ABSTRACT

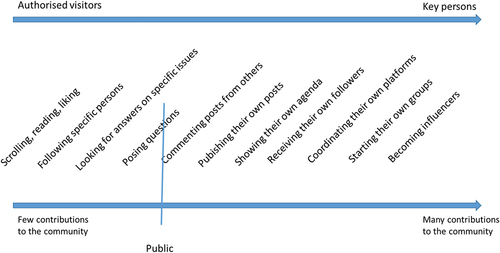

This article reports a study on members in self-organised Facebook groups for teachers. The aim is to investigate how teachers’ needs and actions form their roles in the extended staffroom. 26 teachers from six different Facebook groups within two different school subjects, mathematics and Swedish, are interviewed. The results reveal a trajectory from a lurking behaviour as authorised visitor to a key person within the community of the group or an influencer, where teachers can function as authorities in their field. In relation to this trajectory, the interviewed teachers describe the choice to become public as a crucial step, emphasising the courage needed. A next important step can be identified when teachers leave the role as consumers of content that others provide, asking questions and commenting on others’ posts, in favour of a more contributing role, publishing their own posts and expressing an agenda. Further, these kinds of large Facebook groups can be seen as a node in teachers’ social media networks.

Introduction

Studies over the last 20 years have shown an increasing use of social media as a means for in-service teachers to develop professionally (Lantz-Andersson, Lundin, & Selwyn, Citation2018). In particular, teacher Facebook groups have proven to offer participants a site for development of sustainable professional learning communities (PLCs) (Bissessar, Citation2014; Muls et al., Citation2019; Ranieri, Manca, & Fini, Citation2012). Understanding teacher Facebook groups as communities focuses on the participation structure, the tools used for communication and the social aspects of learning in the community. It also raises questions about how such ePLCs (Liljekvist, van Bommel, & Olin-Scheller, Citation2017) differ from local PLCs at schools, and what goals this “extended staffroom” serves that the local staffroom does not. To understand how the teachers’ needs and actions form their roles and shape the online teacher community is the core of interest in this article. The study is based on interviews with 26 teachers from six different Facebook groups formed and maintained by teachers within two different school subjects, mathematics and Swedish. Teacher Facebook groups attract a high proportion of teachers in Sweden. One of the groups in mathematics has 19,352 members (16 September 2021) and one of the groups in Swedish has 16, 493 members (16 September 2021). Across all levels of schooling, the number of teachers teaching mathematics is almost 50,000 and the number of teachers teaching Swedish is slightly over 50,000 (The Swedish National Agency for Education, Citation2021). To illustrate the importance of online teacher communities further, the interviewed teachers are members of five, ten or even twenty additional teacher Facebook groups, mostly national.

Previous studies have established the usefulness of this bottom-up movement. In particular, it has proven to offer teachers an extended staffroom where they can ask for and offer help on daily issues in the classroom (c.f. Lantz-Andersson, Peterson, Hillman, Lundin, & Bergviken-Rensfeldt, Citation2017; Randahl, Citation2018). However, there is a need for a better understanding of how participating members organise, maintain, and develop these huge extended staffrooms to which one in every three teachers in Sweden belongs.

Aim and research questions

The aim of this article is to investigate how teachers’ needs and actions form their roles and shape the online teacher community. The following three questions are posed:

What purposes and needs are displayed by participants in the extended staffroom?

What roles do teachers adopt when participating?

How does Facebook as a platform shape the teachers’ participation?

Theoretical lens

Each of the teacher Facebook groups studied here can be described as a Community of Practice (CoP) (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991; Wenger, Citation2006). Wenger defines CoPs as “groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly” (Wenger, Citation2006, p. 1). A CoP develops over three elements: the domain, which is constituted by members with a shared interest in which they have competence that separates them from others, the community, which is characterised by engagement in joint activities such as sharing information and building relationships, and the practice, where the members are practitioners aiming at developing a collaborative collection of knowledge and resources. In this paper the community is in focus, and the development of an identity as a member of it (cf. Lundin, Lantz-Andersson, & Hillman, Citation2017). This process is argued to be affected by three different modes of belonging to the community: engagement, imagination, and alignment (Wenger, Citation1998). Wenger, McDermott, and Snyder (Citation2002) state that new technologies are rapidly changing the conditions for forming and distributing CoPs. For example, it is easy to enter or leave social media groups. How this fact influences and enables members to move from more peripheral roles into more expert roles will be further developed in this study.

