ABSTRACT

Although many studies have investigated teaching in one-to-one computing classrooms, not many have considered the material dimension as equally important to the human dimension. Thus, by using a sociomaterial perspective, we aim to broaden the discussion about emergent teaching practices in Nordic classrooms where students use tablets as personal devices. We therefore provide three vignettes from ethnographic classroom studies in Sweden, Finland and Denmark. These illustrate how tablets were used in specific classrooms. In our qualitative analysis of the vignettes, we draw on the concept of patterns of relations to describe the dynamic entanglements of the emergent teaching and learning practices. These are patterns of 1) interrogation, 2) spacemaking and 3) materialisation. Our findings show that tablets do not enter empty learning spaces but are woven into and participate in forming ways of teaching in one-to-one classrooms. Teachers must therefore learn to engage with and manage complex relationships rather than learn how to use an iPad.

1. Introduction

A significant trend in the digitalisation of elementary schooling is the massive investment in mobile devices such as tablets. For instance, the implementation of one-to-one computing, when a tablet is given to each student (Burden, Hopkins, Male, Martin, & Trala, Citation2012), is common both globally and in the Nordic countries (Blikstadt-Balas & Klette, Citation2020; Islam & Andersson, Citation2016; Islam & Grönlund, Citation2016; Jahnke, Bergström, Mårell-Olsson, Häll, & Kumar, Citation2017). This has become a pervasive strategy for developing schools and innovating teaching (Bocconi, Kampylis, & Punie, Citation2013; Harper & Milman, Citation2016; Meyer, Citation2020; Pegrum, Oakley, & Faulkner, Citation2013). Tablets and one-to-one computing are assumed to increase personalised and student-centred learning (Zheng, Warschauer, Lin and Chang, Citation2016) and to contribute to a reorganisation of educational spaces, as old schools are often not designed to support this kind of change (Tondeuer et al ., Citation2015; Burden et al., Citation2012; Holm Sørensen, Levinsen, & Holm, Citation2017). Changing forms of materiality therefore contribute to a shift in agency for both teachers and students (Mifsud, Citation2014; Thumlert, De Castell, & Jenson, Citation2015). Consequently, teachers need to rethink their planning and adapt their teaching to new kinds of emergent and dynamic classroom practices (Falloon, Citation2013; Kongsgården & Krumsvik, Citation2016; Merchant, Citation2017).

Our aim with this article is to contribute to a deeper understanding of teaching in one-to-one computing classrooms. We do this by exploring teaching practices through the concept of patterns of relations. The sociomaterial perspective is our theoretical lens to explore how teaching practices are formed, and possibly changed, as new conditions and possibilities merge within historically well-established classroom practices.

This article is organised as follows. In the literature section, we describe prior studies on one-to-one computing classrooms, with a focus on the Nordic countries, and present sociomaterial theory as a framework for this study. We then describe the process of revisiting data from our prior field studies and how we use three vignettes from these studies for further explorative analysis. In the results section, the explorative analysis of the vignettes is presented through three analytical concepts (i.e. patterns of interrogation, spacemaking and materialisation). Finally, we discuss these results and draw conclusions regarding how the findings contribute to the discussion on teaching in one-to-one computing classrooms.

2. Prior studies on one-to-one computing classrooms

The digitalisation of K-12 education has grown rapidly worldwide through one-to-one computing initiatives based on the principle of one laptop or tablet for each student (Islam & Grönlund, Citation2016). In the Nordic countries, studies on teachers’ practice in one-to-one computing classrooms have been reported in Sweden (Fleischer, Citation2013; Håkansson Lindqvist, Citation2015; Tallvid, Citation2015), in Norway (Blikstad-Balas, Citation2012; Blikstadt-Balas & Klette, Citation2020), in Denmark (Jahnke, Norqvist, & Olsson, Citation2014; Meyer, Citation2015) and in Finland (Bergström, Citation2019). Although one-to-one computing has become widespread in schooling, research is still needed to understand the complexities of significant and specific changes in teachers’ practices and how they affect learning (Burnett, Merchant, Simpson, & Walsch, Citation2017). Research, for instance, suggests that the digitalisation of schooling through one-to-one computing is not generally followed by continuous competence development for teachers (Beauchamp & Hillier, Citation2014; Ifenthaler & Schweinbenz, Citation2013; Spires, Oliver, & Corn, Citation20114). Teachers therefore seem to engage and cope with new technologies in different ways (Saudelli & Ciampa, Citation2014); some are, for instance, seen as early adopters and innovators (Jahnke & Kumar, Citation2014; Rogers, Citation2003) and others as sceptics or as taking an instrumental approach to technology (Holm Sørensen, Audon, & Levinsen, Citation2010; Montrieux, Vanderlinde, Courtois, Schellens, & De Marez, Citation2013).

Empirical studies have contributed to understanding teachers’ practices with one-to-one computing, based on either classroom observations, interviews or both (Beauchamp, Burden, & Abbinett, Citation2015; Bergström, Citation2019; Bergström et al., Citation2019; Blikstadt-Balas & Davies, Citation2017; Blikstadt-Balas & Klette, Citation2020; Ceratto Pargman, Citation2019; Håkansson Lindqvist, Citation2015; Jahnke et al., Citation2017; Kjällander, Citation2011; Meyer, Citation2015; Tallvid, Citation2015). These studies comprise issues of one-to-one computing use (e.g. Blikstadt-Balas & Davies, Citation2017; Håkansson Lindqvist, Citation2015), students’ meaningful learning (Jahnke et al., Citation2017), varying teaching and learning practices (Bergström, Citation2019; Bergström et al., Citation2019), unpredictability issues in teachers’ practice (Kjällander, Citation2011; Tallvid, Citation2015) and pedagogical development based on increased teacher–student collaboration (Beauchamp et al., Citation2015). Other studies that range from small-scale studies (Ceratto Pargman, Citation2019; Hershkovitz & Karni, Citation2018) to extensive classroom observations (Blikstadt-Balas & Klette, Citation2020) and literature reviews (Haßler, Major, & Hennessy, Citation2016) have found no significant changes in teachers’ practices with one-to-one computing. Although empirical studies are increasingly contributing to perspectives on teachers’ practices in one-to-one computing classrooms, they are also methodologically diverse and to some extent inconclusive. However, several recent studies have pointed to the methodological issues involved in studying one-to-one computing through relationships such as those between students and devices and students, teachers and devices (Burnett & Merchant, Citation2017; Ceratto Pargman & Jahnke, Citation2019; Hembre & Warth, Citation2019; Toohey, Citation2019). Burnett and Merchant (Citation2017), for instance, suggest that studies on tablet usage have moved in closed circles in the sense that defining research through specific relationships, outcomes and intentions has excluded other kinds of significant relationships in learning. This indicates that research could move forward by exploring multiple relationships in one-to-one computing classrooms.

