ABSTRACT

In this paper, we investigate how elite coaches reflect on their practice and interact with each other, as part of their informal professional development. We use observations of 14 coach meetings, over a period of two years, where coaches came together to share their experiences of coaching elite athletics, and to discuss ways for continuous professional development. Through an action research approach, data collected included notes and audio-recorded conversations. The theory of practice architectures was employed as a theoretical tool to frame the analysis of the data in order to understand the meeting practices and how these practices were enabled and constrained. The research revealed how conversations led to awareness, which became turning points for new practices. Specifically, the coaches became aware of the importance of belonging to a community, their lack of knowledge and understanding of inequality, and the complexity of coaching. The meetings, as forums for dialogic practice, were enabled by open-minded collaboration, a willingness to share experiences, and a mutual understanding of the coaching context, but they were also constrained by the structures of coaches’ athletics clubs and federations, that do not fully support coaches’ meetings as an informal educational practice for professional development.

Introduction

Most professional development regarding coaches knowledge of technical skills, tactical skills and holistic coaching approaches take place informally in meetings with peers, rather than more formal education settings (Walker, Thomas, & Driska, Citation2018). For elite coaches in particular, interaction with other coaches is essential, as their professional development is individual, specific, and hard to formalise (Irwin, Hanton, & Kerwin, Citation2004). Coaches’ informal learning is considered a lifelong process, in that it allows them to gain knowledge in an environment where coaches unconditionally exchange experiences, but without a primal purpose of learning (Cushion et al., Citation2010). Coaches often exchange experiences in the form of organised meetings with other coaches where they can reflect on their individual coaching, understanding, and knowledge (Gilbert & Trudel, Citation2005, Citation2001; Ollis & Sproule, Citation2007). Furthermore, engagement in critical reflection among coaches can increase their understanding of the complex role they have in balancing athletes’ health, well-being, and performance (Côté & Gilbert, Citation2009; Cushion, Armour, & Jones, Citation2003; Gilbert & Trudel, Citation2005; Jones, Morgan, & Harris, Citation2012). However, these practices are not always considered as formal education as they are not institutionalised or part of a hierarchically structured education system (Walker et al., Citation2018).

A systematic review on learning and sports coaches showed that most informal learning for coaches takes place through reflective dialogue with other coaches (Walker et al., Citation2018). However, most examples in the research literature are from the individual coaches’ perspective and do not consider how coaches’ reflection in organised meetings is enabled and constrained, or their own or other coaches long-term professional development (Cushion et al., Citation2010; Irwin et al., Citation2004; Mallett, Rynne, & Billett, Citation2016). That is, organised coach meetings are common and important for coaches’ professional development, but they are rarely examined as an educative practice (Walker et al., Citation2018). In this article, we attempt to address this gap in the literature by reporting on elite coaches’ reflections during meetings over a period of two years, in order to understand what enabled and constrained the organised meeting practices. Two specific research questions guide this article: 1) In what ways did coaches’ discussions influence changes in the practice of meetings? and 2) How do the practice architectures enable and constrain practices of coach meetings? These questions require a theoretical resource – the theory of practice architectures, to understand the practice of coaches’ meeting, and an analytical resource to reveal the conditions of their practices, as well as a transformational resource to find ways to ensure the practices are productive and sustainable (Kemmis et al., Citation2014).

Professional development by critical reflection in Swedish elite sport

This study contains data from elite athletic coaches in Gothenburg, Sweden. In 2015, the Gothenburg Athletics Federation (GAF) initiated a collaboration with researchers at the University of Gothenburg as a way to create more sustainable elite sport by improving the coaches’ professional development. Sustainability as a concept in elite sport is based on coaches and athletes striving to improve both performance and wellbeing. Sustainability also means having a view of sports that is characterised by a process focus, participation and unpredictability (Dohlsten, Barker-Ruchti, & Lindgren, Citation2020). In the pursuit of performance, usually athletes push themselves to the limit of their physical and mental ability, which can lead to both physical and mental ill health. In recent years, several studies have shown that there are ways to reduce the negative consequences and to promote sustainability in elite sports, including when coaches focus on caring, responsibility, respect, and diversity, as opposed to only on elite athletes’ performance (Barker-Ruchti, Barker, & Annerstedt, Citation2014; Dohlsten, Barker-Ruchti, & Lindgren, Citation2018; Lindgren & Barker-Ruchti, Citation2017).

Many sports federations provide formal education for coaches with a focus on technical and tactical approaches in the given sport (Nash & Sproule, Citation2012; Werthner & Trudel, Citation2006). However, an increasing number of scholars suggest that formal education programmes insufficiently address social, pedagogical and holistic approaches, and that formal education ignores the increasingly complex site-based work of elite coaches (Hardman & Jones, Citation2011; Hardman, Jones, & Jones, Citation2010; Standal & Hemmestad, Citation2011).

In Sweden, athletics lacks an organised coach recruitment system, education regarding the complexity of elite coaching, and professional practice development (Fahlström, Glemme, Hageskog, Kenttä, & Linnér, Citation2013; Fahlström, Glemne, & Linnér, Citation2016; Henriksen, Stambulova, & Roessler, Citation2010), and Swedish coaches’ main source of information and knowledge comes from sharing experiences with other coaches (Cushion et al., Citation2010; Fahlström et al., Citation2013). Scholars also report that research is rarely used to help coaches professional development, and there is a need to encourage coaches to make use of their experience, and at the same time create forums for criticism and reflection, which is more challenging (Fahlström et al., Citation2013, Citation2016). However, coaching professional development is complex, and there are some specific factors that are crucial for the success of coaches and athletes, so it is important that coaches engage in professional learning opportunities that include space for critical discussion and challenging development (Fahlström et al., Citation2013, Citation2016).