Literature review

Understanding teacher Facebook groups as professional communities means conceptualising them as social groups where members interact to promote professional development. A substantial amount of research into online teacher communities has also shown that these use social media principally to address issues related to teachers’ practice (Ranieri et al., Citation2012; Tour, Citation2017; Vangrieken, Meredith, Packer, & Kyndt, Citation2017). In a previous study of content in 553 interactions in six different Facebook groups (van Bommel, Randahl, Liljekvist, & Ruthven, Citation2020), 71% could be related to Shulman’s framework of categories describing teachers’ professional knowledge base (Shulman, Citation1987). These interactions in turn predominantly involved threads focusing on pedagogical content knowledge, PCK. Teachers contribute to the community by offering examples of successful teaching experiences or by answering questions raised by other members (Liljekvist, Randahl, van Bommel, & Olin-Scheller, Citation2020). Many of the interactions can be characterised as transactions between teachers, where knowledge is offered and accepted (van Bommel et al., Citation2020, see also Rosenberg et al., Citation2020). Former studies of interactional patterns in such environments have described them as pragmatic rather than reflective, leaving little room for critical discussions or a more inquiry-based learning (Kelly & Antonio, Citation2016). This kind of exchange has been interpreted as a result of teachers’ working conditions, which do not seem to leave enough time to prepare lessons (Tsiotakis & Jimoyiannis, Citation2016). In terms of professional collegiality, then, this sharing practice can be seen as a caring practice (c.f. Carpenter & Krutka, Citation2015). In our own research, we have found it valuable to distinguish between two levels of knowledge-sharing: transaction and transformation (van Bommel et al., Citation2020). The level of transaction is one of participants sharing knowledge, the level of transformation one in which exchange in knowledge is expressed further in participants’ learning or changed participation (Brown & Munger, Citation2010; Lave & Wenger, Citation1991; Sahlström, Citation2009;). Transformations could be identified in 11% of the interactions and were more likely to occur in longer interactions with 10 comments or more.

The growth of professional groups on social media, particularly on Facebook, has led to studies where teachers, via interviews or self-reports, elaborate on advantages and benefits of such groups for their work. Teachers highlight collegial support as an important benefit (Liu, Miller, & Jahng, Citation2016; Macià & García, Citation2016; Ranieri et al., Citation2012). In particular, the sharing of personal classroom experiences and resources for classroom use is reported as a way to provide teachers with new ideas and to support changing classroom practice, in formally organised as well as informally developed online teacher communities (Lantz-Anderssson et al., Citation2018). In informally developed online teacher communities, the context for this paper, teachers also emphasise a form of emotional support. It is argued that this type of support results from the non-hierarchical structure, with low barriers which makes it easy and safe to ask for advice (Booth, Citation2012; Visser, Evering, & Barrett, Citation2014). In research on professional learning communities in face-to-face teacher groups, mutual trust is considered important to foster and maintain a thriving community (Stoll, Bolam, McMahon, Wallace, & Thomas, Citation2006). From a linguistic view, a supporting community can be characterised in terms of response patterns. Particular types of contribution seek particular types of affirmation. A question seeks an answer, an offer wants to be accepted, and the desired response to a statement is an acknowledgement. An examination of interactional patterns (Halliday & Matthiessen, Citation2013) found that only 2% of the posts got a solely discretionary, not predicted, response. Statements were seldom questioned or challenged (Randahl, Citation2018). On the one hand, this lack of critical friends can decrease the chance of in-depth discussions or competing input (Kelly & Antonio, Citation2016); on the other hand, a friendly culture helps build a community where members dare to take risks (Krutka, Carpenter, & Trust, Citation2016).

Besides being a platform for sharing new ideas and a supportive arena for professional growth, informally-developed online teacher communities also have a filtering function (Lantz-Andersson et al., Citation2018; Ranieri et al., Citation2012), where contributions from key participants or administrators set the agenda (Britt & Paulus, Citation2016; Rehm & Notten, Citation2016). Being a producer rather than a consumer affects participants’ self-esteem, allowing them to develop a sense of self as expert (Rodesiler, Citation2017; Wesely, Citation2013). This online persona can also be transferred into other contexts (Robson, Citation2016), not least teachers’ daily practice. Another role identified in online teacher communities is the lurker (Preece, Nonnecke, & Andrews, Citation2004), a rather pejorative term for the most common, and most passive, type of participant. However, this invisible form of participation provides an initial step for newcomers to access and learn the norms and values of the group, laying the ground for future posting and commenting (Zuidema, Citation2012). Prestridge (Citation2019) titles this kind of participant an info-consumer. She identifies three further roles that participating teachers take on: info-networker, self-seeking contributor, and vocationalist, which can be described as a key person in the online community. For the development of the group, Liu et al. (Citation2016) suggest that roles and responsibility need to be clearly defined but “freely chosen, freely modified, and freely discarded” (p. 438).

Teachers’ behaviour in online communities is often described as being characterised by a so-called participatory culture (Jenkins, Citation2006), where the audiences behave as both consumers and producers. Here, the contributors decide individually how they want to contribute and participate in the community, depending on their ability and interests. Moreover, in online communities characterised by participatory culture, an informal supporting structure relating of mentors and disciples emerges, which supports the processes of learning.

