ABSTRACT

This discussion paper explores the development and implementation of a new flexible route into the teaching profession. This flexible route is offered within an education system in the midst of wide reform, which has partnership working between universities and schools at the centre of its Initial Teacher Education. Key elements of the new programme examined include how student teachers acquire the knowledge they need, with interconnectivity, immersive practice and blended learning of significance. This case study illustrates the importance of flexibility in the development of the student teacher’s personal construct and communities of practice. The programme’s adaptive learner-centred approach is delivering an alternative, flexible route into the teaching profession, broadening the experience base of the future teaching workforce and beginning to successfully address key government policy drivers.

Introduction

Many countries experience challenges in achieving an effective supply of knowledgeable and highly-qualified teachers (Education Workforce Council, Citation2020a; Egan, Longville, & Milton, Citation2019; Podolsky, Kini, Darling-Hammond, & Bishop, Citation2019; See & Gorard, Citation2020; UNESCO, Citation2016). A range of factors are influencing the demand for a new flexible route into teaching in Wales. These include teacher shortages, the lack of diversity within the teaching profession, and the lack of teachers with Welsh language capacity.

The educational reform underway in Wales was initially driven by disappointing PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) results in 2009, and recommendations proposed in a review of the “quality and equity” of the school system (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Citation2014, p. 12). Independent reviews of the curriculum and assessment arrangements (Donaldson, Citation2015) and Initial Teacher Education (ITE) (Furlong, Citation2015) provided further impetus for reform. The Welsh Government’s national mission for education emphasises working in partnership with the education sector to deliver reforms which include strengthening the ITE sector and professional learning (Welsh Government, Citation2017a). Consequently, a new accreditation process for ITE requires joint ownership between schools and universities for ITE, and opportunities to link school and university learning with research (Welsh Government, Citation2018a).

Teacher recruitment is reported as a “substantial challenge” for the secondary sector (11–18 year olds) in Wales. The number entering ITE has fallen below expected targets in recent years (Education Workforce Council, Citation2020a; Ghosh & Worth, Citation2020, p. 4). Welsh and bilingual schools also experience particular challenges and the rurality of some schools similarly contributes to this (Education Workforce Council, Citation2020a; Ghosh & Worth, Citation2020). Countries that are considered to have “well-developed” processes for teacher development are reported to have a full range of policy directives that focus equally on recruiting, preparing, inducting and retaining teachers (Darling-Hammond, Citation2017, p. 294). Those who train the teachers are also critical in ensuring this quality (Cochran-Smith, Grudnoff, Orland-Barak, & Smith, Citation2020). Also, education reform is believed to improve the global competitiveness of nations and teacher education policies perform a key role in this (Furlong, Citation2013). Wales is therefore striving to improve its education system by raising standards, reducing the attainment gap and “deliver an education system that is a source of national pride and confidence” (Welsh Government, Citation2017a, p. 3). Significantly improving ITE in Wales is integral to this and here a key feature of the reform – a new flexible teacher education route – is explored.

Training to teach in Wales

Typically, in Wales, student teachers train to teach via a full-time Undergraduate degree course which includes Qualified Teacher Status, studied over three years. Alternatively, if they have achieved an Undergraduate degree they need to achieve a full-time one-year PGCE. However, since September 2020 a flexible option has been available via The Open University in Wales Partnership PGCE programme. The flexibility offered by this programme means the training takes two years to complete, as opposed to one. This allows student teachers the option to work alongside their studies and/or have time for other commitments such as caring or voluntary work. The two-year PGCE is delivered via a flexible, blended learning model. The features of the blended flexible PGCE remove barriers caused by location or distance from a university that aspiring teachers may have experienced in the past (Welsh Government, Citation2019). Flexible or part-time teacher training opportunities appeal to a broad demographic of potential teachers, who bring with them varied life experiences, knowledge and attributes. Empowering existing talented individuals within Welsh education communities, such as teaching/learning support assistants, technicians and librarians, to step up to teaching, helps schools to “grow their own teachers”. Also, with new teachers encouraged to enter the profession with experiences from other workplaces and with diverse backgrounds can enrich the teaching workforce (Lester & Price, Citation2020; Williams, Citation2021).

The Open University in Wales

Another key driver in the development and delivery of the new PGCE is the extensive experience of The Open University which has delivered high-quality flexible blended learning for more than 50 years. Currently over 170,000 students study with The Open University (The Open University, Citation2021a), and more than 14,500 of these are based in Wales (The Open University, Citation2021b). The Open University has 20 years of experience in offering part-time distance teacher education across the four nations of the UK. The new flexible PGCE is taught and assessed in either Welsh or English according to the student teacher’s preference. The PGCE has been developed in partnership with school-based teacher educators and regional education consortia – there are four regional education consortia in Wales that support school improvement.

The ongoing educational reforms that are being brought into the curriculum, school leadership, professional standards and professional development in Wales provide extensive opportunities for the aspirations of the education reform to be achieved (OECD, Citation2020a; Welsh Government, Citation2017a). A workforce drawn from the very best who are trained to the highest level is integral as the benefits of the reforms will then be directly passed on to learners.

