to take a personal stance in their responses stating for instance: “I personally believe that.”, “When I read that I felt.”, and “Being a Swede, I feel embarrassed”. Pupils’ may, in line with historical empathy as caring, make judgments and show compassion explicitly, but this seems in these cases to come at the expense of the aspects of historical thinking implicitly asked for in the assignment.

Pupils reflecting upon the past and present of Romani people

In today’s Sweden Romani people live in huge alienation and to many of them, discrimination and prejudice is the reality they live in every day. We have a past and a present to feel ashamed for concerning the Romani people. Now, it’s about doing what’s right, so we don’t need to have a future to be ashamed of too.

With the words of Minister of Integration Erik Ullenhag above (as quoted in Dagens Nyheter in 2012) as a backdrop, the pupils were assigned to describe some possible continuances for the situation of the Romani people in Sweden and use past and present events in order to strengthen their argumentation and reasoning.

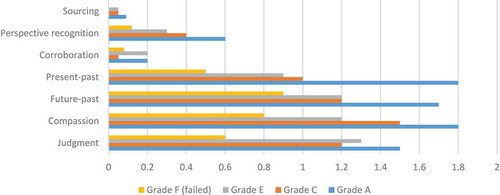

In stark contrast to the previous test questions, the coded elements point in one direction: historical empathy as was stimulated by this question (see and ). All pupils with a passing grade linked the history of the Romani people to the present and future. A majority of them did so with compassion and judgments intertwined – caring for the Romani people of the past and present by highlighting and reacting to suffering and oppression. 79 of 120 pupils explicitly mentioned and addressed the problem of old prejudices. As on pupil stated: “In the 19th century, one believed that the Romani were thieves and it has been a continuance since. Even today some people think of the Romani as thieves and believe that gypsies (women) hide things under their big skirts.” Frequently, these statements were interwoven with a discussion on how prejudices hinder integration and harmony in society. Another theme discerned in the responses was a worry about current xenophobic and nationalist leanings in society (23 of 120 pupils). Some pupils described nationalist party Sverigedemokraterna (The Sweden Democrats) and neo-Nazi party The Nordic Resistance movement as potential threats for the national minorities, stating for instance: “With the growing public support for SD, you’ll never know what will happen. […] It’s important that you’ll never let such parties set the agenda and get what they want.” Another pupil suggested a ban on xenophobic parties, a proposal made by several other pupils to address the issue of growing racism, stating that:

Nationalist parties such as the Sweden Democrats show a strong tendency of making it harder for other ethnicities. One concrete example is the Sweden Democrats’ idea about scrapping free health-care for non-Swedish citizens. My suggestion is therefore to ban these parties so that development for the Romani peoples can be safeguarded.

Figure 4. Presence of thinking and empathy elements in question 18 (average coding references per pupil and grade)

In addition, a vast majority of the pupils not only expressed a wish to aid and help people in the past and present but also called to action on an individual level, for instance:

It IS a continuance that the Romani are treated worse. And it HAS been a continuance in which the Romani have lived under oppression and threat. It is time for a change. It has gone too far for a too long time. WE shall change their present situation in Sweden. It is being stated that we’re a very peaceful country free from racism. We are not. Racism is virulent and blatant. Because where there are different views, there will always be xenophobia. The most likely future and continuance is that the situation for the Romani people slowly turn to better seen to what has happened since the 17th century, but I don’t care about this statistical observation. I believe it’s time for each individual to shape up.

All pupils showed compassion and judged people, events and institutions of the past when asked to reflect upon this question. However, answers show that they are torn on present society and politicians. Where one group of pupils painted a picture of Sweden with equity, freedom of religion, democracy and human rights as a fact for all citizens, another group presented a grim picture with racism and xenophobia growing rapidly. This gap between appreciation and judgment of the national state and politicians was evident in different attitudinal stances towards the state and government where, for instance, a critical pupil found that:

He who “sits behind the wheel” seems to have some good thoughts on a better future for the Romani, but as seen in the sources the municipal authorities in Växjö refused to raise the [Romani] flag on their day. This happened a year after Ullenhag publicly announced that the Romani would get a new start. This shows that Ullenhag as most other politicians are full of empty words.