In partnership with a university-based researcher, the GAF committed to a focus on increasing elite coaches’ professional development utilising critical reflections, as they collectively recognised that coaches’ knowledge and experience are crucial factors to create more sustainable elite sport practices (Annerstedt & Lindgren, Citation2014; Barker-Ruchti et al., Citation2014; Grahn, Citation2014). To this end the GAF employed a researcher (in this instance a doctoral student) in sports science, with experience of elite coaching, to lead an action research project together with the elite coaches. The coaches included in the project were expected to become critically reflective practitioners in order to gain new insights and contribute to the quest to become Sweden’s most attractive athletics environment. The action research project community included university researchers and coaches at the elite level. Initially, to ensure the effective functioning of the professional community, it was necessary to discuss the different expectations and roles of the elite coaches in research, but also the researchers’ presence in the meetings and their role in summarising reflections and follow up actions. Thus, the researchers participated in the organised meetings to support and facilitate the coaches’ reflective action research processes and professional learning. This enabled all participants to jointly, while adopting different perspectives, challenge one’s own given thinking and adopt critical reflection.

Theoretical framework

Drawing on (Schatzki, Citation2002), we use a theory of practice to explore how the coaches understand their actions, relate to each other and conceptualise their own coaching through practical understandings, and the formulation of sets of knowledge that bring order and values to their activities. Although practice theory is rarely used by scholars studying the professional practices of coaches, it has been used in contexts such as leading in education (Edwards-Groves & Rönnerman, Citation2013; Grootenboer, Edwards-Groves, & Rönnerman, Citation2014; Salo, Nylund, & Stjernstrøm, Citation2015; Wilkinson & Kemmis, Citation2015). The practices of, for example, coach meetings are also shaped by the general understanding of the context (Schatzki, Citation2002). By examining organised meetings of coaches as a practice, practice theory provides useful insights into how the local conditions and arrangements enable and constrain the possibilities for coaches’ professional development and growth (Kemmis et al., Citation2014).

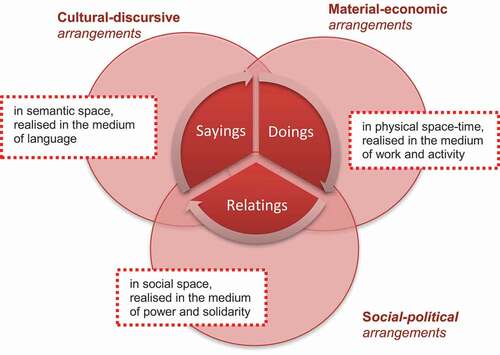

Practices are constituted in sayings, doings, and relatings (Kemmis & Grootenboer, Citation2008). Sayings refer to forms of understanding that take expression in language. Doings refer to modes of actions that take place in activity and work, while relatings refer to different ways of relatings to one another and to things. (Kemmis et al., Citation2014). In practices, all three occur simultaneously and are interconnect and interdependent (Kemmis & Grootenboer, Citation2008). Furthermore, practices are enabled and constrained by local conditions and arrangements – “practice architectures”, that hold the practice in place (Kemmis, Citation2014). These practice architectures prefigure the practice in three inter-related dimensions: cultural-discursive arrangements, material-economic arrangements, and social-political arrangements, which shape and are shaped by the practices in the site.

Practice architectures of coach meetings

The theory of practice architectures aims “to allow researchers to characterize how practices are enabled and constrained by particular practice architectures” (Edwards-Groves & Kemmis, Citation2015, p. 87), and so reveal the requirements and arrangements that can develop and change specific practices. In this paper, we use the theory to reflect upon, and understand the practice architectures that enabled and constrained the practices of coaches’ meetings – the sayings, doings, and relatings of the meeting practices as they unfolded in time-space. Furthermore, the sayings, doings and relatings of a practice are realised in intersubjective space (Kemmis et al., Citation2014). The corresponding three intersubjective spaces existing in language, the material world, and in social relationships (Kemmis, Citation2009) (see ). Specifically, the cultural-discursive arrangements enable and constrain the coaches’ sayings, such as the language and shared discourse of knowledge of elite coaching. The material-economic arrangements enable and constrain coaches’ doings in the material world such as time and space to meet one another for sharing experiences. And finally, the social-political arrangements enable and constrain relatings in the medium of solidarity and power, such as the relationship among coaches themselves and their leader (Kemmis et al., Citation2014).

Figure 1. The media and spaces in which sayings, doings, and relating exist, from Kemmis et al. (Citation2014, p. 34)

Methodology

In this study, we use an action research design. Action research aims to understand and change practitioners’ practices and the site-based conditions that enable and constrain them (Kemmis, Citation2009). Action research also includes the practitioners as co-participants in the study, and the results from the action research aim to realise new practices and associated practice architectures (Rönnerman, Citation2004). Furthermore, action research requires both collaboration and reflection in and on practices and gathers data in practice to generate knowledge to change the practices in on an ongoing and sustainable basis. In addition, action research requires practitioners to inquire into their own practices and is by nature participatory (Wallace, Citation1987). That is, the action research is to promote change derived from and responsive to the participants’ commonly addressed ideas and concerns, grounded firmly in their experiences. The process can be seen as a cycle where practitioners discuss dilemmas, plan a response, and then act, while collected evidence of the impact of the change to then inform reflective consideration of the response, which in turn informs a revised understanding of the dilemma, and so the cycle begins again (Carr & Kemmis, Citation1986). However, action research is mostly connected to projects of change and in this study, we concentrate on the conversations among the coaches to study how they change their knowing of being a coach. Thus, action research is not simply a cyclic sequence of processes, but it is also a critical approach to evidence-based professional development, which is the focus of this study. In other words, here it has the potential to generate knowledge that can specifically affect and develop coaches and their coaching practices (Ollis & Sproule, Citation2007), and it can simultaneously contribute to coaches’ practical or theoretical learning, through the collaboration between researchers and coaches (Trudel & Gilbert, Citation2006). In this study, the researcher participated in all the coaches’ meetings in the role of a facilitator with the aim of bringing back preliminary analyses to the group to reflect on further and to inform their subsequent development.