The Welsh education landscape

Although there are currently just over 35,000 registered teachers, this was just below 39,000 in 2011 (Education Workforce Council, Citation2020b, p. 9). Some subject areas have a significant number of non-specialist teachers delivering their curriculum in Wales. For example, Physics (56.2%), Chemistry (50.3%), Biology (40.9%) and Religious Education (33.8%) of teachers delivering these subjects in secondary schools in Wales trained in another subject (Education Workforce Council, Citation2020b, p. 22). The number of teachers qualifying from ITE courses in Wales has recently increased, however, this follows a declining trend over the past 10 years (Education Workforce Council, Citation2021). Even though there has been a decline in the number of student teachers training to teach in Welsh over several years, this has also very recently seen a slight increase (Welsh Government, Citation2021b, p. 5; p. 29). However, a lack of diversity within the teaching workforce and those training to teach provide further drivers for educational reform. The majority of those training to teach are aged between 21 and 24 years with 4.5% of ITE students in Wales from Black, Asian and Minority backgrounds in 2019 (Welsh Government, Citation2021a, p. 19). There is a range of possible strategies that can be deployed to attract a diverse teacher workforce (Brussino, Citation2021, p. 28). The Welsh Government (Citation2021c) plan to financially incentivise the recruitment of more ethnic minority teachers as only 3% of registered teachers identified themselves as being from non-white minority ethnic backgrounds. However, 12% of learners in schools in Wales are from minority ethnic backgrounds (Welsh Government, Citation2020a).

One of the key priorities for the Welsh Government’s vision for education in Wales between 2014 and 2020 was “an excellent professional workforce with strong pedagogy based on an understanding of what works” with important contributions expected from ITE (Welsh Government, Citation2014, p. 12). It is apparent that changes and improvements to the ITE provision in Wales have gained momentum in recent years, but these developments in ITE have not happened in isolation and are just one critical element of the wider education reform across the nation.

Training new teachers to achieve “a new kind of teacher professionalism” is the goal in Wales (Furlong, Citation2015, p. 7). Furlong also commented that as teacher education was primarily university led in Wales the sector was not well served (Furlong, Citation2015). Consequently, the educational reform underway in Wales is particularly wide ranging, as all aspects of the sector are facing change. For example, legislation such as the Additional Learning Needs (ALN) and Education Tribunal (Wales) Bill aims to provide a unified system to support all learners from 0 to 25 with ALN (Welsh Government, Citation2020b). Initiatives such as the Pupil Development Grant and a rural education action plan also contribute to demonstrating an inclusive and equal education offer (Welsh Government, Citation2020c, Citation2018b).

Throughout the ongoing educational reforms, the OECD continue to advise and support the processes and appear to have been a key influence in the Welsh education reform (Mutton & Burn, Citation2020). For example, developing schools as learning organisations in the drive to deliver the new curriculum (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Citation2018). The progress achieved to improve teaching and learning in Wales is recognised, yet it is also noted that the co-construction of policies and enhancing the use of research are critical to ensure further progress (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Citation2017). The most recent OECD review concludes that although progress in the implementation of the education reform is evident, positioning schools and communities at the centre will be crucial for the continued co-construction process to be successful (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Citation2020a). Others have also reflected on the importance of such co-construction in ITE (Cranston-Gingras et al., Citation2019). The flexible route into teaching discussed here is a strong example of co-construction and the evolving landscape of professional practice in Welsh ITE.

A new flexible route into teaching

Programme objectives

Both the new routes into teaching lead to the award of PGCE which is a qualification required for Qualified Teacher Status in Wales. The new PGCE takes two years to complete and can be studied through the medium of English or Welsh or a combination of languages. Both routes combine a distance learning programme with practice learning in schools. The salaried route is for students who are currently working in schools or those who can secure employment in a school. This route is funded by the Welsh Government. Whereas the part-time route supports students who wish to continue with work or other commitments outside school, integrating this with practical teaching experience in schools. The part-time route is funded by students; either self-funded or through a loan and grants. The Open University currently offers the PGCE Programme in Primary teaching, and in Secondary Maths, Science, Welsh, English, English with Drama, and English with Media Studies.

The salaried route

Student-teachers on the salaried route are supported by grants that are payable to the school where they work. They are employed as non-qualified teachers while they complete their academic studies (The Open University, Citation2021c). This programme is mostly aimed at those who currently work (or have experience) in an environment with children and young people. This may include teaching or learning support assistants who wish to progress their career, laboratory technicians, school librarians, or participation and youth officers.

The part-time route

Student-teachers on the part-time route are placed in schools by the Open University. Those on this route, provided that they can secure release to engage in schools during the practice learning periods, can continue to work in other jobs or meet other commitments. Across the two-year programme, students on this route complete 120 days of practice learning in schools. This can, initially, be completed flexibly, but at the end must include a 30-day block of teaching (The Open University, Citation2021c). This route is popular with those who have caring commitments, those who wish to continue working elsewhere and for career-changers.

Programme structure

The model adopted by the Open University Partnership removes the barriers of specific times and specific location from academic study and offers flexibility in terms of immersive practice-based experiences in schools. It offers flexibility through a hybrid blended open learning approach, which is learner centred. In summary the key elements of the approach include:

Online study materials (in Welsh and English) that focus on six strands moving through three levels as student teachers progress through the programme;

Online seminars (through the medium of Welsh and English) with a curriculum tutor working alongside school-based mentors/ practice tutors;

Practice learning in schools, with an assessment of practice, scaffolded by a School Experience Guide (which is linked to the tutorials and core study materials) and supported by school-based mentors, co-ordinators and practice tutors;

Assessment at three levels, framed by an Assessment Guide, opening up progression to the next level or, at the end, the award of PGCE and progression into induction.