3. Theoretical framework: a sociomaterial perspective

In this article, we aim to provide a comprehensive understanding of one-to-one computing in Nordic classrooms by exploring the multiple relationships that emerge from integrating tablets one-to-one in teaching. This is done by using a sociomaterial perspective that has contributed significantly to studies on technology in education in the past decade (Carvalho & Yeoman, Citation2018; Fenwick, Citation2015; Fenwick, Edwards, & Sawchuk, Citation2011; Johri, Citation2011; Sørensen, Citation2009; Toohey, Citation2019). These studies simultaneously underline the significance of materiality for learning and its constitutive entanglement with humans, thereby reconceptualising the role of technology in education as participatory and partial rather than central to learning (Meyer, Citation2020; Selwyn, Citation2011). Specifically, we use Sørensen’s (Citation2009) analytical concept of patterns of relations to unpack and explore these relationships and to show how practices are both recurrent and unpredictable.

Patterns of relations is a concept Sørensen (Citation2009) used in her seminal study of technology and knowledge in educational practice, where she drew on research in, for example, actor–network theory to understand how educational research can benefit from what she calls a post-humanist stance. Patterns of relations as a concept thus builds on a principle of symmetry (Latour, Citation2005) that places humans not above materials, but among them, thereby enabling explorations of specific sociomaterial relationships that make up practices. Sociomateriality refers to this levelling of humans and materials to the same ontological stance, and to the specificities of their connections and entanglements, which can be studied through research. Thus, humans, such as teachers and students, may use materials for learning. However, humans are also used and (trans)formed by ways in which materials, such as technologies, participate in and contribute to education. Understanding teaching and learning through patterns of relations, therefore, underlines that ontological primacy is not given to humans, but to connections and dynamics of practices, which are emergent rather than stable.

In focusing on patterns of relations, Sørensen underlines that relations do not signify interactions between well-delimited parts, but rather refer to webs of interactions that can be understood as spatial formations. Patterns of relations, therefore, form spaces that are specific and situated sociomaterial arrangements, called assemblages. One example of this is the understanding of students’ presence in the classroom, which in Sørensen’s perspective emerges as a regional pattern of relations performed by heterogeneous connections between the blackboard, the students’ gazes, the distance between teachers and students, etc. As classrooms are highly habituated spaces, and routines and order pervade the practices of teaching and learning (Friesen, Citation2011; Lawn & Grosvenor, Citation2005; McGregor, Citation2004; Nespor, Citation1997), we use the concept of rhythms to illustrate specific space–time formations (Leander & Lovvorn, Citation2006) in the classroom.

Understanding technologies in terms of sociomateriality will therefore enable us to transcend both techno- and human-centred understandings of classroom practices and explore significant connections and patterns in our data. A central aspect of this perspective is to identify ways in which patterns of relations are infused with power and affect; that is, patterns of relations underscore both the durability of relationships in practice and how they are formed through struggles and negotiations (Fenwick, Citation2015).

In our analysis, we explore three patterns of relations that emerged as significant from our data: patterns of interrogation, patterns of spacemaking and patterns of materialisation. These are patterns that are associated with habituated ways of organising teaching, as described in the literature. However, we argue that how practices endure is an empirical question that can be unpacked through explorations of sociomaterial relationships. Our analysis of the three patterns will, therefore, contribute new perspectives on how one-to-one computing creates predictability and change and how this affects teaching.

4. Methodology: revisiting ethnographic data from three prior studies

Our analysis is achieved by revisiting data from three Nordic studies on one-to-one computing classrooms. The studies from which we derive data represent Denmark (Meyer, Citation2020), Finland (Bergström, Citation2019) and Sweden (Bergström & Mårell-Olsson, Citation2018; Bergström et al., Citation2019). These include 67 classroom observations in total and explore teaching practices in which all teachers and students had a personal tablet (Burden et al., Citation2012). Municipalities that had implemented one-to-one computing in schools were specifically selected for these investigations. Multiple methods of data collection were used to capture a holistic view of what occurs in the dynamic and often messy context of a classroom (Fox & Alldred, Citation2015). This multimethod approach targeting 67 incidences of data collection is framed as multi-sited ethnographic classroom research (Hammersley Citation2018; Marcus, Citation1995). The methods used were observations (including field notes), detailed situational photos, panorama photos and video recordings of specific learning scenarios to understand processes and relationships (Pink, Citation2013). We are aware that bringing data together from different research projects poses methodological problems. As we are not conducting a comparative study, differences between the individual studies have been taken into account through our collaboration on analysis and by using vignettes as a narrative approach (Kucirkova & Sakr, Citation2017). Thus, vignettes as narrative accounts of situated activities aim to illustrate the specificities of both schools and teaching. The Danish study targeted students’ activities, whereas the Finnish and Swedish studies targeted teachers. In the latter, classroom interactions were audio recorded and later transcribed verbatim with regard to the teachers’ communication. Post interviews with the teachers targeted their teaching practice and beliefs about teaching and learning in a one-to-one classroom. All types of data were finally compiled into detailed narratives to frame the actions and the discourses for further analysis.

