ABSTRACT

In secondary school geography lessons, students are encouraged to form argumentatively founded opinions on complex geographical conflicts. For these conflicts, there is no one right solution and the content quality of the argumentation lies especially in the multi-perspective approach to the conflict and the integration of spatial information. The Internet offers a wealth of multi-perspective and spatial information on a great number of geographical conflicts worldwide. However, the digital information is neither checked nor filtered nor didactically prepared. This study examined the ability of 20 German secondary school students in developing arguments on a complex geographical conflict after searching the Internet for information. The students’ information search and their concurrent verbalisations were taped using screen and audio capture technology. The developed arguments have been assessed using defined criteria for argumentations on geographical conflicts. The analysis of the arguments showed that the students included a range of perspectives , which suggests that they were able to use the Internet as a source for obtaining multi-perspective information on the conflict. However, whilst effective digital information retrieval was the pre-condition in understanding the geographical conflict, it has not shown to guarantee the development of a high-quality argumentation.

1. Introduction

The term conflict describes “an opposing or problematic clash of multiple interests or positions within and among persons, groups, institutions, states, and other associations of persons” (Oßenbrügge, Citation2001). Geographical conflicts in particular, can be defined as spatial conflicts of interest, which are complex when they consist of several interrelated elements that are in a spatio-temporal dynamic (Budke & Müller, Citation2015, p. 177). A well known example of a complex geographical conflict, which could thus be analysed and discussed by students in geography lessons, would be whether the Amazon rainforest should be further developed. Understanding such a conflict and forming a reasoned judgment on the subject poses special difficulties for students, as they need to connect natural conditions with human activities and compare different interests and actors (DGFG, Citation2014, p. 5–6). Students need to be able to identify the multiple perspectives involved in a conflict, i.e. interest groups with ecological concerns or economic benefits, analyse spatial conditions, and recognise temporal developments as well as the current state of the issue. Dealing with such geographical conflicts constitutes a problem-solving process that is likely to enhance skills involved in forming an argument, may increase the students’ abilities to form opinions and challenge their personally held views and conceptions (Kuckuck, Citation2015, p. 77).

Using the Internet to search for information in geography education offers both opportunities and challenges: on the one hand the Internet offers authentic, multi-dimensional information on almost all geographical conflicts. Spatial information can be gathered using digital web-mapping services, pictures and videos. Current and historical information is available online to present the latest state of the conflict and to trace developments through time. Furthermore, the digital search for information ties in with the students’ relationship to the world around them, as the Internet, most commonly the use of search engines and Wikipedia, has become students’ primary source of information outside school (Purcell et al., Citation2012, p. 4). On the other hand, the large amount of unfiltered, unevaluated information available on the Internet provides special challenges for students, as information has to be found, filtered and critically evaluated. It has been shown that German students are facing major difficulties in retrieving and evaluating online information (Eickelmann et al., Citation2019, p. 125).

Information searches on the Internet, conducted in classroom settings, provide teachers with opportunities to support their students’ digital information literacy by improving their Internet research strategies and raising their awareness of how to deal with digital information. However, the computer can only be a tool for teachers if they themselves are trained in digital literacy, if they change their pedagogical strategies, deepen their subject knowledge and take into account the students’ abilities (Kroksmark, Citation2015, p. 124).

It is not yet understood how students form their own justified opinions of complex geographical conflicts using information they have gathered from the Internet. Consequently, this study looked at the extent to which information search on the Internet influences the quality of a subsequent argument.

Therefore, this study aims to address the following research questions:

To what extent are students able to develop their own reasoned judgment on complex geographical conflicts using information found on the Internet?

Does the students’ success in finding useful information during the Internet search influence the quality of their subsequent arguments?

2. Argumentation in geography education

2.1. Subject-specific guidelines and the implementation of argumentation in geography lessons

The German Educational Standards of Geography (Citation2014) define skills in forming arguments as a part of the competence areas ‘communication and evaluation’. These describe that geography education should, among others, enable students to “analyse and compare the logical, subject-specific and argumentative quality of statements”, to “express subject-specific opinions in a discussion in a well-founded and target-oriented manner” and to “evaluate relevant facts and arguments on the basis of criteria [and] reflect on values” (DGFG, D. G. für G. (Ed.), Citation2014, p. 29). Discussing geographical conflicts, specifically, to “make a reasoned judgment/formulate a reasoned opinion on a given issue by weighing up pro and contra arguments” (ibid. pp. 28–29) is classified as the highest level of difficulty (performance level III). Besides the promotion of argumentation and evaluation skills, the use of argumentation in geography lessons also fosters the understanding of subject content and positively influences the students’ social and affective skills, such as the ability to interact and compromise (Budke & Meyer, Citation2015, p. 14).

In geography, the majority of open-ended arguments are focused on controversial issues, such as rainforest exploitation and climate change. Unlike other disciplines, such as mathematics in which the correctness of an assertion is demonstrated with proof (Tebaartz & Lengnink, Citation2015, p. 105), there is often no forgone conclusion to these geographical conflicts. The enhancement of judgment competence and argumentation skills of controversially discussed geographical issues should already take place in the first years of geography education (grade 5 and 6), by initially teaching students to weigh the pros and cons of such conflicts against each other. By the beginning of higher secondary school, students should then be able to discuss spatial developments independently, weighing up various pro and con arguments (Ministerium für Schule und Bildung & des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen, Citation2019, p. 18, 24). The discussion of ill-structed problems is not unique to geography education, as other school subjects may focus on political-, historical-, or socioscientific issues. However, geographical conflicts are special in that they are space-related, social conflicts. A judgment on the conflict requires both, factual and normative arguments to be formed. Geographical arguments can be described as being of high quality when different perspectives, such as ecological concerns and economic benefits, are included in the argument and when the reasoning focusses on the spatial conditions (Budke et al., Citation2015, p. 276).