Participants

In 2015, the GAF had 27 elite coaches, in 2016, 30 elite coaches, and in 2017, 26 elite coaches. A total of 17 coaches volunteered to participate in this study (). The criteria for being an elite coach in GAF are based on their athletes’ results, which also determine the levels of financial support. Financial support is based on the athlete’s performance and is divided into four categories (“A-D level”). “A level” coaches have athletes at European championship level. “B level” coaches have athletes on the Swedish national teams. “C level” coaches have athletes ranked in the top three at the Swedish Championships. “D level” coaches have athletes who ranked 4–6 place in competitions at the Swedish Championship level. One of these elite coaches was female.

Table 1. Elite coaches’ financial support level

Ethical considerations

The Regional Ethics Review Board approved this study (Dnr. 875–15), and the research followed the ethical principles set by the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet, Citation2017). The coaches were asked to read and sign consent forms before the research project started, where they signalled that they understood their rights and the voluntary nature of participation. They were also informed that the collected information would be handled confidentially. To secure confidentiality, all coaches were given pseudonyms and no specific athletics disciplines are identified. Furthermore, the coaches’ work methods and training plans have been protected and are only revealed to the extent that the coaches allow. The coaches volunteered to participate and were informed that they could withdraw their participation at any time without a specific explanation or consequences for their role as an elite coach in GAF. The project itself was funded by GAF but was been conducted independently, from the GAF governing board, by the researcher.

Data production

Throughout the study the coaches met for conversations every two months in season. Each meeting was built on the other in a way to keep a process of the reflective dialogue and interaction derived from their experiences. The coaches and the researcher participated in the meetings where the discussions were focusing on coaches’ professional development, the role of elite coaches and the conditions for coaching elite athletes in the area. Each meeting started with a discussion of their coaching and sharing their experiences. Every meeting concluded with a case presented by a coach, which provided a tangible coaching account for reflection and dialogue at the next meeting. This case story was sent to all participants by email afterwards to promote reflection to inform the conversation at the next meeting.

Apart from two meetings that were held in a public space (restaurants), the researcher audio recorded the meetings (saved as audio files) that were held in a conference room at the training area, chosen by the coaches. The researcher facilitated the meetings and took notes to track the processes and to keep a record of who participated, present topics, and future requests or ideas. In total, the coaches met 14 times between August 2015 and August 2017, and the number of participants at each meeting varied between four and 17. The meetings were held every other month during pre- and post-outdoor athletics season. At the first meeting, a consultant was hired to present activities that encouraged the coaches to participate in the meetings actively. The GAF manager was a silent observer at two meetings where the coaches discussed structural changes. The meetings lasted between 90 and 140 minutes and were organised by GAF staff, but the coaches chose the content. The content focused on topics like injury prevention, support systems for athletes and coaches, organisational changes in their common facility, coaches and athletes’ needs, education and coaching competencies, coach–athlete relationships, and training routines. During the first year, the coaches suggested complementing the meetings with a yearly conference two months before the start of the indoor competition season for athletics.Footnote1 As all coaches could not attend on all of the meetings, the coaches suggested that the conference with all coaches should be a forum to discuss changes and possibilities for sharing experience and new approaches of coaching knowledge such as lectures or workshops.

Data analysis

The analysis of the data followed a discourse analysis approach over four phases (Carbó, Andrea Vázquez Ahumada, Caballero, Lezama Argüelles, & Drisko, Citation2016). After reading the transcripts carefully several times, the transcripts were coded as we looked for patterns, variability, and differences in the content in each meeting which provided indications to turning points overtime. There were four meetings (spread over two years) that were identified as having three significant turning points due to the changes in the meeting practices that were made during the action research process (). Each one of the meetings resulted in new actions that changed the practice of coach meeting in Gothenburg athletics.

Table 2. Example of analysis guided by sayings, doings and relatings

These four meetings were selected to be analysed in more depth, guided by sayings, doings and relatings, based on coaches’ expressions (Kemmis, Citation2009). In the next step, the data analysis focused on how the intersubjective spaces enabled and constrained actions that lead to change (turning points). For example, the coaches’ reflection (sayings) lead to an awareness of knowledge gaps. By interacting together (relatings), regardless of individual experience, they could speak about the role of coaching elite athletes, which lead to a consensus that they as coaches need more knowledge of pedagogical and sociological perspectives regarding elite sport development. This stage then revealed consequences for the coach’s meetings (), by the action of initiating a formal coaching education course for all the coaches.

Table 3. Examples of coach meetings that identified as turning points

In the last step of the analyses the theory of practice architectures was used to examine what ways meeting practices were enabled and constrained. For example, the material-economic arrangements such as time and place prefigured the meetings, which enabled the practice to take place and evolve, but unequal terms for different coaches also constrained the practice, as all coaches could not participate at all times. Within the process, the coaches initiate new actions, such a yearly conference to enable all coaches to attend at the same time. Needless to say, the arrangements are only analytically separable. In practice, they are all intertwined.

