ABSTRACT

In 2008, Iceland launched policy reform in upper secondary education. This paper elucidates how upper secondary school leaders acted when leading reform and confronting teacher responses. The study is based on interviews with 21 leaders from nine upper secondary schools. The data were analysed usingfive response categories to macro-level demands for change,institutional and organisational leadership, and theories on subject hierarchies. The findings show how the school leaders from the nine participating schools experienced differently the policy enactment in their schools. Seven of the nine schools matched three out of Coburn’s five response categories. Adding the category of pioneering would enable appropriate categorisation of new schools. Polarisation appeared in the data both between and within the evaluated schools. Within some of the schools, many self-contained subunits were seen to be operating. The school leaders usually responded either as institutional or organisational leaders or they gave examples of hybrid interactions between both types, particularly when polarisation was operating within the schools. The most explicit resistance to change was reported to arise from faculty members of traditional academic subjects. The apparent isomorphism among education systems worldwide suggests that lessons from Iceland may be valuable for the global education community.

1. Introduction

The focus of this paper is to study policy enactment in nine upper secondary schools in Iceland in the aftermath of an extensive reform introduced by the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture (hereafter MoESC) in 2008 and 2011. There is a growing body of research claiming macro-level actors to be the key actors in reforms within education. These actors include international, national, and local authorities (see Adolfsson & Alvunger, Citation2020). However, when it comes to reform within education these macro-level actors do not always succeed in their intentions to change schools (Ball, Maguire, & Braun, Citation2012; Ragnarsdóttir, Citation2018a, Citation2018b). As a result, other scholars have turned towards teachers and school leaders as the most important change agents (Barsh, Capozzi, & Davidson, Citation2008; Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012). These different viewpoints accentuate the need to carry out further research that focuses on the complex interplay between policy reforms stipulated by macro-level actors and how policy enactment is carried out by school leaders and teachers in schools (Ball et al., Citation2012; Coburn, Citation2004; Gunnulfsen & Møller, Citation2017; Liljenberg, Citation2015).

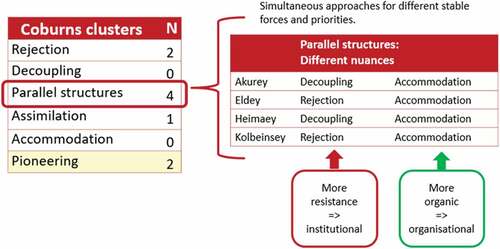

This study relies on interviews with 21 school leaders from the nine upper secondary schools, reviewing the complexity of policy enactment in their schools. To analyse and interpret the data various neo-institutional lenses were used to probe the complex interactions between school leaders and teachers when enacting the reform. This is partly done in line with Burch’s (Citation2007) call to researchers within education to better explore the interaction between institutional and organisational theories, but also to better understand the inertia. The main concepts of the paper come from Scott’s (Citation2014) ideas on institutions and organisations and Washington, Boal, and Davis’s (Citation2008) views on institutional and organisational leadership (see also Kraatz, Citation2009; Raffaelli & Glynn, Citation2015). Washington et al. (Citation2008) draw the attention to leaders’ roles in enabling or constraining change by focusing on their agency, power, and vision. These concepts are highly relevant when analysing the interviews with school leaders. To better understand the degree of policy enactment in the nine schools, Coburn’s (Citation2004) categories for five different response mechanisms to macro-level demand for change is also used. Her categorisation identifies different degree of institutionalisation within different responses of teachers entitled rejection, decoupling, parallel structures, assimilation, and accommodation. Here, in line with other scholars, her categorisation is used to analyse the school leaders’ perceptions on teachers’ responses (see also Gunnulfsen & Møller, Citation2017; Liljenberg, Citation2015).

Specifically, the aim of this paper is to understand Icelandic upper secondary school leaders’ actions when leading policy reform in their schools and the way they confront teachers’ responses to change. The paper has a practical orientation for policy makers and school personnel particularly when implementing reform. At the same time, it contributes to the theoretical arsenal by making use of institutional theories within education (Burch, Citation2007; Chen & Ke, Citation2014), adding to their scope. The research questions are as follows:

How do school leaders in upper secondary schools perceive and describe the policy enactment in their schools carried out by the teachers, and how can the policy enactment be classified?

What kind of agency, power, and vision do school leaders describe having and to what extent do they operate as institutional or organisational leaders?

2. Upper secondary education in Iceland and the underlying reform

The schools in this study are part of upper secondary education in Iceland. The study programmes offered at this school level usually take three or four years to complete. Therefore, most of the students are aged between 16 and 19 (Jónasson & Óskarsdóttir, Citation2016). The state is obligated to provide this level of schooling until the age of 18 and operates almost all upper secondary schools. The role of upper secondary education is to educate students for democratic citizenship and to prepare them for life in general. It is also meant to educate students to enter university and prepare them for the labour market (Upper Secondary Education Act No. 92/Citation2008).

The upper secondary education in Iceland has been in continuous, but rather slow, development throughout last century (Ragnarsdóttir, Citation2018a). As noted, the latest major shift came from legislation in 2008 (Upper Secondary Education Act No. 92/Citation2008) and the National Curriculum Guide in 2011 (Ministry of Education, Science and Culture [MoESC], Citation2012). The source of the reform can partly be attributed to international comparison and policy trends (Althingi, Citation2006–2007; Finnbogason, Citation2013; MoESC, Citation2014; Ragnarsdóttir & Jóhannesson, Citation2014) but also to a decades-long debate on shortening the length of matriculation examinations (Ragnarsdóttir, Citation2018a).

The reform contained at least six notable changes from previous educational legislation and national curricula (MoESC, Citation1999; Citation2012; Upper Secondary Education Act No. 80/Citation1996; Upper Secondary Education Act No. 92/Citation2008). The first was exchanging a centralised curriculum from 1999 with a more decentralised and open curriculum. Schools were expected to write their own curricula, create educational programmes, and develop subjects based on the school’s specialisation. The 2011 National Curriculum Guide gives relatively open frame for upper secondary schools and does not discuss the study programmes that were the centre of the previous curriculum in 1999. The existing curricula only counts three compulsory core subjects: mathematics, Icelandic, and English. Only few more subjects are mentioned as part of the matriculation examinations in an addition to the core subjects, natural and social sciences, a third language (traditionally France and Germany), and one of the Nordic languages (commonly Danish). All the subjects are academic. This emphasis on placing some academic subjects higher than others indicates a subject hierarchy, as noted by Ragnarsdóttir (Citation2018b). Lower status academic subjects and subjects of vocational studies and art are, in fact, not mentioned in the national curriculum guide (Eiríksdóttir, Ragnarsdóttir, & Jónasson, Citation2018).

The other five changes stipulated in the reform include a stronger focus on knowledge, skills, and competence-based education. Beyond that, six fundamental pillars were added that cut across programmes and school practices: literacy, sustainability, democracy and human rights, equality, health and well-being, and creativity. Another major change was the possibility to shorten the time to complete academic programmes from four years on average to three years. Outside of the academic programmes, the 2011 curriculum places a stronger emphasis on programmes diversity and more freedom of choice. Finally, it expands the role of the teaching profession to include active participation in school and curriculum development.

As outline above, the policy reform is fundamental and extensive compared the previous reforms taken place on upper secondary education in Iceland. Previously, the focus was to streamline and simplifying the system (see Ragnarsdóttir, Citation2018a).