In contrast to the answer above, other pupils praised Minister of integration Ullenhag and showed great faith in the revised 2010 framework convention and laws for the protection of National Minorities and their languages as well as the country, highlighting how: “[t]oday, Romani people might live in houses, might go to school and are by law equal and have the same rights as any Swedish citizen.” Similarly, another pupil wrote that “Sweden is a good country which always do its best for the people when needed,” a statement which captures the essence of answers with a positive attitude towards the state.

Topics on vulnerable EU-citizens and Romani people of today were part of 38 pupils’ responses. The discussion in all cases but one related to begging. What most of the 38 pupils shared was a great extent of compassion and judgment, but the values conveyed in their analyses and judgments stemmed from different positions of the political spectrum: ranging from a faith in the strong and interventionist state to the aforementioned discourse of individual good-will. Many of the pupils discussed integration and inclusion in terms of job-possibilities, for instance: “I don’t think we should give them stuff. Perhaps we should offer them jobs, not hiring them, but let them run errands for a few bits or something like that.” Another pupil wrote: “[g]ive them a chance, a job as a cashier at an ICA supermarket! A seat in the parliament or in local politics would give them a possibility to become a part of society. A chance to show that they’re people.” While the first pupil expressed thoughts in line with a neo-liberal ideology of letting the EU-citizens live out of alms and upholding present dichotomies, the second pupil appealed to both the state and the individual, in a wish to include the Romani people of EU in the societal community. A third pupil addressed the same topic by saying: “I’m of the impression that they don’t stand up for themselves and fight for their rights. If they want welfare they have to participate and engage in the work themselves,” meaning that the state has done enough and that it is up to each individual to work for their own future. Moreover, one of the pupils addressed a phenomenon where the existence of the Romani beggar makes feelings of guilt filter through the leaky bucket of social norms and ethics:

In today’s society there are Romani people begging at almost every grocery store and in the streets too. Most people look at the Romani with contempt in their eyes and there are very few giving the beggars anything. A common topic of conversation here in [the town] is how annoying it is that there are beggars everywhere. That is just awful! It is the Romani people that are being driven to begging that are suffering. Not we who glance at them while we go shopping for a week’s worth of food.

The pupil answer might be interpreted as questioning whether it is reasonable for a citizen to hold negative feelings when facing their own repressed impulses of taking moral responsibility for other humans. Thus, the pupil sheds new light on the difficulties and attitudes towards meeting and including the other: meeting vulnerable EU citizens forces the grocery shopping citizen make moral decisions in his or her everyday life. In addition, the answer holds elements of perspective recognition and judgment, and therefore display what dimensions’ and possibilities history education may hold.

The relationship of thinking and caring

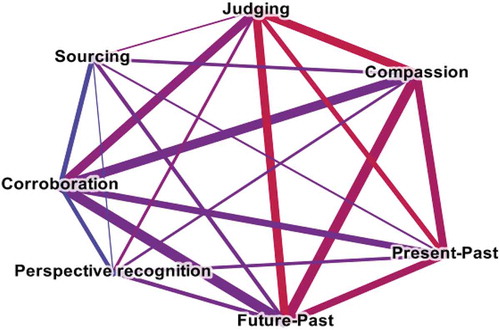

A statistical analysis of categories of historical thinking and empathy as caring across all pupil responses to questions designed to assess thinking and caring makes evident that they are intertwined when pupils reason and write about the national minorities in a national test. A calculation of the interplay of the presence and absence of different categories, using Jaccard’s correlation coefficient,Footnote2 highlights links between aspects of historical thinking and caring. shows how primarily the categories of judging, compassion and corroboration were evident in pupils responses when they considered the past, present and future of national minorities using primary sources. Evidently pupils did not spend much time on sourcing in their responses even though they faced primary sources in the assessments.

In edges are sized with regard to calculated weight using Jaccard’s correlation coefficient. Nodes connected to historical thinking are blue, whilst those related to historical empathy are red. Overlaps and cross-references are mixed and therefore purple. What we see in this network is a mix of aspects of historical thinking, especially corroboration, with aspects of historical empathy as caring on a more aggregated level. This is also evident on a more detailed individual level. When close reading the pupils’ answers it can be seen how corroboration stimulates compassion and normative judgments within the same question. Following is a pupil answer to the question How did the Swedish state view Jews, Romani and the Samí in the 17th century?