Findings

The findings are presented in two sections. In the first section, the data from the coach meetings are presented to provide the context-specific content of how coaches’ reflections influenced changes over time in the practices, which we have called turning points. The second section shows how the practice architectures enabled and constrained the coach meeting practices. Due to ethical concerns, quotations are anonymised and marked with a parenthesis to track the different voices (example Coach 1).

Collaboration created awareness of the importance of community

The findings show that coaching elite athletes is often a one-person job, and the coaches described the coaching job as lonely. They talked about how sharing experiences enabled them to support each other, with not only coaching specific input and knowledge but also as colleagues who understood the pressure of being a coach, better than someone outside of elite coaching. At the second coach meeting in November 2015 (), the coaches reflected on the need of having an elite coaches’ community, which is illustrated by the group discussion in following excerpts:

Whether we want or not, we inspire each other. And I think we can get even better. It’s good that there are different types of communication between training groups and coaches. And there is indeed a community where we can develop. And I think that has been good for me. I also think we can get a lot better at it. (Coach 1)

You are quite lonely as a coach. If you are doing well, everything is great. But when it’s going bad then […] so I think it’s important that we meet and support each other. Asking ‘how is the situation’ or ‘are you doing well’. That we coaches have a kind of network that supports each other a little. (Coach 3)

The topics discussed during the first sessions related to how coaches felt regarding their job as a coach. As the excerpt above shows, the coaches’ main intentions to meet was to support each other in the role as coaches. By confirming their thoughts on their pressured situation as a coach, the sayings about what constitutes the practice of coach meetings enabled the coaches to frame new conditions and relatings in the social space through sharing experiences (Kemmis & Grootenboer, Citation2008).

The coaches also agreed that the meetings should include opportunities to exchange experiences as that did inspire them to continue to work with their learning. At the same coach meeting (November 2015), the coaches discussed that they wanted to collaborate more spontaneously outside the coach meetings to share their opinions and discuss their daily coaching dilemmas:

I miss a forum where you can discuss spontaneously. Where you can hear the opinions of others. If I read something interesting, I want to talk about it. I do not want to wait three weeks for the next meeting. Like a coffee break where you can meet and talk. (Coach 14)

I have a network where I share and address issues of leadership and coaching. However, it is more out in Sweden than in Gothenburg. It’s lonely to be a coach. You need support. (Coach 3)

I like what [coach 14] says about coffee break. You should not underestimate it. Just sit down and chat. (Coach 15)

The excerpt above shows that the coaches consider a need for the coaches to reflect-on-action (Gilbert & Trudel, Citation2001), and that organised meetings can constrain some coaches. These meetings were however, only for coaches with financial support and the coaches expressed a desire to include all coaches irrespective of the level of support the coaches receive. They believed that input from, and collaboration with, different coaches was essential for their learning regardless of level of the athletes. The coaches noted that the coach meetings provided them with the opportunity to collaborate and support one another in managing the stress of coaching. A critical perspective of coach learning is reflective conversations on new aspects of coaching (Gilbert & Trudel, Citation2005). With coaches’ interactions and openness in the social intersubjective space (Kemmis & Grootenboer, Citation2008), the coach meetings assisted new relationships and collegial support.

During the coach meeting in November 2015, the coaches also discussed that even though they needed each other’s support, their job is based on performance, and ultimately, they are competitors:

It’s not that easy. We work together. But on the competition, we must go against each other as well. It’s a dilemma. Should I share all my stuff with you for you to win over me? Sometimes it’s a dilemma for me. We are friends we work together, but one day at the Championship, then we are opponents. (Coach 14)

Yes, it’s in the nature of sports. (Coach 3)

Yes, but they might as well be in the same training group. (Coach 10)

Although some of the coaches were competitors, they agreed that their shared experiences over athletics discipline boundaries were more beneficial to them than not to include all coaches. The coaches’ expressions were consistent with findings from research regarding informal coach learning (Côté, Citation2006), as they reflected on how the coach meetings supported them to communicate with coaches from different disciplines, which is often not possible during a daily coaching routine. By reflecting together, they came to terms with the fact that the learning process could be enhanced with more coaches participating in the practice, and the coach meetings in November 2015 ended with a group coming to a mutual agreement to encourage more coaches to attend the meetings:

I feel inspired, partly to see what’s going to happen now and partly to create more togetherness. Where can this lead and what can happen in the future? (Coach 1)

Today I thought it was good. The last meeting there were maybe six coaches who talked and now everyone has got a lot more room to express themselves. That’s good. And if we continue with more coaching reflections from our experiences with the athletes, I think it will be even better. Then we can take with us what is said today and get better. (Coach 8)

It’s great and good for us who are here. Then it’s good for us and the environment if more coaches want to join. I think that it’s our duty to bring them. (Coach 2)

I can send out a list of those who have elite support so you can talk to the other coaches. (Coach 8)

Reflections created awareness of knowledge gaps

The findings show that the coaches’ collaboration and shared experiences were considered valuable. By sharing their experiences and discussing their role, they discovered that different coaches had different responsibilities and clubs did not provide any guidelines for this. The coaches also said that they lacked knowledge in psychology, physiology, and pedagogy. The coaches discussed coaching philosophy and confirmed in line with Cushion et al. (Citation2010) that experiences from their careers as athletes or other coaches were their primary source of information. At the fifth coach meeting in April 2016 (), the coaches discussed that many coaches often lack coaching knowledge based on evidence, as Coach 8 expressed:

What we require is an explicit pedagogy about how to proceed. I think that is all missing. It’s a bit too much this tradition that we do as we always did. And it does not work. We need more knowledge at the individual level and see what the people need.