3. The characteristics of educational change in secondary education

Levin (Citation2013) and Hargreaves and Goodson (Citation2006) note that it is more difficult to implement reform and change existing practises in secondary schools than in schools at lower levels. Levin (Citation2013) explains the difference with reference to school size. He notes that secondary schools are generally larger and not as personal as schools for younger learners. Furthermore, he claims teachers in secondary schools to have a higher degree of autonomy than do teachers at lower levels (see also Hargreaves & Goodson, Citation2006; Ingvarsdóttir, Citation2006; McLaughlin & Talbert, Citation2001). Similarly, as reported by Hansen, Bøje, and Beck (Citation2014), teachers claim that good teaching in upper secondary education rests on teachers’ ability to exercise their own judgement. A further characteristic of upper secondary education is the isolation of individual teachers (Ingvarsdóttir, Citation2006; McLaughlin & Talbert, Citation2001) because they often teach alone instead of in teams.

Subject content is also viewed as part of a teacher’s autonomy in upper secondary schools and, therefore, difficult to change from the outside. Deng (Citation2013) and Thurlings, Evers, and Vermeulen (Citation2015) also focus on subjects and describe how subjects’ matter when making change. They further conclude that subject faculties generally constrain change. Similarly, Harðarson (Citation2010) indicates that mathematics, natural sciences, and history teachers in upper secondary schools in Iceland tend to protect their subjects as independent disciplines, and they mediate traditions through the subjects. From this perspective, Jónasson’s (Citation2016) concerns are relevant when he points out that teachers’ vested interests constrain change, not only due to academic integrity and passion but also linked to their job security and livelihood.

Along similar lines, Levin (Citation2013) notes that secondary schools are more subject oriented than are schools at previous levels and that students generally move between subject experts. He also clarifies how schools are divided into subject faculties, each with a homogeneous group of professionals. Thus, whole school approaches are more difficult to establish in secondary schools than in schools at lower levels. He emphasises three barriers operating in secondary education when change is being promoted:

The way in which the school level is organised around subjects and disciplines,

High content demands and the lack of other important skills and knowledge for everyday life,

The admission requirements from higher education shaping the programmes and the structures at the school level.

Levin (Citation2013) writes about American schools, but his concerns may also apply to upper secondary education in Iceland. In Iceland, the schools are largely organised around subjects and subject disciplines, the focus has been on knowledge-based education for some time, and passing the matriculation examination for academic study paths allows students access to university education (see also Ragnarsdóttir, Citation2018a; Ragnarsdóttir & Jónasson, Citation2020). It is, therefore, interesting to see if the same barriers described by Levin (Citation2013) applies to upper secondary education in Iceland.

A somewhat different perspective on the impact of subjects claims that curricular subjects and subject fields are evaluated differently in society (see e.g. Arnesen, Lahelma, Lundahl, & Öhrn, Citation2014; Bleazby, Citation2015). Subjects like mathematics and physics are, for example, highly valued as being theoretical and abstract. Thus, their mastery is taken as a sign of intellectual superiority while other subjects with more practical and physical emphasises, such as auto mechanics, waiter or sports, are judged to be less demanding and less valuable. Bleazby (Citation2015, p. 671) talks about “the traditional curriculum hierarchy” when referring to this. The subject hierarchy is reinforced by several social structures and actors with vested interests in Iceland (Ragnarsdóttir, Citation2018a, Citation2018b). These controlling forces include tertiary education (Deng, Citation2013; Jónasson, Citation2016; Ragnarsdóttir & Jónasson, Citation2020), parents (Ragnarsdóttir, Citation2018a), society, curricular traditions, and practical vested interest of the teacher profession (Jónasson, Citation2016; Ragnarsdóttir, Citation2018a), to mention a few. Thus, it is important to gauge the impact of the subject hierarchy on educational change.

4. Theoretical and the analytical framework

To analyse how upper secondary schools in Iceland enacted the reform from 2008–2011, sets of neo-institutional theories are used to evaluate the degree of institutional impact during the reform. Those are organisational and institutional leadership (Kraatz, Citation2009; Raffaelli & Glynn, Citation2015; Washington et al., Citation2008) and Coburn’s (Citation2004) five response mechanisms of teachers.

The concepts of organisations and institutions are therefore important for the paper. Organisations form a structural unit with several hierarchical levels and are constructed by individuals performing certain jobs (Ball, Citation1987; Scott, Citation2014). The jobs in this study revolve around school leadership and teaching. The school leaders and the teachers in Iceland have different levels of legal agency and roles stipulated in the regulative structure of the school system (i.e. Act on the Education and Recruitment of Teachers and Administrators of Preschools, Compulsory Schools and Upper Secondary Schools No. 87/Citation2008; Upper Secondary Education Act No. 92/Citation2008). Schools are, therefore, arranged as organisations.

In contrast to organisations, Scott (Citation2014) claims that institutions, have jurisdiction over several levels, such as schools, their subunits, and individuals. Education, as understood in this study, is long-lasting institution, complex, and socially constructed by regulative (such as rules and regulations), normative (i.e. professional roles and norms), and cultural-cognitive elements (like shared conceptions as natural part of social reality). These elements provide stability as diverse actors monitor and constrain the change taking place within the institution. Shared values, norms, and traditions govern education, and within that framework, the existing status quo is maintained, and change is generally constrained (Scott, Citation2014).

Institutions, as defined by Washington et al. (Citation2008), come about more naturally than organisations. Institutions are based on societal needs where the pressure to change or stay the same comes either from external or internal sources. Other scholars agree (Kraatz, Citation2009; Kraatz & Moore, Citation2002; Oliver, Citation1992; Raffaelli & Glynn, Citation2015) and claim that institutions are informal units infused with values and identities emerging from society. They claim that institutions are deeply affected by external contexts and history, the rationale for the institution’s existence and legitimacy. At the same time, they are influenced by internal sources and crises. Interest groups impact what happens within organisations and certain ideology guides the actions there within. Waks (Citation2007) argues that institutions form the background of all the organisations within the same organisational field. The organisational field in the case of this study is the upper secondary school level in Iceland.

Several scholars (Ansell, Boin, & Farjoun, Citation2015; Scott, Citation2014) explain how some organisations develop into self-sustained institutions over time through processes of institutionalisation. After such processes, schools have characteristics of institutions because they are governed by values and honour customs, norms, and traditions that have accompanied education for centuries. When distortion occurs, processes of deinstitutionalisation takes place (Oliver, Citation1992; Scott, Citation2014). Through deinstitutionalisation, stability can transform to a more organic process of change. In such processes, institutions are weakened or disappear. Therefore, change that originates from a policy reform as addressed in this paper, takes place within the organisational characteristics of schools during the process of deinstitutionalisation.

Washington et al. (Citation2008) also leans towards neo-institutional theories, but they focus on leadership. They point out that organisational leaders’ act more like managers, focusing on the function of the organisation and its technical parts, while institutional leaders strive to maintain the homoeostasis of the organisation by protecting its history (see also Kraatz, Citation2009; Raffaelli & Glynn, Citation2015). Therefore, the status quo within the organisations is maintained. The terms are defined and differentiated in .

