ABSTRACT

This article addresses schoolteachers’ spatial work in the process of inhabiting and using a new school building. The study focuses on a historical case of a Danish open-plan school built in the early 1970s and shows how the teachers’ spatial work engages with questions of the organisation of bodies, sound, furniture and teaching aids. The article uses Tim Ingold’s notion of making – stressing the making of architecture, as well as pedagogy, as a continuous and never-ending process – and Karen Barad’s theory of agential realism to explore the teachers’ spatial work as part of the intra-actions of and mutual coming into being of school space, pedagogical ideas, teachers and pupils. Finally, the article analyses the transnational entanglements of the teachers’ spatial work through a discussion of the open-plan school as an architectural and pedagogical model found across the globe.

Introduction

We find ourselves in southeast Copenhagen in the early 1970s where a newly built school is preparing to open. The school named Peder Lykke School [Peder Lykke Skolen] is designed as a so-called modified open-plan school, with clusters of open classrooms lining large shared spaces – a layout that survives at the school today, more than 40 years later. As they prepare to move into the new facilities, teachers use borrowed premises where they plan and experiment with teaching practices for an open-plan environment.

In this article, I use this historical case from the early 1970s to explore how materiality and pedagogy, teaching strategies and practices interact (or intra-act) throughout different processes of occupying and establishing everyday practices in a new school building. Taking a closer look at the processes forming the initial stages of occupation, I argue that the coming into being of school architecture is a never-ending process involving both material and immaterial aspects. The study is particularly driven by an interest in understanding teachers’ “spatial work” as part of these processes, and how this work can be seen as entangled materially and discursively, both locally and transnationally.

The aim of this historical study is to provide insights into the configuration of open-plan schooling in the 1970s and up into the early 1980s with a particular focus on the role played by teachers’ spatial work. The analysis will show how these processes are materially and discursively situated in time, while also exploring how architecture and pedagogy entangle when inhabiting and using a new school building. Despite – or maybe because of – being situated in a specific time and place, the study is an invitation to reflect on contemporary challenges when inhabiting new school architecture and teachers’ potential role in developing school buildings.

Studying the spatial work of teachers involved in the making of new schools

In Denmark, recent decades have seen massive investment in a huge number of new school buildings. The political belief in the ability of new school architecture to enhance learning is well-established; architecture has frequently been used as a tool for reforming the school and its educational practices (Bertelsen & Rasmussen, Citation2018; Grosvenor & Rasmussen, Citation2018a). Nevertheless, studies of what happens to practices of schooling after a new building is occupied have, until recently, been rare (Blackmore, Bateman, Loughlin, O’Mara, & Aranda, Citation2011; Byers, Mahat, Liu, Knock, & Imms, Citation2018; Higgins, Hall, Wall, Woolner, & McCaughey, Citation2005). Likewise, the development of new school architecture in Denmark has so far taken place with very little evaluation of what happens after a new school building is put into service. Somewhat tellingly, the annual award for the best Danish school architecture often goes to a school that has only been in use for a couple of months.Footnote1 As such, the prize-winning architecture travels across municipalities and across borders, highlighted as a success, before there is a chance to get to know what school life is like in the new buildings. When things do not go as planned, it is all too easy to blame any shortcomings – despite a lack of documentation – on the teachers’ inability to make proper use of the shiny new facilities. I argue that there is a need for closer inspection of what actually happens when pupils, teachers and other staff move into, occupy and inhabit new facilities.

In a number of countries, there is a growing push towards more systematic post-occupancy studies and more substantial analysis of the everyday relations between built environment and pedagogies (Alterator & Deed, Citation2018; Daniels, Tse, Stables, & Cox, Citation2018). In addition, a body of research on the potential of participatory design processes has evolved, exploring and developing methods including stakeholders and users in the design of physical school environments. This literature has also highlighted the importance of participatory processes related to the first phases of inhabitation – especially focusing on experimentation and reflections among teachers and students (Bellfield, Burke, Cullinan, Dyer, & Szynalska McAleavey, Citation2018; Bøjer, Citation2019; Könings, Bovill, & Woolner, Citation2017; Woolner, Citation2015). Positioning itself within this body of research, this article seeks to further understanding of the role played by teachers in inhabiting new school architecture by looking back to a case from the 1970s.

Furthermore, I will argue that examining the process of inhabiting and establishing a rhythm of everyday schooling in new buildings gives a more general idea of the interplay between materiality and pedagogy in everyday school life, producing and transforming the specific form and content of pedagogical ideas and teaching strategies. Thereby, the article adds to the wealth of recent studies on the relations between architecture, pedagogy and everyday schooling (Dovey & Fisher, Citation2014; Ellis & Goodyear, Citation2018; Gislason, Citation2018; Mulcahy, Cleveland, & Aberton, Citation2015). By its historical approach to the study, important insights from the solid work on educational architecture in the field of the history of education is brought forward (e.g. Braster, Grosvenor, & Del Mar Del Pozo Andres, Citation2012; Burke, Cunningham, & Grosvenor, Citation2010; Burke & Grosvenor, Citation2008; Darian-Smith, Citation2017; Grosvenor & Rasmussen, Citation2018b; Lawn & Grosvenor, Citation2005). On this background and specifically exploring the role of teachers’ spatial work in processes of inhabiting and using new school buildings, the article provides a theoretical discussion and empirical exploration of the continuous and entangled coming into being of architecture, pedagogy and everyday schooling.

The school of 1973. A historical exploration of the making of school space

This paper will focus on an in-depth study of a single case: the above-mentioned Peder Lykke School (often called PLYS) that opened in the southeast of Copenhagen in 1973. Choosing a historical case allows a fuller understanding of how transnational flows, time-specific pedagogies, organisational structures and, not least, the role of the teacher play into the processes of occupying a new building and turning it into everyday school space. Thus, moving back in time makes it easier to maintain the complexity of inhabiting a new school space – something that might be more of a challenge if studying a more recent and less settled case.

PLYS was designated an open-plan school. The model of the open-plan school was originally developed in the US and the UK during the 1950s and 1960s, but the architecture and ideas soon spread across the globe. Shaped by national policies and local school cultures, a multitude of local variants and modified designs based on the original model emerged (Logan, Citation2017; Ogata, Citation2008). This was also the case in Denmark, where the original open-plan model, characterised by large open spaces populated by big groups of children, was often transformed to a layout with clusters of classrooms grouped around a communal area and with individual exits to outdoor areas (Kromann-Andersen, Citation1994; Olsen & Holst, Citation2001, pp. 19–20). PLYS was one of these adapted open-plan schools. In its original layout, PLYS had three wings with two blocks each, all functioning as independent teaching units (image 1). In each block, classrooms without doors were grouped around a larger space named “the central room”. Each classroom had its own outdoor space where the children could play during breaks and each block shared toilets, storage space and broom cupboard. The school also had a wing with specialised classrooms for e.g. domestic science and food preparations along a wide corridor to be used for teaching purposes and lunch breaks. The wing of specialised classrooms also had a gallery added to provide extra space for group work and similar activities (Fnu, Citation1975, pp. 193–194; Schack, Citation1979, pp. 91–92).

Image 1.The original floorplan for the Peder Lykke School. It shows the 3 separate wings and how they are all split into two. Each of the smaller areas (marked by A, B, C, D, E and F on the drawing) are built up around a large central room accessible from a number of attached classrooms without doors. It illustrates how the open plan architecture in this case takes form in intra-action with the idea of “the small school in the large school”, which played a profound role in the making of Danish schools at that time. Its aim was to create a safe environment for the child by dividing the school into smaller, independent areas

Closely tied to the architectural design of the open-plan school is the open-plan pedagogy. Open-plan pedagogy is not defined by one specific theory and it is to be found in various variations. As such, it might best be understood as an educational direction or a fragmented, decentralised and unstable movement. However, team teaching, variations in group sizes and teaching activities, and interdisciplinary and project-based student work were among the core concepts of open-plan schooling when PLYS was inaugurated. Furthermore, open-plan schooling was closely associated with ideas of individualised, active, self-initiated and self-directed learning, making reference to educationalists such as John Dewey and Jean Piaget and stressing the progressive values of a child-centred pedagogy and of learning through explorative and creative processes (e.g. Rathbone, Citation1971, Citation1972; Silberman, Citation1973).

