ABSTRACT

Teacher education (TE) plays a pivotal role in fostering student teachers’ teacher identity development, and furthermore, their readiness and motivation for continuous professional development. In this article, we explore the differences in student teachers’ teacher identity during TE. For this purpose, we investigated personal practical theories) of beginning and advanced primary school student teachers. Personal practical theories (PPTs) are defined as pedagogical beliefs that guide classroom actions. We found out that there are gradual qualitative differences in student teacher identities as TE proceeds. However, the results indicate that the overall differences in teacher identities are minor during TE. On the basis of the results, we consider the ways TE may promote student teachers’ continuing professional development

Introduction

Today’s continually changing world requires teaching pedagogies that aim to foster students’ activity, self-regulation and collaborative skills, and thus, teachers are no longer seen as a subject expert but rather as learning process experts (Vermunt, Vrikki, Warwick, & Mercer, Citation2017). These new ways of learning (e.g. problem-based learning and inquiry-based learning) require that teachers continually engage in professional development and are motivated to learn. The ways in which teachers approach professional development is dependent on their beliefs and values about good teaching and, according to Vermunt et al. (Citation2017), high-quality teacher learning is equal to identity development.

When student teachers initially enter a TE programme, their developing teacher identities already possess many beliefs concerning the work of a teacher based on their experiences as students (Levin, He, & Allen, Citation2013). Actually, beliefs about teaching and learning play a pivotal role in TE, since they form the basis for meaning making and decision-making during student teachers’ studies (Chong & Low, Citation2009; Nespor, Citation1987). The role of TE is essential in the development of student teachers’ teacher identity, and thus it is crucial to ascertain the nature of the beliefs held by student teachers during their TE training and how such beliefs change (see Izadinia, Citation2013). This article investigates beginning and advanced primary school student teachers’ teacher identity in the context of one Finnish TE programme. The aim of this study is to explore the differences in student teachers’ teacher identities in different phases of TE and thus ascertain ways to support the professional development of student teachers during their TE. For this purpose, we employ the personal practical theories (PPTs) of student teachers. PPTs are defined as pedagogical beliefs that guide classroom actions. The data consist of two independent data sets from student teachers in primary TE. The first data set of this cross-sectional study was collected from beginning student teachers (Stenberg, Karlsson, Pitkaniemi, & Maaranen, Citation2014), while the second data set was collected from advanced student teachers (Maaranen, Pitkäniemi, Stenberg, & Karlsson, Citation2016).

Teacher identity

Teacher identity has been a subject of increasing interest in TE (see, e.g. Atkinson, Citation2004; Rodgers & Scott, Citation2008). According to Avraamidou (Citation2014), the concept of identity offers a comprehensive construct for understanding teachers’ development and learning, which goes beyond skills and knowledge; thus, the concept offers an ontological approach to learning. Teacher identity offers a fruitful pathway because it creates the basis for teachers to construct their ideas about their professionality and its place in society, and hence, enhance their professional development (see Sachs, Citation2005). In addition, the handling of new information during TE is based on student teachers’ visions of good teaching, which are related to student teachers themselves, that is, to their developing teacher identities (Horn, Nolen, Ward, & Campbel, Citation2008). Furthermore, teacher identity is a strong feature in teachers’ levels of motivation, satisfaction and commitment to their work (Day, Kington, Stobart, & Sammons, Citation2006).

In educational studies, teacher identity has been approached from various viewpoints ranging from cognitive to sociological perspectives (Cherrington, Citation2017), and from narratives, metaphors and discourses to contextual standpoints (Beauchamp & Thomas, Citation2009). According to Avraamidou (Citation2014), despite a wide range of conceptualisations, there seems to be general agreement that teacher identity is socially constructed; it is dynamic and continually formed, a complex and multidimensional conception that involves interrelated sub-identities (see also Izadinia, Citation2013). This study is inspired by dialogical self-theory, which illustrates the complexity of identity construction (Akkerman & Meijer, Citation2011). A teacher’s identity is seen as an ongoing process where, through dialogues within various contexts and relationship, different teacher identity positions have their own voices and aims (cf. Arvaja Citation2015; Stenberg et al., Citation2014). This is further explained as follows.