Facebook is not the only arena for informally developed online teacher communities. Twitter, in particular, is a commonly chosen platform for such communities (Carpenter & Krutka, Citation2015). Teachers also use other technologies such as websites, video, podcasts or blogging to enhance their professional development (Beach, Citation2017; Greenhow & Askari, Citation2017; Macià and García, Citation2018). To describe the networking aspect of the communities, the concept PLN, personal or professional learning network, is used (Krutka et al., Citation2016). The affordances of different platforms or technologies and how they shape teachers’ participation constitute an interesting area for future research (Lantz-Andersson et al., Citation2018).

Materials and methods

The results reported here draw on data collected in an interview study with teachers engaged in self-organised online groups. The interviews were conducted through telephone over a period of six months by three researchers and a research assistant within the project. To promote consistency in the interviews, a jointly developed and tested interview guide was used. The guide comprised four themes: main reasons to join teacher Facebook groups, role and activity in the groups, teacher Facebook groups as an extended staffroom, and ethical considerations. In all, the data consists of 26 audio recorded interviews (14 hrs. and 50 min.). For this paper, only parts of the interviews were analysed as described later.

Selection of participants

Our dataset consists of a stratified, random sample of posts and comments from six large (> 2,000 members each) teacher Facebook groups within two school subjects, mathematics and Swedish. The groups were public during the time of that part of the data collection. For a more detailed description, see van Bommel and Liljekvist (Citation2016). In order to contact teachers posting in the groups, we checked the dataset for the most active members. In the dataset, a total of 1,681 members posted something in the group, most of them (1,302) once or twice during the time of data collection. The most frequently posting member has 65 posts and there is a total of 61 members with 10 posts or more in the dataset. The participants in the interview study were strategically selected from all six Facebook groups.

First, high-activity teachers were detected, and sorted based on 1) school subject, 2) group, and 3) number of posts in the stratified random sample. Contact was made via Messenger with the most frequently posting member (then next in line, and so on) in each group, aiming at three positive respondents per group, 18 in total. In the message, the members were informed about the aim of the research project and their contribution to the study, the fact that participation is voluntary, and whom to contact if they choose to participate. The message also contained a link to the project web page and contact information to the project leader. If a selected member did not respond after two reminders, no further contact was attempted.

Second, the administrator(s) for all six groups were contacted in the same way and asked if they wanted to contribute to the study. Administrators of five of the groups took part. In one of the groups with more administrators, two participated. In total, 6 interviews were conducted with administrators.

High-activity teachers commonly described a trajectory in their interviews that seemed to connect neither to school subject, nor to the specific group, but rather appeared as a changed behaviour due to membership and activity. Third, then, aiming to affirm this trajectory, a “low-activity teacher”, someone with only a single instance of participation in the sample threads, was randomly chosen and contacted in each group. Few responded. However, it proved possible to conduct two further interviews with such teachers.

Analytic procedure

The analysis is mainly qualitative, and informed by thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). “A theme”, Braun and Clarke state, “captures something important about the data in relation to the research question, and represents some level of patterned response or meaning within the data set” (p. 82). The revision and refinement of potential themes constitute an iterative process. The analysis was conducted in three steps, containing iterative cycles of analysis, conveying different layers of meaning in the teachers’ talk.

In a first step, two of the authors analysed the 26 recorded interviews using Nvivo software. To guide this process, a protocol was outlined based on the themes in the interview guide. In total nine themes, or nodes, were constructed and used in the analysis. One of these nodes covered different aspects of participation and was selected for a deeper analysis aiming at a better understanding of how teachers’ needs and actions form their roles in these online communities. Two questions in the interview guide had explicitly addressed issues regarding participation: “Can you describe your activity in teacher Facebook groups” and “Have you changed your participation over time”. However, participation as a theme was involved also in relation to other questions in the interview guide. In total 210 minutes spread over 190 instances were analysed (teachers: 132 instances and administrators: 58 instances).

In the second step, the elicited data was analysed by all four authors noting units of meaning in the teachers’ talk separately, followed by a joint discussion after each interview, amalgamating units of meaning into the following themes: role and identity, purpose and needs, behaviour, interactional patterns, collegiality, exchange of knowledge, and engagement over time.

In relation to earlier studies, our data enabled a deeper analysis of how teachers’ needs and actions changed over time, as did the roles they developed within the community. Further, the idea of low barriers for participation seemed to be partly overrated. The data also opened up for some preliminary conclusions regarding the use and coordination of platforms.

In a third step, a saturation of themes seemed to be reached. The focus in the analytic process was changed from targeting relevant themes to determining whether any new themes could be found in the remaining interviews. No further themes were added.