The state hated all of these groups in the 17th century. In both source 1 and 2 they’ll expulse ethnic groups from the country, which is a very serious violation and in that way these groups were looked down upon. I think this is absurd and I think it looks like a mini-holocaust since it [the letter] states that all must leave the country within two weeks’ notice. The message couldn’t possibly have been read by all Jews in two weeks, and within that timeframe they should, accordingly, be out of the country. In the 17th century, communication and transportation aspects made it impossible to escape within that timeframe. The state must therefore have planned on killing, i.e. mass-exterminating, them.

Figure 5. Categories presented and clustered by coding similarity

Note: The calculation is based on pupils’ answers to questions “How did the Swedish view Jews, Romani and the Sami in the 1600’s?” and “The Minister of Integration reflects on the future.

In this rather short extract, the pupil corroborates and expresses negative feelings and judgment towards the state’s actions, as well as engages in the act of historical consciousness in a subtle way: drawing parallels to the Holocaust and connecting the past to the present. This answer, holding both corroborative elements and judgments, show us what grasp of history a 15-year-old pupil might possess and illustrates how a pupil can respond and react morally when they are presented to past events, processes or primary sources. In addition, a spatial and temporal contextualization is being made considering the transportation endeavours in the seventeenth century: something that is not mentioned explicitly nor implicitly in any of the attached sources. This pupils response shows how thinking and caring may be intertwined when the curriculum is enacted.

Concluding discussion

In a time of political efforts to promote the Rights of Roma in Sweden and EU, the national test was designed to prompt pupils’ abilities to think and care about the history of the Romani people. Pupils’ responses showed moral reactions to treatment of minorities in both in the past and present. They engaged with intercultural by combining historical thinking and empathy. We find a strong positive correlation between judging and present-past, suggesting that past abuses and discrimination from the state can strike a chord so vibrant it resonates through 400 years of history. Many pupils’ moral foundations are shaken and the self-image of Sweden as a country free from racism and discrimination is questioned.

In pupils responses we find categories of historical thinking and caring separated and, more often, tightly interlinked. Sourcing is something the adolescents engage in, with few exceptions, when it is explicitly asked for. When pupils critically scrutinise an oral source from the history of the Roma, they do nothing but sourcing. Pupils using historical empathy as caring to respond to this fail this question designed to assess sourcing. The separation of sourcing from caring dimensions is, however, not just a matter of the design of the specific test question. The absence of sourcing elements in other essay questions indicates that sourcing is not an integrated part of pupils’ historical thinking and caring. Even when they are asked to scrutinise primary sources, they do not use sourcing without a specific prompt. Although striking, this does not mean that the adolescents are uncritical or unable to demonstrate a critical faculty. On the contrary, they take ideological, critical and moral positions when discussing the present and future in light of the past. Learning from the past also resulted in a critical stance towards the state as an agent upholding human rights in the present.

The most common category of historical thinking is corroboration. When close reading the answers to a question asking pupils to corroborate sources describing the situation of Jews, Romani- and Sámi people in the seventeenth-century Sweden it is evident that corroboration stands out as a springboard for further comparison, judging and compassion, present-past discussion as well as perspective recognition and more general conclusions. In contrast to previous research (Nygren, Citation2016b; Nygren et al., Citation2014; Wineburg, Citation1998, Citation2001), scrutinising sources in terms of corroboration not only stays an “inner cognitive process” and a habit of mind, but is being reflected in textual coverage as well. Even if the current national syllabus for history underlines the importance of evaluating sources we find that this is not part of pupils’ corroboration and of sources. Also, on an aggregated level we find that corroboration is tightly interlinked with categories of historical empathy as caring, not sourcing and perspective taking, (see ) in contrast to the theoretical separation between thinking and caring. In individual responses we find, instead, the cognitive thinking skills of corroboration and perspective recognition are often followed by pupils’ moral judgments. Also, in questions designed to prompt historical thinking we find a knee-jerk moral response to corroboration.