Teacher identity positions

Dialogical self-theory is based on the work of Hermans, Kempen, and Van Loon (Citation1992). According to Arvaja (Citation2015), from this standpoint the self is understood as having multiple I-positions, which are used in expressing one’s self. The positions are linked to an individual’s experiences and social relationships (141). Each I-position has its own voice and is driven by its own intentions (Akkerman & Van Eijck, Citation2013). For example, a teacher may want to nurture and take care of the pupils’ well-being while at the same time organise the contents of the curricula in strict pedagogical fashion to ensure effective learning. Thus, teacher identity consists of different voices, wherein a fairly autonomous I-position shifts from one context to the next. It should be noted that I-positions do not have to be harmonious, but may instead be contradictory (cf. Akkerman & Van Eijck, Citation2013; Hong, Greene, & Lowery, Citation2017).

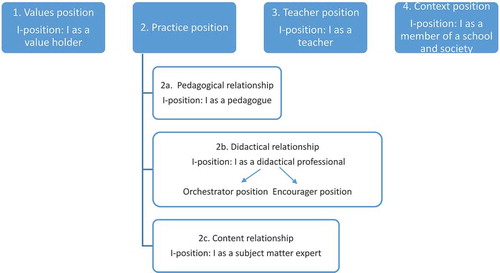

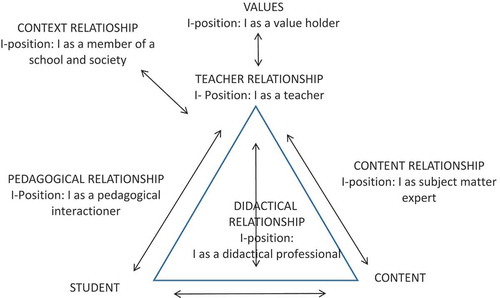

Teacher identity positions in a didactical triangle

This study examines the I-positions of teacher identity with the help of Herbat’s didactic triangle and its interrelationships (Kansanen & Meri, Citation1999). The core elements of the didactic triangle, namely teachers, students and the content, create three dialogical relationships between teachers and students, between students and the content, and between teachers and the content (Zierer, Citation2015). The pedagogical relationship is the intentional, impermanent and interactive relationship between teacher and student; teachers aim to bring out the best in students by encouraging and appreciating them, while seeing their possibilities for success and seeking to foster their growth (Toom, Citation2006). Content relationship refers to the curriculum’s subjects, to teachers’ expertise in the subject matter (Kuusisto & Tirri, Citation2014) and to all other content included in teaching (Kansanen, Citation2003). The didactical relationship is at the core of teaching work; it is the relationship of teachers with the studying and learning processes of students. The aim of teaching is to create an environment that promotes learning, for example by choosing adequate methods (Zierer, Citation2015). In addition to these relationships, teachers also have their own preconceived expectations, for instance when considering the elements and qualities that make for a good teacher or the preconditions for coping with one’s work. Furthermore, there is also a relationship between teachers and broader essential issues, which has to do with values concerning the profession and questions about the ultimate purpose of teaching. Lastly, teaching is always context bound and teachers are part of a broader environment: the school and surrounding society. (Stenberg et al., Citation2014.) These relationships are all pivotal to teaching work, and teacher identity may be considered as the various I-positions from which teachers interact with them: I as a pedagogue, I as a didactical professional, I as a subject matter expert, I as a teacher, I as a member of a school and I as a member of society. This approach to teacher identity is fruitful particularly when pondering the multidimensional and complex work of a teacher.

Teacher identity I-positions and personal practical theories (ppts)

The I-positions of teacher identity may be explored with the help of a teacher’s personal practical theories (PPTs) about teaching. PPTs are defined as pedagogical beliefs (He & Levin, Citation2008), which strongly affect teaching (see also Chant, Citation2002). Teachers use PPTs as the basis for planning, engaging with and reflecting on their teaching (He & Levin, Citation2008); beliefs thus act as filters through which teachers view their work and make pedagogical choices (Chant, Citation2002; Fairbanks et al., Citation2010). The foundation of PPTs derive from a teacher’s personal and professional experiences (Lamote & Engels, Citation2010; Levin & He, Citation2008), and hence, PPTs are related to the development of teacher identity. In other words, teacher identity is based on the beliefs that teachers have about being a teacher and teaching, and these beliefs are formed and reformed through experiences (Chong & Low, Citation2009).