For this analysis, we therefore returned to the narratives to consider them in light of recent initiatives to introduce digital competence in curricula for compulsory education in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. One case from each country was selected for the present qualitative and explorative analysis. However, the present analysis is not a comparison of tablet use. Rather, the objective is to use the three cases, presented as vignettes of each classroom practice, as sources for an explorative discussion. The three authors have met 15 times (approx. 18 hours in total), during which we have delved deep into our own understanding of what we see is taking place in the three selected classrooms.

We started from differing theoretical backgrounds. However, we wanted to approach the analysis of the three teaching practices as openly as possible. Therefore, a sociomaterial perspective was chosen because of its view on the social and the material as equal factors impacting the situation (Sørensen, Citation2009). Rather than being focused on digital competence, both our discussions and the analysis were driven by our curiosity to explore teaching practices in a less restricted manner, as well as broadening the view to include a relational perspective (cf. Wiklund-Engblom, Citation2018). The analysis starts from the patterns of relations described by Sørensen (Citation2009) and expands on these based on significant patterns found in the three selected cases.

4.1. Using structured vignettes

The three vignettes presented in the following illustrate uses of tablets and other material resources as part of the dynamic classroom practice. The vignettes are structured to describe both the context of practice and the process of emergent activity. The classes were of standard size, about 25 students, and taught by one teacher, in the Danish case by two collaborating teachers in two different school localities. The observed lessons lasted 45–90 minutes.

4.1.1. Vignette 1: learning Swedish as a native language using iMovie in Sweden

4.1.1.1. Context

In the first vignette, we meet the teacher Mary, who invited us to observe a thematic lesson about parts of speech in a Swedish native language class for 8th graders. The students are in their second week of study, working in groups of four to produce videos on their tablets using the iMovie app. Mary starts the lesson with the whole class and introduces today’s lesson with two headings on the whiteboard: 1) Film about parts of speech (deadline Tuesday) and 2) Spelling (spelling duel). Briefly, Mary starts by probing how far the students have progressed in their movie making. Thereafter, she organises which rooms the students can use. At this point, most groups leave the classroom. Mary visits each group for 5–10 minutes in the locations illustrated in .

4.1.1.2. Process: emerging learning activity

Mary believes that the use of tablets and the iMovie app for producing videos enabled the students to achieve the learning goals of the curriculum, but she also emphasises that with such an approach, students “communicate better with each other. They actually listen more to each other.”

Mary first approaches a group of two boys and two girls working at the library (). The group works with nouns, verbs and adverbs. Mary asks them gently if they need to change something and if they need to make a summary at the end of the film. The students inform Mary that that is already done. Mary continues to probe the content of the students’ film with implicit how and what questions. One girl answers tentatively, and Mary suggests the girl could wear a costume representing an adverb saying, “You could dress as an adverb.” The pupils look confused and ask Mary what she means. Apparently, something is missing in the students’ text, and Mary switches to an explicit mode: “Have you included the three interrogative words?” The students look puzzled, and Mary realises that the students have not received these words and says, “Then you have some work”. Mary continues and says, “What are the questions, you have to include.” The discussion moves in the direction of tense and other grammar. Before leaving the group, Mary again says, “You have to get it into the film. You have to make a plan to bring this in; it is important that it is included”. Mary organises the group’s work for this lesson and says, “You can plan today”. Mary continues to probe the other groups in a similar way. Mary argues that the most important aspect is to be able to have a dialogue where the students dare to ask questions and reason about things in the classroom. Furthermore, she emphasises the respect for each other in the teacher–student relationship. She says, “This mutual respect is actually the basis for us liking each other. As a consequence, they care more about what I say, and I care more about what they say. This makes learning more fun.”

4.1.2. Vignette 2: learning geography using iMessage, camera, iMovie and Evernote in Finland

4.1.2.1. Context

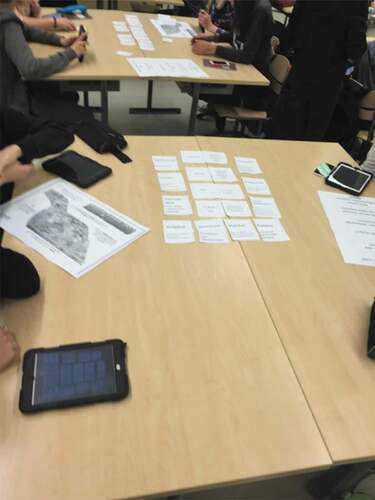

In the second vignette, we meet the teacher Susanne who invited us to observe a lesson in geography on the topic of rivers in an 8th-grade class. As illustrated in , this lesson involves a rich amount of different materials such as the textbook, students’ tablets with different apps, and paper cut-outs used for a game. Susanne starts the lesson by instructing students to work in groups, followed by guidance on the lesson’s different sequences. Susanne highlights that with the iMessage app, students will send in assignments for assessment, which could be texts, photographs or recorded videos.

4.1.2.2. Process: emerging learning activity

Susanne starts by briefly reminding the students of what they studied in the previous lesson and what facts were studied. She says, “Today, we have a new chapter about rivers in the textbook [e-book], but then we only had the Rhine in Germany and the Donau, and I don’t care much about the details. I want you to know about the significance of rivers”. The observed learning activities were divided into 5 working sequences. In the first slot of 40 minutes, the students 1) read a text in an email from the teacher and 2) engage in group work based on three subtasks, where they (a) practice a memory game-like task with paper cut-outs (students group river names with river characteristics) and (b) practice another game-like task with paper cut-outs (where river concepts on paper are paired with explanations or meanings) (). During the first two tasks, the teacher calls for students to use the tablet by saying, “You are allowed to Google, search for answers” or “basically, you start first by checking if you can Google on [the geography concept] meandering. Do you find something? Odd words can be placed on one page and explanations can be found further down the page”. In the students’ work, they switch between searching for answers and pairing concepts and meanings. Answers from (a) and (b) are photographed by the students and sent to the teacher via iMessage, and the teacher frequently says, “Did you remember to send it to me? Take a picture”.