A strong focus on corroboration and historical empathy as caring intertwined seem to be key for pupils in order to score well on this test. While too much compassion without contextualising the source and supporting conclusions, i.e. a lack in using historical evidence, may result in a lower grade. This result constitutes a contrast to the Swedish national syllabus in history, which is emphasising the importance of critical thinking (Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2011). The amount of pupils failing the assignment prompting historical empathy as caring, and categories of present past and future, is significantly higher than the assignment assessing historical thinking (see and ). This indicates that historical empathy as caring may be a greater challenge than historical thinking for pupils. This raises the question of how history teaching of an ethnically, politically and morally charged topic of citizenry, such as the history of the Romani, may be operationalized in order to implement and control what thinking and caring processes are being stimulated.

Table 4. Grade distribution in question 18. The Minister of Integration reflects on the future.

While one test question evidently prompts corroboration, a correlation can be seen between high grades and more frequent normative statements and historical empathy as caring. This can be interpreted as teachers taking moral stances into account, in contrast to the rigorous assessment framework at hand, when historical thinking skills are supposed to be assessed (Alvén, Citation2017b). If this is the case, it may be an issue of lacking equivalence considering theories of national accountability (Ball et al., Citation2012; Samuelsson & Wendell, Citation2016). It may also be interpreted as an enactment of a democratic value system, where teachers implement values stated elsewhere when assessing pupils’ responses. It is also likely that a response corroborating primary sources may become more qualified if the pupil reflects upon the findings in light of relations to values and linking the data to the present and the future.

It is also evident that reflecting upon the past and present of the Romani people made pupils reflect upon the values that constitutes the moral foundations of Swedish identity, namely that of Sweden being a standard-bearer in human rights and democracy. Some pupils question current politics while other find the current politics promising for the future. At first glance, this might seem like an issue of different ideological leanings (left-right) in politics, but apparent in the pupil answers is that there is a firm belief that each individual is a part of this attitudinal shift and that immense structural change can be achieved by “looking to the future – being kind, inclusive, respectful and generous to others. What can be interpreted as a matter of clashing ideologies can be interpreted as a tendency towards egalitarian individualism in society, where there is an on-going shift (or opposing views) in agency wherein the state and its role in upholding democracy and human rights is becoming less visible in relation to individual alms and good-will. The history of national minorities stimulated pupils to consider issues of inequality and political challenges and possibilities, which may be interpreted as a potential for history education to be a moral training ground for civic agency in line with advocates for historical empathy as caring (Barton & Levstik, Citation2004). In light of a historical thinking approach, we find that pupil responses go way beyond the academic tradition of studying the past like a historian. It is evident how contemporary press and media breaks through when pupils consider the present and future of the Romani – a fact that underscores the importance of multiperspectivity and stresses a need for contextualising when discussing recent history and citizenship issues in times of alternative facts and think-tanks with ideological interests. What pupils encounter are issues that are important and hard to navigate in a neutral manner. It is possible that history education is in need of a new, broader, definition of critical thinking than what historical thinking entails. The results of this study makes visible that the theoretical divide between historical thinking and empathy as caring is not a divide in practice. Instead we find that pupils caring and thinking about the history of national minorities may stimulate them to write history in nuanced ways. Pupils treat the past as historical but also practical. However, the practical approach often lacks sourcing aspects, which is a challenge in a world where history may be used in deceitful ways, not least online (Wineburg, Citation2018). Scrutinising the source also become important when dealing with debated topics like the history of minorities. The design of the national test may also separate sourcing from other aspects of historical thinking and caring, but this split need to be further investigated since it is also evident in some previous research (Nygren, Citation2016b; Rosenlund, Citation2016). Noting the credibility of the source is central when navigating the past and present.

We see a need for further research in history education to explore in-depth how current history teaching may stimulate the interplay of thinking and caring; how practice can scaffold pupils’ critical thinking in combination with an understanding of diversity and human rights, not least in ideologically and emotionally charged issues in the history classroom. Noting how we only start to map some aspects of this in pupils’ tests we call for more practice-based research. We ask: If history education is to promote thinking and caring about the past, then what does this mean for the complexity of practice? If sourcing is separated from a more practical approach to the past, then how may this divide be overcome? How can teachers in on-going teaching promote corroboration and nuanced judgements in hot historical topics? In what end should education start to best promote empathy and thinking – is a starting point in the practical past more engaging than a start in the historical past? Further naturalistic investigations and experimental design studies would be helpful to better understand how different methods and materials may stimulate pupils to consider the past and present of people previously unknown to them.

