ABSTRACT

National and regional variations in school systems, have often been explained in comparative school governance research in the Nordic countries with variations in long-standing traditions in curriculum development, characterised by a dichotomy between an Anglo-American curriculum tradition and a German/European continental tradition of Didaktik. These categories have been employed to explain the characteristics of nation-specific teaching professions, such as the Swedish, Finnish, Norwegian, or German, US and English. This article suggests that the dichotomies in question complicate understandings of teachers and how they are governed in different national contexts. We investigate these relations by an analysis of quantitative data from the OECD TALIS study on how teachers receive formal feedback and appraisal in six countries, and an analysis of qualitative data in feedback technologies in Germany and Norway. Drawing on the empirical material, we suggest that the Didaktik-curriculum dichotomy might overemphasise the role of state governance in relations between different actors in school systems. Instead, the article imply that we need to discuss the role of parents and peers in educational governance more thoroughly. To further theory, it is suggested investigating teachers in the field of tension between state and civil society, and the role of teachers as civil servants and/or administrators.

1. Introduction

Several countries have implemented a relatively new set of governing approaches that emphasise performance measurement. Using data, national and local authorities, school leaders, and teachers across much of the western world are expected to initiate concrete actions to improve student achievement (Altrichter & Maag Merki, Citation2016; Bondorf, Citation2012). This development can be considered part of a contemporary global policy message, also evident in education reforms within the Nordic context, which is communicated through similar concepts (e.g. accountability, evidence and decentralisation) that tend to lead to developments in education directed towards achieving universal goals (Prøitz, Mausethagen, & Skedsmo, Citation2017; Simola, Rinne, Varjo, & Kauko, Citation2013).

Nevertheless, local, regional and national variations more often characterise the field of education (Hopmann, Citation2015). For example, accountability in the USA is described as high-stakes, owing to the use of incentives and sanctions related to student performance data, while Continental European and Nordic countries are often recognised as being low-stakes, “half way accountability” or “soft accountability”, owing to a lack of such incentives and sanctions (Easley & Tulowitzki, Citation2016; Hatch, Citation2013). Moreover, it can be argued that manifestations of decentralisation differ between the USA and countries in Northern Europe (Gunter et al., Citation2016), including variations in understandings and the roles of the state as the centre of national governance of education or as a facilitator for arenas of governance in education (Ball, Citation2008; Mølstad, Citation2015). Also, what is considered as evidence in education has been observed to differ between contexts, regions and countries (Rieper & Hansen, Citation2007, Gough, Tripney, Kenny, & Buk-Berge, Citation2011). National and regional variations in school systems and ideas and values about schooling have often been explained as reflecting variations in approaches to education in terms of emphasis on input or output and/or variations in long-standing traditions in curriculum development, characterised by a dichotomous division between an Anglo-American curriculum tradition and a German/European continental tradition of Didaktik (Hopmann, Citation2015; Karseth & Sivesind, Citation2010; Lundgren, Citation2006; Wahlström, Citation2016). These comparative categories have proven extremely useful in many studies, in particular for research and teaching on curriculum theory and comparative education. Moreover, they have been used to understand the local, regional and national variations in how particular teachers are expected to improve student achievement (Hopmann, Citation2015, Mølstad, Citation2015; Tahirsylaj, Citation2019; Wermke, Olason Rick, & Salokangas, Citation2019).

The aim of this article is to discuss issues which we have encountered while working with the categories of curriculum vs. DidaktikFootnote1 and comparative conceptualisations of the teaching profession. We argue that the historically developed more or less dichotomously employed categories of curriculum and Didaktik might overemphasise the role of state governance in terms of the relations of different actors in contemporary-decentralised school systems. In the context of new methods of governing education by results and outcomes, there may be more room for the individual teacher, student or parent to influence the direction of development, forming a conglomeration of influences rather than a singular state-based governance. This complicates the application of dichotomies in explaining governance in education.

In this article, we will make our conceptual argument in relation to a Didaktik-curriculum dichotomy, by employing empirical material which we have compiled and collected in various comparative studies. Using empirical material from different national contexts, both of qualitative and quantitative nature, we will elaborate on dichotomous categories, and in particular the distinction of curriculum and Didaktik traditions, and their potential use in depicting more complex pictures of stakeholder groups, such as teachers as professional peers and parents of students in schools. Professional peers represent the intra-professional influence that mediates between teachers inside schools, while the other group, parents, constitutes an influence from outside the school, one which places teachers within the broader framework of civil society.

The paper’s conceptual discussions draw, firstly, on a comparative analysis of a set of quantitative material from TALIS – the OECD Teaching and Learning International Survey – in combination with, secondly, two exemplary country vignettes, including interview material with teachers. Employing the TALIS material affords us the opportunity to compare teachers’ reports on their daily working experiences with appraisal and feedback, which can also be seen as data in education. In total, we base our analyses on the answers of approx. 28,000 teachers and 1,800 principals from a strategic sample of different countries representing the Didaktik or curriculum sphere. We will test two hypotheses that relate conceptualisations of the national teaching professions associated with Didaktik or curriculum traditions and what teachers in the TALIS study report on formal feedback and appraisal in the school systems. The qualitative material which we employ in this article, is from Germany and Norway. The countries are interesting to compare more deeply due to recent education reforms. Both countries come from a traditional input-regulated or Didaktik sphere, and have recently implemented reforms that emphasise stronger output steering, and thereby might have moved to a virtual curriculum category.

In order to organise our discussion, the article is structured in the following way: We start with a section, in which we discuss different concepts which explain the use of “data” in education. Here we present variations in the apparent contemporary global policy message, which is communicated through similar concepts (e.g. accountability, evidence and decentralisation). In the next section, we elaborate on comparative conceptualisations of the teaching profession, its governance and how national differences have been explained by employing a Didaktik-curriculum dichotomy. These sections will function as presentations of the theoretical framework of this article. In the following section, our quantitative and qualitative material is presented in detail. In the last section, we present a discussion of conceptual considerations that might complement the Didaktik vs curriculum paradigm in future research.

2. Research on data use in education

With growing interest in data use in education, a range of countries have implemented various governance and governing approaches (Ozga, Citation2009; Prøitz et al., Citation2017). There has been a flurry of studies in which data is used as evidence in the organisation of public education, above all in the USA. Coburn and Turner (Citation2011) in their literature review examine the ways in which data are used depending on organisational factors such as access to data, time, norms of interaction and leadership. Little (Citation2012) argues for the necessity of enhancing knowledge about how local practices both construct and instantiate organisational routines and processes. These approaches emphasise methods and perspectives that open up alternative insights into the varied activities of local actors. In other words, governance research which relies too much on examining policies might lead to methodological nationalism, meaning that the various levels of public education are placed into the background, and empirical, e.g. national, cases are seen as having a natural unity with no variation and fragmentation evident among policy documents and policymakers, which would thereby overemphasise the role of the state in governing public education.

In their literature review on data use in studies written in English, German and Scandinavian languages, Prøitz et al. (Citation2017) find six broadly defined investigative modes (overlapping and non-exclusive) of studies on data use in education: (1) implementation studies; (2) explorative studies; (3) overview studies; (4) discussion studies; (5) methodological studies; and (6) system-critical studies. The two investigative modes of “implementation” and “explorative” studies consist mainly of Anglo-American examples that focus on the overall school system, based on qualitative empirical data. Most of these studies are concerned with improving data use in schools – and thus educational quality and learning outcomes – by identifying the factors that would positively contribute to this development. The investigative modes of “overview” and “discussion” studies are most often observed among studies written in the German language. These tend to be mostly theoretical overviews and review studies that discuss opportunities for data use in school development on the one hand, and criticise the development on the other, which together appear to provide duelling perspectives in a nuanced debate.

