ABSTRACT

The past and current situation in Greece regarding the refugee crisis has created educators’ need to apply new educational strategies to address refugee students, such as the use of translanguaging, linguistic landscape and schoolscape as pedagogical tools. That is why the present study attempts to reveal the degree of educators’ employment of practices such as translanguaging and inclusion of students’ L1 in the creation of linguistic signs and how they are reflected in the schoolscape. Based on photographs and interviews gathered by eleven educators in formal and non-formal education in Greek schools, we decoded translanguaging and sign-making practices by identifying a taxonomy of different functions represented by the signs, the initiative of teachers as primary sign-makers, and the promotion of teaching Greek as L2. The study suggests that incorporating students’ and teachers’ translingual signs and multimodal practices in learning procedures paves a promising way to designing a competent curriculum for teaching language diversity and encouraging intercultural awareness.

1. Introduction

Since the 1980s, Greece has witnessed the arrival of a fast-growing number of immigrants and refugees from Africa, Eastern Europe and the Middle East (IOM in Greece, Citation2020). In 2015, , it is estimated that 856,723 refugees arrived in Greece. The presence of many diversified immigrant communities who settle in urban and rural spaces of Greece and import their linguistic and cultural diversity considerably affects the linguistic situation of the country. At a time when the globalised expansion of information, cultural exchange and high speed communication influence the constant change of language dynamics in form and structure, immigrant flows add a crucial factor of plurilingualism to the already variegated Greek linguistic reality (Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2008).

In recent years, the linguistic landscape (LL) has offered new rich theoretical insights in the fields of bilingualism and multilingual education. According to García (Citation2009), multilingual education refers to the use of more than one language during teaching. Multilingual education is far from being considered a new concept. At least in Europe, it has a long tradition, and even during the Roman Empire there were several multilingual academies (Franceschini, Citation2013). Today’s society is super-multilingual, and since one of the main aims of schools is to prepare students for this plurilingual reality, LL as an educational tool can play a crucial role (Shohamy, Citation2006). Certainly, constant changes in language boundaries and migration patterns affect the language heterogeneity of the school-aged population as well, concluding with most children today speaking different languages at home than the ‘standard’ language taught at school (García, Citation2008). This fact brings language educators and policymakers increasing challenges and the need to seek new approaches and patterns in the language teaching area (Darquennes, Citation2013; García, Citation2008; Lu & Horner, Citation2013). Many scholars are closely involved in the development of innovative pedagogic activities and projects, using the LL and publicly visible signs for language teaching and learning in various educational contexts (see Chern & Dooley, Citation2014; Dressler, Citation2015; Gorter & Cenoz, Citation2015; Hancock, Citation2012; Rowland, Citation2013; Sayer, Citation2010; Szabó, Citation2015). At the same time, other researchers, such as Gorter (Citation2006) and Shohamy and Gorter (Citation2009), have focused their attention on the study of the schoolscape as a particular field of LL.

Signs are at the teachers’ disposal to exploit them for language teaching; nevertheless, little research has been done on educators’ awareness of the use of linguistic signs as a multilingual and second language acquisition weapon in their pedagogical arsenal, or on the ways they can achieve language enforcement through the schoolscape. With its multidimensional forms and the spontaneity in its use, translanguaging can constitute one of these valuable techniques employed by language teachers. It is not the first time that the LL research has turned attention to the fields of translanguaging and multilingualism (Gorter, Citation2017; Gorter & Cenoz, Citation2015; Van Mensel, Vandenbroucke, & Blackwood, Citation2016). Multilinguals daily use all their linguistic resources, and often either unconsciously or deliberately mix them to communicate, renegotiate ideas, and construct meanings and identities (Canagarajah, Citation2011; Cenoz, Citation2012). This innate use of communicative strategy by multilingual people was named translanguaging by García (Citation2008). Apart from its great and granted linguistic and communicative aspect, translanguaging is also considered valuable in education (Gogonas & Maligkoudi, Citation2019). More specifically, Jessner (Citation2006) claims that multilingual students have the advantage of accessing the languages they already know in order to bridge the languages with their metalinguistic awareness and subsequently to enforce students’ learning strategies for new languages. This asset can be used through code-switching, translation and other translanguaging practices projected and used in translingual signs in the schoolscape during the teaching process. Language educators can and must build on their students’ linguistic repertoires by using multimodal and translingual pedagogical practices to boost the students’ ability to learn the target language.

The pedagogical value of the schoolscape from the educators’ point of view and the use of translingual signs as a teaching tool able to promote language learning in school programmes are the cardinal points of this research. In the study, we present the concept of the translingual schoolscape, combining the fundamental terms of translanguaging and schoolscape through a sociocultural view on language teaching. Throughout the article, “translingual” spaces refers to spaces where language practices are associated with arguments defending the language practices and rights of those deemed linguistically “other” (Lu & Horner, Citation2013). The research is based on eleven (11) interviews with teachers about their awareness of their refugee students’ needs and the use of signs as a pedagogical tool.

2. Theoretical background

2.1. Translingual schoolscape as an educational tool

Translanguaging can not only be seen in individuals’ small multilingual parts but can also be developed in interactive multilingual social contexts, such as the linguistic landscape of a public building or of a whole neighbourhood (Gorter & Cenoz, Citation2015). Translanguaging in its written form has become a popular topic in LL research (Van Mensel et al., Citation2016). The linguistic landscape was first launched and defined as a notion by Landry and Bourhis in 1997. The term refers to all the linguistic signs and multimodal texts which are displayed in a specific public territory (Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2008; Hewitt-Bradshaw, Citation2014; Landry & Bourhis, Citation1997). Cenoz and Gorter (Citation2008) consider the term “multilingual cityscape” (p. 268) more accurate, while Mondada (Citation2000) creates a metaphor of cities as texts (Dagenais, Moore, Sabatier, Lamarre, & Armand, Citation2009). The concept of power in the linguistic landscape has been strongly emphasised by Huebner (Citation2006), who argues that linguistic tokens serve to delineate the geographical and social boundaries of neighbourhoods, and to the extent that linguistic tokens are artefacts of a central government, they may reflect the overt language policies of a given state. In this sense, they are markers of status and power. Recently, Alomoush (Citation2021) explored linguistic creativity and innovation in multilingual advertising in Jordan through the use of signs displaying Arabinglish in multiple forms in the Jordanian linguistic landscape, while Coluzzi (Citation2020) examined the multilingual and “multiscriptal” linguistic landscape in Malaysia, the significance of Jawi in the area, and its mainly symbolic use in the linguistic landscape.

The field of LL study has been connected with research in various domains of inquiry, such as applied linguistics and sociolinguistics, but has only recently started to expand its scope in the field of education. Education is a field that can contribute to specific research, adding many interesting themes of LL application in language teaching and learning through interaction, especially when more than one language is involved. This may be due to the fact that signs on streets, which are written in the same languages as the languages taught at school, are available to schoolchildren’s sight and constitute a familiar reading source (Gorter & Cenoz, Citation2007, Citation2015). More specifically, Dagenais et al. (Citation2009) explored the issue of the development of multilingualism and language diversity awareness and negotiation of the identity of elementary students through mono/bi/multilingual sign-recording by schoolchildren themselves in the LL close to their schools and the use of signs as a pedagogical material in activities. Cenoz and Gorter, in their 2004 study, supported the hypothesis of the potential influence of LL in L2 learners’ language use and perspectives on languages. Hancock (Citation2012) studied student teachers’ understanding of LL and explored the usefulness of LL as an educational method and stimulus for student teachers’ multilingual awareness. García (Citation2008) pointed out that proactive educators include multimodal linguistic messages in their lessons, such as photos, images, art and music, found and taken from the LLs outside the school or from the internet, and are able to influence learners’ way of using language.