Table 1. The difference between organisational and institutional leadership (Washington et al., Citation2008, p. 730)

According to the theorists (Kraatz, Citation2009; Raffaelli & Glynn, Citation2015; Washington et al., Citation2008), leaders, in this case school leaders, need to negotiate internal and external interest groups and work in schools with various norms and traditions that guide human behaviour. Washington et al. (Citation2008) explain that institutional leadership is based on “embedded or constrained agency, influence or negotiated power” (p. 720), and usually the vision is to promote and protect the core values of the organisation. In contrast, organisational leadership is when leaders act inside of organisations. Such leadership is based on the ideas “of instrumental agency, hierarchical and charismatic power” (p. 720). Washington et al. (Citation2008) also describe the way in which institutional leaders promote the status quo of their organisations by infusing it with value when defending the existing organisational practices as they manage

the internal consistency … develop external supporting mechanisms that lead to increasing the legitimacy of their organizations … enabling a wide range of interaction inside and outside of the organization … [and how they] must overcome external enemies. (p. 731)

Raffaelli and Glynn (Citation2015) concur by saying that leaders tend to establish and maintain the institutional values of the organisation. In that way, leaders convert organisations into institutions. However, leaders do not act alone in the process of institutionalisation. Other actors promote the same processes. They view an organisational leader as “a rational actor with a narrow and formal role” (p. 288). They point out that interpersonal relationships are incorporated in the social order of institutions. Actions in organisations are governed by norms and beliefs with members whose actions are governed by mission and ideology embedded in their history, traditions, and norms while within the organisational setup they are “role bounded” (Raffaelli & Glynn, Citation2015, p. 288). In such setups, leaders promote their schools as institutions and act as protectors of the integrity of the institution and its values. Institutional leaders cannot, however, look past the administrative part of their organisations. Hence, they also act as administrative managers. Raffaelli (Citation2013) and Besharov and Khurana (Citation2015) present similar views that institutional leaders operate as organisational leaders. Similarly, Dickson, Castaño, Magomaeva, and Den Hartog (Citation2012) note that educational leadership is closely linked to organisational culture and the institutional context of individual schools, but also cross-level influences.

As shown here, the ideas of organisational and institutional leadership go beyond the general understanding of the term leadership. Here, the term includes complex interactions of agency, power, and vision. In general, leadership is seen as a process of social influences where one person, either in a formal or informal leadership position, motivate other individuals or groups towards a common aim (see Hoy & Miskel, Citation2013). The intention of this paper is not to analyse the leadership style of the interviewees but to understand how they act in relation to teachers’ responses when enacting policy reform.

As noted, leaders also need to negotiate internal influences (Washington et al., Citation2008). To better understand the internal influences within the working environment of school leaders, Coburn’s (Citation2004) ideas of different response mechanisms of teachers is useful (see also Scott, Citation2014). She has proposed that diverse responses of teachers within a school can be fruitfully analysed using an institutional and organisational perspective. She uses five mechanisms with varying characteristics () ranked from a high degree of resistance and stability as primary features of institutional influences (see upper part of ) to major changes in school practices as the main features of organisational influences (see lower part of ). This is in line with the ideas behind institutional and organisational leadership. The status quo is maintained within institutional leadership, matching Coburn’s (Citation2004) ideas of the categories of rejection and decoupling. In contrast, organisational leadership goes with the categories of assimilation and accommodation as both categories explain how new ideas are incorporated into educational practises or change it considerably. Related to leadership, Coburn (Citation2005) determined that the principals emphasised that teachers’ learning, and enactment were influenced when reading policy. Teachers were given access to policy ideas and allowed to participate in adding their interpretations and adjustments. The principals also established different learning conditions for the teachers in their schools. All of this was influenced by their own perceptions of how teachers learn and read instructions.

Table 2. Coburn’s (Citation2004) different response mechanisms

The theories of organisational and institutional leadership (Kraatz, Citation2009; Raffaelli & Glynn, Citation2015; Washington et al., Citation2008) and different response mechanisms (Coburn, Citation2004) lean both towards neo-institutional theories and are interrelated. Working with both theoretical lenses open an interesting perspective when analysing school leaders’ actions towards the different response mechanisms from teachers and teachers’ groups within schools. The theories may explain why school leaders cannot have as much impact as they expect to have when leading change.

5. Method

The findings of this study are based on interviews with 21 school leaders from nine upper secondary schools in Iceland who were interviewed individually. The schools and leaders were selected on the basis of stratified sampling with regard to school types and hierarchical structure within the selected schools. The school’s director was always part of the sample along with one or two middle managers. When addressing the interviewees as a group, the term school leaders will be used. All the interviewees had formal leadership roles within the schools.

The school directors at the upper secondary school level in Iceland have a similar role as principals in compulsory schools. They all have a teaching licence and are responsible for the operations and daily administration of the school. They also have the formal authority to organise the school governing structure (Upper Secondary Education Act No. 92/Citation2008). The middle managers in this study had roles within the selected schools such as assistant directors, school registrars, or directors of teaching and learning.

The data collection took place about five years after the changes were launched in 2008 and 2011, or in the autumn of 2013 and spring and autumn 2014. The data give a vignette of the status in the schools at the time. The interviews where semi-structured and supported by an interview framework. The framework covered components related to the reform, school curricula, internal and external influences, leadership, cooperation, and the upper secondary school system. The interviews lasted from 48 to 118 minutes, and all of them where recorded and transcribed word for word.

In this paper, school location, and sizes are not distinguished between to ensure anonymity (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2005). To do this, the selected schools were given pseudonyms (). All of the school leaders, regardless of their actual gender, are referred to as a female to hide their identities, and the roles of the middle managers are not specified (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2005). This study began before the ethical committee approved the ethical guidance for scientific research at the University of Iceland (Research Ethics Committee, Citation2014). Nevertheless, all the criteria discussed in the ethical guidelines have been taken into consideration in this study.

Table 3. List of participants

Thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013) was used to analyse how school leaders perceived the policy enactment in their school and their own actions based on the teachers’ responses. The conceptual framework and the research questions guided the analysis. In the analysis process, the transcripts were carefully read to become familiar with the data and to gain an overview. After gaining an overview, coding took place. Excerpts from the transcript data were collected and the themes were generated. In doing so, the attention was directed towards the different enactments of dissimilar professional groups and individuals within the schools. Then, the school leaders from the same schools were looked at together and excerpts describing their ideas on the implementation processes and the policy enactment within the schools they lead were collected. The conceptual framework grew inductively (Braun & Clarke, Citation2013) when reading new articles.

The Icelandic excerpts were then translated into English. According to Li (Citation2011), translation from one language to another language can raise both ethical and epistemological questions. Therefore, the translated excerpts where carefully adjudicated by a professional translator.

6. Findings

The four themes generated from the data will be presented in order. The first is the theme of inertia primarily facilitating institutional leadership. The second is that contrasting poles facilitate hybrid interactions between institutional and organisational leadership. The third theme is assimilation as primarily facilitating organisational leadership. The final theme revolves around pioneering, which also primarily facilitates organisational leadership.

6.1. Facilitating institutional leadership: inertia and resistance

The most explicit inertia turned out to be in two out of the nine schools. Both of the schools are comprehensive, large in size, and complex. The school leaders explained how they or the teachers in the schools they lead rejected or decoupled from the ideas emerging from the reform. In both cases, inertia primarily facilitated institutional leadership or weak interaction with organisational leadership, as will be explained based on the examples from the school leaders in Brokey and Flatey.

6.1.1 Inertia in Brokey

Brokey was one of the schools in the rejection category. The school director described how she hit walls within the school when she was hired. She came in eager to change, but she soon recognised that Brokey functioned as an institution.

I came surely eager to change … but I soon sensed that … people safeguard the school history … then I learned … to respect the history of the school and figured out that I cannot come into a structure like this and plan to [change it]; the structure is living its own life and has its own being.

It is evident here that she had to be true to the original aims of the school, its predominant culture, existing values, norms, and history. Furthermore, she claimed that teachers were “by nature conservative and so is the schooling”.