Although the architecture was heavily modified from the original model, the idea of a distinctive open-plan pedagogy and an expectation of a close link between architecture and pedagogy were still part of the package for most of the Danish open-plan schools (Rabøl Hansen, Citation1973). The early thinking surrounding open-plan schools resonated with the widespread pedagogical experimentation characterising the Danish school sector in the 1970s (Coninck-Smith, Rasmussen, & Vyff, Citation2015), which meant there was no wholesale adoption of a predefined pedagogy. In fact, open-plan schools built in different parts of Denmark were often handed over to educators without any further instructions regarding how to inhabit them, viewing this as part of teacher autonomy. This was also the case at PLYS (Fnu, Citation1975; Nørgaard Pedersen, Citation1973).Footnote2 In addition, Danish teachers often found it difficult to transfer the ideas of open-plan pedagogy from the British and American school systems due to the considerable differences not only from Danish views on upbringing and teaching, but also differences regarding the basic organisation and length of the school day (e.g. Ballerup-Måløv-Kommune, Citation1972; Schack, Citation1979). However, the expectation that architecture and pedagogy should be closely linked foregrounds discussion of the relations between the two during the inhabitation process and makes the case of PLYS, as a Danish implementation of the open-plan school, particularly appropriate for exploring questions of how material space and pedagogy intra-act and how teachers’ spatial work plays a part in these intra-actions.

The story of PLYS is not about a new school building replacing an old school building. PLYS was an entirely new public school that formed part of a larger urban development project run by Copenhagen municipality. With the new school having to be built from the ground up, both literally and figuratively, the teachers’ pedagogical work and discussions at the time are well documented. This article analyses available written documents and photos from the first decade of the school’s existence. These written and visual sources are supplemented with an interview with two of the school’s former teachers. The empirical material consists of the numerous files in the Peder Lykke School Archive stored at Copenhagen City Archives. The minutes from staff meetings are particularly interesting as they report on everyday pragmatic issues concerning the inhabitation and use of the new building (and its challenges), but also include discussions among the teachers about teaching methods and more general pedagogical issues. The minutes are most often in the form of summaries of the questions raised and the discussions that took place. As such, the minutes are often written in short sentences and appear somewhat fragmented, with many questions and issues raised that remain unanswered elsewhere in the material. Some of the problems raised may have been solved outside the meetings; some may simply not have received further attention. Nevertheless, the archive gives a detailed insight into the work involved and challenges faced in the process of inhabitation and of the teachers’ ways of addressing and acting upon such challenges. Thus, despite its fragmented quality and the various loose ends, the school archive offers good possibilities for exploring not only the more pragmatic aspects of the inhabitation process, but also provides strong clues regarding the teachers’ pedagogical work and discussions during the first years of the school’s existence.

In addition to the minutes from staff meetings and other related files stored in the school archive, the analysis also reviews the comprehensive teacher-produced reports on the establishment of the new school, published in the early 1980s (Fog, Herlak, Schack, & Schack, Citation1982a, Citation1982b). These reports outline in great detail the teachers’ work to develop the school’s open-plan pedagogy. They also include glimpses of the teachers’ experiences as they retrospectively comment on the project. Whereas the minutes from staff meetings give a more staccato story of a somewhat messy process, the reports present neat narratives of the teachers’ experiences and tie together most of the loose ends, painting a picture of a more coherent, albeit sometimes difficult, project. Partly reflecting the different genres of the sources, the brief and on the spot minutes and the more detailed accounts in the retrospective reports are not seen as contradictory. Instead, I interpret them as relating to different aspects and different phases of the (meaning-making) process of turning PLYS into an everyday school space.

Image 2.A group of PLYS teachers holding a meeting about the clusters of classes around one of the central rooms. During the first decade of the school's existence, the teachers generally spent a fair amount of time developing and coordinating every day school activities and discussing the overall development of their open plan pedagogy. The image is dated 1982. Photographer: Thomas A. Fog

From early on in the project, I tried to get in touch with teachers that had been involved in the process of starting up PLYS. Only after completing the first draft of this article was I contacted by a former teacher who had come across my then already-old Facebook post. Soon after, I had the opportunity to interview two teachers who had been part of PLYS from its early years until their recent retirement. The interview with the former teachers offered stories about relations and everyday teaching practices, but it also gave me access to a still active meaning-making process regarding being a teacher at PLYS in the 1970s. Reading the already written analysis alongside these new stories and insights created a new layer of meaning, greater nuance and a different kind of coherence in the study. It not only added to the existing analysis, but led me to slightly reconfigure my earlier interpretations of the making of PLYS (Barad, Citation2007, p. 71; Tamboukou, Citation2014, p. 621).

About “making” and “cutting together-apart”: theorising the spatial work of teachers

The analysis in this article draws on the work of Tim Ingold (Citation2013) when understanding material (school) design as “making” and as an ongoing and highly complex process that involves both planning and building or construction, as well as occupation and use. In his writings on “building a house”, Ingold specifically mentions handover and occupation as an important phase in the process of making a material and architectural design (Ingold, Citation2013, p. 48).

Combining the idea of making with Foucault’s notion of governmentality, the handover and occupation phase can be seen as a moment where the aims of governance are coded and recoded, which may alter the contours of the wished-for pupil tied into the material school design in the first place (Grosvenor & Rasmussen, Citation2018a, p. 25). It becomes a moment for rejecting or adjusting the practices made possible, difficult or impossible when teachers and pupils relate to their new material surroundings. Subsequently, as the new building turns into everyday school space and in the continuous use of the building, the question is: In what ways does the building produce, revise, transform and perhaps replace pedagogical ideals and practices? Furthermore, in the encounter and entanglement with pedagogical ideas and practices – and, one might add, the ordinary everyday practices of teachers and students – the school buildings themselves can be seen to adapt and evolve (Grosvenor & Rasmussen, Citation2018a, p. 26).

In this article, I also draw on Karen Barad’s theory of agential realism (Barad, Citation2007, Citation2014) to analyse the teachers’ work in the processes of transforming PLYS as a new school building into everyday school space. Barad offers an approach that attributes materiality – in its historicity and sociality – an active role, but without ascribing a determinant status and without necessarily rejecting the distinction between things and humans (Barad, Citation2003, p. 823). Ingold specifically refers to this understanding of materiality in his unfolding of the notion of making (Ingold, Citation2013, p. 31). In agential realism, neither the material nor the discursive precedes the other. Rather, inseparable and simultaneous, matter and meaning are both productive forces (Barad, Citation2003, p. 823). I find Barad’s conceptualisation of matter useful for opening up the complexity of teachers’ spatial work. It grants significance to the material and its changeability and meaning-making – in the sense of the building, but also, for instance, walls, keys, doors, bodies, furniture – in the coming into being of the architecture and pedagogy of the open-plan school in the Danish case of PLYS.Footnote3

Furthermore, in the theory of agential realism, entities and/or agents are not conceptualised as predefined or pre-existing beings that interact with each other. Instead, they – to use Barad’s terminology – intra-act, and it is through this intra-action that they are differentiated and given their specific matter and meaning (Barad, Citation2007, pp. 141, 422). Applying this conceptual framework, I analyse how, throughout the 1970s – starting before the new school building was even completed – the teachers at PLYS were involved in a thorough spatial work in which teachers, pedagogy and materiality intra-acted in ways that defined and redefined both pedagogy and school architecture. Through their spatial work, the teachers themselves also came into being as a particular kind of teachers, tied to specific developments of an open-plan pedagogy.