Students who practise reading and improving their fluency in the target language and abilities in other languages think consciously, critically and creatively about languages from a social, political and linguistic perspective. They examine different purposes, meanings, authors and audiences of signs, they build attitudes and appreciation towards linguistic diversity and they develop cultural, symbolic and pragmatic competence through contact with and analysis of texts with various cultural origins and social services. They also develop complex literacy and communicative skills in a foreign language or L2 and they acquire new language learning strategies by “reading” the world holistically (Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2008; Chern & Dooley, Citation2014; Clemente, Andrade, & Martins, Citation2012; Dagenais et al., Citation2009; Gorter, Citation2017; Gorter & Cenoz, Citation2015; Hancock, Citation2012; Hewitt-Bradshaw, Citation2014; Malinowski, Citation2009; Rowland, Citation2013; Sayer, Citation2010). The use of an innovative multimodal media for contacting and learning a language, such as the “photo safari” of signs in real world situations outside school classrooms, seems more interesting, meaningful and engaging than traditional lecture-type teaching methods, and consequently can excite curiosity and influence students’ motivation for language learning (Cenoz, Citation2012; Hancock, Citation2012; Hewitt-Bradshaw, Citation2014). Students additionally have the opportunity to interact verbally and informally with L1 and L2 users in their communities. In general, as Dagenais et al. (Citation2009) argued, the introduction of LL in schools can “reveal the dynamic interaction between children’s language and territory” (p. 266). While students try to interpret their local and global LL, they simultaneously build understanding of the world and their position as world citizens (Clemente et al., Citation2012). Furthermore, it is worth mentioning that Hancock (Citation2012) uses LL as an awareness-raising tool for students and teachers preparing for the latter-day reality of multilingual educational settings.

2.2. Sign-making practices in schools

In this study, the focus of language use in schools will be on the written form, and especially on the signs that constitute part of the schoolscape and how the material and visual resources can be used for instruction purposes. The notion of the schoolscape was introduced by Brown (Citation2012) in her study on the signs inside schools to determine the degree of revitalisation of the Võru language in the south-eastern part of Estonia. She defined the schoolscape as “the school-based environment where place and text, both written (graphic) and oral, constitute, reproduce, and transform language ideologies” (Brown, Citation2012, p. 282). The schoolscape corresponds to the school materials and modes, like figures, texts, pictures, artefacts and sounds, which are perceptible and can be located in the entrance, the foyer, classrooms, on the walls and in the corridors of schools. Szabó (Citation2015) extends the term by using it to describe pictorial elements, images and inscriptions, as well as the spatial placement of furniture in educational places. Prior (Citation2009) describes signs in schools as symbols that constitute part of the environmental print (Dressler, Citation2015), and Jakonen (Citation2018) as a resource for social interaction during instruction. The characteristics of schoolscapes are distinct from those of LL in public spaces. Gorter (Citation2017) uses differentiated lists according to the number of languages depicted on the signs and the authorship.

The main notions intertwined with schoolscape are visual literacy and multimodal discourse. Language alone is not able to carry all the meanings: it needs other modes – semiotic, visual, oral – in order to co-build understanding for a communicative situation. Multimodality is not just a choice but is more “the ‘fullness’ of meanings” synthesised by the dynamic contribution of each mode (Kress & van Leeuwen, Citation2020, p. xv). In multimodal literacy, the text is perceived as a physical object occupying space, being placed in a context and often accompanied by images (Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2008). This means that visual communicative acts and products can be read as texts raising values and meanings (Laihonen & Szabó, Citation2017). Scollon and Scollon (Citation2003, pp. 769–770) refer in a similar way to “visual semiotics” as the interactive contact with signs, and to “geosemiotics” as the study of emerged or interrupted identities in the material deployment of languages. Another idea that is a significant principle for the current research is what Scollon and Scollon (Citation2004) presented as a threefold nexus of sign-making decisions and practices in schools. The nexus comprises the “historical body” that refers to the teachers, students and other school actors as sign-makers, their practices over time, the possibility to create signs, the process and the result in the particular school environments; the “interaction order” that is related to the time, place and order of sign creation proceeded from the reciprocal affiliations, interference and hierarchy between the social actors in school contexts; and the “discourses in place” that designate the rationale behind the choice of sign made and the languages included (Dressler, Citation2015; Scollon & Scollon, Citation2004). Szabó (Citation2015) mentioned that laws and institutional regulations mainly for public educational settings determine and sometimes restrain the visual practices that are sanctioned to be implemented (Szabó, Citation2015). However, the linguistic choices and symbols displayed on schools’ walls and the façades of both formal and informal educational settings reveal quite extensively the linguistic, social and cultural orientation of each institution (Brown, Citation2012). Thus, the schoolscape can represent school ideologies towards monolingualism, multilingualism, foreign languages, local or immigrant minority languages.

Teachers create or intervene in the creation of linguistic signs in order to create input for their students. Rowland (Citation2013) contends that the visual and educational materialisation of schoolscapes is greatly beneficial for the language learning process, while Jewitt (Citation2008) highlights the significance of the teachers’ design decisions on a range of representational pedagogic materials available to the students in the classroom and how these decisions can shape various paths of knowledge. Furthermore, Landry and Bourhis (Citation1997) claim that the quality and frequency of contact with LL are strongly connected with students’ ability to learn and use languages. In particular, since the classroom is a model of the outside world on a small scale where the students get exposed to the dominant language in written form, the creation of linguistic signs displayed in the classroom supplements the “commercial environmental print” with which language learners are already acquainted (Giles & Tunks, Citation2010, p. 25). In this way, teachers use different practices reflected in the schoolscape to make the language noticeable to students and promote their early literacy competence in L2, regardless of their L1, by providing learners with reading opportunities through visual exposure to language input and written examples for copying (Dressler, Citation2015; Reyes & Azuara, Citation2008). But when the signs include more than one language, the environmental print also serves as a push towards bilingualism and biliteracy, and a tool for raising language diversity awareness and giving prominence to positive depictions of different languages, dialects and their speakers (Dagenais et al., Citation2009; Dressler, Citation2015; Huebner, Citation2006). Certainly, distinct combinations of languages included in the same sign can range from linguistically very distant to typologically closer languages in terms of alphabet, literacy features, lexicon, syntax, pragmatics, phonology and stylistic complexity (Cenoz & Gorter, Citation2015). Visual exposure to bilingual texts provides opportunities to connect the unknown language with the familiar writing system, leading students to comprehend more deeply the nature of their native language and making them more competent in making sense of the target language, since students’ L1s always influence the learning of new languages. Even the observation of repetition in the grammar of the printed texts can potentially be effective as a practice for better language learning and stimulation of internal alterations in the minds of learners. Hewitt-Bradshaw (Citation2014) contends that bilingual signs can potentially support learners whose mother tongues are not visible, heard and valued in schools. It can also constitute an instructional means more meaningful for students’ needs, experiences and backgrounds, enabling students’ willingness to learn and use both L1 and L2. Moreover, resources found and reflected in the schoolscape, like other approaches and classroom interactions, can be a pedagogical teaching tool not only for codes but also for skills. Schoolscape enforces students’ visual socialisation – in other words, their ability to decipher the visual symbols and signs, to engage more easily in visual communication in school while reading, interpreting and critically questioning what they see, and to face their literacy in a more complex and holistic way (Clemente et al., Citation2012; Laihonen & Szabó, Citation2017). The schoolscape also contributes to the identity construction of a place and, as a result, to the impending reflection of the spatial identity on the students’ linguistic use, identity and behaviour, which are under development (Clemente et al., Citation2012; Landry & Bourhis, Citation1997).

In this research, we analyse the characteristics of different sign-making practices and their use as a pedagogical tool in language classrooms. These characteristics are based on the focal educators’ views and the use of signs in their classrooms in Greek educational settings where refugee students can be found. Additionally, the research examines the involvement and the role of human actors in the school community in the process of moulding the schoolscape.