In 2010, a classroom observation study of 1414 geography lessons revealed that argument development took place in less than 10% of the lessons. Interviews with geography teachers showed that they seemed to be only partially aware of the importance of argumentation in geography lessons (Budke, Citation2012, p. 25–34). However, over the last decade, argumentation has become increased attention in the research field of geography education. Various studies have been conducted on the implementation of argumentation in geography lessons, for example to solve geographical problems (Dittrich, Citation2017), to comprehend complex human-environment systems (Müller, Citation2016), to better understand social discourses (Kuckuck, Citation2014), and to answer spatial planning tasks (Budke & Maier, Citation2018). In addition to the possibilities of implementing argumentation in geography education, research has also brought to light some of the difficulties that students have in arguing geographically: starting with problems in understanding an assignment and the information in text and visual sources, students also had difficulties using the correct geographic terminology (Dittrich, Citation2017, p. 233). They further showed structual and content-related shortcomings in the production of coherent arguments on complex geographic conflicts (Uhlenwinkel, Citation2015, p. 59) and also in the reception and evaluation of existing geographic arguments (Kuckuck, Citation2015, p. 86).

2.2. Internet searches on complex geographical conflicts as a basis for developing arguments

By the time German students reach the upper secondary school level, they should have acquired a number of methodological competences (M) in geography lessons, including the following: “Knowledge of sources and forms of information and information strategies (M1), the ability to gather information (M2) and the ability to analyse information (M3)”(DGFG, D. G. für G. (Ed.), Citation2014, p. 18). It is explicitly stated in the educational standards that technical information sources are becoming increasingly important due to their topicality and that strategies for obtaining and evaluating (digital) information must be taught in geography lessons (ibid. p.18).

The Internet is a particularly useful source of information for forming reasoned judgements about geographical conflicts. Conventional sources in geography lessons, such as textbooks and worksheets, cannot achieve the same level of information, as the Internet provides:

Multi-perspective, authentic information for almost all geographical conflicts in digital representations of newspapers, citizen initiatives, party programmes, blogs, social networks etc.

Spatial information available from web mapping services, digital information systems, pictures and videos.

Recent and historical information to track developments and discover the most recent status of a conflict.

When searching for information on geographical conflicts, the students need a high level of competency in evaluation skills, as information is often not “neutral” but is expressed by an actor with a special interest in the issue: for example, when students find information on websites run by citizen initiatives, the information presented there usually serves as arguments to support their own interests.

This engagement with the arguments of others, to comprehend, analyse and assess their point of view, is an important step for students to participate in geographic discourse. Students can only develop their own (counter-) arguments if they are able to understand and evaluate existing arguments (Budke, Kuckuck, & Schäbitz, Citation2015a, p. 368). However, previous research has found that students lack digital evaluation competencies: They tend to trust unknown sources (Stanford History Education Group, Citation2016, p. 17) and rarely critically assess information on websites (Metzger, Flanagin, Markov, Grossman, & Bulger, Citation2015, S. 236). Students are more likely to use the first web pages that are listed in search engine result lists, particularly when they are searching for controversial topics (Walhout, Oomen, Jarodzka, & Brand-Gruwel, Citation2017, S. 1457). Teachers predominantly rate their students’ ability to use multiple digital sources to effectively support their argumentation as “poor” or “fair” (Purcell et al., Citation2012, p. 6).

Another necessary skill that students need when searching for geographical information on the Internet is competency in map reading. Relevant information that is available from online maps, such as the infrastructure and natural conditions for the place of interest, must be found and analysed. Students then need to integrate the information gained from these maps into their argument. However, it has been shown that even prospective geography teachers have deficits with regard to the necessary skills for the development of map-based arguments. These university students showed difficulties in analysing evidence contained in maps and in developing a sufficiently critical stance on the focus of the map (Budke & Kuckuck, Citation2017, pp. 96–101).

Previous research has shown that secondary school students show a wide variety of abilities when searching the Internet for complex geographical conflicts. Although they tend to find a high amount of multi-dimensional information on a conflict, they rarely use maps to analyse the associated spatial conditions. They predominantly do not pay attention to publishing dates of the information to trace developments and to find out about the latest state of the conflict (Engelen & Budke, Citation2020).

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

The study was comprised of 20 students from four secondary schools (“Gymnasium”) located in urban areas in North-Rhine-Westphalia (NRW), Germany. In these schools, geography has been taught from grade 5 onwards. In the upper secondary school level, which the participants in this study attended, the students can then decide whether to drop geography lessons, whether to choose it as a major subject with 5 lessons per week or as a minor subject with 3 lessons per week.

The participating students were in their final or pre-final year, and between 16 and 18 years old, with an equal number of female and male participants. This older age group was chosen as it helped to get an insight into the highest level of possible geographic argumentation skills taught in the context of Internet information search in German schools. The results may be interesting to universities as they obtain an understanding of the geographical reasoning skills of their incoming student cohort. Seven participants chose geography as a major field of study and 17 students indicated they had received very good to satisfactory grades in geography.

Even though dealing with (digital) sources should already be practiced in geography from the 5th grade onwards as part of the acquisition of methodological competencies, none of the participating students stated that they had already been specifically trained in the use of digital information searches on geographic topics.

3.2. Study task and data collection

The study was conducted over a period of about half a year until recurring patterns appeared, so that a certain data saturation was established for answering the study’s research questions. Furthermore, the limited number of 20 study participants allowed an in-depth analysis of the data collected and thus created qualitative results.

The students were asked to form a reasoned judgment on a complex geographical conflict that they have had no previous knowledge of. To achieve this, a conflict was chosen that was taking place in Lower Saxony, Germany, distant from the homes of the study participants. The question was whether a bridge should be built over the River Elbe to connect the towns of Darchau and Neu Darchau (). Currently a regular ferry provides a link between the two places. This study task was particularly suitable for geographic argumentation development as it is a spatial conflict with many different economic, ecologic and social interests involved. The effects of the construction of a bridge have to be evaluated on different scale levels as there are advantages and disadvantages of a bridge for the immediate residents, for companies and commuters in the extended district, but also involve costs for statewide taxpayers.