The curriculum tutor is based at the university and supports student teachers within their subject area or phase of expertise. They support online learning with online seminars, managing forum discussions and reviewing student progress. School-based mentors support the student teacher on a day-to-day basis. They provide support for student teachers to plan, teach, evaluate and assess learning. School-based mentors submit regular formative feedback and complete formal lesson observations. Practice tutors have a similar role to a more traditional ITE university tutor. They bring a blend of experiential learning and the linking of theory and practice, visiting the student in their school and assessing students in relation to the fulfilment of Qualified Teacher Status descriptors of the Professional Standards for Teaching and Leadership (Welsh Government, Citation2017b). They also coach the school-based mentors.

The Open University Partnership PGCE programme is modular in structure with flexible entry and exit points. This means that student teachers can adopt variable study patterns throughout the course; sometimes full-time – sometimes part-time. Student teachers, together with their university curriculum tutor and school-based mentor, negotiate study patterns that meet their personal circumstances and which enable them to satisfy existing personal, domestic and professional commitments. The PGCE is structured so that teaching theory is combined with substantial, supported, practice learning in schools. The programme is delivered via six thematic strands which are each revisited at the three levels (familiarisation, consolidation and autonomy):

Thematic strands:

Curriculum

Understanding learners

Planning for learning

Pedagogy

Assessment

Professional practice.

Each of the programme’s strands are revisited in the form of free-standing online modules. The modules are integrated with video material in Welsh and English gathered from schools throughout Wales. These resources engage student teachers with the main ideas underpinning ITE. This is a spiral approach to curriculum (Bruner, Citation1960). Topics are revisited in increasing levels of complexity as knowledge and understanding deepens, and previous learning is built upon (Dowding, Citation1993; Harden & Stamper, Citation1999; Woodward, Citation2019). An important feature of this is the way that these key issues are developed by “in-school” activities. In a form of “constructive alignment” each level of the course is linked with a period of practice learning in school (Briggs & Tang, Citation2011, p. 11). At the end of each level, student teachers produce an assessment e-portfolio.

The programme’s theoretical position

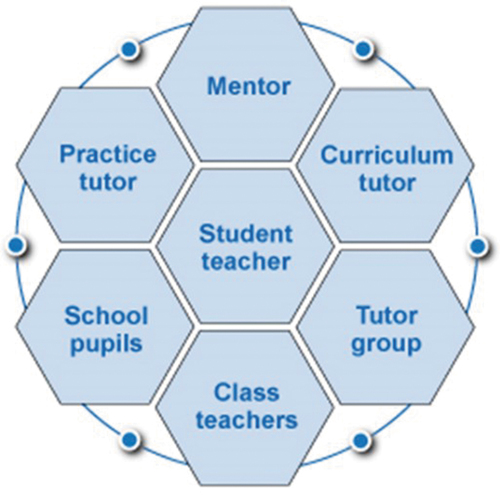

The structure outlined is a manifestation of the drivers discussed earlier, which in turn are reflections of different theoretical positions. The PGCE framework is underpinned by the principles that student teachers’ professional knowledge is co-constructed through interactions between the student and their mentor, their curriculum tutor, fellow student-teachers and a practice tutor, and through their ongoing interactions with pupils. This draws on the ideas of Shulman and Shulman (Citation2004), Cochran-Smith and Lytle (Citation1999) and Wenger (Citation1998), among others. Co-participation and co-construction approaches are also viewed as important in the development of creativity in education (Craft et al., Citation2014). Student-teachers’ learning is a complex and individual process supported by the community, with collaborative co-construction working habits critical and beneficial for student teachers to develop (Bush & Grotjohann, Citation2020; DeLuca, Ogden, & Pero, Citation2015). The members of this PGCE student teacher’s community are illustrated in .

Each of the actors in the student teacher’s community are engaged in this landscape of practice (Wenger, McDermott, & Synder, Citation2002; Wenger & Wenger-Traynor, Citation2015). All provide different perspectives on the knowledge that contribute to a teacher’s personal teaching construct (Furlong, Citation2020; Furlong, Hagger, & Butcher, Citation2006). These different perspectives are facilitated through an approach to blended learning that eases the barriers of time and location for study and collaboration. Through activities that encourage research-informed clinical practice, the programme actively engages student-teachers in the critical gathering of evidence and alternative perspectives to focus on creativity and criticality in their teaching (Burn & Mutton, Citation2015; Hoidn & Kärkkäinen, Citation2014; Lucas, Citation2016; Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Citation2020b; Vincent-Lancrin et al., Citation2019).

The “knowledge base” for teaching identified by the PGCE partnership centres on a commitment to develop effective pedagogical approaches which is underpinned by a knowledge of relevant theory (knowledge for practice), alongside knowledge in practice and knowledge of practice (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, Citation1999). Knowledge for practice refers to the sense of knowing relevant subject matter and appropriate instructional approaches with skilled teachers possessing “deep knowledge” with a clear understanding of the most effective teaching and learning strategies (Darling-Hammond, Citation2008, p. 334; Shulman, Citation1987, p. 20). This can be garnered from a range of relevant sources, with practising teachers acknowledged to have “insights [.] knowledge, skills and dispositions” to support student teachers (Reynolds, Citation1989, p. 138). Teachers need to acquire different kinds of knowledge and expertise. This includes a deep subject knowledge, for unless this is secure and teachers are confident the result could be a lack of both insightful questioning and wide-ranging discussions in the classroom (Hagger & McIntyre, Citation2006). Yet, this acquisition of knowledge takes place over time and opportunities to link prior learning to new understanding is needed (Cochran-Smith & Demers, Citation2008; Cochran-Smith & Lytle, Citation1999; Feiman-Nemser, Citation2008).