After the break, in the next 45 minutes, the students 3) conduct an experiment with sand and water and 5) watch a YouTube film about rivers. The teacher starts by saying, “The intention is that you produce a presentation about meandering in rivers. In this box, we take sand from the bucket and cover the bottom of the box. Aim for creating a river-like landscape […]. Then you use your finger and drag a meandering river, like a trench; then you take some water […] When you pour the water, your peers make a film of how the river meanders and how it happens. In iMovie, you can use arrows and add text about what was taking place in the river”. After about 15 minutes of conducting the experiment, the teacher–student communication turns to the YouTube video: “Did you check the video – Why do rivers curve?” The teacher guides students to the content, where they can search for geography-specific concepts related to meandering of rivers. Throughout this lesson, the teacher asks students frequently to submit their accomplished tasks for assessment. Susanne says, “Feedback motivates them, and they were really competitive, like they wanted to compete themselves and maybe with a friend […] but because the feedback for me was so positive I thought that this is the right way, better than I’m just, you know, talking, talking, talking, and then one exam and that’s it. And that’s why I put this year’s exam as optional because we have done every week a homework exercise, so they got the points. It’s more than … exam, if I put those together. Of course, if you make a video as homework, it’s quite a lot, that’s why”.

4.1.3. Vignette 3: learning German vocabulary through FaceTime in Denmark

4.1.3.1. Context

In the Danish vignette, we meet the teacher Birgit, who invited me to observe two lessons about working with vocabulary in German as a foreign language for 7th graders. The students are in their first year and third month of studying German. The purpose of the lesson is for the students to work with German vocabulary by communicating through the software application FaceTime on their tablets with peers in another part of the municipality. Birgit has therefore planned the lesson together with the German teacher Eva from the collaborating school. I talk to both teachers before and after the lesson. Both teachers have had to reorganise lessons to make this event possible, as German is not taught at the same time in the schools.

4.1.3.2. Process: emerging learning activity

I observe two 45-minute lessons. One is focused on the FaceTime activity, and in the second, students work with peers in the individual schools to make a video on the overall theme of the lessons, which is “My family” (see ). The videos made by the students are to be shared later in the school year with students from the collaborating school through a video conference session.

Birgit introduces the FaceTime activity, which she tells me has been prepared by students in prior lessons in the individual schools. She and the other teacher also tell me that it is specifically relevant for this age group to practice their spoken language, as teenagers are often shy and self-conscious about using a foreign language. One of the principles underlying the use of interaction through the tablet is therefore to create a feeling of equity and proximity between the students.

Birgit tells the students to take turns presenting themselves in German to the students in the collaborating school. She says that they have to do this with the support of a piece of paper with notes that they have prepared as homework and worked with in prior lessons. The notes are based on a number of questions (in German) that serve to frame the interaction with the other students, such as Where do you live? How many members are there in your family? What are the names of your brothers and sisters? In Birgit’s class, students are placed in groups of two and given the necessary contact information to call the students at Eva’s school. Eva has asked her students to work individually on the task to avoid distractions; this has been discussed by the two teachers but also means that students’ interaction at the outset is a situation organised differently by the two teachers. Birgit circulates in and outside the classroom, where students have placed themselves in pairs, often using a table where the tablet is placed in a central position and the students face the screen in a kind of mediated face-to-face set-up (). The paper with questions and notes is placed strategically close to students’ hands and eyes, so they can use the paper as a support in the interaction. Most students succeed in disseminating their answers to the other students in German and listen to what the other students tell them; however, some of the students are confused, as they try to contact students in the other school who do not answer. Birgit therefore engages herself in helping the students in distress and calling up Eva to understand what is happening. Afterwards, both teachers tell me that the FaceTime interaction between the students was not entirely successful, as the students did not know each other beforehand, and some of them acted in disruptive ways and lacked netiquette in their ways of addressing other students. Additionally, practical problems with students who were ill or did not remember their passwords affected the lesson.

5. Results

In the following section, we unpack the vignettes and provide an analysis of three patterns of relations (patterns of interaction, patterns of spacemaking, patterns of materialisation). Each pattern attempts to capture the participatory and partial role humans and resources have in one-to-one computing. The patterns point to the complexity of the entanglement of social and material resources illustrated through different rhythms and assemblages in teaching.

5.1. Patterns of interrogation

In the vignettes, language can be seen as a pervasive phenomenon that is involved in creating conceptual knowledge (grammar and names of rivers), producing interaction and dialogue (FaceTiming with others), and engaging with materials (Google, iMovie, paper cut-outs). In addition to engaging with language as a concept or as a materiality (a multimodal “doing”) through, for example, in the Finnish and Swedish vignettes with iMovie, language is embodied, as it is associated with the teacher’s voice and with students’ answers to the teacher’s questions and comments. Voice therefore becomes an aspect of embodied language in the lessons, as the teacher’s intervention, position and pedagogy is emphasised and amplified through her voice (i.e. the specific embodiment of her teacher voice). Teachers’ and students’ voices thus interact as embodied phenomena in the lessons and are orchestrated in different ways that create (power) relationships, dialogue and structure in practice.