Figure 1. Assignment for the study taskFootnote1

Information about the conflict is available on the internet on various sites that provide authentic and multi-perspective insights into the conflict, such as the websites of newspapers and citizens’ initiatives, Wikipedia, social networks, video platforms etc. Furthermore, digital web mapping services give the possibility to explore spatial conditions of the area, such as infrastructural facilities and natural characteristics.

The participating students worked individually on the study task and got a time slot of approximately 45 minutes, which equals the length of a German school lesson. All but one student stated afterwards that they had had enough time to complete the task and that they considered their work finished. The students were asked to think aloud while working on the assignment and were allowed to take notes using a digital writing tool or handwritten. The Internet search and concurrent verbalisations were recorded with screen and audio capture technology. This made it possible to watch the entire search process of the students afterwards. The recording not only enables the viewer to trace all the Internet retrieval activities carried out, such as entering search terms, using websites or watching videos, also the cursor movements can be traced as well as all sounds that the students either heard or uttered during their information search.

As the computers in the four different schools were not equipped with the necessary software, and as we wanted to be available in case of possible questions or problems, we either conducted the study in our institution or we were present in the students’ schools while they were participating in the study. In both locations, the students worked individually on our provided notebooks. We made sure that all students had enough privacy, either by working in separate rooms or by creating sufficient space between each work station and separating them with divider walls. Since underage students took part in the study, consent was obtained from the study participants and their parents to participate in the study.

To analyse the results we prepared extended protocols that included not only the students’ argumentations but also the actions of their Internet search, the notes they took while searching and the transcribed concurrent verbalisation. This approach ensured that we could not only evaluate the students’ argumentation in isolation, but also get insights into the students’ researching approaches and link the previous digital information search with the analysis of their arguments. To find correlations between the students’ success in identifying relevant information while searching the Internet and their subsequent argument, we counted all pieces of relevant, credible and factually correct information the students found during their information search. In this way we aimed to determine whether the Internet retrieval strategies and the amount of identified relevant information had an influence on the argument.

3.3. Analysis and assessment of student argumentations

To analyse students’ arguments, the structural framework developed by Toulmin (Citation2003) was used; a scheme that has often been used as a basis for the construction and evaluation of student arguments in educational research studies (cf. i.a. Erduran, Simon, & Osborne, Citation2004; Foong & Daniel, Citation2010; Uhlenwinkel, Citation2015). According to Toulmin, a basic argument consists of a claim, data to prove the claim and a warrant (explicit or implicit) to support the claim (). Further elements of more complex arguments are backings to support the data, rebuttals considering counter-claims and qualifiers indicating the degree of the claim’s strength with words such as “presumably” or “certainly” (Toulmin, Citation2003, pp. 87–118).

Figure 2. Modified Toulmin argumentation pattern (Citation2003). The example given represents an argument from the geographical conflict of the study assignment (authors' own elaboration)

The Toulmin framework helped to break down the student arguments into individual components, analyse how students constructed their reasoning, and check the arguments for structural completeness. It was particularly useful to decode and name the individual elements of the student arguments. We agreed with a previous study on argumentation (Erduran et al., Citation2004, pp. 918–919) in that it is often difficult to distinguish between data, warrant and backing and combined these three elements to one category, justifications, in the assessment.

Alongside structural analysis we examined the argumentations in terms of their content quality, in the sense of geographical reasoning. For this purpose we followed the quality criteria used in an argumentation evaluation scheme for students’ written geographic argumentation, in which completeness, complexity, relevance, accuracy, validity, spatial reference and multiperspectivity were considered as superordinate criteria for the evaluation of geographic argumentations (Budke et al., Citation2015, p. 276; Budke & Uhlenwinkel, Citation2011, pp. 117–121). As structural completeness and complexity has already been analysed within the Toulmin scheme, we further examined whether an argument was relevant to the problem (relevance), whether the data mentioned was correct and precise from a scientific viewpoint (accuracy), and whether the connection between claim and justifications was correct or comprehensible (validity). As it enhances the quality of geographic argumentation, we further analysed whether the students included arguments from different perspectives and actors involved in the conflict (multiperspectivity) and whether spatial conditions of the place of interest have been included in the arguments (spatial reference) (Budke et al., Citation2015, p. 276).

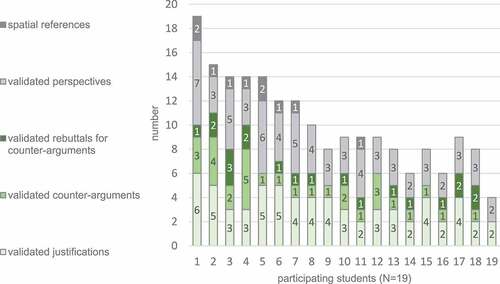

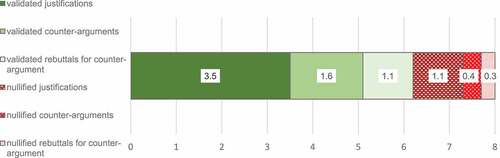

As shown in , we gave a score of 1 point for each validated justification to support the own claim, as a higher number of reasons enhances the argument. This has already proven to be useful in other studies (cf. Barzilai, Tzadok, & Eshet-Alkalai, Citation2015, p. 746; Means & Voss, Citation1996, p. 142). We gave a further score of 1 point for each validated counter-evidence and rebuttal of the counter-evidence, as the use of valid counter-claims increases the quality of the argumentation because it shows the limitations of a justification (Foong & Daniel, Citation2010, p. 1122) and involves consideration of both sides of the argument (Means & Voss, Citation1996, p. 142). An argument was considered to be ‘validated’ when we evaluated it to be accurate, relevant and valid. When students used specific information, such as numbers and figures, we awarded it with an additional 0.5 points each time, as the use of specific information shows a deeper knowledge of the subject and is an indication that that it is not (simply) an assumption by the students but that the information was taken from a source. We further gave an additional 0.5 points when the students related an argument to a particular actor, place or time, as the inclusion of different perspectives, spatial references and conditions that explicitly stated where, when and for whom the respective argument applies, enhances the quality of an geographical argument (Budke et al., Citation2015, p. 276).