Working through Barad’s theoretical thinking, the analysis deliberately avoids employing pedagogical theories as analytical or explanatory tools; nor is the objective to test the success of a predetermined open-plan pedagogy. Instead, I explore pedagogical meaning-making as compound and complex processes of continuous intra-actions. The analysis of PLYS shows how pedagogical theories – or, more often, elements or selected readings of pedagogical ideas and literature – are entangled and redefined in the making of the school. Through actively entangling circulating ideas, materialities and practices of open-plan schooling, the article stresses how PLYS, and the teachers’ spatial work, becomes a specific – and unique – example contributing to the never-ending meaning-making process concerning open-plan schooling.

In the analysis, I open up or dissect the spatial work of the teachers at PLYS by making a number of what Barad calls agential cuts (Barad, Citation2007, p. 348). These cuts are not intended to disentangle the phenomenon of PLYS as an open-plan school, but to explore what goes into, transforms and is given shape in the making of space (e.g. Barad, Citation2014). Thus, I use Barad’s idea of agential cuts to open and structure the analysis of the teachers’ highly complex spatial work in the coming into being of the new open-plan school, PLYS, as architecture and as pedagogy. I have chosen the cuts for further analysis by sifting through the empirical material several times with an eye for the teachers’ work related to moving into the new school building. This sifting was characterised by empirical curiosity and an attempt to remain open to surprise and the possibility of new analytical (re)directions (Tamboukou, Citation2019). However, in line with agential realism’s contention that the researcher is inevitably at stake in the research processes and intra-acts with the empirical materials (Barad, Citation2007, pp. x–xi), my academic background and knowledge of the topic played into my readings. In particular, my preoccupation with studies of school space within the field of the history of education can be said to have entangled with my sorting of the material. As seen in the various sections of analysis, although exploring new angles and perspectives, my attention is largely focused on issues and topics commonly found in the recent literature from this field. On this basis, the three cuts at the fore of the analysis are concerned with bodies, sound and teaching paraphernalia/furniture, and will be outlined in detail below.

Moving in: affective intensities of hope and despair

PLYS was and is famous for its classrooms having no doors. However, the no–doors policy was an issue that the teachers remembered questioning as they prepared to move into the school. They demanded ready-made solutions for adding doors when – and not if – the experiment failed (Hansen, Fog, & Alleslev, Citation1998, p. 9). This might sound like the teachers were sceptical of the new building, but that seems far from the case. In the years before moving into the new school, the teachers worked very actively to develop an open-plan pedagogy in temporary facilities at a neighbouring school, where they knocked down walls and experimented with their new pedagogical practices and organisational forms (Fog et al., Citation1982b, p. 7–10).

When finally moving to the new school, the teachers were eager to fully implement their newly developed open-plan pedagogy, claiming that “the opportunities were open [limitless] in the open-plan school building”.Footnote4 The teachers’ words echoed the architects’ early statements, stressing that PLYS was a school building offering open opportunities (Nørgaard Pedersen, Citation1973). However, implementing their prepared open-plan pedagogy was not as easy as they had hoped. In the minutes from the monthly staff meetings, a sense of frustration can be traced between the lines, perhaps best summed up in the complaints that it was necessary to fall back on old-fashioned discipline [kæft, trit og retning-pædagogik] in the new building when things got too chaotic and too noisy.Footnote5 The head teacher is also cited in one of the minutes when directing critique towards the teachers’ discussion of the ideal school. The head teacher suggested that things had gone downhill since moving from the temporary facilities to the new building, arguing that the teachers had too much resistance towards the situation in the new school buildings.Footnote6 However, the same head teacher was quick to acknowledge the teachers extensive work in developing PLYS’ open plan project. He later wrote, that: “ … all teachers had had to offer hours, hours and more hours in addition to the mandatory work hours to realise the school” as it looked like 10 years after its upstart (Fog et al., Citation1982b, p. 10).

Although directly addressed in the examples above, the tense atmosphere is generally apparent in the minutes from staff meetings and the written reports. In other words, the affective dimensions of the inhabitation process seem to have been strong, alternating between hope and despair. Overall, the transition from the temporary facilities to the new building and the years immediately following this move can be described with Deborah Gould’s reading of Brian Massumi’s notion of affect: “‘intensity,’ indicating non-conscious and unnamed, but nevertheless registered experiences of bodily energy and intensity” (Gould, Citation2009).

In line with the intensity of affective engagement present in the minutes, the two former teachers I interviewed stressed their engagement in the project of establishing a new school. As one of them put it:

We very often worked late. We thought it was wonderful. We were meant to be there and we were there. We lived at that school. People wanted it too. We had chosen it and we had fun. After all, we were delighted that we didn’t have to be in a school where we had to fight our way through a hierarchy of old fogeys.

The intense and seemingly affect-driven discussions about how to organise and rework space depicted in the minutes from staff meetings and other activities involving teachers and documented in the archive are given a powerful and positive tone through the former teachers’ memories. Thus, the empirical sources report on and accentuate the intensities weaved into the teachers’ spatial work. They also point to the need for devotion and time in the spatial work (image 2) – mechanisms I explore in the analysis below.

Spatial (re)makings: cuts of bodies, sounds and things

Through reading the empirical material, I have decided to further explore three different cuts that connect observations across different processes in the making of PLYS as an everyday school space. In each their way, the chosen cuts stress the bodily, sensuous and material elements involved in the teachers’ spatial work. The three cuts I delve into in the analysis are: the bodily cuts concerning rules of conduct, keys, and doors; the sonic cuts concerning the travel of sound and teachers’ communication; and finally, the thing-related cuts concerning the deep entanglement of furniture and teaching aids in the definition and redefinition of both school space and pedagogy at PLYS. Other cuts – e.g. concerning the visual aspects or even, in a much broader sense, the question of pedagogy – could also be applied and would certainly have framed the analysis differently. Thus, the choice of cuts for further analysis colours the observations made and frames the story told. That being said, the cuts chosen fulfil their purpose as a way of opening up for exploration of the complex but concrete processes of the coming into being of everyday school space in ways where the matter and meaning-making of both space and pedagogy are at stake.

1) Bodily cuts: rules of conduct, keys and doors

I call the first series of cuts bodily cuts as they have to do with pupils’ and teachers’ bodies. The body has been a central concern within historical studies of school and school life, exploring themes of discipline and embodiment, which I also address here (e.g. Burke, Citation2007; Gleason, Citation2018). Analysing the spatial work of teachers through agential realism draws specific attention to the role of material spaces and material objects in intra-actions surrounding the development of everyday school practices in the new buildings of PLYS. In the analysis, bodily cuts concern the organisation of bodies – where and how the bodies, teachers and pupils are allowed and/or expected to move. Actualised across different discussions and as part of the teachers’ spatial work, the issue of teachers’ and pupils’ bodies can be read as a central theme in the spoken memories, but also worked on and reworked in the minutes from staff meetings during the first years after moving into the new school building.

In the interview with the former teachers, they recall pupils’ freedom of movement, with very few spaces off-limits, as central to the everyday life established at PLYS. Their memories are of a school with children everywhere and where the teachers were also surrounded by pupils during activities such as preparing teaching materials. In the archive, it nevertheless appears that, despite pupils’ relatively free access to most of the school, it is relevant to explore the disciplining or controlling of pupils’ bodies when trying to understand the teachers’ spatial work related to moving into a new, physically non-traditional school building. The work involved in organising pupils’ bodies seems to be tied to concerns about disruption, restless and uncontrollable bodies, and a lurking chaos in the coming together of everyday school life. In the minutes from one of the first staff meetings after moving into the new building, a short report notes “pupils running confusedly in and out”.Footnote7 More implicitly, the potential for disruption is woven into the many discussions and decisions on both unofficial and official school rules in the minutes.Footnote8 In one example, the first rule states: “Pupils are not allowed to arrive at school until ten minutes before school starts and must enter the playground directly”. During the day, pupils are not “allowed to leave the school grounds”. Thus, the framework is established for when and where pupils are allowed and expected to be at school.