In sum, in this study we define teacher identity as an assembly of I-positions in relation to the essential relationships in teacher’s work. These I-positions may be investigated with the help of pedagogical beliefs (PPTs) that originate teacher’s personal and professional experiences.

Context of the research

This research was conducted at the University of Helsinki’s Department of Teacher Education, in Finland. TE has a nationally shared framework, which guides the TE curriculum in all universities and provides the content for TE. This guarantees a high-quality education for all teachers in the country (for more on this topic, see Niemi, Toom, & Kallioniemi, Citation2016). TE in Finland is research based (Toom et al., Citation2010), which means that all the courses are integrated with research. However, the aim is not to educate researchers, but instead autonomous and reflective teachers who are capable of using research in their teaching and who can be defined as pedagogically engaged teachers. Research-based TE also requires that student teachers produce their own research in the form of bachelor’s and master’s degree theses. Future teachers should be able to base their pedagogical decision-making on a strong theoretical foundation and reflect on their work as teachers. Four characteristics that define Finnish TE are as follows: 1) the study programme is structured around a systematic analysis of education; 2) all teaching is based on research; 3) activities are organised in such a way that students can practise argumentation, decision-making and justifying their decisions while investigating and solving pedagogical problems; 4) students learn academic research skills (Toom et al., Citation2010). Primary school TE is realised in a very similar way in all of the eight universities offering it. There are some emphasis differences, but the national guidelines as well as legislation concerning teacher’s qualification steers the programmes very strongly The studying is somewhat flexible in the sense that students do not necessarily have to follow a determined study path precisely, if they wish to take more courses per year than what is planned in the curriculum. Previous studies are also taken into account, which provides them a faster route to graduation. The yearly intake of primary school teacher students is 120 in the University of Helsinki and the students who are accepted to the primary teacher programme have been accepted directly to both, BA and MA degree programmes. A teacher’s qualification in Finland is achieved only with a MA degree. The study path of primary teachers at the University of X is illustrated in .

Methods and data

The research questions of the study are as follows:

What teacher identity I-positions are reflected in the beginning and advanced primary student teachers’ PPTs?

What differences are embodied in the beginning and advanced primary student teachers’ PPTs?

The data used for this study consisted of two separate data sets: student teachers’ PPTs collected in the same manner from two separate groups of student teachers in primary TE. The data for this study were collected from beginning and advanced students because it was connected to a course assignment. The assignment’s purpose was to promote student teacher reflection on their beliefs during TE.

All primary TE student teachers participate in the two compulsory courses, the first of which is called General Didactics (the very first course that students take when entering the TE programme) and the second one called Pedagogical Knowing and the Construction of Practical Theory. The students take the second course as part of their master’s degree studies (i.e. graduate studies), which may be done at different times due to the different paces at which students study and their previous background studies. Still, the course is taken as a final stage of the studies.

The assignment was the same for the student teachers in two courses: they were asked to write down their beliefs, i.e. PPTs, indicating what is important to them in teaching and in schoolwork. In addition, they were asked to provide an example demonstrating how their beliefs might work in practice. For example, one student teacher stated, “I want the students to enjoy school” and the example given in support of this belief in action was “team spirit in the classroom is positive and enthusiastic and the teacher encourages students”. The student teachers provided four to ten beliefs. The assignment was inspired by a study done in the USA by Levin and He (Citation2008), where the content and sources of student teachers’ practical theories were investigated.

The first data set consisted of 442 PPTs from 71 first-year student teachers who took the General Didactics course in autumn of 2010. The student teachers submitted their PPTs along with real-life experiences using a web-based survey form.

The second data set consisted of 636 PPTs from 84 student teachers who took a master’s level course called the Pedagogical Knowing and the Construction of Personal Practical Theory in 2011. This was the second time during their studies that the student teachers wrote down their PPTs. It should be noted that these two writing exercises were independent of each other, and the student teachers did not reflect on their initial PPTs before writing down their PPTs for the second time. The respondents were master’s level student teachers between their 2nd and 5th years of study, because in the Finnish TE system it is possible to speed up the studying. Also some students have background studies, which makes it possible for them to advance faster. Of the respondents 10 were 2nd year, 19 3rd year, 36 4th year and 19 5th year students, and on average they were in their 4th year of study, and thus each had practicum experience at that point in their studies. The data were collected via an e-survey.