Ethical considerations

In online research, special ethical considerations are needed, to protect the identity of participants. In our reports of the study, the names of the Facebook groups are not mentioned, to prevent identification of a posting member via a simple internet search. Further, in presentations and articles, translations are slightly modified to make it difficult to trace a specific post within the groups. For example, details like titles of books have been changed and links have been removed. In this article, ethical considerations regarding identification apply to the administrators in particular. The number of large Facebook groups for teachers of mathematics and Swedish is limited. If a reader identifies a group, the administrator is also easily identified. Therefore, the administrators are not connected to a school subject. The Regional Research Ethics Committee at Karlstad University has examined and approved the research project (Dnr. C2015/562). Informed consent was used in the interviews.

Results

In the interviews, we have discerned a number of actions connected to different roles along a trajectory of participation (See ). The teachers interviewed all talk about how they, depending on individual needs and knowledge, have changed their behaviour in a specific group over time. This changed behaviour follows a specific pattern, which can be related partly to the level of contribution to the community, and partly to the specific activities. Note that an individual person can have different roles in different groups. Most of the interviewed teachers describe their initial activity in a group as that of a “lurker” (Preece et al., Citation2004), that is, a person that takes on a relatively passive observer role (Arnold & Paulus, Citation2010), also referred to in a study about Facebook groups as “authorised visitors” (Lantz-Andersson et al., Citation2017). In line with Lantz-Andersson et al. (Citation2017), we here choose to use the notion “authorised visitors”, since the members “have actively requested for membership and even though they never actively contribute to the discussions, clearly, they may benefit from the interactions through this passive form of engagement” (Lantz-Andersson et al., Citation2017, p. 3). Some of the persons interviewed describe an increased activity over time characterised both by many contributions to the community and by changed behaviour. We have chosen to call the role that these members take on “key persons”, since they have many followers and what they post and how they act are influential in the context of the group.

Describing their activity over time, the members point out a key step in their behaviour – when they choose to become “public”, and visible in the group. Several of the interviewed teachers talk about shyness and describe this step by emphasising the courage needed. One teacher says: “You have to dare – it really is to dare when you come out with your name and write things in public. I think for many of us it can be a bit of a challenge to go public”. Another teacher describes this doubt about going public as a general pattern:

On the whole there are many teachers following the feed without posting themselves. That’s a general pattern. I suppose people think it’s amusing. But for different reasons you don’t think you have something to add or you feel too shy or you don’t dare to expose yourself to the public.

In the following section, the trajectory of participation, from authorised visitor to key person, is elaborated on. The participants’ initial positions are characterised by a lurking (or consuming) behaviour, where scrolling, reading, liking, following specific persons and looking for answers on specific issues are actions that characterise the authorised visitor’s role in the group. One teacher describes these actions as “taking ideas from others” or “actively seeking an answer to something”. Here it is important, the teacher continues, “to scroll a lot, look a lot, keep up, check out and so on … to follow the feed is the best, I think”. In the feed, she has also identified specific key persons: “Maybe you find a special person you want to follow. / … / In fact, there are a number of teachers that I follow on both Twitter and Instagram too, because then I get a kind of full picture. Well, I think these teachers have lots of followers in Sweden”.

The next step towards leaving the lurking position and becoming more public is not only reading what others are writing and discussing, but also starting to pose questions within the group and later also to comment on the posts of other members and to publish one’s own posts. “Lately, it has become a routine to log in and look for new discussions, read what people think about certain things”, one of the teachers says, and continues: “I’m not very active in starting threads / … / however, I find the discussion very important and have been quite active there”.

Going public means a great deal for the members’ actions within the group. Once that step has been taken, the distance to increase one’s contribution to the community seems to be quite short and from the interviews we can see that some members start their development to becoming a key person by starting to have a specific agenda with their activities within the group. For one of the teachers this development took a couple of years. “From the beginning”, he says, “it was only about gaining new knowledge, getting input and learning things”. After a while, however, he started a class blog, which became the starting point of going public and having an agenda:

I posted what we had written on our blog and then I noticed quite quickly that many people read it and thought it was fun. Then I started to post more often instead of just reading other teachers’ posts, and now I work a lot with my own webpage.

In the stage of having an agenda of their own, it is also common that members take on a clear mentoring role in relation to others who could perhaps be seen as disciples occupying a position characterised by fewer contributions to the community and members taking on roles close to the line of being public. “I try to contribute to the discussions and if anyone needs help with tests or assignments I gladly hand that over”, one teacher says when describing the mentoring role, continuing: “You know, I wish someone would have done that to help me, when I was a beginner”.