3. The methodology of the research

3.1. Research sample

This research emphasises the exploration of schoolscapes in various formal and non-formal educational settings in several parts of Greece, both on the mainland and on Islands, where refugees stay and attend schools. Eleven educators talked about their experiences and gave examples of sign-making practices employed in their multilingual classes in their current and former job environments. The focal educators worked either in formal education (public elementary and secondary schools) or in informal education (NGOs) in several cities and Islands of Greece (i.e. Chios and Samos, Serres, Thessaloniki). The educational and working profiles of the participants are presented in .

Table 1. Participants’ profiles.

3.2. Procedures, research materials and method of analysis

On the strength of qualitative interviews, data on the translinguistic schoolscape were collected with reference to educators’ language awareness of their students’ needs and the pedagogical value of activities based on the linguistic signs. Research data were collected through interviews and through photographs of signs in several school environments.

All interviews with the eleven teachers were conducted over distance by means of virtual communication tools or phone due to the pandemic COVID-19 restrictions on free movement and face-to-face meetings. The interviews were recorded for research purposes, after notifying and asking the permission of the participants, who were informed that the recordings would not be accessible by others and would be deleted after completion of the study. For ethical reasons and to preserve anonymity, personal information, such as names and appellations, were altered in the transcriptions. The teachers and other agents, students and education consultants are referred to in the research using pseudonyms so as not to be identifiable during the presentation of the data.

The interview questions refer notably to the research questions and what Scollon and Scollon (Citation2004) indicate as “historical body, interaction order and discourses in place” (p. 13). More precisely, we asked the interviewees for instances of creative and pedagogical use of their students’ languages as captured on linguistic signs and the degree of use of different resources in the schoolscape as a language learning tool. In order to introduce the educators to this topic, we asked them if they had digital photos of examples of such signs from their classrooms which they would like to share with the researchers. In case they had no photos, either because they had not created such signs in the past or they had never captured them, we showed them a representative sample of signs, asking them questions about the possible functionality and contribution of such material in the lessons. Only two educators did not have photos of signs to share; while many of them did not have instances of all their sign-making activities, they shared one or two and described orally the rest of their actions and ideas. Their classrooms were the central points for data description and collection.

The material collected for the purposes of our research analysis were almost three hours of recorded interviews transcribed and translated from Greek to English, and a total of 110 photographs of monolingual, bilingual or multilingual signs visible in schoolscapes. We substantially grounded our research in qualitative data analysis, and specifically, in nexus analysis and linguistic landscape analysis (Dressler, Citation2015; Scollon & Scollon, Citation2003). Linguistic landscape analysis is based on visual analysis of photos with the view to interpret the nature of the linguistic signs and classify them. So, we portrayed in words the set of information and recognised the patterns among them while extracting data by the photos, the audio recordings, and the interview transcripts. We analysed the photos based on their categories and identified some themes regarding the type of sign, its use and functionality differentiated between top-down and bottom-up, the languages appeared on the sign, the authors, and the location where it is posted.

Ιn addition to recording learners’ personal reactions towards linguistic and cultural stimuli, signs in the schoolscape can have different uses and purposes, and sometimes particular languages may be used for separate functions. Landry and Bourhis (Citation1997) made a broader distinction between symbolic and informative functions of signs. Later, Gorter and Cenoz (Citation2015) referred to nine functions: the instruction of language and content; the classroom handling and the school administration, which are based on the informative intentions of sign-making; the promotion of values, intercultural awareness and minority languages, which represent the symbolic functionality; and lastly, the notice of events or of information as publicity and the decorative purposes, which have both informative and symbolic use. This classification of functions is also implemented in the present paper. Furthermore, nexus analysis gives access to the researchers to explore the social practice, thus we tried to convey the main actors’ relationships, decisions and actions regarding LL and their beliefs concerning the use of schoolscape as a tool for promoting language learning.

The main research question is how educators use the signs found in the schoolscape as a pedagogical tool for multilingual or L2 promotion and what they perceive to be the main characteristics of the linguistic signs (instances, functions, authorship, distribution of languages). All in all, this research aims to contribute to the field of schoolscape and translanguaging by casting more light on how educators can employ language awareness activities to support and strengthen their refugee students’ L2 (multi) literacies.

4. Uses and functions of translingual schoolscape

Nine of the eleven participants in the interviews described the sign-making techniques that they apply in their classrooms and school settings in general and talked about the benefits that students receive from the signs in their teaching process. All of them insisted on adding images to signs as one of the most important educational and motivational materials. This mindset is greatly consistent with several scholars’ research results, such as Hewitt-Bradshaw (Citation2014), who concluded that high use of images in language teaching creates a more motivational and appealing learning environment for L2 students. In fact, some of the focal educators favoured the use of pictorial more than linguistic modes on signs, whereas others considered that text and image bear equal weight in the teaching process. As Cenoz and Gorter (Citation2008) affirmed, the educational and teaching power of LL evolves from the complex textual designs – for instance, the combination of one or more languages with visual cues. However, nine teachers presented and explained more educational purposes that arise from the use of sign-making practices, such as helping their refugee students to feel more familiar with the classroom, school and learning environment; prompting their students to share their diversity; applying peer-to-peer teaching; and facilitating the teaching procedure.

During the research, we collected over 110 instances of language and multilingual signs in schoolscapes. The picture data were analysed in order to define the different uses and functions that the signs embody, the authorship of the signs, the number of languages (non-verbal, monolingual, bilingual or multilingual signs), and the languages used on the signs. Most of the signs were the result of the educational processes inside the classrooms, but there are also instances outside the school, in the main entrance, the foyer, the corridors and on doors. The photos were all taken in a refugee camp in Northern Greece.

Several scholars have provided categories of visual and linguistic signs in multilingual areas and educational settings, like Dagenais et al. (Citation2009) and Dressler (Citation2015), but to define and distinguish the different communicative intentions of the signal texts in our research, we follow as a guide Gorter and Cenoz’s (Citation2015) research on the schoolscape in multilingual schools in the Basque country and their own classification of nine different functions of the school signage. Their categorisation is a finer distinction than the research on which they are broadly based, namely Landry and Bourhis (Citation1997) differentiation between informative and symbolic functions of signs. The analysis of the signs from ten schoolscapes of Greek formal and non-formal institutions where refugee students can be found reveals eight different uses of the texts on translingual signs, according to our study. These functions are the following: (1) language teaching; (2) classroom and school management; (3) teaching values; (4) raising intercultural awareness; (5) decoration; (6) raising awareness about hygiene rules and measures against COVID-19; (7) announcements regarding educational activities of the involved organisation; and (8) announcements regarding non-educational services for the beneficiary population.