When discussing the act and the National Curriculum Guide, the school director clarified that she was not “shouting … hurrah for the new ideology accompanying the new act. I am, of course, more for the older” setup. She explained that, despite of her negative perspective towards the act and the curriculum, she started to implement the change.

Last school year, we aimed at working more on the school curriculum … then … the debate began around it, and the union told us in fact that we should not do this … not for nothing, and we had no money; therefore, we … stopped.

At this point, creation of the curriculum was delayed Brokey. The examples given by the school director indicate how she applied an institutional leadership by silencing and constraining the intended change. Her reason for this was a lack of financial support from the MoESC, insufficient resources, and resistance from the teachers that was supported by the Teachers’ Union.

Moreover, one of the middle managers in Brokey described competition and conflicts between leaders of strong academic subjects when describing the situation in her school.

There, you can find the great conflicts. Everyone wants to promote their teaching subject … this is related to occupational security. My subject is what I want to keep and protect.

Here, she was explaining how the debate about the shorter study time in matriculation examinations programmes in Brokey impacted teachers’ occupational security and livelihoods. The teachers were protecting their own subjects.

The two middle managers in Brokey reflected on the subjects taught when discussing change. One of them claimed that the academic programmes base their work on “old tools … [and have] basically not developed much”. The other middle manager agreed and described how the “struggle and resistance within academic studies” is more as compared to other disciplines in the school. She questioned the content taught in Icelandic. “Should teaching be based so much on literature?” Then she suggested trying “to teach Icelandic as a language … they [the students] just simply … need it”.

The school director in Brokey was more concerned about mathematics when discussing the content of subjects.

It can be … a sensitive matter … to intervene, because also, that is a bit of a tradition … But, I cannot tell mathematicians what they should do or how they should do it; each and every one needs to do as he believes is right.

It is clear here that she was careful and respected the teachers’ autonomy when motivating change.

6.1.2. Inertia in Flatey

The same inertia prevailed among teachers in Flatey. The school director described how the “teachers do not want to change this. They just want to have this as it has always been”. One of the middle managers agreed and explained the debate and inertia as

insecurity and uncertainty … [there will be] fewer positions … So, it is a really fragile state here. People are very defensive and protect their own position.

She was reflecting on the change in the length of study time from four years to three. The teachers in Flatey were protecting their positions and livelihoods. This is in line with the resistance and worries previously discussed in Brokey.

The other middle manager in Flatey agreed with her colleagues and explained how the inertia is linked to the fact that the average age of teachers is relatively high.

The teacher group is aging heavily … it is naturally always people that are thinking about their own comfort zone, always putting themselves in the first place.

The school director reflected often on the resistance and explained how she was trying to implement the ideas from the National Curriculum Guide. She described how she played a game of hide and seek under the banner of professional development when working on the school curriculum to try to motivate teachers and shift their ideas on change. In vivid language, she clarified wanting to

discuss the curriculum … I need to call it education, not policy making. This is obviously a totally impossible situation. This is incredible! I’m going to do something, implement something … discuss, no.

As a consequence of the situation in Flatey, she gathered a closed group of school leaders with similar interests. She explains that she was

working with people who have similar interests as I have, and I maybe feel we are here on a team where there is not much tension, at least not among us that are in this whirlpool of ideas.

Unlike the school director in Brokey who went along with the resistance and applied institutional leadership, the school director in Flatey tried to control the situation through her hierarchical supervision. Therefore, she applied organisational leadership when selecting several middle managers to design and co-write the school curriculum. This she did as a response to intensive teacher resistance. She was missional and authoritative in her actions. Based on her actions, it is also possible to place the school in the decoupling category, as the school director ignored most of the teachers by excluding them from the process. Therefore, the teachers’ responses are categorised as rejection while the school leaders’ responses fall under decoupling when taking over writing the curriculum without having the teachers’ support. The school director justified her actions by stating that the selected administrative group shared the same values as she did. In this case, her actions also corresponded partly to the characteristics of institutional leadership when considering the value aspects of her justification. Therefore, it is possible to conclude her process was hybrid between organisational and institutional leadership.

Similar to the institutional leadership used by the school director in Flatey, the middle manager pointed out how one powerful individual could sometimes block change. Her colleague in the middle manager group

stops [the growth] … we have only one dinosaur that will never do anything, and if the dinosaur is [in the school leadership], then it is extremely difficult.

This example supports the idea of institutional leadership.

When reflecting on the subject hierarchies and inertia, the school director in Flatey discussed a corresponding resistance among mathematics teachers, which perhaps was the subject that elicited the strongest feelings.

I am so interested in mathematics, and I think that I have had a lot of problems with the maths teachers because they do not want to change. There were, of course, such outdated methods being used, outdated material … ancient traditions, outdated textbooks, so dull, so repulsive for a big group of students, such a big portion of Icelandic students, and I would just like to say that math teaching in Iceland is a just a black spot on the Icelandic school system.

As shown in this section, inertia usually facilitates institutional leadership or, at most, weak hybrid interactions between institutional and organisational leadership. Moreover, subject hierarchies are discussed by the school leaders as having huge institutional impact. The subjects are governed by norms and traditions that have accompanied education for a long time. In the case of Brokey and Flatey, the most explicit inertia turned out to be among teachers of mathematics and Icelandic. Both subjects have a fixed, and therefore higher, status in the National Curriculum Guide as compared to the other subjects that are left undiscussed. Resistance to change was not as predominant in the other schools.

6.2. Hybrid interaction between institutional and organisational leadership: parallel structures operating as contrasting poles within schools

The four schools matching the category of parallel structures showed different nuances within the same school. At least two approaches were simultaneously at play in the schools to meet different forces and priorities among groups of teachers as reported by the school leaders. In all cases, parallel structures facilitated hybrid interaction between institutional and organisational leadership. These schools are Akurey, Eldey, Heimaey and Kolbeinsey.

6.2.1. Contrasting poles in Akurey

Akurey was one of the schools with a parallel structure. The school director explained how traditional subjects were merged in new interdisciplinary courses. Cross-curricular topics based on fundamental pillars were the foundation of the courses, and the teachers worked in teams instead of individual teachers working alone in a classroom as before. The middle manager described how they “implemented this interdisciplinary policy … to take people out of their professional trenches”. All of this was in line with the ideas emerging from the National Curriculum Guide. Therefore, Akurey falls partly into the category of accommodation. However, she also pointed out that teachers’ generally “carry on with the old ways and try to adjust them” as far as they can. She explained that it usually takes teachers a long time to crawl out of their “subject holes” and each individual is “protecting his own”. Consequently, the traditional subject teachers only made symbolic changes, thus fitting into the decoupling response.

The school director elaborated more about the subjects and described how

each subject defines [what is needed] … we are shortening the study time; is not this [material] just going to be thrown away? And then the teachers show their claws. Who is going to decide this? And especially older teachers?

She was describing the competition between teachers for which courses would be retained in the shorter study time and which courses would be dropped. Moreover, she blamed the resistant nature of older teachers. Then she explained how it is possible

to enter every subject, both in academic and vocational courses, and find such [views] … This was taught like this when I was in this … This is … classical in my subject. This is the base … in my subject.

Here, she is referring to the institutional walls within each subject in her school. The school director in Akurey particularly focussed on teaching Icelandic.

Icelandic sagas, teachers of Icelandic in upper secondary schools would probably be reluctant to agree to not teach at least one of the sagas … We have not yet broken down these walls.

The leaders in Akurey described characteristics of both institutional and organisational leadership, depending on the groups with which they were working and the tasks they were promoting. The middle manager explained that she saw herself “as an important employee to facilitate change, but at the same time … a conservative element … I need to be solidly in between”. This example shows clearly a strong hybrid interaction between institutional and organisational leadership that depended on school leaders’ priorities and values along with the emphasis of the school staff.