The pupils in this study show a great extent of caring, compassion and empathy towards the past and present. Pupils being surprised by historical facts, and their affective and normative responses, may serve as an indicator that our national minorities and their past are usually given little room in secondary school history practices. The national syllabus of history might therefore not be fully enacted; thus, failing to fulfil its role in a national accountability system. It is evident that this historical encounter truly holds a political and ideological dimension, which pupils think and care about in many ways. This study of a cross-section of adolescents taking the national test in history shows that the pupils, in line with the recommendations of international and national guidelines, perhaps for the first time in their lives, are considering the past and present of the Romani in Sweden.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Olle Nolgård

Olle Nolgård is a Ph.D. Candidate and researcher in history education at the department of Education, Uppsala University. His research interests centre on assessment and learning of history, the history of the minorities and critical perspectives on history and global citizenship education.

Thomas Nygren

Thomas Nygren, PhD, is Associate Professor at the department of Education, Uppsala University. His research interests centre on history education, the digital impact on education, critical thinking and human rights education. His current research projects investigate students’ news literacy, global citizenship education, and critical thinking across disciplinary boundaries.

Notes

1. The Framework was signed in 2000.

2. Jaccard’s similarity coefficient is used for comparing similarity (or diversity) between two sample sets. Thus, this similarity metric enables us to calculate and see non-linear correlations between our different sets of nodes, i.e. to what extent the different elements of thinking and empathy as caring occur at the same time and how they interplay.

References

- Alvén, F. (2017a). Making democrats while developing their historical consciousness: A complex task. Historical Encounters Journal, 4(1), 52–67.

- Alvén, F. (2017b). Tänka rätt och tycka lämpligt: historieämnet i skärningspunkten mellan att fostra kulturbärare och förbereda kulturbyggare ( Diss). Malmö: Malmö Högskola

- Ball, S., Maguire, M., Braun, A., Perryman, J., & Hoskins, K. (2012). Assessment technologies in schools: ‘deliverology’ and the ‘play of dominations’. Research Papers in Education, 27(5), 513–533.

- Barton, K. C., & Levstik, L. S. (2004). Teaching history for the common good. Mahwah, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Bazeley, P., & Jackson, K. (2013). Qualitative data analysis with NVivo (2nd ed.). (2nd ed.). London, UK: SAGE.

- Brooks, S. (2011). Historical empathy as perspective recognition and care in one secondary social studies classroom. Theory & Research in Social Education, 39(2), 166–202.

- Brooks, S. (2014). Connecting the past to the present in the middle-level classroom: A comparative case study. Theory & Research in Social Education, 42(1), 65–95.

- Bruley, E., & Dance, E. H. (1960). A history of Europe? Leyden: A.W. Sythoff.

- Council of Europe. (1995). “The European idea in history teaching 1953” in Council of Europe (1995). Against bias and prejudice. The Council of Europe’s work on history teaching and history textbooks. Recommendations on history teaching and history textbooks adopted at the Council of Europe conferences and symposia 1953 – 1995. Strasbourg: Council for Cultural-Cooperation (CDCC).

- Council of Europe. (2001). Recommendation Rec (2001)15 of the Committee of Ministers to member states on history teaching in twenty-first-century Europe. Strasbourg: Author.

- Davis, O. L., Yeager, E. A., & Foster, S. J (red.). (2001). Historical empathy and perspective taking in the social studies. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- De La Paz, S., Felton, M., Monte-Sano, C., Croninger, R., Jackson, C., Shim Deogracias, J., & Polk Hoffman, B. (2014). Developing historical reading and writing with adolescent readers: Effects on pupil learning. Theory & Research in Social Education, 42(2), 228–274.

- Endacott, J. L., & Brooks, S. (2018). Historical empathy: Perspectives and responding to the past. The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning, 203–226.

- Foster, S. (1999). Using historical empathy to excite students about the study of history: Can you empathize with Neville Chamberlain? The Social Studies, 90(1), 18–24.

- Foster, S. (2001). Historical empathy in theory and practice. In O. L. Davis, E. A. Yeager, & S. J. Foster (Eds.), Historical empathy and perspective taking in the social studies (pp. 167–180). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Foster, S. J., & Yeager, E. A. (1999). “You‘ve got to put together the pieces”: English 12-year-olds encounter and learn from historical evidence. Journal of Curriculum and Supervision, 14(4), 286.