The coaches discussed that they need more competencies in pedagogy and psychology, as the coaches’ education lacks content about what elite coaches need beyond technical and physical training. In general, most coaches, including those in this research, experience that they learn informally, rather than formally (Cushion et al., Citation2010; Walker et al., Citation2018). However, the coaches expressed that both informal and formal learning processes are essential to increase their knowledge.

There was a difference in how the coaches experienced the meeting practice compared to formal learning in the form of an educational course, particularly as they encountered some obstacles in participating in formal education. On the one hand, the coaches expressed that it would be beneficial if the GAF could provide more formal education by giving the coaches a solid foundation of knowledge in pedagogy and psychology. On the other hand, they discussed that some coaches were not willing to participate in formal education because it takes too much of their time outside their coaching. Furthermore, they expressed that participating in the coach meetings instead should be mandatory. In the same coach meeting (April 2016) Coach 5 concluded a discussion by saying:

My view is that we have very much experience right from the start, but we have a fairly low level of education. But we have succeeded, nonetheless. What I think, and what I miss, is much of the scientific part. Perhaps we arrange an elite course, maybe a pedagogy course. Exercise, Philosophy, Psychology. Then I think we can improve because we have experience in Gothenburg but not the formal knowledge. Then we can help those who are “up and coming”. Training is offered so that coaches get a good knowledge base.

Sharing experiences created awareness of inequality and complexity

The findings show that coaches’ regular meetings created opportunities for them to learn how to reflect, which is consistent with other research findings (Cushion et al., Citation2003; Gilbert & Trudel, Citation2005, Citation2001). The findings also show that reflecting together created a sense of community, which can be crucial for coaches when they develop more sustainable elite sport (Dohlsten et al., Citation2018). However, some experienced coaches with valuable knowledge were excluded from the project because their athletes were not currently ranked in the top six nationally. The participating coaches expressed that input from different coaches was essential for collaboration, not the “official” designated coaching level. Moreover, the coaches talked about how to change the conditions and structures to benefit the entire elite athletics environment. Specifically, the coaches discussed that it was unfair that they all received the same financial support regardless of how many athletes they were coaching, as it is harder to work with more athletes at an elite level compared to just one athlete. This was highlighted at the eighth coach meeting in November 2016 (), in a group discussion:

It’s very strange that coaches do not receive more support to coach more athletes. Several of you coach more elite athletes, and yet you only receive financial support for one athlete. That is a strange distribution. (Coach 15)

Coaches should get support for all elite athletes. There may be a limit and coaches in any case receive support for three athletes at least. That if you have three athletes in the elite group, then you get support for three. (Coach 2)

Yes, that coaches benefit if they coach several elite athletes. It sounds interesting. (Coach 1)

The findings show that financial support was important to enable coaches to participate in the practices of meeting. However, they also said that they all became coaches without receiving any financial support and that they probably would coach regardless of the money. Instead, they discussed that coach learning is not just about the environment, but also cognitive as it is based on the individual drive to become better rather than on systems or structures. In the same coach meeting (November 2016), Coach 14 expressed this in the following:

I think, though, yes, it’s about money, but not just the money. We who are sitting here would probably sit here anyway, no matter what happens to the money. I think, however, that commitment is the most important thing. Money is important, no question about that but […] I think that regardless of how we coach, we have found a way to live this dream or reach our goal.

In summary, data from the coach meetings show how the three turning points turned out in the discussions, and they were all about awareness. First, the awareness of belonging to a community, second, the awareness of knowledge gaps and third the awareness of inequality and complexity. During the 14th meeting in August 2017, the coaches discussed that everyone should have the chance to participate. It was still unclear which coaches could regularly join, as the coaches worked different hours and with varying rates of employment. In the following excerpt, the coaches negotiated how they should handle the issue:

It’s perfect if we have the meetings in the morning, it helps a lot. (Coach 1)

But, if we have morning meetings, we exclude people. (Coach 2)

If we have it in the morning, people can’t come because they have to take time off from work. However, if we have it in the evening, then I have to take time off from work. (Coach 1)

Maybe we can have slightly varied times at least. (Coach 6)

Yes, but then there will be somewhat different constellations then. It can be useful. The most important thing is that as many people as possible get a chance to participate. (Coach 8)

The coaches decided to split the meeting into new groups. Full-time coaches participated in the morning meetings, and part-time coaches participated in the evening meetings. The action research, with continues reflection and action, began a new cycle beyond the framework of the research project. The coach meetings continued as a practice, without the researcher, and the coaches themselves and staff from the GAF then facilitated the meetings on forward. Due to limited time, the answer to how this was played out or consequences of this change is not included.

In the next section the meetings will be analysed from the lens of the theory of practice architectures to gain an understanding of how the meetings were enabled and constrained by the conditions and arrangements in the local site.

The practice architectures of the meetings

The three intersubjective spaces, existing in language, physical time-space, and in social relationships (Kemmis, Citation2009) constitute the conditions for coaches to establish meaningful learning through the coach meetings (). In the semantic space, the coaches established how they as coaches talked about coaching knowledge and their role as coaches. In the physical space-time, the practice was organised in different settings, times, and locations. In the social space, coaches related to each other, other practices, and content of their experience to make room for each coach to learn.