The same set of rules includes more specific guidelines for how the pupils (and their bodies) should move around school: ’So as not to disturb lessons, the following indoor rules should be observed: “walk – not run”/“talk – not shout”/“do not climb on the furniture”/“do not touch the loudspeakers”/”do not play in the toilets”’/“the basement is off limits.”’Footnote9 To reiterate, the rules often concern where the pupils are allowed to be and move about, but also how they are supposed to behave.

As in the above example, over time, the school rules became increasingly formalised in written text. The head teacher instructed the teachers to inform the pupils of the rules at least twice a year, especially the rules regarding “the prohibition on running, shouting and yelling, and the directions for where to park your bicycle and about using the main entrance.”Footnote10 Moreover, the teachers agreed to not only inform the children about the official rules, but also keep each other updated on and harmonise the more unofficial behavioural guidelines they presented to pupils. As such, the teachers’ spatial work, on a political as well as an everyday level, concerns organising pupils’ bodies and directing their movement.

Here it is important to mention that rules of conduct played a central role in the Danish regulation of everyday schooling throughout most of the 20th century. From the 1960s, not only teachers but also pupils and parents were getting involved in formulating the local rules of conduct (Coninck-Smith et al., Citation2015; Gjerløff, Jacobsen, Nørgaard, & Ydesen, Citation2014). As such, at the time of PLYS’s opening, there was both an official expectation that the school had a public set of rules and that these rules were closely tied to local practices and ideals of schooling. Thus, the development and implementation of the rules of conduct at PLYS can be seen as highly entangled in both national legislation and local school practices, tied to at least some of the values, which were a matter of (re-)negotiation of the school at the time.

A more practical matter is the disciplinary project of what, to use a term from Lefebvre, could be called “breaking-in” the pupils’ bodies so as to establish the right rhythm for the open-plan project (Lefebvre, Citation2005, p. 49). The head teacher repeatedly asked that the doors between classrooms and outdoor spaces not be usedFootnote11 to avoid heat loss. This is a practical concern that is possibly entangled with concerns within the discourse surrounding the contemporary oil crisis. Nevertheless, it influences the organisation and movements of pupils’ bodies in the new open-plan school in ways that counteract and alter the original purpose of having direct access to outdoor spaces from the individual classrooms during teaching hours (Nørgaard Pedersen, Citation1973, p. 192; Fnu, Citation1975). It interweaves with and alters both the thinking and matter of the dimension of open space in open-plan pedagogy, as well as the modified Danish model of the open-plan school, which was designed in line with contemporary values stressing easy access to outdoor spaces (Holst, Citation1971).

At staff meetings, the practicalities concerning where and how teachers could enter the school were also debated, as was the teachers’ ability to provide others with access to different parts of the school building. Despite the no-door classrooms, there were still a number of doors and entrances that required a key and that were locked outside normal school hours. The question raised was: Who should be given a master key that worked in all the different locks in the building? Only a few selected individuals or all teachers and administrative staff?Footnote12 Various models were tested, and the head teacher was cited as saying “it takes self-discipline to have the master key”.Footnote13 Again, this could be seen as a matter of organising and breaking bodies into space; in this example, it is the teachers’ bodies and their movement within the school that is at stake. Moreover, it could be read as material-discursive constructions of hierarchy and acknowledgement of the individual teacher, involving teachers’ bodies and keys as well as issues of administrative and legal responsibility for keeping the school a safe space.

These selected examples of rules of conduct, keys and doors, and of pupil behaviour, teacher autonomy, indoor environment and school finances, to mention a few aspects, come together in the organisation of bodies and bodily movements. Space is hereby reworked and given an everyday rhythm that is slightly different from the ideas and modelling of the original spatial design. It not only creates order and borders, which are otherwise less visible due to the physical openness of the building; pupils and teachers are shaped in the sense of where and how to move.

2) Sonic cuts: On the travel of sound and teachers’ communication

Another series of analytical cuts that can help understand the coming into being of PLYS as a school space are what I refer to as sonic cuts (image 3). Sound has been largely neglected in the study of schooling, but arguing it impossible to understand educational processes without an acoustic perspective, a focus on soundscapes – also in the study of school architecture – has gradually become part of research on the history of education (Burke & Grosvenor, Citation2011; Darian-Smith, Citation2017b; Verstraete & Hoegaerts, Citation2017). Walter Gershon’s work is centred on contemporary curriculum studies, but he also argues for the overlooked relevance of sound when trying to understand education. Gershon points to the relationship between sound, teaching and learning and writes about how this is also of concern for teachers (Gershon, Citation2018). In the teachers’ spatial work at PLYS, sound is a recurrent issue in the intra-actions through which the school’s physical architecture, its pedagogy and its teachers were shaped.

After occupying the new school, the teachers highlighted how the invisible borders, open spaces and, not least, the resulting noise issues forced them to be, as mentioned before, stricter in their pedagogical approach than first expected.Footnote14 In the interview with the two former teachers, they recall how they had to coordinate activities in adjacent classrooms so as not to disturb each other:

It was not like one class could have playtime and the other two not. It was impossible – and it was still the buildings. So there were a lot of things you couldn’t do. Then we held birthdays together.

As such, the teachers’ spatial work can be seen as involving a number of sonic intra-actions of synchronisation, where the buildings and the organisation and practice of teaching were at stake. Furthermore, the former teachers emphasised the sonic dimension as something they were continuously attuned to:

It depended on how it worked in the morning – whether it was very quiet, very peaceful. That delicious atmosphere where you could sense the calm. On such days, the students could walk around [and visit each other’s classes], I think. I certainly think so. Then I had the feeling that we were together. It gave me a sense of security.

The spatial work is here about creating and maintaining a pleasant soundscape. The soundscape of the open-plan school seems to have been characterised by a certain fragility, which also gave it a particular strength, allowing a special kind of togetherness when peace and quiet was achieved.

Image 3. The teacher’s and children’s bodies and voices (as well as the drawing board, the walls and the carpet) are intra-acting in a teaching situation taking place in the central room. The children are waving their fingers to let the teacher know, that they have an answer for her question. Behind the teacher, the entrances without doors are visible as is the loud speaker for the office to call through. The image is dated 1982. Photographer: Thomas A. Fog

An additional sonic cut involves the communication among teachers and between teachers and the school management. After moving into the new buildings, the teachers soon realised that the absence of a staffroom, and the division of teachers into teams connected to the different and separate clusters of the school, meant that they had very few casual encounters with one another for exchanging short messages and nowhere to share information as such (Fog et al., Citation1982b, pp. 23–29).Footnote15 The teachers’ spatial work to enhance their internal communication raised a number of ideas. One of the suggestions was to use the loudspeakers installed in each classroom for the head teacher to make announcements to the teachers at a set time. However, for the first few years, the chosen solution was a weekly printed newspaper.Footnote16 Looking back ten years later, the teachers reflected upon the extensive use of written communication and the discipline and time required to get things written down and passed on to others, and to keep oneself updated by reading messages from others (Fog et al., Citation1982b, p. 29). Thus, as a sonic cut, it is a material-discursive becoming where the shared communication is muted and translated from spoken to written form.