At this point, having experience of being a key person in a group, the interviewed teachers state that they have started a blog or a new Facebook group and received followers of their own. Among the interviewed members, this attention seems to be a trigger for becoming more influential, not only on Facebook, but also in other contexts. Some teachers also suggest a close link between being an ambitious and engaged teacher and using platforms on the Internet. “Those of us who are really committed teachers, we are on FB and also on Instagram”, one teacher states and goes on:

We are there. We want to share things; we do not want to sit and keep things to ourselves, but instead we think: “I have loads of material. Take it!” Without thinking that you have to receive something in exchange. It has become so natural. That’s how an extended staffroom works.

When the process of receiving followers is established, other activities are initiated, for example members start coordinating their own platforms with the activities on Facebook, such as linking to personal webpages, Twitter posts and other places of interest. To start a Facebook group of one’s own is a further step towards the final position in the trajectory – becoming an influencer. When reaching that position, the members describe a great many activities where they can function as an authority in their field. “I’ve been on the radio, I’ve been interviewed, and I’ve been asked to write books”, one of the interviewed teachers says. Another respondent states that activity in the Facebook groups has provided many new contacts who have made it possible to be part of various juries for different awards. “You can really use Facebook to show what you know and what you do”, the member concludes.

In relation to Wenger’s (Citation1998) three modes of belonging, engagement is emphasised as the source of identity in the teachers’ talk. The teachers define themselves in relation to their contribution to the group and seem to afford the power to construct an identity of competence: “We want to share things; we do not want to sit and keep things to ourselves, but instead we think: I have loads of material. Take it!” Imagination is less foregrounded in their talk, and explicated above all when the teachers compare themselves as professionals now and in the past, rather than elaborating on possible futures: “You know, I wish someone would have done that to help me, when I was a beginner”. Alignment is hardly addressed at all by the teachers. Their activities and beliefs seem to fit seamlessly with the enterprise of teacher Facebook groups and social media: “Those of us who are really committed teachers, we are on FB and also on Instagram”.

The flow or traffic between different media forms an infrastructure where Facebook seems to be a node. Especially when aiming to build a personal, professional learning network, the Facebook group appears to be at the centre of the system of infrastructure. Teachers use the Facebook group to link colleagues to their own blog, Facebook group or Twitter account. To illuminate what this flow might look like when teachers use the Facebook group to link to personal websites, an example has been selected from the sample of threads studied in the project. This example is from one of the six Facebook groups, where almost 50% of the threads contain such links. First, the teacher offers the colleagues some teaching material. The content is then valued and appreciated in the thread (See ).

Such a pattern can engage further followers. Participants in the groups not only link to their own blog, but also to other blogs they find helpful or encouraging. In our interviews with high activity teachers, the influencers explain how the Facebook groups help shape their personal learning network, building platforms with 20,000 followers and creating an arena for career progression within the school system. Without Facebook, “I wouldn’t be as successful as I am”, one teacher says and continues:

I wouldn’t have become a merited excellent teacher in Swedish if I had not had access to Facebook. All my top-level knowledge in the subject I have gained through Facebook - inspiration, tips on literature, tips on methods and so on. So it has been absolutely crucial to my professional development.

At the same time, this practice of linking can also to some extent cause tensions between members. Some of the teachers interviewed consider the linking merely as a boosting of self-esteem and emphasise how such actions have decreased their engagement in the group:

Well, maybe I don’t write so many successful stories about things I do in class as other members do. I believe those kinds of posts have something to do with new policies in school, especially the teacher leader reform. I think many of those teachers feel they have to show how competent they are, that they are worth their high salaries. Many others, like me, have chosen to step back.

It is worth noticing that instead of leaving the group, the common action among the interviewed teachers is to become a sleeping member in such cases.

Facebook as a node might also be enhanced due to the activity of the administrator. The administrators interviewed describe their role as three-fold, as gatekeepers, controlling who is invited, as editors, monitoring discussions and tone, and as educators, recommending literature or courses and forwarding news. The control of applicants has, according to the administrators, become a rather substantial part of the role, since companies have started to create teacher aliases to get access to these groups and the number of bots has increased. Therefore, gatekeeping seems to be crucial in building a professional network. Further, to build a sustainable professional network, mutual trust is seen as key, not least in affecting members’ willingness to contribute with content to the group interactions. In the monitoring role, administrators engage in a range of actions from moderating disputes, for example about posting on holidays, or introducing new perspectives in one-sided interactions and correcting misunderstandings to deleting posts, all of which are motivated by a desire to sustain the teachers’ willingness to contribute in professional discussions and thereby maintain (or increase) the activity level within the group. However, what affects Facebook as a node most in relation to the administrator’s actions is connected to the role of educator. By posting, linking and attaching content, the administrator creates a filtered news board, with events to take part in, the latest up-dates in the school debate or research adapted to the group’s interests. One of the administrators gives some examples: “For instance, have you noticed that the nominees for the August Prize have been announced? And then I link to the webpage for the category of children’s literature. I often share book tips or forward tips about events, like free courses and such”.