Table 1. Argumentation evaluation scheme suitable for geographic argumentations (author’s own diagram)

In the context of geographical conflicts, not only factual arguments but also normative arguments, which refer to personal values and norms, are relevant. We therefore also took into account the students’ own logical conclusions, which we could evaluate as valid based on our criteria mentioned above. For example, students stated that the bridge would also mean independence, especially for young people. Such normative justifications were also awarded 1 point, as were factual justifications. Ideally, these justifications were then supported with factual figures, e.g. data on current ferry times. gives an exemplary overview of our analysis and assessment of student statements.

Table 2. Illustrated analysis and assessment of arguments (author’s own diagram)

4. Findings

4.1. Students’ argumentation skills on complex geographical conflicts

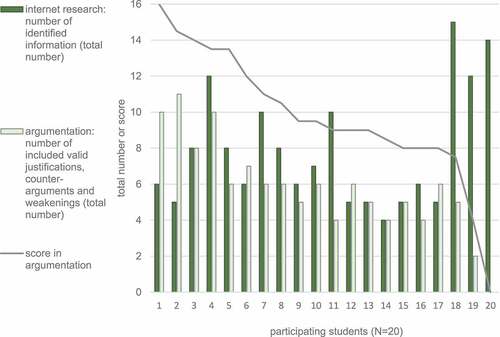

The 20 participating students found between 4 and 15 relevant, useful pieces of information on the geographical conflict during their Internet searches (cf. ). With this amount of information all participating students had collected a good set of pre-conditions for writing an argumentation on the conflict (Engelen & Budke, Citation2020). One of the participating students did not present his/her own opinion with a reasoned judgment at all and therefore achieved 0 points in the argumentation task. As we do not believe this student to have no argumentation skills but rather he/she had methodological problems (such as not reading the assignment carefully), the following evaluation of the students argumentation skills focusses on the students who developed an argumentation (N = 19). We found no connection between the questioned independent variables, such as age, gender, school, mark in geography class, or students’ Internet use, and their success in finding relevant information while searching the internet or in the argumentation task. Analysis of the transcripts revealed that all students who developed an argument on the conflict (N = 19) understood the issue they were dealing with. They were able to form an opinion on the conflict and used at least two valid justifications to support their own opinion. Thus, basic skills in argument formation have been present in all participating students, however, the students’ argumentation skills vary greatly amongst the participants.

As shown in , the students used between 2 and 6 valid justifications to support their own opinion, with an average of 3.5. They introduced between 2 and 7 different perspectives in their valid arguments with an average of 3.6. These results show that all participants were able to justify their opinion with valid reasons, and they understood that there are different interests involved in the conflict. The perspectives that were mostly included in the arguments were costs and financing of the bridge (introduced in 17 out of 19 argumentations), the effect of a bridge for local residents (in 12 out of 19 argumentations), and environmental protection and nature conservation (in 11 out of 19 argumentations). Whilst 7 out of 19 students included the advantages of a bridge for school children and commuters, only 2 students included the perspective of young people and their leisure time behaviour in their argumentation. This shows that only a few students have worked with empathy and the adoption of the perspective of peers in their argumentation. The fact that the students included up to 7 different perspectives in their valid arguments has shown that internet information searches can lead to a multi-perspective understanding of a geographical conflict. 17 out of the 19 students included at least one valid counter-argument in their reasoning, with one student introducing 5 counter-arguments. 14 students also used at least one valid rebuttal to weaken their counter-arguments. There was only one student who rebutted a counter-argument by questioning the condition under which it applies (cf. , statement 7). Although probably intuitive, this is a good technique for disproving counter-arguments and should be encouraged, particularly the inclusions of spatial conditions of an argument, as it strongly improves the quality of the geographic argumentation. It was predominantly the top-performers who included spatial references in their argumentation, who consequently provided a higher quality geographic argumentation.

4.2. Difficulties students faced in developing valid arguments

presents the average argumentation pattern of the students who developed an argumentation (N = 19). On average, around three quarters of the students’ justifications were evaluated to be accurate, relevant and valid. 25% of the justifications had to be nullified, because the students reasoned with conclusions that are very unlikely to occur (26%), such as the argument that a bridge at this location would promote tourism in the region. This can be considered as unlikely, as the scenic appeal and the campsite there would probably rather lose attractiveness due to a bridge. Mostly however, justifications had to be nullified because the students did not link their justifications comprehensible to their claim (74%), as shown in the following student quote:

Figure 4. Average student argumentation pattern used to justify their opinion (N = 19) (author’s own diagram)

“Personally, I think the bridge should be built. […] also, there are already bridges in Dömitz and Lauenburg which help people there a lot”. Simply because bridges in other places are helpful, does not justify a bridge between Darchau and Neu-Darchau. The spatial conditions in the towns of Dömitz and Lauenburg might be different to our place of interest, there might have been no ferry in operation prior to bridge development, or there may be different natural characteristics or financial capacities.

The vast majority (80%) of the students’ counter-arguments were validated, as we evaluated them to be accurate, relevant and valid. All of the counter-arguments that were nullified were considered as invalid because there was no comprehensive connection between the counter-arguments and student’s own opinion. However, it was different for students’ rebuttals of counter-arguments: 21% of the students’ rebuttals of counter-arguments were assessed as inaccurate, usually because the students were trying to weaken the counter-arguments with unproven assumptions, as shown in the following student statement:

“[…] although the costs involved are very high, […] at EUR 60–75 million they are within an acceptable range”. After a 45 minute internet search in which the student has found no information of the financial capacities of the region, we cannot call this statement a validated weakening of a counter-argument, but rather an unproven assumption.