The first author was an outside researcher who had no contact with the participants, while the second author was a teacher educator in several of the study groups where the assignment was given. The assignment was not evaluated nor did it have an effect on the course grade received by the student teachers. Informed consent was obtained from all research participants and the study followed the ethical guidelines of the University of Helsinki and Finnish National Board on Research Integrity (TENK).

Data analysis

The qualitative research data was analysed by deductive content analysis, wherein data was coded according to a categorisation matrix () originating from the salient relationships in a teacher’s work (see ; Stenberg et al., Citation2014; Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2007).

Figure 3. The I-position categories based on the relationships in the extended didactic triangle (see ; cf. Stenberg et al., Citation2014)

Figure 1. Teacher identity relationships with I-positions in the extended didactic triangle from a teacher’s standpoint (cf. Stenberg et al., Citation2014)

Each belief expressed in the student teachers’ PPTs was coded using the relationships in the extended didactic triangle. If there was uncertainty about a particular belief, a real-life example was taken into account to guarantee the right position category. The analysed categories were as follows. Exemplars have been added to each category ().

Table 1. The categories based on the relationships in the extended didactic triangle (see ).

Results of the study

The first research question of the study was as follows: What teacher identity I-positions are reflected in the beginning and advanced primary student teachers’ PPTs?

The first data set showed that when student teachers began their TE, the majority of their teacher identity I-positions concerned didactical issues, i.e. how to promote pupils’ studying and learning processes. It additionally revealed that student teachers’ identities as teachers are strongly linked to the moral nature of teaching. The results indicate that more than a third of their beliefs concerned matters related both values and the pedagogical interaction between pupils and teachers. Beliefs connected to content positions were least represented in the beginning student teachers: subject matters and other content taught in schools received only minor emphasis at the beginning of the TE programme. Parallel to the content positions of student teachers, beliefs related to teaching and contextual issues about school and society were not strongly represented in the teacher identities of beginning student teachers. (cf. Stenberg et al., Citation2014.)

The second data set revealed that advanced student teachers focus quite strongly on moral issues in the middle of their TE. Altogether, 43.55% of their beliefs were connected to both values and the pedagogical interaction between teachers and students. Didactical matters were also emphasised: almost a third (28.77%) of their beliefs were related to successfully managing their identity positions, namely, how to organise the teaching-studying-learning process. One-tenth (10.06%) of expressed beliefs were linked to teachers themselves, while the context position was represented in 5.34% of student teachers’ beliefs. The content position was in fact mentioned the least; 3,30% of beliefs had to do with issues related to subject matter and other content.

The second research question was as follows: What qualitative differences are embodied in the beginning and advanced primary student teachers’ PPTs? The results revealed that with respect to values positions, both beginning student teachers and advanced student teachers highlighted mutual values such as care, trust, equality, dignity, fairness and honesty. A minor qualitative difference was a certain “romantic” tone in the beginning student teachers’ beliefs: “A teacher admires a child and what he/she already knows”, wrote one person (respondent 7, data set 1), while another noted that “As a class teacher, I can help a child to really blossom – to notice their full potential” (respondent 13, data set 1). In turn, advanced student teachers emphasised more general values, such as the importance of developing a moral conscience or the significance of pondering ethical questions as a critical citizen: ‘The ultimate aim of teaching is to promote good in the world”, wrote one student (respondent 22, data set 2), while another stated that “Students should be raised to critically observe society” (respondent 54, data set 2).

The pedagogical interaction position was emphasised similarly by both beginning and advanced student teachers in their PPTs. Both groups stressed the importance of creating a safe environment and team spirit within the classroom. The advanced student teachers stressed the role of the teacher as an adult, not as a friend of the pupils, somewhat more than did beginning student teachers.

With respect to the didactical position and the orchestrating position, the main themes in both data sets were related to diverse teaching methods, differentiation in teaching and child-oriented teaching. However, advanced student teachers also emphasised intentionality in teaching and the importance of lesson planning and assessment in learning; these themes were not highlighted in the beginning student teachers’ PPTs. The encouraging position included parallel beliefs in both data sets. Both beginning student teachers and advanced student teachers highlighted the significance of encouraging and inspiring students in order to promote meaningful learning. Motivation, creativity, humour, a welcoming environment, a positive attitude and a teacher’s interest in pupils’ studies are all salient aspects of encouragement.