- Goodlad, J. (Ed). (1979). Curriculum and inquiry. New York: Mc Graw –Hill Book Company.

- Government offices. A coordinated and long-term strategy for Roma inclusion 2012–2032, Skr. 2011/12:56

- Government offices, Department of Culture. (2015). The dark unknown history: White paper on abuses and rights violations against Roma in the 20th century. Stockholm: Fritze.

- Hansson, E. (forthcoming). “Det känns fel”: angående det svenska samhällets reaktioner mot tiggande EU-medborgares närvaro. [“It feels wrong”: the Swedish societies’ reactions toward the begging EU-Citizen] ( Diss). Uppsala: Uppsala Universitet (unpublished manuscript)

- Historielärarnas förening, HLFÅ. (2007). Historielärarnas förenings årsskrift [Swedish association of history teachers’ annual report of 2007] 2007.

- Indzic Dujso, A. (2015). Nationella minoriteter i historieundervisningen: Bilder av romer i Utbildningsradions program under perioden 1975-2013. [National minorities in History Education: narratives of the Roma in Utbildningsradions programs’ 1975 – 2013]. Umeå: Umeå universitet.

- Jensen, B. E. 1997. Historiemedvetande: Begreppsanalys, samhällsteori, didaktik [Historical Consiousness: Concept analysis, Social theory, Didactics]. In C. Karlegärd & K. G. Karlsson (Eds.), Historiedidaktik [History Didactics] (pp. 72–81). Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Johnston, L. (2006). Software and method: Reflections on teaching and using QSR NVivo in doctoral research. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 9(5), 379–391.

- Kohlmeier, J. (2005). The impact of having 9th graders” Do History”. The History Teacher, 38(4), 499–524.

- Lee, P. (1992). History in schools: Aims, purposes and approaches. A reply to John White. In P. Lee, J. Slater, P. Walsch, & J. White (Eds.), The aims of school history: The national curriculum and beyond (pp. 20–34). London: Institute of Education.

- Lee, P., & Ashby, R. (2001). Empathy, perspective taking, and rational understanding. In O. L. Davis, E. A. Yeager, & S. Foster (Eds.), Historical empathy and perspective taking in the social studies (pp. 21–50). New York, NY: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Levstik, L., & Thornton, S. (2018). Reconceptualizing history for early childhood through early adolescence. In L. M. Harris & S. A. Metzger (Eds.), The wiley international handbook of history teaching and learning [Elektronisk resurs] (pp. 473–494). New York: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Lozic, V. (2010). I historiekanons skugga: historieämne och identifikationsformering i 2000-talets mångkulturella samhälle ( Diss). Lund: Lunds universitet

- Mattlar, J. (2014). De nationella minoriteterna i läroplan och läroböcker [The minorities in curricula and textbooks]. In M. Sandström J. Stier & L. Nilsson (Eds.), Inkludering - möjligheter och utmaningar [Inclusion: Possibilities and challenges]. 1 Suppl. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Mattlar, J. (2016). Ett folk utan land? – Den nationella minoriteten romer i svenska läroböcker [A people without a nation? – The roma minority in Swedish textbooks]. In N. Askeland & B. Aamotsbakken (Eds.), Folk uten land? : Å gi stemme og status til urfolk og nasjonale minoriteter [A people without a nation?: Giving voice and status to the indigenous and national minorities] (pp. 209–224). Kristiansand: Portal.

- News Agency, T. T. (2013). Växjö nobbade romsk flagga. [Växjö turned down the Romani Flag] SVT nyheter Småland. 8th of april. Retrieved from www https://www.svt.se/nyheter/lokalt/smaland/vaxjo-nobbade-romsk-flagga (2019-03-22)

- Nordgren, K. (2006). Vems är historien?: historia som medvetande, kultur och handling i det mångkulturella Sverige ( Diss). Karlstad: Karlstads universitet, 2006

- Novick, P. (1988). That noble dream: The “objectivity question” and the American historical profession. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- Nygren, T. (2011). History in the service of mankind: international guidelines and history education in upper secondary schools in Sweden, 1927–2002 ( Diss). Umeå: Umeå universitet

- Nygren, T. (2016a). UNESCO teaches history: Implementing international understanding in Sweden. In P. Duehdal (Ed.), A history of UNESCO: Global actions and impact (pp. pp.201–230). Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillian.