Table 4. How the practice architectures prefigure practices around coaching development

Coach meeting practices were enabled and constrained by cultural-discursive arrangements

The analysis of the first meeting of the project showed that seven coaches out of 14 expressed their thoughts and opinions and the other seven were very quiet. During the second meeting, an invited consultant introduced a new reflection technique that encouraged all attendants to actively participate. By reflecting together, it was hoped that more coaches could benefit from the experience and increase their opportunities of developing their coaching skills (Cushion et al., Citation2010).

However, the cultural-discursive arrangements were also constraining the practice, as there were no mutual understandings about their roles as coaches. In the first year of the coach meetings, the practice consisted of language related to collaboration and sharing knowledge. Nevertheless, it seems that the unclear definition of the role of coaching elite in athletics constrained the coaches as there were no outlines of what kind of knowledge they intended to develop or needed to share. During the process, they developed consensus on topics and competence that they all needed as coaches, which enabled the practice to evolve with new concepts and content of coaching, and this progress shows that collaboration and sharing experience is essential to develop as coaches in complex and unpredictable contexts. For example, the coaches expressed how certain language and attitudes constrained their ability to get their athletes to perform to their potential. They jointly paid attention to holistic ideas by accepting the complexity of their coaching job, which is important for coach professional development in regards to creating more sustainable elite sport for athletes (Dohlsten et al., Citation2018; Lindgren & Barker-Ruchti, Citation2017). Another example is that the coaches stated that they had a rather low level of education and suggested they needed more formal education. The coaches realised that they were constrained by the lack of formal expectations of elite coaches and the cultural-discursive arrangements enabled coaches to develop a consensus of what constitutes coaching knowledge and questioning their own level of knowledge.

Coach meeting practices were enabled and constrained by material-economic arrangements

The coach meetings were all voluntary, and both full-time coaches and part-time coaches participated outside their work hours. One reason for the uneven and irregular number of participants was framed by the material-economic arrangements that constrained the practice. The coaches were forced to prioritise athletes’ short-term result focus, rather than their own long-term professional development. The coaches needed that their athletes to perform at high levels in order to qualify for financial support; if the coaches’ athletes did not perform at a high level, then they would lose their status as an elite coach and miss out on opportunities to interact with other elite coaches. Notably, these conditions are common for elite coaches in Sweden (Fahlström et al., Citation2013). At the beginning, a rather high number of coaches participated. However, to create conditions for formal learning (Cushion et al., Citation2010), a two-day coaching conference, initiated by the coaches, took place outside the facility during a weekend to enable all coaches to participate in discussions.

The material-economic arrangements also constrained the practices of coach meetings as some coaches struggled to find time to participate. It appears that the clubs did not fully support the coaches´ meetings as a practice for coach learning by sharing experience. The meetings were not part of the coaches’ work descriptions and not included in their time schedule as elite coaches. For example, 18 months after the first coach meeting, the University of Gothenburg arranged an elite coaching course in collaboration with the GAF. In consultation with the coaches, the course featured lectures about sustainable issues related to sport medicine, sport psychology, injury prevention, and talent development from a pedagogical perspective. However, only four elite coaches attended the course. One reason for this was that the course took place outside their training facility, making them choose between education and a training session. Some coaches could not participate as the clubs demanded they take part in training, and some did not attend as their workload was too heavy. Notably, none of the coaches chose to finish the final exam, a result also noted in a similar Swedish educational athletics project (Fahlström et al., Citation2013). The findings indicate that informal coach meetings are essential for coach share experience and knowledge, as they are often not able to participate in formal education.

The coaches expressed that they could collaborate outside the meetings more spontaneously to share opinions and discuss coaching dilemmas. Therefore, the coaches agreed to have more spontaneous meetings outside the meeting practice as several coaches could not attend all meetings due to a lack of time. This solution complements the organisational way of creating meetings for coaches (Mallett et al., Citation2016). Another example of actions was the combined restaurant dinners and meetings so that more coaches could attend. Still, this constrained the practice as the meeting structure was adjusted to the environment and the coaches experienced these meetings primarily as a pleasant activity rather than as an educational opportunity. After two years, the coaches also suggested to split the coach meetings, one smaller group in the morning and one in the afternoon, to enable coaches to participate more often. This change of the material-economic arrangements of the practice enabled more coaches to participate and take part in coach meetings.

Coach meeting practices were enabled and constrained by social-political arrangements

The social-political arrangements of the practice enabled the coaches to share knowledge as they shared their experiences, received collegial support, and interacted with other coaches (Cushion et al., Citation2010). The coach meetings also lead to collaboration with university researchers. This was done to facilitate the coaches’ reflection on their new knowledge, as coaches’ structural reflection can contribute to their understanding and can be applied in practice (Ollis & Sproule, Citation2007). For example, after the first conference, the coaches chose to discuss financial and educational structures related to coaches’ individual perspectives on important skills. They began to reflect over the definition of elite coaching and the support they need to manage their jobs. The social-political arrangements of the practice enabled coaches to collaborate and develop through practical experience, which is often not possible in the formal coaching education (Jones, Armour, & Potrac, Citation2003). The coaches shared concerns regarding the uncertainty of their employments as it is based on their athletes’ performances. Hence, the social-political arrangements of the practice constrained the coaches’ chance of collaboration as the structures made by the clubs and federation did not fully support the coaches’ development through the coaching community.