Knowledge in practice focuses on action and the knowledge gained from experience. Reflection on knowledge results in effective teachers considering alternative approaches and working with others provides opportunity for this. Experienced practitioners have this knowledge embedded in their practice and student-teachers need to be supported to develop their practical skills (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, Citation1999; McAllister, Citation2015). As discussed, a student teacher’s experiences of teaching, and the feedback they receive, allow them to co-construct their teaching knowledge in context and regular collaboration between university and the school partners is critical for this to be effective (Furlong et al., Citation2006). However, although this source of knowledge for student teachers is becoming more valued, careful thought is required to ensure student teachers can observe experienced practitioners and know what they need to learn from the complex knowledge that is available (Hagger & McIntyre, Citation2006).

Knowledge of practice focuses on exchanges with the school-based mentor, practice tutor and the student teacher’s peer group – as this knowledge is very much “open to discussion” (Cochran-Smith & Lytle, Citation1999, p. 272). This element is distinct to the formal and practical knowledge discussed above as it is via inquiry that student teachers problematise their knowledge and practice by constructing their knowledge collectively and collaboratively within their communities. This construction and reconstruction can be transformational as it challenges existing knowledge and provides opportunity to explore and question understanding and practice by engaging with others by undertaking action research that can contribute to educational theory and new knowledge (Hargreaves, Citation1996; Noffke, Citation1997).

The approach adopted by this PGCE is therefore that knowledge for practice focuses on what is already known by the experts as a result of research and theory development; the outside experts/ the curriculum tutor. Knowledge in practice refers to that knowledge held by practitioners/ the class teacher/ the mentor/ the practice tutor and this is developed through activities that question beliefs and practice. Knowledge of practice is developed through student activities that problematise teaching and learning with a focus on collaborative research. Consequently, student teachers will develop a “strong pedagogy based on an understanding of what works” (Welsh Government, Citation2014, p. 12). This PGCE emphasises the significance of both the process of teaching and the development of subject knowledge. This is exemplified by video examples of effective professional practice, online forums and seminars for students to share ideas and resources, and one to one and group mentor sessions between students and their school-based mentors. All of which contribute to a pre-service programme that is “practical and intellectually challenging” (Welsh Government, Citation2018a, p. 9).

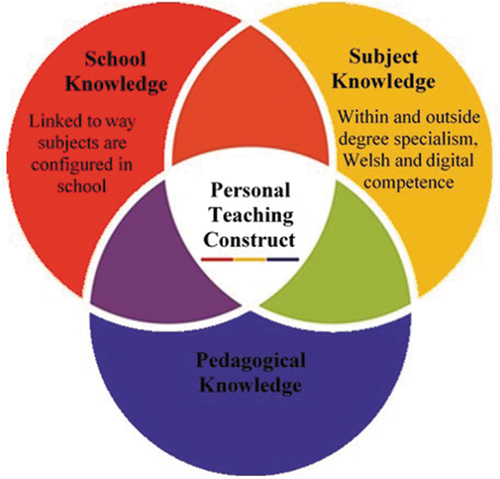

Pedagogical knowledge is a major component of the professional standards as “the teacher consistently secures the best outcomes for learners through progressively refining teaching, influencing learners and advancing learning” (Welsh Government, Citation2017b, p. 16). However, unlike Shulman’s account of pedagogical knowledge, where teachers draw their “equipment” that presents particular content this route into teaching demands a more creative approach to teaching and learning (Shulman, Citation1986, p. 10). This is reflected in the professional standards too, along with an appreciation of learning through experience supported with an understanding of how children learn (Kolb, Citation2015; Morris, Citation2020). An understanding of school knowledge is also critical. Informed by the work of Chevallard (Citation1985), each subject, or as they are referred to in the new Curriculum for Wales each – Area of Learning and Experience, undergoes a process of restructuring for it to become teachable and accessible for learners. It is a teacher’s knowledge of their learners and their individual needs that ensure the teacher makes the subject accessible. In doing this a distinctive type of knowledge is formulated. For example, “school mathematics” (Chevallard & Bosch, Citation2014). This understanding of aspects of each subject, and the relationship to the “four purposes” of the new curriculum in Wales are developed during the student teachers’ interactions with the mentor and others during school experience, online study and seminars. The “four purposes” provide the shared vision for the new curriculum in Wales that all learners will become ambitious, capable learners, ready to learn throughout their lives; enterprising, creative contributors, ready to play a full part in life and work; ethical, informed citizens of Wales and the world; and healthy, confident individuals, ready to lead fulfiling lives as valued members of society (Welsh Government, Citation2021b).

The student-teacher’s “personal construct” is at the centre of the dynamic process of the different aspects of professional knowledge. Illustrated in (), these are a complex amalgam of past knowledge, experiences of learning, a personal view of what constitutes “good” teaching’ as well as learning from others such as peers and teachers in an almost “constant interaction with other adults and children” (Tatto, Burn, Menter, Mutton, & Thompson, Citation2018, p. 3). The student teacher also needs to clarify their belief in the purposes of what they see in the curriculum or in their subject and why they wish to teach it. All of this underpins a teacher’s professional knowledge and a student teacher must discover, articulate, test and re-test this personal teaching construct as they move through the stages of the programme and gain experience in schools. The opportunities provided by the new PGCE for people to move from alternative careers to train to teach adds another dimension to the development of personal teaching constructs as some will have extensive experience outside education that will be influential in informing teacher identity and a multi-dimensional teacher workforce (Williams, Citation2013).