4.1. Language teaching

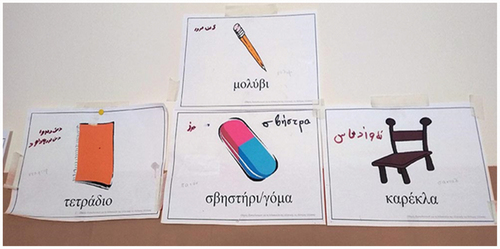

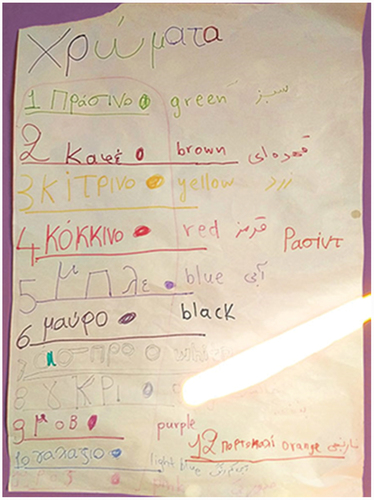

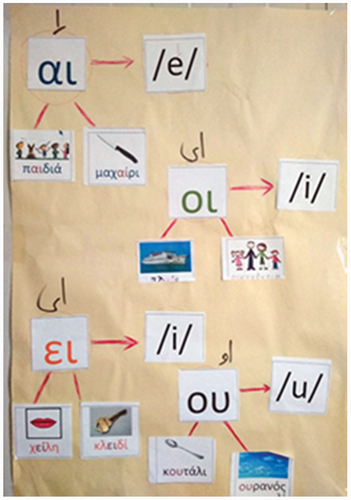

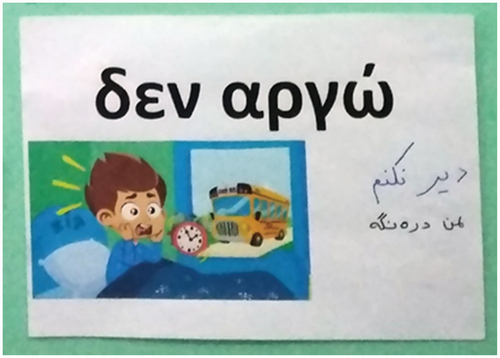

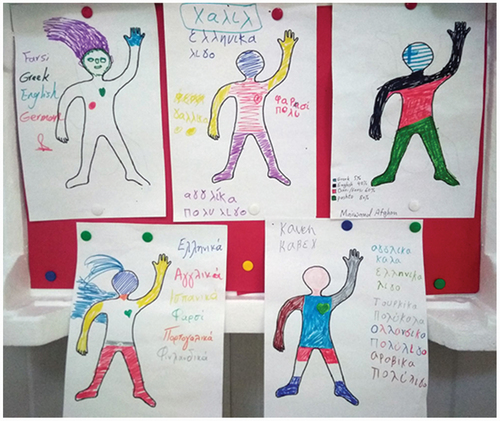

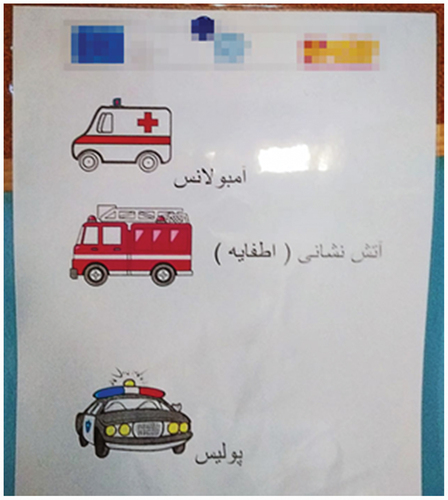

One of the most common reasons for using signs from the schoolscape as part of a lesson plan is teaching new vocabulary. For instance, three of the focal teachers had on display on their classroom walls pictorial-linguistic signs with the most common school objects. Educator 7 referred to them as “vocabulary teaching tools and reminders”. All the focal teachers advocated that the inclusion of pictures in these signs is necessary as they attract children’s attention. Educator 7 observed that “Many times, when they [the students] want to remember a word in Greek, their eye directly goes to the picture that they know is somewhere in the classroom and try to read and tell me, in case they have forgotten the word” (E7). Educator 1 agreed, arguing that along with students’ gestures towards the sign and the word “this”, referring to the image, the signs were a very helpful point of reference when teaching and a tool for making communication easier and more direct. Educator 1 also mentioned that she tried to learn the school objects in her students’ L1s, and she depicted them in written form on linguistic signs combined with the related image posted on the classroom walls (). It seems that the initiative of creating and writing the Greek word in all of the instances related to school objects was the teacher’s. Educator 10 claimed that, in general, “the existence of such signs, boards all around us in the classrooms, reinforces the learning process” (E10). Another multilingual sign for teaching vocabulary, and particularly colours, was shared by Educator 10 (). The sign seems to have been made by the students and includes one more first language in addition to Greek and English. For Educator 10, sign-making seems to be an almost daily practice. Her signs tend to be multilingual, pictorial and colourful, and her goal is for the students to learn and understand Greek better and more joyfully, as well as to share their linguistic repertoires.

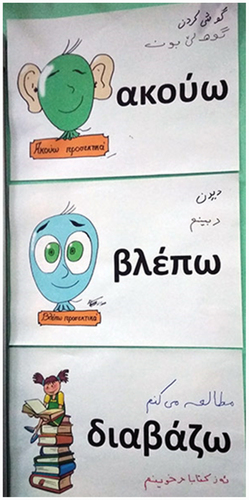

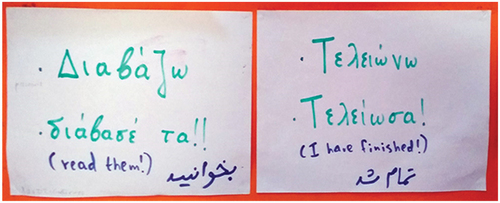

The sign-making practice can have a different but very conscious functionality in the teaching process (). For example, the teacher sometimes chooses to create a sign with the children at the end of a lesson for assessment reasons. She also mentions that in every class “we always do something so that children can take it home, a paper, a cardboard, a mini card, a leaflet, a notebook that can be opened and seen. We have created many ideas like that and they also make something to keep it at home as a souvenir or to hang it on their own wall” (E10). Greek verbs such as “I read”, “I write”, “I speak”, “I ask”, etc. are another subject in which Educators 1 and 5 use multilingual signs as a teaching means. The verbs are mainly those used more often during the lesson, and the signs are hung on around the whiteboard. Therefore, these signs could also operate as aids in classroom management. Educator 1 explains the process that she followed for the creation of the signs (): “I was painting or printing an object, which I wanted to study in all languages. I also had Romany students in the class. So we wrote the word in Greek, English, Farsi, Arabic and Romany language, and also how they are pronounced, as it is written in the dictionaries, so that they could all be included in the sign”. She adds “I did just the drawing or the print and then the children wrote in their language the name of the object or the situation, because we also learned the verbs. Then I wrote how it is pronounced in English characters” (E1). Photo 4 is the result of Educator 5’s initiative and the cooperation between her and the students. The signs are trilingual. Greek and English are written by the teacher, whereas “My teenage students wrote these words in Farsi because I have the best level of communication with them” (E5). The Greek texts not only include the verb in the simple present tense but also the imperative form, advancing the signs as possible teaching aids for grammar.

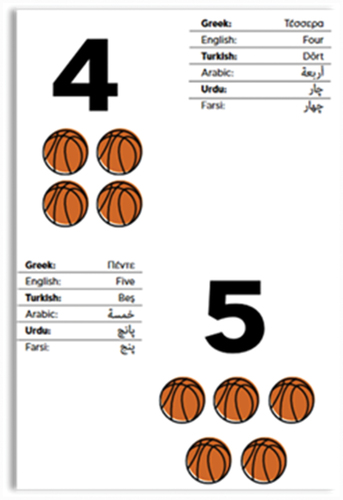

According to Educator 3, multilingual signs can also be used for teaching and facilitating students’ understanding of spelling: “I only have one sign from the educational part and many times I think it also helps in spelling” (E3). She explains that “It helps a lot in basic expressions, such as the word ‘είναι’, because it has the ‘αι’ which is alpha iota and is read /e/ again” (E3). The students wrote the information in their L1 while the teacher wrote below the translation in Greek and the pronunciation of the Greek with an English script so that the students could read and learn the Greek spelling easier. In general, Educator 1 highlighted the usefulness of translation in the teaching and learning process for refugee students. The educator also added the pronunciation of all words, even those in students’ mother languages, in English characters, so it was easier for her to read them, despite the fact that capturing the students’ L1 pronunciation was often a demanding task (“I wrote the pronunciation of the word in English characters. Now, of course, the allophones that the children have in their languages, the strange letters sounding as /kh/ or /q/, that we do not have in Greek, I could not capture them but we tried!” E1) (). On the other hand, numeracy is the main teaching target for Educator 9, who is a mathematician. The teacher puts on the classroom walls multilingual and pictorial signs with numbers. The specific signs are ready-made and include numbers and their names in Greek, English, Turkish, Arabic, Urdu and Farsi. However, the teacher says “there are also signs in the classrooms which are in their own language, or in ours with their own letters, always with the help of interpreters. So that they understand that we call a specific form a ‘triangle’ and read it in their own language. Because this is just as important as knowing the word ‘mutheleth’, which is the Arabic word for triangle. It is just as important to know how we say it, so they can read it in their own language to make the transition” (E9) ().