The investigative modes of “methodological” and “system-critical” studies are mostly found among the studies written in Scandinavian languages. They are characterised by a certain “novelty”, illustrated by studies that discuss the quality and requirements of tests and tools for data selection and data handling on one hand, and interrogate the consequences of new education policies for schools, teachers, and sometimes students, on the other. Following on from educational accountability and data use, some of these studies are concerned with the changes to teachers’ work and the teaching profession. The findings of the literature review can indeed be interpreted as a reflection of two long-standing and divergent traditions of governing schools grounded in a simplified understanding of the curriculum – Didaktik dichotomy, as described in the introduction to this paper, and further developed in the next section. Another viable interpretation, which contrasts with the first interpretation, also highlights the identification of the six investigative modes and emphasises a need for more nuanced categories to capture both the great variety of approaches in studies on data use and how these overlap and mix along dimensions other than input-output and curriculum-Didaktik dichotomies (Coburn & Turner, Citation2011; Little, Citation2012; Prøitz et al., Citation2017). The presented reviews on research on data use in education, imply various types of complexity that call for different sets of analytical categories, which will be discussed in the empirical sections of this paper.

However, a general finding of the review studies concerns how teachers are the main focal point in this research. A majority of the studies focus on whether teachers do work with data, drivers and barriers in data use among teachers and what characterises teachers’ work with data. The data use research mostly includes research on teachers’ work to inform stakeholders other than teachers (such as administrators and governance actors) about the use of data and evidence. As such, this research often focuses on teachers’ work as contextual, not in terms of how teachers perceive data use, but as seen from the perspective of the outside observer. The main purpose of this research is often to identify the implementation of data in schools and to determine how efficiently data can be used in schools by teachers for the purpose of identifying drivers and barriers in governing education through data and evidence (Prøitz et al., Citation2017). Pursuing this finding leads to a focus on the role of teachers as a profession but also as perceived by themselves in varied data use contexts as a relevant analytical focal point. By adopting teachers and their relations to their “clients” as its focus, this study broadens the scope of previous studies in the field of data use and recognises teachers as central actors in educational governance.

3. Governance dichotomies and comparing national teaching professions

Theoretically, the input-output dichotomy has had a focal role in comparative educational governance research and has been related to the traditions of didaktik and curriculum. This is here explained through the work on different governance regimes by Wermke and Höstfält (Citation2014), which is itself an example of the discussed dichotomisations. Wermke and Höstfält (Citation2014) suggest two opposing governance regimes for the teaching profession in western school systems (See ). More output-controlled systems open up a greater diversity of service, which means different forms of schooling and instruction. This comes at the price of standardised testing and examinations. In other words, such systems control the products or outputs of education, relatively independently of how they are achieved. In contrast, in input-controlled regimes, resources for schools and teachers as a profession (or the institution) are standardised. These, as well as rather strict syllabi, do not allow for much diversity of teaching and schooling. However, in relation to strict input regulation there has been little control of the teachers throughout their career. Hopmann (Citation2003) puts here forward the categories of “product” and “process” and argues that input regimes of evaluation control the process of instruction, and out regimes, rather control its products.

Table 1. Different governance regimes (c.f. Wermke & Höstfält, Citation2014).

This rationale is often related to the curriculum vs. didaktik paradigm. We assume that this thinking had its starting point in the above-mentioned paper of Hopmann from 2003, on “On the evaluation of curriculum reforms” in Journal of Curriculum Studies. This strand draws on the work of curriculum researchers such as Gundem, Westbury, Künzli and Hopmann himself. These scholars distinguish between what they call first of all German Didaktik traditions (as can also be found in the Northern European countries) and Anglo-American approaches, which have been collected under the term curriculum approaches. These kinds of “constitutional mindsets” (Hopmann, Citation2008) have been defined as: “the well-established, basic social patterns of the understanding of schooling that have sedimented in the respective traditions” (Hopmann, Citation2015, p. 18) on what a teacher is and what they must do (Hopmann, Citation1999), in other words, conditions for teachers’ work in different national contexts. The Didaktik approach is heavily influenced by the work of Johann Friedrich Herbart and his students. Key aspects include the critical importance of the teacher (not in the sense of teacher-centred instruction) and the subject content in instruction. In this tradition, the teacher is responsible for elaborating the intrinsic value of a subject (Bildungsgehalt) for the education of pupils (Künzli, Citation1998; Westbury, Citation2000; Künzli, Citation2000; Westbury, Citation1998). Pedagogical work (meaning here planning, lesson delivery and assessment) revolves around a theory of pedagogical action: the question of the mediation or mediator between theory and practice.

In Didaktik, the autonomy of professional reasoning is crucial. Didaktik is “not centred on the expectation of the school system, but on the expectations associated with the tasks of a teacher working within both the values represented by the concept of Bildung and the framework of a state mandated curriculum” (Westbury, Citation1998, p. 48). This approach is contrasted to the so-called curriculum approach with its roots in Anglo-American education systems, which is influenced by Ralph W. Tyler’s rationale for educational planning and defines the role of teachers and schooling rather differently (Deng & Luke, Citation2008). Westbury (Citation1998, pp. 48–49) describes this approach in the following: “Curriculum is associated with the idea of building systems of public schools in which the work of teachers was explicitly directed by an authoritative agency which as part of a larger programme of a curriculum containing a statement of aims, prescribed content, (in the American case) textbooks, and methods of teaching which teachers are expected to implement”.

Building on this work and in relation how teachers are controlled, it has also been argued that in Didaktik countries, teachers are seen as licensed by the state, which is in turn related to rigid steering of processes or input in public education by state-regulated entrance into the teaching profession. The teacher license (granted on proving one’s ability to follow certain processes) enables teachers to establish autonomous agency with little accountability towards administrators beyond the individual school. Discussing the Finnish schooling context, this kind of governance has found its expression in the term “trust-based governance of the teaching profession” (e.g. Sahlberg, Citation2011). In so-called curriculum countries, teachers are governed by assessment of their efficiency in achieving externally formulated standards of education with their students, i.e. their products (Wermke & Höstfält, Citation2014). The notion of control of the teaching profession leads us further in our discussion of the Didaktik vs. curriculum paradigm and possible issues with its encounter with comparative empirical material concerning national teaching professions. In the next section, we aim to discuss, in particular, the control dimension in relation to different kinds of empirical material.

4. Method

4.1. Sample

We start our discussion of the dichotomy by using the analytical approach of formulating hypotheses. This means that we formulate expected outcomes of analyses concerning whether the presented concept is applicable. We ask whether teachers in countries with Didaktik and curriculum traditions, respectively, report and experience control over their work in paradigm-specific ways. In other words, we formulate assumptions that being a teacher in a country with a particular tradition (= independent variable) has an impact on the reported existence of differing control strategies over teachers’ work (= dependent variable).

Our two hypotheses are:

Teachers from “Didaktik” countries experience less formal appraisal and feedback than their colleagues from “curriculum” input-output governed countries.

Teachers in “curriculum countries” report experiences with more significant consequences (salary decrease/increase, dismissal/promotion) in relation to the quality of their work.

The following continuum illustrates the presented analytical dichotomies, often used to explain the rich variance between different countries (). Following earlier classifications (Tahirsilaj Citation2019; Wermke & Höstfält, Citation2014), we developed a continuum between country groups that represents a more systems-oriented teaching method using a so-called Didaktik understanding, at the one end, and countries building on a so-called curriculum rationale in public education, at the other.

The selection of the strategic sample was based on the foregoing theory driven assumptions that there are: (1) countries with a so-called Didaktik tradition. These are, e.g. German-speaking countries (here exemplified by Austria, Germany) and Nothern Europe (here exemplified by Finland, Norway, Sweden). (2) Countries following an output evaluation in their school systems, also related to educational planning traditions based on a so-called curriculum tradition (Anglo-American countries, here exemplified by USA, England and Ireland). The cases of our strategic sample attended in different studies of the OCED TALIS spectrum as we will describe below.

4.2. The quantitative study

In the quantitative section of this article, we use OECD TALIS data of how international teachers report on their own working situation in relation on formal feedback and appraisal, and qualitative empirical material from two exemplary country cases illuminating the phenomenon of quality work in schooling. TALIS is an international survey that offers an opportunity for teachers and school leaders to have their say in six areas. Learning environment; Appraisal and feedback; Teaching practices and classroom environment; Development and support; School leadership; Self-efficacy and job satisfaction (from the OECD TALIS website).Footnote2 The TALIS findings are representative of over 5 million teachers in 34 countries and economies surveyed in 2008 and 2013. The study’s data and technical details are open access. 2018 a new round of TALIS has been conducted.