Figure 2. The different aspects of teacher professional knowledge (adapted from Banks, Leach, & Moon, Citation2005, p. 338)

A personal teaching construct is in development for any teacher as they respond to teaching innovation and curriculum development. However, a novice teacher has to question their initial personal beliefs about their subject and assumed practice; and develop their pedagogical approach as they work with mentors and the learners to address and co-construct a rationale for their classroom behaviours (Korthagen, Citation2004; Simić, Jokić, & Vukelić, Citation2019). Similarly, it is important to note that a student teacher also needs to instil positive lifelong learning aspirations. The disposition to acquire skills for lifelong learning is also critical for the student teacher as well (Mutton, Burn, & Hagger, Citation2010). The new PGCE supports this within the course content and the opportunities available to the student teachers as an Open University student. The online course materials remain available to student teachers for a few years after they complete the qualification, for them to revisit as required. There are also multiple opportunities for student teachers to engage with wider Open University materials and the programme awards Masters level credits, which means students can follow on with this level of study later should they wish (Orchard & Winch, Citation2015; Toom et al., Citation2010; Williams, Citation2020).

The new PGCE contributes to the Welsh Government’s Welsh-medium Education Strategy’s priorities. The programme is offered through the medium of Welsh ensuring the teaching workforce is building capacity with new teachers who possess high-quality Welsh language skills and competence in teaching methods (Welsh Assembly Government, Citation2010; Welsh Government, Citation2017c). All student teachers’ understanding of the wider Welsh culture and heritage alongside their skills in Welsh reading, writing, speaking and listening are developed throughout. The support offered is matched according to each student’s level. This support not only develops student teachers’ Welsh language skills but those of their learners too. The pedagogical approaches for the use of Welsh in teaching and learning are supported for student teachers to embed Curriculum Cymreig and demonstrate commitment to Welsh language and culture (Donaldson, Citation2015).

Digital competence is also important in the preparation of all teachers as they support learning for the 21st century, particularly with it reported that teacher training courses can lack in preparation for this (Fernandez-Batanero, Montenegro-Rueda, Fernandez-Cerero, & Garcia-Martinez, Citation2019). The very nature of the programme’s remote flexible delivery approach, along with the course content that has digital technologies and information literacy at its core all contribute to preparing teachers effectively (Digital Classroom Teaching Task and Finish Group, Citation2012; Şentürk, Citation2020). The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on the application of digital technologies for learning has been widespread and increasingly documented (Baber, Citation2020; Adedoyin & Soykan, Citation2020; la Velle, Newman, Montgomery, & Hyatt, Citation2020; Radha, Mahalakshmi, Satish Kumar, & Saravanakumar, Citation2020). This new route into teaching has been able to accommodate schools’ move to online learning and support the wider education sector in Wales during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Conclusion

There are many challenges experienced by countries as they strive to recruit and retain high-quality teachers (Egan et al., Citation2019; Podolsky et al., Citation2019; UNESCO, Citation2016). For Wales, poor PISA results and the consequent reviews of its education system have culminated in ongoing education reform. One critical element of this is ensuring that the teacher workforce has the capacity and capability to develop and implement a new curriculum for Wales. Therefore, ITE reform is important in contributing to this reform. ITE also has a significant role to fulfil in improving the Welsh language capacity of the teacher workforce, addressing subject shortages and the lack of diversity in the teaching profession. Joint responsibility for ITE between schools and universities lies at the centre of this for Wales. Links between school and university learning, and positioning research as the principle element for ITE are driving change across the sector (Welsh Government, Citation2018a, Citation2017a).

The development and delivery of the new flexible PGCE programme discussed here are in response to these drivers. The two-year part-time or salaried route into teaching is delivered via a blend of face-to-face practice and distance learning. This programme is available across the whole of Wales. Therefore, some of the barriers that can prevent entry into the teaching profession, such as living a long way from a university and/or having other commitments are addressed (Welsh Government, Citation2019).

The Open University Partnership PGCE offers a hybrid blended open learning approach, with the student teacher at the centre. Online materials, seminars, practice in schools and progressive assessments provide the structure for the PGCE experience. In combining theory with substantive, supported periods of practice in schools student teachers are equipped to explore theory and practice. The underpinning theory of the PGCE centres on the key principle that professional knowledge is co-constructed (Craft et al., Citation2014; Cochran-Smith & Lytle, Citation1999; Shulman & Shulman, Citation2004; Wenger, Citation1998). Those supporting the co-construction offer differing perspectives that influence each individual student teacher’s personal teaching construct (Furlong, Citation2020; Tatto et al., Citation2018). Research-informed practice also ensures the student teachers are engaged in evidence gathering to critically inform their practice (Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Citation2020b). The process of teaching and the development of subject knowledge is emphasised. This has resulted in a teacher training programme that is both practical and challenging (Welsh Government, Citation2018a). However, interwoven throughout are the “four purposes”, which provide the vision for the imminent new curriculum for Wales (Welsh Government, Citation2021b).