It seems that teachers used signs as educational material to teach new vocabulary, grammar, spelling, the Greek alphabet and numeracy. They also used signs during the teaching process as a tool for evaluation, consolidation of knowledge, or revision of material already taught.

4.2. Classroom and school management

Three educators and the coordinator, all working in a refugee camp in Northern Greece, referred to the use of signs to inform their students about the behavioural rules in the classroom and the school. In particular, Educator 6 presented a sign about the rules of the classroom and more general behavioural reminders that she created collaboratively with her teenage students ( and ). The sign answers to the functions of classroom management and teaching values, since it contains linguistic and moral messages about being responsible for the educational material and the school spaces or being on time for class, respecting each other and being kind. The sign includes English as an intermediate communication code and the students’ L1s, Farsi and Kurdish. Greek is not included despite the fact that the educator says “Greek was written by me and all the other children. We had one who knew English. He wrote English. I helped him a little with the spelling and everything else. Because I have no idea, they wrote it in Farsi and Kurdish without any help from me. The rules that we included were the result of group discussion. Writing was shared” (E6).

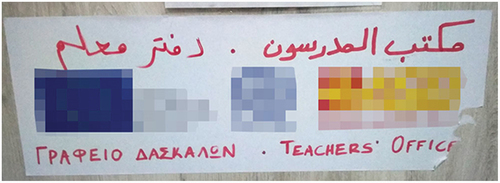

The signs that concern school management are mostly signs for orientation, naming the school spaces and classroom functions, mainly to inform possible visitors and the new student population. In a non-formal educational setting in a refugee camp in Northern Greece we found , which is a multilingual sign written in Greek, English, Farsi and Arabic. Educator 11 says about this: “The main poster is a sticker with the logo of the organization for promotion purposes. It is a triple logo including the organization that runs the programme in the camp, but also the other partner organizations, which are the sponsors. A text was written on it as a sign and hung on the door of the teachers’ office inside the school. At the initiative of teachers and interpreters, we noted this in other languages so that it can be easily communicated to students” (E11).

Consequently, educators have created and used some of these signs to remind students about the agreed behavioural rules in the classroom, facilitating some communicative habits and guidance for the classroom routine or appointing a student to a role.

4.3. Teaching values

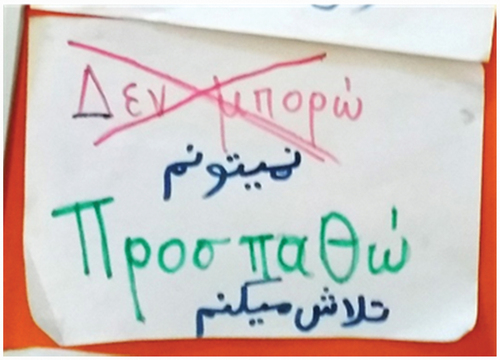

There are also signs on the classroom walls that have messages about values and functions as constant reminders for the students to help each other and to try harder. and , shared by Educators 1 and 5, are made following the same process as their examples depicting verbs and other prompts. These signs, of course, not only carry a symbolic meaning, but can also be used as teaching materials.

4.4. Raising intercultural awareness

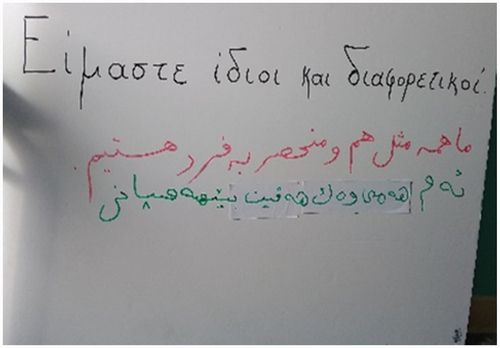

The educational settings which refugee students attend are multilingual and multicultural, since refugee populations come to Greece from various places around the world. It seems that most educators consider this diversity and do their utmost to promote it and remind the children of it through relevant projects and the creation of plenty of multilingual signs that raise intercultural awareness among them. These kinds of signs often generate discussions about linguistic and cultural diversity among students (Hancock, Citation2012) and enable a broad variation of voices to be heard in the classroom (Pietikäinen & Pitkänen-Huhta, Citation2013). For instance, Educator 1 used signs as a method for intercultural education. She gave learners the opportunity to show and express their customs in a creative way, such as during the Christmas period. She describes: “Of course, we also talked a lot about their customs. For example, when it was Christmas, we talked about it. They told us about the different foods they make, so we found them, printed them, hung them and transformed the Christmas period as close to their own environment as possible” (E1). Another sign creation by Educator 1 derived from an idea she had and implemented in her general elementary class in which both refugee and Greek-speaking students participated. During the first days of the schooling year, she devoted time to create the “corner of the language” in her classroom, where Greek, Arabic and Farsi alphabets were displayed with multiple benefits for all students. In this way, refugee students found an opportunity to share their linguistic identities and could feel included in the classroom: simultaneously, Greek students who may not be familiar with diversity came into contact with totally new linguistic codes.

Another striking example of promoting cultural and individual diversity among students is the creation of identity texts. Educator 5, for instance, encouraged her students to use their native languages both orally and in writing. She asked her new students to present themselves through an image and a message in any linguistic choice in which they felt comfortable expressing themselves: “So, one activity, in addition to communicative ones, is that we always make identity texts in the early stages. I invite students to present themselves through an image and by using any linguistic choice they wish” (). Other instances derive from discussion with Educator 11 and the implementation of a project related to the World Day for Human Rights by teachers at the school in the refugee camp in Northern Greece. There is a great amount of material from the project displayed in the school corridors. The message on one of them () represents educators’ effort to contribute to greater comprehension among their students of the beauty of diversity and, simultaneously, that differences are not a limiting factor when it comes to equal rights.

4.5. Decoration

Decoration by hanging signs in the school mostly has an aesthetic purpose. Decorative signs are usually drawings and personal creations made by students, such as photographs, artefacts and multilingual cards produced during recreational activities and projects implemented in classrooms by students, mainly with the support of the educators. was found decorating the corridors of the school in the camp in Northern Greece. Educator 11, who is partly responsible for the sign-making and posting in communal school places – the corridors, the foyer, the entrance, etc. – mentions, “We often post educational material on the walls of the school. These are children’s creations in arts and crafts, paintings, in the context of a project. Here specifically the students made their identity: based on the right that everyone has a name, an identity, each student created a picture of himself, who he is, etc. It was the beginning of the project in essence that introduced the students to rights. One of them is the name and identity of everyone” (E11). Furthermore, Educator 8 sometimes uses drawing time as an opportunity for learning. She argues, “it can be a creative activity wherein students have drawn something, give a title in their mother tongue and write the name of the word also in Greek, for example” (E8, ).