To summarise, the extended staffroom in teacher Facebook groups helps teachers gain new knowledge, by asking for help or getting ideas and input from others. Depending on personal needs, a teacher can take a position as an authorised visitor following the feed or specific influencers, or actively seeking an answer to a particular question, without contributing further to the community. This is the most common role, and an initial role before “exposing oneself” as a public member. A next crucial step in the trajectory described by the teachers is taken when the focus shifts from a more consuming to a more producing role. Teachers who have been through this shift act like mentors willing to help and share in an altruistic way: “We do not want to sit and keep things to ourselves, but instead we think: ‘I have loads of material. Take it!’ Without thinking that you have to receive something in exchange”. At this stage, they become key persons with a high number of contributions to the community. An overlapping, but to a certain extent more public role, is that of the influencer. Influencers have their own agenda and coordinate their activity on Facebook with further platforms, like blogs and Twitter, with thousands of followers, making Facebook a node in the network. Finally, the roles of the administrator as gatekeeper, editor, and educator seem to be prominent in making Facebook an area for professional development and a node in the broader context of social media.

Discussion

Our results show that teacher-created Facebook groups enable teachers to exchange knowledge related to professional issues on different levels, and that participating teachers can take on different roles depending on individual needs (c.f. Liu et al., Citation2016). The analysis given here suggests that high activity teachers change their behaviour and actions in a specific group over time. A crucial point for these teachers seems to be whether they want to be public or not, that is, if they wish to change their participation as an authorised visitor towards more visible participation patterns: “It really is to dare when you come out with your name and write things in public”. In this aspect, our results differ from earlier studies (Booth, Citation2012; Visser et al., Citation2014) that have pointed out low barriers for participation. Over time, some members change their behaviour in the groups quite dramatically, from being invisible and authorised visitors to, through developing an expert role, becoming influential key persons in the group with a strong professional identity.

Our study confirms Prestridge’s (Citation2019) results that participants take on different roles in teacher Facebook groups. The roles identified in our study (authorised visitor, public member, mentor, and influencer) are similar to the four roles recognised by Prestridge: info-consumer, info-networker, self-seeking contributor, and vocationalist. In a way, this result challenges the current image of the digital prosumer. Instead, teachers seem to take on different roles as consumers and producers over time and/or in different groups depending on their personal needs.

At an important point, our study expands the picture of teachers taking on different roles, namely by the shaping of a trajectory from a novice to an expert behaviour (c.f. Lave & Wenger, Citation1991). This trajectory appears to be informed by participation in the on-line community, that is, the extended staffroom rather than their formal position or time of employment. In fact, becoming influential key persons in teacher Facebook groups might support their careers. By using Facebook as a showroom, they are offered possibilities to share their knowledge and ideas in a broader context via interviews, books, or presentations at teacher conferences. At the same time, however, the influencer role may elicit both helpfulness and selfishness from colleagues.

In relation to the role of an influencer, the role of a consumer or authorised visitor has only been partly described in this study, due to the selection of participants. This role merits further investigation as it is the most common role in large teacher Facebook groups. For example, the results raise questions whether you need to leave this position to be a full participant, and if all participants change their roles over time.

To get a fuller picture of the extended staffroom, our results show that teacher Facebook groups constitute just one of the pieces in the online network (Krutka et al., Citation2016). The results indicate that Facebook as a platform plays an important role as a node in this professional network. Former studies (Lantz-Andersson et al., Citation2018) have pointed out affordances in different platforms as an area for further research. The teachers we study use Facebook as a means to interact. Therefore, the generous span of characters allowed for a single post might be of importance. The possibility to use Messenger for further interaction with specific colleagues is also mentioned by our interviewees. For purposes of professional growth, a sharing practice predominates the interactions. To share examples of instruction, worksheets or suggestions for readings, the possibility to attach documents is crucial. Another practice identified in our study is the linking to, above all, your own blog. We suggest that these four affordances – the span of characters, the messaging function, the possibility to attach documents and the linking – contribute to putting Facebook at the centre of the network. However, what seems to be even more important to create a professional network are the actions undertaken by the administrators of the teacher Facebook groups. Their roles as gatekeepers, editors and educators merit further investigations.

Conclusion

School development in Sweden is highly informed by a wish to enhance professional learning through collective processes. Over the last decade, in-service training has been designed to support the development of professional learning communities. This movement is recognisable worldwide. How such top-down PLC-programmes and bottom-up initiatives like e-PLC efforts support or complement each other is a question for further research.

A substantial number of studies (c.f. Muls et al., Citation2019; Ranieri et al., Citation2012; Tour, Citation2017; Vangrieken et al., Citation2017) state that teacher Facebook groups serve professional development and growth. As one of the teachers interviewed expresses it: “My entire professional development takes place there”. A second teacher argues that you will find the most competent colleagues in teacher Facebook groups, and a third celebrates the altruistic sharing practice. If the extended staffroom meets all these needs, what is the role of the local staffroom?