6.2.2. Contrasting poles in Eldey

Eldey was the second school with a parallel structure. The difference, in this case, depended on the age and working experience of the teachers and whether they taught beginning or advanced students.

The middle manager described the situation like this.

These are teachers for advanced students … a core group [of teachers] that took an interest. There was the opportunity. I took it, and we started to change the paths for advanced students, but I left the lower grade programme out.

She further explained how the older group of teachers who taught younger students held the change processes hostage. “It does not take an old teacher an extremely long time to kill” the entrepreneurial spirit. She claimed to have the so-called forty-seven problem, meaning that a disproportionate number of teachers were born in or around 1947 and would soon retire. She described how these teachers work according to “old values and do not want to change … This is blocked by bulldog attitudes in the teachers’ ranks … This affects morale”. The group of teachers teaching the younger students were squarely in the category of rejection.

In contrast, the younger teachers’ group who taught the older students dramatically changed their educational practices, as described by the middle manager.

A team of [N] persons … worked on this change. We worked on this together; we wrote the curriculum when we got the funds to make this change … This team … rewrote all the tasks … So, we had everything ready … There was the core of persons of interest … there was the opportunity; I grabbed it.

She further explained how the teaching and learning methods changed, as well as the working environment and the setup and the organisation of the whole programme. The teachers who taught older students fall under the category of accommodation, involving the deconstruction of existing arrangements. She promoted both institutional and organisational leadership depending on the behaviour of the two different groups of teachers. Those teachers working with younger students resisted change, whereas the teachers with older students made dramatic changes in their educational practices. Her leadership was instrumental and rational when dealing with the teachers who taught older students and silencing and constraining when working with the group of teachers for the younger students.

6.2.3. Contrasting poles in Heimaey

Heimaey also had a parallel structure, but of a different type. The school has a long history and strong academic focus, so its classification comes from a different working culture that depends on school faculty divisions. The leaders also promoted both institutional and organisational leadership depending on the subject faculty with which they worked. The middle manager in the school described how language and social science teachers “have created many new subjects, and the number of interdisciplinary subjects has increased substantially” throughout the development period. As before, these changes fall under accommodation.

The faculties of natural sciences and mathematics in Heimaey complied, however, with the demands for change in the school curriculum in a symbolic and superficial way. They only changed the names of some courses and study paths without changing the teaching practices or the content. The same middle manager noted that they “have essentially not changed the content”. This phenomenon is, therefore, classified as decoupling. The split between the responses from faculty meant that school leaders were both instrumental and rational, as in organisational leadership, and silencing and constraining, as in institutional leadership.

6.2.4. Contrasting poles in Kolbeinsey

Kolbeinsey was the fourth school with a parallel structure. The school is academically oriented and has a long history. The school resisted the shortening idea proposed by the government. The school planned to organise the matriculation programmes with the same number of credits and content as before but in a shorter period.

We aim for 240 upper secondary school credits for matriculation exams that are comparable to what we have today … We do not see the changes in adjacent school levels that we deem necessary to justify the shortening. Besides, the average study time of our students is three and a half years (middle manager in Kolbeinsey).

This was compared to four years for mainstream students in other upper secondary schools. Therefore, the school matched the rejection category when writing the new school curriculum by not changing the content and number of credits taught.

In contrast, both the school director and the middle manager explained how traditional subjects were merged into a new interdisciplinary course for all students in the school. Like the examples given in the other schools, the new course represents deconstructing existing understanding. Hence, this particular response is defined as accommodation.

Nonetheless, the middle manager in Kolbeinsey explained that several traditional “subjects are so compartmentalised”, and the teachers did not want to make any change. This challenge was visible when working on the fundamental pillars as a cross-curricular theme. It was, for example, more difficult to implement the pillars in mathematics and natural sciences as compared to in social science.

Subjects differ when dealing with all these fancy terms that come with the new curriculum … [there is] a little debate here when we are working on the new curriculum. In social sciences, things seem to … work better regarding this matter, but apparently worse in maths and natural sciences (Middle manager in Kolbeinsey).

It is clear that subjects differ when it comes to change in Kobeinsey. The social sciences are more interdisciplinary than mathematics and natural sciences. Hence, the latter subject faculties resisted more.

The leaders in Kolbeinsey moved between institutional and organisational leadership depending on with which group of teachers they interacted with. They were instrumental and rational when supporting the new course. Conversely, they were silencing and constraining with the teachers who resisted the idea of shortening the time of study. In this context, they operated as institutional leaders by reconnecting the school to its original values, strong academic history and traditions. Thus, the school director noted how difficult it was to motivate the whole group. “[S]ome are open and ready, and quite willing to change, but others are not”. With regards to the resistance the middle manager, she wanted “to guide and support rather than control with an iron grip”. She saw herself as a democratic leader and reported how “people have just worked on this very professionally and conscientiously and in cooperation … we take democratic decisions”. As a result, she went with the inertia of the teachers’ group that did not want to change and supported the others.

The school leaders who faced contrasting poles within their schools seemed to realise the double roles they played when leading change or constraining it, and how important it was for them to read the atmosphere and forces at play in each school. Hence, they sometimes acted simultaneously as institutional leaders and organisational leaders depending on the tasks, the school structure, the subject, the faculty culture, and the age and the working experience of the teachers.

6.3. Facilitating organisational leadership: assimilation as active and harmonious development

Drangey was the only school with a long history of enacting the reform to a greater extent than the other schools, thus matching the characteristics of assimilation. The school leaders faced less inertia as compared to the other school leaders and emphasised democratic processes and trust when leading the change. The school director explained the considerable change the teachers made. Nonetheless, she clarified how they fit the new ideas into Drangey’s existing system: “[i]t was really just the sincere wish of the staff here to keep the class-based system, it is just what the kids are pursuing”. Therefore, the school tailored its response to its reality. However, a major change occurred in the school with the deconstruction of existing understandings and matched the assimilation category.

The leaders in Drangey showed all the characteristics of organisational leadership. The school director focused on the professional capital and empowerment of the teaching profession.

When we were working on the curriculum, we transferred the power systematically to the groups and interdisciplinary work … The teachers are great experts.

She further described how everyone needed to

rethink their own contribution from the start [of the change] and let go … At one time, I asked everyone to vote on whether we should start the change or not. People unanimously agreed … We are on this journey [together], and … as I said, everyone is really working on it; there is disagreement of course, but you see, everyone is still on board.

She, however, reported the importance of taking the lead.

I do not have a decision-making phobia … I want everyone to feel that I stand by my people … I feel like I am working with really nice people and great experts. I feel that I am leading the group instead of being … their commander.

By doing that, she supported her staff in a warm and constructive way. At the same time, she promoted top-down and bottom-up approaches. Her leadership agency was mainly instrumental and radical. The power was hierarchical and supervisory when necessary. She saw her role as moving the school forward to new aims and challenges, while trusting the teachers to make changes and highly respecting their expertise. She emphasised working orthogonally up the hierarchical ladder in the school, mainly matching the category of organisational leadership. The change seemed to be enacted quite holistically in the school while respecting the school’s history and legacy. She demonstrated the characteristics of charismatic leaders. However, the school personnel decided democratically to keep the existing system in the school. In that way, the school director and her personnel acted politically regarding the system in which the school operated. As institutional leaders, they also emphasised the importance of school history.