- Nygren, T. (2016b). Thinking and caring about indigenous peoples’ human rights: Swedish students writing history beyond scholarly debate. Journal of Peace Education, 13(2), 113–135.

- Nygren, T., Haglund, J., Samuelsson, C. R., Af Geijerstam, Å., & Prytz, J. (2018). Critical thinking in national tests across four subjects in Swedish compulsory school. Education Inquiry, 10(1), 56–75. doi:10.1080/20004508.2018.1475200

- Nygren, T., & Johnsrud, B. (2018). What would Martin Luther King Jr. Say? Teaching the historical and practical past to promote human rights in education. Journal of Human Rights Practice, 10(2), pp. 287–306.

- Nygren, T., Sandberg, K., & Vikström, L. (2014). Digitala primärkällor i historieundervisningen: En utmaning för elevers historiska tänkande och historiska empati [Digital primary sources in history education: A challenge for students’ historical thinking and historical empathy]. Nordidactica, 2, 208–245.

- Nygren, T., & Vikström, L. (2013). Treading old paths in new ways: Upper secondary students using a digital tool of the professional historian. Education Sciences, 3(1), 50–73.

- Radio Sweden. (2016). Roma Register: State guilty of ethnic discrimination. Sverigesradio.se. 10 June. http://sverigesradio.se/sida/artikel.aspx?programid=2054&artikel=6450629 (2019-03-22)

- Reisman, A. (2012). Reading like a historian. A Document-Based History Curriculum Intervention in Urban High Schools, 30. doi:10.1080/07370008.2011.634081.

- Rodell Olgaç, C. Den romska minoriteten i majoritetssamhällets skola: från hot till möjlighet [The Roma as a minority in the mainstream schools: from a threat to a hope for the future] ( HLS förlag, Diss). Stockholm: Stockholms universitet, 2006

- Rosenlund, D. (2016). History education as content, methods or orientation?: a study of curriculum prescriptions, teacher-made tasks and student strategies ( PhD. Diss.). Peter Lang.

- Rüsen, J. (2004). Berättande och förnuft: Historieteoretiska texter [Narrative and sense: History theoretical texts]. Göteborg: Daidalos.

- Samuelsson, J., & Wendell, J. (2016). Historical thinking about sources in the context of a standards-based curriculum: A Swedish case. The Curriculum Journal, 27(4), 479–499.

- Selling, J. (2013). Svensk antiziganism: Fördomens kontinuitet och förändringens förutsättningar [Swedish Antiziganism: The continuity of prejudice and the prerequisites of change]. Limhamn: Sekel.

- Shemilt, D. (2009). Drinking an Ocean and pissing a cupful. In L. Symcox & A. Wilschut (Eds.), National history standards. The problem of the canon and the future of teaching history (pp. 141–210). Charlotte, Carolina: Information Age Publishing.

- Stolare, M. (2017). Did the Vikings really have helmets with horns? Sources and narrative content in Swedish upper primary school history teaching. Education, 45(1), 36–50.

- Swedish National Agency for Education. (2011). Curriculum for the compulsory school, preschool class and the recreation centre 2011. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Wahlström, N., & Sundberg, D. (2015). Theory-based evaluation of the curriculum Lgr 11 (No. 2015: 11). Uppsala: IFAU-Institute for Evaluation of Labour Market and Education Policy.

- White, H. (2014). The practical past. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

- Wineburg, S. (1998). Reading Abraham Lincoln: An expert/expert study in the interpretation of historical texts. Cognitive Science, 22(3), p.319–346.

- Wineburg, S. (2001). Historical thinking and other unnatural acts: Charting the future of teaching the past. Temple University Press: Philadelphia.

- Wineburg, S. (2018). Why learn history: (when it‘s already on your phone). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Wineburg, S. S. (1991). On the reading of historical texts: Notes on the breach between school and academy. American Educational Research Journal, 28(3), 495–519.

Appendices

Table A1. The analyzed essay questions as found in the English language version of the national test.

Table A2. A description of schools through demography.