4.3. Connection between the students’ success in their argumentations and their prior Internet search

Based on the analysis and assessment of the student arguments, we were particularly interested to find out the extent to which students’ success in their digital information search influenced their reasoning on the conflict. We expected that students who perform well in their digital information search and find a high range of useful information on the conflict would also be able to justify their opinion soundly. However, the analysis of the amount of information found by the students and the number of justifications, counter-arguments and rebuttals in their subsequent argumentation indicated a slightly negative correlation (r = −0.33). As shown in , the participants who developed arguments and presented their own opinion with a reasoned judgment achieved between 4 and 16 points, with an average of 10.3 points. The student who performed best in the argumentation development found 6 pieces of information on the conflict during his/her Internet search. On the contrary, the three students who had found the highest amount of information during their Internet search, between 12 and 15 pieces, included only a few of these aspects in their arguments, and tended to write comparably weak or even no argumentations. The lack of correlation may also be due to the fact that all students found enough information on the conflict to enable them to justify their opinion with reasoning. Since the participants had no previous knowledge on the topic the students could not have developed a good argument on the conflict if they had found very little or no information at all. As this is an exploratory study, this negative correlation cannot be considered representative, but refers exclusively to our study group. Nevertheless, this result points to a deficiency, which will be discussed further in the discussion chapter.

Figure 5. Connection between the students’ scores in their argumentations, their inclusion of valid justifications, counter-arguments and weakening in their argumentations and their number of relevant, valid pieces of information identified while searching the Internet (author’s own diagram)

Interestingly, the two students who gained the highest score in their argumentation included more validated justifications, counter-arguments and rebuttals of counter-arguments in their argumentation than information they found on the conflict during their Internet search. Those two students had the ability to use the information found to create more arguments, by using different techniques such as empathy, logical thinking, and linking information from different sources, as shown in the following examples:

Student 1 read about the ferry timetable and used empathy to explain what that means for different actors: “[…] because the ferry only runs until 9:00 in the evening […] and when it stops running in the evening [this] is also [annoying] for young people when they want to meet other people and go home in the evening. The student further linked facts and connected information found from different sources, which enabled him to weaken a counter-argument: “It would be advantageous for companies if a bridge were to exist, as accessibility and also competitiveness would be increased. The high costs are a problem […] but they are also investing in this bridge and this will possibly strengthen the economy”. Student 2 read about the negative impact of the bridge on the environment. He used his general knowledge to weaken this argument: “It is to be expected that there will be more traffic because of the bridge, but ferries also pollute the environment” (student 2).

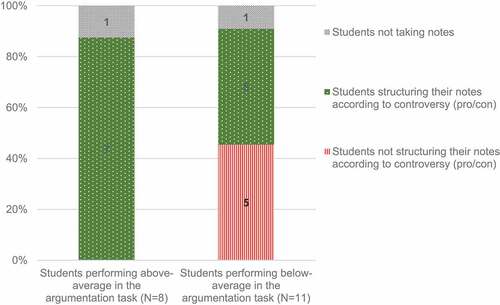

It seemed that students who organised their notes during their information search in pro and con arguments performed better in the argumentation task than students who made unstructured notes. As shown in , we categorised the 19 students into the ones who achieved 10.3 or more points in their argumentation and can therefore be classified as performing above-average within this group (N = 8 students), and the ones who achieved less than 10.3 points and are therefore classified as below-average performers within this group (N = 11). In both groups all but one student took notes while searching the Internet. All the above-average performers, who took notes, structured their notes into pros and cons, whereas in the group of below-average performers only half of them did so. This indicates that taking structured notes helps to develop a sound argumentation. Some of the participating students who had collected a lot of information during the internet search did not structure their notes and presumably thus failed to turn all the information they found into arguments.

5. Conclusion and discussion

Our study investigated (I) the extent to which students are able to develop their own reasoned judgment on complex geographical conflicts following searching the Internet for information and (II) the extent to which students’ success in finding useful information during their Internet search influences the quality of their arguments. The results, which can serve as a starting point for further quantitative research, are summarised and discussed as follows:

All of the participating students who developed an argumentation were able to successfully use their independent Internet search to form their own opinion about the conflict. The analysis of the student argumentations showed that the participants understood the conflict they were dealing with and they justified their own opinion on the topic with arguments including at least two different perspectives. The vast majority of the students included counter-arguments in their reasoning. Nonetheless, there were large differences in the quality of the students’ argumentations: 20–25% of all arguments were not evaluated as valid or accurate, mostly because students did not connect their justifications or counter-arguments logically with their own opinion, or because they used unproven assumptions when trying to rebut counter-arguments. Spatial references were missing in almost all argumentations of the below-average performers, whereas 7 out of 8 of the above-average performers included spatial references in their arguments, thus showing the ability to enhance the quality of their geographic arguments.

We assume that the results of this study can be explained by the experiences that the students have had in their previous school years. Writing arguments on geographical conflicts on the basis of Internet information searches were probably little done or reflected upon. Therefore, the study results can be relevant for teaching. Previous research has shown that argumentation skills can be fostered through practice (Driver, Newton, & Osborne, Citation2000) and explicit instruction, enabling students to transfer their newly acquired skills to different topics and show higher number of justifications and more complex argumentation structures (Zohar & Nemet, Citation2002). Connecting justifications and the student’s opinion in a meaningful and comprehensible way for the reader and thereby creating valid arguments may be practised, for example, through scaffolded peer feedback, supporting students in checking each other’s arguments for accuracy, relevance and validity. Peer feedback has shown to positively influence the quality of student argumentations on geographical topics (Morawski & Budke, Citation2019, p. 12).