6.4. Facilitating organisational leadership: pioneering mechanisms are free from long-lasting institutional cultures

The two remaining schools, Grímsey and Jökuley, enacted the ideas emerging from the policy reform to a greater extent than the other schools. When the study was conducted, the schools had recently entered the organisational field of upper secondary education in Iceland. They were creating their own way of working in isolation from what was already known and generally accepted. Because of this, these schools did not fit within Coburn’s (Citation2004) categories. Therefore, these schools were placed in the new category of pioneering. The leaders in those schools fit into the category of organisational leadership.

6.4.1. Pioneering in Grímsey

The school director in Grímsey described how “all the attention and energy has been spent on developing teaching methods”. She had been promoting a learner-centred pedagogy, information technology, and formative assessment as a whole-school approach. These approaches were rarely part of the existing norms within upper secondary education in Iceland at the time and infrequently part of traditional practises.

She described how she hired “only young teachers” when she established the school to be able to cultivate them as change agents vis-à-vis the school philosophy and mould them around the school policy. “Almost no one comes with [baggage]. These people are so young”, she explained. She further clarified that “they are not looking … at the things from the larger context” of salary structures, demands made by the Teachers Union, etc., all institutional traditions and values that tended to guide the teachers’ behaviours in other schools. The teachers had no history to protect due to how new the school was and how inexperienced the teachers were as compared to the teachers in the other schools. The middle manager agreed with the school director. She pointed out how fortunate they were not to have “an old teachers’ lounge” reinforcing the old tradition of upper secondary schooling.

The leaders of Grímsey outlined an example that matched the processes of institutionalisation. The school director was “disturbed by the fact that soon we will stop” the entrepreneurial spirit. Based on what she said, it is possible to conclude that Grímsey has slowly changed into an institution. She talked about the challenges involved in the growth of the school and in gaining in reputation and legitimacy on the one hand, and maintaining the innovative spirit, on the other.

We have kept this going until this term … It is a little bit difficult to keep up the situation … that we are one discussion group, we have started to feel that … I of course also feel it socially within the group of the employees … that the group has started to break up into smaller units which is new to us … so we face challenges as well.

The school director further discussed time it takes to make a change and noted that

when starting a new school, several years are needed, maybe up to ten years, to create a reputation, and that was naturally the case here, during the first years.

Moreover, she reflected on the importance of ownership. She added active participation of employees and the important role of school leaders in educational change. She pointed out that school leaders “must lead” the change, but at the same time, be able to create opportunities for ownership. “It is important that the group owns the idea and the implementation, then you must always, somehow, be able to do both” lead and create the opportunity for ownership. She continued to say how time-consuming active participation of all the employees is “because everyone is part of all actions”, but she found it worth it. Regardless of how time-consuming it is, she stressed that she was “not going to stop”, as she strongly believed in the active participation of her employees. Here, she clearly explained how she acted as an organisational leader when leading the school towards change and common aims.

6.4.2. Pioneering in Jökuley

The school director in Jökuley, claimed that the National Curriculum Guide was “the biggest gift the Icelandic nation has had”. She explained the considerably different pedagogical practises in her school. She gave examples of major content changes and claimed that it was “part of the job … each term to have new courses” and new activities. Here, she explains ideas matching organisational leadership when describing her ideas to constantly redesigning the aims. In that way, she saw her school as organic in all processes, seeking ongoing change:

In most cases, change is our habit … those who are used to a status quo situation … become extremely tired of change, they feel bad and are uncertain, they do not feel secure. I knew from the beginning that I needed to keep it like this, and especially after three years, to establish a continuation.

She saw three years as a “warning”. After three years, it was important to make another change to prevent stagnation and institutionalisation.

In keeping with the school leaders in Grímsey, the school director described her hiring ideology and talked about how lucky she was “to be able to hire people who know what to expect, knowing that they are entering a certain system. They need to be ready for it”. Thus, they are “in a different position than other upper secondary schools … We start in” a new system, and the school is new. The middle manager in Jökuley agreed and was aware of her own privilege in not leading teachers where traditions, norms and old values were at play. She stated that “it is just not the same, establishing a new school and changing a school. There is a vast difference”.

To be pioneering, as is evident in Grímsey and Jökuley, a school must be relatively new and designed around a specific vision and certain pedagogy led by the vision of the school leaders, constructed by the younger generations of teachers and a new policy reform as is evident in the data. The reform is almost completely enacted as the schools are only vaguely modelled on existing educational traditions.

7. Discussion

The aim of the paper was to understand how upper secondary school leaders in Iceland experienced teachers in their schools enacting the policy reform from 2008 and 2011 and consequently how they, as school leaders, responded. The paper focussed on two questions which are discussed in the following sections.

7.1. Divergent responses to policy initiatives: Polarisation between and within schools

The first question is twofold. Firstly, it underlines how the school leaders described the policy enactment in their schools and, secondly, looks at a possible way to classify this perceived policy enactment. Thus, the parts are closely interrelated.

Several scholars explain how reform promoted by macro-level actors does not always succeed in schools (see Coburn, Citation2004; Gunnulfsen & Møller, Citation2017; Ragnarsdóttir & Jóhannesson, Citation2014). In this context, Ball et al. (Citation2012) explains how each school challenges the intended reform. This emerges in this study. Some of the school leaders described what they saw as the conservative nature of the teaching profession. Others pointed specifically to the older generation of teachers and blamed them for blocking the intended change. Still others discussed the subject traditions and the social structure of the education system. Together, the diverse forms of inertia reinforce the institutionalisation of upper secondary education and protect the existing norms and traditions in the system (Scott, Citation2014). It is, however, important to bear in mind that some schools, and subject faculties within other schools, and some individual teachers, made considerable changes based on the policy reform, as described by the school leaders. When discussing the change, it was common that they emphasised the younger generation of teachers. They saw this group as being more innovative and desiring change.

Some school leaders felt that the National Curriculum Guide (MoESC, Citation2012) protected existing practices rooted in the institutional regulative structures (Scott, Citation2014) for the school level, the setup of the upper secondary schools, and the education system in general. This is in line with Deng (Citation2013), who describes how the curriculum establishes “an institutionally defined field of knowledge and practice for teaching and learning” (p. 40). Similarly, Jónasson (Citation2016) reports on the solid structure of the curriculum and adds that it is deeply grounded in norms and traditions of cultures and nations. Levin (Citation2013) equally emphasises the curriculum when reflecting on barriers to change in secondary education, particularly how subject orientated the school level is.

Moreover, the school leaders reported that the subject hierarchy hindered creativity, maintained stagnation, and placed unequal weight on subject fields. These findings are in line with recent studies. Luke, Woods, and Weir (Citation2013) notes, for example, that academic outcomes are a predominant factor in education. In this regard, Thornton, Ocasio, and Lounsbury’s (Citation2012) reflections on social structures are relevant. They claim that some actors misuse their power systematically when creating social structures based on their self-interests.

As highlighted by the school leaders, teachers of higher status subjects tended to show more inertia as compared to those who taught lower status subjects. The high-status academic subjects are deeply rooted in traditions and norms across the system boundaries of education. The institutional characteristics are most explicit in mathematics, the natural sciences and Icelandic, as is clearly reflected in the findings. The subjects are socially structured phenomenon reinforcing institutionalisation and stagnation and are protected by the vested interests of powerful actors (Scott, Citation2014) within education. This inertia can be linked to Bleazby’s (Citation2015) ideas of subject hierarchy.

Similarly, Braun, Maguire, and Ball (Citation2010) pointed out that the hierarchal position of schools also matters when enacting policy. Schools with a high degree of legitimacy and self-reliance tend to control the changes taking place in education, as was true for some of the schools in this study. Bjarnadóttir and Geirsdóttir (Citation2018) come to a similar conclusions about different subject cultures within the same school. They claim that this particularly applies to traditional grammar schools with long histories. This study shows some similar patterns within comprehensive schools and a gap between study paths.