With respect to the content position, beginning student teachers stressed specific subjects, for example sport, reading skills, maths and art, whereas advanced student teachers emphasised the importance of ecology, social skills, group work and data acquisition skills.

The major qualitative differences occurred in the teacher position. Beginning student teachers stressed the personal elements that defined them as teachers: “I take care of myself and that I have sufficient free time”, wrote one (respondent 11, data set 1), while others stated that “I want to prosper in my work” (respondent 24, data set 1) and “I don’t take myself too seriously. … I can laugh at my mistakes … ” (respondent 44, data set 1). Advanced student teachers emphasised the necessity of continuously reflecting on one’s own work and the importance of professional development: “My aim is to reflect on my work and my practice continuously”, said one student (respondent 70, data set 2), while another noted that “A teacher has to ponder and reflect on their own practice, choices and decisions in order to grow and develop into a better professional” (respondent 81, data set 2).

With respect to the context position, the qualitative differences were minor. Both groups emphasised the significance of collaborating with home and the work community. Also, a teacher’s role as part of society was seen as an important element; it was emphasised slightly more often in advanced student teachers’ PPTs.

Discussion

The beliefs held by a teacher about the teaching-studying -learning processes play a pivotal role in high-quality teaching since they have an effect on pedagogical practices and student learning (Ahonen, Pyhältö, Pietarinen, & Soini, Citation2014). According to Beijaard and Meijer (Citation2017), becoming a teacher requires the capability to interpret practices from different perspectives because of the role reversal from that of being a student to that of being a teacher. If the beliefs that guide and shape classroom practice are left unspoken, such beliefs may prove resistant to change (Korthagen, Citation2010), and there is the risk that former beliefs will not fit with a teacher’s new role in the classroom (Beijaard & Meijer, Citation2017). Likewise, Meschede, Fiebranz, Möller, and Steffensky (Citation2017) claim that teachers may only focus on classroom events that match their pre-existing beliefs about teaching, subject matter and student learning. Hence, the role of TE is crucial for ascertaining the nature of beliefs that student teachers hold during their TE and how they change (see Izadinia, Citation2013)

This study explored the teacher identity positions, i.e. beliefs, of beginning and advanced student teachers in one Finnish primary education teacher programme. It is not surprising that gradual qualitative differences emerge in student teacher identities as TE proceeds. The results demonstrate that student teachers become aware of the fact that a teacher should be ready to reflect on, develop, learn and embrace new challenges. Thus, we can conclude that as TE progresses, an awareness of the complex nature of a teacher’s work increases and an understanding of the responsibility to continually pursue professional development becomes a part of teacher identity.

However, despite the increasing awareness of the complexity of teaching work, the results indicate that the overall differences in teacher identities are minor during TE. This finding is somewhat surprising, since advanced student teachers have gained broader experience in their TE, including practice periods at schools. Values, the pedagogical interaction between teacher and students, and managing the various aspects of teaching were manifested as constant beliefs during the TE and unquestionably they may be seen as natural positions as student teachers develop their teacher identities. These findings are parallel to studies that have shown that TE may not change student teachers’ beliefs (Tanase & Wang, Citation2010; cf. Levin et al., Citation2013).

One obvious result of this study was the lack of beliefs by student teachers in the context position (see ). Schools are not isolated islands, but a part of society, and if we strive to educate pupils to successfully manage in an ever-changing world, then high-quality teaching requires that teachers be able to understand and navigate within social and political structures (see Maclellan, Citation2017). Thus, does TE provide the right circumstances for helping student teachers to critically confront and reflect on their existing beliefs and expand their perspectives?

Table 2. Teacher identity I-positions of the beginning and advanced student teachers based on the beliefs expressed in their PPTs.