Moreover, with the absence of doors into the classroom, the free passage of sound (and sights) played a role in the configuration of relations among the teachers. In the interview with the two former PLYS teachers, it was stated that “It meant we couldn’t lie” and “You might as well go in and cry right away”, meaning that you could not hide away any of the problems occurring in the classroom and that you might as well go to your colleagues to ask for help and comfort. It was contrasted to experiences from working in a classroom based school where problem-related noise travelling through the closed classroom doors were tabooed and perceived as the teachers’ individual problems. In the open space, this noise was said to turn into an invitation to also share the difficult moments of teaching, which helped strengthen cooperation among teachers. These are just a few examples of the teachers’ attempts to make the challenging space of the new school manoeuvrable; examples that are once again very much a matter of organising and thereby making space, but this time provoked by and working on the sonic aspects of space.

3) Thing-related cuts: Furniture and teaching aids

A third cut I will suggest for understanding the complex making of space involved in establishing an everyday rhythm at Peder Lykke School concerns the aggregation of things involved in schooling (image 4). It is tempting to understand furnishings and the purchase of teaching materials as a matter of filling space. But, following thinkers like Ingold and Barad, this article goes beyond a concept of space as a mere container “to be filled” (Crang & Thrift, Citation2000, p. 2). Rather, furniture and teaching aids are seen as an essential part of the making of school space.

With reference to specific school subjects or broader developmental processes, the teachers at PLYS constantly put forward their requests for books, other teaching materials, and toys. The selections of teaching aids generally follow the subject-specific discourses and the availability of materials. As an example, a recurring item on the agenda in the minutes is the purchasing of modern teaching technologies such as cassette tapes and film projectors.Footnote17 In the first years, chaos seemed to hide around every corner, with teachers reporting their difficulties in ascertaining what materials were actually available and with things, particularly AV-equipment, frequently disappearing. However, as time went by, checklists were created, people were put in charge of maintaining the various collections, and there was continued optimism that the storage rooms would soon be equipped with locks.Footnote18 The selection and ordering of objects and their flow can be seen as material and discursive making of space, shaping, colouring and adding pedagogical meaning to the open-plan school.

Image 4. An encircled study corner has been created in one of the central rooms. Different kind of teaching materials are within reach of the pupils. Green plants decorate the space. The image is dated 1982. Photographer: Thomas A. Fog

Several brochures advertising school furniture were also to be found in the school archive, accompanied by lists of pros and cons and provisional budgets. This indicates a concerted effort to find the most suitable furniture matching the school’s pedagogical ambitions, the demands of physical durability and the financial resources available.Footnote19 The later reports show how the school’s furnishing is constantly negotiated when it comes to the use of space for various teaching situations (Fog et al., Citation1982a, Citation1982b). Likewise, in their interview, the former teachers tell how furniture and things were key elements in teachers’ ongoing spatial work:

In the central rooms, we built these boxes where you could sit and do a kind of “cocooning”, and you could sit there and read or work, or work together in pairs. We used that space and it meant you could get away from the class. I do not know if it was so important, and of course some of them could cause trouble there, but the central room was used – it was not just a passageway, and all the time we tried to get it to work, because otherwise it would end up as one big room, and then you would just have no doors, but it would in reality be the same as a school with a big main school hall [aulaskole]. We kept organising it and kept it neat and tidy.

In this example, the open building, teachers, boxes, rubbish and educational practices intra-act in ways where they are constantly reconfigured. The teacher is fully aware that it is neither the building itself nor the things nor the furniture that define the open-plan school and its pedagogy. Rather, it is when it all comes together in ways that are not always predictable, but constantly tested out by the teachers at PLYS. In other words, a never-ending adjustment or becoming of the educational space takes place through the reorganisation of tables, chairs and movable partitions in their entanglement with teachers, pupils and teaching practices.

The teachers’ spatial work: building pedagogy

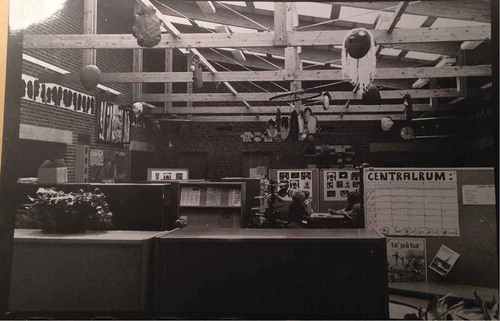

Through the suggested three series of cuts, we get a sense of how PLYS as school space was constantly in the making, both materially and discursively, in the years after occupation. To merge the different analytical cuts and introduce a discussion of how they are reflected in the more explicit material-discursive strategies of teaching, I think it is worth taking a peek at one of the school’s common areas a few years after the opening.

In the school archive, I came across a few photographs.Footnote20 One of them depicts one of the large common areas around which the classrooms are clustered (image 5). In the picture, you can see how movable pieces of furniture are arranged to create smaller rooms in the room, and green plants and pupils’ artwork hang from the ceiling and adorn the movable partitions. Right at the front of the picture, there is a large time schedule for the use of the common area. The image in the photograph can be seen as illustrating how the teachers work pedagogically and materially with space, giving it its particular shape. Judging from the text on the archival box in which it was found, the photograph dates from the period 1974–1983. The amount of furniture and decorations that have been amassed suggests that the photograph was taken well into this period. The depicted schedule fits with a statement in a three-page brochure from 1976 that was also found in the archive and presents practical information to be used by teachers. Here it is stated that “open-plan pedagogy is not a no-plan pedagogy!!!” The exclamation marks underscore the importance of the message.Footnote21 I read this as differing somewhat from the statement of the open opportunities of the open-plan school building mentioned earlier in this article.Footnote22 Over the years, the teachers moved from a belief in open opportunities and a looser and more experimental approach to a highly structured approach where space is also changed and adapted. Overall, the teachers’ pedagogical, and in many instances spatial, work might be read as a continuous sense-making process in relation to open-plan pedagogy.

Image 5. The photo found in the archive and mentioned in the article text. Flexible furniture, tables and bookshelves re-organise the open space. Green plants and pupils’ productions have become part of the room. The image is undated, photographer unknown

In the minutes from staff seminars and the teachers’ own reports from the early 1980s, there is a particular focus on the school’s so-called “central rooms”, which is the school’s name for the larger communal areas between the classrooms, like the one in the photograph (Fog et al., Citation1982a, Citation1982b). The discussions about the use of these central rooms and the written guidelines found in the archive are concerned with what ought to be available to the pupils in these rooms and how this aligns with a plan for accustoming pupils to working in this space. In the archives, a plan from 1977 outlines the teachers’ development of pathways to inclusion in school life for the individual child by adapting the central rooms to the different age groups they catered for (image 6). The teachers thereby agreed not only to adapt teaching activities and learning goals according to the child’s age,Footnote23 but also to adapt the room’s layout, furnishings and the available teaching materials. The work to develop the central rooms is also described in the later reports (Fog et al., Citation1982a, pp. 9–11, 16, 32; Citation1982b, pp. 52–68), illustrating how the teachers’ spatial work can be understood as material-discursive processes – complex entwinements or, to use Barad’s terminology, intra-actions in the sense of the playing together of the inseparable yet different material and immaterial elements (Barad, Citation2003, Citation2007). The central rooms involve intra-actions of open spaces, furniture, teaching materials, pedagogical concerns and educational ideas. The intra-actions involved in the teachers’ spatial work are readable as not only defining, but constantly redefining and reworking the open-plan architecture and the open-plan pedagogy of PLYS.

Image 6. Drawing of the central room for the the oldest pupils. Compared to the usage of similar drawings in contemporary Danish open plan schools (e.g. Ballerup-Måløv-Kommune, Citation1972, Citation1973), the drawing might very likely have been a tool in the planning and continuous work with the central rooms, e.g. the spatial work of the teachers. The drawing is found in one othe evaluative reports for the first ten years of PLYS’ life (Fog et al., , Citation1982b)

The teachers later report on the many hours spent, the many adjustments needed, and on how they continuously had to plan everyday school life in minute detail as part of the process of developing and practising an open-plan pedagogy. Again, this planning is heavily entangled with the spatial work of deciding and arranging who has to be where and when, and of structuring space in accordance with the teaching methods developed over time.