Conclusions

This research raises an important issue regarding coaches organised meetings as a practice for professional development. Our findings demonstrate how the coaches’ reflections were shaped by cultural-discursive arrangements leading to awareness of how they were talking about their practice as a coach. The coaches’ reflection and interactions in the meeting practice increased so they were more willing to share their experiences, had a greater awareness of their need for a shared community, and that they had specific knowledge gaps. Furthermore, the findings demonstrate that the cultural-discursive arrangements of the meetings enabled the coaches to engage in a community forum where they could share their experiences and reflect collegially to generate new valuable knowledge (cf. Walker et al., Citation2018), meaning that the coach meeting served as an informal educational practice. However, the coaches’ awareness about their own coaching practices may have increased if the meetings was more related to scientific knowledge. For example, if the coaches could read and discuss research articles that contribute to their ability to articulate their complex reality or fulfil the requirements of the formal education course (see e.g. Rönnerman & Olin, Citation2014).

The practice architectures also constrained the meeting practice. The most obvious way was how the material-economic arrangements shaped the meetings, such as how time, space, and place constrained the meetings, regardless of structure. This may have been a consequence of the lack of cooperation and consensus between coaches and the clubs, but attention to these practice architectures may enable more productive learning for the coaches, given that the findings suggest that the clubs did not fully support the meetings as an essential forum for coaches’ professional development.

Moreover, the practice was shaped by social-political arrangements, such as unclear and unequal terms and conditions for coaching elite athletes. This can be seen as clear relations of power where the athletes’ performances were guiding who could take part in a community of sharing knowledge and experiences.

In light of these findings, a conclusion is that informal education in ways of sharing experiences matters for coaches’ professional development. However, to facilitate coaches’ professional development by action research, the researcher needs to contribute continuously to the process at different levels where the cultural-discursive, material-economic and socio-political arrangements are negotiated (cf. Aspfors, Pörn, Forsman, Salo, & Karlberg-Granlund, Citation2015). An important practical implication is, therefore, that the researcher needs to work and negotiate with both coaches, managers and stakeholders in both sports clubs and federations. Thus, we find the theory rich in implications for suggesting ideas to be taken into account when planning and construction of coaches’ further informal and formal education.

We postulate that action research is useful to gain an understanding of coaches’ professional development. Action research, as this study shows, can serve a purpose as informal education in organisations that lack structures and contextual education for coaches in sport. Given the importance to concretely configure and support the ensuing work with coaches’ professional development, further action research which includes managers in sports clubs and sports federations is also essential. Further research is also needed to understand how coaches’ professional development shape and are shaped concerning athletes, clubs and federations.

Acknowledgments

We especially thank the coaches who participated in the study, and are grateful to the GAF for its support. We thank the reviewers for their constructive feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

John Dohlsten

John Dohlstenis a Ph.D. at the Department of Food and Nutrition, and Sport Science, University of Gothenburg, Sweden. He has conducted research on coaching and participation in youth sport. His current research focus on sustainability from the perspective of both top-level coaches and elite athletes.

Karin Rönnerman

Karin Rönnerman is a professor Emerita in Education at the University of Gothenburg. Her research is in the field of action research connected to professional learning and development of practices through middle leading. In her research the theory of practice architecture is used both for analysing and for understanding changes of practices.

Eva-Carin Lindgren

Eva-Carin Lindgren is a professor at School of Social & Health Sciences, Halmstad University, Sweden. She has conducted both qualitative and intervention studies in the areas of health promotion (physical activity, body and empowerment) in school settings and sports in children and youths. Her current research interests focus on how coaches construct children’s team sports, how coaches maximise participation in youth sport, and how top-level coaches construct sustainable sport for elite athletes. She adopts perspectives of gender, intersectionality and health promotion.

Notes

1. Swedish athletics has two competition seasons, one is indoor during winter and the other one is outdoor during summer.

References

- Annerstedt, C., & Lindgren, E.-C. (2014). Caring as an important foundation in coaching for social sustainability: A case study of a successful Swedish coach in high-performance sport. Reflective Practice, 15(1), 27–39.

- Aspfors, J., Pörn, M., Forsman, L., Salo, P., & Karlberg-Granlund, G. (2015). The researcher as a negotiator – Exploring collaborative professional development projects with teachers. Education Inquiry, 6, 4.

- Barker-Ruchti, N., Barker, D., & Annerstedt, C. (2014). Techno-rational knowing and phronesis: The professional practice of one middle-distance running coach. Reflective Practice, 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2013.868794

- Carbó, P. A., Andrea Vázquez Ahumada, M., Caballero, A. D., Lezama Argüelles, G. A., & Drisko, J. W. (2016). “How do I do discourse analysis?” Teaching discourse analysis to novice researchers through a study of intimate partner gender violence among migrant women. Qualitative Social Work, 15(3), 363–379.

- Carr, W., & Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming critical: Education knowledge and action research. London: Falmer Press.

- Côté, J. (2006). The development of coaching knowledge. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 1(3), 6.

- Côté, J., & Gilbert, W. (2009). An integrative definition of coaching effectiveness and expertise. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 4(3), 307–323.

- Cushion, C. J., Armour, K., & Jones, R. L. (2003). Coach education and continuing professional development: Experience and learning to coach. Quest, 55(3), 215–230.

- Cushion, C. J., Armour, K., Lyle, J., Jones, R., Sandford, R., & O´Callaghan, C. (2010). Coach learning and development: A review of literature. Leeds: Sports Coach UK.

- Dohlsten, J., Barker-Ruchti, N., & Lindgren, E.-C. (2018). Caring as sustainable coaching in elite athletics: Benefits and challenges. Sports Coaching Review, 9(1), 48-70.