The response mechanisms of Coburn (Citation2004) demonstrate different components of institutional stability and organisational change. The schools matched three out of five of Coburn (Citation2004) response mechanisms. The categorisation is summarised in . As demonstrated in the left part of the figure, two of the schools matched the rejection category. The same partly applies to the four schools categorised under parallel structures, as is shown in the left part of the second box in . As is indicated in the right part of the second box in , more change was made in some departments of the same four schools. It is also clear, based on the number of schools within the parallel structure category, that many self-contained sub-units are apparent within the same school. All of the six schools previously discussed have a long history and relatively robust, long existing cultures, indicating that the predominant governing structure of upper secondary schooling in Iceland is within the institutional characteristics of education (Scott, Citation2014). Only one of the older schools conformed to the reform to a greater extent than the other schools, and the school leaders gave examples matching the assimilation. Finally, two of the newest schools showed what was categorised as pioneering characteristics, the proposed addition to Coburn’s (Citation2004) five categories of response mechanisms.

Figure 1. School leaders’ perceptions of teacher’s responses to ministerial demand to change: Different response mechanisms

The pioneering schools had recently entered the organisational field of upper secondary education in Iceland and did not have a long history. They were not in the position of changing existing practises and traditions, as was the case for the other schools. The school leaders working in the two schools explained how they hardly faced any inertia among the teachers. They, in cooperation with the teachers, used their own novel ideology of upper secondary schooling, partly based on the ideas from the reform. It is possible to conclude that the change promoted in the two schools was scarcely directed by any pre-existing or dominant ideology and hardly any existing institutional values and traditions that generally form the educational background of upper secondary schools in Iceland. Within that framework, organisational dynamics dominate.

The pioneering category strengthens Coburn’s (Citation2004) existing categories by including new schools entering the organisational field of education. These schools were not changing existing cultures as they were newly established. Instead, they were constructing their own ideas, many of which were part of the policy reform. Those two schools clearly showed characteristic of organisational governance (Ball, Citation1987; Scott, Citation2014; Washington et al., Citation2008). The school leaders corresponding to the pioneering category faced less, or hardly any, inertia from the teachers as compared to the other school leaders. They were conscious of their privilege to lead a newly established school lacking traditions, norms, and a controlling institutional culture.

The response mechanisms introduced by Coburn (Citation2004) are clearly found to be a helpful tool to better understand what governs policy enactment in schools and give ideas on how deep the existing system is actually rooted in the history, norms, and traditions of upper secondary education (Scott, Citation2014).

7.2. The school leader’s agency, power and vison reflect the polarisation between and within the schools

The second research question explores the school leaders’ perceived agency, power, and vision as core components of the theories explaining institutional and organisational leadership (Kraatz, Citation2009; Raffaelli & Glynn, Citation2015; Washington et al., Citation2008). Together with the ideas introduced in Coburn (Citation2004) response mechanisms, the leadership component elucidates how school leaders interact with the prevailing culture in the schools they lead and explains why they cannot, as leaders with a substantial mandate, fully promote their ideas.

As described, the most explicit inertia turned out to be in two out of the nine schools. In both cases, inertia primarily led the school leaders to act as institutional leaders (Kraatz, Citation2009; Raffaelli & Glynn, Citation2015; Washington et al., Citation2008). The traditions and histories of the schools were protected (Washington et al., Citation2008). Also, four schools out of nine matched the category of parallel structures. Within the schools, at least two approaches were simultaneously at play. When such contrasting poles were at force, the school leaders explained hybrid interactions between institutional and organisational leadership (Besharov & Khuran, Citation2015; Kraatz, Citation2009; Raffaelli, Citation2013; Raffaelli & Glynn, Citation2015) to meet different forces and priorities among groups of teachers in the schools. Finally, one of the nine schools matched the assimilation category and two were pioneering schools. The school leaders in these three schools gave examples of how they primarily acted as organisational leaders (Washington et al., Citation2008).

This indicates that most leaders saw themselves at the frontline of changes, which is in accordance with many scholars (see Barsh et al., Citation2008; Hargreaves & Fullan, Citation2012), acting as organisational leaders and describing their educational visions and desires for change. Nonetheless, they were wedged between political ideas and interests, the professional ideas of various groups, and the vested interests of other groups. When dealing with this diversity, they acted as institutional leaders (Washington et al., Citation2008). Thus, their visions and ideas about the reform were, in some cases, not accepted as they could not manage to convince the teachers. This indicates that the leaders were blocked from going beyond where prevailing culture allowed them to go. Individual teachers, subject groups, or complex social structures hindered or modulated the school leaders as change agents. Ragnarsdóttir (Citation2018b) agrees when analysing interviews with teachers from the same study. The teachers showed more inertia to change as compared to the school leaders. Thus, school leaders only have partial agency (Scott, Citation2014) and limited power (Washington et al., Citation2008) and authority (Thornton et al., Citation2012) to promote change and act within the more established schools.

The school leaders felt that they had the agency to interfere with pedagogical tools and encourage pedagogical renewal. They, however, did not have the agency to interfere with the subject content, despite having both the will and strong opinions about outdated content and textbooks. They indicated that most subjects have a legacy that is very difficult or impossible to influence, and they made it explicit that the strongest institutionalisation occurs in mathematics.

The divide between institutional and organisational leadership says nothing about the leadership style that the school leaders aim to promote or claim to use. Instead, their reactions seem to be based on the cultural control within the schools (Scott, Citation2014). Raffaelli (Citation2013) agrees, indicating that leaders act both as institutional leaders and agents of change. Besharov and Khurana (Citation2015) and Raffaelli and Glynn (Citation2015) state that institutional leaders also operate as organisational leaders when they carry out administrative work. They see organisations and institutions as “holistic patterns of systems, structures, goals and other arrangements and, as a result, should reveal a distinctive and different set of associated values” (p. 290).

8. Conclusion

Several scholars claim that researchers, mainly in the field of education, neglect some of the theoretical lenses that are used in this paper (see Burch, Citation2007; Chen & Ke, Citation2014; Kraatz, Citation2009; Raffaelli & Glynn, Citation2015; Washington et al., Citation2008). This paper attempts to contribute to their call by contextualising the relationship between the concepts of organisations and institutions, mainly the interactive processes taking place between the two. The concurrent notions of organisational and institutional leadership are also essential, since leaders are expected to direct change and develop schools as organisations, while the institutional context that permeates them is usually not considered. Additionally, the study suggests adding the concept “pioneering” to the already existing theoretical arsenal of response mechanisms (Coburn, Citation2004).

Some of the challenges accompanying the institutional characteristics of subjects should also be brought within the purview of education research on policy enactment and change processes. It is important for policy makers, school leaders, and teachers to understand the institutional grip of subjects when leading and enacting reforms while also considering a school’s culture and origin. The institutional characteristics of each subject explains why school leaders have limited to no agency (Scott, Citation2014; Washington et al., Citation2008) when attempting to lead change in the content of certain subjects, despite having strong views on how outdated such content may be. Moreover, policy makers, school leaders, and teachers also need to be aware of their own roles in institutionalising education when they choose what remains the same and what should change.

Data collection

The data consist of 130 classroom observations; over 60 transcribed interviews with students (group interviews), teachers, and school administrators; photographs of classrooms; syllabi; and other written records. Fifteen researchers from the School of Education and the School of Social Sciences in the University of Iceland participated in data collection.