On the basis of the results, values and pedagogical interaction between teachers and students play a significant role in the formation of student teachers’ teacher identities; these positions were clearly emphasised in both beginning and advanced student teachers’ beliefs. This is certainly worthy of consideration, as the profession needs to have idealistic teachers who always prioritise what is in the best interests of the child (see, e.g. Tirri & Husu, Citation2002) and who want to become excellent teachers with high moral values (see, e.g. Tirri & Husu, Citation2006). This study is in line with Chong, Low, and Goh (Citation2011) research on 105 graduating teachers, where they found that one-third of them saw their forthcoming work as purely part of a noble and caring profession. However, on the side of idealistic views of teaching, TE should also promote a more realistic view of teaching, as overly optimistic beliefs do not produce effective teaching (Thomson, Turner, & Nietfeld, Citation2012; Walkington, Citation2005). In addition, although student teachers have a clear idea of what makes for a good teacher, and their awareness that teaching is above all a moral endeavour seemingly forms the basis for their wanting to become a teacher, there is the risk of a “reality shock” when their ideals confront the actual situation in many of today’s schools.

The current study follows the discussion on the need for identity work during TE. It is essential to help student teachers not only by supporting them as they formulate their I-positions and clarify what kinds of teachers they want to become. We also need to help them to become aware of the possible conflicts and tensions in their teacher identity development in order to help them maintain the motivation for and commitment to their forthcoming work (Alsup, Citation2006; Beijaard & Meijer, Citation2017; Hong, Greene, & Lowery Citation2017; Sinclair, Citation2008; Trent, Citation2013). Pillen, Beijaard, and Den Brok (Citation2013) identified 13 different tensions affecting student teachers’ teacher identity development, for example tensions in the shifting role from being student to being teacher, conflicts concerning the way in which to support pupils and conflicts in their conceptions of how to learn to teach (see Beijaard & Meijer, Citation2017). According to Beijaard and Meijer (Citation2017), such tensions may have a negative influence on student teachers’ professional development and, furthermore, their longer term path of working as teachers. Strong beliefs may also have a negative effect in terms of how long teachers choose to remain in the profession.

Thus, as Walkington (Citation2005) states: “Teacher educators … must seek to continually encourage the formation of a teacher identity by facilitating pre-service teacher activity that empowers them to explicitly build upon and challenge their experiences and beliefs.” One fruitful way to facilitate student teachers’ identity work during TE would be to create the space for addressing conflicting I-positions (with their own sets of beliefs) and enable student teachers to engage in ongoing dialogue with their beliefs (see Leijen, Kullasepp, & Anspal, Citation2014).

One of the limitations of this study is that the data does not cover the very final phase of TE so that the entire arch of TE could have been included in the study. The students of the data set 2 represent different cohorts, although majority (65%) of them are 4th of 5th year students. The peculiarity of the Finnish TE program is that the students can take a fast track when they have relevant previous studies. Part of them did not spend as many years in the TE program, but they have conducted the required studies. However, this could have an effect on their thinking, and thus on their personal practical theories. With this data collection method we cannot eliminate the fact that many kinds of students participate in the courses, because they advance in their own paces. Nonetheless, this is something that needs to be taken into account when interpreting the results, as well as when planning new research designs. Furthermore, the results of this study are not generalisable as such. We also need to take into account that the data collection was part of course work, although it was not assessed. It is possible that the current course had some impact on the PPTs, but then again, PPTs are a dynamic construction that is in change all the time and is impacted by what the students experience. As the PPTs contain i.e. theoretical knowledge and experiences, it is only natural for the students to include what they have learnt in their PPTs.

Still, based on the results we consider that it is crucial to engage prospective teachers in becoming aware of and reflect on their beliefs as well as how these beliefs influence practices in order to ensure a solid basis for continuous professional development.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Katariina Stenberg

Katariina Stenberg, PhD, is a university lecturer at the Faculty of Educational Sciences in University of Helsinki, Finland. Her research interests include teacher education, teacher identity, reflection and theory-practice relationship.

Katriina Maaranen

Katriina Maaranen, Adjunct professor, PhD., works at the Faculty of Educational Sciences in University of Helsinki, Finland. She has researched Finnish teacher education from various viewpoints. Her interests include reflection, personal practical theories, professional development among other things.

References

- Ahonen, E., Pyhältö, K., Pietarinen, J., & Soini, T. (2014). Teachers’ professional beliefs about their roles and the pupils’ roles in the school. Teacher Development, 18(2), 177–197.

- Akkerman, S. F., & Meijer, P. C. (2011). A dialogical approach to conceptualizing teacher identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 308–319.

- Akkerman, S. F., & Van Eijck, M. (2013). Re-theorising the student dialogically across and between boundaries of multiple communities. British Educational Research Journal, 39(1), 60–72.