Weakening counter-arguments may be practices by questioning the conditions under which they apply and thereby avoiding unproven assumptions. In contrast to what some students may think, arguments are rarely absolute and questioning the conditions, i.e. when, where and to whom the argument applies, is a good technique to rebut counter-arguments (Budke et al., Citation2015, p. 276). Furthermore, the analysis of maps for argumentative purposes and use of spatial reference in the argumentation needs to be fostered, as well as recognition of temporal developments of a conflict. Teaching material with structuring and formulation aids would help to create map-based argumentations (Budke, Kuckuck, Michalak, & Müller, Citation2016).

II. Our results did not show that the students’ success in finding useful information during their Internet search was connected to their success in developing a reasoned judgment on the conflict. A few students who found a very high amount of useful information during their Internet search performed poorly in the argumentation task. However, all participating students found sufficient pieces of information on the conflict during their Internet search to understand the conflict, which is the basic prerequisite for being able to develop an argumentation on an unknown topic. The students were able to use the information they found to include arguments from different perspectives and interest groups in their reasoning, with an average of 3.6 different perspectives included in their validated arguments. It is questionable as to whether such results would also have been achieved with traditional media, such as worksheets or German geography textbooks, which lack multi-perspective material (Budke, Citation2011, p. 261).

In an earlier study, in which university students were asked to write an argumentation on a socio-scientific issue with the help of four defined, scientific internet sources, it was shown that elaborate online sourcing enhances the justification of the claim and increases the integration of sources into the argumentation (Barzilai et al., Citation2015). We could not confirm these results in our study, which, however, included an open internet search conducted by secondary school students. Difficulties the students experienced were that many of them did not include all of the information they found on the Internet in their argument and based their reasoning on only a few pieces of identified information. More than half of the students incorporated less arguments in their reasoning than relevant information they found during their Internet search. This shows that finding information and processing this information in an argument are two different competencies that both need to be fostered. Just because students actually know arguments about a matter, does not mean that they necessarily use them in their argumentation. Students need to understand that the information they have found on the Internet is valuable for argument development and, if correct and credible, should be included in their reasoning. The students are thought to lack methodological skills to integrate evidence into the argumentation. Intervention studies have shown that instruction, which focuses on evidence-based argumentation and the enhancement of meta-level awareness, promotes the use of evidence in argumentation (Iordanou & Constantinou, Citation2014, Citation2015).

It seems that it is not the amount of identified information but the manner in which the students took their notes that influenced their argumentation; notes that were structured into pro and con arguments seemed to have resulted in better argument development. Previous studies have also identified links between the organisation of information and the subsequent argumentation. Structured organisation of information has been found to have positive effects on the integration of arguments and counter-arguments in reasonings on controversial topics (Nussbaum, Citation2008) and it also has found to have a beneficial impact on the multi-perspectivity of arguments (Uesaka, Igarashi, & Suetsugu, Citation2016). Thus, one focus of argumentation support would have to be the structuring of the information found on the Internet. Unlike the educational materials found in textbooks, which usually offer only few perspectives on a conflict and are designed to be manageable for students, the Internet offers a wealth of information for a variety of readers. Developing an argumentation with this large amount of information requires a structured processing of the information and the ability to link the different aspects to a conclusive argumentation. Some participating students probably lacked the methodological and structural knowledge of how to use the available information to form a reasoned opinion.

We are currently in the process of using our findings to develop a framework for students that will help them structure their digitally-acquired geographical knowledge and improve the quality of the subsequent argumentation. To develop this, we use the findings from the analysis of the students’ internet information searches and their simultaneous thinking aloud (Engelen & Budke, Citation2020). Among other things, it was found that students find more information on the Internet when they use different types of websites, e.g. newspapers, online representations of cities or private websites such as those of initiatives of citizens than when only using one type of website. At the same time, students need to pay more attention to the date and origin of the information. This can be done, for example, through targeted training and with the help of material-based Internet searches in which the students have to record the found information systematically. The students must be offered a framework in which they can collect the conflict-relevant multi-perspective information, the results of the digital map analysis, and the temporal developments of the conflict in a structured way.

The subsequent argumentation can be supported, for example, by linguistic or structural aids. There are already support systems that help students in the processing of information acquired during Internet searches (cf. Scholl et al., Citation2008; Zhang & Quintana, Citation2012), however, they lack the special requirements for researching complex geographical conflicts and the development of a subsequent argumentation. Also, there are frameworks for the elaboration of student argumentations on geographical issues (cf. Felzmann, Citation2012; Kuckuck, Citation2012; Kulick, Citation2012), but these are based on predetermined sources, e.g. in the form of worksheets or textbooks, and must therefore be extended to meet the challenges of independent Internet information searches on geographical problems.

This study does not claim to show representative results for the whole of Germany. It is an explorative study and is intended to generate initial findings with regard to the research questions. It provides initial insights into the ability of secondary school students to develop argumentations for geographical conflicts after searching information on the Internet. Our results may be useful for geography lesson task structure but need to be validated by larger groups of participants. Further studies on the topic should also be carried out to find out the extent to which the results differ with the age of students.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eva Engelen

Eva Engelen is a secondary school teacher of geography and English. She currently works as a research assistant for geography education at the University of Cologne. Her research focuses on internet searches and argumentation on geographical conflicts.

Alexandra Budke

Alexandra Budke is a professor of geography education at the University of Cologne. Her research interests include political education, argumentation, intercultural learning and the use of digital media in geography teaching. In her habilitation, she dealt with ideological education in geography lessons in the GDR.

Notes

1. The study task has been translated from German into English. The original German task was:Eine Elbbrücke in Neu-Darchau: Fluch oder Segen?Lange schon wird über eine Elbbrücke zwischen den Orten Neu-Darchau und Darchau diskutiert. Die beiden Orte werden derzeit über eine Fähre miteinander verbunden und es gibt unterschiedliche Meinungen und Argumente, ob der Bau einer Brücke realisiert werden sollte.Aufgabenstellung: Sollte zwischen Darchau und Neu-Darchau eine Elbbrücke gebaut werden? Begründe deine Meinung, indem du Vor- und Nachteile der Elbüberquerung abwägst.