We compiled the material employed in this article by extracting the results from similar items from the TALIS study of 2013 (here for all three Nordic countries, England and USA), from the TALIS study of 2008 (here, Austria and Ireland), and finally from a study conducted by the German Union of Education (Gewerkschaft für Erziehung und Wissenschaft) in 2009. In the latter, members of the union responded to a German translation of TALIS 2008 (Demmler & von Saldern, Citation2010). In , we present our sample.

Table 2. Sample sizes and years of the cases in our aggregated sample.

As described earlier, in this study, we focus on the TALIS survey area of appraisal and feedback. This area we use as operationalisation of our concern on how teachers in the different traditions are controlled or report on experienced control. According to the conceptual framework of TALIS 2013, this area examines issues related to: “…some of the key elements of appraisal and feedback systems and explores how teacher appraisal and feedback affects various elements of teachers’ professional lives, including training and professional development, job satisfaction, and compensation” (OECD, Citation2013, p. 30),Footnote3 and as such it provides information about teachers’ views on issues of high relevance to this study on data use in different contexts. As defined by the OECD, teacher appraisal and feedback occur when a teacher’s work is reviewed by the school principal, an external inspector, or the teacher’s colleagues (OECD, Citation2013), while peer appraisal and feedback systems aimed at improving student learning are also considered part of this area. Teacher appraisal and feedback areas of the questionnaire are covered by four main questions which ask the respondents to indicate the extent to which they agree or disagree with a number of items (see below).

In this article, the results of the following questions were used: Concerning the feedback you have received at this school, to what extent has it directly led to a positive change in any of the following? We would now like to ask you about teacher appraisal and feedback in this school more generally. How strongly do you agree or disagree with the following statements about this school? Finally, it must be highlighted that this kind of material presents teachers’ perception of how they actually receive feedback and appraisal (in our understanding, are controlled) and potential consequences of this. Consequently, this material can only be understood as accounts of teachers’ reality in terms of the classic Thomas theorem: “If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences” (Thomas & Thomas, Citation1928, for a longer discussion see Fend, Citation2008).

4.3. The qualitative study

The qualitative material was collected in Germany and in Norway. The countries are interesting to compare more deeply due to more recent education reforms, both come from a traditional Didaktik sphere, and have recently implemented reforms that emphasise stronger output steering. The two country cases provide in-depth qualitative information about national contextual elements related to data and data use as well as how teachers consider these issues at a local level, expressed in semi-structured focus group interviews with a total of 60 teachers (Stewart, Shamdasani, & Rook, Citation2007) collected during the period from 2015 to 2017. The qualitative data material was collected in Germany, at the federal state (Bundesland) of Berlin, and in Norway. In this study, as in other studies, these country cases have been placed under the same overarching governance category, characterised as input, process and Didaktik-oriented, but at the same time the two cases represent different education systems that are organised differently. They are of different size and represent different types of national governance and as such they can be seen as highly relevant for this study of local variance.

Despite these differences, an effort has been made to focus on resemblances and relevant elements of the education system by focusing on external feedback systems (the Berlin school inspectorate and quality profiles and the Norwegian Quality Assessment System and national tests) and how teachers consider local data and data use framed by these systems. The interviews focused on teachers’ experiences with different data-related governance forms. Together, the quantitative and the qualitative data provide a glance into the existence and perceived usage of data as seen through the eyes of teachers in different geographical contexts characterised by different systems of education governance.

5. Results

5.1. A quantitative glance- governance regimes and feedback technologies, evidence from the OECD TALIS study

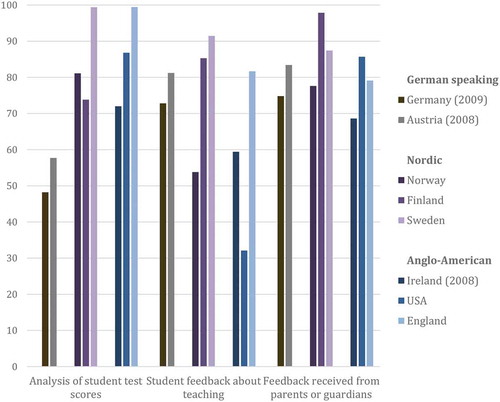

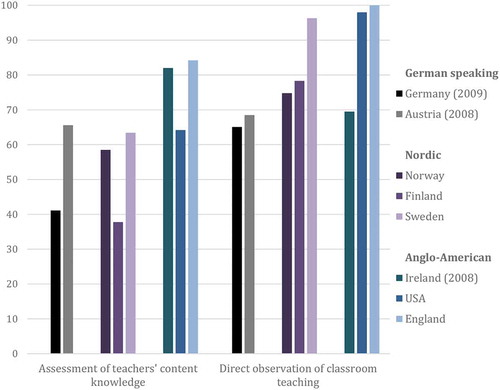

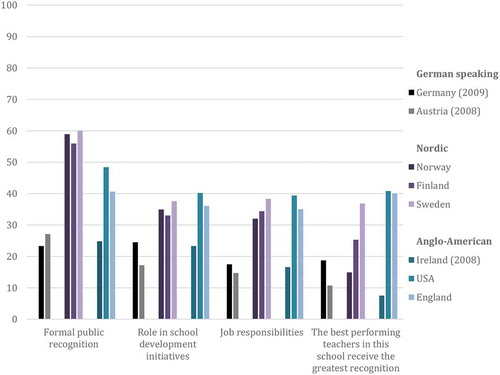

and identify the types of feedback and appraisal teachers report to have experienced in the selected countries, Germany and Austria, Norway, Finland and Sweden and Ireland, the USA and England. presents appraisal in relation to possible output of teachers’ work. presents appraisal of possible input or the process of teachers’ work. According to hypothesis (a), in the German-speaking and also Nordic countries, one would expect less output control, in terms of less formal feedback and appraisal based on, for example, data from standard tests or state examinations or satisfaction of parents, and more process and input controlling, for example, lesson observation and a focus on teachers’ knowledge (e.g. through state examination of teachers).

Figure 2. Teachers’ reports on output-related feedback.

(Percentage of lower secondary education teachers who agree or strongly agree with the following statements about teacher appraisal and feedback systems in their schools).

Figure 3. Teachers’ reports on input or process related feedback.

(Percentage of lower secondary education teachers who agree or strongly agree with the following statements about teacher appraisal and feedback systems in their schools)

Indeed, the diagrams show that analyses of student test results, as well as state examinations or satisfaction of parents, are less important in the German-speaking countries than in Anglo-American countries and that, in Didaktik countries there is a greater focus on process data, such as classroom observation or the competences of teachers.

Nevertheless, around 50% of the German-speaking teachers report that such approaches are relevant in their schools. For the Nordic teachers, both kinds of data are already very important. Both approaches apparently have almost the same significance for teachers in the north as in the Anglo-American countries. For almost 100% of Swedish and English teachers, such results are relevant, which confirms the transformation of the Nordic countries, most evident in the Swedish system, towards a far stronger emphasis on standardised testing and output control technologies ().

Concerning the more input-oriented data on the quality of teachers’ work, shows how the most traditional form is observation of teachers during lessons. At least 60% of all countries’ teachers experienced lesson observations in formal feedback and appraisal processes. “Keep calm, it’s lesson observation”, is certainly a common expression among teachers when it comes to the assessment of how they work. In several of the selected education systems studied here, lesson observation is an important part of teacher education. Thus, teachers might be socialised from the very beginning of their teaching careers to accept that another adult might sit in the classroom observing them. However, shows that the most observed national groups are the Swedish and English teachers. From this, we might infer that perhaps these are not input/output systems, but rather more or less controlled national teaching professions, at least when it comes to known feedback/data technologies. However, if both kinds of data are important, dichotomous categories might lose their discriminatory power.