Transnational entanglements I: making sense of open-plan schooling

With all its details and specificity, a close examination of the process of inhabiting a new school building and establishing a rhythm of everyday life in new facilities, such as that presented in this article, might be seen as a local standalone case with little wider relevance. However, based on the theoretical framework of the histoire croisée approach developed by Werner and Zimmermann (Werner & Zimmermann, Citation2006), I will argue that this is far from the case. On the contrary, the teachers’ spatial work is strongly intertwined or entangled transnationally, materially as well as discursively, when it comes to both architectural models and pedagogy. The histoire croisée approach focuses on empirical intercrossings and was developed to address some of the problems in working with comparative methods and transfer studies. Werner and Zimmermann criticised such approaches for their difficulties in breaking with contextual constraints and for working with a fixed frame of reference (Verbruggen & Carlie, Citation2009, pp. 293–294; Werner & Zimmermann, Citation2006, p. 36). Histoire croisée is relevant to the study of PLYS as it analyses not only interconnectedness in history, but also how this interconnectedness generates meaning in different contexts (Werner & Zimmermann, Citation2006, pp. 32, 49). As such, PLYS and the spatial work of its teachers can be seen as an intersection, a point of crossing, in a broader network of negotiations and reinterpretations. One obvious example is the way the school and the teachers became entangled with the transnational open-plan movement, which, in many ways, was a very loosely constructed network.

The PLYS building was modelled on American and especially British open-plan schools designed by architects and municipal officials. This blueprint was modified to an extent to accommodate the accepted maxim “that buildings last and pedagogies pass”, which was central to the discourse on Danish school architecture at the time, and it has since been questioned whether PLYS is even a genuine example of open-plan school architecture (Egelund, Hegner Christiansen, & Kleis, Citation2005). Nonetheless, among the teachers preparing to move into the school, PLYS was undoubtedly considered an open-plan school, and the associated documents and publications focus heavily on developing an open-plan pedagogy (Fog et al., Citation1982b).

The attendance at a conference on open-plan schools in Cheshire, England would become an important collective experience for the teachers at PLYS. At the time, there were more than 50 open-plan primary schools in Cheshire and a specific notion of “open education”. The teachers would later note in their reports that watching open-plan schools at work and listening to British colleagues and experts talking about open-plan schooling had an impact – first and foremost stoking their enthusiasm for the project, but also influencing the pedagogical practices they would later test at PLYS (Fog et al., Citation1982b, pp. 11–14). This must be seen as an example of the transnational entanglements involved in the local development of pedagogical practices. Differences in the school structure, the teaching profession and teacher training, and the length of the school day are all mentioned as factors limiting what could be directly translated to a Danish setting. As such, the entanglements are to a large extent about affects.

According to the teachers’ reports, the study trip would over time add specific meanings to the open-plan approach as both an architectural design and a pedagogy, perhaps helping to merge the two. I believe that it makes more sense to view the school and the teachers’ spatial work as an intercrossing in a broad, dynamic network comprising both nearby and more geographically distant schools, whereby pedagogical practices and ideas from elsewhere feed into and are influenced by local practices and experiences, than simply seeing PLYS as an example of international ideas implemented in a local context.

Histoire croisée´s rejection of a primarily top–down analytical approach allows an understanding of how PLYS would itself quickly become popular among visitors interested in how to do open-plan schooling. In the minutes, we find schedules for the school’s international visitors. In the last week of April 1976 alone, teachers, principals, educators and architects from Austria, Iceland, Sweden, France and Germany visited the school to hear about the experiences with open-plan schooling.Footnote24

Transnational entanglements II: making a school without failures

I would like to return to the central rooms in PLYS to consider another entanglement seemingly important to the teachers’ spatial work. This crisscrossing is about inclusion, or integration as it was called in Denmark at the time, and about the transnational flow – and transformation – of pedagogical ideas and literature. In the school archive and the teachers’ reports, the issue of inclusion or integration comprises another, sometimes very explicit, transnational entanglement, particularly in terms of the introduction of specific pedagogical ideas and theories in the process of developing the new open-plan school.

Issues of integration and differentiated instruction appear central to the whole open-plan project of PLYS. Already when agreeing on a set of school objectives just before and just after moving into the new facilities, some of the teachers suggest: “making differentiated instruction the main objective”.Footnote25 This is followed by the statement that: “The open-plan school offers better possibilities for this than the traditional school”.Footnote26 In the ensuing discussion, organising teaching across a larger space and across year groups is proposed as a way of enabling differentiated instruction and freeing up extra time and resources for weaker pupils. In the archive, there is also a draft application to the national council for teachers’ pedagogical developmental work.Footnote27 Here the teachers ask for extra hours to work on the central rooms in order to establish a teaching practice that meets “the high degree of differentiated instruction required to maintain a low level of pupil segregation in special classes and avoid establishing remedial teaching programmes”.Footnote28 These are just a few examples of how the teachers’ spatial work is continuously wrapped in or crisscrossed by the issue of inclusion.

At staff meetings, the issue of inclusion is explicitly brought up on a number of occasions, often making visible the broader entanglement of these local processes. At one of the meetings, a teacher reads aloud from a book on inclusion and differentiated instruction by the Danish educator Jesper Florander. The full passage is cited in the minutes. Interestingly enough, it is a passage where Florander writes about “the development and perception of these issues in countries like Sweden and the US”.Footnote29

In another meeting, the teachers had asked each other to consider whether “a school without failure” is a cliché. This is a question asked with explicit reference to the American psychiatrist William Glasser’s book with the similar name “Schools without failures” (Glasser, Citation1969). One group of teachers responds that it is a “pipedream” that the school has tried to chase, but that can never be fully realised.Footnote30 Another group of teachers simply answers “yes” to the question of whether it is a cliché.Footnote31

The crisscrossing of the teachers’ spatial work with issues of inclusion yet again involves transnational entanglements. And yet again, I suggest that the dynamics, flows and directions of these entanglement processes are noteworthy. In the case of the Danish educator cited for his descriptions of parallel international developments, the references function as an argument for moving in certain directions and are not necessarily concerned with specific examples or concrete pedagogical ways of thinking. With the work of Glasser, it is a different matter. Glasser’s book had recently been translated into Danish and had also been circulated among the school’s teachers as suggested reading in the form of study circles.Footnote32 From their discussions, it appears that some of the teachers may have been more knowledgeable of the content than others; some of them were probably aware of the ongoing discussions about his work in other circles, while others were perhaps only familiar with the title. In other words, more or less digested and more or less selected elements of the American author William Glasser’s book about inclusion are taken up and reworked in the local context of PLYS. Glasser’s work may have affected the PLYS teachers’ approach to their pupils and to integration, potentially linking it to the spatial work and adding new meanings to the open-plan school. Simultaneously, new meanings may have been given to Glasser’s work, to matters of inclusion and to the broader project of comprehensive schooling.

Conclusions

My particular focus is on the somewhat overlooked importance of teachers’ spatial work in the inhabiting of a new school building. This is explored through a historical case, concentrating on the teachers’ spatial work at PLYS, a school opening in the south of Copenhagen in the early 1970s. The analysis takes its outset in the intensity of affect seemingly involved in inhabiting the new space – waves of dreams, hopes, frustrations and moments of despair – but quickly moves to questions of what could be perceived as everyday practicalities (e.g. rules against playing in the toilets, informal communication, keys, lost tape recorders) involved in inhabiting the new school. I find this joint presence of intensity and everyday practicalities central for understanding the teachers’ spatial endeavours. The teachers are on the frontline, so to speak, encountering things and people, and constantly having to adapt and adjust themselves and their environment in the effort to create an appropriate rhythm of everyday schooling.