A significant pattern of interaction observable in the examples is therefore the pattern of interrogation, where teachers question students and students answer. Patterns of interrogation are established rhythms of teaching that serve to involve students and structure their learning in specific ways – with the participation of materials (Kalthoff & Roehl, Citation2011). In the Swedish vignette, for instance, this is seen when the teacher asks students about the making of their film and a student answers tentatively, as well as when she interrogates them about whether they have included the relevant words in the movie-making activity. For this teacher, the relationship with her students is defined by communication and dialogue, and the rhythm of interrogation is therefore a significant enactment of her teacher agency and competence. In the Finnish vignette, the teacher is also involved in patterns of interrogation, for instance when she uses her questioning voice to structure the students’ video-making activity. Question-and-answer rhythms in this case not only involve the teacher’s voice, but also searching in Google, as the teacher says that students are allowed to Google, search for answers. Google in this context becomes part of the question-and-answer pattern, and the sociomaterial assemblage can therefore be seen as adding to the students’ resources and to some extent replacing the teacher in the pattern, as Google seems to both structure the questioning and provide the answers. For the Finnish teacher, dialogue is also part of her pedagogical approach (… because the feedback for me was so positive I thought that this is the right way, better than I’m just you know talking, talking, talking), and dialogic teaching is, therefore, in the teacher’s understanding, produced by the student-centred activity of making a video. Involving students in dialogue and in the rhythm of interrogation is also seen in the Danish vignette, where the rhythm of interrogation has been moved into the students’ interaction, as questions and answers are involved in the FaceTime interaction between near and far students. Patterns of interrogation are, therefore, with the use of technologies, involved in orchestrating the relationship both between teachers and learners and between learners in different localities.

In addition to orchestrating students’ learning, using voice as an embodied instrument of language is, as mentioned above, entangled with practices and ideologies of teaching. This is expressed, for instance, when the Swedish teacher addresses the dialogue, asking and reasoning with her students. Here, the “dialogic” way of teaching is thus entangled with affective aspects of teaching such as respect, positive relationships and caring. For the Finnish teacher, dialogic teaching is also explicitly stated as an ideological concept of teaching, as making the video about rivers is an alternative to her talking, talking, talking. Voicing as an embodied language therefore seems to be less neutral than the conceptual language of, for example, meandering rivers that is the focus of the Finnish lesson. Materialising and embodying language thus seems to increase the affective and ideological aspects of teaching, and embodied language has a specific role in the classroom as it is connected to the teacher’s “I”; that is, the position, role and (professional) identity of the teacher.

5.2. Patterns of spacemaking

In the Danish vignette, spatial formations can be seen, for instance, in the pattern of relations constituted between near and far students involved in the German vocabulary activity, and the way in which FaceTime contributes to producing this as a students’ region. FaceTime thus participates in producing a peer-to-peer pattern of relations that define and consolidate the students’ region(s) in the classroom(s). As a pattern of relations, the regional space is produced by the personal desks and learning material, the video and eye contact between the students across spaces, and their speech and proximity in the room(s). Thus, the sociomaterial assemblage produces specific enactments of both student learning and peer learning environments and establishes rhythms of student agency in the classroom in specific ways. As the Danish teacher underlines, the distance between the near and far students interferes with their ability to perform the activity with confidence, and the FaceTime conversation therefore to some extent hinders the flow of interaction that might have been created in a face-to-face activity between students who were familiar with each other. Thus, either the activity needs to be reassembled or the assemblage needs to be established as part of the practice of German vocabulary.

In the Swedish and Finnish examples, patterns of spacemaking emerge around several activities, but specifically the making of videos, where tablet ownership in combination with visual (trans)formations of curriculum material establish students’ regions in the classroom. Spacemaking therefore involves both patterns of student-to-student interaction, where students through moviemaking communicate better with each other (Swedish vignette), and patterns of materialisation that allow students to produce rather than just interact with material (the intention is that you shall produce a presentation about meandering in rivers, Finnish vignette). Spacemaking is therefore significantly shaped by personal devices that students have at hand.

5.3. Patterns of materialisation

Making grammar visual through iMovie, for instance, enables students’ engagement in grammar in specific ways, where adverbs become everyday occurrences, as when the teacher says that you can dress as an adverb (Swedish vignette). Chains of translation of knowledge from one materialisation to another are consequently a rhythm that can also be observed in the vignettes, where, for instance, working with rivers (in the Finnish example) is implicated in multiple patterns of materialisation through which knowledge is circulated and transformed. Transformations in the vignettes thus include relationships both between students’ materialisations (e.g. when working with German vocabulary is constituted through interrelated patterns of using vocabulary through FaceTime and making a filmed presentation) and between authoritative (teachers’) sources (the whiteboard in the Swedish example) and the students’ work (making a video in the Swedish example). Tablets are significant participants in these patterns of materialisation, as are the spacemaking patterns of creating students’ regions through the involvement of personal desks, notes and different arrangements of digital and face-to-face interactions.

In the Finnish vignette, working with meandering rivers is, as mentioned above, performed through multiple chains of interrelated activities, where patterns of materialisation include relationships between both analogue and digital materials. Thus, patterns of materialisation in the Finnish example involve memory games using paper cut-outs, Googling to search for answers, reading the e-book, watching a YouTube video, sending photos through iMessage and filming a sand and water experiment. As ways of “learning about rivers”, these materialisations are assemblages that contribute to forming the knowledge involved in the lesson and to creating a structure in which knowledge can be mobilised through heterogeneous uses and chains of materials. Patterns of materialisation thus seem to create rhythms of repetition, in which names and concepts can be presented and pedagogically framed for students. However, patterns of materialisation serve not only to present and frame, but also to translate and differentiate the knowledge through students’ activities, as students’ engagements with names and concepts are formed by both, for example, the playful approach of the memory game and the experimental approach of forming and filming meandering rivers. Patterns of materialisation can therefore be associated with specific rhythms of teaching and learning, where materialisations serve to make knowledge playful and experimental.