This leads us to other indicators of what an output of teacher work can be, the satisfaction of students and/or their parents in form of feedback. shows how this kind of client feedback is seen as important in all of the investigated systems. Parents are the most important feedback institution from a teacher’s perspective (in lower secondary schools). In systems built on a strong parental choice through voucher systems, such as in Sweden and parts of England and the USA, the high relevance of these indicators is not surprising. It might be more surprising that shows that the parents’ perspectives on teachers’ work is rated highest in the Didaktik model countries, such as in Finland and Germany. This indicated that the relation of parents’ feedback or satisfaction “data” and teacher work might be a generic part of the teaching profession. Teachers may see themselves not only as state servants, but, perhaps even more, as servants of the civil society.

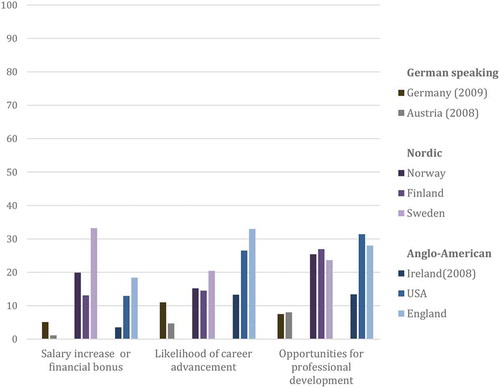

5.2 Teachers’ experiences with sanctions or incentives as result of feedback data

We argue that when we view various kinds of data as communications in a public school system, it may be interesting to assess teachers’ perception of consequences of good practise regarding different indicators. Regarding hypothesis (b), teachers in Didaktik countries are licensed to teach and are quite autonomous from external interference. With reference to the theoretical framework of this study, it might be assumed that teachers in such countries do not experience hard incentives, such as salary increases or opportunities for formal career advancement or professional development opportunities as opposed to education systems with a stronger curriculum approach. However, when looking at and , which show teachers’ experiences with harder and softer incentives, we can see that positive incentives are experienced in all three groups by relatively few teachers. Only in England and Sweden over 30% of teachers did perceive that such opportunities exist, in relation to salary and formal career development, which confirms the previous description of such systems as opening up opportunities for teachers to bargain over working conditions and salaries individually (Helgøy & Homme, Citation2007). Teachers in German-speaking countries (i.e from the Didaktik sphere) see rather few opportunities to be rewarded for doing a good job in this way, and the same is apparently true for Irish teachers (a curriculum country) in the sample.

Figure 4. Teachers’ experiences with soft incentives.

(Percentage of lower secondary education teachers who agree or strongly agree with the following statements about teacher appraisal and feedback systems in their schools).

Figure 5. Teachers’ experiences with hard incentives.

(Percentage of lower secondary education teachers who agree or strongly agree with the following statements about teacher appraisal and feedback systems in their schools).

Regarding soft incentives (), such as formal public recognition and job responsibilities, we see more coherent patterns in the country groups. More common in Nordic countries is public recognition of good work; through their good work teachers in these countries can also shape their working responsibilities and gain responsibility in the school development. Interestingly, a similar number of US teachers report experiencing such soft incentives, which might indicate rather flexible and non-hierarchical structures in public education. More teachers from German-speaking countries and from Ireland, but still far fewer compared with the other groups, see opportunities for soft incentives compared with harder incentives (). In other words, the peer group of teachers, and the principal is a frame of reference, which points to a necessity to investigate intra-professional processes more deeply.

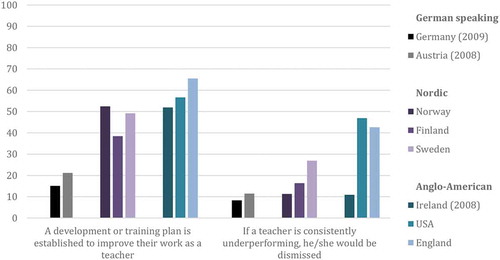

In , we change the perspective, and examine the potential consequences of “bad” work. In both TALIS studies, teachers were asked whether underperforming teachers could be dismissed, or whether they would be forced to undertake particular training. German-speaking, Norwegian, Finnish and Irish teachers should apparently not be scared of dismissal. On the other hand, over 40% of US and English, and about 20% of Swedish teachers see such an unfavourable outcome as a possibility. In all countries, except the German-speaking, at least 40% of teachers see the possibility of being forced to undertake professional development in cases where data informal feedback processes show “underperformance”.

Figure 6. Teachers’ experiences with sanctions.

(Percentage of lower secondary education teachers who agree or strongly agree with the following statements about teacher appraisal and feedback systems in their schools).

We assumed in hypothesis b) that hard consequences (positive and negative) are more common in curriculum countries, and consequences in Didaktik countries are contained more within schools. Here we can see that very few teachers in German-speaking countries report experiencing any consequences at all, either positive or negative. In Nordic countries, there seems to be a public recognition culture in schools. What we characterised here as harder consequences, are reported as more common in curriculum countries, but are also not entirely uncommon in Nordic countries.

6. A qualitative glance – new government technologies and teacher practise in Germany and Norway

After this quantitative perspective, which challenges the assumed existing relations of a Didaktik-curriculum dichotomy and the nature of different national teaching professions, we argue that it might be interesting to gain a deeper insight into feedback and data practices in two of the national contexts. This section aims to discuss the national production and application of education data and evaluation in Germany and Norway, two cases from the Didaktik sphere. The new technologies introduced might enable us to understand the limitation of dichotomous thinking in governance research. When it comes to data, we focus on the following aspects: What data are used, who collects data, what happens with the data, what are the consequences, and what are teachers’ perspectives on the impact of data collection?

6.1. Germany: school inspection and central examinations

The first decade of the new millennium in the German federal states was characterised by significant reform efforts. With the shock over the low ranking of German pupils in international large-scale studies of student performance such as PISA (“PISA shock”) (Ertl, Citation2006) and changes to the higher education system due to the Bologna process (Blömeke, Citation2007), old, very input-related structures were drawn into question, and are now being addressed by different agents (Wermke, Citation2013). School governance and teaching education have been changing. Indeed, changes might differ slightly among the 16 länder (Bundesländer) within the federal German system. However, the trend is the same in all areas, towards more data, and more transparency (Tenorth, Citation2010). Since 2004, in almost all German federal states, there have also been central state examinations at the end of the 10th grade (Mittlerer Schulabschluss) and Abitur, 13th grade, controlled and assessed by teachers. Examination results are not public (Wermke, Citation2013). However, in the following, we focus on the example of school inspection in the state of Berlin and on which data this institution focuses on. Moreover, we present some teachers’ voices concerning how they feel their work is monitored.

Since 2004, as in many other states in Germany, the city-state of Berlin has had a school inspectorate that visits schools in a 5-year cycle, with 8 weeks’ pre-announcement, for 2 days’ duration, drawing on pre-interviews and surveys. The inspectorate aims to control the internal workings of schools, based on qualitative measures, such as the existence of so-called school programmes, i.e. detailed documents concerning the school’s vision, profile and strategies to achieve educational aims and maintain an autonomous and locally anchored school culture. Moreover, all schools need to have a so-called school curriculum, comprising formal processes and content regarding instruction and assessment in the particular school. Moreover, there shall be arenas for parent involvement and teacher cooperation. The aim is to ascertain how teachers’ professional development is organised, and whether teachers have undergone PD activities frequently. The data involved also regard the results of central examinations (graded by the teachers), surveys of teachers, students and parents, and also interviews. Instructional quality is determined by lesson observation (20 min) during the two days of inspection following didactical research (as promoted by Hilbert Meyer or Werner Jank). Aggregative information on the lesson quality of all lessons observed is then graded between A and D, in relation to a mean of the whole state and in relation to a normative perspective, enacted by the trained observer. All indicators as presented in the short profiles of the individual schools as published on the website of the Berlin school administration. There are no rankings, and no hard sanctions for schools. The inspectors see themselves as part of a mostly formative institution, which is also mirrored in the inspection’s name “Schulevaluation” (school evaluation).Footnote4

An important factor is also the group of inspectors going into the schools. A team of inspectors comprises several members (See Senatsverwaltung für Bildung, Jugendund Wissenschaft, Citation2012),Footnote5 all of whom have undergone special training. A research institution, a so-called institute of school quality, develops evaluation instruments. Short inspection summaries are published on the state administration’s website. The schools receive a more detailed report with analyses of possible problems.