- Alsup, J. (2006). Teacher identity discourses. Negotiating personal and professional spaces. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Arvaja, M. (2015). Experiences in sense making: Health science students’ I-positioning in an online philosophy of science course. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 24, 137–175.

- Atkinson, D. (2004). Theorising How Student Teachers Form Their Identities in Initial Teacher Education. British Educational Research Journal, 30(3), 79–394.

- Avraamidou, L. (2014). Studying science teacher identity: Current insights and future research directions. Studies in Science Education, 50(2), 145–179.

- Beauchamp, D., & Thomas, L. (2009). Understanding teacher identity: An overview of issues in the literature and implications for teacher education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 39, 175–189.

- Beijaard, D., & Meijer, P. C. (2017). Developing the personal and professional in making teacher identity. In D. J. Clandinin & J. Husu (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 177–193). London: Sage Publications.

- Chant, R. H. (2002). The impact of personal theorizing on beginning teaching: Experiences of three social studies teachers. Theory and Research in Social Education, 30(4), 516–540.

- Cherrington, S. (2017). Developing teacher identity through situated cognition approaches to teacher education. In D. J. Clandinin & J. Husu (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 160–177). London: Sage Publications.

- Chong, S., & Low, E.-L. (2009). Why I want to teach and how I feel about teaching – Formation of teacher identity from pre-service to the beginning teacher phase. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 8, 59–72.

- Chong, S., Low, E. L., & Goh, K. C. (2011). Emerging professional teacher identity of pre-service teachers. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 36(8), 50–64.

- Day, C., Kington, A., Stobart, G., & Sammons, P. (2006). The personal and professional selves of teachers: Stable and unstable identities. British Educational Research Journal, 32(4), 601–616.

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2007). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115.

- Fairbanks, C. M., Duffy, G. G., Faircloth, B. S., He, Y., Levin, B., Rohr, J., & Stein, C. (2010). Beyond knowledge: Exploring why some teachers are more thoughtfully adaptive than others. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1–2), 161–171.

- He, Y., & Levin, B. B. (2008). Match or mismatch: How congruent are the beliefs of teacher candidate, teacher educators, and cooperating teachers? Teacher Education Quarterly, 35(4), 37–55.

- Hermans, H., Kempen, H., & Van Loon, R. (1992). The dialogical self: Beyond individualism and rationalism. American Psychologist, 47(1), 23–33.

- Hong, J., Greene, B., & Lowery, J. (2017). Multiple dimensions of teacher identity development from pre-service to early years of teaching: A longitudinal study. Journal of Education for Teaching, 43, 84–98.

- Horn, I. S., Nolen, S. B., Ward, C., & Campbel, S. S. (2008). Developing practices in multiple worlds: The role of identity in learning to teach. Teacher Education Quarterly, 35(3), 61–72.

- Izadinia, M. (2013). A review of research on student teachers’ professional identity. British Educational Research Journal, 39(4), 694–713.

- Kansanen, P. (2003). Opetuksen käsitemaailma [The concept world of teaching]. Juva: PS-Kustannus.

- Kansanen, P., & Meri, M. (1999). The didactic relation in the teaching-studying-learning process. In B. Hudson, F. Buchberger, P. Kansanen, & H. Seel (Eds.), Didaktik/fachdidaktik as Science(-s) of the teaching profession? (pp. 7−116). TNTEE Publications 2 (1).

- Korthagen, F. (2010). The relationship between theory and practice in teacher education. In E. Baker., B. McGaw, & P. Peterson (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (Vol. 7, pp. 669–675). Oxford: Elsevier.

- Kuusisto, E., & Tirri, K. (2014). The core of religious education: Finnish student teachers’ pedagogical beliefs. Journal of Beliefs & Values, 35(2), 187–199.

- Lamote, K., & Engels, N. (2010). The development of student teachers’ professional identity. European Journal of Teacher Education, 33(1), 3–18.

- Leijen, Ä., Kullasepp, K., & Anspal, T. (2014). Pedagogies of developing teacher identity. In C. J. Craig & L. Orland-Barak (Eds.), International teacher education: Promising pedagogies (pp. 311–328). Binlgey, UK: Emerald.