References

- Barzilai, S., Tzadok, E., & Eshet-Alkalai, Y. (2015). Sourcing while reading divergent expert accounts: Pathways from views of knowing to written argumentation. Instructional Science, 43(6), 737–766.

- Budke, A. (2011). Förderung von Argumentationskompetenzen in aktuellen Geographieschulbüchern. In E. Matthes & C. Heinze (Eds.), Aufgaben im Schulbuch (pp. 253–263). Klinkhardt. Bad Heilbrunn.

- Budke, A. (2012). Argumentationen im Geographieunterricht. Geographie Und Ihre Didaktik, 40, 23–34.

- Budke, A., Creyaufmüller, A., Kuckuck, M., Meyer, M., Schäbitz, F., Schlüter, K., & Weiss, G. (2015). Argumentationsrezeptionskompetenzen im Vergleich der Fächer Geographie, Biologie und Mathematik. In A. Budke, M. Kuckuck, M. Meyer, F. Schäbitz, K. Schlüter, & G. Weiss (Eds.), Fachlich argumentieren lernen: Didaktische Forschungen zur Argumentation in den Unterrichtsfächern (pp. 273–297). Waxmann. Münster.

- Budke, A., & Kuckuck, M. (2017). Argumentation mit Karten. In H. Jahnke, A. Schlottmann, & M. Dickel (Eds.), Räume visualisieren (pp. 91–104). .Geographiedidaktische Forschungen Bd. 62. Münster

- Budke, A., Kuckuck, M., Michalak, M., & Müller, B. (2016). Erstellung kartenbasierter Argumentationen—Strukturierungs- und Formulierungshilfen. Praxis Geographie, 6, 46–48.

- Budke, A., Kuckuck, M., & Schäbitz, F. (2015). Argumentationsbewertungsbögen und Lautes Denken-Erhebung der geographischen Argumentationsrezeptionskompetenzen von SchülerInnen. In A. Budke & M. Kuckuck (Eds.), Geographiedidaktische Forschungsmethoden. Praxis Neue Kulturgeographie (Vol. 10, pp. 368–387). LIT. Münster

- Budke, A., & Maier, V. (2018). Wie planen Schüler/innen? Die Bedeutung der Argumentation bei der Lösung von räumlichen Planungsaufgaben. GW-Unterricht, 1, 16–29.

- Budke, A., & Meyer, M. (2015). Fachlich argumentieren lernen – Die Bedeutung der Argumentation in den unterschiedlichen Schulfächern. In A. Budke, M. Kuckuck, M. Meyer, F. Schäbitz, K. Schlüter, & G. Weiss (Eds.), Fachlich argumentieren lernen: Didaktische Forschungen zur Argumentation in den Unterrichtsfächern (pp. 9–28). Waxmann. Münster

- Budke, A., & Müller, B. (2015). Nutzungskonflikte am Rhein als komplexe Mensch-Umwelt-Systeme mit Hilfe von Argumentation erschließen. In I. Gryl, A. Schlottmann, & D. Kanwischer (Eds.), Mensch, Umwelt, System: Theoretische Grundlagen und praktische Beispiele für den Geographieunterricht (pp. 177–189). LIT. Berlin

- Budke, A., & Uhlenwinkel, A. (2011). Argumentieren im Geographieunterricht -Theoretische Grundlagen und unterrichtspraktische Umsetzungen. In H. Roderich, G. Stöber, & C. Meyer (Eds.), Geographische Bildung. Kompetenzen in der didaktischer Forschung und Schulpraxis (pp. 114–129). Westermann. Braunschweig

- DGFG, D. G. für G. (Ed.). (2014). Educational Standards in Geography for the Intermediate School Certificate—With sample assignments. Retrieved from https://vgdh.geographie.de/wp-content/docs/2014/10/geography_education.pdf

- Dittrich, S. (2017). Argumentieren als Methode zur Problemlösung: Eine Unterrichtsstudie zur mündlichen Argumentation von Schülerinnen und Schülern in kooperativen Settings im Geographieunterricht. readbox unipress. Münster

- Driver, R., Newton, P., & Osborne, J. (2000). Establishing the norms of scientific argumentation in classrooms. Science Education, 84(3), 287–312.

- Eickelmann, B., Bos, W., Gerick, J., Goldhammer, F., Schaumburg, H., Schwippert, K., … & Vahrenhold, J. (2019). ICILS 2018 #Deutschland Computer- und informationsbezogene Kompetenzen von Schülerinnen und Schülern im zweiten internationalen Vergleich und Kompetenzen im Bereich Computational Thinking. Waxmann Verlag. Retrieved from https://kw.uni-paderborn.de/fileadmin/fakultaet/Institute/erziehungswissenschaft/Schulpaedagogik/ICILS_2018__Deutschland_Berichtsband.pdf

- Engelen, E., & Budke, A. (2020). Students’ approaches when researching complex geographical conflicts using the internet. Journal of Information Literacy, 14(2), 4.

- Erduran, S., Simon, S., & Osborne, J. (2004). TAPping into argumentation: Developments in the application of Toulmin’s Argument Pattern for studying science discourse. Science Education, 88(6), 915–933.

- Felzmann, D. (2012). Gedankenexperiment als Strukturierungshilfen für moralische Argumentationen. In A. Budke (Ed.), Diercke—Kommunikation und Argumentation (Vol. A 1, pp. 56–63). Westermann.Braunschweig

- Foong, -C.-C., & Daniel, E. G. S. (2010). Assessing students’ arguments made in socio-scientific contexts: The considerations of structural complexity and the depth of content knowledge. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 9, 1120–1127.

- Iordanou, K., & Constantinou, C. P. (2014). Developing pre-service teachers’ evidence-based argumentation skills on socio-scientific issues. Learning and Instruction, 34, 42–57.