The school inspection works in teams. The teams ensure an external evaluation of the school from the perspective of representatives of school management and teaching practitioners, as well as school inspectors and volunteers from non-school sectors. When building the teams, it is important that at least one member is currently active in the type of school which is to be inspected. Furthermore, there shall not be any private or professional relations to the school. (See Senatsverwaltung für Bildung, Jugend und Wissenschaft, Citation2012., own translation)

It is interesting to see how much this inspectional practice follows qualitative peer review and self-reflective practices. Moreover, “volunteers from non-school sectors” are often parents’ representatives. We argue that such evaluation practices may scarcely fit within our given dichotomies. On the one hand, there are many more control techniques in use, but those, in a didactic manner, employ teachers and their peer relations. Even parents are involved. Both the possible products and processes are a focus of such evaluation practices. Moreover, there are no hard sanctions or incentives related to such forms of educational governance.

The inspectorate, alongside other school monitoring techniques has been employed for almost 15 years in the German example, represented by the state of Berlin. It is interesting to ask how teachers experience this feedback or, properly, data culture. In interviews, German teachers report that, in particular, techniques such as state examinations and work with the school curriculum have an impact on their work and are experienced as significant. The school inspection is not mentioned at all in our interviews. Rather, emphasis is placed on work with peers and the importance of parents. Below we present some illustrative and typical voices from different teachers and different schools regarding what kinds of data teachers see as relevant.

Regarding the school curriculum, i.e. the work of teachers with peers, namely peers in the same subject area. The department head, in the German case always a colleague is apparently very relevant.

IrisFootnote6: And then there are also the syllabi developed in our school (school curriculum), which means a tremendous control, for example, in the German subject area, which we both teach. The syllabi expect so many subjects to be taught that it is actually impossible to manage, at least if you have any ambition of being thorough.

Maike: Of course.

Iris: …you are, however, not allowed to say this. Otherwise you get in trouble.

Interviewer: With whom?

Iris: With the head of the subject department.

Interviewer: So, the head of the subject department is an institution of control?

Maike At this school it might differ between different subjects.

(Teachers at the Goethe School)

Simone: […] In chemistry, for which I am subject head, we have now called for subject department meetings, at which we must clarify what is expected in our subject department. That means what is expected and what is also controlled […].

Interviewer: So, you as subject head are the link between teachers and school management?

Linda: Yes, this is true for German, my subject department. If there are any problems, you would go to the department head and deal with the problem within the department. (Teachers at Town Hall School)

Moreover, there is a very obvious parent orientation in the teachers’ reflections. The central examinations apparently relate the work of teachers to, e.g. parental expectations which schools have to meet.

The 10th grade graduation examinations (Mittlerer Schulabschluss, MSA) influence the whole school year for the 10th graders. It is like a sword of Damocles over their heads. The examinations, the examinations, everything is directed toward the examinations. We do everything for the examinations, we train for the examinations, we do not do anything else. (Linda at Town Hall School)

Final examinations! The future! They are panicked, afraid. Parents go to the principal directly. (Sina, Ghandi School)

6.2. Norway: national tests and national examination

For many years, Norway has been governed by social democratic parties, with strong influence on national education policy. Education has been regarded as an essential part of an all-embracing welfare policy, with equality as a guiding principle for reform (Telhaug, Mediås, & Aasen, Citation2006). The method for achieving this has been a high degree of standardisation, public funding and a strong central state, in several ways similar to the German case. In the last two decades, the public sector and education system have been radically and extensively transformed (e.g. Aasen, Citation2007; Aasen et al., Citation2012). At the same time, policies of decentralisation and deregulation have led to the re-distribution of responsibilities in new ways, with municipalities being made more directly responsible for student learning outcomes in compulsory and upper secondary school education (Prøitz, Citation2014). Despite this, overall responsibility for curricula, control systems and evaluation are still primarily national. Central elements in the change are the introduction of a more outcome-oriented education system and systems for assessment and evaluation in combination with a stronger accountability script (Aasen et al., Citation2012; Hatch, Citation2013; Mausethagen, Citation2013; Prøitz, Citation2015; Mølstad & Prøitz, Citation2019). In effect, the Norwegian educational reform of 2006, which reinforced deregulation and pushed policy-making authority downwards in the education system, made municipalities and counties ‘school owners’ (Møller & Skedsmo, Citation2013). Today, the initial ideas of decentralisation, governing exclusively by goals and monitoring results are challenged by policy initiatives to strengthen the control of the central state. This is done by monitoring results and outcomes, more regulations, the definition of activities, the provision of support systems, supplementary documents and guidelines for working with local curricula, learning outcomes and assessment and a system of school inspection (Aasen, Prøitz, & Rye, Citation2015; Aasen et al., Citation2012; Mølstad, Citation2015; Prøitz, Citation2015; Hall, Citation2016)

In the present Norwegian policy context, despite being characterised as low-stakes, schools and municipalities are held accountable for student outcomes to a greater extent than before (Mausethagen, Citation2013; Prøitz, Citation2014). The national quality assessment system (NQAS) launched in 2005 systematises already-existing assessment tools (such as diagnostic tests and final grades) and has over the last 10 years included new inventions such as national testing. The quality assurance system combines information on students’ learning results with data from surveys, international comparative tests, school inspections, and guidelines provided by the government (Allerup et al., Citation2009; Skedsmo, Citation2011). The total body of information is presented on the website Skoleporten.no, which provides the public with limited access to anonymised data, while school owners, leaders and teachers have extended access to the data for monitoring and development purposes.

The national tests are run in September and October each year for fifth and eighth graders, and focus on basic academic skills, numeracy, literacy and English. For Norwegian students at primary school, the national tests are the only-standardised indicators of learning results until their final exams in the 10th grade (Hovdhaugen, Vibe, & Seland, Citation2017). When introduced in 2004, the tests were met with apprehension, but after being paused for improvements and reintroduction in 2007, the tests were met with increasing interest (Aasen et al., Citation2012). Nevertheless, municipalities and teachers still report various challenges and difficulties in using the test results for improving school quality (Hovdhaugen et al., Citation2017; Mausethagen, Prøitz, & Skedsmo, Citation2018a).

The implementation of new assessment policies, such as national testing, implies the introduction of aspects of “evidence-based governing” in a country with long traditions of compulsory schooling, non-competitiveness and egalitarian values (e.g. Telhaug et al., Citation2006). The policy rhetoric, however, highlighted that student performance in national tests was to be used for learning and development purposes on individual and systemic levels, while also containing elements of controlling and monitoring (Skedsmo, Citation2011). The national tests are considered to have a double function, to be used for both control and development purposes (Tveit, Citation2014). This tension is often under-estimated in policy as well as in research, yet remains highly relevant for understanding the practices of teachers’ data use as they unfold locally (Mausethagen et al., Citation2018a).

As a consequence of these recent developments, research on data use in municipalities and schools has identified a new organisation routine in Norwegian educational governance, the so-called “result meetings” between teachers, teachers and school leaders and school leaders and representatives from the administration at the municipality/district level (Mausethagen, Skedsmo, & Prøitz, Citation2016, Prøitz et al., Citation2017). The result meetings represent an arena for discussions and decision-making about further work based on test results, however observations of these meetings show how seldom teachers base their discussions on results from a single test, but rather make use of several knowledge sources in their inferences about a situation (Mausethagen et al., Citation2018a). Although teachers draw upon a range of knowledge sources, the solutions themselves are often short-term and directed towards improving test results. Teachers also use data to confirm their own or their colleagues’ practices rather than using data to challenge the practices employed. Studies also show that school leaders seldom challenge teachers with data but rather employ varied strategies to motivate and support their teachers (Mausethagen, Prøitz, & Skedsmo, Citation2018b). In interviews, teachers express mixed feelings about the national tests in terms of what purpose they might have for their developmental work seen in relation to their own tests or oral assessments.