It is proposed that the experiences of the programme’s participants are explored in future. This would begin to establish the impact of the new flexible route into teaching on diversifying the teacher workforce and the effectiveness of the flexible route. Nevertheless, this discussion begins to demonstrate that in offering a more flexible route into the teaching profession, it is possible to address government policy directives, that focus on workforce capacity and capability, while at the same time ensure a robust learner-centred approach to training new teachers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Adedoyin, O. B., & Soykan, E. (2020). Covid-19 pandemic and online learning: The challenges and opportunities. Interactive Learning Environments, Retrieved 18 October 2021. h ttps://d oi.org.1 0.1080/10494820.2020.1813180

- Baber, H. (2020). Determinants of students’ perceived learning outcome and satisfaction in online learning during the pandemic of COVID 19. Journal of Education and e-Learning Research, 7(3), 285–292.

- Banks, F., Leach, J., & Moon, B. (2005). Extract from New understandings of teachers’ pedagogic knowledge. The Curriculum Journal, 16(3), 331–340.

- Briggs, J., & Tang, C. (2011). Teaching for quality learning at university (Fourth ed.). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Bruner, J. (1960). the process of education. USA: Harvard University Press.

- Brussino, O. (2021). OECD education working papers No. 256. building capacity for inclusive teaching: Policies and practices to prepare all teachers for diversity and inclusion. Retrieved 26 October 2021 from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/building-capacity-for-inclusive-teaching_57fe6a38-en

- Burn, K., & Mutton, T. (2015). A review of ‘research-informed clinical practice’ in initial teacher education. Oxford Review of Education, 41(2), 217–233.

- Bush, A., & Grotjohann, N. (2020). Collaboration in teacher education: A cross-sectional study on future teachers’ attitudes towards collaboration, their intentions to collaborate and their performance of collaboration. Teaching and Teacher Education, 88, 1–9.

- Chevallard, Y., (1985). La Transposition Didactique. Du savoir savant au savoir enseigné. (2nd edn), La Pensée sauvage. Grenoble. .

- Chevallard, Y., & Bosch, M. (2014). Didactic transposition in mathematics education. In S. Lerman (Ed.), Encyclopaedia of mathematics education. Dordrecht: Springer Retrieved 18 October 2021. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-4978-8_48.

- Cochran-Smith, M., & Demers, K. E. (2008). How do we know what we know? In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, D. J. McIntyre, & K. E. Demers (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education enduring questions in changing contexts (Third ed., pp. 1009–1016). USA: Routledge.

- Cochran-Smith, M., Grudnoff, L., Orland-Barak, L., & Smith, K. (2020). Educating teacher educators: International perspectives. The New Educator, 16(1), 5–24.

- Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (1999). Relationships of knowledge and practice: Teacher learning in communities. Review of Research in Education, 24, 249–305.

- Craft, A., Cremin, T., ., P. & Hay, P., Clack, J., (2014). Creative primary schools: developing and maintaining pedagogy for creativity. Ethnography and Education, 9(1), pp. 16–34

- Cranston-Gingras, A., Alvarez Mchatton, P. M., Allsopp, D. H., Colucci, K., Hoppey, D., & Hahn, S. (2019). Breaking the mold: Lessons learned from a teacher education program’s attempt to innovate. The New Educator, 15(1), 30–50.

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2008). The case for university-based teacher education. In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, D. J. McIntyre, & K. E. Demers (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education enduring questions in changing contexts (Third ed., pp. 333–346). USA: Routledge.

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher education around the world: What can we learn from international practice? European Journal of Teacher Education, 40(3), 291–309.

- DeLuca, C., Ogden, H., & Pero, E. (2015). Reconceptualizing elementary preservice teacher education: Examining an integrated-curriculum approach. The New Educator, 11(3), 227–250.

- Digital Classroom Teaching Task and Finish Group (2012). Find it, make it, use it, share it: learning in digital Wales. Retrieved 18 October 2021 from https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/14060/

- Donaldson, G. (2015). Successful Futures; An independent review of curriculum and assessment arrangements in Wales. Retrieved 18 August 2021 from https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2018-03/successful-futures.pdf

- Dowding, T. J. (1993). The application of a spiral curriculum model to technical training curricula. Educational Technology, 33(7), 18–28.

- Education Workforce Council (2020a). Policy Briefing: Teacher recruitment and retention in Wales. Retrieved 18 August 2021 from https://www.ewc.wales/site/index.php/en/research-and-statistics/ewc-research-and-policy-advice/policy-briefings.html

- Education Workforce Council (2020b). Annual education workforce statistics for Wales 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2021 from https://www.ewc.wales/site/index.php/en/research-and-statistics/workforce-statistics.html

- Education Workforce Council (2021). Education workforce statistics. Retrieved 3 September 2021 from https://www.ewc.wales/site/index.php/en/research-and-statistics/workforce-statistics.html#initial-teacher-education-student-results

- Egan, D., Longville, J., & Milton, E. (2019). Graduate recruitment: Teaching and other professions. A Research report for the Education Workforce Council. Wales: Cardiff Metropolitan University and Cardiff University.

- Feiman-Nemser, S. (2008). How do people learn to teach? Teacher learning over time. In M. Cochran-Smith, S. Feiman-Nemser, D. J. McIntyre, & K. E. Demers (Eds.), Handbook of research on teacher education enduring questions in changing contexts (Third ed., pp. 697–705). USA: Routledge.

- Fernandez-Batanero, J. M., Montenegro-Rueda, M., Fernandez-Cerero, J., & Garcia-Martinez, I. (2019). Digital competences for teacher professional development, Systematic review. European Journal of Teacher Education. doi:10.1080/02619768.2020.1827389

- Furlong, J. (2013). Globalisation, neoliberalism, and the reform of teacher education in England. The Educational Forum, 77(1), 28–50.