In the Finnish example, patterns of materialisation often establish concretisations of the abstract; for example, abstract knowledge such as names and concepts of rivers are translated into activities that students are familiar with from schooling or leisure time. Gaming may, for instance, be an activity that many students are engaged in during their everyday activities, and translating concepts into a game can therefore connect abstract concepts and everyday understanding. In this formation of knowledge, both analogue and digital resources participate – paper cut-outs, for instance, contribute to making concepts playful, and sand and water contribute to making meandering tactile and mouldable. Filming through the tablet can translate experimentation with natural materials into a structured documentation of meandering as a process and thus build a bridge between forming a meandering river and observing it. Patterns of materialisation are thus significant pedagogical practices that provide students with agency in specific ways by, for example, allowing them to form and interact with knowledge by materialising it. This is also observable in the Swedish example, where abstract forms of language such as grammar, spelling and parts of speech become intelligible and mouldable for students through a spelling duel and making a film. Patterns of materialisation in all three vignettes thus tend to include video production as a student-centred activity, where the arrangement and formation of knowledge is situated within the students’ region (i.e. personalised space) in the classroom. Our analysis of patterns of relations in teaching with tablets therefore allows us to understand and discuss how specific agencies emerge from these relationships in practice.

6. Discussion

This study aimed to contribute to a deeper understanding of teaching practices in classrooms where tablets are used as part of one-to-one computing. The article used the concept of patterns of relations (Sørensen, Citation2009) and a sociomaterial perspective to explore these complexities and to show how teaching is involved in practices constituted by patterns of interrogation, materialisation and spacemaking.

As shown by our analysis, patterns are multiple and changing relationships that form teaching in specific ways, implicating that teachers are not central to but part of changing sociomaterial relationships. Similarly, the concept of materialisation underlines that technologies are not exclusive to initiating change and cannot be separated from extensive material classroom cultures that are not solely digital (Mulcahy & Morrison, Citation2017). Tablets, therefore, do not enter empty learning spaces but are woven into and participate in forming ways of doing teaching in one-to-one classrooms in schools that originally were not designed for one-to-one computing (Tondeur et al., Citation2015). An example of this from our findings is when tablets are enrolled in extensive chains of materials and interrelated activities to teach the meandering of rivers (Finnish vignette). Another example is ways in which Googling influences patterns of interrogation in the classroom and, therefore, the teacher’s role in this practice (Swedish vignette). These are examples that have implications for teacher education, as teachers must learn to engage with and manage these complex relationships and transformations rather than learn how to use tablets (e.g. iPads). They are also examples that contribute to existing research, as they extend our insights into teaching in one-to-one computing classrooms beyond the closed circles of focusing on teacher–learner relationships and affordances of the technology (Burnett et al., Citation2017).

Following our focus on patterns of relations, we can identify teaching practices in one-to-one classrooms as implicated in both hegemonic and emergent ways of doing teaching. This is in line with research that understands classrooms as highly habituated spaces and tablet use as functional and convenience driven (Blikstadt-Balas & Davies, Citation2017; Friesen, Citation2011) but also challenges these assumptions. A convincing number of studies (Blikstadt-Balas & Davies, Citation2017; Blikstadt-Balas & Klette, Citation2020; Ceratto Pargman, Citation2019; Haßler et al., Citation2016; Hershkovitz & Karni, Citation2018) have shown that tablets, although useful and convenient to teachers, have not significantly transformed educational practices or enabled innovative approaches to teaching and learning. The three patterns of interrogation, spacemaking and materialisation may therefore indicate that teachers are central in performing and upholding existing discourses, organisations and uses of learning materials in teaching and that tablets are enrolled in these practices. Our findings challenge these conclusions, as they show that although classroom practices can seem conservative and repetitive, they are also deeply affected by negotiations and change formed by intertwined sociomaterial relationships. Transformation and change can therefore be identified in specific sociomaterial patterns of relations where tablets are involved in teaching.

One example of this from our findings is the way in which patterns of relations form teacher and learner interactions through complex sociomaterial relationships involving video-making and uses of language in the classroom. Emerging across all three classroom vignettes is thus the observation that video-making is a significant transformative activity that contributes to forming and delineating students’ regions, as well as teachers’ agency in the classroom. Video-making is, for instance, an activity that defines peer-to-peer interaction in the Danish vignette, and in the Swedish and Finnish examples, videos become part of the patterns of materialisation associated with students’ self-organised work. Video-making thus appears to be the most student-centred of the identified patterns of materialisations, as video production allows students to learn by selecting, editing and structuring knowledge through their personal devices. However, as a student-centred activity, video-making also becomes a site of negotiation, where power relations are played out as part of the activity. For instance, as mentioned in the analysis, the teacher’s voice accompanies both the filming of the river experiment in the Finnish example and the making of the iMovie in the Swedish example, and therefore, the teacher’s engagement and agency interact with those of the students in the activities. Video-making is thus co-constructed through patterns of interrogation, materialisation and spacemaking, where it is simultaneously constituted as a student-centred and a teacher-orchestrated activity.

7. Conclusions

This article has explored the dynamic relations and complex transformations taking place in uses of one-to-one computing in three specific situations in Nordic classrooms. Based on our analysis, we argue that the identification of complex patterns of relations between materials and activities in one-to-one computing has implications for teacher education, as teachers need competences to act in these changing practices. It may be that the identified complexities are not specific to one-to-one computing; however, we see the integration of personal technologies such as tablets as examples of emergent ways of using technologies in schooling. With regard to teachers’ competences, we understand these as situated and co-constructed, as teachers’ agency is contingent on multiple relationships in practice that are sociomaterial. From our examples in the vignettes, we observe, for instance, that students become innovative and interactive participants in entangled practices and that materiality is significant in forming knowledge in several school subjects. We therefore argue that we need a more holistic view on what teachers’ digital competence can be, and how it emerges from specific classroom practices. Although our study is limited in scope, we believe that our analysis contributes to an understanding of how patterns of relations both hold practices together in hegemonic ways and constitute change. We believe that the exploration of these specific relationships and tensions is at the core of understanding teaching in one-to-one computing classrooms.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Bente Meyer

Bente Meyer is associate professor at the Department of Culture and Learning, Aalborg University in Copenhagen, Denmark. Her field of research is ICT and learning, digitalization of schooling and mobile learning.