Acknowledgments

Our special thanks to the upper secondary schools that provided us with access to data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Guðrún Ragnarsdóttir

Guðrún Ragnarsdóttir ([email protected]) is an associate professor in the Faculty of Education and Pedagogy, School of Education, University of Iceland. Guðrún holds a BSc degree in biomedical science and two diplomas, one in in education and another in public administration. She has also completed a master’s degree in public health and a PhD in education from the University of Iceland, School of Education. Guðrún has worked as a primary school teacher, upper secondary teacher and a school leader, as well as having been employed as a teacher trainer for the Council of Europe. Her research interests include pedagogy, school development, professional development, mentoring, and school leadership.

References

- Act on the Education and Recruitment of Teachers and Administrators of Preschools, Compulsory Schools and Upper Secondary Schools No. 87/2008. Reykjavík: Althingi. Retrived from https://www.althingi.is/lagas/nuna/2008087.html

- Adolfsson, C.-H., & Alvunger, D. (2020). Power dynamics and policy actions in the changing landscape of local school governance. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 6(2), 128–142.

- Althingi [The Parliament]. (2006–2007). Svar menntamálaráðherra viðfyrirspurn Björgvins G. Sigurðssonar um brottfall úr framhaldsskólum [The education minister’s answer to a parliament member’s inquiry about dropout from upper secondary schools]. Retrieved from http://www.althingi.is/altext/130/s/pdf/1406.pdf

- Ansell, C., Boin, A., & Farjoun, M. (2015). Dynamic conservatism: How institutions change to remain the same. In M. S. Kraatz (Ed.), Institutions and ideals: Philip Selznick’s legacy for organizational studies (pp. 89–119). Bingley: Emerald.

- Arnesen, A.-L., Lahelma, E., Lundahl, L., & Öhrn, E. (2014). Unfolding the context and the contents: Critical perspectives on contemporary Nordic schooling. In A.-L. Arnesen, E. Lahelma, L. Lundahl, & E. Öhrn (Eds.), Fair and competitive? Critical perspectives on contemporary Nordic schooling (pp. 1–19). London: The Tufnell.

- Ball, S. J. (1987). The micro-politics of the school: Towards a theory of school organization. London: Methuen.

- Ball, S. J., Maguire, M., & Braun, A. (2012). How schools do policy: Policy enactments in secondary schools. London: Routledge.

- Barsh, J., Capozzi, M. M., & Davidson, J. (2008). Leadership and innovation. MacKinsey Quality, 2008(1), 37–47. Retrieved from http://fcollege.nankai.edu.cn/_upload/article/16/b8/df9c1562464086198aace3a57543/ffa06968-12af-4a4f-a312-71da0774e8bd.pdf

- Besharov, M., & Khurana, R. (2015). Leading amidst competing technical and institutional demands: Revisiting Selznick’s conception of leadership. In M. S. Kraatz (Ed.), Institutions and ideals: Philip Selznick’s legacy for organizational studies (pp. 53–88). Bingley: Emerald.

- Bjarnadóttir, V. S., & Geirsdóttir, G. (2018). You know, nothing changes’. Student influence in upper secondary schools in Iceland. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 26(4), 631–641.

- Bleazby, J. (2015). Why some school subjects have a higher status than others: The epistemology of the traditional curriculum hierarchy. Oxford Review of Education, 41(5), 671–689.

- Braun, A., Maguire, M., & Ball, S. J. (2010). Policy enactments in the UK secondary school: Examining policy, practice and school positioning. Journal of Education Policy, 25(4), 547–560.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research. A practical guide for beginners. London: Sage.

- Burch, P. (2007). Educational policy and practice from the perspective of institutional theory: Crafting a wider lens. Educational Researcher, 36(2), 84–95.

- Chen, S., & Ke, Z. (2014). Why the leadership of change is especially difficult for Chinese principals: A macro-institutional explanation. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 27(3), 486–498.

- Coburn, C. E. (2004). Beyond decoupling: Rethinking the relationship between the institutional environment and the classroom. Sociology of Education, 77(3), 211–244.

- Coburn, C. E. (2005). Shaping teacher sensemaking: School leaders and the enactment of reading policy. Educational Policy, 19(3), 476–509.

- Deng, Z. (2013). School subjects and academic disciplines. The differences. In Í. A. Luke, A. Woods, & K. Weir (Eds.), Curriculum syllabus design and equity. A primer and model (pp. 40–53). New York: Routledge.

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). The Sage handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Dickson, M. W., Castaño, N., Magomaeva, A., & Den Hartog, D. N. (2012). Conceptualizing leadership across cultures. Journal of World Business, 47(4), 483–492.

- Eiríksdóttir, E., Ragnarsdóttir, G., & Jónasson, J. T. (2018). Þversagnir og kerfisvillur? Kortlagning á ólíkri stöðu bóknáms- og starfsnámsbrauta á framhaldsskólastigi [On parity of esteem between vocational and general academic programs in upper secondary education in Iceland]. Netla – Veftímarit um uppeldi og menntun: Sérrit 2018 – Framhaldsskólinn í brennidepli [Netla – Online Journal on Pedagogy and Education]. University of Iceland, School of Education. Retrieved from http://netla.hi.is/serrit/2018/framhaldskolinn_brennidepli/07.pdf

- Finnbogason, G. E. (2013). Lyklar framtíðar. Lykilhæfni í menntastefnu Evrópu og Íslands [Keys to the future. – Ideas on key educational competences in Europe and Iceland] [ Netla]. Online Journal on Pedagogy and Education [ Special issue 2016]. Retrieved from http://netla.hi.is/serrit/2016/menntun_mannvit_og_margbreytileiki_greinar_fra_menntakviku/002.pdf

- Gunnulfsen, A. E., & Møller, J. (2017). National testing. Gains or strains? School leaders’ responses to policy demands. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 16(3), 455–474.

- Hansen, D. R., Bøje, J., & Beck, S. (2014). What are they talking about? The construction of good teaching among students, teachers and management in the reformed Danish upper secondary school. Education Inquiry, 5(4), 583–601.

- Harðarson, A. (2010). Skilningur framhaldsskólakennara á almennum námsmarkmiðum [How teachers in secondary schools understand the general aims of education]. Journal of Educational Research (Iceland), 7, 93–107.

- Hargreaves, A., & Fullan, M. (2012). Professional capital: Transforming teaching in every school. London: Routledge.

- Hargreaves, A., & Goodson, I. (2006). Educational change over time? The sustainability and nonsustainability of three decades of secondary school change and continuity. Educational Administration Quarterly, 42(1), 3–41.

- Hoy, W. K., & Miskel, C. G. (2013). Educational administration (9th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Ingvarsdóttir, H. (2006). “… eins og þver geit í girðingu“. Viðhorf kennara til breytinga á kennsluháttum“. Viðhorf kennara til breytinga á kennsluháttum [“… like a stubborn goat in a fence.” Teachers perceptions on changed teaching methods]. In Ú. Hauksson (Ed.), Rannsóknir í félagsvísindum VII, Félagsvísindadeild (pp. 351–363). Reykjavík: Félagsvísindastofnun Háskóla Íslands.

- Jónasson, J. T. (2016). Educational change, inertia and potential futures. Why is it difficult to change the content of education? European Journal of Futures Research, 4(7), 1–14.

- Jónasson, J. T., & Óskarsdóttir, G. (2016). Iceland: Educational structure and development. In T. Sprague (Ed.), Education in non-EU countries in Western and Southern Europe (pp. 11–36). London: Bloomsbbury.