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for valuable feedback from professor Kenneth Ruthven, University of Cambridge, UK.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ann-Christin Randahl

Ann-Christin Randahl has a position as associate professor in Swedish with specialization in didactics at the Department of Swedish, Multilingualism, and Language Technology at Gothenburg University. Her main research interests are writing, professional development, and social media. She is part of ROSE and the LCT Nordic network.

Yvonne Liljekvist

Yvonne Liljekvist is an Associate Professor in Mathematics Education at Karlstad University. Her research focus on conditions for mathematics teaching and learning and its relation to teachers’ professional development and school improvement.

Christina Olin-Scheller

Christina Olin-Scheller is a Professor of Applied Pedagogy at Karlstad University. Her research interests are reading instruction and young people’s reading and writing in and outside school, with a specific focus on today’s media landscape. She is the director of the Center for Language and Literature in Education, (CSL) as well the research group Research on Subject-Specific Education, (ROSE). She coordinates the international network Knowledge and Quality across School Subjects and Teacher Education, KOSS, and participates in the Nordic excellence center Quality in Nordic Teaching, QUINT.

Jorryt van Bommel

Jorryt van Bommel is an Associate Professor in mathematics education at Karlstad University in Sweden and at Høgskolan Innlandet in Norway. In her research she focuses on early mathematics, teaching quality as well as on teachers’ professional development.

References

- Arnold, N., & Paulus, T. (2010). Using a social networking site for experiential learning: Appropriating, lurking, modeling and community building. The Internet and Higher Education, 13(4), 188–196.

- Beach, P. (2017). Self-directed online learning: A theoretical model for understanding elementary teachers’ online learning experiences. Teaching and Teacher Education, 61, 60–72.

- Bissessar, C. S. (2014). Facebook as an informal teacher professional development tool. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 39(2), 120–135.

- Booth, S. E. (2012). Cultivating knowledge sharing and trust in online communities for educators. Journal of Educational Computing, 47(1), 1–31.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

- Britt, V. G., & Paulus, T. (2016). “Beyond the four walls of my building”: A case study of #edchat as a community of practice. American Journal of Distance Education, 30(1), 48–59.

- Brown, R., & Munger, K. (2010). Learning together in cyberspace: Collaborative dialogue in a virtual network of educators. Journal of Technology and Teacher Education, 18(4), 541–571. https://www.learntechlib.org/primary/p/29529/

- Carpenter, J. P., & Krutka, D. G. (2015). Engagement through microblogging: Educator professional development via twitter. Professional Development in Education, 41(4), 707–728.

- Greenhow, C., & Askari, E. (2017). Learning and teaching with social network sites: A decade of research in K-12 related education. Education and Information Technologies, 22(2), 623–645.

- Halliday, M. A. K., & Matthiessen, C. (2013). Halliday’s introduction to functional grammar. 4th. London:Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203431269

- Jenkins, H. (2006). Fans, bloggers and gamers: Exploring participatory culture. New York: New York University Press.

- Kelly, N., & Antonio, A. (2016). Teacher peer support in social network sites. Teaching and Teacher Education, 56, 138–149.

- Krutka, D. G., Carpenter, J. P., & Trust, T. (2016). Elements of engagement: A model of teacher interactions via professional learning networks. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 32(4), 150–158.

- Lantz-Andersson, A., Lundin, M., & Selwyn, N. (2018). Twenty years of online teacher communities: A systematic review of formally-organized and informally-developed professional learning groups. Teaching and Teacher Education, 75, 302–315.

- Lantz-Andersson, A., Peterson, L., Hillman, T., Lundin, M., & Bergviken-Rensfeldt, A. (2017). Sharing repertoires in a teacher professional facebook group. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 15, 44–55.

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

- Liljekvist, Y., Randahl, A.-C., van Bommel, J., & Olin-Scheller, C. (2020). Facebook for professional development: Pedagogical content knowledge in the centre of teachers’ online communities. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research. doi:10.1080/00313831.2020.1754900

- Liljekvist, Y., van Bommel, J., & Olin-Scheller, C. (2017). Professional learning communities in a web 2.0 world: Rethinking the conditions for professional development. In I. H. Amzat, N. P. Valdes, & B. Yusuf (Eds.), Teacher empowerment toward professional development and practices: Perspectives across borders (pp. 269–280). Singapore: Springer.

- Liu, K., Miller, R., & Jahng, K. E. (2016). Participatory media for teacher professional development: Toward a self-sustainable and democratic community of practice. Educational Review, 68(4), 420–443.

- Lundin, M., Lantz-Andersson, A., & Hillman, T. (2017). Teachers’ reshaping of professional identity in a thematic FB-Group. QWERTY Open and Interdisciplinary Journal of Technology, Culture and Education, 12(2), 12–29.