Per: am thinking that it is more like a tool to help with planning, it does not say… it says very little about our actual work because that can only be seen in other ways.

Interviewer: In what other ways?

Per: That is hard to eh…

Pål: But it is more like when you have been teaching and then make them have a test the next lesson about what you taught them, then you will see ok, have they learned what we have been going through, the goals that we have been working with.

Per: Yes that’s right, now we have been having literary history for several weeks and then we are going to have either an oral assessment about the subject or a little test, yes that’s when you see if they have got what they were supposed to or not…

Pål: If they do poorly then I have done something wrong.

Pål: Yes that is how it is, yes, or that is when I see what students in one way or another I have got through to or not and who I have to be aware of and make some extra follow up on.

(Teachers at Lake school)

When asked about how important the teachers consider the national tests to be compared to the final examination, a general pattern in the interviews is that exams are more important. But a collegial understanding among the teachers as professional peers about how they work aiming for the final exams even though it might not be the publicly accepted or correct way to put it:

Yes, I think so (laughs), I am not sure about how correct it is to say this but our work is aimed towards the final exams during the three year period, that is our final goal and all goals we have in our work plans are directed at that. (Lise at Mountain school)

When asked how they feel about the result meetings with the local authority, teachers consider the control aspect from various perspectives. Some of the teachers regard the meetings as useful for keeping a focus on practise, but also consider this as dependent on how honest and open one is in one’s own reflection and discussions, while others reflect on how the discussion can be manipulated to focus on the positive more than the negative results and how this is a natural behaviour when the “director” is attending. The interview illustrates how teachers share a common understanding of what is expected in meetings with the district administrators and how they can position themselves to meet the expectations of the meeting, but it also displays the tensions at play between meeting these expectations and how honest they can be about “what is really going on”.

Kari: I have been to many meetings on both sides of the table, no, it is a little like a tool that keeps you in line (ris bak speilet) and forces you to take a look at your own practise, what you actually do, it works well if you have an open and honest relation to what is actually going on, but it does not work if it is all about serving the polished version of the story (solskinnshistorie).

Maria: No, no but it is like you say, it is useful for us, we are forced to think through our practise and what we put emphasis on and what we want to emphasise and what we say to them is maybe also a little of what we think they want to hear, but we do get to think it through and discuss it on our own, how we do it, so it is useful.

Espen: But what one says and what one does is not necessary always the same, no but to be honest, I have not been to those meetings, but I think that if the director is there then maybe you do not raise all kinds of issues but you will try to emphasise the positive things and what you have had success with, doesn’t everyone do that?

(Teachers at Forrest school)

The qualitative interview material also displays how relations to parents and the relation between the school and the home of the students are important for teachers in various ways. In particular, this can be seen in how teachers emphasise the parental perspective in discussions about student performance. Further, in result meetings, teachers and school leaders have been found to refer more to their knowledge about students and parents than, for example, to research and information from data and statistics in their interpretation of national test results (Mausethangen et al., 2018b). These qualitative findings from Norway have been supported by a recent survey reporting that teachers emphasise parents’ feedback on school quality as third most important group after students and peers (Mausethagen et al., Citation2018b).

7. Discussion

Encountering the material from the OECD TALIS study, we could observe that dichotomous Didaktik-curriculum categories in relation to how international teaching professions are controlled is challenged. According to hypothesis (a), in the German-speaking and also Nordic countries one could expect less output control, in terms of less formal feedback and appraisal based on, for example, data from standard tests or state examinations, and more process controlling, for example, lesson observation and a focus on teachers’ knowledge. From the TALIS survey, we might infer that perhaps there are not dichotomous systems, but rather more or less controlled national teaching professions, at least when it comes to well-known feedback/data technologies, and indeed from teachers’ reported perspective.

However, if both kinds of data on teacher’s work quality are important, dichotomous categories lose discriminatory power. That would mean that we might not only challenge the Didaktik vs. curriculum paradigm, but also the output-input-governance-regime-concepts. With other words, all these categories' features could be find in most of the Western countries today. Moreover, we assumed in hypothesis b) that hard consequences are more common in curriculum countries, and consequences in Didaktik countries are more contained within schools. Here we can see that very few teachers in German-speaking countries report experiences of any consequences at all, either positive or negative. In Nordic countries, there seems to be a public recognition culture in schools. This would mean that there are other mindsets prevalent in the Nordic countries than in the German ones, although both are within the Didaktik sphere (e.g. more the first group might have a more cooperative mindset than the second one). Finally, what we characterised here as harder consequences, are reported as more common in curriculum countries, but are apparently also not entirely uncommon in Nordic countries.

To challenge this tested rationale even more, in our qualitative section, the Didaktik countries – Germany and Norway – illustrate both the existence of an elaborated audit culture, but with no hard consequences related to success or failure. When examining the example of the Berlin school inspection (Schulevaluation), it appears to us that there is an ambition for thick data to be collected, because the evaluations are rather formative in nature, and no significant consequences are involved. There is a focus on collegiality and cooperation due to the focus on work processes related to school curriculum, and school programme. Much of the information is based on the existence of documents and workflows, but also on parental feedback and performance in state examinations. While the Norwegian example of national tests as a central part of the national quality assurance system also emphasises the use of a variety of data and information, the interview data illustrate how the formal test data are considered potential tools for discussion and reflection about practise. This is albeit not necessarily held in very high esteem as tools for everyday teaching and learning development processes. In both practices, teachers are involved, and are expected to reflect on their practise together with their peers as part of the evaluation. There is significant control, but teachers have a defined role in the systems, which challenges the practicability of the presented dichotomous thinking, because it overemphasises state steering in educational governance and governing.

We may, consequently, conclude that the countries used in order to relate the Didaktik-curriculum categories to input or output focussed governance tradition provide a more blurred picture today (20 years after the development of the Curriculum and/or Didaktik research programme (Hopmann, Citation2015)). Governance regimes dichotomies also contain the risk of locking up comparative analyses, even if the complexity reduction they entail enables international comparisons in a sophisticated manner. The pro and cons, opportunities and limitations should perhaps be discussed more thoroughly in the future. However, in complement to in particular a curriculum and Didaktik dichotomy, we propose here considering more deeply the role of peers, the role of teachers as administrators and a necessary embedding of the teaching profession in between a state and its administration and civil society. In the following, we present some tentative ideas.

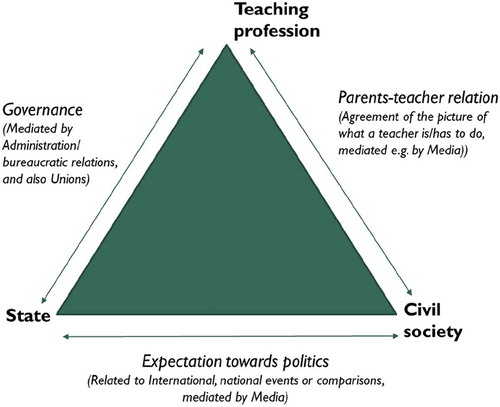

When we look at our quantitative material from TALIS, we might say that teachers report an apparent significance of parent feedback. Parents must be satisfied, or at least their feedback must be taken into consideration. These evaluations, however, may not be explicit at all. From this perspective, “Bildung” as an aim of schooling then becomes very country-specific since it is part of nation-specific civil societies and their expectations to schooling. Trust in the teaching profession, as put forward by comparative research (Mølstad, Citation2015; Sahlberg, Citation2011), is then not only a state–teacher relationship, but also a civil society–teacher relationship. This also finds expression in the discussion of the status of the teaching profession. Professional status means then the prestige of a profession in the society, building on the expectations and beliefs of the latter. The relation between the teaching profession, the civil society and the state is mediated by different stakeholders, such as interest groups or unions, as well as media. Even state and civil society are connected. State policy, e.g. in education is also related to public expectation (at least in democratic states). We show this in .