- Furlong, J. (2015). Teaching Tomorrow’s Teachers: Options for the future of initial teacher education in Wales. Retrieved 18 October 2021 from https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2018-03/teaching-tomorrow%E2%80%99s-teachers.pdf

- Furlong, J. (2020). Re-forming initial teacher education in wales: A personal review of the literature. Wales Journal of Education, 22(1), 37–58.

- Furlong, J., Hagger, H., & Butcher, C. (2006). Review of initial teacher training provision in wales. A report to the welsh assembly government.

- Ghosh, A., & Worth, J. (2020). Teacher labour market in wales annual report 2020. Slough: NFER. Retrieved 18 October 2021 from https://www.nfer.ac.uk/teacher-labour-market-in-wales-annual-report-2020/

- Hagger, H., & McIntyre, D. (2006). Learning teaching from teachers: Realising the potential of school-based teacher education. UK: Open University Press.

- Harden, R. M., & Stamper, N. (1999). What is a spiral curriculum? Medical Teacher, 21(2), 141–143.

- Hargreaves, A. (1996). Transforming Knowledge: Blurring the boundaries between research, policy and practice. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 18(2), 105–122.

- Hoidn, S., & Kärkkäinen, K.(2014).Promoting skills for innovation in higher education: A literature review on the effectiveness of problem-based learning and of teaching behaviours.OECD education working papers. 100. Paris: OECD Publishing. Retrieved 18 October 2021 from.https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/promoting-skills-for-innovation-in-higher-education_5k3tsj67l226-en.

- Kolb, D. (2015). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development (Second ed.). USA: Pearson Education Inc.

- Korthagen, F. A. J. (2004). In search of the essence of a good teacher: Towards a more holistic approach in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 20(1), 77–97.

- la Velle, L., Newman, S., Montgomery, C., & Hyatt, D. (2020). Initial teacher education in England and the Covid-19 pandemic: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(4), 596–608.

- Lester, B., & Price, R. (2020). Ethnic minority representation within the school workforce in wales. phase 2 report for the welsh government. Retrieved 18 October 2021 from https://www.ewc.wales/site/index.php/en/research-and-statistics/ewc-research-and-policy-advice/ewc-research/increasing-diversity-within-the-school-workforce-in-wales.html

- Lucas, B. (2016). A five-dimensional model of creativity and its assessment in schools. Applied Measurement in Education, 29(4), 278–290.

- McAllister, J. (2015). the idea of a university and school partnership. In R. Heilbronn & L. Foreman-Peck (Eds.), Philosophical perspectives on teacher education (pp. 38–54). UK: Wiley Blackwell.

- Morris, T. H. (2020). Experiential learning – A systematic review and revision of Kolb’s model. Interactive Learning Environments, 28(8), 1064–1077.

- Mutton, T., & Burn, K. (2020). Doing things differently: Responding to the ‘policy problem’ of teacher education in wales. Wales Journal of Education, 22(1), 82–109.

- Mutton, T., Burn, K., & Hagger, H. (2010). Making sense of learning to teach: Learners in context. Research Papers in Education, 25(1), 73–91.

- Noffke, S. E. (1997). Professional, personal, and political dimensions of action research. Review of Research in Education, 22, 305–343.

- The Open University (2021a). Facts and figures. Retrieved 18 October 2021 from https://www.open.ac.uk/about/main/strategy-and-policies/facts-and-figures

- The Open University (2021b). About us. Retrieved 18 October 2021 from https://www.open.ac.uk/wales/en/about-us

- The Open University (2021c). A new way to become a teacher. Retrieved 25 October 2021 from https://www.open.ac.uk/courses/choose/wales/pgce

- Orchard, J., & Winch, C. (2015). What training do teachers need? Why theory is necessary to good teaching. Impact, 22, 1–43.

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. (2014). Improving schools in Wales: An OECD Perspective. Retrieved 18 October 2021 from http://www.oecd.org/education/Improving-schools-in-Wales.pdf

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. (2017). The welsh education reform journey: A rapid policy assessment. Retrieved 25 October 2021 from https://www.oecd.org/education/The-Welsh-Education-Reform-Journey-FINAL.pdf

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. (2018). Developing schools as learning organisations in Wales. Retrieved 25 October 2021 from https://www.oecd.org/education/Developing-Schools-as-Learning-Organisations-in-Wales-Highlights.pdf

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. (2020a). Achieving the new curriculum for wales, implementing education policies, Paris: OECD Publishing. Retrieved 18 September 2021 from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/achieving-the-new-curriculum-for-wales_4b483953-en

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. (2020b). Teaching, assessing and learning creative and critical thinking skills in primary and secondary education. Retrieved 10 October 2021 from http://www.oecd.org/education/ceri/assessingprogressionincreativeandcriticalthinkingskillsineducation.htm

- Podolsky, A., Kini, T., Darling-Hammond, L., & Bishop, J. (2019). Strategies for attracting and retaining educators: What does the evidence say? Education Policy Analysis Archive, 27(38), 1–47.

- Radha, R., Mahalakshmi, K., Satish Kumar, V., & Saravanakumar, A. R. (2020). E-learning during lockdown of covid-19 pandemic: A global perspective. International Journal of Control and Automation, 13(4), 1088–1099.

- Reynolds, M. C. (1989). Knowledge base for the beginning teacher. UK: Pergamon Press for the American Association of Colleges for teacher Education.