4.6. Raising awareness of hygiene rules and measures against COVID-19

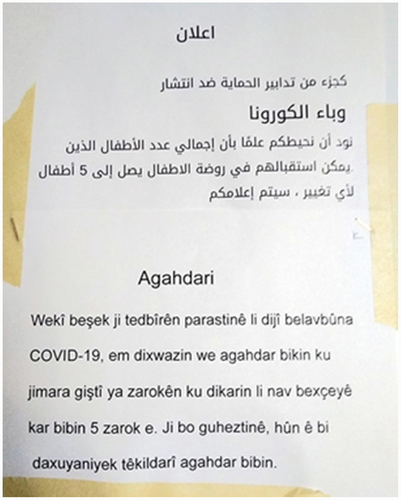

Hygiene rules and protection against the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic is a current subject not only in schools but in all people’s activities all over the world. Two of the educators in the refugee camp mentioned the existence of related signs in their classrooms and in general in common school spaces. More specifically, Educator 5 referred to them as ready-made signs which are related to the COVID-19 pandemic and means of precaution, and they are burdened with a lot of text. She claims that “The COVIDs are ready-made ones by external parties. They pay more attention to the signs produced during lessons, made collaboratively, compared to a ready-made sign. Especially if the ready-made one is burdened with many language elements, the student is not the recipient of the message and all they look at are the graphs” (E5). According to the level of linguistic proficiency, students more often need simple language signs with few words and phrases and not monolingual signs, written only in the English language. Educator 7 and her students resort to translanguaging between Greek, English and Farsi for communication purposes. She says that she uses this technique for signs about hygiene rules, as well. However, the ready-made signs about hygiene habits in her classroom that she shared seem to be monolingual in one of the children’s languages (). One more example related to information about viral diseases was found and captured at the entrance to the school building (). The sign was produced by the governmental administration team of the camp. It is written in two of the native languages of the population living in the camp.

4.7. Announcements regarding educational activities of the involved organisation

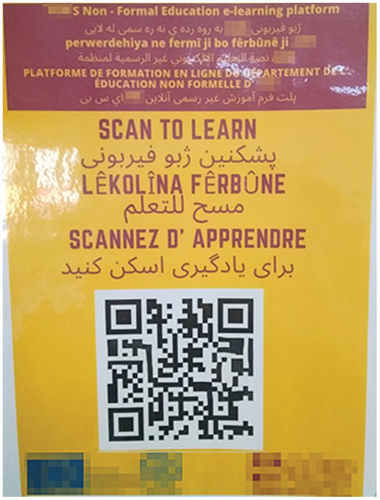

Several signs are related to announcements about educational activities in the school, like the students’ weekly timetable or information about the creation of an educational site in the context of the particular organisation operating in the camp. Educator 11 refers to these: “But there are mainly announcements regarding our activities – for example, the weekly time schedule, either the individual one for each group of students or an aggregate programme for all teachers. […] While a specific poster this year concerns the creation of an educational site, created by the organization, where, in essence, educational material created by the teachers of the non-formal education team is posted”. The poster is multilingual including English, French and several students’ L1s ().

4.8. Anouncements related to other services for beneficiaries

Educator 11 described a range of functions of the signs displayed on the walls of the school spaces. The last function that he distinguished concerned useful announcements about issues regarding services other than education for the beneficiary population: these signs were mainly displayed in the entrance. They are notifications giving up-to-date information about actions and services such as recycling, suggestions and emergency services, organised or provided by the organisation involved in the camp, the administrators or other partners and organisations. Educator 11 mentioned that “Many announcements come from above, from those who are at a senior administrative level in the organization. Usually, these announcements concern material that must be announced to the whole population and concern mostly services that the organization can provide. So, these announcements are prepared from above or may come from another organization – i.e. a partner in the camp or the sponsor”. He added that many of the signs were accompanied by corresponding images. Additionally, most of the time there was an attempt to translate the signs into the majority of students’ home languages ( and ).

5. The schoolscapes in numbers

The documentation of schoolscapes and sign-making practices in educational settings which refugee students attend in Greece, took place taking into account the nexus analysis from Scollon and Scollon (Citation2004, p. 13), including the functions and the distribution of languages, the authorship, the location of the signs, the associations and the relations of power between the sign-makers. The analysis reveals that the majority of the signs are created and located in the classrooms. Simultaneously, there is a preference towards multilingual texts containing the target language, Greek, along with one or more of the students’ linguistic repertoires, and a strong reliance upon the teachers’ initiative for the production of linguistic signage.

More specifically, a total of 62 linguistic signs or groups of associated signs were photographed. The research indicated that 40 were found in classrooms (65%) and 22 (35%) in common areas, on doors, the entrance, the foyer, corridors and the teachers’ office. One third of the total signs, namely – the majority – operated as teaching tools for the focal teachers. The functions of linguistic texts that were mostly found in classrooms were the development of intercultural awareness and classroom management, raising hygiene awareness and teaching values. Conversely, the signs which were displayed in common areas of the school operated mainly as announcements for educational activities implemented by teachers and other actors of the focal organisation, decoration, developing intercultural and hygiene rules awareness, announcements about non-educational activities by the focal educators and other actors, and lastly, classroom and school management.

We also found that of the 62 signs and groups of signs, the vast majority – 46 signs (74%) – were the result of focal teachers’ initiative, 14 signs (23%) were produced by external actors and authorities, and only two (3%) were a result of children’s own work and choice. All 22 signs used as teaching aids in the classroom were made at focal teachers’ volition: 13 were a result of cooperative work between educators and refugee students, and nine were exclusively produced and printed by the teachers. Students had also participated with their teachers in the creation of signs on classroom management, teaching values, developing intercultural awareness and decoration, but there were few indications of signs exclusively generated by refugee students. The two signs that the focal teachers identified as willing creations by the students themselves were used as decoration.

According to Dressler (Citation2015, p. 132) “the social actors who create signs within the school are numerous and are influenced by many discourses”. The linguistic elements and messages on the signs can be distinguished according to their authors in top-down and bottom-up signs, borrowing the terms from congruous research in the LL field. Top-down signs are created, used and displayed under the control of concrete authoritative policies, generally following an inclination towards dominant rules, whereas bottom-up signs are designed and utilised more freely by individuals according to their deliberate preferences and strategies (Ben-Rafael, Shohamy, Amara, & Trumper-Hecht, Citation2006). Educational administrators and external authoritative actors can be considered to be included in the top-down category, whereas teachers and their groups of students align with the bottom-up initiative to make and exhibit signs. However, all different actors simultaneously give shape to the schoolscapes despite the fact that the writers’ intentional meaning can remain incomprehensible and thus hidden to the readers of the signs (Malinowski, Citation2009). Specifically, in our research, 45 of the 62 signs (73%) were bottom-up and the other 17 (27%) were top-down signs. Despite the variety of actors who added signs in the schoolscape, the interviewers’ focus group indicated that the teachers themselves were predominantly responsible for the sign-making and posting practices in schools. The educators hang top-down signs on their classroom walls only when they receive them from external actors of the organisation, such as in the case of the hygiene rules and awareness. Unfortunately, the lack of students’ initiative confirms Szabó’s (Citation2015) research that students are dependent on their educators’ actions and decisions, as reflected in the focal teachers’ discourses during the research. Even in non-formal educational settings, some teaching practices remain subtly authoritative. Additionally, top-down signs to a great extent concern announcements, self-identification of the organisation and school activities: thus, they are placed strategically in the school entrance and the foyer.