- Levin, B. B., & He, Y. (2008). Investigating the content and sources of preservice teachers´ Personal Practical Theories (PPTs). Journal of Teacher Education, 59, 55–68.

- Levin, B. B., He, Y., & Allen, M. H. (2013). Teacher beliefs in action: A cross-sectional, longitudinal follow-up study of teachers’ personal practical theories. The Teacher Educator, 48(3), 210–217.

- Maaranen, K., Pitkäniemi, H., Stenberg, K., & Karlsson, L. (2016). An idealistic view of teaching: Teacher students’ personal practical theories”. Journal of Education for Teaching, 42(1), 80–92.

- Maclellan, E. (2017). Shaping agency through theorizing and practicing teaching in teacher education. In D. J. Clandinin & J. Husu (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 253–269). London: Sage Publications.

- Meschede, N., Fiebranz, A., Möller, K., & Steffensky, M. (2017). Teachers’ professional vision, pedagogical content knowledge and beliefs: On its relation and differences between pre-service and in-service teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 66, 158–170.

- Nespor, J. (1987). The role of beliefs in the practice of teaching. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 19(4), 317–328.

- Niemi, H., Toom, A., & Kallioniemi, A. (eds). (2016). Miracle of education: The principles and practices of teaching and learning in finnish schools (2nd Revised ed.). Rotterdam, Taipei, Boston: Sense Publishers.

- Pillen, M., Beijaard, D., & Den Brok, P. (2013). Tensions in beginning teachers’ professional identity development, accompanying feelings and coping strategies. European Journal of Teacher Education, 36, 240–260.

- Rodgers, C. R., & Scott, K. H. (2008). The development of the personal self and professional identity. In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Freiman-Nemser, D. J. McIntyre, & K. E. Demers (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education (3rd ed., pp. 732–755). New York: Routledge.

- Sachs, J. (2005). Teacher education and the development of professional identity: Learning to be a teacher. In P. Denicolo & M. Compf (Eds.), Connecting policy and practice: Challenges for teaching and learning in schools and universities (pp. 5–21). Oxford: Routledge.

- Sinclair, C. (2008). Initial and changing student teacher motivation and commitment to teaching. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 36(2), 79–104.

- Stenberg, K., Karlsson, L., Pitkaniemi, H., & Maaranen, K. (2014). Beginning student teachers’ teacher identities based on their practical theories. European Journal of Teacher Education, 37(2), 204–219.

- Tanase, M., & Wang, J. (2010). Initial epistemological beliefs transformation in one teacher education classroom: Case study of four preservice teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 26, 1238–1248.

- Thomson, M. M., Turner, J. E., & Nietfeld, J. E. (2012). A typological approach to investigate the teaching career decision: Motivations and beliefs about teaching of prospective teacher candidates. Teaching and Teacher Education, 28(3), 324–335.

- Tirri, K., & Husu, J. (2002). Care and responsibility in ´the best interest of the child´: Relational voices of ethical dilemmas in teaching. Teachers and Teaching, 8(1), 65–80.

- Tirri, K., & Husu, J. (2006). The pedagogical values behind teachers’ reflection on school ethos. In M. B. Klein (Ed.), New teaching and teacher issues (pp. 163–182). New York: Nova Publishing.

- Toom, A. 2006. Tacit pedagogical knowing: At the core of teacher’s professionality (Research reports 276). Helsinki: University of Helsinki.

- Toom, A., Kynäslahti, H., Krokfors, L., Jyrhämä, R., Byman, R., Stenberg, K., … Kansanen, P. (2010). Experiences of a research-based approach to teacher education: Suggestions for future policies. European Journal of Education, 45(2), 331–344.

- Trent, J. (2013). From learner to teacher: Practice, language, and identity in a teaching practicum. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 41(4), 426–440.

- Vermunt, J. D., Vrikki, M., Warwick, P., & Mercer, N. (2017). Connecting teacher identity formation to patterns in teacher learning. In D. J. Clandinin & J. Husu (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of research on teacher education (pp. 143–160). London: Sage Publications.

- Walkington, J. (2005). Becoming a teacher: encouraging development of teacher identity through reflective practice. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 33(1), 53–64.

- Zierer, K. (2015). Educational expertise: The concept of `Mind frames` as an integrative model for professionalization in teaching. Oxford Review of Education, 41(6), 782–798.