Peter Bergström

Peter Bergström is associate professor at the Department of Education at Umeå University, Sweden. His field of research is ICT and learning, transformation processes and school development.

Annika Wiklund-Engblom

Annika Wiklund-Engblom is independent researcher and consultant, project manager in designing for wellbeing and resilience at Folkhälsans Förbund, and prior post-doctoral fellow at Umeå University (2017-2019).

References

- Beauchamp, G., Burden, K., & Abbinett, E. (2015). Teachers learning to use the iPad in Scotland and Wales: A new model of professional development. Journal of Education for Teaching, 41(2), 161–179.

- Beauchamp, G., & Hillier, E. (2014). An evaluation of iPad implementation across a network of primary schools in Cardiff. Cardiff: Cardiff Metropolitan University.

- Bergström, P. (2019). Illustrating an analysing power and control relations in Finnish one-to-one computing clasrooms: Teacher practices in grade 7–9. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 14(3–4), 117–133.

- Bergström, P., & Mårell-Olsson, E. (2018). Power and control in the one-to-one computing classroom: Students’ perspectives on teachers’ didactical design. Seminar.net - International Journal of Media, Technology and Lifelong Learning, 14(2), 160–173.

- Bergström, P., Mårell-Olsson, E., & Jahnke, I. (2019). Variations of symbolic power and control in the one-to-one computing classroom: Swedish teachers’ enacted didactical design decisions. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 63(1), 38–52.

- Blikstad-Balas, M. (2012). Digital literacy in upper secondary school – What do students use their laptops for during teacher instruction. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 7(2), 81–96.

- Blikstadt-Balas, M., & Davies, C. (2017). Assessing the educational value of one-to-one devices: Have we been asking the right questions? Oxford Review of Education, 43(3), 311–331.

- Blikstadt-Balas, M., & Klette, K. (2020). Still a long way to go: Narrow and transmissive use of technology in the classroom. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 15(1), 55–68.

- Bocconi, S., Kampylis, P., & Punie, Y. (2013). Framing ICT-enabled innovation for learning: The case of one-to-one learning initiatives in Europe. European Journal of Education, 48(1), 90-119.

- Burden, K., Hopkins, P., Male, T., Martin, T., & Trala, C. (2012). iPad Scotland evaluation. Faculty of Education: University of Hull.

- Burnett, C., & Merchant, G. (2017). The case of the iPad. In C. Burnett, G. Merchant, A. Simpson, & M. Walsch (Eds.), The Case of the iPad (pp. 1-14). Singapore: Springer.

- Burnett, C., Merchant, G., Simpson, A., & Walsch, M. (eds.). (2017). The case of the iPad. Singapore: Springer.

- Carvalho, L., & Yeoman, P. (2018). Framing learning entanglement in innovative learning spaces: Connecting theory, design and practice. British Educational Research Journal, 44(6), 1120–1137.

- Ceratto Pargman, T., & Jahnke, I. (2019). Introduction to emergent practices and material conditions in learning and teaching with technologies. In T. Cerratto Pargman & I. Jahnke (Eds.), Emergent practices and material conditions in learning and teaching with technologies (pp. 3–20). Cham: Springer.

- Ceratto Pargman, T. (2019). Unpacking emergent teaching practices with digital technology. In T. Cerratto Pargman & I. Jahnke (Eds.), Emergent practices and material conditions in learning and teaching with technologies (pp. 3–20). Cham: Springer.

- Falloon, G. (2013). Young students using iPads: App design and content influences on their learning pathways. Computers & Education, 68(October), 505–521.

- Fenwick, T. (2015). Sociomateriality and learning: A critical approach. In D. Scott & E. Hargreaves (Eds.), The Sage handbook of learning(pp. 83-93) London: Sage.

- Fenwick, T., Edwards, R., & Sawchuk, P. (2011). Emerging approaches to educational research: Tracing the sociomaterial. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Fleischer, H. (2013). En elev-en dator: Kunskapsbildningens kvalitet och villkor i den datoriserade skolan (Doctoral Compilation). Jönköping University. Retrieved from http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:663330/FULLTEXT01.pdf(21)

- Fox, N.J., & Allred, P. (2015). New materialist social inquiry: designs, methods and the research-assemblage. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 18(4), 399–414. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2014.921458

- Friesen, N. (2011). The place of the classroom and the space of the screen – Relational pedagogy and internet technology. New York: Peter Lang.

- Håkansson Lindqvist, M. (2015). Exploring activities regarding technology-enhanced learning in a one-to-one initiative. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 10(4), 227245.

- Hammersley, M. (2018). What is ethnography? Can it survive? Should it?, Ethnography and Education, 13:1, 1–17, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17457823.2017.1298458

- Harper, B., & Milman, N. B. (2016). One-to-one technology in K-12 classrooms: A review of the literature from 2004 through 2014. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 48(2), 129–142.

- Haßler, B., Major, L., & Hennessy, S. (2016). Tablet use in schools: A critical review of the evidence for learning outcomes. Journal of Computer Assissted Learning, 32(2), 139–156.

- Hembre, O. J., & Warth, L. L. (2019). Assembling iPads and mobility in two classroom settings. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 25(2020), 197–211.

- Hershkovitz, A., & Karni, O. (2018). Boarders of change: A holistic exploration of teaching in one-to-one computing programs. Computers & Education, 125(2018), 429–443.

- Holm Sørensen, B., Audon, L., & Levinsen, K. T. (2010). Skole 2.0: Didaktiske bidrag. Aarhus: Klim.

- Holm Sørensen, B., Levinsen, K. T., & Holm, M. R. (2017). Udvikling af lærerens digitale kompetencer med iPad’en som læringsressource. Learning Tech – Tidsskrift for Læremidler, Didaktik Og Teknologi, 3, 32–55.

- Ifenthaler, D., & Schweinbenz, V. (2013). The acceptance of Tablet-PCs in classroom instruction: The teachers’ perspectives. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 525–534.