In this vein, we found that of the 62 captured instances, 43 signs (69%) included at least one of the students’ native languages, while 19 signs did not contain any L1 (31%). It is distinctive that equal proportions of bottom-up and top-down signs include and promote students’ mother languages. All kinds of announcements, hygiene promotion and school management trying to achieve instant communication and guidance include messages in the population’s L1s, as Educator 11 says: “And certainly, one goal, which I think we achieve most of the time, although it is a bit time consuming sometimes, is the translation into the basic languages, always based on the needs and the availability of the respective staff in the organization. For example, there is currently no interpreter who can support written translation into Kurmanji and other Kurdish dialects, so we usually do not do this. Usually in terms of the students’ languages, we do translation into Farsi and Arabic” (E11). This rationale accords with teachers’ instructional practices in that they try to communicate more easily; on the other hand, they wish to make their students feel more comfortable and accepted despite their linguistic and cultural diversity, as the focus group of teachers confirms. It seems that the preferred translingual strategy employed by the focal educators for this purpose is translation. Additionally, the dialogical interviews motivated two of the educators to reflect critically upon their monolinguistic choices. Even their feeling of not being confident in their students’ linguistic repertoires superseded by thinking that the students themselves can write down the respective translation in their mother tongues under the Greek text (“The sign is written in Greek. But verbally, we also use the words in Farsi. I don’t have it written in two languages for technical reasons. Or rather, in this particular case it wasn’t technical: it was easy to find the words in Farsi. I just didn’t think about it” E5). Educator 7 says, “For example, in my class I have on the walls some icons only in Greek, that soon will be written below in their languages as well, with the very common school objects like book, pencil, eraser, notebook, chair, desk”. Besides, as Szabó (Citation2015) argued, it is not possible for multilingual and heterogeneous protagonists to be addressed in a monolingual and monocultural way.

6. Conclusion

The movement restrictions due to the spread of the pandemic and the subsequent lockdowns constrained the researchers’ chances of visiting other educational settings and asking permission to capture instances of the schoolscapes. We were only able to gather the research material by distance through the opportunities that technology offers for relevant actions, and by visiting just one non-formal school setting in Northern Greece, where six of the interviewees were working. The start of the COVID-19 pandemic in February 2020 and the subsequent lockdowns that closed the schools and hit all levels of education constituted a fundamental hindrance not only for the researchers but also for all the students and teachers, and continues to do so. As Educator 4 said, “the lockdown hit us after March and stopped us” (E4). Teachers, mainly from formal education, who did not have access to the school settings during the research, forwarded to us only those photos that they had taken before the start of the pandemic.

Examination of the schoolscapes revealed that in our study educators were the primary sign producers, while the majority of the captured instances included the target language, Greek, as well as students’ mother tongues, and they were created and exhibited in the classrooms as teaching language aids. The schoolscape is a web of human actors who use languages in different ways to achieve different communicative aims through the texts on their signs (Gorter & Cenoz, Citation2015). This research attempted to contribute to the perception of the unique characteristics of the schoolscape and its functionality in the pedagogies for refugee and migrant students. Some of the pedagogical and other messages, which are reflected through eight functions of signs, are the teaching of values and different aspects of language, the growth of intercultural and hygiene awareness, and reminders of behavioural rules and lesson routines. Signs also operated as decoration, using materials produced during projects and recreational activities, or provided information about the function of school spaces, about educational activities and procedures, and about other services that address the beneficiary population.

One of the goals of this research was to explore the human actors in the school community and the degree of their participation in the construction of the schoolscape. The majority of the signs were the result of teachers’ initiative, while the few that signs had been created by school and external authorities, administration or other organisations and were basically related to promotion, practical guidance, announcements of different types, and protection measures against the spread of the pandemic. The students usually contributed by adding a written translation of the text in their mother tongue. However, it seems that the students have the opportunity to be, if not in the centre, at least members of the classroom interaction routine. They feel free to articulate their own ideas in classrooms that are, in our study, exclusive to the refugee population and not general education classes. By observing and interpreting the sign-making processes, the researchers could be considered as additional agents (Szabó, Citation2015).

The classrooms seem to be safe spaces where various languages, including both Greek and students’ linguistic repertoires, are welcome (Wei, Citation2011). They are expressed either orally – for example, by repeating the new vocabulary in many languages to be comprehensible by all – or in writing, as translingual instances of signs tacked to the classroom walls reveal. The methods of translanguaging and language signs capture and optimise the plurilingual activity of students. The learners seem to show their educators how they can acquire better knowledge, and the inclusion of mother tongues plays a leading role in this process, as García (Citation2009) indicated. The focal language educators, either spontaneously or by being aware of their students’ abilities and needs, build on learners’ already acquired linguistic resources and capture the L1s in their multimodal, translingual, and schoolscape instructional practices to boost students’ linguistic competence in the new language, as Canagarajah (Citation2011) showed. This is noticeable in the high percentage of educational signs for language learning inside the classrooms. The language learning signage promotes recognition, responsiveness and keenness on the part of students and surpasses in number the schoolscape signs of other functionality, such as signs to develop values or classroom management, though these are not excluded as possible learning triggers.

Despite the fact that English has a central role in teaching as an intermediate and universal communication language, the study indicates that the protagonists in sign-making practices are the Greek language and the students’ native tongues. Inclusion of L1s in the lesson and the visual landscape of the classroom has multiple benefits for the students. As Canagarajah (Citation2011) claimed, students value the significance of the languages that pertain to their repertoires on different levels, but the greatest investment is in their home language. So, according to the analysis of the resources of the schoolscape, the focal educators seem to create and provide safe spaces for the refugee students, who are encouraged to use their native tongues, home values and identities as tools for learning and expanding their repertoires in the classrooms through both the linguistic signs on the walls and the educators’ attempts to use their students’ languages (Straszer, Rosén, & Wedin, Citation2020). Teachers seem to promote their students’ translanguaging practices and involve their L1s in audible and visible forms in the lesson. The degree of inclusion or exclusion of the students’ L1s in the tuition does not seem to be conditioned by the educational backgrounds and primary subjects of the focal teachers, but manifests as an unpredictability, determined sometimes by individual educator’s ideas or the availability of interpreters. The aspect on which all focal participants agree is the high importance not only of linguistic but of visual elements to the signs displayed on the walls. The images as teaching aids, always combined with oral, written and gestural short and repetitive discourses, seem to have a noteworthy placement in the instructional process and are considered ideal for teaching language beginners, motivating and provoking open discussion and understanding.Footnote1,Footnote2

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Margarita Karafylli

Margarita Karafylli is an Educator of Modern Greek as L2 in NGOs.

Christina Maligkoudi

Christina Maligkoudi is Assistant Professor at the Department of Primary Education at the Democritus University of Thrace and a Tutor at the Hellenic Open University.

Notes

1. Photographs taken by the researchers in the camp of Northern Greece are the following: 4 (classroom), 7 (classroom), 8 (classroom), 9 (teachers’ office), 11 (classroom), 12 (classroom), 13 (school corridor), 14 (school corridor), 15 (classroom), 16 (classroom), 17 (foyer), 18 (foyer), 19 (foyer), 20 (school main entrance).

2. Photographs that were sent via e-mail to the researchers by focal teachers were the following: 1 (ZEP classroom in Samos), 2 (classroom in another camp of Northern Greece), 3 (DYEP classroom in Chios), 5 (general education classroom in Athens), 6 (classroom in urban private setting in Thessaloniki), 10 (DYEP classroom in Chios).

References

- Alomoush, Ο. Ι. S. (2021). Arabinglish in multilingual advertising: Novel creative and innovative Arabic-English mixing practices in the Jordanian linguistic landscape. International Journal of Multilingualism, 1–20. doi:10.1080/14790718.2021.1884687

- Ben-Rafael, E., Shohamy, E., Amara, M. H., & Trumper-Hecht, N. (2006). Linguistic landscape as symbolic construction of the public space: The case of Israel. In D. Gorter (Ed.), Linguistic landscape: A new approach to multilingualism (pp. 204–221). Frankfurt: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

- Brown, K. D. (2012). The linguistic landscape of educational spaces: Language revitalization and schools in southeastern Estonia. In D. Gorter, H. F. Marten, & L. Van Mensel (Eds.), Minority languages in the linguistic landscape (pp. 281–298). Basingstroke: Palgrave-McMillan.