From such a perspective we might argue that, for example, the high status of Finnish teachers is also built on their close relations to parents and their values; and this strong foundation correlates with a traditionally state regulated teacher role and teacher education, which frame teachers as civil servants legitimised by state authority (Simola, Citation2005). For Swedish teachers today, first, with the radical decentralisation and marketisation since the beginning of the 1990s the traditionally strong framing of teachers by the state disappeared; and this was followed by a high complexity of possible teacher roles and identity (Wermke & Forsberg, Citation2017; Persson, Citation2008). This development, in the same token, accompanied by a scandalisation of the conditions of schooling and the teaching profession by the media, might have resulted in a virtual teacher-civil society contract breaking up (cf. Zaremba, Citation2011). For the German and the Norwegian case, we can state that central state authorities still define what a teacher is and what is expected. Even if, in particular in Germany, the relation of the civil society to its teachers is very ambivalent (Blömeke, Citation2005), teachers are self-evidently part of the state administration and secured by this role (Terhart, Citation2011).

Norwegian and German teachers have both a very explicit corporate identity as civil servants – authorised by the state – which means state administrators serving the citizens of the state, but representing the state. We take the German teaching profession as a further example, because of its very telling terminology in German, even if the structures bear a great resemblance in Norway. German teachers are mostly tenured civil servants (Beamte), with a particular relation to the state which is the teachers’ employer (Dienstherr, directly translated as master of servants). This implies that the state regulates, examines and certifies teacher education (Staatsexamen, directly translated as teacher examination taken by the state). In addition, the state as the employer, assigns newly graduated teachers to the individual schools. Teacher candidates in schools are called Referendare, which means civil servants (Beamte) for higher administrational tasks in training. Even judges, prosecutors, state administrators with leadership, strategy and planning functions undergo a Referendiariat, and consequently, administratively, the German teaching profession is seen as equivalent to prosecutors, judges or higher state administrators, who also are examined by a state examination and are also positioned in a hierarchical system comprised of different councillor positions (Räte). Teachers are not allowed to simply move between schools according to their own whims (Terhart, Citation2011). However, the teaching profession enjoys an extended institutional autonomy through their civil service status, which protects the profession from outside interference such as that imposed by parental or municipality stakeholder expectations (Schwänke, Citation1988; Weniger, Citation2000/1952). The profession’s bureaucratic structures take on full responsibility for controlling its members, resulting in the constraint of the individual teacher and school practice.

We argue in favour of seeing and investigating teachers as administrators. It is part of their state-assigned profession, to administer the results of their work on behalf of the state in relation to the expectations of the civil society, the parents. However, this administrative work might not be hierarchical, but rather egalitarian. In the words of Lortie (Citation2002/1975), the organisation of schools follows an autonomy-parity principle. Teachers are autonomous and equal, which is why the possibilities for sanctions are limited. In order to strengthen our argument even more, the role of the state in relation to its professions has also been described in similar terms elsewhere. Svensson (Citation2008), distinguish between an Anglo-American and a continental approach to professionalisation. In the latter, professions evolve in relation to state building, having been entrusted by the state with the above-mentioned risk of handling tasks. Consequently, their autonomy is defined by the state, and professionals act responsibly towards their tasks in a given framework. It is the state that judges whether the profession acts according to the defined expectations. This first approach developed in a market place, and these professionals are autonomous, in a classical sense, in terms of having more freedom of choice concerning their professional means. Consequently, what we, in a continental European context, would call professionals are, in an American context government officials, or ‘bureaucrats’ in Lipsky’s words. This is why Lipsky’s (Citation2010/1980) considerations on ‘street level bureaucracy’ were such a success in European research on professions. What he describes for bureaucrats in the USA is also productive for the conceptualisation of professions in continental Europe. For Lipsky, teachers are street-level bureaucrats, while in continental Europe they are regarded as semi-professionals, having a certain discretion, related to a certain status. However, the Anglo-American professionals are related to state and society by their accountability. Departing from another classic, Weber, we might argue further that an Anglo-American culture mirrors Protestant church hierarchies and the logic of capitalist production, whereas the continental European culture mirrors the concepts of Beruf (German for vocation), which is similar to the mediaeval guilds and their egalitarian but still highly structured practices. It is also possible to see a tradition of a European cameralistic accountancy and business-management accountancy regarding the financing and processing of civil services.Footnote7 All those concept, also are related to nation-specific civil societies.

Consequently, in order to understand differences between systems of governance in education, we suggest that we should speak more about curriculum administration and teachers as administrators of curriculum as put forward by Hopmann and Haft (Citation1990), on the one hand and as servants to the civil society, on the other. Even more provocatively, we should re-read and re-visit Lortie, Lipsky, or perhaps Weber alongside Herbart, Klafki, Taylor, or Tyler in order to understand different national teaching professions and how they are governed.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Wieland Wermke

Wieland Wermke is associate professor at Stockholm University, Department of Special Education. His research focusses on teachers’ work and teacher professionalism from a comparative perspective. Recently, he has lead a research project on teacher autonomy in Sweden, Finland, Germany and Ireland.

Tine S. Prøitz

Tine S. Prøitz is professor at the University of South-Eastern Norway, Department of Education Science. Her research interests lies within the fields of education policy, education reform and comparative education. Prøitz is currently the project manager of the ongoing research project Tracing Learning outcomes in Policy and Practice (LOaPP).

Notes

1. The German and Swedish term Didaktik itself is an untranslatable concept. “The most obvious translation of Didaktik, didactics is generally avoided in Anglo–Saxon educational contexts, and refers to practical and methodological problems of mediation and does not aim at being an independent discipline, let alone a scientific or research programme (Gundem & Hopmann, Citation1998).

3. OECD 2013, Teaching and Learning International Survey TALIS 2013 Conceptual Framework

5. ibid.

6. Names of teachers and schools have been anonymised.

7. We want to thank one of our reviewers for this sophisticated and thought-provocing inspiration that we shall re-consider Weber on the one hand, and the continental European, tradition of “Beruf” and cameralistic accountancy.

References

- Aasen, P. (2007). Equity in educational policy. A norwegian perspective. In I. Teese, L. Richard Stephen, & M. Duru-Bellat (Eds.), International studies in educational inequality, theory and policy (pp. 460–475). Dordrecht: Springer.

- Aasen, P., Møller, J., Rye, E., Ottesen, E., Prøitz, T. S., & Hertzberg, F. (2012). Kunnskapsløftet som styringsreform-et løft eller et løfte? Forvaltningsnivåenes og institusjonenes rolle i implementeringen av reformen. [The knowledge promotion education reform.]. Oslo: NIFU.

- Aasen, P., Prøitz, T., & Rye, E. (2015). Nasjonal læreplan som utdanningspolitisk dokument. [National curriculum as education policy document]. Norsk Pedagogisk Tidsskrift, 99(06), 417–433.

- Allerup, P., Andersen, H. L., Dolin, J., Korp, H., Larsen, M. S., Nordenbo, S. E., … Østergaard, S. (2009). Pædagogisk brug af test. Et systematisk review. Copenhagen: Danmarks Pædagogiske Universitetsforlag.

- Altrichter, H., & Maag Merki, K. (Eds.). (2016). Handbuch Neue Steuerung im Schulsystem (2nd ed.). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Ball, S. J. (2008). New philanthropy, new networks and new governance in education. Political Studies, 56(4), 747–765.

- Blömeke, S. (2005). Das Lehrerbild in den Printmedien. Inhaltsanalyse von “Der Spiegel” und “Focus” Berichten. [The “teacher” in print media. A Content analysis in the journals “Der Spiegel” and “Focus” since 1990].. Die Deutsche Schule, 97(1), 24–39.

- Blömeke, S. (2007). The impact of global tendencies on the German teacher education system. In M. Tatto (Ed.), Reforming teaching globally (pp. 55–74). Oxford: Symposium Books.