- Islam, S. M., & Andersson, A. (2016). Investing choices of appropriate devices for one-to-one computing initiatives in school worldwide. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 6(10), 817–825.

- Islam, S. M., & Grönlund, Å. (2016). An international literature review of 1:1 computing in schools. Journal of Educational Change, 17(2), 191–222.

- Jahnke, I., Norqvist, L., & Olsson, A. (2014). Digital didactical designs of learning expeditions. Lecture notes in Computer Science 8719. In Cristoph Rensing, Sara de Freitas, Tobias Ley, Pedro J. Muños-Merino (Ed.), Open learning and teaching in educational communities. Paper presented at the European Conference on Technology Enhanced Learning EC-TEL 2014. Graz, Austria.

- Jahnke, I., Bergström, P., Mårell-Olsson, E., Häll, L., & Kumar, S. (2017). Digital didactical designs as research framework: IPad integration in Nordic schools. Computers & Education, 113, 1–15.

- Jahnke, I., & Kumar, S. (2014). Digital didactical designs: Teachers’ integration of iPads for learning-centered processes. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 30(3), 81–88.

- Johri, A. (2011). The socio-materiality of learning practices and implications for the field of learning technology. Research in Learning Technology, 19(3), 207–217.

- Kalthoff, H., & Roehl, T. (2011). Intersubjectivity and Interactivity – Material Objects and Discourse in Class. Human Studies, 34(4), 451–469.

- Kjällander, S. (2011). Designs for learning in an extended digital environment (Doctoral compilation). Stockholm University, Stockholm.

- Kongsgården, P., & Krumsvik, R. (2016). Use of tablets in primary and secondary school – A case study. Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy, 11(4), 248–273.

- Kucirkova, N., & Sakr, M. (2017). Personalized Story-Making on the iPad: Opportunities for Developing the Self and Building Closeness with Others. In Burnett, C., Merchant, G., Simpson A., Walsh, M. (eds) The Case of the iPad. (pp. 179–193) Springer, Singapore. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4364-2_11

- Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social. An introduction to actor-network theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lawn, M., & Grosvenor, I., (Red.). (2005). Materialities of schooling. Design, technology, objects, routines. Comparative histories of education. Oxford: Symposium Books.

- Leander, K. M., & Lovvorn, J. F. (2006). Literacy networks: Following the circulation of texts, bodies and objects in the schooling and online gaming of one youth. Cognition and Instruction, 24(3), 291–340.

- Marcus, G. E. (1995). Ethnography in/of the world system – The emergence of multi-sited ethnography. Annual Review of Anthropology. 24(1) 95-117.

- McGregor, J. (2004). Spatiality and the place of the material in schools. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 12(3), 347–372.

- Merchant, G. (2017). Hands, fingers and iPads. In C. Burnett, G. Merchant, A. Simpson, & M. Walsch (Eds.), The case of the iPad (pp.245-256). Singapore: Springer.

- Meyer, B. (2015). Learning through telepresence with iPads: Placing schools in local/global communities. Interactive Technology and Smart Education, 12(4), 270–284.

- Meyer, B. (2020). Med teknologien ved hånden: Tablets og mobil læring i skolens praksis (Having technologies at hand: tablets and mobile learning in schooling). Copenhagen: Dafolo.

- Mifsud, L. (2014). Mobile learning and the socio-materiality of classroom practices. Learning, Media and Technology, 39(1), 142–149.

- Montrieux, R., Vanderlinde, R., Courtois, C., Schellens, T., & De Marez, L. (2013). A qualitative study about the implementation of tablet computers in secondary education: The teachers’ role in this process. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 112, 481–488.

- Mulcahy, D., & Morrison, C. (2017). Re/assembling ‘innovative’ learning environments: Affective practice and its politics. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 49(8), 749–758.

- Nespor, J. (1997). Tangled up in school. Politics, space bodies, and signs in the educational process. New York: Routledge.

- Pegrum, M., Oakley, G., & Faulkner, R. (2013). Schools going mobile: A study of the adoption of mobile handheld technologies in Western Australia independent schools. Australian Journal of Educational Technology, 29(1), 66–81.

- Pink. (2013). Doing visual ethnography. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Rogers, E. (2003). Diffusion of innovations. New York: Free Press.

- Saudelli, M. G., & Ciampa, K. (2014). Exploring the role of TPACK and teacher self-efficancy: An ethnographic case study of three iPad language arts classes. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2014.979865

- Selwyn, N. (2011). In praise of pessimism - the need for negativity in educational technology. Editorial. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42(5), 713–718.

- Sørensen, E. (2009). The materiality of learning: Technology and learning in educational practice. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Spires, H. A., Oliver, K., & Corn, J. (2011). The new learning ecology of one-to-one computing environments: Preparing teachers for shifting dynamics and relationships. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 28(2), 63–72.

- Tallvid, M. (2015). 1:1 i klassrummet - analyser av en pedagogisk praktik i förändring (Doctoral Compilation). University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg

- Thumlert, K., De Castell, S., & Jenson, J. (2015). Short cuts and extended techniques: Rethinking relations between technology and educational theory. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 47(8), 786–803.

- Tondeur, J., De Bruyne, M., Van Den Driessche, S., McKenny, S., & Zandvliet, D. (2015). The physical placement of classroom technology and its influences on educational practices. Cambridge Journal of Education, 45(4), 537–556.

- Toohey, K. (2019). The onto-epistemologies of new materialism: Implications for applied linguistics pedagogies and research. Applied Linguistics, 40(6), 937–956.

- Wiklund-Engblom, A. (2018). Digital relational competence: Sensitivity and responsivity to needs of distance and co-located students. Seminar.net - International Journal of Media, Technology and Lifelong Learning, 14(2), 188–200.

- Zheng, B., Warschauer, M., Lin, C-H., & Chang, C. (2016). Learning in One-to-One Laptop Environments: A Meta-Analysis and Research Synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 1052–1084, doi:https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654316628645.