- Canagarajah, S. (2011). Translanguaging in the classroom: Emerging issues for research and pedagogy. In L. Wei (Ed.), Applied linguistics review 2 (pp. 1–28). Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2008). The linguistic landscape as an additional source of input in second language acquisition. IRAL, International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 46(3), 267–287.

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2015). Minority languages, state languages and English in European education. In W. E. Wright, S. Boun, & O. García (Eds.), The handbook of bilingual and multilingual education (pp. 473–483). New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Cenoz, J. (2012). Bilingual and multilingual education: Overview. In The encyclopedia of applied linguistics. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 5–12 . doi: 10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal0780

- Chern, C., & Dooley, K. (2014). Learning English by walking down the street. ELT Journal, 68(2), 113–123.

- Clemente, M., Andrade, A. I., & Martins, F. (2012). Learning to read the world, learning to look at the linguistic landscape: A primary school study. In C. Hélot, M. Barni, R. Janssens, & C. Bagna (Eds.), Linguistic landscapes, multilingualism and social change (pp. 267–285). Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

- Coluzzi, P. (2020). Jawi, an endangered orthography in the Malaysian linguistic landscape. International Journal of Multilingualism, 1–17. doi:10.1080/14790718.2020.1784178

- Dagenais, D., Moore, D., Sabatier, C., Lamarre, P., & Armand, F. (2009). Linguistic landscape and language awareness. In E. Shohamy & D. Gorter (Eds.), Linguistic landscape: Expanding the scenery (pp. 253–269). New York: Routledge.

- Darquennes, J. (2013). Multilingual education in Europe. In C. Chapelle (Ed.), Blackwell encyclopedia of applied linguistics (pp. 11–23). London: Blackwell Publishing.

- Dressler, R. (2015). Signgeist: Promoting bilingualism through the linguistic landscape of school signage. International Journal of Multilingualism, 12(1), 128–145.

- Franceschini, R. (2013). History of multilingualism. In C. Chapelle (Ed.), Blackwell encyclopedia of applied linguistics. London: Blackwell. 2526–2534.

- García, O. (2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell.

- García, O. (2008). Multilingual language awareness and teacher education. In J. Cenoz & N. H. Hornberger (Eds.), Encyclopedia of language and education (Vol. 6, 2nd ed., pp. 385–400). Berlin: Springer Science+Business Media LLC.

- Giles, R., & Tunks, K. W. (2010). Children write their world: Environmental print as a teaching tool. Dimensions of Early Childhood, 38(No3), 23–30.

- Gogonas, N., & Maligkoudi, C. (2019). Translanguaging instances in the Greek linguistic landscape in times of crisis. Journal of Applied Linguistics, 32, 66–82.

- Gorter, D., & Cenoz, J. (2015). The linguistic landscapes inside multilingual schools. In B. Spolsky, M. Tannenbaum, & O. Inbar (Eds.), Challenges for language education and policy: Making space for people (pp. 151–169). New York: Routledge Publishers.

- Gorter, D., & Cenoz, J. (2007). Knowledge about language and linguistic landscape. In N. H. Hornberger (Ed.), Encyclopedia of language and education (2nd, rev ed., pp. 1–13). Berlin: Springer Science.

- Gorter, D. (2006). Linguistic landscape: A new approach to multilingualism. Clevedon, Avon: Multilingual Matters.

- Gorter, D. (2017). Linguistic landscapes and trends in the study of schoolscapes. Linguistics and Education, 1–6. doi:10.1016/j.linged.2017.10.001

- Hancock, A. (2012). Capturing the linguistic landscape of Edinburgh: A pedagogical tool to investigate student teachers’ understandings of cultural and linguistic diversity. In C. Hélot, M. Barni, R. Janssens, & C. Bagna (Eds.), Linguistic landscapes, multilingualism and social change (pp. 249–266). Frankfurt: Peter Lang.

- Hewitt-Bradshaw, I. (2014). Linguistic landscape as a language learning and literacy resource in Caribbean creole contexts. Caribbean Curriculum, 22, 157–173.

- Huebner, T. (2006). Bangkok’s linguistic landscapes: Environmental print, code mixing, and language change. In D. Gorter (Ed.), Linguistic landscape: A new approach to multilingualism (pp. 31–51). Frankfurt: Multilingual Matters Ltd.

- IOM in Greece. (2020). Retrieved from https://www.iom.int/countries/greece

- Jakonen, T. (2018). The environment of a bilingual classroom as an interactional resource. Linguistics and Education, 44, 20–30.

- Jessner, U. (2006). Linguistic awareness in multilinguals: English as a third language. Edinburgh, Scotland: Edinburgh University Press.

- Jewitt, C. (2008). Multimodality and literacy in school classrooms. Review of Research in Education, 32(1), 241–267.

- Kress, G., & van Leeuwen, T. (2020). Reading images: The grammar of visual design. London: Routledge.

- Laihonen, P., & Szabó, T. P. (2017). Investigating visual practices in educational settings: Schoolscapes, language ideologies and organizational cultures. In M. Martin-Jones & D. Martin (Eds.), Researching multilingualism: Critical and ethnographic approaches (pp. 121–138). London: Routledge.

- Landry, R., & Bourhis, R. Y. (1997). Linguistic landscape and ethnolinguistic vitality. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 16(1), 23–49.

- Lu, M., & Horner, B. (2013). Translingual literacy, language difference and matters of agency. College English, 75(6), 586–611.

- Malinowski, D. (2009). Authorship in the linguistic landscape: A multimodal performative view. In E. Shohamy & D. Gorter (Eds.), Linguistic landscape: Expanding the scenery (pp. 107–125). New York: Routledge.

- Mondada, L. (2000). Décrire la ville. La construction des savoirs urbains dans l’interaction et dans le texte. Paris: Anthropos.

- Pietikäinen, S., & Pitkänen-Huhta, A. (2013). Multimodal literacy practices in the Indigenous Sámi classroom: Children navigating in a complex multilingual setting. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 12(4), 230–247.

- Prior, J. (2009). Environmental print: Real-world early reading. Dimensions of Early Childhood, 37, 9–14.

- Reyes, I., & Azuara, P. (2008). Emergent biliteracy in young Mexican immigrant children. Reading Research Quarterly, 43(4), 374–398.

- Rowland, L. (2013). The pedagogical benefits of a linguistic landscape project in Japan. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 16(4), 494–505.

- Sayer, P. (2010). Using the linguistic landscape as a pedagogical resource. ELT Journal, 64(2), 143–154.

- Scollon, R., & Scollon, S. W. (2003). Discourses in place. Language in the material world. London: Routledge.

- Scollon, R., & Scollon, S. W. (2004). Nexus analysis: Discourse and the emerging internet. London: Routledge.

- Shohamy, E., & Gorter, D. (2009). Linguistic landscapes. Expanding the scenery. London: Routledge.

- Shohamy, E. (2006). Language policy: Hidden agendas and new approaches. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Straszer, B., Rosén, J., & Wedin, Å. (2020). Spaces for translanguaging in mother tongue tuition. Education Inquiry, 1–19. doi:10.1080/20004508.2020.1838068

- Szabó, T. P. (2015). The management of diversity in schoolscapes: An analysis of Hungarian practices. Apples – Journal of Applied Language Studies, 9(1), 23–51. Retrieved from https://apples.journal.fi/article/view/97876/55889

- Van Mensel, L., Vandenbroucke, M., & Blackwood, R. (2016). Linguistic landscapes. In O. García, N. Flores, & M. Spotti (Eds.), Oxford handbook of language and society (pp. 423–449). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wei, L. (2011). Moment analysis and translanguaging space: Discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese youth in Britain. Journal of Pragmatics, 43(5), 1222–1235.