- See, B. H., & Gorard, S. (2020). Why don’t we have enough teachers? A reconsideration of the available evidence. Research Papers in Education, 35(4), 416–442.

- Şentürk, C. (2020). Effects of the blended learning model on preservice teachers’ academic achievements and twenty-first century skills. Education and Information Technologies. doi:10.1007/s10639-020-10340-y

- Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4–14.

- Shulman, L. (1987). Knowledge and Teaching: Foundations of the New Reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), pp. 1–23

- Shulman, L. S., & Shulman, J. H. (2004). How and what teachers learn: A shifting perspective. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 36(2), 257–271.

- Simić, N., Jokić, T., & Vukelić, M. (2019). Personal construct psychology in preservice teacher education: The path toward reflexivity. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 32(1), 1–17.

- Tatto, M. T., Burn, K., Menter, I., Mutton, T., & Thompson, I. (2018). Learning to Teach in England and the USA: The evolution of policy and practice. UK: Routledge.

- Toom, A., Kynäslahti, H., Krokfors, L., Jyrhämä, R., Byman, R., Stenberg, K., & Pertti Kansanen, P. (2010). Experiences of a research‐based approach to teacher education: Suggestions for future policies. European Journal of Education, Research, Development and Policy, 45(2), 331–344.

- UNESCO (2016). The world needs almost 69 million new teachers to reach the 2030 education goals. Retrieved 18 October 2021 from http://uis.unesco.org/en/files/fs39-world-needs-almost-69-million-new-teachers-reach-2030-education-goals-2016-en-pdf

- Vincent-Lancrin, S., González-Sancho, C., Bouckaert, M., de Luca, F., Fernández-Barrerra, M., Jacotin, G., & Vidal, Q. (2019). Fostering Students’ Creativity and Critical Thinking: What it Means in School, Educational Research and Innovation , OECD Publishing, Paris. Retrieved 18 October 2019. Retrieved from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/fostering-students-creativity-and-critical-thinking_62212c37-en

- Welsh Assembly Government. (2010). Welsh-medium education strategy information document No: 083/2010 (Cardiff: Welsh Assembly Government).

- Welsh Government. (2014). Qualified for Life: An education improvement plan for 3 to 19-year-olds in Wales (Cardiff: Welsh Assembly Government).

- Welsh Government (2017a). Education in Wales: Our National Mission Action plan 2017-21. Retrieved 18 September 2021 from https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2018-03/education-in-wales-our-national-mission.pdf

- Welsh Government (2017b). Professional standards. Retrieved 18 October 2021 from https://hwb.gov.wales/professional-development/professional-standards/

- Welsh Government (2017c). Welsh in education Action plan 2017-21. Retrieved 18 October 2021 from https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2018-02/welsh-in-education-action-plan-2017%E2%80%9321.pdf

- Welsh Government (2018a). Criteria for the accreditation of initial teacher education programmes in Wales. Retrieved 18 October 2021 from https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2018-09/criteria-for-the-accreditation-of-initial-teacher-education-programmes-in-wales.pdf

- Welsh Government (2018b). Rural education action plan. Retrieved 25 October 2021 from https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2018-10/rural-education-action-plan-1.pdf

- Welsh Government (2019). Investing in an excellent workforce. Retrieved 18 September 2021 from https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2019-02/investing-in-an-excellent-workforce.pdf

- Welsh Government (2020a). Key facts: Ethnic diversity in schools. Retrieved 18 October 2021 from https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2020-12/ethnic-diversity-in-schools.pdf

- Welsh Government (2020b). Additional learning needs (ALN) transformation programme. Retrieved 25 October 2021 from https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2020-09/additional-learning-needs-aln-transformation-programme-guide.pdf

- Welsh Government (2020c). Education in Wales: Our national mission Update October 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2021 from https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2020-10/education-in-Wales-our-national-mission-update-october-2020.pdf

- Welsh Government (2021a). Developing a vision for curriculum design. https://hwb.gov.wales/curriculum-for-wales/designing-your-curriculum/developing-a-vision-for-curriculum-design/#curriculum-design-and-the-four-purposes

- Welsh Government (2021b) Statistical Bulletin: Initial Teacher Education Wales, 2019/20. Retrieved 18 September 2021 from https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/statistics-and-research/2021-05/initial-teacher-education-september-2019-august-2020-780.pdf

- Welsh Government (2021c). Initial Teacher Education Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic Recruitment plan, Retrieved 18 November 2021. https://gov.wales/initial-teacher-education-black-asian-and-minority-ethnic-recruitment-plan-htm

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice. learning, meaning and identity. UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Synder, W. M. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice. USA: Harvard Business School Publishing.

- Wenger, E., & Wenger-Traynor, B. (2015) Introduction to communities of practice, Retrieved18 September 2021. from https://wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice/

- Williams, J. (2013). Constructing new professional identities: Career changers in Teacher Education. The Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

- Williams, K. (2020). Written Statement: National Masters in Education Retrieved 21 October 2021. from https://gov.wales/written-statement-national-masters-education

- Williams, C. (2021). Black, asian and minority ethnic communities, contributions and cynefin in the new curriculum working group, final report. Retrieved 18 September 2021 from https://gov.wales/sites/default/files/publications/2021-03/black-asian-minority-ethnic-communities-contributions-cynefin-new-curriculum-working-group-final-report.pdf

- Woodward, R. (2019). The spiral curriculum in higher education: analysis in pedagogic context and a business studies application. e-Journal of Business Education & Scholarship of Teaching, 13(3), 14–26.