- Bondorf, N. (2012). Profession und Kooperation“: Eine Verhältnisbestimmung am Beispiel der Lehrerkooperation” [Profession and cooperation: Discussing a relation with the example of teacher cooperation]. Frankfurt, Main: Springer.

- Coburn, C. E., & Turner, E. O. (2011). Research on data use: A framework and analysis. Measurement: Interdisciplinary Research & Perspective, 9(4), 173–206.

- Demmer, M., & von Saldern, M. (2010). “Helden des Alltags”. Erste Ergebnisse der Schulleitungs- und Lehrkräftebefragung (TALIS) in Deutschland [“Weekday heroes”. First results of the principal and teacher survey (TALIS) in Germany]. Münster: Waxmann.

- Deng, Z., & Luke, A. (2008). Subject matter: Defining and theorizing school subjects. In F. M. Connelly, M. F. He, & J. Phillion (Eds.), The sage handbook of curriculum and instruction (pp. 66–87). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Easley, J., II, & Tulowitzki, P. (Eds.). (2016). Educational accountability: International perspectives on challenges and possibilities for school leadership. London: Routledge.

- Ertl, H. (2006). Educational standards and the changing discourse on education: The reception and consequences of the PISA study in Germany. Oxford Review of Education, 32(5), 619–634.

- Fend, H. (2008). Schule gestalten. Systemsteuerung, Schulentwicklung und Unterrichtsqualität. [Organising schooling. Governance, school development and instructional quality]. Wiesbaden: Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Gough, D., Tripney, J., Kenny, C., & Buk-Berge, E. (2011). Evidence informed policymaking in education in Europe: EIPEE final project report.

- Gundem, B. B., & Hopmann, S. (1998b). Didaktik meets curriculum. In B. B. Gundem & S. Hopmann (Eds.), Didaktik and/or curriculum (pp. 1–8). New York: Lang.

- Gunter, H. M., Grimaldi, E., Hall, D., & Serpieri, R. (Eds.). (2016). New public management and the reform of education: European lessons for policy and practice. Routledge

- Hall, J. (2016). State school inspection - the Norwegian example ( Series of dissertations submitted to the Faculty of Education). University of Oslo No. 259.

- Hatch, T. (2013). Beneath the surface of accountability: Answerability, responsibility and capacity-building in recent education reforms in Norway. Journal of Educational Change, 14(2), 113–138.

- Helgøy, I., & Homme, A. (2007). Towards a new professionalism in school? A comparative study of teacher autonomy in Norway and Sweden. European Educational Research Journal, 6(3), 4.

- Hopmann, S., & Haft, H. (1990). Comparative curriculum administration history. Concepts and methods. In S. Hopmann & H. Haft (Eds.), Case studies in curriculum administration history (pp. 1–10). London, New York: Tayler & Francis.

- Hopmann, S. (1999). The curriculum as standard of public education. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 18, 89–105. doi:10.1023/A:1005139405296

- Hopmann, S. (2003). On the evaluation of curriculum reforms. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 35(4), 459–478.

- Hopmann, S. (2015). ‘didaktik meets curriculum’ revisited: historical encounters, systematic experience, empirical limits. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 2015(1), 27007. doi:10.3402/nstep.v1.27007

- Hopmann, S. T. (2008). No child, no school, no state left behind: Schooling in the age of accountability. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 40(4), 417–456.

- Hovdhaugen, E., Vibe, N., & Seland, I. (2017). National test results: Representation and misrepresentation. Challenges for municipal and local school administration in Norway. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 3(1), 95–105.

- Karseth, B., & Sivesind, K. (2010). Conceptualising curriculum knowledge within and beyond the national context. European Journal of Education, 45(1), 103–120.

- Künzli, R. (1998). The common frame and the places of didaktik. In B. B. Gundem & S. Hopmann (Eds (Eds), Didaktik and/or curriculum (pp. pp. 29–46). New York: Lang.

- Künzli, R. (2000). German Didaktik: Models of re-presentation, of intercourse, and of experience. In I. Westbury, S. Hopmann, & K. Riquarts (Eds.), Teaching as a reflective practice: What might Didaktik teach curriculum? (pp. 41–53). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Lipsky, M. (2010/1980). Street level bureaucracy. Dilemmas of the individual in public services (2nd ed.). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Little, J. W. (2006). Professional community and professional development in the learning-centered school. (pp. 22–46). Washington, D.C.: National Education Association.

- Lortie, D. C. (2002/1975). Schoolteacher - A sociological study (2nd ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Lundgren, U. P. (2006). Political governing and curriculum change–from active to reactive curriculum reforms the need for a reorientation of curriculum theory. Studies in Educational Policy and Educational Philosophy, (2006(1), 26853.

- Mausethagen, S. (2013). Reshaping teacher professionalism. An analysis of how teachers construct and negotiate professionalism under increasing accountability. Oslo, Norway: University College of Oslo

- Mausethagen, S., Prøitz, T., & Skedsmo, G. (2018a). Teachers’ use of knowledge sources in ‘result meetings’: Thin data and thick data use. Teachers and Teaching, 1–13.

- Mausethagen, S., Prøitz, T. S., & Skedsmo, G. (2018b). Elevresultater mellom kontroll og utvikling [Student performance data between control and development]. Oslo: Fagbokforlaget.

- Mausethagen, S., Skedsmo, G., & Prøitz, T. S. (2016). Ansvarliggjøring og nye organisasjonsrutiner i skolen–rom for læring. Nordiske Organisasjonsstudier, 1, 79–97.

- Møller, J., & Skedsmo, G. (2013). Modernising education: New public management reform in the Norwegian education system. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 45(4), 336–353.

- Mølstad, C. E. (2015). State-based curriculum-making: approaches to local curriculum work in Norway and Finland. Journal Of Curriculum Studies, 47(4), 441–461.

- Mølstad, C. E., & Prøitz, T. S. (2019). Teacher-chameleons: the glue in the alignment of teacher practices and learning in policy. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 51(3), 403–419.

- OECD (2013). Teaching and Learning International Survey TALIS 2013: Conceptual Framework. Final. OECD Publishing

- Ozga, J. (2009). Governing education through data in England: From regulation to self‐evaluation. Journal of Education Policy, 24(2), 149–162.

- Persson, S. (2008). Läraryrkets uppkomst och förändring: En sociologisk studie av lärares villkor, organisering och yrkesprojekt inom den grundläggande utbildningen i Sverige ca. 1800–2000 [The teaching profession’s emergence and change: A sociological study of teachers’ conditions, organisation and professional project in the compulsory education in Sweden ca. 1800–2000]. Stockholm: Arbetslivsinstitutet.

- Prøitz, T. S. (2014). Conceptualisations of learning outcomes—An explorative study of policymakers, teachers and scholars. Series of Dissertations Faculty of Educational Sciences, (194).

- Prøitz, T. S. (2015). Learning outcomes as a key concept in policy documents throughout policy changes. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 59(3), 275–296.

- Prøitz, T. S., Mausethagen, S., & Skedsmo, G. (2017). Investigative modes in research on data use in education. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 3(1), 42–55.

- Rieper, O., & Hansen, H. F. (2007). Metodedebatten om evidens. København: AKF Forlaget.

- Sahlberg, P. (2011). Finnish lessons. What can the world learn from educational change in Finland? New York: Teachers College Press.

- Schwänke, U. (1988). Der Beruf des Lehrers. Professionalisierung und Autonomie im historischenn Prozess [The profession of the teacher. Professionalisation and autonomy as historical process]. Weinheim: Juventa.

- Senatsverwaltung für Bildung, Jugend und Wissenschaft (2012). Handbuch für Schulinspektion [Handbook for school inspection]. Berlin: Senatsverwaltung.

- Simola, H. (2005). The Finnish miracle of PISA: Historical and sociological remarks on teaching and teacher education. Comparative Education, 41(4), 455–470.

- Simola, H., Rinne, R., Varjo, J., & Kauko, J. (2013). The paradox of the education race: how to win the ranking game by sailing to headwind. Journal of Education Policy, 28(5), 612–633.