- Dohlsten, J., Barker-Ruchti, N., & Lindgren, E.-C. (2020). Sustainable elite sport: Swedish athletes’ voices of sustainability in athletics. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2020.1778062

- Edwards-Groves, C., & Kemmis, S. (2015). Pedagogy, education and Praxis: Understanding new forms of intersubjectivity through action research and practice theory. Educational Action Research, 1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2015.1076730

- Edwards-Groves, C., & Rönnerman, K. (2013). Generating leading practices through professional learning. Professional Development in Education, 39(1), 122–140.

- Fahlström, P. G., Glemme, M., Hageskog, C.-A., Kenttä, G., & Linnér, S. (2013). Coachteamet – En satsning på elitcoacher i svensk friidrott. Sweden: Växjö.

- Fahlström, P. G., Glemne, M., & Linnér, S. (2016). Goda idrottsliga utvecklingsmiljöer - En studie av miljöer som är framgångsrika i att utveckla elitidrottare. FoU Rapport, Riksidrottsförbundet, 2016, 1.

- Gilbert, W., & Trudel, P. (2001). Learning to coach through experience: Reflection in model youth sport coaches. Journal Of Teaching In Physical Education, 21(1), 16–34.

- Gilbert, W., & Trudel, P. (2005). Learning to coach through experience: Conditions that influence reflection. Physical Educator, 62(1), 32.

- Grahn, K. (2014). Alternative discourses in the coaching of high performance youth sport: Exploring language of sustainability. Reflective Practice, 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2013.868795

- Grootenboer, P., Edwards-Groves, C., & Rönnerman, K. (2014). Leading practice development: Voices from the middle. Professional Development in Education, 41(3), 1–19.

- Hardman, A., & Jones, C. (2011). The ethics of sports coaching. London: Routledge.

- Hardman, A., Jones, C., & Jones, R. (2010). Sports coaching, virtue ethics and emulation. Physical Education & Sport Pedagogy, 15(4), 345–359.

- Henriksen, K., Stambulova, N., & Roessler, K. K. (2010). Successful talent development in track and field: Considering the role of environment. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 20, 122–132.

- Irwin, G., Hanton, S., & Kerwin, D. (2004). Reflective practice and the origins of elite coaching knowledge. Reflective Practice, 5(3), 425–442.

- Jones, R., Morgan, K., & Harris, K. (2012). Developing coaching pedagogy: Seeking a better integration of theory and practice. Sport, Education and Society, 17(3), 313–329.

- Jones, R. L., Armour, K. M., & Potrac, P. (2003). Constructing expert knowledge: A case study of a top-level professional soccer coach. Sport, Education and Society, 8(2), 213–229.

- Kemmis, S. (2009). Action research: A practice-changing practice.Educational Action Research, 17(3), 313-331.

- Kemmis, S. (2014). The action research planner doing critical participatory action research. Singapore: Springer Singapore: Imprint: Springer.

- Kemmis, S., & Grootenboer, P. (2008). Situating Praxis in practice. In I. S. Kemmis & T. Smith (Red.), Enabling Praxis: Challenges for education (pp. 37–62). Amsterdam: Sense Publishing.

- Kemmis, S., Wilkinson, J., Edwards-Groves, C., Hardy, I., Grootenboer, P., & Bristol, L. (2014). Changing practices, changing education. Singapore: Springer.

- Lindgren, E.-C., & Barker-Ruchti, N. (2017). Balancing performance-based expectations with a holistic perspective on coaching: A qualitative study of Swedish women’s national football team coaches’ practice experiences. International Journal Of Qualitative Studies On Health And Well-Being, 12(1), 1358580.

- Mallett, C., Rynne, S., & Billett, S. (2016). Valued learning experiences of early career and experienced high-performance coaches. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 21(1), 89–104.

- Nash, C., & Sproule, J. (2012). Coaches perceptions of their coach education experience. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 43(1), 33–52.

- Ollis, S., & Sproule, J. (2007). Constructivist coaching and expertise development as action research. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 2(1), 1–14.

- Rönnerman, K. (2004). Vad är aktionsforskning? Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Rönnerman, K., & Olin, A. (2014). Research circles - Constructing a space for elaborating on being a teacher leader in preschools. In K. Rönnerman & P. Salo (Eds.), Lost in practice: Transforming nordic educational action research (pp. 95–112). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Salo, P., Nylund, J., & Stjernstrøm, E. (2015). On the practice architectures of instructional leadership. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 43(4), 490–506.

- Schatzki, T. (2002). The site of the social: A philosophical account of the constitution of social life and change. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Standal, O. F., & Hemmestad, L. B. (2011). Becoming a good coach: Coaching and phronesis. In I. A. Hardman & C. Jones (Red.), The ethics of sports coaching (pp. 45–55). London: Routledge.

- Trudel, P., & Gilbert, W. (2006). Coaching and coach education. In D. Kirk, D. Macdonald, & M. O’Sullivan (Eds.), The handbook of physical education (pp. 516–539). London: Sage.

- Vetenskapsrådet. (2017). God forskningssed. Stockholm: Author.

- Walker, L. F., Thomas, R., & Driska, A. P. (2018). Informal and nonformal learning for sport coaches: A systematic review. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 13(1), 694–707.

- Wallace, M. (1987). A historical review of action research: Some implications for the education of teachers in their managerial role. Journal of Education for Teaching, 13(2), 97–115.

- Werthner, P., & Trudel, P. (2006). A new theoretical perspective for understanding how coaches learn to coach. Sport Psychologist, 20(2), 198–212.

- Wilkinson, J., & Kemmis, S. (2015). Practice theory: Viewing leadership as leading. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 47(4), 342–358.