- Iordanou, K., & Constantinou, C. P. (2015). Supporting use of evidence in argumentation through practice in argumentation and reflection in the context of SOCRATES learning environment: Supporting use of evidence in argumentation. Science Education, 99(2), 282–311.

- Kroksmark, T. (2015). Teachers’ subject competence in digital times. Education Inquiry, 6(1), 24013.

- Kuckuck, M. (2012). Argumente arrangieren mit der Argumentationssonne. In A. Budke & D. Felzmann (Eds.), Diercke—Kommunikation und Argumentation (Vol. A 1, pp. 110–119). Westermann. Braunschweig

- Kuckuck, M. (2014). Konflikte im Raum: Verständnis von gesellschaftlichen Diskursen durch Argumentation im Geographieunterricht. Monsenstein und Vannerdat. Münster

- Kuckuck, M. (2015). Argumentationsrezeptionskompetenzen von SchülerInnen—Bewertungskriterien im Fach Geographie. In A. Budke, M. Kuckuck, M. Meyer, F. Schäbitz, K. Schlüter, & G. Weiss (Eds.), Fachlich argumentieren lernen: Didaktische Forschungen zur Argumentation in den Unterrichtsfächern (pp. 77–88). Waxmann. Münster

- Kulick, S. (2012). Die Argumentationskette und andere Diskussionshilfen. In A. Budke (Ed.), Diercke—Kommunikation und Argumentation (Vol. A 1, pp. 19–35). Westermann. Braunschweig

- Means, M. L., & Voss, J. F. (1996). Who reasons well? Two studies of informal reasoning among children of different grade, ability, and knowledge levels. Cognition and Instruction, 14(2), 139–178.

- Metzger, M. J., Flanagin, A. J., Markov, A., Grossman, R., & Bulger, M. (2015). Believing the unbelievable: Understanding young people’s information literacy beliefs and practices in the USA. Journal of Children and Media, 9(3), 325–348.

- Ministerium für Schule und Bildung & des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen. (2019). Kernlehrplan für die Sekundarstufe I Gymnasium in Nordrhein-Westfalen. Retrieved from https://www.schulentwicklung.nrw.de/lehrplaene/lehrplan/200/g9_ek_klp_%203408_2019_06_23.pdf

- Morawski, M., & Budke, A. (2019). How digital and oral peer feedback improves high school students’ written argumentation—A case study exploring the effectiveness of peer feedback in geography. Education Sciences, 9(3), 178.

- Müller, B. (2016). Komplexe Mensch-Umwelt-Systeme im Geographieunterricht mit Hilfe von Argumentationen erschliessen: Am Beispiel der Trinkwasserproblematik in Guadalajara (Mexiko). Köln

- Nussbaum, E. M. (2008). Using argumentation vee diagrams (AVDs) for promoting argument-counterargument integration in reflective writing. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(3), 549–565.

- Oßenbrügge, J. (2001). Konflikt. In E. Brunotte, H. Gebhardt, M. Meurer, P. Meusburger, & J. Nipper (Eds.), Spektrum—Lexikon der Geographie. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag. Retrieved from https://www.spektrum.de/lexikon/geographie/konflikt/4277

- Purcell, K., Rainie, L., Heaps, A., Buchanan, J., Friedrich, L., Jacklin, A., … Zickuhr, K. (2012). How teens do research in the digital world (Pew Research Center, Ed.). Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2012/11/01/how-teens-do-research-in-the-digital-world/

- Scholl, P., Benz, B., Böhnstedt, D., Rensing, C., Steinmetz, R., & Schmitz, B. (2008). Einsatz und Evaluation eines Zielmanagement-Werkzeugs bei der selbstregulierten Internet-Recherche. In S. Seehusen, U. Lucke, & S. Fischer (Eds.), DeLFI 2008: Die 6. E-Learning Fachtagung Informatik der Gesellschaft für Informatik e.V.; 07. - 10. September 2008 in Lübeck, Germany (pp. 125–136). Ges. für Informatik. DeLFI. Bonn

- Stanford History Education Group (Ed.). (2016). Evaluating information: The cornerstone of civic online reasoning. executive summary. Retrieved from https://purl.stanford.edu/fv751yt5934

- Tebaartz, P. C., & Lengnink, K. (2015). Was heißt „mathematischer Beweis“? – Realisierungen in Schülerdokumenten. In A. Budke, M. Kuckuck, M. Meyer, F. Schäbitz, K. Schlüter, & G. Weiss (Eds.), Fachlich argumentieren lernen: Didaktische Forschungen zur Argumentation in den Unterrichtsfächern (pp. 105–120). Waxmann. Münster

- Toulmin, S. (2003). The uses of argument (Updated ed.). Cambridge University Press. Cambridge

- Uesaka, Y., Igarashi, M., & Suetsugu, R. (2016). Promoting multi-perspective integration as a 21st century skill: The effects of instructional methods encouraging students’ spontaneous use of tables for organizing information. In M. Jamnik, Y. Uesaka, & S. Elzer Schwartz (Eds.), Diagrammatic representation and inference (Vol. 9781, pp. 172–186). Springer International Publishing. Cham

- Uhlenwinkel, A. (2015). Geographisches Wissen und geographische Argumentation. In A. Budke, M. Kuckuck, M. Meyer, F. Schäbitz, K. Schlüter, & G. Weiss (Eds.), Fachlich argumentieren lernen: Didaktische Forschungen zur Argumentation in den Unterrichtsfächern (pp. 46–61). Waxmann. Münster

- Walhout, J., Oomen, P., Jarodzka, H., & Brand-Gruwel, S. (2017). Effects of task complexity on online search behavior of adolescents. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 68(6), 1449–1461.

- Zhang, M., & Quintana, C. (2012). Scaffolding strategies for supporting middle school students’ online inquiry processes. Computers & Education, 58(1), 181–196.

- Zohar, A., & Nemet, F. (2002). Fostering students’ knowledge and argumentation skills through dilemmas in human genetics. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 39(1), 35–62.