It is also in these processes of creating a rhythm of everyday schooling that elements of internationally acknowledged pedagogical thinking and its related practices are introduced and given meaning. In the example of PLYS, this happens through the teachers’ study trips, their selected readings and inputs from contemporary debates, which become part of their discussions, their teaching and their attempts to organise the physical layout, time and pupils, while constantly coming up against challenges relating to everyday practicalities. Through this highly spatial work, the sense-making involved in becoming a pupil – and a teacher – but also in open-plan pedagogy and open-plan architecture might be (re-)constituted over and over again.

I have written the story of PLYS through the application of three agential cuts and two examples of transnational entanglements, which all shows how the school comes into being through the specific material-discursive processes of its time. Indeed, PLYS came into being through specific intra-actions of pedagogical practices, school policies, teachers, pupils, walls, doors (and a lack of doors), chairs, keys, intensities, sounds etc. of the early 1970s. The analysis also shows how this seemingly local work is materially and discursively enmeshed in broader national and transnational processes. Specific and unique, prompted, inspired and shaped by these broader, yet time-specific processes, and also feeding back into them, adjusting and adding new material and discursive meanings to e.g. the meaning-making of open-plan schooling. However, I think the story also tells us how the coming into being, the making, of an educational space may more generally be seen as a process that is by no means completed with the erection of a building. On the contrary, the making of educational space is narrated in the story of PLYS as a never-ending process of exploration and adjustment. Especially interesting is the entanglement and constant reconfiguration of the everyday pedagogical thinking and pedagogical practices involved in these processes (particularly through the continuous work of the teachers), tying the ongoing meaning-making of architecture and pedagogy closely together.

This theoretical and empirical exploration of the entangled coming into being of architecture, pedagogy and everyday schooling at PLYS is only a small-scale study and a humble contribution to the research on educational architecture. However, it argues for the importance of looking beyond the inauguration of the building and taking into consideration what may be seen as everyday practicalities. Moreover – and perhaps most pivotally – it is an enquiry that encourages us to pay attention to and try to further understand (and preferably also make room for) the situated entanglements of the spatial work of teachers involved in turning a new building into pedagogical practices and everyday school space.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lisa Rosén Rasmussen

Lisa Rosén Rasmussen is associated professor of contemporary history of schooling at the Danish School of Eduaction (DPU)/Aarhus University, Denmark. In her work on educational architecture, school space and materialities of schooling, she deals with the intercrossings of policy, pedagogy and everyday life.

Notes

1. For more information about this award, see: https://nohrcon.dk/vidensbank/kaaring-af-aarets-skolebyggeri/

2. A national magazine on architecture described how the central rooms at PLYS encouraged experimental teaching approaches and how the use of movable furniture gave each block the opportunity to “create an open-plan situation e.g. for team teaching”, but also allowed “to go for conventional classrooms permanently assigned to one form” (Fnu, Citation1975, p. 192).

3. Ning de Coninck-Smith historical study of the small island school “the Elbow” similarly combines Karen Barad and Tim Ingold’s thinking, but focuses on materialities and class (Coninck-Smith, Citation2017) Malou Juelskjær has done extensive work on contemporary school architecture using Karen Barad (Juelskjær, Citation2014).

4. Minutes from a staff seminar, undated. In the box ‘Building projects [Bygningssager] 1983–1986ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives. Judging from the descriptions of the discussions, as well as the title “The future structure of the school”, this seminar was likely held before or just after moving to the new building in 1973. Despite being labelled ‘1983–1986ʹ, much of the material in this box is from the 1970s.

5. Minutes from staff meeting 14.10.75, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

6. Minutes from staff meeting 16.02.77, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

7. Staff meeting 29.10.73, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

8. Staff meeting 12.09.73, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

9. Undated but found between papers dated 1974–1975. In the box ‘Minutes from staff meetings 1973–1977 [Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977] in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

10. Minutes from staff meeting early 1976. In the box ‘Minutes from teacher meetings 1973–1977 [Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977] in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

11. Minutes from staff meetings 29.10.73 and 19.11.73, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

12. Minutes from staff meeting 01.10.73, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

13. Minutes from staff meeting 07.01.74, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

14. Minutes from staff meeting 14.10.75, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

15. Minutes from staff meeting 01.10.75, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

16. Minutes from staff meeting 08.10.75, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

17. Minutes from staff meeting 19.11.73, 03.12.73, 04.02.74, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

18. Minutes from staff meeting 19.11.73, 17.12.73, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

19. In the box “Teachers” Council’, in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

20. Photographs were found in the box ‘Diverse [Miscellaneous] 1974–1983ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

21. Practical information sheet for teachers, August 1976, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

22. Minutes from a staff seminar, undated. In the box ‘Building projects [Bygningssager] 1983–1986ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives. See also footnote 3.

23. Application letter to the municipality, 15.12.77, ‘Building projects [Bygningssager] 1983–1986ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

24. Information sheet for PLYS staff 21.04.76, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

25. Minutes from meeting about school objectives 27.04.73, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

26. Minutes from meeting about school objectives 27.04.73, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

27. Application letter to the municipality, 15.12.77, ‘Building projects [Bygningssager] 1983–1986ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

28. Application letter, 12.02.76, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

29. Minutes from staff meeting about school objectives 30.03.73, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

30. Minutes from staff meeting about school objectives 11.05.72, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

31. Minutes from staff meeting about school objectives 11.05.72, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

32. Minutes from staff meeting 19.12.72, box ’Fælleskonferencen 1973–1977ʹ in Peder Lykke School archive, stored at Copenhagen City Archives.

References

- Alterator, S., & Deed, C. (2018). School space and its occupation: Conceptualising and evaluating innovative learning environments. Boston: Brill Sense.

- Ballerup-Måløv-Kommune. (1972). Rapport nr. 2 om skoler med åben plan: Højagerskolen og Rugvængets skole. Ballerup-Måløv Kommune: Ballerup-Måløv Kommune.

- Ballerup-Måløv-Kommune. (1973). Rapport nr. 3 om skoler med åben plan: På grundlag af materiale fremlagt på Højager-konferencen 1972. Ballerup-Måløv kommune: Ballerup-Måløv kommune.

- Barad, K. (2003). Posthumanist performativity: Toward an understanding of how matter comes to matter. Signs, 28(3), 801–831.

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Barad, K. (2014). Diffracting diffraction: Cutting together-apart. Parallax, 20(3), 168–187.

- Bellfield, T., Burke, C., Cullinan, D., Dyer, E., & Szynalska McAleavey, K. (2018). Creative discipline in education and architecture: Story of a school. In I. Grosvenor & L. R. Rasmussen (Eds.), Making education: Material school design and educational governance. Educational governance research. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG, 119-136.

- Bertelsen, E., & Rasmussen, L. R. (2018). Skoler til fremtiden: At bygge rum der forandrer. In M. Martinussen & K. Larsen (Eds.), Materialitet og læring (pp. 187–210). København: Hans Reitzels Forlag.

- Blackmore, J., Bateman, D., Loughlin, J., O’Mara, J., & Aranda, G. (2011). Research into the connection between built learning spaces and student outcomes. Literature Review.

- Bøjer, B. H. (2019). Unlocking Learning Spaces: An examination of the interplay between the design of learning spaces and pedagogical practices. (PhD). Institute of Visual DesignThe Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation, Copenhagen.

- Braster, S., Grosvenor, I., & Del Mar Del Pozo Andres, M. (2012). Opening the black box of schooling. Methods, meanings and mysteries. In S. Braster, I. Grosvenor, & M. Del Mar Del Pozo Andres (Eds.), The black box of schooling: A cultural history of the classroom. Brussels: P.I.E. Peter Lang, 9-18.