- Macià, M., & García, I. (2016). Informal online communities and networks as a source of teacher professional development: A review. Teaching and Teacher Education, 55, 291–307.

- Macià, M., & I, G. (2018). Professional development of teachers acting as bridges in online social networks. Research in Learning Technology, 26. doi: 10.25304/rlt.v26.2057

- Muls, J., Triquet, K., Vlieghe, J., De Backer, F., Zhu, C., & Lombaerts, K. (2019). Facebook group dynamics: An ethnographic study of the teaching and learning potential for secondary school teachers. Learning, Media and Technology, 44(2), 162–179.

- Preece, J., Nonnecke, B., & Andrews, D. (2004). The top five reasons for lurking: Improving community experiences for everyone. Computers in Human Behavior, 20(2), 201–223.

- Prestridge, S. (2019). Categorising teachers’ use of social media for their professional learning: A self-generating professional learning paradigm. Computers and Education, 129, 143–158.

- Randahl, A.-C. (2018). Språkhandlingar i professionella lärandegemenskaper på Facebook. A. M. Hipkiss, P. Holmberg, L. Olvegård, K. Thyberg, & M. P. Ängsal Eds., Grammatik, kritik, didaktik: Nordiska studier i systemisk-funktionell lingvistik och socialsemiotik 117–127. Göteborg Trettonde nordiska konferensen för systemisk Trettonde nordiska konferensen för systemiskfunktionell lingvistik och socialsemiotik (NSFL 13) Göteborgs universitet. 12-13 October 2017

- Ranieri, M., Manca, S., & Fini, A. (2012). Why (and how) do teachers engage in social networks? An exploratory study of professional use of facebook and its implications for lifelong learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 43(5), 754–769.

- Rehm, M., & Notten, A. (2016). Twitter as an informal learning space for teachers!? The role of social capital in twitter conversations among teachers. Teaching and Teacher Education, 60, 215–223.

- Robson, J. (2016). Engagement in structured social space: An investigation of teachers’ online peer-to-peer interaction. Learning, Media and Technology, 41(1), 119–139.

- Rodesiler, L. (2017). For teachers, by teachers: An exploration of teacher generated online professional development. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 33(4), 138–147.

- Rosenberg, J. M., Reid, J., Dyer, E., Koehler, M. J., Fischer, C., & McKenna, T. J. (2020). Idle chatter or compelling conversation? The potential of the social media-based #NGSSchat for supporting science education reform efforts. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 57(9), 1322–1355.

- Sahlström, F. (2009). Conversation analysis as a way of studying learning: An introduction to a special issue of SJER. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 53(2), 103–111.

- Shulman, L. S. (1987). Knowledge and teaching: Foundations of the new reform. Harvard Educational Review, 57(1), 1–21.

- Stoll, L., Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Wallace, M., & Thomas, S. (2006). Professional learning communities: A review of the literature. Journal of Educational Change, 7(4), 221–258.

- The Swedish National Agency for Education (2021). Official Statistics of Sweden Table 5A.

- Tour, E. (2017). Teachers’ self-initiated professional learning through personal learning networks, technology. Pedagogy and Education, 26(2), 179–192.

- Tsiotakis, P., & Jimoyiannis, A. (2016). Critical factors towards analysing teachers‘ presence in on-line learning communities. The Internet and Higher Education, 28, 45–58.

- van Bommel, J., & Liljekvist, Y. (2016, October). Teachers’ informal professional development on social media and social network sites: When and what do they discuss? [ Paper presentation]. ERME-topic conference: Mathematics teaching, resources and teacher professional development, Humboldt-Universität, Berlin, Germany.

- van Bommel, J., Randahl, A., Liljekvist, Y., & Ruthven, K. (2020). Tracing teachers’ transformation of knowledge in social media. Teaching and Teacher Education, 87, 102958. Article 102958

- Vangrieken, K., Meredith, C., Packer, T., & Kyndt, E. (2017). Teacher communities as a context for professional development: A systematic review. Teaching and Teacher Education, 61, 47–59.

- Visser, R. D., Evering, L. C., & Barrett, D. E. (2014). #TwitterforTeachers: The implications of twitter as a self-directed professional development tool for K–12 teachers. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 46(4), 396–413.

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wenger, E. (2006). Communities of Practice – A Brief Introduction. Accessible on: http://www.ewenger.com/theory/communities_of_practice_intro.htm.

- Wenger, E., McDermott, R., & Snyder, W. M. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice. Boston: Harvard Business Press.

- Wesely, P. M. (2013). Investigating the community of practice of world language educators on twitter. Journal of Teacher Education, 64(4), 305–318.

- Zuidema, L. A. (2012). Making space for informal inquiry. Journal of Teacher Education, 63(2), 132–146.