- Burke, C. (2007). Editorial. History of Education: The Body of the Schoolchild in the History of Education, 36(2), 165–171.

- Burke, C., Cunningham, P., & Grosvenor, I. (2010). ‘Putting education in its place’: Space, place and materialities in the history of education. History of Education, 39(6), 677–680.

- Burke, C., & Grosvenor, I. (2008). School. London: Reaktion.

- Burke, C., & Grosvenor, I. (2011). The hearing school: An exploration of sound and listening in the modern school. Paedagogica Historica, 47(3), 323–340.

- Byers, T., Mahat, M., Liu, K., Knock, A., & Imms, W. (2018). Systematic review of the effects of learning environments on student learning outcomes. Melbourne: University of Melbourne, LEaRN.

- Coninck-Smith, N. D. (2017). Making schools and thinking through materialities: Denmark 1890–1960. In K. Darian-Smith & J. Willis (Eds.), Designing schools: Space, place and pedagogy (pp. 113–131). London: Routledge, 113-131.

- Coninck-Smith, N. D., Rasmussen, L. R., & Vyff, I. C. (2015). Da skolen blev alles: Tiden efter 1970. Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

- Crang, M., & Thrift, N. (2000). Thinking space. London: Routledge.

- Daniels, H., Tse, H. M., Stables, A., & Cox, S. (2018). School design matters. In H. M. Tse, H. Daniels, A. Stables, & S. Cox (Eds.), Designing buildings for the future of schooling. contemporary visions for education (pp. 41–65). London: Routledge.

- Darian-Smith, K. & Willis, J. (Eds.) (2017). Designing schools: Space, place and pedagogy. London: Routledge.

- Darian-Smith, K. (2017). Noisy classrooms and the “quiet corner”: The modern school, sound and the senses. In J. Damousi & P. Hamilton (Eds.), A cultural history of sound, memory, and the senses. New York, NY: Routledge, 71-89.

- Dovey, K., & Fisher, K. (2014). Designing for adaptation: The school as socio-spatial assemblage. The Journal of Architecture, 19(1), 43–63.

- Egelund, N., Hegner Christiansen, J., & Kleis, B. (2005). Skole-erfaringer. Arkitekten, Årg, 107(3), 26–28.

- Ellis, R. A., & Goodyear, P. (Eds.). (2018). Spaces of teaching and learning integrating perspectives on research and practice (1st ed. 2018 ed.). Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Fnu, S. (1975). Peder Lykke Skolen, København. Arkitekter: P. Hougaard Nielsen & C.J. Nørgaard Pedersen. Arkitektur, Årg., 19(5), 190–197.

- Fog, T. A., Herlak, E., Schack, T. H., & Schack, T. H. (1982a). Indskoling i åben plan miljø på Peder Lykke Skolen. Kbh.

- Fog, T. A., Herlak, E., Schack, T. H., & Schack, T. H. (1982b). Samarbejde i åben plan miljø på Peder Lykke Skolen. Kbh.

- Gershon, W. S. (2018). Sound Curriculum: Sonic Studies in Educational Theory, Method, & Practice. London: Routledge.

- Gislason, N. (2018). School space and its occupation: Conceptualising and evaluating innovative learning environments. (S. Alterator & C. Deed, Eds.). Boston: Brill Sense.

- Gjerløff, A. K., Jacobsen, A. F., Nørgaard, E., & Ydesen, C. (2014). Da skolen blev sin egen: Dansk skolehistorie 1920–1970. Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

- Glasser, W. (1969). Schools without failure. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Gleason, M. (2018). Metaphor, materiality, and method: The central role of embodiment in the history of education. Paedagogica Historica: Special Issue: Education and the Body, 54(1–2), 4–19.

- Gould, D. B. (2009). Moving politics: Emotion and ACT UP’s fight against AIDS. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Grosvenor, I., & Rasmussen, L. R. (2018a). Making education: Governance by design. In I. Grosvenor & L. R. Rasmussen (Eds.), Making education. Material school deign and educational governance. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG, 1-30.

- Grosvenor, I., & Rasmussen, L. R. (Eds.). (2018b). Making education. Material school design and educational governance. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG.

- Hansen, J. P. F., Fog, T., & Alleslev, S. F. (Eds.). (1998). Peder Lykke Skolen: 25 års jubilæum. Kbh.: Peder Lykke Skolen.

- Higgins, S., Hall, E., Wall, K., Woolner, P., & McCaughey, C. (2005). The impact of school environments: A literature review. London: Design Council.

- Holst, N. (1971). Om skolebyggeri og skoleindretning: Nogle pædagogiske problemer og muligheder ved nybyggeri og modernisering af folkeskoler (2 ed.). København: Gyldendal.

- Ingold, T. (2013). Making: Anthropology, archaeology, art and architecture. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Juelskjær, M. (2014). Changing the organization: Architecture and stories as material-discursive practices of producing “schools for the future”. Tamara Journal of Critical Organisation Inquiry, 12(2), 25.

- Könings, K. D., Bovill, C., & Woolner, P. (2017). Towards an interdisciplinary model of practice for participatory building design in education. European Journal of Education, 52(3), 306–317.

- Kromann-Andersen, E. (1994). Åben-plan skoler - fortid og fremtid. Uddannelseshistorie, 28, 73–88.

- Lawn, M., & Grosvenor, I. (2005). Materialities of schooling: Design, technology, objects, routines. Oxford: Symposium Books.

- Lefebvre, H. (2005). Rhythmanalysis: Space, time, and everyday life. London: Continuum.

- Logan, C. (2017). Open shut them. In K. Darian-Smith & J. Willis (Eds.), Designing schools: Space, place and pedagogy (pp. 83–96). London, New York, NY: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Mulcahy, D., Cleveland, B., & Aberton, H. (2015). Learning spaces and pedagogic change: Envisioned, enacted and experienced. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 23(4), 575–595.

- Nørgaard Pedersen, C. J. (1973). Om de åbne muligheder. Arkitekten, 75(1), 2–11.

- Ogata, A. F. (2008). Building for learning in postwar American elementary schools. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 67(4), 562–591.

- Olsen, P., & Holst, N. (2001). Ny skole i gamle bygninger. Vejle: Kroghs Forlag.

- Rabøl Hansen, V. (1973). Åben-plan skolen. Kbh.: Folkeskolens Forsøgsråd.

- Rathbone, C. H. (1971). Open education. The informal classroom: A selection of readings that examine the practices and principles of the British infant schools and their American counterparts. N.Y: Citation Press.

- Rathbone, C. H. (1972). Examining the open education classroom. The School Review, 80(4), 521–549.

- Schack, T. H. (1979). Åben-plan skolen. In P. Svendsen (Ed.), Skolemiljø: En håndbog om skolens fysiske miljø (pp. 90–97). Kbh.: Suenson.

- Silberman, C. E. (1973). The open classroom reader. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

- Tamboukou, M. (2014). Archival research: Unravelling space/time/matter entanglements and fragments. Qualitative Research, 14(5), 617–633.

- Tamboukou, M. (2019). New materialisms in the archive: In the mode of an œuvre à faire’. Mai: Feminism and Visual Culture.

- Verbruggen, C., & Carlie, J. (2009). An entangled history of ideas and ideals: Feminism, social and educational reform in children’s libraries in Belgium before the First World War. Paedagogica Historica, 45(3), 291–308.

- Verstraete, P., & Hoegaerts, J. (2017). Educational soundscapes: Tuning in to sounds and silences in the history of education. Paedagogica Historica: Themed Issue: Educational Soundscapes: Sounds and Silences in the History of Education, 53(5), 491–497.

- Werner, M., & Zimmermann, B. (2006). Beyond comparison: Histoire Croisée and the challenge of reflexivity. History and Theory, 45(1), 30–50.

- Woolner, P. (2015). School design together. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge.